François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XL: Ferrara, Padua, The Duchesse de Berry 1833

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XL: Chapter 1: Madame de Bauffremont’s arrival in Venice – Cataio – The Duke of Modena – The Tomb of Petrarch at Arqua – A Land of Poets

- Book XL: Chapter 2: Tasso

- Book XL: Chapter 3: The arrival of Madame la Duchesse de Berry

- Book XL: Chapter 4: Mademoiselle Lebeschu – Count Lucchesi-Palli – Discussion – Dinner – Bugeaud the gaoler – Madame de Saint-Priest, Monsieur de Saint-Priest – Madame de Podenas – Our Troop – My refusal to go to Prague – I yield to a word

- Book XL: Chapter 5: Padua – Tombs – Zanze’s manuscript

- Book XL: Chapter 6: Unexpected news – The Governor of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia

- Book XL: Chapter 7: A letter from Madame to Charles X and Henri V – Monsieur de Montbel – My note to the Governor – I leave for Prague

Book XL: Chapter 1: Madame de Bauffremont’s arrival in Venice – Cataio – The Duke of Modena – The Tomb of Petrarch at Arqua – A Land of Poets

Venice to Ferrara, 17th to the 18th of September 1833.

BkXL:Chap1:Sec1

There was an immense gulf between this reverie and the reality to which I returned on presenting myself at the Princesse de Bauffremont’s hotel; I was forced to leap from 1806, the memories of which had just occupied me, to 1833, where in fact I found myself to be: Marco Polo descended on Venice from China, after just such an absence of twenty-seven years.

Madame de Bauffremont bore in her face and her manners the unmistakable mark of a Montmorency: she might well, like that Charlotte, mother of the Great Condé and the Duchesse de Longueville, have been Henri IV’s lover. The Princess told me that Madame la Duchesse de Berry had written a letter to me from Pisa which I had not received: Her Royal Highness had arrived in Ferrara where she expected me.

It cost me something to abandon my retreat; I needed a week or so more for my sightseeing; above all I regretted not seeing the end of the Zanze adventure, but my time belonged to Henri V’s mother, and whenever I travel something always occurs that sends me off track.

I left my luggage at the Hôtel de l’Europe on departure, counting on returning with Madame.

I found my calash again at Fusina: they retrieved it from an old shed, like a jewel from the Royal wardrobe. I left the shore that may take its name from the King of the Ocean’s trident: Fuscina.

Returning to Padua, I told the coachman: ‘The Ferrara road.’ The route is delightful as far as Monselice: an extremely elegant hill, orchards of fig-trees, mulberries and willows festooned with vines, pleasant meadows, and ruined castles. I passed Cataio, adorned with soldiers: the Abbé Lenglet, otherwise very erudite, mistook this name for Cathay. This Cataio belongs not to Angelica, but to the Duke of Modena. I found myself face to face with His Highness. He had deigned to take a walk along the highroad. The Duke is an offshoot of the race of Princes invented by Machiavelli; he was proud enough not to recognize Louis-Philippe.

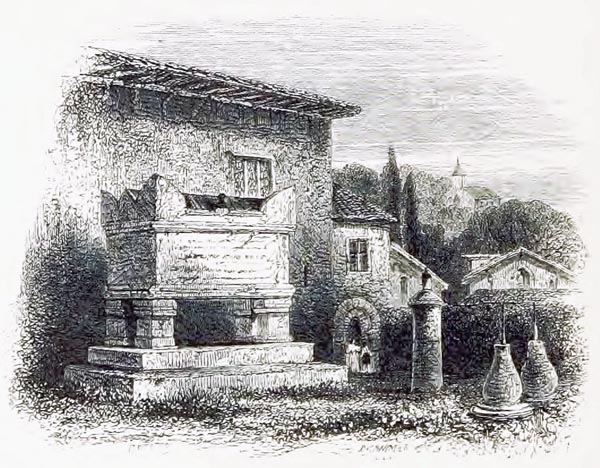

The village of Arqua displays the tomb of Petrarch, sung along with its site by Lord Byron:

‘Che fai, che pensi? che pur dietro guardi

Nel tempo, che tornar non pote amai,

Anima sconsalata?’

Disconsolate spirit, what do you think, or do?

Why do you look behind, at days

that cannot come again?’

‘Petrarch's Tomb’

Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, a Romaunt. Single Works. Childe Harold's Pilgrimage. Cantos I-IV - Baron George Gordon Byron (p230, 1869)

The British Library

All this country, to a distance of sixty miles around, is the native soil of writers and poets: Livy, Virgil, Catullus, Ariosto, Guarini, the Strozzi, the three Bentivoglios, Bembo, Bartoli, Boiardo, Pindemonte, Varano, Monti, and a crowd of other famous men, were engendered by this land of the Muses. Even Tasso was of Bergamese origin. I have not met the most recent of these poets except for one of the two Pindemontes. I did not know Cesarotti or Monti, I would have been happy to have met Pellico and Manzoni, the dying rays of Italian glory. The Euganean Mountains, which I travelled through, were gilded by the sunset with a pleasant variety of forms and great purity of line: one of those mountains resembled the main pyramid at Sakhara, when outlined against the Libyan horizon by the setting sun.

I continued my journey by night through Rovigo; a blanket of fog covered the earth. I only saw the River Po at the Lagoscuro crossing. The carriage stopped; the coachman summoned the ferry with his trumpet. The silence was complete; except for the barking of a dog on the opposite bank of the river, and the distant cascade of a triple echo responding to his call; a foretaste of Tasso’s Elysian empire which we were about to enter.

A splashing sound in the water, through the fog and the shadows, announced the ferry; it slid along the rope tied between anchored boats. Between four and five in the morning of the 18th I arrived in Ferrara: I stopped at the Three Crowns; Madame was expected there.

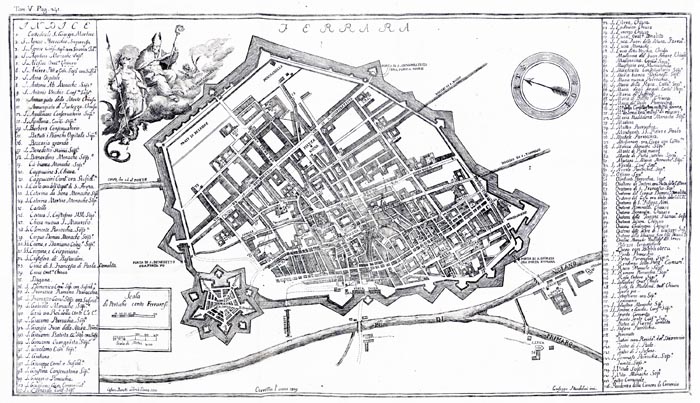

‘Ferrara’

Memorie per la Storia di Ferrara Raccolte da A. F., con Giunte e Note del Con. Avv. C. Laderchi. Seconda Edizione, Vol 02 - Antonio Frizzi (p792, 1847)

The British Library

Wednesday the 18th.

Her Royal Highness not having arrived, I visited the Church of San Paolo; I only saw the tombs; and never a soul, save for those of the dead and mine which was barely alive: at the end of the choir hung a painting by Guercino.

The cathedral is deceptive: you see a front and two sides incrusted with bas-reliefs of sacred and profane subjects. On this exterior there is further ornamentation, more usually placed inside Gothic buildings, such as rudentures, Arabic sculptured corbels, soffits with aureoles, and galleries of little columns with ogives, and trefoils, built into the thickness of the walls. You enter, and you stand amazed on finding a different church with hemispherical vaults and massive pillars. Something like this disparity exists in France, both physically and morally: inside our old chateaux they indulge in modern offices, masses of rats’ nests, alcoves and wardrobes. Penetrate the souls of a good number of those men with historic names and coats of arms, and what do you find there: the inclinations of the ante-chamber.

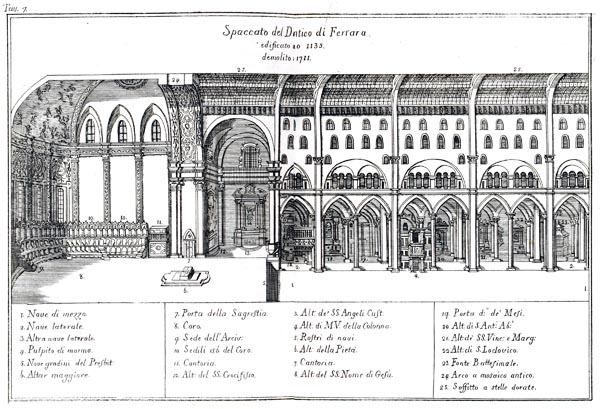

‘Ferrara Cathedral’

Memorie per la Storia di Ferrara Raccolte da A. F., con Giunte e Note del Con. Avv. C. Laderchi. Seconda Edizione, Vol 02 - Antonio Frizzi (p650/651, 1847)

The British Library

I was quite embarrassed by this aspect of the cathedral: it seemed to have been turned inside-out like a robe: a bourgeois woman of the age of Louis XV disguised as a twelfth century lady of the manor.

