Théophile Gautier

Constantinople (1852)

Part VI: Elbicei Atika, Kadi-Keuï, Bulgurlu, Büyükdere

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 26: The Elbicei Atika.

- Chapter 27: Kadi-Keuï.

- Chapter 28: Mount Bulgurlu (Küçük Çamlıca Hill) - The Princes’ Islands.

- Chapter 29: The Bosphorus.

- Chapter 30: Buyuk-Déré (Büyükdere).

Chapter 26: The Elbicei Atika

On the Atmeïdan, opposite the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, near the Mecter Hané tent-depot (formerly assigned to the ‘mehterhâne,’ or music corps of the Janissaries), stands a Turkish house of rather fine appearance: it is the Elbicei Atika, or Museum of Ancient Ottoman Costume; this Museum, recently opened to the public, is fronted by a courtyard in which fresh vegetation flourishes and water, from a fountain, gurgles into a marble basin. Were there not an employee at the door, charged with collecting the price of the admission tickets, one could believe oneself in the konak (mansion) of some bey. Nothing is more pleasantly retrospective than this tranquil dressing-room of the old Turkish empire: soft nuances of shadow and the silence of a bygone age bathe its calm sanctuary; by setting foot in the Elbicei-Atika, one retreats from the present into the past.

On the landing, as an ensign or sentry, one first encounters a yeniçeri-kulluk-neferi that is to say a soldier of the new corps. In the actual days of the Janissaries, one could not pass by a post of that undisciplined militia without being ransomed more or less; one had to ‘cough up’, as they say, or be beaten, covered in mud, and heaped with insults. Here, a mannequin, whose head and hands are made of carved and painted wood, displays the old Janissary costume; this violation of the Muslim rule forbidding any reproduction of the human figure, is remarkable, and reveals a weakening of religious prejudice, no doubt brought about by contact with Christian countries; such a museum, in which nearly a hundred and forty figures may be viewed, would not have been possible in the past; now it shocks no one, and often some old Janissary who escaped the massacre (of 1826) dreams there, before these garmented replicas of his comrades-in-arms, and sighs over the good times that are no more.

This yeniçeri-kulluk-neferi possesses the air of a jovial scoundrel: a kind of fierce bonhomie breathes in his characterful features, which are accentuated by a long moustache; he seems capable of treating even murder humorously, and there reigns in his pose all the disdainful nonchalance of a privileged corps that thinks itself free to act as it wishes: legs crossed, he plays the louta (the latva, the Turkish version of the oud), a sort of three-stringed guitar, to entertain the corps in its moments of leisure. He wears a red tarbouch, around which is wrapped, like a turban, a piece of plain cloth; a brown jacket whose ends are tucked into a belt; and wide, blue, cloth breeches. Into the belt, at once his arsenal and a convenient pocket, are stuffed his handkerchief, napkin, tobacco-pouch, daggers, yataghans, and pistols. This custom of employing the belt as a hold-all is common to Spain and the Orient, and I remember watching a knife-fight, in Seville, in which the only thing slain was a melon in the faja (waistband) of one of the adversaries.

Before the yeniçeri, sits a small table covered with old Turkish small change - aspers, paras, and piastres, which are becoming rarer - representing the alms once extorted from the citizens of Constantinople - near it, roasting on a grill, are golden grains grated from corn-cobs, a meal with which Oriental frugality is content. I passed by fearlessly, since he was made of wood, and I had already paid ten piastres at the entrance.

Opposite this alms-seeking Janissary stand a few soldiers of the same corps, in almost similar costume. Once across the threshold, one finds oneself in an oblong room, dimly-lit and furnished with large display cases containing mannequins dressed with perfect care and scrupulous exactitude. This is the Philippe Curtius salon, the Marie Tussaud exhibition, of a vanished world. Here are gathered, like the antediluvian creatures in the Museum of Natural History, the individuals eliminated by Mahmud’s coup d’état. Here, lives again, in a kind of motionless afterlife, the whimsical and chimerical Turkey of turbans shaped like pastry-moulds, dolmans edged with catskin, high conical headdresses, jackets with suns on the back, and barbarously extravagant weapons, the Turkey of mamamouchis à la Moliere, of melodramas, and of fairy-tales. Only twenty-seven years have passed since the massacre of the Janissaries, yet it seems as if it were a century ago, so radical is the change. Through a violent exercise of will on the part of the great reformer, the old national forms have been annihilated, and costumes which were, so to speak, contemporary have become historical antiquities.

Looking behind the windows at these moustachioed or bearded heads, with fixed gaze, in life-like colours, grimacing away, illuminated by oblique and feeble shafts of light, one experiences a strange impression, a sort of indefinable unease. This crude reality, different from the conjurations of art, disquiets one, through the very illusion it produces; in seeking a transition from statue to living being, one encounters a corpse; these twilit faces, where no muscle quivers, end by frightening one, like the uncovered faces, plastered with make-up, of corpses borne past on their biers. And one comprehends, thus, the terror that masks inspire in children. These long lines of bizarre characters, maintaining the stiff and constrained poses granted them, resemble those folk, petrified through the vengeance of some magician, of whom the Oriental tale speaks. All that is lacking is the tall old fellow with a white beard, the only living being in that realm of the dead, seated on a stone bench at the entrance to the city reading the Koran. He may be represented, if you wish, though in a prosaic manner indeed, by the man who collects the price of the tickets at the door.

I cannot describe, one by one, the hundred and forty figures enclosed in the display cases on the two floors, several of which differ only in the imperceptible details of their costume’s cut or colour, and to do so would leave my text bristling with a crowd of Turkish words difficult to read due to their forbidding spelling. The task, moreover, has already been completed, in a manner as precise as it was brilliant, by Georges Noguès, son of the editor-in-chief (François Noguès) of the French Journal de Constantinople, and with a degree of care that a traveller forced to view the items briefly cannot rival. His catalogue allowed me to put names to the characters I remembered by sight alone, and I hereby do him due justice. This act of homage allows me to borrow with less scruple a few forgotten details.

