François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XXIX: Madame Récamier, Rome 1828-1829

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XXIX: Chapter 1: Madame Récamier

- Book XXIX: Chapter 2: The Rome Embassy - Three kinds of material – My Travel Journal

- Book XXIX: Chapter 3: Letters to Madame Récamier

- Book XXIX: Chapter 4: Leo XII and the Cardinals

- Book XXIX: Chapter 5: The Ambassadors

- Book XXIX: Chapter 6: Artists ancient and modern

- Book XXIX: Chapter 7: Past visitors to Rome

- Book XXIX: Chapter 8: The present mode of life in Rome

- Book XXIX: Chapter 9: Surroundings and countryside

- Book XXIX: Chapter 10: A letter to Monsieur Villemain

- Book XXIX: Chapter 11: A letter to Madame Récamier

- Book XXIX: Chapter 12: An explanation of the Memoir you are about to read

- Book XXIX: Chapter 13: Memoir

- Book XXIX: Chapter 14: Letters to Madame Récamier

- Book XXIX: Chapter 15: A despatch

- Book XXIX: Chapter 16: Letters to Madame Récamier

- Book XXIX: Chapter 17: A despatch to Monsieur le Comte Portalis – The death of Leo XII

Book XXIX: Chapter 1: Madame Récamier

(Extracts from the 1839 material excised from the 1847-1848 revision)

BkXXIX:Chap1:Sec1

Before passing on to my Rome Embassy, to that Italy, the dream of my days; before continuing my tale, I ought to speak a little more of that woman who will not be lost from sight throughout the rest of these Memoirs. A correspondence is about to be opened between her and myself: the reader should therefore know more of whom I speak, and how and when I came to know Madame Récamier.

In the various ranks of society she met more or less famous people playing their parts on the world’s stage; all worshipped her; her beauty mingles its ideal existence with the material facts of our history; a serene light illuminating a stormy picture. Let us return once more to time past; and try by the light of my setting sun to sketch a portrait in the heavens, over which an approaching night will soon spread its shadow.

After my return to France in 1800, as I have mentioned, a letter published in the Mercure caught the attention of Madame de Staël. I had not yet been erased from the list of émigrés: Atala drew me from obscurity. Madame Bacciochi (Élisa Bonaparte), at Monsieur Fontane’s request, asked for and obtained the erasure. It was Christian de Lamoignon who introduced me to Madame Récamier; she was living at that time in her elegant mansion on the Rue du Mont-Blanc. Coming from my forests and my obscurity, I was still extremely shy; I scarcely dared raise my eyes to a woman surrounded by admirers, and placed so far above me by her beauty and her fame.

One morning, about a month later, I was at Madame de Staël’s; she received me while she was being dressed by Mademoiselle Olive, during which process she talked to me while toying with a little green twig held between her fingers: suddenly Madame Récamier entered wearing a white dress; she sat down in the centre of a blue silk sofa; Madame de Staël remained standing and continued her conversation, in a very lively manner and speaking quite eloquently; I scarcely replied, my eyes fixed on Madame Récamier. I asked myself whether I was viewing a picture of ingenuousness or voluptuousness. I had never imagined anything to equal her and I was more discouraged than ever; my roused admiration turned to annoyance with myself. I think I begged Heaven to age this angel, to reduce her divinity a little, to set less distance between us. When I dreamed of my Sylph, I endowed myself with all the perfections to please her; when I thought of Madame Récamier I lessened her charms to bring her closer to me: it was clear I loved the reality more than the dream. Madame Récamier left and I did not see her again for twelve years.

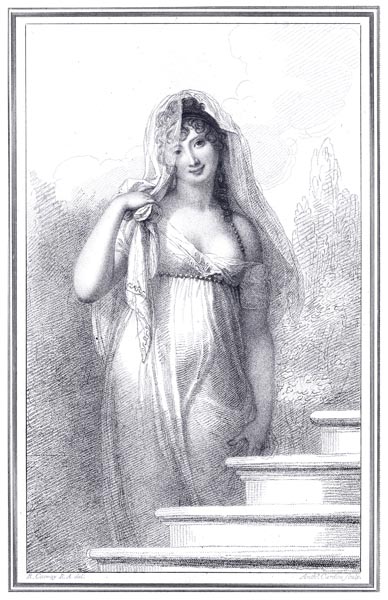

‘Portrait of Jeanne-Françoise Julie Adélaïde Bernard Récamier’

Antoine Cardon, Gaetano Stefano Bartolozzi, Gaetano Stefano Bartolozzi, 1802

The Rijksmuseum

Twelve years! What hostile power culls and wastes our days like this, lavishing them, ironically, on all the indifferent relationships called attachments, on all the wretched things known as joys! Then, in further derision, when it has withered and spent the most precious part of life, returns us to our point of departure. And what state does it return us in? With minds obsessed with strange ideas, importunate phantoms, and false or incomplete feelings for a world which has brought us no lasting happiness. Those ideas, phantoms, feelings interpose between us and the happiness we might still enjoy. We return with hearts ravaged by regret, grieved for our youthful errors, so painful to the memory in the modesty of age. That is how I returned after visiting Rome, and Syria; after watching the passing of an Empire, after becoming a man of the crowd, and ceasing to be a man of solitude and silence, such as I had been when I saw Madame Récamier for the first time. What had she been doing? What had her life been like?

Montaigne says that men go gaping after future things: I am obsessed with gaping at things past. Everything is delight, especially when one turn’s one’s gaze on the childhood years of those one cherishes: one extends a life beloved; one casts the affection one feels over days one has not known, and breathes new life into; one embellishes what was with what is, and rewards youth: moreover one is without apprehension, since one has the experience only for oneself; through the qualities one has discovered there, one knows that the relationship started in that springtime can make no use of its wings and can never wither from its first morning.

In Lyons I saw the Jardin des Plantes established near the amphitheatre in the gardens of the former Abbaye de la Déserte, now demolished: the Rhône and Saône are at your feet; in the distance Europe’s highest mountain rises, the first Roman milestone on the road to Italy, a white signpost above the clouds.

Madame Récamier was placed in that Abbey; she spent her childhood behind its grill, which only opened onto the church beyond at the Elevation of the Host. Then one could see young girls prostrating themselves in the chapel inside the Convent. The Abbess’s name-day was the community’s principal day of celebration; the most beautiful of the girls paid the customary compliments: dressed in her finery, her hair plaited, her head was veiled and crowned by her companions; and all was done without speaking, since the hour of rising was one of those named as an hour of profound silence in the convents. It goes without saying that Juliette had the honours of the day.

Her father and mother, established in Paris, summoned their children to them. With the rough sketches written by Madame Recamier I received this note:

‘On the eve of the day when my aunt came to fetch me, I was led to the Abbess’ room to receive her blessing. On the next day, bathed in tears, I passed through the egress whose door I could not remember opening to allow my entry, and found myself in a carriage with my aunt, and we left for Paris.

I left that time of peace and purity with regret, in order to enter one of anxiety. It comes back to me sometimes like a vague sweet dream with its clouds of incense, its endless ceremony, its processions through the gardens, its hymns and flowers.’

Those hours extracted from a desert of piety, now repose in a different religious solitude, having lost nothing of their freshness and harmony.

BkXXIX:Chap1:Sec2

During the brief Peace of Amiens (1802), Madame Récamier paid a visit to London with her mother.

Such is the power of novelty in England, that the newspapers next morning were full of the arrival of the foreign Beauty. Madame Récamier received visits from everyone to whom she had sent letters. Among these persons the most remarkable was the Duchess of Devonshire, who was then between forty-five and fifty years of age. She was still fashionable and beautiful though she had lost an eye, a fact which she hid with a lock of hair. The first time Madame Récamier appeared in public, it was in her company. The Duchess directed her to her box at the Opera where she met the Prince of Wales, the Duc d’Orléans, and the latter’s brothers the Duc de Montpensier and the Comte de Beaujolais; the first two were to become Kings, one was in reach of the throne, and the other separated from it by the abyss. Lorgnettes and eyes turned towards the Duchess’ box. The Prince of Wales told Madame de Récamier that if she did not want to be stifled she must leave before the end of the performance. She had scarcely risen when the doors of the boxes were flung open: she could not escape and was swept to her carriage by the tide of people.

Next day Madame Récamier went to Kensington Gardens accompanied by the Marquess of Douglas, later Duke of Hamilton, who has since welcomed Charles X to Holyrood, and his sister the Duchess of Somerset. The crowd followed hard on the fair foreigner’s heels. This phenomenon was repeated every time she showed herself in public; the newspapers resounded with her name, and her portrait, engraved by Bartalozzi, was distributed throughout England. The author of Antigone, Monsieur Ballanche, adds that ships carried it as far as the Isles of Greece: beauty returning to the place where its image was invented. We have an unfinished portrait of Madame Récamier by David, a full-length portrait by Gérard, and a bust by Canova. The portrait is Gérard’s masterpiece; it is delightful, but does not please me, because I recognise the features without recognizing the expression of the model.

On the eve of Madame Récamier’s departure, the Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Devonshire asked leave to call on her and bring with them some of their set. Requests multiplying, the assembly was numerous. There was music; Madame Récamier, with the Chevalier Marin, the leading harpist of the day, performed variations on a theme of Mozart, which were dedicated to her. The English newspapers were full of the details of this soirée. They noted the deeply animated and gracious enthusiasm of the Prince of Wales, and his undivided attention to the beautiful foreigner.

The next day she set sail for The Hague, taking three days for a sixteen hour crossing. She told me that during those storm-wracked days, she read Le Génie du Christianisme; I was revealed to her, according to her generous expression: I recognise there the kindness the winds and seas have always shown me.

