François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXXVIII: Carlsbad, the Dauphine, Return to Paris 1833

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXXVIII: Chapter 1: Madame la Dauphine

- Book XXXVIII: Chapter 2: DIGRESSIONS: Springs – Mineral waters – History recalled

- Book XXXVIII: Chapter 3: MORE DIGRESSIONS: The Valley of the Tepla – Its Flora

- Book XXXVIII: Chapter 4: A last conversation with the Dauphine – Departure

- Book XXXVIII: Chapter 5: JOURNAL FROM CARLSBAD TO PARIS: Cynthia – Eger – Wallenstein

- Book XXXVIII: Chapter 6: Weissenstadt – The lady traveller – Berneck and memories – Bayreuth – Voltaire – Hollfeld – A church – The little basket-carrier – The innkeeper and his servant

- Book XXXVIII: Chapter 7: Bamberg – A hunchback – Wurtzburg – Its Canons – A drunken man – The swallow

- Book XXXVIII: Chapter 8: The inn at Wiesenbach – A German and his wife – My old age – Heidelberg – Pilgrims – Ruins - Mannheim

- Book XXXVIII: Chapter 9: The Rhine – The Palatinate – Mont-Tonnerre – Aristocractic Armies, Plebeian Armies – Monastery and castle – A solitary inn – Kaiserslautern – Sleep – Birds - Saarbruck

- Book XXXVIII: Chapter 10: Forbach to Paris

Book XXXVIII: Chapter 1: Madame la Dauphine

BkXXXVIII:Chap1:Sec1

The road from Prague to Carlsbad stretches through tedious plains stained with the blood of the Thirty Years’ War. Travelling those battlefields at night, I humbled myself before the God of Armies, who bears the sky on his arm like a shield. From the distance one saw little wooded mountains with water at their feet. The witty medical men of Carlsbad liken the road to the serpent of Asclepius that, descending the hill, came to drink of Hygieia’s goblet.

From the heights of the city tower, the Stadtturm, a tower mitred with a steeple, the sentinels sound their trumpet as soon as they see a traveller. I was welcomed with a joyous peal as a dying man, and everyone along the valley cried with delight: ‘Here comes an arthritic, a hypochondriac, a myope!’ Alas, I was better than that, I was an incurable.

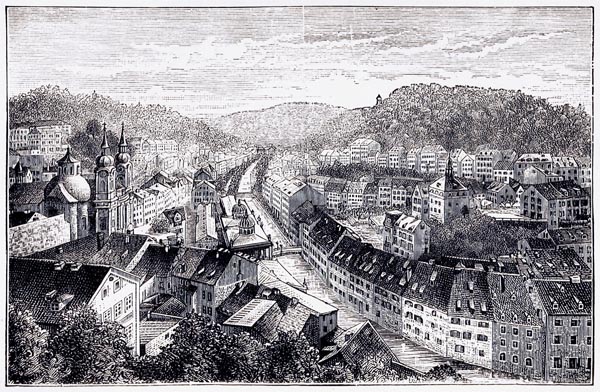

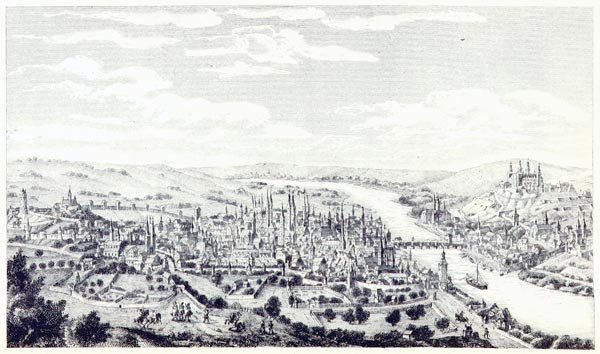

‘Karlsbad’

The watering places and mineral springs of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland - Edward Gutmann (p148, 1880)

Internet Archive Book Images

At seven in the morning, on the 31st of May I was installed at the Golden Ecu, an inn run on behalf of the Count of Bolzano, a very noble but ruined gentleman. Lodging at this hotel were the Count and Countess of Cossé (who had preceded me) and my compatriot General de Trogoff, former Palace Governor at Saint-Cloud, born at Landivisiau, beneath the light of the Landernau moon: a stocky little man he was an Austrian grenadier captain in Prague during the Revolution. He came from visiting his exiled lord, a successor to Saint Clodoald, a monk in his time at Saint-Cloud. Trogoff, after his pilgrimage, returned to Lower Brittany. He took with him a Hungarian nightingale and a Bohemian nightingale which lamented Tereus’ cruelty so much, they prevented everyone in the hotel from sleeping. Trogoff fed them on grated ox-heart, without succeeding in bringing an end to their grief.

Et moestis late loca questibus implet:

filling the place around with mournful cries.

We embraced each other as Bretons do, Trogoff and I. The general, short and square like a Celt from La Cournaille was subtle beneath his apparent frankness, and an amusing story-teller. He was popular with Madame la Dauphine, and as he knew German, she took him along on her walks. Informed of my arrival by Madame de Cossé, she proposed I see her at nine-thirty or midday: at midday I was at her residence.

She occupied an isolated house, at the extremity of the town, on the right bank of the River Tepla, a little river which flows from the mountains and traverses the length of Carlsbad. Mounting the stairs to the Princess’ apartment I was anxious: I was about to meet, for the first time, this perfect model of human suffering, this Antigone of Christianity. I had not had ten minutes speech with Madame la Dauphine in my life; during the time of her brief prosperity she had scarcely addressed two words to me; she always showed embarrassment towards me. Though I had never written to her or spoken about her other than with profound admiration, Madame la Dauphine necessarily nourished in regard to myself the prejudices of the ante-chamber set among whom she lived: the Royal Family vegetated in isolation in that citadel of foolishness and envy, which new generations besieged without being able to penetrate.

A servant opened the door to me: I saw Madame la Dauphine sitting on a sofa between two windows, in the depths of the room, embroidering a piece of tapestry by hand. I entered in such a state that I did not know if I could approach the Princess.

She raised her head, which had been bowed over her work as if to hide her own emotion, and addressing me said: ‘I am happy to see you, Monsieur de Chateaubriand; the King informed me you would be arriving. You have spent the night here? You must be tired.’

I respectfully presented Madame la Duchesse de Berry’s letters; she took them, placed them on the settee beside her, and said: ‘Sit down, sit down.’ Then she took up her embroidery again with a rapid, mechanical and convulsive movement.

I said nothing; Madame la Dauphine maintained her silence: there was the sound of the needle prick and the passage of the wool as the Princess tugged it through the canvas, on which I saw a few tears fall. The illustrious sufferer wiped them from her eyes with the back of her hand, and without raising her head, said: ‘How is my sister? She is very unfortunate, very unfortunate. I am very sorry for her, very sorry.’ These brief repetitions sought in vain to initiate a conversation for which the two interlocutors lacked words. The Dauphine’s eyes, reddened from constant weeping, gave her a beauty which matched that of the Spasimo Virgin.

‘Madame,’ I at last replied, ‘Madame la Duchesse de Berry is indeed very unfortunate; she has charged me with coming to place her children under your protection during her imprisonment. It is a great relief to her in her trouble to think that Henri V has a second mother in Your Majesty.’

Pascal was right to link the greatness with the wretchedness of mankind: who would have thought that Madame la Dauphine considered her titles of Queen and Majesty, which were so natural to her and whose vanity she knew, to be worth anything? Well, that word Majesty was still a magic word; it lightened the Princess’ brow and dispelled the clouds for a moment; they soon returned there like a diadem.

‘Oh, no, Monsieur de Chateaubriand, no,’ the Princess said gazing at me and suspending her work, I am not Queen.’ – ‘You are, Madame, you are according to the laws of the realm: Monseigneur le Dauphin could only abdicate because he was King. France regards you as its Queen, and you will be a mother to Henri V.’

The Dauphine did not argue: that little weakness, by revealing the woman, obscured the splendour of hosts of other grandeurs, giving them a kind of charm, and bringing them nearer to the human condition.

I read, in a loud voice, my letter of accreditation, in which Madame la Duchesse de Berry explained about her marriage, ordered me to appear in Prague, asked to retain her title of French princess, and placed her children in her sister-in-law’s care.

The princess had resumed her embroidery; after my speech she said: ‘Madame la Duchesse de Berry is right to put her trust in me. That is fine, Monsieur de Chateaubriand, fine: tell my sister-in-law I am very sorry for her.’

This insistence of Madame la Dauphine’s on saying how sorry she was for Madame la Duchesse de Berry, while going no further, showed me how little sympathy there was, fundamentally, between those two spirits. It also seemed to me that an involuntary emotion had agitated that saintly heart. Rivalry in misfortune! Yet Marie-Antoinette’s daughter had nothing to fear in that contest; the palm remained with her.

‘If Madame,’ I replied, ‘will read the letter Madame la Duchesse de Berry has written, and that addressed to her children, she will perhaps discover further clarification. I hope Madame will give me a letter to carry back to Blaye.’

