François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXX: The Conclave, The Rome Embassy 1829

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXX: Chapter 1: The Rome Embassy - Continued

- Book XXX: Chapter 2: Conclaves

- Book XXX: Chapter 3: Despatches and letters

- Book XXX: Chapter 4: Further despatches and letters

- Book XXX: Chapter 5: The Marquis Capponi, letters and a despatch

- Book XXX: Chapter 6: Further letters and despatches

- Book XXX: Chapter 7: A reception for Grand-Duchess Helen at the Villa Medici

- Book XXX: Chapter 8: My relations with Bonaparte’s family

- Book XXX: Chapter 9: Pius VII

- Book XXX: Chapter 10: A despatch and a letter

- Book XXX: Chapter 11: On Presumption

- Book XXX: Chapter 12: The French in Rome

- Book XXX: Chapter 13: Walks

- Book XXX: Chapter 14: My nephew, Christian de Chateaubriand

- Book XXX: Chapter 15: A letter to Madame Récamier

Book XXX: Chapter 1: The Rome Embassy - Continued

BkXXX:Chap1:Sec1

Rome, this 17th of February 1829.

Before passing on to matters of importance I will note a few facts.

On the death of the Sovereign Pontiff the Government of the States of Rome rests in the hands of three leading Cardinals of the Order, the deacon, priest and bishop, and of the Cardinal camerlingo. The custom is for the Ambassadors to go and pay their respects, in a speech, to the congregation of Cardinals gathered for the opening of the Conclave in St Peter’s.

The body of his Holiness, first shown in the Sistine Chapel, was taken last Friday, the 13th of February to the Chapel of the Holy Sacrament in St Peter’s; it remains there until Sunday the 15th. Then it will be placed in the monument which the remains of Pius VII occupy, while the latter have been taken down into the crypt.

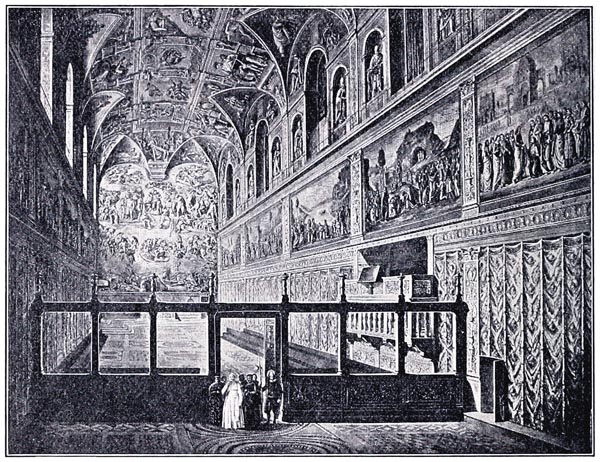

‘The Sistine Chapel in the Vatican’

A Complete Geography - Ralph Stockman Tarr, Frank Morton (p563, 1902)

Internet Archive Book Images

To Madame Récamier

‘Rome, this 17th of February 1829.

I have seen Leo XII exposed, his face uncovered, on a humble bier in the midst of Michelangelo’s masterpieces; I was present at the first funeral ceremony in St Peter’s. The elderly Cardinals superintending, no longer able to see, assured themselves that the Pope’s coffin was properly nailed shut by feeling with their fingers. By the flames of torches, inter-fused with moonlight, the coffin was finally raised by a pulley and suspended in the shadows to be deposited in the sarcophagus of Pius VII.

They brought me the poor Pope’s little cat: it is grey all over and very gentle like its former master.’

Despatch to Monsieur le Comte Portalis

‘Rome, this 17th of February 1829.

Monsieur le Comte,

I had the honour of informing you in my first letter, sent to Lyons with the telegraph despatch, and in my despatch number 15, of the difficulties I encountered getting my couriers away on the 10th. These people here are still stuck in the age of Guelphs and Ghibellines, as if the death of a Pope being known an hour earlier or later might cause an Imperial Army to invade Italy.

The obsequies of the Holy Father will be completed on Sunday the 22nd, and the Conclave will open on Monday evening the 23rd, after assisting at the Mass of the Holy Spirit in the morning: they are already furnishing the cells in the Quirinal Palace.

I will not speak about the views, Monsieur le Comte, of the Austrian Court, or the wishes of the governments of Naples, Madrid or Turin. Monsieur le Duc de Laval, in his correspondence with me in 1823, described the staff of Cardinals a part of which is still there today. You can look at number 5 and its attachment, and numbers 34, 55, 70 and 82. There are also some notes in the Ministry files, obtained elsewhere. Those pen-portraits, often enough fantasies, may amuse, but achieve nothing. Three things no longer influence the election of Popes: feminine intrigue, ambassadorial plotting, and Court power. They no longer vote in the general interest of society, but in the private interests of individuals and families who seek position and wealth from the election of a head of the Church.

There are immense tasks now awaiting the Holy See: the re-integration of dissident sects, the strengthening of European society, etc. A Pope who entered into the spirit of the century, and placed himself at the head of enlightened generations could rejuvenate the Papacy; but these ideas will not penetrate the aged heads of the Sacred College; Cardinals arriving at the end of their own lives pass on to one of themselves an elective royalty which will swiftly die with them; seated among the twin ruins of Rome, the Popes have an air of being moved by nothing but the power of death.

The Cardinals elected Cardinal Della Genga (Leo XII), following the veto on Cardinal Severoli, because they thought he was about to die. Della Genga being wise enough to live, they cordially hated him for misleading them. Leo XII chose capable administrators for the convents; another subject of complaint among the Cardinals. But, on the other hand, the deceased Pope, by advancing the monks, chose to regularise the monasteries in such a way that he won no thanks for his generosity. The wandering eremites they turned away, the working men whom they forced to take their drink standing in the street in order to avoid knife fights in the taverns; unfortunate changes in the perception of taxation, the abuse committed by some familiars of the Holy Father, even this Pope’s death arriving at a moment which has robbed the theatres and tradesmen of Rome of the benefit derived from the extravagance during the Carnival, have made the memory of a Prince worthy of the most lively regret anathema: at Civita-Vecchia they wanted to burn a house belonging to two men they thought had been honoured by his favour.

Among the many candidates, four are particularly noteworthy: Cardinal Capellari, Head of Propaganda, Cardinal Pacca, Cardinal De Gregorio and Cardinal Guistinani.

Cardinal Capellari is a capable and erudite man. He will be rejected by the Cardinals, it is said, as too young, as a monk and as a stranger to world affairs. He is Austrian and is considered fervent and set in his religious opinions. However, it is he who, consulted by Leo XII, saw nothing in the King’s decrees which justified our bishops’ complaints; it is he again who drew up the Concordat of the Court of Rome with Holland and who was of the opinion that canonical institution should be granted to the bishops of the Spanish Republic: all that suggests a rational mind, conciliatory and moderate. I had these details from Cardinal Bernetti, with whom I had one of the conversations, on Friday the 13th, which I told you of in my despatch of the 15th.

It is important to the diplomatic corps, and especially the French Ambassador, that the Secretary of State in Rome should be a man easy to deal with, and used to European affairs. Cardinal Bernetti is the Minister who suits us in all respects; he commits himself with the zelanti and the Congregationalists on our behalf; we would wish him to be retained by the future Pope. I have asked him with which of the four Cardinals would he have the best chance of being returned to power. He replied: “With Capellari.”

Cardinals Pacca and De Gregorio are described in an accurate manner in attachment number 5 of the correspondence previously cited; but Cardinal Pacca is greatly weakened by age, and his memory, like that of the Cardinal-Dean La Somaglia, fails him almost completely.

Cardinal De Gregorio would be a suitable Pope. Though ranged with the zelanti, he is not without a degree of moderation; he opposes the Jesuits who have here, as they have in France, adversaries and enemies. Neapolitan subject that he is, Cardinal De Gregorio is rejected by Naples, and even more so by Cardinal Albani, executor of Austria’s most important actions in the Conclave. The Cardinal is the legate in Bologna; he is over eighty and ill: there is therefore a possibility that he will not come to Rome.

Finally, Cardinal Giustiniani is the Cardinal of the nobility of Rome; he is a nephew of Cardinal Odescalchi, and he will probably receive a fair number of votes. But on the other hand he is poor and his relatives are poor; Rome fears the aspirations of that indigence.

You are aware, Monsieur le Comte, of all the trouble Guistiniani has made in Spain, and I know, more than most, the problems he caused me after King Ferdinand was liberated. He has been equally immoderate in the Bishopric of Imola, which the Cardinal currently governs; he has revived the decrees of Saint Louis against blasphemers: he is not a Pope for our age. In other respects, he is quite a learned man, a Hebraist, Hellenist, and mathematician, but more suited to office work than public affairs. I do not think Austria will support him.