BkXXIX:Chap1:Sec3

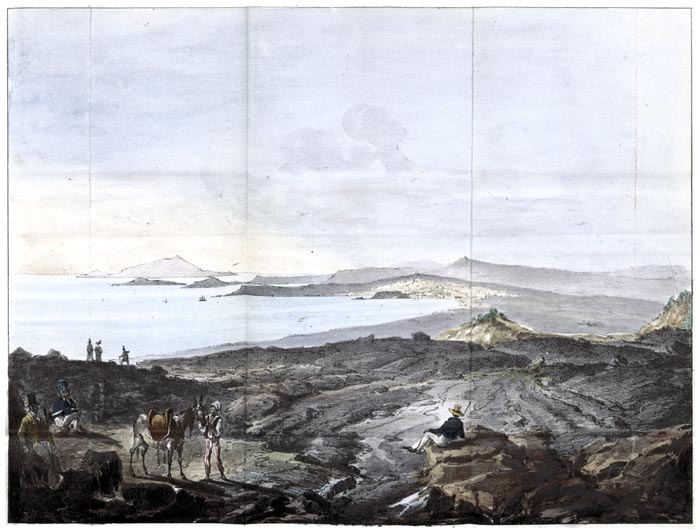

Madame Récamier was in Naples in February 1814; where was I? In the Vallée-aux-Loups, I was beginning the story of my life. I occupied myself writing about my childhood games to the sound of foreign soldiers. The woman whose name should close these Memoirs was wandering the shores of Baiae. Did I have a presentiment of the good which would one day come to me from that land, when I described the seductions of Parthenope in The Martyrs:

‘Each morning, as soon as dawn broke, I went out to the portico. The sun rose in front of me; it illuminated with its gentlest fires the range of hills above Salerno, the blue sea scattered with the white sails of fishing boats, the islands of Capri, Ischia and Procida, Cape Miseno and Baiae with their enchantments.

Flowers and fruits, moist with dew, are less sweet and fresh than the landscape of Naples emerging from the shadows of night. I was always surprised on reaching the portico to find myself at the edge of the sea: since the waves, in that strait, sounded with barely a fountain’s light murmur. Ecstatic before this scene I leant against a pillar, and without thought, desire, or plan, spent whole hours breathing the delicious air. The spell was so deep that it seemed as if that divine air transformed my own substance and that with inexpressible delight I was lifted towards the firmament like a pure spirit.

To wait for beauty or to seek her, to see her approaching on her seashell, and smiling at us from the midst of the waves; to sail with her across the flood, scattering flowers over its surface, to follow the enchantress into the depths of those myrtle groves and to the happy fields where Virgil places his Elysium; such was the occupation of our days.

Perhaps it is a climate dangerous to virtue, because of its extreme sensuousness? Is that not what an ingenious legend would like to tell us, by recounting that Parthenope was built about a Siren’s tomb? At Naples, the velvet brightness of the countryside, the mild temperature of the air, the contours rounding the hills, the soft curves of rivers and valleys, are as seductive to the senses as all peace is.

To escape the heat of midday, we would retire to a section of the Palace built above the sea. Lying there on beds adorned with ivory, we would listen to the murmur of the waves beneath our heads. If some storm surprised us in the depth of our retreat, slaves would light the lamps filled with the most precious nard of Arabia. Then young Neapolitan girls entered bearing roses from Paestum, in vases from Nola: while the waves sounded outside, they sang and performed tranquil dances for us that recalled the Greek style to me: thus the fictions of the poets were realised for us; they might have been the Nereids playing in Neptune’s grotto.’

Reader, if you grow impatient with my quotations, my recitations, firstly reflect that for all I know you might not have read my works, and then that I can no longer hear you; I sleep beneath the soil you tread: if you want me, stamp with your foot on the earth, you can only insult my bones. Consider moreover that my writings were an essential part of that existence whose leaves I scatter for you. Ah! Did not my Neapolitan sketches contain a deeper reality! Was not the daughter of the Rhône the true woman of my imaginary delights! Yet not so: if I was Augustine, Jerome, Eudore, I was so alone; my days in Italy preceded those of Corinne’s friend: how fortunate I would have been if they had always belonged to her! How fortunate if I could have spread my entire life under her feet, like a carpet of flowers! But my life is harsh and its asperities wound me. May at least my last moments be tender towards she who consoles them! May my dying hours reflect back to her the gentleness and charm with which she has filled them, she who has been beloved by all and of whom no one has ever complained!

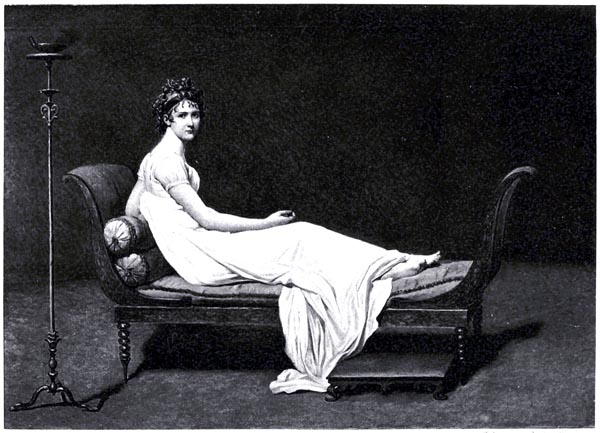

‘Madame Recamier, after Jacques-Louis David’

The Women of the Salons, and other French Portraits - Evelyn Beatrice Hall (p160, 1901)

Internet Archive Book Images

BkXXIX:Chap1:Sec4

It was during a grievous time for France’s glory that I met Madame Récamier again, it was at the time of Madame de Staël’s death in 1817. Returning to Paris after the Hundred Days, the author of Delphine had returned ill; I had seen her since at home, and at Madame de Duras’ house. Gradually as her state worsened she was obliged to keep to her bed. I went to see her one morning in the Rue Royale; the shutters of her windows were two-thirds closed; the bed was against the wall at the far end of the room, leaving only a narrow space on the left: the curtains drawn back on their rods formed two columns at the head of the bed. Madame de Staël was propped up by pillows in a half-sitting position. I approached, and once my eyes were somewhat accustomed to the gloom, I was able to make out the invalid’s features. A feverish flush coloured her cheeks. Her splendid eyes met mine in the shadows, and she said to me: ‘Bonjour, my dear Francis. I am suffering, but that does not prevent me from loving you.’ She held out her hand which I pressed and kissed. As I raised my head, I saw something thin and white rising up on the opposite side of the bed in the space by the wall: it was Monsieur de Rocca, haggard, and hollow-cheeked, with bleary eyes and a sallow complexion: he was dying; I had never seen him before, and I never saw him again. He did not open his mouth; he bowed as he passed me; his footsteps were inaudible: he went away like a shadow. Stopping for a moment at the door, a scrawny figure twisting its fingers, he turned back towards the bed, to wave goodbye to Madame de Staël. Those two spectres gazing at each other in silence, the one pale and erect, the other sitting there flushed with blood that was ready to flow back once more and congeal at the heart, made one shudder.

A few days later, Madame de Staël changed her lodgings. She invited me to dinner at her apartment in the Rue Neuve des Mathurins; I went there. She was not in the drawing-room and was not even able to dine; though she was unaware that the fatal hour was so close. We sat to the table. I found myself placed next to Madame Récamier. It had been twelve years since I had seen her, and then I had only glimpsed her for a moment. I did not look at her; she did not look at me; we did not exchange a single word. When, towards the end of the meal, she timidly addressed a few words to me about Madame de Staël’s illness, I turned my head a little, and raised my eyes, and saw my guardian angel at my right hand.

I should be afraid now to profane with aged lips a feeling which is still young in my memory and whose charm increases as life ebbs away. I draw aside my past years to reveal behind them celestial visions, to hear from the depths of the abyss the harmonies of a happier region.

Madame de Staël died. The last note she wrote to Madame de Duras was traced in big straggling letters like a child’s. It contained an affectionate word for Francis. The death of talent affects us more than the individual who dies: it is a common grief that afflicts society; everyone suffers the same loss at the same instant.

A considerable portion of the age I have lived in vanished with Madame de Staël; such a gap, which the vanishing of a superior intellect makes in a century, cannot be repaired. Her death made a deep impression on me, mingled with a kind of mysterious amazement: it was at that illustrious woman’s house that I had first met Madame Récamier, and after long years of separation it was Madame de Staël once more who brought together two travellers who had become almost strangers to one another: with a funeral banquet she left them a memory of herself and the example of an immortal attachment. I went to see Madame Récamier in the Rue Basse-du-Rempart and later in the Rue d’Anjou. When a man is reunited with his fate, he imagines he has never left it: life according to Pythagoras is merely reminiscence. Who, in the course of his life, does not remember certain little circumstances of no interest to anyone except he who recalls them? The house in the Rue d’Anjou had a garden; in the garden was a lime-tree bower between whose leaves I would see a gleam of moonlight while waiting for Madame Récamier: does it not seem to me now that surely that gleam is mine, and that if I went to that very place I would find it again? Yet I barely remember the sun I have seen shining on so many brows.

‘Madame de Staël, after François Gérard’

The Women of the Salons, and other French Portraits - Evelyn Beatrice Hall (p137, 1901)

Internet Archive Book Images

BkXXIX:Chap1:Sec5

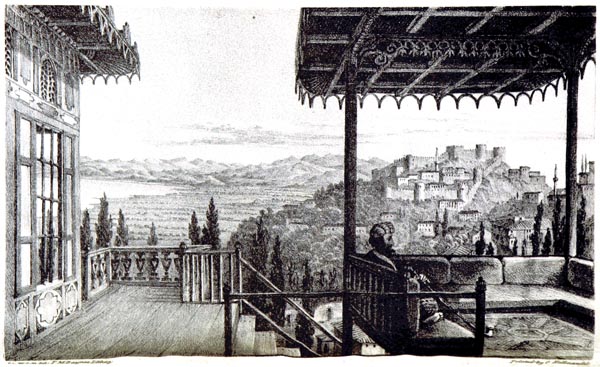

It was at that time that I was obliged to sell the Vallée-aux-Loupes, which Madame Récamier rented, going halves with Monsieur de Montmorency. Increasingly tried by fate, Madame Récamier retired to the Abbaye-aux-Bois. A dark corridor connected two little rooms; I maintained that this hallway was lit by a gentle light. The bedroom was furnished with a bookcase, a harp, a piano, a portrait of Madame de Staël, and a view of Coppet by moonlight. On the window sills were pots of flowers.

