François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XVIII: The Levant, Armand, Les Martyrs 1806-1814

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XVIII: Chapter 1: The years 1805 and 1806 – I return to Paris – I leave for the Levant

- Book XVIII: Chapter 2: From Constantinope to Jerusalem – I embark at Constantinople on a ship carrying Greek pilgrims to Syria

- Book XVIII: Chapter 3: From Tunis to my return to France via Spain

- Book XVIII: Chapter 4: Reflection on my Travels – The Death of Julien

- Book XVIII: Chapter 5: The Years 1807, 1808, 1809 and 1810 – An article in the Mercury, June 1807 – I buy the Vallée-Aux-Loups and retreat there

- Book XVIII: Chapter 6: Les Martyrs

- Book XVIII: Chapter 7: Armand de Chateaubriand

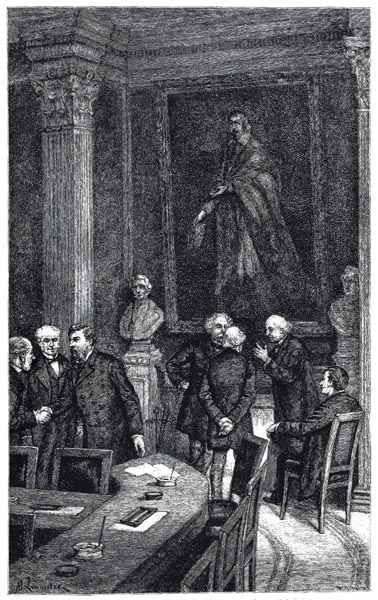

- Book XVIII: Chapter 8: The Years 1811, 1812, 1813 and 1814 – Publication of the Itinerary – A letter from Cardinal de Bausset – The death of Chénier – I am received as a member of the Academy – The matter of my speech – The Decennial Prize

- Book XVIII: Chapter 9: L’Essai sur les Révolutions – Les Natchez

Book XVIII: Chapter 1: The years 1805 and 1806 – I return to Paris – I leave for the Levant

Paris, 1839 (Revised December 1846)

BkXVIII:Chap1:Sec1

When, in returning to Paris by the Burgundy road, I caught sight of the cupola of Val-de-Grâce and the dome of Sainte-Geneviève, which overlooks the Jardin-des-Plantes, my heart was troubled: yet again a life’s companion left behind on the journey! We went back to the Hôtel de Coislin, and, though Monsieur de Fontanes, Monsieur Joubert, Monsieur de Clausel, and Monsieur Molé would have come to spend the evening with me, I was worked upon by so many thoughts and memories I could no longer meet them. Living alone, beyond the dear subjects who had parted from me, like a foreign sailor whose term has expired and who has neither home nor country, I kicked my heels on shore; I burned with a longing to swim in a new ocean to refresh myself and forge my way across. A scion of Pindar, bred in Jerusalem, I was impatient to merge my solitudes with the ruins of Athens, my sorrows with the Magdalen’s tears.

I went to see my relatives in Brittany, and, on returning to Paris, I left for Trieste on the 13th of July 1806: Madame de Chateaubriand accompanied me as far as Venice, where Monsieur Ballanche came to meet her.

My life having been documented hour by hour in the Itinerary, I would have nothing more to say here, if I did not possess several unpublished letters written or received during and after my voyage. Julien, my servant and companion, has, for his part, written an Itinerary to accompany mine, as passengers on board ship keep a detailed journal during a voyage of discovery. The short manuscript which he placed at my disposal has served to confirm my narration: I will be Cook, he can be Clerke.

In order to fully reveal the manner in which one was struck by the ordering of society and the hierarchy of intellects, I will interweave my narrative with that of Julien. I will let him speak first, since he covers several days sailing without me from Modon to Smyrna.

Julien’s Itinerary

‘We embarked on Friday the 1st of August; but, the wind not being favourable for leaving harbour, we moored until the following dawn. Then the port pilot came aboard to advise us that he could now allow us to leave. Since I had never been to sea, I was given an exaggerated idea of the risks, since I saw nothing of any such for two days. But on the third, a tempest blew up; lightning, thunder, finally a terrible storm assailed us and whipped up the waves with terrifying force. Our crew was made up of only eight sailors, the captain, an officer, a pilot, a cook, and five passengers, including Monsieur and myself, making seventeen men in all. We all set to, assisting the sailors to take in the sails, despite the rain which we were soon passing through, having discarded our coats to work more freely. The work occupied my mind, and made me forget the danger which, in truth, is more frightening in concept than it is in reality. For two days, the storms succeeded one another, which hardened me to my first days’ navigation; I was not troubled in the least. Monsieur had feared lest I suffer from sea sickness; when calm was re-established he said to me: ‘Now I am reassured about your health; since you have endured these two days of storms, you can rest easy regarding any other incidents.’ Nothing more took place during the rest of our course to Smyrna. On the 10th, which was a Sunday, Monsieur disembarked near to a Turkish village named Modon, where he landed in order to visit Greece. There were two men from Milan among the passengers with us, who were travelling to Smyrna to report on the tin-making and pewter operations. One of the two, who spoke the Turkish language quite well, was named Joseph, to whom Monsieur suggested that he might accompany him, as a private interpreter, and he mentions him in his Itinerary. Monsieur told us on leaving us that the voyage would only take a few days, and that he would rejoin the vessel at an island we were bound to pass in four or five days time, and that he would wait for us at that island, if he arrived there before us. Since Monsieur thought that this man would be all the company he needed for his little trip (from Sparta to Athens), he left me on board to continue my journey to Smyrna and take care of all our possessions. He entrusted me with a letter of recommendation to the French Consul, in case he failed to rejoin us; and that is what happened. On the fourth day we arrived at the island indicated. The Captain went ashore and Monsieur was not there. We anchored for the night and waited until seven in the morning. The Captain returned on shore to give warning that he was obliged to leave, having a fair wind and obliged as he was to take account of the distance. Moreover, he could see a pirate vessel seeking to approach us, and he had an urgent need of preparing our immediate defence. He charged his four cannon, and displayed his shotguns, pistols and blades on the bridge; but, as we had the advantage of the wind, the pirate abandoned us. We arrived in the port of Smyrna, on Monday the 18th, at seven in the evening.’

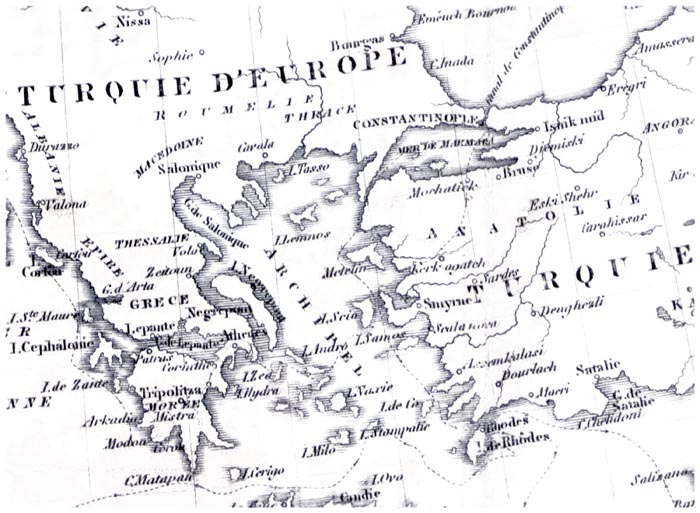

‘Map of Turkey’

Travels in Greece, Palestine, Egypt, and Barbary, during the years 1806 and 1807, Translated by Frederic Shoberl - François René de Chateaubriand (p8, 1812)

The British Library

Having crossed Greece, touching at Zea and Chios, I found Julien at Smyrna. Today, in my memory, I see Greece as one of those bright circles that one sometimes perceives when closing one’s eyes. On that mysterious phosphorescence are drawn the ruins of a fine and admirable architecture, the whole rendered still more resplendent by some further brightness of the Muses. When will I see the thyme of Hymettus once more, the oleanders on the banks of the Eurotas? One of the men I have most envied leaving behind on a foreign shore was the Turkish customs officer at Piraeus: he lived alone, the keeper of three deserted harbours, casting his eyes over the bluish islands, the gleaming promontories, and the golden waters. There, I only heard the noise of waves breaking against the obliterated tomb of Themistocles and the murmur of far away memories: in the silence of Sparta’s ruins, even fame was mute.

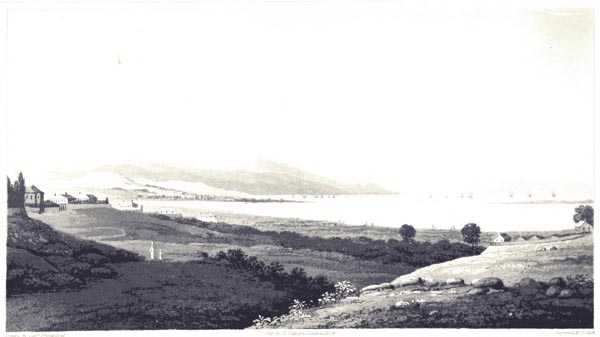

‘Distant View of the Bay and City of Smyrna’

Travels to and from Constantinople in the years 1827 and 1828 - Charles Colville Frankland (p318, 1829)

The British Library

I abandoned, in the cradle of Melesigene, my poor dragoman (interpreter) Joseph, the Milanese, in his tinsmith’s workshop, and headed for Constantinople. I went to Pergamum, wishing above all to reach Troy, out of poetic sympathy; a fall from my horse awaited me at the start of my journey; not because Pegasus flinched, but because I was asleep. I have recalled the incident in my Itinerary; Julien tells of it also, and he makes remarks, regarding the trails and the horses, to whose truth I can bear witness.

Julien’s Itinerary

‘Monsieur, who fell asleep on horseback, fell off without waking. As soon as the horse had halted, so did mine which was following. I quickly set foot to ground to find out the cause, since it was impossible for me to find out from six feet away. I saw Monsieur half-awake beside his horse, and quite astonished to find himself on the ground; he assured me he had suffered no hurt. His horse had not tried to bolt, which would have been dangerous, since the place where we were was close to the cliff-edge.’

