Boiardo: Orlando Innamorato

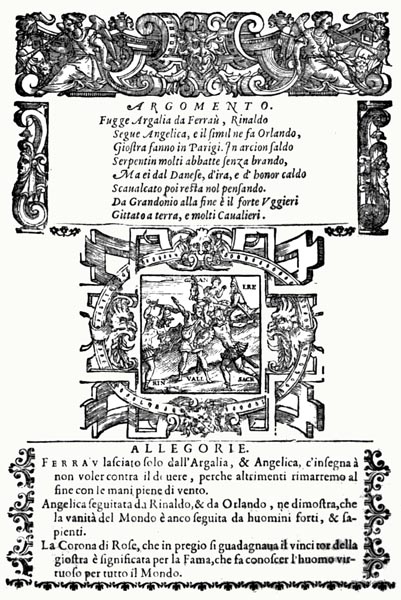

Book I: Canto II: The Tournament

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2022, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book I: Canto II: 1-5: The joust is thwarted

- Book I: Canto II: 6-9: Ferrau seeks Angelica’s hand regardless

- Book I: Canto II: 10-13: She refuses to accept him, and plans to return to Cathay

- Book I: Canto II: 14-16: Angelica vanishes

- Book I: Canto II: 17-20: Astolfo takes Argalia’s lance, and meets Rinaldo

- Book I: Canto II: 21-24: Orlando laments

- Book I: Canto II: 25-28: He too leaves in pursuit of Angelica

- Book I: Canto II: 29-32: Charlemagne’s tournament begins

- Book I: Canto II: 33-36: Serpentino takes the field

- Book I: Canto II: 37-40: He conquers Angelino, Ricardo and Salamone

- Book I: Canto II: 41-44: Then Astolfo, but is unseated by Uggiero, the Dane

- Book I: Canto II: 45-48: Who then defeats Balugante, Isolier, Gualtiero and Spinella

- Book I: Canto II: 49-53: And Matalista, but is downed by Grandonio

- Book I: Canto II: 54-56: Who proceeds to work his way through the Christian knights

- Book I: Canto II: 57-63: Including Oliviero, Marquis of Vienne

- Book I: Canto II: 64-68: Astolfo vows to defeat Grandonio

Book I: Canto II: 1-5: The joust is thwarted

I have told you, my masters, how the fight

Was conducted with a show of arrogance

On the part of Argalia, that proud knight,

And of Ferrau, so powerful with a lance.

The one’s armour was enchanted outright,

The other proof against all circumstance

But a blow to his paunch that plates of steel,

Twenty-thick, went a good way to conceal.

He that has seen a pair of lion battle

For supremacy, and dispute together,

Or heard, overhead, the thunder rattle,

As two storms conflict in fiery weather,

Has seen naught next to these men of mettle,

Who so fiercely attacked one another;

For the heavens seemed on fire, the earth to shake,

As their steel blades clashed, for a woman’s sake.

Every blow but added to their fervour,

While their eyes were fixed in a savage stare.

Each, thinking himself to be the better,

Drenched in sweat, at his enemy did glare.

Argalia now swung hard at the other,

Seeking to strike his head, unhelmed and bare.

And believed, at that point, without a doubt,

That his stroke would suffice to end the bout.

But when he saw that his gleaming blade,

Far from its drawing blood, had been repelled,

He marvelled at the sight, was sore dismayed,

While his hair rose, his confidence dispelled.

At that moment, Ferrau the blow repaid,

Sought to shatter his helm like ice, and yelled:

‘To your Allah, on high, I commend you;

To his paradise this blow will send you!’

And the bold knight accompanied his rant,

With a fierce two-handed swing of his sword.

Had it struck a mountain of adamant,

Twould have sliced it in two, be assured;

Yet not a mark of its passage did it grant;

Enchantment true protection did afford.

I know not what strange thoughts ran through his head,

Uncertain if he were alive or dead.

Book I: Canto II: 6-9: Ferrau seeks Angelica’s hand regardless

But after they’d paused awhile in thought,

Without either seeking to launch a blow,

(Each marvelling at how the other ought

To be dead, and yet was untouched also)

Argalia found tongue, and made retort:

‘Sir knight, I should explain that, head to toe

My armour is enchanted, as you’ve seen,

Or else I’d been slain, as you should have been.