Given all that, human predictions are often proved wrong; often a man changes on achieving power; the zelante Cardinal Della Genga became the conciliatory Pope Leo XII. Perhaps a Pope will appear, from outside these four competitors, whom no one is currently considering. Cardinal Castiglioni, Cardinal Benvenuti, Cardinal Galeffi, Cardinal Arezzo, Cardinal Gamberini, and even the venerable old Dean of the Sacred College, La Somaglia, despite being in his second childhood or rather because of it, are in the running. The latter even has some chance, since as Bishop and Prince of Ostia, his exaltation would lead to five senior positions becoming free.’

BkXXX:Chap1:Sec2

‘One assumes the Conclave will either be very lengthy or quite short: there will not be conflict over the method as there was at the time of Pius VII’s death; the Conclavists and Anti-Conclavists have completely disappeared: which should make the election straightforward. But, on the other hand, there will be individual struggles between the contenders who gather a substantial number of votes, and since they only need a third of the votes, plus one, to exclude a candidate, which should not be confounded with the right of exclusion, the balloting between the candidates could be prolonged.

Should France exercise the right of exclusion which she shares with Austria and Spain? Austria exercised it against Severoli in the previous Conclave, through its intermediary Cardinal Albani. Against whom might the French Crown wish to exercise the right? Should it be against Cardinal Fesch, if by any chance they were to consider him, or against Cardinal Giustiniani? Would the latter be worth the trouble of exercising the veto, which is always somewhat odious in that it hinders the freedom of election?

To which Cardinal would the King’s government entrust the exercising of its right of exclusion? Would it wish the French Ambassador to seem charged with his government’s secret wishes, and ready to block the Conclave’s choice if it displeases Charles X? Indeed, does the government have any preference? Is there some Cardinal to whom it wishes to lend its support? Certainly, if all the ‘family’ Cardinals, that is to say the Spanish, Neapolitan and even Piedmontese Cardinals, were to unite their votes to those of the French Cardinals, if one formed a party of the Crown, we would carry the Conclave; but these unions are fantasies and among the Cardinals we have various Courts represented who are enemies rather then friends.

We are assured that the Primate of Hungary and the Archbishop of Milan will come to the Conclave. The Austrian Ambassador in Rome, Count Lutzow, shows good intentions as regards the conciliatory character that the future Pope should possess. Let us await instructions from Vienna.

Further, I am persuaded that all the ambassadors on earth can do nothing now regarding the election of the Sovereign Pontiff and that we are all perfectly superfluous in Rome. Moreover I do not see any pressing reason to accelerate or retard (something which is anyway not in anyone’s power) the workings of the Conclave. Let the foreign Cardinals be present or not in Italy for this Conclave, as it may suit the dignity of their Courts; it will have little influence on the result of the election. If one had millions to spend, it might be possible to engineer a Pope: I see that as the only means, and France is not in the habit of doing so.

In my confidential instructions to Monsieur le Duc de Laval (13th of September 1823) I said: “We request that they place on the Pontiff’s throne a prelate distinguished for piety and virtue. We desire only that he be enlightened enough and of sufficiently conciliatory a spirit to be able to judge the political status of governments and not involve them, through idle demands, in inextricable difficulties, as regrettable for the Church as for the throne. We would prefer a moderate member of the Italian zelante party, capable of being acceptable to all parties. All we ask of them in our own interest is not to seek to profit from divisions which may occur among our clergy in order to disturb our ecclesiastical affairs.”

In a confidential letter, written concerning the illness of the new Pope Della Genga, on the 28th of January 1824, I said again to Monsieur le Duc de Laval: “What it is important for us to achieve (supposing a fresh Conclave), is that the Pope, by inclination, should be independent of the other powers; that his policies should be wise and moderate, and that his should be a friend of France.”

Today, Monsieur le Comte, should I not follow as Ambassador the spirit of the instructions that I gave as Minister?

This despatch says everything. I have nothing more to do but instruct the King succinctly on the workings of the Conclave and any incidents which may occur; it only remains to summarise the votes and the disposition of voting.

The Cardinals favourable to the Jesuits are: Giustiniani, Odescalchi, Pedicini and Bertazzoli.

The Cardinals opposed to the Jesuits for various reasons and circumstances are: Zurla, De Gregorio, Bernetti, Cappellari, and Micara.

I would imagine that, of the fifty-eight Cardinals, forty-eight or forty-nine only will be present at the Conclave. In that case, thirty-three or thirty-four votes would be sufficient to elect a Pope.

The Spanish Ambassador, Monsieur de Labrador, a reclusive and secretive man, whom I suspect is light-minded beneath a grave exterior, is very embarrassed by his role. The instructions from his Court did not anticipate the occurrence; he has written in that vein to His Catholic Majesty’s Chargé d’Affaires at Lucca.

I have the honour, etc.

P. S. Cardinal Benvenuti already has assurance, they say, of twelve votes. That choice, if it were confirmed, would be excellent. Benvenuti knows Europe, and has shown ability and moderation in various posts.

Book XXX: Chapter 2: Conclaves

BkXXX:Chap2:Sec1

Sine the Conclave is about to open, I will quickly sketch the history of that great mode of election, which has already operated for more than eighteen hundred years. How did the Papacy originate? How have the Popes been elected through the centuries?

At the time when liberty, equality and the Republic expired around the reign of Augustus, the universal tribune of the nations was born in Bethlehem, that great representative on earth of equality, liberty and the Republic, Christ, who having planted the Cross to serve as the boundary of the two worlds, after having been nailed to that Cross, and dying upon it, as the symbol, victim and redeemer of human suffering, transmitted his mantle to his foremost apostle. From Adam to Jesus Christ, it was a society that countenanced slavery, with inequality between men, and social inequality between men and women; from Jesus Christ’s to our time it has been a society of equality between men, with social equality of men and women, a society without slavery or at least the principle of slavery. The history of modern society begins at the foot of, and this side of, the Cross.

Peter, Bishop of Rome, initiated the Papacy: as tribune-dictators elected successively from among the people, and for the most part chosen from the most obscure social classes, the Popes took their temporal power from the democratic order, from that new society of brothers founded by Jesus of Nazareth, the carpenter, the maker of ploughs and yokes, born of woman in respect of the flesh, and yet God and the son of God, as his works show.

The Popes have had a mission to maintain and defend the rights of man; the leaders of human opinion, they acquired, weak as they were, the power to dethrone kings with a word and an idea: as soldiers they had only ordinary men, heads covered with a hood and hands clasping a cross. The Papacy, marching at the head of civilisation, advanced towards the goal of society. Christian men, in every quarter of the globe, would obey a priest whose name was scarcely known to them, because that priest was the personification of a fundamental reality; in Europe he represented that political liberty almost everywhere destroyed; in the world of the Goths he was the defender of popular freedoms, as in the modern world he became the preserver of sciences, letters and the arts. People enrolled in his militias in the garb of mendicant brothers.

The quarrel between the Empire and the priesthood is the struggle between two social principles of the Middle Ages, power and liberty. The Popes, favouring the Guelphs, declared themselves for government by the people; the Emperors, adopting the Ghibellines, supported government by the nobility: precisely the roles that the Athenians and Spartans played in Greece. Also, when the Popes ranged themselves on the side of kings, when they became Ghibellines, they lost power, because they were divorced from their natural principle; and, for an opposite reason, though analogous, the monks saw their authority lessen when political freedom was directly returned to the people, because the people no longer needed to be substituted by the monks, their representatives.

Those thrones declared vacant and handed over to the first comer in the Middle Ages; those Emperors who knelt to beg the Pontiff’s forgiveness; those kingdoms placed under a ban; a whole nation deprived of religion by a magic word; those sovereigns struck by anathema, abandoned not only by their subjects, but also their relatives and servants; those princes avoided like lepers, exiled from the eternal race; the food they had tasted, the objects they had touched passed through the flames as tarnished things: all of that was the vigorous effect of popular sovereignty delegated to religion and exercised by it.

The longest-lived electoral process in the world is the system by which the power of the Pontiff has been transmitted by St Peter to the priest who wears the tiara today: from this priest one can go back, from Pope to Pope, to the saints who were with Christ; in the first link of the Pontifical chain a God resides. The bishops were elected by a general assembly of the faithful; from the time of Tertullian, the Bishop of Rome was made a bishop by other bishops. The clergy joining cause with the people worked together to bring about the election. As passions are met with everywhere, as they harm the finest institutions and the most virtuous characters, to the extent that Papal power increased it tended to bring benefits, and human rivalry then produced great disorder. In pagan Rome, similar troubles broke out during elections of the tribunes: one of the two Gracchi was hurled into the Tiber, the other stabbed to death by a slave, in a wood consecrated to the Furies. The nomination of Pope Damasus, in 366, produced bloodshed: a hundred and thirty seven people died in the Basilica Liberiana, today Santa Maria Maggiore.