Ferrara, once so lively with its women, pleasures and poets, is almost uninhabited: its wide streets are deserted, and the sheep can graze there. The decaying houses are not rescued as they are in Venice, by the architecture, the vessels, the sea and the natural gaiety of the place. At the gateway to so wretched a Romagna, Ferrara, under the yoke of her Austrian garrison, has the appearance of an oppressed person: she seems to bear Tasso’s everlasting grief; about to fall, she stoops like an old woman. The sole monument to the present, a criminal court, half rises from the ground, with some unfinished prison blocks. Whom will they put in these fresh dungeons: Young Italy? The new gaols, surmounted by cranes and edged with scaffolding, like the palace of Dido’s city, neighbour the ancient dungeon of the poet of Jerusalem Delivered.

Book XL: Chapter 2: Tasso

Ferrara, the 18th of September 1833.

BkXL:Chap2:Sec1

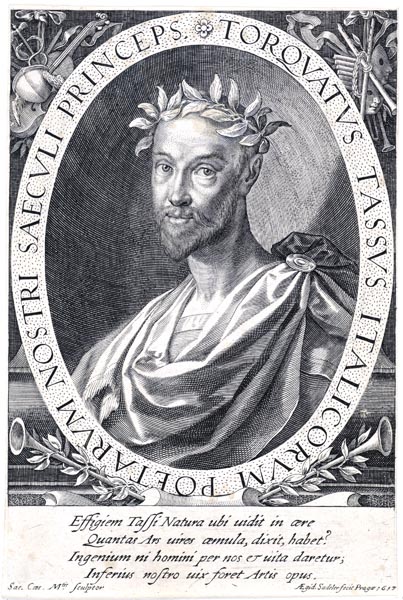

If there is one life that must make us despair of happiness where men of genius are concerned, it is that of Tasso. The lovely sky his eyes saw when first they opened to the light of day was a deceptive sky.

‘My troubles,’ he says, ‘began with my life. Cruel fortune snatched me from my mother’s arms. I remember her kisses mingled with tears, her prayers that the winds carried away. I could no longer press my face against hers. With tottering steps like Ascanius or the young Camilla, I followed my proscribed father’s wanderings. I grew up in poverty and exile.’

Torquato Tasso lost Bernardo Tasso at Ostiglia. Torquato eclipsed Bernardo as a poet; he gave him immortality as a father.

‘Portrait of Torquato Tasso’

Aegidius Sadeler, 1617

The Rijksmuseum

Emerging from obscurity with the publication of Rinaldo, Tasso was summoned to Ferrara. There he debuted in the midst of the celebrations of Alfonso II’s marriage with the Arch-Duchess Barbara, and there he met Leonora, Alfonso’s sister: love and misfortune contrived to endow his genius with all its beauty. ‘I saw,’ says the poet, describing in his Aminta the noble court of Ferrara, ‘I saw goddesses and charming nymphs, free of veils or mists: I felt myself inspired by a new power, by a new divinity, and I sang of war and heroes.!’

Tasso read the stanzas of his Gerusalemme to Alfonso’s two sisters, Lucrezia and Leonora, as he composed them. He was sent to Cardinal Ippolito d’Este, who was established at the court of France: he pawned his clothes and furniture to make the journey, while the Cardinal, whom he honoured by his presence, made the sumptuous gift of a hundred Barbary steeds with their superbly dressed Arab riders, to Charles IX. Despatched at first to the stables, Tasso was then presented to the poet-king, a friend of Ronsard. In a letter which we have, he judges the French harshly. He composed a few lines of his Gerusalemme in an Abbey in France which Cardinal Ippolito had established; it was at Châalis, near Ermenonville, that Jean-Jacques Rousseau dreamed and died: Dante also may have visited Paris.

‘Tasso and the two Eleanors’

Great Men and Famous Women: a Series of Pen and Pencil Sketches of the Lives of More Than 200 of the Most Prominent Personages in History, Vol 07 - Charles Francis Horne (p66, 1894)

Internet Archive Book Images

Tasso returned to Italy in 1571, and so failed to witness the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre. He went straight to Rome and from there returned to Ferrara. His Aminta was given with great success. While rivalling Ariosto, the creator of Rinaldo admired the creator of Orlando to such an extent that he refused the homage to him of that poet’s nephew: ‘The laurels you offer me,’ he wrote, ‘have been placed on the head of him whose blood you share, through the judgement of scholars, gentlemen, and myself. Prostrating myself before his image, I grant him the noblest titles that affection and respect can dictate to me. I will proclaim him aloud as my father, my lord and my master.’

This modesty, though unknown in our age, did not forestall jealousy. Torquato watched the celebrations given by Venice to Henri III on his return from Poland, while a manuscript of the Gerusalemme was secretly printed: detailed criticisms by friends whose views Tasso consulted alarmed him. Perhaps he revealed himself as over-sensitive; but perhaps he had built hopes of success in love on hopes of glory. He believed himself surrounded by trickery and treason; he was obliged to defend his life. His stay at Belriguardo, where Goethe evokes his shade, did little to calm him: ‘Like the nightingale,’ (says the great German poet in a speech of the great Italian poet) ‘he exhaled from his love-sick breast a sorrowful harmony: his delightful singing, his sacred melancholy, captivated the ear and the heart.’

‘What has a greater right to cross the centuries mysteriously than the secret of a noble love, confided to the secrecy of a sublime poem? ...’

‘How delightful it is’ (Goethe again interprets Leonora’s feelings), ‘how delightful it is to see oneself reflected in this man’s fine genius, to have him beside one in the splendours of this life, to advance with him swiftly towards the future! Time cannot hurt you now, Leonora: living in the land of poetry, you will be forever young, forever happy, as the years carry you along in their course.’

The singer of Erminia conjures Leonora (again in the German poet’s lines) to let him stay in one of her most solitary villas: ‘Suffer me,’ he tells her, ‘to be your slave. How I shall nurse your trees! With what care, in autumn, will I cover the tender saplings of your lemon grove! I will raise beautiful beds of flowers beneath the glass.’

The tale of Tasso’s love was lost, Goethe recreated it.

BkXL:Chap2:Sec2

The sorrows of the Muses and religious scruples began to disturb Tasso’s reason. He was made to endure a short period of detention. He escaped half-naked, wandered in the mountains, borrowed a shepherd’s rags and, disguised as one, arrived at his sister Cornelia’s house. His sister’s embrace, and the attractions of his native region, eased his sufferings for a while: ‘I wished,’ he says, ‘to retire to Sorrento as to a peaceful harbour: quasi in porto di quiete.’ But he could not rest where he was born! A spell drew him to Ferrara: love is our homeland.

Received coldly by Duke Alfonso, he withdrew once more; he entered the little courts of Mantua, Urbino, and Turin, singing for his supper. He addressed the Metauro, Raphael’s native stream: ‘Slight, but glorious child of the Apennines, restless traveller, to your shores I come, to find safety and rest.’ Armida had reached Raphael’s cradle; she was to preside over the enchantments of the Farnesina.

Surprised by a storm near Vercelli, Tasso celebrated the night there which he spent at a gentleman’s house in his fine dialogue The Father of the Family. At Turin he was refused entry, he was in so wretched a state. Told that Alfonso was about to marry again, he took the road to Ferrara once more. A divine spirit attached itself to the footsteps of this god hidden beneath the smock of a shepherd of Admetus; he thought he saw and heard that spirit: one day, seated by the fire and seeing the sunlight through a window: ‘Ecco l’amico spirito che cortesemente è venuto a favellarmi: Behold, the friendly spirit who comes courteously to speak with me.’ And Torquato talked to a ray of sunlight. He re-entered the fateful city as a bird, fascinated, hurls itself into a serpent’s jaws; misunderstood and repulsed by the courtiers, abused by the servants, he overflowed with complaint, and Alfonso shut him in a madhouse at the Sant’Anna hospital.

Then the poet wrote to one of his friends: ‘Beneath the weight of misfortune, I have renounced all thoughts of glory; I will call myself happy if I can only assuage the thirst that devours me. The idea of captivity without end and indignation at the mistreatment I endure adds to my despair. The state of my beard, my hair, and my clothes makes me an object of disgust even to myself.’

The prisoner begged mercy of all including his pitiless persecutor; from his lyre he drew tones that ought to have made the walls with which his misery was surrounded fall.

‘Piango il morir: non piango il morir solo.

Ma il modo..

Mi saria di conforto aver la tomba,

Ch’altre mole innalzar credea co’ carmi.

I weep at death: not only at death I weep.

But its manner......

