François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXXIX: Venice 1833

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 1: What Madame la Duchesse de Berry had been doing – Charles X’s Council in France – My ideas regarding Henri V – My letter to Madame la Dauphine

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 2: A letter from Madame la Duchesse de Berry

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 3: JOURNAL FROM PARIS TO VENICE: Jura – the Alps – Milan – Verona – A Roll-call of the Dead – The Brenta

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 4: DIGRESSIONS: Venice

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 5: Venetian Architecture – Antonio – The Abbé Bettio and Monsieur Gamba – Rooms in the Doge’s palace – Prisons

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 6: The Prison of Silvio Pellico

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 7: The Frari – The Accademia di Belle Arti – Titian’s Assumption – The Metopes of the Parthenon – Original drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael – The Church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 8: The Arsenal – Henri IV – A frigate leaving for America

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 9: Saint Christopher’s Cemetery

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 10: San Michele di Murano – Murano – The woman and child - Gondoliers

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 11: The Bretons and Venetians – Breakfast on the Riva degli Schiavoni – Mesdames at Trieste

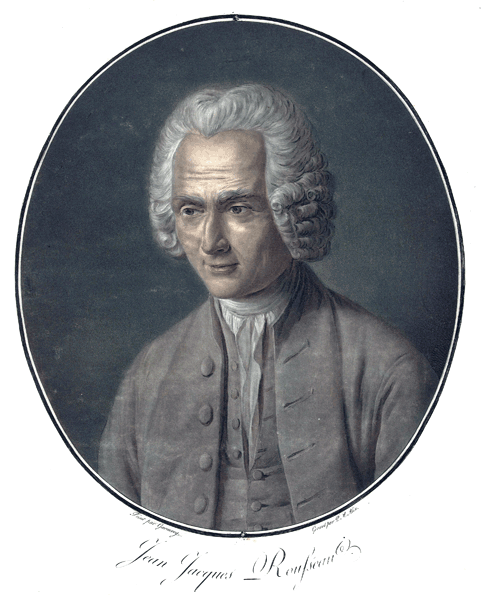

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 12: Rousseau and Byron

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 13: Great Geniuses inspired by Venice – Courtesans ancient and modern – Rousseau and Byron born to be unhappy

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 14: Zanze

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 15: Madame Mocenigo – Count Cicognara – A bust of Madame Récamier

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 16: A Soirée at Madame Albrizzi’s – Lord Byron according to Madame Albrizzi

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 17: A Soirée at Madame Benzoni’s – Lord Byron according to Madame Benzoni

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 18: A gondola ride – Poetry – Catechism at St Peter’s – An aqueduct – A conversation with a fisher-girl – The Giudecca – Jewish women

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 19: Nine centuries of Venice seen from the Piazzetta – The decline and fall of Venice

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 20: The Lido – Venetian Festivities – The Lagoon on leaving Venice for the first time – News of Madame la Duchesse de Berry – The Jewish Cemetery

- Book XXXIX: Chapter 21: Reverie on the Lido

Book XXXIX: Chapter 1: What Madame la Duchesse de Berry had been doing – Charles X’s Council in France – My ideas regarding Henri V – My letter to Madame la Dauphine

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, 6th of June 1833.

BkXXXIX:Chap1:Sec1

On descending from the carriage, and before going to bed, I wrote a letter to Madame la Duchesse de Berry to give an account of my mission. My return had caused a commotion amongst the police; the telegraph announced the news to the Prefect of Bordeaux and the commander of the fortress of Blaye: they were ordered to redouble their surveillance; it seemed they had even forced Madame to embark before the day fixed for her departure. My letter missed Her Royal Highness by a few hours and was sent on to her in Italy. If Madame had not made her declaration; if even after that declaration she had denied the consequences; moreover, if, on arrival in Sicily, she had continued to protest about the role she had been constrained to play to escape her gaolers, France and Europe would have believed what she said, Philippe’s government being so suspect. All the Judases would have been punished for the spectacle they had given the world, by the murkiness of Blaye. But Madame did not wish to preserve her political character by denying her marriage; what is gained by a lie regarding one’s reputation for ability, is lost in lack of esteem; the sincerity you have been able to claim scarcely aids you. Let someone valued by the public debase themselves, and they are no longer protected by their fame, but are forced to shelter behind their fame. Madame, by confessing, escaped the shadow of prison: the female eagle, like the male, desires freedom and sunlight.

In Prague, Monsieur le Duc de Blacas, announced the formation of a Council which I was to lead, with the former Chancellor, and Monsieur le Marquis de Latour-Maubourg: I (according to Monsieur le Duc) was to be the only one of Charles X’s councillors to act in absentia in various matters. They showed me a plan: the workings were very complicated; Monsieur de Blacas’ draft retained several arrangements made by the Duchesse de Berry, while, on her side, she intended to organise the State, by coming foolishly, but courageously, to place herself at the head of her kingdom in partibus. That adventurous woman’s ideas did not lack sense: she had divided France into four large military enclaves, designated their leaders, named the officers, formed the soldiers into regiments, and without worrying whether everyone was for the flag, she hastened to bear it herself; she had no doubts of finding in the field Saint Martin’s cope, or the Oriflamme, Galaor or Bayard. Blows from war-axes, musket-balls, retreats through the forest, danger at the hearths of loyal friends, caves, castles, cottages, and scaling-ladders: all that was fine and pleasing to Madame. There was something odd, original and attractive in the character which gave her life; the future found her willing, despite correct advisors and wise cowards.

‘The Chevalier Bayard’

Character Sketches of Romance, Fiction and the Drama - Ebenezer Cobham Brewer (p200, 1892)

Internet Archive Book Images

If they had summoned me, I would have brought the Bourbons the popularity I enjoyed under my twin titles of writer and Statesman, since I had received support from all shades of opinion. This was not expressed in generalities; each told me what he expected from events; several confessed their genius and freely pointed out the position to which they were eminently suited. Everyone (friends and enemies) sent me to see the Duc de Bordeaux. Because of my various shades of opinion and my chequered fortune, because the ravages of death had removed in succession the men of my generation, I seemed to be the Royal Family’s sole remaining choice.

I might have been tempted by the role they assigned me; there was something flattering to my vanity, I, the servant ignored and rejected by the Bourbons, to be a prop to their race, to clasp the hands of Philippe-Auguste, Saint-Louis, Charles V, Louis XII, Francis I, Henri IV, Louis XIV in their tombs; to defend with my feeble renown the blood, the crown, the shades of so many great men, I, alone against faithless France and a debased Europe.

But to achieve it what would I have to do? What the humblest spirit had done: flatter the Court in Prague, overcome its antipathy, and conceal my thoughts from it until I was in a position to develop them.

And indeed, those ideas went far: if I had been the young Prince’s tutor, I would have tried hard to win his confidence. If he were destined to recover his crown, I would have counselled him to wear it only in order to sacrifice it at a future time. I wished to see the Capets depart in a manner worthy of their greatness. What a fine and noteworthy day that would be when, having exalted religion, perfected the constitution of the State, extended the rights of citizens, broken the last shackles of the Press, emancipated the boroughs, destroyed monopolies, matched salaries fairly to the work done, strengthened the rights of property while curbing its abuses, re-invigorated industry, lowered taxes, re-established our honour among the nations, and assured, by extending our borders, our freedom from foreign interference; what a fine day that would be when, all of the above being accomplished, my pupil could say to the nation in solemn conclave:

‘People of France your education has ended with mine. My first ancestor, Robert the Strong died for you, while my own father demanded mercy for the man who took his life. My forefathers created France and raised it from barbarism: now the march of the centuries, the progress of civilisation no longer requires that you have a tutor. I relinquish the throne; I confirm all my ancestors’ benefactions and deliver you from your oaths to the monarchy.’ Tell me whether that end would not surpass whatever was most marvellous about that race? Tell me if as great a temple could ever be erected in its memory? Compare that end, to the one the decrepit sons of Henri IV achieved, obstinately clinging to a throne submerged by democracy, trying to retain power with the aid of police measures, violence, corrupt votes, dragging on a degraded existence for a few instants? ‘Let them make my brother King,’ said the young Louis XIII, after the death of Henri IV, ‘as for me, I do not wish to be King.’ Henri V has no brother other than his people: let them make him King.

To achieve this outcome, chimerical as it may seem to be, he must feel the greatness of his race, not because he is descended from an ancient line, but because he is the heir of men through whom France became powerful, enlightened and civilised.

Now, as I have explained but a short while ago, the means of being summoned to put my hand to that plan was to fawn on the weak people in Prague, to fly ‘shrikes’ with the heir to the throne in imitation of Luynes, to flatter Concini as Richelieu did. I had started well in Carlsbad; a little communiqué full of deference and gossip would have advanced my affairs. To inter myself while still alive in Prague, it is true, would not be easy, for I would not only have to overcome the repugnance of the Royal Family, but also hatred for a stranger. My ideas are odious to government; they know I detest the Treaty of Vienna, that I would embrace war at any price to give France back its required frontiers, and re-establish the balance of power in Europe.

Yet by signs of repentance, tears, expiating my sins against national honour, beating my breast, admiring, as a penance, the genius of the fools who govern the world, perhaps I would be able to crawl to the place occupied by Baron Damas; then, suddenly straightening myself, I would throw away my crutches.

