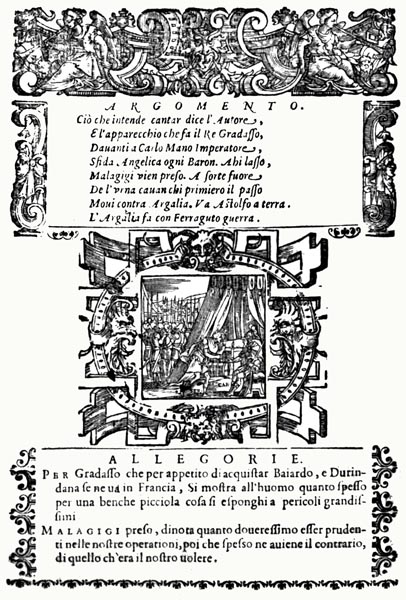

Boiardo: Orlando Innamorato

Book I: Canto I: Angelica at the Court of Charlemagne

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2022, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book I: Canto I: 1-3: Boiardo’s Introduction

- Book I: Canto I: 4-7: King Gradasso sets out to invade France

- Book I: Canto I: 8-12: The Feast of Pentecost at Charlemagne’s court

- Book I: Canto I: 13-18: Rinaldo contemplates his enemies the Maganzese

- Book I: Canto I: 19-22: Angelica appears accompanied by four giants and a knight

- Book I: Canto I: 23-28: She addresses Charlemagne and issues a challenge

- Book I: Canto I: 29-32: Orlando is smitten with love of her

- Book I: Canto I: 33-35: Ferrau and Rinaldo are also smitten

- Book I: Canto I: 36-40: Malagigi discovers the truth of the matter

- Book I: Canto I: 41-44: He quickly overcomes the giants

- Book I: Canto I: 45-50: But is captured by Angelica and Argalia

- Book I: Canto I: 51-53: And whisked away to their land of Cathay

- Book I: Canto I: 54-58: Astolfo is chosen, by lot, as the first to fight Argalia

- Book I: Canto I: 59-67: He is unhorsed and taken prisoner

- Book I: Canto I: 68-73: Ferrau takes up the challenge

- Book I: Canto I: 74-83: He fights the giants

- Book I: Canto I: 84-91: Ferrau provokes Argalia into renewing their duel

Book I: Canto I: 1-3: Boiardo’s Introduction

You gentlemen and knights, assembled here,

To learn of things both delightful and new,

Be still, and pay attention, and give ear

To the fine tale that I’ll now sing for you;

For you’ll hear of great deeds of yesteryear,

Of boundless feats, miraculous but true,

That Orlando, through love, once set in train,

In the days of the Emperor Charlemagne.

Nor should it seem so wonderful to you

To hear a tale of Orlando in love;

Tis ever the proudest man, in my view,

That Love subjugates; no arm will prove

E’er strong enough, no blade, however true,

Nor bravery sufficient, though we move

Heaven and Earth, nor shield, nor coat of mail;

In the end, Love, conquering all, will prevail.

This history’s known to few, for its teller,

Bishop Turpin, concealed the tale from sight.

He may have feared that it might seem other

Than respectful to that most worthy knight,

In that he, when faced with Love, was the loser,

Though he’d conquered all other foes, outright.

Of Orlando, I speak, the brave and true.

Now, to our story, without more ado.

Book I: Canto I: 4-7: King Gradasso sets out to invade France

Thus, in Bishop Turpin’s true history,

We read that there reigned, in the Orient,

Past India, a king rich and mighty,

So powerful, so magnificent

In his great strength, and in his bravery,

He envied none, in all the world’s extent.

Gradasso was the name of this leader,

A serpent at heart, a giant in stature.

Yet, as is oft the case, I would maintain,

Great lords most long for what they do not own,

And the harder the thing is to obtain,

The more they’ll risk their kingdom and their throne.

Not possessing what it is they would attain,

They’d lose all that they have for that alone.

Two things, a sword, a horse, lacked Gradasso,

Durindana, and the steed Baiardo.

He assembled an army, from everywhere

In his vast realm; to war he had recourse,

Knowing that his treasury could not bear

The purchase of the weapon or the horse.

