François de Chateaubriand

Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe

Book I: Childhood 1768-1777

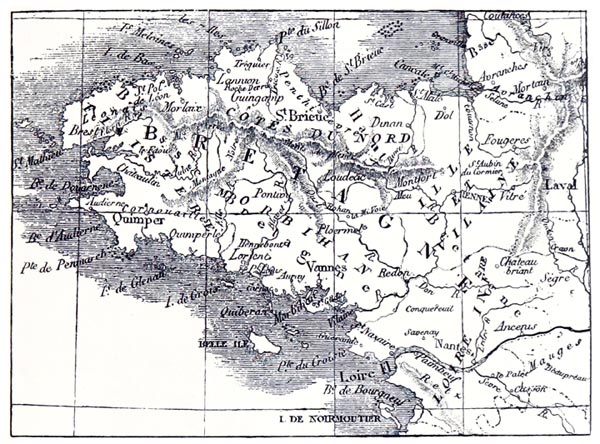

‘Carte de Brétagne’

Le Monde vu par les Artistes. Géographie Artistique...Ouvrage Orné - René Ménard (p931, 1881)

The British Library

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2005 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book I: Chapter 1: Origins

- Book I: Chapter 2: Birth of my brothers and sisters - I arrive in the world.

- Book I: Chapter 3: Plancouët – A Vow – Combourg – My father’s scheme for my education – La Villeneuve – Lucile – Mesdemoiselles Couppart – A bad scholar

- Book I: Chapter 4: Life of my maternal grandmother and her sister at Plancouët – My uncle the Comte de Bedée, at Monchoix – Release from my nurse’s vow

- Book I: Chapter 5: Gesril – Hervine Magon – The fight with the two ship’s boys

- Book I: Chapter 6: A note from Monsieur Pasquier – Dieppe – A change in my education – Spring in Brittany – Ancient Forest – Pelagian Fields – Moonset over the sea

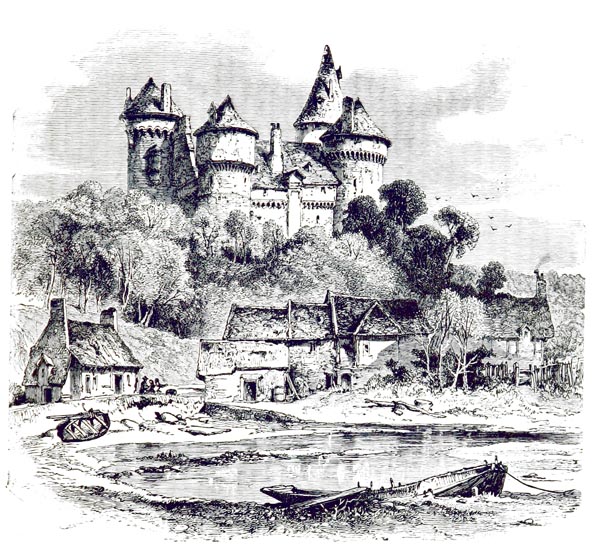

- Book I: Chapter 7: Departure for Combourg – A description of the Château

Book I: Chapter 1: Origins

La Vallée-aux-Loups, near Aulnay, this 4th October 1811.

BkI:Chap1:Sec1

It is four years now since, on my return from the Holy Land, I bought a gardener’s house, hidden among the wooded hills, close to the hamlet of Aulnay, in the neighbourhood of Sceaux and Châtenay. The uneven, sandy ground attached to the house was no more than an overgrown orchard, with a ravine and a clump of chestnut-trees at its far end. This narrow space seemed appropriate to contain my wide-ranging hopes; spatio brevi spem longam reseces (since time is short, limit that far-reaching hope). The trees I’ve planted here have prospered: they are still so small that I overshadow them when I step between them and the sun. One day, repaying me that shade, they will protect my old age as I protect their youth. As far as possible I have selected them from the various climes where I have wandered; they recall my travels, and nourish new illusions in the depths of my heart.

If ever the Bourbons return to the throne, I will ask as recompense for my loyalty, only that they enrich me enough to join the edge of the surrounding woods to my property: ambition possesses me; I would like to extend my walks by a few acres: knight-errant though I am I have the sedentary habits of a monk: since inhabiting this retreat, I don’t think I have set foot outside my close three times. If my pines, firs, larches and cedars ever fulfil their promise, the Vallée-aux-Loups will become a veritable charterhouse. When Voltaire was born at Châtenay, on 20th February 1694, what did this hillside look like where in 1807 the author of Le Genie du Christianisme was to retire?

The place pleases me; since, for me, it has replaced my ancestral fields; I have paid for it with the products of my dreams and my waking hours; it is to the great wilderness of Atala that I owe the little wilderness of Aulnay; and to create this refuge I have not, like the American settlers, despoiled the Florida Indians. I am attached to my trees; I have addressed elegies, sonnets, and odes to them. There is not one of them that I have not tended with my own hands, that I have not rescued from root-beetles, from caterpillars glued to its leaves; I know them all by name as if they were my children: they are my family, I have no other, and I hope to die among them.

‘The Banyan-Tree, or Indian Fig (Ficus Indica)’

Introduction To Structural And Systematic Botany, and Vegetable Physiology - Asa Gray (p91, 1860)

Internet Archive Book Images

BkI:Chap1:Sec2

Here, I wrote Les Martyrs, Les Abencerages, L’Itinéraire and Moïse; what shall I do now with these autumn evenings? This 4th October 1811, the anniversary of my name day and my entry into Jerusalem, tempts me to commence the story of my life. The man who gives France power over the world today, only to trample her underfoot, that man, whose genius I admire, and whose despotism I abhor, that man envelops me with his tyranny as with another solitude; but though he crushes the present, the past defies him, and I remain free, in everything that preceded his glory.

Most of my feelings remain buried deep in my heart, or have only been revealed in my works as if applied to imaginary beings. Now that I miss my chimeras, without pursuing them, I want to revive the inclinations of my best years: these Mémoires will be a mortuary temple erected by the light of my memories.

My father’s birth and the ordeals he endured in his early life, endowed him with one of the most sombre characters there has ever been. This character influenced my ideas by terrifying my childhood, saddening my youth, and determining the nature of my upbringing.

I was born a gentleman. As I see it, I have profited from this accident of the cradle, maintaining that firm love of liberty that especially belongs to an aristocracy whose last hour has struck. Aristocracy has three successive ages: the age of superiority, the age of privilege, the age of vanity; leaving the first behind it degenerates in the second and expires in the last.

BkI:Chap1:Sec3

Anyone can enquire about my family, if the fancy takes them, in Moréri’s dictionary, in the various histories of Brittany by D’Argentré, Dom Lobineau and Dom Morice, in the Histoire généalogique du plusieurs maisons illustres de Bretagne by Père Dupaz, in Toussaint Saint-Luc, Le Borgne, and finally in the Histoire des grands officiers de la Couronne, by Père Anselme. (This genealogy is summarized in the Histoire généalogique et héraldique des Pairs de France, des grands dignitaries de la Couronne, by Monsieur Le Chevalier de Courcelles.)

The proofs of my lineage were established by Chérin, for the admission of my sister Lucile as a canoness to the Chapter of L’Argentière, from which she was to pass to that of Remiremont; they were produced for my presentation to Louis XVI, again for my affiliation to the Order of Malta, and again, for the last time, when my brother was presented to that same unfortunate Louis XVI.

My name was first written as Brien, then as Briant and Briand, through an invasion of French orthography. Guillaume le Breton gives it as Castrum-Briani. There isn’t a name in France free of such variations. What is the correct spelling of Du Guesclin?

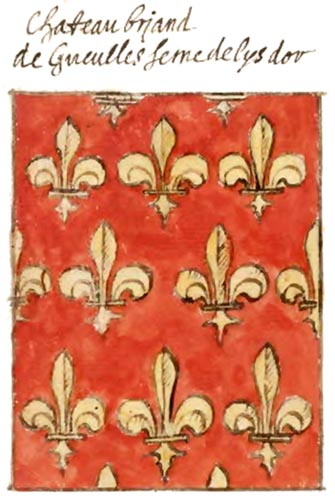

About the beginning of the eleventh century the Briens gave their name to an important château in Brittany, and the château became the seat of the barony of Chateaubriand. The original arms of Chateaubriand were pine-cones with the device: Je sème l’or (I scatter gold). Geoffroy, Baron de Chateaubriand travelled to the Holy Land with St Louis. Taken prisoner at the battle of the Massorah, he returned to France, his wife Sibylle dying of joy at the shock of seeing him again. St Louis, as a reward for his services, granted him and his heirs, in exchange for their ancient coat of arms, a shield of gules, powdered with golden fleurs-de-lys: Cui et ejus haeredibus, states a cartulary in Bérée Priory, sanctus Ludovicus tum Francorum rex, propter eius probitatem in armis, flores lilii auri, loco pomorum pini auri, contulit.

BkI:Chap1:Sec4

The Chateaubriands split into three branches from the very start: the first, known as the Barons de Chateaubriand, and the root-stock of the other two, originating in the year 1000 in the person of Thiern, son of Brien, grandson of Alain III, Count or Leader of Brittany: the second, named the Seigneurs des Roches Baritaut, or Seigneurs du Lion d’Angers; and the third going under the name of the Sires de Beaufort.