But alas! My ambition, where is it? My ability to deceive where is it? My prop to support the constraint and boredom, where is it? My means of attaching importance to everything that happens, where is that? I picked up my pen two or three times; I began two or three deceitful drafts in obedience to Madame la Dauphine who had commanded me to write to her. Swiftly, rebelling against myself, I wrote in one go, in my own style, the letter which was to end things for me. I knew it well; I weighed the consequences carefully: they mattered little to me. Today, even though the thing is done, I am delighted to have sent it all to the devil and thrown my tutorship through a high enough window. People will say: ‘Could you not have expressed the same truths but enunciated them with less crudity?’ Yes, yes, by prevaricating, writhing, flattering, squirming about, and trembling:

...His penitent eye weeps only holy water.

I know not how to do it.

Here is the letter (abridged however by almost half) which made the hairs of our drawing-room diplomats bristle. The Duc de Choiseul shared a little of my mood; and he ended his life at Chanteloup.

A LETTER TO MADAME LADAUPHINE

‘Paris, Rue d ‘Enfer, 30th of June 1833.

Madame,

The most precious moments in my long career have been those that Madame la Dauphine has allowed me to spend with her. On a humble mission to Carlsbad a Princess, the object of universal veneration, has deigned to speak to me in confidence. In the depths of her soul Heaven has placed a treasure, of magnanimity and religion, which excessive misfortune has failed to exhaust. I had before me the daughter of Louis XVI in a new exile; that orphan of the Temple, whom the martyred king had pressed to his heart before going to win the palm! God’s name alone is to be spoken when one loses oneself in contemplation of the impenetrable designs of his providence.

Praise addressed to prosperity is suspect: regarding the Dauphine, admiration may be unrestrained. I have said Madame that your misfortunes have mounted so high they have become one of the glories of the Revolution. I have therefore met once in my life with a destiny so elevated, so individual, as to be able to speak, without fear of harming it or of not being understood, about the future state of society. One can discuss with you the fate of empires, you who would see all the kingdoms of the earth pass before your feet without regret, kingdoms several of which have already fallen at the feet of your race.

The catastrophes that made you their most illustrious witness and most sublime victim, as great as they may seem, are nevertheless only particular events within a general transformation operating on the human species; the reign of Napoleon, who shook the world, is no more than a link in the revolutionary chain. One must begin with that reality in order to understand what is possible for a third Restoration, and by what means that Restoration might be framed within the envisaged social change. If it is not incorporated as a homogenous element, it would inevitably be rejected by an order of things inimical to its nature.

Thus, Madame, if I were to tell you that there was a possibility of the Legitimacy returning, with the aristocratic nobility and clergy and all their privileges, with the Court and its distinctions, royalty with its prestige, I would be deceiving you. The Legitimacy in France is no more than a sentiment; it is a principle as long as it guarantees property and interest, rights and freedoms; but if it were to demonstrate that it refused to defend, or was powerless to protect, that property and interest, those rights and freedoms, it would cease even to be a principle. If anyone were to claim that the Legitimacy could return by force, that people cannot do without it, that it would only have to appear for France to offer thanks to it on her knees, they would be in error. The Restoration will never re-appear nor last more than a moment, if the Legitimacy seeks power where it no longer resides.

Yes, Madame, and I say this sadly, Henri V may remain a foreign, exiled Prince; a young and recent ruin of an ancient building that has already fallen, but still a ruin. We former servants of the Legitimacy, we will soon have expended the little fund of years remaining to us, we will shortly rest in the grave, slumbering among our outdated ideas, like knights of old in their ancient armour gnawed by time and rust, armour that no longer fits nor is adapted to modern use.

Everything that in 1789 militated in favour of the old regime, religion, laws, customs, habits, ownership, class, privilege, institutions, no longer exists. A general ferment is in evidence; Europe is hardly more safe from it than ourselves; no mode of society has wholly vanished, none is wholly secure; everything is either worn-out or a novelty, either decrepit or rootless; everything shows the weakness of old age or infancy. Kingdoms born of territorial limitation mapped out by former treaties are things of yesterday; attachment to country has lost its force, because the concept of country is vague and transient for populations sold at auction, hawked like second-hand furniture, now annexed to alien populations, now handed over to unknown masters. Trampled, furrowed, ploughed, the soil was thus ready to receive the democratic seed that the July Days have nurtured.

Kings believe that by keeping watch from their thrones, they will halt the progress of ideas; they imagine that by issuing a description of principles they can have them seized at their frontiers; they are persuaded that by increasing the number of customs men, gendarmes, police spies, and military commissions, they will prevent them circulating. But ideas do not travel on foot, they are in the air, they fly about, people breathe them in. Absolute governments that establish telegraph posts, railways, steamboats, and yet at the same time wish to keep thought at the level of fourteenth century political dogma are neither here nor there; at once progressive and reactionary, they mire themselves in the confusion that results from theory and practice in contradiction one with the other. One cannot divorce industrialisation from the principle of liberty; one is forced to suppress both or accept both. Everywhere the French language extends, ideas arrive with passports issued by the century.

You will see, Madame, how essential it is to make the right start. The child of hope under your protection, the innocent protected by your virtues and misfortune as beneath a royal dais, I know no more imposing spectacle; if the Legitimacy has any chance of success, there it stands in its entirety. The France of the future might bow, without lowering itself, before the glory of its past, halting dumbfounded before this mighty apparition of its history represented by the daughter of Louis XVI, leading the latest Henri by the hand. As Royal protector of the young Prince, you would bring to bear on the nation the influence of vast memories which merge with your august person. Who will not feel an unaccustomed confidence if the orphan of the Temple oversees the education of the orphan of Saint Louis’ race?

It would be desirable, Madame, if that education, directed by men whose names are popular in France, were to be to some degree public. Louis XIV, who otherwise justified his pride in his motto, did his nation great harm by isolating the sons of France within the confines of an oriental education.

The young Prince seemed to me to be endowed with a lively intelligence. He should finish his studies by visiting ancient lands and even the New World, to understand politics and so fear neither institutions nor doctrines. If he has the opportunity to serve as a soldier in some distant foreign war, one should not fear to expose him to it. He has a resolute air; he seems to have his father’s and mother’s heart; but if he ever knows anything other than a feeling of glory when faced with danger, let him abdicate: without courage, in France, no crown.

In seeing me project Henri V’s education into the distant future, Madame, you will naturally assume that I do not consider him destined to remount the throne for a long time. I will try to explain impartially my contrasting reasons for hope and doubt.

‘Monsieur le Compte de Chambord’

L'Illustration: Journal Universel (p152, 1843)

Internet Archive Book Images

The Restoration could take place today, or tomorrow. Something abrupt and inconstant is so much a part of the French character that change is always likely; the odds are always a hundred to one in France of something failing to last long: it is when the government seems most secure that it falls. We have seen a nation adore and detest Bonaparte, abandon him, re-adopt him, desert him once more, forget him in exile, erect altars to him after his death, then lose its enthusiasm for him. This flighty nation, which loves freedom only on whim, but is always terrified by equality; this multiform nation, was fanatical under Henri IV, factious under Louis XIII, serious under Louis XIV, revolutionary under Louis XVI, sombre under the Republic, bellicose under Bonaparte, and constitutional under the Restoration: it prostitutes its freedom today to a so-called republican monarchy, altering its nature perpetually according to the minds of its leaders. Its changeability has increased since it freed itself from family customs and the yoke of religion. So, some mischance may lead to the fall of the government of the 9th of August; but mischance may be expected: an abortion has been born to us; but France is a robust mother; she can, with her breast-milk, correct the vices of a depraved paternity.

‘M. le Compte de Chambord à Wiesbaden’

L'Illustration: Journal Universel (p151, 1843)

Internet Archive Book Images

Though the present monarchy does not seem viable, I still fear lest it survive beyond the term one might assign to it. For forty years, each government in France has only perished through its own mistakes. Louis XVI could have saved his life and his crown twenty times; the Republic only succumbed to the excesses of its own fury; Bonaparte could have established his dynasty, and yet hurled himself from the heights to the depths of his glory; without the July ordinances, the Legitimacy would still be in place. The leader of the present government will not commit any of the faults that kill; his reign will never commit suicide; all his skill is employed in self-preservation: he is too intelligent to die by folly, and does not have in him whatever makes one guilty of the errors of genius, or the frailties of honour and virtue. He has realised he might perish in war, he will not make war; let France be lowered in the eyes of foreign powers: it matters little to him: the publicists will show that disgrace is good for industry and ignominy for credit.

The quasi-Legitimacy wants everything the Legitimacy wants, except for the royal personage: it wants order; it can obtain it by arbitrary power more effectively than the Legitimacy. To act despotically, while employing words of freedom and so-called royalist institutions, is all it desires: every deed accomplished enhances its right to exist: every hour its legitimacy increases. The age employs twin powers: with one hand it overthrows, with the other it builds. Moreover time works on minds by the mere fact that it passes; people are completely alienated from those in power, they attack them, they want nothing to do with them; then lassitude intervenes; success reconciles them to their cause; soon only a few elevated souls remain independent, whose perseverance makes those who have surrendered ill at ease.

Madame, this long dissertation obliges me to explain myself to Your Royal Highness.