It will comfort me to possess the tomb

Of one who thought to raise other monuments in verse.’

Lord Byron has composed a poem on The Lament of Tasso; but he cannot avoid substituting himself for the hero in the scene throughout; in as much as his genius lacks tenderness, his lament is merely an imprecation.

Tasso addressed this plea to the Council of Ancients at Bergamo:

‘Torquato Tasso, not only Bergamese by origin, but by affection, though having lost his father’s inheritance, and his mother’s dowry.yet (after many years serfdom and the weariness of long years) never having, in all his miseries, lost the faith he has in that city (Bergamo) dares to ask her for assistance. Let her beseech the Duke of Ferrara, once my protector and benefactor, to return me to my own place, my relatives and myself. The unfortunate Tasso thus begs your lordships (the magistrates of Bergamo) to send Messir Licino or some other to negotiate my deliverance. The memory of this good deed would end only with my life. Di VV. SS affezionatissimo servitore, Torquato Tasso, prigione e infermo nel ospedal di Sant’ Anna in Ferrara.’

They refused Tasso ink, pen, and paper. He had sung the magnanimous Alfonso, and the magnanimous Alfonso plunged into the depths of a madhouse the one who had shed an imperishable light over his brow. In a sonnet full of grace, the prisoner begs a cat to lend him the glow of her eyes to replace the light he has been deprived of: an inoffensive conceit that proves the poet’s docility and deep distress. ‘As on the ocean that the storm infests and darkens..the weary helmsman lifts his night-bound head towards the stars that gleam about the pole, so I, dear cat, in my wretched trouble. Your eyes seem twin stars that shine before me. O cat, lamp of my wakefulness, beloved cat! Since God keeps you from hurt, since Heaven feeds you on milk and meat, give me your light to write my verses: fatemi luce a scriver queste carmi.’

At night Tasso thought he heard strange noises, the chiming of funeral bells; spectres tormented him. ‘I can stand no more,’ he cried, ‘I succumb!’ Attacked by a grave illness, he thought he saw the Virgin descending miraculously to save him.

‘Egro io languiva, e d’alto sonno avvinto..

Giacea con guancia di pallor dipinta,

Quando di luce incoronata....

Maria, pronta scendesti al mio dolore.

Ill, I languished conquered by deep sleep....

I lay there, pallor spreading o’er my cheeks,

When, crowned with light.......

Mary, you flew swiftly to tend my sorrow.’

Montaigne visited Tasso reduced to this sad misfortune, and gave witness of his compassion. At the same period, Camoëns ended his life in a hospice in Lisbon. What consoled him as he lay dying on his pallet? It was the poems of the prisoner of Ferrara. The captive author of the Gerusalemme, admirer of the poverty-stricken author of the Lusiads, addressed Vasco da Gama: ‘Rejoice to have been sung by the poet, who so deploys his glorious flight that your swift vessels shall not sail so far: Tant’oltre stende il glorioso volo, Che i tuoi spalmati legni andar men lunge.’

So Eridanus’ voice rang out beside the Tagus; so, across the seas, two famous sufferers of like genius and like destiny celebrated each other from one hospice to the other, to the shame of the human race.

How many kings, great or foolish, drowned now in oblivion, believing themselves, at the end of the sixteenth century, persons worthy of remembrance were ignorant even of the names of Tasso and Camoëns! In 1754, one read, for the first time, ‘the name of Washington, in the tale of an obscure battle in the forest, between a crowd of Frenchmen, Englishmen and savages: where is the clerk at Versailles, or purveyor to the Deer Park, where is above all the courtier or academician who would have exchanged names at that time with that American planter?

BkXL:Chap2:Sec3

Ferrara, the 18th of September 1833.

Envy hastened to spread its poison through the open wound. The Accademia della Crusca declared: ‘that Jerusalem Delivered was a cold and leaden compilation, in an obscure and uneven style, full of ridiculous lines, barbarous words, failing to compensate by any kind of beauty for its innumerable faults.’ Fanaticism in support of the works of Ariosto dictated the charge. But cries of popular approval stifled the academic curses: it was no longer possible for Duke Alfonso to prolong the captivity of a man who was guilty only of poetry. The Pope demanded the deliverance of the glory of Italy.

‘Canto XI, Jerusalem Delivered, by Tasso’

Antonio Tempesta (Italian, 1555-1630)

LACMA Collections

Emerging from prison, Tasso was no happier. Leonora was dead. He trailed his sorrows from city to city.

At Loretto, almost dead of hunger, he was on the point, as one of his biographers says, ‘of begging with the hand that had built Armida’s palace.’ At Naples, he experienced a few tender feelings for his native region. ‘Here, he said, ‘are places I left as a child. After many years, I return white-haired, and ill to my native shore: E donde partii fanciullo, or dopo tanti lustri torno ...canuto ed egro alle native spondo.’

He preferred a cell in the monastery of Montoliveto to more sumptuous residences. On a journey he made to Rome, fever seized him and a hospice was yet again his refuge.

From Rome and Florence he returned to Naples, and turning from illness to his immortal poem he re-wrote and spoiled it. He began his verses delle sette giornate del mondo creato: On the Seven Days of Creation, a subject treated by Du Bartas. Tasso had Eve emerging from Adam’s breast, while God ‘sprinkled sweet peace over the limbs of our first father as he slept: ed irrigò di placada quiete tutte le membra al sonnacchioso.’

The poet softens the Biblical scene, and in the tender creations of his lyre woman is simply man’s first dream. The disappointment of having to leave incomplete a pious work, which he considered his hymn of expiation, made the dying Tasso determine to condemn his profane poetry to extinction.

Regarded as lower than a thief by his society, the poet received the offer of an escort to accompany him to Rome, from Marco Sciarra, the famous leader of the condottieri. Presented at the Vatican, the Pope addressed these words to him: ‘Torquato, you will bring honour to this crown, which honours those who have worn it before you’: a eulogy which posterity has confirmed. Tasso replied to the praise by repeating this line of Seneca’s: Magnifica verba mors prope admota excutit: Death will soon carry off those magnificent words.’

Attacked by an illness which he sensed would cure all others, he retired to the monastery of Sant’Onofrio, on the 1st of April 1595. He reached his last refuge in a storm of wind and rain. The monks received him at the portal where Domenichino’s frescoes still wear away today. He saluted the holy fathers: ‘I come among you to die.’ Hospitable cloisters, sanctuaries of religion and poetry, you have lent your solitude to the exiled Dante and the dying Tasso!

‘Convent of Sant’Onofrio’

Le Cose Maravigliose dell'Alma Citta di Roma: Anfiteatro del Mondo - Girolamo Francini, Aggiunta Prospero Parisio (p56, 1600)

Internet Archive Book Images

All treatment was in vain. On the seventh morning of fever the Pope’s doctor declared that the illness gave little reason to hope. Tasso embraced him and thanked him for announcing such good news. Then he gazed heavenwards and, in a heartfelt manner, gave thanks to the God of Mercy.

His weakness increasing, he wished to receive the Eucharist in the monastery church: he dragged himself there leaning on the monks and returned borne in their arms. When he was once more lying on his bed, the Prior interrogated him regarding his last wishes.

‘I had little care for worldly goods during my life; I own still less in dying. I have no testament to make.’

‘– In what place do you wish your grave to be?’

‘– In your church, if you will deign to so honour my remains.’

‘– Do you wish to dictate your own epitaph?’

Now, turning towards his confessor: ‘Father, write this “I render my soul to God who gave it to me and my body to the earth from which it came.” I bequeath to this monastery the sacred image of my Redeemer.’

He took a crucifix in his hands which he had received from the Pope and pressed it to his lips.

Seven days were yet to pass. The afflicted Christian having solicited the favour of holy oil, Cardinal Cinzio arrived bearing the Sovereign Pontiff’s benediction. The dying man displayed great joy. ‘Here, he cried, ‘is the crown that I came to Rome to seek; I hope to be in glory with it tomorrow.’

Virgil asked Augustus to throw the Aeneid into the flames; Tasso begged Cinzio to burn the Gerusalemme. Then he asked to be alone with the crucifix.

The Cardinal had not reached the door when his tears, forcibly repressed, flooded forth: the bell sounded the final agony, and the monks, chanting the prayer for the dying, wept and lamented in the cloister. At this sound, Tasso said to the charitable recluses (he seemed to see them moving round him like shades): ‘My friends, you think I am leaving you; I merely go before you.’

From then onwards he spoke only with his confessor and some learned fathers. Near his last breath, these words came from his mouth, the fruit of his life’s experience: ‘If there were no Death, there would be nothing more wretched in this world than Man.’ On the 25th of April 1595, towards noon, the poet cried out: ‘In manus tuas, Domine...’

The remainder of the sentence could scarcely be heard, as if pronounced by a traveller in the distance.

