Homer: The Iliad

Book XV

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2009 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Bk XV:1-77 Zeus prophesies the course of the war

- Bk XV:78-148 Hera executes Zeus’s orders

- Bk XV:149-219 Iris carries Zeus’s message to Poseidon

- Bk XV:220-280 Apollo revives Hector

- Bk XV:281-327 Thoas rallies the Greeks

- Bk XV:328-378 Apollo and Hector drive the Greeks back to the ships

- Bk XV:379-457 The fighting at the ships

- Bk XV:458-513 Hector and Ajax rally their men

- Bk XV:514-564 Close combat

- Bk XV:565-652 Hector reaches the ships

- Bk XV:653-746 Ajax stands firm

BkXV:1-77 Zeus prophesies the course of the war

When the fleeing Trojans had re-crossed the palisades and trench, losing many men to the Danaans, and reached the chariots, they halted terror-stricken, pale with fear. Then Zeus woke, beside Hera of the Golden Throne, on the summit of Mount Ida. Leaping to his feet he stood and watched the Trojan rout, the Argives behind in hot pursuit. He saw Poseidon among the Greeks, and Hector lying in the dust while his friends sat close around him.

Hector was breathing painfully, from that blow delivered by Ajax by no means the weakest of the Greeks, dazed in mind, and vomiting blood. The father of gods and men, seeing him, felt pity, and with a dreadful glance he turned on Hera: ‘You are incorrigible, it’s your artful wicked ways that led Hector to leave the fight, and his men to flee. You should be first to reap the rewards of your wretched wiles, and feel my whip. Remember when I hung you on high, two anvils suspended from your feet, bands of unbreakable gold about your wrists? You hung there in the air among the clouds, and the other immortals on lofty Olympus, could not approach to set you free, despite their indignation. Whichever of them tried I caught them, hurled them from my threshold, till they fell to earth, their strength all gone. Yet even that failed to ease my endless heartache for godlike Heracles. You and the North Wind, whose blasts you suborned, drove him over the restless sea, part of your evil scheme, and carried him to many-peopled Cos. I saved him, brought him from there to horse-grazing Argos, after his great labours. I remind you of it, so you might end your intrigues, and see how little help to you will be our love-making and that bed where we lay together after you came from Olympus and tricked me.’

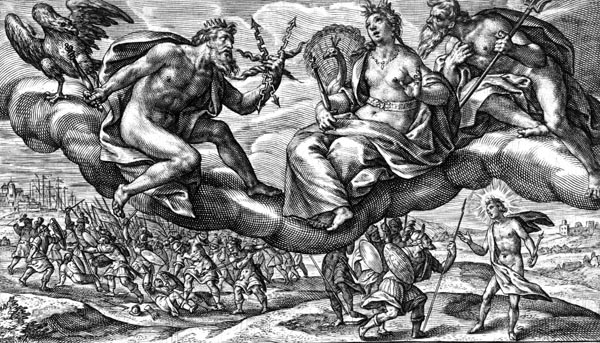

‘Zeus is awakened’ - Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1613

Ox-eyed Queen Hera shuddered at his words, and she replied with soothing words: ‘May Earth, and the broad sky above, and the plunging waters of Styx by whom the blessed gods swear their greatest most solemn oath, and your own sacred head, and our own marriage bed, by which I would never perjure myself, may they all bear witness that it is not by my will that Poseidon, Earth-Shaker, works ill on Hector and the Trojans, and aids their enemy. I can only think he obeys his own heart’s prompting, seeing the Greeks in trouble and pitying them. I would counsel even him to follow your direction, Lord of the Dark Cloud.’

The father of gods and men smiled at her words: ‘Hera, my ox-eyed Queen, if you really choose to support me in council from now on, then even though Poseidon thought otherwise, he’d be inclined to follow our wishes promptly. If what you say is truly and sincerely said, go to the immortal gods and summon Iris, and Apollo the Archer. She must visit the army of bronze-clad Greeks, and tell Poseidon to leave the field and go home. Meanwhile Phoebus Apollo must breathe new strength into Hector, make him forget his heart-troubling pain, rouse him to fight, and drive the Achaeans back once more. Once he has them panicking like cowards, they will run and die beside the benched ships of Achilles, son of Peleus. He will send out his friend Patroclus, who will slay many a fine young man, among them noble Sarpedon my son, but great Hector will kill him in turn with his spear, under the walls of Troy. Then in revenge for Patroclus, noble Achilles will kill Hector. Thereafter I shall let the Trojans be driven steadily from the ships, remorselessly, until the Greeks, advised by Athene, take Troy. But my wrath will be unabated till then, and no other immortal shall help the Greeks, till Achilles’ wishes are fulfilled, in accord with the promise I made with a nod of my head, that day that divine Thetis clasped my knees, and begged me to honour her son, Achilles, sacker of cities.’