Two knights were the owners of that pair;

‘Merchants’ who’d not yield except to force.

Therefore, he chose to go with sword and lance,

And use his power to capture them, in France.

A hundred and fifty thousand he chose

Of his multitude of knights, but his thought

Was not to employ them to come to blows;

Twas to duel, in single combat, he sought,

Against Charlemagne or any of those

Fine men (and faithful Christians) at his court.

Alone, he would conquer, raze to the ground,

All that the sun views and the seas surround.

Book I: Canto I: 8-12: The Feast of Pentecost at Charlemagne’s court

At present, under sail, let him advance,

Though you’ll hear more about him when they land,

And return to King Charlemagne and France.

A review there, of his folk, he did command,

Every Christian prince, with sword and lance,

Paraded before him, lords of the land,

Every knight; for his will might not be crossed:

To tourney at the Feast of Pentecost.

Every paladin attended at the court,

To celebrate on the appointed day.

From every country, and region, they sought

Fair Paris, in their infinite array.

And many a Saracen, his knights had fought,

Was there, for twas a royal court, they say,

Where any not a renegade or traitor,

Was promised a safe sojourn, as ever.

Thus, many were the folk that came from Spain,

Keeping their noble leaders’ company:

Snake-eyed Grandonio, the Christians’ bane,

And bold Ferrau, a griffin’s gaze had he,

King Balugante, kin to Charlemagne,

And Serpentino his son, of that country,

With Isolier, and many another

Whose deeds, in the joust, I’ll speak of later.

In Paris sounded many an instrument,

Loud drums and trumpets, as the bells rang out.

Their steeds, adorned each in a splendid vestment,

Great chargers, with fine trappings all about,

Wrought with rare gold and gemmed ornament,

Defied description, peerless without doubt;

His knights, striving to please the emperor,

Had done all they could to show him honour.

And now the great day was already here,

On which the tournament was to begin,

Such that to Charlemagne’s table drew near,

All the knights and true barons who had been

Asked to honour his board and, there, appear.

Twas a mighty host sat down to eat within

The pavilions erected for the Feast;

Twenty-two thousand and thirty, at least.

Book I: Canto I: 13-18: Rinaldo contemplates his enemies the Maganzese

King Charlemagne, with a radiant face,

Sat on his golden throne midst his peers,

(At his Round Table, each lord found a place);

Before him the Saracens who, it appears,

Needed no couch or bench for them to grace,

But, spreading fine carpets like true Emirs,

Sat straight as deer-hounds; and, indeed, refused

To endorse the customs the Frenchmen used.

The book says tables to the left and right

Had been set; at the first, in majesty,

Sat three great rulers, kings in their own right,

Of England, Lombardy, and Brittany,

Renowned, throughout Christendom, for their might;

Otho, Desiderio, Salamone;

With other Christian kings, from far and wide,

Ranked according to merit, on each side.

Marquises, dukes occupied the second;

Noble counts and resplendent knights the third.

Maganza’s House there found honour; beyond

All, on Gano of Poitiers twas conferred.

Rinaldo’s eyes blazed, longing to respond

To those proud traitors with an angry word,

For, by that ill clan, he was mocked and scorned,

As appearing less well-dressed and adorned;

Though he offered a smiling face, instead,

Hiding angry feelings deep in his breast,

Saying to himself: ‘Rascals, born and bred,

Tomorrow, in the lists, perchance I’ll test

If to your saddles you are truly wed!

Asinine clan. Accursed race! Oh, rest

Assured, if my heart fails not, you all shall lie

Prone on the earth, and know my lance thereby.’

King Balugante, following his gaze,

And well-nigh divining his inner thought,

Sent his interpreter (with him always)

To ask if honour, in this emperor’s court,

Was best won by wealth or valour, these days.

For he, who was a stranger, ever sought,

(Since Christian ways he’d rarely observed)

To honour every man as he deserved.

Rinaldo laughed, and answered pleasantly,

‘Please report to your king, that if he would

Honour these Christians, then gluttony

At the table, and a woman that’s good

In bed, these win their hearts, most readily;

Yet, as fighting men, be it understood,

When it’s time for knights to show their valour,

Let him then grant each man his due honour!’

