François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XLI: Return to Prague 1833

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XLI: Chapter 1: JOURNAL FROM PADUA TO PRAGUE, 20TH TO 26TH SEPTEMBER 1833: – Conegliano – A translation of Le Dernier Abencérage – Udine – The Countess Samoilova – Monsieur de La Ferronays – A priest – Carinthia – The Drava – A little peasant – Forges – Lunch at the Hamlet of St Michael

- Book XLI: Chapter 2: The Tauern Pass – A Cemetery – Atala: how altered – Sunrise – Salzburg – A military review – Happy peasants – Vöcklabruck – Plancoët and my aunt – Night – German towns and Italian towns – Linz

- Book XLI: Chapter 3: The Danube – Waldmünchen – Woods – Combourg – Lucile – Travellers – Prague

- Book XLI: Chapter 4: Madame de Gontaut – Young France – Madame la Dauphine – Journey to Bustehrad

- Book XLI: Chapter 5: Bustehrad – Charles X’s sleep – Henri V – The young men’s reception

- Book XLI: Chapter 6: The peasant-girl and the ladder – Dinner at Bustehrad – Madame de Narbonne – Henri V – A game of Whist – Charles X – My incredulity regarding the declaration of majority – A reading fom the newspaper – Scene with the young men in Prague – I leave for France – Bustehrad by night

- Book XLI: Chapter 7: A meeting at Schlau – An empty Carlsbad – Hollfeld – Bamberg: the librarian and the young lady – My various Saint Francis’ Days – Proofs of religion – France

Book XLI: Chapter 1: JOURNAL FROM PADUA TO PRAGUE, 20TH TO 26TH SEPTEMBER 1833: – Conegliano – A translation of Le Dernier Abencérage – Udine – The Countess Samoilova – Monsieur de La Ferronays – A priest – Carinthia – The Drava – A little peasant – Forges – Lunch at the Hamlet of St Michael

BkXLI:Chap1:Sec1

I was sorry, on passing Mestre towards the end of the night, that I was unable to visit the shore: perhaps a distant lighthouse among the last lagoons might have indicated the loveliest island of the ancient world, as a little fire revealed the first islands of the New World to Christopher Columbus. It was at Mestre that I embarked for Venice on my first visit in 1806: fugit aetas: time flies.

I lunched at Conegliano: there I was complimented by the friends of a lady who had translated L’Abencèrage, and indeed resembled Blanca: ‘He saw a young woman emerge, dressed almost like the Gothic queens carved on the monuments in our ancient abbeys.a black mantilla was thrown over her head; with her left hand she held it tightly beneath her chin like a hood, so that nothing could be seen of her face but her large eyes and rosy mouth.’ I am repaying my debt to the translator of my Spanish reveries, by reproducing her portrait here.

While I regained my carriage, a priest harangued me regarding Le Génie du Christianisme. I traversed the theatre of victories which led Bonaparte to invade our freedoms.

Udine is a fine town: I saw a portico there which imitated the Doge’s Palace. I dined at the inn, in the room which had just been occupied by Countess Samoilova; it was still in a complete state of disarray. Is that niece of Princess Bagration, another victim of time’s injuries, still as lovely as she was in Rome in 1829, when she sang so beautifully at my concerts? What breeze blew this flower once more beneath my footsteps? What breath disturbs that cloud? Daughter of the North, you delight in life; hasten: the melodies that charmed you are already fading; your days are shorter than the Polar day.

In the hotel register I found the name of my noble friend, the Comte de La Ferronays, returning from Prague to Naples while I was journeying from Padua to Prague. The Comte de La Ferronays, my compatriot twice over since he is both a Breton and from Saint Malo, entwined his political destiny with mine: he was ambassador to St Petersburg when I was Foreign Minister in Paris; he occupied the latter role, when I became an ambassador under his direction. Sent to Rome, I gave in my resignation on the advent of Polignac’s ministry, and La Ferronays inherited my embassy. Monsieur de Blacas’ brother-in-law, he is as poor as the former is rich; he has left the Peerage and abandoned his diplomatic career since the July Revolution; everyone esteems him, and no one hates him, because his character is pure and his spirit temperate. In his latest negotiations in Prague, he allowed himself to be taken by surprise by Charles X, who is at the end of his life. Old people delight in secrecy, having nothing of value to display. Except for my old King, I think they should drown those who are no longer young, starting indeed with me, and a dozen of my friends.

From Udine, I took the Villach road: I travelled to Bohemia via Salzburg and Linz. Before attacking the Alps, I heard the sound of bells and saw an illuminated bell-tower in the plain. I interrogated the coachman with the help of a German from Strasbourg, working as an Italian-speaking guide in Venice, whom Hyacinthe had acquired to interpret Slavic in Prague. The celebrations I was enquiring about were due to a priest who had newly entered Holy Orders; he was to say his first Mass the following day. How many times would those bells, which today proclaimed the indissoluble union of man with God, call that man to the sanctuary and at what hour would those same bells ring out above his coffin?

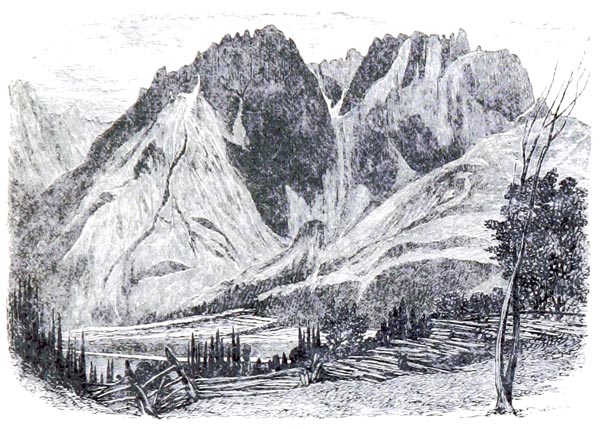

![The Eastern Alps [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Chateaubriand/interior_chateaubriand_memoirs_bk41chap1sec1.jpg)

‘The Eastern Alps [Detail]’

The Eastern Alps: Including the Bavarian highlands, Tyrol, Salzkammergut, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, and Istria. Handbook for travellers - Karl Baedeker (Firm) (p7, 1888)

Internet Archive Book Images

22nd of September.

