François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book XIV: Travels in the Midi, Napoleon, Rome 1802-1803

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book XIV: Chapter 1: The years 1802 and 1803 – Châteaux – Madame de Custine – Monsieur de Saint-Martin – Madame d’Houdetot and Saint-Lambert

- Book XIV: Chapter 2: Travels in the French Midi (1802)

- Book XIV: Chapter 3: The years 1802 and 1803 – Monsieur de Laharpe: his death

- Book XIV: Chapter 4: The years 1802 and 1803 – Interview with Napoleon

- Book XIV: Chapter 5: The year 1803 – I am named as First Secretary to the Embassy in Rome

- Book XIV: Chapter 6: The year 1803 – Journey from Paris to the Savoy Alps

- Book XIV: Chapter 7: From Mont Cenis to Rome – Milan and Rome

- Book XIV: Chapter 8: Cardinal Fesch’s palace – My tasks

Book XIV: Chapter 1: The years 1802 and 1803 – Châteaux – Madame de Custine – Monsieur de Saint-Martin – Madame d’Houdetot and Saint-Lambert

Paris, 1837 (Revised in December 1846)

BkXIV:Chap1:Sec1

My life became utterly confused as soon as it ceased to be mine. I had a crowd of acquaintances instead of my usual friends. I was invited to country houses that had been restored. People returned willy-nilly to those half-unfurnished half-furnished manors, where an old armchair stood alongside a new armchair. However, some of these manor houses were still intact, such as Le Marais, inherited by Madame de La Briche, an excellent woman whose good fortune was unavoidable. I remember that My Immortality went to the Rue Saint-Dominique-d’Enfer to take a seat for Le Marais in a wretched hired carriage, where I joined Madame de Vintimille and Madame de Fezensac. At Champlâtreux, Monsieur Molé had done up a few small rooms on the second floor. His father, executed during the Revolution, was represented by a painting, in a large dilapidated sitting room, in which Mathieu Molé was depicted, preventing a riot with a mitred hat: a painting which made the difference in epochs apparent. Part of a superb trio of radiating lime-tree avenues had been felled; but one of the three avenues still survived with all the magnificence of its former foliage; it has since been merged with new plantings: and we are among poplar-trees.

On return from emigration, there was no exile so poor he did not design the windings of an English garden for the ten feet of earth or courtyard he had recovered: did I myself not long ago plant out the Vallé-aux-Loups? Did I not begin these Memoirs there? Did I not continue them in the park at Montboissier, where they were trying to revive its appearance disfigured by neglect? Did I not continue them in the park at Maintenon restored not long ago, a new target for the coming democracy? The country houses burnt in 1789 should have served as a warning to the rest of those houses to remain concealed among their ruins: though the steeples of engulfed villages piercing the lava of Vesuvius do not prevent other churches and hamlets being re-established on that same lava.

Among the bees building their hive, was the Marquise de Custine, inheritor of the long tresses of Marguerite de Provence, the wife of Saint Louis, whose lineage she shared. I helped her take possession of Fervaques, and had the honour of sleeping in the Bearnais’ bed, as I had slept in that of Queen Christina at Combourg. It was no trivial business that journey; the carriage was required to receive Astolphe de Custine, her son, Monsieur Berstecher, the tutor, an old maid from Alsace who spoke only German, Jenny the chambermaid, and Trim, a famous dog, who ate the provisions for the journey. One would have thought these colonists were returning to Fervaques forever! And yet no sooner was the chateau re-furnished than the signal to leave was given. I have seen that woman who faced the scaffold with such great courage, I have seen her, whiter than one of the Fates, dressed in black, her body deathly thin, her head adorned only with her silken hair, I have seen her smile at me, her lovely teeth between pale lips, as she left Sécherons, near Geneva, to die at Bex, at the entrance to the Valais; I have heard her coffin go past at night in the empty streets of Lausanne to occupy its eternal place at Fervaques: she hastened to be buried in the earth that, like life, she had possessed for barely a moment. I have read in a chimney-corner in her chateau these risqué lines attributed to Gabrielle’s lover:

‘The lady of Fervaques

Warrants boldness of attack.’

The soldier-king had claimed as much of many others: man’s fleeting declarations, swiftly effaced and transferred from beauty to beauty, down to Madame de Custine. Fervaques has been sold.

I had met the Duchesse de Châtillon once more who, in my absence during the Hundred Days, adorned my valley of Aulnay. Madame Lindsay, whom I had never ceased seeing, introduced me to Julie Talma. Madame de Clermont-Tonnerre enticed me to her house. We had a grandmother in common, and she clearly wished to call me her cousin. The widow of the Comte de Clermont-Tonnere, she later married the Marquis de Talaru. In prison, she had converted Monsieur Laharpe. It was through her that I met the painter Neveu, enrolled among her cavalier-servantes. Neveu soon put me in touch with Saint-Martin.

BkXIV:Chap1:Sec2

Monsieur de Saint-Martin thought he had found certain hidden words in Atala of which I had no suspicion myself, and which proved to him that our ideas were related. Neveu, in order to unite these two brothers, had us to dinner in an upper room he inhabited in the outbuildings of the Palais-Bourbon. I arrived at the rendezvous at six; the philosopher of the heavens was already at his post. At seven, a discreet servant served some soup, retired and closed the door. We sat down and began to eat in silence. Monsieur de Saint-Martin, who, at other times, had very fine manners, only spoke a few short oracular words. Neveu replied with exclamations, changes of posture, and painterly grimaces: I said not a word.

At the end of half an hour, the necromancer returned, took away the soup and left another plate on the table: new dishes arrived thus one by one at long intervals. Monsieur de Saint-Martin, gradually warming up, began to speak like an archangel; the more he spoke, the more obscure his language became. Neveu had insinuated to me, while shaking my hand, that we would see extraordinary things, that we would hear noises: for six mortal hours I listened, and experienced nothing. At midnight, the visionary suddenly rose: I thought the spirit of darkness, or the divine spirit was descending, that bells would ring out in mysterious corridors; but Monsieur de Saint-Martin declared that he was tired, and that we would renew the conversation some other time; he took his hat and went. Unfortunately for him, he was stopped at the door and forced to return by an unexpected visitor: nevertheless he was not long in vanishing. I never saw him again: he rushed off to die in the garden of Monsieur Lenoir-Laroche, my neighbour at Aulnay.

I was an unruly subject for Swedenborgianism: the Abbé Faria, at a dinner at Madame de Custine’s, boasted he would kill a canary by magnetising it: the canary was all the livelier for it, and the Abbé, beside himself, was forced to leave the company, for fear of being killed by the canary: a Christian, my presence alone had rendered the experiment vain.

On another occasion, the celebrated Gall, a frequenter of Madame Custine’s, dined beside me without knowing who I was, made an error concerning my facial planes, took me for a frog and, when he knew who I was, wished to rescue his science, in such a way as to make me ashamed for him. The shape of the head can aid in distinguishing the sex of an individual, in indicating what belongs to the creature, to the animal passions; as for the intellectual faculties, phrenology is forever ignorant of them. If one could gather together the various skulls of the great men who have died since the world began, and set them before the eyes of phrenologists without telling them to whom they belonged, they would not match a single brain correctly: the study of bumps produced the most comical errors.

‘François-Joseph Gall’

Jean Marius (1798 - ?)

Images from the History of Medicine - US National Library of Medicine

I feel some remorse: I have spoken of Monsieur de Saint-Martin, with a degree of mockery, and I repent. This tendency to mockery which I repress and which continually emerges in me causes me suffering; since I despise the satirical spirit as the meanest, the commonest and most trivial of all; of course I do not mean here the proceedings of high comedy. Monsieur de Saint-Martin was, in the final result, a man of great merit, with a noble and independent character. When his ideas were explicable, they were lofty and of a superior nature. Ought I not to sacrifice the two preceding pages to the generous and much too flattering statements of the author of the Portrait de Monsieur de Saint-Martin drawn by himself? I would not hesitate to erase them, if what I say might harm, to the least degree in the world, Monsieur de Saint-Martin’s great fame, and the esteem which will forever be attached to his memory. Besides I note with pleasure that my recollection is not at fault: Monsieur de Saint-Martin may not have been struck in an absolutely identical manner as I by the dinner of which I speak; but one can see that I have not invented the scene, and that Monsieur de Saint-Martin’s description basically resembles mine.

‘On the 27th of January 1803,’ he says, ‘I met with Monsieur de Chateaubriand at a dinner arranged for that purpose, at Monsieur Neveu’s, at the École Polytechnique. I would have much to gain by knowing him further: he is the only honest man of letters in whose presence I have been since I was born, and even then I only enjoyed his conversation over the meal. For immediately afterwards a visitor arrived who rendered him silent for the rest of the session and I do not know when the occasion might present itself again, since the ruler of this world has a great longing to put a spoke in the wheel of my cart. As for that, whom do I desire, but God?’

Monsieur de Saint-Martin was a thousand times better than I; the dignity of that last phrase crushes my inoffensive mockery with the weight of grave human character.

