François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book IX: With the Army of the Princes 1792

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book IX: Chapter 1: I go to seek my mother at Saint-Malo – The progress of the Revolution – My marriage

- Book IX: Chapter 2: Paris – Old and new knowledge – Abbé Barthélemy – Saint-Ange – The Theatre

- Book IX: Chapter 3: The changing face of Paris – The Cordeliers Club – Marat

- Book IX: Chapter 4: Danton – Camille Desmoulins – Fabre d’Églantine

- Book IX: Chapter 5: Monsieur Malesherbes opinion concerning my emigration

- Book IX: Chapter 6: I gamble and lose - An adventure in a fiacre (four-wheeled cab) – Madame Roland – The Gate of L’Ermitage – The Second Federation of the 14th July – Preparations for Emigration

- Book IX: Chapter 7: I and my brother emigrate – Saint-Louis’ adventure – We cross the frontier

- Book IX: Chapter 8: Brussels – Dinner with the Baron de Breteuil - Rivarol – Departure for the Army of the Princes – The route – Encounter with the Prussian Army – I arrive at Trèves

- Book IX: Chapter 9: The Army of the Princes – The Roman amphitheatre - Atala – Henry IV and his shirts

- Book IX: Chapter 10: A Soldier’s life – The last appearance of the old army of France

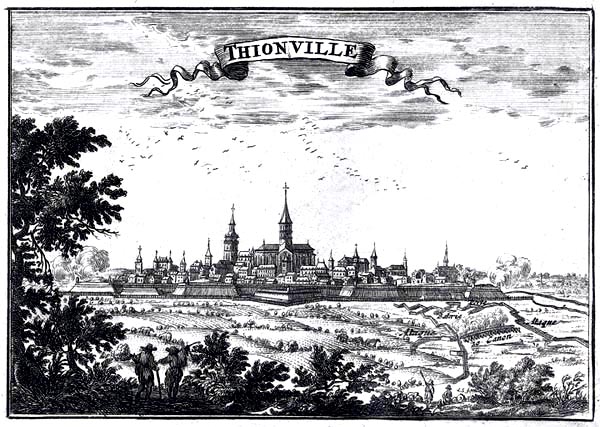

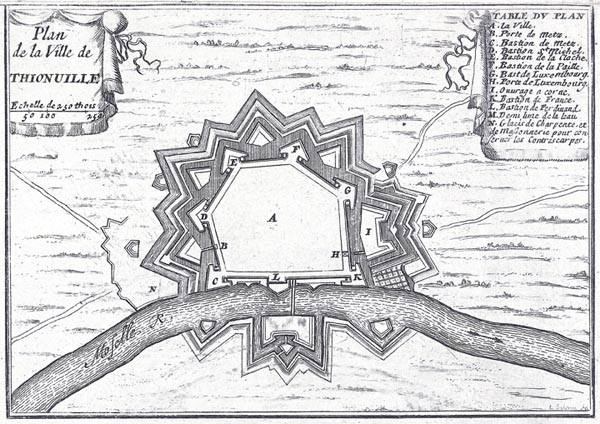

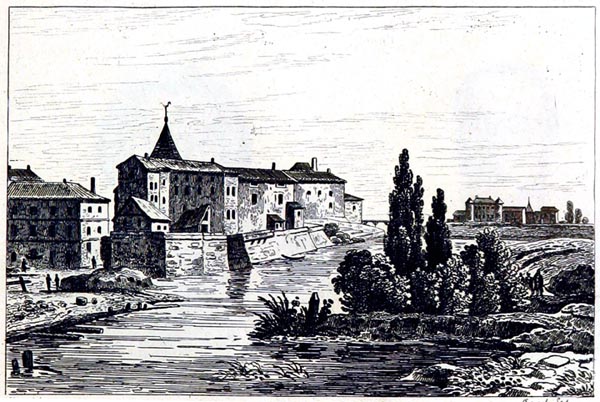

- Book IX: Chapter 11: The Siege of Thionville begins – The Chevalier de La Baronnais

- Book IX: Chapter 12: Continuation of the siege – Contrasts – Saints in the woods – the Battle of Bouvines – On patrol – An unexpected encounter – The effects of cannonballs and shells

- Book IX: Chapter 13: The Camp’s marketplace

- Book IX: Chapter 14: Night by the weapon stacks – Dutch dogs – Remembrance of the martyrs – Who my companions were in the forward positions – Eudore – Ulysses

- Book IX: Chapter 15: The passage of the Moselle – Combat – Libba the deaf-mute – The attack on Thionville

- Book IX: Chapter 16: The lifting of the siege – Entry into Verdun – The Prussian sickness (dysentery) – Retreat – Smallpox

Book IX: Chapter 1: I go to seek my mother at Saint-Malo – The progress of the Revolution – My marriage

London, April to September 1822. (Revised December 1846)

BkIX:Chap1:Sec1

I wrote to my brother, in Paris, giving the details of my crossing, explaining my motives for returning, and begging him to lend me the necessary sum to pay for my passage. My brother replied that he had forwarded my letter to our mother. Madame de Chateaubriand did not keep me waiting, she sent what was needed, to settle my debt and leave Le Havre. She told me Lucile was with her, as well as my uncle Bedée and his family. This news persuaded me to go to Saint-Malo, where I could consult my uncle on the question of my proposed emigration.

Revolutions, like rivers, grow greater along their course; I found the one I had left behind in France vastly increased and overflowing its banks; I had left it with Mirabeau under a Constituent Assembly, and found it again with Danton under a Legislative Assembly.

The Declaration of Pillnitz, of 27th August 1791, had become known in Paris. On the 14th December 1791, while I was in the midst of the storm at sea, the King announced that he had written to the princes of the German states (in particular to the Elector of Trèves) concerning German armament. Louis XVI’s brothers, the Prince de Condé, Monsieur de Calonne, the Vicomte de Mirabeau, and Monsieur de Laqueuille were almost immediately declared traitors. Following the 9th of November a previous decree had struck at the other émigrés: it was among the ranks of those already proscribed that I was hastening to establish myself; others might perhaps have backed away, but the greatest threat always makes me join the weakest side: to me the victor’s pride is insufferable.

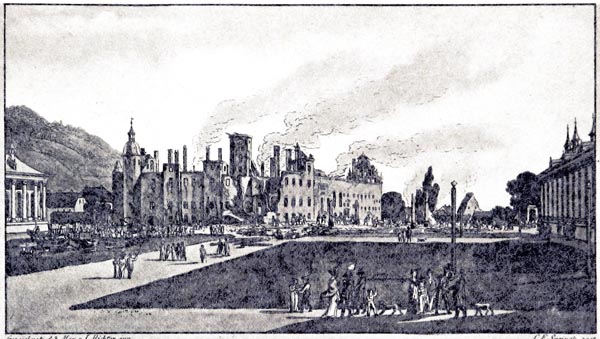

‘Schloss Pillnitz’

Geschichte von Pillnitz vom Jahre 1403 an - August von Minckwitz (p51, 1893)

The British Library

Travelling from Le Havre to Saint-Malo, I had the opportunity to witness the divisions and misfortunes of France: mansions were burnt out or abandoned; the owners, to whom symbolic distaffs had been sent, had left; their womenfolk were living as refugees in the towns. Hamlets and market towns groaned beneath the tyranny of clubs affiliated to the central Club des Cordeliers, later merged with the Jacobins. Its rival, the Société Monarchique or Société des Feuillants, no longer existed; the ignoble nickname of sans-culottes had become popular; the King was never spoken of except as Monsieur Veto or Monsieur Capet.

I was received tenderly by my mother and my family, though they deplored the inopportune timing of my return. My uncle, the Comte de Bedée, was preparing to cross to Jersey with his wife, son and daughters. There was a question of how to find the money for me to join the Princes. My voyage to America had made a hole in my fortune; my property as a younger son had been virtually annihilated by the suppression of feudal rights: the benefices which would have become due to me by virtue of my affiliation to the Order of Malta, had fallen into the hands of the Nation along with the rest of the Clergy’s wealth. This combination of circumstances led to the most serious event of my life: I was married off, in order to provide me with the means to go and get killed, for the sake of a cause I did not love.

BkIX:Chap1:Sec2

There lived in retirement at Saint-Malo, a certain Monsieur de Lavigne, a Knight of Saint-Louis, and former Commander of Lorient. The Comte d’Artois had stayed at his house in that town when he visited Brittany: delighted with his host, the Prince promised to grant him any favour he might ask in the future.

Monsieur de Lavigne had two sons. One of them married Mademoiselle de la Placelière. The two daughters born of this marriage lost both father and mother at an early age. The elder married the Comte du Plessix-Parscau, a Navy captain, the son and grandson of admirals, a commodore now himself, a Knight of the Order of Saint-Louis and commander of the Navy cadet corps at Brest. The younger, who lived with her grandfather, was seventeen when I arrived at Saint-Malo on my return from America. She was pale, delicate, slim and very pretty; she allowed her lovely blonde hair to hang down in natural curls, like a child. Her fortune was estimated at five or six hundred thousand francs.

My sisters took it into their heads to make me marry Mademoiselle de Lavigne, who had become very attached to Lucile. The affair was conducted without my knowing. I had scarcely seen Mademoiselle de Lavigne two or three times; I recognised her far off on Le Sillon, by her pink pelisse, white dress and her fair wind-blown hair, while I was on the beach, abandoning myself to the caresses of my old mistress, the sea. I felt I lacked every qualification for being a husband. All my illusions were alive, nothing in me was exhausted; the very energy of my being had redoubled on my travels. I was tormented by my Muse. Lucile loved Mademoiselle de Lavigne and saw this marriage as my means to a private fortune: ‘Go ahead, then!’ I said. In me, the public man is immovable, while the private man is at the mercy of whoever wishes to seize hold of him, and to avoid an hour’s trouble I would become a slave for a century.