Leaving Soma, having passed through Pergamum, I had an argument with my guide, recorded in the Itinerary. Here is Julien’s version:

‘We left that village at a very early hour, after having recharged our canteen. A short distance from the village, I was extremely surprised to se Monsieur furious with our guide; I asked the reason. Then, Monsieur told me that he had agreed with the guide, at Smyrna, that he would lead him to the plains of Troy, on the way, but that, at this moment, he refused saying that the plains were infested with brigands. Monsieur believed not a word of it and would listen to no one. As I could see he was getting more and more excited, I signalled to the guide to come closer to the interpreter and the janissary (guard), to explain to me what he been told of the dangers which might be present in the plains which Monsieur wished to visit. The guide told the interpreter that he had been assured that it was necessary to travel in great numbers to avoid attack: the janissary told me the same thing. So I went to Monsieur and told him what all three had said, and, further, that we would find a little village within a day’s travel where they had a sort of Consul who could inform us of the true position. After this conversation, Monsieur calmed down and we continued our journey towards that place. As soon as we arrived, he went to the Consul, who told him of all the risks he ran, if he persisted in his intention to travel with such a small group into the plains of Troy. Then Monsieur was obliged to forgo his project, and we continued our journey to Constantinople.’

I arrived at Constantinople.

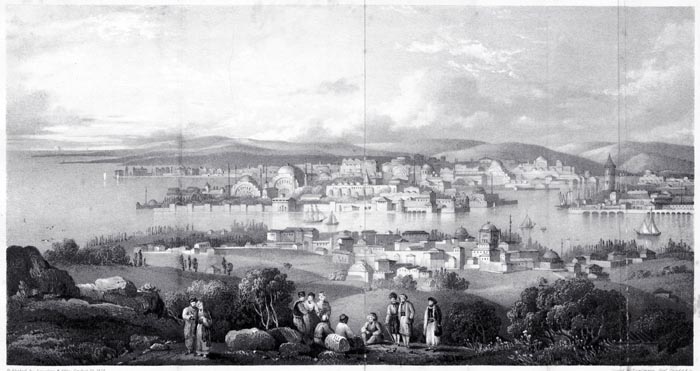

‘View of Constantinople From the Hills Behind Scutari’

Constantinople in 1828...Second edition, Vol 02 - Charles Macfarlane (p269, 1829)

The British Library

My Itinerary

‘The almost complete absence of women, the lack of wheeled vehicles and the packs of master-less dogs were the three distinctive characteristics that first struck me in the interior of that extraordinary city. Since nearly everybody walks about in oriental slippers, since there is no sound of carts or carriages, since there are no bells, and almost no trades requiring a hammer, the silence is continuous. You see a mute crowd around you who seem to wish to pass by without being perceived, and who always have the air of hiding from their masters. You arrive continually at a bazaar or a cemetery, as if the Turks were only there to buy, sell or die. The cemeteries, lacking walls and set in the midst of the streets, contain groves of magnificent cypress trees: the doves make their nests in these cypresses and share the peace of the dead. Here and there one finds ancient monuments which bear no relationship to modern man or later monuments, with which they are surrounded: one might imagine they were transported to this oriental city for talismanic effect. No signs of joy, no indications of happiness reveal themselves to your eyes; what one sees are not a people, but a crowd led by an imam and whose throats a janissary slits. Among prisons and penal colonies, rises a seraglio, Capitol of slavery: there a sacred guardian carefully conserves the germs of plague and the primitive laws of tyranny.’

Julien, for his part, does not lose himself thus among the clouds:

Julien’s Itinerary

‘The interior of Constantinople is very unpleasant on account of its sloping towards the canal and the port; one is obliged to beat a retreat time after time from all the streets which descend in that direction (very badly paved streets) in order to keep to the land that the water surrounds. There are few vehicles: the Turks make much more use of saddle-horses than other nations. In the French quarter there are several chairs with porters for the ladies. There are also horses and camels for hire for transporting merchandise. One also sees porters, Turks with very thick long sticks; they can fasten five or six items to each end and carry enormous loads at a steady pace; a single man can also carry very heavy burdens. They have a sort of hook, which is fitted to them from the shoulders to the small of the back, and with remarkable skill in balancing they carry all the parcels without them being secured.’

Book XVIII: Chapter 2: From Constantinope to Jerusalem – I embark at Constantinople on a ship carrying Greek pilgrims to Syria

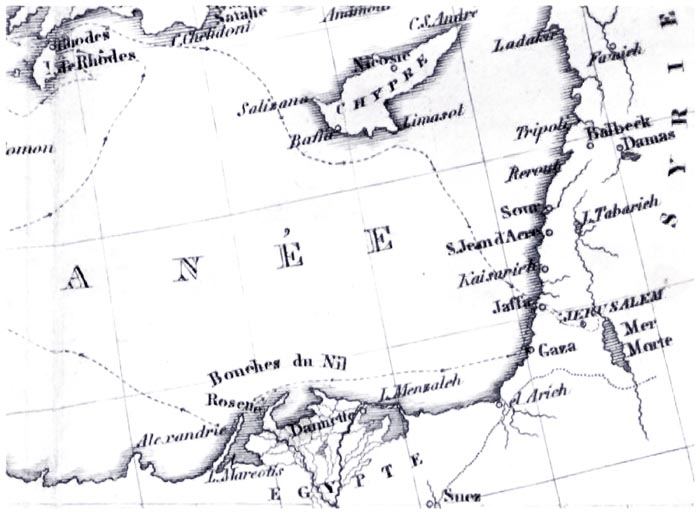

‘Map of Syria and Egypt’

Travels in Greece, Palestine, Egypt, and Barbary, during the years 1806 and 1807, Translated by Frederic Shoberl - François René de Chateaubriand (p8, 1812)

The British Library

BkXVIII:Chap2:Sec1

My Itinerary

‘There were almost two hundred passengers on board, men, women, children and old people. One saw as many mats ranged in ranks on both sides of the tween deck. In that republic of sorts each managed their household as they liked: women nursed their children, men smoked or prepared their dinner, elders talked together. The sound of mandolins, violins and lyres was heard on all sides. They sang, danced, laughed, and prayed. Everyone was joyful. Pointing south, they cried: “Jerusalem!” and I replied: “Jerusalem!” In a word, without our fear, we would have been the happiest people in the world; but at the least wind, the sailors took in the sails, and the pilgrims shouted: Christos, Kyrie eleison! The storm past, we recovered our courage.’

Here, I am outdone by Julien:

Julien’s Itinerary

‘We were obliged to attend to our departure for Jaffa, which took place on Thursday the 18th of September. We embarked on a Greek vessel, on which there were at least a hundred and fifty Greeks, as many men as women and children, who were going on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, which caused the ship many difficulties.

We had provisions and cooking utensils, like the other passengers, which I had bought in Constantinople. I had, besides, another complete pack of provisions that Monsieur l’Ambassadeur had given us, composed of good quality biscuits, ham, sausages and saveloys; wine of different sorts, rum, sugar, lemons, even including wine flavoured with cinchona-bark for the fever. So I found myself provided with abundant resources, which I husbanded and did not consume, with great economy, knowing we had only this voyage to make; all was squeezed in where the passengers could not go.

Our journey, which has taken only thirteen days, has seemed long to me because of all kinds of disagreement and impropriety on board. During several days of bad weather which we have had, the women and children were sick, vomiting everywhere to the point that we were obliged to abandon our berth and sleep on the bridge. We ate there much more conveniently than elsewhere, having opted to wait until all the Greeks had finished their messing about.’

I pass the Dardanelles straits; I touch at Rhodes, and engage a pilot for the coast of Syria. – We are delayed by the calm, below the continent of Asia, almost opposite ancient Cape Chelidonia. – We linger for two days at sea, without knowing where we are.

My Itinerary

‘The weather was so beautiful, and the breeze so gentle, that all the passengers spent the night on deck. I disputed a small corner of the poop with two large Greek monks who yielded to me but not without muttering. I was asleep there on the 30th of September, at six in the morning, when I was woken by a babble of voices: I opened my eyes, and saw the pilgrims staring towards the prow of the vessel. I asked what was there; they shouted to me: Signor, il Carmelo! Mount Carmel! The wind had risen the previous evening at eight, and, during the night, we had arrived in sight of the Syrian coast. As I was lying there fully dressed, I was soon up, inquiring about the sacred mountain. They all surrounded me to point it out; but I could see nothing, because the sun was rising in our faces. The moment had something both religious and majestic about it; all the pilgrims, rosary in hand, were standing in silence in the same attitude, waiting for a sight of the Holy Land; the head of the elders prayed in a loud voice: one heard only this prayer and the sound of the vessel’s wake as the most favourable of winds drove it over the gleaming sea. From time to time, a cry rose from the prow as they caught sight of Carmel again. At last I saw the mountain for myself, like a round blob beneath the sun’s rays. I knelt then in the manner of us Latins. I did not feel the kind of agitation that I experienced on seeing the coast of Greece: but the sight of the cradle of the Israelites and the fatherland of Christians filled me with joy and respect. I was to set foot on a land of wonders, the source of the most astonishing poetry, in places where, speaking even in a purely human sense, the greatest event which ever changed the face of the world occurred.’

....................................

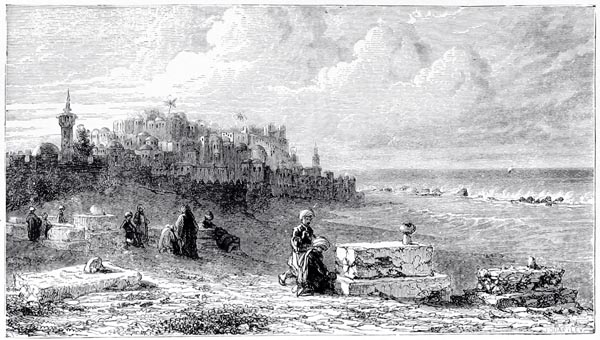

‘The wind dropped at midday; it rose again at four; but, through the pilot’s ignorance, we missed our objective. At two in the afternoon, we saw Jaffa again.

A boat left shore with three monks aboard. I descended with them into the launch; we entered harbour through a navigable opening in the rocks, dangerous even for a rowing boat.