When, breathless after climbing three flights of stairs, I entered this little cell as dusk was falling, I was entranced. The windows looked out over the Abbaye garden, around the green enclosure of which the nuns made circuits, and in which the schoolgirls ran about. The summit of an acacia tree reached to eye-level and the hills of Sèvres could be seen on the horizon. The setting sun gilded the picture and entered through the open windows. Madame Récamier would be at the piano; the Angelus would toll; the notes of the bell, which seemed to mourn the dying day: ‘il giorno pianger che si more’, mingled with the final accents of the invocation to the night from Steibelt’s Romeo and Juliet. A few birds would come and settle on the raised window-blinds. I would merge with the distant silence and solitude, above the noise and tumult of a great city.

‘Juliet’

The Stratford Gallery - Henrietta L. Palmer (p29, 1859)

Internet Archive Book Images

God, in giving me these hours of calm, compensated me for my hours of trouble; I caught a glimpse of the future peace which my faith believes in and my hopes invoke. Worried as I was elsewhere by political affairs, or disgusted by the ingratitude of the Court, tranquillity of heart awaited me in the depths of that retreat, like the coolness of the woods on leaving a scorching plain. I recovered my calm beside a woman who spread serenity around her, without it being too level a tranquillity, for it passed among profound affections. Alas! The men whom I used to meet at Madame Récamier’s, Mathieu de Montmorency, Camille Jordan, Benjamin Constant, the Duc de Laval have gone to join Hingant, Joubert, Fontanes, other absentees of an absent company. Among that succession of friendships other young friends arose, springtime shoots in an old forest where the felling is eternal. I ask of them, I ask of Monsieur Ampère, who will happily take my place when I am gone, and who will read this in editing my proofs, I ask them one and all to preserve a memory of me: I hand them the thread of a life whose end Lachesis is loosing from the spindle. My inseparable friend on the road, Monsieur Ballanche, finds himself alone at the end of my career as he was at the beginning; he has been the witness of my friendships severed by time, as I have been witness to his swept away by the Rhône. Rivers always undermine their banks.

My friends’ misfortunes have often weighed on me and I have never shirked those sacred burdens: the moment of reward has arrived: a serious attachment deigns to help me bear whatever their weight adds to wretched days. Approaching my end, it seems to me that all I have loved I have loved in Madame Récamier, and that she was the hidden source of all my affections. My memories of various times, those of my dreams, as well as those of my realities, have been kneaded together, blended to make a compound of charms and sweet sufferings, of which she has become the visible form. She rules over my feelings, in the same way that Heaven’s authority has brought happiness, order and peace to my duties.

I have followed the fair traveller along the path she has trodden so lightly; I will soon go before her to a new country. Wandering through these Memoirs, through the passages of this Basilica I am hastening to complete, she may come across this chapel which I dedicate to her; it may please her perhaps to rest here a moment: I have placed her image here.

Book XXIX: Chapter 2: The Rome Embassy - Three kinds of material – My Travel Journal

BkXXIX:Chap2:Sec1

What I have just written in 1839 of Madame de Staël and Madame Récamier is linked to this book concerning my Embassy in Rome written in 1828 and 1829, ten years ago. I have introduced the reader to a little circuitous by-way of the Empire, while that Empire continued its common progress; I now find myself led on to my Rome Embassy. There is abundant material for this book. It is of three kinds:

The first contains the history of my intimate feelings and my private life as related in letters addressed to Madame Récamier.

The second reveals my public life; in my despatches.

The third is a mixture of historical details on the Papacy, the ancient society of Rome, the changes in that society from century to century, etc.

Among these investigations are thoughts and descriptions, the fruit of my walks. It was all written in the space of seven months, during the period of my Embassy, in the midst of celebrations and serious affairs (in re-reading these manuscripts I have only added a few passages from works published after the date of my Rome Embassy). However, my health had altered: I could not raise my eyes without experiencing dizziness; to admire the sky, I was forced to place it on my own level, by ascending the heights of a Palace or a hillside. But I countered weariness of the body by applying the spirit: exercising my mind renewed my physical strength; what might have killed another man gave me life.

In seeing it all again, one thing struck me: on my arrival in the Eternal City, I felt a certain displeasure, and I thought for a while that everything had changed; little by little the fever for ruins gripped me, and I ended, like a thousand other travellers, by adoring what had at first left me cold. Nostalgia is regret for one’s native land: on the banks of the Tiber one also feels home sickness, but it produces an opposite effect to its customary one: you are seized with a love for solitude and disgust with your homeland. I had already experienced that sickness during my first journey, and could have said:

‘Agnosco verteris vestigia flammae:

I recognise the traces of the ancient flame.’

You know that on the formation of Martignac’s government the name of Italy alone had rid me of my remaining objections; but I am never sure of my moods in matters of pleasure: I had no sooner parted from Madame de Chateaubriand than my innate melancholy met me on the road. You can persuade yourself of that from my travel journal.

TRAVEL JOURNAL

‘Lausanne, 22nd September 1828.

I left Paris on the 14th of this month; I spent the 15th at Villeneuve-sur-Yonne; what memories! Joubert is gone; the deserted Château of Passy has changed ownership; it has been said: ‘Be the cicada in the night. Esto cicada noctium’.

‘Arona, 27th of September.

Arriving at Lausanne on the 20th, I have followed the route along which two other women who wished me well have vanished, and who, in the order of things should have survived me: the one, Madame la Marquise de Custine, has recently died at Bex, the other, Madame la Duchesse de Duras, not a year ago, hastened to Simplon, fleeing the death which came to her at Nice.

“Noble Clara, worthy, constant friend,

Your memory here’s no more alive:

From this grave they turn their eyes:

The world forgets, and your name has end!”

The last letter I received from Madame de Duras is full of the bitterness of that last taste of life which is bound to weary us all:

“Nice, 14th November 1827.

I have sent you an asclepias carnata: it is a ‘laurel’ growing on open ground which tolerates cold and has a red flower like a camellia, with an excellent scent; place it beneath the Benedictine’s library window.

I will give you a little of my news: it is always the same; I languish on my sofa all day, that is to say whenever I am not in my carriage or walking out; which I can’t do for more than a half-hour. I dream of the past; my life has been so restless, so varied, that I cannot say I experience any great boredom: if I could only sew or work on my tapestry, I would not consider myself unfortunate. My present existence is so remote from my past existence, that it seems to me as if I were reading my memoirs or watching a play.”

Thus, I have returned to Italy, deprived of means, just as I left it twenty-five years ago. But in those days I could repair my losses, now who would wish to associate with old age? No one cares to inhabit a ruin.

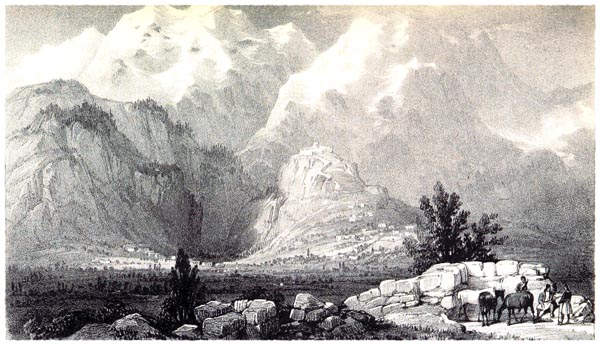

In that very town of Simplon I saw the first smile of a happy dawn. The rocks, whose blackened base stretched to my feet, shone rose-red to the summits of the mountains, struck by the sun’s rays. To leave the shadows it is enough to raise oneself towards the Heavens.

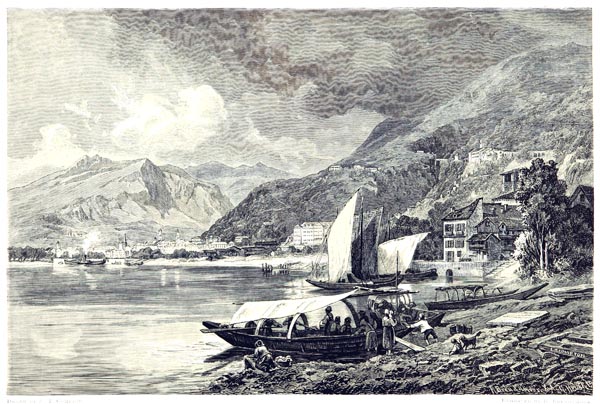

If Italy had lost its lustre for me since my trip to Verona in 1822, in this year of 1828 it seemed even more faded; I was measuring the passage of time. Leaning on the balcony of an inn at Arona, I gazed at the shores of Lake Maggiore, painted with gold by the setting sun and rimmed with azure waves. Nothing could be as lovely as that landscape edged with the castle’s crenellations. The spectacle invoked in me neither pleasure nor sentiment. Our younger years are mingled with glimpses of hope; a young man wanders with what he loves, or with memories of absent happiness. If he has no close ties, he seeks them; he convinces himself he has found something at every step; joyful thoughts pursue him: the disposition of his soul is reflected in the objects around him.

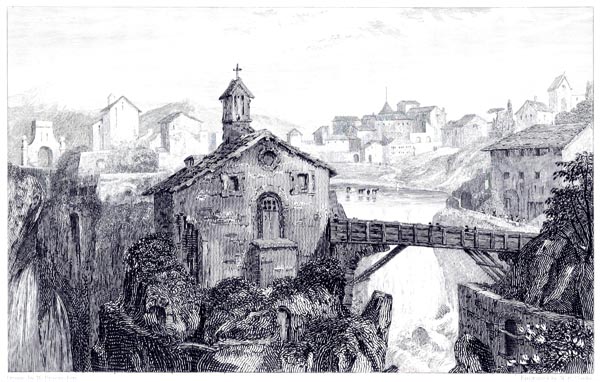

‘Locano on the Lago Maggiore’

Switzerland: its Scenery and People - Theodor Gsell Fels (p577, 1881)

The British Library

Moreover, I feel the diminishment of present society less when I am alone. Left to the solitude in which Bonaparte has left the world, I scarcely hear the feeble generations who pass by wailing at the edge of the wilderness.’