I slept almost all night, to the roar of torrents, and woke at daybreak, on the 22nd, among the mountains. The valleys of Carinthia are pleasant, but lack character: the peasants do not dress in national costume; some of the women wear furs like Hungarians; others have white headdresses on the back of their heads, or a blue woollen bonnet padded at the sides, somewhere between an Ottoman turban and the buttoned hat of a Talapoin Buddhist monk.

I changed horses at Villach. On leaving the post-station, I followed a large valley beside the Drava, a new acquaintance for me: by dint of crossing rivers I will at last reach my final shore. Lander has just explored the Niger Delta; that resilient traveller has vanished into eternity at the very moment of ascertaining for us that the mysterious African river merges its waves with the Ocean. .

At the fall of night, we were almost halted at the village of Paternion: after greasing the wheels, a peasant tightened a wheel-nut in the wrong direction, with such force that it was impossible to free it. All the able men in the village, led by the blacksmith, failed in their attempts. A lad of fourteen or fifteen left the crowd then returned with a pair of pliers, pushed aside the workers, wound a brass wire round the nut, gripped it with his pliers, and turning it in the direction of the thread removed the nut with a minimum of effort: there was a universal vivat. Was the boy not a kind of Archimedes? The queen of a tribe of Eskimos, that woman who drew a chart of the Polar Regions for Captain Parry, watched his sailors welding pieces of iron on a forge with great attention, and through her intellect advanced the development of her race.

During the night of the 22nd and 23rd, I traversed a dense mass of mountains; they continued to loom in front of me as far as Salzburg: and yet those ramparts did not protect the Roman Empire. The author of the Essais, speaking of the Tyrol, says, with his usual lively imagination: ‘It was like a robe that we only saw folded, that, if it had been spread out, would have formed a large country.’ The hills among which I wound were like rock-falls from the higher chain, which, if covering a vast terrain would have created little Alps displaying various features of the great ones.

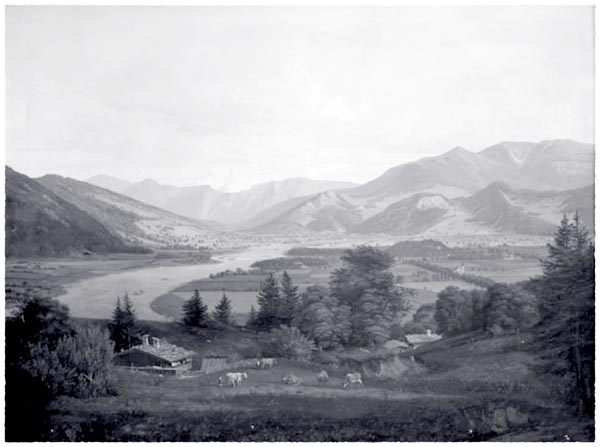

![Panorama of the Smittenhoe [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Chateaubriand/interior_chateaubriand_memoirs_bk41chap1sec1b.jpg)

‘Panorama of the Smittenhoe [Detail]’

The Eastern Alps: Including the Bavarian highlands, Tyrol, Salzkammergut, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, and Istria. Handbook for travellers - Karl Baedeker (Firm) (p180, 1888)

Internet Archive Book Images

Cascades descended all about us, leaping over their stony beds, like Pyrenean mountain streams. The road passed through gorges barely navigable by a calash. Near Gemünd, water-driven forges joined the noise of their hammers to that of the sluices; streams of sparks escaped from their chimneys into the black pine forests and the night.

At each breath of the bellows over the coals, the exposed roofs of the building were suddenly illuminated, like the cupola of St Peter’s Rome on a feast day. In the Karch range, three pairs of oxen were added to our team of horses. Our long train looked like a mobile bridge over the flowing torrents and inundated ravines: the Tauern range opposite was cloaked in snow.

On the 23rd, at nine in the morning, I arrived in the pretty hamlet of St Michael, at the end of a valley. Tall and lovely daughters of Austria served me a proper breakfast in a little two-windowed room looking out on meadows and the village church. The cemetery, surrounding the church, was only separated from me by a rustic courtyard. Wooden crosses, set in a semicircle, from which were hung holy water stoups, rose from the lawn with its old tombs: five graves with no grass growing on them indicated five new sleepers. A few ditches, like the beds in a vegetable garden were decorated with marigolds in full flower; wagtails chased grasshoppers in this garden of the dead. A very old crippled woman, leaning on her crutch, crossed the cemetery and brought back a broken cross; perhaps the law allowed her to take the cross for her own grave; dead wood, in the forests, belongs to whoever gathers it.

‘There do inglorious poets sleep unknown,

Mute orators, conquerors without a throne.’

Would not the child in Prague sleep more soundly here, without his crown, than in the chamber of the Louvre where his father’s body was laid?

My solitary breakfast, in the company of those travellers lying at rest beneath my window, would have been to my taste if a recent death had not troubled me: I had heard cries from the bird served up for my meal. Poor chick! She had been so happy five minutes before my arrival! She had pecked about amongst the grass, vegetables and flowers; she had scurried about among the flocks of goats down from the mountain; this evening she would have slept at sunset, still young enough to rest beneath her mother’s wing.

The horses hitched, I climbed into my calash again, surrounded by the girls, and accompanied by the lads, from the inn; they seemed happy to have met me, though they had no idea who I was and would never see me again: they sent so many blessings after me! I never weary of this Germanic cordiality. Every peasant you meet raises his hat to you and wishes you a hundred fine things: in France they do not even salute the dead; liberty and equality are renowned for their insolence; there is no empathy between individuals; to envy whoever travels with a modicum of style, and be ready, arms akimbo, to fight anyone wearing a new frock-coat or a clean shirt, that is the characteristic mark of our national freedom: of course we spend our days in antechambers suffering rebuffs from some upstart peasant. That does not inhibit our powers of intellect, or prevent us conquering weapons in hand; but ways of life are not created a priori: we have been a great military nation for eight centuries; fifty years cannot alter that; we cannot lose the true love of liberty. As soon as we pause for a moment under some transitory government, the old monarchy springs again from its stock, the old spirit of France reappears: we are courtiers and soldiers, nothing more.

Book XLI: Chapter 2: The Tauern Pass – A Cemetery – Atala: how altered – Sunrise – Salzburg – A military review – Happy peasants – Vöcklabruck – Plancoët and my aunt – Night – German towns and Italian towns – Linz

23rd and 24th of September 1833.