The letters were written in lemon-juice. ‘I know nothing of this,’ said the Princess, ‘how are we to proceed?’ I suggested a stove and some pieces of kindling; Madame rang the bell whose cord hung behind the sofa. A valet de chambre appeared, was given his orders, and set up the apparatus on the landing, outside the door of the room. Madame rose and we went to the stove. We set it on a little table by the staircase. I took one of the letters and held it parallel to the flames. Madame la Dauphine watched me and smiled because I had no success. She said: ‘Here, give it to me, I will try.’ She passed the letter over the flame; Madame la Duchesse de Berry’s large round hand appeared: the same was done for the second letter. I congratulated Madame on her success. A strange scene: the daughter of Louis XVI, at the top of a staircase in Carlsbad with me, deciphering mysterious characters sent by the prisoner of Blaye to the prisoner of the Temple!

We returned to our seat in the salon. The Dauphine read the letter addressed to her. Madame la Duchesse de Berry thanked her sister-in-law for the role she had adopted regarding her misfortune, recommended her children to her, and in particular placed her son under the guardianship of his virtuous aunt. The letter to the children consisted of a few tender words. The Duchesse de Berry charged Henri with making himself worthy of France.

Madame la Dauphine said: ‘My sister-in-law does me justice, I have suffered with her. She has suffered greatly, greatly. Tell her I will take care of Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux. I love him dearly. How did he seem to you? His health is fine, is it not? He is strong, though somewhat nervous.’

I spent two hours tête-à-tête with Madame, an honour rarely granted: she seemed content. Having known me only from hostile accounts, she had no doubt thought me a violent gentleman, swollen with a sense of my own importance; she was grateful to find me a human being and a decent man. She said, cordially: ‘I am going out to take the waters; we dine at three, come if you are not in need of rest. I would like to see you there if it will not fatigue you too much.’

I do not know to what I owed my success; but certainly the ice was broken, the obstacle removed; that gaze which had rested, in the Temple, on that of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, rested with kindness on a humble servant.

Nevertheless, though I had succeeded in setting the Dauphine at ease, I felt extremely constrained: the fear of exceeding certain limits robbed me even of the facility for those commonplaces I shared with Charles X. Whether I lacked the secret of how to extract whatever was sublime from Madame’s soul; or whether the respect I felt closed the door on thoughtful communication, I experienced a distressing barrenness which emanated from my self.

At three, I went to Madame la Dauphine’s. There I found Madame la Comtesse Esterhazy and her daughter, Madame d’Agoult, and Messieurs O’Hegerty the younger and de Trogoff; they had the honour of dining with the Princess. Countess Esterhazy, once beautiful, is still handsome: she had been friends with Monsieur le Duc de Blacas in Rome. It is said she involves herself in politics and taught Prince von Metternich all he knows. When Madame was sent to Vienna, on leaving the Temple, she met Countess Esterhazy who became her companion. I noticed she listened attentively to my conversation; next day she had the naivety to say in front of me that she had spent the night writing. She was preparing to depart for Prague, a secret interview having been fixed at a location convenient to Monsieur de Blacas; from there, she went to Vienna. Old relationships rejuvenated by espionage! Such affairs and such pleasures! Mademoiselle Esterhazy is not pretty, and has a caustic and spiteful manner.

Vicomtesse d’Agoult, pious these days, is an important personage as one finds her in the sanctuaries of every princess. She promotes her family whenever she can, when speaking to everyone, particularly to me: I had the goodness to find positions for her nephews; she has as many as the late Arch-Chancellor Cambacérès.

The dinner was so poor and so meagre I left dying of hunger; it was served in Madame la Dauphine’s drawing room, since she had no dining room. After the meal, we rose from the table; Madame went back to her sofa, and took up her embroidery, and we made a circle around her. Trogoff told stories, Madame enjoyed them. She was particularly interested in the female element. There was a question regarding the Duchess de Guiche: ‘Plaits don’t suit her,’ said the Dauphine, to my great astonishment.

From her sofa, Madame could see, through the window, what was happening outside: she named the passers-by male and female. Two little horses arrived with two riders dressed in tartan; Madame stopped work, gazed and said: ‘It is Madame. (I forget the name) taking her children to the mountains.’ Marie-Thérèse curious, knowing the local gossip, the Princess of thrones and scaffolds descending from her heights to the level of other women, these things interested me singularly; I observed them with a kind of philosophic tenderness.

At five the Dauphine went out in her calash; at seven, I returned for the evening audience. The same establishment: Madame on the sofa, the dinner guests and half a dozen ladies young and old, partakers of the waters, added to the circle. The Dauphine made a touching but visible effort to be gracious; she had a word for all of us. She spoke to me several times, feigning to name me in order to make me known; but between each sentence she fell back into her distraction. Her needle multiplied its movements, her face drew nearer to her embroidery; I saw the Princess in profile and was struck by a sinister resemblance: Madame had the look of her father about her; when I saw her head bowed as beneath the sword of grief, I thought I saw that of Louis XVI waiting for the blade to fall.

At half past eight the evening audience ended; I went to bed overwhelmed by sleep and lassitude.

On Saturday, the 1st of June, I was up at five; at six I went to the Mühlenbad (Mill Baths): those taking the waters, male and female, crowded round the spring, walked beneath a gallery with wooden columns, or in the garden attached to the gallery, Madame la Dauphine arrived, dressed in a shabby robe of grey silk; round her shoulders hung a worn-out shawl and she had an old hat on her head. She looked as though she had patched her clothes together, like her mother in the Conciergerie. Monsieur O’Hegerty, her riding instructor, gave her his arm. She mingled with the crowd and presented her cup to the ladies who doled out the spring-water. No one paid any attention to Madame la Comtesse de Marne. Maria-Theresa, her grand-mother, had the Mill Baths rebuilt in 1762; she also sponsored the bell-towers in Carlsbad that were to summon her grand-daughter to the foot of the cross.

Madame having entered the garden, I advanced towards her: she seemed surprised with that courtier’s attention. I rarely rose so early for royalty, except perhaps on the 14th of February 1820, when I went to seek the Duc de Berry at the Opera. The Princess allowed me half a dozen circuits of the garden at her side, talking pleasantly, and told me she would receive me at two o’clock, and would give me a letter. I left her, discreetly; I lunched hastily, and spent the remaining time walking in the valley.

Book XXXVIII: Chapter 2: DIGRESSIONS: Springs – Mineral waters – History recalled

Carlsbad, 1st of June 1833.

BkXXXVIII:Chap2:Sec1

As a Frenchman, I found only painful memories in Carlsbad. The town takes its name from Charles IV, King of Bohemia, who went there to be healed of his three wounds received at Crecy fighting next to his father Jan. Lobkowitz claims Jan was killed by a Scotsman; a circumstance unknown to historians.

‘Sed cum Gallorum fines et amica tuetur

Arva, Caledonia cuspide fossus obit.’

‘While he was defending the borders of Gaul and the fields of his allies, he died pierced by a Caledonian lance.’

Did the poet add Caledonia to make up the quantity? In 1346, Edward III was at war with David II, and the Scots were allies of Philip VI.

The death of Jan the Blind of Bohemia at Crécy is one of the most heroic and moving moments in history. Jan wished to go to the aid of his son Charles; he said to his companions: ‘ “My lords, you are my friends: I request you to lead me so far forward that I might land a blow with my sword”; they replied that they would willingly do so. The King of Bohemia rode forward, so as to land a blow with his sword, or four or more, and fought very vigorously as did those of his company; so far forward that he drove in among the English, and all remained there, and were found the next day in that place around their lord, and all their horses lying there together.’

Few know that Jan of Bohemia’s heart was interred at Montargis, in the Dominican Church, and that the remains of a weathered inscription can be read on the tomb there: ‘He died leading his men, commending them all to God the Father. Pray God for this sweet King.’

May this memorial to a Frenchman make amends for French ingratitude, when in the days of our fresh disasters we appalled Heaven with our sacrilege, and hurled from his tomb a Prince who died for us in our former days of misfortune.

At Carlsbad the chronicles say that when Charles IV, King Jan’s son, was out hunting, one of his dogs chasing a deer fell from a hilltop into a pool of seething water. His barking brought the huntsmen running, and so the Sprudel spring was discovered. A pig scalded by the waters of Teplitz revealed them to a swineherd.

Such are the German legends. I have been to Corinth; the ruins of the Temple of Aphrodite and her sacred courtesans were scattered above Glycera’s ashes, but the Fountain of Pirene, born of a nymph’s tears, still flowed among the oleanders where the winged-horse Pegasus flew in the days of the Muses. The waves of a harbour empty of vessels bathed the fallen columns whose capitals were washed by the sea, like the heads of young drowned girls laid out on the sand; myrtle had grown through their hair and replaced the acanthus leaves; such are the legends of Greece.

There are eight springs in Carlsbad; the most famous is the Sprudel, discovered by the deer-hound. The spring emerges from the ground between the Church and the River Tepla with a hollow noise and white steam; it leaps in irregular spurts to a height of six or seven feet. The springs of Iceland alone are superior to the Sprudel, but no one goes to seek their health on the wilds of Hecla where life expires; where the summer’s day, emerging from daylight, has neither sunset nor dawn; where the winter’s night, re-born out of night, lacks daybreak or twilight.