The author of the Henriade died in the Hôtel de Villette, on the banks of the Seine, and rejected the aid of the Church; the poet of the Gerusalemme died a Christian at Sant’Onofrio: compare, and see how faith adds to the beauty of death.

BkXL:Chap2:Sec4

All that is said of Tasso’s posthumous triumph seems suspect to me. His evil fortune was still more obstinate than is supposed. He did not die at the moment designated for his triumph: he survived that projected triumph by twenty-four hours. He was not wrong about his destiny; he was never crowned, not even after his death; his body was not displayed on the Capitol clothed as a senator in the midst of the crowd and the nation’s tears; he was buried, as he had requested, in the church of Sant’Onofrio. The stone above him (as he also wished) gave no date or name; ten years later, Manso, Marchese della Villa, Tasso’s last friend and Milton’s host, composed an admirable epitaph: ‘Hic jacet Torquatus Tasso: here lies Torquatus Tasso.’ Manso had difficulty in obtaining permission to have it carved: since the monks, religiously observing the testator’s last wishes, opposed any kind of inscription; and yet, without the hic jacet or the name Torquatus Tasso, his remains would have been lost within that monastery of the Janiculum, as those of Poussin were in San Lorenzo in Lucina.

Cardinal Cinzio formed the plan of erecting a mausoleum to the singer of the Holy Sepulchre; an abortive plan. Cardinal Bevilacqua wrote a pompous epitaph destined for the cornice of another future mausoleum, and the thing rested there. Two centuries later Napoleon’s brother occupied himself with a monument at Sorrento: Joseph soon exchanged the cradle of Tasso for the tomb of El Cid.

At last, in our own day, a great funeral monument was begun in memory of the Italian Homer, once a poverty-stricken wanderer like the Greek poet: has the work been completed? Personally, I prefer the little stone in the chapel, of which I have spoken in the Itinerary, to any marble tumulus: ‘I found (in Venice, in 1806) in an empty church, the tomb of the painter (Titian) and had some difficulty finding it: the same thing occurred in Rome (in 1803) regarding Tasso’s grave. After all though, the remains of a religious poet, a victim of misfortune, are not misplaced in being sited in a monastery. The poet of the Gerusalemme seems to have found sanctuary in an unknown sepulchre, as if escaping from the persecutions of men; he filled the world with his fame, and himself remains hidden beneath an orange-tree in Sant’Onofrio.’ (I was right about the orange tree; that is indeed what grows in the interior courtyard of Sant’Onofrio. Note: Paris, 1840)

The Italian commission charged with looking after funeral monuments asked me to take up a collection in France and distribute indulgences from the Muses to all the loyal donors who gave something towards the poet’s monument. July 1830 arrived; my wealth and my credit partook of the fate of Tasso’s remains. Those remains seem to possess a virtue that resists all opulence, rejects all notoriety, strips itself of all honours; great tombs are necessary for little men, little ones for the great.

The God who smiles at my dreams hurling me from the Janiculum along with the Senators of ancient Rome has led me back to Tasso by a different path. Here I can better judge the poet whose three daughters were born in Ferrara: Armida, Erminia and Clorinda.

What exists of the House of Este today? Who thinks now of Obizzo, Niccolò, or Ercole? What name remains: that of Leonora. What do visitors seek in Ferrara: Alfonso’s palace: no, Tasso’s prison. Where do people go in procession century after century: to the sepulchre of the persecutor: no to the dungeon of the persecuted.

Tasso won a memorable victory there: he rendered Ariosto forgotten; the visitor ignores the bones of the poet of Orlando in the Museum, and hastens to see the cell belonging to the poet of Rinaldo in Sant’Onofrio. Seriousness befits a tomb: the man who smiled is forgotten for the man who wept. During life happiness wins merit; after death it loses the prize: in the eyes of future generations, only tragic lives are viewed as beautiful. To those martyrs of intellect, pitilessly consumed on this earth, adversity is counted an accumulation of glory: they sleep with their immortal sufferings in the grave, like kings with their crowns. We other common wretches, we are too little for our troubles to become, for posterity, an adornment to our lives. Stripped of everything in completing my course, my grave will be no temple to me, but a place of renewal; I am no Tasso; I will elude those tender and harmonious predictions penned by the hand of friendship:

‘Tasso wandering from town to town,

And overcome by trouble, one fine day,

Beside a springing laurel bush sat down

That spread its greening boughs around

The tomb of Virgil, every way.etc.’

I hastened to bear my homage to that son of the Muses, so truly consoled by his brothers: a rich Ambassador, I had subscribed to his mausoleum in Rome; an indigent pilgrim on the path of exile, I went to kneel in his cell in Ferrara. I know doubts have been raised about the identity of the location; but, like all true believers, I mock such tales; that crypt, whatever they say, is the very place where the pazzo per amore: crazed by love lived seven whole years; you must pass through the cloisters to reach that gaol where light slips through the bars of iron in a tiny basement window, where the sloping vault that chills your brow drips saltpetre rot onto damp earth that paralyses your feet.

On the walls, outside the cell, and all around the wicket, you can read the names of the worshippers of the god: the statue of Memnon, trembling with harmonies at the touch of dawn, was covered with comments by witnesses of its marvels. I did not scribble my ex-voto there; I hid among the crowd, whose secret prayers would be, because of their very humility, more agreeable to Heaven.

The buildings which contain Tasso’s prison now belong to a hospital open to all sufferers; they are under the protection of the saints: Sancto Torquato sacrum: sacred to Torquato Tasso. At some distance from the holy cell is a dilapidated courtyard; in the midst of this courtyard, the concierge cultivates a flower bed surrounded by a hedge of mallows; the fence, of a pleasant green, supports large and beautiful flowers. I gathered one of its violet-coloured roses that seemed to me as if it was growing at the foot of Calvary. Genius is like Christ; misunderstood, persecuted, beaten with rods, crowned with thorns, hung on a cross by mankind and for mankind, it dies leaving them its light and rises again to be worshipped.

Book XL: Chapter 3: The arrival of Madame la Duchesse de Berry

Ferrara, the 18th of September 1833.

BkXL:Chap3:Sec1

Having gone out on the morning of the 18th, on returning to the Three Crowns I found the street blocked by a crowd; the neighbours gaping from the windows. A guard of a hundred Austrian and Papal soldiers surrounded the inn. The officers of the garrison, the city magistrates, generals, and the pro-legate were waiting for MADAME, of whom a courier in French livery had announced the arrival. The rooms and staircases were decorated with flowers. There was never a finer reception for an exile.

At the appearance of the carriages, the drum beat a tattoo, the regimental band struck up, and the soldiers presented arms. MADAME, caught up in the crowd, had difficulty descending from her calash which had stopped at the door of the hostelry; I hurried up; she recognized me in the midst of the throng. From among the assembled authorities and the beggars who threw themselves towards her, she held out her hand, saying: ‘Mon fils est votre roi! My son is your king! Help me to pass, then.’ I did not find her altered much, only a little thinner; she had something of the air of a knowing child.

I led the way; she gave her arm to Monsieur de Lucchesi; Madame de Podenas followed. We mounted the stairs and entered the apartments between two rows of grenadiers, to the clash of arms, the sound of fanfares, and the vivats of the spectators. I was taken for a major domo, and people applied to me to be presented to Henri V’s mother. My name was linked to hers in the minds of the crowd.

It seems that Madame had been received, from Palermo to Ferrara, with the same marks of respect, despite messages from Louis-Philippe’s envoys. Monsieur de Broglie having had the nerve to demand that the Pope return the exile, Cardinal Bernetti replied: ‘Rome has always been a refuge for fallen greatness. If Bonaparte’s family have in former times found sanctuary with the Father of the Faithful, all the more reason for the same hospitality to be extended towards the families of the Most Christian Kings.’

I thought little of the messages, but I was struck vividly by the contrast: in France, the government insulted a woman they feared; in Italy they only remembered the titles, courage and misfortunes of Madame la Duchesse de Berry.

I was forced to accept my improvised role of First Gentleman of the Chamber. The Princess was extremely amusing: she wore a dress of greyish net, tight at the waist; on her head, a kind of little widow’s bonnet or child’s cap, like that of a schoolgirl doing penance. She buzzed here and there like a cockchafer, and flew about dizzily, with a confident air, amongst the curious, just as she had flitted about the woods of the Vendée. She looked at no one and recognized no one; I was obliged to pull disrespectfully at her her robe, or block the way, saying: ‘Madame, this is the Austrian Commandant, the officer in white; Madame, this is the Commander of the Papal forces, the officer in blue. Madame, this is the pro-legate, the tall young priest in black.’ She stopped, said a few words in Italian or French, not correctly exactly, but in a lively, open, and pleasant way, such that the disagreeable seemed agreeable: her allure was unlike any other. I felt almost embarrassed, and yet I felt no anxiety about the effect produced by the little escapee from fire and prison.