BkXLI:Chap2:Sec1

The final range of mountains enclosing the province of Salzburg overlooks arable land. The Tauern possesses glaciers; its plateau resembles the Alpine plateaux, particularly that of Saint Gothard. On this plateau covered with reddish frozen moss, there is a Calvary: an ever-present consolation, an eternal sanctuary for the unfortunate. Round this Calvary are interred the victims who have perished among the snows.

‘Lienz Dolomites’

The Dolomite Mountains. Excursions Through Tyrol, Carinthia, Carniola, & Friuli in 1861, 1862, & 1863 - George Cheetham Churchill (p65, 1864)

The British Library

What were the hopes of such travellers passing this place like me when the storm surprised them? Who were they? Who wept for them? How can they rest there, so far from their relatives, their country, hearing each winter the roaring of the tempests whose blast tears them from the earth? Yet they sleep at the foot of the Cross; Christ, their sole companion, their special friend, fixed to the sacred tree, leans towards them, coated by the same frost that whitens their graves: in the celestial house he shall present them to his Father and warm them again at his breast.

The descent from the Tauern is lengthy, difficult, and perilous; I was charmed by it: it recalled, now by its waterfalls and wooden bridges, now by the narrowing of its chasm, the valley of the Pont-d’Espagne at Cauterets, or the slope of the Simplon at Domo d’Ossola; though it did not lead to Granada or Naples. There are no gleaming lakes or orange groves below: it is idle taking so much trouble merely to reach potato fields.

At the post-station, half-way down, I found myself among family at the inn: the adventures of Atala, in six engravings, decorated the wall. My daughter never suspected I would pass by, and I never expected to see so dear an object beside a torrent called, I think, the Dragon. She was quite ugly, quite old, quite altered, poor Atala! On her head were tall feathers and round her lower body a short tight skirt, in the style of the female savages at the Théâtre de la Gaîté. Vanity silvers everything; I swelled with pride before my creation, in the depths of Carinthia, as Cardinal Mazarin did before the paintings in his gallery. I had a yearning to say to my host: ‘I created her!’ I had to be torn away from my first-born, less difficult a process however than on that island in the Ohio.

Till Werfen nothing caught my attention, except perhaps the manner in which they dry the late harvest: they plant fifteen to twenty foot long poles in the ground; they wind the cut hay, without crushing it too much, around these poles; it dries there while darkening. At a distance, the pillars look exactly like cypress trees or trophies planted in memory of the flowers cut in these valleys.

‘District of Salzburg, 1834’

Johann Mohr (Danish, 1808 - 1843)

Statens Museum for Kuntz

24th of September, Tuesday.

Germany chose to take her revenge for my ill humour with her. In the plain of Salzburg, on the morning of the 24th, the sun appeared east of the mountains I was leaving behind me; some rocky peaks in the west were gently illuminated by its first glow. Darkness still covered the plain, which was half green, half ploughed, and from which a mist rose, like the steam of human sweat. Salzburg Castle, elevated on the summit of the little hill which overlooks the city, inlaid its white relief on the blue sky. As the sun rose, from the heart of the fresh exhalation of dew emerged avenues, clumps of trees, red brick houses, cottages rendered with brilliant whitewash, and towers from the Middle Ages scarred and pierced, time’s aged champions, wounded in head and chest, sole survivors on the battlefield of the centuries. The light over the landscape was the violet colour of autumn crocuses, which open at this time and with which the fields along the Saltz were sown. Flocks of crows, leaving the ivy and clefts of the ruins, descended to the fallows; their glistening wings were glazed with rose in the sheen of dawn.

‘Tuesday; The Castle of Salzburg from the Noontime Side’

Ferdinand Olivier (German, 1785 - 1841)

The National Gallery - Open Access

It was the feast day of Saint Rupert the patron saint of Salzburg. The farmers marched, dressed in village fashion: their blond hair and snowy brows were covered by a kind of gilded helmet, which suits the Germans well. As I passed through the city, which was clean and lovely, I saw two or three thousand infantrymen in a meadow; a general, accompanied by his staff, was reviewing them. The white ranks criss-crossing the green grass, the weapons glinting in the rising sun, were a sight worthy of those people described or rather sung by Tacitus: the Teuton Mars was offering a sacrifice to Aurora. What were my Venetian gondoliers doing at that moment? They were rejoicing like swallows in the rebirth of day from night, and preparing to skim the surface of the water; then the joys of night would return, barcarolles, and the business of love. To every nation its fate: power to some; pleasure to others: the Alps separate them.

From Salzburg to Linz is fertile country, the horizon on the right indented with mountains. Tall clumps of beech and pine, oases rustic and identical, surrounded by varied and expert cultivation. Flocks of various kinds, hamlets, churches, oratories, and crosses adorned and animated the route.

Having emerged from the glow of Saint Rupert’s feast day (festivals among men are brief and do not extend far), we found everyone in the fields, occupied with the autumn sowing or harvesting potatoes. Their rural population was better dressed, more polite, and seemed happier then ours. Let us not disturb the order, peace, and simple virtues they enjoy under the pretext of substituting political benefits for them which are not conceived or felt in the same way by all. The whole of humanity understands the joys of the hearth, family affections, life’s abundance, the simplicity of feeling and religion.

The Frenchman, so in love with woman, easily ignores her, lost as he is in a multitude of cares and labours; the German cannot live without his companion; he employs her and takes her with him everywhere, to war as to work, to the feast as to the funeral.

In Germany, even the beasts of the field have the temperate character of their reasonable masters. When you travel, the features of the animals prove interesting to an observer. You can judge the habits and passions of a region’s inhabitants by the gentleness or viciousness, the wildness or tameness, the air of contentment or sadness of that part of the animal kingdom that God has given into our hands.

An accident to the calash obliged me to stop at Vöcklabruck. Roaming round the inn a back door gave me access to a canal. Beyond it were meadows striped with pieces of unbleached cloth. A river curving beneath wooded hills, served these meadows as a belt. Something reminded me of the village of Plancoët, where happiness was granted me in my infancy. Shades of my old relatives, I did not expect you on those shores! You seem nearer to me because I am nearer to the grave, your refuge; we shall meet again there. My dear aunt, do you still sing, on the banks of Lethe, your song of the Sparrow-Hawk and the Warbler? Have you met the fickle Trémigon among the dead, as Dido encountered Aeneas in the land of spirits?