BkXV:78-148 Hera executes Zeus’s orders

The goddess, white-armed Hera, listened and obeyed, speeding from Mount Ida to lofty Olympus. Like the swift mind of a man who has travelled widely, whose deep thought prompts many wishes, saying to himself: ‘I wish I were there, or there,’ as swiftly Queen Hera flew in her eagerness. Reaching high Olympus, she found the immortals gathered in Zeus’s palace. On seeing her they rose, and pledged her in welcome. Passing by the others, she accepted a cup from fair-faced Themis who ran to meet her, saying: ‘Hera, what prompts your return, why so distraught? Zeus must have frightened you, your own husband.’

White-armed Hera replied: ‘Don’t ask, dear Themis. You know what he’s like, so harsh and unyielding. Let the gods begin their feast equably, and you and all the immortals in these halls shall hear the devious actions Zeus intends. If any still sit down to feast with joy in mind, well, I can tell them it will neither please them all, nor every mortal.’

With this Queen Hera took her seat, and throughout the hall the gods looked troubled. Though her lips formed a smile, her forehead above her dark brows was tight with indignation: ‘What fools we are to quarrel with Zeus! We are eager to get at him and thwart his wishes with words or action. But he sits there, unconcerned, indifferent to us, repeating that he’s unquestionably the greatest and strongest of immortals. So be content with whatever nastiness he visits on each of us. Even now he deals Ares a blow, since his dearest son has died in battle, Ascalaphus, whom Ares claimed as his own.’

Ares groaned at this, and struck his sturdy thighs with the flat of his hands: ‘Gods of Olympus, don’t blame me if I go to the Achaean ships right now, and avenge my son, even if Zeus should strike me with his lightning bolt, and I lie in blood and dust among the corpses.’

With this, ordering Terror and Panic to harness the horses, he donned his gleaming armour. Then a greater and angrier quarrel between Zeus and the immortals would have broken out, had Athene, fearful for them all, not left her chair, run to the threshold and snatched Ares’ helm from his head, the shield from his shoulders, and the bronze spear from his great hand, throwing them down and pouring words of rebuke on the angry Ares: ‘Madman, your mind’s astray, you’d be doomed! Why were you given ears to hear? Where’s your sense and self-restraint? Did you not listen to what white-armed Hera said, straight from Olympian Zeus? Do you want a greater measure of sorrow, to be driven back to Olympus, in anguish, and sow the seeds of suffering for us all? He will quit the brave Trojans and the Greeks, instantly, and head to Olympus to wreak havoc. He’ll lay hands on the guilty and the innocent too. So, I beg you, swallow your anger. Many a man greater than Ascalaphus in strength, more skilful in warfare, has died and many must die still. It would be hard for us to save every man’s sons and lineage.’

So saying, she made the angry Ares take his seat again, while Hera called Apollo and Iris, the gods’ messenger, from the hall and spoke to them winged words: ‘Zeus asks that you both go swiftly to Ida, and when you see him there, face to face, then do whatever he urges you to do.’

BkXV:149-219 Iris carries Zeus’s message to Poseidon

Having spoken, Queen Hera returned to her seat, while the pair sped away on their errand. They reached Ida of the many streams, mother of the wild creatures, where Zeus, of the far-echoing voice, was sitting on the top of Gargarus, wreathed in a scented mist. They met the Cloud-Gatherer, face to face, and he was pleased to see how swiftly they had obeyed his dear wife’s order. He spoke to Iris first: ‘Off with you, now, swift Iris, and give this message to Lord Poseidon, exactly as I speak it. Tell him to cease from war and fighting, and return to the gods on Olympus, or to the glittering sea. If he will not obey, choosing to ignore my words, let him think deeply on it, for strong as he is he dare not face my anger, since I am the more powerful and his elder, even though pride prompts him to claim himself my equal, I whom the other gods fear.’