‘Duchess of Berry’

'Die Maitressenwirthschaft in Frankreich unter Ludwig XIV. & XV. Pracht-Ausgabe, Vol 01 - Theodor Griesinger (p464, 1874)

The British Library

A comical confusion ensued. There is something I must say in all modesty; the vain clamour surrounding my life increases the more my life’s true silence deepens. I cannot stop at an inn these days, in France or abroad, without being immediately assailed. To the old Italy, I am the defender of religion; to the young, the defender of liberty; to the authorities, I have the honour to be Sua Eccellenza GIA ambasciatore di Francia: the FORMER Ambassador of France to Verona and Rome. The ladies, all doubtless of a rare beauty, endow Atala the Floridian girl and the Moor Aben-Hamet with the language of Angelica and Aquilant the Black. Then I find students appear, old priests in skullcaps, ladies whom I thank for their expressions of feeling and favour; and then the medicanti, too well brought up to think a former ambassador as much of a rogue as their lordships.

Now, my admirers rushed to the Three Crowns hotel, with the crowd attracted by Madame le Duchesse de Berry: they drove me into a window corner and began a harangue intended for Marie-Caroline. In the mental chaos, the two crowds sometimes mistook master and mistress: I was saluted as Your Royal Highness and MADAME told me she had been complimented on Le Génie du Christianisme: we exchanged roles. The Princess was charmed to have created a work in four volumes, and I was proud to have been taken for a daughter of kings.

Suddenly the Princess vanished: she went off on foot, with Count Lucchesi, to see Tasso’s cell; she knew all about prisons. Mother of the exiled orphan, of the child heir of Saint Louis, Marie-Caroline emerging from the fortress of Blaye only to seek a poet’s dungeon in Renée of France’s city, is something unique in the history of fate and human glory. The venerable exiles of Prague might have passed through Ferrara a hundred times without such an idea entering their heads; but Madame de Berry is a Neapolitan, she is a compatriot of Tasso who said: Ho desiderio di Napoli, come l’anime ben disposte, del paradise: I long for Naples, as untroubled souls long for Paradise.’

When I was in opposition and disgrace; and the decrees were being concocted clandestinely at the Palace, and still remained hidden in joyous hearts: the Duchesse de Berry, one day, saw an engraving representing the poet of the Gerusalemme at the bars of his cell: ‘I hope,’ she said, ‘we shall soon see Chateaubriand thus.’ Words spoken in prosperity, to be no more taken account of, than some plan conceived while drunk. I should have joined MADAME in Tasso’s very cell, having endured a police gaol for her. What elevation of feeling in the noble Princess, what a mark of esteem she showed me in addressing herself to me in the hour of her misfortune regarding the project she had conceived! If her initial request valued my talents too highly, her confidence was less at fault in regard to my character.

Book XL: Chapter 4: Mademoiselle Lebeschu – Count Lucchesi-Palli – Discussion – Dinner – Bugeaud the gaoler – Madame de Saint-Priest, Monsieur de Saint-Priest – Madame de Podenas – Our Troop – My refusal to go to Prague – I yield to a word

Ferrara, the 18th of September 1833.

BkXL:Chap4:Sec1

Monsieur de Saint-Priest, Madame de Saint-Priest and Monsieur Sala arrived. The latter had been an officer in the Royal Guard, and he had replaced Monsieur Delloye, a Major in the same Guard, in the business of publishing my works. Two hours after Madame’s arrival, I met Mademoiselle Lebeschu, my compatriot; she hastened to tell me of the hopes that they wished to place in me. Mademoiselle Lebeschu figured in the Carlo Alberto trial.

Returning from her poetic visit, the Duchess de Berry had me summoned: she was waiting for me with Monsieur le Comte Lucchesi and Madame de Podenas.

Count Lucchesi-Palli is tall and dark: MADAME calls him a Tancred towards women. His manner towards his wife, the princess, is a masterpiece of propriety, neither humble nor arrogant, a respectful mixture of a husband’s authority and a subject’s submission.

Madame immediately talked of her affairs; she thanked me for arriving at her invitation; she told me she would go to Prague, not only to see her family, but to obtain her son’s certificate of majority: then she declared that she would take me with her.

This declaration, which I had not expected, dismayed me: to return to Prague! I presented the objections that sprang to mind.

If I were to go to Prague with Madame and she obtained what she desired, the honour of the victory would no longer belong wholly to Henri V’s mother, and that would not be right; if Charles X insisted on refusing a certificate of majority, in my presence (as I was persuaded he would), I would lose all credit. It thus seemed to me better to keep me in reserve, in case Madame failed in her negotiations.

Her Royal Highness argued against my reasons: she maintained she could have no effect in Prague if I did not accompany her; that I made her grandparents fearful; that she consented to allow me the credit for victory and the honour of attaching my name to her son’s coming of age.

Monsieur and Madame de Saint-Priest entered in the midst of this discussion and insisted that the Princess was right. I persisted in my refusal. Dinner was announced.

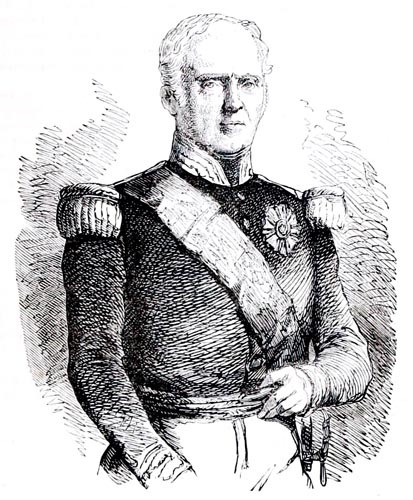

MADAME was in high spirits. She told me, in the most amusing manner, of her quarrels at Blaye with General Bugeaud. Bugeaud attacked her politics and grew angry; Madame was angrier than he: they screamed at each other like two eagles, and she drove him from the room. Her Royal Highness suppressed certain details which she might make me party to if I were to accompany her. She would not let Bugeaud alone; she mistreated him in every way: ‘You know, I asked for you on four occasions?’ she told me. ‘Bugeaud passed my requests to D’Argout. D’Argout replied that Bugeaud was a fool, that he should have refused you entrance out of hand; he has good sense (de bon goût), that Monsieur D’Argout.’ MADAME stressed the rhyming words, in her Italian accent.

‘Bugeaud’

'Die Le Jardin des Plantes: Description - Pierre Boitard, Jules Gabriel Janin (p601, 1851)

Internet Archive Book Images

However, the rumour of my refusal having spread, the faithful became anxious. After dinner Mademoiselle Lebeschu came to lecture me in my room; Monsieur de Saint-Priest, a man of wit and reason, first sent Monsieur Sala to me, then replaced him and exhorted me in turn. ‘Monsieur de La Ferronays has been despatched to the Hradschin, in order to smooth out any initial difficulties. Monsieur de Montbel has arrived; he was charged with going to Rome and bringing back the marriage contract, written in due and proper form, which was in the hands of Cardinal Zurla.’

Supposing,’ continued Monsieur de Saint-Priest, ‘that Charles X refuses to sign a deed of majority, would it not be a good thing for MADAME to obtain a statement from her son? What form should such a declaration take?’ – ‘A brief note,’ I replied, ‘in which Henri should protest against Philippe’s usurpation.’

Monsieur de Saint-Priest carried my words to MADAME. My resistance continued to pre-occupy those around the Princess. Madame de Saint-Priest, with her elevation of feeling, seemed the most active in her regrets. Madame de Podenas never lost her habit of smiling serenely in order to display her excellent teeth: her calm in the midst of our agitation was more sensible.

We bore a strong resemblance to a troop of strolling players, French actors, performing, in Ferrara and by consent of the noble magistrates of the city, the drama of The Fugitive Princess, or The Persecuted Mother. Stage right rose Tasso’s prison, stage left Ariosto’s mansion; in the background the palace where Leonora and Alfonso’s celebrations were enacted. These Royals without a kingdom, this agitated court contained by two travelling calashes, with the hotel of the Three Crowns as their palace at night; these State councils held in the room of an inn, capped all the varied scenes of my existence. I left my knight’s helm in the wings and picked up my straw hat; I travelled about with the true monarchy rolled up in my trunk, while the actual monarchy displayed its frills and flounces at the Tuileries. Voltaire has all the kings attending the Carnival in Venice with Ahmed III: Ivan, Emperor of all the Russias; Charles Edward, King of England; the two Kings of Poland; Theodore, King of Corsica; and four Serene Highnesses. ‘Sire, your Majesty’s carriage is at Padua, and the boat is ready. Sire, Your Majesty may leave when he wishes. Sire, believe me, they won’t give Your Majesty any more credit, nor me neither, and we may both be in gaol by nightfall.’