The consent of Mademoiselle de Lavigne’s grandfather, her paternal uncle, and her principal relatives was easily obtained; there remained a maternal uncle, Monsieur de Vauvert, to be won over; a great democrat, he opposed his niece’s marrying an aristocrat like me, who was not one at all. We thought we could ignore him, but my pious mother insisted that the religious ceremony should be performed by a non-juring priest, and that could only be done in secret. Monsieur de Vauvert knew this, and let loose the law on us, on the grounds of rape, and violation of the code, asserting that the grandfather, Monsieur de Lavigne, had fallen into his second childhood. Mademoiselle de Lavigne became Madame de Chateaubriand, without my having had any communication with her, was taken away in the name of the law and placed in the convent of La Victoire at Saint-Malo, pending the decision of the courts.

In all of this there was no rape, no violation of the law, no risk, and no love; the marriage only possessed the worst aspect of a novel: the truth. The case was tried, and the tribunal judged the civil union valid. Since the parents on both sides were in agreement, Monsieur de Vauvert dropped the proceedings. The constitutional priest, generously bribed, withdrew his objection to the original marriage blessing, and Madame de Chateaubriand left the convent, where Lucile had immured herself with her.

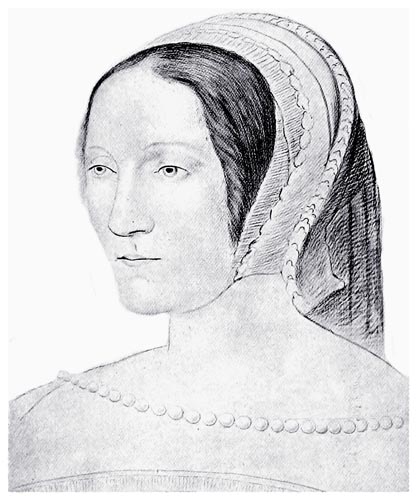

I had a new acquaintance to make, and it brought me all I might desire. I doubt whether a more acute mind than my wife’s has ever existed: she divines the birth of a thought or a word behind the brow or on the lips of the person she is talking to: it is impossible to deceive her. Of an original and cultivated spirit, writing in the most piquant style, telling a story to perfection, Madame de Chateaubriand admires me without having read two lines of my works; she would be afraid of meeting ideas other than her own, or discovering that there is too little enthusiasm for my merits. Though a passionate critic, she is well-informed and a good judge.

Madame de Chateaubriand’s faults, if she has any, flow from the superabundance of her virtues; my own very real faults stem from the sterility of mine. It is easy to possess resignation, patience, a general willingness to oblige, and an even temper, when one takes to nothing, is bored with everything, and when one replies to ill-luck as to good with a desperate and despairing: ‘What does it matter?’

Madame de Chateaubriand is better than me, though less easy to deal with. Have I been blameless towards her? Have I granted my companion all the attention she deserved and which should have been hers? Has she ever complained? What happiness has she tasted in return for an affection which has never wavered? She has shared my misfortune; she has been plunged into the prisons of the Terror, the persecutions of Empire, the difficulties of the Restoration, and has never known the joys of motherhood to counterbalance her sorrows. Deprived of children, whom a different marriage might have granted her, and which she would have loved to distraction; receiving none of the honours and affection of the mother of a family, which console a woman for the loss of her best years, she has advanced, barren and solitary, towards old age. Often separated from me, disinclined towards literature, the pride of bearing my name has been no compensation to her. Fearful and trembling for me alone, her anxieties, constantly renewed, rob her of sleep and the time to cure her ills: I am her chronic infirmity and the cause of her relapses. How could I compare the occasional impatience she has shown towards me with the worry I have caused her? How could I set my good qualities such as they are alongside her virtue which feeds the poor, which has created the Marie-Thérèse Infirmary, despite every obstacle? What are my labours compared with the good works of that Christian woman? When we both appear before God, it is I who will be condemned.

‘Madame de Chateaubriand’

The Pearl of Princesses: the Life of Marguerite d'Angoulême, Queen of Navarre - Hugh Noel Williams (p268, 1916)

Internet Archive Book Images

All in all, when I consider my imperfect nature in its entirety, is it certain that marriage has harmed my life? Without doubt I would have had more leisure and repose; I would have been more welcome in certain social groupings and among certain of the world’s grandeurs; but in politics, if Madame de Chateaubriand has annoyed me, she has never thwarted me, since in that field, as in affairs of honour, I judge only as I feel. Would I have produced a greater number of works if I had remained single, and would those works have been better? Have there not been circumstances, as we will see, where, marrying outside France, I would have stopped writing and renounced my country? If I had not married, might my weaknesses not have left me prey to some unworthy creature? Might I not have wasted and muddied my days like Lord Byron? Now that I am burdened with years, all my follies are past; only emptiness and regrets remain: an old widower without value, whether deceived or undeceived; an old bird repeating my hackneyed song for those who do not listen. Allowing my desires full rein would not have added a single string more to my lyre, a single tender tone more to my voice. My constrained feelings and the mystery of my thoughts have added perhaps to my powers of expression, have animated my works with inner fever, a hidden flame, which would have been dissipated by the free air of love. Restrained by an indissoluble tie, I have bought, at the cost of a little early bitterness, the sweetness that I taste today. I have only retained the incurable effects of the ills of my existence. I therefore owe a tender and eternal gratitude to my wife, whose attachment to me has been as touching as it has been profound and sincere. She has made my life more weighty, noble, and honourable, always inspiring respect in me, if not always the power to fulfil my duty to her.

Book IX: Chapter 2: Paris – Old and new knowledge – Abbé Barthélemy – Saint-Ange – The Theatre

London, April to September 1822.

BkIX:Chap2:Sec1

I was married at the end of March 1792, and on the 20th April, the Legislative Assembly declared war on Francis II of Germany, who had just succeeded his father Leopold; on the 10th of the same month, Benedict Labre had been beatified in Rome: there you have two worlds. The war precipitated the exit of the remaining nobility from France. On the one hand, persecution intensified; on the other, no Royalist was allowed to remain at home without being thought a coward: it was time for me to head for the camp I had come so far to seek. My uncle Bedée and his family embarked for Jersey, and I left for Paris with my wife and my sisters, Lucile and Julie.

We had taken an apartment, in the Faubourg Saint-Germain, in the cul-de-sac Férou, at the Petit Hôtel de Villette. I hastened to seek out my former friends. I visited again the men of letters whom I had known. Amongst the new faces, I found those of the wise Abbé Barthélemy and the poet Saint-Ange. The Abbé has fashioned his gynaeceums in Athens too much in the style of the salons of Chanteloup. The translator of Ovid was a man not lacking in talent; talent is a gift, a specific capability; it may be combined with the other mental faculties, or it may be separate. Saint-Ange provides the proof; he makes great efforts not to be foolish, but can’t prevent himself. A man whose pen I admired and continue to admire, Bernardin de Saint-Pierre, lacks spirit, and unfortunately his character was on a level with his spirit. How many descriptions are ruined in the Etudes de la nature through limited intelligence, and the lack of elevation of the writer’s soul!

Rulhière had died suddenly in 1791, before my departure for America. I have since seen his little house at Saint-Denis, with its fountain and pretty statue of Love, at the foot of which one reads these lines:

‘D’Egmont and Love visited this shore:

An image of her beauty,

Combing its hair, in the swift wave, I saw:

D’Egmont is gone; here remains Love only.’

When I left France, the Paris theatres were still echoing to Le Réveil d’Épiménide and to these couplets:

‘I love the warlike virtue

Of our brave defenders,

Yet I hate the fury, too,

Of bloodthirsty soldiers.

In Europe, let us be free

Formidable, as ever,

Yet, with generosity,

Defending France forever.’

On my return, there was no longer any question of Le Réveil d’Épiménide; and if the couplets had been sung it would have done the author a bad turn. Charles X had prevailed. The vogue the piece enjoyed was principally due to circumstance; the alarm bell, a people armed with knives, the hatred displayed for king and priests, offered a repetition in camera of the tragedy which was being played out in public. Talma, on his debut, continued his success.

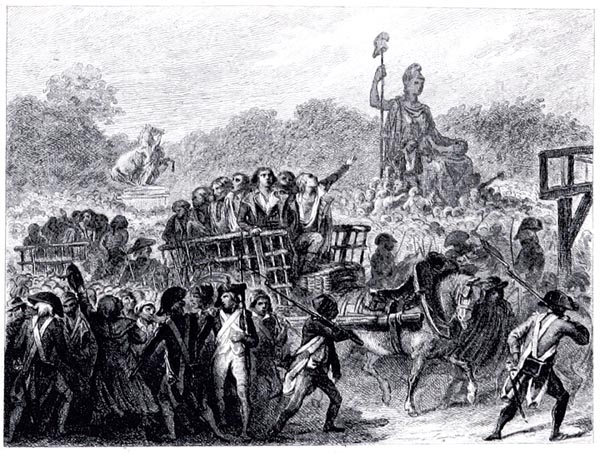

While tragedy reddened the streets, pastoral flourished in the theatre; it was not only a matter of innocent shepherds and virginal shepherdesses: fields, streams, meadows, sheep, doves, an age of gold under thatch, were revived to the plaints of the reed-pipe before cooing Tircis, and the simple tricoteuse, arrived, with her knitting, from the spectacle of the guillotine. If Sanson had had time, he might have played the role of Colin, and Mademoiselle Théroigne de Méricourt, that of Babet. The members of the National Convention pretended that they were the most benign of men: good fathers, good sons, good husbands, they took their little children for walks; they provided them with nursemaids; they shed tender tears at their simple games; they took those little lambs gently in their arms, in order to show them the horsie harnessed to the cart that carried the victims to torture. They sang of nature, peace, pity, charity, ingenuousness, and domestic virtue; those cheerful philanthropists severed the necks of their neighbours with extreme sensitivity, for the greater happiness of the human species.