So he spoke, and wing-footed Iris obeyed, speeding from Ida’s hills to sacred Ilium. As fast as the snow or frozen hail that falls from the clouds driven by a northerly gale, swift Iris flew, found Poseidon, the great Earth-Shaker, the dark-haired Encircler of Earth, and delivered the message.

Poseidon was enraged: ‘He may be powerful, but this is arrogance, to try and restrain me against my will, and threaten force, I who share equal honour with himself. Three brothers are we, sons of Cronos and Rhea, Zeus and I and Hades, Lord of the Dead. The world was divided in three, and each received his domain. When the lots were cast, I won the grey sea for my home forever, while Hades had the dense darkness beneath. Zeus may have taken the wide heavens, the cloud and air, but Earth and lofty Olympus are common to us all. So I will not submit to Zeus’s will. Despite his power, let him stay quietly in his own third. And let him not try to frighten me, as if I were a coward. Let him menace his sons and daughters with angry words, he begot them and they are forced to listen to his urgings.’

Then Iris, swift as the wind, answered him: ‘Is this the answer, dark-haired Encircler of Earth that I am to take to Zeus, these harsh and stubborn words? Will you not change your mind, as the minds of the noble may be changed? You know how the Furies ever support the first-born.’

Poseidon, Earth-Shaker, replied: ‘Dear Iris, you are right to say so, and it is good when a messenger shows wisdom. But such is the dreadful feeling in mind and heart when a wrathful god decides to rebuke one of his peers, whom Fate has made his equal. Yet I will yield for now, despite my indignation. In my anger though, I’ll add this warning. If Zeus ignores me, and ignores Athene, chaser of the spoils, and Hera, Hermes, and Lord Hephaestus too, and spares lofty Ilium, prevents its ruin, and denies the Argives glory, tell him there’ll be an irreparable breach between us.’

With this, the Earth-Shaker abandoned the Argives, headed for the shore and plunged into the depths, leaving the Greeks to bemoan his absence.

BkXV:220-280 Apollo revives Hector

Now Zeus, the Cloud-Gatherer, issued his request to Apollo: ‘Dear Phoebus, Poseidon, the Earth-Shaker and Encircler, has withdrawn to the glittering waves, to escape my wrath. It is better for both that he yielded to my power despite his indignation, before those gods beneath the world with Cronos heard our quarrel, which could not end without much toil and sweat. Go to bronze-clad Hector, and as you go take my tasselled aegis, and shake it fiercely over the Greek army to instil fear. Then, Far-Striker, help noble Hector and fill him with enduring strength until the Greeks are driven back to the ships and the Hellespont. At that time I will ensure by word and deed that the Greeks are given respite from the toils of war.’

Apollo obeyed his father’s words, speeding from Ida’s heights, like a swift falcon, the dove-slayer, swiftest of birds. Noble Hector, warlike Priam’s son, was only now recovering, no longer lying flat but sitting upright, conscious of his friends around him. His sweating and panting had ceased now aegis-bearing Zeus wished to revive him. Apollo the Far-Striker approached saying: ‘Hector, Priam’s son, why are you sitting here in this state, far from the lines? Are you badly hurt?’

Hector of the gleaming helm, replied in weakened tones: ‘What god are you, mighty one, who needs to ask that of me? Surely you know that as I slaughtered his men by the sterns of the Greek ships, Ajax of the loud war-cry struck me on the chest with a great stone, and stopped me in mid-flight. I thought in truth this very day I would gasp away my life, and gaze on the dead in the House of Hades.’

‘Lift your spirits,’ Lord Apollo, the Far-Striker, replied: ‘Phoebus Apollo of the Golden Sword is here, sent from Ida by the son of Cronos as a mighty helper to stand beside you and defend you, one who has long protected you and your lofty citadel alike. Come, order your host of charioteers to send their swift horses against the hollow ships, while I go on ahead to smooth the path for their chariots and rout the Greeks.’