I left Vöcklabruck as the day ended; the sun entrusted me to his sister’s hands: a double glow of an indefinable colour and fluidity. Soon the moon reigned alone: she wished to renew our conversation of the Haselbach forest; but I was not in accord with her. I preferred Venus, who rose at two a.m. on the 25th; she was as lovely as she was when I contemplated her and entreated her in those dawns over the waters of Greece.

Leaving many unknown groves, streams, and valleys, to right and left, I passed through Lambach, Wels, and Neübau, new little towns with unroofed houses, in the Italian style. Music was being played in one of these houses; young women were at the windows: things would not have been thus in the days of Maroboduus.

The streets in German towns are wide, aligned like the tents in camp or the ranks of a battalion; the market places are vast, the parade grounds spacious: there is a lack of sunlight, and everything takes place in public.

In Italian towns, the streets are narrow and tortuous, the market places tiny, the parade grounds constricted: there is a lack of shade and everything takes place in private.

At Linz, my passport was stamped without problem.

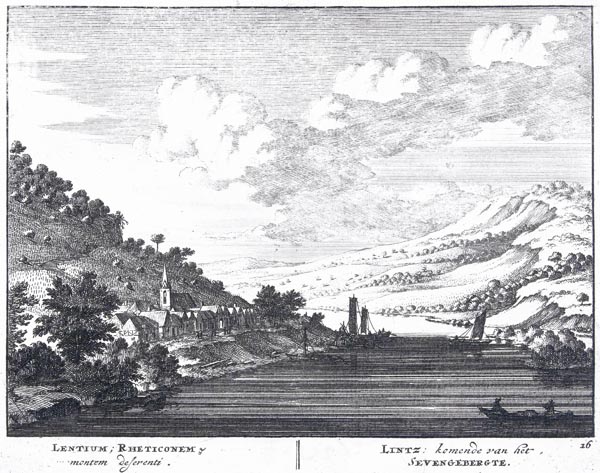

‘Linz on the Rhine’

Jan van Call (I), 1694 - 1697

The Rijksmuseum

Book XLI: Chapter 3: The Danube – Waldmünchen – Woods – Combourg – Lucile – Travellers – Prague

25th and 26th of September 1833.

BkXLI:Chap3:Sec1

I crossed the Danube at three in the morning: I had said to it in summer what I no longer found to say to it in autumn; they were no longer the same waters, nor were my days the same. I left my excellent village of Waldmünchen with its herds of pigs, the swine-herd Eumaeus, and the peasant girl who gazed at me over her father’s shoulder, far to the left. The ditch of corpses in its cemetery would have been filled in; the dead eaten by thousands of worms for having had the honour of being human.

Monsieur and Madame de Bauffremont, having arrived at Linz, were a few hours ahead of me; they were themselves preceded by several royalists: bearing messages of peace, they believed Madame to be travelling tranquilly behind them, while I was following them like Discord, with news of war.

Princesse de Bauffremont, née Montmorency, was going to Bustehrad to pay her compliments to the Kings of France nés Bourbons: nothing could be more natural.

On the 25th, at nightfall, I entered woodland. The crows were calling in the air; dense flocks of them wheeled above the trees whose summits they were preparing to adorn. There, I returned to my early youth: I saw again the crows in the mall at Combourg; I thought I was back again with my family in the old castle: O memories, you pass through the heart like a sword! O, my Lucile, so many years separate us! Now a host of my days has passed, and, in vanishing, allows me to see your image more clearly.

I reached Tabor at night: its square, surrounded by arcades, seemed immense; but moonlight is deceptive.

On the morning of the 26th, fog covered us in its boundless solitude. About six, I seemed to be passing between two lakes. I was only a few miles from Prague.

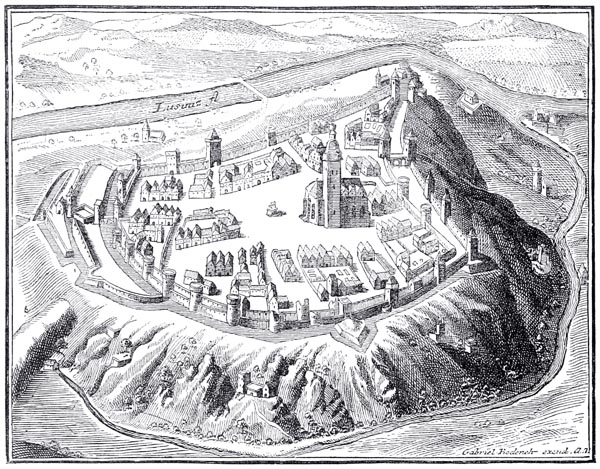

‘Tabor’

Pictures from Bohemia, drawn with Pen and Pencil, etc - James Baker (p122, 1894)

The British Library

The fog lifted. The approach to the city by the Linz road is more interesting than that from Regensberg; the countryside is less flat. You see villages, and chateaux with plantations and ponds. I met a woman, a pious and resigned figure, overwhelmed by the weight of an enormous basket; two old fruiterers laying out their apples beside a ditch; a girl and her lad sitting on the grass, the young man smoking, the girl happy, next to her friend by day, in his arms at night; children playing at the cottage door with their cats or driving the geese to the common; and turkeys in a cage off to Prague like me for Henri V’s coming of age; then a shepherd sounding his horn, while Hyacinthe, Baptiste, the translator from Venice, and His Excellency, jolted along in our patched-up calash: such are life’s destinies. I would not give a sou for the best of them.

Bohemia offered me nothing new; my thoughts were fixed on Prague.

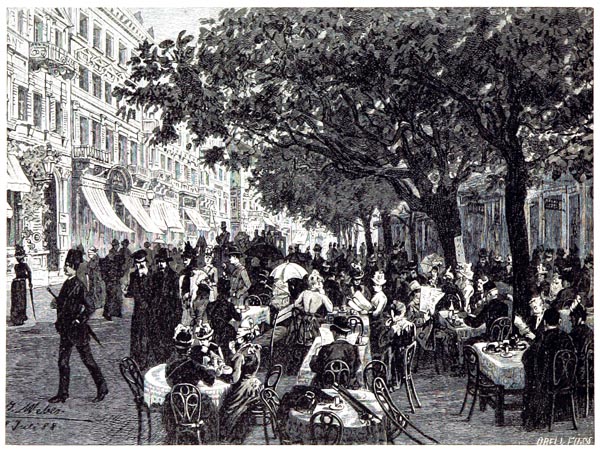

‘Near Prague’

Wenceslaus Hollar (1635)

National Gallery of Art - Open Access

I entered Prague on the 26th at four in the afternoon. I stopped at the Hôtel des Bains. I did not see the young Saxon servant girl; she had returned to Dresden to soothe Raphael’s exiled paintings with the songs of Italy.