If I had not raised a free voice in the days of good fortune, I would not have the courage to speak the truth in times of misfortune. I did not go to Prague on my own account; I would not have dared annoy you with my presence: the risks of devotion are in France, not in the neighbourhood of your august person: it is there I have sought them. Since the July Days I have not ceased fighting on behalf of the Legitimist cause. I was the first to dare to proclaim Henri V’s royalty. A French jury, by acquitting me, allowed my proclamation to stand. I only wish for peace, the need of my old age; yet I have not hesitated in sacrificing it whenever decrees extended and renewed the royal family’s proscription. Offers were made to me to attach myself to Louis-Philippe’s government; I did not merit that kindness; I showed how incompatible it was with my nature, by claiming what might be due to me of my aged King’s adversities. Alas! I did not cause those adversities, and I tried to prevent them. I do not recall these circumstances to give myself a false importance or create a merit I do not possess: I only did my duty; I am merely justifying myself, in order to excuse my freedom of expression. Madame will pardon the frankness of a man who would delight in going to the scaffold in order to grant her a throne.

When I appeared before Your Majesty at Carlsbad, I may say that I had never had the pleasure of being known there. You had barely had the honour of addressing a word to me during my whole life. You may have felt in private conversation with me that I was not the man others had described to you; that my independence of spirit has not altered my innate sense of moderation, and above all has not broken the bonds of my admiration and respect for the illustrious daughter of kings.

Yet I beg Your Majesty to reflect on the fact that the series of truths developed in this letter, or rather this memo, are what constitutes my power, if I have any: it is through them that I move men of diverse parties and bring them back to the royal cause. If I had repudiated the opinions of this century, I would have had no hold on my times. I seek to rally round the ancient throne those modern ideas which, inimical though they may be, become friends by passing the gate of my loyalty. If the flood of Liberal opinion is not diverted to the benefit of legitimate monarchy, European monarchy will perish. There will be a battle to the death between the two principles of monarchy and republicanism, if they remain separate and distinct: the consecration of a unique edifice constructed from the diverse material of the two edifices will belong to you Madame, who have been admitted to the most elevated as well as the most mysterious of initiations, unmerited misfortune, to you who have been marked at the altar with the blood of innocent victims, to you who by winning a saintly austerity will open the gates of the new temple with pure hands.

Your intelligence, Madame, and your superior powers of reason will clarify and rectify whatever is doubtful or erroneous in my sentiments concerning the present situation in France.

My emotion, in terminating this letter, is greater than I can say.

The Palace of the Kings of Bohemia is now the Louvre of Charles X and his royal and pious son! The Hradschin is young Henri’s Château of Pau! And you Madame, what Versailles do you inhabit? To what can one compare your religiosity, your greatness, and suffering, if not to that of the women of the House of David who wept at the foot of the cross? May Your Majesty see the royal line of Saint Louis rise radiantly from the tomb! May I proclaim it, while recalling the age which bears the name of your glorious ancestor; for, Madame, nothing is yours, nothing is contemporary with you but the great and the sacred:

“...O happy day for me!

With what ardour I will recognize my King!”

I am, Madame, with the profoundest respect for Your Majesty,

Your very humble and obedient servant,

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

Having written this letter, I lapsed back into my usual life: I sought out my old priests again, the solitary corner of my garden which appeared more beautiful to me than that of Count Choteck, my Boulevard d’Enfer, my Cemetery of the West, my Memoirs recalling past days, and above all the little select society of the Abbaye-aux-Bois. The kindness of a deep friendship creates a plenitude of thoughts; a few moments of commerce between souls satisfies the needs of my nature; I then atone for that expenditure of intellect by twenty-four hours of idleness and sleep.

Book XXXIX: Chapter 2: A letter from Madame la Duchesse de Berry

Paris, Rue d’Enfer, 25th of August 1833.

BkXXXIX:Chap2:Sec1

While I was regaining my breath, I witnessed the entry to my house one morning of the traveller who had taken a letter of mine to Madame la Duchesse de Berry in Palermo; he brought me this reply from the Princess:

‘Naples, 10th of August 1833.

I have written a word to you, Monsieur le Vicomte, to acknowledge receipt of your letter, desiring a sure opportunity of speaking to you of what you have seen and done in Prague. It seems to me that they allowed you to see very little, yet enough to judge that despite the means employed the result, as regards our dear child, gives no grounds for fear. I am very relieved to have had your assurance about the matter; but they tell me from Paris that Monsieur Barrande has been dismissed. What is to be made of that? How I long to take up my rightful place!

As for the requests I asked you to make (which were not exactly welcome) they have shown that they were no better informed about it than I: since I have no need of what I requested, having relinquished none of my rights.

I am going to ask your advice in replying to the solicitations made to me on all sides. In your wisdom, you may make what use you deem suitable of what follows. Royalist France, people devoted to Henri V, await a proclamation from his mother, free at last.

I left a few lines behind at Blaye which should be known by now; they expect more from me; they want to know the sad history of my detention for seven months in that impenetrable fortress. It shall be known in all its terrible detail; let them see the cause of the many tears and sorrows that have broken my heart. They will understand the moral torments I had to suffer. Justice ought to be rendered to the guilty; but also those atrocious measures should be revealed, taken against a woman, defenceless since they always refused her a lawyer, by a government headed by her relative, in order to drag from me a secret which, in any event, should not have concerned politicians, and whose discovery could not alter my position if I was an object of fear to the French government, which had the power to imprison me, but not the right, without a trial which I have more than once demanded.

But my relative, my aunt’s husband, head of a family to which, despite the opinions so generally and justly levelled against it, I had wished to marry my daughter, Louis-Phillipe himself, believing me pregnant and unmarried (which would have resulted in any other family opening the prison gates for me) inflicted every moral torment on me to force me to take steps by which he thought to establish his niece’s dishonour. Moreover, if I have to explain in a positive way my declarations and what motivated them, without entering into details of my private life, of which I need account to no one, I say truthfully that they were dragged from me by vexation, moral torment and the hope of recovering my freedom.

The bearer will give you details and tell you of the inevitable uncertainty at the time regarding the date of my embarkation and its destination, which thwarted the desire I had to profit from your obliging offer in asking you to meet me before your arrival in Prague, having great need of your advice. Now would be too late, since I hope to be with my children as soon as possible. But since nothing is certain in this world, and since I am accustomed to setbacks, if, against my will, my arrival in Prague is delayed, I certainly count on seeing you wherever I am forced to stop, from where I will write to you; if on the contrary, I am with my son as soon as I wish, you know better than I whether you ought to come. I can only assure you of the pleasure I would have in seeing you at any time and in any place.

MARIE-CAROLINE.’

‘Naples, 18th of August 1833

Our friend having been unable to leave as yet, I am receiving reports about what is happening in Prague which do nothing to diminish my desire to go there, but also make my need of your advice more urgent. If then you can travel to Venice without delay you will find me there, or letters waiting at the post-office, which will tell you where you can find me. I will be making part of the journey with people for whom I have great friendship and know well, Monsieur and Madame Bauffremont. We often speak of you; their devotion to me, and our Henri, makes them wish to see your arrival. Monsieur de Mesnard shares that desire as well.’

Madame de Berry mentions in her letter a little manifesto published on leaving Blaye which was worth little since it said neither yes nor no. The letter however is interesting as a historical document in revealing the Princess’ sentiments regarding the relatives who were her gaolers, and indicating the suffering she had endured. Marie-Caroline’s reflections are just; she expresses them with animation and pride. One loves to see that devoted and courageous mother, imprisoned or free, still constantly preoccupied with her son’s interests. There, in that heart at least, was youth and life. It would cost me something to start a long journey once more, but I was too moved by that poor Princess’ confidences to refuse her wishes and forsake her on the highroad. Monsieur Jauge hastened to relieve my distress as on the first occasion.

I went on campaign with a dozen or so volumes scattered around me. Now, while I journeyed once more in the Prince of Benevento’s calash, he dined in London at the expense of his fifth master, in hopes of some accident which might lead him to sleep at Westminster, among the saints, kings and sages; a sepulchre justly due his religiosity, loyalty and virtue.

Book XXXIX: Chapter 3: JOURNAL FROM PARIS TO VENICE: Jura – the Alps – Milan – Verona – A Roll-call of the Dead – The Brenta

En route, the 7th to the 10th of September 1833.

BkXXXIX:Chap3:Sec1

I left Paris on the 3rd of September 1833, taking the Simplon road via Pontarlier.

Salins, destroyed by fire, had been rebuilt; I preferred it in its ugliness and Spanish decrepitude. The Abbé d’Olivet was born on the banks of the Furieuse; Voltaire’s first schoolmaster, who welcomed his pupil to the Academy, had no similarity to his native stream.

The great storm which caused so many shipwrecks in the Channel assailed me on the Jura. I arrived at night among the wastes of the Lévier relay station. The caravanserai built of planks, brightly illuminated, full of travellers taking refuge, looked remarkably like the gathering-place for a witches’ Sabbath. I did not want to stop: they brought the horses. When it was necessary to shut the lamps on the calash, there was some difficulty; the hostess, a young and extremely pretty sorceress, leant her assistance while laughing. She took care to hold her light, protected by a glass cover, near her face, so as to be seen.