I had seen Monsieur de Saint-Lambert and Madame d’Houdetot at Le Marais, both of whom represented the opinions and freedoms of other days, carefully preserved and mounted; it was the eighteenth century, dead, and fixed in place. It is enough to survive in life, for the illegitimate to become legitimate. One acquires an infinite esteem for immorality, merely because it has not ceased to be, and because time has adorned it with wrinkles. In truth, they were two virtuous spouses, who were not spouses, and who remained united by human regard, suffering somewhat from their venerable state; they were bored with and cordially detested themselves with all the bad humour of old age: that is God’s justice.

‘Misfortune, to which the gods grant long years!’

It was difficult to understand various pages of the Confessions, when one had seen the object of Rousseau’s transports: had Madame d’Houdetot kept the letters Jean-Jacques wrote to her, and which he claimed to have been more brilliant than those of his Nouvelle Héloïse? One thinks she sacrificed herself to Saint-Lambert.

At nearly eighty years of age, Madame d’Houdetot could still write, in these pleasant lines:

‘Love consoles me, indeed!

Nothing will console me for him.’

She never retired to bed without having struck the floor three times with her slipper, while calling to the late author of Les Saisons: ‘Goodnight, dear friend!’ That was what the philosophy of the eighteenth-century was reduced to, in 1803.

That society of Madame d’Houdetot, Diderot, Saint-Lambert, Rousseau, Grimm, and Madame d’Épinay, rendered the valley of Montmorency insupportable to me, and though, in the course of events, I might take comfort from the fact that a relic of Voltaire’s age appeared before my eyes, I have no regrets for those times. I had already seen at Sannois, the house where Madame d’Houdetot lived; it was no more than a ruined shell, reduced to four walls. An abandoned fireplace is always of interest; but what do those hearths say where neither beauty, nor the mother of a family, nor religion have sat, and whose ashes, if they have not been dispersed, only return the memory to days which have only known how to destroy?

Book XIV: Chapter 2: Travels in the French Midi (1802)

Paris, 1838

![France [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Chateaubriand/interior_chateaubriand_memoirs_bk14chap2.jpg)

‘France [Detail]’

Histoire des Villes de France, Vol 06 - Aristide Guilbert (p869, 1844)

The British Library

BkXIV:Chap2:Sec1

A pirated version of Le Génie du Christianisme, produced at Avignon, summoned me to the French Midi in the month of October 1802. I was only familiar with my humble Brittany and the Northern provinces, which I crossed when I left the country. I went to see the sun of Provence, that sky which would grant me a foretaste of Italy and Greece, towards which my instincts and my Muse drove me. I was in a cheerful mood; my reputation made life pleasant: there are a host of dreams associated with the first intoxication of fame, and the eyes are filled at first with delight in a rising star; but when the star fades, it leaves you in darkness; if it lasts, the habitual sight soon makes you insensible to it.

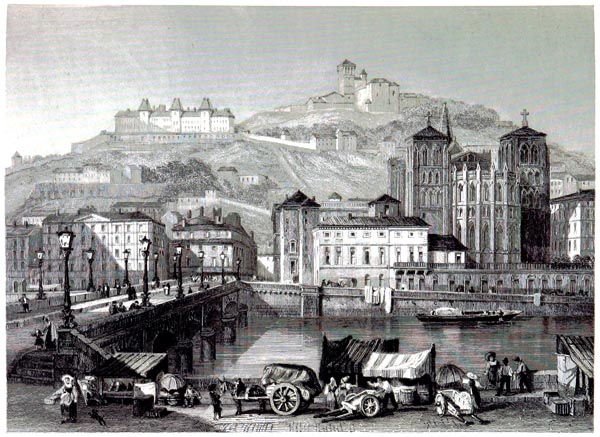

Lyon gave me a deep pleasure. I discovered the architecture of the Romans that I had not seen since the day when I read those pages of Atala, pulled from my haversack, in the amphitheatre at Trèves. Small sailing boats crossed the Saône from shore to shore, carrying lights at night; women piloted them; a sailor girl of eighteen, who accepted me on board, re-adjusted the cluster of flowers pinned to her hat, after every stroke of the oar. I was woken each morning by the sound of bells. The monasteries suspended from the hillsides seemed to have regained their hermits. Monsieur Ballanche’s son, owner of the printing rights to Le Génie du Christianisme after Monsieur Migneret, was my host: he became my friend. Who today does not know the Christian philosopher, whose writings shine with that peaceful clarity, on which one delights in casting one’s gaze, as on the rays of a friendly star in the sky?

‘Lyon - Côte de Fourvières’

Histoire des Villes de France, Vol 01 - Aristide Guilbert (p445, 1844)

The British Library

On the 27th of October, the mail-boat which carried me to Avignon, was forced to moor at Tain, because of a storm. I thought I was in America: the Rhône looked like my vast rivers of the wilderness. I was holed up in a little inn, at the edge of the water; a conscript stood by a corner of the hearth; he had his rucksack on his back and was off to rejoin the Army of Italy. I wrote on the chimney bellows, facing the hotelier, who sat in silence before me, and who, out of consideration for the traveller, prevented the cat and dog from making any noise.

What I was writing was an article, which I had almost completed on the preceding trip down the Rhône, relating to Monsieur de Bonald’s La Législation primitive. I foresaw what has since happened: ‘French literature,’ I said, ‘is changing its aspect; new thoughts and new views on men and things were born with the Revolution. It is easy to foresee that writers will be divided. Some will strive to follow the old paths; others will endeavour to follow classical models, but present them however in a new light. It is quite likely that the latter will end by getting the upper hand over their adversaries, since by relying on the great tradition and great men they will possess the most trustworthy guides and the most fertile sources.’

The lines which ended my criticism-while-travelling were historic; from that moment my spirit was in tune with my age; ‘The author of this article,’ I wrote, ‘cannot resist an image presented to him by the place in which he finds himself. At the very moment he writes these words, he is descending one of France’s great rivers. On two mountains opposite twin ruined towers rise; at the summit of those towers little bells are fixed which the people of these hills ring to mark our passage. This river, those mountains, these bells, those Gothic monuments delight the spectators’ eyes for a moment; but no one stops to pursue the bell’s invitation. So men who preach morality and religion today, send out their signals in vain, from the height of their ruins, to those whom the torrent of the age drags along; the traveller is astonished by the greatness of what remains, by the sweetness of the sound which echoes from it, by the majesty of the memories which inspired it, but he makes not a single alteration to his course, and at the next bend of the river, all is forgotten.’

Arriving at Avignon on All Saint’s Eve, a child offered me some books he was carrying: I bought at a stroke three different pirated editions of a little story called Atala. By going from bookshop to bookshop, I unearthed the counterfeiter, to whom I was unknown. He sold me the four volumes of Le Génie du Christianisme, at the reasonable price of nine francs a copy, and made me a grand eulogy of the work and the author. He lived in a fine house between a courtyard and a garden. I considered I had caught the magpie in its nest: at the end of twenty-four hours, I grew bored with chasing wealth, and came to an arrangement with the thief for a trivial amount.

I saw Madame de Janson, a cold little woman, white and resolute, who battled with the Rhône on her property, exchanging gunshots with the riverside dwellers, and defending herself against the years.

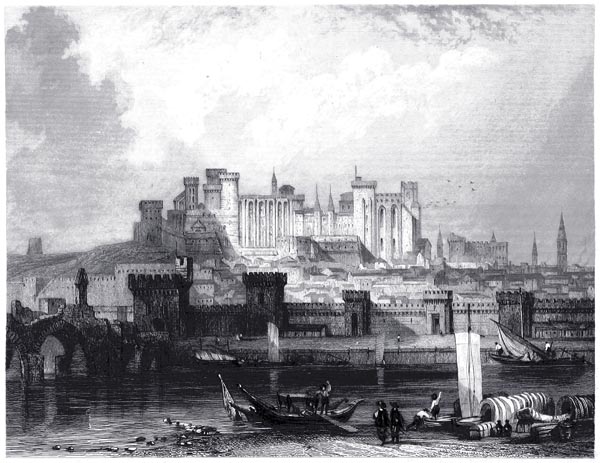

Avignon reminded me of a compatriot. Du Guesclin easily rivalled Bonaparte, since he saved France from conquest. Reaching this city of the Popes, with the adventurers whom his fame was leading into Spain, he said to the provost sent to him by the Pontiff: ‘Brother, don’t deceive me: from whom did this treasure come? Has the Pope dipped into his treasure?’ He replied in the negative, and that the residents of Avignon had each paid their portion. ‘Then,’ said Bertrand, ‘provost, I swear to you that we will not touch a penny of it, and we wish the money collected to be repaid to those who gave it, and tell the Pope clearly that he must return it to them: for if I hear to the contrary, it will weigh upon me; and having already crossed the sea, so I will return here.’ Then Bertrand was paid the ransom by the Pope, and his men immediately absolved, and the aforesaid primary absolution immediately confirmed.’