The Elbicei-Atika consists mainly of costumes from the old house of the Grand Seigneur and various uniforms of the Janissaries. There are also mannequins of artisans, less in number, dressed in the old fashion.

The most senior official of a seraglio is naturally the chief of the eunuchs (the kizlar agha). The one imprisoned behind the windows of the Elbicei-Atika, as a specimen of the species, is very splendidly dressed in a pelisse of honour, of flowery ramage brocade, over a fine tunic of red silk, and large trousers held at the waist by a cashmere belt. He wears a red turban with a muslin twist, and yellow morocco-leather boots.

The grand vizier (the sadrazam) has a turban of singular shape; conical at the top, edged beneath with four ribs, it is surrounded at its base with rolled muslin which is crossed diagonally and compressed by a narrow band of gold; he wears, like the chief of the eunuchs, a kürklü (fur-trimmed) kaftan (coat of honour) of brocade, adorned with red and green flowers; from his cashmere belt emerges the handle, carved and studded with jewels, of his khanjar (dagger). The shaykh al-Islam (chief scholar) and the kapudan-pasha (grand admiral) are dressed in almost the same manner, with the exception of the turban, composed of a fez of a rich piece of twisted fabric.

There is a thoroughly sacerdotal and Byzantine air about the splendidly strange garments of the seliktar-agaci, or chief of the sword-bearers; his turban, of a strange construction, grants him a vague resemblance to a pharaoh wearing the pschent (the double-crown of Upper and Lower Egypt), and its model seems to have been some hieroglyphic panel brought from ancient Egypt; his robe of gold brocade with silver motifs, cut in the shape of a dalmatic, recalls the priestly chasuble; the sultan’s sabre, respectfully enclosed in a purple satin case, rests on his shoulder. After him, there appears a figure dressed in a black robe (jubba) with the sleeves slit, and embroidered with gold, and wearing a fez; this is the bach tchokadar, a kind of officer charged with carrying the Grand Seigneur’s pelisses on his arm during his walks; then comes the tchaouch aghaci (chief usher), with his robe of gold cloth, his cashmere belt clasped with metal plates and from which springs a whole arsenal; his gold cap terminates sharply in a crescent, one horn in front, one horn behind, a fanciful style that brings to mind the lunar Isis; this chief usher, who would not be out of place at the palace gates of Thebes or Memphis, holds in his hand a steel rod with a bifurcated pommel, similar to a nilometer, another Egyptian resemblance; this rod is the badge of his function. An agha of the serai appears next, clad in a white silk robe tightened by a belt with gold clasps and surmounted by a cylindrical cap. And the mannequin over there, dressed in a similar manner, except for his gold headdress which flares out at the top in four curves, like a Polish lancer’s czapka, is a dilsiz (mute), one of those sinister executors of justice or of private vengeance who passed the fatal silk cord around the necks of rebellious Pashas, and whose silent appearance made the most intrepid pale.

After these are grouped the serikdji-bachi, to whom is entrusted the turbans of the Grand Seigneur; the cooks; the gardeners with their red caps, similar to those of Catalans, the crest forming a kind of pocket; the doorkeepers; the baltadjis (axe-bearers), with curly hair, and Persian caps; the soulak (guard) in apricot dolman and red trousers, like the tenor Giovanni Battista Rubini when he plays the role of the Moor of Venice (see Gioachino Rossini’s opera ‘Otello’); and the peyik (halberdier) in a violet robe, and a rounded cap surmounted by an aigrette of feathers opened in a fan. The baltadjis, the soulak and the peyik form the special guard of the Sultan and surround him on solemn occasions, at Bayram (Eid al-Fitr), at Kurban-Bayrami (the Feast of the Sacrifice), and when he attends ceremonies at the mosques.

The series is closed by two fancifully dressed dwarves. These little monsters with the faces of gnomes or kobolds are barely two and a half feet tall, and could take their place honourably alongside Perkeo of Heidelberg, the dwarf of the Elector Palatine Charles III Philip; Stańczyk, the dwarf to three kings of Poland; Maria Bárbola and Nicolasito Pertusato, the dwarves of Philip IV; and Tom Thumb, the gentleman dwarf. They are grotesquely hideous, and madness is revealed by their thick sneering lips, for the role of fool and dwarf readily merge; thought seems hampered in these ill-made heads. Supreme power has always loved its antithesis of supreme abjection. A deformed fool jingling the bells of his marotte (the fool’s sceptre with carved head) on the steps of the throne, provided a contrast which the kings of the Middle Ages could not do without: such is not quite the case in Turkey, where fools are venerated as saints, but it is always pleasant, when one is a radiant sultan, to have near oneself a kind of human ape to accentuate your splendour.

The first of the two wears a yellow robe, fastened with a gold belt, and on his head a kind of cap in the shape of a derisory crown; the second is dressed more simply, his little legs engulfed by wide Mameluke trousers, falling over his microscopic slippers, and bundled in a biniş (gown) with trailing sleeves; he looks like a child who has dressed, for fun, in his grandfather’s clothes. His turban, dark in colour, offers nothing of note. The post of royal dwarf has not fallen into disuse at the court of Turkey: it is still occupied there with honour. In my description of Bayram, I provided a sketch of Sultan Abdülmecid’s dwarf, a broadly-built but dimunitive monster, dressed as a pasha of the Reform.