At Pontarlier, my former host, a great legitimist in his lifetime, was dead. I supped at the National Inn: a good omen for the newspaper of that name. Armand Carrel is the leader of those who did not tell lies during the July Days.

The Château de Joux protects the approaches to Pontarlier; it has seen two men whose memory the Revolution will preserve occupy its dungeons in succession, Mirabeau, and Toussaint-Louverture, the black Napoleon, imitated, and done to death, by the white Napoleon. ‘Toussaint,’ said Madame de Staël, ‘was sent to a prison in France where he perished in the most wretched manner. Perhaps Bonaparte only fails to remember that crime, because he has been less criticised for it than others.’

‘Toussaint L'Ouverture’

The Storied West Indies - Frederick Albion Ober (p194, 1900)

Internet Archive Book Images

The storm passed by: I suffered its worst violence between Pontarlier and Orbes. It made the mountains seem taller, made the bells chime in the hamlets, smothered the sound of the torrents with that of the thunder, and threw itself howling at my calash, like a black squall at a vessel’s sails. When flashes of lightning below lit the heather, you saw flocks of motionless sheep, heads hidden between their front legs, presenting their docked tails and woolly rumps to the flurries of rain and hail whipped along by the wind. The cry of a man shouting out the time, from the top of a mountain belfry, seemed like the voice of doom.

At Lausanne everything was smiling again: I had visited the town a few times before; I no longer knew anyone there.

At Bex, while they hitched the horses, which may have drawn Madame de Custine’s coffin, to my carriage, I leant against the wall of the house where my hostess of Fervaques died. She was noted, before the revolutionary Tribunal, for her long hair. In Rome I saw lovely blond hair recovered from a tomb.

In the Rhône valley, I met a little lass, almost naked, dancing with her goat; she begged charity of a rich well-dressed young man travelling post, with a courier in gold-braid in front and two lackeys seated at the back of the gleaming coach. And you imagine such a distribution of property can continue? Do you not think it justifies popular uprisings?

Sion recalled an epoch in my life: from being Secretary to the Rome Embassy, the First Consul nominated me as Plenipotentiary Minister to the Valais.

At Brig, I left the Jesuits trying hard to re-create what can no longer exist; established vainly at the feet of time, they were crushed beneath its weight, as their monastery was by the mountainous masses.

I was crossing the Alps for the tenth time; I had said what I had to say to them at various times and in the differing circumstances of my life. Forever regretful of what he has lost, forever wandering among memories, forever marching towards the grave, weeping and in isolation: that is Man.

Images borrowed, above all, from mountainous regions bear an obvious relationship to our lives; this one passes silently like the outflow from a spring; this makes a noise on its way like a torrent; that one pours out its existence like a cataract that terrifies and vanishes.

The Simplon already has a deserted air, like the life of Napoleon; like that life, it no longer possesses any glory; it is too great a work to belong to the little States to whom it has devolved. Genius has no family; its heritage fell by right of alienation to a plebeian people, who scratch away at it, planting a cabbage or growing a cedar.

Last time I crossed the Simplon, I was going to Rome as Ambassador; I have fallen; the shepherds I left behind on the mountain heights are still there: snow, clouds, shattered cliffs, pine forests, thunderous waters, endlessly surround the hut menaced by avalanches. The liveliest personage among those chalets is the she-goat. Why die? I know. Why be born? I have no idea. Yet you realise that the greatest suffering, moral suffering, the torments of the spirit are lessened among the habitations of that region of chamois and eagles. When I went to the Congress of Verona in 1822, the summit station on the Simplon was run by a Frenchwoman; in the midst of a cold night and a squall that prevented my seeing, she spoke to me of La Scala in Milan; she was waiting for ribbons from Paris; her voice, the only thing I could know of the woman, was very sweet in the wind and darkness.

The descent to Domo d’Ossola seemed more and more wonderful to me; some play of light and shadow increased the magic. One was caressed by a little breeze, in our ancient language called l’aure, a kind of advanced breath of the morning, bathed and perfumed with dew. I found Lake Maggiore again, where I was so sad in 1828, and which I glimpsed from the valley of Bellinzona in 1832. At Sesto-Calende, Italy proclaimed itself: a blind Paganini was singing and playing his violin by the edge of the lake as we crossed the Ticino.

I saw once more, on entering Milan, the magnificent avenue of tulip-trees which no one mentions: travellers apparently take them to be plane-trees. I protest against this silence, in memory of my savages: it is the slightest of ways in which America grants shade to Italy. One could also plant magnolias mixed with palm and orange trees at Genoa. But who dreams of that? Who thinks of adorning the earth? They leave all that to God. Governments are pre-occupied with their survival, and people prefer a cardboard tree in a puppet-theatre to the magnolia whose flowers might perfume Christopher Columbus’ birthplace.

In Milan, the vexation occasioned by passports is as stupid as it is brutal. I never pass through Verona without emotion: it was there that my active political career really began. What might have become of the world, if that career had not been interrupted by wretched envy, presented itself to my mind.

Verona, so animated in 1822 by the presence of the European sovereigns, had returned, in 1833, to silence; in those solitary streets the Congress seemed as distant as the Court of the Scaligeri and the Roman Senate. The amphitheatre, whose tiers had offered themselves to my eyes charged with a hundred thousand spectators, yawned empty; the buildings I had admired, beneath the illuminated embroidery of their architecture, were enveloped, grey and bare, by a rainy atmosphere.

How many ambitions were stirred among the actors at Verona! The destinies of how many nations were examined, discussed and weighed! Let us make a roll-call of those pursuers of dreams; let us open the book of the Day of Wrath: Liber scriptus proferetur;the book that is written will be revealed; Monarchs! Princes! Ministers! Here is your ambassador, here is your colleague returned to his post: where are you? Can you reply?

Alexander, Emperor of Russia? – Dead.

Francis II, Emperor of Austria? – Dead.

Louis XVIII, King of France? – Dead.

Charles X, King of France? – Dead.

George IV, King of England? – Dead.

Ferdinand I, King of Naples? – Dead.

The Grand Duke of Tuscany? – Dead.

Pope Pius VII? – Dead.

Charles-Félix, King of Sardinia? – Dead.

The Duke of Montmorency, Foreign Minister of France? – Dead.

Mr Canning, Foreign Minister of England? – Dead.

Count von Bernstorff, Foreign Minister of Prussia? – Dead.

Herr von Gentz, of the Austrian Chancellery? – Dead.

Cardinal Consalvi, Secretary of State to His Holiness? – Dead.

Monsieur de Serre, my colleague at the Congress? – Dead.

Monsieur d’Aspremont, my secretary at the Embassy? – Dead.

Count von Neipperg, husband of Napoleon’s widow? – Dead.

Countess Tolstoï? – Dead.

Her younger and elder son? – Dead.

My host at the Palazzo Lorenzi? – Dead.

If so many men appearing with me on the register of attendees at the Congress have been inscribed in the death register; if nations and royal dynasties have perished; if Poland has succumbed; if Spain is being torn apart once more; if I have been to Prague to inquire about the fugitive remnants of the great race whose representative I was in Verona, what then are the things of this earth? No one remembers the speeches we uttered around Prince Metternich’s table; but, oh the power of genius! No traveller can hear the lark sing in the fields around Verona without recalling Shakespeare. Each of us, searching the depths of their memory, finds a different obituary column, other extinguished feelings, other chimeras nursed in vain, like those of Herculaneum, at the breast of Hope. On leaving Verona, I was obliged to alter my way of measuring past time; I travelled back twenty-seven years, since I had not taken the route from Verona to Venice since 1806. At Brescia, Vicenza, and Padua, I traversed walls due to Palladio, Scamozzi, Franceschini, Nicholas of Pisa, and Fra Giovanni.

The banks of the Brenta failed my expectation; in my imagination they had remained more welcoming; the elevated dikes along the canal enclose too much marshland. Several villas have been demolished; but several elegant ones still remain. There, perhaps, Signor Procurante lives whom great ladies in need of sonnets disgust, whom two pretty girls are beginning to weary, whom music fatigues after a quarter of an hour, who finds Homer a mortal bore, who detests pious Aeneas, little Ascanius, idiotic King Latinus, vulgar Amata and insipid Lavinia; who cares little for Horace’s bad dinner on the road to Brindisi, who declares that he never reads Cicero, and still less Milton, a barbarian who ruins Tasso’s hell and his devil. ‘Alas!’ Candide whispered to Martin, ‘I fear this man has a sovereign contempt for our German poets!’

Despite my partial disappointment and the many gods among the little gardens, I was delighted with the silk trees (asclepias), the orange and fig-trees and the mildness of the air, I who, such a short time before, was travelling through German pine-woods and Czech mountains where the sun barely shows its face.

I arrived at Fusina, which Philippe de Comines and Montaigne call Chaffousine, at daybreak on the 10th of September. At ten thirty I embarked for Venice. My first care was to send to the post-office: there was nothing for me under either my direct address or my indirect one, via Paolo: of Madame la Duchesse de Berry, no news. I wrote to Count Griffi, the Ambassador of Naples to Florence, to ask him to let me know Her Royal Highness’ whereabouts.