‘Bologna, 28th of September 1828.

At Milan, in less than a quarter of an hour, I counted seventeen hunchbacks passing beneath the window of my inn. German punishments have deformed young Italy.

I saw St Charles Borromeo in his tomb whose cradle I had touched at Arona. He had been dead for two hundred and forty four years. He was not lovely to look on.

‘San Carlo Borromeo’

Attributed to Francesco Furini, 1604 - 1646

The Rijksmuseum

At Borgo San Donnino, Madame de Chateaubriand rushed into my room in the middle of the night; she had seen her clothes and her straw hat fall from the chairs from which they were hanging. She was convinced we were in an inn haunted by ghosts or inhabited by thieves. I had not experienced any disturbance in bed: yet it is true that an earthquake was felt in the Apennines: what overthrows cities could certainly make a woman’s clothes fall to the floor. That’s what I told Madame de Chateaubriand; I also told her that in Spain, in the Vega of the Xenil, I had passed through a village demolished the previous day by a subterranean shock. These noble attempts at consolation had little success, and we hastened to leave that assassins’ cave.

The remainder of my journey everywhere revealed the transience of men and the inconstancy of fortune. At Parma, I found a portrait of Napoleon’s widow; that daughter of the Caesars is now the wife of Count von Neipperg; mother of the conqueror’s son, she has given that son brothers; she guaranteed the heavy debts she had incurred by means of a little Bourbon who was given Lucca, and who if it came to it would inherit the Duchy of Parma.

Bologna seemed less deserted to me than at the time of my first trip. I was received there with the honours with which one astounds Ambassadors. I visited a fine cemetery: I never forget the dead; they are family.

I have never admired Carrachi so much as in the new gallery in Bologna. I thought I was seeing Raphael’s St Cecilia for the first time she was so much more divine than in the Louvre, under our soot-daubed sky.’

‘Annibale Carracci 1560-1609. Virgin and Sleeping Child (Louvre)’

A History of Painting...with a Preface by Frank Brangwyn - Haldane Macfall (p68, 1911)

Internet Archive Book Images

BkXXIX:Chap2:Sec2

‘Ravenna, 1st October 1828.

In the Romagna, a countryside which I did not know, a multitude of towns, their houses coated with whitewash, are perched on the heights of little hills like flocks of white pigeons. Each of these towns offers you masterpieces of modern art or ancient monuments. This region of Italy contains all Roman history; you need to travel it with Livy, Tacitus and Suetonius in hand.

I passed through Imola, the diocese of Pius VII, and Faenza. At Forlì I made a detour to visit Dante’s tomb in Ravenna. Approaching the monument, I was seized by that thrill of admiration a great name inspires, when the owner of that name was subject to misfortune. Alfieri, who betrayed on his brow the pallor of death and its hope, prostrated himself on the marble floor and addressed a sonnet to him: “O gran padre Alighier!” Before the tomb I considered the appropriateness of these lines from the Purgatorio:

“Frate,

Lo mondo è cieco, e tu vien ben da lui.

Brother,

the world is blind, and truly you come from there.”

Beatrice appeared to me; I saw here as she was when she inspired in her poet the desire to sigh and die of weeping: di sospare, e di morir di pinato.

“My sorrowful canzone,” says the father of the modern Muse, “now go weeping: and find the ladies, and young ladies, to whom your sisters used to bring delight: and you, who are the daughter of my sadness, go, disconsolate, to be with them.”

‘Dante and Beatrice. Photogravure from the Original Painting by Henry Holiday’

The Divine comedy of Dante Alighieri - Dante Alighieri, Henry Francis Cary (p321, 1901)

Internet Archive Book Images

And yet the creator of a new world of poetry forgot Beatrice when she had left the earth; he did not find her again, to adore her with the power of his genius, until he was disillusioned. Beatrice reproached him, as she prepared to show her lover the Heavens: “For a while I supported him,” she told the angels of Paradise, “with my face: showing him my young eyes. but, as soon as I was on the threshold of my second age, and changed existences, he left me and gave himself to others.”

Dante refused to return to his city at the cost of an apology. He replied to one of his relatives: “If in order to return to Florence there is no other road open to me than that, I will not return. I can contemplate the sun and stars anywhere.” Dante denied himself to the Florentines, and Ravenna has denied them his ashes, even though Michelangelo, the risen spirit of the poet, promised to adorn for Florence the funeral monument of one who had learnt how man makes himself eternal.

The painter of the Last Judgement, the sculptor of Moses, the architect of the Dome of St Peter’s, the engineer of the old bastion of Florence, the poet of the Sonnets addressed to Dante, joined with his compatriots and supported the request he presented to Leo X with these words: “Io, Michel Angolo, scultore, il medesimo a Vostra Santità supplico, offerendomi al divin poeta fare la sepoltura sua condecente e in loco onorevole in questa citta.”

Michelangelo, whose chisel was deceived in its expectations, had recourse to his crayon to raise a different mausoleum to the author himself. He drew the principal subjects of the Divine Comedy on the margins of a folio copy of the great poet’s works; a ship, which was carrying this doubly-precious monument from Livorno to Civita-Vecchia, was wrecked.

I was returning, deeply moved, and feeling something of that confusion mixed with divine terror that I experienced in Jerusalem, when my cicerone proposed to take me to Lord Byron’s house. Ah! What did Childe Harold and Signora Guiccioli matter to me in the presence of Dante and Beatrice! Childe-Harold still lacks misfortune and the centuries; let him wait on the future. Byron was poorly inspired in hisProphecy of Dante.

I found Constantinople again in San Vitale and Sant’ Apollinaire. Honorius and his chicken did not impress me; I preferred Placidia and her adventures, the memory of which returned to me in the Basilica of St John the Evangelist; it is a Roman amongst the Barbarians. Theodoric is still great, though he had Boetius killed. Those Goths were of a superior race; Amalasuntha, banished to an island in Lake Bolsena, with her minister Cassiodorus tried to conserve what remained of Roman civilisation. The Exarchs brought Ravenna the decadence of their Empire. Ravenna was Lombard under Aistulf; the Carolingians returned it to Rome. It became subject to its Archbishop then changed finally into a Republic under a tyrant, having been Guelph and Ghibilline by turns; after leaving the Venetian States, it returned to the Church under Julius II, and is only known today because of Dante.

‘San Vitale in Ravenna’

Ährenlese - Carl Vischer-Merian (p45, 1893)

The British Library

This city, that Rome gave birth to in its old age, inherited something of its mother’s antiquity. All in all, I would like living there; I would enjoy visiting the French Column, erected in memory of the Battle of Ravenna. Cardinal de Medici (Leo X) was present, with Ariosto, Bayard and Lautrec, the brother of the Comtesse de Chateaubriand. There at the age of twenty-four died the handsome Gaston de Foix: “Notwithstanding the weight of Spanish artillery fire, the French continued to advance,” says the Loyal Serviteur; “since God created Heaven and Earth, there was never a harsher or crueller encounter between the French and the Spanish. They rested opposite each other to recover their breath; then, lowering their visors they recommenced more fiercely, shouting out for France and Spain!” Only a handful of knights remained of so many warriors, who, stamped with the mark of glory, then took Holy Orders.

In some cottage there you might have seen a young girl turning her spindle, her delicate fingers entangled in the hemp; she was not accustomed to such a life; she was a Trivulce. When through her half-open door she saw two waves meet in the flood’s expanse, she felt her sadness grow: the woman had been loved by a great King. She continued to wander sadly, through her isolated island, from her cottage to an abandoned church and from that church to her cottage.

The ancient forest I travelled through was composed of forlorn-looking pine-trees; they resembled the masts of galleys beached on the sand. The sun was near to setting when I left Ravenna; I heard the distant sound of a bell ringing: it was summoning the faithful to prayer.’

BkXXIX:Chap2:Sec3

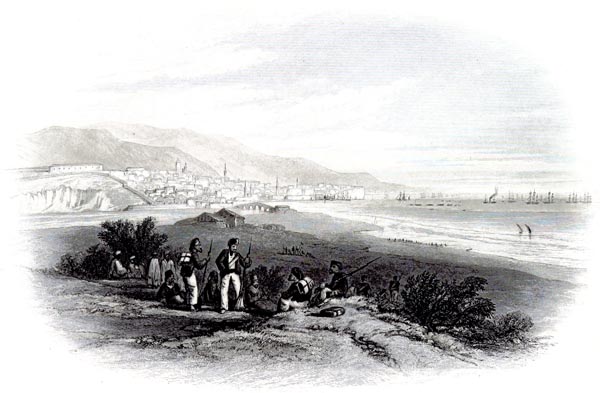

‘Ancona, 3rd and 4th of October.

Returning to Forlì, I have left it again without having seen the place on the crumbling ramparts where the Duchess Caterina Sforza declared to her enemies, who were ready to cut the throat of her only son, that she could yet be a mother. Pius VII, born at Cesena, was a monk in the fine monastery of Santa Maria del Monte.

Near Savignano I traversed a little torrent in a ravine: when I was told that I had crossed the Rubicon, it was as though a veil had lifted and I saw the world in Caesar’s time. My Rubicon is life: a long time ago I left its shore behind.

At Rimini I found neither Francesca, nor the other shade her companion, who seemed so light upon the wind:

“E paion sì al vento esser leggieri”

Rimini, Pesaro, Fano and Sinigaglia led me to Ancona over bridges and roads left to us by Augustus. In Ancona today they are celebrating the Pope’s crowning; I can hear music being played near the triumphal arch of Trajan: double sovereignty of the Eternal City.’