Below the same window, one sees an agha afflicted by illness, being drawn along by his servants in a sort of wheelbarrow, somewhat reminiscent of Charles V’s sedan chair which is preserved in the Armeria in Madrid. Healthy aghas now ride in coupés manufactured by Georges Ehrler, or carriages made by Alexandre-François Clochez. Paris and Vienna send their masterpieces of coachwork to Constantinople, from which the talikas with their painted and gilded bodies, and the characteristic arabas drawn by large grey oxen, will soon vanish completely. Local colour is indeed disappearing from the world.

The rest of the Museum is furnished with the Janissary Corps, who are there in their entirety, as if Sultan Mahmud had not turned cannons on them in the Et-Meïdan Square. There are examples of every rank. But perhaps, before describing the costumes of the Janissaries, it would not be out of place to give an idea of their organisation.

The yeniçeri (new corps) was instituted by Murad IV, with the aim of providing himself with an elite guard, a special corps, on whose devotion he could count; the nucleus was initially formed from his slaves, and, later, was swelled with prisoners of war and recruits. This epithet of yeniçeri, we Europeans, not too familiar with the intonation of Oriental languages, corrupted to Janissaries, which has the defect of implying a different origin, seeming to mean guardians of the door.

The orta (corps) of the yeniçeri was divided into odas (barracks), and its various officers adopted culinary titles that are laughable at first sight, but nevertheless explicable. The soup-maker (çorbaçi), the cook (aşçı), the kitchen boy (karaculluçu), the water carrier (sakka), seem singular as military ranks. To match this culinary hierarchy, each oda, in addition to its standard, had as its ensign a cauldron marked with the number of the regiment. In days of revolt, these cooking-pots were overturned, and the Sultan turned pale in the depths of his Seraglio; for the yeniçeri were not always satisfied with a few heads, and revolt sometimes became revolution. Enjoying high pay, better fed, and strengthened by privileges granted or extorted, the Janissaries had ended by forming a nation within a nation, and their agha was one of the most important figures in the empire.

The example of an agha exhibited at the Elbicei-Atika, is superbly dressed: the most precious furs adorn his stiff gold pelisse, a fine Indian muslin encircles his turban; his cashmere belt supports a panoply of expensive weapons: damascene blades with jewelled pommels, and pistols with silver or gold butts inlaid with garnets, turquoises and rubies. Elegant slippers of artistically quilted yellow morocco leather complete this noble and rich costume, equal to that of the highest dignitaries.

Next to the agha, stands the santon (saint) Emin Baba Bektashi, patron of the corps; this santon blessed the orta of yeniçeri at its formation, and his memory remained highly venerated. His name was invoked in battles, in times of danger, and at supreme moments. Emin Baba Bektashi, being a holy personage, does not seek to impress one, like the agha, by the magnificence of his clothes. His costume, of the simplest, announces a renunciation of earthly vanities: it consists of a kind of white woollen frock tightened with a brown belt, and a fez of whitish felt somewhat similar to the caps of the Whirling Dervishes; this fez lacks a silk tuft, and is bordered with a small band of dark-coloured plush. His trousers, cut short at the knee, reveal the bony and tanned legs of a holy man. A small copper book-horn hangs from his hand. I am not aware of the meaning of that attribute.

Uniforms, as we understand them, were not a part of Ottoman military custom; moreover, fancy was generally given a free rein as regards the costumes of the yeniçeri; the ranks were distinguished by some odd sign or other, but the basis of the garment was derived from that worn by the Turks of their day. It would take the pencil of a lithographer, and the brush of an illuminator, rather than the pen of a writer, to render the various cuts and nuances of fabric, all those details which, amidst an overloaded and laborious description, are never very clear to the eye of the reader, however great the effort one makes; I am surprised that not one of the numerous artists who visit Constantinople, has been sufficiently curious as to depict, in an album of watercolours, this precious collection; one could obtain, and with little difficulty, the firman necessary to undertake the work in the costume gallery, and the attendant sales would be assured, especially now that minds are turned towards the Orient.

While awaiting the production of such drawings, let me note in passing a few oddities; among others, a baç karaculluçu, or head-scullion, whose rank corresponds to that of lieutenant of a company, and who bears on his shoulder, as a badge of his dignity, a gigantic ladle, which one might think borrowed from the dresser of Gargantua (see Rabelais’ ‘Gargantua and Pantagruel’) or Camacho (see Cervantes’ ‘Don Quixote: Camacho’s Wedding’). This strange weapon ends in a spearhead, doubtless to associate the idea of war with that of cooking; next a chatir (runner), whose head a braid-maker seems to have used to twine a long piece of white ribbon: the innumerable knots that the fabric makes forming a rim similar to the wings of a rounded hat; and a yeniçeri-üstaçi (senior officer), flanked by two acolytes and decked out in the most bizarre costume imaginable.

This officer is covered in enormous round metal plates, as large as saucepan lids, attached to his belt, against which other square plates, nielloed, chiselled and of curious work, clank and ring; from the hilt of his sabre hangs a large bronze bell like the one hung around the neck of a leading donkey in Spain; his headdress, rounded into a cap like the upper part of a helm, is adorned with a copper rod similar to that seen on certain morions (open-faced helmets) to protect the nose against sabre blows, and from the nape of his neck a stream of grey cloth escapes, which spreads out behind; broad red trousers complete this outfit which looks as uncomfortable as it is baroque. The heralds at ancient tournaments cannot have been more hampered in their massive armour than this unfortunate yeniçeri-üstaçi in his parade-dress; The orta sakaçi (chief of the water-carriers) is no less originally dressed: his round, wide, waistless jacket, cut like a tabard, is clad with interlocking scales of copper; on his shoulders, two protruding bars, covered with metal scales, frame his head in a bizarre manner; a leather water-skin is attached to his back by straps; on his belt is a martinet - a cat o’ nine tails. Further on, two officers carry the orta’s cauldron on a long stick passed through its handle. On this cooking-pot, characters in relief mark the number of the regiment. A detailed description of the candle-lighter, the begging-bowl carrier, the baklava-carriers and the gracioso (entertainer), with his bearskin and his tarabouk (goblet-drum), would take too long; Let me simply mention the various figures of kombaradji (bombardiers) forming part of the corps founded by Humbaraci Ahmet Pasha (Claude Alexandre, Count of Bonneval), a famous renegade from the French army, whose tomb still exists at the tekke of the Whirling Dervishes of Pera, and who served as a soldier of the Nizam-i Cedid (New Order; the reformed military corps), instituted by Sultan Selim III to counterbalance the influence of the Janissaries. It is from the time of the corps’ formation, from the remains of the militia of Saint-Jean-d’Acre, that the introduction of this uniform into the Ottoman army dates. The dress of the Nizam-I Cedid closely resembles that of the zouaves and spahis of our army in North-Africa; a few samples of Greek, Armenian, and Arnaut (Albanian) costume complete the collection.