When the line of the Sires de Beaufort ended, in the person of Dame Renée, one Christophe II a collateral branch of this line held a share of land at La Guérande en Morbihan. At this time, towards the middle of the seventeenth century, there was widespread confusion in the ranks of the nobility, names and titles having been usurped. Louis XIV ordered an enquiry, in order to re-establish everyone’s rights. Christophe was maintained in possession, on proof of his descent from ancient nobility, of his title, and his coat of arms, by order of the Tribunal established at Rennes in order to re-validate the nobility of Brittany. The order was dated 16th September 1669; with this text:

‘Order of the Tribunal established by the King (Louis XIV) for the re-establishment of the nobility in Brittany, given 16th September 1669: Between the King’s Attorney-General and Monsieur Christophe de Chateaubriand, Sieur de La Guérande: the which declares the aforesaid Christophe to be of noble extraction, and permits him to adopt the rank of Chevalier, and maintains his right to bear arms, of gules powdered with golden fleurs-de-lys, to any number, and this after the production by him of his authentic titles, of which there here appear, etc., etc., the aforesaid order signed by Malescot.’

‘Chateaubriand - de Gueules Semé de Lys d'Or’

Armoiries de Familles Chevaleresques et Anoblies Bretonnesi (17th Century)

Les Tablettes Rennaises

This order confirms that Christophe de Chateaubriand de la Guérande was directly descended from the Chateaubriands who were Sires de Beaufort: the Sires de Beaufort being linked by historical documents to the first Barons de Chateaubriand. The Chateaubriands of Villeneuve, Plessis and Combourg are cadet branches of the Chateaubriands of La Guérande, as is shown by the descendants of Amaury, brother of Michel, which Michel was the brother of Christophe de La Guérande, his lineage confirmed by this order of reformation of the nobility, given above here, of 16th September 1699.

BkI:Chap1:Sec5

After my presentation to Louis XVI, my brother thought to augment my fortune as a younger son by providing me with some of those ecclesiastical benefits known as bénéfices simples. There was only one practical means of achieving this, since I was a layman and a soldier, which was to enrol me in the Order of Malta. My brother sent my proofs to Malta, and soon afterwards a request in my name, to the Chapter of the Grand Priory of Aquitaine, sitting at Poitiers, asking that commissioners be appointed to pronounce on the matter, urgently. Monsieur Pontois was at that time the archivist, Vice-Chancellor and genealogist of the Order of Malta at the Priory.

The President of the Chapter was Louis-Joseph des Escotais, Bailiff and Grand Prior of Aquitaine, assisted by the Bailiff of Freslon, the Chevalier de La Laurencie, the Chevalier de Murat, the Chevalier de Lanjamet, the Chevalier de La Bourdonnay-Montluc, and the Chevalier du Bouëtiez. The request was granted on the 9th, 10th and 11th of September 1789. It was said, in the terms of admission of the Mémorial, that I deserved the favour I was soliciting on more than one ground, and that considerations of the greatest weight made me worthy of the honour I requested.

And all this took place after the taking of the Bastille, on the eve of the scenes of 6th October 1789, and the transfer of the Royal Family to Paris! And in the session of the 7th August of that year 1789, the National Assembly had abolished the titles of the nobility! How did the Chevaliers and examiners of my credentials come to the conclusion that I deserved the favour I was soliciting on more than one ground, etc., I who was merely an insignificant second-lieutenant of infantry, unknown, without credit, favour or fortune?

BkI:Chap1:Sec6

My brother’s eldest son (I am adding this in 1831 to my original text written in 1811), Comte Louis de Chateaubriand, had married Mademoiselle d’Orglandes, by whom he had five daughters and a son, named Geoffroy. Christian, younger brother of Louis, great-grandson and godchild of Monsieur de Malesherbes, and with a striking resemblance to him, served with distinction in Spain as a captain in the Dragoon Guards, in 1823. He has become a Jesuit in Rome. The Jesuits compensate for solitude to the extent that they relinquish the earth. Christian nears death at Chieri, near Turin: old and ill, I should precede him; but his virtues ought to call him to heaven before me, who still have plenty of faults to bemoan.

By the division of the family patrimony, Christian inherited the estate of Malesherbes, and Louis the estate of Combourg. Christian not considering the equal division legitimate, wished, in turning his back on the world, to relinquish the worldly goods that did not belong to him and gave them to his elder brother.

In view of my lineage, it would be my affair alone if I were to inherit my father’s and brother’s conceit in believing myself a younger scion of the Dukes of Brittany, descended from Thiern, grandson of Alain III.

The aforesaid Chateaubriands have twice mingled their blood with the blood of the English sovereigns, Geoffroy IV de Chateaubriand having taken as his second wife Agnès de Laval, grand-daughter of the Count of Anjou and Matilda, daughter of Henry I; Marguerite de Lusignan, widow of the English King, and grand-daughter of Louis-le-Gros, was married to Geoffroy V, twelfth Baron de Chateaubriand. Regarding the Spanish royal race we find Brien, younger brother of the ninth Baron de Chateaubriand, who was married to Jeanne, daughter of Alphonse, King of Aragon. Regarding the great families of France, also, it is believed that Édouard de Rohan took to wife Marguerite de Chateaubriand, and that one Croy married Charlotte de Chateaubriand. Tinteniac, victorious in the Combat des Trente, and du Guesclin the Constable made alliance with us in all three branches. Tiphaine du Guesclin, grand-daughter of Bertrand du Guesclin’s brother, ceded the ownership of Plessis-Bertrand to Brien de Chateaubriand, her cousin and heir. In the treaties, the Chateaubriands were assigned in order to guarantee the peace of the Kings of France, at Clisson, to the Baron de Vitré. The Dukes of Brittany sent the Chateaubriands the minutes of their assizes. The Chateaubriands became Grand Officers of the Crown, and illustrious at the court of Nantes; they received commissions to defend the security of their province against the English. Brien I fought at the Battle of Hastings: he was the son of Eudon, Comte de Penthièvre. Guy de Chateaubriand was one of the Knights whom Arthur of Brittany assigned to accompany his sons during his embassy to Rome in 1309.

BkI:Chap1:Sec7

I would never finish if I were to recount everything of which I have chosen to give only a short summary: the note I intend to place at the end, out of consideration for my two nephews, who are no doubt as well versed as I am in these old woes, will replace what I omit in this text. However, these days, people go a little too far; it has become common to declare that one is working class, that one has the honour of being the son of a man of the soil. Are these boasts as disinterested as they are philosophical? Are they not a way of siding with the stronger party? The Marquesses, Counts and Barons of our day, possessing neither land or privileges, three-quarters of them dying of hunger, denigrating one another, refusing to recognise one another, challenging one another’s titles; these nobles, whose own names are denied them, or who are only granted one with reservations, can they inspire fear? However I wish to be pardoned for having been obliged to descend to these puerile recitations, in order to explain my father’s ruling passion, a passion which formed the crux of my youthful drama. For my part, I neither glorify nor complain of the old social order or the new. If, in the first, I was the Chevalier or Vicomte de Chateaubriand, in the second I am François de Chateaubriand; I prefer my name to my title.

My father would readily, like a great medieval land-owner, have called God the Gentleman up there, and named Nicodemus (the Nicodemus of the Gospels) a holy gentleman. Now, passing by way of my begetter, we arrive at Christophe, sovereign lord of La Guérande, and descend in direct line from the Barons of Chateaubriand to myself, Francois, vassal-less, penniless Lord of the Vallée-aux-Loups.

Going back through the lineage of the Chateaubriands, and its three branches, two of the branches died out, while the third, that of the Sires de Beaufort, extended by a branch (the Chateaubriands of La Guérande), grew poorer, an inevitable consequence of the country’s laws: the elder sons appropriated two thirds of the estate, according to Breton custom; the younger sons divided a mere third of the paternal inheritance between them. The erosion of the latter’s meagre inheritance occurred all the more rapidly through marriage; and as the same distribution of two to one also applied to their offspring, the younger sons of younger sons swiftly arrived at the division of a pigeon, a rabbit, a duck-pond and a hunting dog, though they still remained noble knights and powerful lords of a dove-cote, a toad-hole, and a rabbit-warren. In the old aristocratic families you find a quantity of younger sons: tracing them through two or three generations, then they vanish, descending little by little to the plough, or absorbed by the working classes, without anyone knowing what has become of them.

BkI:Chap1:Sec8

The head of the family in name, and arms, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, was Alexis de Chateaubriand, Lord of La Guérande, the son of Michel, which Michel had a brother Amaury. Michel was the son of that Christophe, confirmed in his lineage from the Sires de Beaufort and Barons de Chateaubriand by the previously mentioned order. Alexis de la Guérande was a widower; a confirmed drunkard, spending his days in drink, living in disorder amongst his servants, and employing the noblest title-deeds of his house to cover jars of butter.