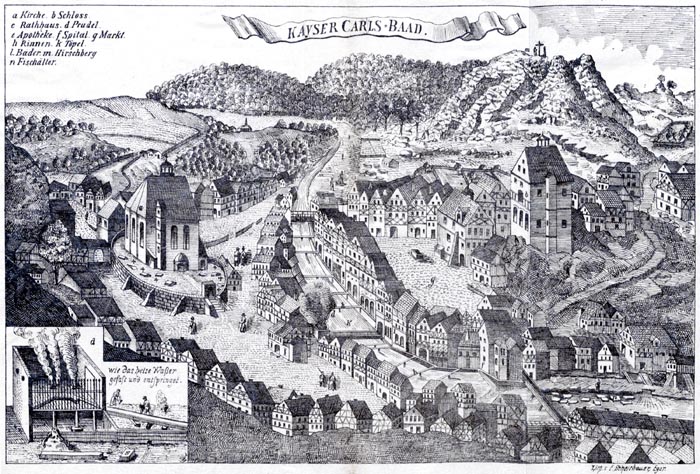

‘Kayser Carls-Baad’

Geschichte der Königlichen Stadt Karlsbad - Vincenz Proekl (p71, 1883)

The British Library

The waters of the Sprudel will boil eggs and serve for cleaning tableware; this fine phenomenon has found employment on behalf of Carlsbad households: a symbol of genius degraded by lending its power to base tasks.

Monsieur Alexander Dumas has made a free translation of Lobkowitz’s Latin ode on the Sprudel.

Fons heliconiadum etc.

‘Fount sacred to the poet’s rhyming feet,

Where is the hearth that feeds your secret heat?

Whence your burning bed of lime and sulphur?

That flame whose vapours Etna lights no more,

Does it forge unknown channels where you pour,

As neighbour of the Styx, your seething water?’

Carlsbad is the common rendezvous for sovereigns; they need to cure themselves of their crowns for their sake and ours.

They publish a daily list of visitors to the Sprudel: in the ancient records you can read the names of the greatest poets and literary men of the North, Gurowski, Traller, Dunker, Weisse, Herder, Goethe; I would have liked to find that of Schiller, the object of my preference. On the current page, among the host of obscure arrivals, can be seen the name of the Comtesse de Marne; it is only printed in small capitals.

In 1830, at the very moment of the royal family’s exit from Saint-Cloud, Christophe’s widow and daughters were taking the waters at Carlsbad. Their Haitian Majesties have settled in Tuscany near Their Napoleonic Majesties. King Christophe’s youngest daughter, very well-educated and pretty, died at Pisa: free now, her ebony beauty rests beneath the porticos of the Campo Santo, far from the fields of sugar-cane and the mangroves in whose shade she was born a slave.

At Carlsbad, in 1826, there appeared an English lady from Calcutta, come from the figs of the banyan-tree to the olives of Bohemia, from the Ganges’ sun to that of the Tepla; she faded like a ray of Indian sunlight lost in the cold of night. The sight of cemeteries in places consecrated to health, is melancholy: there, young women sleep, strangers to one another: on their tombs are inscribed the length of their life, and the name of their country: it is as if one passed through a glass-house where flowers from every clime are cultivated, their names being written according to convention at the foot of each flower.

Indigenous law has come to anticipate the needs of death abroad; foreseeing the decease of travellers far from their own land, it permits later exhumation. So I could rest in the cemetery of St Andrew for a dozen years and nothing would hinder the testamentary arrangements regarding these Memoirs. If Madam la Dauphine died here, would French law permit the return of her remains? That would be a delicate point of controversy among the professors of doctrine and the casuists of proscription.

The waters of Carlsbad are, they say, good for the liver and bad for the teeth. As to the liver, I would not know; but there are plenty of toothless people in Carlsbad; the years perhaps rather than the waters are responsible for the fact: time is a false insignia and a great puller of teeth.

Does it not seem to you as if I were setting out again to write the masterpiece of an unknown? One thing leads me to another; I travel from Iceland to the Indies.

‘There are the Apennines and here are the Caucasus.’

And yet I have not yet left the valley of the Tepla.

Book XXXVIII: Chapter 3: MORE DIGRESSIONS: The Valley of the Tepla – Its Flora

BkXXXVIII:Chap3:Sec1

In order to view the Tepla Valley at a glance, I climbed a hill, through a pinewood: the perpendicular columns of these trees formed an acute angle with the sloping ground; some showed their crowns, two-thirds, half, or a quarter of their trunk where others placed their roots.

I will always love woods: the Flora of Carlsbad, whose breath had embroidered the grass beneath my feet, seemed delightful to me; I found fingered sedge (carex digitata), deadly nightshade (atropa belladonna), common purple loosestrife (lythrum salicaria), St John’s wort (hypericum perforatum), hardy lily of the valley (convallaria majalis) and grey willow (salix cinerea): sweet subjects of my first herbals.

Behold my youth that comes hanging its memories from the stems of those plants I recognized in passing. Do you remember my botanical studies among the Seminoles, the evening-primroses (oenotheras), the water-lilies (nymphaeas) among whom I set my Floridian girls, the garlands of clematis they twined round some terrapin, our slumber on the island by the lake-shore, the rain of magnolia petals which fell on our heads? I dare not calculate how old my fickle painted lady would be now; what would I gather today from her brow: the wrinkles that cover mine? No doubt she sleeps eternally among the roots of a cypress grove in Alabama; and I who hold these distant, solitary, unknown memories in my mind, I live! I am in Bohemia, not with Atala and Céluta, but with Madame la Dauphine who will give me a letter for Madame la Duchesse de Berry.

‘Carlsbad in Jahre 1726’

Geschichte der Königlichen Stadt Karlsbad - Vincenz Proekl (p23, 1883)

The British Library

Book XXXVIII: Chapter 4: A last conversation with the Dauphine – Departure

BkXXXVIII:Chap4:Sec1

At one o’clock, I was at Madame la Dauphine’s disposal.

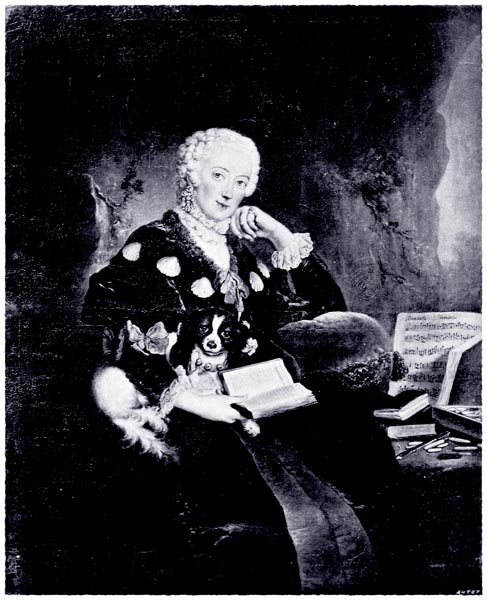

‘Madame Première, Duchesse d'Angoulême, Daughter of Louis XVI, Born at Versailles on December 19th, 1778’

Sophie Dawes, Queen of Chantilly - Violette M. Montagu (p74, 1912)

Internet Archive Book Images

‘You wish to leave today, Monsieur de Chateaubriand?’

‘– If Your Majesty will allow me: I will endeavour to see Madame de Berry again in France; otherwise I would be obliged to make a voyage to Sicily, and Her Royal Highness would be deprived for too long of the reply she awaits.’

‘– Here is a message for her. I have avoided mentioning your name in order not to compromise you in case of eventualities. Read it.’

I read the note; it was wholly in Madame la Dauphine’s hand: I have copied it exactly.

‘Carlsbad, this 31st of May 1833.

I have experienced real satisfaction, my dear sister, in at last receiving news of you directly. I am sorry for you with all my soul. Depend always upon my constant interest in you and above all in your dear children, who are more precious than ever to me. My existence, as long as I live, will be dedicated to them. I have not yet been able to execute your commissions to our family, my health requiring that I come here to take the waters. But I will acquit myself of them as soon as I return among them, and please believe that we, they and I, will always share the same feelings about everything.

Adieu, my dear sister, I am sorry for you from the depths of my heart, and embrace you tenderly.

M-T.’

I was struck by the reticence in this note: certain vague expressions of attachment barely concealed the deeper coolness. I made a respectful comment, and again pleaded the cause of the unfortunate prisoner. Madame replied that the King would decide. She promised me to interest herself in her sister-in-law; but there was scant cordiality in the Dauphine’s voice and manner; rather one sensed an inner irritation. The game seemed lost as far as my client was concerned. I fell back on Henri V. I thought I owed the Princess the sincerity which I had always employed at my peril in order to enlighten the Bourbons; I spoke to her without flattery or circumlocution regarding the education of Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux. ‘I know Madame has read with sympathy the pamphlet at the end of which I express various ideas concerning Henri V’s education. I fear lest the child’s surroundings are harmful to him: Messieurs de Damas, de Blacas and Latil are not popular.’

Madame acknowledged it; she even denied Monsieur de Damas suddenly, while saying a few words in honour of his courage, probity and religiosity.

‘In September Henri V will be of age: do you not think it would be helpful to form a council round him into which might be introduced those men against whom France raises least objection?