‘Supplice des Girondins’

Histoire Religieuse, Monarchique, Militaire et Littéraire de la Révolution Française, et de l'Empire, Depuis la Première Assemblée des Notables en 1787, Jusqu'au 20 Avril, 1814 - Étienne Léon de la Mothe Langon (p12, 1840)

The British Library

Book IX: Chapter 3: The changing face of Paris – The Cordeliers Club – Marat

London, April to September 1822. (Revised December 1846)

BkIX:Chap3:Sec1

The face of Paris, in 1792, was not that of 1789 and 1790; this was no longer a new-born Revolution; it was that of a nation marching drunkenly to its destiny, across abysses and by errant ways. People no longer appeared excited, curious, or eager; they were menacing. One met only fearful or ferocious figures in the streets, people hugging the walls of houses so as not to be noticed, or roaming in search of their prey: lowered, timorous glances turned away from you, or grim eyes gazed into yours to penetrate and fathom you.

Variety in clothing had ceased; the old world was stepping aside; men had donned the uniform cloak of the new world, a cloak which was as yet merely the last garment of the victims to follow. The social freedoms displayed at France’s rejuvenation, the freedoms of 1789, the wild, capricious freedoms of an order of things which is destroying itself and has not yet turned to anarchy, were falling back beneath the sceptre of the people: one sensed the approach of a new plebeian tyranny, fecund, it is true and full of hope, but also much more formidable than the decaying despotism of the old monarchy: since the sovereign people, existing everywhere, when it turns tyrant, is a tyrant everywhere; it displays the universal presence of a universal Tiberius.

An alien population of cut-throats from the south mingled with the Parisians; the vanguard of those from Marseilles whom Danton was bringing to Paris for the Tenth of August and the September Massacres, could be recognised by their rags, their bronzed faces, and their air of cowardice and criminality, but crime under a different sun: in vultu vitium, with vice in their faces.

I recognised none of the Legislative Assembly: Mirabeau and the earlier idols of the troubles, were either no more, or had lost their sacred status. To pick up the thread of history, broken by my travels in America, it is necessary to resume the story from a little further back.

A Retrospective View

The flight of the King on the 21st June 1791, forced the Revolution to take an immense step. Brought back to Paris on the 25th of that month, he had been dethroned for the first time, since the National Assembly declared that its decrees would have the force of law, without requiring royal sanction or acceptance. A high court of justice, anticipating the revolutionary tribunal, was established at Orléans. From this moment, Madame Roland, demanded the head of the Queen, thereafter the Revolution would demand hers. The crowd on the Champ-de-Mars had assembled in opposition to the decree which suspended the King from his functions, instead of trying him. His acceptance of the Constitution, on the 14th September, settled nothing. It was a matter of declaring the deposition of Louis XVI; if that had taken place, the crime of the 21st January would not have been committed; the position of the French people altered in relation to the monarchy and vis-à-vis posterity. The members of the Constituent Assembly who opposed his deposition thought to save the crown, and they destroyed it; those who thought to destroy it by demanding the deposition, might have saved it. Almost always, in political matters, the result is the opposite of what is anticipated.

On the 30th of that same month of September 1791, the Constituent Assembly held its last session; the unwise decree of the 17th May previous, which forbad the re-election of outgoing members, created the Convention. Nothing could be more dangerous, more inadequate, more inapplicable to general affairs, than their specific resolutions as individuals or as a body, even though they were honourable.

The decree of the 29th September for the regulation of the popular societies, only served to make them more violent. That was the last action of the Constituent Assembly; it dispersed the next day, and left to France a Revolution.

The Legislative Assembly – The Clubs

The Legislative Assembly, installed on the 1st October 1791, rolled along in that whirlwind which swept up the living and the dead. Disturbances bathed the regions in blood; at Caen, they had their fill of slaughter and ate the heart of Monsieur de Belzunce. The King used his veto to oppose the decree against the émigrés and that which deprived the non-juring priests of all income. These legal actions increased the disturbances. Pétion had become mayor of Paris. The deputies decreed the prosecution of the émigré Princes on the 1st January 1792; on the 2nd, they fixed the beginning of year IV of Liberty as that same 1st of January. Around the 13th of February, red bonnets appeared in the streets of Paris, and the municipality had pikes manufactured. The émigré manifesto appeared on the 1st of March. Austria was armed. Paris was divided into sections, more or less hostile to one another. On the 20th of March 1792, the Legislative Assembly adopted the deathly machine, without which the sentences of the Terror could not have been executed; it was first tried out on corpses, so as to learn its trade on them. One can speak of that instrument as if it were an executioner, since various people, impressed by its excellent service, made presents to it of sums of money, for its maintenance. The invention of that murderous machine, at the very moment when it was needed for crime, is a memorable proof of that intelligence which co-ordinates events, or rather a proof of the hidden action of Providence, when it wishes to change the face of empires.

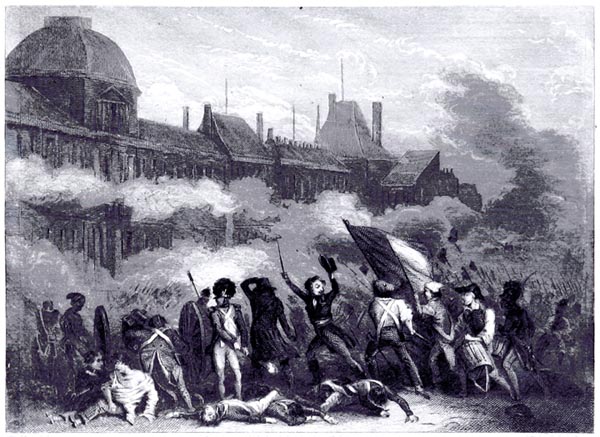

The minister, Roland, at the instigation of the Girondins, had been summoned to the King’s council. On the 20th April, war was declared on the King of Hungary and Bohemia. Marat published L’ami du people, despite the decree which had been issued against him. The Royal-Allemand and Berchini regiments deserted. Isnard spoke of the perfidy of the Court. Gensonné and Brissot denounced the Austrian Committee. An insurrection broke out concerning the King’s Guard, which was dismissed. On the 28th of May, the Assembly entered permanent session. On the 20th of June, the Tuileries Palace was invaded by crowds from the Faubourg Saint-Antoine and Faubourg Saint-Marceau; the pretext was the refusal by Louis XVI to sanction the proscription of priests; the King was at risk of his life. The country was decreed to be in danger. An effigy of Monsieur de Lafayette was burnt. The citizen soldiers of the second federation arrived; those from Marseille, equipped by Danton, were on the way: they entered Paris on the 30th of July, and were quartered by Pétion in the Cordeliers.

‘Attack of the Tuileries, 10 August 1792’

Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 02 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p403, 1881)

The British Library

BkIX:Chap3:Sec2

The Cordeliers

Alongside the national tribune, two concurrent tribunes were established: that of the Jacobins and that of the Cordeliers, at that time the most formidable, since it contributed members to the famous Paris Commune, and furnished it with the means of action. If the creation of the Commune had not taken place, Paris, lacking a focal point, would have divided, and the different district councils would have become rival powers.

The Cordeliers Club was established in the monastery of that name, a fine in reparation for a murder having provided for the building of the church, in 1259, under Saint Louis; it became, in 1590, a refuge for the most famous of the Leaguers.

There are places which seem to be laboratories for generating factions: ‘Notice had been given,’ says L’Estoile (12th July 1593), ‘to the Duc de Mayenne, that two hundred Cordeliers had arrived in Paris, furnished with arms and supportive of the Sixteen, who hold council in the Cordeliers of Paris every day. On that day, the Sixteen, assembled at the Cordeliers, discharged their weapons.’ The fanatics of the League have thus yielded the monastery of the Cordeliers, like a mortuary, to our philosophers of revolution.

The pictures, the sculpted or painted images, the veils, the curtains of the monastery had been pulled down; the basilica, gutted, presented to the gaze only its ruined skeleton. In the apse of the church, where the wind and rain entered through rose-windows without glass, carpenters’ benches served as the president’s office, when a meeting was held in the church. On these benches the red bonnets were deposited, which each orator doffed before mounting the rostrum. The rostrum consisted of four braced struts, with a plank across their X, like a scaffold. Behind the president, next to a statue of Liberty, instruments of ancient justice, so-called, could be seen; many instruments superseded by a single one, a bloodthirsty machine, as complicated mechanisms are replaced by a hydraulic piston. The Jacobin Club when purged borrowed some of these arrangements from the Cordeliers.