Contemporary with this head of the family in name and arms, there lived his cousin François, the son of Amaury, younger brother of Michel. Francois, born on the 19th February 1683, possessed the little estates of Les Touches and La Villeneuve. He married, on the 27th August 1713, Pétronille-Claude Lamour, Dame de Lanjégu, by whom he had four sons: François-Henri, René (my father), Pierre, Lord of Le Plessis, and Joseph, Lord of Le Parc. My grandfather, François, died on the 28th March 1729; my grandmother, whom I knew in my childhood, still had beautiful smiling eyes in the shadow of her old age. At the time of her husband’s death she was living in the manor of La Villeneuve, near Dinan. My grandmother’s whole fortune did not exceed 5,000 livres in rents, of which her eldest son took two-thirds, 3,333 livres; 1,667 livres remained for the three younger sons, from which sum the eldest once more deducted the major part.

To complete the misery, my grandmother was thwarted in her plans by her sons’ characters: the eldest François-Henri, on whom the magnificent estate of Villeneuve devolved, refused to marry and became a priest; but instead of applying for the benefices his name could have procured and with which he might have supported his brothers, he sought nothing, out of pride and indifference. He buried himself in a country living and was successively rector of Saint-Launeuc and Merdrignac in the diocese of Saint-Malo. He had a passion for poetry; I have seen a good number of his verses. The jovial character of this sort of aristocratic Rabelais, the cult of the Muses practised by this Christian priest in a presbytery excited curiosity. He gave away all he owned and died bankrupt.

The last of the four brothers Joseph went to Paris and immured himself in a library: ever year he received 416 livres, his portion as a younger son. He went unnoticed in the world of books; he devoted himself to historical research. Throughout his short life, he wrote to his mother every January 1st, the only sign of existence he ever gave. Singular destiny! There were my two uncles, the one a scholar, the other a poet; my elder brother wrote quite good verse; one of my sisters, Madame de Farcy, had the true poetic gift; another of my sisters, Comtesse Lucile, a canoness, deserves to be known for a few admirable pages; while I have blotted plenty of paper. My brother perished on the scaffold, my two sisters quitted a life of suffering after languishing in prison; my two uncles failed to leave enough to pay for the four planks of their coffin; while literature has caused me joy and pain, and with God’s help I still look forward to dying in the workhouse.

BkI:Chap1:Sec9

My grandmother, worn out trying to make something of her eldest and youngest sons, could do nothing for the other two, René, my father, and Pierre, my uncle. This family which has ‘scattered gold’, according to its motto, could see from its country seat the rich abbeys it had founded, and which enclosed its ancestors. It had presided over the States of Brittany, being possessed of one of the nine baronies; it had added its signature to the treaties between sovereigns, served as surety for Clisson, and still lacked the influence to obtain a second-lieutenant’s commission for the heir to its name.

The one recourse left to the poverty-stricken Breton nobility was the Royal Navy: they decided to take advantage of it in my father’s case; but it meant him going to Brest, living there, paying his instructors, buying his uniform, weapons, books, mathematical instruments: how to defray all these expenses? The commission requested from the Minister for the Navy failed to arrive, for want of a patron to solicit its despatch: the lady of Villeneuve fell ill with grief.

Then my father showed the first sign of that determined character that I later recognised in him. He was about fifteen years old: becoming aware of his mother’s anxiety, he approached the bed where she lay and said: I don’t wish to be a burden on you, any longer.’ At this my grandmother began to cry (I’ve heard my father describe this scene a score of times). ‘René,’ she replied, ‘what would you do? Cultivate your field.’ ‘It can’t feed us all: let me go.’ ‘Ah well,’ said his mother, ‘go then, wherever God wishes you to go.’ She embraced him, in tears. That very evening my father quitted his mother’s farm and went to Dinan where one of our relations gave him a letter of recommendation to a citizen of Saint-Malo. The orphan adventurer was signed on as a volunteer, on an armed schooner, which set sail a few days later.

The little republic of Saint-Malo at that time upheld the honour of the French flag at sea. The schooner rejoined the fleet that Cardinal Fleury was sending to aid Stanislas, besieged in Danzig by the Russians. My father set foot on shore and found himself in the memorable battle that fifteen hundred Frenchmen, commanded by the brave Breton De Bréhan, Comte de Plelo, waged on the 29th May 1734, against forty thousand Muscovites, commanded by Munich. De Bréhan, diplomat, warrior, poet, was killed, and my father wounded twice. He returned to France and signed on again. Shipwrecked on the coast of Spain, he was attacked and despoiled by robbers in Galicia; he took passage by ship to Bayonne, and appeared once more beneath the family roof. His courage and his disciplined nature had made him known. He sailed to the West Indies; he enriched himself in the colonies, and laid the foundations of a new family fortune.

BkI:Chap1:Sec10

My grandmother entrusted to her son René her son Pierre, Monsieur Chateaubriand du Plessis, whose son, Armand de Chateaubriand, was shot, on Bonaparte’s orders, on Good Friday of 1809. He was one of the last French nobles to die for the Monarchist cause. My father undertook to look after his brother, though he had contracted, from habitual suffering, a rigidity of character which he retained all his life; Virgil’s Non ignara mali is not always true: adversity may engender harshness as well as tenderness.

Monsieur de Chateaubriand was tall and gaunt; he had an aquiline nose, thin pale lips, and small deep-set eyes, sea-green or glaucous, like those of lions or barbarians of old. I have never seen eyes like his: when anger filled them the glittering pupils seemed to detach themselves and issue forth to strike you like bullets.

One passion alone gripped my father, that of his name. His habitual state was a profound sadness that age deepened, and a silence that he only emerged from to vent his anger. Avaricious, in the hope of restoring his family to its former glory, haughty with the nobles at the States of Brittany, harsh with his vassals at Combourg, taciturn, despotic and menacing at home, seeing him one felt fear. If he had lived to experience the Revolution, and if he had been younger, he would have played an important part, or been massacred in his château. He certainly possessed genius: I have no doubt that in charge of the administration or the army he would have proved an extraordinary man.

BkI:Chap1:Sec11

It was on his return from America that he decided to marry. Born on the 23rd September 1718, he married at thirty-four, on the 3rd July 1753, Apolline-Jean-Suzanne de Bedée, born the 7th April 1726, the daughter of Monsieur Ange-Annibal, Comte de Bedée, Liege Lord of La Bouëtardais. He established himself with her at Saint-Malo, twenty miles or so from where they had both been born, so that from their house they could see the horizon under which they had entered the world. My maternal grandmother, Marie-Anne de Ravenel de Boisteilleul, Madame de Bedée, born at Rennes on the 16th October 1698, had been brought up at Saint-Cyr during the last years of Madame Maintenon: her education was passed on to her daughters.

My mother, endowed with plenty of spirit and a prodigious imagination, had been formed by reading Fénelon, Racine, and Madame de Sévigné, and fed with anecdotes of Louis XIV’s court; she knew the whole of Cyrus by heart. Apolline de Bedée, with large features, was small, dark, and plain; the elegance of her manners and the liveliness of her temperament contrasted with my father’s severity and calm. Loving society as much as he loved solitude, as high-spirited and animated as he was cold and unmoving, she had not a single taste that was not opposed to those of her husband. The opposition she experienced made her melancholy, instead of happy and light-hearted. Obliged to be silent when she would have wished to speak, she compensated for it with a kind of noisy sadness broken by sighs, which alone interrupted my father’s mute sadness. In piety, my mother was an angel.

Book I: Chapter 2: Birth of my brothers and sisters - I arrive in the world.

La Vallée-aux-Loups, 31st December 1811.

BkI:Chap2:Sec1

My mother gave birth at Saint-Malo to a son who died in infancy, and who was named Geoffroy, like nearly all the eldest sons in my family. This son was followed by another and by two daughters who lived only a few months.

These four children died of a rush of blood to the brain. Finally, my mother brought a third boy into the world, named Jean-Baptiste: it was he who later became the grandson-in-law of Monsieur de Malesherbes. After Jean-Baptiste four daughters were born: Marie-Anne, Bénigne, Julie and Lucile, all four of rare beauty: and of whom only the two eldest survived the storms of the Revolution. Beauty that serious frivolity remains when all the rest have gone. I was the last of these ten infants. It is probable that my four sisters owe their existence to my father’s desire to see his name secured by the arrival of a second boy; I tarried, I had an aversion for life.

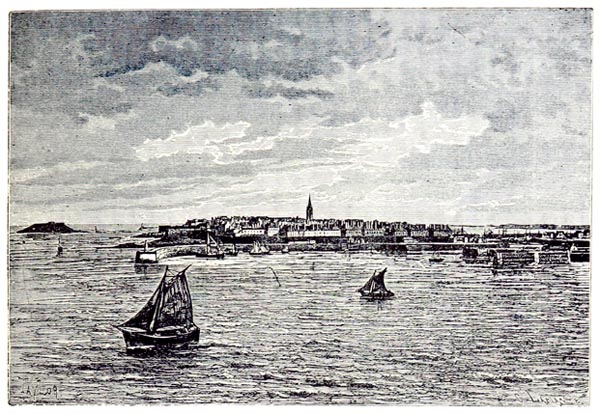

‘Saint-Malo’

La France Pittoresque. Ouvrage Illustré - Jules Gourdault (p81, 1893)

The British Library

Here is my baptismal certificate:

Extract from the civil register of the Commune of Saint-Malo for the year 1768.