The Arabs on shore advanced into the water to their waists, in order to take us up on their shoulders. There passed a pleasant scene; my servant was dressed in a whitish dress-coat; white being the colour of distinction among the Arabs, they decided that Julien was the sheik. They seized on him and carried him off in triumph, despite his protestations, while I, dressed in my blue coat, made off unnoticed on the back of a ragged beggar.’

Now, let us hear, Julien, the principal actor of the scene:

Julien’s Itinerary

‘What was my astonishment on seeing half a dozen Arabs arriving to carry me to shore, while there were only two for Monsieur, it amusing him greatly to see me carried like a sacred object. I do not know if my clothing appeared more imposing than Monsieur’s to them; he had on a brown coat and buttons of the same colour, while mine was whitish, with buttons of pale metal which reflected the light of the sun; it is no doubt that which may have occasioned their error.

We entered the monastery of the monks of Jaffa, on Wednesday the 1st of October, they being of the Order of the Cordeliers, speaking Latin and Italian, but very little French. They made us very welcome and did everything possible to procure whatever we needed.’

‘Jaffa’

A Visit to Europe and the Holy Land...Fourth edition - H. F. Fairbanks (p133, 1896)

The British Library

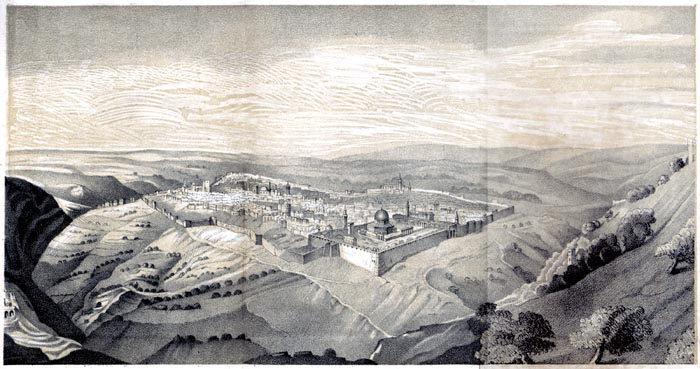

I arrive at Jerusalem. – On the advice of the Fathers of the monastery, I cross the Holy City rapidly in order to reach the Jordan. – After halting at the monastery in Bethlehem, I leave with an escort of Arabs; I stop at Saint-Saba. – At midnight, I found myself on the shore of the Dead Sea.

My Itinerary

‘When one travels in Judea, a great tedium first seizes the mind; but when, in passing from solitude to solitude, the space extends itself before you, the ennui gradually dissipates, and one experiences a secret terror which, far from depressing the soul, gives one courage and raises one’s spirits. Extraordinary sights reveal on all sides a land worked on by miracles: the burning sun, the impetuous eagle, the sterile fig-tree, all the poetry, all the Scriptural tableaux are there. Every name conceals a mystery; every cave foretells the future; every summit retains the tones of some prophet. God Himself has spoken on these shores: the dried-up torrents, the shattered rocks, the half-open tombs, attest to marvels; the desert seems mute with terror still, and one would say it had not dared to break the silence since it heard the Eternal voice.’

We had descended the rump of the mountain, in order to spend the night on the shore of the Dead Sea, from there to return to the Jordan.

Julien’s Itinerary

‘We dismounted from our horses to let them rest and eat, like us, who had a fine set of provisions that the monks of Jerusalem had given us. After our meal was finished, our Arabs went some way from us, to listen, ear to the ground, for any sound; being assured that we could rest easy, everyone then abandoned themselves to sleep. Though lying on stones, I had enjoyed a very good sleep, when Monsieur came to rouse me, at five in the morning, to get all our people ready for departure. He had already filled a canister, holding about three wine-bottles, with water from the Dead Sea, to take back to Paris.’

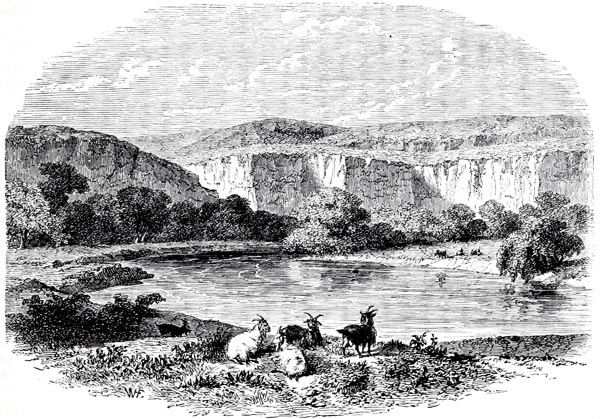

My Itinerary

‘We raised camp, and travelled for an hour and a half with exceeding difficulty, through fine white sand. We advanced towards a little grove of trees, balm and tamarind, which to my great astonishment, I saw rising from the midst of sterile ground. Suddenly, the Bethlehemites stopped and pointed out, in the depths of a ravine, something which I had not noticed. Without being able to say what it was, I half saw what seemed like a kind of sand-flow over the motionless earth. I approached this singular object, and saw a yellow stream that I could scarcely distinguish from the sand of its two banks. It was deeply incised, and ran thickly with a sluggish flow: it was the Jordan.

The Bethlehemites stripped off and plunged into the Jordan. I dared not imitate them, because of the fever which continually troubled me.’

Julien’s Itinerary

‘We arrived at the Jordan at seven in the morning, through sands where our horses sank in up to their knees, and through gullies which they had difficulty climbing out of. We followed the river until ten, and to cool us we were bathed conveniently in the shade of the low trees which bordered the river. It would have been very easy to cross to the other side by swimming, since its width, where we were situated, was only about 80 yards; but it would not have been safe to do so, since there were Arabs trying to catch up with us, and in a short while they assembled in large numbers. Monsieur filled his second canister with Jordan water.’

‘Les Bords du Jordan’

Voyageurs Anciens et Modernes, ou Choix des Relations de Voyages...Depuis le Cinquième Siècle Avant Jésus-Christ Jusqu'au Dix-Neuvième Siècle - Édouard Thomas Charton (p475, 1854)

The British Library

We returned to Jerusalem: Julien was not much taken with the Holy Places; like a true philosopher, he is terse: ‘Calvary,’ he says, ‘is in the same church, on a height, similar to many other heights we have climbed, and from which you can see nothing in the distance but uncultivated land, and nothing as to trees but shrubs and undergrowth gnawed by animals. The Valley of Josaphat is found outside the walls of Jerusalem, at its foot, and resembles a moat to a rampart.’

‘Jerusalem’

Das Heilige Land Nach Seiner Ehemaligen und Jetzigen Geographischen Beschaffenheit, Nebst Kritischen Blicker in das C. v. Raumer'sche “Palästina” - Joseph Schwarz (p507, 1852)

The British Library

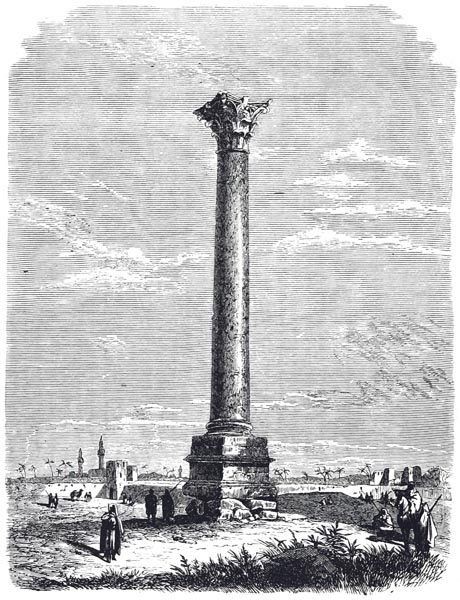

I left Jerusalem; I arrived at Jaffa, and embarked for Alexandria. From Alexandria I went to Cairo, leaving Julien behind with Monsieur Drovetti, who had the kindness to charter an Austrian vessel to Tunis for me. Julien continues his journal in Alexandria: ‘There are,’ he says, ‘Jews who speculate illegally as they do wherever they are. At half a league from the town, there is Pompey’s Pillar, which is of reddish granite, mounted on a sizeable bank of stones.’

My Itinerary

‘On the 23rd of November at midday, the wind turning favourable, I returned on board the vessel. I embraced Monsieur Drovetti on the shore, and we exchanged promises of remembrance and friendship; today I acquit my debt.

We raised anchor at two. A pilot took us out of port. The wind was blowing weakly from the south. We stayed in sight of Pompey’s Pillar which we could make out on the horizon for three days. On the evening of the third day, we heard the sound of the night canon from the harbour at Alexandria. It was like a signal for our final departure, since a northerly wind rose, and we made sail to the west.

On the 1st of December, the wind, steady from the west, barred our course. Gradually it swung to the south-west and changed to a storm, which did not cease until we arrived at Tunis. To occupy the time, I copied and set in order the notes of this voyage and the descriptive passages of Les Martyrs. At night, I walked on the bridge with the second in command, Captain Dinelli. Nights spent among the waves, on a ship battered by a storm, are not wasted; uncertainty regarding our future gives objects their true worth: the earth, contemplated from the midst of a stormy sea, resembles life considered by a man who is about to die.’

‘Pompey's Pillar’

Auf Biblischen Pfaden. Reisebilder aus Aegypten, Palästina, Syrien, Kleinasien, Griechenland und der Türkei - C. Ninck (p32, 1885)

The British Library

Julien’s Itinerary

‘After our exit from the harbour at Alexandria, we did quite well for the first few days, but it did not last, since we had continual bad weather and foul winds for the rest of the voyage. There was an officer on watch on the bridge constantly, with the pilot and four of the crew. When we could see, at the end of the day, that we were about to have a bad night, we would ascend to the bridge. Around midnight, I made our punch. I would start by handing some to our pilot and the four sailors then I would serve Monsieur, the officer and myself: but we did not drink it as calmly as we would have done in a café. The officer was much more accustomed to it than the captain; he spoke French very well, which made it very pleasant for us during our voyage.’

We continue our journey and anchor at the Kerkeni Islands.

My Itinerary

‘A storm rose from the south-west to our great joy, and in five days we arrived in the waters around Malta. We caught sight of it on Christmas Eve; but on Christmas Day itself, the wind, veering to west-north-west, drove us south of Lampedusa. We lingered for eighteen days on the east coast of the kingdom of Tunis, between life and death. I will never forget the 28th.

