Théophile Gautier

Constantinople (1852)

Part V: Hagia Sophia, The Seraglio, The Atmeidan

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 21: The Charlemagne – The Fires.

- Chapter 22: Santa Sophia – The Mosques.

- Chapter 23: The Seraglio (The Topkapi Palace).

- Chapter 24: The Bosphorus Palace (Dolmabahçe Palace) – The Sultan Mahmud Mosque – The Dervish.

- Chapter 25: The Atmeïdan.

Chapter 21: The Charlemagne – The Fires

The arrival of the Charlemagne had long been talked about, and was so awaited an event, that she had become something of a chimerical vessel, an Argo (Jason’s ship in the Greek myth) or a Flying Dutchman (the legendary ghost ship), when, one fine morning, all unheralded, a superb three-decker flying a tricolour flag was seen hovering before the Tophane harbour, at the entrance to the Golden Horn, bearing on her prow an imperial bust, and on her stern, writ in gold letters, her name: Charlemagne. How had she come there? By what magic had she found herself in the midst of the roads? On her sides marked by a triple line of cannon embrasures, there was no sign of paddle-wheel drums; on her deck, no appearance of a funnel, and yet her yards revealed no furled and tied sails; at her mastheads, not a flag floated on the breeze: it was incomprehensible. Among the folk on shore, the rumour spread that she was an enchanted vessel manned by the demonic Djinns and Afrits.

Diplomatic difficulties, raised, it is said, by the Austrians and Russians had opposed the entry of the Charlemagne into the strait, which no ship of the line can enter without a firman (Imperial decree). The firman was finally granted, and, to further legitimise the presence of such a ship in the waters of the Golden Horn, the Marquis de Lavalette (Charles Jean Marie Félix), the French ambassador, boarded the Charlemagne; which action smoothed things over. The Charlemagne was French; and thus, the curiosity of Mahmud, the Kapudan-Pasha (Ottoman Admiral-of-the-Fleet), was satisfied, he wishing to view a mixed propulsion vessel (steam and sail).

The caiques prowled timidly around this marine colossus like herrings round a whale, fearing a blow from tail or fin; finally, some decided to accost its black sides, and emboldened visitors hoisted themselves up via the rudder-lines. I was one of them. As I set foot on deck, the first face I saw was that of an acquaintance of mine. Giraud (Pierre François Eugène Giraud, the artist) smiled at me, friendly behind his red moustache, and shook his thick curly mane in my honour; I answered him with a ‘salam alaikum’ in the style of Covielle in the special ceremony in Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme (the play by Molière; Covielle, a variant on Coviello, the commedia dell’arte character, is a servant in the play), and thus in a satisfyingly Oriental manner. I had previously experienced the good fortune of meeting Giraud, in my travels, an amiable and witty companion if ever there was one; I had already had that happiness in Spain; I had hastened to show him all the wretched districts, all the abominable alleys, that are the despair of admirers of the Rue de Rivoli, and the eternal joy of painters. I then went to pay my respects to the ambassador, whom I had the honour of knowing a little, and who received me with kindness; then Giraud introduced me to his friends the officers, and I was taken to see all three decks of the ship, a peregrination which always surprises, even when it is not new to you; for a warship is one of the most prodigious achievements of human ingenuity: a swarm of twelve to thirteen hundred men, eat, sleep, and manoeuvre, without the least disorder, in a narrow space filled by eighty cannons, a powerful steam-engine as tall as a two-story house, a powder-hold, a coal-hold, a galley, and provisions for several months. It is at once a city, a fortress, and an engine-house. Dutch housewives who think themselves mistresses of cleanliness are but infamous scullery-maids compared with sailors, whom no one can match in the arts of sweeping, washing, sanding, varnishing, and granting a lustre to every object. Not a stain on the planking, not a spot of rust or verdigris on the iron or copper; everything shines, everything gleams: the whole sparkles with an ever-fresh glow, the mahogany of an English table prepared for morning tea is certainly less clean than the deck of a ship. ‘One could eat soup from it,’ as the vulgar but lively expression says; and amidst the rigging, all those ropes, which each have their name, stretch immaculately, like a spider’s web, without a single knot, or tangle: they move and slide on their pulleys, whenever needed, with admirable order and precision.

I returned to shore, where discussion continued regarding the Charlemagne. Its propeller, which was completely submerged, its funnel, the sections of whose cylinder retracted like the tubes of a spyglass, granted it all the appearance of a sailing ship, and it was only later, when it made an excursion to Therapia, that the amazed caïdjis were forced to accept, on seeing smoke gushing forth from the piping below decks as if by magic, and a foaming wake forming behind the stern that made their frail boats wobble, that it was indeed a steamboat.

Next day, the ambassador came ashore with official ceremony, and was received on land by the two commercial representatives, and what, when abroad, is termed the ‘nation’, that is to say all the French nationals present in Constantinople. I took my place amidst the ranks of the procession, and we accompanied the ambassador, the Marquis de la Valette, to the embassy palace, situated in the main street of Pera. The ceremony was quite moving: a handful of men lost amidst an immense city, in which a different religion to our own reigns, where a language is spoken whose roots are unknown to us, where everything is alien to our customs, laws, morals, and modes of dress, gathering together and forming a little homeland around the ambassador, by whom France is personified, had a poetic feel about it, even to those least susceptible to that sort of impression. There were individuals there, walking bareheaded beneath a burning sun, who, certainly, professed opinions opposed to those of the government represented by the Marquis; Republicans, exiles even; but at that distance from France all political hostility disappeared; one no longer remembered anything but the alma mater, the sacred motherland all shared. The arrival of the Charlemagne had caused some agitation among the Turkish population and, in the event of an affront or insult, everyone around the ambassador would have certainly been slaughtered; but the French caravan, fortunately, attained the palace, in spite of sidelong glances from those aged fanatics who still regret the days of the Janissaries, and cannot see a Frank pass without grumbling at him, from beneath their white moustaches, that sacramental insult: ‘Dog of a Christian!’

The presence of the Charlemagne in Constantinople coincided with numerous fires; there were no less than fourteen in one week, and the majority quite considerable in nature. To what were they to be attributed? To the extreme drought which made these houses, fashioned of beams and boards now half rotten with dilapidation, so many pieces of tinder ready to burst into flame at the slightest spark; to the spell cast by that mysterious steamboat without paddle-wheels or funnel, as the populace firmly believed; to the guilds of carpenters eager to create work for themselves; or, as people well acquainted with oriental customs were convinced, to a political cause?

Following Ramadan, which, with its fasts and exercises of piety, exalts the imagination, there is usually a recrudescence of fanaticism, and this change of mood was not favourable to Mustafa Reshid Pasha, then in office (as Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire), who was accused of leaning toward European ideas, and regarded almost as a giaour by the old Turks in green kaftans and large turbans, like those dressed mannequins that are kept behind the windows of the Elbicei Atika (Museum of Costume), that Lacus Curtius (see the Roman legend) of the past Ottoman nation. Though there is in Constantinople a French newspaper (the Journal de Constantinople) ably run by Francois Noguès, since it is subsidised by the State, the opposition, instead of writing articles, sets fire to a neighborhood, a significant way of displaying its ill humour, or so it is said, at least. I have difficulty believing it to be so, though this very means was formerly employed by the discontented Janissaries. Others saw in these fires which when barely extinguished were rekindled at another point in the city, the brand or at least the chemical mark of Russia, attempting to rouse the population against France; but the courage with which the crew of the Charlemagne tackled the flames, her captain, Charles Rigaut de Genouilly, at the head, climbing, axe in hand, onto the roofs of burning houses, and disputing their possession with the flames, engendered general goodwill. Reshid Pasha was replaced by Fuad Pasha (Keçecizade Mehmed Fuad Pasha), the continuator of his ideas. This slight concession restored calm, and the fires ceased, perhaps naturally, perhaps for that reason.

Given a city almost entirely built of wood, and the neglect which is a consequence of Turkish fatalism, fire is considered a normal thing in Constantinople. A sixty years old house is a rarity. Except for the mosques, aqueducts, walls and fountains, a few Greek houses in the Phanar, and a few Genoese buildings in Galata, everything is made of planks; the past ages have left no testimony on this soil perpetually swept by flames; the face of the city is wholly renewed each half-century, without however varying greatly. I am not speaking of Pera, the Marseilles of the Orient, in which, on the site of each burnt wooden hut, a solid stone house is immediately raised, and which will soon be an entirely European city.