Prague, the 29th of September 1833.

Two days after my arrival in Prague (the 28th) I sent Hyacinthe with a letter to Madame la Duchesse de Berry, whom according to my calculations he should find in Trieste. The letter to the Princess said: ‘that I had found the Royal Family leaving for Leoben, that young Frenchmen were arriving for the coming-of-age of Henri V and that their King would evade them, that I had seen Madame la Dauphine, and that she had invited me to go at once to Bustehrad where Charles X might shortly be found; that I had not seen Mademoiselle because she was a little indisposed, that they had allowed me into her room where the shutters were closed, and that she had held out her burning hand to me in the darkness while begging me to save them all: that I has gone to Bustehrad, that I had seen Monsieur de Blacas and talked with him about the declaration of Henri V’s majority; that entering the King’s room I had found him asleep, and that having then presented Madame la Duchesse de Berry’s letter to him he had seemed quite hostile to my august client; that however the little decree I had drafted regarding the majority seemed to please him.’

The letter ended with this paragraph:

‘Now Madame, I must not hide from you that there is much wrong here. Our enemies would smile if they could see us debating a king without a kingdom, a sceptre which is only a stick on which we lean, during the pilgrimage, which will probably be lengthy, of our exile. Your son’s education is full of deficiencies, and I see no chance of them being remedied. I am returning to the poor folk whom Madame de Chateaubriand nurtures; there, I will always be at your command. If ever you take sole charge of Henri, and continue to believe that precious charge might be placed in my hands, I would be as pleased as I would be honoured to devote the remainder of my life to him, but I could not accept so fearful a responsibility except on condition of being, under your counsel, entirely free in my decisions and thoughts, and located on independent territory, beyond the circle of absolute monarchy.’

With the letter was enclosed this copy of my draft declaration of majority:

‘We, Henri V by name, having arrived at the age at which the laws of the kingdom have fixed the royal majority, wish the first action of that majority to be a solemn protest against the usurpation of the throne by Louis-Philippe, Duc d’Orléans. In consequence, and on the advice of our counsellors, we have issued this decree to maintain our rights and those of the French: given this thirtieth day of September, in the year of grace eighteen thirty three.’

Book XLI: Chapter 4: Madame de Gontaut – Young France – Madame la Dauphine – Journey to Bustehrad

Prague, the 30th of September 1833.

BkXLI:Chap4:Sec1

My letter to Madame la Duchesse de Berry indicated the broad facts but did not enter into detail.

When I saw Madame de Gontaut amidst half-filled cases and open trunks, she threw herself on my neck, sobbing: ‘Save me! Save us!’ – ‘Save you: from what, Madame? I have just arrived. I know nothing.’ The Hradschin was deserted; one would have thought these the days of July and the abandonment of the Tuileries, as if revolution dogged the steps of the exiled race.

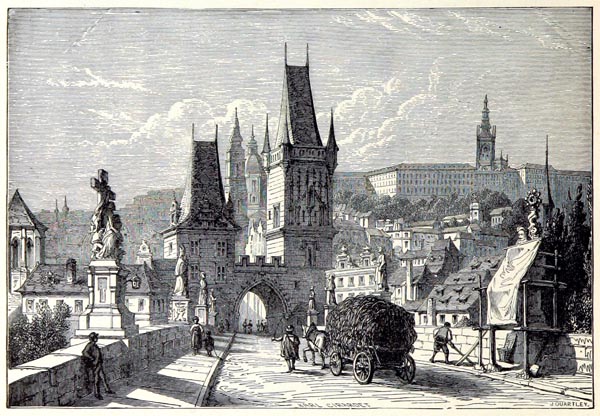

‘View from Carls Bridge, Prague’

Pictures from Bohemia, drawn with Pen and Pencil, etc - James Baker (p82, 1894)

The British Library

Various young men had come to congratulate Henri on his majority; several were under threat of death-warrants; a few, wounded in the Vendée, almost all of them poverty-stricken, had been obliged to club together even to carry their expression of loyalty to Prague. An immediate order had closed the Bohemian frontier to them. Those who reached Bustehrad were only received after much difficulty; etiquette barred their passage, as the Gentlemen of the Chamber at Saint-Cloud had defended the door of Charles X’s room while the Revolution entered through the window. These young men were told that the King had gone, that he would not be in Prague on the 29th. Horses were in readiness, the Royal Family’s luggage was packed. If the travellers did at last obtain permission to utter hasty congratulations, they were heard with fear. The loyal group were not even offered a glass of water; no one acknowledged them at the table of the orphan they had come so far to see; they were reduced to drinking Henri’s health at an inn. The family fled before a handful of men from the Vendée, as they scattered before a hundred heroes of July.

And what was the pretext for this flight? They were going to meet Madame la Duchesse de Berry; they had fixed a meeting with the Princess on the highroad to allow her to see her daughter and son surreptitiously. Was she not the guilty one? She was idly insisting on Henri claiming his title. To express the situation in its simplest form, they displayed to the eyes of Austria and France (if France even noticed these nonentities) a spectacle that rendered the Legitimacy, already so far gone, a grief to its friends and an object of calumny to its enemies.

Madame la Dauphine understood the deficiencies in Henri V’s education, and it drove her to tears, as dew falls from heaven at night. The brief audience which she accorded me did not allow her to speak of my letter from Paris of the 30th of June: she looked at me in a moving manner.

Given the very severity of Providence, any means of rescue seemed lost: exile had separated the orphan from what threatened to ruin him at the Tuileries; in the school of adversity, he might have been raised under the direction of men of the new social order, fit for the instruction of a new king. At present, instead of employing such masters, far from improving Henri V’s education they were rendering it worse through the parochialism produced by the constraint of family life: on winter evenings, old men, poking through the centuries at a corner of the hearth, teach the boy about days on which the sun no longer shines; they transform the chronicles of Saint-Denis into fairy stories; the two leading barons of the modern age, Liberty and Equality, would know better how to force Henri Lack-land to grant a Magna Carta.