‘François-René de Chateaubriand, son of René de Chateaubriand and Pauline-Jeanne Suzanne de Bedée, his wife, born on the 4th of September 1768, baptised on the following day by us, Pierre-Henry Nouail, Vicar-General to the Bishop of Saint-Malo. Stands godfather, Jean-Baptiste de Chateaubriand his brother, and godmother, Françoise-Gertrude de Contades, who sign with the father. As signatories to the register: Contades de Plouër, Jean-Baptiste de Chateaubriand, Brignon de Chateaubriand, De Chateaubriand and Nouail, Vicar-General.’

One sees that I was mistaken in my writings: I set myself down as being born on the 4th October not the 4th September; my Christian names are François-René, and not François-Auguste.

The house my parents occupied at that time is situated in a dark, narrow street in Saint-Malo, called the Rue des Juifs: today the house has been converted into an inn. The room in which my mother gave birth overlooks a deserted stretch of the city walls, and from the windows of that room one can perceive the sea, stretching as far as the eye can see, breaking on the reefs. My godfather, as one can see from my baptismal certificate, was my brother, and my godmother was the Comtesse de Plouër, daughter of the Maréchal de Contades. I was near death when I entered the world. The roaring of the waves, whipped up by a squall heralding the autumn equinox, prevented my cries being heard: these details have often been told to me; their sadness has never been erased from my memory. There is never a day that, thinking of what I have been, I do not picture again in my thoughts the rock on which I was born, the room where my mother inflicted life on me, the tempest whose roaring lulled my first sleep, the unfortunate brother who named me, with a name that I have almost always trailed amidst misery. Heaven seems to have brought these diverse circumstances together in order to place an image of my destiny over my cradle.

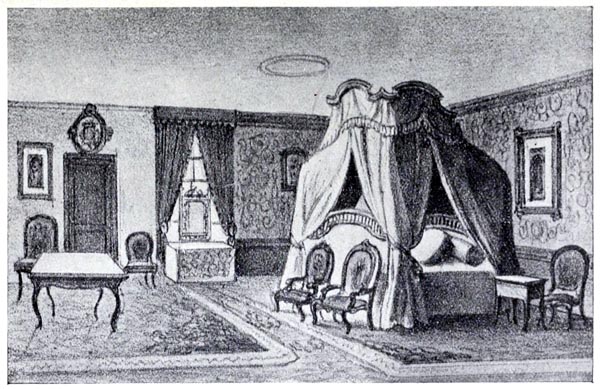

‘Chambre où est né Chateaubriand’

Morceaux Choisis: Extraits des Oeuvres Complètes - Vicomte de François-René Chateaubriand (p28, 1915)

Internet Archive Book Images

Book I: Chapter 3: Plancouët – A Vow – Combourg – My father’s scheme for my education – La Villeneuve – Lucile – Mesdemoiselles Couppart – A bad scholar

La Vallée-aux-Loups, January 1812.

BkI:Chap3:Sec1

Emerging from my mother’s womb, I suffered my first exile; they relegated me to Plancoët, a pretty village situated between Dinan, Saint-Malo and Lamballe. My mother’s only brother, the Comte de Bedée, had built the Château of Monchoix close to the village. My maternal grandmother’s property in the region extended as far as the little market town of Corseul, the Curiosolites of Caesar’s Commentaries. My grandmother, long a widow, lived with her sister Mademoiselle de Boisteilleul, in a hamlet separated from Plancoët by a bridge, and called L’Abbaye, because of the Benedictine abbey, sacred to Our Lady of Nazareth.

My wet nurse was found to be sterile; another poor Christian took me to her breast. She dedicated me to the patroness of the hamlet, Our Lady of Nazareth, and promised her I would wear blue and white in her honour until I was seven. I was only a few hours old, and the burden of time had already marked my brow. Why did they not let me die? It entered into God’s counsels to answer the vow, made in obscurity and innocence, with the preservation of a life which idle fame threatened to extinguish.

That vow, of the Breton peasant-woman, is no longer of our century: it was however a touching thing, which a divine Mother’s intercession established between a child and Heaven, sharing the concerns of the earthly mother.

After three years I was taken back to Saint-Malo; it was already seven years since my father had regained the Combourg estate. He wished to enter again into the possessions his ancestors had held; unable to negotiate for the lordship of Beaufort, which had passed to the Goyon family, nor the barony of Chateaubriand, which had fallen to the house of Condé, he turned his gaze towards Combourg, which Froissart calls Combour: several branches of my family had owned it through marriages with the Coëtquens. Combourg defended Brittany against the Normans and the English: Junken, Bishop of Dol, built it in 1016; the great tower dates from 1100. Marshal de Duras, who had Combourg from his wife, Maclovie de Coëtquen, daughter of a Chateaubriand, came to an arrangement with my father. The Marquis du Hallay, an officer in the mounted grenadiers of the Royal Guard, who is almost too well known for his bravery, is the last of the Coëtquen-Chateaubriands: Monsieur du Hallay has a brother. The same Marshal du Duras, acting as our relation by marriage, later presented my brother and myself to Louis XVI.

BkI:Chap3:Sec2

I was destined for the Royal Navy: disdain for the court was natural to all Bretons, and particularly my father. The aristocracy of our States reinforced the sentiment in him.

When I was brought back to Saint-Malo, my father was at Combourg, my brother at the College of Saint-Brieuc; my four sisters were living with my mother.

All the latter’s affections were concentrated on her eldest son; not that she failed to cherish her other children, but she showed a blind preference to the young Comte de Combourg. It is true that as a boy, as a late-comer, as the Chevalier (so I was called), I had certain privileges compared to my sisters; but ultimately I was left in the hands of servants. Moreover my mother, full of wit and virtue, was preoccupied with the cares of society and the duties of religion. The Comtesse de Plouër, my godmother, was her intimate friend; she also knew Maupertuis’ parents, and those of the Abbé Trublet. She loved politics; noise; the world: for one played politics at Saint-Malo as do the monks of Saba in the Ravine of Cedron; she threw herself into the La Chalotais affair with ardour. She brought to her household a tendency to scold, a distracted imagination, a parsimonious spirit, which at first prevented us recognising her admirable qualities. Orderly herself, her children ran wild; though generous she gave an impression of avarice; a gentle soul she was always scolding; my father was the terror of the servants, my mother the scourge.

The first sentiments of my life arose from these characteristics of my parents. I was attached to the woman who cared for me, an excellent creature called La Villeneuve, whose name I write with a feeling of gratitude and tears in my eyes. La Villeneuve was a kind of superior nurse to the household, carrying me in her arms, secretly giving me anything she could find, wiping away my tears, kissing me, dropping me in a corner, picking me up again and muttering all the time: ‘This one won’t be proud! He’s good-hearted! He’s not hard on poor folk! Here, little fellow,’ and she would fill me with wine and sugar.

My childish affection for La Villeneuve was soon eclipsed by a worthier friendship.

BkI:Chap3:Sec3

Lucile, the fourth of my sisters, was two years older than me. A neglected younger daughter, her clothes were simply her sisters’ cast-offs. Imagine a thin, little girl, too tall for her age, with gangling arms, a timid air, speaking with difficulty, and unable to learn a thing: give her a borrowed dress of a different size than her own; enclose her chest in a bony bodice whose points chafed her sides; support her neck with an iron collar trimmed with brown velvet; coil her hair on the top of her head, and hold it there with a toque of some black material; and you behold the wretched creature who struck my sight on returning to the paternal roof. No one would have suspected in this pitiful Lucile the talents and beauty that would one day illuminate her.

She was handed over to me like a toy; I did not abuse my power; instead of submitting her to my will, I became her defender. Every morning I was taken with her to the house of the Couppart sisters; two old hunchbacks dressed in black, who taught children to read. Lucile read very badly; I read even worse. They scolded her; I scratched the sisters; serious complaint was made to my mother. I began to pass as a good-for-nothing, a rebel, an idler, ultimately a donkey. These ideas became entrenched in my parents’ minds: my father would say that all the Chevaliers de Chateaubriand had chased hares, were drunkards and brawlers. My mother sighed and grumbled on seeing the state of my jacket. Child though I was, my father’s words made me bridle; when my mother crowned her remonstrance with a eulogy of my brother whom she called a Cato, a hero, I felt disposed to commit every wickedness that seemed expected of me.

My writing-master, Monsieur Després, with a sailor’s wig, was no more satisfied with me than my parents were; he made me copy eternally, following a sample in his style, these two lines of verse that I held in horror, not through any fault in the language displayed:

It is you, my spirit, to whom I wish to speak:

You possess those failings which I cannot conceal.

He accompanied these reprimands with blows from his fist which he landed on my neck, calling me a dizzard-head; did he mean dizzy? I don’t know what a dizzard-head is, but I take it to be something horrible.

BkI:Chap3:Sec4

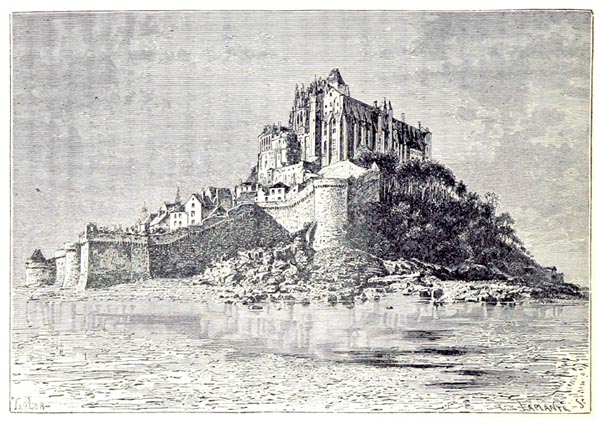

Saint-Malo is nothing but a rock. Once rising from the midst of a marsh, it became an island by the invasion of the sea, which, in 709, hollowed out the bay and set Mont Saint-Michel in the midst of the waves.