‘The Entry of the French Ambassador in Venice in 1706’

Luca Carlevarijs, 1706 - 1708

The Rijksmuseum

Settling in, I resolved to wait patiently for the Princess: Satan sent me a temptation. I chose, through his diabolical suggestion, to live alone for a fortnight in the Hôtel de l’Europe, to the great detriment of the Legitimacy. I wished the august voyager a poor journey without considering that my restoration of King Henri V might be delayed by a half-month: I asked, as Danton did, forgiveness for it of God and men.

Book XXXIX: Chapter 4: DIGRESSIONS: Venice

Venice, Hôtel de l’Europe, 10th of September 1833.

BkXXXIX:Chap4:Sec1

‘Salve, Italum Regina.

Nec tu semper eris.

Hail, Queen of Italy.

Though you live not forever.’

(SANNAZAR)

‘O d’Italia dolente

Eterno lume.

Venezia!

Of sorrowful Italy

Eternal light.

O Venice!’

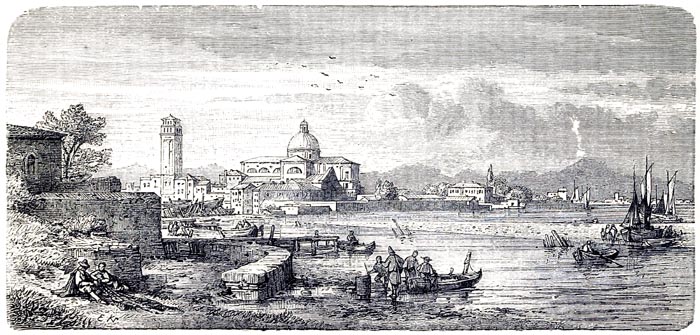

At Venice, one might think oneself at the tiller of a superb galley at anchor, on the Bucentaur, where they will give you dinner and from whose side you can view admirable things. My hotel, the Hôtel de l’Europe, is sited at the entrance to the Grand Canal facing the Dogana di Mare, Giudecca and San Giorgio Maggiore. When one travels the Grand Canal between its two rows of palaces, stamped by their centuries, so varied architecturally, when one takes oneself to the great and little piazzas, contemplates the Basilica and its domes, the Doge’s Palace, the Procuratie Nuove, the Zecca, the Torre dell’Orologio, the Campanile, and the Lion Column, all of it interspersed with the masts and sails of boats, the movements of the crowds and the gondolas, the azure sea and sky, the caprices of a dream or the play of an oriental imagination are no more fantastic. Cicéri sometimes paints and groups on canvas, for theatrical spectacles, monuments of every kind, every age, every country and every clime: such is Venice.

‘View of San Giorgio Maggiore from San Marco Square in Venice’

Anonymous, 1850 - 1876

The Rijksmuseum

Those gilded edifices, adorned profusely by Giorgione, Titian, Paulo Veronese, Tintoretto, Giovanni Bellini, Paris Bordone, and the two Palmas, are full of bronze, marble, granite, porphyry, precious antiques and rare manuscripts; their magic within matches their magic without; and when, in the subtle light that illuminates them, one discovers illustrious names and noble remembrances attached to their vaults, one cries with Philippe de Comines: ‘It is the most triumphant city I have ever seen!’

And yet she is no longer the Venice of Louis XI’s Minister, Venice wedded to the Adriatic and mistress of the seas; Venice who gave Constantinople emperors, Cyprus kings, Dalmatia, the Peloponnese, and Crete princes; Venice who humiliated the German Caesars, and welcomed suppliant Popes to her inviolable hearths; Venice of whom monarchs held it an honour to be citizens, to whom Petrarch, Plethon, and Bessarion bequeathed the remnants of Greek and Roman Letters saved from the barbarian wreckage; Venice who, a republic in the midst of feudal Europe, served as a shield for Christianity; Venice planter of the lion who set her feet upon the ramparts of Acre, Ascalon, Tyre, and defeated the Crescent at Lepanto; Venice whose Doges were the knights’ sages and merchants; Venice who subdued the Orient or bought her spices there, who brought from Greece conquered turbans or new-found masterpieces; Venice who emerged victorious from the thankless League of Cambrai; Venice who triumphed as much by her festivals, her courtesans and her arts, as by war and great men; Venice at once a Corinth, an Athens, a Carthage, decking her brow with rostral crowns and flowered diadems.

She is no longer the city I traversed when I visited the shores which witnessed her glory; but, thanks to her voluptuous breezes and her delightful waves, she keeps her charm; decadent countries above all need a beautiful climate. There is enough civilization in Venice for existence to play out its sensitivities there. The seductive sky prevents one needing a more than human dignity; an attractive strength emanates from those traces of grandeur, those remnants of the arts with which one is surrounded. The fragments of the ancient society that produced such things, leaves one no wish for the future. You love to feel yourself dying amongst all that is dying around you; you care for nothing but to adorn the rest of your life while she sheds her leaves. Nature, as quick to create fresh generations among the ruins as to clothe them with flowers, retains in the weakest of races the employments of passion and the enchantments of pleasure.

Venice no longer knows idolatry; she grew Christian on the island where she was nurtured, far from Attila’s brutality. The descendants of the Scipios, Paula and Eustochium, escaped the violence of Alaric in the caves of Bethlehem.

Different to all other cities, eldest daughter of ancient civilization and neither dishonoured nor conquered, Venice contains neither Roman remains nor Barbarian monuments. One sees nothing of what one sees in the north and west of Europe, amongst works of industrial progress; I speak of those new constructions, entire streets thrown up in haste, whose houses remain half-built or empty. What could they build here? Wretched shacks which would show the poverty of conception of the sons beside the magnificent genius of their fathers; pallid huts which could not compare with the gigantic residences of the Foscati and the Pesaro. When one thinks of the trowel full of mortar and handful of plaster whose application to a marble capitol urgent repairs have demanded, one is shocked. Rather the worm-eaten planks barring Greek or Moorish windows, the rags hung out to dry on elegant balconies, than the imprint of our century’s puny hand.

If only I might shut myself up in this city in harmony with my destiny, in this city of poets, which Dante, Petrarch and Byron passed through! If only I might finish writing my Memoirs by the light of the sun which falls on these pages! At this very moment the sun still scorches my Floridian savannahs and is setting here at the extremity of the Grand Canal. I no longer see it; but through a gap in those lonely palaces, its rays strike the globe of the Dogana, the spars of boats, the yards of vessels, and the gates of the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore. The monastery tower, changed to a rose-coloured pillar, is reflected in the waves; the white façade of the church is so brightly lit that I can see the tiniest of chiselled details. The shop walls of the Giudecca are painted with Titianesque light; the gondolas on the canal and in the harbour swim in the same glow. Venice is seated there at the edge of the sea, like a beautiful woman who will vanish with the day: the evening breeze lifts her fragrant hair; she is dying, hailed by all of Nature’s smiles and graces.

Book XXXIX: Chapter 5: Venetian Architecture – Antonio – The Abbé Bettio and Monsieur Gamba – Rooms in the Doge’s palace – Prisons

Venice, September 1833.

BkXXXIX:Chap5:Sec1

In Venice, in 1806, I remember the young Signor Armani, the Italian translator, or a friend of the translator, of Le Génie du Christianisme. His sister, so he said, was a nun (monaca). There was also a Jewish gentleman on his way to the farce of Napoleon’s Grand Sanhedrin who eyed my purse; then there was Monsieur Lagarde, head of French espionage, who had me to dinner: my translator, his sister, and the Sanhedrin Jew, are either dead or no longer live in Venice. In those days, I stayed at the White Lion Inn, near the Rialto; that inn has changed location. Almost facing my former hostelry is the Foscari Palace which is falling down. Away, all these old fragments of my life! Those ruins will drive me mad: let us speak of the present.

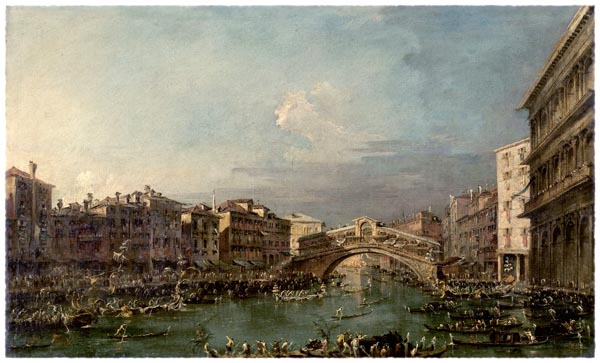

‘Regatta on the Canale Grande near the Rialto Bridge in Venice’

Francesco Guardi, 1780 - 1793

The Rijksmuseum

I have tried to describe the general effect of Venetian architecture; in order to give an account of the details I travelled up and down the Grand Canal, and visited and revisited St Mark’s Square.

Volumes are needed to cover the subject exhaustively. Count Cicognara’s Le Fabbriche più cospicue di Venezia shows the features of the monuments; but the presentation is not clear enough. I will content myself with noting two or three of the most common arrangements.