Book I: Canto I: 19-22: Angelica appears accompanied by four giants and a knight

While they were conversing in this manner,

The sound of instruments filled all the air;

While, behold, many a golden platter,

Filled with delicacies, that host did share;

While, as gifts, King Charlemagne did offer

Enamelled goblets, wrought with subtle care,

To some lord, to indicate he’d paid heed

To his performance of some noble deed.

The emperor was gazing round, happily,

And indulging in quiet conversation,

Reflecting that his own proud majesty

Was enhanced by the peers of his nation;

While sand in the wind was this company

Of pagans, when, to the consternation

Of all, a new arrival met their sight,

A fair lady, with four giants and a knight.

They appeared at the end of the great hall,

The giants most fearsome, each one vast in height,

While the lady walked calmly, midst them all,

(Escorted by the warrior) shining bright

As does the morning star, born to enthral,

Fair as the rose, or lily gleaming white;

In sum, to speak the truth of her wholly,

Never, on Earth, was there seen such beauty;

Yet, within that place, was Galerana,

And Alda, the wife of Orlando,

And there too Clarice, and Ermelina,

And many another beauty, also,

That I’ll not name: yet none was lovelier,

Though all were fair, and virtuous; and, oh,

I’d say, each seemed the fairest in that hall,

Till she came to steal the prize from them all.

Book I: Canto I: 23-28: She addresses Charlemagne and issues a challenge

Every Christian prince, and every knight,

Turned his gaze in the maiden’s direction.

The Saracens leapt to their feet outright,

And, all amazed, they approached the vision,

Each won by her beauty, stunned by the sight;

While, seeming of happy disposition,

She smiled so as to melt a heart of stone,

And spoke, as follows, in a gentle tone:

‘Magnanimous lord and king, your virtue,

And your noble paladins’ every deed,

(Knights renowned in all lands, as is their due,

On every sea-girt shore that Fame’s decreed)

Leads me to hope the hardship that we two

Poor pilgrims, have undergone, in our need,

Has not been wasted; we, who journeyed here

From the Earth’s ends, to honour your good cheer.

Give me leave, my lord, to outline at least,

In a few brief words, the pressing reason

That has brought us here, to your royal feast.

Oberto dal Leone, here makes one,

Of noble birth, and renowned in the East

For his deeds, yet driven forth, however,

As am I, Angelica, his sister.

Beyond the Don, two hundred days journey,

The news reached our kingdom, on a day,

Of a great gathering here, and a tourney,

With a host of knights in splendid array,

And a crowd of fine folk making merry.

Not cities, gems, or treasure, they do say,

Are the prize for whoe’er best wins renown,

But a rose-garland, borne as is a crown.

And therefore, my brother, here, decided

That he could best reveal his passing skill

Where all of the finest knights abided

And meet them one by one, if they so will.

Baptised or pagan, if you are guided

To perform noble deeds, and would fulfil

Your destiny, then come to Merlin’s Stone,

By Pine Spring; it stands in the field, alone.

Do so, however, upon one condition,

(He who’d prove himself, mark what I say)

That once he’s toppled from his saddle, none

May then seek to resume the fight that day,

But must yield himself to a distant prison.

Yet he that can unhorse Oberto may

Take my person as his prize, for my part;

While my brother, with these giants, will depart.’

Book I: Canto I: 29-32: Orlando is smitten with love of her

As she ended, she fell upon her knees,

At Charlemagne’s feet, to hear his reply.

Every man gazed at her (she did so please),

Orlando most, who drew near, by and by.

The heart within him trembled without cease,

He blushed but hid his longing from her eye,

And while looking, steadfastly, at the ground,

Quite full of shame, one thought within did sound:

‘Oh, mad Orlando,’ to himself, he cried,

‘To be transported, so, with fond desire!

See you not the sin to be e’er denied,

Lest you fail your God, and fall to the fire?

Where is Fortune leading you, that ill guide?

Caught am I, and in Love’s strong net am tied,

I, who held the world as naught; I, a knight,

Am conquered by this maid, without a fight!