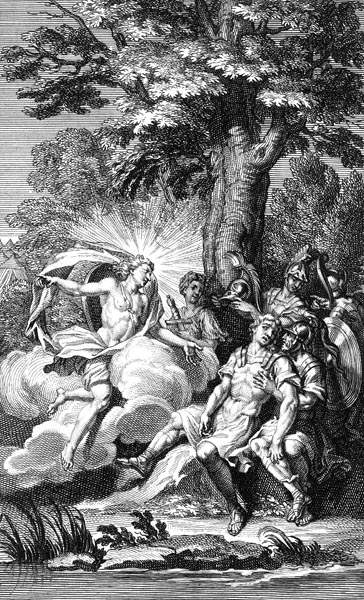

‘Apollo gives Hector new strength’ - Workshop of Bernard Picart, 1710

With this, he breathed enduring strength into the Trojan leader, who at the voice of the god urged on his charioteers, climbing to his feet and moving lightly, like a stable-fed stallion, who has had his fill, and breaks the halter and gallops over the fields in triumph, to bathe in the lovely river as is his wont, tossing his head while his mane streams over his shoulders, glorying in his power as his strong legs carry him to the pastures, the haunts of mares.

The Greeks had been pushing forward in formation, cutting with swords and thrusting with double-edged spears. Now like a set of villagers who chase a wild goat or a stag with dogs till it finds refuge on some high crag, or deep in a dark thicket, and they lose its trail, only to find a shaggy lion, disturbed by their clamour, blocking their path, putting them to flight despite their former zeal, the Danaans were gripped by fear and their hearts sank, seeing Hector once more marshalling his men.

BkXV:281-327 Thoas rallies the Greeks

Then Thoas, Andraemon’s son, spoke up among the Greeks. He was the finest of the Aetolian warriors, an expert with the javelin, but a good man in a close fight too, while few of the Greeks were more persuasive when the younger men debated in the Assembly. Now with the best of intentions he addressed them: ‘What marvel is this I see? Hector recovered, and escaped from death! Everyone in his heart hoped that he had perished from Ajax’s blow. But some god has protected and saved that slayer of Greeks, to carry on killing. He would not be leading the front rank so eagerly if Zeus the Thunderer did not wish it. But listen, and do as I advise. The main body of men must withdraw to defend the ships, but we who consider ourselves the pick of the warriors, must stand against him, hoping to keep him off at spear-point. For all his eagerness, I think he’ll lack the courage to plunge amongst us.’

They approved and followed his suggestion. Those around Ajax and Lord Idomeneus, around Teucer, Meriones and Meges, peer of Ares, gathered the best men and marshalled them opposite Hector and the Trojans, while the main body of men retreated to the ships.

Then the Trojans closed ranks and pushed forward, behind Hector who strode ahead, Phoebus Apollo beside him, shoulders veiled in mist, holding the powerful aegis with its tasselled fringe, gleaming bright and deadly, that Hephaestus the smith made for Zeus to send mortals fleeing. With the aegis in his hand, Apollo led them onwards.

The Argives packed together awaited the onslaught, as the war-cries rose loud from either side, arrows leapt from the bow, and a host of spears hurled by bold arms lodged in the bodies of agile young warriors, or more often fell short before striking white flesh, and fixed themselves in the earth mid-way, disappointed of their quarry.

While Phoebus Apollo held the aegis unmoving in his hand, the shower of missiles continued and men fell. But the moment when he looked the horse-taming Danaans in the face, shaking the aegis and giving a mighty shout, their hearts stopped, and their blind courage ebbed. Driven in confusion, like a herd of cattle or a vast flock of sheep surprised in the depths of night, the herdsman being absent, by a pair of wild beasts, so the Achaeans fled in rout robbed of all fight, for Apollo had sent panic among them, granting Hector and Troy the glory.

BkXV:328-378 Apollo and Hector drive the Greeks back to the ships

As the Greek line broke, the Trojans picked them off one by one. Hector killed Stichius and Arcesilaus, the former a leader of the bronze-clad Boeotians, the latter a trusted friend of brave Menestheus, while Aeneas slew Medon and Iasus. Medon was a natural son of godlike Oïleus, so a brother to Ajax the lesser, and came from Phylace, not his native land, exiled for killing a kinsman of his step-mother Eriopis, wife to Oïleus. Iasus was an Athenian leader, the son of Sphelus son to Bucolus. Polydamas killed Mecisteus, Polites killed Echius as they clashed, and Clonius fell to noble Agenor. Deiochus fled with the other leaders, but Paris struck him from behind at the base of the shoulder, and drove the bronze clean through.

