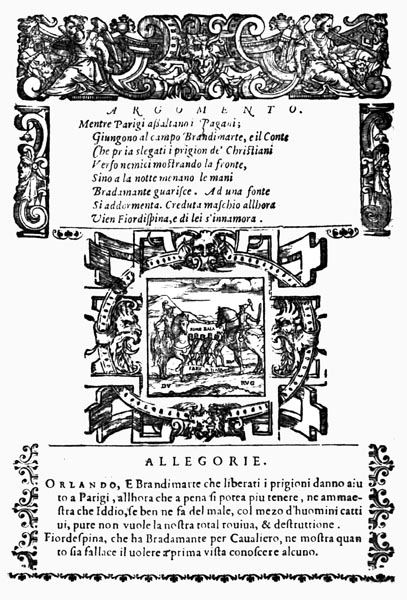

Boiardo: Orlando Innamorato

Book III: Canto VIII: Paris Besieged

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2022, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book III: Canto VIII: 1-2: Boiardo’s address to his audience

- Book III: Canto VIII: 3-10: The scene in and around besieged Paris

- Book III: Canto VIII: 11-15: The Saracen assault begins

- Book III: Canto VIII: 16-18: Orlando and Brandimarte descend to the fray

- Book III: Canto VIII: 19-24: They free Marsilio’s prisoners

- Book III: Canto VIII: 25-31: Rodomonte invades the city

- Book III: Canto VIII: 32-36: The Saracens gather to him

- Book III: Canto VIII: 37-41: Brandimarte distinguishes himself

- Book III: Canto VIII: 42-46: Charlemagne unseats Agramante

- Book III: Canto VIII: 47-50: Rodomonte and Orlando contend

- Book III: Canto VIII: 51-58: Bradamante and the Hermit

- Book III: Canto VIII: 59-63: He cuts her hair and treats her wound

- Book III: Canto VIII: 64-66: Fiordispina falls in love with Bradamante

Book III: Canto VIII: 1-2: Boiardo’s address to his audience

May God grant joy to every sweet lover,

And to every bold knight true victory,

To great princes and lords, land and honour,

And to those in love with virtue, glory.

May peace and plenty surround us ever,

And to you, who listen to my story,

May Heaven’s King deliver to you, there,

Whatever you may ask of Him in prayer.

May He see you grasp Fortune by the bridle,

And may He drive all mischance far away,

And grant every wish you have (in total),

For beauty, wisdom, power, or fine display,

Whate’er you may desire, your glass brimful,

Since every one of you grants to me, this day,

Your courtesy, and seems ever-willing

To hearken to the tale now forthcoming.

Book III: Canto VIII: 3-10: The scene in and around besieged Paris

I paused my story, when, if you recall,

A mighty roar rose from the pagan side.

Tabors, timpani sounded, loud the call

Of the bronze horns, and others far and wide.

As, from the hill-slopes above them all,

Brandimarte and Orlando now applied

Their eyes to the plain below, it seemed

A vast forest of flags and lances gleamed.

So, you may understand the dispositions,

And the order of the enemy that day,

Paris was assailed from all directions,

Assaults begun, and squadrons put in play.

The Africans, men of those many nations,

Swore their strength and prowess to display;

Some made vows to Allah, some would reap

Fame, and vault the wall with a single leap.

Many a wooden tower and scaling ladder

Was wheeled into place; many a new sight

They viewed, windlasses with ropes of leather,

‘Cats’ of wood, their vine-thongs woven tight,

And mangonels loaded with much labour,

Which, when released, launched, in sudden flight,

Flaming missiles and boulders at the wall,

Destroying all beneath them in their fall.

Within the city, Uggiero the Dane,

Appointed as Charlemagne’s commander,

Prepared his defences, which, in the main,

Were crossbows, catapults, slings, as ever,

Which missiles, on the enemy, could rain.

He sought not to rely on any other,

But himself arranged huge beams, blocks of lead,

Stones, and sulphur, on the turrets overhead.

He ordered and positioned, everywhere,

Armed men on foot, and squads of cavalry;

He was present on the walls, nor did spare

Time for rest, but laboured on endlessly.