I cannot, from this heart of mine, erase

The sweet vision of her most lovely face,

And I shall die without her; in a blaze

Of fire and light, my soul will leave its place.

My strength now fails, my body scarce obeys,

While Love, thus, clasps me tight in his embrace.

Knowing is of no help, and thought a curse:

I see the better, yet I choose the worse.’

In this manner, silently, Orlando

Lamented his new-discovered passion;

Indeed, the old and white-haired Duke Namo

Felt as deep a pang, in his own fashion.

He trembled, stunned and faint, troubled so,

His face was pallid, his colour ashen.

But why say on? The peers all felt the same,

All were on fire, as was King Charlemagne.

Book I: Canto I: 33-35: Ferrau and Rinaldo are also smitten

All stood, unmoving, and quite stupefied,

While gazing at her, with extreme delight;

And Ferrau, most rash it cannot be denied,

Seemed to burn with ardour, for the knight

Thrice started forward, seeking a fair bride

In her, despite the giants he must fight,

Though three times he retreated (if not more)

So as not to annoy the emperor.

He shifted from one foot to the other,

Rubbed his brow, and could scarcely keep still.

Rinaldo too was caught gazing at her;

His face, in shame, flushed crimson, as it will.

But wise Malagigi had her measure,

For he whispered, softly: ‘You’ll have your fill

Of me, ere I’m done, you vile enchantress,

And wish you’d spared our court your bold address.’

King Charlemagne, in a lengthy reply,

Offered his answer to the lovely maid.

Seeking to keep so fair a lady by,

He gazed; spoke; spoke and gazed, with much delay,

While naught that she did seek could he deny.

Her demands he would meet that very day,

And swore on the Book that it would be so.

She left; her brother and the giants also.

Book I: Canto I: 36-40: Malagigi discovers the truth of the matter

They had not issued far from the city,

When Malagigi sought a magic spell,

Took up his book to unveil all swiftly,

And summoned up four demons, out of Hell.

How stunned he was, Lord of Eternity,

How troubled he was in mind, you know well;

He viewed, almost as if by second sight,

Charlemagne dead, his court destroyed outright.

He discovered this lady of such beauty,

Was King Galafrone’s lovely daughter,

Full of deceit, and every treachery,

Commanding evil spells, like her father;

And the maid had journeyed to our country,

For that evil old monarch had sent her,

Accompanied by this knight, her brother,

Named not Oberto but Argalia.

Galafrone had granted him a steed,

Blacker than charcoal, one that ran faster

Than the wind, with grace added to its speed;

A shield, a helm, a breastplate; and after

These gifts a sword, by magic forged indeed.

Brave treasures thus he had, from his father,

His greatest gift, a lance all clad in gold,

Of precious workmanship, and worth untold.

Galafrone sent him forth with all this gear,

Deeming his son would prove invincible.

And gave him too a ring, it would appear,

Whose power, in truth, was scarcely credible.

The ring he’d ne’er employed, yet held it dear.

Its virtue rendered one invisible

If held to the lips, while a spell-bringer

Was thwarted if twas worn on the finger.

And then he asked Angelica the fair,

To accompany him on his journey,

For her face invited love, everywhere,

And drew brave noblemen to the tourney.

And, once the enchanted weapons, there,

Had done their dark work, to Galafrone,

The defeated knights would be shipped, tight-bound,

And imprisoned by that accursed ‘hound’.

Book I: Canto I: 41-44: He quickly overcomes the giants

The sprites he’d summoned, to Malagigi

All of these distant matters had made known;

But let us turn to Argalia, swiftly

That had, but now, arrived at Merlin’s Stone,

Where he had raised a wondrous canopy,

With marvellous skill designed and sewn.

There, overcome by the desire for rest,

He was soon by pleasant slumber possessed.

Not far away the fair Angelica

Had laid her lovely head upon the grass,

Beneath the great pine beside the water,

While the four giants let no intruder pass.

Sleeping, she seemed no human creature,

But a heavenly angel, with that mass

Of golden hair; on her finger she wore

The ring whose power I told you of before.