‘Le Mont Sain-Michel’

La France Pittoresque. Ouvrage Illustré - Jules Gourdault (p64, 1893)

The British Library

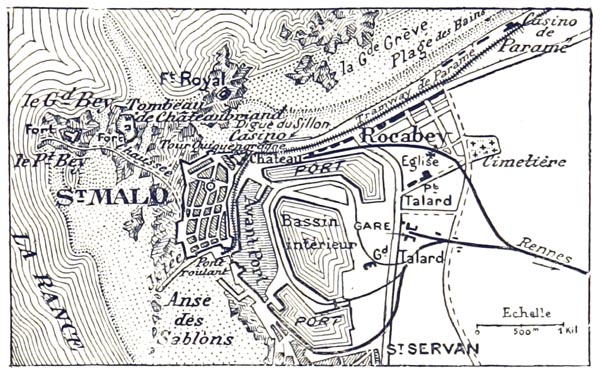

Today, the rock of Saint-Malo is only connected to the mainland by a causeway called poetically Le Sillon (the Furrow). The Sillon is attacked on one side by the open sea: the other is washed by the tide which swings round it to enter the port. A storm almost destroyed it completely in 1730. During the hours of low tide the harbour is dry, and on the northern and eastern margins of the sea a beach of the finest sand is revealed. One can then make a tour around my paternal nest. Near and far are scattered rocks, forts, uninhabited islets: Fort-Royal, La Conchée, Cézembre, and Le Grand-Bé where my tomb will be; without knowing I chose well: be, in Breton, signifies a tomb.

At the end of the Sillon, set with a calvary, you find a mound of sand at the edge of the open sea. This mound is called La Hoguette; it is topped by an old gibbet: the uprights served for our games of puss in the corner; we disputed possession with the sea-birds. But it was not without a certain terror that we lingered in this spot.

There, the Miels are to be found also, dunes where sheep grazed; to the right are the meadows at the foot of Paramé, the post-road to Saint-Servan, the new cemetery, a calvary, and windmills on hillocks, like those which stand on Achilles’ grave at the entrance to the Hellespont.

‘Plan de la Ville de Saint-Malo’

Zig-Zags en Bretagne, etc. Illustré - H. Dubouchet (p21, 1894)

The British Library

Book I: Chapter 4: Life of my maternal grandmother and her sister at Plancouët – My uncle the Comte de Bedée, at Monchoix – Release from my nurse’s vow

BkI:Chap4:Sec1

I reached my seventh year; my mother took me to Plancoët, in order to be released from my wet nurse’s vow; we stayed with my grandmother. If I have ever known happiness, it was certainly in that house.

My grandmother occupied, in the Rue du Hameau de L’Abbaye, a house whose gardens descended in terraces to a valley, at the bottom of which was a spring surrounded by willows. Madame de Bedée could no longer walk, but apart from that she had none of the disabilities of her age: she was a charming old lady, plump, white, neat, distinguished in appearance, with fine aristocratic manners, wearing old-fashioned pleated dresses and a black lace cap tied under the chin. Her wit was mannered, her conversation grave, her temperament serious. She was cared for by her sister, Mademoiselle de Boisteilleul, who resembled her only in her kindness. The latter was a thin little creature, playful, talkative and full of raillery. She had loved a certain Comte de Trémigon, who had vowed to marry her, but had then broken his promise. My aunt consoled herself by celebrating her love, for she was a poet. I often remember hearing her singing in a nasal voice, spectacles perched on her nose, while she embroidered double-cuffs for her sister, an apologia that began thus:

A sparrow-hawk loved a warbler

And, so they say, was loved by her.

which always seemed a strange thing to me for a sparrow-hawk to do. The song ended with the refrain:

Ah! Trémigon, is the tale obscure?

Toora-loora.

How many things in this world end like my aunt’s love-affair in toora-loora!

My grandmother trusted her sister with the running of the house. She dined at eleven in the morning, followed by her siesta; she woke at one; she was carried down the garden-terraces to the willows by the spring, where she knitted, surrounded by her sister, her children, and her grand-children. In those days old age was a dignity; today it is a burden. At four, she was carried back to the drawing-room; Pierre, the servant, set out a card-table; Mademoiselle de Boisteilleul rapped on the fire-back with the tongs and, a few moments later, three more old ladies appeared who came from the neighbouring house at my great-aunt’s summons. These three sisters were the Desmoiselles Vildéneux; daughters of an impoverished gentleman, who instead of dividing their meagre inheritance enjoyed it in common, had never separated and never left their native village. Close to my grandmother since childhood, they lived next door and came every day at the agreed signal, sounded out on the fire-back, to play quadrille with their friend. The game began; the good ladies quarrelled: it was the only event in their lives, the only time when the equanimity of their tempers altered. At eight, supper restored their serenity. Often my uncle De Bedée, with his son and three daughters, joined the old lady’s supper. The latter told a thousand stories of the old days; my uncle, in turn, recounted the Battle of Fontenoy, in which he had taken part, and crowned his boasting with somewhat frank anecdotes which made the good ladies faint with laughter. At nine, with supper over, the servants entered; everybody knelt, and Mademoiselle de Boisteilleul said prayers aloud. At ten the whole house was asleep, except my grandmother, who was read to by her maid until one in the morning.

That society, the first I took note of in my life, is also the first that vanished from my eyes. I saw death enter that house of blessing and peace, render it more and more solitary, closing one door and then another which opened no longer. I saw my grandmother forced to renounce her quadrille, lacking her customary partners; I saw the number of her loyal friends diminish, until the day when she fell, the last. She and her sister had promised to summon each other if the one arrived before the other; they had kept their word and Madame de Bedée only survived Mademoiselle de Boisteilleul by a month. I am probably the only person in the world who knows that those people existed. Twenty times, since that day, I have made the same comment; twenty times social groups have formed around me and dissolved. The impossibility of continuance and duration in human relationships, the profound oblivion that follows us, the unconquerable silence that shrouds our grave and extends from there to cover our house, continually reminds me of the need for solitude. Any hand will do to gift us the glass of water that we may want in our death-fever. Ah! May it not be one too dear to us! For how shall we abandon without despair the hand that we have covered with kisses and that we would hold to our heart for eternity?

BkI:Chap4:Sec2

The Comte de Bedée’s chateau was situated a league from Plancoët, in a pleasant elevated position. Everything there breathed joy; my uncle’s good humour was inexhaustible. He had three daughters, Caroline, Marie and Flore, and a son, the Comte de la Bouëtardais, a councillor in the High Court, who all shared his lightness of heart. Monchoix was full of cousins from the neighbourhood; there was music, dancing, hunting, merrymaking from morning to night. My aunt, Madame de Bedée, seeing my uncle cheerfully consuming his capital and revenue, quite reasonably grew angry with him; but nobody listened, and her bad humour increased the family’s good humour; particularly as my aunt was herself subject to a host of fads: she always had a large fierce hunting dog cradled in her lap, and a tame boar following her that filled the château with its grunts. When I came to this house of festivity and noise from my father’s house, so sombre and silent, I found myself in a veritable paradise. The contrast became more striking once my family were settled in the country: to travel from Combourg to Monchoix, was to travel from the desert into the world, from the keep of a medieval baron to the villa of a Roman prince.

On Ascension Day 1775, I left my grandmother’s house, with my mother, my great-aunt De Boisteilleul, my uncle De Bedée and his children, my nurse and my foster-brother, for Notre-Dame de Nazareth. I was wearing a long white robe, white shoes, gloves and hat, and a blue silk sash. We reached the Abbey at ten in the morning. The monastery, sited by the roadside, was dated by a quincunx of elms from the time of Jean V of Brittany. The cemetery was entered through the quincunx: a Christian could not reach the church except by traversing this region of tombstones: it is through death that we arrive in God’s presence.

The monks were already in their stalls; the altar was illuminated by a host of candles; lamps hung from the various arches: in Gothic buildings there are perspectives and, so to speak, successive horizons. The beadles came to meet me, ceremoniously, at the door, and conducted me to the choir. Three chairs had been set out: I took my place on the middle one; my nurse sat on my left; my foster-brother on my right.

The mass commenced: at the offertory the priest turned towards me and read out certain prayers; after which my white clothes were removed, and hung as an ex-voto beneath an image of the Virgin. I was then dressed in a purple habit. The prior delivered a discourse on the efficacy of vows; he recalled the tale of that Baron de Chateaubriand who travelled to the East with Saint Louis; he told me that I might also perhaps visit, in Palestine, that Virgin of Nazareth to whom I owed my life through the intercession of the prayers of the poor, always effective before God. This monk, who recounted to me the history of my family, as Dante’s grandfather told him the history of his ancestors, could, like Caggiaguida, have also added a prophecy of my exile.