Saint Gregory was considered to be elected as Pope by the clergy, the senate and the Roman people. Any Christian man could attain the tiara: Leo IV was promised the sovereign pontificate on the 10th of April 847 for defending Rome against the Saracens, and his ordination postponed until he had shown proof of his courage. Similarly in the creation of other bishops: Simplicius was elevated to the See of Bourges, layman though he was. Even today (something generally unknown) the Conclave’s choice could fall on a layman: be he married his wife would enter the religion, and take orders, on his becoming Pope.

The Greek and Latin Emperors wished to constrain the freedom of Papal election by popular vote; they sometimes usurped the right, and often required the election to be confirmed by them as a minimum: an ordinance of Louis the Debonair returned the election of the bishops its ancient freedom which was that it be attained, according to a treaty of the same date, by the unanimous consent of the clergy and the people.

The danger of an election proclaimed by the masses or dictated by the Emperor forced a change in the law. In Rome there were priests and deacons known as cardinals, their name given to them because they served at the cornua or corners of the altar, ad cornua altaris, or because the word cardinal was derived from the Latin cardo, a pivot or hinge. Pope Nicholas II, in a council held at Rome in 1059, decided that the Cardinals alone should elect the Pope and the clergy and the people ratify his election. A hundred and twenty years later, the third Lateran Council did away with the ratification by the clergy and the people and rendered the election valid if it gained a majority of two thirds of the votes in the assembly of Cardinals.

But the Council’s canon fixing neither the duration nor the form of the Electoral College the result was discord among the electors, and they lacked the means, within those fresh modifications of the law, to put an end to the disorder. In 1268, after the death of Clement IV, the Cardinals meeting in Viterbo could not agree, and the Holy See remained vacant for three years. The Podesta (Chief Magistrate) and the people of the town were obliged to shut the Cardinals in their palace, and even, they say, to remove the roof to force the electors to come to a decision. Gregory X emerged at last from the ballot, and in order to prevent such a problem in future, established from that time on the Conclave CUM CLAVE, under lock and key; he regulated the internal organisation of the Conclave close to the form in which it exists today: separate cells, a meeting room for the ballot, exterior windows to be blocked up, and the election proclaimed from one of these, on demolishing the plaster with which it is sealed, etc. The Council held at Lyons in 1274 confirmed and improved these arrangements. Yet one article of the rules has fallen into disuse: it said that if after three days of confinement no candidate had been chosen, for five days after this the Cardinals would have only a single dish at their meal, and for the days following would have only bread, wine and water until the sovereign Pontiff was elected.

Today the duration of the Conclave is no longer limited and a Spartan diet is no longer used to punish the Cardinals like penitent children. Their meals, placed in baskets and carried on trays, arrive before them accompanied by a lackey in livery; a steward follows the convoy, sword at his side, in the emblazoned coach, drawn by caparisoned horses, of one of the imprisoned cardinals. Arriving at the building where the Conclave is being held, the chickens are cut open, the pies drilled, the oranges quartered, and the bottles un-corked, for fear that some Pope might be inside. These ancient customs, some childish, others ridiculous, have their disadvantages. Is the repast sumptuous? Then the poor, dying of hunger, seeing it pass, compare it with their own and mutter. Is the dinner a light one? With a complementary natural reaction, the indigent mock the purple robes with contempt. They would do well to abolish this custom which is no longer current practice; Christianity is returning to its source; it is revisiting the age of Holy Communion and the Agape, and Christ alone should preside today at these feasts.

BkXXX:Chap2:Sec2

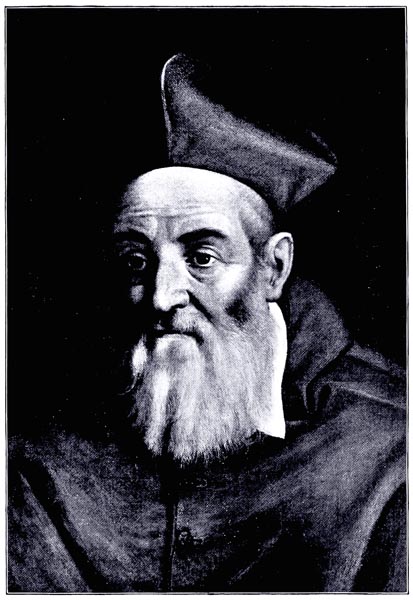

The intrigues within the Conclaves are notorious: some have had disastrous results. During the schism with the East various Popes and anti-Popes cursed and excommunicated one another, from the heights of the ruined walls of Rome. The schism seemed ready to be healed, when Pedro de Luna re-opened it, in 1394, by intrigue at the Conclave in Avignon. Alexander VI, in 1492, bought the votes of twenty two Cardinals who prostituted the tiara to him, leaving behind him the memory of Lucrezia. Sixtus V’s only intrigue in the Conclave was to make use of crutches, though when he was Pope his genius had no need of those aids. In a villa in Rome I have seen a portrait of his sister, a woman of the people, whom the terrible Pontiff, in all his plebeian pride, chose to have painted. ‘The noblest arms of our House,’ he told his sister, ‘are our rags.’

‘Sixtus V, by Sassoferrato’

The art of the Vatican; a Brief History of the Palace, and an Account of the Principal Works of Art Within its Walls - Mary Knight Potter (p56, 1903)

Internet Archive Book Images

It was still an age when sovereigns dictated orders to the Sacred College. Philip II sent notes to the Conclave: ‘Su Magestad no quiere que N. sea Papa; quiere que N. le tenga: His Majesty does not wish N to be Pope, he wishes N to be such’. Following this period, intrigues within the Conclave were scarcely more than ripples without specific result. Duperron and d’Ossat nevertheless obtained the reconciliation of Henri IV with the Holy See, which was a great event. Duperron’s Embassies were somewhat inferior to D’Ossat’s Letters. Before them, Du Bellay had been involved with trying to prevent the schism with Henry VIII. Having obtained from that tyrant, before his separation from the Church, a promise that he would submit to the judgement of the Holy See, he arrived in Rome at the moment when the condemnation of Henry VIII was about to be pronounced. He obtained a delay in order to send a confidential agent to England; the reply was delayed by the state of the roads. The supporters of Charles V had sentence pronounced, and the bearer of Henry VIII’s instructions arrived two days later. A courier’s delay ensured England became Protestant, and changed the political landscape of Europe. The world’s destiny hangs on things no more weighty: too large a cup, emptied in Babylon, did for Alexander.

Later, Cardinal de Retz, came to Rome, at the time of Olimpia, and in the Conclave following the death of Innocent X, enrolled in the flying squadron, a name given to ten independent Cardinals; they brought with them Sacchetti, only good for having his portrait painted, to elect Alexander VII, savio col silenzio (wise and reticent), and who, having become Pope, turned out to be nothing special.

The President de Brosses recounts the death of Clement XII which he witnessed, and he saw the election of Benedict XIV – as I have seen the Pontiff, Leo XII, dead on his bier, abandoned: the Cardinal Camerlingo struck Clement XII on the forehead two or three times according to custom with a little hammer, calling him by his name, Lorenzo Corsini: ‘He did not respond’ says de Brosses, ‘and the Cardinal quoted: “That's what’s making your daughter mute.”’ And that is how in those days they treated serious matters: a dead Pope one taps on the head as if tapping at the gate of understanding, while calling the deceased and silent man by his name, might, it seems to me, inspire in a witness something other than a jest, even if it was written by Molière. What would the light-minded Magistrate from Dijon have said if Clement XII had replied from the depths of eternity: ‘What do you want with me?’

The President de Brosses sent his friend the Abbé Courtois a list of Cardinals attending the Conclave with a few words in honour of each:

‘Guadagni, a bigot, a hypocrite, lacks wit, lacks taste, a poor monk.

Aquaviva d’Aragon, a noble, somewhat heavily built, his wit is like his build.

Ottoboni, lacks morals, lacks credit, debauched and ruined, an amateur of the arts.

Alberoni, full of fire, agitated, restless, despised, lacks morals, lacks decency, lacks consideration, lacks judgement: according to him, a Cardinal is a wastrel dressed in red.’

The rest of the list is in keeping; the only wit here is cynicism.

A singular piece of buffoonery took place: de Brosses went to dinner with the English at the Porta San Pancrazio; they acted out the Papal election; Ashewd took off his wig and played the Cardinal-Dean; they chanted their oremus, and Cardinal Alberoni was elected by a ballot of the parties. The Protestant soldiers of the army of the Constable de Bourbon had once nominated Martin Luther for Pope, in the Church of St Peter. Today the English, who are at once Rome’s hurt and its salvation, respect the Catholic religion which has permitted them to inaugurate a chapel outside the Porta del Popolo. The government, and custom, will not accept any greater scandal.