We dropped anchor at the Kerkeni Islands. We stayed eight days at anchor in the Syrtis Minor, where I began the year 1807. Beneath how many stars and with what varying fortune I have seen the years renew, years which pass so quickly or seem so long! How far from me are those childhood days when with joyful heart I received my parents’ blessings and presents! How eagerly New Year’s Day was awaited! And now, on a foreign vessel, in the midst of the sea, in sight of a barbarous land, that first day vanished for me, without witness, without pleasure, without family embraces, without the tender good wishes that a mother bestows on her son with such sincerity! That day, born from the womb of tempests, only deposited on my brow anxieties, regrets and white hairs.’

Julien is exposed to the same fate, and he reprimands me for one of those fits of impatience of which happily I am cured.

Julien’s Itinerary

‘We were close to the Isle of Malta and were fearful of being seen by some English vessel which might have forced us to enter that port; but nothing came out to meet us. Our crew were exhausted and the wind continued unfavourable. The captain seeing an anchorage named Kerkeni on his chart, which we were not far off, made sail, without warning Monsieur, who, seeing us approaching an anchorage, was angry at not having been consulted, telling the captain he must continue on course, having endured worse weather. But we were too close to resume our route, and moreover the captain’s prudence was much approved of, since the night before, the wind had become stronger and the sea very rough. Having been obliged to wait there at anchor twenty four hours longer than anticipated, Monsieur showed his lively dissatisfaction with the captain, despite the logical reasons he was given.

We had been sailing for almost a month, and we only needed seven or eight hours to reach the port of Tunis. Suddenly, the wind became so violent that we were obliged to veer off, and we waited for three weeks without being able to reach the harbour. It was then that Monsieur reproached the captain once more for having lost thirty-six hours at anchor. No one could persuade him that we would have been in deep trouble, if the captain had shown less foresight. The misfortune I could foresee was that of our dwindling provisions, without knowing when we might arrive.’

I have trod the soil of Carthage at last. I have found the most generous hospitality with Monsieur and Madame Devoise. Julien gets to know my host well; he talks about the country too and the Jews: ‘They pray and weep’, he says.

An American brig of war having granted me passage on board, I crossed the Lake of Tunis to reach La Goulette. ‘Once underway,’ says Julien, ‘I asked Monsieur if he had brought the gold he had placed in a desk in the room where he slept; he told me had forgotten it, and I was obliged to return to Tunis.’ Money never lodges itself in my brain.

When I arrived at Alexandria, we anchored opposite the ruins of Hannibal’s city. I stared at them from the ship’s side without being able to make out what they were. I saw several Moorish dwellings, a Muslim hermitage on the headland, ewes grazing among the ruins, ruins so little evident that I could scarcely distinguish them from the soil they stood on: it was Carthage. I visited it before embarking for Europe.

My Itinerary

‘From the summit of Byrsa, the eye embraces the ruins of Carthage which are more numerous than is generally thought: they resemble those of Sparta, nothing worthwhile having been preserved, but occupying a considerable space. I saw them in the month of February; the fig-trees, olives, and carob-trees already showed their first leaves; large angelicas and acanthuses formed tufts of verdure among the multi-coloured marble ruins. In the distance I glanced over an isthmus, twin seas, far-off islands, a glowing countryside, bluish lakes, and azure mountains; I made out forests, vessels, aqueducts, Moorish villages, Muslim hermitages, minarets and the white houses of Tunis. Thousand of starlings, flocking in battalions and looking like dark clouds, flew above my head. Surrounded by the greatest and most moving of relics, I thought of Dido, of Sophonisbe, of Hasdrubal’s noble wife; I contemplated the vast plains where the legions of Hannibal, Scipio and Caesar are buried; my eyes wished to dwell on the site of Utica. Alas! The ruins of Tiberius’s palace on Capri are still in existence, but one searches in vain at Utica for Cato’s house! Finally the terrifying Vandals and the careless Moors passed in turn through my memory, which offered me, as a last tableau, Saint Louis expiring among the ruins of Carthage.’

Julien ends like me by catching his last sight of Africa at Carthage.

Julien’s Itinerary

‘On the 7th and 8th we wandered among the ruins of Carthage where there are still some foundations on open ground, which prove the durability of ancient monuments. There are also the outlines of baths submerged beneath the soil. There are still three fine cisterns; others are visible which have been buried. The few inhabitants who occupy these regions cultivate the fields necessary to them. They uncover various marbles and stones, just as they do medals which they sell to travellers as antiques: Monsieur bought some to take back to France.’

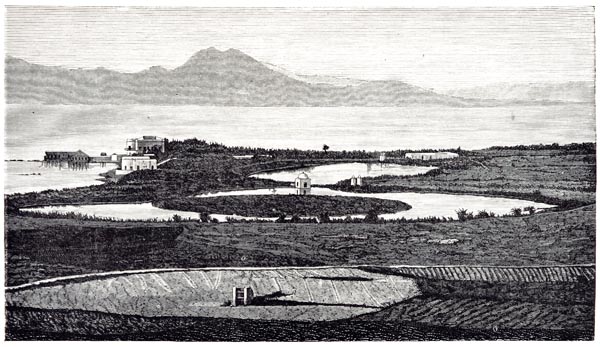

‘Forum, Port Militaire et Port Marchand de Carthage’

De Carthage au Sahara - Pierre Bauron (p41, 1893)

The British Library

Book XVIII: Chapter 3: From Tunis to my return to France via Spain

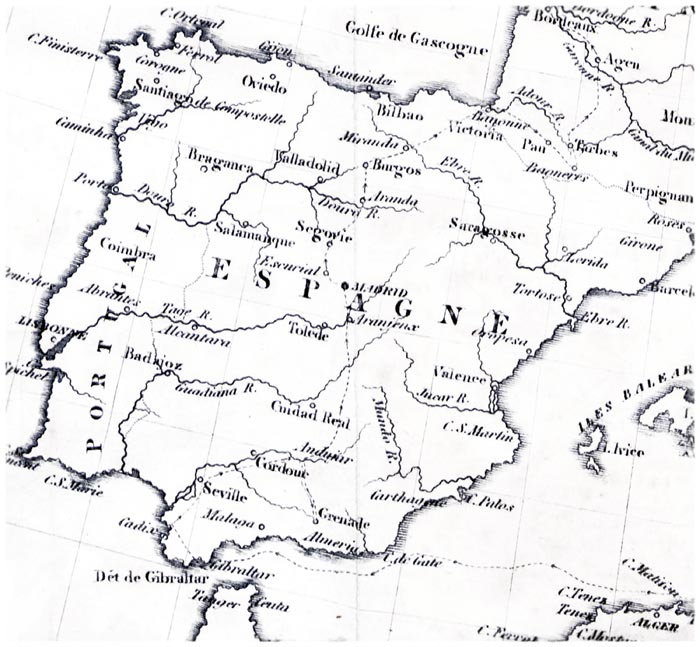

‘Map of Spain’

Travels in Greece, Palestine, Egypt, and Barbary, during the years 1806 and 1807, Translated by Frederic Shoberl - François René de Chateaubriand (p8, 1812)

The British Library

BkXVIII:Chap3Sec1

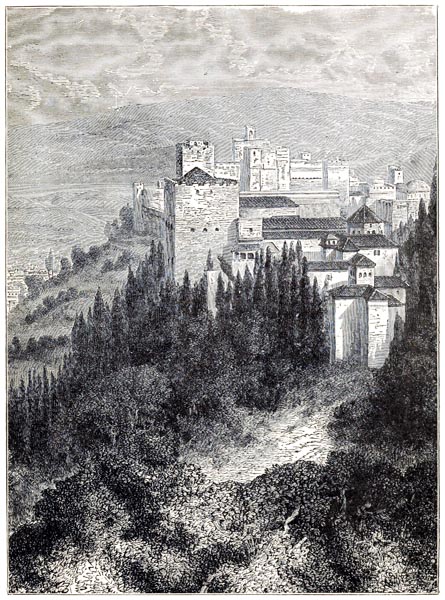

Julien tells briefly of our voyage from Tunis to the Bay of Gibraltar; from Algeciras, he quickly reaches Cadiz, and, from Cadiz, Granada. Indifferent to Blanca, he merely remarks that the Alhambra and other buildings rise from the rocks to an immense height. My Itinerary does not enter into much more detail regarding Granada; I content myself with saying:

‘The Alhambra seems to me worthy of note, even after the ruins of Greece. The valley of Granada is delightful and much resembles that of Sparta: one can understand that the Moors regret their second country.’

‘General View of the Alhambra, Granada’

Rambles in Sunny Spain - Frederick Albion Ober (p254, 1889)

Internet Archive Book Images

In Le Dernier des Abencérage, I describe the Alhambra. The Alhambra, the Generalife, and Sacromonte are etched on my mind like those imaginary countries that one half-sees, often at break of day in the beautiful first light of dawn. I still feel Nature deeply enough to describe the Vega; but I would not dare attempt it, for fear of the Archbishop of Granada. During my stay in the city of sultanas, a guitarist, driven by an earthquake from a village which I happened to travel through, attached himself to me. Deaf as a post, he followed me everywhere: when I sat among the ruins in the Palace of the Moors, he stood by my side and sang, accompanying himself on his guitar. The harmonious indigent might not have composed a Creation oratorio, perhaps, but his sunburnt chest showed through the tatters of his jersey, and he had great need of writing as Beethoven did to Mademoiselle Breuning: ‘Venerable Eleonore, my very dear friend, I would dearly wish to be fortunate enough to possess a jacket of angora rabbits’ wool knitted by you.’

From one coast to the other, I traversed that Spain where, sixteen years later, heaven reserved a great role for me, in helping to stifle anarchy amongst a noble people, and liberating a Bourbon: the honour of our arms was re-established, and I would have saved the Legitimacy, if the Legitimacy could have understood the conditions for its survival.

Julien does not let go of me until he has brought me back to the Place Louis XV, on the 5th of June 1807, at three in the afternoon. From Granada, he had conducted me to Aranjuez, to Madrid, to the Escorial, from which he leaps to Bayonne.