The sounds of horns and drums now filled the air,

Trumpets, castanets, a cacophony

Of shrill pipes, and tambourines; everything,

That made the ears throb, and the heavens ring.

O High King of Heaven! O Mary mild!

How wretched the poor city seemed that day!

I doubt the Devil himself could have smiled

Viewing the dread and misery on display.

Cries and screams rose from mother and child,

The old, the ill, the helpless; some did pray

To die that very moment, beat their brows,

Voiced pleas, and offered up their heartfelt vows.

People gathered at random, flushed or pale,

Timid or bold, or ran in disarray;

Sad women urged their husbands to prevail

Clasping their children tightly; some, I say,

Shed their fear though, and refusing to quail,

Helped the men; bore pails of water by relay,

Or carried rocks and boulders to the wall,

Quite determined that Paris should not fall.

The sound of bells signalled the call to arms;

The war-horns and the cries raised such uproar

No words could describe those wild alarms.

Across the city rode their emperor,

His knights behind; and every man-at-arms,

Vowed to die, that others might rest secure.

He sent men here and there, and disposed

His forces gainst the armies they opposed.

Book III: Canto VIII: 11-15: The Saracen assault begins

Paris gazed down on the advancing foe,

Rank on rank, the glittering lines spreading far.

Gainst Porte Saint-Marcel rode King Sobrino,

With Bucifaro, King of Alcazar;

While that false Saracen Baliverzo,

Where access to the Seine men tried to bar,

Breached the city walls, with his evil horde,

Joined by Fez’s king, and Arzila’s lord.

At Saint-Denis, the King of Nasamona,

With Zumara’s bold monarch, tempted fate;

While the lords of Tremizon, and Ceuta,

Fought furiously near the Market Gate.

The air and earth shook, the noise grew louder,

As battle was joined, nor would soon abate,

While stones and fiery darts flew to and fro,

As each side struggled to outdo the foe.

Christians and Saracens had seldom fought

With such fury against one another;

Striving to show their worth, twas death they sought,

As lime, and sulphur, and lengths of timber

Cascaded down, fierce missiles of every sort;

While ladders, and armour, broke asunder,

As dense smoke, and clouds of dust, cast a veil

O’er the sky, till the sun could scarce prevail.

It seemed no defence could prove sufficient

Against such an onslaught, for as the bees

And wasps, and flies seldom seem deficient

In returning to haunt one, without cease,

So that ruthless foe, fierce and proficient,

Came again, though repelled, yet not with ease,

For bodies fell from battlement and tower,

And filled the city’s moats within an hour.

A path of blood floated on the water,

Dreadful to look upon. Mandricardo

And Rodomonte, aiding each other,

Struggling to scale the heights, proved not slow.

Nor was Agramante deterred moreover,

Nor Ferrau, vying to attack the foe,

Seeking to be the first to mount the wall;

In their pride, careless of what might befall.

Book III: Canto VIII: 16-18: Orlando and Brandimarte descend to the fray

Orlando, gazing down on the affray,

Was well-nigh daunted by that fierce assault,

And then, groaning aloud, began to pray,

Scarce knowing whether to descend or halt.

‘O Brandimarte, what to seek this day?

If Charlemagne is dead, our troops at fault,

What may a man do? For, below, I see

Naught but our ruin, flames, and misery!

All aid, I now believe, must come too late,

For the Saracen foe are mounting the wall.’

‘Why, if I see clearly, I would deem our fate

Undecided; on ourselves men yet may call.’

Cried Brandimarte, ‘Let me add my weight

To our defence, for I would slay them all,

All those hounds; and though Paris may expect

Scant help from us, vengeance she’ll not reject!’

To that, Orlando answered not a word,

But closed his visor, and followed after,

For Brandimarte, having thus conferred,

Sped down the slope on his valiant charger.

Fiordelisa present risk now inferred,

And hid in a grove, to avoid the danger,

As those two cavaliers, nigh wreathed in flame,

Crossed the river, and to the battle came.

Book III: Canto VIII: 19-24: They free Marsilio’s prisoners

Both were soon known; their brave pennants unfurled.