Orators

The orators, united in order to destroy, agreed neither on which leaders to choose nor the means to employ; they dealt with beggars, gypsies, thieves, rascals, murderers, to a cacophony of shouts and whistles from their different groups of devils. Their metaphors were derived from articles of murder, borrowed from the filthiest objects, from every species of rubbish heap and dunghill, or drawn from places consecrated to male and female prostitution. Their gestures rendered their imagery palpable; everything was called by its name, with the cynicism of dogs, with an obscene and impious pomp full of oaths and blasphemies. To destroy or create, for death or generation, one only had to interpret that savage argot which deafened the ears. Their harangues, in weak or thunderous voices, were not only interrupted by their opponents: the little black owls, of the cloister without monks and the bell-tower without bells, flew from the broken windows, in hope of spoils; they interrupted the speeches. At first they were called to order by the tinkling of an ineffectual little bell; but since they would not cease their cries, shots were fired at them to ensure their silence: they fell, quivering, fatally wounded, in the midst of the Pandemonium. The fallen timbers, shaky benches, dismantled stalls, fragments of saints overturned and pushed against the walls, served as terraces for the spectators, muddy, dusty, drunk, sweaty, in torn jackets, pikes on shoulders or with bare arms crossed.

The most deformed of that crew obtained preference in speaking. Infirmities of body and soul have played a part in our troubles: pride in suffering has made fine revolutionaries.

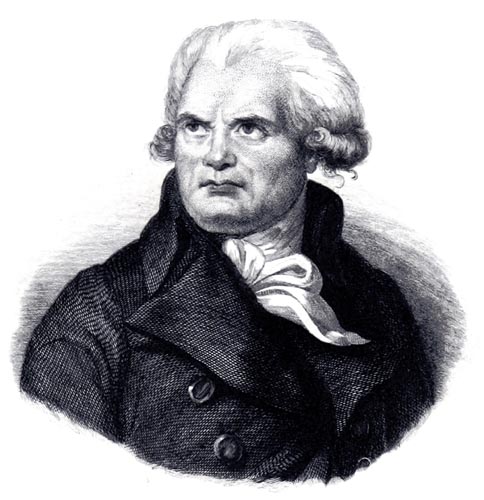

Marat and his friends

According to this precedence of hideousness, a series of Gorgon heads, mingling with the ghosts of the Sixteen, passed by in succession. The former doctor to the Comte d’Artois’ bodyguard, the Swiss abortion Marat, his bare feet in clogs or iron-rimmed shoes, gave the initial peroration, in virtue of his incontestable right. Appointed to the office of jester at the court of the people, he declaimed, with a dull face, and that half-smile of banal politeness that the old-style education gave to every face: ‘People, we must cut off two hundred and seventy thousand heads!’ To this Caligula of the crossroads, succeeded the atheistic cobbler, Chaumette. He was followed by the procureur-général de la lanterne, Camille Desmoulins, Cicero with a stammer, public advisor to murder, exhausted by solitary debauchery, thoughtless republican of the pun and the witty saying, teller of funereal jokes, who said of the September Massacres, everything has passed off well. He agreed to become a Spartan, as long as the recipe for making black broth was left to Méot the restaurateur.

‘Jean-Paul Marat’

Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 02 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p283, 1881)

The British Library

Fouché, rushing there from Juilly and Nantes, studied disaster under those teachers: in the circle of ferocious and attentive beasts at the foot of the chair, he had the air of a well-dressed hyena. He panted for the imminent flow of blood; he already smelt the incense of the processions of dunces and executioners, waiting the day, when, driven from the Jacobin Club, as a thief, atheist, and assassin, he would be appointed a minister. When Marat was down from his plank, that Triboulet of the masses became the toy of his masters: they mocked him, stamped on his feet, crowded round him shouting, none of which prevented him from becoming the leader of the multitude, from climbing the clock tower of the Hôtel-de-Ville, from sounding the tocsin there for a general massacre, and from triumphing over the revolutionary tribunal.

Marat, like Milton’s Sin, was violated by Death: Chénier wrote his apotheosis, David painted him in his bath of blood, while he was compared to the divine author of the Gospels. This prayer was dedicated to him: ‘Heart of Jesus, heart of Marat; O sacred heart of Jesus, O sacred heart of Marat!’ That heart of Marat had for its ciborium a precious pyxis from the storehouse. In a cenotaph made of turf, erected on the Place du Carrousel, one visited the bust, the bath-tub, the lamp, and the writing-case of this divinity. Then the wind changed: the foul remains, poured from the agate urn into another vessel, were emptied into the sewer.

Book IX: Chapter 4: Danton – Camille Desmoulins – Fabre d’Églantine

London, April to September 1822.

BkIX:Chap4:Sec1

The scenes at the Cordeliers, of which I was a witness on two or three occasions, were dominated and presided over by Danton, a Hun the size of a Goth, with a snub nose, flared nostrils, and scarred facial planes, having the look of a policeman joined to that of a cruel and lecherous public prosecutor. In the shell of the church, as in the carcass of the centuries, Danton, with his three male Furies, Camille Desmoulins, Marat and Fabre d’Églantine, organised the September Massacres. Billaud-Varenne proposed setting fire to the prisons and burning all those inside; another member of the Convention voted for drowning all the detainees; Marat declared himself in favour of a general massacre. Danton was beseeched to spare the victims: ‘F... the prisoners,’ he replied. Author of the Commune’s circulars, he invited free men to repeat in their departments the horrors perpetrated at the Carmelite Convent and the prison of the Abbaye.

‘Georges Jacques Danton’

Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 02 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p601, 1845)

The British Library

Let us have regard to history: Sixtus V equated, for the purposes of man’s salvation, the devotion of Jacques Clément to the mystery of the Incarnation, just as they compared Marat to the Saviour of the world; Charles IX wrote to the provincial governors that they should imitate the Saint Bartholomew Massacres, just as Danton ordered patriots to copy the September Massacres. The Jacobins were plagiarists; they were such even when sacrificing Louis XVI in imitation of Charles I. Because crimes have been found embedded in a great social movement, it has been imagined, quite wrongly as it happens, that those crimes produced the greatness of the Revolution, of which they are merely a dreadful pastiche: in a fine but sick nature, passionate or systematic spirits have only admired the convulsions.

Danton, more honest than the English, said: ‘We will not judge the King, we will kill him.’ He also said: ‘These priests, these nobles, are not guilty, but they must die because they are out of place, hindering the movement of events and delaying the future.’ Those words, with the semblance of some terrible profundity, possess no genius: since they assume that innocence is worthless, and the moral order can be removed from the political order without destroying it, which is false.

Danton lacked the conviction of the principals that he maintained; he only rigged himself out in a revolutionary mantle in order to make his fortune. ‘Come and yell with us,’ he counselled a young man; ‘when you are rich, you can do what you want.’ He confessed that if he had not gone over to the Court, it was because it had not wished to pay enough for him: the effrontery of a mind that knows itself and of a corruption that acknowledges itself as a gaping mouth.

Inferior, even in ugliness, to Mirabeau whose agent he had been, Danton was superior to Robespierre, without having, as he had, given his name to his crimes. He retained a sense of religion: ‘We have not, ‘he said, ‘destroyed superstition in order to establish atheism.’ His passions might have been good ones, for the very reason that they were passions. One must admit the part character plays in the actions of men: those guilty in imagination, like Danton, seem, through the very exaggeration of their words and mannerisms, more perverse than the cold-bloodedly guilty, yet in fact they are less so. This comment applies equally to the nation: taken collectively, the nation is a poet, an eager author and actor of the part it plays or is made to play. Its excesses are not so much due to an instinctive natural cruelty as to the delirium of a crowd drunk on public spectacle, especially when it is tragic; a thing so true, that in popular horror shows, there is always something superfluous added to the picture and the emotion.

BkIX:Chap4:Sec2

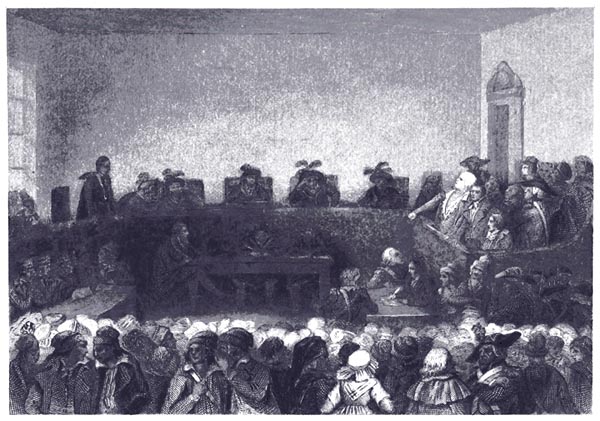

Danton was caught in the trap he set. It did him no good to flick pellets of bread at the noses of his judges, to respond with courage and nobility, to force the tribunal to hesitate, to put the Convention in danger and make it afraid, to reason logically about the hideous crimes by which the very power of his enemies had been created, to cry out, seized by barren repentance: ‘It is I who have instituted this infamous tribunal: I ask pardon of God and men!’ a phrase that has been borrowed more than once. He should have exposed the infamy before being arraigned by the tribunal.

‘Trial of Danton, Camille, Chabot’

The History of the French Revolution. Translated by F. Shoberl, Vol 03 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p407, 1881)

The British Library

All that was left to Danton was to show as little pity for his own death as he had for those of his victims, to lift his gaze as high as the suspended blade: as he did. In the theatre of the Terror, where his feet slid in the previous day’s blood, after casting a glance of powerful contempt at the crowd, he said to the executioner: ‘You will show my head to the people; it is worth the trouble.’ Danton’s head remained in the executioner’s hands, while his headless shade went to join the decapitated shades of his victims: equality, still.