‘We left Bayonne,’ he says, ‘on Tuesday the 9th of May for Pau, Tarbes, Barèges and Bordeaux, which we reached on the 18th, very weary, each with a bout of fever. We left on the 19th, and travelled to Angoulême and Tours, arriving at Blois on the 28th, where we slept. On the 31st, we continued our route to Orléans, and then made our last overnight stop at Angerville.’

I was there, five miles from a château whose inhabitants my long voyage had not caused me to forget. But the gardens of Armida, where are they? Twice or thrice, returning to the Pyrenees, I have seen the column at Méréville from the highway; like Pompey’s Pillar it told me of the wilderness: like my fortunes at sea, everything has altered.

BkXVIII:Chap3Sec2

I arrived in Paris before the news I had sent about myself: I had overtaken my existence. As insignificant as those letters are, I glance through them as one looks at poor sketches of places one has visited. These letters are dated from Modon, Athens, Zea, Smyrna, and Constantinople; from Jaffa, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Tunis, Granada, Madrid, and Burgos; these lines traced on all sorts of paper, in all sorts of ink, brought by all the winds, interest me. I not only delight in unrolling my firmans (passports etc): I touch their vellum with pleasure; I am revealed in elegant calligraphy and am dumbfounded by the pomp of their style. I was a very great person, then! We are such miserable devils, with our letters for three sous and our passports for forty, next to those lords of the turban!

Osman Said, Pasha of the Morea, thus addresses ‘whomever it may concern’ on my firman for Athens:

‘Rulers of the towns of Mistra (Sparta) and Argos, cadis, nabobs, effendis, whose wisdom grow greater yet; honoured by your peers, and our greatness, vaivodes, and you by whom your master sees, who represent him in each of your jurisdictions, men of stature and business, whose credit cannot but grow;

We advise you that one of the noblemen of France, a nobleman (in particular) from Paris, furnished with this order, accompanied by an armed janissary and a servant as escort, has requested permission and explained his intention of travelling through various places and sites which are under your jurisdiction, in order to reach Athens, which is beyond the Isthmus, outside your jurisdiction.

You effendis, vaivodes, and all others specified above, therefore, are to take great care when the above mentioned person arrives within your jurisdiction, that he is shown respect and all the measures which friendship makes lawful, etc., etc.

Year 1221 of the Hegira.’

My passport issued in Constantinople for Jerusalem, reads:

‘To the sublime tribunal of His Highness the Kadi of Kouds (Jerusalem), most excellent Sherif, effendi:

Accept, most excellent effendi, whom Your Highness has appointed to his august tribunal, our sincere blessings and affectionate greetings.

We advise you that a noble person, of the French Court, named François-Auguste de Chateaubriand, is travelling presently towards you, to accomplish the holy pilgrimage (of Christians).’

Do we protect foreign travellers in this way, in regard to the mayors and gendarmes who inspect his passport? Equally one can read in these firmans the transformation of nations: what freedom must God have given to empires, for a Tartar slave to impose his orders on a vaivode of Mistra, that is to say a magistrate of Sparta: for a Muslim to recommend a Christian to the Cadi of Kouds, that is to say of Jerusalem!

BkXVIII:Chap3Sec3

The Itinerary is one of the elements which make up my life. When I left in 1806, a pilgrimage to Jerusalem seemed a great enterprise. Now that a crowd have followed me, and the whole world is on board, the wonder has vanished; Tunis alone barely remains my own: less people head for that coast and it is acknowledged that I have identified the true location of the harbours of Carthage. This fine letter proves it:

‘Monsieur le Vicomte, I have just received a plan of the site and ruins of Carthage, giving the exact contours and the relief map; it was measured trigonometrically from a 1500 metre base, and is supported by barometric observations made with matched barometers. It has been a work requiring ten years patience and precision: it confirms your opinion on the harbours of Byrsa.

With this exact plan, I have gone over all the ancient texts again, and I have determined, I think, the exterior enclosure and the other areas of Cothon, Byrsa and Megara, etc, etc. I now render you the justice due you in so many respects.

If you are not afraid of me swooping down upon your genius with my trigonometry and my weighty erudition, I will appear at your house at the first indication on your part. If my father and I follow you, in literature, longissimo intervallo (at a very great distance), at least we will try to imitate you in the noble independence of which you have given France such a fine model.

I have the honour to be, and boast of being, your honest admirer,

DUREAU DE LA MALLE.’

A corresponding identification of the sites would have sufficed in former days to make my name as a geographer. Henceforth, If I still had a mania for speaking about myself, I know not where I might not have run off to, in order to catch the public’s attention: perhaps I might have taken up my old project once more of discovering the North-West passage; perhaps I might have ascended the Ganges. There, I would have seen the long dark straight line of trees that defends the Himalayas; if, after reaching the col that connects the two principal summits near the Gangotri glacier, I were to discover the immeasurable amphitheatre of eternal snow, if I were to ask my guides, as Heber, the Anglican Bishop of Calcutta did, the name of the other mountains to the East, they would reply that they border the Empire of China. Well and good! But to return to the Pyramids, now, is as if one were merely returning to Montlhéry. A propos of that I recall that a pious antiquary of the neighbourhood of Saint-Denis in France wrote to me to ask if Pontoise did not resemble Jerusalem.

The page which terminates my Itinerary seems to have been written at that very moment, it so reflects my true feelings.

‘It was twenty years ago,’ I wrote, ‘that I dedicated myself to study among all the dangers and sorrows; diversa exilia et desertas quaerere terras: searching out differing exiles in different deserts: a large number of leaves from my books have been traced in my tent, in the desert, among the waves; I have often grasped my pen without knowing how many moments longer my existence might be prolonged. If Heaven grants me a peace I have never enjoyed, I will attempt in silence to raise a monument to my country; if Providence refuses me that peace, I can only think to spend my last days sheltering from the cares that poisoned my first. I am no longer young, I no longer love noise; I know that literature whose business is so sweet when it is secret, only draws us into the storm, outside. In any case, I have written enough if my name should live on; far too much if it should die.’

BkXVIII:Chap3Sec4

It is possible that my Itinerary will last as a manual for the use of my kind of Wandering Jew: I have marked out the stages scrupulously and sketched a road map. Every voyager to Jerusalem writes to me to congratulate me and thank me for my exactitude; I will cite an example:

‘Monsieur, you did me the honour, some weeks ago, to receive me at your house, with my friend Monsieur de Saint-Laumer: in bringing you a letter from Abou-Gosch, we happened to mention how many new merits one finds in your Itinerary when reading it in the locations themselves, and how one appreciates even in its very title, such a humble and modest choice of yours, when seeing it justified at every step by the scrupulous accuracy of its descriptions, still true today, except for a few ruins more or less, the only change in those countries, etc.

JULES FOLENTLOT

Rue Caumartin, no 23.’

My accuracy is due to my plain commonsense; I am of the race of Celts and tortoises, a pedestrian race; not of the blood of Tartars and birds, races equipped with horses and wings. Religion, it is true, sometimes ravished me in its embrace; but when it returned me to earth, I walked on, leaning on my stick, resting by a milestone to eat my olives and brown bread. If I often rode in the wood, as many a François gladly did, I have never, despite that, loved change for change’s sake; travel bores me; I only love a voyage because of the freedom it grants me, as I incline towards the countryside, not for the countryside, but for the solitude. ‘All the heavens are one to me,’ says Montaigne, ‘to live among our own people, to go and murmur and die among strangers.’

I have some other letters from those Eastern lands, which reached their address several months after they were dated. Fathers of the Holy Land, Consuls and families, supposing me to have some power under the Restoration, claimed from me the rights of hospitality: from afar, one is deluded, and believes it to be meaningful. Monsieur Gaspari wrote to me, in 1816, to ask for my help in favour of his son; his letter is addressed: To Monsieur le Vicomte de Chateaubriand, Grand-Master of the Royal University, at Paris.

Monsieur Caffe, not losing sight of what was happening around him, telling me news of his world, sends word from Alexandria: ‘Since your departure, the country has not improved, though peace reigns. Though your Leader has nothing to fear from the Mamelukes, still refugees in Upper Egypt, he must yet be on his guard. The Abd-el-Ouad are still up to their tricks in Mecca. The Manouf canal is to be finished; Mehemet-Ali will be remembered in Egypt for having executed that project, etc.’

On the 13th of August 1816, Monsieur Pangalo, the son, wrote to me from Zea:

‘Monseigneur,

Your Itinerary from Paris to Jerusalem has reached Zea, and I have read, in the midst of my family, what Your Excellency obligingly chose to say of it. Your stay among us was so short that we do not really merit the praise Your Excellency has bestowed on our hospitality, and the overly familiar manner with which we received you. We have also realised, with the greatest satisfaction, that Your Excellency, has been re-appointed due to the latest events, and that you occupy a rank due to your merit as much as your birth. We congratulate you on it, and we hope that, at the pinnacle of greatness, Monsieur le Comte de Chateaubriand will gladly choose to remember Zea, and the numerous family of old Pangalo his host: that family in whom the French consulate has resided since the glorious reign of Louis-le-Grand, who signed our ancestors’ patent. That old man, so enduring, is no more; I have lost my father; I find myself, in mediocre circumstances, charged with supporting the whole family; I have my mother, six sisters to marry off and several widows and their children in my charge. I have recourse to Your Excellency’s goodness; I beg you to come to the aid of my family, in ensuring that the Vice-Consulate of Zea, which is extremely necessary for harbouring the King’s boats, has a salary like the other Vice-Consulates; being agent, as I am, I might be Vice-Consul, with the salary attached to that rank. I believe Your Excellency would find it easy to obtain this request because of my ancestors’ long service, if he would deign to pursue it, and that he will excuse the importunate familiarity of his Zea hosts, who rely on your generosity.

I am with the most profound respect,

Monseigneur,

Your Excellency’s

Very humble and very obedient servant,

Monsieur – G Pangalo.

Zea, the 3rd of August 1816.’

Every time a little laughter rises to my lips, I am punished for it as if it were a fault. This letter made me feel remorse when re-reading a passage (softened, it is true, by expressions of gratitude) regarding the hospitality of our Consuls in the Levant: ‘Mesdemoiselles Pangalo,’ I wrote in the Itinerary, ‘sang in Greek:

Ah! Vous dirai-je, maman?