‘– Monsieur de Chateaubriand, by multiplying counsellors one multiplies the sources of advice; and then, who would you propose that the King choose?’

‘– Monsieur de Villèle.’

Madame, who was embroidering, arrested her needle, looked at me in astonishment, and astonished me in turn by uttering a judicious critique of the character and intellect of Monsieur de Villèle. She did not consider him an effective administrator.

‘Madame is too harsh,’ I said: ‘Monsieur de Villèle is a man of order, conciliation, moderation, and calm whose resources are endless; though he lacked the ambition to occupy the place of Premier, for which he was unacceptable, he is a Minister to retain indefinitely in the King’s council; he is irreplaceable. His presence beside Henri V would have the greatest effect.’

‘– I thought you disliked Monsieur de Villèle?’

‘- I would despise myself if, after the fall of the monarchy, I continued to nourish some feeling of petty rivalry. Our royalist divisions have already done enough harm; I abjure them with all my heart and am ready to ask pardon of those who have offended me. I beg Your Majesty to believe that it is neither a false display of generosity, nor a marker laid down in anticipation of future fortune. What have I to expect from Charles X in exile? If a Restoration is to occur, shall I not be in the depths of my grave?’

Madame looked at me affably; she had the goodness to praise me for those few words: ‘Very fine, Monsieur de Chateaubriand!’ She seemed perpetually surprised to find a Chateaubriand so different to how he had been painted.

‘– There is someone else, Madame, whom you could call on,’ I continued: ‘my noble friend, Monsieur Lainé. We are three men who ought never to swear loyalty to Philippe: I, Monsieur Lainé, and Monsieur Royer-Collard. Outside the government, and in diverse roles, we might have formed a triumvirate of some value. Monsieur Lainé took the oath through frailty, Monsieur Royer-Collard through pride; the first died of his frailty; the second lives by his pride, since he stands by what he has done, being unable to do anything which is not admirable.’

‘– You are satisfied with Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux?’

‘– I found him delightful. They say Your Majesty spoils him a little.’

‘– Oh: not so! His health, are you satisfied with that?’

‘– He seems wonderfully well; he is delicate and a little pale.’

‘– His complexion often varies; but he is of a nervous disposition. Monsieur le Dauphin is highly esteemed in the army, is he not? Highly esteemed? They remember him, do they not?’

This brusque question, without connection with what we had been saying, revealed a secret wound that the days of Saint-Cloud and Rambouillet had left in the Dauphine’s heart. She brought up her husband’s name to reassure herself; I hastened to anticipate the thoughts of the Princess and the wife; I affirmed, rightly, that the army would always remember his impartiality, virtues and courage as a General.

Seeing that the hour for her walk was nearing:

‘– Has Your Majesty any orders to give me? I fear to seem importunate.’

‘– Tell your friends how I love France; that they know I am truly French. I charge you particularly with saying that; you will give me pleasure in saying it: I truly regret France, I regret France deeply.’

‘– Ah, Madame, what has that same France not done to you: you who suffered so greatly, how can you still feel homesick for her?’

‘– No, no, Monsieur de Chateaubriand, do not forget; tell everyone that I am French, that I am French.’

Madame left me; I was obliged to halt on the stairs before leaving; I would have not dared show myself in the street; my tears still wet my eyes in recalling that scene.

Returning to my inn, I changed into my travelling clothes. While they were getting the carriage ready, Trogoff chattered away. He told me again that the Dauphine was very satisfied with me, that she did not hide it, and that she told anyone who wished to hear: ‘Your trip here has been very important!’ Trogoff cried, trying to drown the singing of his two nightingales, ‘You will see a result from it all!’ I had no belief it would have any result.

I was right; that very evening Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux was expected. Even though everyone knew of his arrival, they made a mystery of it. I took care to show I myself knew of the secret.

At six in the evening, I set off for Paris. However immense the misfortune of Prague, the pettiness of a Prince’s life reduced to that alone is hard to swallow; to drink it to the last drop, he only needed to burn down the Palace and be drunk on ardent faith. – Alas! A modern Symmachus, I wep the desertion of the altars; I raise my hands towards the Capitol; I invoke the majesty of Rome! But what if the god has turned to wood and Rome can no longer be rekindled from the dust?

Book XXXVIII: Chapter 5: JOURNAL FROM CARLSBAD TO PARIS: Cynthia – Eger – Wallenstein

BkXXXVIII:Chap5:Sec1

The road from Carlsbad as far as Ellbogen, along the Eger, is pleasant. The castle above this little town is twelfth century and is sited like a sentinel on a rock, at the entrance to a valley gorge. The foot of the rock, covered with trees, is contained in a bend of the Eger; from that fact the town and Castle take their name, Ellbogen (elbow). The keep was lit by the last rays of the sun when I saw it from the highroad. Above the mountains and the woods, there hung a twisted column of smoke from a foundry.

I left the relay post at Zwoda at nine-thirty. I followed the road along which Vauvenargues passed during the retreat from Prague; that young man to whom Voltaire, in the funeral oration for the officers who died in 1741, addressed these words: ‘You are no more, O sweet hope of my last days; I have always seen you as the most unfortunate of men, and the most tranquil.’

From the depths of my calash, I watched the stars rise.

‘Do not fear, Cynthia; it is only the susurration of the reeds bent by our passage through their motionless forest. I have a knife for the jealous, and courage to defend you. Let not this tomb cause you terror; it is that of a woman once loved as you: Cecilia Metella rests here.

How fine this night in the Roman Campagna! The moon rises behind the Sabine Hills to gaze at the sea; she causes the ash-blue summits of Albano, and the more distant and less deeply engraved outlines of Soracte, to emerge from the diaphanous shadows The long line of ancient aqueducts allows a few drops of moisture to seep over the moss, the columbines, the wallflowers, and joins the mountains to the city walls. Set one above another, the aerial arches cut across the sky, sending the torrent of ages and the courses of rivers along the breeze. Law-giver to the world, Rome, set on the rock of her sepulchre, in her robe of the centuries, projects the broken form of her vast design onto the milky solitude.

Let us sit here: this pine-tree, like a goat-herd of Abruzzo, deploys its umbrella among the ruins. The moon lets fall its light like snow over the Gothic crown of the tower of Metella’s tomb and over the festoons of marble linked to the horns of the bucrania; elegant pomp inviting us to enjoy life as it passes.

Listen! The nymph Egeria sings beside her fount; the nightingale is heard in the vine beside the Scipios’ hypogeia; the languishing breeze of Syria brings us, indolently, the perfume of wild tuberoses. The villa’s palm-tree sways half-drowned in the amethyst and azure of Phoebe’s brightness. But you, pale with the reflected whiteness of Diana, O Cynthia, you are a thousand times more graceful than the palm. The shades of Delia, Lalage, Lydia, Lesbia and Olympia, perched on the broken cornices around you, babble mysterious words. Your glances intersect those of the stars and mingle with their rays.

But there is no reality, Cynthia, in the happiness you enjoy. Those constellations so bright above you are only in harmony with your delight by the illusions of false perspective. Girl of Italy, time flies! Your companions have already passed over this carpet of flowers.

A mist unwinds, ascends and forms a silvery retina for the eye of night; a pelican cries and returns to the shore; a woodcock plunges among the horsetails of diamantine founts; the bell of St Peter’s echoes from the cupola; nocturnal plain-song, voice of the Middle Ages, deepens the melancholy of the isolated monastery of Holy Cross; a monk kneels and recites Lauds, among the calcified pillars of St Paul’s; vestals prostrate themselves on the icy slabs that pave their crypts; the fife-player whistles his midnight plaint before the solitary Madonna, at the sealed door of a catacomb. Hour of sadness, when religion wakes and love sleeps!

Cynthia your voice is weakening: it dies on your lips, that refrain the Neapolitan fisherman brought you in his boat skimming the waves, or the Venetian oarsman in his light gondola. Go to the absences of your repose; I will protect your sleep. The night whose lids cover your eyes subtly disputes with that which Italy, slumbering and perfumed, pours on your brow. When the whinnying of our horses is heard in the Campagna, when the morning star proclaims the dawn, the goat-herd of Frascati will descend, and I will cease to lull you with my song’s murmuring sigh:

“A fascicle of jasmine and narcissi, an alabaster Hebe, not long arisen from the recesses of an excavation, or fallen from the pediment of a temple, lies on that bed of anemones: no Muse, you are wrong. That jasmine, that alabaster Hebe, is a sorceress of Rome, born six months ago, of May and the latter days of spring, to the sound of the lyre, at the break of dawn, in a rose-field of Paestum.

Wind from the orange-groves of Palermo that sighs around Circe’s isle; breeze that passes over Tasso’s tomb, that caresses the nymphs and cupids of the Farnesina; you who play among the Raphael Virgins of the Vatican, among the statues of the Muses, you who dip your wings in the little cascades of Tivoli; genii of the arts who thrive on masterpieces and flutter among memories, come: you alone I will permit to breathe Cynthia’s slumber.