While the Trojans stripped the dead of their blood-stained armour, the Greeks were flung back on their trench and palisade in confusion, and forced to retreat behind the wall. Now Hector called aloud to the Trojans: ‘Leave the armour, and push for the ships. Whoever holds back I’ll put to death where he stands, his kin shall not grant him a share of the funeral flames that are his due. Instead, the dogs can rend him before Troy.’

With that, he gave a downward flick of his arm, and whipped his horses on, his cry ringing out along the Trojan ranks. Echoing his shout, they lashed their teams forward alongside his, with a mighty clamour. Phoebus Apollo easily kicked down the banks fronting the trench, and piled up a long causeway inside, wide as a spear-cast made by a man testing his strength. Over it they poured, rank on rank, following Phoebus and the precious aegis. And Apollo toppled the Achaean wall just as easily, like a child scattering sand that builds a mock castle in play then ruins it with feet and hands. So, you, Phoebus, God of the Bow wrecked what the Greeks had laboured and toiled so long to build, then routed them.

Once more the Greeks halted by the ships, and called to each other, and raising their hands to the sky prayed fervently. None more so than Gerenian Nestor, warden of Achaea, stretching out his arms to the unseen stars: ‘Father Zeus, if ever we burnt the fat thigh of an ox or sheep in sacrifice to you, back in the wheat-lands of Argos, praying for safe return, and you nodded your promise, remember it now, Olympian, save us from the pitiless hour of doom, don’t let the Trojans vanquish us like this.’

So he prayed, and Zeus the Counsellor thundered in reply, answering the prayer of Neleus’ aged son.

BkXV:379-457 The fighting at the ships

But the Trojans, hearing aegis-bearing Zeus’s thunder, re-doubled their attack on the Argives, their minds filled with battle. With a great roar, they poured across the wall, like a billow out at sea, driven by the force of the wind that swells the waves, sweeping over a ship’s side. They drove their horses through the gap then fought in close combat by the ships, wielding their double-edged spears, fighting from the chariots, while the Greeks clambered high on the sterns of the black ships and used their long pikes, jointed poles tipped with bronze, which lay to hand on board.

Now, while the Greeks and Trojans were still fighting at the wall far from the swift ships, Patroclus sat in friendly Eurypylus’ hut, diverting him with talk, while spreading ointments on his cruel wound to ease the dark pain. But when the Trojans overran the wall, and he heard the Greeks shouting as they fled, he groaned and slapped his thigh with his hand, saying anxiously: ‘Eurypylus, I must not stay, despite your need, the conflict is growing. Your squire must see to you while I run to Achilles and urge him to fight. Who knows but with a god’s aid I might persuade him, stir him into action? A persuasive friend may do some good.’ He was already on his way, as he finished speaking.

The Achaeans still stood firm, thwarting the enemy advance, yet unable to drive the Trojans back despite their smaller numbers, while the Trojans in turn could not break the Greek lines and push in among the huts and ships. The conflict and the war were balanced on a knife’s edge, the battle-front stretched taut as a carpenter’s line along a timber in the hands of a skilled shipwright trained in his craft and guided by Athene.

The Trojans attacked the ships at random, apart from Hector who made straight for great Ajax. The two toiled on fighting for the one ship, Ajax unable to drive Hector back since a god had brought him there, while Hector could not move Ajax and set the ship on fire. Great Ajax in casting his spear however struck Caletor, son of Clytius, in the chest, as he carried a burning brand towards the ship. He fell with a thud and the torch fell from his hand. Hector, seeing his cousin fall in the dust by the black ship, called aloud to his friends and allies: ‘Trojans, Lycians, and you Dardanians that love close fighting, hold your ground where we stand, and save Caletor, or the Greeks will strip his armour from him, where he lies beside the ships.’

With that, he hurled his gleaming spear at Ajax, missing him but hitting Lycophron, son of Mastor, a squire of Ajax from Cythera, who joined his service after killing a man in that sacred isle. Hector’s sharp bronze blade struck him on the head above the ear where he stood beside Ajax, and he fell from the ships stern to the ground, landing on his back in the dust, his limbs loosed in death. Ajax shuddered and spoke to his step-brother: ‘Brave Teucer, a loyal friend is lost, Lycophron, Mastor’s son, who since he came to us from Cythera we have honoured with our parents. Proud Hector has killed him. Where are your swift deadly arrows, and the bow that Phoebus Apollo gifted you?’