At the top of the Seraskier Tower, a white lighthouse of prodigious height, rising into the azure, not far from the domes and minarets of the Beyazit Mosque, a lookout constantly prowls, waiting to detect, in the immense view unfolded in a panorama at his feet, black smoke, or a crimson tongue gushing from the gap in some roof. When the lookout sees that a fire has started, he hangs a basket from the top of the lighthouse if in daylight, or a lantern at night, attended by a certain combination of signals indicating the city district affected; the cannon thunders, and the lugubrious cry: ‘Stamboul, yangin var!’ (Stamboul’s on fire!) resounds sinisterly through the streets, all are roused, and the water-bearers (saccas), who are also the city’s firemen, hurtle off at a run in the direction indicated by the lookout.

A similar watch is kept from the Galata Tower, which is on the other side of the Golden Horn and almost facing the Seraskier Tower.

The Sultan, the Viziers, and the Pashas are required to attend fires in person. If the Sultan has withdrawn to the depths of the harem with a woman, an odalisque dressed in red, her head covered with a scarlet turban, lifts the door-curtain, enters the room, and stands there, silent and sinister. The appearance of this fierily-clad phantom announces to him that there is a fire ablaze in Constantinople, and that he must perform his duties as sovereign.

Circassian Slaves in the Interior of a Harem

I was seated on a tomb, one day, in the Little Field of the Dead, of Pera, and busy scribbling some verses, when I saw a cloud of bluish smoke rising through the cypresses, a cloud which turned yellow, then black, and emitted sundry jets of flame, which were lessened in their effect on the eye by the bright sunlight; I rose, looked for a gap from which to gain a view, and saw, that Kassim-Pasha (Kasimpasa) at the foot of the funereal hill, was ablaze. Kassim-Pasha is a rather miserable district, populated by the poor, by Jews and Armenians, squeezed between the cemetery and the arsenal. I descended its main street, lined with shops and huts, the middle of which consists of a muddy stream, a sort of open sewer, crossed by culverts; the fire was, as yet, concentrated in the vicinity of a mosque whose minaret I could best compare to a candle topped with a metal snuffer. I was fearful of seeing this minaret melt in the flames, which a change in the wind was driving in another direction, such that those who had thought they had nothing to fear suddenly found themselves threatened.

The street was crowded with black African women carrying rolled-up mattresses, hammals bearing chests, men saving their precious pipe-bowls and stems, frightened women dragging a child in one hand and a bundle of clothes in the other, kavasses and soldiers armed with long hooks, saccas running through the crowd their hoses on their shoulders, and men on horseback galloping off to seek reinforcements, without the slightest concern for the pedestrians; all were bumping into one another, jostling, knocking one another over, and shouting insults at one another in all sorts of languages. The tumult was at its height. Meanwhile the flames marched on, widening the circle of their ravages. Fearing to be thrown to the ground and trampled underfoot, I returned to the heights of Pera, and, hoisting myself onto a cippus of Marmara marble, I watched, in the company of some Turks, Greeks and Franks, the sad spectacle taking place at the foot of the hill.

The burning rays of the southern sun fell vertically onto the brown tiled or tarred plank roofs of Kassim Pasha, whose houses flared up one after the other like the items in a fireworks display. First a little jet of white smoke was seen to emerge from some gap, then a thin scarlet tongue of flame followed the white smoke, the house blackened, the windows glowed red and, in a little while, everything collapsed in a cloud of ash.

Against this background of fiery steam, the black silhouettes of men were outlined at the edge of various roofs, pouring water on the boards to prevent them from catching fire; others, with axes and hooks, were demolishing sections of walls to contain the blaze. The saccas, standing on those crossbeams that had remained intact, aimed the nozzles of their hoses at the flames; from a distance, their flexible leather hoses with shiny copper fittings looked like angry serpents fighting fire-eating dragons, and darting a silvery lightning at them. Sometimes the dragon spat a whirlwind of sparks from its dark flanks forcing a serpent to retreat; but the latter returned to the attack, hissing and furious, a quivering lance of water sparkling like a diamond. After dying down and then rekindling, the fire extinguished itself for lack of fuel; there remained only a few clouds of smoke rising slowly from the rubble and embers.

The following day, I visited the scene of the disaster. Two or three hundred houses had burned down. This was understandable if one considers the extreme combustibility of the materials; the mosque, protected by its walls and stone cloisters, alone had remained intact. On the sites of shacks reduced to ashes, only the brick chimneys remained standing, whose construction had resisted the action of the flames. Nothing was odder than these reddish obelisks isolated from all that had surrounded them the day before. One would have said a set of enormous skittles had been planted there for the amusement of giants, say Typhon or Briareus.

In the hot and, as yet, still smoking ruins of their houses, the former owners had already built temporary shelters for themselves using rush-mats, old carpet, and pieces of sailcloth supported on stakes, and were smoking their pipes with the resignation Oriental fatalism ever displays; horses were tied to stakes where their stables had been; sections of partitions, and stretches of nailed planks, had reconstituted the harems; a kahwedj was boiling his mocha on a stove, the only remains of his shop, around which, in the ashes, crouched his loyal customers; further on, bakers were skimming ash from piles of wheat in wooden bowls, of which the flames had only scorched the top layer; various poor wretches were searching the half-extinguished embers for nails and pieces of iron, the sole remains of their wealth, but without otherwise appearing desolate. I failed to see in Kassim-Pacha the distraught, desperate howling groups, that a similar event would see writhing, in France, over the ruins of a village or a burnt-out district; to be burned out, in Constantinople, is a quite commonplace matter.

I followed the path traced by the fire, as far as the Golden Horn, very close to the Arsenal. The heat was dreadful, made even worse by the fumes from the charred ground, which was still warm from the barely extinguished flames; I walked over embers covered with treacherous ash, amidst half-burnt debris: planks, beams, joists, fragments of sofas and sideboards; sometimes on grey earth, sometimes on blackened ground, amidst reddish smoke and throbbing sunlit air, hot enough to cook an egg; then I returned via a rather picturesque alley, beside a stream full of cast-off slippers, and fragments of pottery, which might have provided, with its two rickety bridges, a pretty motif for Williams Wyld’s or Louis Tesson’s watercolours.

I had seen the smoke by day; all I needed was the fire by night. That spectacle was not long in appearing; one evening, a purple glow, which I might best compare to the redness of the aurora borealis, tinged the sky, on the far side of the Golden Horn; I was eating an ice-cream, on the promenade of the Petit-Champ, and immediately left to charter a caique and be transported to the scene of the disaster, when, on passing close to the Galata Tower, one of my friends from Constantinople, who was accompanying me, had the idea of ascending the tower from which one can indeed view the opposite side of the port; a little baksheesh soon lessened any scruples the guard harboured, and we began to climb in the darkness, feeling the walls with our hands, trying each step with our feet, by a rather awkward staircase, whose spirals were interrupted by landings and doorways. We arrived, thus, at the lantern, and, walking on the copper sheets which covered the floor, went to lean on the edge of masonry with which the tower is crowned.

The oil and tallow stores were alight. These buildings are situated at the water’s edge, which, by reflecting the flames, produced a mirror-image of the dual blaze, amidst which the houses were silhouetted in black, and pierced with luminous holes as if by a drill. Trails of fire, scattered by the oscillation of the waves, stretched over the surface of the Golden Horn, similar at that moment to a vast bowl of fiery punch; the flames rose to a prodigious height, red, blue, yellow, or green, according to the material they devoured; sometimes a more vivid phosphorescence, a more incandescent glow, burst forth from the general blaze; thousands of sparks flew in the air like showers of gold and silver from a firework, and, despite the distance, one could hear the crackling of the fire. Above the flames, enormous masses of smoke swirled, bluish on one side, pink on the other, like sunset clouds. The Seraskier Tower (the Beyazit Tower), Yeni-Cami (the New Mosque), the Suleymaniye Mosque, the Mosque of Ahmed (the Blue Mosque), that of Selim (Yavuz Selim), and higher up, on the crest of the hill, the arches of the Aqueduct of Valens shone, illuminated by reddish reflections; the boats and vessels of the port were highlighted like Chinese shadows on a crimson background; two or three barges, too violently heated, caught fire, and for a moment a general conflagration was feared given the congested anchorage, but the flames were soon extinguished.

Despite the cold wind that chilled us at this height, for we were rather lightly dressed, my companion and I could not tear ourselves away from the magnificence of this disastrous spectacle, which enabled me to comprehend, and almost excuse through the beauty of it, Nero, watching on, as Rome burned, from his palace on the Palatine. It was a splendid blaze, a firework display raised to the hundredth power, with effects that pyrotechnics will never be able to achieve; and, as we had taken no part in the lighting of it, we could enjoy it from an artistic viewpoint, while deploring the misfortune.

