Homer: The Iliad

Book XX

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk XX:1-74 Zeus allows the gods to enter the battle

- Bk XX:75-152 Apollo rouses Aeneas

- Bk XX:153-258 Achilles and Aeneas meet in battle

- Bk XX:259-352 Poseidon rescues Aeneas

- Bk XX:353-418 Achilles attacks the Trojans

- Bk XX:419-454 Apollo rescues Hector

- Bk XX:455-503 Achilles rages among the Trojans

BkXX:1-74 Zeus allows the gods to enter the battle

So, around you, by the beaked ships, insatiable Achilles, the Achaeans readied themselves, and the Trojans likewise, opposite, in the plain, holding the higher ground. Meanwhile Zeus sent Themis from the peak of many-ridged Olympus to call the divinities to Assembly, and she quickly gathered them from every quarter to his palace. Every stream was there except Ocean, and every nymph of the lovely woodlands, the river-springs, and the grassy meadows. They all came to the Cloud-Gatherer’s halls, and seated themselves beneath the marble colonnades Hephaestus had built so skilfully for Father Zeus.

Nor did Poseidon, Earth-Shaker, ignore the goddess’s call, he rose from the sea to join the gathering in Zeus’ house, and seated in the midst asked about Zeus’ intentions: ‘Why have you called us all together, Lord of the Lightning? Are you planning something new for the Greeks and Trojans, now they are on the point of joining battle?

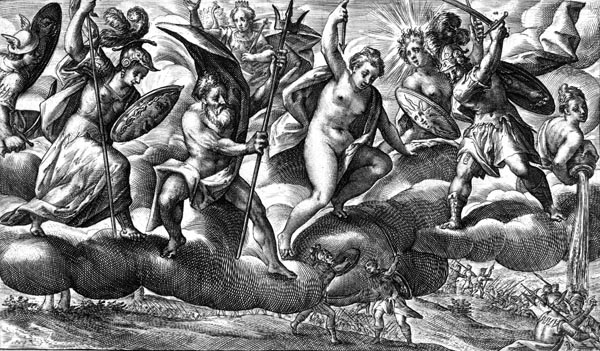

‘Zeus allows the gods to enter the battle’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

‘Earth-Shaker,’ Zeus replied, ‘you have read my mind, and the purpose of this assembly. Even as their warriors die, I consider them. I will stay here, in a fold of Olympus, and watch with interest, while all of you go and aid the Greeks or Trojans, each according to your wishes, though if the Trojans have no help against Achilles, that swift-footed son of Peleus will be through them in an instant. They used to tremble before at the sight of him and now, in his fury over his dear friend, I fear he may elude his destiny, and storm the walls himself.’

With these words, the son of Cronos signalled bitter conflict, and the divinities departed for the field to aid the opposing sides. Hera headed for the ships, with Pallas Athene, Poseidon, Encircler of Earth, Hermes the Helper, he of quicksilver mind, and Hephaestus the lame, with his powerful shoulders, his withered legs still moving nimbly. Meanwhile Ares of the gleaming helm took the Trojan side, with Phoebus of the flowing locks, Artemis the Archer, Leto, Xanthus’ stream, and laughter-loving Aphrodite.

Now, in the absence of the immortals, the Greeks led by Achilles, whom they had missed so terribly in battle until now, had seemed triumphant, for the Trojans shook in every limb at the sight of the swift-footed son of Peleus in his shining armour, that peer of man-killing Ares. But once the divinities had entered the throng, and Strife the great war-monger rose among them, Athene called out, now from the trench beyond the Greek wall, now on the echoing shore, uttering her ringing cry. And Ares, fierce as the dread storm-cloud, urged on the opposing Trojans, now screaming his war-cry from the heights of the citadel, now from the banks of Simois as he ran towards the hill Callicolone.

So the blessed gods brought the two armies together, and whipped up a sorry strife between them. The Father of gods and men thundered ominously on high, while down below Poseidon caused wide earth and the tallest mountain peaks to quake. Ida of the many streams was shaken from foot to crest, and the city of Troy and the Greek ships trembled. So great was the din as the gods opposed each other, that even Hades, Lord of the Dead, was gripped by fear and rose from his throne below in the underworld, crying out lest Poseidon split the earth and bare his halls to gods and men, those dank and fearsome halls that the gods themselves loathe. Great was the din, now, as Lord Poseidon opposed Apollo and his winged shafts, while bright-eyed Athene challenged Enyalius; as Artemis, the Far-Striker’s sister, huntress of the sounding chase, she of the golden arrows opposed Hera; as Leto stood against great Hermes the Helper; as the mighty deep-swirling river, whom gods call Xanthus, and men Scamander, countered Hephaestus.