The Dauphine committed me to making the trip to Bustehrad. Messieurs Dufougerais and Nugent accompanied me in an embassy to Charles X on the very evening of my arrival in Prague. At the head of the deputation were the young men, they were off to complete the negotiations already begun on the issue of being presented. The former, implicated in my trial at the Assize Court, had pleaded his case in a spirited manner; the latter had just undergone an eight-month prison sentence for editing a Royalist paper. The author of Le Génie du Christianisme thus had the honour of going to see the Very Christian King, seated in a roomy calash between the editor of La Mode and the editor of Le Revenant.

Book XLI: Chapter 5: Bustehrad – Charles X’s sleep – Henri V – The young men’s reception

Prague, the 30th of September 1833.

BkXLI:Chap5:Sec1

Bustehrad is a large villa belonging to the Grand-Duke of Tuscany, about fifteen miles from Prague, on the road to Carlsbad. The Austrian princes have patrimonial estates in their own country and beyond the Alps are only owners for life: they hold Italy on lease. You reach Bustehrad through a triple alley of apple trees. The villa is not showy; with its outbuildings, it resembles a large tenant farm, and in the midst of a bare plain overlooks a hamlet consisting of young trees and a tower. The interior of the building is an Italian aberration on the 50th parallel: vast rooms without fireplaces or stoves. The apartments are sadly enriched by the spoils of Holyrood. James II’s Palace, refurnished by Charles X, provided Bustehrad after the move with its armchairs and carpets.

The King had a fever and was in bed when we arrived at Bustehrad on the 26th at eight in the evening. Monsieur de Blacas showed me into Charles X’s room, as I explained to the Duchesse de Berry. A little lamp burnt on the mantelpiece; in the shadowy silence I heard only the noble respiration of the thirty-fifth successor to Hugh Capet. O my aged King! Your sleep was painful; time and adversity, those nightmare burdens, were seated on your chest. A young man approaches the bed of his young wife with less love than the respect I felt in walking with furtive steps towards your solitary couch. At least I was not an evil dream like that which woke you to go to your son’s deathbed! I addressed these words to you in my mind which I would have been unable to pronounce aloud without dissolving in tears: ‘Heaven guard you from all future ill! Sleep in peace through these nights that verge on your last sleep! Too long your vigils have been those of grief. May this bed of exile lose its harshness awaiting God’s visitation! He alone can make this foreign soil lie lightly on your bones.’

Yes, I would have given all the blood in my body, joyfully, to render the Legitimacy credible to France. I imagined that it might be for the old monarchy as it was for Aaron’s dry rod; taken from the Temple in Jerusalem, it grew green and bore almond blossom, a symbol of the renewal of the covenant. I have not tried to stifle my regrets, or hold back the tears with which I sought to wash away the last traces of royal suffering. The feelings I experience, of various kinds, on the subject of these same people, witness to the sincerity with which these Memoirs are written. Charles X, the man moved me, while the monarch wounded me: I display those differing impressions as they succeed one another, without seeking to reconcile them.

On the 27th of September, after Charles X had received me in the morning at his bedside, Henri V summoned me: I had not asked to see him. I said a few serious words to him on the subject of his coming of age and the loyal Frenchmen who had offered him golden spurs in their ardour.

For the rest, it is impossible to be treated better than I was. My arrival had sounded the alarm; they feared my account of my trip to Paris. For me then every attention; the others were neglected. My companions, scattered, dying of hunger and thirst, wandered the corridors, stairs, and courtyards of the château, amidst the panicking masters of the house and their preparations for escape. There were oaths and outbursts of laughter.

The Austrian guard marvelled at these moustachioed individuals in bourgeois dress; they suspected them of being French soldiers in disguise, who were about to take Bohemia by surprise.

While the storm went on outside, inside Charles X said to me: ‘I am occupied with editing the decree regarding my government in Paris. You will have Monsieur de Villèle as a colleague, as you requested, the Marquis de Latour-Maubourg, and the Chancellor.’

I thanked the King for his kindness, while admiring the delusions of this world. While society collapsed, while monarchies ended, while the face of the earth changed, Charles in Prague established a government for France on the advice of his ruling council. Let us not scoff too much: who of us does not have his illusions? Who of us does not nourish nascent hopes? Who of us does not establish their government in petto on the advice of their ruling passions? Mockery would ill befit me, the man of dreams. Are not these Memoirs that I scribble in transit my government on the advice of my ruling vanity? Do I not think to speak quite seriously of the future, which is as little under my control as France was under Charles X’s command?

Cardinal Latil, not wishing to get into a quarrel, had gone to spend a few days with the Duc de Rohan. Monsieur de Foresta passed by mysteriously, a portfolio under his arm; Madame de Bouillé made me a profound reverence, like a follower, with lowered eyes which wished to gaze upwards beneath their eyelids; Monsieur Lavilatte was waiting to take his leave; there was no sight of Monsieur Barrande, who hoped vainly to return to grace and hung about in some corner of Prague.

I went to pay court to the Dauphin. Our conversation was brief:

‘How is Monseigneur, at Bustehrad?’

‘– Growing old.’

‘– As is everyone, Monseigneur.’

‘– And your wife?’

‘– Monseigneur, she has the toothache.’

‘– An abscess?’

‘– No, Monseigneur: age.’

‘– You dine with the King? We shall meet again there.’

And we quit each other.

Book XLI: Chapter 6: The peasant-girl and the ladder – Dinner at Bustehrad – Madame de Narbonne – Henri V – A game of Whist – Charles X – My incredulity regarding the declaration of majority – A reading fom the newspaper – Scene with the young men in Prague – I leave for France – Bustehrad by night

Prague, the 28th and 29th of September 1833.

BkXLI:Chap6:Sec1

I found myself at three with time on my hands: dinner was at six. Not knowing what to do with myself, I walked through alleys of apple trees worthy of Normandy. In a good year the harvest of these false-oranges is worth eighteen thousand francs. The fruit is exported to England. They make no cider from it, the beer monopoly in Bohemia opposing it. According to Tacitus, the Germans had words to express spring, summer and winter; they had no word for autumn, whose name and produce they ignored: nomen ac bona ignorantur. Since Tacitus’ time, Pomona has arrived among them.

Feeling tired, I perched on the rungs of a ladder leaning against the trunk of an apple-tree. There, I was in direct firing line from the château of Bustehrad, and a sling-shot’s throw from the council chamber. Gazing at the roof which was sheltering three generations of the monarchy, I recalled an Arab chant (maoual): ‘Here we have seen the stars we loved to see, beneath the skies of home, flee beneath the horizon.’