Tu proverai sì comme sa di sale

Lo pane altrui, e com’ è duro calle

Lo scendere e il salir per l’atrui scale.

E quel che più ti graverà le spalle,

Sarà la compagnia malvagia e scempia,

Con la qual tu cadrai in questa valle:

Che tutta ingrata, tutta matta ed empia

Si farà contra a te; ..........

................

Di sua bestialitate il suo processo

Farà la prova: sì che a te fia bello

L’averti fatta parte per te stesso.

You’ll prove how salt the taste, there

Of another’s bread, how hard the path

To climb and to descend another’s stair.

And what will most weigh on your back

Will be that company, vicious and bad,

With which you’ll fall into that crack,

For all of them ungrateful, impious, mad

Will be against you;........

.................

Their careers will prove their brutishness

So that it will be a worthy thing for you

To have made a party of one of yourself.

After the Benedictine’s exhortation, I always dreamt of the pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and in the end I accomplished it.

I have been dedicated to religion; the garments of my innocence have rested on its altars: it is not my clothing that should be hung there today, in its temples, but my sufferings.

BkI:Chap4:Sec3

I was brought back to Saint-Malo. Saint-Malo is not the Aleth of the Notitia Imperii: Aleth was more likely sited by the Romans in the suburb of Saint-Servan, in the naval harbour called Solidor, at the mouth of the Rance. Opposite Aleth was a rock, est in conspectus Tenedos (‘Tenedos is in sight’), not the refuge of perfidious Greeks, but the retreat of the hermit Aaron, who in 507 made his home on the island; it is the date of Clovis’ victory over Alaric; one founded a little hermitage, the other a great empire, monuments equally vanished.

Malo, in Latin Maclovius, Macutus, Machutes, having become Bishop of Aleth in 541, drawn there as he was by the celebrated Aaron visited him. Chaplain of that hermit’s oratory, after the death of the saint, he built a monastic church, in proedio Machutis (on land belonging to Machutis). The name Malo was transferred to the island, and afterwards to the town Maclovium, Maclopolis.

From Saint-Malo, first Bishop of Aleth, to Saint Jean surnamed de la Grille, appointed in 1140, who built the cathedral, there were forty-five bishops. Aleth having been almost completely destroyed in 1172, Jean de la Grille transferred the Episcopal See of the Roman town to the Breton town which developed on Aaron’s rock.

Saint-Malo had to endure great suffering during the wars that arose between the French and English kings.

The Earl of Richmond, later Henry VII of England, with whom the Wars of the Roses ended, was conveyed to Saint-Malo. Betrayed by the Duke of Brittany to Richard III’s ambassadors, the latter prepared to take him to London for execution. Escaping from his guards, he took refuge in the Cathedral, Asylum quod in eâ urbe est inviolatissimum (a place of inviolable refuge in that city): this right of asylum, Minihi (Breton for ‘sacrosanct’) derived from the Druids, the first priests of Aaron’s isle.

A Bishop of Saint-Malo was one of the three favourites (the other two were Arthur de Montauban and Jean Hingaut) who ruined the unfortunate Gilles de Bretagne: this one can read in the Histoire lamentable de Gilles, seigneur de Chateaubriand et de Chantocé, prince du sang de France et de Bretagne, étranglé en prison par les ministres du favori, le 24 avril 1450.

BkI:Chap4:Sec4

There was a handsome mutual capitulation between Henri IV and Saint-Malo: the town negotiated with strength from a position of strength, protected those who were refugees within its walls, and achieved the right, by an ordinance of Philibert de la Guiche, Grand-Master of the French artillery, to cast a hundred pieces of cannon. Nowhere resembled Venice (full of light and the arts) more than that little Republic of Saint-Malo: in religion, wealth and maritime chivalry. It supported Charles Quint’s expedition to Africa and assisted Louis XIII at La Rochelle. It flew its flag over every sea, maintaining relations with Mocha, Surat, and Pondicherry, and a company born of its womb explored the Southern Sea.

From the reign of Henri IV my native town distinguished itself by its devotion and loyalty to France. The English bombarded it in 1693; they assaulted it with their ‘infernal device’ (a massive fire-ship) on the 29th November of that year, and I have often played with my friends among the debris created by that assault. They bombarded it again in 1758.

The inhabitants of Saint-Malo lent a considerable sum to Louis XIV during the war of 1701: in recognition of that service, he confirmed their right to defend themselves; he required the crew of the flagship of the Royal Navy to be made up exclusively of sailors from Saint-Malo and its environs.

In 1771, the inhabitants of Saint-Malo repeated their sacrifice and lent thirty millions to Louis XV. The famous Admiral Anson swooped on Cancale, in 1758, and burnt Saint-Servan. In the Château of Saint-Malo, La Chalotais wrote on linen, with a toothpick, in water and soot, the memoirs which made so much noise and that no-one remembers. Events wipe out events; inscriptions engraved over previous inscriptions, they are pages in the history of palimpsests.

BkI:Chap4:Sec5

Saint-Malo furnished the best sailors in our navy; their role in general can be seen in the folio volume, published in 1682, under the title: Rôle général des officiers, mariniers et matelots de Saint-Malo. There was a Coutume de Saint-Malo, printed as part of the collection of the Coutumier Général. The archives of the town are rich in charts useful in mapping maritime history and rights.

Saint-Malo is the native town of Jacques Cartier, France’s Christopher Colombus, who discovered Canada. The inhabitants of Saint-Malo have also left their name at the other end of America in the islands that bear their name: the Malouine Islands.

Saint-Malo is the birthplace of Duguay-Trouin, one of the greatest seamen who has ever lived; and in our own time has given France Surcouf. The celebrated Mahé de la Bourdonnais, Governor of Île-de-France, was born at Saint-Malo, as were La Mettrie, Maupertuis, and the Abbé Trublet, whom Voltaire mocked: that’s not too bad for an enclosure smaller than the Tuileries’ garden.

The Abbé de Lamennais has left far in his wake these little literary notices of my native place. Broussais equally was born at Saint-Malo, like my noble friend, the Comte de La Ferronays.

Finally, in order to omit nothing, I recall the mastiffs that form the garrison of Saint-Malo: they are descended from those famous dogs, regimental mascots among the Gauls, which, according to Strabo, fought in battles against the Romans alongside their masters. Albertus Magnus, monk of the order of Saint Dominic, an author as weighty as Greek geography, declared that at Saint-Malo ‘the protection of so important a place is entrusted each night to the loyalty of certain mastiffs which perform a thorough and secure patrol.’ They were condemned to capital punishment for having had the misfortune to savage a gentleman’s legs, inconsiderately; an incident that gave rise in our day to the song: Bon voyage. They are all treated with callousness. The criminals are poisoned; one of them refuses to take the food from the hands of its weeping owner; the noble animal allows itself to die of hunger: the dogs, like the men, are punished for their faithfulness. Moreover the Capitol was, like my Delos, guarded by dogs, which avoided barking when Scipio Africanus went to his morning prayers.

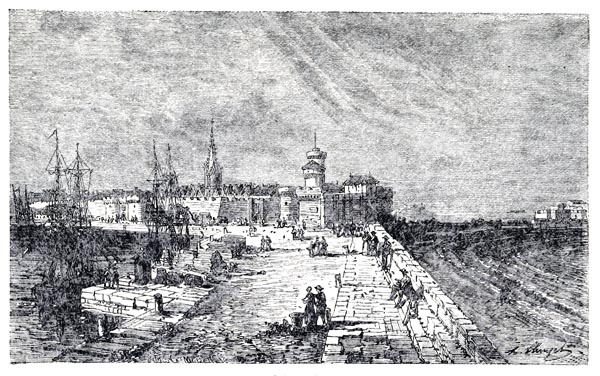

Encircled by walls of various ages, classed as the great and small, and on which the people stroll, Saint-Malo is still defended by the château of which I spoke, and to which the Duchesse Anne added towers, bastions and moats. Seen from without, the island city resembles a granite citadel.

BkI:Chap4:Sec6

Children gather on the shore of the open sea, between the château and Fort Royal; it is there that I have been a pupil, companion of the waves and winds. One of the first pleasures I tasted was to contend with the storms, to play with the breakers that retreated before me, or ran after me along the beach. Another game was to make monuments out of sand which my friends called fours (cakes). Since that time, I have often seen castles built for eternity that have collapsed more swiftly than my palaces of sand.

‘Saint-Malo’

De Cherbourg à Brest sur Mer et sur Terre...Illustré, etc - Marius Bernard (p175, 1887)

The British Library

My fate having been decided irrevocably, I was abandoned to an idle childhood. A few notions of drawing, the English language, hydrography and mathematics, seemed more than adequate an education for a little boy destined in advance for the rough life of a sailor.

I grew up at home, without any course of study; we no longer lived in the house where I was born: my mother occupied a large house, in the Place Saint-Vincent, almost opposite the town-gate that lead to the Sillon. The young urchins of the town had become my dearest friends: I filled the stairs and courtyard of the house with them. I resembled them in every respect; I spoke their language; I shared their manners and looks; I was dressed like them, unbuttoned and untidy like them; my shirts were in rags; I had not a single pair of stockings that was not mostly holes; I trailed around in shabby down-at-heel shoes, that slipped off at every step I took; I often lost my cap, and sometimes my jacket. My face was dirty, bruised and scratched, my hands blackened. My appearance was so strange, that my mother, in the midst of her anger, couldn’t help laughing and crying out: ‘How ugly he is!’