In the past transalpine journeys started from Avignon, it was the entrance to Italy. The geographies say: ‘The Rhône is the King’s, but the town of Avignon is watered by a branch of the River Sorgue, which is the Pope’s.’ Is the Pope so certain of retaining ownership of the Tiber for long? At Avignon you can visit the Celestine monastery. Good King René, who lowered the taxes when the tramontane blew, painted a skeleton in one of the rooms of the Celestin monastery: it was that of a woman of great beauty whom he had loved.

‘Avignon - Château de Papes’

Histoire des Villes de France, Vol 04 - Aristide Guilbert (p92, 1844)

The British Library

BkXIV:Chap2:Sec2

In the Church of the Cordeliers, is the tomb of Madonna Laura: Francis I ordered it opened and saluted the immortalised ashes. The victor of Marignan left behind this epitaph for the new tomb which he had erected.

‘En petit lieus compris vous pouvez voir

Ce qui comprend beaucoup par renommée:

...................

Ô gentille âme, estant tant estimée,

Qui te pourra louer qu’en se taisant?

Car la parole est toujours reprimee,

Quant le sujet surmonte le disant.’

‘Contained in brief space you may see

Whom many know of by her fame:

..............

O noble soul, being so proclaimed

Who could but by silence praise her?

Since speech must ever be restrained

When the subject outdoes the speaker.’

When all is said and done, the Father of Letters, the friend of Benvenuto Cellini, Leonardo da Vinci, and Le Primatice, the king to whom we owe the Diana, sister of the Apollo Belvedere, and Raphael’s Holy Family; the singer of Laura, the admirer of Petrarch, has received imperishable life from the fine arts, in gratitude.

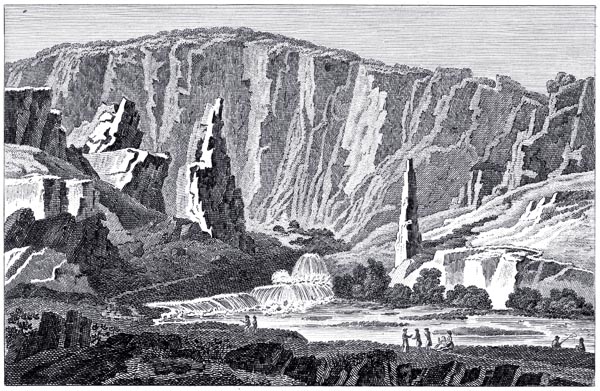

I went to Vaucluse, to gather, at the edge of the spring, the perfumed heathers and the first olive from a young olive tree:

‘Chiara fontana in quel medesmo bosco

sorgea d’un sasso, et acque fresche et dolci

spargea, soavemente mormorando;

al bel seggio, riposto, ombroso et fosco,

né pastori appressavan né bifolci,

ma ninphe et muse a quel tenor cantando:’

‘In that same grove a crystal fountain sprang from beneath a stone, and sprinkled sweet fresh water, murmuring gently: no shepherd or flocks ever approached that lovely place, secret, shadowy and dark, but nymphs and Muses singing to its tones:’

Petrarch has told how he found this valley: ‘I was enquiring’, he says, ‘about a secluded spot to which I could retire as to a harbour, when I discovered a little enclosed valley, Vaucluse, quite solitary, where the source of the Sorgue rose, queen of all springs: I established myself there. It is there where I composed my poetry in the native tongue; verse in which I described the sorrows of my youth.’

‘The Source of the Vaucluse’

Hendrik Roosing, 1786 - 1826

The Rijksmuseum

It was in Vaucluse too that he heard, as one could still hear while I was passing by, the sound of weapons echoing through Italy; he cried:

‘Itala mia.

..................

O diluvio raccolto

di che deserti strani

per inondar i nostri dolci campi!

....................................................

Non è questo 'l terren ch'i' toccai pria?

Non è questo il mio nido

ove nudrito fui sí dolcemente?

Non è questa la patria in ch'io mi fido,

madre benigna et pia,

che copre l'un et l'altro mio parente?’

‘My Italy!...O waters gathered from desert lands to inundate our sweet fields! Is this not the earth that I first touched? Is this not my nest where I was so sweetly nourished? Is this not the land I trust, benign and gentle mother that covers both my parents?’

Later, Laura’s lover urged Urban V to transfer the Papacy to Rome: ‘What will you say to Saint Peter,’ he demanded eloquently, ‘when he asks you “What is happening in Rome? What is the state of my Church, my tomb, my people? You say nothing? Where are you from? You have lived on the Banks of the Rhône? You were born there, you say: and I was I not born in Galilee?”’

Fertile age, young, sensitive, admiration for which stirs the heart; age which obeyed a great poet’s lyre, as if it were a legislator’s law! It is to Petrarch we owe the return of the sovereign Pontiff to the Vatican; it is his voice which gave birth to Raphael and raised Michelangelo’s dome from the earth.

On my return to Avignon, I visited the Papal Palace, and they showed me La Tour de la Glacière: the Revolution concerned itself with famous places; the memories of the past are forced to traverse, and grow green again on, human remains. Alas! The groans of victims die soon after them; they scarcely produce an echo that survives a moment, when once the voice that breathes them is extinguished. But though the cries of pain have vanished from the banks of the Rhone, one still hears in the distance the sound of Petrarch’s lute; a solitary canzone, escaping from the tomb, continues to grace Vaucluse with an immortal sadness and the sorrows of a past love.

Alain Chartier was carried from Bayeux to be buried in the Church of Saint-Antoine at Avignon. He wrote La Belle Dame sans mercy, and Margeret of Scotland’s kiss inspired it.

BkXIV:Chap2:Sec3

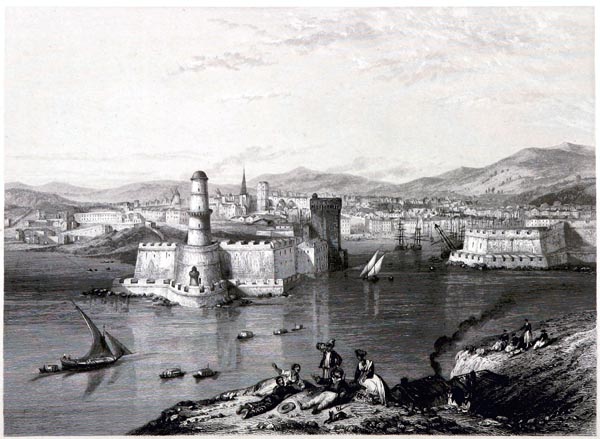

From Avignon I went on to Marseilles. What more could a town desire to which Cicero, whose oratorical manner has been imitated by Bossuet, addressed these words,: ‘I will never forget you, Marseilles, whose virtue is of so eminent a degree that most nations must yield to you, and to which even Greece should not compare itself.’ (Pro L Flacco). Tacitus, in his life of Agricola, also praises Marseille, which mingles Greek urbanity with the industry of the Roman provinces. Daughter of Hellenism, civiliser of Gaul, celebrated by Cicero, taken by Caesar, are you not wedded to glory? I hastened to climb up to Notre-Dame de la Garde, to gaze at the sea that borders the smiling coastlines of all famous nations of antiquity and their ruins. That sea, without tides, is the source of mythology, as the ocean, which ebbs and flows twice a day, is the abyss to which Jehovah said: ‘You shall go no further.’

‘Marseilles’

Histoire des Villes de France, Vol 01 - Aristide Guilbert (p666, 1844)

The British Library

This very year, 1838, I climbed again to that summit; I looked again at that sea which is now so well-known to me, on whose far side the victorious cross and tomb were raised. The mistral blew; I entered the fort built by Francis I, guarded by a single veteran of the Army of Egypt, and where a conscript destined for Algeria stood lost among the gloomy vaults. Silence reigned in the restored chapel, while the wind moaned outside. The Breton sailors’ hymn to Notre-Dame de Bon-Secours came to mind: you know when and where I have already quoted that lament of my early days beside the Ocean:

‘I place my confidence,

Virgin, in your aid, etc.

What events it had taken to bring me back to the feet of the Star of the Seas, to whom I had been dedicated in childhood! When I contemplated the ex-votos, those paintings of shipwrecks hanging from the walls around me, I thought I was reading the story of my days. Virgil depicted a Trojan beneath the porticos of Carthage, amazed at the sight of a picture representing the burning of Troy, and the genius of the author of Hamlet benefited from the soul of the author who sang of Dido.

At the foot of the cliff, once covered by the forest Lucan sings of, I no longer recognised Marseilles: I could no longer lose my way among those straight streets, built long and wide. The port was choked with vessels; twenty six years before, I had trouble finding a single nave, captained by a descendant of Pytheas, to carry me to Cyprus like Joinville: unlike men, time rejuvenates cities. I preferred my old Marseilles, with its memories of Bérenger, the Duc d’Anjou, King René, De Guise and D’Épernon, with its statues of Louis XIV and Belzunce’s virtues; the wrinkles on its brow pleased me. Perhaps in regretting the years now lost to it, I was doing no more than bemoaning those I had known myself. Marseilles welcomed me graciously, it is true: but that rival of Athens is now too young for me.