Traversing the rooms of the Elbicei-Atika, gazing at those cabinets populated by the ghosts of bygone times, one cannot help feeling somewhat melancholy, and one is led to wonder if it is not an involuntary prescience that has encouraged the Turks to create a museum celebrating this ancient national identity of theirs, which is so seriously threatened today. Current events seem to grant a prophetic meaning to the studious attempt to record, in Europe, the physiognomy of the old Ottoman empire, almost lost to Asia-Minor.

Chapter 27: Kadi-Keuï

A walk in Kadi-Keuï is a pleasure that the inhabitants of Pera rarely deny themselves on feast-days, especially those folk who are not yet rich enough to own a country house on the Bosphorus amidst the summer palaces of the beys and pashas.

Kadi-Keuï (‘village of the judges’) is a small town on the Asian shore facing the Seraglio, at the point where the Sea of Marmara narrows to form the mouth of the Bosphorus. On the site of what is now Kadi-Keuï, Chalcedon once stood, the city built by the Megarians under the quasi-legendary Archias, a little after the twenty-third Olympiad (688BC), some six hundred and eighty-five years before Jesus Christ; which is already a respectable degree of antiquity. However, some authors attribute the foundation of Chalcedon to a son of the soothsayer Calchas, on his return from the Trojan War; others to colonists from Chalcis, in Euboea, who earned their new city the epithet of the ‘City of the Blind’, for having chosen to build there, when they could have occupied the site over which Byzantium later spread. This reproach seems hardly deserved these days, for from Kadi-Keuï one has the most admirable view in the world, Constantinople unfolding, on the other shore and through the silvery gauze of a light mist, its magnificent domes, its cupolas and minarets, its mass of colourful houses, interspersed with clumps of trees. If one wishes to enjoy a panoramic view of Cologne, one must visit Deutz, on the opposite bank of the Rhine; to contemplate a fine prospect of Stamboul, there is no better way than to drink a cup of coffee in the port of Kadi-Keuï.

There are two modes of transport for making the short crossing, a caique, or the steamboat, which moors near the wooden bridge at Galata. As the journey takes a while, and the current is swift, the latter, the pyroscaphe, is generally preferred. I have used both means, the steamboat being more amusing for the traveller, in that it presents, crowded in a narrow space, a gathering of interesting types who seem as if posed before one. The separation of the sexes has entered so much into the Turkish way of life, that the deck of the steamboat is reserved for female passengers and forms a kind of harem where the Turkish women gather. The Armenian and Greek ladies, when they are alone, also take their places there. The whole deck is covered with low stools, on which one sits, knees to chin; waiters circulate carrying glasses of water or raki, chibouks and cups of coffee, sweets and little pastries; for in Constantinople there must always be something to nibble on, and sober officials will stop at a street corner to consume a slice of baklava or watermelon if they are hungry.

At the stern, stood a half-dozen Muslim women, led by an old crone and a black North African women; their fairly-transparent muslin yashmaks revealed pure and regular features, and through the gap large wild black eyes shone, surmounted by thick eyebrows linked by sürmeh (kohl): their noses, beneath their veils, described a quite aquiline curve, and their chins, perpetually under pressure, receded a little: it is a fault in Turkish beauties; when they are unveiled, the skin surrounding their eyes, which is the only portion of the face exposed to the air, is of a much browner tint than the rest of the skin, and looks like a small tan mask whose effect is to singularly enhance the mother-of-pearl of the sclera (the whites of the eyes).

‘But how did you discover this detail?’ the reader will doubtless ask, scenting some affair. In the least Don Juanesque way in the world: wandering through the cemeteries, I occasionally surprised, unwittingly, a woman who was adjusting her yashmak, or had left it open because of the heat, trusting in the solitude of the place; that is all.

These Turkish ladies, who appeared to belong to the middle class, had light-coloured and spotlessly clean feredjes, and their legs, smoothed by the preparations employed in the Oriental baths, gleamed like marble between their taffeta leggings and their yellow morocco-leather boots. The legs were generally strong; one should not seek in Turkey that slenderness of the extremities displayed by Arab peoples. One of these women was nursing a child, taking more care to cover her face than her breast, swollen with milk and marbled with blue veins, which the infant’s pink mouth was sucking at, with the nonchalant caprice of sated appetite.

Near the Muslim group sat three beautiful Greek women, their hair charmingly coiffed according to the fashion of their nation; a scrap of blue gauze, dotted with a few metal spangles, covered the back of their heads; their hair, divided in wavy bands like that of antique statues, flowed down the sides of their temples, encircled at the point of departure, by an enormous braid of hair, forming a diadem like a feroniere (a headband, often set with a central gem). The braid is not always genuine, and some old matrons are casual in this regard, to the extent of it being of a colour other than that of their natural hair. A lady, seated not far from these beauties, displayed a spread of black tresses in which threads of white were visible, and a large reddish-blonde braid which had not the least pretension of being rooted to her skull.