And you, majestic daughters of Pythagoras, you Fates in your linen robes, fatal sisters seated beside the axis of the spheres, turn the thread of Cynthia’s destiny on golden spindles; make them descend from your fingers and rise again to your hands in ineffable harmony; immortal weavers, open the ivory gate to those dreams that rest on a woman’s breast without oppressing it. I will sing of you, O canephorus of the Roman rites, young Charite fed on ambrosia in Venus’ lap, smile sent from the East to glide across my life; forgotten violet in the garden of Horace......”’

...‘Mein Herr? Ten kreutzers for the toll (dix kreutzers bour la parrière)’

A plague on your crutches! I was in another place! I was so in flight! The Muse will not return! That cursed Eger, at which we are arriving, is the cause of my unhappiness.

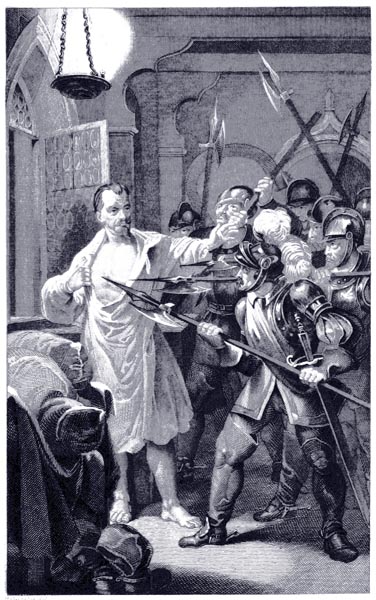

The nights are fatal in Eger. Schiller shows us Wallenstein betrayed by his accomplices, advancing towards the window in a room of the fortress of Eger: ‘The sky is stormy and disturbed,’ he says; ‘the wind toys with the banner on the tower; clouds are flying across the crescent moon that illuminates the night with a flickering and uncertain glow.’

‘Wallenstein Tod’

Der Dreissigjährige Krieg, und die Helden Desselben, Vol 02 - Carl August Mebold (p443, 1840)

The British Library

Wallenstein, at the moment of his assassination, is moved by the death of Max Piccolomini, loved by Thekla: ‘The flower of my life has vanished; he was dear to me like an image of my youth. He changed reality for me to a beautiful dream.’

Wallenstein withdraws to his place of repose: ‘Night advances; there is no sound of movement in the castle: let us go, light the way; take care not to wake me too late; I think I will sleep deeply, after the day’s harsh deeds’

The murderers’ knives snatch Wallenstein from his dreams of ambition, as the voice of the gatekeeper put an end to my dream of love. And Schiller, and Benjamin Constant (who showed fresh talent in imitating the German play), have gone to join Wallenstein, while I recall their triple fame at the gates of Eger.

Book XXXVIII: Chapter 6: Weissenstadt – The lady traveller – Berneck and memories – Bayreuth – Voltaire – Hollfeld – A church – The little basket-carrier – The innkeeper and his servant

1st of June 1833.

BkXXXVIII:Chap6:Sec1

I pass through Eger and on Saturday the 1st of June, at daybreak, I enter Bavaria: a tall red-headed girl, bare-footed and bare-headed, comes to open the gate, as if she were Austria in person. The cold persists; the grass in the ditches is coated with white frost; bedraggled foxes emerge from the oat-fields; outspread jagged grey clouds cut across the sky like eagles’ wings.

I arrived at Weissenstadt at nine in the morning; at the same moment, a kind of hired wagon arrived carrying a young lady with stylish hair; she had the look of what she probably was: a creature destined for pleasure, a brief tale of love, then the hospital and a common grave. Errant joys, may Heaven be not too harsh with your theatricals! There are so many actors worse than you in this world.

Before penetrating the village, I crossed the wastes: the word finds itself at the tip of my pencil; it belongs to our ancient Frankish language: it provides a better description of desolate countryside than the word lande, which means moor.

I still remember the song they sing in the evening crossing the moors:

‘It was the Knight of Landes:

The Knight of Misfortune!

When he was in the ‘lande’,

To hear the bells give tune!’

After Weissenstadt comes Berneck. Leaving Berneck, the road is bordered by poplars, whose winding avenue inspired in me a feeling of pleasure and sadness combined. Searching my memory, I found they resembled the poplars with which the highroad was once lined on entering Villeneuve-Sur-Yonne from Paris. Madame de Beaumont is no more; Monsieur Joubert is no more; the poplars are felled, and, after the fall of the monarchy for the fourth time I am passing the poplars of Berneck on foot: ‘Give me,’ says Saint Augustine, ‘a man who loves, and he will understand what I say.’

The young lady laughs at her errors; she is charming, joyous; you may announce in vain that moment when she will sink as deeply into bitterness; she will shock you with her flightiness, and wing her way towards her pleasures: she is right, so long as she dies along with them.

Here is Bayreuth, a memory of another kind. The town is situated in the midst of a plain with mixed cultivation of grass and cereals: the streets are wide, the houses low, the population light. At the time of Voltaire and Frederick II, the Margravine of Bayreuth was celebrated: her death inspired the poet of Ferney to write the only ode in which he shows any lyric ability:

‘You will sing no longer, lonely Sylvander,

In the Palace of Art where the sound of your word

Dared to speak against prejudice, and sang there,

Allowing Humanity’s rights to be heard.’

The poet would be right in praising himself, if it were not that no one in the world was less solitary than Voltaire-Sylvander. The poet adds, addressing the Margravine:

‘From philosophy’s tranquil heights your pity,

Looked down on the world with eyes serene,

The vanishing phantoms of lifelong reverie,

So many vain ideas, so many ruined dreams.’

‘Wilhelmine, Margravine of Baireuth. From the Original Portrait in Berlin’

Memoirs of Wilhelmine - Margravine Wilhelmine, consort of Friedrich, Margrave of Bayreuth (p9, 1887)

Internet Archive Book Images

From the heights of the Palace, it is easy to look down with eyes serene on the poor devils passing by in the street, but those lines are no less powerful in meaning. Who feels that more than I? I have seen so many phantoms during my lifelong reverie! At this very moment have I not been contemplating the three royal shades in the Palace of Prague and the daughter of Marie-Antoinette in Carlsbad? In 1733, just a century ago, what did people occupy their minds with? Had they the least idea of what would be happening now? When Frederick was married in 1733, under the harsh eye of his father, had he seen, in his almanac, in his copy of ‘Matthieu Laensberg’, Monsieur de Tournon the Treasurer of Bayreuth quitting his treasury for the Prefecture of Rome? In 1933, a traveller passing through Franconia will demand of my shade if I divined the events which he will witness.

While I was lunching, I read the lessons that a German lady, of necessity young and pretty, wrote down from her teacher’s dictation:

‘The one he is happy, is rich. You and me have little money; but we is happy. We are thuss to my mind richer than those who has a ton of gold, and he.’

It is true, mademoiselle, you and me have little money; you are happy, so it appears, and scorn a ton of gold; but if by chance I was not happy, then you might agree that a ton of gold might be very acceptable to me.

Leaving Bayreuth, one ascends. Slender trimmed pine-trees recall the pillars of the Cairo mosque, or the Cathedral of Cordoba, but darkened and truncated, like a landscape reproduced in a camera obscura. The road continues from hill to hill and valley to valley; the hills broad with a tuft of trees on their brows, the valleys narrow and green, but with few streams. At the lowest point of each valley, you find a hamlet marked by the steeple of a little church. All Christian civilization is created in this way: the missionary, who has become a priest, halts; the Barbarians camp around him, like a flock gathering round its shepherd. Once these out of the way places would have made me dream more than one kind of dream; today, I dream of nothing and am happy nowhere.

Baptiste, suffering from an excess of fatigue forced me to stop at Hollfeld. While supper was being prepared, I climbed a rock which overlooks part of the village. On this rock stands a square belfry; martins called as they skimmed the roof and sides of the tower. Since my childhood at Combourg, that scene composed of a few birds and an old tower had not recurred; I felt my heart compress. I descended to the church over ground sloping to the west; it was encircled by its cemetery devoid of recent burials. Only the ancient dead have traced their furrows there; proof that they worked the fields. The setting sun, pale and smothered by a fir grove on the horizon, lit the solitary sanctuary where no one stood but me. When will I lie down in turn? Beings of nothingness and shadow, our powerlessness and our power are deeply characteristic of us: we cannot procure light and life for ourselves at will; but nature, in giving us eyelids and hands, has put night and death at our disposal.

Entering the church whose portal was ajar, I knelt with the intention of saying a Pater and an Ave for the repose of my mother’s soul; immortal duties imposed on Christian souls in their mutual tenderness. There, I thought I heard the door of a confessional open; I imagined that the dead, instead of a priest, would appear at the penitent’s grill. At that very moment the bell-ringer was about to close the church door, I only had time enough to leave.

Returning to the inn, I met a little girl carrying a basket on her back: she had bare feet and legs; her dress was short, her blouse torn; she walked with bowed back and folded arms. We climbed a steep street together; she turned her sunburnt face towards me a little; her pretty tousled hair stuck to her basket behind. Her eyes were black; her mouth was half-open to allow her to breathe: you could see that, beneath her burdened shoulders, her young breast had known nothing but the weight of the orchards’ harvest. She made one wish to speak to her of roses: Pόδα μ’ εϊρηκας (Aristophanes).