‘Villa Pamphilj outside the Porta San Pancrazio’

From Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome) - Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Italian, 1720-1778)

Yale University Art Gallery

As soon as a Cardinal is enclosed in Conclave, the first thing they do, he and his servants, is to scrape at the freshly plastered walls in the darkness, until they have made a little hole and then dangle strings from it by means of which messages can pass and re-pass between the inside and outside. In addition, Cardinal de Retz, whose opinion is not to be scorned, having spoken of the miseries of the Conclave he had participated in, finished his recital with these fine words:

‘In the time spent there together (in the Conclave) one always showed the same respect and civility as is seen in the chambers of kings; the same politeness as in the Court of Henri III; the same familiarity as in the colleges; the same modesty found in novices, and the same charity, at least on the surface, as could ever be displayed among brothers in perfect unity.’

I am struck, in ending this summary of a long history, by the serious manner with which it begins and the atmosphere of burlesque almost with which it ends; the greatness of the Son of God opens the scene which, diminishing by degrees, the further the Catholic religion is from its source, terminates in the pettiness of the sons of Adam. One scarcely discovers the ancient nobility of the cross except at the death of a Sovereign Pontiff: the Pope, free of family or friends, the body isolated on its bier, shows that the man counts for nothing as head of the Evangelical world. As a temporal Prince, honours are rendered to the dead Pope; as a man, his abandoned corpse is set down at the door of the church, where the sinner once did penance.

Book XXX: Chapter 3: Despatches and letters

BkXXX:Chap3:Sec1

Despatches to Monsieur le Comte Portalis

‘Rome, the 17th of February 1829.

Monsieur le Comte,

I am unclear whether the King will be pleased to send a special Ambassador to Rome or whether it may suit him to accredit me to the Sacred College. In the latter case, I would have the honour to observe to you that I allocated to Monsieur le Duc de Laval, in 1823, in similar circumstances, a sum, to defray his exceptional expenditure which, as far as I can remember, amounted to 40,000 to 50,000 francs. The Austrian Ambassador, Count von Nagy-Appony received a sum of 36,000 francs for his initial needs, a supplement of 7,200 francs a month to his normal salary during the Conclave, and for the costs of gifts, the chancellery etc. 10,000 francs. I have no pretensions, Monsieur le Comte, to compete in magnificence with Monsieur the Ambassador of Austria, as Monsieur le Duc de Laval did; I will not be hiring horses, carriages, or livery to dazzle the people of Rome; the King of France is a great enough master to pay for his Ambassador’s pomp if he wishes: borrowed magnificence is wretched. I will go to the Conclave with my people and my ordinary carriages then in a modest manner. It remains to be known whether His Majesty might not think that during the Conclave I might be obliged to put on a display for which my ordinary salary might be inadequate. I am not requesting anything; I am simply submitting a question to your judgement and the Royal decision.

I have the honour, etc.’

‘Rome, the 19th of February 1829.

Monsieur le Comte,

Yesterday, I had the honour of being presented to the Sacred College and giving the little speech of which I sent you an advance copy with my despatch no. 17, which left Tuesday, the 17th of the month, by special courier. I was heard with signs of satisfaction which augurs well, and the Cardinal-Dean, the venerable La Somaglia replied in terms showing great affection for the King and France.

Having fully informed you in my last despatch, I have absolutely nothing new to tell you today, except that Cardinal Bussi arrived yesterday from Benevento; today we await Cardinals Albani, Macchi and Opizzoni.

The members of the Sacred College will be locked in the Quirinal Palace on Monday evening, the 23rd of this month. Ten days are then allowed for the arrival of foreign Cardinals, after which the serious business of the Conclave will commence, and if they agree quickly the Pope could be elected in the first week of Lent.

‘The Quirinal’

New guide of Rome, Naples and their Environs - Mariano Nibby Vasi (p150, 1844)

Internet Archive Book Images

I await, Monsieur le Comte, the King’s orders. I assume you sent a courier to me once Monsieur de Montebello reached Paris. It is urgent for me to receive news of an extraordinary ambassador or fresh letters of accreditation for me, with the government’s instructions.

When will the five French Cardinals arrive? Politically speaking, their presence is hardly necessary here. I have written to Monsignor the Cardinal de Latil to offer him my services in the event that he decides to come.

I have the honour, etc.

P. S. I enclose a copy of a letter which Monsieur le Comte de Funchal has written to me. I have not replied in writing to the Ambassador, I only intend to speak to him.’

To Madame Récamier

‘Rome, Monday the 23rd of February 1829.

Yesterday the Pope’s obsequies ended. The pyramid of paper and the four candelabras were fine, since they were of immense proportions and reached the cornice of the church. The final Dies Irae was admirable. It was composed by an unknown musician belonging to the Pope’s chapel, who seemed to me to possess a genius quite different to that of Rossini. Today we pass from sadness to joy; we sing the Veni Creator to open the Conclave; next we shall go each evening to see if the ballot is signalled or not, whether that is the smoke rises from a particular chimney: the day on which there is no smoke, the Pope will be named, and I will come to meet you once more; that will be the end of my business here. The King of England’s speech is very offensive to France! What a deplorable expedition this one to the Morea! Has that been understood yet? General Guilleminot has written me a letter on the matter, which made me smile; he could only write to me thus because he thinks I am still a Minister.’

‘25th of February.

Death is here; Torlonia departed yesterday evening after two days of illness: I have seen him ‘all made up’ on his funeral bier, sword at his side. He granted loans against securities; but what securities! Against antiques, paintings hung pell-mell in an old dusty palace. Not the shop though where the Miser kept “a lute from Bologna furnished with all its strings, or nearly all, a lizard’s skin three feet long, and a four poster bed decorated with Hungarian lace.”

One sees only the dying whom they take out for walks in the street fully dressed; one of them passes regularly beneath my windows whenever we sit down to dinner. Moreover, everything announces a spring departure; people are beginning to disperse; they are leaving for Naples; they will return for a while for Holy Week, and then depart for good. Next year there will be other visitors, other faces, and another society. There is something sad in this scurrying through the ruins: the inhabitants of Rome are like the debris of their city: the world passes by at their feet. I imagine people returning to their families in various European countries, young Misses returning in the midst of fog. If by chance, thirty years from now, one of them was brought to Italy, who would remember having seen them in this Palace whose masters no longer exist? St Peter’s and the Coliseum; that is all they themselves would recognise.’

Book XXX: Chapter 4: Further despatches and letters

BkXXX:Chap4:Sec1

Despatch to Monsieur le Comte Portalis

‘Rome, this 3rd of March 1829.

Monsieur le Comte,

My first courier having arrived at Lyons on the 14th of last month at nine in the evening, you will have learnt on the morning of the 15th, by telegraph, of the Pope’s death. It is now the 3rd of March and I am still awaiting instructions or any official reply. The newspapers have announced the departure of two or three Cardinals. I have written to Paris to Monsieur le Cardinal de Latil, in order to place the Ambassadorial palace at his disposal; I have just written again to various points on his route, to renew the offer.

I am sorry to have to tell you, Monsieur le Comte, that I notice various petty intrigues here aimed at removing our Cardinals from the Embassy, in order to lodge them so that they can be placed nearer to the influences they hope to exert on them.

As far as I am concerned, it is for the most part a matter for indifference. I will render Messieurs les Cardinals all the services in my power. If they interrogate me on issues which it would be useful to know about, I will tell them what I know; if you transmit the King’s orders for them via myself, I will inform them of such; but if they arrive here in a hostile frame of mind towards the views of His Majesty’s government, if it is seen that they are not in agreement with the King’s Ambassador, if they use language contrary to mine, if they go as far as to show their support in the Conclave for any extreme individual, even if they are only divided among themselves, nothing would be more disastrous. It would be better for the King’s service if I gave my resignation in instantly than offer up our disagreements to a public spectacle. Austria and Spain, in their relationship with the clergy behave so as to leave no opening for intrigue. No priest, no Austrian or Spanish Cardinal or Bishop, is allowed an agent or correspondent in Rome other than the Ambassador belonging to his Court; the latter has the right to dismiss instantly from Rome any ecclesiastic of his nation who presents an obstacle to him.

I hope, Monsieur le Comte, that no division will occur, that Messieurs the Cardinals will show the positive desire to submit to the instructions which I will not be long in receiving from you; and that I will know which of them is charged with exercising the veto, if needed, and to which names the veto may be applied.

It is necessary to be very careful: the last few ballots have shown an awakening of party allegiance. That party, which has given twenty to twenty-one votes to Cardinals Della Marmora and Pedicini, forms what they call here the Sardinian faction. The other Cardinals, taking fright, wish to give all their votes to Opizzoni, an individual both firm and moderate. Though Austrian, that is to say from Milan, he has stood up to Austria in Bologna. He would be an excellent choice. The votes of the French Cardinals, in fixing on one or the other candidate, could decide the election. Rightly or wrongly, it is believed the Cardinals are opposed to the King’s present system of government, and the Sardinian faction is counting on them.