Two or three days later, Pera caught fire in turn. The tekke of the Whirling Dervishes was swiftly invaded by flames, and I beheld a fine example there of Oriental phlegmatism. The leader of the Dervishes was smoking his pipe on a carpet, that was moved further back from time to time as the fire gained ground. The small portion of cemetery that stretched before the tekke soon became cluttered with all the objects, utensils, furniture and goods from threatened houses, that were often dropped from the windows for speed: the most grotesque earthenware was spread out over the tombs in a dreadful and comical jumble. The population, almost all Christian, of the district failed to show a like resignation to that of the Turks in similar circumstances; the women screamed or wept, while seated on their piled-up furniture.

Cries rose on all sides; the disorder and tumult were at their height. Finally, the fire was extinguished, and, from the tekke to the foot of the hill, only the chimneys remained standing. In the most serious disasters, there are always a few bizarre details: I saw a man who nearly perished trying to save some stove-pipes; further on, a poor old man and woman, who were watching over their dead son in a burning house, refused to abandon the corpse of their loved one, and had to be carried off by force. This was a most touching aspect of the event. As regards the picturesque, I noticed the cypresses of the Dervish’s Garden, dehydrated and yellowed, light up like seven-branched candlesticks.

Three or four nights later, Pera kindled once more at the other end, towards the Grand Champ-des-Morts; about twenty wooden houses burned like matchsticks, hurling sheaves of sparks, and tongues of flame, into the blue night sky, in spite of the water with which they were doused. The main street of Pera presented a most sinister aspect; the companies of saccas, hoses over their shoulders, traversed it at a full trot, overturning everything in their path, as is their privilege, since they are ordered to turn aside for no one; mouchirs (officers) on horseback, followed by a fierce squad of men, running on foot behind them, as in Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps’ painting The Turkish Patrol (1831, Wallace Collection, London) cast, in the light of the torches, strange silhouettes on the walls; dogs, trampled underfoot, fled in packs, uttering plaintive howls; Men and women passed by, bent beneath bundles; sais dragged frightened horses by their halters: it was both terrible and beautiful. Fortunately, a few stone houses obstructed the fire’s progress.

In the same week, Psammathia (Samatya), a Greek quarter of Constantinople, fell prey to the flames; two thousand five hundred houses burned. Then Scutari was ablaze, in turn. Every hour some corner of the sky reddened, and the Seraskier Tower was forever hoisting its basket or its lantern; one might have said the fire-demon was shaking his torch over the city. Finally, all the flames were extinguished, and these disasters were forgotten with that happy indifference without which the human species would not survive.

Chapter 22: Santa Sophia – The Mosques

It is dangerous for a giaour to enter a mosque during Ramadan, even with a firman (permit) and under the protection of the kavas (guard); the preaching of the imams excites a redoubling of fervour and fanaticism amongst the faithful; the exaltation of fasting heats idle minds, and the usual tolerance, brought about by the progress of civilisation, might easily be forgotten at such times. I therefore waited until after the Bayram to make this obligatory visit.

The tour usually begins with Hagia Sophia, the oldest and most important monument in Constantinople, which, before being a mosque, was a Christian church dedicated, not to a saint as its name might lead one to believe, but to the divine wisdom ‘Agia Sophia’, personified by the Greeks as the mother of the three theological virtues (faith, hope, and charity).

When viewed from the square in front of Bab-I Humayun (the Imperial Gate), with one’s back to the delicate carvings and sculpted inscriptions of the Fountain of Sultan Ahmed III, Hagia Sophia presents an incoherent mass, of misshapen construction. The original plan has vanished beneath a later aggregation of buildings, which obliterate the general lines and prevent them being easily discerned. Between the buttresses raised by Murad III to support the walls shaken by earthquakes, hang, like fungi on the veined bark of an oak-tree, tombs, schools, baths, shops, and stalls.

Above this tumult, between four rather heavy minarets, rises the great dome, supported on walls whose foundations are alternately pink and white, and surrounded like a tiara by a circle of openwork lattice windows; the minarets lack the elegant slenderness of Arab minarets; the dome sits heavily above the pile of disordered hovels, and the traveller, whose imagination has involuntarily conjured with the magic name of Santa Sophia, which makes one think of the Temple of Ephesus, and that of Solomon, experiences a sense of disappointment which fortunately fades when one has penetrated within. It must be said, by way of excusing the Turks, that most Christian monuments are also miserably obstructed, and that the sides of many a famed and marvellous cathedral are roughened by excrescences of plaster and pieces of planking, while its lacework spires most often soar from a chaos of vile huts.

To reach the door of the mosque, one follows a sort of alley, lined with sycamores, and with tombs whose painted and gilded stonework shines vaguely through the grilles, and soon finds oneself, after a few detours, in front of a bronze door, one of the leaves of which still bears the imprint of a Greek cross. This side-door gives access to a vestibule pierced by a further nine doors. One exchanges one’s shoes for slippers, which one must take care to have one’s dragoman bring with him, since entering a mosque in one’s boots would be as serious an impropriety as keeping one’s hat on in a Catholic church, and one which might produce far more unfortunate consequences.

As I entered, a singular mirage filled my sight; it was as if I was in Venice, emerging from the piazza into the nave of St. Mark’s, only the dimensions were disproportionately large; everything seemed colossal in size; pillars of immense height rose from the mat-covered paving; the curve of the dome flared like the sphere of the heavens: the pendentives, whereon the four sacred rivers (the Pishon, Gihon, Tigris and Euphrates, see Genesis 2:10-14) were depicted, pouring out their mosaic floods, described giant arcs, the galleries were wider so as to contain the crowd: St. Mark’s is Hagia Sophia in miniature, a scaling down, at the rate of an inch per foot, of Justinian’s basilica. That is scarcely surprising, however: Venice, separated from Greece by only a narrow sea, has always lived in close familiarity with the Orient, and its architects clearly sought to reproduce the structure of this church which was considered the richest and most beautiful in Christendom. The existing St. Mark’s was built in the eleventh century, and its builders had been able to see Santa Sophia in all its integrity and splendour, long before it was profaned by Mehmed II, in 1453.

The first church on the site was built on the ashes of a temple consecrated to divine wisdom, and on the orders of Constantine the Great, according to tradition (though it was consecrated in 360AD, under Constantius II), and was consumed in a fire (c404) following the troubles between the factions of the Greens and the Blues; its foundations were therefore rooted in an even deeper antiquity. A second basilica was inaugurated by Theodosius II in 415, and destroyed, again by fire, in 532. Justinian immediately commissioned Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus to draw up the plans for the third edifice, and direct its construction. To enrich the new church, numerous ancient pagan temples were despoiled, and the columns from the Temple of Diana, at Ephesus, still black from the torch of Herostratus, and the pillars from the temple of the Sun, at Palmyra, all gilded with the rays of that star, were used to support Christ’s dome; two enormous urns of porphyry were brought from the ruins of Pergamum, the lustral waters of which became the waters of baptism, and later those of ablution; The walls were covered with mosaics of gold and precious stones and, when all was complete, Justinian was able to cry in delight: ‘Glory be to God, who has judged me worthy of completing so great a work; I have surpassed even you, O Solomon!’

Although Islam, inimical to the plastic arts, stripped it of a large part of its ornamentation, Hagia Sophia is still a magnificent temple. The mosaics with a gold background, representing biblical subjects, like those in Saint Mark’s, have disappeared beneath a layer of whitewash. Only the four gigantic six-winged seraphs on the pendentives have been preserved, whose six multicoloured wings palpitate with scintillating golden crystal mosaic cubes; even then the heads which form the centre of these whirlwinds of feathers have each been hidden under a large gold star, the reproduction of the human face being abhorrent to Muslims. At the rear of the sanctuary, beneath the quarter-sphere vault which terminates it, one can vaguely see the outlines of a colossal figure which the layer of lime could not completely hide: it is that of the patron saint of the church, the image of divine Wisdom, or more exactly of holy Wisdom, Agia Sophia, and who, beneath this half-transparent veil, impassively attends on the ceremonies of an alien creed.

The statues have been removed. The altar, made of an unknown metal, produced like Corinthian brass from gold, silver, bronze, iron and precious stones in fusion, has been replaced by a slab of red marble, indicating the direction of Mecca. Above it hangs an old, worn carpet, a dusty rag which has for the Turks the merit of being one of the four carpets on which Muhammad knelt to pray.