Traditional costume is gradually disappearing; and the three young Greeks were dressed in the French style, though their hairstyles and embroidered silk jackets, similar to the caracos (thigh-length jackets with tight sleeves) of our elegant ladies, endowed them with a sufficiently picturesque air. Their pure, clearly-defined features showed that the Greek types that informed Classical art were simply copies from nature. The human imagination is incapable of originating a single thing, even the monstrous. One could find, without having to search hard, living models akin to those of Phidias, Praxiteles and Lysippos, among the daughters of Eleusis and Megara. Those three lovely girls on the steamboat’s deck were like a triad of virginal Graces.

During the crossing, everyone was smoking furiously, and a thousand bluish spirals joined the black steam from the funnel; the boat, heavily burdened on deck and lightly ballasted in the hold, pitched horribly, and if the voyage had lasted a quarter of an hour longer, there would have been many cases of seasickness, though the water was as smooth as ice.

At last, the Bangor, as this dreadful vessel was named, drew up against the stone jetty, displacing a flotilla of caiques, and we disembarked. What one might call the ‘port’ of Kadi-Keuï, if the word were not perhaps over-ambitious, is lined with Turkish, Armenian and Greek cafés, always filled by a motley crowd. The Perotes and the Greeks drink large glasses of water whitened with raki, the local absinthe; the Muslims swallow small sips of cloudy coffee; the Perotes, Greeks and Turks, without dissent, snort the rose-water from the crystal carafes of their narghiles, as polyglot cries of ‘A light!’ rise above the dull hum of conversation.

Nothing is more pleasant than to inhale the steam from the tömbeki (tobacco), while seated on the outdoor sofa of one of these cafés and gazing at the crenellated walls of the Seraglio, the houses of Psammathia (Samatya), and the massive form of the Castle of the Seven Towers, rendered bluish by distance, on the opposite, European shore; but it was not to enjoy that spectacle that I chose to visit Kadi-Keuï.

I had been invited to lunch by Ludovic, an Armenian from whom I had bought Persian slippers, Lebanese tobacco pouches, scarves of Brousse (Bursa) silk woven with gold and silver, and some of those Oriental trinkets without which a traveller arriving from Constantinople is not welcome in Paris. Ludovic owns one of the finest antique shops in the bazaar, of which I have spoken at length in the appropriate place, and he has made a charming home for himself in Kadi-Keuï. Like the merchants of the City of London, those of Constantinople spend the day in their shops, and return each evening to their villa or cottage where they live a family life, leaving all thoughts of business behind, on the threshold.

I followed the main street of Kadi-Keuï to the end, according to the directions I had been given; it is fairly picturesque with its painted houses, its projecting chambers, its overhanging floors, its moucharabias with dense grilles and its more modern dwellings where one can witness the results of a leaning towards English or Italian taste. A few white facades, here and there, interrupt the motley array of Armenian and Turkish buildings, and produce not too bad an effect. On the steps of the open doorways beautiful young women were grouped, or seated, who did not flee one’s gaze; talikas, containing family parties from the countryside, rolled joltingly over the stony paving; Turkish horsemen passed on their Barbary horses, followed by a servant on foot, one hand placed on the rump of his master’s mount; Priests, dressed in purple robes similar to those of our college professors, and wearing a judge’s mortarboard from which hung a long veil of black gauze, walked with serious steps, stroking their curly beards; animation reigned everywhere.

Once you have crossed the main street, the houses become sparser, and are surrounded by larger gardens. You follow long white walls or plank fences above which the thick leaves of fig trees project in masses, or the wild twigs of garlanded vines.

After walking a while, I saw a white door with a blue frame: it was Ludovic’s residence; I entered, and was received by a charming woman with large black eyes, and a youthful, elongated oval face, displaying the typical features of the Armenian people, one of the finest types in the world, and one which I might prefer to the Greek, if the curve of the nose did not become rather too aquiline with age.

Madame Ludovic spoke only her mother tongue, and the conversation between us naturally faltered after the first greetings; I know of nothing more annoying than such a situation, however natural it might be. I thought myself the greatest fool in the world in not knowing Armenian; and yet one can, without a neglected education, be ignorant of that idiom. I reproached myself for not having undertaken, like Lord Byron, a preliminary study of the language at the Mekhitarist (Armenian Catholic) Monastery of Saint Lazarus in the Venetian lagoon; but, in conscience, I could not foresee that I would lunch one morning at Kadi-Keuï with a pretty Armenian woman who confessed to neither French, Italian, nor Spanish, the only languages I understood. With a delicate, feminine gesture, Madame Ludovic, cutting short our mutual embarrassment, led me to a low-ceilinged room where her two beautiful children were playing on a mat. Surely, now that contact between the most diverse peoples is so easy to achieve and so rapid, we should adopt a common, universal, catholic, language, French or English, for example, in which to understand one another, because it is shameful for two human beings to find themselves, vis-à-vis one another, reduced to the state of appearing both deaf and dumb. The ancient curse of Babel should be revoked in a civilised world.

The arrival of Ludovic, who speaks French most fluently, restored my use of language, and before lunch he showed me round his house: one could not imagine anything fresher and more attractively simple; the walls and ceilings of the rooms, with their panels and woodwork, were painted in light colours, lilac, sky-blue, straw-yellow, and chamois, bordered by white frames; fine esparto mats from India, replaced in winter by soft carpets from Isfahan and Smyrna, covered the floors; sofas covered with old Turkish fabrics, with unusual and original designs, highlighted here and there with gold and silver threads, and tiles of Morocco leather, set at every corner, tempted one to laziness. A pipe-rack, the pipes with stems of cherry and jasmine, enormous amber mouthpieces, and pink enamelled and gilded clay bowls, and Chinese porcelain pots filled with blond and silky tobacco, promised the smoker the delights of kief (pleasant rest, with or without the partaking of cannabis); some of those small tables inlaid with mother-of-pearl, like low stools, on which are placed trays bearing pots of jam and sorbets, completed the furnishings.