Teucer, hearing, ran to stand next to him gripping his curved bow and his full quiver then fired repeatedly at the Trojans. He first struck Cleitus, Peisenor’s noble son, friend to Polydamas, son of Lord Panthous. He was holding the reins, grappling with the horses, since he had driven in among the Greek battalions as they fled, to support Hector and his comrades. Now evil came to him in a moment, from which no friend however zealous could save him, the fatal arrow struck the back of his neck, and he toppled from the chariot. The horses shied and ran, the empty chariot rattling behind them. Noble Polydamas was quick to see, and first to halt them, handing them to Astynous, son of Protiaon, telling him to keep them near at hand, and watch his movements closely as he returned to the front.

BkXV:458-513 Hector and Ajax rally their men

Then Teucer aimed an arrow at bronze-clad Hector, and had he struck and killed him in his pomp that would have ended the battle by the ships. But his action did not escape Zeus’s watching mind. He protected Hector, robbing Teucer of the glory, by snapping the deftly twisted cord of his peerless bow, at the moment of firing, so the arrow tipped with solid bronze went awry, and the bow leapt from his hand. Teucer shuddered, saying to his step-brother: ‘There! Some god is ruining our every action. He breaks the newly twisted bowstring I bound tight this morning, to withstand the hail of arrows I intended, and strikes the bow from my hand.’

Great Telamonian Ajax replied: ‘Well, my friend, then let your bow and quiver lie, since some hostile god renders them useless, pick up a shield and grasp your long spear, tackle the Trojans and urge on the men. They will not take our ships without a fight, even though they conquer: to battle, then!’

At this, Teucer set his bow down in the hut; slung a four-layered shield over his shoulder, set a fine helm with a horsehair crest on his sturdy head, the plume nodding threateningly; grasped a powerful spear tipped with sharp bronze, and set out at a quick run, to rejoin Ajax.

Now when Hector realised Teucer’s bow had failed, he shouted aloud to the men: ‘Trojans, Lycians and you Dardanians, who like close combat, be men, my friends, and show your boundless courage among the hollow ships, for I saw Zeus foil their master-archer’s shot. Easy to see the help Zeus gives to mortals, how he both grants men greater glory, and harms those to whom he denies his aid, as now he helps us and weakens the Greeks. Mass together tightly by the ships, and if any man, overtaken by death and fate, is struck by a missile or the thrust of a blade, so be it. There’s no dishonour in dying while fighting for one’s country. If the Greeks sail for their native land, his wife and children will be safe, his house and land secure after him.’

So Hector roused their courage and gave them strength, while Ajax for his part called to his men: ‘Shame on you, Argives: defend the ships, and save them or die trying. If Hector of the glittering helm takes the fleet, do you think a single man of you will reach his home again? Listen as, in his fury, he urges his men on to burn our ships? It is not to the dance he summons them, but to battle. There is no better plan for us than this, to bring our strength and weapons to bear on them, hand to hand. It is better to win life, once and for all, or die, than be stifled by the ships, by lesser men, in this vain and fatal struggle.’ So he roused their courage and gave them strength.

BkXV:514-564 Close combat

Now Hector killed Schedius, Perimedes’ son, a leader of the Phocians, while Ajax killed Laodamas, noble son of Antenor, an infantry commander, and Polydamas felled Otus of Cyllene, a friend of Meges, Phyleus’ son, a leader of the proud Epeians. When Meges saw this he launched himself at Polydamas, who swerved aside so Meges missed, Apollo refusing to see the son of Panthous fall in the front line, and instead the spear-thrust struck Croesmus full in the chest. He fell with a thud and Meges began to strip him of his armour. But Dolops, the bravest son of Lampus, son of Laomedon, and a skilled spearman, used to fierce combat, thrust at close quarters with his spear and pierced the shield of Phyleus’ son. Meges’ metal-plated corselet saved him, the one Phyleus had brought from Ephyre and the River Selleïs, where his host King Euphetes had gifted it to him to wear in action and protect him. Now it saved his son from death.

Meges countered, a thrust of his sharp spear striking the crown of Dolops’ bronze helm with its horsehair crest, shearing away the horsehair plume, bright with scarlet dye, which fell in the dust. As Meges fought Dolops, hoping for victory, warlike Menelaus came to his aid, and from the flank, unseen by Dolops, cast a spear piercing his back, the point passing through swiftly, and exiting savagely through the chest. He fell headlong and his enemies ran in to strip the bronze armour from his shoulders.