Huge green disks, gifted by different Sultans, hang on the walls, and thereon gleam suras of the Koran or pious maxims written in enormous gold letters. A porphyry cartouche contains the names of Allah, Muhammad, and the first four Rashidun Caliphs, Abu-Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali. The pulpit (minbar) where the khatib (the person who delivers the sermon) places himself to recite from the Koran, is backed by one of the pillars which support the apse. It is reached by a rather steep staircase flanked by two openwork balustrades of a workmanship as rich and delicate as that of the finest guipure lace. The khatib ascends it, with the book of the law in one hand, and a sabre in the other, as if in a mosque taken by conquest.

Cords, from which hang silk tassels, and ostrich-egg shapes, descend from the vaults to within ten or twelve feet of the ground, supporting rings of iron wire, decorated with night-lights, so as to form chandeliers. Desks in the form of an X, similar to those at which one leafs through collections of engravings, are scattered here and there, supporting manuscripts of the Koran; several are decorated with elegant niello-work and delicate inlays of mother-of-pearl, shell, and copper. Rush mats in summer, carpets in winter, cover the pavement formed of marble slabs, the artfully-arranged veins of which seem to flow, like three rivers with frozen waves, across the nave. The mats have a singular peculiarity: they are laid obliquely, against the architectural line, so that the floor itself seems askew and not in accord with the bordering walls. This oddity is explained by the fact that Hagia Sophia was not intended as a mosque, and in consequence is not oriented, as is normal, towards Mecca.

Mosques are, visibly, quite similar within to Protestant churches. Art cannot display itself in pomp and magnificence there. Pious inscriptions, a pulpit, desks, mats for kneeling - this is all the ornamentation permitted. The idea of Allah must alone fill his temple, and it seems large enough indeed for that role. However, I confess, that to me the artistic luxury accompanying Catholicism seems preferable, and the alleged risk of idolatry is only to be feared among barbarous people incapable of separating form from content, and imagery from thought.

The principal dome, somewhat elliptical in its curvature, is surrounded by several half-domes as in St Mark’s in Venice; it is of immense height and must have gleamed like a gold and mosaic heaven before the Muslim limewash extinguished its splendours. As it is, it produced a more vivid impression on me than that of the dome of St. Peter’s in Rome; Byzantine architecture is certainly the essential form required by Catholicism. Even Gothic architecture, however great its religious value, does not suit it so exactly. In spite of every kind of despoliation, Santa Sophia still surpasses all the Christian churches I have seen, and I have visited many. Nothing equals the majesty of its domes, its tribunes supported by columns of jasper, porphyry, and verde antico, with capitals of a strange Corinthian order, on which animals, chimeras, and crosses intertwine with the carved foliage. The transcendent art of Greece, though in a somewhat degenerate form it is true, can still be felt here; it seems that when Christ entered this temple, Jupiter had only just departed.

A few years ago, Santa Sophia was in danger of collapse; the walls were bowed, the domes were cracked and splitting, the pavement undulated, the columns, weary of standing for so long, were tottering like drunken men; nothing was vertical, the whole building was visibly leaning to the right; in spite of the buttresses added during the sultanship of Amurath (Murad III), this church-mosque, compressed by the centuries, shaken by earthquakes, seemed ready to collapse upon itself. A highly-skilled architect from Ticino, Gaspare Fossati, accepted the difficult task of straightening and strengthening the ancient monument, underpinning the edifice, section by section, with untiring energy and prudence. Brass rings encircled the split columns, iron frames supported the collapsing arches, substructures solidified crumbling lengths of wall; the cracks through which rainwater infiltrated were blocked, all the worn stones were replaced; masses of masonry, cleverly concealed, relieved the pressure of the dome on pillars incapable of supporting it, and, thanks to this happy and complete restoration, Hagia Sophia has been granted a few more centuries of life.

During the work (begun in 1847), Gaspare Fossati (with his brother Giuseppe) was permitted to clean the layers of limewash, which had impregnated them, from the primitive mosaics, and before covering them again he copied them with pious care. That unique opportunity having been granted him, whereby he could contemplate the mosaics, he ought to have his drawings, which are of great artistic interest, engraved and published.

The mosaics I refer to are those of the dome and the half-domes. The others, which adorned the lower walls, are dilapidated and can be considered lost. Day after day, the mullahs, using their knives, extract the small cubes of crystal covered with gold leaf, and sell them to foreigners. I myself possess half a dozen pieces which were detached in my presence; though I am not one of those tourists who break the noses of statues so as to carry off a souvenir of the monuments they visit, I thought it wrong to disappoint the hopes of a little baksheesh, cherished by the honest osmanli.

From the summits of the tribunes, which are reached by gently sloping ramps like those which wind about the interior of the Giralda (the bell-tower of Seville Cathedral) and the Campanile (the bell-tower of St. Mark’s in Venice), one has an admirable view of the whole mosque. So placed, I saw that a number of the faithful, squatting on the mats, were performing their prostrations, most devoutly. Two or three women wrapped in their feredjes were standing near a door, and, with his head resting on the base of a column, a hammal was slumbering profoundly; a soft and gentle light fell from the high windows, and I saw in the hemicycle, opposite the minbar, the gleaming golden grille of the tribune reserved for the Sultan.

Platforms, of a kind, supported by columns of rare marble, and furnished with openwork railings projecting outwards from the general architectural line, advance, at each point of intersection of the naves. In the chapels of the side aisles, which are superfluous to the requirements of Muslim worship, trunks, chests and packages of all shapes are heaped; for mosques, in the Orient, serve as depositories; those who travel extensively, or who fear being robbed at home, place their riches there, under the guardianship of Allah, and there is not one example of a single asper (akçe, a silver coin) or para having gone astray; the theft would be deemed sacrilege; and the dust sifts across masses of gold, and precious effects, scantily wrapped in coarse cloth or scraps of old leather. The spider, so dear to Muslims through having woven its web at the entrance to the cave where Muhammad took refuge during the Hijrah, peacefully weaves its web over locked chests that no one touches.

Around the mosque are grouped imarets (hospices), medresses (‘madrasas’, schools), baths, and kitchens for the poor, because all Muslim life gravitates around the house of Allah; the homeless sleep there under the arches, where the police never disturb them, since they are Allah’s guests; the faithful pray there, the women dream there, the sick are carried there, to be healed or to die. In the Orient, daily life is not separate from the religious life.

I have searched in vain in Hagia Sophia for a trace of the blood-stained handprint that Mahomet II, on entering the sanctuary on horseback, left on the wall as a sign of his taking possession, when the distraught women and virgins took refuge near the altar, counting on a miracle that failed to occur to save them. Is that crimson imprint a historical fact or simply part of a legend?

Since I have just employed the word ‘legend’, I will relate one, current in Constantinople, to which the events of the day will grant the merit of relevance. When the gates of Santa Sophia opened beneath the pressure of the barbarian hordes besieging Constantine’s city, a priest was saying mass at the altar. Hearing the noise the hooves of the Tartar horses made on Justinian’s flagstones, the howls of the soldiery, and the cries of terror emitted by the faithful, the priest interrupted the holy sacrifice, took the sacred vessels with him, and headed towards one of the side aisles at a calm and solemn pace. The soldiers brandishing their scimitars were about to reach him, when he vanished into the wall which opened then closed behind him; at first there was thought to be some secret exit, a hidden doorway; but no: the wall was probed and found to be solid, compact, impenetrable. The priest had somehow passed through a mass of masonry.

Sometimes, it is said, one hears vague psalmody emerging from the thickness of the wall. It is the priest, still living, like the emperor Barbarossa who murmurs, in his sleep, the interrupted liturgy, from the depths of his cavern in the Kyffhäuser hills. It is said that when Santa Sophia is restored to Christian worship, the wall will open of its own accord, and the priest, emerging from his retreat, will complete, at the altar, the mass begun four centuries ago.

Given the current state of the Eastern Question (as to the fate of the countries of the Ottoman Empire), the legend, however improbable it may be, may very well come true. Might 1853 see the priest of 1453 cross the nave of Hagia Sophia, and climb the stair to Justinian’s altar with ghostly step?

On leaving Hagia Sophia, I visited a number of mosques. That of Sultan Ahmed I (the Blue Mosque), situated near the Atmeidan (At-Meydani Square, Sultanahmet Square), is one of the most remarkable, in possessing six minarets, hence its Turkish name of Alti-Minareli-Cami (the Six-Minarets-Mosque). I mention this circumstance, because it gave rise, during the construction of the building, to a debate between the Sultan and the Imam of Mecca.