If Alfieri’s memoirshad been published in 1802 I would not have left Marseilles without visiting the rock from which the poet bathed. This crude man did at least once achieve grace of thought and expression:

‘After the sights,’ he says, ‘one of my amusements at Marseilles was to bathe in the sea almost every evening; I found a very pleasant little spot on a spit of land set to the right of the port, where, seated on the sand, my back against a rock, preventing anyone seeing me from the coast side, I had nothing before me but sea and sky. Between those two immensities, adorned by a setting sun, I spent, in dreaming, delightful hours; and there, I would have become a poet, if I had known how to write it in some language or other.’

BkXIV:Chap2:Sec4

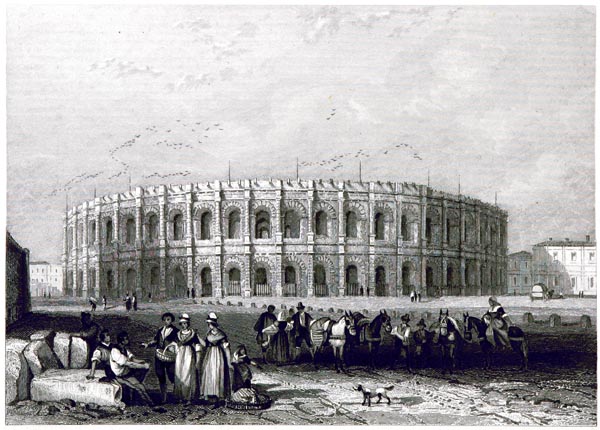

I returned through Languedoc and Gascony. At Nîmes, the Amphitheatre and the Maison-Carré were not yet cleared; this year 1838, I have seen them during the excavations.

‘Arènes de Nîmes’

Histoire des Villes de France, Vol 06 - Aristide Guilbert (p666, 1844)

The British Library

I also went to find Jean Reboul. I somewhat question the idea of these worker-poets, who are customarily neither poets, nor workers: redress therefore to Monsieur Reboul. I found him in his bakery; I addressed him without knowing to whom I spoke, not distinguishing him from his companions of Ceres. He took my name and told me he would go and see if the person I had asked for was at home. He quickly returned and made himself known: he led me into his store-room; we navigated a labyrinth of flour sacks, and climbed up a kind of ladder into a tiny room, as if into the high loft of a windmill. There we sat and talked. I was as happy as if I were in my London attic, and happier than in my chair at the Ministry in Paris. Monsieur Reboul had taken a manuscript from a chest of drawers, and read me some lively verses of a poem he had composed on The Last Day. I congratulated him on his religion and his talent. I remember these excellent lines to an Exile:

‘Something of grandeur in this world is stirring;

Your soul shall respond to it, O our young king;

Ah! Not without purpose, has Heaven displayed,

Calming our grief, through the dying, your fate;

That, from his watching sons, in the after days,

Universally seen, a proud nation might raise

You, high in its arms, on the edge of a grave!’

I had to leave my host, but not without wishing the poet joy of the gardens of Horace. I would rather have seen him dreaming beside the Tiber, than collecting corn milled by a wheel driven by its flow. It is true that Sophocles may have been a blacksmith in Athens, and Plautus, in Rome, presaged Reboul at Nîmes.

Between Nimes and Montpellier, I passed Aigues-Mortes on my left, which I have visited again in 1838. The town is still completely intact with walls and towers: it resembles a high-sided vessel grounded among the sands from which Saint-Louis departed, time and the tides. The saintly king gave the town of Aigues-Mortes its statutes and customs: ‘He wished the prison to be such that it served not to destroy people but to protect them; that no legal investigation should be made of insulting speech; that even adulterers should only be sought out in certain cases, and that the violator of a virgin, volente vel nolente (willing or unwilling), should lose neither life nor any member, sed alio modo puniatur (but should be punished in some other way).

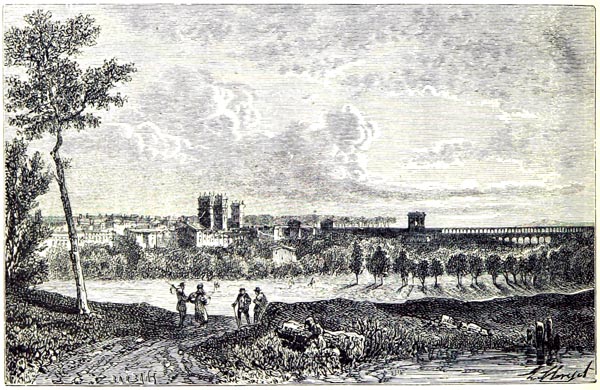

At Montpellier, I saw the sea again, to which I would willingly have written, like the Christian king to the Swiss Confederation: ‘My faithful ally and great friend.’ Scaliger would have liked to make Montpellier the nest of his old age. It received its name from two sacred virgins, Mons puellarum (the hill of the young girls): and from that, the beauty of its women. Montpellier in falling to Cardinal Richelieu, witnessed the death of the aristocratic constitution of France.

‘Montpellier’

La France Pittoresque. Ouvrage Illustré - Jules Gourdault (p400, 1893)

The British Library

From Montpellier to Narbonne, I experienced, on the road, a flood of daydreams, a return to my natural disposition. I would have forgotten the attack, like other illnesses of the imagination, if I had not made a note of the critical day on a slip of paper, the only note I have discovered from that time to aid my memory. On this occasion it was an arid waste covered with foxgloves that made me forget the world: my gaze glided over that sea of purple stems, and was only arrested in the distance by the bluish mountains of Cantal. In nature, apart from the sky, ocean and sun, it is not the largest objects that inspire me; they only give me a sensation of grandeur, which hurls my littleness, distraught and un-consoled, at the feet of God. But a flower I have picked, a current of water slipping through the bull-rushes, a bird which goes flying and perching before me, entangles me in all sorts of dreams. Is it not better to be moved without knowing why, than to search out dull pursuits in life, chilled by their repetition and their number? Everything is worn out these days, even tragedy.

‘Narbonne - Hôtel de Ville’

La France Pittoresque. Ouvrage Illustré - Jules Gourdault (p396, 1893)

The British Library

At Narbonne, I encountered the Canal des Deux-mers. Corneille, singing the praises of this work, added his greatness to that of Louis XIV:

‘Garonne and the Aude, in their deep caves,

Sighed, through the years, to unite their waves,

That from their happy affection might flow

Treasures of dawn, to meet evening’s glow.

But to such fond wishes, to passions so pure

Nature, which bows to eternal law,

Proudly laid down invincible obstacles

Imprisoning frightful cliffs and pinnacles.

France! Your great King spoke, rocks split in two,

Earth opened its breast, the high hills fell too.

All yielded........................................................’

BkXIV:Chap2:Sec5

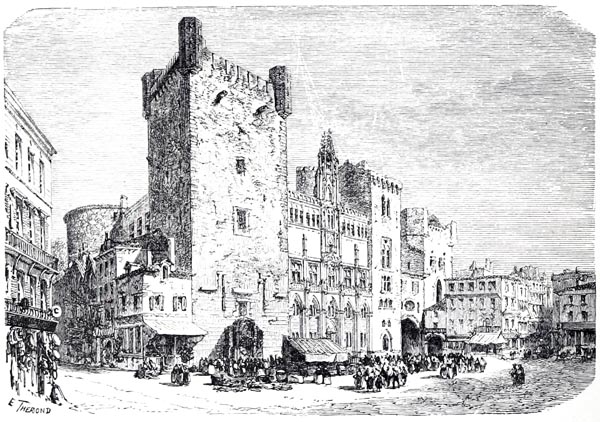

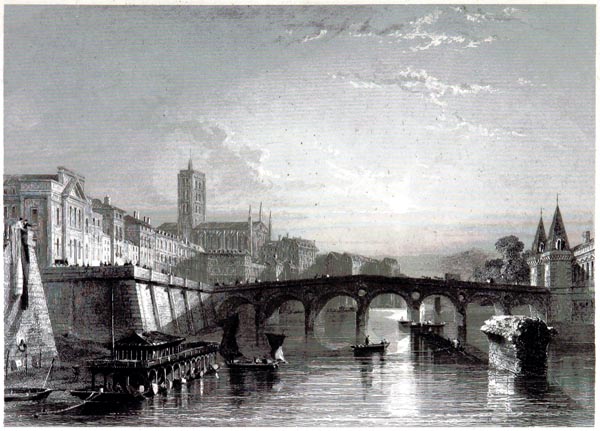

At Toulouse, I saw the line of the Pyrenees from the bridge over the Garonne; I was obliged to cross it four years later; horizons succeed each other like our days. They proposed to show me, in a cave, the desiccated corpse of La Belle Paule: happy those who believe without having seen! Montmorency was decapitated here in the courtyard of the Hôtel de Ville: was that severed head of such importance then, since we still speak of it after so many other heads have fallen? I do not know if there is a witness’s deposition, anywhere in the history of criminal proceedings, which better testifies to a man’s identity: ‘The smoke and flames in which he was enveloped,’ says Guitaut, ‘prevented me from recognising him at first; but seeing a man, who after breaking through six of our ranks, still managed to kill some soldiers of the seventh, I judged that it could only be Monsieur de Montmorenci; I became certain when I saw him thrown to earth beneath his dead mount.’