From the capital of a Corinthian column a semi-circle is described which ends on the capital of a second Corinthian column: in the midst of these a third is erected, of the same order and dimensions; from the capital of this central column two further semi-circles rise to left and right whose extremities also rest on the capitals of the other columns. The result of this design is that the arches, intersecting, give rise to ogives at the point of intersection (It is clear to me that the ogive whose origin, deemed mysterious, is sought far and wide, is born fortuitously from the intersection of two rounded arches; and it is found everywhere. Architects have merely succeeded in extracting it from the designs in which it appears) such that it forms a delightful blend of two architectural styles, the Roman rounded arch and the Arab ogive, or oriental Gothic. I here agree with present opinion, in supposing the Arab ogive to be Gothic, or of the Middle Ages, in origin; but it definitely exists in the monuments termed cyclopean: I have seen it in its pure form in the tombs of Argos.

The Doge’s Palace reveals tracery reproduced in other palaces, particularly the Foscari Palace: the pillars support ogive arches; these arches leave intervening spaces: in these spaces the architect has placed rose windows. Each rose window rests between the points of two arches. These rose-windows, which also touch one another at a point on their circumference, on the building’s façade, act like a row of wheels on which the rest of the building rises.

‘View of the Doge's Palace, Campanile and Surrounding Buildings in Venice’

Anonymous, 1850 - 1876

The Rijksmuseum

In most construction the base is usually substantial; the building reduces in thickness as it ascends into the sky. The Ducal Palace precisely contradicts this natural architecture: the base, pierced by light porticoes surmounted by a gallery with arabesques, indented with four-leaved clover tracery, supports an almost bare rectangular mass: it could be called a fortress on pillars, or rather an upturned building planted on its airy crown its thick roots in the air.

The architectural masks and heads decorating the Venetian buildings are noteworthy. On the Pescaro Palace, the entablature of the first storey, of Doric order, is decorated with the heads of giants; the Ionic order of the second storey is decorated with the heads of knights projecting horizontally from the wall, faces turned towards the water: some cased in a beaver, others with visor half-lowered; all with helmets whose plumes curl into the ornamentation of the cornice. Finally, on the third storey, of Corinthian order, there are heads of female statues with variously knotted hair.

At St Mark’s, embossed with domes, incrusted with mosaics, loaded incoherently with the spoils of the Orient, I thought myself at the same moment at San Vitale in Ravenna, Sancta Sophia in Constantinople, St Saviour in Jerusalem, and in those lesser churches of the Morea, Chios and Malta: St Mark’s, of composite Byzantine architecture is a monument of victory and conquest raised to the Cross, as the whole of Venice is a trophy. The most remarkable effect of its architecture is its shadiness under a bright sky; but today, the 10th of September, the dim light outdoors was in harmony with the sombre basilica. They have completed the forty hours of prayer required to obtain good weather. The fervour of the faithful, praying against rain, was profound: a grey and aqueous sky is like the plague to Venetians.

‘Clock tower, St. Mark's, and Doges' Palace, Piazzetta di San Marco, Venice’

Anonymous, 1890 - 1900

The Library of Congress

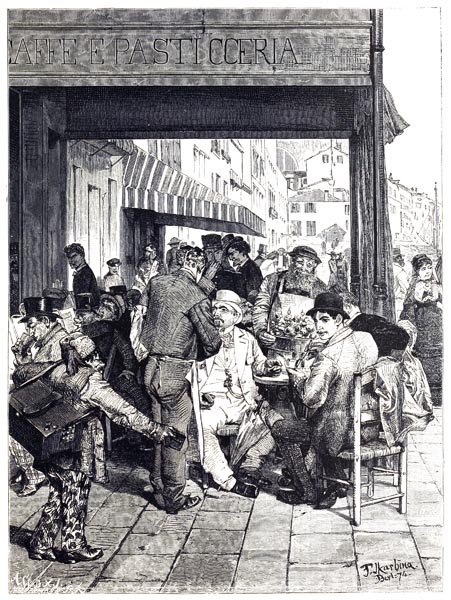

Our wishes have been granted: the evening was delightful; tonight I walked along the quay. The sea was smooth; the stars mingled with the scattered lights of the boats and other vessels anchored here and there. The cafes were full; but I saw no Punchinellos, Greeks, or Barbary Pirates: all that is done with. A Madonna, brightly lit at the entrance to a bridge, drew a crowd: girls on their knees said their paternosters devotedly; with her right hand she made the sign of the cross, with her left hand she stopped passers-by. Returning to my inn, I lay down and slept to the singing of the gondoliers stationed beneath my windows.

I have Antonio as my guide, the oldest and wisest cicerone in the land: he knows the palaces, statues and paintings by heart.

On the 11th of September, I visit the Abbé Bettio and Monsieur Gamba, curators at the library: they welcome me with extreme courtesy, even without a letter of recommendation.

Traversing the rooms of the Ducal Palace, you pass from marvel to marvel. There the entire history of Venice is revealed painted by the greatest masters: their pictures have been described a thousand times.

Among the antiquities, I noted, as all do, the group of Leda and the Swan, and the Ganymede said to be by Praxiteles. The swan is prodigious in terms of its grip and its voluptuousness; Leda is too complacent. The eagle of the Ganymede is not a true eagle; it looks like the gentlest of creatures. Ganymede, pleased to be carried off, is delightful: he speaks to the eagle who replies.

These antiquities are placed at either end of the magnificent halls of the library. With a poet’s sacred respect, I contemplated a manuscript of Dante’s, and gazed with a traveller’s avidity at Fra Mauro’s Mappa Mundi (1460). Africa however did not seemed as accurately traced as was said. Above all one ought to explore the archives of Venice: one would find there many precious documents.

From painted and gilded salons, I passed to dungeons and cells; the one palace offers a microcosm of society, pleasure and sorrow. The cells are beneath the leads, the dungeons at the level of the canal and on the second storey. They tell a thousand tales of secret strangulations and decapitations; by contrast, they tell of one prisoner who emerged, large, fat and ruddy from the oubliettes, after eighteen years in captivity: he had survived like a toad inside a stone. Honour to the human race! What a fine thing it is!

Perhaps philanthropic maxims adorn the walls and ceilings of dungeons, since our Revolution, so hostile to shedding blood ‘to that fearful stay, with a blow from an AXE, brought the light of day.’ In France, they cluttered the cells with victims whom they got rid of by cutting their throats; but they delivered the shades of those who were never there perhaps from the prisons of Venice; the gentle executioners who beheaded old men and children, the benign spectators who helped to guillotine women were moved by the progress of humanity, as is well proven by the opening of the Venetian dungeons. As for me, I am cold-hearted; I cannot match these heroes of sensibility. No old headless larvae were presented to my eyes beneath the Doge’s Palace; I only seemed to see in the dungeons of the aristocracy what the Christians saw when they shattered the idols, nests of mice escaping from the heads of the gods. That is what happens to all power eviscerated and exposed to the light; vermin emerge that worshippers have adored.

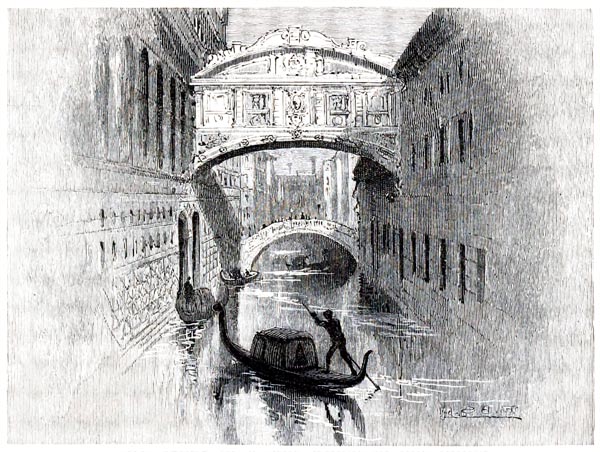

The Bridge of Sighs links the Ducal Palace to the city prison; it is divided in two lengthwise: on one side ordinary prisoners entered; on the other prisoners of State approached the Tribunal of Inquisitors or the Ten. The bridge is elegant on the outside, and the prison’s façade is admired: you cannot avoid beauty in Venice, even with regard to tyranny and misfortune! Pigeons make their nests on the window ledges of the gaol; little doves, covered with down, flap their wings and coo at the bars while waiting for their mother. In days past, they cloistered innocent creatures almost as they emerged from the cradle; their parents no longer saw them except through the visiting-room grille or the wicket gate.

‘The Bridge of Sighs, Venice’

Anonymous, 1890 - 1900

The Library of Congress

Book XXXIX: Chapter 6: The Prison of Silvio Pellico

Venice, September 1833.

BkXXXIX:Chap6:Sec1

You may well imagine that in Venice I was of necessity interested in Silvio Pellico. Monsieur Gamba told me that Abbé Bettio was keeper of the palace, and that by addressing him I could carry out my research. The excellent librarian, to whom I had recourse one morning, took a great bunch of keys and led me through several corridors and up various stairs, to the attic rooms of the author of Mie Prigioni.

‘Silvio Pellico’

Francesca da Rimini. A Tragedy - Silvio Pellico (p10, 1897)

The British Library

Monsieur Silvio Pellico was not wrong about one thing; he spoke of his gaol as of those famous dungeons in the air, called from their roofs sotti I piombi (above the leads). Those prisons are, or rather were five in number in the part of the Ducal Palace which is close to the Ponte della Paglia and the canal with its Bridge of Sighs. Pellico did not stay there; he was incarcerated at the other end of the palace, towards the Ponte di Canonico, in a building attached to the palace; a building transformed into a prison for political detainees in 1820. Moreover, he was also beneath the leads, since a sheath of that metal formed the roof of his hermitage.