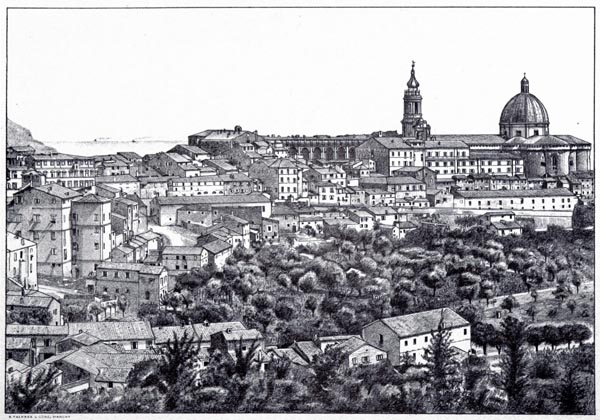

‘Loreto, 5th and 6th October.

We arrived to spend the night in Loreto. The place offers a perfectly preserved specimen of a Roman colony. The peasant farmers of Notre-Dame are affluent and appear happy; the peasant women are pretty and lively, wearing a flower in their hair. The Governing-Prelate has offered us hospitality. From the tops of the bell-towers and the summits of various heights in the town, there are sunlit views of the countryside, Ancona and the sea. In the evening we had a storm. I enjoyed seeing the valentia muralis and the goats’ fumitory bowing to the wind on the old walls. I walked beneath the second floor galleries, erected after designs by Bramante. These pavements will be drenched by autumn rain; these blades of grass will quiver in the Adriatic breeze, long after I have passed.

‘Loreto’

A Pilgrimage to the Shrine of Our Lady of Loreto - George Falkner (p18, 1882)

The British Library

At midnight I retired to a bed eight foot square, consecrated by Napoleon; a night light barely illuminated the gloom of my chamber; suddenly a little door opened, and I witnessed the mysterious entry of a man leading a veiled woman. I raised myself on my elbows and looked at him; he approached my bed and hastened, while bowing to the ground, to offer a thousand excuses for thus disturbing the Ambassador’s repose: but he is a widower; he is a poor steward; he desires to marry off his ragazza (daughter), she is here: unfortunately he lacks means to provide a dowry. He raised the orphan’s veil: she was pale, very pretty, and kept her eyes lowered in appropriate modesty. This father of the family had the air of one wishing to depart, leaving the intended to complete the story. In this pressing danger, I did not ask the obliging unfortunate, as the good knight asked the mother of the young girl at Grenoble, if she was a virgin; quite ruffled I took a few pieces of gold from my bedside table and gave them, in honour of the King my master, to the zitella (maid) whose eyes were not swollen with weeping. She kissed my hand in infinite gratitude. I said not a word, and as I lay down again on my immense couch, as if I wished to sleep, the vision of St Anthony vanished. I thanked my patron saint Francis whose day it was; I dozed in the gloom half-smiling, half-regretful, and with profound admiration for my restraint.

It was thus that I scattered gold once more, as the Ambassador, lodged in style in the residence of the Governor of Loreto, in that same town where Tasso stayed in a foul hovel and where, for lack of cash, he could not continue his journey. He paid his debt to Our Lady of Loreto with his canzone:

“Ecco fra le tempeste e i fieri venti: Here in the storm and wild winds”

Madame de Chateaubriand made amends for my passing fortune, by mounting the steps of Santa Chiesa on her knees. After my night-time victory, I would have had a greater right than the King of Saxony to deposit my wedding suit in the Loreto treasury; but I can never forgive myself, I a feeble child of the Muses, for having been so powerful and so happy, there where the singer of Jerusalem Delivered had been so weak and wretched! Torquato, do not consider me in this unusual moment of prosperity; wealth is not natural to me; consider me on my journey to Namur, in my garret in London, in my Paris Infirmary, in order to discover some distant resemblance between us.

I did not, as Montaigne did, leave my portrait in silver in Our Lady of Loreto, nor that of my daughter, Leonora Montana, filia unica: Léonore de Montaigne, our only child; I have never desired to perpetuate myself: and yet a daughter, and one bearing the name Léonore!’

‘Spoleto.

After leaving Loreto, passing through Macerata, and leaving Tolentino behind which marked Bonaparte’s track and recalled a treaty, I climbed the last salient of the Apennines. The mountain plateau is moist and cultivated like a hop-field. On the left were Greek waters, on the right those of Spain; the breath of wind which blew against me might be one I had breathed in Athens or Granada. We descended towards Umbria, spiralling down through gorges stripped of leaves where the descendants of those mountaineers who furnished soldiers for Rome after the battle of Lake Trasimene are suspended among the thickets.

Foligno possessed a Madonna by Raphael which is now in the Vatican. Vene, in a delightful position, is at the source of the Clitumnus. Poussin has painted the site tenderly and warmly; Byron has sung it coldly.

Spoleto is where the current Pope saw the light. According to my courier Giorgini, Leo XII had settled convicts in this town to honour his birthplace. Spoleto dared to resist Hannibal. She displays several works by Filippo Lippi, who, nurtured in the cloister, a Barbary slave, a kind of Cervantes among painters, died at sixty of poison given him by the relatives of Lucrezia Buti, who was seduced by him, they say.’

‘Civita Castellana.

At Monte-Luco, Count Potocki buried himself among delightful laurels; but did not thoughts of Rome follow him there? Did he not think himself transported into the midst of choirs of young girls? And I too, like St Jerome, “I have spent the day and the night uttering cries, striking my breast until the moment God gave me peace.” I regret no longer being what I was, plango me non esse quod fuerim.

Having passed the hermitages of Monte Luco, we began to skirt Somma. I had already taken this road on my first trip from Florence to Rome via Perugia, accompanying a dying woman.

From the nature of the light and a sort of freshness in the landscape, I might have thought I was one on of those rounded tops of the Alleghanies, it was merely a lofty aqueduct, surmounted by a narrow bridge, that recalled a Roman construction, to which the Lombards of Spoleto had set their hand: the Americans have not yet created those monuments which follow the achievement of liberty. I climbed to Somma on foot, with the oxen of Clitumnus which were leading Madame the Ambassadress to her triumph. A lean young goat-girl, as light and nimble as her nanny-goat, followed me, with her little brother, asking for carita (charity) in that opulent landscape: I gave her alms in memory of Madame de Beaumont whom these places no longer remembered.

“Alas, regardless of their doom,

The little victims play!

No sense have they of ills to come,

Nor care beyond to-day.”

I found Terni again and its waterfalls. A countryside planted with olive-trees led me to Narni; then, passing through Otricoli, we came to a halt at mournful Civita Castellana. I would have preferred to go to Santa Maria di Falleri to see a town which is no more than the shell of its walls: it is a void within: wretched humanity brought to God. My moment of grandeur past, I will return to find the city of the Falisci. From Nero’s tomb, I was soon pointing out the cross on St Peter’s, to my wife, which dominates the city of the Caesars.’

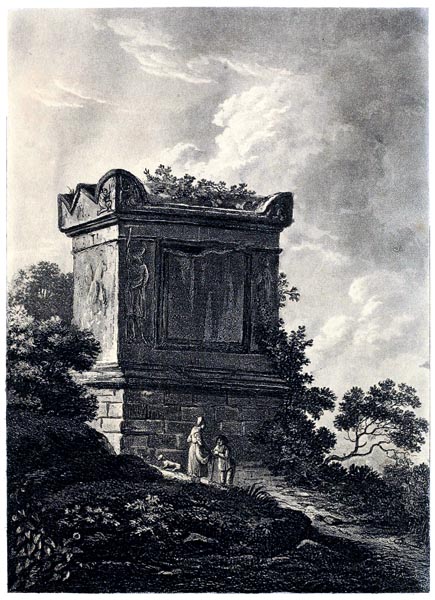

‘Tomb of P. Vibius Mariaiius, “Tomb of Nero”’

A Select Collection of Views and Ruins in Rome and its Vicinity: Recently Executed from Drawings Made Upon the Spot - J Mérigot (p94, 1815)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XXIX: Chapter 3: Letters to Madame Récamier

BkXXIX:Chap3:Sec1

You have just skimmed through my travel journal; now you can read my letters to Madame Récamier, intermingled, as I have previously said, with pages of history.

In parallel you can peruse my despatches, here. Visible especially distinctly at this time are the two men who exist within me.

To Madame Récamier

‘Rome, this 11th of October 1828..

I have traversed this beautiful country, filled with the memory of you; it consoles me, without eliminating the sadness of all the other memories I encounter again at every step. I have seen that Adriatic once more which I crossed more than twenty years ago, and in what state of mind! At Terni, I had once halted with a poor dying woman. At last I have reached Rome. Its monuments, after those of Athens, as I feared, seem less perfect to me. My memory of places, astonishing and painful at the time, has not allowed me to forget a single stone..

I have not yet seen a soul, except the Secretary of State, Cardinal Bernetti. To have someone to talk to, I went to find Guérin, yesterday at sunset: he seemed delighted with my visit. We opened a window on Rome and admired the horizon. It is the only thing which remains, for me, as I saw it: my eyes or the objects of them have changed; perhaps both.’

Book XXIX: Chapter 4: Leo XII and the Cardinals

BkXXIX:Chap4:Sec1

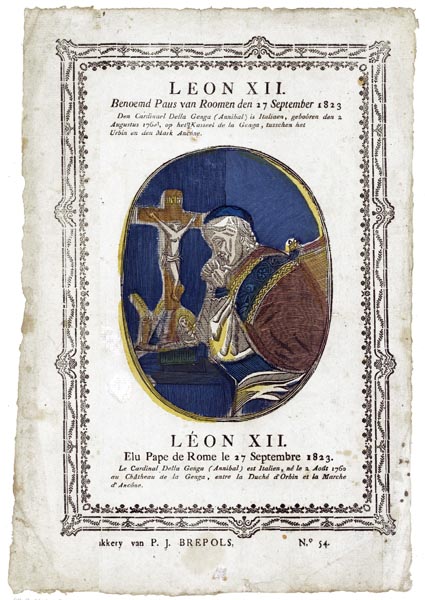

The first hours of my stay in Rome were employed on official visits. His Holiness received me in private audience; public audiences are no longer entertained and cost too much. Leo XII, a very tall prince with an air both serene and sad, was dressed in a simple white cassock; he eschewed splendour and occupied a humble room, almost devoid of marble. He hardly ate; with his cat, he lived on a little polenta. He considered himself very ill and watched himself wither away with a resignation filled with Christian joy: like Benedict XIV he chose to store his coffin beneath his bed. Reaching the door of the Pope’s apartments, an Abbé led me through dark corridors to His Holiness’ refuge or sanctuary. He had not allowed himself time to dress, for fear of keeping me waiting; he rose, came towards me, would not allow me to kneel to kiss the border of his robe instead of his slipper, and led me by the hand to a seat placed to the right of his humble armchair. Once seated, we talked.