The Imam, crying out against impiety, and sacrilegious pride, protested that no other Islamic shrine should equal in splendour the holy Kaaba (‘cube’ in Arabic) at Mecca, which was then flanked by the same number of minarets. The work was interrupted, and the mosque was in danger of remaining unfinished, when Sultan Ahmed, an intelligent individual, found an ingenious subterfuge to satisfy the fanatical imam: he had a seventh minaret erected at the Kaaba.

The construction of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque involved insane sums, and it was calculated that, if apportioned out, each sixteenth of an ounce of stone cost three aspers. Whatever the total, it was worth that amount. Its high dome, surrounded by four semi-domes, rises majestically amidst six glorious minarets, each encircled by tiered balconies like bracelets. Before it, is a courtyard surrounded by columns with bronze bases and black and white capitals, supporting arches forming a quadruple portico or cloister, if the latter word does not sound too odd in describing a mosque. In the centre of the courtyard stands a highly-ornate fountain, flowery, and adorned with arabesques, foliage, interlaced carvings, and covered with a cage of gilded latticework, doubtless to protect the purity of its water, intended for ablutions.

The architectural style is, throughout, noble and pure, and recalls the finest periods of Arab art, though the construction dates to no earlier than the beginning of the seventeenth century. A bronze door, which one reaches by a flight of a few steps, gives access to the interior of the mosque.

What strikes one at first are the four enormous pillars, or rather the four fluted towers which bear the weight of the main dome. These pillars, their capitals carved in a frieze resembling a row of stalactites, are circled halfway up by a flat band covered with inscriptions in Turkish lettering; their character of robust majesty and indestructible power produces a striking effect.

Verses from the Koran also encircle the cupolas and domes, the whole length of their cornices; an ornamental motif imitated from the interior of the Alhambra, and one to which Arabic writing lends itself admirably with its characters resembling the designs on Kashmir shawls. Alternate black and white keystones border the arches; the mihrab, the niche which designates the direction of Mecca, and in which the holy book is placed, is encrusted with lapis-lazuli, agate, and jasper: it is even said that there is embedded therein a fragment of the black stone of the Kaaba, a relic as precious to Muslims as a piece of the True Cross to Christians; it is in this mosque that the standard of the Prophet is preserved, which is only unfurled, as the oriflamme (royal banner) was under the old French monarchy, on solemn and supreme occasions. Mahmud II had it deployed when, surrounded by imams, he announced to the prostrate people the forced disbandment of the Janissaries (in 1826).

The minbar (pulpit) topped by its tall conical soundboard; the muezzin mahfili or platform supported by small columns from which the muezzins call the believers to prayer; and the chandeliers decorated with crystal orbs and ostrich egg shapes, complete the decoration, which is the same in all the mosques; as in Hagia Sophia, chests, trunks, packages, and other deposits, placed there under divine protection in a show of Muslim piety, are piled beneath the vaulting of the side aisles.

Near the mosque is the turbe or tomb of Sultan Ahmed I, the glorious Padisha who sleeps in his funeral chapel, in a coffin with a sloping roof, covered with precious fabrics from Persia and India, at his head his turban with a crest of jewels, at his feet two enormous candlesticks as broad as ship’s masts. Some thirty coffins or so, of smaller dimensions, surround him, including those of his wife and four of his sons, who accompany him in death as in life. At the bottom of a chest sparkle his sabres, kandjars (knives), and other weapons studded with diamonds, sapphires and rubies.

The description I have given, absolves me from having to provide details of the mosque of Sultan Bayezid II, which differs only in a few slight architectural peculiarities easier to convey with a brush than a pen. Inside, one notices beautiful columns of jasper and Egyptian porphyry; above the cloister which accompanies it, swarms of pigeons as familiar as those of St. Mark’s Square fly endlessly. A fine old Turk stands beneath the arcade with sacks of vetch or millet. One buys a measure from him, which one scatters by the handful; then, from the minarets, domes, cornices, and capitals, fall thousands of doves, forming variegated whirlwinds, which rush around your feet, descend on your shoulders, your face whipped by the breeze they raise with their wings; one suddenly finds oneself the centre of a feathered tornado. After a few minutes, not a single grain of millet remains on the flagstones, and the sated swarm return to their aerial roosts, to await another beneficial windfall. These pigeons are descended from two wood-pigeons that Sultan Bayezid once bought from a poor woman who implored his charity, and which he donated to the mosque. They have bred prodigiously.

According to the custom of the founders of mosques, Bayezid’s turbe is close to the mosque to which he gave his name. He lies there, covered with a carpet of gold and silver, with beneath his head, in an act worthy of Christian humility, a brick kneaded from the dust collected on his clothes and shoes, for there is a saying attributed to the Prophet, conceived thus: ‘It will not happen that feet soiled with dust, while on the path of Allah, will be touched by the fires of Hell.’ (See Book 11, Hadith 19, of the ‘Riyad as-Salihin’)

I shall not pursue this review of the Mosques any further, they being all alike, with only minor variations. I will mention only the Suleymaniye, one of the most perfect architectural examples, near which is a turbe where lie, next to those of Suleiman the Magnificent, the remains of the famous Roxelane, beneath a coffin covered with cashmere. Not far from the mosque is a porphyry sarcophagus, which is said to be that of the emperor Constantine.

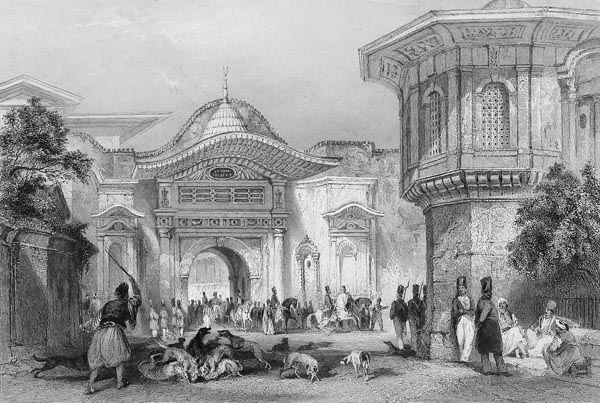

Chapter 23: The Seraglio (The Topkapi Palace)

When the Sultan is occupying one of his summer palaces, it is permissible, by means of a firman, to visit the interior of the Seraglio. As regards the word ‘seraglio’, banish your dreams of Muhammad’s paradise. Seraglio is the generic word for a palace (Italian ‘serraglio’ from the Latin serraculum, ‘enclosed’), as distinct from the harem, the women’s dwelling, a mysterious retreat which no profane person is permitted to enter, even when the houris are absent.

Usually, ten or so people gather to undertake the tour, which requires numerous donations of baksheesh whose total can scarcely be less than one hundred and fifty to two hundred francs; a dragoman precedes you, who settles all these annoying details with the guards at the doors; he certainly robs you; but, as one knows no Turkish, one must suffer it. One must take care to bring slippers for oneself; for if, in France, one takes off one’s hat when entering a formal building, in Turkey one takes off one’s shoes, which is perhaps more rational, since one leaves the dust of one’s feet at the threshold.

The irregular buildings of the Seraglio, or the Serai, as the Turks say, occupy a triangular area washed on one side by the waves of the Sea of Marmara, and on the other by those of the Golden Horn. A crenellated wall circumscribes the enclosure, which covers a vast area. A paved bank, a few feet wide, borders the two sides that face the sea. The flow beyond rushes by with extraordinary impetuosity; the blue waters boil like the surface of a cauldron, and cause millions of crazy spangles to dance in the sun; they are, moreover, of a singular transparency, and allow a glimpse of the sea-bed, composed of greenish rocks or white sand, amidst a tumult of fractured rays. Boats can only ascend these rapids when hauled by ropes.

Above the walls, generally in ruins and with blocks of stone from ancient now-demolished buildings mingled among them, one can see other buildings with small barred windows, kiosks in a Chinese or rococo style, the tips of cypresses, and clumps of plane trees. Over all there weighs an air of solitude and abandonment; one would scarcely believe that within this gloomy enclosure lives the glorious Caliph, the all-powerful sovereign of Islam.

We entered the Seraglio through a door of quite simple design, guarded by a few soldiers. Beneath this portal, rifles, arranged in perfect order, are deposited in magnificent mahogany cupboards furnished with racks. Once beyond the door, our little band, preceded by a palace official, a kawas and the dragoman, crossed a sort of vague hilly garden, planted with enormous cypress trees - a cemetery minus the tombs - and soon arrived at the entrance to the apartments.