The description the prisoner gave of his two rooms is exact to the last detail. Through the window of the first room, you overlook the heights of St Mark’s; you can see the wells in the interior courtyard of the palace, one end of the great square, various bell-towers of the city, and beyond the lagoon, on the horizon, the mountains towards Padua; you recognize the second room by its large window and its other high little window; through the large one Pellico saw his companions in misfortune in the central building facing him, and to his left, above, the sweet children who spoke to him from their mother’s casement.

Today all these rooms are abandoned, since no one inhabits them, not even prisoners; the window grilles have been removed, the walls and ceilings white-washed. The gentle and wise Abbé Bettio, lodged in this deserted part of the palace, is its peaceable and solitary guardian.

The rooms which immortalise Pellico’s captivity do not lack elevation; they have air, and a superb view; they are a poet’s prison; he had little to tell, as tyranny and absurdity admitted: but the death-sentence for speculative opinions! A dungeon in Moravia! Ten years of life, youth and talent! Mosquitoes, foul insects that ate me too in the Hôtel de l’Europe, hardened as I am by time and by the maringouins (mosquitoes) of the Floridas. Moreover I have often been worse lodged than Pellico was in his belvedere of the Ducal Palace, notably at the Prefecture of the doges of the French police: I was also obliged to climb on a table to see the light of day.

The author of Francesca da Rimini thought of Zanze in his gaol; in mine I sang of a young girl I had just seen die. I very much wanted to know what had become of Pellico’s little gaoler. I have set my people searching for her: if I find anything out, I will let you know.

Book XXXIX: Chapter 7: The Frari – The Accademia di Belle Arti – Titian’s Assumption – The Metopes of the Parthenon – Original drawings by Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael – The Church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo

Venice, September 1833.

BkXXXIX:Chap7:Sec1

A gondola dropped me at the Frari, where we French, accustomed as we are to the Greek or Gothic exteriors of our churches, are struck by the facade of a brick basilica unprepossessing and ordinary to the eye; but in the interior the harmony of line, and disposition of mass produces simplicity and a calm of composition which enchants.

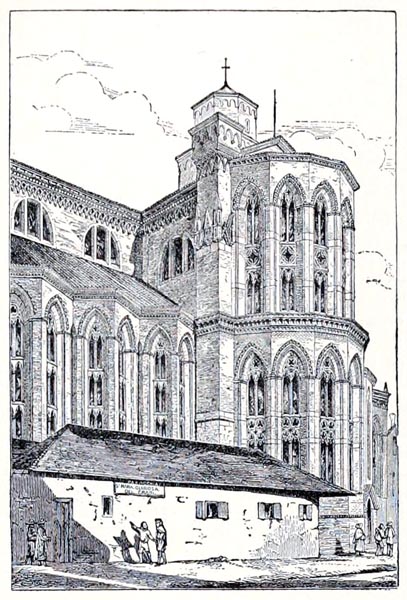

‘Church of the Frari, Venice’

A Dictionary of Architecture and Building: Biographical, Historical, and Descriptive - Russell Sturgis (p329, 1902)

Internet Archive Book Images

The Frari tombs, set in the lateral walls, adorn the edifice without cluttering it. The magnificence of the marble gleams on every side, the delightful ornamental leafage testifies to the end of ancient Venetian sculpture. On one of the paving stones in the nave one reads these words: Here lies Titian who emulated Zeuxis and Apelles. The stone lies beneath one of the painter’s masterpieces.

Canova’s sumptuous sepulchre lies not far from Titian’s slab: the sepulchre is a realisation of the monument which the sculptor had conceived for Titian himself, and which he later executed for the Arch-Duchess Marie-Christine. The remains of the creator of the Hebe and the Magdalen were not all buried together in this structure: thus Canova inhabits the realisation of a tomb made by him, but not for him, which is only a half-cenotaph.

From the Frari, I went to the Manfrin Gallery. The portrait of Ariosto is alive. Titian has painted his mother, an old woman of the people, grimy and ugly: the artist’s pride is felt in the exaggeration of the woman’s age and poverty.

At the Accademia di Belle Arti, I hastened to the painting of the Assumption, discovered by Count Cicognara: there are ten large male figures at the foot of the painting; note the man, gazing at Mary and transported by ecstasy, at the left. The Virgin, above this group, rises from a semi-circle of cherubs; there are a multitude of admirable faces lost in glorification: a woman’s head at the right, at the end of the curve is of indescribable beauty; two or three divine spirits are thrown horizontally across the sky in the bold and picturesque manner of Tintoretto. I am not sure if an angel standing does not display too earthly a sentiment of love. The Virgin’s proportions are good; she is covered by a red robe; her blue sash floats in the air; her eyes are raised towards the Eternal Father, appearing to her, at the culminating point. Four distinct colours, brown, green, red and blue, adorn the work: the aspect of it all is sombre, the character not idealised, but of an incomparable natural truth and vivacity: yet I prefer the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple, by the same painter, which can be seen in the same room.

Facing the Assumption, lit with much artifice, is the Miracle of St Mark, by Tintoretto, a vigorous drama which seems rather to have been carved from the canvas with mallet and chisel than painted with a brush.

I passed to the plaster casts of the Metopes from the Parthenon; these casts have a triple interest for me; in Athens I saw the empty spaces left behind by the ravages of Lord Elgin, and, in London, the marbles he removed whose casts I found in Venice. The errant destiny of these masterpieces is bound up with mine, and yet Phidias did not fashion my clay.

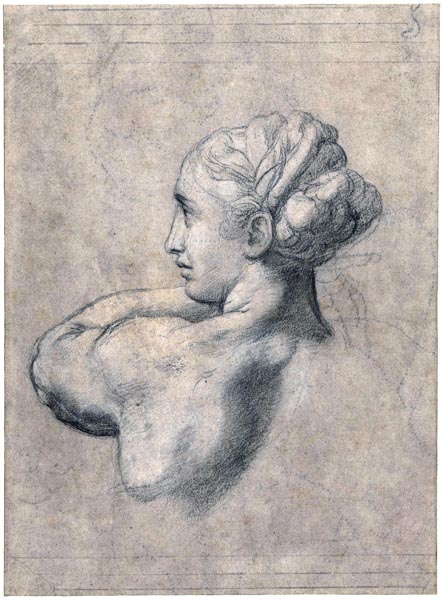

I could not tear myself away from the original drawings by Leonardo, Michelangelo and Raphael. Nothing is more engaging than these sketches of genius, owed only to its studies and caprices; it admits you to intimacy; it initiates you into its secrets; it allows you to learn by what degrees and effort it achieved perfection: you are delighted to see how it made mistakes, how it realised and redressed its errors. Those strokes of the crayon traced on a table corner, on a wretched scrap of paper, retain nature’s marvellous abundance and simplicity. When one thinks that Raphael’s hand has traversed those immortal fragments, one wishes oneself inside the glass that prevents one kissing the holy relics.

‘Study of a Head and Left Shoulder of a Woman’

Raphael, 1519 - 1520

The Rijksmuseum

I relaxed from the admiration I felt in the Accademia di Belle Arti by an admiration of a different sort in Santi Giovanni e Paolo; so one refreshes the spirit by a change of study. This church, whose unknown architect followed in the footsteps of Nicolo Pisano, is rich and vast. The apse which contains the main altar presents a kind of upright conch; two sanctuary altars abut this conch laterally; they are tall, narrow, with multi-centred arches, and separated from the apse by grooved planks.

The remains of the Doges Mocenigo, Morosini, Vendramin and other leaders of the Republic, rest here. Also the skin of Antonio Bragadino, defender of Famagusta, to which Tertullian’s expression can be applied: a living skin. These famous tombs inspire a deep and painful sentiment; Venice herself, the magnificent catafalque of her warrior magistrates, double coffin of their remains, is nothing but a living skin.

Stained glass and red draperies, by veiling the light in Santi Giovanni e Paolo, add to the religious effect. The countless pillars, brought from Greece and the Orient, have been planted in the basilica like alleys of foreign trees.

A storm arrived as I was wandering about the church: when the trumpet sounds who will wake all these dead? I would have said there were as many below Jerusalem in the Valley of Jehosaphat.

After these visits, returning to the Hôtel de l’Europe, I thanked God for having transported me from the pigs of Waldmünchen to the pictures of Venice.

Book XXXIX: Chapter 8: The Arsenal – Henri IV – A frigate leaving for America

Venice, September 1833.

BkXXXIX:Chap8:Sec1

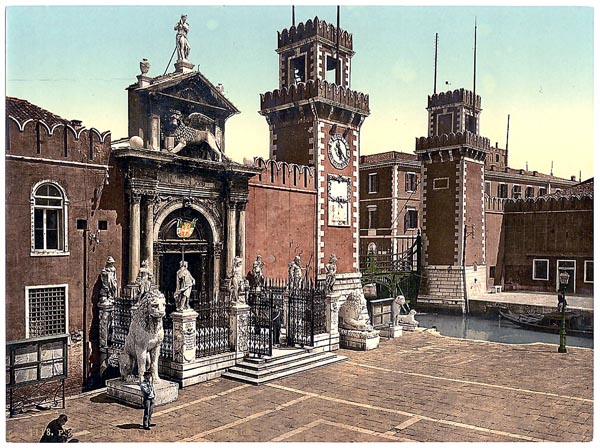

After my discovery of the prisons where Austrian materiality tried to stifle Italian intellect, I went to the Arsenal. No monarchy, however powerful, has offered an equivalent maritime factory.