Danton’s deacon and sub-deacon, Camille Desmoulins and Fabre d’Églantine, perished in the same manner as their priest.

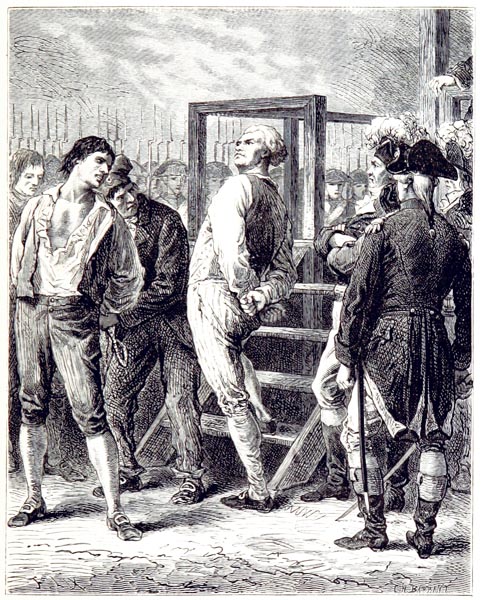

‘Danton et Camille Desmoulins Devant l'Échafaud’

L'Histoire de France Depuis 1789 Jusqu'en 1848, Racontée à mes Petits-Enfants, par M. Guizot. Leçons Recueillies par Madame de Witt, Vol 01 - François Pierre Guillaume Guizot (p229, 1878)

The British Library

At that time, when a maintenance allowance was paid to the guillotine, when one wore in the buttonhole of one’s jacket, instead of a flower, a little gilt guillotine, or a little piece of flesh from the guillotine; at the time when one shouted: ‘Long live Hell!’ When one celebrated the joyful orgies of blood, steel and fury, when one drank to nothingness, when one danced the Dance of Death quite naked, in order not to have the trouble of undressing when going to meet it; at that time, considering everything, what was necessary was to appear at the last supper with the last facetiousness of grief. Desmoulins was invited to Fouquier-Tinville’s tribunal: ‘What age are you?’ demanded the president. ‘The same age as the sans-culotte Jesus,’ replied Camille, jesting. A vengeful obsession forced these cutters of Christian throats to utter endlessly the name of Christ.

It would be unjust to forget that Camille Desmoulins dared to defy Robespierre, and made amends for his errors by his courage. He gave the signal for action against the Terror. A young and charming woman, full of vitality, in proving him capable of love, proved him capable of virtue and sacrifice. Indignation inspired the eloquence of his fearless taunting irony in front of the tribunal; with a noble air he attacked the scaffolds he had helped to raise. Matching his conduct to his words, he did not consent to his torment; he struggled with the executioner in the tumbrel, and arrived at the last abyss half-clothed.

‘Lucie Simplice Camille Benoît Desmoulins’

Histoire de la Révolution Française, Vol 02 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p603, 1845)

The British Library

Fabre d’Églantine, author of a play which will last, showed, contrary to Desmoulins, signs of weakness. Jean Roseau, the Paris executioner under the League, hung for having practised his occupation on behalf of the assassins of president Brisson, could not reconcile himself to the rope. It appears that one does not learn how to die by killing others.

The debates, at the Cordeliers, established for me the fact of a society in the most headlong moment of transformation. I had seen the Constituent Assembly begin the murder of royalty, in 1789 and 1790; I found the corpse of the old monarchy, still almost warm, left in 1792 to its legislative disembowelment: they ripped it apart or dissected it in their low-ceilinged club rooms, as the halberdiers tore and burnt the body of Le Balafré in the cellars of the château of Blois.

Of all the men I recall, Danton, Marat, Camille Desmoulins, Fabre d’Églantine, Robespierre, not one is alive. I met them for a moment on my journey, between a society in America being born, and a dying society in Europe, between the forests of the New World and the solitude of exile: I had experienced only a few months on foreign soil before those lovers of death had already become tired of her. At the distance I now am from those apparitions, it seems to me that having descended into Hell in my youth, I have a confused memory of the worms that I glimpsed crawling on the banks of Cocytus: they complement the various dreams in my life, and have come to have their names inscribed in my annals from beyond the tomb.

Book IX: Chapter 5: Monsieur Malesherbes opinion concerning my emigration

London, April to September 1822.

BkIX:Chap5:Sec1

It was a great pleasure for me to meet Monsieur Malesherbes again and talk to him about my former projects. I reported on my plans for a second voyage which would last nine years; I had nothing to do before that but a little trip to Germany: I would hasten to the army of the Princes: I would hasten back to lambaste the Revolution; all that would be over in two or three months. I would hoist sail and return to the New World with a revolution the less and a marriage the more.

However, my zeal was greater than my belief; I felt that the emigration was stupid and a folly: ‘Belaboured on all sides,’ wrote Montaigne, ‘to the Ghibellines I was a Guelph, to the Guelphs a Guibelline.’ My dislike of absolute monarchy left me under no illusions concerning the party I would be choosing: I would preserve my scruples, and though resolved to sacrifice myself for honour’s sake, I would adopt Monsieur de Malesherbes opinion regarding the emigration. I found him very animated: the crimes taking place in front of his eyes had made that friend of Rousseau’s political tolerance vanish; between the victims’ cause and that of the executioners, he did not hesitate. He believed anything would be better than the state of affairs then existing; he thought, in my case in particular, that a man carrying a sword could not avoid joining the brothers of a King, oppressed and delivered up to his enemies. He approved my return to America and urged my brother to go with me.

I offered him the usual objections regarding an alliance with foreigners, the interests of the country etc. He replied; his general reasons became detailed ones, he cited me embarrassing examples. He offered me the Guelphs and the Ghibellines supporting the armies of the Pope and Emperor; in England, the barons, rising against John Lackland. Finally, in our own time, he cited the Republic of the United States, asking for the assistance of France. ‘So,’ continued Monsieur de Malesherbes, ‘the men most devoted to freedom and philosophy, republicans and Protestants, considered they were free of all guilt in borrowing a force which could grant victory to their party. Without our gold, our ships, and our soldiers, would the New World be free today? I, Malesherbes, I who speak to you, did I not welcome Franklin, in 1776, who came to renew the negotiations initiated by Silas Deane, and was Franklin a traitor? Was American liberty less honourable because it was aided by Lafayette and won by French grenadiers? Any government which, instead of guaranteeing the fundamental laws of society, itself transgresses the laws of equity, the rules of justice, ceases to exist, and returns man to a state of nature. It is then permissible to defend oneself as best one may, to resort to whatever means seem best to overthrow tyranny, and re-establish the rights of each and every one.’

The principles of natural right, previously articulated by the greatest writers, expanded upon by a man such as Monsieur de Malesherbes, and supported by numerous historical examples, silenced me without convincing me: I only yielded in reality to the events of my age, and a point of honour. –

I will add recent examples, to those examples of Monsieur de Malesherbes: during the Spanish War, in 1823, the French Republican party went to serve under the flag of the Cortes, and had no scruples about carrying arms against their own country; the Polish and Italian Constitutionalists had solicited the help of France in 1830 and 1831, and the Portuguese Chartists invaded their country using foreign money and soldiers. We have two weights and two measures: we approve on behalf of an idea, a system, an interest, a man; that which we censure on behalf of another idea, system, interest or man.

Book IX: Chapter 6: I gamble and lose - An adventure in a fiacre (four-wheeled cab) – Madame Roland – The Gate of L’Ermitage – The Second Federation of the 14th July – Preparations for Emigration

London, April to September 1822.

BkIX:Chap6:Sec1

These conversations with the illustrious defender of the king took place at my sister-in-law’s house: she had just given birth to a second son, of whom Monsieur de Malesherbes was the godfather, and to whom he gave the name, Christian. I was present at the baptism of this child, who was only able to know his father and mother at an age when life is without memories, and appears later like a dream that cannot be recalled. The preparations for my departure dragged on and on. My family had thought to arrange a wealthy marriage for me: they found that my wife’s fortune was invested in Church securities; the nation undertook to pay them in its own way. Moreover, Madame de Chateaubriand had lent the scrip of a large part of these securities, with the consent of her guardians, to her sister, the Comtesse du Plessix-Parscau, who had emigrated. So money was still lacking; it was necessary to borrow.

A notary obtained 10,000 francs for us: I was taking them home to the Cul-de-sac Férou, in the form of assignats, when, in the Rue de Richelieu, I met one of my old friends from the Navarre Regiment, Comte Achard. He was a great gambler; he suggested going to the rooms of a certain Monsieur . where we might talk: the devil urged me on; I went upstairs, I gambled, I lost all except fifteen hundred francs, with which, full of remorse and confusion, I climbed into the first carriage that came by. I had never gambled before: the play produced a kind of painful intoxication in me; if the passion had seized me completely, it would have turned my brain. Semi-distracted, I left the cab at Saint-Sulpice, and forgot my pocket-book containing the remains of my wealth. I ran home and told them I had left the whole 10,000 francs in the cab.

I went out again, I turned down the Rue Dauphine; I crossed the Pont-Neuf, not without feeling tempted to throw myself into the water, and made my way to the Place du Palais-Royal, where I had taken the wretched cab. I questioned the Savoyards who watered the nags, and described my particular vehicle; indifferently, they gave me a number. The police superintendent for the district informed me that the number belonged to a man who hired carriages, and lived at the top of the Faubourg Saint-Denis. I went to this man’s house, and remained in the stables all night, waiting for the fiacres to return: a substantial number of them appeared in succession, none of which was mine; at last, at two in the morning, I saw my chariot enter. I had barely time to recognise my two white steeds, when the poor creatures, exhausted, collapsed in the straw, stiff-legged, their bellies distended, their limbs stretched out as if they were dead.