As it was very hot, we lunched in the open air under a sort of portico facing the garden planted with vines, fig-trees, and pumpkins. Our meal consisted of fish, fried in oil of a particular kind called scorpion-oil in Constantinople, mutton-chops, cucumbers stuffed with minced meat, little honey-cakes, grapes, and other fruit, all washed down with two sorts of Greek wine, one sweet with a slight muscat-grape taste, the other rendered bitter by an infusion from pine cones - a recipe from antiquity - and not unlike Turin vermouth.

The food was brought by an eager little serving-girl of thirteen or fourteen years old, whose bare legs made her wooden soles click on the pebbled mosaic with which the courtyard was paved. She carried the dishes from the stove on which they were ministered to by a large, pot-bellied Armenian with a ruddy face and a parrot’s beak of a nose, who was most talented, in a way; for I have eaten nothing better than the stuffed cucumbers prepared by this Asiatic Carême, to whom I express here the satisfaction of a grateful stomach. As culinary pleasures are rare in Turkey, it is well to take note of them.

The meal over, we retired, to take coffee and smoke a pipe, under the large trees which picturesquely border the steep coast of the bay; musicians screeched out some kind of plaint with those guttural intonations, bizarre cadences, and melancholy nasalizations which at first make you feel like laughing, and which end by placing you under a spell after listening to them for a while; the orchestra consisted of a rebab (stringed instrument), a Dervish flute, and a tarabouk (drum). The rebab player, a big Turk with a bull’s neck, nodded his head with an air of inexpressible satisfaction, as if intoxicated by his own music; between his two thin acolytes, he looked like a tumble-toy between two slender Japanese figures.

When we had listened sufficiently to the song of the Janissaries, and the legend of Skanderbeg, we were seized by the idea of attending a performance that the Armenian and Turkish comedy troupe were giving at Moda-Bournou (now Kadikoy-Moda), very close to Kadi-Keuï.

On my return from the Orient, I penned, in a theatrical review, an analysis of the farce of Franc et Hammal, which I expect the readers of La Presse have forgotten. The matter in hand was a tale of a mysterious beauty, a princess, Boudroulboudour, whose veiled charms, betrayed by the indiscretion of her followers, cause great havoc among the population. Primitive theatre does without sets, quite readily, the naive imaginings of the spectators providing them. Thespis (the ancient Greek poet and actor) played his role on a cart, with wine-lees for make-up, and Shakespeare’s great historical dramas required no other staging than a post bearing in progression the inscriptions: Castle - Forest - Chamber- Battlefield, according to the scene. At Moda-Bournou, the theatre was an area of beaten earth, shaded by trees, and encircled by the carpets of spectators seated in the Oriental style, and a latticed hut in which the women stood. No wings, no backdrop, no ramp was needed for the present performance ‘Sub Jove crudo’ (under the open sky).

A canvas tent, similar to the one in which the puppet Guignol makes Polichinelle struggle with the cat and the gendarme, represented the harem for easily-satisfied minds. A young rogue, in a yashmak and a tangle of veils like a Turkish lady, entered it, affecting languid poses, a lascivious waddle and the goose-like gait that obese Muslim women possess when entangled in their large yellow boots, or tottering on their pattens. His entrance caused much laughter, and rightly so, for his imitation was comically exact.

Once this beauty had taken ‘her’ place in the tent the suitors arrived in crowds to strum their guzlas (single-stringed instruments) beneath the window through which her head sometimes leaned, revealing two large, heavily blackened eyebrows, and two violent patches of red beneath the eyes: the slaves of the house, armed with clubs, made frequent sorties, and thrashed her adorers, to the great jubilation of the assembly.

It was not the woman whose voice replied to the suitors, but a little old man, all mummified, furrowed and wrinkled, his face framed by a short white beard, whom I might best compare to those coloured terracotta figures, representing yogis or fakirs, that one often sees in the windows of the curio shops on the Quai Voltaire. This grotesque sixty-year-old, lurking at the back of the tent, sang in falsetto, in an impossibly high pitch, quavering airs intended to imitate the woman’s voice.

At these shrill yelps, the suitors swooned with delight, believing they heard the music of paradise; they made, through the intermediary of the young ‘woman’, who laughed beneath her veil, the most passionate declarations and the most extravagant offers to this atrocious old man; the public, in full awareness of their error, squirmed with laughter at the contrast between the words and the person to whom they were addressed. Turkish, according to those who know it well, lends itself, more than any other language, to punning and equivocation; a slight difference of emphasis is enough to change the meaning of a word, and render it comical or obscene, and it is a resource which the actors never fail to employ, no less than do the puppeteers who perform the Karagöz plays.

A trio of rejected lovers forgo what little brains they have and are each afflicted by a tic particular to them: one perpetually moves his head backwards and forwards like those wooden birds set moving by a ball hanging at the end of a thread; the other, to all the questions he is asked, answers with a somersault and an imperturbable bim bom, bim bom, paf ; the third bears a lantern, hung from the end of an iron rod attached to his turban, and inserts this lantern into every situation where it is not needed, which leads to squabbles, volleys of blows from a stick, hair-tugging, and tumbles with all four limbs in the air, of which the Théâtre des Funambules would be jealous.