BkXX:75-152 Apollo rouses Aeneas

So god went against god. As for Achilles, he was eager above all to face Hector, Priam’s son, and sate the god of war, Ares of the stubborn ox-hide shield, with his blood. But Apollo, stirrer of conflict, roused Aeneas to fight the son of Peleus, and filled him with strength. Likening his voice to that of Lycaon, son of Priam, he spoke: ‘Aeneas, counsellor of the Trojans, what has become of the threats you made, as you sat drinking with the other princes, to fight Achilles face to face?’

‘Lycaon,’ Aeneas replied, ‘why urge me to fight the brave son of Peleus, when I reject any such idea? It would not be the first time I confronted swift-footed Achilles. He chased me from Ida with his spear, when he raided our herds and sacked Lyrnessus and Pedasus. Zeus saved me then, giving me strength and speed, or I would surely have fallen to Achilles and Athene. She went before him, a saving light, rousing him to kill the Leleges and Trojans with his spear. No warrior can face Achilles in combat: some immortal always goes by his side to ward off danger. His spear is true and never falls to earth without piercing human flesh. Yet if the gods allowed fair play, he would not beat me easily, even though he thinks himself a man of bronze.’

Lord Apollo, Zeus’ son, answered him: ‘Warrior, why should you not pray to the deathless gods yourself? They say you are a son of Aphrodite, Zeus’ daughter, while Achilles is the child of a lesser goddess, a daughter of the Old Man of the Sea. Have at him straight with the unyielding bronze, don’t let his words of menace or contempt deter you.’

With that, he breathed courage into the Trojan leader, who strode through the front ranks, armed in shining bronze. White-armed Hera saw him advance, as he went to meet Achilles, and gathering her friends said: ‘Poseidon, Athene, decide what we should do. Aeneas, roused by Phoebus Apollo, and armed in shining bronze is set to challenge Achilles. Let’s turn him back perhaps, or one of us stand at Achilles’ side, and strengthen him likewise, give him heart, so he may feel that those who love him are the greatest of immortals, and those who have saved the Trojans from defeat are empty as the breeze. We are here from Olympus to join the war, and ensure Achilles suffers no harm at Trojan hands today, even though in time he must meet whatever fate Destiny spun for him at his birth. If no divine voice tells Achilles of this, he may feel terror on meeting some god in battle, for the gods are perilous when they take on visible form.’

But Poseidon, Earth-Shaker, replied: ‘Hera, control your wrath, be moderate. I would be cautious of causing strife between us immortals. I suggest we find some vantage point out of the way, sit down there, and leave the war to men. Still, if Ares or Apollo enter the conflict, or prevent Achilles from fighting, then we ourselves must be instantly involved, and they, I think, will soon break off the battle and return to Olympus and the gods’ assembly, if we exercise our strength.’

With this, the dark-haired god led the way to the high wall that Athene and the Trojans once built for godlike Heracles, as a sanctuary for his defence when the sea monster drove him from shore to plain. There Poseidon and the others sat down, veiling themselves in dense mist, while on the crest of Callicolone, Apollo the archer and Ares sacker of cities, seated themselves likewise.

BkXX:153-258 Achilles and Aeneas meet in battle

So the immortals on either side sat scheming, yet reluctant to initiate sad conflict, despite the urgings of Zeus on high. Meanwhile the whole plain filled with men, and horses, and shining bronze, and the earth rang under their feet as they advanced. Between the two armies their two champions met, ready to do battle, Aeneas, son of Anchises, and noble Achilles. Aeneas threatened first, his heavy helmet nodding, his glittering shield covering his chest, brandishing his bronze spear. Achilles charged towards him like a lion, one that a village combines eagerly to kill. The lion passes by, indifferent at first, but when a youth agile in a fight strikes it with a spear it roars and gathers itself, jaws foaming, its powerful spirit groaning within, lashing its ribs and flanks with its tail, rousing itself to fight, then rushing with glaring eyes to the attack, plunging in fury among the foremost, either to kill or be killed. So Achilles in his fury was driven by his high heart to attack brave Aeneas.