Now you should cease from attacking me,

For all that you will gain is harm and scorn!

Ferrau replied: ‘By Allah, all you see,

Of steel-plate and mail, the shield that’s borne

Upon my arm, I bear from courtesy,

And as adornment, since such things are worn.

Indeed, I need them not, my flesh is charmed,

And, but for the one place, cannot be harmed.

So let me, rather, give you sound advice,

Though you seek it not; I’ll counsel you

To avoid the peril of our fighting twice.

Grant me your sister, without more ado,

That fair flower of the lily, beyond price;

Refuse and you’ll not survive the issue.

If you but grant me her in peace, my brother,

Then shall I be bound to you forever.’

Argalia answered: ‘My bold sir knight,

I might agree to what you’ve thus proposed,

And be willing to strike a pact outright,

And call you brother, for I’m so disposed,

But Angelica must say if such be right,

Or whether to the match she stands opposed.’

Ferrau declared himself content with this;

They might confer together, twas his wish.

Book I: Canto II: 10-13: She refuses to accept him, and plans to return to Cathay

Though Ferrau was young, his complexion

Was dark, he was loud-voiced, and his face

Was forever fearsome, in its expression;

His eyes were red, his eyelids blinked apace,

He cared little for cleanliness of person,

The dirt and dust on his visage a disgrace.

He possessed a pointed skull, and wiry hair

Thick, and as black as charcoal, everywhere.

And so, he little pleased Angelica,

That, ever, liked the handsome and the fair,

Who, when she’d spoken with Argalia,

Said: ‘Brother, to be clear, I do not care

For this; I’d rather drown in the water

Of this fount, or beg for a paltry share

Of what this world may offer, ere I’d wed

That vile savage; I’d rather die instead.

By Allah, I pray you, now, be content

To let me have my way in this matter.

Return, display all your warlike intent,

(Meanwhile, a magic spell I shall further

That will return us to the Orient)

Then disengage, and so follow after –

No steed is swift enough to long pursue;

Midst the wooded Ardennes, I’ll wait for you.

From there, we’ll make our way together

To our dear father’s realm beyond the sea.

Be there within three days, for thereafter,

I’ll be gone, on the wind, speeding swiftly;

For the book of that vile necromancer

Must yield a spell, he who tried to shame me.

If I’ve left, you must travel overland,

Recent knowledge, of that route, you command.’

Book I: Canto II: 14-16: Angelica vanishes

They returned to where Ferrau was waiting,

And Argalia informed the ardent knight

That his sister rejected his wooing,

But Ferrau still demanded that they fight,

For he’d conquer, or die, by so doing.

As they did, the fair one vanished from sight,

A fact the lover realised, instantly,

Since he’d had his eyes on the lovely lady,

For he’d constantly glanced at her face,

It seeming to increase his power always;

And now that she had vanished from the place,

He knew not what to do, or what to say.

Then Argalia turned, and fled apace,

And was soon many a mile on his way,

Spurring towards the meeting-place assigned,

Leaving Ferrau, and the duel, far behind.

The amorous youth now became aware

How he’d been deceived, and ran from the field,

Searching through the woods, here, there, everywhere,

To find where the maid might lie, concealed.

His face seemed ablaze, his eyes to glare,

As he mused on the treachery revealed.

Thus, he ran, and searched on, and stopped for naught,

Though he failed to find the one that he sought.

Book I: Canto II: 17-20: Astolfo takes Argalia’s lance, and meets Rinaldo

Let us turn to Astolfo; that brave knight

Had stayed, alone, by the spring, as you know.

And had gazed on the battle with delight,

As each combatant struggled with his foe.

Now free, his captors dead, or out of sight,

He thanked God for liberty, and made to go,

Not waiting upon chance, as yet unharmed,

And mounted on his courser, fully armed,

Except he lacked a lance, for that weapon

Had been splintered when he had met his fall.

Gazing round, he saw one leaning upon

The pine tree (Argalia’s you’ll recall),

A fine one too, gold laminate thereon,

That enamelled and adorned it overall.

Astolfo seized the thing, without a thought,

Though not knowing by enchantment twas wrought.

He turned away, confident and happy,

As a man is when released from prison;

By the woods met Rinaldo, and briefly,

Told him all that had, there, been seen and done.