Malagigi, borne aloft by a demon

Approached the place, in silence, through the air,

He found the lady slumbering by the fountain,

Upon a flowery bank, all unaware,

And guarded by the four, each a mountain

In stature, who fixed him with their glare.

Malagigi cried: ‘You, worthless cattle,

I’ll see you all dead, and not in battle;

Your maces and flails will not avail you,

Nor your curved scimitars, nor your brave darts;

Deep in sleep, I’ll see death come upon you,

Like gelded sheep, and still your evil hearts.’

He delayed not, took up his book anew,

And cast a magic spell, in several parts;

Nor had he turned the close-writ page, and found

Another, ere they slumbered on the ground.

Book I: Canto I: 45-50: But is captured by Angelica and Argalia

Once they were down, he neared Angelica,

And drew forth his sword, stealthily,

To cut her throat but, as he drew closer,

He hesitated, she seemed so lovely.

In two minds, he was forced to linger,

And, at last, decided: ‘Here’s what must be:

I’ll bind her with my magic, to be sure,

And take her as she lies there on the floor.’

He set his naked blade upon the ground,

Then he grasped the book again in his hand,

And read the spell again, that he had found,

But in vain, for naught worked as he had planned,

For the ring she wore kept her safe and sound,

Thwarting the power his art might command;

While the mage, thinking she was bound in sleep,

Tried to plant on her a kiss, long and deep.

From the lady there issued a great cry:

‘Ah, woe is me! Am I, thus, undefended?’

The magician was astounded, thereby;

He’d thought her captive, as he’d intended.

She called out to Argalia, nearby,

Grasping the mage’s arms, while she fended

Him away, till her brother suddenly

Awoke and, unarmed, ran to her swiftly.

As soon as he saw the noble Christian

Behaving so with his darling sister,

The surprise, the shock, well-nigh struck him dumb;

At least, he could take the thing no further;

But, recovering his wits, his feelings numb,

He seized a pine-branch and struck the other,

Crying: ‘You must die, you evil traitor,

That seek thus my sister to dishonour!’

While she cried: ‘Bind the fellow, brother,

Bind him tight, ere I’m forced to let him go,

For, without the ring, you’d lack the power

To contain him, as I can, that I know!’

He ran to obey his sister’s order,

Hastening to where, spellbound by their foe,

The giants lay, and tried to wake the first

He came to, ere the mage had done his worst.

Though he tugged, here and there, with all his might,

He found that all his efforts were in vain,

So, he stripped a length of chain, strong but light,

From the giant’s flail, and hurried back again.

Then he bound Malagigi’s arms, outright,

Though his efforts cost him no little pain,

The neck and shoulders, and the legs also,

Encircling the mage, from head to toe.

Book I: Canto I: 51-53: And whisked away to their land of Cathay

Once she saw that Malagigi was tight bound,

Angelica sought his book of magic,

And at his breast the sacred tome she found,

That bound spirits, slavish and demonic.

She opened it at once, and, all around,

Soared a host of such sprites, all in frantic

Motion, filling the air o’er sea and land,

Clamouring loudly: ‘What is your command?’

She answered: ‘Take this fellow far away,

Past India and Tartary, to that city

In my father’s great kingdom of Cathay,

For he, Galafrone, rules that country.

Present him to my sire as mine, then say

That I’ve caused him to be taken swiftly,

And that since he’s been made a prisoner

The rest but slight annoyance will offer.’

Once she’d ceased speaking, in an instant,

Malagigi was whisked off through the air,

And presented to her father that same moment,

Then held neath the sea. in a stony lair.

Angelica scanned the book, now intent

On rousing the giants still slumbering there,

That oped their eyes, and yawned in vast surprise,

Wondering what had caused their near-demise.

Book I: Canto I: 54-58: Astolfo is chosen, by lot, as the first to fight Argalia

While these events transpired, the tension

Mounted in Paris, for Count Orlando

Thought he should be the first to champion

The cause, and take the field against the foe;

But Charlemagne was of the firm opinion

That it was wrong for him to argue so,

Since each man thought himself the finest knight,

And, thus, that he should be the first to fight.

Orlando was greatly afeared that he

Would have to, sadly, concede the lady,

For her brother might be conquered easily,

And she be handed to the victor, promptly.