‘To arms!’ the Saracens cried, as they appeared.

Despite the spears and darts that oft were hurled,

Marsilio’s tent those brave knights had neared,

Which that king, the lord of his hostile world,

Now defended, though scarcely had he feared

An assault; by him stood Falsirone,

And the men set to guard the enemy,

Those they held captive; Oliviero

Was one, and the brave Desiderio,

And the lord of Poitiers, Count Gano,

A host of Germans, and bold Ricardo,

And Brittany’s King Salamone, also.

There the two brave knights slew the foe;

Some of whom now stood firm, while others fled;

While a sudden charge laid full many dead.

Battle raged round the king’s pavilion,

Nor could Marsilio secure the place.

Many of his royal guard were dead or gone;

Then, he himself fled the field, in disgrace.

Orlando tore down the tent, and rode on,

And, when the prisoners beheld his face,

They marvelled, and crossed themselves to a man,

While Brandimarte cut their bonds; all began

To arm, with the weapons that lay to hand,

Then they mounted as swiftly they could,

Eager to join Orlando, with lance and brand.

He sped towards the city, seeking blood.

Close behind, to Paris rode that band,

Hoping to nip the foe’s assault in the bud.

In the lead rode Marquess Oliviero,

With the lord of Poitiers, Count Gano.

Then Desiderio, Salamone,

And Ricardo, and Belengiero,

And then the valiant Brandimarte

Who had freed them, with Avorio,

And Avino, beside the bold Ottone,

Dukes Namus and Amone; gainst the foe

Rode that band of noblemen, while, in sum,

A hundred chargers made the ground to thrum.

Twas not long ere they reached the city wall,

Where the battle raged ever more fiercely.

And all was dark, still obscured by the pall

Of smoke and dust, I described, while shrilly

Rose the trumpet’s blare, and the dying call

Of many a victim, seeking mercy.

The battlements shook, and naught around

But fire, blood, death, filled all that ground.

Book III: Canto VIII: 25-31: Rodomonte invades the city

Mandricardo had seized a bridge, destroyed

The barriers, and then brought down the gate.

His soldiers were now eagerly employed,

Jostling each other, lest they proved too late

In showing their valour. Rodomonte toyed

With victims on the walls, hurled to their fate,

A goodly many, sending them to float

Midst streams of blood; crimson was the moat.

He viewed the lofty towers above with scorn,

Foaming like a boar, and gnashed his teeth,

So fierce a Saracen had ne’er been born.

His shield at his back, he bowed beneath

Spikes and hooks, coils of rope, a ladder borne

Upon his shoulder, a blade in its sheath,

An oak-tree trunk, fire within; he blasphemed,

Leant his ladder against the stone, and seemed,

As he climbed, like one who strolled along

A street; just so the cunning pagan scaled

The turret; here was ruin, there a throng

Fought, or cried for aid, or were impaled.

If Lucifer had issued, fierce and strong,

From the depths (and, once above, was hailed

By his faithful) to raze Paris, from on high,

No greater could have been the dread, thereby

Aroused in his foes. In desperation,

Our men fought for themselves, about to die,

Careless of life and limb, and for their nation,

Brought to that sorry state; without a sigh,

Each sought to hold, and defend, his station,

Sensing their fate; striking, if he came nigh,

That warrior with spears, and darts, and stones,

And massive beams; fear in their very bones.

Still, he climbed on, to the highest tower,

His foes like straws or feathers in the breeze,

Unstoppable by any mortal power,

It seemed, reaching the summit-wall with ease.

Panic swept the city at that dark hour,

And, midst the other pains and miseries,

Rose a piercing wail of lamentation,

That soared above the earthly creation.

Now the proud warrior clawed at the stone,

Loosening great blocks from their mortar,

And hurled them down, to mar flesh and bone,

Downing houses and spires; great the slaughter.

To the Count, fighting elsewhere, naught was known

Of the vast destruction in that quarter,

But the uproar that arose, the loud commotion,

Alerted him; he set his steed in motion,

And rode, at speed, towards the bitter fray.