At the invitation of the dragoman, we each donned our slippers, and began the ascent of a wooden staircase with nothing monumental about it. In northern countries, where one forms an exaggerated idea of Oriental magnificence derived from Arab tales, the calmest minds cannot help but imagine a fairy-tale architecture with columns of lapis lazuli, capitals of gold, foliage wrought of emeralds and rubies, and fountains of rock-crystal where jets of quicksilver tinkle. The Turkish style is thus confused with the Arab style, although the two of them have not the slightest connection, and one dreams of Alhambras where, in reality, there are only well-ventilated kiosks and rooms decorated in a quite simple manner.

The first room we entered is circular in shape; it is pierced with numerous latticed windows; all around it is a divan, the walls and ceiling are decorated with gilding and black snake-like arabesques; black curtains, and a lambrequin (decorative drape) cut to follow the line of the cornice, complete the decoration. A very fine esparto mat, which, no doubt, is replaced in winter by soft Smyrna carpeting, covers the floor. The second room is painted with grisailles in distemper, in the Italian manner. The third is decorated with landscapes, mirrors, blue draperies and a clock with a radial dial. On the walls of the fourth run sentences written by Mahmud’s own hand, he being a skilled calligrapher who, like all Orientals, took pride in his talent, an understandable vanity as this form of writing, complicated by curves, knots, and interlacing lines, is very close to drawing. After traversing these rooms, we arrived at a smaller room.

Two pastel works by Michel Bouquet were the only two art objects that attracted the eye in these rooms in which a severe Islamic bareness reigns: one represented the Port of Bucharest, the other, a View of Constantinople from the Tower of the Maiden, both free of human images, of course. A clock with a mechanical panel, representing the Seraglio Point, with caiques and ships, that roll and pitch moved by cogs beneath, excited the admiration of the good-natured Turks, and smiles from the giaours as such a clock would be more at home in the dining room of a wealthy grocer than in the mysterious rooms of the Padisha. The same room, as if in compensation, contained a cupboard whose curtains when drawn back allowed the true luxury of the Orient to gleam forth in a phosphorescence of gold and precious stones.

Here are treasures that the Tower of London might envy: it being customary for each Sultan to bequeath to the collection an object that has particularly pleased him. Most have given weapons: there are kandjars, their handles studded with diamonds and rubies; scabbards, adorned with damask and embossed with silver; bluish blades foliated with Arabic inscriptions in gold lettering; maces richly-nielloed; and pistols whose butts disappear beneath layers of pearls, coral, and precious stones; Sultan Mahmud, in his capacity as poet and calligrapher, donated his writing-desk, a heap of gold covered with diamonds. Through a sort of civilised coquetry, he wished to mix the products of thought with all those instruments of brute force, and show that the brain has its powers, like the arms. In this room, we noticed a curious Turkish fireplace decorated with features in the ‘honeycomb’ style, like to those ‘stalactites’ that hang from the ceilings of the Alhambra.

Beyond reigns a gallery where the odalisques amuse themselves, and exercise, under the eye of the eunuchs, who perform there almost the same function as the supervisors in school playgrounds. But such a sacred place is forbidden to the profane, even when the birds have flown the cage. A little further on are the rounded domes, studded with large crystalline warts, which cover the bathhouses decorated with alabaster columns and marble features, which we had to be content to admire from the outside.

The Favourite Odalisque

We recovered our shoes at the door by which we had first entered, and continued our visit. We first skirted a garden filled with flowers, the beds framed with wood, in the old French fashion; then we crossed courtyards surrounded by cloisters of a sort, with Moorish arcades, where the icoglans, or pages, of the Seraglio, have their lodgings and schoolrooms, and arrived at a kiosk or pavilion containing the library; we ascended to it by a flight of steps, and a marble ramp pierced with delicate windows.

The door of this library is a marvel. Never has Arab genius traced on bronze a more prodigious network of lines, angles, and stars, mingling, knotting, and intertwining in a mathematically-ordered maze. Only a daguerreotype could capture its magical ornamentation. Any designer who set out to copy, conscientiously, with his pencil, those inextricable meanders would go mad after an effort the completion of which would take a lifetime.

Inside the library, Arabic manuscripts are stored in cedar lockers, their fore-edges not their spines facing the viewer, a particular arrangement that I had already noticed in the library of the Escorial, and which the Spaniards undoubtedly borrowed from the Moors.

There we were shown a large roll of parchment depicting a kind of genealogical tree, with miniature portraits of all the sultans, in oval medallions, and executed in gouache. The portraits are, it is said, authentic, a thing hard to believe. All are of pale heads with black beards, and of a fairly uniform type, and the costume is that of the Turks in Molière’s and Racine’s plays, which are more exact in their details than one might think.

The library once visited, we entered a kiosk in the Arab style, preceded by a staircase with marble banisters in which the ancient Oriental magnificence shone in all its splendour, a splendour of which, as I have said, the apartments we had already visited offered not a trace.

The greater part of the room is occupied by a throne in the form of a divan or bed, with a canopy supported by hexagonal columns of gilded copper sown with garnets, turquoises, amethysts, topazes, emeralds and other stones in the state of cabochons, for formerly the Turks did not cut precious stones; horse-tails hang from the four corners of large gold balls surmounted by crescents. Nothing is richer, more elegant and more royal than this throne truly made to seat caliphs.

Barbarous peoples alone possess the secret of these marvellous pieces in gold; the feel for such ornamentation seems to be lost, one knows not why, as civilisation perfects itself. Without displaying an antiquarian’s mania regarding the past, it must be admitted that the older the date, the remoter the era, of an architectural style, a piece of jewellery, or a weapon, the more perfect the taste exhibited and more exquisite the work: preoccupied with ideas, the modern world lacks a true notion of form.

A few rays of light falling from a half-open window made the carvings glitter and cast fire on the gems. Arab earthenware tiles formed shimmering symmetrical patterns, on the lower parts of the walls, as in the rooms of the Alhambra in Granada; while, on the ceiling, curiously carved silver-gilt rods intersected, forming coffers and rosettes. In a corner, amidst the shadows, shone a strange Turkish fireplace in the form of a niche, and intended to receive a brazier; a sort of small conical dome with seven sides, in copper, pierced and fenestrated like a fish-slice, and nielloed with the most elegant designs of Arab art, served as its mantle. Certain Gothic reliquaries alone give an idea of this charming work.

Opposite the divan was a window, or rather a skylight, furnished with a thick grille with gilded bars. It was outside this kind of wicket-window that ambassadors formerly stood, their sentences being transmitted by intermediaries to the Padisha, crouching, with the immobility of an idol, beneath his canopy of silver-gilt and precious stones, and between two symbolic turbans. They could see, though barely, through the golden mesh, the fixed pupils of the magnificent Sultan shining like twin stars from the depth of darkness; but that was considered quite sufficient for giaours: the shadow of Allah might reveal no more of itself to ‘Christian dogs’.

The exterior is no less remarkable. A large roof with a strongly projecting overhang, crowns the building; marble columns support ribbed arcades and rosettes; a slab of verde antico, decorated with an Arabic inscription, forms the threshold of the door, the lintel of which is quite low: an architectural arrangement devised, it is said, to force recalcitrant vassals and tributaries, when admitted to the presence of the Grand Seigneur, to bow their heads, a rather Jesuitical piece of etiquette, which was evaded, in a comical manner, by a Persia envoy, who entered backwards, as one enters a gondola in Venice.

In describing the Bayram ceremony, I spoke at some length of the portico beneath which it takes place, so I will not repeat the description, but continue my somewhat random perambulation, mentioning things as they present themselves. It would be hard to give a more coherent account of these buildings of various periods and in various styles, erected to no preconceived plan, but rather according to the whims and necessities of the moment, separated moreover by ill-defined spaces, shaded here and there by cypresses, sycamores, and old plane trees of monstrous dimensions.

From the middle of a clump of trees rose a fluted column with a Corinthian capital, which produced a charming effect, and which is attributed to Theodosius, an attribution whose value I am not knowledgeable enough to dispute. I cite it because Byzantine ruins are scarce in Constantinople. The ancient city has disappeared almost without trace; the ornate palaces of the Greek dynasty, of the Palaiologi and the Comneni, have vanished; their marble and porphyry columns were re-used when constructing the mosques, and their foundations, covered by frail Muslim buildings, have been obliterated little by little beneath the ashes of fires; sometimes one finds, amalgamated with a wall, a capital, or a fragment of broken torso, but nothing that has retained its original form; one must excavate in order to bring to the surface what remains of ancient Byzantium.