On Monday, at seven in the morning, I went to see the Secretary of State, Bernetti, a man of business and pleasure. He was a close friend of Princess Doria; he knew his century and only accepted the Cardinal’s hat with reluctance. He had refused to enter the Church, was only certified as a sub-deacon, and could marry tomorrow by relinquishing his hat. He believed in revolutions and went so far as to consider that, if he lived long enough, he had the possibility of seeing the temporal fall of the Papacy.

The Cardinals are divided into three factions:

The first is composed of those who seek to advance with the times and among whom are Benvenuti and Opizzoni. Benvenuti is famous for his elimination of brigandage and his mission to Ravenna after Cardinal Rivarola; Opizzoni, Archbishop of Bologna, is reconciled to the diverse opinions in that industrial and literary city which is difficult to govern.

The second faction is formed of the zelanti, who are attempting to reverse things: one of their leaders is Cardinal Odescalchi.

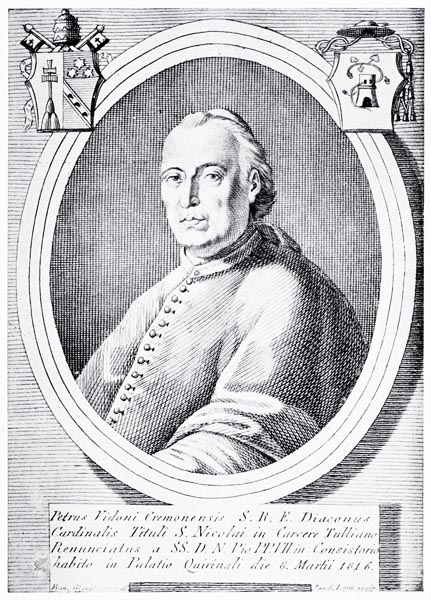

Finally the third faction covers those who are set in place, the elderly who do not wish to, or cannot, go forwards or backwards: among these old men one finds Cardinal Vidoni, a kind of policeman for the Treaty of Tolentino: tall and fat, shiny-faced, cap askew. When he was told he had a chance of the Papacy, he replied: Lo santo Spirito sarebbe dunque ubriaco: the Holy Spirit must have been drinking then! He is planting trees by the Milvian Bridge, where Constantine made the Christian world. I see the trees when I leave Rome by the Porto del Populo and re-enter by the Porto Angelica. From the far distance the Cardinal calls out on seeing me: Ah! Ah! Signor ambasciadore di Francia! Then he rages at the planters of pines. He does not follow Cardinals’ etiquette; he is accompanied by a single lackey in a carriage when he pleases: one excuses all, by calling him Madama Vidoni. (When I left Rome he bought my calash and did me the honour of dying in it on his way to the Milvian Bridge. Note: Paris, 1836)

‘Effigie del Card, Pietro Vidoni III’

Il Palazzo Vidoni in Roma Appartenente al Conte Filippo Vitali: Monografia Storica con Illustrazioni - Giuseppe Tomassetti (p54, 1905)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book XXIX: Chapter 5: The Ambassadors

BkXXIX:Chap5:Sec1

My ambassadorial colleagues are Count Lutzow, the Austrian Ambassador, a very polite gentleman: his wife sings well, always the same air, and talks endlessly about her little ones; the learned Baron Bunsen, Prussian minister and friend of Niebuhr (I am negotiating with him the termination in my favour of the lease on his Palace on the Capitoline); and the Russian minister, Prince Gagarin, exiled among the ancient grandeurs of Rome, because of a transient affair: if he was preferred by the beautiful Madame Narishkin, living for the moment in my former hermitage of Aulnay she must have found some charm in his moodiness; one dominates more by one’s faults than one’s qualities.

Monsieur de Labrador, the Spanish Ambassador, a loyal gentleman, speaks little, walks alone, and thinks a great deal, or does not think at all, which one I can’t quite make out.

Old Count Fuscaldo represents Naples as winter represents spring. He has a large piece of cardboard which he studies through his spectacles, showing not the rose-fields of Paestum, but the names of foreign suspects to whom he must not issue passports. I envy him his Palace (Farnese), a fine unfinished structure, which Michelangelo crowned, which Annibale Carraci adorned, aided by his brother Augustino, the portico of which shelters the sarcophagus of Celicilia Metella, which has lost nothing by its change of mausoleum. Fuscaldo, wrecked in mind and body, has, they say, a mistress.

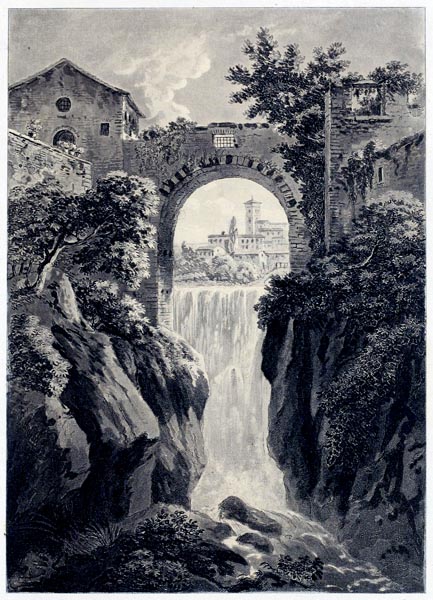

‘The Tomb of Celicilia Metella’

A Select Collection of Views and Ruins in Rome and its Vicinity: Recently Executed from Drawings Made Upon the Spot - J Mérigot (p70, 1815)

Internet Archive Book Images

The Comte de Celles, Ambassador of the King of Holland, married Mademoiselle de Valence, now dead: he has two daughters, who, in consequence, are great grand-daughters of Madame de Genlis. Monsieur de Celles remained a Prefect, because he had been one: his character is that blend of loquacity and petty tyranny, of recruiting officer and quartermaster, which one never loses. If you meet a man to whom, instead of feet, yards and acres, you must speak of decimetres, metres and hectares, you have set hands on a Prefect.

Monsieur de Funchal, semi-official Ambassador of Portugal, is grotesque, agitated, grimacing, green as a Brazilian monkey, yellow as a Lisbon orange; yet he sings the praises of his Negress, this new Camoëns! A great amateur musician, he keeps a sort of Paganini in his pay, while awaiting the restoration of his King.

Here and there, I glimpsed the petty intrigues of the Ministers of various petty States, quite scandalised by the trivial value I set on my ambassadorship: their self-importance tight-lipped, muffled, silent, trod stiff-legged taking tiny steps: it seemed ready to burst with secrets, of which it had no knowledge.

Book XXIX: Chapter 6: Artists ancient and modern

BkXXIX:Chap6:Sec1

As Ambassador to England in 1822, I searched for the men and places I had formerly known in London in 1793; as Ambassador to the Holy See in 1828, I hurried off to tour the palaces and ruins, and to ask after the people I had seen in Rome in 1803; I found plenty of palaces and ruins; but few of the people.

The Palazzo Lancellotti, previously rented to Cardinal Fesch, is now occupied by its true owners, Prince Lancellotti and Princess Lancellotti, the daughter of Prince Massimo. The house where Madame de Beaumont lived in the Piazza di Spagna, has vanished. As for Madame de Beaumont, she is immured in her last rest, and I have prayed at her grave with Pope Leo XII.

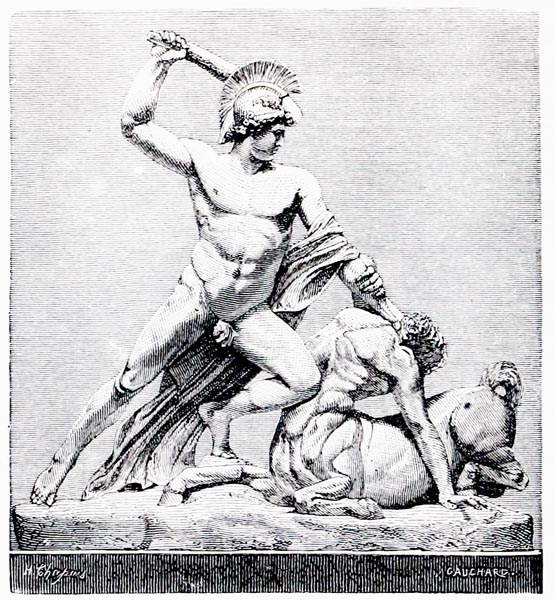

Canova equally has taken leave of the world. I visited him twice in his studio in 1803; he received me mallet in hand. He showed me, in the simplest and kindest of manners, his enormous statue of Bonaparte and his ‘Hercules hurling Lycas into the waves’: he aimed to convince you that he could reach the spirit within the form; but then even his chisel refused to search anatomy deeply enough; despite him, his nymphs remained of the flesh, and Hebe was revealed beneath the wrinkles of his old women. On my wanderings I had met the foremost sculptor of my time; he has fallen from his scaffolding, as Goujon did from the scaffolding of the Louvre; Death is always there to continue his endless Saint Bartholomew’s Day, and strike us down with his arrows.