Filled with these mournful thoughts, I slept. A sweet voice woke me. A Bohemian peasant girl had come to gather apples; puffing out her chest and raising her head, she gave me a Slavic greeting with the smile of a queen: I almost fell from my perch: I said to her in French: ‘You are very beautiful; I thank you!’ I saw by her manner she had understood me: apples always count for something in my encounters with Bohemian girls. I scrambled down from my ladder like one of those condemned men of feudal times delivered by the presence of a young girl. Thinking of Normandy, Dieppe, Fervaques, and the sea, I took to the paths of this Trianon of Charles X’s old-age.

At table were: the Prince and Princess de Bauffremont, the Duke and Duchess de Narbonne, Monsieur de Blacas, Monsieur Damas, Monsieur O’Hegerty, myself, Monsieur le Dauphin, and Henri V: I would have preferred the young men there rather than myself. Charles X did not dine; he was taking care of himself, in order to be fit to leave the next day. The banquet was noisy thanks to the young Prince’s chatter: he never left off talking about his horse-riding, his horse, his horse’s adventures on grass, his horse’s labouring on plough-land. The conversation was perfectly natural and yet I was bothered; I preferred our former discussions about travel and history.

The king arrived and spoke to me. He complimented me once more on my draft note on the majority; it pleased him because, leaving aside the matter of the abdications as a fait accompli, it required only Henri’s signature, and opened no old wounds. According to Charles X, the declaration would be sent from Vienna to Monsieur Pastoret before my return to France; I bowed with a smile of incredulity, His Majesty, after having tapped me on the shoulder as was his wont said: ‘Chateaubriand, where are you off to now?’ – ‘To Paris sire, foolishly.’ – ‘No, No, not foolishly,’ the King continued, seeking with a kind of anxiety to plumb my thoughts.

The newspapers were brought; the Dauphin seized the English gazettes: suddenly, in the midst of a profound silence, he translated this passage from the Times in a loud voice; ‘Baron de **** is here, four feet tall, aged sixty-six, and as sprightly as he was fifty years ago.’ And Monseigneur fell silent.

The King withdrew; Monsieur de Blacas said to me: ‘You should come to Leoben with us.’ The proposal was not serious. Besides I had no wish to be involved in family affairs; I wished neither to divide relatives, nor become mixed up in risky reconciliations. Whenever I glimpse an opportunity of becoming the favourite of some power or another, I shudder; post-horses hardly seemed swift enough to carry away my potential honours. The shadow of Good-Fortune made me tremble, as Richard’s horse did the Saracens.

Next day, the 28th, I shut myself up in the Hôtel des Bains and wrote my despatch to MADAME. Hyacinthe left with the despatch that same evening.

On the 29th I went to see Count and Countess Choteck; I found them overcome by the hubbub of Charles X’s court. The Grand Burgrave had ended up sending couriers to countermand the instructions halting the young men at the frontier. Moreover, those one saw in the streets of Prague had lost nothing of their French character; a Legitimist and a Republican are, apart from their politics, one and the same: there was noise, tomfoolery, laughter! The visitors came to my hotel to recount their adventures. M*** had visited Frankfurt with a German guide, who was delighted with the French; M*** asked him why, and the guide replied: ‘Die Vrench are come to Frankfurt; they drink der vine and make love to die pretty vives of die pourgeois. General Auchereau impose forty-vun millions of tax on der city of Frankfurt.’ Those are the reasons why they like the French so much in Frankfurt.

A grand luncheon is served in my inn; the rich pay for the poor. Beside the Moldau they drink Champagne to Henri V’s health, who takes to the road with his grandfather for fear of hearing the toasts to his crown. At eight, my business done, I climb into my carriage, hoping never to return to Bohemia.

They say Charles X had the intention of making a religious retreat: there were family precedents for such a plan. Richer, a monk of Senones, and Geoffroy de Beaulieu, Saint Louis’ confessor, reported that the great man had thought of shutting himself in a cloister when his son was old enough to replace him on the throne. Christine de Pisan said of Charles V: ‘The wise king decided that if he lived until his son the Dauphin was of an age to wear the crown he would hand over the kingdom to him.and become a priest.’ If such princes had abandoned the sceptre, they would have been truly missed as advisors to their sons; yet, by remaining kings, did they create successors worthy of themselves? What was Philip the Bold compared with Saint Louis? All Charles V’s wisdom turned to folly in his heir.

I passed Bustehrad at ten at night, riding through a silent countryside, vividly lit by the moon. I saw the vague mass of the villa, the hamlet and the ruin that the Dauphin inhabited: the rest of the Royal Family had left. A profound feeling of isolation gripped me; that man (as I have said already) has his virtues: a political moderate, he nourishes few prejudices; he has only a drop of Saint Louis’ blood, but that he does have; his probity is unparalleled, his word as inviolable as the word of God. Naturally courageous, his filial piety compromised him at Rambouillet. Brave and humane, in Spain, he had the glory to return a relative to that throne while failing to preserve his own. Louis-Antoine, after the July Days, dreamed of seeking refuge in Andalusia: Ferdinand indeed refused him. The husband of Louis XVI’s daughter languished in a Bohemian village; a dog, whose yelp I heard, was the prince’s only guard: Cerberus barked thus at the shades in the regions of death, silence and the night.

I have never been able to revisit my paternal hearth during a long life; I have been unable to settle in Rome, where I wished to die; the many hundreds of miles I have travelled, including my first trip to Bohemia, would have taken me to the finest sites of Greece, Italy and Spain. I have devoured those miles and consumed my last days in order to return to this grey and frozen land: how have I offended Heaven?

Book XLI: Chapter 7: A meeting at Schlau – An empty Carlsbad – Hollfeld – Bamberg: the librarian and the young lady – My various Saint Francis’ Days – Proofs of religion – France

From the 29th of September to the 6th of October, 1833.

BkXLI:Chap7:Sec1

A carriage was changing horses, at Schlau, at midnight, in front of the post-station. Hearing French spoken, I put my head out of the calash and said: ‘Gentlemen, are you going to Prague? You will not find Charles X there, he has left with Henri V.’ I gave my name, ‘What, he’s left?’ cried several voices together. ‘Go on, coachman, go on!’