A notable feature, which marks a degree of progress, is that in the courtyard, in front of the ancient church of Hagia Irene which has been transformed into an arsenal and is part of the dependent areas of the Seraglio, various antique objects have been gathered together: heads, torsos, bas-reliefs, inscriptions, and tombs, forming the rudiments of a Byzantine Museum, which could be rendered even more interesting by the addition of daily finds.

Near the church, two or three porphyry sarcophagi, strewn with Greek crosses, which must have contained the bodies of emperors and empresses, and which are now deprived of their broken lids, are filled with rainwater, and birds come to drink there, uttering little joyful cries.

The interior of Hagia Irene contains a display of rifles, sabres, and pistols of modern design, arranged with a military symmetry that our Artillery Museum would not disavow; but the glittering collection, which charms the Turks greatly, and of which they are very proud, holds nothing to astonish a European traveller. A display that offers a quite different level of interest is one of historical weapons, preserved in an arcaded platform transformed into a gallery, at the back of the apse.

There we were shown the sabre of Mehmed II, with an almost straight blade, along which runs, on a background of bluish damascene steel, an Arabic inscription in gold letters; also, an armband nielloed with gold, and studded with two circles of precious stones, which belonged to Tamerlane; and a chipped iron sword, with a cross-shaped hilt, a sword said to be that of Skanderbeg (Gjergj Kastrioti), the energetic Albanian hero. Glass cases contain the keys to conquered cities, symbolic keys worked like jewels and damascened with gold and silver.

In the vestibule are piled the kettledrums and cooking pots of the Janissaries, those cooking pots (kazans) which, when overturned, made the Sultan tremble and turn pale in the depths of his harem (being a sign of mutiny); also, bundles of old halberds, chests full of weapons, ancient cannons, and culverins of singular shape, recall the Turkish military prior to Mahmud II’s reforms (in 1826), which were necessary, no doubt, but regrettable from the point of view of the picturesque.

The stables, which I glanced at in passing, revealed nothing special, and contained, at the time, only ordinary breeds, the Sultan being followed by his favourite mounts. The Turks, moreover lack the Arab mania for horses, though they like them, and possess some which are remarkable.

This is about all a stranger can see of the Seraglio. No profane glance defiles its mysterious sanctuaries, secret kiosks, and intimate retreats. The Seraglio, like every Muslim house, has its selamlik, but it is for the harem that all the refinements of voluptuous luxury, the cashmere divans, Persian carpets, Chinese vases, gold cassolettes, lacquer cabinets, mother-of-pearl tables, cedar ceilings with painted and gilded coffers, fountains with marble basins and jasper columns, are reserved; the men’s residence is, in a way, only the vestibule of the women’s; a guardhouse interposed between the exterior life and the interior life.

I greatly regretted not being able to enter the marvellous bathhouse, a true Oriental dream come true, of which my friend Maxime Du Camp has given a splendid description (see his ‘Souvenirs et Paysages d’Orient’, Chapter IX, of 1848); but, this time, the guard was surlier, or perhaps fresh orders had been given. If the houris take steam baths in Paradise, it must be in a bath like that one, a jewel of Muslim architecture.

Quite weary from walking, having had to doff and replace my shoes six or eight times, I left the Seraglio by the Imperial gate (Bab-i Humayun) and leaving my companions behind, went and seated myself on the bench outside a little café, from where, while eating Scutari grapes, I could contemplate the monumental gate, in the centre of its main edifice, with a high Moorish arch, four columns, a marble cartouche bearing an inscription in gold letters, and twin niches where severed heads were displayed. Among others, that of Ali Tepelena, Pasha of Janina, appeared there on a silver plate (after his assassination in 1822).

I also examined, in detail, the delightful fountain of Sultan Ahmed III, which I had glanced at on my way to Hagia Sophia. It is, with the fountain of Tophane, the most remarkable in Constantinople, which contains so many and such pretty ones. Nothing can compare, for elegance, to its spreading roof turned up at an angle like the tip of a Turkish shoe, with openwork panels beneath decorated with filigree work, and topped with capricious pinnacles; or to those four niches; to the stalactite-like surround above; to the framed arabesques of pieces of verse composed by the sultan-poet; to those small columns with fanciful capitals, the gracefully starred rosettes, the wilting flowery cornices, to that charming tangle of ornamentation, a happy mixture of Arab and Turkish art. There, I will stop, because, despite Boileau’s precept, I fear being carried away by the festons (flowery festoons) and astragales (ornamental mouldings: for festons and astragales, see Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux’s poem ‘Chant I’, which criticises exhaustively detailed description, specifically line 56).

Chapter 24: The Bosphorus Palace (Dolmabahçe Palace) – The Sultan Mahmud Mosque – The Dervish

When one is sailing, in a caique, on the Bosphorus, and has passed the Tower of Leander, one sees, opposite Scutari (Üsküdar), an immense palace, currently still under construction, its white feet bathed by the rapid blue waters. There is a superstition in the Orient, assiduously maintained by its architects, that one cannot die until the residence one is in the process of building is complete, so the Sultans are always careful to have the erection of some palace or other under way.

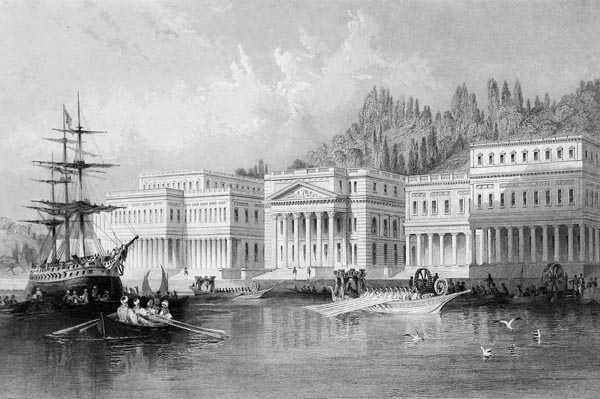

The Sultans' new palace on the Bosphorus

A rare thing among the Turks, who devote solid and precious materials to the house of Allah, and erect, for their temporary habitation, mere wooden kiosks as little durable as themselves, this palace is of marble throughout, and built to last for all eternity. It is composed of a large central section and two wings. To say to what order of architecture it belongs would be difficult; it is neither Greek, nor Roman, nor Gothic, nor Renaissance, nor Saracen, nor Arab, nor Turkish, but approaches that genre the Spaniards call Plateresco, whereby a building’s facade resembles a large piece of silverwork, in its complex richness of ornamentation, and obsessive refinement of detail.

The windows, with their open balconies, ribboned columns, ribbed trefoils, and festooned frames, the interspaces occupied by detailed sculptures and arabesques, recall the Lombard style and bring to mind the ancient palaces of Venice – except that between the Palazzo Dario, or the Ca’d’Oro, and the Sultan’s Palace there is the same difference in scale as between the Grand Canal and the Bosphorus.

This enormous construction in Marmara marble, of a bluish-white colour that the garish brilliance of its newness renders a little cold, produces a most majestic effect, rising between the azure of the sky and the azure of the sea; it will produce a finer one still, once the hot sun of Asia has gilded it with its rays, which it receives directly and from which it is unshaded. Vignola (Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola, the Mannerist architect) would doubtless not recognise this hybrid facade in which the styles of all times and all countries form a composite architectural order that he himself did not foresee. But one cannot deny that this multitude of flowers, foliage, rosettes, chiselled like jewels from precious material, has a dense, complicated, sumptuous and pleasing appearance to the eye. It is the palace an ornamentalist not an architect might build, sparing neither labour, time, nor expense. As it is, I prefer it to sullen classical reproductions, unintelligent, flat, cold, and tedious, such as mere scholars and pedants create, and I prefer lively ornamental foliage, intertwining in whimsical elegance, to a triangular pediment or a horizontal attic resting on six or eight slender columns. This display of naive unsophistication, on a gigantic scale, has its charm; probably the bold masons of our cathedrals knew no more, but their works are no less admirable for that.

A central reservation runs the length of the palace, bordered, on the Bosphorus side, by monumental pillars linked together by grilles of ornate and charming ironwork, in which the metal is curved in a thousand flowery arabesques, as delicate as the lines that a bold pen would trace freehand on vellum. These gilded grilles form a balustrade of extreme richness.