Amone’s son was burning so fiercely

With the fires of love, and restless passion,

That he’d ventured forth from the city gate

To learn of Ferrau’s duel, and his fate.

Away, for the Ardennes, Ferrau had ridden,

So, Rinaldo left the English duke behind,

(He of the leopard ensign), and, as bidden,

Baiardo his swift steed (slow to his mind)

Took that same road, though he was well-chidden

By his master, called a mule, and maligned

As lazy (his lord pierced to the marrow

By Love) though far swifter than an arrow.

Book I: Canto II: 21-24: Orlando laments

Let us leave Rinaldo to his passion,

And return to the town with Astolfo,

Where that knight was asked many a question

Discreetly, yet at length, by Orlando,

Seeking news, there, of the competition

And the outcome of the battle, although

He made no mention of his love at all,

Knowing the knight was a babbler withal.

When he learned the news of Angelica,

That she’d vanished, and her brother had fled,

(Rinaldo following on his heels, thereafter)

With a foul look, he headed for his bed,

Where he lay, like one felled by disaster,

Struck down by grief, and to sorrow wed;

For that courageous flower of chivalry

Drowned like some lowly lad, in misery.

‘Alas,’ he said ‘I have no means to counter

This base enemy that strikes at my heart!

Why cannot I wield sharp Durindana;

Fight this Love, split the rogue apart,

That so fills my soul with burning ardour,

Till I feel naught else but his fiery dart?

What torment can match this misery?

I burn with love; I freeze with jealousy!

I know not if that angelic creature

Could deign to love so worthless a person;

Or the garland of contentment, ever,

Crown me as Fortune’s happiest son;

For such he’d be who was but loved by her.

Oh, if Hope abandons me, and she, un-won,

Scorns me, and turns her lovely face away,

I’ll kill myself, and none shall cry me nay.

Book I: Canto II: 25-28: He too leaves in pursuit of Angelica

Oh, misfortune! Should Rinaldo find her

In the Ardennes Forest, his lechery

Is well-known, and the virgin will never

Leave his clutches intact, yet, woe is me,

While they perchance are face to face, ever,

I weep like a little maid, uselessly,

Cheek cradled in my hand, and cry my fears,

Seeking to ease my heart with idle tears.

Perchance I think that solitude can hide

The flame that consumes my heart within?

Yet, I’ll not die of shame; this eventide,

By God, I’ll quit this Paris, and begin

To seek for the maid myself, far and wide.

Summer and winter all this world of sin,

I’ll search, o’er dale and hill, the seas as well,

The heights of Heaven, and the depths of Hell.’

Speaking thus, he raised himself from his bed,

Where he’d lain so long, weeping endlessly.

Waiting for night, while day so slowly sped,

It grieved him, as he paced there, ceaselessly.

A moment seemed a hundred years; his head

Was full of bitter thoughts; then, secretly,

When darkness fell, and shadows covered all,

He went forth, armed, beneath night’s dusky pall.

He took not his quartered shield, but he bore

One whose hue was of dark vermilion;

Yet he rode his valiant Brigliador,

As he cantered to the gate, watched by none;

His departure no squire or servant saw;

And in a moment more the Count was gone,

Sighing deeply, to misery a prey,

As towards the Ardennes he made his way.

Book I: Canto II: 29-32: Charlemagne’s tournament begins

Three great champions, thus, sought adventure.

Rinaldo, and Orlando, and that flower

Of Pagandom, Ferrau, forth did venture;

While Charlemagne thought to fill the hour

With a tourney, splendid beyond measure,

Summoning all the means in his power.

He called for King Salamon, Duke Namus,

Count Gano; all the noble and famous;

And said to them: ‘My lords, it seems to me,

That the jouster who first enters the lists,

Should fight each newcomer, successively,

While the help of Fortune he yet enlists;

If he’s conquered, his challenger shall be

That knight’s replacement while his luck persists,

And so on, till the final loser’s down,

And the last man mounted wins the crown.’

They all approved King Charlemagne’s decree,

And gave praise to this novel invention

Of their master, so wise in chivalry.

The order was proclaimed; he who’d make one,

Should ride in, the next day, for the tourney,

While the king granted martial primacy,

For the joust, to the bold Serpentino;

He’d be the first to encounter a foe.

On the day, the dawn was clear and serene;

The brightest sun there ever was lit the sky.