My eight compatriots, stopped initially at Eger, had obtained permission to continue their journey, but with a police officer accompanying them. This meeting in 1833 with a band of followers of throne and altar, despatched by the French Legitimacy, under the escort of a sergeant, was strange! In 1822, in Verona, I had seen cages of Carbonari accompanied by gendarmes. What then do sovereigns want? Whom do they recognize as friends? Do they fear too great a crowd of their supporters? Instead of being moved by their loyalty, they treat the men devoted to their crown as propagandists and revolutionaries.

The postmaster at Schlau had invented a new accordion: he sold me one; all night I worked the wheeze-box, whose sound took from me all memory of the world.

Carlsbad (I passed through on the 30th of September) was deserted; an opera house after the music has ceased. At Eger I found the customs man again, who brought me down from where I was: in the June moonlight with a lady of the Roman Campagna.

‘At the Alteweise, Carlsbad’

Pictures from Bohemia, drawn with Pen and Pencil, etc - James Baker (p180, 1894)

The British Library

At Hollfeld, more swifts but no little basket-carrier; I was sad. Such is my nature: I idealise real people and personify dreams, displacing mind and matter. A little girl and a bird now swell the crowd of beings I create, with which my imagination is populated, like those motes that dance in a ray of sunlight. Forgive me, for talking about myself, I realised too late.

Here is Bamberg. Padua made me recall Livy: at Bamberg, Father Horrion discovered the first part of the Roman historian’s thirty-third book. While I ate supper in the country of Joachim Camerarius, and Clavius, the town librarian came to welcome me drawn by my fame, the greatest in the world, according to him which warmed the marrow of my bones. A Bavarian general followed. At the inn-door, a crowd surrounded me as I regained my carriage. A young woman was standing on a milestone, like that Sainte-Beuve who watched the Duc de Guise go by. She smiled: ‘Are you mocking me?’ I asked her. – ‘No,’ she replied in French, with a German accent, ‘it’s because I’m so pleased!’

From the 1st to the 4th of October, I revisited the places I had seen three months previously. On the 4th I reached the border of France. Saint Francis’ day is, each year, one on which I examine my conscience. I turn my gaze on the past; I ask myself where I was, and what I was doing on each preceding anniversary. This year, 1833, Saint Francis’ Day found me wandering, subject to my vagabond destiny. I saw a cross beside the road; it rose from a clump of trees which allowed a few dead leaves to fall, in silence, over the crucified Son of God. Twenty-seven years earlier, I had passed Saint Francis Day at the foot of the real Golgotha.

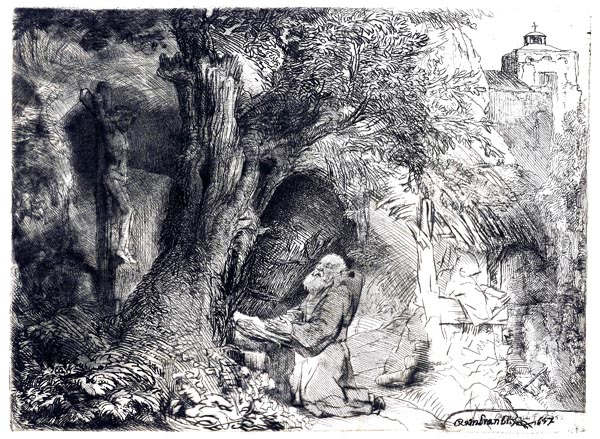

My patron saint also visited the Holy Tomb. Francis of Assisi, founder of the mendicant Order, by creating that institution, took a considerable step for the Gospel, which has not been sufficiently remarked upon: he brought the reality of the people into religion; by dressing poverty in a monk’s robe, he drove the world towards charity, he raised the beggar in the eyes of the wealthy, and by means of a proletarian Christian militia established a model of the brotherhood of Man that Jesus preached, a brotherhood which will be accomplished by that as yet undeveloped Christian politics without which there will never be complete liberty and justice on this earth.

My patron saint even extended his fraternal tenderness to the animals over which he seemed to have gained that ascendancy, through his innocence, that Man exercised before The Fall: he spoke to them as if they could understand him; he called them his brothers and sisters. Near Bavano, as he passed by, a multitude of birds gathered around him; he welcomed them and said: ‘My winged brothers, love and praise God, for he clothed you in feathers and gave you the power to fly through the sky.’ The birds of Lake Rieti followed him. He was joyful when he met flocks of sheep; he had great compassion for them: ‘My sisters,’ he said, ‘come to me.’ He sometimes bought, for the price of his clothes, a ewe being led to the slaughter; he recalled that gentlest of lambs, illius memor agni mitissimi, crucified for Man’s salvation. A cicada lived on a fig-tree branch near his door in the Portiuncula; he called to it; it came to sit on his hand and he said: ‘Sister Cicada, sing of God your creator.’ He did the same with a nightingale and was vanquished in song by the bird he blessed, which flew away after its victory. He was forced to take little wild creatures that ran to him and sought shelter at his breast, back to the woods. When he wanted to pray in the morning, he ordered the swallows to be silent, and they obeyed. A young man went to sell turtledoves in Siena; the servant of God begged the lad to hand them over to him, so that no one might kill those birds, symbols in Scripture of innocence and inoffensiveness. The saint carried them to his monastery of Ravacciano; he planted his stick at the door of the monastery; the stick was transformed into a tall green oak tree; the saint let the turtledoves go and commanded them to build their nest there, which they did for many years.

‘Saint Francis beneath a Tree, Praying’

Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn, 1657

The Rijksmuseum

Francis, dying, wished to leave the earth as nakedly as he had entered it; he asked that his bare corpse be interred in the place where criminals were executed, in imitation of Christ who was his example. He dictated a testament of the spirit; for he had nothing to leave his fellow-men but poverty and peace; a saintly woman placed him in the grave.

I have been endowed with poverty by my patron, love of the small and humble, and compassion for animals; but my barren stem will not become a green oak tree to protect them.

I ought to have been happy to have trodden the soil of France on my name day; but have I a homeland? In this country have I ever known a moment’s rest? On the 6th of October I re-entered my Infirmary. The gusty wind of St Francis’ Day still reigned. My trees, burgeoning shelter for the poor people gathered in by my wife, bent beneath my patron saint’s wrath. In the evening, through the elm branches on the boulevard, I watched the street-lights flickering, their half-extinguished flames wavering like the little lamp of my life.

End of Book XLI