I have the honour, etc.’

To Madame Récamier

‘Rome, the 3rd of March 1829.

You surprise me regarding the story of my excavations; I did not remember writing you anything so fine in regard of them. I am, as you can imagine, greatly pre-occupied: left without direction or instructions, I am obliged to take everything upon myself. I think however that I can promise you a moderate and enlightened Pope. God grant only that it may be over by the expiry of the interim period of Monsieur de Portalis’ Ministry.’

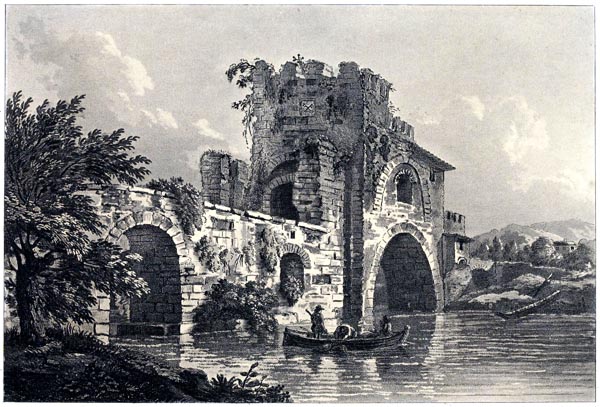

‘4th of March.

Yesterday, Ash Wednesday, I knelt alone in that church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, supported by the walls of Rome, near to Porta Maggiore. I heard the monotonous and dismal chanting of the monks in the interior of that solitary space: I would have liked to have been dressed in a robe too, chanting among the ruins. What better place to subdue ambition and contemplate the vanities of this world! I do not speak to you about my health because it is extremely tedious. While I am suffering, they tell me Monsieur de La Ferronays is cured; he rides on horseback, and his convalescence is regarded here as a miracle: God grant he remains so, and takes up the portfolio at the end of the interim period: how many matters that would solve, for me!’

‘Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, and Nero's Aqueduct’

Italy from the Alps to Mount Etna - Karl Stieler, conte Antonio Sangiuliani di Gualdana, Eduard Paulus, Woldemar Kaden, Frances Eleanor Trollope, Thomas Adolphus Trollope (p331, 1877)

Internet Archive Book Images

Despatch to Monsieur le Comte Portalis

‘Rome, this 15th of March 1829.

Monsieur le Comte,

I have the honour to inform you of the successive arrivals of Messieurs the French Cardinals. Three of them, Messieurs de Latil, de La Fare, and de Croy, are doing me the honour of staying with me. The first entered the Conclave on Thursday evening the 12th, with Monsieur le Cardinal Isoard; the two others were incarcerated on Friday evening, the 13th.

I have informed them of everything I know; I have communicated to them important notes on the minority and majority factions of the Conclave, and the sentiments with which the various parties are animated. We are agreed that they would support the candidates of whom I have spoken to you, namely: Cardinals Capellari, Opizzoni, Benvenuti, Zurla, Castiglioni, lastly Pacca and De Gregorio; and that they would reject the Cardinals of the Sardinian faction: Pedicini, Giustiniani, Galeffi and Cristaldi.

I hope that this good relationship between the Ambassadors and the Cardinals will produce the right result: at least I shall have nothing to reproach myself with if passions or interests rob me of my hopes.

I have discovered, Monsieur le Comte, despicable and dangerous intrigue between Paris and Rome being conducted through the channel of Monsieur the Nuncio Lambruschini. It is a matter of nothing less than having had read out in open Conclave a copy of supposed instructions, divided into several articles and given (it was impudently claimed) to Monsieur le Cardinal de Latil. The majority of the Conclave declared itself vigorously against such machinations; they would have liked the Nuncio to be told to break off all relations with the troublemakers who, by disturbing France, would end by making the Catholic religion odious to all. I have made a collection, Monsieur le Comte, of these authentic revelations, and I will send them to you after the Pope’s nomination: that would be better than any amount of despatches. The king will learn to know his friends and enemies, and the Government will be able to rely on proper facts to direct its actions.

Your despatch no.14 advised me of the attempts at ecclesiastical encroachment which His Holiness’ Nuncio wished to renew in France on the death of Leo XII. The same thing happened when I was Foreign Minister on the death of Pius VII; happily there is always a mean of defence against these public attacks; it is much more difficult to escape designs woven in the shadows.

The Conclavists who accompany our Cardinals seem reasonable men: only Abbé Coudrin, whom you spoke to me about, is one of those dull narrow minds into which nothing can enter, one of those men who have mistaken their calling. You are not unaware that he is a monk, the head of his order, and that he even issues institutional bulls: it is scarcely in accord with our civil laws and our political institutions.

It could be that the Pope has been elected by the end of this week. But if the French Cardinals fail of the first effects of their presence, it will be impossible to assign a limit to the Conclave. Fresh alignments might lead to an unexpected nomination: in order to conclude, they might agree on an insignificant Cardinal, such as Dandini.

I have formerly, Monsieur le Comte, found myself in difficult circumstances, as Ambassador to London, as Minister during the Spanish War, as a member of the Chamber of Peers, as leader of the Opposition; but nothing has given me as much worry and concern as my present position in the midst of all kinds of intrigue. I have to work on an invisible body shut in a prison whose environs are strictly guarded. I have neither money to grant nor places to promise; the precarious passions of fifty or so old men offer me no hold. I have to combat stupidity in some, and ignorance of the present-day in others; fanaticism in this group, shrewdness and duplicity in that; in almost all of them ambition, interest, political hatreds, and I am isolated from them by the walls and the mysteries of their gathering in which so many divisive elements ferment. At every instant the landscape changes; every quarter of an hour contradictory reports plunge me in fresh perplexities. It is not, Monsieur le Comte, to stress my worth that I tell you of all these difficulties, but to serve as my excuse in the event that the election produces a Pope contrary to that which it appears to promise and to the nature of our wishes. On the death of Pius VII, religious questions had not yet aroused public opinion: those questions have today become involved in politics, and never has the election of a Head of the Church fallen at a more inappropriate time.

I have the honour, etc.’

To Madame Récamier

‘Rome, the 17th of March 1829.

The King of Bavaria came to see me in his morning-coat. We spoke of you. This Greek sovereign, in wearing a crown, seems to know what he has on his head, and to understand that you cannot nail time to the past. He dines with me on Thursday and does not want anyone else.

As for the rest, here we are in the midst of great events: a Pope to be elected; who will it be? Will the Catholic Emancipation Bill be passed? A new campaign in the East; whose will be the victory? Will we profit from our situation? Who will conduct our affairs? Is there a mind capable of seeing all that exists in it for France and profiting according to circumstances? I am sure it is not the only thing they think about in Paris, and that between the salons and the Chambers, pleasure and law-making, the delights of the world, and Ministerial anxieties, they have little concern for Europe. It is only I, in my exile, who have the time to dream idly and look around me. Yesterday I went for a walk in a kind of storm along the ancient Tivoli road. I arrived at ancient Roman paving so well preserved one might have thought it only just put down. Horace may have trod the stones on which I walked; where is Horace now?’

Book XXX: Chapter 5: The Marquis Capponi, letters and a despatch

BkXXX:Chap5:Sec1

The Marquis Capponi arriving from Florence has brought me letters of recommendation from his female friends in Paris. I replied to one of these letters on the 21st of March 1829:

‘I have received both your letters; the services I can render you are trivial, but I am always at your command. I was not to be told what the Marquis Capponi was like: I tell you that he is always excellent; he has held fair in contrast to the weather. I did not reply to your first letter so full of enthusiasm for the sublime Mahmud and his disciplined barbarians, those slaves beaten into soldiers. That women might be transported with admiration for men who marry hundreds at a time, and might take that for enlightened and civilised progress, I can conceive; but I hold fast to my poor Greeks; I wish for their liberty as I do that of France; I also desire frontiers that will protect Paris, and assure our independence, and it is not by means of the triple alliance of Constantinople’s impalements, Vienna’s canes, and London’s fists that you will win the banks of the Rhine. Small thanks for the cloak of honour that our glory could obtain from the invincible leader of the true believers, who has not yet emerged from the surroundings of his seraglio: I prefer that glory naked; she is feminine and beautiful: Phidias would have taken great care not to give her a Turkish dressing gown.’

To Madame Récamier

‘Rome, the 21st of March 1829.