‘Toulouse’

Histoire des Villes de France, Vol 06 - Aristide Guilbert (p387, 1844)

The British Library

I was struck by the architecture of the abandoned church of Saint-Sernin. This church is bound up with the history of the Albigensians, which the poem, so well translated by Monsieur Fauriel, has revived:

‘The valiant young Count, the light and the heir of his father, the cross and the sword, entered together through one of the doors. Not one young girl remained in her room or upstairs; the inhabitants of the town, young and old, all regarded the Count as the flower of the rose.’

It is from the era of Simon de Montfort that the withering of the language of Oc dates: ‘Simon, being lord of so much territory, divided it among the nobles, as much to the French as others, atque loci leges dedimus (and we gave laws to the lands),’ said the signatories, eight archbishops and bishops.

I would have liked to have had the time in Toulouse to enquire about one of the men I most admire, Cujas, writing, lying face down, his books spread around him. I wonder if they have retained the memory there of Suzanne, his daughter, twice married. Constancy gave Suzanne little pleasure, she paid scant attention to it; but she nurtured one of her husbands on the infidelities which killed the other. Cujas was supported by Francis I’s daughter, Pibrac by the daughter of Henri II, two Marguerites, of Valois blood, the pure blood of the Muses. Pibrac is celebrated for his translations of Persian quatrains. (I may have been staying in his father the president’s house.). ‘This fine Monsieur de Pibrac,’ says Montaigne, ‘had a spirit so gentle, such sound opinions, such mild manners; his soul was so untainted by our corruption and our passions!’ And yet he had praised the Saint Bartholomew massacre!

I rushed past without being able to stop; fate sent me back in 1838 in order to admire Raimond de Saint-Gilles city in detail, and to speak of new acquaintances I had made; Monsieur de Lavergne, a man of talent, wit, and reason; Mademoiselle Honorine Gasc, a future Malibran. The latter, in my new role of servant to Clémence Isaure, reminded me of those lines that Chapelle and Bachaumont wrote on the island of Ambijoux, near Toulouse:

‘Ah! How happy, without strife,

In this sweet place, deserving envy,

If, forever loved by Sylvie,

With her, one might spend one’s life!

Enamoured for eternity!’

Let Mademoiselle Honorine be wary of her lovely voice! Talent is made of Toulouse gold: it brings bad luck.

Bordeaux was barely rid of its scaffolds and its cowardly Girondins. All the towns I saw had the air of beautiful women recovering from a violent illness who had scarce begun to breathe again. At Bordeaux, Louis XIV had once pulled down the Temple of the Tutelary Goddess, in order to build the Château-Trompette: Spon and the friends of antiquity mourned:

‘Why demolish these, the gods’ own pillars,

A tutelary monument, work of the Caesars?’

The few remains of the Amphitheatre are barely visible. If one granted an expression of regret to everything which falls, it would require too many tears.

I embarked for Blaye. I saw the chateau which was then unknown, to which, in 1833, I addressed these words: ‘Captive of Blaye! I regret my powerlessness regarding your current fate!’ I headed for Rochefort, and reached Nantes via the Vendée.

The countryside revealed, like an old warrior, scars and mutilations attributable to its courage. Remains bleached by time, and ruins blackened by flames, met one’s gaze. When the Vendéans were about to attack their enemy, they knelt to receive the priest’s blessing: the prayer pronounced over their weapons was not deemed useless, since a Vendéan who raised his sword to heaven, demanded victory and not life.

The coach, I found myself interred in, was full of travellers who told stories of the violation and murder with which they had glorified their lives during those wars in the Vendée. My heart quickened, when after crossing the Loire at Nantes, I entered Brittany. I passed the walls of the College at Rennes which saw the last days of my childhood. I could only stay with my wife and sisters for twenty-four hours, before regaining Paris.

Book XIV: Chapter 3: The years 1802 and 1803 – Monsieur de Laharpe: his death

Paris, 1838

BkXIV:Chap3:Sec1

I arrived in time to witness the death of a man who belonged among those superior names of the second degree in the eighteenth century, and who, forming a solid second rank within society, give that society fullness and consistency.

I had known Monsieur Laharpe in 1789: like Flins, he was seized by a strong passion for my sister, Madame la Comtesse de Farcy. He appeared with three large volumes of his works under his short arms, utterly amazed that his glory had not triumphed over the most rebellious hearts. The words lofty, the expression animated, he thundered against abuses, making do with an omelette at the houses of Ministers where he found the dinner unsatisfactory, eating with his fingers, trailing his cuffs through the dishes, speaking coarse philosophy to the grandest lords who enjoyed his effronteries; but, in sum, an honest spirit, enlightened, impartial in the midst of his passion, capable of appreciating talent, of admiring it, of weeping at a lovely line or a fine action, and possessing one of those true natures capable of repentance. He did not fail in death: I saw him die a brave Christian: his interests were broadened by religion, being a man without pride except in countering impiety, and without hatred except in countering revolutionary language.

By the time I returned from the Emigration, religion had led Monsieur de Laharpe to a favourable view of my works: the illness from which he suffered did not prevent him from working; he recited to me several passages from a poem he had composed on the Revolution; it contained powerful lines against the crimes of the age and against the honest men who had tolerated them:

‘Yet if they dared all, you have permitted all:

The viler the master is, the worse the slave.’

Forgetting that he was unwell, wearing a white nightcap, and dressed in a wadded woollen jacket, he would declaim at the top of his voice; then letting his notebook fall, he would say in a barely audible voice: ‘I can’t go on: I feel a claw like fire in my side.’ But if, by misfortune, a servant happened to appear, he would resume his Stentorian tone and bellow: ‘Off with you! Off with you! And close the door!’ I said to him one day: ‘You will live, to the benefit of religion.’ – ‘Ah, yes!’ he replied, ‘That would be pleasant of God; but he does not wish it, and I will die one of these days.’ Falling back into his armchair and pulling his cap over his ears, he atoned for his pride with resignation and humility.

At a dinner at Migneret’s house, I heard him speak of himself with the greatest modesty, declaring that he had achieved nothing of the highest order, but that he believed art and language had not degenerated in his hands.

Monsieur de Laharpe left this world on the 11th of February 1803: the author of Les Saisons died two days before him amidst all the consolations of philosophy, as Monsieur Laharpe did amidst all the consolations of religion; the former visited by men, the latter visited by God.

Monsieur de Laharpe was buried on the 12th of February 1803, in the Cemetery of the Vaugirard Gate. The coffin having been set down beside the grave, Monsieur de Fontanes gave a speech, standing on the little mound of earth which would soon fill it. The scene was gloomy: swirls of snow fell from the sky and whitened the funeral drape which the wind lifted, to allow those last words of friendship to reach the ears of the dead. The cemetery has been destroyed and Monsieur de Laharpe exhumed: hardly anything remains of his scant ashes. Re-married under the Directory, Monsieur de Laharpe had been unfortunate in his lovely wife; she had developed a dislike for the sight of him, and would never accord him any rights.

For the rest, Monsieur de Laharpe had, like everything else, been diminished by the Revolution which always grew in scope: the famous hastened to withdraw before the representative of that Revolution, as danger lost its potency before him.

Book XIV: Chapter 4: The years 1802 and 1803 – Interview with Napoleon

Paris, 1838

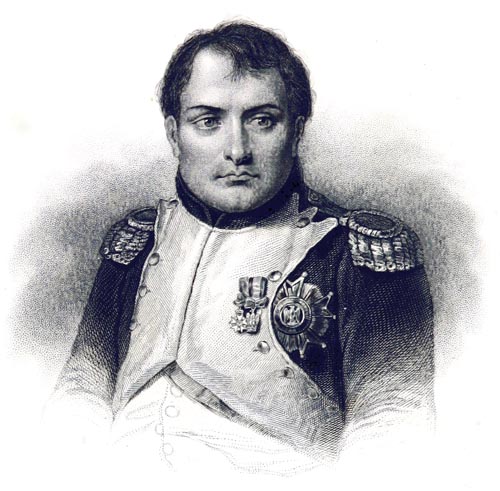

BkXIV:Chap4:Sec1

While we were occupied with everyday life and death, the world’s great advance was accomplished; the Man of his time took up his place of honour at the head of the human race. In the midst of immense changes, the precursors of a universal movement, I had disembarked at Calais in order to join in the general activity, to the degree allotted to every soldier. I arrived, in the first year of the century, at Bonaparte’s camp where he beat out the drum-roll of destiny: he soon became First Consul for life.