‘Theseus Vanquishing the Minotaur, by Canova (Vienna)’

Wonders of Sculpture - Louis Viardot (p263, 1873)

Internet Archive Book Images

But someone still alive, to my great joy, is my old friend Boguet, doyen of the French painters in Rome. Twice he tried to leave his beloved landscapes; he got as far as Genoa; his heart failed him and he returned to his adopted hearth. I pampered him at the Embassy, as I did his son for whom he showed a mother’s tenderness. I started our former walks with him once more; I only perceive his age from the slowness of his steps; I experience a sort of tenderness in pretending to be young, and adjusting my pace to his. Neither of us have long to watch the Tiber flow.

The great artists, in the great eras, led a life quite different to that which artists lead today: attached to the vaults of the Vatican, the sides of St Peter’s, the walls of the Villa Farnesina, they worked on their masterpieces suspended in the air alongside them. Raphael walked surrounded by pupils, escorted by Cardinals and Princes, like a senator of ancient Rome preceded and followed by his clients. Charles V posed on three occasions for Titian. He picked up his brush for him, and yielded him right of precedence, just as Francis I attended Leonardo da Vinci on his deathbed. Titian went to Rome in triumph; the great Buonarotti received him: at ninety, Titian, the conqueror of the centuries still held his century-old Venetian paintbrush in a steady hand.

The Grand-Duke of Tuscany had Michelangelo, who had died in Rome after having designed the lantern for the dome of St Peter’s, secretly disinterred. Florence, in its magnificent obsequies, expiated over the ashes of its great painter the neglect with which it treated the ashes of Dante, its great poet.

Velasquez visited Italy twice, and Italy twice rose to salute him: the precursor of Murillo took the road back to Spain laden with fruit, picked with her own hands by that Ausonian Hesperia: he brought away a painting by each of the twelve most celebrated painters of his age.

Those famous artists spent their days in celebrations and affairs; they built defences for towns and castles; they erected churches, places and battlements; they gave and received sword-thrusts, seduced women, took refuge in cloisters, were absolved by Popes and protected by Princes. In an orgy spoken of by Benvenuto Cellini, some other Michelangelo appears, along with Giulio Romano.

Today the scene has altered completely; Artists in Rome live in quiet poverty. Perhaps there is poetry in such a life that is worth more. A confraternity of German painters has set out to take painting back to Perugino, to renew its Christian inspiration. These young neophytes of St Luke claim that Raphael, in his later manner, became a pagan, and that his talent degenerated. Let it be so; let us be pagans like Raphael’s virgins; let our talent degenerate and diminish as in his painting of The Transfiguration! This honourable error of the new sacred school is no less an error; it would follow from it that rigidity and poor formal design were proof of intuitive vision, yet that expression of faith, notable in the work of pre-Renaissance painters, is not because the figures are posed stiffly, as motionless as the Sphinx, but because the painter believed as his century did. It is his thought not his art that was religious; a thing so true, that the Spanish school is eminently pious in its expressions, even though it reveals the grace and movement of painting since the Renaissance. Why so: because the Spanish are Christians.

I go to see the various artists: the trainee sculptor lives in a grotto, under the green oaks of the Villa Medici, where he is finishing his ‘child with a snake drinking from a shell’, in marble. The painter lives in a dilapidated house in a deserted location; I find him alone, capturing a view of the Roman countryside through his open window. Monsieur Schnetz’s La Brigande has become a mother asking the Madonna for her son’s recovery. Léopold Robert, returning from Naples, passed through Rome in the last few days, bringing with him the enchanted landscapes of that lovely clime, which he has done only so as to transfer them to canvas.

Guérin has retired, like a sick dove, to the heights of a pavilion in the Villa Medici. He listens, his head on his shoulder, to the sound of the breeze off the Tiber; when he wakes up he sketches the death of Priam with his pen.

Horace Vernet is trying hard to change styles; will he succeed? The snake he drapes round his neck, the costume he affects, the cigar he smokes, the fencing masks and foils with which he is surrounded, are over-reminiscent of a temporary encampment.

Who has ever heard of my friend Monsieur Quecq, a successor to Julius III in the casina created by Michelangelo, Vignola and Taddeo Zuccari? And yet he has painted, in its sequestrated Nympheum, a rather fine ‘Death of Vitellius’. The uncultivated flower beds are haunted by a cunning creature which Monsieur Quecq is busy pursuing: it is a fox, great grandson of Goupil-Renart, the first of that name and nephew of Isengrin the Wolf.

Pinelli, between two bouts of drunkenness, has promised me twelve scenes, of dancing, gaming and thieves. It is a shame he allows the large dog at his door to die of hunger. Thorwaldsen and Camuccini are the two Princes of the poor artists of Rome.

Occasionally these scattered artists meet, and go together on foot to Subiaco. On the way, they daub grotesques on the walls of the inn at Tivoli. Perhaps one day some Michelangelo will be recognised by his tracings of charcoal over a work by Raphael.

I would like to have been born an artist; solitude, independence, sunlight among the ruins and masterpieces, would have suited me. I have no needs; a piece of bread, a jug of water from the Acqua Felice, would suffice me. My life has been wretchedly snagged by branches along the way; better to have been a bird free to sing and nest among those branches!

Nicholas Poussin bought a house on Monte Pincio with his wife’s dowry, facing another villa which belonged to Claude Gelée, called Lorrain.

My latter compatriot Claude also died at the feet of the Queen of the World. While Poussin depicts the Roman countryside even when the scenes of his landscapes are set elsewhere, Lorrain depicts the skies of Rome even when he paints sailing ships and the sun setting over the sea.

If only I had been a contemporary of those privileged creatures in diverse centuries for whom I feel an attraction! But I would have needed to rise from the dead far too often. Poussin and Claude Lorrain have passed to the Capitoline; kings appeared there who were not worthy of them. De Brosses met the English Pretender there; there, in 1803, I saw the King of Sardinia, who had abdicated, and now, in 1828, here I find Napoleon’s brother, the King of Westphalia. Rome, deposed, offers a sanctuary to fallen power; its ruins are a place of freedom for persecuted glory and unfortunate talent.

Book XXIX: Chapter 7: Past visitors to Rome

BkXXIX:Chap7:Sec1

If I pictured the society of Rome a quarter of a century ago, in the same way I have pictured the Roman countryside, I would be obliged to retouch my portrait; there would no longer be a resemblance. Each generation can be counted as thirty-three years, the life of Christ (Christ is the type for all); the form of each generation in our western world alters. Man is placed in a picture whose framework never changes, but whose figures alter. Rabelais was in this City in 1536 with Cardinal du Bellay; he occupied the position of butler to His Eminence; he sliced and served.

Rabelais, changed into Brother Jean des Entommeures, did not share Montaigne’s opinion, who heard scarcely any bells in Rome and far fewer than in a French village, Rabelais on the contrary, heard plenty in the Echoing Isle (Rome) doubting if it were not Dodona with its sounding cauldrons.

Forty-four years after Rabelais, Montaigne found the banks of the Tiber cultivated, and remarked that on the 16th March there were roses and artichokes in Rome. The churches were bare, without statues of saints, without paintings, less ornate and less beautiful than the churches of France. Montaigne was accustomed to the sombre vastness of our Gothic cathedrals; he speaks of St Peter’s several times without describing it, insensitive or indifferent to the arts as he seems to be. In the presence of so many masterpieces, no name offers itself to Montaigne’s memory; his remembrances tell him nothing of Raphael, or Michelangelo, not yet dead sixteen years.

‘Montaigne’

Pilules Apéritives à l'Extrait de Montaigne, préparées par Pierre Pic - Michel de Montaigne, Pierre Pic (p13, 1908)

Internet Archive Book Images

Moreover ideas about the arts, about the philosophical influence of the geniuses who developed and protected them, were not yet born. Time is for men what space is for monuments; neither can be judged well except from a distance and the viewpoint of perspective; too near and they cannot be seen, too far and they are no longer visible.

The author of the Essais only sought ancient Rome in Rome: ‘The buildings of that illegitimate Rome:’ he says, ‘one sees at this time, attaching their hovels to whatever they still possess of what delights the admiration of our present centuries, makes me recall those nests that the sparrows and crows build on the vaults and walls of churches in France that the Huguenots have recently demolished.’

What idea did Montaigne have of ancient Rome, if he regarded St Peter’s as a sparrow’s nest attached to the Coliseum’s wall?

Newly made a citizen of Rome, by an authentic Bull of 1581, he remarked that the Roman women did not carry dominos or masks like the French: they appeared in public covered with pearls and precious stones, but their belts were too loose and they looked pregnant. The men wore black, ‘and though they were Dukes, Counts and Marquises they had quite a lowly appearance.’

Is it not singular that Saint Jerome remarks on the gait of Roman women who make themselves look pregnant: ‘solutis geniubus fractus incesse: their feeble gait with swaying knees’?

Almost every day, when I go out through the Porto Angelica, I see a humble house, quite near the Tiber, with a smoke-blackened French sign representing a bear: it is there that Michel, the Lord of Montaigne, stayed on his arrival in Rome, not far from the hospital which served as a refuge for that poor madman, formed of pure and ancient poetry whom Montaigne visited in his lodge in Ferrara, and who invoked in him more frustration than compassion even.

It was a memorable event, when the 17th Century sent its greatest Protestant poet and most profound genius to visit the mighty Catholic Rome in 1638. With her back to the Cross, holding the Testaments in her hands, the guilty generations cast out of Eden behind here, and the redeemed generations descended from the Mount of Olives before her, she said to the heretic born yesterday: ‘What do you wish of your ancient mother?’

Leonora, the Roman girl, enchanted Milton. Has it ever been remarked that Leonora appears at Cardinal Mazarin’s concerts in the Memoirs of Madame de Motteville?

The passage of time led Abbé Arnauld to Rome after Milton. This Abbé, who had borne arms, recounts an anecdote interesting because of the name of one of the people involved, at the same time as it recalls the manner of courtiers then. The hero of the story, the Duc de Guise, grandson of Le Balafré, going in search of his Neapolitan adventure, passed through Rome in 1647: there he met Nina Barcarola. Maison-Blanche, secretary to Monsieur Deshayes, the Ambassador to Constantinople, took it into his head to become a rival to the Duc de Guise. Evil overtook him: they substituted (it was at night in an unlit room) a hideous old woman for Nina. ‘If the laughter was great on the one side, the confusion on the other can only be imagined’, says Arnauld. ‘Adonis, untangling himself with difficulty from the embraces of his goddess, fled naked from the house as if had the devil at his heels.’