When they were close to one another, fleet-footed Achilles called to Aeneas: ‘Why do you come from the ranks to challenge me, Aeneas? Do you hope by fighting me to hold power among the horse-taming Trojans, and replace Priam? He will not give way to you, even if you should kill me, since he has sons, and is strong willed, not a man to change his mind. Or perhaps the Trojans have offered you a prime piece of land, a fine tract of ploughed fields and orchards, as a prize if you slay me? That, I think, you may find hard to do. Do I not recall a previous time, when you ran before my spear, all alone, abandoning the herd, running for dear life down the slopes of Ida? I don’t remember you once looking back. You fled to Lyrnessus, but I sacked the place, with the help of Father Zeus and Athene, and I led away the women, and robbed them of their freedom, though you yourself were saved by Zeus and the other gods. Yet I think they’ll let you die today, not save you as you think. Go back to the ranks I urge you, don’t try to face me now, to your detriment. Even a fool can learn from the past.’

Aeneas answered him: ‘Son of Peleus, I am no child frightened with words, I know how to speak myself, both truths and taunts. We know each other’s pedigree and parents, and though I have never set eyes on yours nor you on mine, we have heard the tales men have told of them. They say you are peerless Peleus’ son and your mother is long-haired Thetis, the sea’s daughter, while I boast brave Anchises for my father, and Aphrodite herself is my mother. One pair or the other shall mourn a dear son this day, for I say we shall not part and leave the field without exchanging more than these few childish words.

But if you wish to know my whole lineage, well-known though it is, then Zeus the Cloud-Gatherer’s son Dardanus founded Dardania, before sacred Ilium was built in the plain, when the race still lived on the slopes of Ida of the many streams. Dardanus’ son was Erichthonius, wealthiest king on earth, with three thousand mares grazing in his water-meadows, nurturing their tender foals. The North Wind, enamoured of the mares as they fed, took on a black-maned stallion’s form to cover them, and twelve foals were born, that when they travelled the earth, yielder of grain, could gallop over the tops of the ears of corn without breaking them, and when they crossed a wide arm of sea, could skim across the tops of the grey salt breakers. Tros, son of Erichthonius was the next king of the Trojans, and he had three peerless sons, Ilus, Assaracus, and godlike Ganymedes, the latter being the most beautiful of youths, so much so the immortals raised him up on high to be Zeus’ cupbearer and live with them. Ilus begot peerless Laomedon, and he had sons in turn, Tithonus, Priam, Lampus, Clytius and Hicetaon, scion of Ares. Assaracus’ had sons, Capys and Anchises, and I am the son of Anchises, as noble Hector is of Priam. That is the blood and lineage I claim. As for prowess, Almighty Zeus grants more or less of that, as he sees fit.

Now let us cease from childish talk, here in the midst of war. We could both utter insults enough to sink a hundred-benched sailing ship. The mortal tongue is glib, and many and various the speeches over its wide domain. Whatever we utter: that we may also hear returned to us. So why stand here like angry women in the street caught up in some bitter wrangle, exchanging hostile and contentious words, truths or lies regardless? Such is my desire for glory, your words will not deter me from fighting you man to man, so come, let us try our bronze-tipped spears.’

BkXX:259-352 Poseidon rescues Aeneas

Aeneas then hurled his great spear against Achilles’ formidable and unearthly shield and the metal rang. The son of Peleus, alarmed, held the shield away from his body with his strong hand, thinking brave Aeneas’ long-shadowed spear would pierce it, a ridiculous fear, forgetting that the gods’ fine gifts of weapons are hard for mortal men to conquer or avoid. Though the heavy spear sank in, a layer of gold set there by Hephaestus held it. The lame god had welded five layers, two of bronze, two inside of tin, and one between of gold. Though Aeneas drove the spear through the first two, there were three left, and the ash spear was stopped by the gold.

Achilles now cast his long-shadowed spear, striking Aeneas’ well-balanced shield on the rim where the bronze and ox-hide backing were thinnest. The shield rang as the shaft of Pelian ash pierced it, stripping two layers away. As Aeneas crouching thrust the shield from him fearfully, both flew over his back and the spear stuck in the earth, its fury spent. Having escaped the long shaft, Aeneas stood, his eyes glazed with fear for a moment, appalled by the closeness of the blow, but Achilles gave his war-cry and attacked furiously with his keen sword. Aeneas grasped a stone, a great feat since it was one that no two men of our day could lift, yet he wielded it easily, alone. He might have struck Achilles as he attacked, on the helmet or the shield that had kept him from harm, but the son of Peleus would have had Aeneas’ life, his sword so near about to strike, if Poseidon, Earth-Shaker, had not been watching.