‘Napoléon’

Histoire de France, pendant la République, le Consulat, l'Empire, et la Restauration Jusqu'à la Révolution de 1830 - Jacques-Baron Marquet de Montbreton de Norvins (p566, 1850)

The British Library

After the adoption of the Concordat by the Legislative Body in 1802, Lucien, the Interior Minister, gave a reception for his brother; I was invited to attend, as one who had rallied the forces of Christianity and had led them back to the charge. I was in the gallery when Napoleon entered: he struck me agreeably; I had not seen him before except at a distance. His smile was soft and pleasant; his eyes were admirable, especially in the manner in which they were set beneath his forehead and framed by his eyebrows. There was no charlatanism in his gaze as yet, nothing theatrical or affected. Le Génie du Christianisme, which was making a considerable stir at that time, had moved Napoleon. A prodigious imagination animated that cold-blooded politician: he would not have been what he was if the Muse had not been present in him; reason carried out a poet’s ideas. All the men who lead great lives possess a dual nature, since they must be capable of inspiration and action: one conceives the project, the other executes it.

Bonaparte saw me and recognised me, I have no idea how. When he made his way towards me, no one knew whom he was seeking; the ranks opened successively; everyone was hoping that the Consul would stop in front of them; he had the look of a man experiencing some impatience with those misapprehensions. I sank back behind my neighbours; Bonaparte suddenly raised his voice and said: ‘Monsieur de Chateaubriand!’ I was left standing alone there, in front, since the crowd stepped back and then quickly reformed a circle around the speakers. Bonaparte addressed me simply: without complimenting me, without idle questions, without preamble, he spoke to me immediately about Egypt and the Arabs, as if I had always been in his confidence, and as if we were merely continuing a conversation we had already begun. ‘I was always struck,’ he said, ‘when I saw the sheikhs fall to their knees in the midst of the desert, turn towards the east and touch the sand with their foreheads. What was that unknown thing they were worshipping in the east?’

Bonaparte interrupted himself, and passed on to another idea without transition: ‘Christianity? Haven’t the ideologists tried to make an astronomical system out of it? If that should be the case, do they think to persuade me that Christianity is therefore trivial? If Christianity is an allegory of the movement of spheres, the geometry of stars, the free thinkers have done well, since despite themselves they have still left sufficient grandeur to l’infâme.’

Bonaparte suddenly moved away. Like Job, in my darkness, ‘a spirit passed before me; the hair of my flesh stood up; it stood still: but I could not discern the form thereof: an image was before mine eyes, there was silence, and I heard a voice.’

My days have been only a series of visions; Hell and Heaven have continually opened beneath my feet and above my head, without granting me the time to explore their darkness and light. On the shore of two worlds, and on only one occasion in each case, I have encountered the great man of the last century and the great man of the new, Washington and Napoleon. I spoke for a moment with each; both sent me back to my solitude, the first with a kindly wish, the second through a crime.

I noticed that while circling the throng, Bonaparte glanced at me in a more profound manner than he had gazed while speaking to me. I followed him also with my eyes:

‘Chi e quell grande, che non par che curi

L’incendio?’

‘Who is that great spirit, who seems indifferent to the fire?’ (Dante).

Book XIV: Chapter 5: The year 1803 – I am named as First Secretary to the Embassy in Rome

Paris, 1837

BkXIV:Chap5:Sec1

Following this interview, Bonaparte thought of me for Rome: he had judged at a glance where and how I could be of use. It mattered little to him that I had not been immersed in public affairs, that I knew not the first thing about diplomatic practice; he believed that such minds as mine always have an understanding, and can do without an apprenticeship. He was a great discoverer of men; but he wished them to possess talent only for his employment, even then on condition that it was little talked of: jealous of all fame, he regarded it as a usurpation of what was due to himself: there was to be no-one but Napoleon in the universe.

Fontanes and Madame Bacciochi told me of the satisfaction the Consul had taken in my conversation: I had not opened my mouth; that was as much as to say that Bonaparte was content with himself. They urged me to profit from my good fortune. The idea of accepting an appointment had never occurred to me; I firmly refused. Then, they asked an authority whom it was difficult to resist if he would speak to me.

The Abbé Émery, the superior of the Seminary of Saint-Sulpice, came to entreat me, in the name of the clergy, to accept for the good of religion the position of First Secretary to the Embassy, Bonaparte intending to appoint his own uncle, Cardinal Fesch as Ambassador. He gave me to understand that the Cardinal’s intellect was not exactly remarkable, and I would soon find myself the master of the Embassy’s affairs. A singular chance had established a link between Abbe Émery and myself: I had travelled to the United States with Abbé Nagot and his seminarists, as you know. That memory of my obscurity, my youth, my life as a voyager, reflecting on my public life, took hold of my feelings and imagination. Abbé Émery, well-regarded by Napoleon, was made lean by nature, religion, and the Revolution; yet this threefold early experience simply allowed him to profit from his true merit; ambitious only to do good works, he restricted his actions to achieving the greatest benefit for his seminary. Circumspect in his words and actions, it would have been pointless to show violence to Abbé Émery, since he always placed his whole self at your service, while never yielding his will: his strength was in waiting for you, as if seated on his tomb.

He failed in his first approach to me; he returned to the attack, and patiently convinced me. I accepted the position which it was his mission to propose to me, without being the least bit convinced of my ability for the post to which I was nominated; I am worth nothing in a supporting role. I would probably still have declined it, if the thought of Madame de Beaumont had not occurred to put an end to my scruples. Madame de Montmorin’s daughter was dying; the Italian climate, it was claimed, would be beneficial to her; my going to Rome would persuade her to cross the Alps: I sacrificed myself in the hope of saving her. Madame de Chateaubriand prepared to join me; Monsieur Joubert talked of accompanying me, and Madame de Beaumont left for Mont Dore, so as to further her recovery by the banks of the Tiber.

Monsieur de Talleyrand held the Foreign Ministry; he forwarded me my nomination. I dined with him; thus it has lodged in my mind that he considered himself to be of the first moment. For the rest, his fine manners contrasted with those of the rogues who made up his entourage; his displays of cunning took on unimaginable importance: in the eyes of a ruthless wasp’s nest, his moral corruption appeared as genius, his slightness of wit profundity. The Revolution was too modest; it did not celebrate his superiority sufficiently: it is not the same thing to be above crime as to be beneath it.

I met the ecclesiastics attached to the Cardinal: I singled out the good-humoured Abbé de Bonnevie: once chaplain to the Army of Princes, he was involved in the retreat at Verdun; he had also been chief curate to the Bishop of Châlons, Monsieur de Clermont-Tonnerre, who left after us to claim a pension from the Holy See, in the person of Chiaramonte. Having completed my preparations, I set out: I was required to arrive in Rome before Napoleon’s uncle.

Book XIV: Chapter 6: The year 1803 – Journey from Paris to the Savoy Alps

Paris, 1838

BkXIV:Chap6:Sec1

At Lyons, I met my friend Monsieur Ballanche once more. I was a witness to the renewed celebration of Corpus-Christi; I considered I had played a part in those flowery wreaths, in that heavenly joy that I had recalled to earth.

I continued my journey; a cordial reception awaited me everywhere; my name was associated with the re-establishment of the altars. The greatest pleasure I have known is to have felt myself honoured in France and noted with serious interest abroad. It sometimes happened, as I was resting in a village inn, that I would see a father and mother enter with their son: they would tell me they had brought their child along to thank me. Was it self-esteem then which granted me the pleasure of which I speak? What did it matter to my vanity that unknown and honest people testified to their happiness on a public highway, in a place where no one could hear them? What moved me, at least I dare to think so, was my having done a little good, consoled the distressed, caused the rebirth in the depths of a mother’s heart of the hope of raising her son a Christian, that is to say an obedient son, respectful, attached to his parents. Would I have tasted that pure joy if I had written a book whose morals and religion raised groans?

The road from Lyons is fairly gloomy: from Tour-du-Pin to Pont-de-Beauvoisin, it is cool and wooded.

At Chambéry, where Bayard’s chivalrous soul displayed itself so admirably, a man was welcomed by a woman, and as payment for the hospitality he had received, he considered himself philosophically obliged to dishonour her. Such is the danger of literature; the desire for fame overcomes generosity of feeling: if Rousseau had never become a celebrated writer, he would have buried the frailties of the woman who had nurtured him among the valleys of Savoy; he would have been subject to the same faults as his friend; he would have helped her in old age, instead of contenting himself with giving her a snuffbox, and vanishing. Ah! Never may the voice of friendship betrayed be raised against our tomb!

Having passed Chambéry, the Isère’s channel appears. Everywhere in these valleys one meets with crosses at the roadsides, and madonnas among the pine woods. The little churches, surrounded by trees, provide a moving contrast with the high mountains. When winter storms blow down from those ice-crowned summits, the Savoyard takes shelter in his rural temple and prays.

The valleys one enters above Montmélian are bordered by hills of various shapes, sometimes half-naked, sometimes clothed with forest.

Aiguebelle seems close to the Alps; but turning the corner of some isolated rock, fallen across the road, you see fresh valleys along the course of the River Arc.

The hills stand high on both sides; their flanks become perpendicular; their sterile summits begin to reveal glaciers: torrents fall to swell the Arc which flows wildly. In the midst of the tumult of waters, you find a careless waterfall falling with infinite grace beneath a curtain of willows.