Well! I am right, not you! Yesterday I went to Sant’Onofrio, between two ballots, while waiting for a Pope: there are two orange trees in the cloister, the green oak is elsewhere. I am quite proud that my recollection was correct. I hastened, almost eyes closed, to the little stone which covers your friend; I prefer it to the grand tomb they are going to raise for him. What delightful solitude! What a wonderful view! What happiness to rest there between frescoes by Domenichino and those of Leonardo da Vinci! I would like to stay there: I have never been more tempted. Were you allowed to enter the interior of the monastery? Did you see, down a long corridor, that ravishing head, though almost half-effaced, of a Leonardo Madonna? Did you see in the library Tasso’s death-mask, his withered crown of laurel, a mirror he used, his writing case, his pen and a letter in his handwriting, placed on a shelf below his bust? In the letter in small faded writing, but easy to read, he speaks of friendship and the winds of fortune; the latter scarcely blew favourably for him, and friendship often failed him.

No Pope yet, we await one from hour to hour; but if the choice has been delayed, if obstacles are raised on every side, it is not my fault: they should have listened to me a bit more and not acted in almost a contrary manner to what they seem to want. For the rest, it seems to me that at present all the world wants to be at peace with me. The Cardinal de Clermont-Tonnerre himself has just written to me requesting my former kindness towards him, and then that he is to stay with me, and is resolved to vote for the most moderate Pope.

You have read my second speech. Thank Monsieur Kératry who spoke so obligingly about the first; I hope he will be more pleased still with the other. We are both trying to bring back Christian liberty, and we will succeed. What do you think of the response Cardinal Castiglioni made? Was I praised enough in open Conclave? You could not have done better in your days of flattery.’

‘24th of March 1829.

If I were to believe the rumours in Rome, we shall have a Pope tomorrow; but I am discouraged at the moment, and do not choose to believe such happiness. You surely understand that the happiness I speak of is not a political one, the joy of triumph, but the happiness of being free and meeting you once more. If I talk to you about the Conclave so much, I am like a man with an obsession who thinks the world is only concerned with his obsession. And yet, who thinks of the Conclave in Paris, who cares about the Pope and my tribulations? French levity, the interests of the moment, the debates in the Chambers, the stir of ambition, provide other things to worry about. When the Duc de Laval wrote to me of his concerns about the Conclave, preoccupied as I was with the War in Spain, I said on receiving his despatches: Oh! Good God, it’s hardly the time to be worrying about that!! Monsieur Portalis today ought to subject me to a like sentence. Yet it is true to say that things at that time were not as they are today: religious ideas were not confounded with political ideas as they are all over Europe; the dispute was not there; the nomination of a Pope could not, as now, disturb or calm the nations.

Since the letter which told me of the extension to Monsieur de La Feronnays’ leave and his departure for Rome, I have heard nothing: yet I think the news is true.

Monsieur Thierry has written me a moving letter from Hyères; he tells me he is dying, and yet he wants a place in the Académie des Inscriptions and asks me to write on his behalf. I will do so. My excavation continues to yield sarcophagi; the dead can only provide us with what they have. The Poussin monument advances. It will be great and noble. You would not believe how much the painting of the Shepherds in Arcady was made for bas-relief and how suitable it is for sculpture.’

‘Hyères. On the Toulon Road, Looking Towards Carquieranne’

The Riviera...New Edition. Illustrated, etc. - Hugh Macmillan (p27, 1892)

The British Library

‘28th of March.

Monsieur le Cardinal de Clermont-Tonerre, who is staying with me, entered Conclave today; it is the age of miracles. I have with me Marshal Lannes’ son and the Chancellor’s grandson; gentlemen of Le Constitutionnel dine at my table next to gentlemen of La Quotidienne. That is the benefit of being sincere; I allow each to think as he wishes, so long as they accord me the same freedom. I merely try to ensure my opinion retains the majority, since I find it, with reason, better than others. It is to my sincerity that I attribute the tendency for the most divergent opinions to cluster about me. I exercise right of sanctuary towards them: no one can arrest them under my roof.’

To Monsieur le Duc de Blacas

‘Rome, the 24th of March 1829.

I am truly annoyed, Monsieur le Duc, that a sentence in my letter could have caused you any distress. I have no complaint at all to make of a man of sense and intelligence (Monsieur Fuscaldo) who only speaks diplomatic common-places to me. Do we Ambassadors speak of anything else? As for the Cardinal whom you did me the honour of mentioning, the French government has not designated any particular individual; it is relying entirely on what I have said. Seven or eight moderate and peaceable Cardinals, who seem to be attracting the support of all the Courts, are the candidates among whom we hope to see the votes cast. But if we have no pretensions to impose a choice on the majority of the Conclave, we will oppose with all our powers and by any means the three or four extreme Cardinals, inept or involved in intrigue, supported by a minority.

I have no means, Monsieur le Duc, of transmitting this letter to you; so I will simply put it in the post, since it contains nothing that you or I would not admit to in public.

I have the honour, etc.’

To Madame Récamier

‘Rome, the 31st of March 1829.

Monsieur de Montebello has arrived and has brought me your letter with letters from Monsieur Bertin and Monsieur Villemain.

My excavation goes well, I have found plenty of empty sarcophagi; I can choose one of them for myself, without which my dust will be forced to follow that of the ancient dead which the wind has already dispersed. Bodiless sepulchres offer the suggestion of resurrection and yet they only await a more profound death. It is not life but nothingness that has left these tombs deserted.

To complete my little diary of the moment, I will tell you that the day before yesterday I climbed to the ball on the top of St Peter’s during a storm. You cannot imagine the roar of the wind from the depths of the sky, round Michelangelo’s cupola, and above that temple of the Christians, which erased ancient Rome.’

‘31st of March, evening.

Victory! I have one of the Popes whom I placed on my list: it is Castiglioni, the very Cardinal I supported for the Papacy in 1823, when I was Minister, he who has replied to me recently in this Conclave of 1829, giving me plenty of praise. Castiglioni is a moderate and devoted to France: it is a complete triumph. The Conclave, before dispersing, has ordained that the Nuncio in Paris be asked to express to the King the satisfaction the Sacred College has found in my conduct. I have already sent the news to Paris by telegraph. The Prefect of the Rhône is the intermediary in this aerial correspondence, and that prefect is Monsieur de Brosses, the son of that Comte de Brosses, the flippant traveller to Rome, often cited in the notes I gather while writing to you. The courier who brings you this letter carries my despatch to Monsieur Portalis.

I no longer have two days of good health together; and that enrages me, since I have energy for nothing in the midst of my woes. Yet I await with some impatience the results of the Pope’s nomination in Paris, what will be said, what will be done, what will become of me. The most certain is the leave I asked for. I have seen in the newspapers the fine dispute the Constitutionnel has started regarding my speech; it accuses the Messager of not having printed it, and yet in Rome we have the Messager of the 24th of March (the dispute began on the 24th and 25th) which carried the speech. Is that not odd? It seems clear that there were two editions, one for Rome and the other for Paris. Poor people! I am thinking of the setback to another paper; it assures us that the Conclave would have been very dissatisfied with the speech: what will it say when it sees the praise that Cardinal Castiglioni, who has been made Pope, bestowed on me?

When will I be able to stop talking to you about all this wretched stuff? When will I be free to do no more than finish the memoirs of my life and my life with them, with the last page of my Memoirs? I have much need of it; I am very weary, the burden of years increases and weighs on my brow; I amuse myself by calling it rheumatism, but one is not cured of this disease. A single word sustains me, I keep repeating: “Soon.”’

‘3rd of April.

I forget to tell you that since Cardinal Fesch behaved very well in the Conclave, and voted with our Cardinals, I have made an approach and invited him to dinner. He has refused in a note full of moderation.’

Despatch to Monsieur le Comte Portalis

‘Rome, this 2nd of April; 1829.

Monsieur le Comte,

Cardinal Albani has been named as Secretary of State, as I had the honour of informing you in my first letter which was carried to Lyons by the mounted courier sent on the evening of the 31st of March. The new Minister displeases both the Sardinian faction, the majority in the Sacred College, and even Austria, because he is a violent anti-Jesuit, harsh in manner, and an Italian before everything. Rich and exceedingly avaricious, Cardinal Albani is mixed up in all sorts of enterprises and speculations. I went to visit him for the first time yesterday; as soon as he saw me, he cried: “I am a pig! (He was indeed very dirty.) You can see I am no enemy.” I inform you, Monsieur le Comte, of his very words. I replied that I was far from regarding him as an enemy. “It is water not fire that is needed for your people”, he continued: “do I not know your country? Have I not lived in France? (He speaks French like a Frenchman). You will be content and your master too. How is the King? Good day! Let us go to St Peter’s.”

It was eight in the morning; I had already seen His Holiness and all Rome was hurrying to the ceremony of adoration.

Cardinal Albani is a man of spirit, false of character, yet of an open humour; his violence foils his cunning; one can take advantage of him by flattering his pride and satisfying his avarice.