He spoke to the gods, quickly, saying; ‘Now I fear for brave Aeneas, who will descend to the halls of Hades, slain by that son of Peleus, simply for listening, foolishly, to the Far-Striker’s words. Apollo will not save him from destruction. Why should an innocent man, who always makes fine offerings to us rulers of the heavens, suffer harm because of another’s quarrel? Let us rescue him, and avoid Zeus’s anger were Achilles to kill him, for Aeneas is destined to live on, so that Dardanus’ race itself might survive, Dardanus whom Zeus loved above all his children by mortal women. The Son of Cronos has come to hate Priam’s line, and mighty Aeneas will be the Trojan king, as his descendants will in time to come.’

It was ox-eyed Queen Hera who answered him: ‘Earth-Shaker you must choose whether to rescue him or let him die, brave though he is, at the hands of Achilles, Peleus’ son. Pallas Athene and I have always sworn before you all never to save the Trojans from evil, not even when all Troy burns, consumed by the blazing fire those warlike sons of Achaea will light within.’

On hearing this, Poseidon, Earth-Shaker, plunged through the midst of battle and the hail of spears, towards the space where Aeneas and Achilles fought. In a moment, he veiled Achilles’ eyes in mist, plucked the ash spear shod with bronze from brave Aeneas’ pierced shield, and set it down at Achilles’ feet, then lifted Aeneas and swung him into the air, high over the ranks of warriors and lines of chariots, so that with the power of the god’s hand he came to earth on the far edge of the field, where the Caucones were about to join the fight.

Then Poseidon, Earth-Shaker, at his side, spoke to him with winged words: ‘Aeneas, what god has set you on blindly to fight with the proud son of Peleus, who is a greater warrior than you, and dearer to the gods? When you see him, draw back, lest you reach the house of Hades before your time. When Achilles meets his fate, when he is dead, then fight courageously at the front, for no other Greek can kill you.’

When he had imparted all he wished, Poseidon left Aeneas there, and swiftly dispelled the strange mist from Achilles’ eyes. The warrior gazed fixedly about him, and murmured to himself in agitation: ‘A wonder indeed! Here is my spear lying on the ground, but where is the man I hurled it towards, to kill him? I thought his claims were idle boasts, but the immortals must love this Aeneas, too. Well, let him go. He’ll be so glad to have cheated death he’ll not dare to try me again. Now let me call to the warlike Greeks, and we shall try the Trojans instead.’

BkXX:353-418 Achilles attacks the Trojans

So saying, Achilles ran along the line calling to all the Greeks: ‘Noble Achaeans: don’t stand here waiting for the enemy, rouse yourselves for battle, and each pick out your foe. Strong I may be, but they are in such numbers it is hard even for me to fight them all. Not even Ares, immortal as he is, or Athene, could wrestle with the jaws of such a monster. But what a man can do with swift foot, and strong arms, I will attempt. I’ll not be idle, rather I’ll pierce straight through their ranks, and pity the Trojans who come near my spear.’

So he roused them, urging them on, while great Hector was shouting to the Trojans, that he would advance and tackle Achilles: ‘Brave Trojans have no fear of this son of Peleus. I too could fight a war of words, even with the gods, yet it is harder to fight them with the spear, since they are mightier still. Achilles will not make good his boast. Part indeed he may fulfil, but a part he will leave undone. I will go out against him, though his hands blaze fire, yes, though his hands blaze fire and his fury is molten iron.’

With this, he drove them forward, and the Trojans faced the Greeks and raised their spears high, and the war cries rose as their forces clashed together in confusion. Now Phoebus Apollo spoke to Hector: ‘Don’t try to fight Achilles face to face, Hector, stay in the ranks and await him in the din of battle, or he’ll strike you with a cast of his spear or, close up, with his sword.’ Hector retreated into the crowd of warriors, filled with fear at the sound of the god’s voice.

But Achilles, his heart filled with courage, gave his dreadful war-cry and sprang among the Trojans. First he killed a general, Iphition, mighty son of Otrynteus and a Naiad, who, beneath snowy Tmolus in the fertile land of Hyde, bore him to that sacker of cities. Noble Achilles struck the man, who charged straight towards him, striking him smack on the head with a cast of his spear, splitting his skull in two. He fell with a thud, and noble Achilles triumphed: ‘Lie there, son of Otrynteus, most redoubtable of men. Though you were born by the Gygaean Lake, where your father holds the land, by Hyllus teeming with fish, and the swirling eddies of Hermus, here is the place where you must die.’

As Achilles exulted, darkness veiled Iphition’s eyes, and the Greek chariot-wheels cut his corpse to pieces, there in the front line, as Achilles sent Demoleon, Antenor’s son, a strong man in defence, to join him, striking him in the temple, through the bronze-cheeked helmet, which failed to stop the spear, whose point drove through to smash the bone, crushing the brain inside. So he killed Demoleon in his fury, then Hippodamas as he leapt from his chariot to flee, thrust through the back with the point of his spear. Hippodamas breathed his last with a bellow like a bull the young men drag round Poseidon’s altar, to delight the Earth-Shaker, Lord of Helice. So Hippodamas roared as his proud spirit fled his bones.