Yet I loved and have always loved tidiness, even elegance. At night I tried to mend my tatters; the maid Villeneuve and my Lucile helped me repair my clothes, in order to spare me scolding and punishment; but their patches only served to render my apparel more bizarre. I was especially saddened when I appeared in rags among the other children, proud of their new clothes and their elegance.

My comrades had a foreign air that smacked of Spain. The Saint-Malo families originated in Cadiz; families from Cadiz took up residence in Saint-Malo. The island site, the streets, the architecture, the houses, the water-tanks, the granite walls of Saint-Malo, gave it a look resembling Cadiz: when I saw the latter town, I was reminded of the former.

BkI:Chap4:Sec7

Locked up at night in their city by the one key, the inhabitants of Saint-Malo made up a single family. Their manners were so innocent that young women who sent for ribbons and veils from Paris were regarded as worldly creatures whose scandalised companions kept apart from them. A marital weakness was a thing unheard of: a certain Comtesse d’Abbeville having been touched by suspicion, it resulted in a plaintive ballad that was sung while crossing oneself. However the poet, faithful, despite himself, to the troubadour tradition, sided against the husband whom he called a barbarous monster.

On certain days during the year, the inhabitants of the town and the countryside gathered at fairs called assemblies, held on the islands and in the forts around Saint-Malo: they went to them on foot at low tide, in boats when the tide was high. The host of sailors and peasants; the covered wagons; the caravans of horses, donkeys and mules; the competition between stall-keepers; the tents pitched on the shore; the processions of monks and fraternities winding their way along with their banners and crosses in the midst of the crowd; the boats coming and going driven by oar or sail; the vessels entering harbour, or anchoring in the roads; the artillery salvos, the peals of bells, all combined to bring sound, movement and variety to these gatherings.

I was the only witness to these fairs who did not share in the joy. I appeared there without any money to buy toys or cakes. Evading the scorn that attaches to ill-luck, I sat far from the crowd, by those pools of water that the sea supports and renews in the hollows of the rocks. There, I amused myself watching the puffins and gulls, gazing into the bluish distance, collecting shells, and listening to the waves murmuring on the reefs. I was not much happier at home in the evening; I had a fierce dislike for certain dishes: I was forced to eat them. I used to look imploringly at La France, who removed my plate adroitly when my father turned his head. Regarding warmth, there was the same severity: I was not permitted to approach the fireplace. It is a long way from those strict parents to the child-spoilers of today.

BkI:Chap4:Sec8

But if I had sorrows that are unknown to childhood these days, I also had pleasures of which it is ignorant.

No one knows any longer what a sense of joy those solemnities of religion and family, or the whole nation and the God of that nation, possessed: Christmas, New Year, Twelfth Night, Easter, Whitsun, Midsummer Day were days of riches to me. Perhaps the influence of my native rock had worked on my feelings and my interests. In the year 1015, the inhabitants of Saint-Malo had vowed to go and help with their hands and their funds in the building of the towers of Chartres Cathedral: have I not also worked with my hands to raise again the fallen spire of the ancient Christian basilica? ‘The sun,’ said Father Maunoir, ‘has never illuminated any region where a more constant and unwavering loyalty to the true faith has been revealed, than Brittany. For thirteen centuries not one infidelity has tarnished the language that has served as a mouthpiece to preach Jesus-Christ, and he is yet to be born who has witnessed a Breton-speaking Breton preach other than the Catholic religion.’

On the feast days that I am about to recall, I was taken on a pilgrimage with my sisters to the various shrines of the town, to the chapel of Saint-Aaron, to the convent of La Victoire; my ears were struck by the sweet voices of unseen women: the harmonies of their canticles mingled with the roar of the waves. When, in winter, at the hour of evening service, the cathedral filled with people; when old sailors on their knees, young women and children with little candles read from their prayer-books; when the congregation at the moment of benediction recited the Tantum Ergo in unison, when, in the interval between songs, the Christmas squalls beat at the basilica’s stained-glass windows, shaking the vaults of that nave which the lungs of Jacques Cartier and Duguay-Trouin had caused to echo, I experienced a deeply religious feeling. Villeneuve had no need to tell me to fold my hands, to call on God by all the names my mother had taught me; I saw the heavens opening, the angels offering up our incense and our prayers; I bent my head: it was not yet charged with those cares that weigh on us so heavily that one is tempted never to raise one’s brow again, once one has bowed it at the foot of the altar.

A sailor leaving these ceremonies, would go on board strengthened against the night, while another was entering port guided by the illuminated dome of the church: so that religion and danger were continually present, and their aspects presented themselves inseparably to my thoughts. I was scarcely born before I heard talk of death: in the evening, a man would go through the streets ringing a bell, calling the Christians to pray for one of their deceased brethren. Nearly every year, boats sank in front of my eyes, and while I was playing along the shore, the sea carried the corpses of foreign sailors, drowned far from their home, to my feet. Madame de Chateaubriand would say to me, as Saint Monica said to her son: Nihil longe est a Deo: ‘Nothing is far from God’. My education had been entrusted to Providence: it did not spare me its lessons.

Dedicated to the Virgin, I came to know and loved my protectress, whom I confused with my guardian angel: her image, which had cost the good Villeneuve a half-sou, was attached with four nails to the head of my bed. I should have lived in the days when people said to Mary: ‘Sweet Lady of heaven and earth, mother of mercy, source of every virtue, who bore Jesus Christ in your precious womb, most sweet and beautiful Lady, I thank you and implore you.’

The first thing I learnt by heart was a sailor’s hymn, beginning:

I place my confidence,

Virgin, in your aid;

Grant me your defence,

With care, protect my days;

And when that final breath

Shall complete my fate,

Grant me holiest death,

In which to steal away.

I have since heard that hymn sung in a shipwreck. Even today I still repeat those humble rhymes with as much pleasure as Homer’s verse; a Madonna graced with a Gothic crown, clothed in a robe of blue silk, bordered by a silver fringe, inspires greater devotion in me than a Raphael Virgin.

If only that peaceful Star of the Seas had been able to calm my life’s disturbances! But I was to be troubled, even in childhood; like the Arab’s date tree, my trunk had scarcely sprung from the rock before it was battered by the wind.

Book I: Chapter 5: Gesril – Hervine Magon – The fight with the two ship’s boys

La Vallée-aux-Loups, June 1812.

BkI:Chap5:Sec1

I have said how my precocious rebellion against Lucile’s mistresses engendered my evil reputation; a playmate completed it.

My uncle, Monsieur de Chateaubriand du Plessis, who lived at Saint-Malo like his brother, had, like him, four daughters and two sons. Of my two cousins (Pierre and Armand) who formed my first ‘society’, Pierre became a page to the Queen, while Armand was sent to college as one destined for the religious state. Pierre, ceasing to be a page, entered the Navy and was drowned off the coast of Africa. Armand, immured in his college for years, left France in 1790, served throughout the Emigration, made a score of intrepid journeys to the coast of Brittany in a longboat, and at last came to die for the King on the Plain of Grenelle, on Good Friday 1809, as I have already said, and as I will mention again when I come to tell of his downfall.

Deprived of the society of my two cousins, I replaced it with a new friendship.

On the second floor of the hotel where we lived, a gentleman of the name of Gesril was staying: he had a son and two daughters. The son was brought up differently from me; a spoilt child, whatever he did was considered charming: he loved nothing more than fighting, and above all stirring up quarrels of which he established himself as the arbitrator. Playing naughty tricks on the maids taking children for their walks there was scarcely talk of anything else but his escapades, transformed into the darkest of crimes. His father laughed at it all, and Joson, was only loved the more. Gesril became my close friend and gained an incredible ascendancy over me: I benefited from such a leader, though my character was entirely the opposite of his own. I loved solitary games, and never sought quarrels with anyone: Gesril was wild for the delights of the crowd, and exulted in the midst of brawling children. When some urchin spoke to me, Gesril would say to me: ‘You allow that?’ At this I imagined my honour was compromised and I would fly in the face of the impudent lad; his height and age were of no consequence. A spectator of the fight, my friend would applaud my courage, but did nothing to help me. Sometimes he raised an army from all the lads he met, divided his conscripts into two gangs, and we skirmished on the shore with stones.

Another game, invented by Gesril, appeared still more dangerous: when the tide was high and stormy, the waves, whipped up at the foot of the château above the main beach, reached the openings in the towers. Twenty feet above the base of one of these towers, a granite parapet held sway, narrow, slippery, sloping, by which one reached the outworks that defended the moat: it was necessary to seize the moment between two breakers to cross the perilous gap, before the wave broke and covered the tower. A mountain of water arrived with an advancing roar which, if you hesitated a moment, could carry you off or crush you against the wall. Not one of us refused the challenge, but I have seen children turn pale before the attempt.