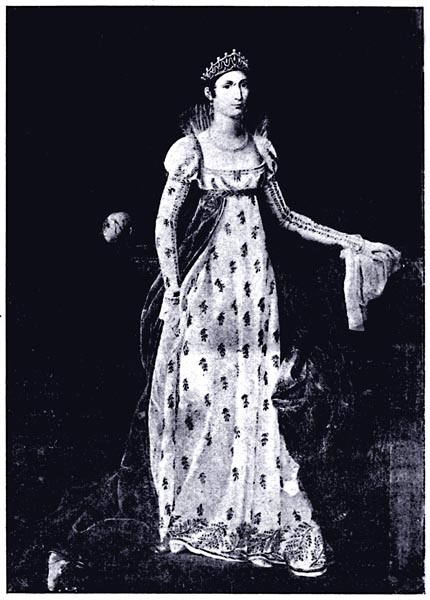

Pius VIII is very knowledgeable, especially on theological matters; he speaks French, but with less grace and facility than Leo XII. He is afflicted by a semi-paralysis of his right side and subject to convulsive movements: supreme power will heal him. He will be crowned next Sunday, the 5th of April, Passion Sunday.

‘Pope Pius VIII, 1829 - 1830’

Carl Friedrich Voigt (German, 1800-1874)

Yale University Art Gallery

Now that the main business which kept me in Rome is concluded, Monsieur le Comte, I would be infinitely obliged if you would obtain a few months leave of absence for me, with His Majesty’s blessing. I would not employ it until after handing Pius VIII the letter which His Majesty will send in reply to that which Pius VIII has written or is about to write to him, to announce his elevation to the chair of St Peter. Allow me to solicit anew on behalf of my two secretaries to the legation, Monsieur Bellocq and Monsieur de Givré, the favour towards them that I previously sought of you.

Cardinal Albani’s intrigues in the Conclave, the supporters he acquired, even among the majority, made me fear some unexpected coup which would carry him to the sovereign Pontificate. It seemed unacceptable to me to allow him to surprise us thus and allow the Austrian Chargé d’Affairs to place the tiara on his head under the eyes of the French Ambassador: I profited then from the arrival of Monsieur le Cardinal de Clermont-Tonnerre, charging him, at all events, with the enclosed letter in which I made those arrangements within my responsibility. Happily he did not have to make use of the letter in the matter; he returned it to me and I have the honour of sending it to you.

I have the honour, etc, etc.’

Book XXX: Chapter 6: Further letters and despatches

BkXXX:Chap6:Sec1

To his Eminence Mgr. le Cardinal de Clermont-Tonnerre

‘Rome, this 28th of March 1829.

No longer being able to communicate with your colleagues the French Cardinals who are enclosed in the palace of Monte-Cavallo (Quirinal); being obliged to make plans in the interests of our country and to the benefit of the King’s service; knowing how often unexpected nominations have arisen in previous Conclaves, I regret the unfortunate necessity of entrusting Your Eminence with a potential veto.

Though Monsieur le Cardinal Albani seems to have no chance, he is nevertheless a man of ability, on whom, in a prolonged dispute, one might cast one’s eyes; but he is the Cardinal charged in Conclave with instructions from Austria; Monsieur le Comte de Lutzow, in his speech, officially designated him in that role. Now, it is impossible to allow a Cardinal with overt allegiance to a court, to the French court no more than to any other, to attain the Sovereign Pontificate.

In consequence, Monsignor, I charge you, by virtue of my full powers, as Ambassador of His Very Christian Majesty, and taking upon myself the whole responsibility, to exercise the veto against Monsieur le Cardinal Albani, if by a gathering in his favour on the one hand, or by a secret alignment on the other, he happens to gain a majority of votes.

I am etc, etc.’

This letter regarding the veto, confided to a Cardinal by an Ambassador who is not formally authorised to do so, is rash diplomacy: there is something in doing so which makes all Statesmen at home tremble, all the heads of departments, all the chief clerks, all the copyists in the Foreign Ministry; but since the Minister ignored the matter to the point of not even considering the possible use of the veto, I was forced to think about if for him. Suppose Albani had by chance been named Pope, what would have happened to me? I would have been consigned to oblivion as a politician.

I say this not for myself who care little for fame as a politician, but for future generations of writers to whom rumours of my mishap would carry and who would expiate my misfortune at the expense of their careers, as they whip his scapegoat (menin) when Monsieur the Dauphin has made a mistake. But my daring foresight, in taking the letter of exclusion upon myself, should not be admired over-much; what seemed an enormity, measured on the petty scale of ancient diplomatic thinking, was at bottom nothing at all in the order of actual society. That daring arose, on the one hand, from my insensibility to all disgrace, and on the other from my knowledge of current opinion: the world such as it is constituted today does not give two sous for the nomination of a pope, the rivalry of courts and the intrigues inside a Conclave.

Despatch to Monsieur le Comte Portalis

‘Confidential.

Rome, this 2nd of April 1829.

Monsieur le Comte,

I have the honour to send you today the important documents which I told you of. They are nothing less than the official and private diary of the Conclave. They are translated word for word from the original Italian; I have only removed anything that might indicate too precisely the sources I have obtained them from. If the least part of these revelations, which are perhaps unique, ever gets out, it would cost the fortunes, freedom and lives of several individuals. That would be all the more regrettable in that these revelations are not the result of interest or corruption but are owed to confidence in French honour. These items then, Monsieur le Comte, must remain forever secret, after they have been read in the King’s council: for, despite the precautions I have taken to suppress the names and remove direct references, there is still enough in them to compromise their originators. I enclose a commentary, in order to aid in reading. The Pontifical government is accustomed to keeping a register where decisions, gestures and actions are noted from day to day, and so to speak from hour to hour; what historical riches if one searched among them back to the first centuries of the Papacy! It has been half-opened to me for an instant of time now. The King will see, from the documents I send you, what has never been seen before, the internal workings of a Conclave; the most intimate sentiments of the court of Rome may be known from it, and thus His Majesty’s ministers will not work in the dark.

The commentary on the diary, which I have written, frees me from any further reflection, and it only remains for me to offer you fresh assurance of the high consideration with which I have the honour, etc, etc.’

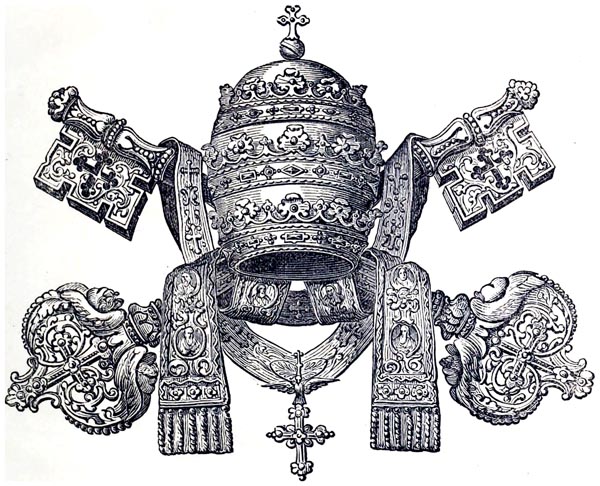

The Lives and Times of the Roman Pontiffs from St. Peter to Pius IX - Alexis Francois Artaud de Montor, William Hayes Neligan (p6, 1866)

Internet Archive Book Images

The original Italian of the precious document mentioned in this confidential despatch was burnt before my eyes here in Rome; I have kept no copy of the translation of the document which I sent to the Foreign Ministry, I have only a copy of the commentary or the remarks enclosed with the translation. But the same discretion which made me recommend that the Minister keep the documents forever secret obliges me to suppress my own remarks here; since, whatever the obscurity those remarks are enveloped in, due to the absence of the document to which they refer, that obscurity would still be penetrable in Rome. Now, resentment endures in the Eternal City; it might be that fifty years from now they would attack some great-nephew of the authors of this mysterious confidence. I will therefore content myself with giving a general survey of the contents of the commentary, stressing those passages which directly relate to the affairs of France.

Firstly one can see how the court of Naples deceived Monsieur de Blacas, or how it was itself deceived; for, while I was being told that the Neapolitan Cardinals would vote with us, they joined with the minority or Sardinian faction.

The minority of Cardinals imagined that the vote of the French Cardinals would have an influence on the shape of our government. How could that be? Apparently because of the secret orders with which they assumed they had been entrusted and because of their votes in favour of an extremist Pope.

Lambruschini, the Nuncio, asserted in Conclave that Cardinal de Latil had the King’s confidence: all the faction’s efforts were aimed at having it believed that Charles X and his government were not in accord.