King Charlemagne was the first to be seen

Unarmoured, but for greaves, cantering by

The lists, on his great charger, o’er the green,

Baton in hand, his sword sheathed; nearby

His counts, barons, knights waited on him,

And catered to his every wish, and whim.

Book I: Canto II: 33-36: Serpentino takes the field

Behold, Serpentino took to the field,

Fully armed, and marvellous to see.

He reined in his charger; the steed revealed

Its fiery nature, rearing powerfully,

Then paced here and there, with unconcealed

Ardour, around the square, rapidly,

Nostrils flaring, as if set to emit,

Fire; flames in its eyes, foam about its bit.

Its bold rider seemed equally daring,

Holding his posture, with a fearful gaze,

Clad in splendid armour, proudly wheeling,

Firm in the saddle, his fierce eyes ablaze.

Women, children, pointed at this princeling,

Whose strength and valour men praised always,

Such that, as he passed before their eyes,

They cried that none but he would gain the prize.

The emblem that he bore upon his shield,

And likewise on his surcoat, and the rest,

Was a great gold star on an azure field,

Which he wore as well on his helmet crest.

That helm, his armour, the arms he did wield,

Were infinitely rich, and of the finest

Tempered steel, that gleamed in the morning light,

All adorned with pearls and gems, shining bright.

Thus, the champion entered the arena,

Passed the barrier, and reined in his steed;

Then, unmoving, like some mighty tower,

Paused, as the trumpets called o’er the mead,

And knights, at each corner, sought to enter,

Each armed more richly; while a few, indeed,

Were more adorned with gems, pearls and gold

Than, perchance, is Paradise, its wealth untold.

Book I: Canto II: 37-40: He conquers Angelino, Ricardo and Salamone

The first contestant, the champion’s first foe,

Bore a silver moon, on a shield of blue,

Twas the lord of Bordeaux, Angelino,

Master of war, and jousts and tourneys too.

He was, at once, charged by Serpentino,

Who attacked, so swiftly he well-nigh flew.

For his part, Angelino came on, briskly,

Lowering his lance, and glaring fiercely.

He thrust the steel tip at Serpentino,

Aiming at the joint twixt helm and shield;

The latter merely crouched to meet the blow,

And struck the visor, that the eyes concealed,

Head over heels went this Angelino,

A cry arose, as if close thunder pealed,

And all roared for the first joust was done,

And he who bore the star that round had won.

Next came Ricardo, a most puissant knight,

That was the ruler of all Normandy;

A golden lion he bore, a noble sight,

On a field of red, and he rode swiftly,

But Serpentino paused not, in full flight,

And met his foe midway, striking fiercely,

While such a mighty blow that lord did land,

That Ricardo’s head slammed into the sand.

How King Balugante rejoiced to see

The valour of his brave son in the field!

Salamone followed, seeking victory;

That wise monarch bore a chequered shield

And a golden crown on his helm, and he

Charged down the list, yet was forced to yield

To Serpentino’s blow; his targe it found,

And felled both horse and rider to the ground.

Book I: Canto II: 41-44: Then Astolfo, but is unseated by Uggiero, the Dane

Astolfo seized his lance, twas the weapon

Argalia left leaning gainst that tree.

His emblem three leopards richly done

In gold on a field gules, mounted firmly,

He yet found mishap, and was soon undone

His steed stumbling, treading unsurely;

For a moment he nigh lost the light of day,

His right foot twisting, as he fell away.

This misfortune much displeased the crowd,

And Serpentino, no doubt, more than most;

He’d thought to triumph, yet now sighed aloud,

At his false prediction; he could hardly boast

Of this duke borne tent-wards, nor feel as proud

As he had formerly, ashamed almost.

Astolfo was quite safe, though not yet sound,

His dislocated ankle set and bound.

Despite Serpentino’s martial skill,

Uggiero the Dane of fear was free.

His swift and eager steed obeyed his will,

As it flew, like a north wind o’er the sea.

A field of azure his great shield did fill,

On it a silver chevron, and proudly

On his helm a basilisk he displayed,

He that to the lists came thus arrayed.

The trumpets sounded. Each lowered his lance,

And the brave pair charged to the encounter.