Never had he been so filled with anger;

Grasping his sword, he climbed, and cut away

The lower part of Rodomonte’s ladder,

Sending that warrior to the moat, that lay

Far below, though the turret followed after

And mighty stones struck Orlando’s head,

Felling that warrior to the ground, half-dead.

Book III: Canto VIII: 32-36: The Saracens gather to him

Rodomonte freed himself, quite promptly.

So strong and fierce was the Saracen king,

To him twas an irritation, merely,

An annoying, inconsequential thing.

The Count though had been rendered wholly

Stunned and mazed (death passed him by on the wing),

And lay still, as the other left the moat

Ready to seize the city by the throat.

Our troops surrounded the pagan warrior.

Gano of Poitiers stood on the shore,

Who though false and evil-minded ever,

Fought well when he so wished, brave to the core.

Rodomonte showed his strength however,

And Count Gano in vain his weapons bore,

For Rodomonte felled him with a blow,

Then charged on, further ruin to bestow.

Quitting his victim, he met Rodolfone,

A kinsman of Duke Namus, in the field.

He cleft him to his saddle, ruinously,

Then forced King Desiderio to yield,

Aiming a blow at his head, which merely

Grazed his helmet, then struck upon his shield,

Thank God! But still the King of Lombardy

Knocked from his steed fell, most awkwardly.

Those Saracens that had fled Orlando,

Now regrouped, seeming bolder than before,

And aided Rodomonte gainst the foe

Most willingly, now he’d regained the shore,

And charged, thrusting fiercely, to and fro,

As upon the ranks of Christians he bore.

Balifronte of Mulga, and Grifaldo,

Were there, and that villain Baliverzo,

Besides Farurante of Marina,

Tremizon’s valiant King Alzirdo,

Gualciotto of Bellamarina,

And full many another of our foe.

Yet none of them will appear hereafter,

Not one of them will fight on the morrow.

Oliviero some of them will fell;

Brandimarte will send the rest to Hell.

Book III: Canto VIII: 37-41: Brandimarte distinguishes himself

Stay, and hear the facts stated clearly,

For twas now the dance truly began.

Salamone advanced on Rodomonte,

Who was taller than every other man,

And struck the king where he aimed, full fiercely,

In the centre of his chest; such his plan,

But his lance broke, the pagan was unmoved,

And his return-blow much the fiercer proved.

For his sword split apart the Christian’s shield,

Slicing through the steel as if twere paper,

Shattering his armour, his chest revealed,

And descending to his saddle, thereafter.

Last he hacked his horse’s head to the field.

Brandimarte viewed that swift disaster,

And, seeking vengeance, he lowered his lance,

Spurred his steed, savagely, and seized the chance

To strike Rodomonte’s ribs, with huge force.

Though the latter’s serpent-hide saved the man,

He was driven back, sharply, in his course.

Staggering o’er the ground, the African

Fell with a crash; thus, the wind will divorce

Some oak from the soil, of many a span,

That, split in two, uprooted by the blow,

Crushes lesser trees, as it sinks below.

Brandimarte now met Gualciotto,

Having watched that bold King of Sarza fall,

And with both hands he landed a stout blow,

That split his shield and then shattered all

The hauberk, and the stomach-plate below.

His stroke, indeed, the victim’s did forestall,

And Gualciotto, his body cut in two,

Dropped to the field, sliced through and through.

Then Oliviero showed his mettle

And gave evidence of his noble birth,

His House not discredited in battle,

As his sword measured King Grifaldo’s girth.

The Count, reviving, mounted the saddle,

Having found himself stretched upon the earth,

For wise Brigliador, valiant in his pride,

Never strayed far from Count Orlando’s side.

Book III: Canto VIII: 42-46: Charlemagne unseats Agramante

Orlando, his wits quite sound, left the moat,

And, when his quartered shield he displayed,

A cry rose from every Christian throat,

As their brave champion flourished his blade;

While King Charlemagne, instantly, made note

Of his presence, amidst the troops arrayed,

As the news came of their deliverance,

Through combat, from the Saracen advance.

Ask me not of the emperor’s delight,

As he learnt that their lines were now secure,

While courage filled the heart of every knight,

As they sallied forth again to the war.