Cardinal Retz says nothing about Roman manners. I prefer le petit Coulanges and his two trips in 1656 and 1689: he celebrates the vineyards and gardens whose names cast a spell.

In my walks to the Porta Pia I found almost all the people described by Coulanges: the people? No, their grand-sons and grand-daughters!

Madame de Sévigné received poems from Coulanges; she replied from her Château des Rochers in my humble Brittany, thirty miles from Combourg: ‘What a sad location I write from compared to yours, my kind cousin! It suits a solitary like me, as Rome does one whose star wanders. How tenderly fate has treated you, as you say, even though she has made you quarrelsome!!!’

‘Madame de Sévigné’

Old Paris: its Court and Literary Salons - Catherine Hannah Jackson, Lady Charlotte Elliott (p218, 1895)

Internet Archive Book Images

Between Coulanges’ first trip to Rome, in 1656, and his second, in 1689, thirty-three years passed; I lost only twenty-five between my first trip to Rome, in 1803, and my second in 1828. If I had known Madame de Sévigné, I would have been cured of the sorrow of ageing.

Spon, Misson, Dumont, and Addison successively followed Coulanges. Spon, and Wheler his companion, guided me through the ruins of Athens.

It is interesting to read in Dumont of the location of the masterpieces we admire, at the time of his journey in 1690; the Rivers Nile and Tiber, the Antinous, the Cleopatra, the Laocoon and the torso supposed to be of Hercules could be seen in the Belvedere. Dumont places the bronze peacocks from the tomb of Scipio Africanus in the Vatican Gardens.

Addison travels as a scholar, his journey summarised by classical quotations marked with memories of England; passing through Paris he presented his Latin poems to Monsieur Boileau.

BkXXIX:Chap7:Sec2

Père Labat followed the author of Cato: he is a strange man this Parisian monk of the Order of Preaching Friars. A missionary to the Antilles, freebooter, able mathematician, architect and soldier, brave artilleryman aiming his cannon like a grenadier, and knowledgeable critic, who regained possession for the inhabitants of Dieppe of their original discoveries in Africa, he had a spirit inclined to raillery and a character inclined to liberty. I know no traveller who gives a more exact or clearer idea of Papal government. Labat covers the ground, goes to the processions, mixes everywhere and pokes fun at almost everything.

The preaching father relates how, in Cadiz, among the Capuchins, he was given bed linen quite new ten years previously, and saw a St Jospeh dressed in Spanish style, sword at his side, hat under his arm, with powdered hair and glasses on his nose. In Rome, he assisted at a Mass: ‘I have never,’ he says, ‘seen so many castrato musicians together and so large an orchestra. Connoisseurs said they had never heard anything so beautiful. I said the same in order to be thought knowledgeable; but if I had not had the honour to be part of the officiant’s procession, I would have left the ceremony which lasted three straight hours at least, and seemed like six to me.’

The nearer I come to the time in which I am writing the more similar the customs of Rome are to those of today.

From the time of De Brosses, Roman women have worn wigs; the custom is ancient: Propertius asks of his life (his lover) why she chooses to adorn her hair:

‘Quid juvat ornato procedure, vita, capillo!

Why, mea vita, come with your hair adorned?’

The Gallic women, our ancestors, furnished hair for those Severinas, Piscas, Faustinas, and Sabinas. Velléda says to Eudore speaking of her hair: ‘It is my diadem and I cherish it for you.’ A hairstyle was not the Roman’s greatest legacy, but it was one of the most durable: people take from women’s tombs whole hairpieces which have evaded the scissors of the daughters of the night, and seek in vain the elegant brows they crowned. The perfumed tresses, an object of idolatry to the most fickle of passions, have survived empires; death, that breaks all bonds, could not disturb those fragile nets.

Today the Italian girls wear their own hair, which ordinary women plait with coquettish grace.

The magistrate and traveller De Brosses shows, in his portraits and writings, a deceptive resemblance to Voltaire with whom he had a comical dispute regarding a meadow. De Brosses often chatted at the bedside of a Princess Borghèse. In 1803, in the Borghèse Palace, I saw another Princess who shone with all her brother’s brilliance: Pauline Bonaparte is no more!

If she had lived in the age of Raphael, he would have depicted her as one of those amours that lean on the backs of lions in the Farnesina, and the same languor would have possessed painter and model. How many flowers have perished already in those wastes where I made Jerome, Augustine, Eudore and Cymodocée wander!

De Brosses depicts the English on the Piazza de Spagna almost as we see them today, living together, making a great noise, regarding humble humanity as beneath them, and returning to their red-brick hovels in London, having barely cast an eye on the Colisseum. De Brosses had the honour of paying court to James III.

‘Of the Pretender’s two sons,’ he says, ‘the elder is about twenty years old, the younger fifteen. I heard from those who know them well that the elder is nicer, and more deeply kind; that he has a good heart and great courage; that he feels his situation keenly, and that, if he does not escape from it someday, it will not be for lack of daring. I am told that having been taken when very young to the siege of Gaeta, during the Spanish conquest of the Kingdom of Naples, while crossing it his hat fell into the sea. Someone wished to retrieve it: “No,” he said, ‘it is not worth it; it would be better for me to come back and fetch it myself one day.”’

‘James Francis Edward, the Chevalier de St. George (1688-1765)’

The Stuart Dynasty: Short Studies of its Rise, Course, and Early Exile - Percy Melville Thornton (p7, 1890)

Internet Archive Book Images

De Brosses thought that if the Prince of Wales attempted anything, he would fail, and he gave his reasons. Returning to Rome after his gallant feats, Charles Edward, who carried the title of Count of Albany, lost his father; he married the Princess of Stolberg-Goedern, and settled in Tuscany. Is it true that he visited London secretly in 1752 and 1761, as Hume relates, that he was present at George III’s coronation, and that he said to someone who recognised him in the crowd: ‘The man who is the object of all that ceremony is him whom I envy least’?

The Pretender’s marriage was not a happy one; the Countess of Albany separated from him and took up residence in Rome: that was where another traveller, Bonstetten, met her; the gentleman from Bern, in his old age, told me at Geneva that he possessed letters from the Countess of Albany’s youth.

Alfieri met the Pretender’s wife in Florence and loved her for life: ‘Twelve years later,’ he says, ‘at the moment I am writing all these trifles, at the terrible age when there are no more illusions, I feel that I love her more every day, as time destroys the only charm not owing to herself, the brilliance of her passing beauty. My heart is elevated, and is becoming kinder and gentler because of her, and I dare to say the same thing of her, that I sustain and strengthen her.’

I knew Madame d’Albany in Florence; age appeared to produce in her an opposite effect to that usually produced: time ennobled her face and, as it is itself of the ancient race, it imprints something of that race on the brow it touches: the Countess of Albany, with her thick-waist, and expressionless face, had a common air. If the women from Rubens’ paintings were to grow old they would resemble Madame d’Albany at the age when I encountered her. I am sad that her heart, strengthened and sustained by Alfieri, needed another prop. I will reproduce here a passage from my letter on Rome to Monsieur Fontanes:

‘Do you know that I only saw Count Alfieri once in my life, and can you guess how? I saw him laid on his bier: I was told he looked almost unchanged; his physiognomy seemed noble and grave to me; death doubtless added fresh severity; the coffin being a little too short, the dead man’s head was bowed on his chest, which made him make a tremendous lurch.’

BkXXIX:Chap7:Sec3

Nothing is as sad as re-reading what one has written in one’s youth towards the end of one’s life: all that was present is now past.

In 1803, in Rome, I glimpsed the Cardinal-Duke of York, Henry IX, last of the Stuarts, aged seventy-eight. He had been weak enough to accept a pension from George III; Charles I’s widow solicited one from Cromwell in vain. So, the race of Stuarts was extinguished a hundred and eighteen years after losing that throne which it never recovered. Three Pretenders passed on, in exile, the shadow of a crown: they had the intellect and courage; what was it they lacked: the hand of God.

As for the rest, the Stuarts consoled themselves with the sight of Rome; they were merely one trivial incident the more among its mounds of rubble, a little broken column, erected in the midst of a vast network of ruins. Their race, as it vanished from the world, had one other reason for solace: it saw the old Europe fall, the fatality attached to the Stuarts brought other kings down to the dust with them, among whom was Louis XVI, whose grandfather refused sanctuary to Charles I’s descendant, while Charles X died in exile at almost the same age as the Duke of York, and his son and grandson are wandering the earth!

Lalande’s Travels in Italy in 1765 and 1766 is still the best and most exact work regarding artistic Rome and ancient Rome. ‘I love to read the historians and the poets,’ he writes, ‘but one will never read them with more pleasure than while walking the earth on which they trod, wandering the hills they described, and watching the rivers they sung of flowing by.’ Not too bad for an astronomer who lived on spiders.

Duclos, almost as emaciated as Lalande, made this fine comment: ‘The theatrical works of different nations are a true reflection of their manners. Harlequin, the manservant and principal character in Italian comedies, is always represented as famished, which arises from their habitual state of poverty. Our servants in comedy are commonly drunk, from which they may be supposed villainous but not wretched.’

The declamatory admiration of Dupaty offers little compensation for the dryness of Duclos and Lalande, yet it invokes the presence of Rome; one sees on reflection that his eloquence of descriptive style is born from Rousseau’s inspiration, spiraculum vitae: the breath of life. Dupaty partook of that new school which quickly substituted the sentimental, obscure and mannered for the truth, clarity and naturalness of Voltaire. However, through the medium of his affected jargon, Dupaty reveals careful observation: he explains the patience of the Roman people by the age of their successive sovereigns. ‘A Pope,’ he says, ‘is always for them a dying king.’