He himself was assured of victory,

So much so, he thought her his already,

And was annoyed he must wait to appear,

For, to a lover, an hour seems like a year.

The question was now openly discussed,

In grand council, by all the royal court,

As to what order might prove fair and just;

And, once every man had aired his thought,

Twas agreed that to Fortune they’d entrust

The matter, and so draw lots ere they fought,

To see who should first seek the honour

Of winning this fair maid from the other.

Thus, the name of each martial paladin

Was inscribed on a separate slip in turn,

And each Christian lord, and Saracen,

Threw his own into the large golden urn.

Next, a little lad stepped before the men,

And gave the lots, within its depths, a churn,

Then drew them one by one; the first to hand,

Was that of Duke Astolfo, of England.

Next was that of Ferrau, then Rinaldo,

While the fourth lot that was drawn named Dudon;

Then came the witty giant Grandonio;

Belengiero, with Otton, upon

His heels; then King Charlemagne’s did show.

And, in short, thirty more had come and gone,

Before Orlando’s lot appeared in sight;

I’ll not say how that tormented our knight.

Book I: Canto I: 59-67: He is unhorsed and taken prisoner

The day was declining towards evening,

Ere the lots had all been drawn, and displayed.

Then Duke Astolfo, eager for the fighting,

Proudly called for his armour, undismayed

Though night approached, and the sky was darkening,

Saying as bold men do, when unafraid:

In a brief while, the contest would be won;

And Oberto, with his first blow, undone.

You should know Astolfo the Englishman,

Was handsome, and, in that, beyond compare,

As courteous as wealthy, and no less than

Charming in his mode of dress, and his air.

His strength was less evident when he ran

A course in the lists, oft toppled there,

Yet, when he was, he’d blame ill fortune, then

Ride forth, fearlessly, to be downed again.

To return to our story, he was dressed

In armour that was worth a deal of treasure;

His shield adorned with pearls, of the finest,

His mail of pure gold, wrought for his pleasure;

While his helm was more costly than the rest,

Thanks to a gem, precious beyond measure,

That was, if Bishop Turpin tells no lies,

A great ruby, like a walnut in size.

His steed was covered in a leopard’s skin,

With trappings that were wrought of finest gold,

He issued forth alone, convinced he’d win,

And fearing naught, being as brave as bold.

It was late, and the shadows drawing in,

When he reached Merlin’s Stone, raised of old,

And as he reached the place, that handsome knight

Blew loudly on his horn, with all his might.

At the sound, Argalia rose to his feet,

(For he’d been sleeping by the fountain’s side)

Donned his armour, and when it was complete,

And he was clad head to foot, full of pride,

He set out this ardent enemy to meet,

Clad all in white, as was his steed beside.

With shield on arm, and this same lance in hand,

He’d felled many a knight, you understand.

They saluted each other, courteously,

And renewed the terms that had been agreed,

As Angelica rode to meet them, calmly;

Then they drew apart, each upon his steed.

They turned together, simultaneously,

Then, crouched behind their shields, advanced at speed,

But, at the very first touch, Astolfo

Flew upwards, legs above, and helm below.

The duke lay sprawling there upon the sand,

And cried, in his anguish: ‘Cruel Fortune,

My foe for no reason, this you’ve planned!

You thrust me from the saddle, all too soon;

Deny it if you can. Twas underhand!

I know all men must dance to your tune,

For, had I but stayed there, I’d have won her,

And yet tis the Saracen you honour!’

The mighty giants now seized Astolfo

And led the duke within the tent nearby.

Angelica was moved to pity though,

Once his armour was removed; to her eye

He seemed both handsome and refined; and so

She had those huge warders, standing by,

Treat him well, and with proper courtesy,

Or as much as prisoners ever see.

And there he remained, unwatched and unbound,

Solacing himself beside the fountain,

And, while the moon shone, Angelica found

Him a fair sight; when twas clouded again,

She sent him to a bed, draped all around,

And stood guard with the giants, as and when,

While Argalia stood sentry at her side,

As darkness cloaked the land, both far and wide.