On the 13th of March, Cardinal de Latil announced that he needed to make a declaration to the Conclave, purely as a matter of conscience; he was sent before four Cardinal-Bishops: the notes of this secret confession remain in the keeping of the Grand-Confessor. The other French Cardinals knew nothing of the contents of the Cardinal’s confession and Cardinal Albani tried in vain to discover them: the action is important and curious.

The minority composed sixteen solid votes. The Cardinals in that minority called themselves the Fathers of the Cross; they set a St Andrew Cross over their doorways to announce that, determined on their choice, they did not wish to discuss it with anyone. The majority of the Conclave displayed reasonable opinions and the firm resolution not to be involved in any way in foreign politics.

The minutes drawn up by the notary to the Conclave are worthy of note: ‘Pius VIII,’ they say in conclusion, ‘was determined to nominate Cardinal Albani as Secretary of State, in order to satisfy the Vienna Cabinet as well.’ The sovereign Pontiff shared the prizes between the two courts; he declared himself as Pope for France, and gave Austria the Secretary of State.

To Madame Récamier

‘Rome, Wednesday the 8th of April 1829.

This very day I gave a dinner for the whole Conclave. Tomorrow I welcome the Grand-Duchess Helen. On Easter Tuesday, I have a ball to celebrate the end of the session; and then I will prepare to come and see you; judge my anxiety; at the instant I write to you, I still have no news of my mounted courier carrying the announcement of the Pope’s death, and yet the new Pope has already been crowned, and Leo XII is forgotten; I have started business with the new Secretary of State Albani; everything goes on as if nothing had happened, and I am not sure if you even know in Paris that there is a new Pontiff! How fine this ceremony of the Papal blessing is! The Sabine Hills on the horizon, then the empty countryside of Rome, then Rome herself, then St Peter’s Square and all the people on their knees beneath an old man’s hand: the Pope is the only Prince who blesses his subjects.

I was thus far with my letter when a courier arriving from Genoa for me brought me a telegraph despatch from Paris to Toulon, which despatch, replying to the one I had sent, tells me that on the 4th of April, at eleven in the morning, my telegraph despatch from Rome to Toulon was received in Paris, the despatch which announced the nomination of Cardinal Castiglioni, and that the King is very pleased.

The rapidity of these communications is prodigious; my courier left on the 31st of March, at eight in the evening, and on the 8th of April, at eight in the evening, I receive a reply from Paris.’

‘11th of April 1829.

Here we are at the 11th of April: in eight days time it will be Easter, in fifteen days my leave will start, and then I will see you! Everything vanishes before that hope; I am no longer sad; I no longer think of Ministers and politics. Tomorrow Holy Week begins. I will think of all you have said to me. If only you were here to listen to the lovely songs of mourning with me! We would go and walk in the wastes of the Roman Campagna, covered now with verdure and flowers. All the ruins seem re-born with the spring; I am one of them.’

‘Holy Wednesday, the 15th of April.

I have left the Sistine Chapel, having been present at Tenebrae and listened to the singing of the Miserere. I remember you speaking to me about that ceremony and because of it I was a hundred times more moved.

The day faded; the shadows slowly covered the Chapel frescoes and one could no longer see the mighty traces of Michelangelo’s brush. The candles, extinguished one by one, allowed a little white smoke to escape from their doused flames, a natural enough symbol of this life that Scripture compares to a little cloud. The Cardinals were kneeling, the new Pope prostrate before the same altar where I had seen his predecessor a few days ago; the fine prayer of penitence and mercy, which followed the Lamentations of the prophet, rose at intervals through the silence and the night. One felt overwhelmed by the great mystery of a God dying to redeem mankind’s sins. The Catholic heritage with all its memories was there, on the seven hills; but, instead of those powerful Pontiffs, those Cardinals who disputed precedence with monarchs, a poor old paralysed Pope, without family or support, princes of a Church lacking in splendour, announced the end of the power which civilised the modern world. The masterpieces of art vanished with it, fading on the walls and vaults of the Vatican, a half deserted palace. Curious foreigners divorced from the unity of the Church, were present in passing at the ceremony and replaced the community of the faithful. A dual sadness gripped the heart. Christian Rome while commemorating the agony of Jesus Christ seemed to be celebrating its own, repeating for the New Jerusalem the words Jeremiah addressed to the Old. It is a fine thing if Rome in order to forget everything, scorns everything and dies.’

BkXXX:Chap6:Sec2

Despatches to Monsieur le Comte Portalis

‘Rome, this 16th of April 1829.

Monsieur le Comte,

Things are developing here, as I had the honour to prophesy to you; the words and actions of the new Sovereign Pontiff are perfectly in accord with the policy of moderation followed by Leo XII: Pius VIII goes further even than his predecessor; he expresses himself with great frankness on the subject of the Charter a word which he does not hesitate to pronounce and counsels the French to follow its spirit. The Nuncio, having continued to write about our affairs, took the order to confine himself to his own badly. Everything has been resolved regarding the Concordat with Holland, and Monsieur le Comte de Celles ends his mission here next month.

Cardinal Albani, in a difficult position, is obliged to make expiation: the protestations he makes me regarding his devotion to France annoy the Austrian Ambassador who cannot hide his ill-humour. As far as religious relations are concerned we have nothing to fear from Cardinal Albani; not very religious himself, he will not trouble us either by his own extremism, or the moderate opinion of his master.

As for political relations, they cannot manipulate Italy today through police intrigue and coded correspondence; let them occupy the legations, or put an Austrian garrison into Ancona on some pretext or other, that would be to stir up Europe and declare war on France: well we are no longer in 1814, 1815, 1816, or 1817; a greedy and unjust ambition cannot be gratified in front of our eyes with impunity. So, Cardinal Albani may receive a pension from Prince von Metternich; he may be a relative of the Duke of Modena, to whom he intends to leave his enormous fortune; he may be spinning some little plot with that prince against the heir to the crown of Sardinia; all that is true, all that would have been dangerous in an age when private and absolute governments might set soldiers on the march in secret, pursuing secret instructions: but today, with public government, with freedom of speech and the Press, with the telegraph and the speed of all communications, with the knowledge of affairs that has spread through every social class, we are protected from the sleights of hand and trickery of the old diplomacy. However, it should not be concealed that an Austrian Chargé d’Affaires, Secretary of State to Rome, presents difficulties; there are certain notes indeed (for example those which related to Imperial power in Italy) which should not be placed in Cardinal Albani’s hands.

No one has yet been able to penetrate the secret of a nomination which displeased everybody, even the Vienna Cabinet. Is it to do with foreign political interests? We are assured that Cardinal Albani is currently offering to advance the Holy Father 200,000 piastres which the government of Rome needs; others claim that the sum was loaned by an Austrian banker. Cardinal Macchi told me last Saturday that His Holiness not wishing to take back Cardinal Bernetti and desiring nevertheless to give him a senior position, could find no other means of arranging the matter than making the Bologna legation available. Wretched embarrassment often provides the motive for the most important decisions. If Cardinal Macchi’s version is true, everything said by Pius VIII to satisfy the courts of France and Austria is no more than a superficial justification, with the aid of which he seeks to hide his own weakness from himself. For the rest, no one thinks Albani’s Ministry will last long. As soon as he opens up relations with the Ambassadors, difficulties will arise on all sides.

As for the state of Italy, Monsieur le Comte, one should read with caution what is said to you by those in Naples or elsewhere. It is unfortunately only too true that the government of the Two Sicilies has fallen into utter contempt. The manner in which the court lives, surrounded by guards, ever-trembling, ever pursued by phantom fears, offering to the view nothing but gibbets and ruinous hunts, is contributing more and more in that country to the debasing of royalty. What are taken for conspiracies are only symptoms of a general malaise, the product of the century, the struggle of the former society with the new, the combat of old decrepit institutions against the energy of the younger generations; ultimately, the comparison everyone makes between what is and what might be. Let us not conceal the fact that the great spectacle of a powerful France, free and happy, that great spectacle striking the eyes of nations remaining or fallen beneath the yoke, excites dismay or nourishes hope. The blend of representative governments and absolute monarchies cannot last; one or the other must perish, so that politics can achieve balance as in Medieval Europe. A frontier-post can no longer separate freedom from slavery; a man can no longer be hung on one side of a river for principles held sacred on the other side of the same river. It is in that sense, Monsieur le Comte, and only in that sense, that there are conspiracies in Italy; it is again in that sense that Italy is French. The day when she begins to enjoy the rights that her enlightened minds perceive and that the march of progress brings towards her, she will be calm and purely Italian. It is not a few poor devils of carbonari, excited by the manoeuvring of the police, and sent to the gallows without mercy, that will rouse this country. Governments gain the most deluded ideas concerning the true state of things; they are prevented from doing what must be done for their own security, by having revealed to them as a specific conspiracy by a pack of Jacobins what is in effect a permanent and general cause.