No bout had been so fierce, no mischance

Marred their meeting, like a clap of thunder

It pealed; Uggiero, in his swift advance,

Tore Serpentino’s saddle from under

That champion and, with its broken girth,

The Knight of the Star promptly fell to earth.

Book I: Canto II: 45-48: Who then defeats Balugante, Isolier, Gualtiero and Spinella

Since mighty Uggiero had won the bout,

Twas his turn to defend the ground he’d won.

King Balugante gave a mighty shout,

And charged, hurt by the fall of his brave son,

But he was flattened, turn and turnabout,

By the Dane, and his involvement was done.

Twas Isolier next engaged to fight,

A powerful, and a most dextrous, knight.

He was Ferrau’s brother; and on his shield

Three golden moons shone on a sea of green.

Lance in hand, he urged his steed o’er the field,

But Uggiero stopped his course, as was seen.

So cruel was the thrust that made him yield,

So pitiless the blow, so fierce, I ween,

That he lay stunned, seven hours and more,

And was seen awhile labouring at death’s door.

Gualtiero of Monleone fell

To Uggiero, as had the three before;

A dragon was his emblem, it did dwell,

Crimson in colour, upon a field or.

‘Let’s not fight amongst ourselves,’ came the yell

From Uggiero, ‘we Christians!’ such his roar:

‘It gives these pagans great cause for laughter,

That we seek to people the hereafter!’

One was Spinella of Altamonte,

Whose gleaming emblem was a golden crown

On a blue field; to show himself worthy

He had come to court; the Dane knocked him down,

Before the king, and his nobility.

Next Matalista, he of some renown,

Fiordispina’s brother, joined the fight,

Lithe in the saddle, and a strong, bold knight.

Book I: Canto II: 49-53: And Matalista, but is downed by Grandonio

His shield was divided, part gold, part black,

While the crest on his helm was a dragon.

He was thrown to the ground, on his back,

While, its saddle empty, his mount ran on.

King Grandonio now rode to the attack;

God help the Dane! Without any question

Twas needed now for, to the furthest corner

Of this Earth, no martial knight was stronger.

The Moor, he was of gigantic stature,

And he rode, fully armed, a mighty steed.

He held a black shield before his armour,

On which was writ a line of golden screed.

No Christian was so foolish ever

As to ignore that mad dog, or his creed.

Gano of Poitiers but viewed his face,

Then departed, silently, from the place.

Macario of Lusan, Pinabel,

And then the Count of Altafoglia

Did likewise, and Falcone left as well,

Each moment there seeming like forever.

Alone of all that treacherous cartel,

Grifone stood firm, disposed to linger

By the gate, held by valour or by shame,

Or thinking the rest would do the same.

Returning to the dreadful Matalista,

That had stirred such a storm as he’d passed by,

His strength was so great he was the bearer

Of a ship’s mast of a lance, I tell no lie;

And his steed was no less fearful either;

It trampled all the sand, and flung it high;

For twould break any stone that lay around,

If the knight let it gallop o’er the ground.

On this Fury, he rode against the Dane,

And struck hard at the centre of his shield,

And split it, while Uggiero felt the pain,

As he fell, stunned, next his steed, on the field.

Duke Namus helped him stand upright again,

And then bore him from the lists to be healed

Of the wounds, to his left arm, and his chest;

A full month, in his bed, now forced to rest.

Book I: Canto II: 54-56: Who proceeds to work his way through the Christian knights

Great, it seems, was the cry that filled the square,

And loudest from the Saracens it rose,

Grandonio, with pride beyond compare,

Issued threats, which had small effect on those

Brave knights still left. Turpin of Rheims, was there.

They met half-way down the course, I suppose,

Each disposed to swiftly end that affair,

Where Turpin left his mount, at such a speed

That he almost saw the face of Death, indeed.

Astolfo, meanwhile, had re-joined the throng,

Cantering up, on a sturdy white palfrey.

Armed with only a sword, he mixed among

The ladies, laughing and chatting calmly,

Solacing himself, as one who had long

Been known for speaking well, and wittily.

But while he was speaking, lo, Grifone

Was thrown to the sand, dismayed wholly;

With him went the emblem of Maganza,

Twas a white falcon on an azure field.

Grandonio, with arrogance, cried louder:

‘O Christians, are you disposed to yield?

Are you weary? Do we joust no longer?’