The coachman remembered having driven me. After dropping me, he had picked up a citizen who had got down at the Jacobins; after the citizen, a lady whom he had taken to Number 13, Rue de Cléry; after the lady, a gentleman whom he had set down at the Récollets in the Rue Saint-Martin. I promised the coachman a tip, and at daybreak, set out myself to discover my fifteen hundred francs, as if in search of the North-West Passage. It seemed clear to me that the citizen of the Jacobins had confiscated them by right of sovereignty. The young lady of the Rue de Cléry claimed she had noticed nothing in the fiacre. I arrived without hope, at my third address; the coachman gave, as well as he could, a description of the gentleman he had driven. The porter cried: ‘That’s Père So-and-so!’ He led me through the corridors and empty apartments, to the rooms of a Recollect, who had remained behind alone to make an inventory of his monastery’s furniture. This monk, in a dusty frock-coat, sitting on a pile of rubbish, listened to the tale I told: ‘Are you,’ he said, ‘the Chevalier de Chateaubriand?’ – ‘Yes,’ I replied. ‘Here is your pocket-book,’ he said; ‘I was going to bring it to you when I had finished; I found your address inside.’ It was this monk, hounded and despoiled, engaged in counting conscientiously the relics of his cloister, for those who were banishing him, who restored to me the fifteen hundred francs with which I was going to travel into exile. Lacking this small sum, I could not have emigrated: what would have happened to me? My whole life would have been altered. I would be hanged if I would move a single step today to recover a million.

So passed the 16th June, 1792.

BkIX:Chap6:Sec2

Loyal to my feelings, I had returned from America to offer my sword to Louis XVI, not to become involved with party intrigue. Neither the dismissal of the new King’s Guard, in which Murat made one; the successive ministries of Roland, Dumouriez, and Duport du Tertre; the minor Court conspiracies, nor the great popular uprisings, inspired in me anything other than boredom and contempt. I heard Madame Roland spoken of a great deal, but never saw her; her Memoirs show that she possessed an extraordinarily forceful spirit. She was said to be very pleasant; who knows whether she was sufficiently so at that time to make the stoicism of her unnatural virtues bearable. Certainly, a woman who, at the foot of the guillotine, asks for a pen and ink in order to record the last moments of her journey, to record the discoveries she has made in her transit from the Conciergerie to the Place de la Révolution, such a woman shows a preoccupation with the future, a scorn for life of which there are few examples. Madame Roland had character rather than genius: the first may grant a person the second, the second cannot grant the first.

‘Madame Roland’

The History of the French Revolution. Translated by F. Shoberl, Vol 02 - Louis Adolphe Thiers - President of the French Republic (p100, 1881)

The British Library

On the 19th of June, I went to the valley of Montmorency, to visit Rousseau’s ‘Hermitage’: not because I wished to recall Madame d’Épinay and that depraved and artificial set; but because I wished to say farewell to the retreat of a man, endowed with a talent whose accents stirred me in my youth, even though his morals were antipathetic to my own. Next day, the 20th of June, I was still at the ‘Hermitage’; there I had come across two men taking a walk like me in that same wilderness during that day fatal to the monarchy, indifferent as they were, or might be, I thought, to worldly affairs: the one was Monsieur Maret, of the Empire, the other was Monsieur Barère, of the Republic. The good Barère had come, full of sentimental philosophy, far from the noise, to count the florets of the Revolution in the shadow of Julie. The troubadour of the guillotine, following whose report the Convention decreed that Terror was the order of the day, was saved from that Terror by hiding in a basket of heads; from the depths of the tub, under the scaffold, only his croaking of death could be heard! Barère was one of those tigers that Oppian caused to be born from a light breeze: Zephyri vel Favoni aura: a breath of Zephyr or the West Wind.

Ginguené and Chamfort, those men of letters and my old friends, were delighted by the events of the 20th of June. Laharpe, continuing his lessons at the Lycée, shouted with the voice of Stentor: ‘Madmen! You reply to every representation the people make: Bayonets! Bayonets! Well! There are your bayonets!’ Though my voyage to America had made me a less insignificant person, I could not rise to such great heights of principle and eloquence. Fontanes was at risk because of his former connections with the Société monarchique. My brother was a member of a club of enragés. The Prussians were on the march by virtue of the agreement between the Cabinets of Vienna and Berlin; already a fairly hot encounter had taken place between the French and Austrians, near Mons. It was high time to make a decision.

My brother and I procured forged passports for Lille: we would be wine merchants, in the Parisian National Guard, whose uniform we wore, who were setting out to tender for army supplies. My brother’s manservant, Louis Poullain, known as Saint-Louis, travelled under his proper name: though from Lamballe, in Lower Brittany, he was going to visit his relatives in Flanders. The day of our emigration was set for the 15th of July 1792, the day after the second Festival of the Federation. We spent the 14th in the Tivoli Gardens, with the Rosanbo family, my sisters and my wife. Tivoli belonged to Monsieur Boutin whose daughter had married Monsieur de Malesherbes. Towards the end of the day, we saw a fair number of federates wandering around, the crowd having dispersed, on whose hats in chalk was written: ‘Pétion, or death!’ Tivoli, the starting point for my exile, was to become a rendezvous for amusement and entertainment. Our relatives left us without any sadness; they were persuaded we were going on a pleasure-trip. The fifteen hundred francs I had recovered seemed sufficient riches to see me back in triumph to Paris.

Book IX: Chapter 7: I and my brother emigrate – Saint-Louis’ adventure – We cross the frontier

London, April to September 1822.

![France [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Chateaubriand/interior_chateaubriand_memoirs_bk9chap7sec1.jpg)

‘France [Detail]’

Histoire des Villes de France, Vol 06 - Aristide Guilbert (p869, 1844)

The British Library

BkIX:Chap7:Sec1

On the 15th of July, at six in the morning, we climbed into the diligence: we had booked our seats in the cabriolet, next to the driver; the valet, whom we were not supposed to know, squeezed inside with the other passengers. Saint-Louis was a sleep-walker; in Paris he would go and look for his master during the night, with his eyes open, but fast asleep. He would undress my brother and put him to bed, asleep all the while, replying: ‘I know, I know,’ to anything said to him during his attacks, and only waking when cold water was thrown in his face; he was a man of about forty years of age, nearly six foot high, and as ugly as he was tall. This poor fellow, very respectful, had never served any other master than my brother; he was quite worried when he had to sit at table with us for supper. The passengers, great patriots, talked of hanging aristocrats from the lamp-posts which added to his fears. The idea that at the end of it all, he would have to pass through the Austrian Army, to fight in the Army of the Princes, served to turn his brain. He drank heavily, and climbed into the diligence; we returned to our seat.

In the middle of the night, we heard the passengers shouting, with their heads out of the window: ‘Stop, driver, stop!’ We stopped, the door of the diligence opened, and immediately men and women’s voices cried: ‘Out, citizen, out! We can’t stand it, out, you swine! He’s a brigand! Out, out!’ We got down too. We saw Saint-Louis, pushed and thrown from the coach, getting to his feet, gazing around with wide-open but sleep-filled eyes, set off for Paris, as fast as his legs would carry him, and without his hat. We were unable to acknowledge him, because it would have given us away; we had to abandon him to his fate. Taken and arrested at the first village, he stated that he was Monsieur de Chateaubriand’s servant, and lived in Paris, in the Rue de Bondy. The police passed him from one force to the next till he reached President de Rosanbo’s house; the unfortunate man’s statements served to prove that we had emigrated, and to send my brother and my sister-in-law to the scaffold.

The next morning when the diligence breakfasted, we had to listen to the whole story twenty times over: ‘That man’s mind was disturbed; he dreamt aloud; he said strange things; he was surely a conspirator, an assassin fleeing from justice.’ The well bred citizenesses blushed and waved large Constitutional fans of green paper. In their description we readily recognised the effects of somnambulism, fear and wine.

Arriving at Lille, we went in search of the man who would take us across the frontier. The Emigration had its agents of deliverance who ultimately became agents of perdition. The monarchist party was still powerful, the issue undecided; the weak and cowardly served it, while awaiting the outcome.

We left Lille before the gates were closed: we waited in an out of the way house, and did not set off again until ten at night, in complete darkness; we took nothing with us; we carried sticks in our hands; it was less than a year since I had followed my Dutchman in this way through the forests of America.

We crossed cornfields through which ran lightly-marked paths. French and Austrian patrols were scouring the countryside: we might fall in with one or the other, or find ourselves facing a sentry’s pistol. We made out solitary horsemen far off, motionless, gun in hand; we heard horses’ hooves in sunken lanes; putting our ears to the ground, we heard the steady tramp of marching infantry. After three hours progress, now running, now tiptoeing slowly along, we reached a crossroads in a wood, where a few belated nightingales were singing. A company of Uhlans concealed behind a hedge fell on us with raised sabres. We shouted: ‘Officers wishing to join the Princes!’ We asked to be escorted to Tournai, saying we were in a position to establish our identities. The officer in command positioned us between his troopers and led us away.

When day broke, the Uhlans noticed our National Guard uniforms under our greatcoats, and mocked the colours in which France would soon set out to clothe a subjugated Europe.