This tendency to push others into adventures, of which he remained a spectator, might lead one to think that Gesril would not reveal a very generous character in later life: nevertheless it was he, who on a much smaller stage, possibly surpassed Regulus in heroism: he only lacked Rome and Titus Livy to ensure his fame. Having become a naval officer he was captured in the Quiberon landing; the action having finished and the English continuing to bombard the Republican army, Gesril threw himself into the sea, swam to the ships, called to the English to cease fire, and told them of the sad state of the émigrés, and their surrender. They wanted to save him, throwing him a rope, and urging him to climb aboard: ‘I am a prisoner on parole,’ he shouted from the midst of the waves, and he swam back to land: he was shot with Sombreuil and his companions.

BkI:Chap5:Sec2

Gesril was my first friend; both of us misjudged in our childhood, we were allied by an instinct of what we might become one day.

Two adventures brought an end to this first part of my story, and produced a significant change in the manner of my education.

We were on the beach one Sunday, beyond the Porte Saint-Thomas, as the tide rose. At the foot of the chateau and along Le Sillon, large stakes driven into the sand protected the walls against the swell. We used to scramble on top of these stakes to see the first undulations of the flow pas beneath us. The places were occupied as usual; there were several little girls among the boys. I was the farthest lad out to sea, having no one in front of me but a pretty little thing called Hervine Magon, who was laughing with pleasure and crying with fear. Gesril was at the other end near the shore. The wave arrived, the wind blew; already the maids and servants were calling out: ‘Come down, Mademoiselle! Come down, Monsieur!’ Gesril waited for a big wave: when it swept in between the piles he gave the child sitting next to him a shove; he fell against another: and he onto the next: the whole line collapsed like a row of cards, but each one was supported by his neighbour; there was only the little girl at the end of the line on whom I leant, and who unsupported by anyone, fell. The ebb swept her away; a host of shrieks ensued, all the maids hitched up their skirts and waded into the sea, each one seizing her charge, and boxing its ears. Hervine was fished out, but declared that François had pushed her in. The maids descended on me; I escaped; I ran home to barricade myself in the cellar: the female army pursued me. Fortunately my mother and father were away. La Villeneuve defended the door valiantly and struck at the enemy’s vanguard. The true originator of the trouble, Gesril, lent his assistance: he climbed to his room, and with his two sisters threw jugs of water and baked apples at the assailants. At nightfall they raised the siege; but the tale went round the town, and the Chevalier de Chateaubriand, aged nine, passed for a desperate character, descended from those pirates whom Saint Aaron had purged from his rock.

This was the other adventure:

I went to Saint-Servan with Gesril, a suburb separated from Saint-Malo by the trading port. To reach it at low tide, you cross the water-course on narrow bridges of flat stones that the rising tide covers. The servants accompanying us had been left far behind us. At the end of one of these bridges we saw two ship’s boys coming towards us; Gesril said: ‘Are we going to let these beggars past?’ and immediately shouted at them: ‘Into the water, you ducks!’ They, in their role of ship’s boys, refused to understand the jest; Gesril retreated; we took up position at the end of the bridge, and snatching up pebbles flung them at the lads’ heads. They descended on us, forcing us to give ground, armed themselves with stones, and drove us back on our reserve corps, that is to say our servants. I was not wounded in the eye, like Horatius: a stone struck me so hard that my left ear, almost detached, hung on my shoulder.

I thought no more of my injury, but only of my return home. When my friend returned from his excursion with a black eye, a torn coat, he was comforted, caressed, coddled, and given a change of clothes: in a similar circumstance, I would be made to do penance. The blow I had received was dangerous, but nothing La France could say would persuade me to go home, I was so afraid I ran and hid on the second floor of Gesril’s house, and he bound up my head in a towel. The towel put him in good spirits: it looked to him like a mitre; he transformed me into a bishop, and made me recite the High Mass with him and his sisters until supper time. The pontiff was then obliged to go downstairs: my heart was beating. Surprised by my appearance, bruised and daubed with blood, my father said not a word; my mother let out a shriek; La France explained my pitiful state, and made excuses for me; I received no less of a dressing down. My ear was patched up, and Monsieur and Madame Chateaubriand resolved to separate me from Gesril as quickly as possible. (I have already spoken of Gesril in my works. One of his sisters, Angélique Gesril de la Trochardais, wrote to me in 1818, asking me to obtain permission for Gesril’s surname to be joined with that of her husband, and her sister’s husband: I failed in my negotiations.)

BkI:Chap5:Sec3

I am not sure if it wasn’t that year that the Comte d’Artois came to Saint-Malo: he was treated to the spectacle of a naval battle. From the heights of the bastion of the powder-magazine, I saw the young prince in the crowd by the sea-shore: in his glory and my obscurity, what unknown workings of destiny! So, unless my memory errs, Saint-Malo has only seen two Kings of France, Charles IX and Charles X.

Such is the picture of my childhood. I do not know if the harsh education I received is good in principle, but it was adopted by my family without design, and as a natural consequence of their temperaments. What is certain is that it made my ideas less like those of other men; what is even more certain is that it marked my sentiments with a melancholy character born in me from the habit of suffering at a tender age, heedlessness and joy.

You might think that this manner of upbringing would lead to my detesting my parents? Not at all; the memory of their strictness is almost dear to me; I prize and honour their great qualities. When my father died, my comrades in the Navarre Regiment witnessed my grief. To my mother I owe the solace of my life, since from her I acquired religion; I listened to the Christian truths that issued from her mouth, as Pierre de Langres would study at night in church, by the light of the lamp burning before the Blessed Sacrament. Would my mind have been better developed by launching me into my studies earlier? I doubt it: those waves, those winds, that solitude, that were my first masters were perhaps better suited to my natural disposition; perhaps I owe to these savage instructors virtues I would have lacked. The truth is that no system of education is in itself preferable to any other: do the children of today love their parents more because they address them as tu, and no longer fear them? Gesril was spoilt in the house where I was scolded: we both became honest men, and affectionate and respectful sons. Something you think bad brings out your child’s talents; something that seems good stifles those same talents. God does well whatever he does; it is Providence that guides us, when it destines us to play a role on the world’s stage.

Book I: Chapter 6: A note from Monsieur Pasquier – Dieppe – A change in my education – Spring in Brittany – Ancient Forest – Pelagian Fields – Moonset over the sea

Dieppe, September 1812.

BkI:Chap6:Sec1

On the 4th September 1812, I received a note from Monsieur Pasquier the Prefect of Police.

‘Office of the Prefect:

Monsieur the Prefect of Police requests Monsieur de Chateaubriand to have the courtesy to visit his office, either today at four in the afternoon, or tomorrow at nine in the morning.’

It was an order for me to leave Paris, that Monsieur the Prefect of Police wished to make known to me. I travelled here to Dieppe, which was first called Bertheville, and was later, now more than four hundred years ago, named Dieppe, from the English word deep (being a safe anchorage). In 1787 I was part of the garrison here with the second battalion of my regiment: to inhabit this town, with its houses of brick, and its shops selling ivory carvings, this town of straight well-lit streets, was to find refuge here along with my youth. When I went for a walk I came across the ruins of the chateau d’Arques, reduced to a host of fragments. One must not forget that Dieppe was Duquesne’s birthplace. When I stayed at home, I had the sea to look at; from the table where I sat, I contemplated that sea which had seen my birth, and that washes the shores of Great Britain where I suffered such a lengthy exile: my gaze passed over the waves that bore me to America, cast me ashore once more in Europe, and again carried me to the shores of Africa and Asia. Here’s to you, Oh Sea, my cradle and my image! I wish to tell you the rest of my story: if I tell a lie, your waves, mingled with my days, will testify to my deceit amongst those men who will live after me.

My mother had never ceased wishing that I be given a classical education. The sailor’s life for which I was destined ‘would not be to my taste’, she said; it seemed wise to her, at any event, to equip me for a different career. Her piety led her to hope that I would decide upon the Church. She therefore proposed to send me to a college where I could learn mathematics, drawing, fencing and English; she did not mention Greek and Latin, for fear of alarming my father; but she counted on them being taught to me, in secret at first, then openly when I had made progress in them. My father agreed to the proposition: it was agreed that I would enter the College of Dol. That town was preferred, because it lay on the route from Saint-Malo to Combourg.

During the intensely cold winter that preceded my scholastic internment, fire consumed the hotel where we were living: I was saved by my elder sister who carried me through the flames. Monsieur de Chateaubriand, having retired to his chateau, called his wife to his side: she was required to join him in the spring.

BkI:Chap6:Sec2

Spring, in Brittany, is milder than in the neighbourhood of Paris, and begins three weeks earlier. The five birds that herald it, the swallow, the oriole, the cuckoo, quail and nightingale, arrive with the breezes that gather in the bays of the Armorican peninsula. The earth is covered with oxeye daisies, pansies, daffodils, narcissi, hyacinths, buttercups, anemones, like the waste ground that surrounds San Giovanni in Laterano and Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, in Rome. The clearings sprinkle themselves with tall, elegant ferns; the stretches of gorse and broom glow with blossom that one takes for golden butterflies. The hedges, their length full of strawberry and raspberry runners, and violets, are decorated with hawthorn, honeysuckle, and brambles with curved brown strands that will bear flowers and magnificent fruit. Everywhere seethes with bees and birds; the swarms and the nests bring children to a halt at every step. In sheltered spots myrtle and oleander interlace over open ground, as in Greece; figs ripen as they do in Provence; and each apple tree, with its carmine flowers, resembles the large bouquet of some village sweetheart.