Book I: Canto I: 68-73: Ferrau takes up the challenge

At dawn, though the shadows had barely fled,

Bold Ferrau appeared, all armed for the fight,

And blew on his war-horn to wake the dead,

Such that the world seemed ending outright.

Every creature nearby turned tail, and sped

From the thunderous noise, in their sheer fright;

Only Argalia felt no terror,

But leapt to his feet, and donned his armour.

The bold youth seized his helmet, and then ran

To his steed, mounted, urging its advance,

His sword hung at his left side, and began

A fierce charge, firmly grasping shield and lance.

Rabicano, his courser, like the man

Showed no fatigue, but o’er the sand did dance

So swiftly, so lightly, that where he’d been

Not a trace of their passage could be seen.

Ferrau waited there, consumed by longing,

Like all lovers, impatient of delay,

And when he saw Argalia advancing

Paused not, some mighty challenge to convey,

But charged him wildly, without saluting,

With lowered lance, about to gain the day,

For he’d have sworn an oath, that, surely,

He must conquer, and so win the lady.

But at the first touch of Argalia’s spear,

He was shaken to the core; in a trice,

All his courage seemed like to disappear,

His ardour spent; as if caught in a vice,

His chest compressed; and then the knight, flung clear,

Hit the ground so hard his blood turned to ice.

And yet, as Ferrau lay there, stretched full length,

He summoned up his valour and his strength.

Their love, or youth, or their very nature

Will often make men quick to take offence,

And Ferrau now loved beyond all measure,

And was so young, his pride was so immense,

That to be near him engendered terror,

For the slightest cause did his mind incense,

And sent him forth, his weapon in his hand,

As his quarrelsome soul did e’er demand.

No sooner had he touched the ground below,

Than deep anger and shame raised him once more,

Forgetting the terms he’d agreed with his foe,

And, consumed by both, he now thought to draw

His blade and, though on foot, avenge the blow.

He ground his teeth, and charged him, as before,

As Argalia cried: ‘You’re my prisoner,

And have no right to oppose me further!’

Book I: Canto I: 74-83: He fights the giants

Though bold Ferrau feigned not to hear his foe,

As he recklessly advanced o’er the ground.

Now the giants had been roused in the meadow,

And, fully-armed, came running at the sound,

While emitting such a fearsome bellow

No thunder-crack e’er matched it, I’ll be bound.

Bishop Turpin says (a comment to astound!)

That it shook the fields for two miles around.

Ferrau, on hearing, turned his head their way,

Yet (believe me) showed not a sign of fear.

Argesto (immeasurable, I would say)

The largest, was the first one to draw near.

Lampordo was the next to join the fray,

Covered with hair, a beast he did appear;

Urgano was third; while, thirty-feet tall,

Turlone was the fourth to meet the call.

Lampordo’s spear struck Ferrau on the thigh,

And if his life had not been charmed, surely

That warrior would have been slain thereby,

And that first blow had undone him, wholly.

But no storm-wind o’er the ocean doth fly,

No lightning speeds through the air as quickly,

No leopard springs, no greyhound is as fleet,

As Ferrau, who sought vengeance to complete.

He struck Lampordo in the lower belly,

And pierced, thus, his doughy flesh, side to side,

Striking the groin, through stomach and kidney.

One blow was not enough, for in their pride,

The other three attacked him, suddenly,

While Ferrau swung again, striking wide.

Only Argalia gave him no trouble,

That merely sat his steed, to watch the battle.

Now Ferrau leapt twenty feet through the air,

And struck Urgano on the head, so hard

He cleft him to the teeth, beyond repair;

While he was thus occupied, still unmarred,

Argesto swung his mace; all unaware

Brave Ferrau received the blow and, off guard,

Was struck on the head, and with such a thud

That both his nose and his mouth spouted blood;

Though this but rendered him fiercer, for he

Was a man without fear, and so he brought

The giant to the ground, cleaving him wholly,

From the shoulder to the waist, as they fought;

Yet was not free of peril, completely,

For Turlone, from behind, his body caught,

And offered a real and sudden danger,

Possessed of a strength beyond all measure.