The two wings, built at another time, are far too low for the main building, with which they have no relation in style or form. Imagine a double row of miniature Odéons, and Chambers of Deputies, following one another in tedious alternation, and presenting to the eye a row of small, slender columns that seem made of wood though they are of marble.

On many occasions, as I passed, and repassed this palace, I felt the desire to pay it a visit. In Italy, nothing would have been simpler; but to have one’s caique land at an Imperial landing stage would be in Turkey an action of consequence, which might well have unfortunate repercussions. Fortunately, a friendly intermediary put me in touch with one of the architects, Nigoğayos Balyan (who worked with his father Galabert on the building), a young Armenian of great intellect, who spoke French.

Monsieur Balyan was kind enough to take me in his boat, equipped with three pairs of oars, and first made me enter an old kiosk, a remnant of the previous palace, to which were brought pipes, coffee and rose-sherbets; then he himself led me through the apartments, in a perfectly obliging and polite manner, for which I thank him here, hoping that perhaps one day these lines will pass before his eyes (sadly, he died of typhoid in 1858, aged 32).

The interior was not quite finished, but one could already judge the future splendour of the whole. The religious reservations held by the Turks robbed the ornamentation of a host of happy motifs, and considerably restricted the artist’s imagination, who had to carefully abstain from representing any animated being amidst his arabesques: thus there were no statues, bas-reliefs, grotesque heads, chimeras, griffins, dolphins, birds, sphinxes, wyverns, butterflies, figurines half-woman half-flower, no heraldic monsters, none of those bizarre creations which form the fabulous zoology of ornamentation, and of which Raphael made such marvellous use in the galleries of the Vatican.

The Arab style, with its broken lines and decompositions, its incised guipure-lace stucco, its stalactite-like ceilings, its honeycomb niches, its marble features pierced like the lid of a cassolette, its legends in flowery Kufic script, and its use of green, white, and red, discreetly enhanced with gold, would have offered its traditional resources in decorating this Oriental palace; but the Sultan, as a result of the sort of whim which might prompt us to build Alhambras in Paris, wished it to be designed to suit the modern taste. One may be astonished, at first, by this whim of his, but, on reflection, nothing is more natural. It would have required a rare fertility of imagination on Monsieur Balyan’s part to decorate each of more than three hundred rooms or halls in unique ways, with such a limited range of motifs at his disposal.

The general arrangement is very simple: the rooms follow one another in sequence, or open onto a wide corridor; the harem, among others, is thus arranged. Each female’s apartment opens through a single door onto a vast arcade, like the cells of nuns in a cloister. Each end of the arcade offers a post for the eunuchs or the bostanjis (guards). I glanced from the threshold at this sanctuary of secret pleasures, which is more like a convent or a girl’s boarding school than one might imagine. There, without having ever shone beyond its walls, unknown beauteous stars are doomed to be extinguished; yet the eye of the master will have been fixed on them, even if for only a minute or so, and that suffices.

The apartment of the Sultana Valide (the Sultan’s mother), composed of tall rooms overlooking the Bosphorus, is remarkable for its ceilings, painted in fresco with an incomparable elegance and freshness of execution. I know not who the workers were who created these marvels, but Narcisse Diaz would find, on his palette, no finer tones, none more vaporous, kinder, yet at the same time richer. Sometimes they represent turquoise skies with patches of light cloud that flee to incredible depths, sometimes immense veils of lace with marvellous designs, then the eye sees a large mother-of-pearl conch, iridescent, glittering with all the colours of the prism, or idealised flowers their corollas and foliage hanging from golden trellises; other rooms are decorated in similar fashion. Sometimes a casket whose jewels spread in shimmering disorder, or a necklace whose pearls unravel and scatter like raindrops, or a stream of diamonds, sapphires and rubies, forms the motif of the decoration; golden cassolettes painted on the cornices appear to release bluish perfumed vapours, to create a ceiling of transparent mist. Here, Phingari (the moon: see Byron’s ‘The Giaour’, line 468) shows, amidst the clouds, that silvery arc so dear to the Muslims, there, modest Aurora colours, with a pink hue like that of virgin cheeks, a whole morning sky; further on a piece of brocade grainy with light, shimmering with orphrey (dense embroidery), embedded with garnets, shows a corner of blue; an azure cave throws out sapphire reflections. The infinitely intertwined arabesques, the sculpted coffers, the gilded rosettes, the bouquets of imaginary or realistic flowers, blue lilies from Iran, or roses from Shiraz, vary the motifs, the main ones of which I have cited, without choosing to enter into an impossible level of detail which the reader’s imagination will surely supply.

The Sultan’s apartments are in an Orientalised Louis XIV style, the intention of which, one feels, is to imitate the splendour of Versailles: the doors, the windows, and their frames, are made of cedar, mahogany, or solid rosewood, delicately carved, and clad with rich ironwork gilded with fine gold. From the windows one has the most marvellous view in the world: an unrivalled panorama such as never fronted a royal palace. The Asian shore, where, Scutari rises, against an immense curtain of black cypresses, displaying its picturesque landing-stage cluttered with boats, its pink houses, and its white mosques, among which Buyuk-Cami (the Ortaköy Mosque) and Yavuz Sultan Selim stand forth; the Bosphorus with its swift, transparent waters is furrowed by the perpetual to-ing and fro-ing of sailing vessels, steamboats, feluccas, flat-bottomed craft, boats from Izmit and Trebizond of ancient shape and with strange sails, canoes, and caiques, above which flutter familiar swarms of herring gulls and others. If one leans forward a little, one discovers a series of summer dwellings, on both banks, with kiosks, painted in fresh colours, forming a double quay of palaces for this marvellous marine estuary. Add to these a thousand accidents of lighting, the effects of sun and moon, and you have a spectacle the imagination cannot surpass.

One of the singularities of the palace is a large room covered by a red glass dome. When the sun penetrates this ruby dome, all takes on a strange flamboyance: the air itself seems to ignite; one feels one is breathing fire; the columns are illuminated like those of street-lamps, the marble floor reddens like a pavement of lava; a fiery pink glow devours the walls; one would think one was in the reception room of a salamandrine palace formed of molten metal; your eyes shine like red sparks, your clothes become purple garments. An operatic version of Hell, lit by Bengal lights, could alone give an idea of this strange effect, of an equivocal tastefulness perhaps, but striking, indeed.

A small marvel that would not look out of place amidst the enchanted architecture of the Thousand and One Nights is the Sultan’s bathroom. It is in the Moorish style, in ribboned Egyptian alabaster, and seems to have been carved from a single precious stone, with its low columns, flared capitals, heart-shaped arcades, and vaulting studded with crystal portholes that gleam like diamonds. What a pleasure it must be to abandon one’s limbs, mollified by the skilful manipulations of a tellak, to these slabs, as translucent as agate, amidst a cloud of perfumed vapour, and beneath a rain of rose water and benzoin!

It is in one of the rooms of this palace that the Louis XIV style salon constructed and painted, in Paris, by Charles Séchan, that illustrious creator of Opéra sets, a salon of which I wrote when he displayed it in his workshop on Rue Turgot, should be placed.

Tired of wonders, weary of admiring them, I thanked Monsieur Balyan, who led me out of the palace through the courtyard of honour, whose door is a kind of triumphal arch in white marble with very rich and ornate ornamentation, and which forms on the landward side an entrance quite worthy of this sumptuous building. Then, as I was famished, I entered a fruiterer’s shop, and there I purchased two skewers of kebabs, the ends wrapped in greasy crepe paper, washing the meal down with a glass of sherbet; a sober meal, and entirely local in nature.

Leaving the shop, I began to wander, at random, through the city, counting on a short stroll to reveal to me those thousand familiar details which elude one if one seeks them out. While amusing myself by gazing at the confectioners’ shops, and the pipe-makers surrounded by thousands of bowls in varying stages of completion, all arranged symmetrically, I arrived at the Mosque of Sultan Mahmud II (the Nusretiye Mosque) in Tophane, one of those focal places to which your feet carry you of their own accord, while your thoughts are occupied elsewhere. I set my watch at the kiosk, filled with pendulum clocks and others, which are often sited beside the mosques - it was a small elegant pavilion with openwork windows, through which the hour can be read from various dials which rarely agree with one another, so you may choose the time which pleases you best, and seems the most probable. These dials give both the Turkish and European local time, which in no way correspond, as the Orientals count from sunrise, a natural starting point, but one which varies according to the season.

These horological kiosks are usually adjoined by a fountain on which tin cups and spatulas hang from chains: a guard fills the cups from the basin within, and hands them to whoever wishes to drink. These fountains are almost all the work of pious foundations.