I set to drawing up the horoscope of the adolescent fruit-picker: will she grow old at the cider-press, the mother of an obscure but happy family? Will she be led off to the camps by some corporal? Will she fall prey to some Don Juan? The seduced village girl loves her ravisher as well as the astonishment of love; he transports her to a palace of marble on the Straits of Messina, beneath a palm-tree beside a fountain, facing the sea with azure wave, and Etna spouting flame.

I was at this point in my thought, when my companion, turning to the left in a large square, headed towards some isolated habitations. At the moment of vanishing, she stopped; she cast a last glance at the stranger; then, lowering her head to allow herself and her basket to pass beneath a low doorway, she entered a cottage, like a little wild cat slipping into a barn among the sheaves. Let us return to Her Royal Highness Madame la Duchesse de Berry in her prison.

‘I followed her, but grieved also

At having none but her to follow.’

My host at Hollfeld is a singular man; he and his serving-woman are innkeepers as a last resort; they have a horror of travellers. When they see a carriage in the distance, they go and hide while cursing these vagabonds who have nothing to do but travel the highroads, these idlers who disturb an honest tavern-keeper and stop him drinking the wine he is forced to sell them. The old woman perceives that her master will ruin himself; but she awaits a gift of Providence on his behalf; like Sancho she says: ‘Monsieur, accept this fine kingdom of Micomicon that falls from the sky into your hand.’

Once the initial bout of moodiness has passed, the couple, half-tipsy, are fine. The servant speaks a little broken French, stares fiercely at you, and has the air of saying: ‘I have seen better gallants like you in Napoleon’s army!’ She had known the pipe and brandy as well as the glory of the camps; she ogled me malignly and with irritation: how sweet it is to be loved at the very moment when one has lost all expectation of being so! But, Javotte, you arrive too late on the scene of my bruised and shattered hopes, as an old French writer has it; my sentence has been pronounced: ‘Harmonious old man, take your rest,’ Monsieur Lerminier tells me. You see, kindly stranger, I am forbidden from listening to your song:

‘Purveyor to the Regiment,

Javotte is my name.

I sell, I give, and gaily drink

My brandy and my wine.’

Nimble feet, looks that win,

Tin tin, tin tin, tin tin, tin tin

R’lin tin tin.

That is why I refuse to be seduced by you; you are thoughtless; you will betray me. Away with you then, Javotte of Bavaria, like your predecessor Madame Isabeau.

Book XXXVIII: Chapter 7: Bamberg – A hunchback – Wurtzburg – Its Canons – A drunken man – The swallow

2nd of June 1833.

BkXXXVIII:Chap7:Sec1

Leaving Hollfeld, I passed through Bamberg at night. Everyone was asleep; I only saw one little light whose feeble gleam shone from the depths of a room dimmed by the window. What was awake there: pleasure or pain; love or death?

At Bamberg in 1815, Berthier Prince of Neuchâtel fell from a balcony into the street: his master was to fall from a greater height.

Sunday, the 2nd of June.

At Dettelbach, the vineyards reappear. Four kinds of vegetation mark the boundaries of four habitats and four climates; silver birch, vines, olive-trees and palm-trees, progressing ever sunwards.

Beyond Dettelbach, two relay posts before Würzburg a female hunchback seated herself at the back of my carriage; she was the Girl from Andros of Terence: Inopia.egregia forma, aetate integra: Poor.of surpassing beauty, in the flower of youth. The coachman wanted her to descend; I opposed this for two reasons: firstly because I feared the witch might cast a spell on me: secondly because having read in a biography of me that I was a hunchback myself, all female hunchbacks are my sisters. Who can re-assure you that you are not a hunchback? Who will refrain from ever telling you that you are one? If you look at yourself in a mirror, you see nothing; does one ever see what one is? You will find your waist measurement suits you marvellously. All hunchbacks are proud and happy; popular songs swear to the advantages of a hunched back. At the entrance to a track, my lady hunchback, adjusting herself, set foot to earth majestically: charged with her burden, like all mortals, Serpentine pushed her way into a cornfield, and disappeared among ears of wheat taller than she.

At noon on the 2nd of June, I reached the summit of a hill from which Würzburg was revealed. The castle is on a height, the town below, with its palace, steeples and turrets. The palace, though solid, would be fine even in Florence; in case of rain, the Prince could shelter all his subjects in his château, without having to use his own apartments.

‘A View of Würzburg at the Time of the Thirty Years' War, 1631’

Geschichte der Kön. Schwedischen und Herzogl. Sachsen-Weimarischen Zwischenregierung im Eroberten Fürstbisthume Würzburg - Carl Gottfried Scharold (p16, 1844)

The British Library

The Bishop of Würzburg was once sovereign over the nominations for canons of the chapter. After his election, he passed, nude to the waist, between his confreres ranged in two files; they whipped him. One would expect that Princes, shocked by this method of consecrating the royal back, would refuse to join the ranks. Today they would not succeed: there is no descendant of Charlemagne who would accept being whipped for three days in order to obtain the crown of Yvetot.

I have met the Emperor of Austria’ brother, the Duke of Würzburg; he sang very agreeably in Francis I’s gallery at Fontainebleau, at the Empress Josephine’s concerts.

Schwartz was detained for two hours at the passport bureau. Left, with my horseless vehicle, in front of a church, I entered: I prayed with the Christian congregation, who represent the old society in the new. A procession left to make a circuit of the church; if only I were a monk in the ruins of Rome! The age to which I belong will end with me.

When the first seeds of religion germinated in my soul, I bloomed, as virgin earth, freed from its brambles, bears its first crops. A cold and arid North Wind rises and the ground is parched. The sky takes pity on it; it grants its cool dew; then the North Wind blows again. That alternation of doubt and faith has long made my life a mixture of despair and ineffable joy. My good and saintly mother, pray to Jesus Christ for me: more than other men your son needs redemption.

I left Würzburg at four and took the road to Mannheim. Entering the Duchy of Baden, through a village which was in the midst of celebrations, a drunken man grasped my hand shouting: ‘Long live, the Emperor!’ Everything that has happened since the Fall of Napoleon has not occurred as far as Germany is concerned. Those men, who rose to snatch their national independence courtesy of Bonaparte’s ambition, dream only of him, he has so seized the imagination of nations, from the Bedouin in their tents to the Teutons in their huts.

The nearer I came to France, the noisier the children in the villages became, the faster the coachmen drove: life was reborn.

At Bischofsheim, where I dined, a pretty curiosity appeared at my grand repast: a swallow, truly Procne with her reddened throat, she came to perch at my open window, on the iron bracket that supported the sign of the Golden Sun; then she uttered the sweetest song in the world, regarding me with a look of recognition and without showing the least fear. I am never sorry to be woken by the daughter of Pandion; I have never called her a babbler as Anacreon does; I have always, on the contrary, welcomed her return with the children’s song from the Isle of Rhodes: ‘She comes, she comes, the swallow comes, bringing fine weather and lovely days! Open your doors, never scorn her, the swallow.’

‘François,’ said my table-guest in Bischofscheim, ‘my great-great-grandmother lived at Combourg, beneath the eaves of the tower roof; you kept her company every autumn, in the reeds by the lake, when you dreamed at evening with your sylph. She flew around your native cliffs the very day you embarked for America and sometimes followed your sail. My grand-mother nested above Charlotte’s window; eight years later she arrived with you in Jaffa; you commented on her in your Itinerary. My mother, singing to the dawn, once fell down the chimney in your room at the Foreign Office; you opened the window for her. My mother had several children; I who am speaking to you, am from her last brood; I have already met you on the ancient Tivoli road in the Roman countryside; do you remember? My feathers were so dark and lustrous! You are looking at me sadly. Do you want us to fly away together?’

– ‘Alas, dear swallow, who could know my story better than you, you are extremely kind; but I am a poor bird in moult, and my feathers will not renew; so I cannot fly with you. Too weighed down by sorrows and years, it would be impossible for you to carry me. And then, where would we go? Spring and fair climes are no longer my season. Love and the air are yours, earth and loneliness mine. You are going; may the dew refresh your wings! May a hospitable spar offer itself to your weary flight, as you cross the Ionian Sea! May a serene October save you from disaster! Greet the olive-trees of Athens and the palm-trees of Rosetta for me. If I am no more when the flowers recall you, I invite you to my funeral feast: come at sunset to snatch flies from the grass by my tomb; like you, I have loved liberty, and I have lived awhile.’

Book XXXVIII: Chapter 8: The inn at Wiesenbach – A German and his wife – My old age – Heidelberg – Pilgrims – Ruins - Mannheim

3rd and 4th of June 1833.

BkXXXVIII:Chap8:Sec1

I myself was on my way overland a little after the swallow had appeared. The night was cloudy; the moon swam, dim and waning, among the clouds; my eyes, half-shut, closed while gazing at her; I felt as though I was expiring in the mysterious light which illuminates the shades: ‘I experienced a quiet despondency, precursor of the last repose.’ (Manzoni)

I stopped at Wiesenbach: a solitary inn, in a narrow cultivated valley between two wooded hills. A German from Brunswick, a traveller like myself, hearing my name pronounced, approached me. He grasped my hand, and spoke to me about my works; his wife, he said, learnt to read French by studying Le Génie du Christianisme. He commented endlessly on my astonishing youthfulness. ‘But,’ he added, ‘my judgement is at fault; from your recent works I ought to have believed you to be as young as you appear there.’