Finally the Çelebi (gentleman), the Count Almaviva (see Giaochino Rossini’s ‘The Barber of Seville’), the tenor, the victor, he who has only to show himself to triumph over every beauty, appears; he gives the suitors a general thrashing; Kuchuk-Hanem, Nourmahal, or Mihrimah (or the name, which I forget, of some other beauty who was locked in a tower), blushes, is troubled, opens her veil a little and answers, this time as herself, with a good strong boy’s voice, hoarse with the change due to puberty; the instruments rage; young Greeks dressed as women come forward and imitate the lascivious movements of ghawazis and bayadères, to indicate the wedding feast. At least that is what I thought I understood, from the gestures of the actors, and their outward actions. Perhaps I was as completely mistaken as the listener who on hearing a few bars of a pastoral symphony and mistaking them for those of an oratorio of the Passion, thought the composer’s rendering of the call of a quail in the wheat the sighs of the dying Jesus.

Chapter 28: Mount Bulgurlu (Küçük Çamlıca Hill) - The Princes’ Islands

The theatrical farce over, I hired a talika in order to visit Mount Bulgurlu (Küçük Çamlıca Hill) which rises some distance from Kadi-Keuï, a little behind Scutari (Üsküdar), and from the top of which one enjoys an admirable panoramic view of the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara.

The Turks, though properly speaking they have no art, since the Koran prohibits, as idolatry, the representation of living beings, have nonetheless, and to a high degree, a feeling for the picturesque. Wherever there is in a place a beautiful retreat, or a smiling perspective, one is sure to find there a kiosk, a fountain and a group of osmanlis enjoying kief on their unfurled carpets; they remain there for hours in perfect immobility, fixing their dreamy eyes on the distance, and chasing from time to time, at the corner of their lip, a wisp of bluish smoke. Mount Bulgurlu is frequented mainly by women, who spend days there beneath the trees, in small groups or harems, watching their children play, chatting among themselves, drinking sherbet, or listening to the strange music of itinerant singers.

My talika, drawn by a good horse, its driver, on foot, leading it by the bridle, first followed the edge of the sea, the water often brushing its wheels, skirted the houses of Kadi-Keuï, scattered along the coast, cut across the large parade ground of Haidar-Pasha, from which the pilgrims bound for Mecca set out each year, crossed the immense cypress grove of the Field of the Dead, behind Scutari, and began to climb the rather steep slopes of Mount Bulgurlu by a path furrowed by ruts, bristling with pieces of rock, often blocked by tree-roots, and strangled by houses projecting on to the public highway; for, it must be admitted, the Turks are, as regards the construction of viable roads, profoundly careless. Two hundred carriages a day will by-pass a stone in the middle of their path, or crash against it, without a single driver thinking of disturbing the obstacle; but despite the jolts and the enforced slowness of the journey, the road was extremely pleasant, and very lively, to view.

Carriages followed or overtook each other: the arabas, travelling at the measured pace of their oxen, pulled along groups of seven or eight women; the talikas held four, seated facing each other, their legs crossed on the boards, all extremely well-dressed, their heads adorned with diamonds and other gems, which could be seen shining through the muslin of their veils; sometimes, a favourite of a pasha would spin by in a modern brougham. Although it is perfectly natural, it is always strange to see, at the window of a low coupé, a woman from the harem, wrapped in her oriental draperies, instead of the familiar marble visage of some girl observing the Champs-Élysées; the contrast is so abrupt it shocks like a dissonance in music. There were many horsemen and pedestrians, too, who climbed, more or less cheerfully, the steep slopes of the mountain, performing numerous zigzags on the way.

On a kind of plateau halfway up the hill, beyond which the horses could no longer go, stood a considerable number of carriages, examples of Turkish coachwork, which is always most delightful, waiting for their masters, and forming a most picturesque mix which an artist might have made the subject of a fine painting. I had my talika left in a place where I could find it again, and continued the climb. At intervals, on a kind of embankment forming a terrace, in the shade of a clump of trees, stood an Armenian or Turkish family, recognisable by their black or yellow boots and their more or less veiled faces; when I say family, it is understood that I am speaking only of the women. They are never accompanied by the men who congregate separately.

Kahwedjis, with their portable stoves, had installed themselves on the summit of the hill, also sellers of water and sherbet, and traders in sweets and pastries, the obligatory accompaniment to all Turkish pleasures. Nothing could be more pleasant to the eye than the women dressed in pink, green, blue, and lilac, like flowers enamelling the grass as they breathed the cool air in the shade of the plane trees and sycamores; for, though it was very hot, the elevation of the site, and the sea breeze, maintained there a delightful temperature.

Young Greek women, hair crowned with a diadem, had taken one another by the hand and were turning to and fro to a vague and gentle tune like to Félicien David’s Ronde des Astres. Against the clear background of sky, they resembled the Procession of the Hours in the fresco (‘Aurora’) by Guido Reni, in the Rospigliosi Palace in Rome.

The Turkish women regarded them rather disdainfully, not comprehending why people would dance for pleasure, let alone thinking of dancing themselves.

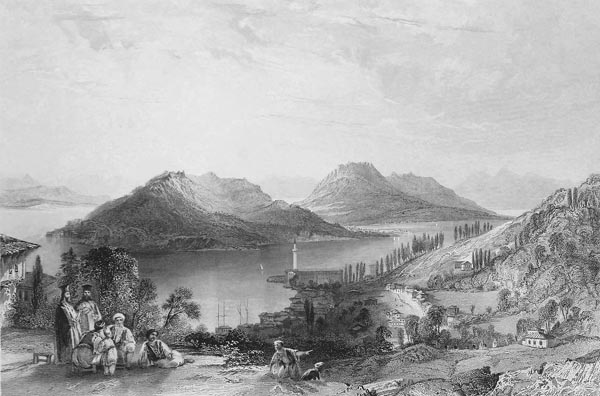

I continued to ascend and reached the clump of seven trees which crowns the mountain like a plume; from there, one’s eye commands the entire course of the Bosphorus and looks over the Sea of Marmara speckled by the Princes’ Islands, a radiant and marvellous spectacle. Seen from the heights, the Bosphorus, shining in places between its dusky banks, presents the appearance of a succession of lakes; the curves of the shoreline, and the promontories which advance into the waters, seem to strangle and enclose it from near to far; the undulations of the hills which border this marine flow are of an incomparable elegance; the serpentine line which follows the torso of a beautiful reclining woman, and accentuates her hips, possesses no smoother or more voluptuous a grace.