As for me, I say with Candide: ‘Gentlemen, why are all of you kings? I confess I am not and nor is Martin.’

It was eleven at night; I hoped I had acquitted myself and obtained Madame’s leave of absence. I was a long way out in my reckoning! Madame did not give up her aims so easily; she had not questioned me about the state of France, because, preoccupied by my resistance to her plans, she had given that precedence. Monsieur de Saint-Priest, entering my room, brought me the draft of a letter Her Royal Highness proposed to send to Charles X. ‘What,’ I exclaimed, ‘Madame persists in her intention? She wants me to take this letter? But it is impossible, even in practice, for me to cross Germany; my passport is only valid for Switzerland and Italy.’

‘– You can accompany us to the Austrian border,’ Monsieur de Saint-Priest replied; ‘Madame will take you in her carriage; the frontier once crossed you can travel in your own calash, and arrive a day and a half before us.’

I hurried to the Princess’ apartment; I repeated my objections: Henri V’s mother said: ‘Do not desert me.’ Those words ended the contest; I yielded; Madame seemed full of joy. Poor woman! She wept so! How could I resist courage, adversity, and fallen greatness, when reduced to sheltering beneath my protection! Another Princess, Madame la Dauphine, also thanked me for my unfruitful service: Carlsbad and Ferrara were places of exile under two different suns, and I received my life’s greatest honours there.

Madame left in the early morning, on the 19th, for Padua where she would meet me; she was to halt at Cataio, at the Duke of Modena’s. I had a hundred things I wished to see in Ferrara, palaces, paintings, manuscripts, but had to be content with Tasso’s prison. I set out a few hours after her Royal Highness. I arrived that night at Padua. I sent Hyacinthe to fetch my light baggage, fit for a German student, from Venice, and I retired sadly to sleep at the Golden Star, which mine had never been.

Book XL: Chapter 5: Padua – Tombs – Zanze’s manuscript

Padua, the 20th of September 1833.

BkXL:Chap5:Sec1

On Friday, the 20th of September, I spent part of the morning writing to my friends about my change of destination. The members of Madame’s entourage arrived in succession.

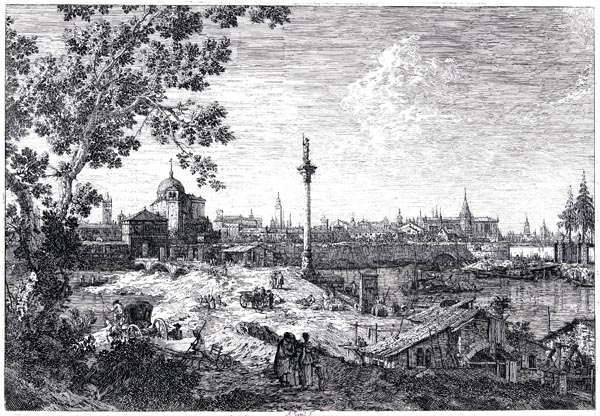

‘Imaginary View of Padua, from the Vedute’

Giovanni Antonio Canal, called Canaletto (Italian, 1697 - 1768)

Yale University Art Gallery

Having nothing to do, I went out with a guide. We visited the churches of Santa Giustina and Sant’Antonio di Padua. The former, the work of Jerome of Brescia, is very majestic: from the depths of the nave one finds windows opening only at a great height, so that the church is lit without one being aware of where the light originates. This church has several fine paintings by Paolo Veronese, Liberi, Palma etc.

Sant’Antonio di Padua (il Santo) presents a Greek Gothic exterior, a style peculiar to the ancient churches of Venice. St Anthony’s chapel is by Jacopo Sansovino and his son Francesco: one sees it is so immediately; the decorations and design are in the style of the loggetta of St Mark’s bell-tower.

A signora in a green dress, with a straw hat covered by veil, was praying before the chapel of the saint, a servant in livery was also at prayer behind her: I assumed she was asking relief for some moral or physical distress; I was not wrong; I saw her again in the street: a woman of forty, pale, thin, walking stiffly, and with an air of suffering, I had thought her in love or afflicted with an infirmity. She emerged from the church with hope: in the space of time during which she had offered her fervent prayer to Heaven, had she forgotten her grief, could she be truly cured?

Il Santo is full of tombs; that of Bembo is famous. In the cloister one finds the tomb of young D’Orbesan, dead in 1595.

‘Gallus eram, Patavi morior, spes una parentum!

A Frenchman I was, I died in Padua, my parent’s only hope!’

D’Orbesan’s French epitaph ends with a line that a great poet might wish they had written.

‘Car il n’est si beau jour qui n’amène sa nuit.

For there is no day so beautiful it lacks its night.’

Charles-Guy Patin is buried in the cathedral: his father’s skill could not save him: the same who had treated a young gentleman aged seven, who was bled thirteen times and was cured in fifteen days, as if by a miracle.

The ancients excelled in composing funeral inscriptions: ‘here lies Epictetus,’ said his stone, ‘slave, forger, poor as Irus, and yet the favourite of the gods.’

Among the moderns, Camoëns composed the most magnificent epitaph, that of John III of Portugal: ‘What rests in this great sepulchre? What is denoted by the illustrious coats of arms on this massive escutcheon? Nothing! For that is what all things attain. May the earth lie lightly on him now, as he once weighed heavily on the Moors.’

My Paduan guide was a chatterer, very different from Antonio in Venice; he told me, at every opportunity, of that great tyrant Angelo: he announced the name of every shop and every café on every street; at the Santo he insisted on uttering for me the carefully preserved language of the preachers of the Adriatic. Did the tradition of such sermons derive from those songs that the fishermen of the Middle Ages (following the example of the ancient Greeks) sang to the fish as a charm? Some of those pelagian ballads in Anglo-Saxon are extant.

Of Livy, no trace; I would gladly, like the inhabitant of Cadiz, have made the journey to Rome expressly to see him while he was alive; I would gladly have sold my land, like Panormita, to buy a few fragments of his History of Rome, or, like Henri IV, offered a province for a Decad. There was no sign of the haberdasher of Saumur; he who once set himself in all good faith to covering some handball racquets with a manuscript of Livy, sold to him as waste paper by the apothecary of a monastery belonging to Fontevrault Abbey.

When I returned to the Golden Star, Hyacinthe was back from Venice. I had suggested he go to Zanze’s house, and beg her pardon on my behalf for my having left without seeing her. He found the mother and daughter in a fine temper; they had just finished reading Le mie Prigioni. The mother said that Silvio was a wretch: he had written that Brollo had grabbed him, Pellico, by the leg, when he, Pellico, was standing on a table. The daughter shouted: ‘Pellico is a slanderer; and he’s an ingrate. After the services I rendered him, he seeks to dishonour me.’ She threatened to have the work seized and to attack the author in front of the Tribunal; she had begun a refutation of the book: Zanze is not only an artist, but a woman of letters.

Hyacinthe begged her to send me the unfinished refutation: she hesitated then gave him the manuscript: she was pale and tired from her work. The old gaoler’s wife kept trying to sell him her daughter’s embroidery and mosaic work. If ever I return to Venice I will conduct myself better towards Madame Brollo than I did towards Abou Gosch, leader of the hill-Arabs of Jerusalem; I promised the latter a basket of rice from Damietta, and I never sent it to him.

Here is the translation of Zanze’s commentary:

‘The Venetian is amazed that anyone has had the audacity to pen two novelistic scenes about her created from and filled with impious lies. She strongly objects to an author who can use another person to advance his career, and who makes sport of an honest young girl who is educated and religious, esteemed, loved and highly thought of by everyone.

How can Silvio say that at the age of thirteen (which was my age when he says he knew me); how can he say that I visited his rooms daily when I swear to having gone there very rarely, and always accompanied by my father, mother or brother? How can he say that I confessed my love to him, I who was still at school, I who scarcely knowing anything knew neither love, nor the world; consecrated solely, as I was, to the duties of religion, and those of an obedient daughter, always occupied with my work, my only pleasure?

I swear that I have never spoken to him (Pellico) of love or anything else; and if I saw him occasionally, I regarded him with the eye of pity, because my heart is full of compassion for my fellow-creatures. Also I detested the place where my father worked solely through ill-luck: he once occupied a better place, but having been a fine soldier, having served the republic and then his sovereign, he was placed in that employment against his will and that of his family.

It is quite wrong (falsissimo) that I ever held the aforementioned Silvio’s hand, either as if it were my father’s, or my brother’s; firstly because, though very young and lacking experience, I had received enough of an education to know my duty.

How can he say I embraced him, I who did not even embrace my brother: such were the scruples lodged in my heart by the education I received in the convents where my father always sent me!