My life has been involved with so many events that I possess, in my readers’ minds, the antiquity of those same events. I often talk about my grey hair: a calculated move on the part of my self-esteem, so that on seeing me people cry: ‘Oh, he is not so very old!’ People are comfortable with their white hair: they can boast of it; to glorify oneself for having black hair would be in very bad taste: a great subject for a triumph to be as your mother made you! But to have the look of the age, misfortune and wisdom you have acquired, that is fine! My little ruse sometimes succeeded. Lately a priest expressed the desire to meet me; he remained silent on seeing me; at last recovering his speech, he cried: ‘Oh, my dear sir, you will battle for the faith for ages yet!’

One day, passing through Lyons, a lady wrote to me; she begged me to grant a place in my carriage to her daughter and escort her to Paris. The proposition seemed unusual to me; but finally, having verified the signature, the unknown turned out to be a highly respectable lady; I replied politely. The mother presented herself with her daughter, a divinity of sixteen. The mother had no sooner set eyes on me than she blushed scarlet; her confidence fled: ‘Pardon me, Monsieur, she said to me stammering: I am no less filled with esteem. But you understand the situation. I am at fault. I am so surprised.’ I insisted on gazing at my future companion, who seemed to be amused by the conversation; I protested profusely that I would take the greatest care imaginable of that lovely young person; the mother vanished in a wave of excuses and curtseys. The two ladies withdrew. I was proud to have given them so much to fear. For several hours, I thought myself rejuvenated by Aurora. The lady had imagined that the author of Le Génie du Christianisme, was some old Abbé Chateaubriand, an aged gentleman tall and dry, incessantly taking snuff from an enormous tin snuff-box, who could certainly be entrusted with escorting an innocent schoolgirl to the convent of Sacré-Coeur.

At Vienna, ten or fifteen years ago, they said that I lived quite alone in a certain valley called the Vallé-aux-Loups. My house was built on an island: when anyone wished to see me, they had to sound a horn from the opposite bank of the river (the river at Châtenay!) Then, I inspected them through a hole: if the company pleased me (which was hardly ever the case), I came to collect them myself in a little boat; if not I did not. In the evenings, I beached my canoe and no one could reach my island. Indeed, I should have lived like that; that story from Vienna has always delighted me: Prince von Metternich certainly did not invent it; he is too much my friend to have done so.

I have no idea what the German traveller might have said about me to his wife, or whether he would have hastened to disabuse her of my dilapidation. I fear the disadvantages of possessing dark hair and white hair, and of being neither young nor a sage. Moreover, I was scarcely in the mood for coquetry in Wiesenbach; a gloomy northerly moaned beneath the doors and through the corridors of the hostelry: when the wind blows, I am no more amorous than it.

From Wiesenbach to Heidelberg, you follow the course of the Neckar, bordered by steep hills, which bear forest on shoals of sand and red sulphate. What rivers I have seen! I encountered pilgrims from Waldthurn: they formed parallel lines on both sides of the main road: vehicles passed through their midst. The women walked barefoot, rosary in hand, a bundle of linen on their heads; the men bare-headed, also rosary in hand. It was raining; in several places watery clouds crawled across the hill slopes. Boatloads of wood floated downriver, others ascended, under tow or sail. In gaps among the hills stood hamlets surrounded by fields, amid rich vegetable gardens ornamented with Bengal roses and various flowering shrubs. Pilgrims, pray for my little King: he is exiled, he is innocent; he begins his pilgrimage as you complete yours, and I end mine. If he is not to reign, a little glory will always be due to me for having roped my lifeboat to the ruins of so great a fate. God alone grants fair winds and a path to harbour.

Approaching Heidelberg, the bed of the Neckar, scattered with rocks, widens. You see the quays of the town and the town itself, of fine appearance. The background to the picture terminates in high ground on the horizon: it seems to form a barrier to the river.

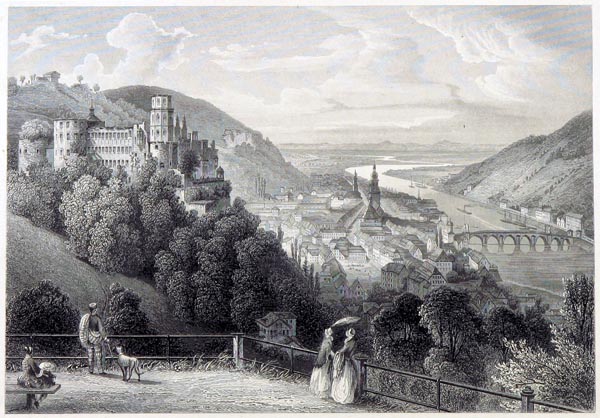

‘Heidelberg’

Das Grossherzogthum Baden in Malerischen Original-Ansichten - Eugen Huhn (p228, 1860)

The British Library

A triumphal arch of red stone announces the entrance to Heidelberg. On the left, on a hill, are the remains of a medieval castle. Apart from their picturesque effect and a few local traditions, the Gothic ruins only interest those who study them. Is a Frenchman to be hampered by those Palatine Lords and Princesses, coarse and pale as they were, with their blue eyes? One would exchange them all for Saint Geneviève de Brabant. Those modern fragments have nothing in common with the people today, except a Christian appearance and a feudal character.

It is otherwise (without counting the sunlight) with the monuments of Greece and Italy; they belong to all nations: history begins with them; their inscriptions are written in languages known to all civilised men. Even the ruins of a renewed Italy are of general interest, since they are imprinted with the seal of art, and the arts of society belong to the public domain. A faded fresco by Dominico or Titian, a crumbling palace by Michelangelo or Palladio, makes genius mourn in any century.

In Heidelberg they show you an enormous barrel, a Colosseum for ruining drunkards; at least no Christian has lost his life in this amphitheatre of the Vespasians of the Rhine; his reason, yes: but that is no great loss.

On exit from Heidelberg, the hills open out to right and left of the Neckar, and you enter a plain. A tortuous roadway, elevated a few feet above the level of the wheat fields, runs between two rows of cherry-trees ill-treated by the wind and walnut trees often abused by the passer-by.

Entering Mannheim you pass through hop fields: their long dry poles were as yet only adorned to a third of their height with the climbing plants; Julian the Apostate made a pretty epigram against beer; the Abbé de La Bletterie has imitated it with a degree of elegance:

‘You are naught but a false Bacchus.

I bear witness to the true.

................

Let the Gaul, with eternal thirst, I say

In default of the grape employ the ears

Of Ceres whose son he cheers:

Long live the son of Semele!’

Orchards, with walks shaded with willows on every side, form the verdant suburbs of Mannheim. The houses of the town often only possess one storey above the ground floor. The principal street is wide and planted with trees in the middle: yet it is a city out of favour. I do not like false gold: and I have never wished for the imitation worked in Mannheim; but I certainly possess gold of Toulouse, judging by the disasters of my life; who more than I, however, has respected the temple of Apollo?

Book XXXVIII: Chapter 9: The Rhine – The Palatinate – Mont-Tonnerre – Aristocractic Armies, Plebeian Armies – Monastery and castle – A solitary inn – Kaiserslautern – Sleep – Birds - Saarbruck

3rd and 4th of June 1833.

BkXXXVIII:Chap9:Sec1

I crossed the Rhine at two in the afternoon; at the instant I passed, a steamboat was ascending the river. What would Caesar have thought if he had encountered such a vessel when building his bridge?

‘Bridge Over the Rhine (Museum of St. Germain)’

History of Rome and of the Roman people, from its Origin to the Invasion of the Barbarians - Victor Duruy (p361, 1882)

Internet Archive Book Images

On the other side of the Rhine, facing Mannheim, one is again in Bavaria, due to a series of odious sequestrations and the machinations of the Treaties of Paris, Vienna and Aix-la-Chapelle. Everyone has played a part in these hatchet-jobs, without regard to logic, humanity, or justice and without concern for the section of the population that fell into the royal maw.

In travelling through the Palatinate this side of the Rhine, I reflected that the area was formerly a department of France (Mont-Tonnerre), that Gaul in white was circled by the Rhine, Germany’s blue sash. Napoleon, and the Republic before him, realised the dream of several of our kings and especially Louis XIV. As long as we fail to occupy our natural frontiers there will be war in Europe, because self-preservation forces France to seize borders essential to her national independence. Here, we have planted trophies to reclaim at a future time and place.

The plain between the Rhine and the Tonnerre Mountains (Donnersberg) is melancholy; the soil and the men seem to say that their fate is not settled, that they belong to no nation; they appear to be waiting on a new armed invasion, like a new inundation of the river. The Germans of Tacitus laid large areas on their frontiers waste, between themselves and their enemies, and left them empty. Ill luck to those populations near borders who cultivate battlefields where nations are to meet!

Further on I saw a sad sight: a wood of six-foot pine saplings cut and tied for faggots, a forest cut unripe. I have spoken about the cemetery at Lucerne: there the children’s sepulchres are squeezed together, apart. I have never felt more deeply the desire to end my life, to die beneath the guardianship of a friendly hand applied to my heart, as a test, when they say: ‘It no longer beats.’ At the edge of my grave I would like to be able to look back with satisfaction on my numerous years, as a Pontiff arriving at the sanctuary blesses the long train of priests who will serve as his cortege.