Monsieur Pangalo, gave little cries, the cockerels crowed, and the memories of Ioulis, Aristaeus, Simonides were completely erased.’

The requests for assistance almost always arrived in the midst of my discredit and woe. Even at the very beginning of the Restoration, on the 11th of October 1814, I received this quite different letter dated from Paris:

‘Monsieur l’Ambassadeur,

Mademoiselle Dupont, of Saint-Pierre et Miquelon, who had the honour of meeting you in those islands, is desirous of obtaining a brief audience with Your Excellency. Since she knows you live in the country, she begs you to let her know a day when you will be coming to Paris, on which you might grant her that audience.

I have the honour to be, etc.

DUPONT’

I had forgotten that young lady, from the epoch when I voyaged over the ocean, so ungrateful is memory! Yet, I had retained a perfect remembrance of the unknown girl who sat by me in those sad frozen Cyclades:

‘A young fisher-girl appeared on the upper slopes of the hill; she had bare legs, despite the cold, and was walking through the dew; etc.’

Circumstances, independent of my will, prevented me from seeing Mademoiselle Dupont. If, by chance, she was Guillaumy’s fiancée, what had been the effect on her of a quarter of a century? Had she suffered from the winters of the New World, or preserved the springtime of those bean-flowers, that sheltered in the moat of Saint-Pierre’s fort?

BkXVIII:Chap3Sec5

In the introduction to an excellent translation of the Letters of Saint Jerome, Messieurs Collombet and Grégoire are pleased to discover in their summary, a resemblance between that saint and myself, apropos of Judea, which with respect I reject. Saint Jerome, in the depths of his retreat, painted a picture of his inward struggles; I would not have found the expression of genius of the inhabitant of that cave in Bethlehem; at the very most, I might have been able to sing with Saint Francis, my patron saint in France and my host at the Holy Sepulchre, his two hymns in Italian of the epoch preceding Dante’s Italian:

‘In foco l’amor mi mise,

In foco l’amor mi mise

(Love sets me in the flames)’

I like to receive letters from overseas; these letters seem to bring me a murmur of their breezes, a ray of their suns, some emanation of the diverse destinies that waves part, and the memories of hospitality bind.

Would I revisit those distant countries? One or two, may be. The skies of Africa produced an enchantment in me which has not vanished; my imagination is still perfumed with the myrtles of the temple of Aphrodite of the Gardens and with the irises of the Cephisus.

Fénelon, on leaving for Greece, wrote the letter to Bossuet you are about to read. The future author of Télémaque reveals himself there with the ardour of a missionary and a poet.

‘Various little incidents kept delaying my return to Paris until now; but at last, Monseigneur, I am leaving, and very nearly airborne. At the prospect of this journey, I meditate on a greater. The whole of Greece is open to me, the wary Sultan retreats; already the Peloponnese breaths in freedom, the Church of Corinth is about to flower again; the voice of the Apostle makes itself heard there still. I feel myself transported to those lovely places among those precious ruins, to sample there, along with the most curious monuments, the very spirit of antiquity. I seek that Areopagus, on which Saint Paul announced the unknown God to the world’s sages; but the profane follows the sacred, and I do not disdain to descend to Piraeus, where Socrates planned out his Republic. I climb to the summit of Parnassus, I gather the laurels of Delphi and I taste the delights of Tempe.

When will the blood of Turks mingle with that of the Persians on the plains of Marathon, and leave all of Greece to religion, philosophy and the fine arts, which regard it as their country?

Arva beata

Petamus arva, divites et insulas.

(let us seek out the fields,

the golden fields, the islands of the blest)

I will not forget you, O island consecrated by celestial visions to the Beloved Disciple, O happy Patmos, I will go and kiss the footsteps of the Apostle on your soil, and I believe I will see the heavens open. There, I will feel myself filled with indignation against the false prophet, who wished to expand the oracles of truth, and I will bless the All-Powerful, who far from throwing down the Church like Babylon, bound the dragon and rendered the Church victorious. I already see the schism ending, East and West reuniting, and Asia seeing the dawn anew after so long a night; earth sanctified by the Saviour’s footsteps and watered with his blood, delivered from those who profane it, and clothed in a fresh glory; and the children of Abraham, scattered through all the earth, and more numerous than the stars of the firmament, who, assembling, at last, from its four corners, will come, en masse, to recognise the Christ they crucified, and reveal a resurrection at the end of time. Enough, Monseigneur, you will be pleased to know that this is my final letter, and an end to my enthusiasm, which bothers you perhaps. Forgive such, in my desire to speak to you from afar, impatient until I might do so from nearer to you.

FR. de FÉNELON.’

Here is the true modern Homer, alone worthy of singing Greece and recounting its beauty to a new Chrysostom.

Book XVIII: Chapter 4: Reflection on my Travels – The Death of Julien

BkXVIII:Chap4Sec1

The sites of Syria, Egypt and the Punic lands were merely places which suited my solitary nature; they pleased me regardless of their antiquity, art and history. I was struck less by the grandeur of the Pyramids than by the desert above which they loomed; Diocletian’s Column held my gaze less than the fringes of sea along the sands of Libya. At the sea-mouth of the Nile, I should have needed no monument to recall this scene depicted by Plutarch:

‘The ex-slave searched up and down the beach until he found the decayed remains of a small fishing boat, sufficient to make a pyre for a poor naked corpse. As he was gathering and assembling it, an old man appeared, a Roman who had served as a youth under Pompey in the wars. “Ah,” said the Roman, “you shall not have this honour all to yourself, I beg you, let me be your companion in so saintly and pious a task, since I shall have no cause for regret after all, owning this recompense for all the hardship I have endured, knowing at least this good fortune, to be able to touch with my hands and help in the burial of the greatest general Rome has known.”’

Caesar’s rival no longer has a tomb in Libya, but a young slave, a Libyan girl, has received, from the hand of a female Pompey, a grave not far distant from that Rome from which the great Pompey was banished. In the face of these vagaries of fate, one understands why the Christians went and hid themselves in the Thebaid.

‘Born in Libya, buried in the flower of my youth beneath the Italian dust, I lie near Rome by this sandy shore. The illustrious Pompeia who raised me with a mother’s tenderness, mourned my death and placed me in a tomb that rivals, I a poor slave, those of free Romans. The torches of my funeral have forestalled those of marriage. Proserpine’s flame has quenched my hopes.’ (Palatine Anthology)

The winds have scattered those individuals of Europe, Asia, and Africa, amongst whom I appeared and of whom I have spoken: one wind blew from the Acropolis of Athens, another from the shores of Chios; this one poured from Mount Sion; that one will no longer escape the waves of the Nile or the wells of Carthage. The places have also altered; towns rise, just as in America, where I saw forests, an empire likewise is being created among the sands of Egypt, where my eyes met only horizons naked and round as the boss of a shield, as Arabic poetry says, and jackals so thin that their jaws are like a split stick. Greece has regained that freedom that I desired for her when I traversed her beneath the janissary’s gaze. But does she enjoy a national liberty or has she only changed her yoke of servitude?

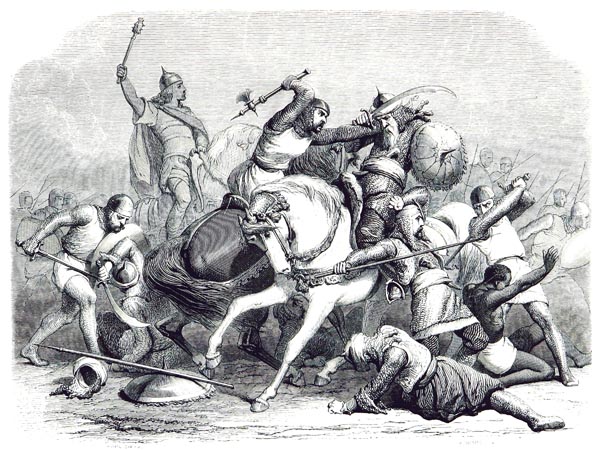

I am in some ways the last visitor to the Turkish Empire in its previous form. The revolutions, which have immediately preceded or followed my steps, everywhere, have extended to Greece, Syria and Egypt. Is a new Orient about to be created? What will emerge? Will we receive due punishment for having taught the art of modern warfare to nations whose social structure is founded on slavery and polygamy? Have we exported civilisation to the outside world or have we imported barbarity to the heart of Christendom? What will result from these new interests, from these new political relationships, from the creation of powers which may suddenly surge through the Levant? No one can say. I do not allow myself to be dazzled by steamships, and railroads; by the sale of manufactured products or the wealth of French, English, German and Italian soldiers enlisted in the service of some Pasha or other: all that is not civilisation. Perhaps we will again see, in the disciplined troops of future Ibrahims, the dangers which menaced Europe in the time of Charles Martel, and from which, much later, Polish sacrifice saved us. I pity the travellers who will follow me: the harem will not conceal its secrets from them: they will not see the old sun of the Orient, or the turban of Mohammed. The little Bedouin cried out to me in French when I was travelling in the mountains of Judea: ‘Onward march!’ The order has been given, and the Orient is on the march.

‘Bataille de Tours en 732’

Promenades Pittoresques en Touraine. Histoire, Légendes, Monuments, Paysages...Gravures...d'Après Karl Girardet et Français - Casimir Chevalier, Carl Girardet, Louis Français (p327, 1869)

The British Library

What became of Julien, Ulysses’ friend? He requested of me, in submitting his manuscript to me, that he might become the concierge of my house on the Rue d’Enfer: that situation was occupied by an old doorman and his family whom I could not dismiss. The will of heaven having made Julien self-willed and a drunkard, I supported him for a long time; finally, we were obliged to part. I gave him a small sum of money and allowed him a tiny pension from my privy purse, a light enough one, but always copiously filled with excellent mortgage receipts from my castles in Spain. I made Julien enter the Hospice for the Old according to his own wish: there he completed the last and greatest voyage. I will soon occupy his empty bed, as I once slept, in the Khan of Demir-Capi, on the mat from which they had just removed a plague-ridden Muslim. My calling is definitely to be found in some hospital or in the midst of the old society, which makes a semblance of being alive and is none the less involved in its own death-pangs. When it expires, it will decompose in order to reproduce itself in new forms, but it must first succumb; the primary necessity for nations, like men, is to die: ‘By the breath of God the frost is given’, says Job.