The city gate was opened to the light,

And Guy of Burgundy rode out before

The Dane, and Duodo of Antona,

With Huon of Bordeaux pounding after.

Charlemagne led the charge; the emperor

Would not be left behind in the city,

Where his deputy, Bishop Turpin, saw

To the defence of Paris, now his duty.

Mandricardo who, as I’ve said before,

Fought at the bridge, beside Agramante,

Now encountered the Dane, Uggiero,

As he, with lowered lance, rode at the foe.

Since Mandricardo was on foot, he thought

To drop him in the ditch, but greatly erred.

The Saracen stood firm; fiercely he fought,

And nothing of the kind, in truth, occurred.

He failed to fall to the lance, and swiftly caught

The Dane’s charger, Rondello, as he spurred

Past his face at the gallop, by the rein,

And then hard upon the bridle did strain.

King Agramante was fighting at his side,

And together they unseated Uggiero,

Bur Charlemagne, in his headlong ride,

Thrust with his lance, straight at his royal foe.

He knocked the latter to the ground, upside

Down, trampling him with many a hoof-blow.

Then the battle re-commenced, man to man,

As knights duelled, each with victory his plan.

Book III: Canto VIII: 47-50: Rodomonte and Orlando contend

The word spread that Agramante was floored,

And his friends vied to gather to his aid.

Here was Grandonio, Volterra’s lord,

There Ferrau; a third, Balugante made.

But Mandricardo did most help afford,

And defended the monarch with his blade.

He rescued Agramante from all danger,

While bristling like a dog in a manger.

Alone he fought, at first, and full many

Were hurled from that bridge into the moat.

The water beneath his feet ran bloody,

Like the stream that flows from a wounded throat,

Bright crimson, while the depths shone like ruby,

And gore the bank’s mud and stone did coat.

Charlemagne, Uggiero, and the rest,

In their fury, upon the pagans pressed.

From the bridge they drove the Saracen horde,

And confined the foe twixt the ramparts, there,

Till at the pagans’ rear, Anglante’s lord

And the bold Brandimarte, that brave pair,

With their troop, fresh assistance did afford.

The fury now increased, cries filled the air,

Till never was there such a battle seen;

None so vicious and merciless, I mean.

For proud Rodomonte chased the Count,

Without cease along the paths thereabout,

Orlando, not minded to dismount,

Striking at the throng, with many a shout,

Scarce needing to aim, so small an amount

Of space lay twixt his foes; yet twas no rout.

Rodomonte and the Count thrust, and bored,

A path, a mere sword’s-length deep and broad.

Book III: Canto VIII: 51-58: Bradamante and the Hermit

Perchance it was because the people prayed

Behind the walls of Paris, or twas fate;

But a tempest its darkening clouds displayed,

And an earthquake shook all beyond the gate,

While, within the city, the buildings swayed.

Thunder rumbled, the rain fell, in full spate,

Turning the ground to mud, and flooding all,

Till their sodden state could not but appal.

And that the sun was sinking, towards eve,

Made the scene appear all the more dismal.

The fighting ceased, as you may well believe;

Men retreated, for the rain ne’er ceased to fall.

Now, the history that Turpin did conceive,

Which I, in verse, from out his prose recall,

Turns to speak of the fair Bradamante,

Whom I quit, she having slain Daniforte.

That false pagan she had killed in the field.

He had tricked, and wounded, her badly,

And, after that, the maid had strayed, concealed

By the night, and lost her way completely.

She wandered, morn and eve, the blood congealed

O’er her wound, through an unpeopled country,

Until she came upon a hermitage,

Of which there were full many in that age.

She was, in truth, in urgent need of rest,

Having lost a deal of blood ere that morn,

On her long and weary way and, a guest

In need of aid, she arrived thus, all forlorn.

She dismounted, and the door firmly pressed,

Then knocked until the hermit, in the dawn,

Showed his face, crossed himself, and loudly cried:

‘Hail Mary, who unto my cell doth ride?

What chance brings you to my dwelling-place?’

The warrior-maid replied: ‘I am a knight,

And have lost my way, wandering for a space,

In a dark wood, o’er the wilds, day and night,

I am wounded, and need rest, of your grace.’