Truly, I seem better known to him (Pellico) than he could have been to me, since I spent my days in the company of my brothers in a room neighbouring his; was that not the room where my elder brothers worked and studied, and a place where I was allowed to stay with them? How can he say that I spoke to him about family matters, that I unburdened my heart to him regarding my mother’s severity and my father’s kindness? Far from having any reason to complain of her, she was ever my friend.

How can he say that he shouted at me for bringing him execrable coffee? I know no one who can say they have had the audacity to shout at me, they having all valued me as the soul of kindness.

I am a thousand times astonished that a man of intellect and talent has dared to vaunt such things unjustly where an honest young woman is concerned, in a way which might lose her the esteem all profess towards her, and even the love and respect of her husband, and destroy her peace and tranquillity in the arms of her family and those of her daughter.

I find myself angry beyond measure with the author for having exhibited me in a public work in this way, and for taking the liberty of quoting my name at every opportunity.

And yet he has been careful to write the name Tremerello instead of that of Mandricardo, the name of the person who carried messages for him. And the latter I could have told him more about, because I knew how faithless he was and self-interested. He would have sacrificed anyone for food and drink; he was disloyal to all those who through their misfortune were in poverty, and who were unable to grease his palm as he wished. He treated those unfortunates worse than beasts; but when I saw him, I reproached him and told me father about him, my heart being unable to endure such treatment of my fellow-creatures. He (Mandricardo) was only kind to those who gave him buona mancia (fat rewards) and gave him plenty to eat; may Heaven forgive him! But he will have to render account for his evil actions towards his fellow-creatures, and for the hatred he showed me because I remonstrated with him. For as unworthy an object as that, Silvio shows concern, while for me, who do not merit being so exhibited, he has shown not the least regard.

But I know where to turn for true justice; I do not agree to being, I do not wish to be, named in public, whether for good or evil.

I am happy in the arms of a husband who loves me so, and who is true and virtuously cherished in return, well knowing the integrity not only of my conduct but also of my feelings. And I will be, despite the man who sees fit to exploit me in the interests of his writings, which are unfounded and full of untruths.!

Silvio will forgive my fury, but he should have expected it, once I clearly knew his conduct in regard to me.

This is the recompense for all my family has done, treating him (Pellico) with the humanity that every creature condemned to like disgrace deserves, and without regard to the orders given concerning him.

And yet I swear that all he has said about me is false. Perhaps Silvio may have been badly informed about me, but he cannot truthfully repeat such false things, solely to have a better story on which to found his book.

I would say more; but my domestic tasks will not allow me to waste any more time. I can only thank Signor Silvio for his book, and for having created in my breast, innocent of fault, continual anxiety and perhaps endless unhappiness.’

This literal translation is far from rendering the feminine verve, foreign grace, and lively naivety of the text; the dialect Zanze uses exhales an earthy perfume impossible to transfuse into another language. This apologia with its incorrect phrasing, nebulous, and incomplete, like the obscure edges of a group of figures by Albani, this manuscript, with its defective or Venetian handwriting, is a monument to Greek womanhood, but that of the age in which bishops of Thessaly sang the love of Theagenes and Chariclea. I prefer the little gaoler’s two pages to all the dialogues of the great Isotta who nevertheless pleaded for Eve against Adam, as Zanze pleaded on her own behalf against Pellico. Furthermore, my lovely Provencal compatriots of former days are recalled by this daughter of Venice through the idiom of those intermediate generations in whose houses the language of the conquered is not yet wholly dead, and the language of the conquerors not yet wholly formed.

Which of Pellico or Zanze is right? What is the essence of the argument? It is about a simple exchange of confidences, a questionable embrace, which, ultimately perhaps was never meant for him who received it. The married woman chooses not to recognize herself in the delightful girl whom the prisoner depicts; but she contests the matter with so much charm that she proves it by denying it. The portrait of Zanze in the plaintiff’s memoir is so like, that one rediscovers it in the defendant: the same feelings of religiosity, humanity, the same reserve, the same tone of intimacy, the same gentle and tender lack of method.

Zanze is full of force when she affirms, with passionate candour, that she would not have dared embrace her own brother, far less Monsieur Pellico. Zanze’s filial piety is extremely touching, when she transforms Brollo into a former Republican soldier, reduced to the level of a gaoler per sola combazione: solely by ill-fortune.

Zanze is quite admirable in that phrase: Pellico had concealed the name of a disreputable man, and yet had no fear in revealing that of an innocent creature full of compassion for the wretched prisoners.

Zanze is not seduced by the idea of being immortalized in an immortal work; that idea never even enters her mind: she is simply astonished at the man’s indiscretion; that man, as the offended girl believed, sacrificed a girl’s reputation for the sake of his work, without concern for the trouble he might cause, only seeking to tell a tale for the benefit of his fame. A palpable fear overcomes Zante; might the prisoner’s revelations inspire her husband’s jealousy?

The paragraph that ends the apologia is moving and eloquent:

‘I can only thank Signor Silvio for his book, and for having created in my breast, innocent of fault, continual anxiety and perhaps endless unhappiness: una continua inquietudine e forse una perpetua infelicità.’

Over these last lines written in a tired hand, tears have been visibly shed.

I, a stranger to trial proceedings, wish to omit nothing. I therefore maintain that the Zanze of Mie Prigioni is Zanze according to the Muses, and that the Zanze of the apologia is the true Zanze according to history. I ignore the defect of height that I seemed to remember in the daughter of a former soldier of the Republic; I was wrong: the Angelica of Silvio’s prison is formed like the stem of a reed, like the shoot of a palm-tree. I declare to her that no one in my Memoirs pleases me so much, not even excluding my sylph. Between Pellico and Zanze herself, with the aid of the manuscript deposited with me, it will be a great wonder if the Veneziana does not go down to posterity! Yes, Zanze, you will take your place among the female shades born about the poet, when he dreams to the sound of his lyre. Those delicate shades are orphans of a vanished harmony and a reverie that has ended, still living between earth and heaven, inhabiting both regions at once. ‘The beauty of paradise would not be complete if you were not there to grace it’ sings a troubadour to his mistress absent in death.

Book XL: Chapter 6: Unexpected news – The Governor of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia

Padua, the 20th of September 1833.

BkXL:Chap6:Sec1

History has just arrived to strangle romance. I had barely finished reading Zanze’s defence, at The Golden Star, when Monsieur Saint-Priest entered my room saying: ‘Here is news.’ A letter from Her Royal Highness informed us that the Governor of the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia had been presented to her at Cataio and had announced to the Princess the impossibility of his allowing her to continue her journey. Madame requested my immediate departure.

At that instant an aide-de-camp of the Governor knocked at my door and asked if it would suit me to receive the General. In response I went to His Excellency’s apartment, as he was staying like me at The Golden Star.

The Governor was an excellent fellow.

‘Know, Monsieur le Vicomte,’ he said, ‘that my orders concerning Madame la Duchesse de Berry were dated the 28th of August: her Royal Highness tells me she has passports of a later date and a letter from the Emperor. Behold, on the 17th of this month I receive a despatch in the middle of the night: a despatch, dated the 15th, from Vienna, telling me to execute my orders of the 28th August, and not allow Madame la Duchesse de Berry to travel beyond Udine or Trieste. Witness, my dear and illustrious Vicomte, the extent of my misfortune! To arrest a princess I admire and respect, if she will not conform to my sovereign’s wishes! For the Princess did not welcome me; she told me she would do as she pleased. Dear Vicomte, if you could persuade Her Royal Highness to remain in Venice or Trieste while I await fresh instructions from the Court? I will stamp your passport for Prague; you can go there swiftly with experiencing the least impediment, and you can arrange everything; since my Court will certainly only yield to a formal request. Render me this service, I beg you.’

I was touched by the candour of the noble officer. Comparing the date of the 15th of September with my departure from Paris on the 3rd I was struck by an idea: my interview with Madame and the coincidence of Henri V’s majority may well have frightened Louis Philippe’s cabinet. A despatch from Monsieur de Broglie, sent with a note from Monsieur le Comte de Saint-Aulaire, may have decided the Vienna Chancellery in favour of a renewal of the ban of the 28th of August. It is possible that I guess wrongly and that the event I suspect did not take place; but two gentlemen, both Peers of France under Louis XVIII, both violators of their oath, were worthy of being the instruments, after all, of so ungenerous a policy against a woman, and the mother of the legitimate king. Is it so astonishing that the France of today increasingly confirms the high opinion in which it holds the people of the courts of former times?

I took care not to show my private thoughts. Persecution had altered my feelings on the subject of the trip to Prague; I was now so desirous of working alone in my royal mistress’ interest, that I had opposed undertaking it with her when the roads were open to her. I concealed my true sentiments, and wishing to maintain the Governor’s good will in granting me a passport, I added to his loyal disquiet; I replied:

‘Monsieur le Gouverneur, you are proposing what is difficult for me. You know Madame la Duchesse de Berry; she is not the woman to be led where one wishes; if she has made up her mind nothing will change it. Who knows? Perhaps it suits her to be arrested by the Emperor of Austria, her uncle, since she has previously been thrown in a dungeon by Louis-Philippe another uncle! Legitimate kings and illegitimate kings act in the same way. Louis-Philippe dethroned Henri IV’s descendant, while Francis II will prevent a mother being reunited with her son; Prince von Metternich will replace General Bugeaud in his role wonderfully well.’