Then Achilles went after godlike Polydorus, Priam’s son. His father had forbidden him to fight, being his youngest son and dearest to him. He was the fastest runner of them all, but foolishly displaying his turn of speed, running about near the front lines, he lost his life to swift-footed Achilles, who caught him with a cast of his spear, as he shot by, in the back where the corselet overlapped and the golden clasps of his belt were fastened. The spear point emerged beside the navel, and he slumped to his knees with a groan, clutching his guts in his hands, as darkness enveloped him.

BkXX:419-454 Apollo rescues Hector

Hector saw this, and his eyes misted over, and unable to endure the waiting he ran like fire to challenge Achilles, brandishing his keen spear. Achilles sprang towards him, saying exultantly to himself: ‘Here’s the man who wounded me most, who killed my dearest friend. Now here’s an end to dodging one another down the lines.’ With a fierce gaze he called to Hector: ‘Come on, and find the toils of death the sooner.’

But Hector of the gleaming helm answered, fearlessly: ‘Son of Peleus, I am no child frightened with words, I know how to speak myself, both truths and taunts. I know you are a greater warrior than I, yet it lies in the gods’ hands whether I, though the lesser man, will kill you with my spear, which has proved sharp enough before now.’

So saying, he balanced his spear and hurled it, but Athene with her merest breath deflected it from great Achilles, so that it returned to noble Hector and landed at his feet. Then Achilles in his eagerness to kill him, leapt forward with a dreadful cry. But Apollo shrouded Hector in dense mist, and snatched him away, as a god can easily do. Three times fleet-footed Achilles ran in vain at the empty mist with his bronze spear. As he flailed about him, like a demon, for the fourth time, he cursed Hector with winged words: ‘Once more, you cur, you cheat death, by a hair’s breadth. Phoebus Apollo saves you once more, the god you must surely pray to before you dodge the spears. But I promise to make an end of you when we meet again, if some god will but aid me too. For now I’ll kill whoever I can catch.’

‘Hector is saved by Apollo’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

BkXX:455-503 Achilles rages among the Trojans

With this, Achilles pierced Dryops in the neck with a thrust of his spear, and Dryops fell at his feet. Leaving him, he disabled Demuchus, Philetor’s son, with a blow from his spear in the knee, then struck him with his long-sword and robbed him of life. Then he hurled the sons of Bias, Laogonus and Dardanus, from their chariot, one with a spear-cast the other with his sword in close combat. Tros, Alastor’s son, ran to clasp his knees, begging, in his folly, to be spared, to be captured alive, for Achilles to take pity on a youth of his own age, and not kill him! He should have known Achilles’ harshness, no soft heart or tender mind had he, fierce in his fury. As Tros in his eagerness tried to clasp the warrior’s knees, Achilles pierced his liver with the sword, and spilled it, the dark blood drenching his body, darkness enfolding him as he breathed his last. Then Achilles struck Mulius with his spear, the spear-blade passing through his head from ear to ear. Next he killed Echeclus, son of Agenor, striking him on the head with the sword, his blood heating the blade, dark death and remorseless fate veiling his eyes. Then he pierced Deucalion’s arm with the bronze spear-point, where the sinews meet the elbow joint, and Deucalion trailing the spear waited on death. Achilles struck his head from his neck, sending the helmeted head flying. The marrow welled from the vertebrae, and the corpse fell to the ground. Achilles ran after Rhigmus, the peerless son of Peiros, from fertile Thrace. He struck him in the centre of his belly with his spear, transfixing him, and he fell from his chariot. Then Achilles toppled Areïthous, Rhigmus’ squire, striking him in the back with his spear, as the charioteer wheeled the panic-stricken horses.

Achilles ranged everywhere with his spear, like a conflagration racing through the deeply-wooded gullies on a parched mountain-side, its whirling flames driven by the wind through the close-packed trees, and with the force of a god he beat down those he killed till the black earth ran with blood. Proud Achilles’ horses trampled dead men and shields alike as grain is swiftly trampled under the feet of the broad-browed bellowing oxen a farmer yokes to tread white barley on a stone threshing floor. The axle and the chariot rim were black with blood thrown up by the hooves and the wheels as the son of Peleus pressed on to glory, his all-conquering arms spattered with gore.