Hector called out to Dolops’ kinsmen, especially Hicetaon’s son, sturdy Melanippus. Before the war, he lived at Percote, grazing his shambling cattle, but when the Greeks arrived in their curved ships, he returned to Ilium, earning a prominent place among the Trojans, living in Priam’s palace, and honoured by Priam with his own children. Hector reproached him now: ‘Melanippus are we to hold back like this? Has your heart no feeling for your dead kinsman? See how they tear at Dolops’ armour. Follow me, we must close with these Argives, either we kill them, or they’ll take lofty Ilium, and slaughter all our people.’ With this, he charged and Melanippus, that godlike warrior followed.

Great Telamonian Ajax meanwhile was urging on the Argives: ‘Be men, my friends and, in this great combat, fear to be shamed in your own eyes and those of others. Where men fear shame, more survive than are killed. But there is neither glory nor safety in flight.’

BkXV:565-652 Hector reaches the ships

So he spoke, and though the Argives were already eager to drive back the enemy, they responded to his words, and ringed the ships with a wall of bronze countering the Trojans urged on by Zeus. Now Menelaus of the loud war-cry spurred on Antilochus: ‘You are the youngest, quickest and boldest of us, Antilochus why not make a foray and wound some Trojan?’

Having roused the man, Menelaus swiftly retreated, while Antilochus ran out from the front rank, and quickly glancing round threw his bright spear, the Trojans shrinking back from his throw. Nor did his weapon fly in vain, striking proud Melanippus, Hicetaon’s son, on the chest by the nipple, as he joined the fight. He fell with a thud, and darkness shrouded his sight. Like a hound leaping at a wounded fawn, caught by a hunter’s careful shot as it fled from its lair, loosing its limbs, so stalwart Antilochus sprang at you, Melanippus, to strip away your armour. But noble Hector saw it all, and charged through the ranks to the attack. Antilochus turned and ran, his swift feet carrying him as speedily as a wild creature fresh from causing harm, killing a dog, or a herdsman beside his cattle, then fleeing before a vengeful crowd can gather. And as that son of Nestor fled before Hector, the Trojans raised a deafening cry and sent a hail of missiles after him, until he reached the ranks of his comrades where he once more turned to take his stand.

Now the Trojans, like ravening lions, charged towards the ships, fulfilling the will of Zeus, who roused their courage and spurred them on, as he shook the hearts of the Greeks and robbed them of all glory: that he gave to Hector, son of Priam, so he might shroud the beaked ships in un-resting towers of flame, and answer fully Thetis’ fateful prayer. Zeus the Counsellor waited then for the glare of burning timbers, determined that from that instant he would grant glory once more to the Greeks, and see that the Trojans were driven from the ships.

With this intent he spurred the already eager Hector on, and Hector raged like Ares, god of the spear, or like a mountain fire working its destruction among the close-packed trees. With foaming lips, eyes blazing beneath lowering brows, he fought, and the very helm on his head shook on his temples, for the power of divine Zeus was his shield, and granted him the honour and the glory, alone among the host of warriors. Though brief was the life remaining to him, for even now Pallas Athene was hastening that fatal day when he would fall to Peleus’ mighty son.

Now he had one thought only, to shatter the Greek line, testing it wherever he saw the best-armed warriors tightly clustered. Yet eager as he was he could not break through, for the Greeks stood firm as a wall, like a vast sheer cliff facing the grey sea unshaken by howling gales and towering breakers. So the Greeks held steady and would not flee.

At the last, gleaming with fire, Hector burst among them and laid about him, as under cloud a powerful wind-swollen wave breaks over a speeding ship, drenching it in foam, while the gusts roar in the canvas, and the crew shudder with fear, driven along a hair’s breadth from destruction, so Hector launched himself at the Achaeans striking panic in their hearts.

He fell on them with savage intent, like a lion attacking a vast herd grazing in some water-meadow, their herdsman, unskilled in driving a cattle-killer from a sleek heifer’s carcase, pacing at front or rear, keeping close to them, so leaving the lion to strike in the centre and take a heifer, scattering the rest in terror. So the Greeks fled to a man, before Hector and Father Zeus, when Hector killed Periphetes of Mycenae, beloved son of Copreus, that Copreus whom King Eurystheus sent with a message to mighty Heracles. The son was better than his father in every way, as runner and warrior, and one of the best minds of Mycenae, and his death gave the greater glory to Hector. As he fled, he tripped over the rim of his own long shield that reached to his feet, a defence against javelins, and stumbling fell backwards, his helmet clanging loudly at his temples as he landed. Hector seeing this, swiftly approached and drove a spear through his chest, killing him in the midst of his comrades, beyond their help despite their horror, given their deep dread of noble Hector.