Louvois set the Palatinate alight; alas the hand that held the torch was that of Turenne’s shade. The Revolution ravaged the same area, witness and victim, time and again, to our aristocratic and plebeian victories. It is enough to name the generals to identify the change of century: on the one hand, Condé, Turenne, Créquy, Luxembourg, La Force, Villars; on the other Kellerman, Hoche, Pichegru, Moreau. Let us not disown any of our triumphs; military glory above all has not gone only to France’s enemies, and has not been only of one class: on the battlefield honour and danger level rank. Our forefathers called the blood issuing from a wound that was not mortal sang volage: idle blood: a phrase characteristic of that disdain for death natural to Frenchman in all centuries. Institutions have no effect on this national spirit. The soldiers who said, after Turenne’s death: ‘Let Piebald runfree: we will camp where she halts’, would have understood the worth of Napoleon’s grenadiers perfectly.

On the heights of Durkheim, the premier rampart of the Gauls on this bank of the Rhine, you will find the sites of camps and military positions now devoid of soldiers: Burgundians, Franks, Goths, Huns, Swabians, waves of the Barbarian deluge, assailed these heights in turn.

Not far from Durkheim are the ruins of an abbey. The monks enclosed in that retreat had a fine view of the armies circling at their feet; they gave good hospitality to the soldiers; there, some crusader ended his life, changing his helm for a hood; there lived passions that summoned silence and repose before the last repose and the final silence. Did they find what they sought? These ruins will not tell.

After the debris of the sanctuary of peace comes the litter of a den of war, the razed bastions, mantlets, curtain-walls, and emplacements of a fortress. The ramparts are crumbling like the cloisters. The castle was sited in a vulnerable pass as a defence against the enemy: it has not prevented time and death from passing by.

From Durkheim to Frankenstein, the road threads its way through a valley so narrow that it barely allows access for a vehicle; the trees descending from the opposite embankments meet and embrace in the ravine. Between Messenia and Arcadia, I followed similar valleys, to the better track nearby: Pan knew nothing of bridges and highways.

Flowering broom and a jay brought back memories of Brittany; I remember the pleasure I derived from that bird’s cry in the mountains of Judea. My memory is a panorama; there, on the same screen the most diverse sites and skies come to paint themselves with their burning suns or their misted horizons.

The inn at Frankenstein is set in a mountain meadow, watered by a brook. The post-master speaks French; his young sister, or wife, or daughter is charming. He complains about being Bavarian; he busies himself with exploiting the forests; he reminded me of an American timber-man.

At Kaiserslautern, which I entered at night as I had Bamberg, I traversed a region of dreams: what did all those sleeping inhabitants see in their sleep? If I had the time, I would compose the history of their dreams; nothing would have recalled me to earth if two quails had not called from one cage to another. In the fields in Germany, between Prague and Mannheim, one only meets with crows, larks and sparrows; but the towns are full of nightingales, warblers, thrushes and quails; plaintive prisoners of both sexes whom you greet at the bars of their gaol as you pass. The windows are embellished with carnations, mignonettes, roses and jasmine. The Northern races have the tastes of a different clime; they love the arts and music: the Germans went to seek the vine in Italy; their descendants willingly repeat the invasion to win from the same places birds and flowers.

The coachman changing his jacket alerted me, on Tuesday the 4th of June, at Saarbruck, that I was entering Prussia. Beneath the window of my inn I saw a squadron of hussars file by; they had an animated air: I felt likewise; I would have cheerfully vied at giving those gentlemen a beating, even though a lively feeling of respect attracted me to the Prussian royal family, even though the tempers of the Prussians in Paris had only been reprisals for Napoleon’s brutalities in Berlin; but if historians have time to undertake such cool judgements, deducing consequences from principles, the man who is a witness to current events is dragged along by those events, without seeking in the past the causes from which they emerge and which excuse them. She has done me plenty of harm, my country; but how joyfully I would give my blood for her! Oh, those firm minds, those consummate politicians, above all those fine Frenchmen, who negotiated the treaties of 1815!

A few more hours, and my native land will once more quiver under my feet. What shall I find? For three weeks I have known nothing of my friends’ words or actions. Three weeks! A long stretch of time for a man, whom an instant can snatch away, for an empire which three days can overturn! And my prisoner of Blaye, what has become of her? Shall I be able to hand her the message she awaits? If the person of any ambassador ought to be sacred, it should be mine; my diplomatic career was rendered holy in proximity to the Head of the Church; it completed its sanctification in proximity to that of an unfortunate monarch: I have negotiated a new family pact between the descendants of the Béarnais; I have fetched and carried messages between prison and exile, exile and prison.

Book XXXVIII: Chapter 10: Forbach to Paris

4th and 5th of June 1833.

BkXXXVIII:Chap10:Sec1

Crossing the border which separates the territory of Saarbruck from that of Forbach, France did not show herself to me at her most brilliant: first an amputee, then another man crawling along on hands and knees, dragging his legs after him like two twisted tails or dead snakes; then in a cart appeared two old women, blackened, wrinkled, the vanguard of French womanhood. There was something to turn the Prussian army.

But afterwards I encountered a fine young foot-soldier with a young girl; the soldier was pushing the girls’ wheelbarrow in front of him, while she carried the trooper’s pipe and sabre. Further on another young girl held the handle of a plough, while an old ploughman prodded the oxen; further on an old man begging for a blind child; further on a wayside cross. In a hamlet, a dozen children’s heads, at the window of an unfinished house, resembled a group of angels in glory. Behold a little boy of five or six, sitting on the threshold of a cottage; bare-headed, blond-haired, with a dirty visage, pulling a face because of the cold breeze; his white shoulders emerging from a torn canvas smock, his arms crossed over his legs hunched towards his chest, watching everything going on around with birdlike curiosity; Raphael would have sketched him, I wanted to take him to his mother.

Entering Forbach, a troop of trained dogs appeared: the two largest were hitched to the costume-wagon; five or six more with varying tails, muzzles, waists and coats followed the baggage, each with a piece of bread in its mouth. Two grave looking trainers, one carrying a big drum, the other carrying nothing at all, led the band. Come, my friends, make a tour of the earth with me, so as to learn how to comprehend the nations. You hold as great a place in the world as I; you like the dogs of my species well enough. Present your paw to Diana, Mirza and Pax, hat over your ear, sword at your side, tail in the air between the wings of your coat; dance for a bone or a blow from a foot as we men do; but don’t fall flat when you leap for the King!

Reader, suffer these arabesques; the hand that wrote them will do you no other ill; it is withered. Remember, as you read them, that they are only the capricious scrawls traced by a painter on the arch of his tomb.

At the customs post, an old clerk made a semblance of inspecting my calash. I had a hundred sous coin ready; he saw it in my hand but dared not take it in case his superiors were watching. He took off his helmet under the pretext of rummaging more freely, placing it on the cushion in front of me, saying, in a low voice: ‘In my helmet, please.’ Oh! The grand phrase! It contains the whole history of the human race; how often liberty, loyalty, devotion, friendship, love have said: ‘In my helmet, please!’ I will give that phrase to Béranger as a refrain for one of his songs.

I was struck, on entering Metz, by something I had not noticed in 1821; modern fortifications enveloping the Gothic fortifications: Guise and Vauban are two names rightly associated with one another.

Our years and our memories are laid down in regular and parallel layers, at different depths of our existence, deposited by the tides of time that pass over us in succession. It was from Metz, in 1792, that the column emerged which engaged our little corps of émigrés below Thionville. I am entering it from a pilgrimage to the retreat of my banished Prince whom I served in his first exile. I gave a few drops of my blood for him then, I have come from weeping beside him now; at my age one scarcely has any tears left.

In 1821 Monsieur de Tocqueville, my brother’s brother-in-law, was Prefect of the Moselle. The saplings, thin as canes that Monsieur de Tocqueville planted in 1820 at the gates of Metz, now give shade. Behold a scale to measure our days; but man is not like the vine, he does not improve by adding the leaves of his years. The ancients infused Falernian wine with rose-petals; when one decanted an amphora from a vintage Consulate, it perfumed the feast. The clearest knowledge would be so infused with its old age that no one would be tempted to get drunk on it.

I had not been in the inn at Metz a quarter of an hour when Baptiste appeared greatly agitated: with a deal of mystery he took a piece of white paper from his pocket in which a seal was wrapped; Monsieur le Duc de Bordeaux and Mademoiselle had entrusted this seal to him, telling him only to hand it to me on French soil. They had been anxious the whole night before my departure, fearing that the jeweller would not have time to complete the work.

The seal had three facets: on one an anchor was engraved: on the second the two words that Henri had said to me during our first interview: ‘Yes, always!’ on the third the date of my arrival in Prague. The brother and sister begged me to employ the seal for love of them. The mystery of this gift, the order from the two exiled children only to reveal this witness to their memory to me on the soil of France, brought tears to my eyes. The seal will never leave me; I will carry it for love of Louise and Henri.