He embraced him, and carried him away,

But by fortune or strength Ferrau won free,

(I know not which) and all was still in play:

The giant wielding his iron club freely,

While, with his sword, Ferrau kept him at bay,

As they continued to battle fiercely,

With greater force than I could say or show,

Each striving to demolish his strong foe.

The result of the fight was as follows:

That Turlone the giant’s show of force,

Had shattered Ferrau’s helmet, and his blows

Had left the head unprotected, yet the course

Of the battle was changed, for Ferrau chose,

In a stroke aimed full low, to seek recourse,

And sliced at those legs clad in chain-mail,

Severing both, and, thus, thought to prevail.

The one near death, the other simply dazed,

Dropped, both of them together, to the ground.

Argalia leapt down, somewhat dismayed,

And bore the knight to the fount, at a bound,

Where the cool water, once twas gently sprayed

On his face, restored him; his wits yet sound.

Argalia would have borne him to his tent,

But Ferrau would neither yield nor consent.

‘What is it then, to me, if Charlemagne

Agreed to your Angelica’s demand?

Am I so much his slave, I may not claim,

To fight on; though unseated by your hand?

Love drove me on to fight; tis why I came,

To win your sister thus, you understand;

I must possess her now, or seek to die.’

Such was Ferrau’s desire, and his bold cry.

Book I: Canto I: 84-91: Ferrau provokes Argalia into renewing their duel

The sound of their quarrel woke Astolfo,

Who, till that moment, had been fast asleep,

Deaf to every thunderous shout or bellow

From the giants, and slumbering long and deep.

As the knights now bandied words to and fro,

He sought to intervene, and thereby keep

The peace, between the pair, end their discord,

Though Ferrau would scarce a hearing afford.

Argalia cried: ‘Can you not see, sir knight,

That you are now disarmed, your head revealed?

Perchance you think your helm is rather light?

Why, tis left there, in pieces, on the field!

I leave it to your judgment, as of right,

To choose if you would die, or better, yield.

If you fight on, with naught to hide your head,

Our duel must end swiftly; you’ll lie dead!’

Ferrau replied: ‘It grants me courage thus

To battle without helmet, shield or mail,

And so, honour the battle fought between us.

I’d fight naked, still hoping to prevail,

To win a lady half so glorious!’

So did the amorous knight with words assail

Argalia, for Love stirred such desire

In him, for her, that he’d have leapt through fire.

But Argalia was troubled that the knight

Appeared to hold him in such low esteem,

As to offer to duel naked; that first flight

Through the air, and the second, it would seem

Had done naught to reduce the towering height

Of his arrogance; his pride was still extreme.

‘Sir knight,’ he cried, ‘if you’ve an itch, indeed

I’ll scratch it for you, in your hour of need!

Mount your steed, and do the best you can,

For I’ll treat you as you’ve now deserved;

Nor would I hold back from any man

Because his head upon a plate was served.

If, in truth, to seek but ill is still your plan,

Then for you, I think, this hour was reserved!

Defend yourself, now, and show your valour;

You must be slain, and I achieve that honour!’

But Ferrau laughed at his words, as if he

Esteemed such a flow of words but little.

He mounted his horse, and cried, loudly:

‘Hear this, worthy knight! Concede the battle!

Grant me your sister, and do so promptly,

And I’ll grant you, in turn, your acquittal.

Fail to do that same, and I guarantee,

Midst the shades, in the other world you’ll be!’

Argalia, overcome by anger

At the arrogance Ferrau thus displayed,

Leapt on his steed, roused by his ill manner,

Cursing aloud, and threatening with his blade;

Naught that he cried could be heard, however.

With drawn sword, a swift attack he made,

Spurring his horse (leaving his lance behind

Leaning against a tree) with rage, near blind.

Both urged their chargers on, quite recklessly,

Driving their coursers hard against the foe.

No knight on earth e’er charged more furiously.

Neither bold Rinaldo, nor Orlando,

Would have outpaced that pair, it seems to me,

Nor would have gained the least advantage so.

Of a fine duel then, my lords, you’ll hear,

If, to my next canto, you’ll lend an ear.

The End of Book I: Canto I of ‘Orlando Innamorato’