Book XVIII: Chapter 5: The Years 1807, 1808, 1809 and 1810 – An article in the Mercury, June 1807 – I buy the Vallée-Aux-Loups and retreat there

Paris, 1839 (Revised June 1847)

BkXVIII:Chap5:Sec1

Madame de Chateaubriand had been very ill during my voyage; my friends several times thought me lost. In letters which Monsieur de Clausel wrote to his children and which he has kindly allowed me to read, I find this passage:

‘Monsieur de Chateaubriand left on his voyage to Jerusalem in the month of July 1806: during his absence I went to Madame de Chateaubriand’s house every day. Our traveller did me the kindness to write to me a lengthy letter, from Constantinople, which you will find in the drawer in our library at Coussergues. During the winter of 1806 and 1807, we knew that Monsieur de Chateaubriand was at sea returning to Europe; one day, I was walking in the Tuileries Gardens with Monsieur de Fontanes in the teeth of a dreadful westerly wind; we were sheltering beneath the terrace by the water’s edge. Monsieur de Fontanes said to me: – Perhaps at this very moment, a gust from this terrible storm will cause his shipwreck. We have since learnt that this presentiment failed to be realised. I note this to express the lively friendship, the interest in Monsieur de Chateaubriand’s literary glory, which was bound to increase with that voyage; the noble, the profound and rare sentiments which animated Monsieur de Fontanes, that excellent man from whom I too have had great service, and whom I recommend you to remember before God.’

If I had been certain to survive, and if I could have perpetuated in my works those people who are dear to me, with what pleasure I would have taken my friends along with me!

Full of hope, I carried my handful of gleanings back home; my peace and quiet was not of long duration.

After a series of agreements, I became sole proprietor of the Mercure.

Towards the end of June 1807, Monsieur Alexandre de Laborde published his travels in Spain; in July, I published the article in the Mercury from which I have quoted various passages in speaking of the Duc d’Enghien’s death: When in the silence of abjection, etc. Bonaparte’s successes, far from subduing me, had provoked me; I had gained fresh energy from my feelings and the tempests. My face had not been bronzed by the sun in vain, nor had I exposed myself to the wrath of the heavens in order to tremble sad-browed before a merely human anger. If Napoleon had done with kings, he had not done with me. My article, appearing in the midst of his successes and triumphs, stirred France: innumerable copies were made by hand; several subscribers to the Mercure cut out the article and had it bound separately; it was read in the salons and hawked from house to house. One has to have lived at that moment to gain any idea of the effect produced by a lone voice ringing out amongst the silence of the world. Noble feelings, buried in the depths of men’s hearts, revived. Napoleon was furious: one is less irritated by the criticism made than by its attack on one’s self-image. What! To scorn even his glory; for a second time, to brave the anger of one at whose feet the world had fallen, prostrate! ‘Does Chateaubriand think I am an imbecile: that I don’t comprehend him? I’ll have him cut down on the steps of the Tuileries!’ He gave orders to suppress the Mercure, and for my arrest. My property was lost; my person escaped by a miracle: Bonaparte was pre-occupied by the wider world; he forgot me, but I remained weighed down by menace.

My situation was deplorable: while I felt I had to act according to my sense of honour, I found myself burdened with personal responsibilities, and the anxieties I was causing my wife. Her courage was great, but she none the less suffered, and these storms falling in succession on my head troubled her life. She had suffered so much on my behalf during the Revolution! It was natural that she longed for a little peace. The more so in that Madame de Chateaubriand admired Bonaparte without reservation; she had no illusions about the Legitimacy; she was forever predicting what would happen to me if the Bourbons returned.

The first chapter of these Memoirs is dated the 4th of October 1811, at the Vallée-aux-Loups: there will be found my description of the little retreat which I purchased to hide myself in, at that time. Leaving our apartment at Madame de Coislin’s, we went to live in the Rue des Saints-Pères, in the Hôtel de Lavalette, which took its name from the owners of the place.

Monsieur de Lavalette, stocky, dressed in a violet-coloured morning-coat, and carrying a gold-knobbed cane, had become my business manager, if indeed I have ever had any business. He had been a cup-bearer in the Royal household, and what I did not eat, he drank.

BkXVIII:Chap5:Sec2

Towards the end of November, seeing that the repairs to my cottage were making no progress, I decided to go and supervise them. We arrived at the Vallée in the evening. We did not take the usual road; we entered through the gate at the end of the garden. The soil in the drives, soaked with rain, prevented the horses from going on; the carriage overturned. The plaster bust of Homer, placed beside Madame de Chateaubriand, was thrown through the window, and shattered its neck: a bad omen for Les Martyrs on which I was then working.

The house, filled with laughing, singing, hammering workmen, was warmed by a fire of wood-shavings and lit by candle-ends: it resembled a hermitage in the woods illuminated at night by pilgrims. Delighted to find two rooms quite passable, in one of which a table had been laid, we sat down to dine. Next day, awakened by the noise of hammering, and the songs of the colonists, I watched the sun rise with less anxiety than that master of the Tuileries.

I was surrounded by endless enchantments; though no Madame de Sévigné, I went out, furnished with a pair of clogs, to plant trees in the mud, traverse the same walks over and over, look once and again into every little corner, conceal myself wherever there was a clump of bushes, imagining what my park would be like in the future, since then the future was uncompromised. Searching, today, to re-open that vista which has closed, I no longer find that same one indeed, though I meet with others. I lose myself among vanished memories; perhaps the illusions I come across are as lovely as those earlier ones; only they are not as youthful; what I saw in the splendour of noon, I perceive in the glow of evening. – If only I might cease to be plagued by dreams! Bayard, ordered to relinquish a position, replied: ‘See, I have made a bridge of corpses, in order to cross over it to the garrison.’ I fear that in order to depart, I must pass over the bodies of my illusions.

My trees, being still quite small, were not filled with the sound of the autumn winds; but, in spring, the breezes that breathed the flowery fragrance of the neighbouring fields held their breath, and released it over my valley.

Our Sentimental Journey through France and Italy - Elizabeth Robins Pennell (p197, 1888)

The British Library

I made a few additions to my cottage; I embellished its brick wall with a portico supported by two black marble columns and two white marble caryatids: I remembered I had been to Athens. My plan was to add a tower to the end of the building; in the meantime, I simulated battlements along the wall that bordered the road: thus I anticipated the obsession regarding the Middle Ages which currently stupifies us. Of all the possessions I have lost, the Vallée-aux-Loups is the only one I regret; it is written that nothing will remain to me. After my Valley was lost, I planted out the Marie-Thérèse Infirmary, and I have just left that too. I defy fate to attach me to the smallest plot of earth now; henceforth, I will only have as my garden those avenues, honoured with such fine names, around the Invalides, where I walk with my lame and one-armed colleagues. Not far from these walks, Madame de Beaumont’s cypress lifts its head; in these deserted spaces, the great, light-hearted Duchesse de Châtillon once leant on my arm. I only give my arm to time, now: who is heavy enough!

I worked at my Memoirs with pleasure, and Les Martyrs progressed; I had already read several chapters to Monsieur de Fontanes. I was established amongst my memories as in a vast library: I consulted here, and then there and finally closed the volume with a sigh, when I perceived that the light, by penetrating, destroyed the mystery. Shed light on the days of your life, and they will no longer be as they were.

In July 1808, I fell ill, and was obliged to return to Paris. The doctors rendered the illness dangerous. While Hippocrates was living, there was a lack of dead spirits in Hades, says the epigram: thanks to our modern Hippocrates, there is no shortage today.

That was perhaps the only time when, near to death, I longed for life. When I felt myself to be weaker, which often happened, I would say to Madame de Chateaubriand: ‘Don’t worry; I will recover.’ I would lose consciousness, but with a mounting impatience within, since I was holding on, God knows to what. Also I was possessed with desire to complete what I thought, and still think, to be my most perfect work. I was reaping the reward for the fatigue I had often experienced during my travels in the Levant.

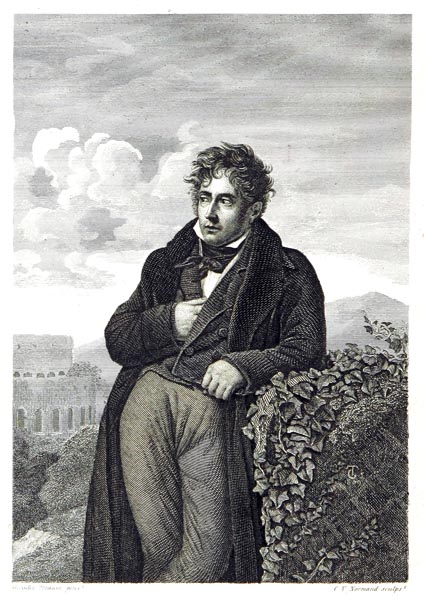

Girodet had given the last touches to my portrait. He made it melancholy, as I then was; but he filled it with his genius. Monsieur Denon accepted the masterpiece for the Salon; as a noble courtier he placed it prudently out of the way. When Bonaparte arrived to review the gallery, he looked at the paintings and then asked: ‘Where is the portrait of Chateaubriand?’ He knew it must be there: they were obliged to lift the curtain on its hiding place. Bonaparte, exhaling a fulsome breath, said, on gazing at the portrait: ‘He has the air of a conspirator who has come down the chimney.’

‘V. de Chateaubriand’

La Bretagne Ancienne et Moderne. Illustré - Pitre-Chevalier (p14, 1859)

The British Library

On returning to the Vallée alone one day, Benjamin, the gardener, told me that a large foreign gentleman had come asking for me; that on finding me not there, he had declared his intention of waiting for me; that he had ordered an omelette and had then laid himself down on my bed. I walked upstairs, entered my bedroom, and saw something huge asleep; shaking this mass, I shouted: ‘Hey! Hey! Who is this?’ The mass quivered and sat up. Its head was covered with a hairy bonnet, it wore a matching jersey and trousers of flecked wool, its face was stained with snuff and its tongue was sticking out. It was my cousin Moreau! I had not seen him since camp at Thionville. He was back from Russia and wished to enter public service. My old cicerone in Paris was off to die at Nantes. So there vanished one of the principal characters in my Memoirs. I hope that, extended on a bed of asphodel, he still speaks of my verses, to Madame de Chastenay, if that delightful shade has descended to the Elysian Fields.