The hermit cried: ‘You prove a welcome sight!

For sixty years have I dwelt here, alone,

And ne’er a human face have I been shown.

Yet the Devil doth oft to me appear,

In more shapes and forms than I can tell,

Thus, I doubted who it was, drawing near,

And so hid within the depths of my cell.

I see visions, and in the dawn-light clear,

I saw a vessel sailing; I saw it well,

A little barque full of souls, on it sped,

Its oars moving, as if o’er some watery bed.

The helmsman, standing at the stern, he cried:

“Idle brother, the valiant Ruggiero

Is leaving France. Upon the Christian side

He might have fought, loyally, gainst the foe!

We turned him from Mahomet; he denied

Allah’s power, almost; or I deemed twas so,

Yet now I think he’ll not escape that creed.

I tell you, that you might pay better heed!”

The ship passed onwards, as that evil sprite

Ceased speaking, and I saw it not again,

Yet was dismayed at what he’d said in spite,

Believing the man’s soul lost, for tis plain

To me, that if God fails to aid the knight,

And chooses not, of His mercy, to ordain

The warrior’s baptism, damned he will be,

When he dies; excluded from the mystery.’

Book III: Canto VIII: 59-63: He cuts her hair and treats her wound

On hearing this, the maiden blushed, on fire,

Her face aflame, thinking of Ruggiero,

Whom she loved deeply, filled with the desire

To see him once more, and distracted so,

That her thoughts to the heavens did aspire,

And she hardly cared to rest, here below,

Although the hermit, viewing her wounded head,

Offered her treatment, and an easeful bed.

He was so adept at calming her mind,

That, at last, she accepted his kind aid,

But he was somewhat amazed then, to find

The coils of hair that her helm displayed.

He was troubled by her tresses, resigned

To this being the Devil, thus arrayed

In female form, and knew not what to do.

‘Ah, he tempts me! he cried, ‘All here’s untrue!’

But he learned, by further touching her head,

That she was but flesh, and no empty shade,

And he treated her with herbs, where she bled,

And brought her to health; the wound did fade.

Yet, to clean and close it so, he’d been led

To shear those tresses from the lovely maid;

He’d trimmed them all, till she looked like a boy.

He bade her farewell, a blessing did employ,

And told her: ‘You must leave this place, my dear,

For an honest man can scarcely let you stay.’

At length she reached a river, bright and clear,

That traversed the woodland, along her way.

The sun had reached its zenith, twould appear,

And the maid was keen her thirst to allay,

So Bradamante dismounted on the shore,

And drank, and then lay down to rest once more.

Ere she did so, her helmet she unlaced,

Setting down her stout shield, for none was nigh;

Then her cropped head upon her arms she placed.

Now, as she slept, a hunt came riding by,

And a lady, midst the other huntsmen, chased

Their prey, with hawks and deerhounds, and full high

Was her rank; Fiordispina was her name,

The fair daughter of Marsilio of Spain.

Book III: Canto VIII: 64-66: Fiordispina falls in love with Bradamante

Out hunting, she drew near, as I said,

That river, and thus saw Bradamante,

Whom she took for a valiant youth instead

Of a warrior-maid; the face was lovely,

And the form, and many a thought filled her head

Of an amorous kind, while, inwardly,

She cried: ‘By Allah, the powers of Nature

Ne’er achieved so beautiful a creature!

How I wish I were here alone; that I

Had left the rest in the woods, far away,

Or dead, for all I care!’ She gave a sigh,

‘And might kiss this fair youth, while he doth stray

Through Sleep’s far realm and, sweetly, here doth lie.

Patience, I need, and so must here display.

One shameful act, wrought in fatal measure,

May cause the loss of our greatest treasure.’

So Fiordispina dwelt on that fair sight,

Though merely gazing failed to satisfy.

She thought he slept so sweetly, that fair knight,

That she sought not to wake him with a sigh.

But we have filled the normal measure quite

Appointed for our cantos; by and by,

We must rest; next time I’ll tell their story.

God keep us, in pleasure, and in glory.

The End of Book III: Canto VIII of ‘Orlando Innamorato’