‘The Arsenal, Venice’

Anonymous, 1890 - 1900

The Library of Congress

An immense space, enclosed by crenellated walls, surrounds four docks for high-sided vessels, the shipyards to build such vessels, the workshops for whatever concerns the navy and merchant marine, from rope-works to foundries for cannon, from the workshops where they shape the oars for gondolas to those where they carve out the keel of a seventy-four, from the rooms given over to antique weapons won at Constantinople, Cyprus, the Morea and Lepanto, to the rooms where modern weapons are displayed: the whole mingled with pillared galleries, architecture designed and created by the leading masters.

In the naval arsenals of Spain, England, France and Holland you see only what relates to the purpose of those arsenals; in Venice, the arts unite with industry. The monument to Admiral Emo, by Canova, awaits you beside the carcass of a ship; rows of cannon appear through long porticoes: the two colossal lions from Piraeus guard the gates of the dockyard from which frigates emerged to a world that Athens never knew, and that revealed the genius of modern Italy. Despite these fine Neptunian remains, the arsenal merely recalls those lines of Dante:

‘As in the arsenal in Venice,

they boil the clammy pitch in winter

to caulk those damaged ships

they cannot sail, and labouring there

one builds anew, another stops the ribs

of a vessel that has widely fared;

some hammer at the prow, some the stern;

some shape oars, and others twine the rope;

one mends the mainsail, another mends the jib:’.

All that activity is done with; the emptiness of nine tenths of the Arsenal, the unlit furnaces, the rusting boilers, the shipyard without workers, the rope-works without winding-wheels, bear witness to the same death which has struck the palaces. Instead of a crowd of carpenters, sail-makers, sailors, caulkers and ship’s apprentices, I glimpsed a few galley-slaves dragging their shackles: two of them were eating on a cannon’s breech-block; at that iron table they could at least dream of liberty.

In the past, when those galley-slaves rowed the Bucentaur, they threw a purple tunic over their stringy shoulders to make them look like kings: cleaving the waves with gilded oars, they exercised their labour to the rattle of chains, as in Bengal, at the Durga, the dances of the dancing girls, clothed in golden gauze, are accompanied by the tinkling of the bracelets with which their necks, arms and legs are adorned. The Venetian convicts wedded the Doge to the sea, and themselves renewed in slavery their indissoluble union.

Of the numerous fleets that carried the crusaders to the shores of Palestine and denied all foreign sails access to the Adriatic breezes, one Bucentaur in miniature remains, Napoleon’s canoe, a dugout of savages, and plans for vessels, traced in chalk on the blackboards of the Naval colleges.

A Frenchman arriving from Prague and waiting in Venice for Henri V’s mother cannot help but be touched to see Henri IV’s armour in the Venice Arsenal. The sword the Béarnais carried at the Battle of Ivry belongs with the armour: the sword is now missing.

By a decree of the Grand Council of Venice, of the 3rd of April 1600; Enrico di Borbone IV, re di Francia e di Navarra, con li figliuoli e discendenti suoi, sia annumerato tra I nobili di questo nostro maggiore consiglio: Henry IV of Bourbon, King of France and Navarre, with all his sons and descendants, will be counted among the nobles of this our Grand Council.

Charles X, Louis XIX and Henri V, descendants di Enrico di Borbone, are thus gentlemen of the Venetian Republic which no longer exists, as they are kings of France and Bohemia, as they are canons of St John Lateran in Rome, and always by virtue of Henri IV; I represented them in that capacity: they have lost their hoods and furs, and I have lost my Embassy. Yet I was so fine in my stall at St John Lateran! What a lovely church! What a beautiful sky! What admirable music! Those hymns have lasted longer than my greatness and that of my Royal Canon.

My glory bothered me in the Arsenal; it shone on my brow without my knowing it: Field-Marshal Palucci, Admiral and Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, recognized me by my horns of fire. He hastened to show me various curiosities himself; then, excusing himself for not being able to accompany me longer, because of a council meeting which he was off to preside over, he left me in the hands of a senior officer.

We met the captain of the frigate which was about to depart. He approached me without any fuss, and said, with that sailor’s easiness that I so love: ‘Monsieur le Vicomte (as if he had known me all his life) have you any commissions for America?’ – ‘No, captain: but give it my best compliments, it is a long time since I saw it!’

I cannot gaze at any ship without dying of envy to sail in her: if I were free, the first vessel travelling to the Indies would have its opportunity to carry me. How I regret not accompanying Captain Parry to the Polar Regions! My life is only enjoyable in the midst of sea and cloud: I always hope that it will vanish under sail. The heavy years we throw into the waves of time are not anchors; they do not arrest our course.

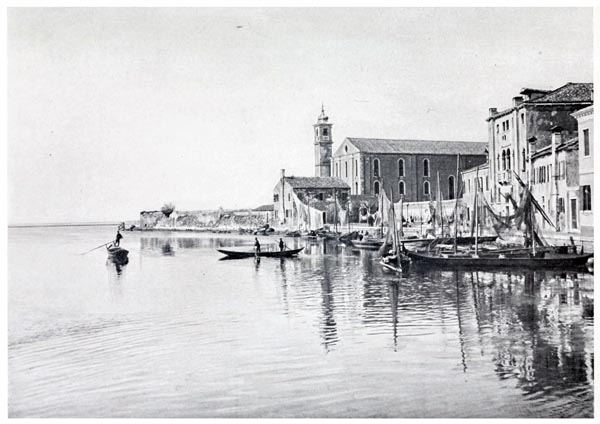

Book XXXIX: Chapter 9: Saint Christopher’s Cemetery

Venice, September 1833.

BkXXXIX:Chap9:Sec1

At the Arsenal, I was not far from the Isle of San Cristoforo, which serves today as a cemetery. The island contains a Capuchin monastery; the monastery has been razed and its site is merely an enclosure, square in shape. The graves are not very prolific, or at least they do not show above the levelled ground covered with grass. Against the west wall are piled half a dozen stone monuments; little crosses of blackened wood with a white date are scattered around the enclosure: this is how they inter the Venetians now whose ancestors rest in the mausoleums of the Frari and San Giovanni e Paolo. Society while expanding has abased itself; democracy has overcome death.

At the edge of the cemetery, to the east, one finds the sepulchres of Greek schismatics and those of Protestants; they are separated by a wall between and separated further from the Catholic burials by another wall: sad dissensions whose memory is perpetuated in the place where all quarrels end. Attached to the Greek cemetery is another entrenchment which protects a hole where they hurl children, born dead, into Limbo. Fortunate creatures! You have passed from the night of the maternal womb to the eternal night, without having traversed the light!

Near this hole, lie bones dug from the soil like roots, whenever they clear the ground for new graves: some, the oldest, are white and dry; others, recently unearthed, are yellow and moist. Lizards scamper among the remains, gliding between the teeth, traversing the eye-sockets and nostrils, emerging from the skulls’ mouths and ears, their homes or lairs. A few butterflies, symbols of the soul under skies descended from those beneath which the story of Psyche was invented, flutter among the mallow flowers growing between the bones. One cranium still bore hair the colour of mine. Poor old gondolier! Did you at least steer your boat better than I have steered mine?

A common grave remains open in the enclosure; a doctor has just descended there to lie beside his former patients. His black coffin was only covered with earth above, and his naked flank awaited the touch of another corpse’s flank to warm him. Antonio had deposited his wife there a fortnight ago, and the deceased doctor had dispatched her there. Antonio blessed the God who repays and revenges, and accepted his misfortune patiently. The individual coffins are conducted to this gloomy bazaar in individual gondolas followed by a priest in another gondola. As the gondolas are like coffins they suit the ceremony. A larger boat, the omnibus of the Cocytus, provides a service to the hospitals. Thus are revived the interments of Egypt and the myth of Charon and his barque.

In the cemetery towards Venice an octagonal chapel rises, consecrated to St Christopher. This saint, carrying a child on his shoulders over a ford, found him heavy: now, the child was the son of Mary and held the world in his hand; the altar painting depicts that great crossing.

‘Saint Christopher’

Lucas Cranach the Elder (German, 1472 - 1553)

Yale University Art Gallery

And I too chose to carry a child King, but I did not notice that he was asleep in his cradle with ten centuries or more: a burden too heavy for my arms. In the chapel I noted a wooden candlestick (the candle was out), a stoop used to bless the graves, and a booklet: Pars Ritualis romani pro usu ad exsequianda corpora defunctorum: Part of the Roman ritual to be used for the obsequies of the dead; when we are already forgotten, Religion, immortal parent, ever unwearied, weeps for us and follows us, exsequor fugam: followed in flight. A box contained a flame; God alone disposes of the spark of life. Two quatrains written on ordinary paper had been pasted inside the notice boards on a couple of doors of the building:

‘Quivi dell’ uom le frali spoglie ascose

Pallida morte, o passeggier, t’addita, etc.