BkIX:Chap7:Sec2

In the Tournaisis, an ancient kingdom of the Franks, Clovis spent the first years of his reign: he left Tournai with his companions, called as he was to the conquest of the Gauls: ‘Their weapons gave them every right’ says Tacitus. Through that town, from which, in 486, the first king of the first race issued to found his powerful and enduring monarchy, I passed, in 1792, to rejoin the Princes of the third race, on a foreign soil, and returned again in 1815, when the last King of the French abandoned the kingdom of the first King of the Franks: omnia migrant; everything alters.

Reaching Tournai, I left my brother to struggle with the authorities, and escorted by a soldier I visited the cathedral. Once, Odon d’Orleans, scholar of that cathedral, sitting all night at the door of the church, would teach his disciples the paths of the stars, pointing out to them with his finger the Milky Way and the constellations. I would have preferred to meet that simple astronomer of the eleventh century at Tournai, than the Pandours. I liked those times, when, as the chronicles told me, under the entry for the year 1049, that in Normandy a man was metamorphosed into an ass: which is what was thought to have happened to me, it would appear, when I was with my schoolmistresses, the Couppart sisters. Hildebert, in 1114, had noticed a girl with ears of corn emerging from her own ears: perhaps it was Ceres. The Meuse, which I would soon cross, was suspended in the air in the year 1118, witnessed by Guillaume de Nangis and Albéric. Rigord assures us that, in 1194, between Compiègne and Clermont en Beauvoisis, a tangled hail of rooks fell, bearing coals and starting fires. If the storm, as Gervais de Tilbury assures us, was unable to quench a candle over the window of the Priory of Saint Michael of Camissa, we know too, through him, that in the diocese of Uzès there was a pure and lovely fountain, which changed location whenever anything dirty was thrown into it: today’s consciences would not trouble about such a small thing. – Reader, I am not wasting your time; I am chattering to you while you wait patiently for my brother to finish his negotiations: here he is; he returns after explaining everything to the satisfaction of the Austrian commandant. We are allowed to travel to Brussels, an exile purchased with too much care.

Book IX: Chapter 8: Brussels – Dinner with the Baron de Breteuil - Rivarol – Departure for the Army of the Princes – The route – Encounter with the Prussian Army – I arrive at Trèves

London, April to September 1822.

BkIX:Chap8:Sec1

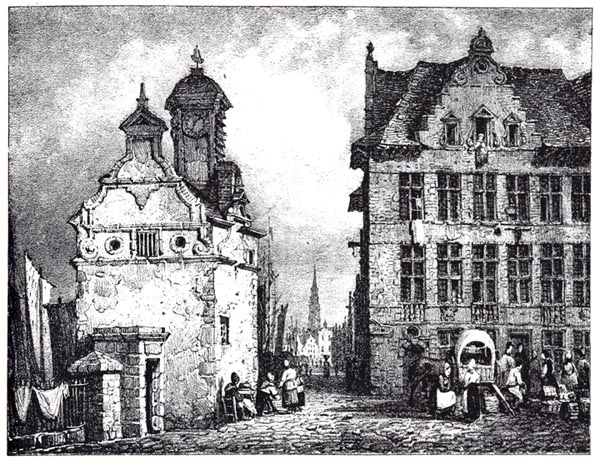

Brussels acted as general quarters for the noblest émigrés: the most elegant women of the Paris and the most fashionable men, those who only travelled as aides-de-camp, waited amongst their distractions for the moment of victory. The latter had beautiful and completely new uniforms; they paraded about with all the strictness of frivolity. Considerable sums of money which they could have lived on for several years, they consumed in a few days: there was scarcely any need to economise, since they would soon be in Paris. These shining knights planned for success in love and glory, in the opposite manner to ancient chivalry. They contemplated us contemptuously as we travelled about on foot, our rucksacks on our backs, we minor gentry from the provinces, impoverished officers reduced to being infantrymen. At the feet of their Omphales, these Hercules twirled the distaffs they had sent us, and which we had returned to them on arrival, contenting ourselves with our swords.

‘La Maison des Barques (Veerhuys)’

Bruxelles à Travers les Àges - Louis Salomon Hymans (p131, 1882)

The British Library

At Brussels, I found my small amount of luggage, which had been smuggled through in advance of my arrival: it consisted of my uniform from the Navarre Regiment, with my linen and my precious papers, from which I could not bear to be separated.

I was invited to dinner at the Baron de Bretueil’s house, with my brother; there I met the Baronne de Montmorency, then young and lovely, and who captivated, at that time, martyred bishops in silk cassocks with golden crosses, young magistrates transformed into Hungarian colonels, and Rivarol, whom I only saw on that one occasion. No one had named him; I was struck by the language of a man who alone held forth, and possessed the right to be heard, like some oracle. Rivarol’s wit harmed his talent, his words harmed his pen. A propos of revolutions, he said: ‘The first blow reaches God, the second only strikes unfeeling marble.’ I had resumed the uniform of a lowly second lieutenant in the infantry; I had to leave at the end of the meal, and my haversack was behind the door. I was still bronzed by American suns and sea air; I had straight, dark hair. My face and my silence bothered Rivarol; the Baron de Breteuil, noticing his uneasy curiosity, satisfied it: ‘Where has your brother the Chevalier arrived from?’ he asked my brother. I replied: ‘From Niagara.’ Rivarol exclaimed: ‘From a Waterfall!’ I fell silent. He hazarded the beginning of a question: ‘Monsieur is going.? – To where one fights,’ I interrupted. We all rose from the table.

This fatal emigration was hateful to me; I was in a hurry to meet my peers, émigrés like myself, with 600 livres income. We were quite foolish, doubtless, but at least we would draw swords and if we achieved success, it would not be us who profited from the victory.

My brother remained in Brussels, with Baron de Montboissier, whose aide-de-camp he had become; I set out alone for Coblentz.

BkIX:Chap8:Sec2

There is nothing that possesses more history than the road I took; it recalled especially various memories or grandeurs of France. I passed through Liège, one of the municipal republics, which rose so many times against its bishops or the Counts of Flanders. Louis XI, though allied to the people of Liège was forced to sack their town, to escape from his ridiculous prison at Péronne.

I went to meet and join those men of war who pinned their fame on similar events. In 1792, the relations between France and Liege were more peaceable: the Abbé de Saint-Hubert was required to send two hunting dogs a year to the successors of King Dagobert.

At Aix-la-Chapelle, another gift, but on France’s part: the mortuary sheet which served for the interment of a most Christian monarch was donated to the tomb of Charlemagne, like a liege’s flag to the ruling fief. Our Kings declared their loyalty and paid homage in this manner, when taking possession of the Eternal heritage; they swore, clasping the knees of death, their lady, that they would be faithful to him, after giving him a feudal kiss on the lips. Moreover, it was the only suzerainty to which France considered itself a vassal. The cathedral of Aix-la-Chapelle was built by Charles the Great and consecrated by Leo III. Two prelates being absent from the ceremony, they were replaced by two Bishops of Maestricht, long dead, who resurrected themselves expressly. Charlemagne, having lost a beautiful mistress, took her corpse in his arms and refused to be separated from it. His passion was attributed to a charm: the young girl’s body was examined, and a little pearl was found beneath her tongue. The pearl was thrown into a marsh; Charlemagne, madly enamoured of the marsh, ordered it drained; there he built a palace and a church, in order to spend his life in one, and his death in the other. The authorities for this are Archbishop Turpin and Petrarch.

At Cologne, I admired the cathedral: if it had been finished it would have been the most beautiful Gothic monument in Europe. Monks were the painters, sculptors, architects and masons of their basilicas; they gloried in their title of master mason, caementarius.

It is curious today to hear ignorant philosophers and chattering democrats speak out against religion, as if those frocked proletarians, those mendicant orders, to whom we owe almost everything, had been gentlemen.

Cologne put me in mind of Caligula and Saint Bruno: I saw the remains of the dikes built by the first at Baiae, and the empty cell of the second at La Grande Chartreuse.

BkIX:Chap8:Sec3

I followed the Rhine as far as Coblentz (Confluentia). The Army of the Princes was no longer there. I crossed those empty kingdoms, inania regna; I saw that lovely Rhine valley, temple of the barbarian muses, where ghostly knights would appear among the ruins of their castles, and one heard the clash of arms at night, when war was at hand.

Between Coblentz and Trèves, I fell in with the Prussian Army: I was passing along the column, when, coming up with the Guards, I saw that they were marching in battle order with canon in line; the king and the Duke of Brunswick were in the centre of the square, which was composed of Frederick’s old grenadiers. My white uniform caught the king’s eye; he sent for me: he and the Duke of Brunswick removed their hats, and saluted the old French Army in my person. They asked me my name, and my regiment, and where I was intending to meet the Princes. This military welcome moved me: I replied with emotion that learning, in America, of the king’s misfortunes I had returned to shed blood in his service. The officers and gentlemen surrounding Frederick William gave a murmur of approval, and the Prussian monarch said: ‘Monsieur, one can always recognise the sentiments of the French aristocracy.’ He took off his hat again, and remained uncovered and motionless, until I had disappeared behind the ranks of grenadiers. Nowadays people speak out against the émigrés; they are the tigers who clawed at their mother’s breast; at the time of which I speak, one followed the old exemplars, and honour counted as highly as country. In 1792, loyalty to one’s oath still ranked as a duty; today, it has become so rare it is regarded as a virtue.

A strange encounter, which had already happened to others, almost made me retrace my steps. They would not allow me to enter Trèves, which the Army of the Princes had already reached: ‘I was one of those men who wait on events to form their decisions; I should have reported three years previously; I arrived when victory was certain. I was not needed; they already had too many war-hardened braves. Every day, cavalry squadrons deserted; even the artillery was leaving en masse and if that continued, no one would know what to do with those men over there.’