Book XVIII: Chapter 6: Les Martyrs

BkXVIII:Chap6:Sec1

In the spring of 1809 Les Martyrs was published. It was a work of conscience: I had consulted critics of knowledge and taste in Messieurs Fontanes, Bertin, Boissonade, and Malte-Brun, and I had submitted to their arguments. I wrote, un-wrote and re-wrote the same pages a hundred times and more. Of all my writings, it is the one where the language is most perfect.

I was not mistaken in my plan; now that my ideas have become common currency, no one denies that the struggle between two religions, the one ending, the other beginning, offers the Muses one of the richest, most fertile and most dramatic of subjects. So I thought I might nourish some not too outlandish hopes; but I forgot about the success of my first work: in this country, never count on two successes close together; one destroys the other’s chances. If you have any talent for prose, take care not to reveal yourself in verse; if you are a distinguished man of letters, have no pretensions towards politics: such is the French spirit and its miseries. Self-esteem alarmed, and envy surprised by some author’s happy debut, band together and lie in wait for the poet’s second publication, in order to take a glittering revenge:

Every hand at the inkwell, swore to be revenged.

I had to pay for the foolish admiration I had gained by fraud on publication of Le Génie du Christianisme; I was forced to return what I had stolen. Alas! It was not necessary to put me through so much pain to rob me of that which I myself did not think I merited! If I had saved Christian Rome, I only requested an obsidional crown, of wreathed grasses gathered in the Eternal City.

The executor of justice in regard to all vanities was Monsieur Hoffman, to whom may God bring peace! The Journal des Débats was no longer free; its proprietors no longer had power over it, and censorship consigned me to condemnation there. Yet Monsieur Hoffman showed mercy towards the Battle of the Franks and several other bits of the work; if Cymodocée however seemed fine to him, he was too good a Catholic not to be indignant at the profane encounter of Christian truth with Mythological fable. Velléda could not save me. I was accused of the crime of having transformed Tacitus’ Druid cousin into a Gaul, as if I had wanted anything more than to borrow her harmonious name! Bless me, if the French Christians, to whom I have rendered such great service in raising their altars once more, hadn’t suddenly decided in their stupidity to be scandalised by Monsieur Hoffman’s evangelical speech! The title of Les Martyrs had deceived them; they expected to read a martyrology, and a tiger, which only tore apart a daughter of Homer, seemed to them a sacrilege.

The true martyrdom, of Pope Pius VII whom Bonaparte had brought to Paris as his captive, caused no scandal, but they were all stirred by my fictions, which displayed little Christianity, they said. And it was the Bishop of Chartres who took it upon himself to mete out justice in regard to the terrible impieties of the author of Le Génie du Christianisme. Alas! One must say that these days his zeal is required in a good many other causes.

The Bishop of Chartres is the brother of my excellent friend, Monsieur de Clausel, a very fine Christian who will not allow himself to be carried away by as sublime a virtue as his brother, the critic.

I thought I ought to reply to this censure, as I had done in regard to Le Génie du Christianisme. Montesquieu, with his defence of L’Esprit des Lois, was my example. I was in error. Authors who are attacked may make the finest reply in the world, but only raise a smile from impartial minds and mockery from the crowd. They place themselves on treacherous ground: a defensive stance is antipathetic to the French character. When, in order to respond to the objections, I showed that in stigmatising such and such a passage, one was attacking some fine relic of antiquity; defeated by the facts, they abandoned the affair saying then that Les Martyrs was merely a pastiche. If I justified the simultaneous presence of two religions by employing the authority of the Fathers of the Church, they replied that in the era in which I had set the action of Les Martyrs, paganism no longer existed as far as great minds were concerned.

I thought in all good faith that the work had failed; the violence of the attack had shaken my confidence as an author. Friends consoled me; they maintained that the proscription was unjustified, that the public, sooner or later, would take a different view; Monsieur de Fontanes especially stood firm: I was not Racine, but he could have been Boileau, and he never stopped saying to me: ‘They will come round to it.’ His persuasiveness in this regard was so profound that it inspired him to delightful verse:

‘Tasso, wandering from town to town, etc. etc.’

- without fear of compromising his taste or the authority of his judgement.

Indeed Les Martyrs revived; it achieved the honour of four consecutive editions; it has even enjoyed special favour among men of letters: they were grateful to me for a work which testified to serious study, to some care for style, to an elevated respect for language and taste.

The criticism of its content was swiftly abandoned. To say that I had intermingled the sacred and the profane, because I had depicted two cults existing side by side, each of which had its adherents, its altars, its priests, its ceremonies, was to say that I should have renounced all claim to be writing history. For whom did the martyrs die? – For Jesus Christ. Whom were they sacrificed to? – To the gods of the Empire. There were two religions, then.

The philosophical question, as to whether, under Diocletian, the Romans and Greeks believed in the gods of Homer, and whether public observance underwent change, that question, as a poet, did not concern me; as a historian I would have had much to say.

All of that is no longer an issue. Les Martyrs lives on, contrary to my initial expectation, and I have only had to occupy myself in carefully revising the text.

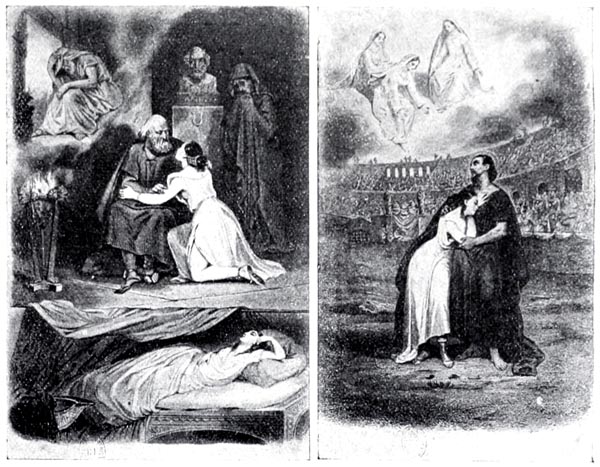

The failings of Les Martyrs lie in the direct presentation of the marvellous which, along with the rest of my Classical prejudices, I employed at the wrong moments. Frightened of innovation, it seemed impossible to me to avoid hell and heaven. The good and evil angels however were adequate for the course of the action, without delivering it over to hackneyed mechanisms. If the Battle of the Franks, Velléda, Jérôme, Augustine, Eudore, Cymodocée; if the descriptions of Naples and Greece could not obtain mercy for Les Martyrs, it was not for heaven and hell to rescue it. One of the passages most pleasing to Monsieur de Fontanes was this.

‘Cymodocée sat in front of the prison window, and resting her head, adorned with a martyr’s veil, on her hand, sighed out these harmonious words:

“Fragile Italian vessels, cleave the calm and shining sea; slaves of Neptune, abandon your sails to the amorous breath of the winds, bend to the brisk oar. Return me to the protection of my husband and my father, by the happy banks of Pamisus.

Fly, Libyan birds, whose sinuous necks curve so gracefully, fly to the summit of Ithome, and say that a daughter of Homer goes to gaze on the laurels of Messene once more!

When shall I return to my bed of ivory, to the light of day so dear to mortals, to the meadows scattered with flowers that a pure stream waters, that modesty adorns with its breath!”’

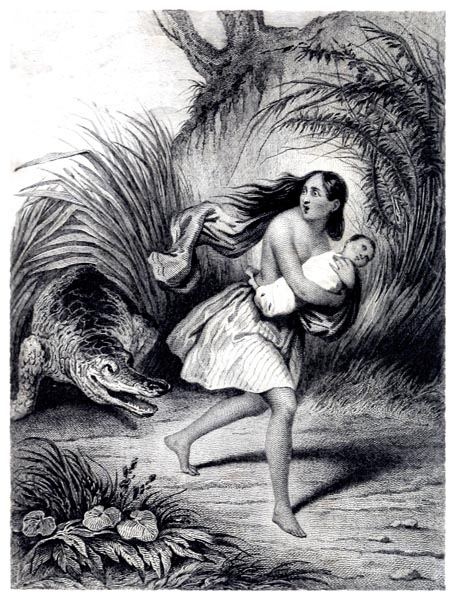

‘Deux scènes des « Martyrs »

À gauche Cymodocèe dans son milieu païen, auprès de son père Démodocus...À droite,Cymodocèe, martyre du christianisme, au moment où elle aperçoit le tigre.’

Morceaux Choisis: Extraits des Oeuvres Complètes - Vicomte de François-René Chateaubriand (p330, 1915)

Internet Archive Book Images

Le Génie du Christianisme will remain my great work, because it produced or orchestrated a revolution in thought, and began a new era in the century’s literature. It was not the same with Les Martyrs; it came after that revolution had been carried through, it was merely an overabundant demonstration of my thesis; my style was no longer a novelty, and, except in the episode of Velléda and in the depiction of the manners of the Franks, my poem even suffers from the places which it frequented: the classical in it dominates the romantic.

Finally, the circumstances which contributed to the success of Le Génie du Christianisme no longer existed; the government, far from favouring me, was opposed to me. Les Martyrs earned me a redoubling of my persecution: the striking allusions shown in the portrait of Galerius and the depiction of Diocletian’s court did not escape the Imperial police; particularly since the English translator, who had no responsibilities to guard, and to whom it was all the same if he compromised me, highlighted the allusions in his preface.

The publication of Les Martyrs coincided with a fatal incident. It did not disarm the critics, graced with the ardour with which we grow heated in the corridors of power; they felt that literary criticism which tended to diminish the interest attached to my name might be agreeable to Bonaparte. He, like those millionaire bankers who give grand dinners and charge one for posting one’s letters, did not neglect his lesser profits.

Book XVIII: Chapter 7: Armand de Chateaubriand

BkXVIII:Chap7:Sec1