Passing Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne and arriving towards sunset at Saint-Michel, I failed to find a horse: obliged to halt, I took a walk beyond the village. The air over the mountain crests became translucent; their indentations were drawn with extraordinary clarity, while a deep shadow emerging from their feet climbed towards their summits. The nightingale’s voice sounded from below, the eagle’s cry from above; service-trees flowered in the valley, white snow on the mountain. A castle, the work of Carthaginians, according to popular tradition, was visible on an outcrop cut sheer from the cliff. There, one man’s hatred, more powerful than any obstacle, was enshrined in stone. The vengeance of a race which could only rise to greatness through slavery and the blood of the rest of the world, weighed on a free people.

I left at daybreak and arrived, towards two in the afternoon, at Lans-le-bourg, at the foot of Mont Cenis. Entering the village, I saw a peasant grasping an eaglet by its feet; a pitiless throng were striking at the young king, insulted in the weakness of his youth and fallen majesty; the father and mother of the noble orphan had been killed: they suggested I buy him; he died of the harsh treatment they had subjected him to before I could rescue him. I was reminded then of poor little Louis XVII; I think today of Henri V: how swiftly fall and misfortune come!

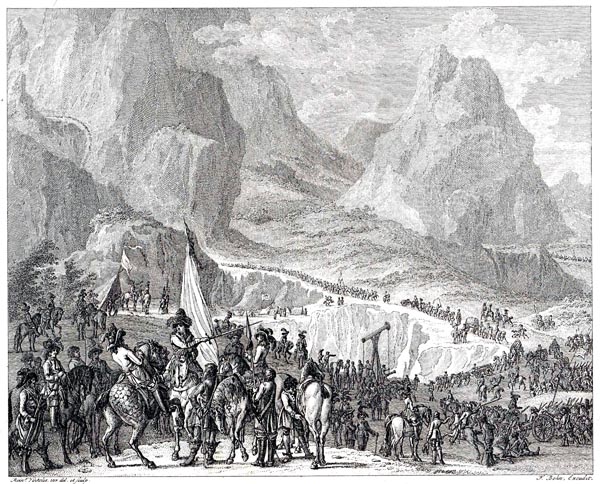

Here, one begins the ascent of Mont Cenis, leaving behind the little river Arc, which leads you to the foot of the mountain. On the far side of Mont Cenis, the Doria opens the gate of Italy to you. Rivers are not merely great flowing roads, as Pascal called them, they even trace out the route for men.

‘Eugene of Savoy with his Troops at Mont Cenis’

Reinier Vinkeles, François Bohn, 1751 - 1812

The Rijksmuseum

When I found myself on the crest of the Alps for the first time, a strange emotion gripped me; I was like that skylark which, at the same moment as myself, crossed the frozen plateau, and having sung its little song of the plain, fell among the snow, instead of descending to the fields. The stanzas these mountains inspired in me in 1822 evoke perfectly the feelings they stirred in me in 1803 at the same spot:

‘Alps, you have never suffered my fate!

You are unchanged by time;

Lightly, your foreheads carry those days

Weighing heavily on mine.

When, for that first time, filled with hope,

I crossed your battlements,

An immense future, the horizon, opened

To my sight and sense.

Italy beneath my feet, before me, the world!’

Did I really penetrate that world, then? Christopher Columbus had a vision which revealed to him the world of his daydreams, before he had discovered it; Vasco de Gama met the giant of the storms on the road: which of those two great men foreshadowed my future? What I would have liked before all else would have been a life made glorious by a brilliant end, but by its very nature obscure. Do you know whose the first remains were to rest in America? Those of Biorn the Scandinavian: he died in sight of Vinland, and was buried on a promontory by his companions. Who remembers that? Who knows of him whose sail preceded the Genoese captain’s ship to the New World? Biorn sleeps on the headland of an unknown cape, and his name has been transmitted to us for a thousand years only through the poetic sagas, in a language that no one now speaks.

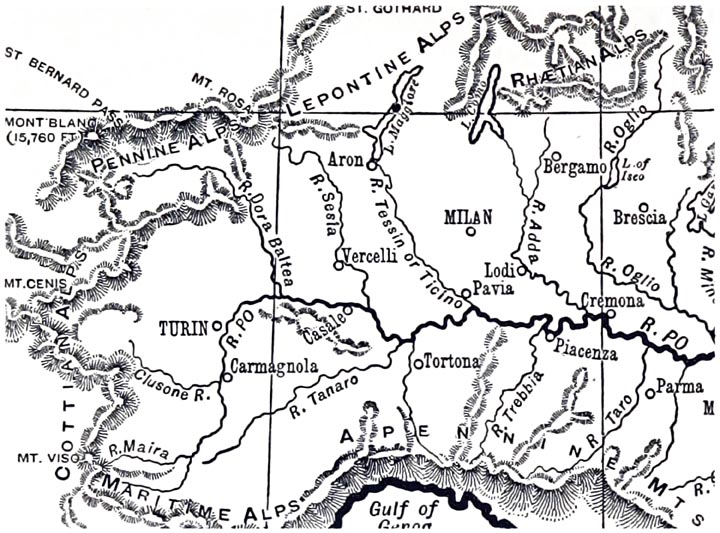

Book XIV: Chapter 7: From Mont Cenis to Rome – Milan and Rome

‘Basin of the Po’

Outlines Of Geography for the use of Lower and Middle Forms of Schools and of Candidates for the Army Preliminary Examinations - Annesley Ashburton Somerville (p122, 1895)

The British Library

BkXIV:Chap7:Sec1

I had begun my travels in the opposite direction to other voyagers: the ancient forests of America were revealed to me before the ancient cities of Europe. I arrived in the midst of the latter at the moment when they were dying and being reborn simultaneously in a fresh revolution. Milan was occupied by our troops; they had finished demolishing the castle, a witness to the wars of the Middle Ages.

The French Army had established itself, like a military colony, in the Lombardy plains. Guarded here and there by their comrades, acting as sentinels, these foreigners from Gaul, wearing policemen’s caps, carrying a sabre instead of a sickle strapped to their tight jackets, had the air of attentive and joyful reapers. They moved stones, rolled cannons, drove wagons; and erected sheds and huts made of branches. Horses leapt, pranced and reared among the throng like dogs fondled by their masters. Italian girls sold fruit from stalls in the marketplace of this military fairground: our soldiers made them presents of pipes and matches, saying to them, as their fore-fathers, barbarians of old, had said to their sweethearts: ‘I, Fotrad, son of Eupert, of the race of Franks, give to you, Helgine, my dear wife, in honour of your beauty (in honore pulchritudinis tuae), my house in the district of Pins.’

We were a singular enemy: they found us somewhat insolent at first, a little too cheerful, too restless, instead of our turning on our heels and walking away so they might regret us. Lively, witty, intelligent, French soldiers involve themselves in the occupations of the inhabitants with whom they lodge; they draw water from the well, as Moses did for the daughters of Midian, follow the shepherds, drive lambs to the sheep-dip, chop wood, lay fires, watch the cooking-pot, carry an infant in their arms or put it to bed in its cot. Their good humour and activity gives life to everything; it is customary to regard them as adjuncts to the family. The drum beats? The lodger runs for his musket, leaves his host’s daughters weeping at the door, and quits the cottage, which he thinks no more of until he reaches the Invalides.

On my journey to Milan, a great people awakened, and opened their eyes for a moment. Italy roused herself from slumber, and remembered her genius, like a divine dream: aiding our own renaissance, she brought grandeur of a transalpine nature to the meanness of our poverty, nurtured as she was, that Ausonia, with artistic masterpieces and the noble tales of a famous country. Austria came and spread her cloak of lead over the Italians; she forced them to step back into their coffin. Rome has returned to ruins, Venice to the sea. Venice is subsiding while embellishing the heaven of its last smile; she has settled charmingly into the waves, like a star which ought no longer to rise.

General Murat was in command of Milan. I had a letter for him from Madame Bacciochi. I spent the day with his aides-de-camp: they were not as poor as my comrades at Thionville. French chivalry had reappeared in the army; it was determined to prove itself forever of the age of Lautrec.

I dined at a grand official reception, on the 23rd of June, at Monsieur de Melzi’s, on the occasion of the baptism of General Murat’s child. Monsieur de Melzi had known my brother: the Vice-President of the Cisalpine Republic had excellent manners: his house resembled that of one who had always been a prince: he treated me politely but coldly; he found me exactly akin in disposition to himself.

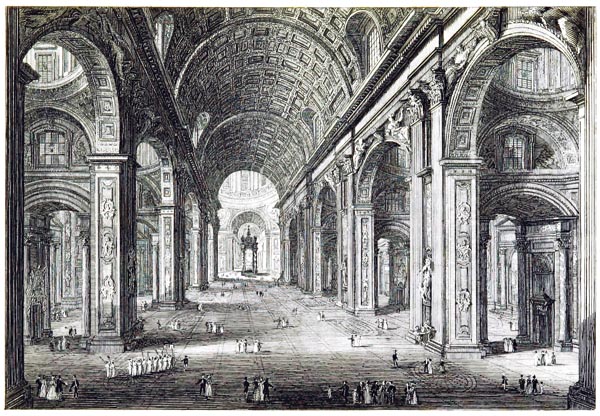

I reached my destination on the 27th of June in the evening, two days before the feast of Saint Peter: the Prince of the Apostles was waiting for me, as my patron saint has received me since in Jerusalem. I had followed the route from Florence, through Siena and Radicofani. I hastened to make my visit to Monsieur Cacault, whom Cardinal Fesch was succeeding, while I was replacing Monsieur Artaud.