So, Guy of Burgundy appeared, and wheeled

His steed; a lion, black on gold, he bore,

And was downed, like the others, by the Moor.

Book I: Canto II: 57-63: Including Oliviero, Marquis of Vienne

The powerful Angelieri fell

(His crest a dragon with a woman’s head);

Avino, and Avorio, as well,

Ottone, Belengiero, all wed

Those four, to a chequered shield, so they tell,

Of blue and gold and, to foster dread,

A black eagle, on their helm, did display,

As the Bavarians still do today.

The strength of their fierce foe, Grandonio,

Now seemed but to increase the more he fought;

He slew Alardo, and Ricciardetto,

After Ugo of Marseille, and mocked this court

Of Christian cowards, riding to and fro,

As another knight to conquer, now, he sought,

And, thus, roused to anger King Charlemagne;

Twas then the Marquis Oliviero came

Sallying forth to meet this boastful foe;

And the Christians again raised their eyes;

For King Charlemagne welcomed him below,

While, above, the clouds cleared from the skies,

As every trumpet blared and horn did blow.

The small and the great cheered, loud were their cries:

‘Hail the lord of Vienne, Oliviero!’

Gripping his lance, he smiled, Grandonio.

Each attacked the other, spiritedly;

Their fury was as great as ever seen.

The throng watched in suspense, attentively,

While waiting on the clash of arms between

This mighty pair, the silence uncanny,

So deep that it enveloped all the scene.

Oliviero checked the other’s advance,

Striking home, high on the shield, with his lance.

Nine thick layers of steel had that shield;

Oliviero’s blow pierced them through.

He shattered the breastplate, and so revealed

The flesh beneath, while a clear inch or two

Of his lance-point entered as it did yield.

But Grandonio’s aim was ever true;

He struck Oliviero on the brow,

And flung him seven yards beyond, I vow.

All thought he must be dead, his helm broken,

Cracked in half, indeed, and those that saw

His face swore that there was scarce a token

Of life within, and that he breathed no more.

Oh, Charlemagne’s dismay, what grief unspoken!

At last, in tears, he cried: ‘My son, wherefore

Has God this great and dire misfortune brought

Upon the flower, the honour, of my court?’

Book I: Canto II: 64-68: Astolfo vows to defeat Grandonio

Grandonio had shown his arrogance

Before, now it was insupportable.

He shouted at the knights, and shook his lance:

‘Brave lords of drunkenness, incapable

Of aught but swilling in the inns of France!

More than a cup I wield, unconquerable!

Is this the Round Table’s valiant order,

That one may threaten, and receive naught further!’

Charlemagne, listening to his scornful cry,

Hearing the insults aimed at his great court,

Was troubled in both heart and mind thereby;

With crimson face, with blazing eyes, he sought

A champion: ‘Who will this oaf defy?

Have I no loyal man who’ll make retort?

Where’s Gano of Poitiers, where’s Rinaldo,

Where is that traitorous bastard, Orlando?

Son of a whore! You faithless renegade!

Show your face, and may I fall dead if I

Don’t hang you myself! Thus am I obeyed!’

Charlemagne uttered many a like cry.

Astolfo, listening to that loud tirade,

Silently left the crowd and, by and by,

Having re-equipped himself, reappeared,

As, towards the lists, his mount he steered.

The Frankish lord did not himself believe

That he could conquer the Saracen,

But his firm intention was, I believe,

To do his duty by the king once again.

To his saddle proudly he did cleave,

The very model of a knight I’d maintain,

But all who recognised Astolfo cried:

‘Lord, send another; he can barely ride!’

Astolfo bowed his head most gracefully,

Before King Charlemagne: ‘My Lord,’ he said,

‘I’ll thrust this Moor from his saddle, promptly,

Such I think is your desire, or strike him dead.’

The king, annoyed, replied disdainfully:

‘God help you, then! Be it on your own head.’

And muttered to his knights: ‘I must consent,

Though we scarcely need more embarrassment!’

Astolfo now threatened the pagan knight

With being set to work an oar, at sea;

This left the giant so ready for a fight

That none was ever so enraged as he.

In the very next canto that I write,

You will hear, if the good Lord allows me,

Of great wonders, of adventures stranger

Than you’ve been told of, or read of, ever.

The End of Book I: Canto II of ‘Orlando Innamorato’