A wonderfully partisan illusion!.

I met my cousin Armand de Chateaubriand: he took me under his wing, gathered the Bretons together and pleaded my cause. They summoned me; I explained my situation: I said that I had arrived from America in order to have the honour of serving with my friends; that the campaign was under way, but scarcely begun, so that I was still in time to face the first shot; that moreover, I would return, if that was demanded, but only after having discovered the reason for this unmerited insult. The business was arranged: as I was a good lad, the ranks opened to receive me, and I was only left with an embarrassment of choices.

Book IX: Chapter 9: The Army of the Princes – The Roman amphitheatre - Atala – Henry IV and his shirts

London, April to September 1822.

BkIX:Chap9:Sec1

The Army of the Princes was composed of gentlemen, organised by province, and serving as private soldiers: the aristocracy was returning to its origins, and the origin of the monarchy, at the very moment when that aristocracy and that monarchy were ending, like an old man returning to his infancy. There were also brigades of émigré officers from various regiments, likewise acting as soldiers once more: among their number were my comrades from the Navarre Regiment, led by their colonel, the Marquis de Mortemart. I was sorely tempted to enlist with La Martinière, even if he were still in love; but Armorican patriotism carried the day. I enrolled in the Seventh Breton Company, commanded by Monsieur de Gouyon-Miniac. The nobles from my province had furnished seven companies; an eighth was added of young men from the Third Estate: the steel-grey uniform of this last company differed from that of the other seven, which was royal blue with ermine facings. Men attached to the same cause and exposed to the same dangers perpetuated their political inequality by means of these odious distinctions: the true heroes were the plebeian soldiers, since there was no personal interest involved in the sacrifices they made.

An enumeration of our little army:

The infantry, composed of gentlemen soldiers and officers; four companies of deserters, dressed in the different uniforms of the regiments from which they had come; one artillery company; a few officers from the engineers, with canons, howitzers, and mortars of various calibres (gunners and engineers, almost all of whom espoused the Revolutionary cause, were to be responsible for its widespread success). Excellent cavalrymen, consisting of German carabineers, musketeers under the command of the elderly Comte de Montmorin, and naval officers from Brest, Rochefort and Toulon, supported our infantry. The mass emigration of these latter officers plunged the French Navy back into that enfeebled state from which Louis XVI had rescued it. Never, since the days of Dusquesne and Tourville, had our squadrons won greater glory. My comrades were delighted, but I had tears in my eyes, when I saw those dragoons of the ocean pass by, no longer in command of the vessels with which they had humiliated the English and delivered America. Instead of going in search of new continents to bequeath to France, these companions of La Pérouse sank into the German mud. They rode horses dedicated to Neptune; but they had changed element, and the earth was not their natural place. It was in vain that their commander carried, at their head, the tattered flag from the Belle-Poule, the sacred remnant of that white ensign, from whose shreds honour still hung, but victory had fallen.

We had tents; otherwise we lacked everything. Our muskets of German manufacture, worthless weapons, and terribly heavy, dislocated our shoulders, and were often in no fit state to be fired. I went through the whole campaign with one of those muskets whose hammer refused to fall.

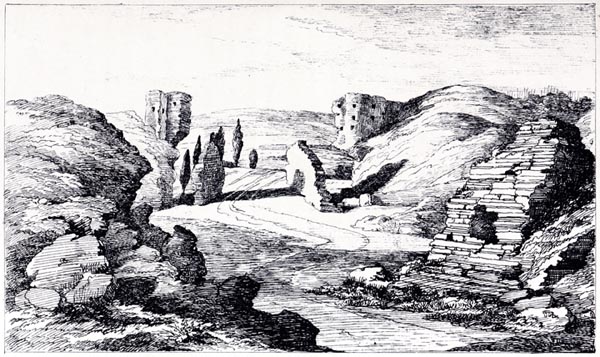

We remained at Trèves for two days. It was a great pleasure to me to see the Roman ruins, after having viewed nameless ruins in Ohio, and to visit that town sacked so often that Salvien said of it: ‘Fugitives from Trèves, you desire entertainments, you beg the Emperors again and again for games in the Circus: for what state I ask, what people, what city? Theatra igitur quaeritis, circum a principibus postulatis? Cui, quaeso, statui, cui populo, cui civitati?’

Fugitives from France, where was that people for whom we wished to restore the monuments of Saint Louis?

‘Amphitheatre - Northern Entrance’

The Stranger's guide to the Roman Antiquities of the City of Trèves - Johann Hugo Wyttenbach (p107, 1839)

The British Library

I sat down, with my musket, among the ruins; I took from my haversack the manuscript of my American voyage; I arranged the individual sheets on the grass around me; I revised and corrected the description of a forest, a passage from Atala, in the remains of a Roman amphitheatre, preparing myself in that way for the conquest of France. Then, I put away my treasure, the weight of which, added to that of my shirts, my cloak, my tin mess-can, my demijohn, and my little Homer, caused me to spit blood. I tried ramming Atala into my pouch with my useless ammunition; my comrades laughed at me, and pulled at the sheets which stuck out on either side of the leather cover. Providence came to my rescue: one night, after sleeping in a hay-loft, I found on waking that the shirts had vanished from my haversack; the papers had been left behind. I gave thanks to God: chance, while preserving my glory, saved my life, since the sixty pounds that weighed on my shoulders would have made me consumptive. ‘How many shirts have I? Henri IV asked his valet, ‘There are still a dozen here, Sire, un-torn. – And handkerchiefs: have I eight? – There are only five at the moment.’ The Béarnais won the battle of Ivry without shirts; I was unable to restore his kingdom to his descendants by losing mine.

Book IX: Chapter 10: A Soldier’s life – The last appearance of the old army of France

London, April to September 1822.

![France [Detail]](https://www.poetryintranslation.com/pics/Chateaubriand/interior_chateaubriand_memoirs_bk9chap10sec1.jpg)

‘France [Detail]’

Histoire des Villes de France, Vol 06 - Aristide Guilbert (p869, 1844)

The British Library

BkIX:Chap10:Sec1

The order was given to march on Thionville. We covered more than fifteen miles a day. The weather was atrocious; we tramped through the rain and mud, singing: Ô Richard! ô mon Roi! or Pauvre Jacques! On arrival at the camping ground, lacking wagons and provisions, we took our mules, which followed the column like an Arab caravan, to search the farms and villages for something to eat. We paid for everything, scrupulously: however I was put on fatigues for absent-mindedly taking a couple of pears from a château garden. A great steeple, a great river, and a great lord, says the proverb, are bad neighbours.

We pitched our tents at random, and had to keep beating at the canvas to flatten the threads and stop the water getting through. We were ten soldiers to a tent; each man in turn was given the task of cooking; one would fetch meat; another bread, another wood, another straw. I made marvellous soup; I received fulsome compliments, especially when I mixed cabbage and milk into the stew, in Breton fashion. Among the Iroquois I had learnt how to tolerate smoke, so that I bore myself bravely in front of the fire of damp, green branches. A soldier’s life is very entertaining; I imagined myself as still among the Indians. Eating our meal under canvas, my comrades asked me for tales of my travels; they repaid me with fine stories of their own; we all told lies like a corporal in a tavern when a conscript is footing the bill.

One thing wearied me, having to wash my clothing; it was often necessary since the obliging thieves had only left me one shirt borrowed from my cousin Armand, plus the one I was wearing. When I cleaned my boots, my handkerchiefs and my shirt by a stream, head down and back in the air, it made me dizzy; the motion of my arms caused an intolerable pain in my chest. I was forced to sit down among the horsetails and water-cresses, and in the midst of military tasks, I amused myself watching the tranquil flow. Lope de Vega presents us with Love’s headband washed by a shepherdess; that shepherdess would have been very useful to me as regards a little turban woven from birch that I had from my Floridian ladies.

An army is usually made up of soldiers of the same age; same height, same strength. Ours was quite otherwise, a motley collection of mature men, old men, and youngsters fresh from their dovecotes, jabbering Norman, Breton, Picard, Auvergnat, Gascon, Provençal and Languedocian. Fathers served with their sons, fathers-in-law with sons-in-law, uncles with nephews, brothers with brothers, cousins with cousins. This gathering, ridiculous as it appeared, had something honourable and touching about it, because it was animated by sincere conviction; it offered a picture of the old monarchy and gave a last glimpse of a dying world. I have seen old noblemen, stern of face, and grey of hair, their coats torn, rucksacks on their backs, muskets over their shoulders, plodding along with the help of a stick, supported under the arm by one of their sons; I have seen Monsieur de Boishue, father of the friend murdered in front of me at the Rennes States, marching sad and alone, his bare feet in the mud, carrying his shoes on the point of his bayonet, for fear of wearing them out; I have seen young men, wounded, lying beneath a tree, while a chaplain in frock-coat and stole knelt by their side, sending them to Saint-Louis, whose heirs they had striven to defend. The whole of this impoverished troop, receiving not a sou from the Princes, made war at its own expense, while the Assembly’s decrees completed its despoliation and consigned our wives and mothers to prison.

Old men in former times were less miserable and less isolated than those of today: if, while still on earth, they lost their friends, little else altered around them; strangers to youth, they were not so to society. Now, a straggler in this world not only has to watch men die, but he sees ideas die too: principles, morals, tastes, pleasures, pains, sentiments, nothing resembles what he has known. He ends his days among a different race of the human species.