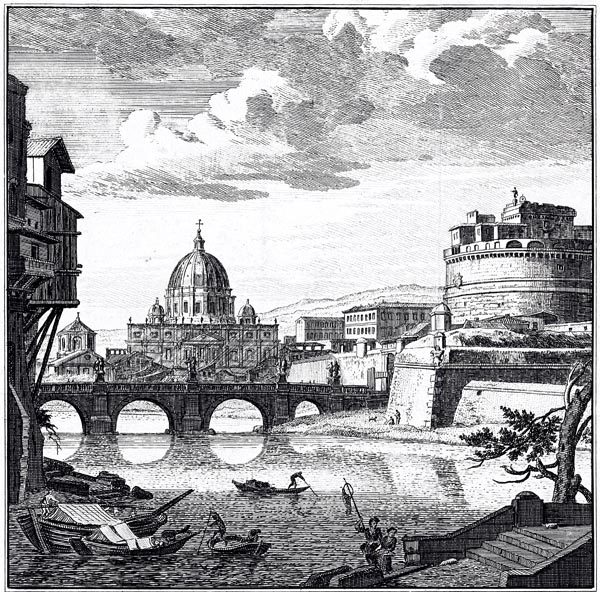

On the 28th of June, I rushed about all day: I took a first look at the Coliseum, the Pantheon, Trajan’s Column, and Castel Sant’Angelo. In the evening Monsieur Artaud took me to a ball in a house near Saint-Peter’s Square. One could see revolving fireworks on Michelangelo’s dome, between the whirling waltzes that skimmed past the open windows; the rockets sent up from Hadrian’s Mound blossomed over Saint Onofrio, and the tomb of Tasso: silence, abandonment, and night filled the Roman Campagna.

Next day, I attended the service at Saint Peter’s. Pius VII, pale, sad and religious, was a true Pontiff of tribulations. Two days afterwards, I was presented to His Holiness: he made me sit near him. A volume of Le Génie du Christianisme lay obligingly open on his desk. Cardinal Consalvi, flexible but firm, his resistance gentle and polite, was a living example of the ancient Roman politician, representing less the faith of the times and more the tolerance of the century.

‘Interior of St. Peter's at Rome’

Twenty Four Select Views in Italy - Thomas Leverton Donaldson (p65, 1833)

The British Library

Traversing the Vatican, I stopped to contemplate the stairs which one could climb on mule’s back, those ascending galleries echoing one another, adorned with masterpieces, along which the Popes once passed in all their pomp, those Loggias which so many immortal artists decorated, so many illustrious writers admired, Petrarch, Tasso, Ariosto, Montaigne, Milton, Montesquieu, and then the kings and queens, in power or out, and finally a race of pilgrims come from the four corners of the earth: all that now silent and without movement; a theatre in which the deserted terraces, exposed to solitude, are scarcely visited by a ray of sunlight.

I was advised to walk in the moonlight: from the heights of Trinita dei Monti, the distant edifices seemed like an artist’s sketches or like misted shores seen from the sea, on board ship. The moon, that globe that one takes for a complete world, slid its pale deserts over the deserts of Rome; it lit streets without people, enclosures, squares, gardens where no one stirred, monasteries where one no longer heard the voices of the coenobites, cloisters as dumb and unpopulated as the porticos of the Coliseum.

What was happening eighteen centuries ago, at this very hour in this very place? Who traversed the shadows of the obelisks here, after these shadows had ceased to fall over the sands of Egypt? Not only is ancient Italy no more, but the Italy of the Middle Ages has vanished also. Yet, the traces of those two Italy’s are still present in the Eternal City: if modern Rome displays its Saint-Peter’s and its masterpieces, ancient Rome counters with its Pantheon and its ruins; if the one is descended from the Capitol of the consuls, the other reveals the Vatican of the pontiffs. The Tiber separates the twin glories: founded on the same dust, pagan Rome is sinking further and further into its tombs, while Christian Rome returns little by little to its catacombs.

Book XIV: Chapter 8: Cardinal Fesch’s palace – My tasks

BkXIV:Chap8:Sec1

Cardinal Fesch had taken the Lancellotti Palace, quite close to the Tiber; I have since met, in 1828, Princess Lancellotti. I was allotted the highest story of the palace: on entering, such a host of fleas leapt about my legs that my white trousers turned quite black. The Abbé de Bonnevie and I cleaned up our residence as best we could. I thought I was back in my New Road kennel: that remembrance of my poverty did not displease me. One established in this diplomatic office, I began issuing passports and carrying out similar important functions. My hand-writing was an obstacle to my talent, and Cardinal Fesch shrugged his shoulders when he saw my signature. I had almost nothing else to do in my aerial chamber than look across the roofs at some laundry-women who made signs at me from a neighbouring house; an aspiring opera-singer, training his voice, drove me mad with his eternal scales; I was happy when a funeral passed to free me from my boredom! From the heights of my window I saw a young mother’s cortege: she was carried, her face uncovered, between two lines of white-robed pilgrims; her newborn baby, also dead and wreathed in flowers, was laid at her feet.

‘View of Rome Along the Tiber’

Hendrik Spilman, De Moucheron, 1742 - 1784

The Rijksmuseum

I made a great mistake: not having been forewarned, I thought I ought to visit various notable people; I went, informally, to pay my respects to the previous King of Sardinia, who had abdicated. A terrible fuss was made over this unusual action; all the diplomats buttoned up tight about it. ‘He is lost! He is lost!’ the carriers of the Pope’s train and the attachés murmured, with the pleasure people kindly take in a man’s misadventures, whoever he may be. There was not a diplomatic clod who did not think himself superior to me in all the elevation of his idiocy. There were high hopes that I was about to fall, though I was nobody and counted for nobody: no matter, somebody was falling, that was the pleasure of it all. In my simplicity, I had no doubt I had done wrong, and, as has happened since, I could not have cared a straw. Kings whom people thought I might have attached such great importance to, were only bringers of misfortune to my eyes. The tale of my appalling foolishness was sent from Rome to Paris: happily I had credit with Napoleon; what should have drowned me, saved me.

However, if at first glance, and after full consideration, becoming First Secretary of the Embassy under a Prince of the Church, and Napoleon’s uncle, seemed something of note, it was nevertheless only as if I had been clerk to a prefecture. Among the problems which arose, I could find things to occupy myself, but I was not initiated into any mysteries. I applied myself conscientiously to the business of the chancery; but what was the point of wasting my time in details within the grasp of any clerk?

After my long walks, and my visits to the shores of the Tiber, I only found, to occupy me on my return, the Cardinal’s parsimonious quibbles, the Bishop of Châlon’s gentlemanly boasting; and the incredible lies of the future Bishop of Maroc, the Abbé Guillon, who profiting from a similarity of name which sounded like his own to the ear, claimed, after miraculously escaping the massacre of the Carmelite Convent, to have granted absolution to Madame de Lamballe, while in La Force. He boasted of being the author of Robespierre’s address to the Supreme Being. I tried one day to get him to say he had been to Russia: he did not absolutely confess to it, but he did claim, modestly, to have spent several months in St Petersburg.

‘Madame de Lamballe, Engraved by E.Thomas from the Design by H. Rousseau’

Album du Centenaire, Grands Hommes et Grands Faits de la Révolution Française (1789-1804) - Augustin Challamel, Desire Lacroix (1889)

Wikimedia Commons

Monsieur de La Maisonfort, a man of hidden wit, had recourse to me, and soon Monsieur Bertin the Elder, proprietor of Les Débats, assisted me with his friendship in sad circumstances. Exiled to the island of Elba, by the man who returning from Elba in his turn drove him to Ghent, Monsieur Bertin had, in 1803, obtained from the republican Monsieur Briot whom I knew, permission to serve his exile in Italy. I visited the ruins of Rome with him and with him I watched Madame de Beaumont die; two things which have bound his life to mine. A critic of great taste, he, like his brother, gave me excellent advice regarding my work. He would have shown a true talent for words, if he had been called to the rostrum. A long-time legitimist, having undergone the experience of the Temple prison, and deportation to the Island of Elba, his principles, at heart, remained the same. I remained faithful to the friend of my difficult hours; all the political opinions in the world would not be worth the sacrifice of an hour of sincere friendship: suffice it that I am unmoved in my opinions, as I am attached to my memories.

Towards the middle of my stay in Rome, Princesse Borghèse arrived: I was charged with taking her some shoes from Paris. I was presented to her; she completed her toilette in front of me: the fresh pretty shoes which she slipped onto her feet were only required to touch this old earth for an instant.

In the end illness overtook me: it is a resource on which one can always rely.

Revised in December 1846

End of Book XIV