The Governor was beside himself: ‘Oh! Vicomte, how right you are! Such propaganda everywhere! Youth will no longer listen to us! No more in Venetia than in Lombardy or Piedmont.’– ‘Or the Romagna!’ I cried, ‘or Naples! Or Sicily! Or on the banks of the Rhine! Or anywhere!’ – ‘Oh, oh oh!’ cried the Governor,’ things cannot remain so: always sword in hand, an army in arms, without fighting. France and England setting our people an example! Now, after the Carbonari, Young Italy! Young Italy! Who ever heard of such a thing?’

‘– Sir,’ I said, ‘I will bend all my efforts to persuading Madame to grant you a few days grace; have the goodness to grant me a passport: that kindness alone may prevent Her Royal Highness from pursuing her initial resolution.’

‘– I will take it upon myself,’ the Governor told me, having been reassured,’ to allow Madame to pass through Venice to reach Trieste; if she dawdles a little on the way, she will reach the latter city along with the orders you go to seek, and we will be saved. The representative in Padua will grant you a visa for Prague, in exchange for which you will leave him a letter announcing Her Royal Highness’ resolve not to travel beyond Trieste. What an age we live in! What an age! I am pleased to be old, my dear and illustrious Vicomte, so I will not be forced to see what is coming next.’

In insisting on the passport, I reproached myself silently for no doubt taking advantage of the Governor’s utter lack of guile, since he might well be more culpable in letting me enter Bohemia than if he had yielded to the Duchesse de Berry. My whole anxiety was lest some idiot in the Italian police made difficulties regarding the visa. When the representative in Padua came to see me, I found about him the look of the secretariat, an air of protocol, the mark of the prefecture as if he had been nurtured by French administration. That talent for bureaucracy made me tremble. The moment he told me he had been a commissary in the allied army in the Bouches-du-Rhône department, my hopes revived: I attacked my enemy by swiftly enhancing his self-esteem. I declared that the strict discipline of the troops stationed in Provence had been noticeable. I knew nothing about it, but the representative, replying with overflowing admiration, hastened to expedite my business: the moment I had obtained my visa I ceased to worry.

Book XL: Chapter 7: A letter from Madame to Charles X and Henri V – Monsieur de Montbel – My note to the Governor – I leave for Prague

Padua, the 20th of September 1833.

BkXL:Chap7:Sec1

The Duchesse de Berry returned from Cataio at nine in the evening: she seemed very animated; as for me, the more at peace I had been, the more I wished for combat: if people attacked us, we must defend ourselves. I proposed, half in jest, to Her Royal Highness, that I would take her to Prague in disguise, and the two of us would kidnap Henri V. It only remained to consider where we might deposit our prize. Italy was not suitable because of the weakness of its princes; the absolutist grand monarchies could not be considered for a thousand reasons. Holland and England remained: I preferred the former because along with a constitutional government it possessed an able king.

We deferred this extreme measure; we fell back on more reasonable ones: the weight of the whole affair fell on my shoulders. I would leave alone with a letter from MADAME: I would demand the certificate of majority; following the grandparents’ reply, I would send a courier to Her Royal Highness who would await my dispatch in Trieste. MADAME added a letter for Henri to that for the old king; I would hand it to the young prince dependent on the circumstances. The address on the note was itself a protest against the reservations expressed in Prague. Here are the letter and the note:

‘Ferrara, 19th of September 1833.

My dear father-in-law in a moment as crucial to Henri’s future as this one, allow me to address you in complete confidence. I am not relying solely on my own ideas regarding so important a subject; in this grave matter, I have chosen, on the contrary, to consult those who have shown me most loyalty and devotion. Monsieur de Chateaubriand is naturally to be found at their head.

He has confirmed what I already thought, that in France all the royalists, with regard to the 29th of September, consider a decree certifying Henri’s majority and rights, as indispensable. If the faithful M*** is with you at the moment, I invoke him as witness that I know the situation to be in accord with what I say.

Monsieur de Chateaubriand will explain his ideas on the question of the decree to the King; he says with reason, it seems to me, that it should simply certify Henri’s majority and not be a manifesto: I think you will approve his manner of viewing the matter. Finally, my dear father-in-law, I leave it to him to obtain your attention and bring about a decision on this vital point. I am occupied with much more, I assure you, than what concerns me, and the interests of my Henri, which are those of France, take precedence over mine. I think I have shown him that I know how to expose myself to danger on his behalf, and that I do not shrink from any sacrifice; he will find me ever the same.

Monsieur de Montbel handed me your letter on his arrival: I read it with a lively sense of gratitude; to see you again, to embrace my children, will always be my dearest wish. Monsieur de Montbel will have written to you saying that I have done all you asked; I hope you will be satisfied with my eagerness to please you and display my respect and tenderness towards you. I have now only one desire, to be in Prague for the 29th of September, and, though my health is much altered, I hope to be there. In any event, Monsieur de Chateaubriand will precede me. I beg the King to receive him with kindness and to hear what he will say on my behalf. Believe, my dear father, in all my deepest sentiments, etc.

P. S. Padua, the 20th of September – My letter was complete when I was told of the order that I was not to continue my journey: my surprise matches my sorrow. I cannot believe that such an order could emanate from the heart of the King; my enemies alone must have dictated it. What will France say? And how Philippe will triumph! I can only insist on the departure of the Vicomte de Chateaubriand, and charge him with saying to the King what it is too painful for me to write to him at this instant.’

Note addressed to: ‘HIS MAJESTY HENRI V, MY VERY DEAR SON, PRAGUE.

Padua, the 20th of September 1833.

I was on the brink of arriving in Prague to embrace you, my dear Henri, when an unforeseen obstacle halted my journey.

I am sending Monsieur de Chateaubriand in my place to handle your affairs and mine. Trust, my dear friend, in what he says to you on my behalf and have faith in my most tender affection. In embracing you and your sister, I am

Your affectionate mother and friend,

CAROLINE.’

Monsieur de Montbel reached Padua from Rome in the midst of our discussions. The little court of Padua was in a sulk; it blamed Monsieur de Blacas for the order from Vienna. Monsieur de Montbel, a very sensible gentleman, had no recourse but to take refuge with me, though he feared me; on seeing this colleague of Monsieur de Polignac’s, I told myself that he had written, without realising it, the history of the Duc de Reichstadt, and had admired the Archdukes, all of two hundred miles away from Prague, the place of exile of the Duc de Bordeaux; if he, Monsieur de Montbel, had chosen to throw Saint Louis’ monarchy out of the window along with the monarchies of this earthly world, it was a minor event that he had not anticipated. I was gracious towards le Comte de Montbel; I spoke to him about the Coliseum. He returned to Vienna to place himself at Prince von Metternich’s disposal and serve as an intermediary in any correspondence with Monsieur de Blacas. At eleven, I wrote the letter we had agreed upon to the Governor: I was careful of MADAME’s dignity, not committing her Royal Highness in any way, and preserving her complete freedom of action.

‘Padua, this 20th of September 1833.

Monsieur le Gouverneur,

Her Royal Highness, Madame la Duchesse de Berry wishes to conform, for the moment, to the orders which you have communicated. Her intention is to travel to Venice on her way to Trieste; there, after receiving the information which I shall have the honour of sending her, she will decide further.

Accept, I beg you, my most sincere thanks, and the assurance of my deepest regard, with which I am.

Monsieur le Gouverneur,

Your very humble and obedient servant,

CHATEAUBRIAND.’

The representative, on reading this letter, was quite content. Once MADAME had left the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia he and the Governor were no longer responsible for her; the actions and intentions of the Duchesse de Berry at Trieste only concerned the authorities of Istria or Frioul; it was for each to rid themselves of the problem: there is a certain game where one hastens to pass a piece of burning paper to one’s neighbour.

At ten, I took leave of the Princess: she gave the fate of herself and her son into my hands. She made me a king of France after a fashion. There was a village in Belgium that once gave me four votes in their search for a successor to mount the throne that Philippe’s son-in-law occupies. I said to MADAME: ‘I submit to Your Royal Highness’ will, but I fear to ruin her hopes. I may obtain nothing in Prague.’ She pushed me towards the door: ‘Go, you can do it.’

At eleven, I climbed into my carriage: it was a wet night. It felt as though I was returning to Venice since I took the road to Mestre; I would rather have been going to see Zanze again than Charles X.

End of Book XL