BkXV:653-746 Ajax stands firm

Now the Greeks fell back on the ships, retreating behind the outermost row, those that been drawn highest up the shore, but still the Trojans came on. Then the Argives were forced back even further, but re-grouped beside the huts, held together by shame and fear, calling ceaselessly to one another. Gerenian Nestor, Warden of Achaea, exhorted them the loudest, imploring each man, in his parents’ names, to stand firm: ‘My friends, be men, and fear to be shamed before the others. Think of your wives and children, your parents, living or dead, and remember all you own. For the sake of those far off, I beg you, stand here, and do not flee.’

With this he filled their hearts with courage, and Athene cleared the fog of war from their eyes, and flooded them with light from both sides, that of the ships and that of the battle lines. And all saw Hector, of the loud war-cry, and all his men, those at the rear as well as those who fought by the swift ships.

Proud Ajax could not bear to stand with the rest of the Achaeans, but strode up and down over the decks of the ships, wielding a long-pike in his hands, a pole jointed with metal rings, twelve feet long. As a skilled horseman with a picked team of four, who rides them on a highway from the plain to the big city, and sure of himself leaps from horse to horse as they gallop on, to the wonder of many, so Ajax ranged with long strides from ship to swift ship across the decks, his shouts rising skywards as he called to the Greeks with tremendous cries to defend their ships and huts.

Hector too could not rest among the ranks of mail-clad Trojans. Like a tawny eagle swooping at a flock of birds feeding by a river, wild geese, cranes or long-necked swans, he rushed straight at some dark-prowed ship while Zeus’ mighty hand pushed him on from behind, and spurred the Trojans to follow.

So once more, the ships saw bitter conflict. You would have thought both sides still fresh and unwearied, so fiercely did they fight. And as they fought these were their thoughts. The Achaeans felt they could not escape, and would be killed, while the Trojans hoped, deep within, to fire the ships and slay the Greeks. Such were their respective expectations as they clashed.

Hector, at last, grasped the stern of a sea-going ship, a fine vessel a swift one on the deep, that had brought Protesilaus to Troy, yet failed to bear him home again. Round it the Greeks and Trojans slaughtered one another in close combat, no longer fighting from afar with arrows and javelins, but hand to hand, united in their purpose, with keen battle-axes and hatchets, with long swords and double-edged spears. Many a lovely blade, its hilt bound with dark thongs, fell from their hands, or slipped from their shoulders as they fought, and the earth was black with blood.

But once Hector had gripped the ship’s stern he would not loose his hold, but clung to the stern post, shouting to the Trojans: ‘Bring fire, and give the war-cry all together, now Zeus grants us a victory that pays for all. Now we take these ships that sailed here in defiance of the gods, to cause us suffering. The Elders’ cowardice contributed, holding the army back when I was eager to fight here at their sterns. But if Zeus, the far-echoer, dulled our senses then, it is he himself who commands now and drives us on.’

With this his men pressed the Argives harder. Even Ajax himself, thinking he would die beneath a hail of missiles, yielded and gave way a little, retreating from the after-deck of the shapely vessel some way along the seven-foot high connecting bridge amidships. There he stood, alert, with his pike fending off any Trojan who approached the ship with a blazing brand, and urging the Greeks on ceaselessly with mighty shouts: ‘Friends, Argive warriors, you slaves of Ares, be men, and think on furious courage. There is no other help for us, no stronger wall to ward off disaster, no city with its ramparts to hide inside, no other army to turn the flow of battle. Here on the plains of Troy are we, our backs to the sea facing the mail-clad Trojans, far from our native land. So in the strength of our own hands is our salvation, and there can be no surrender in this fight.’

With this cry, he thrust his spiked pole furiously time and time again at the foe, and there Ajax waited for any Trojan who longing to delight Hector his inspiration, ran at the hollow ships with blazing brand. Ajax would wound each man with a thrust of his long pike, and disabled twelve men in this way in the close encounter by the ships.