A silvery transparent light, tender and clear as a ceiling by Paolo Veronese, bathes this immense landscape. To the west, on the European shore, lies Constantinople with its lacework of minarets; to the east, stretches a vast plain marked by a track that leads to the mysterious depths of Asia; to the north, is the mouth of the Black Sea and the Cimmerian regions; to the south, Mount Olympus (Uludağ, in Bursa province), Bithynia, the Troad and, to the inward eye that pierces all horizons, Greece and its archipelagos. But what most attracted my gaze was that great, bare, deserted countryside, over which my imagination raced, pursuing the caravans, dreaming of strange adventures and moving encounters.

I descended, after half an hour of silent contemplation, to the plateau occupied by the groups of smokers, women and children. A large circle had formed around a band of Gypsies who were playing the violin and singing ballads in the Caló language (of the Iberian Romani); their faces the colour of boot-flaps, their long bluish-black hair, their exotic and crazed air, their wildly disordered grimaces, and their picturesquely extravagant rags made me think of Nikolaus Lenau’s poem: ‘The Three Gypsies,’ seven stanzas to rouse a longing for the unknown, and the fiercest of desires for the wandering life. Whence came this ineradicable people, of which identical examples are found in all corners of the world, amidst the various populations through which they pass without mixing with them? From India, no doubt; a pariah tribe that could not accept their hereditary and fatal subjection. I have rarely seen a gypsy encampment without having the desire to join them, and share in their vagabond existence; the savage man exists forever beneath the surface of the civilised, and it only takes a minor circumstance to awaken that secret wish to escape from laws and social convention; it is true that after a week spent sleeping under the stars next to a cart and a fire in the open air, one would miss one’s slippers, upholstered armchair, bed with damask curtains, and especially those Chateaubriand fillets washed down with a fine Bordeaux ‘returned from India’ (having travelled there and back, supposedly enhancing the wine), or even quite simply the evening edition of La Presse ; but the feeling I express is no less real.

Extreme civilisation weighs on individualism and robs one, as it were, of oneself, in return for the general advantages it procures; thus, I have heard many travellers say that there is no more delightful a sensation than to gallop alone through the desert, at sunrise, with pistols in your saddle-belts and a carbine on your saddle-bow; no one watches over you, but no one hinders you either; freedom reigns in such silence and solitude, and there are only the heavens above you. I myself experienced something similar when crossing certain deserted parts of Spain and Algeria.

I found my talika and its driver where I had left them, and the descent began, a rather unpleasant operation, given the steepness of the slope and the state of the road, which I can only compare to a staircase in ruins, half- demolished in places. The sais held the head of his horse, which, at every moment, fell back on its hocks, and whose rump was forever nudged by the body of the carriage; my situation, seated in this box, was like that of a mouse being knocked against the walls of a trap to stun it; jolts that would have unhinged the most firmly-anchored heart sent me flying me forwards when I least expected it; so, although I was rather tired, I decided to descend and follow the carriage on foot.

Arabas and talikas full of women and children also made their descent from the Bulgurlu hill: there were bursts of laughter and voices at each new slope, and with every unexpected jolt a whole row of women fell against the opposite row, and rivals thus embraced each other quite involuntarily; the oxen, knees bent, braced themselves as best they could against the roughness of the ground, and the horses descended with the caution of animals accustomed to poor roads; the horsemen galloped freely, as if they were on the plain, sure of their Kurdish or Barbary mounts: it was a charming scene, joyful to the eye, and of a truly Turkish character; though a space of only a few miles separates the Asian from the European shore, the local colour is much better preserved, and one encounters far fewer Franks.

The road having become more or less smooth again, I climbed back into my carriage, to gaze out of the window at the painted houses and cypresses, and the turbes which lined the road and sometimes formed an island in the midst of the way, as St.-Mary-le-Strand does in London. My driver took me through Scutari, which we had skirted on the way, and the Haider Pasha training ground, then drove back along the shore to the landing stage of Kadi-Keuï, where the Bangor, preparing to sail, was belching clouds of black smoke into the blue of the sky.

The passengers’ embarkation involved a certain degree of tumult, accompanied by bursts of laughter; an almost perpendicular board serving as the bridge between jetty and boat. The ascent was quite tricky, and it was necessary, as well, to step over the gunwale, which produced a host of little modest, virtuous but rather comical antics; during this perilous passage, more than one European garter gave up its secret; more than one Asian calf betrayed its incognito, despite Turkish jealousy. I only mention this little incident à la Paul de Kock as an example of morality at play; by extending the board three or four feet further, this challenge to feminine modesty would have been avoided; but no one thought of doing so.

Night was falling when the Bangor unloaded its human cargo at the Galata landing-stage, after having swayed to and fro like a swing.

As I was beginning to exhaust the curious sights of Constantinople, I resolved to go and pass a few days among the Princes’ Islands, a pretty archipelago scattered over the Sea of Marmara, at the entrance to the Bosphorus, which offers a healthy and pleasant trip. The islands are nine in number: Büyükada (Prínkēpos), Heybeliada (Chalke), Burgazada (Antigone), Kinaliada (Prote), Sedef (Terebinthos), Yassiada (Plate), Taysan (Neandros), Kasik (Pita), and Sivriada (Oxeia) plus two or three other islets. Büyükada is the largest and most frequented of these flowers of the sea, which are illuminated by the cheerful Anatolian sun, and fanned by the fresh morning and evening breezes. One reaches them by means of an English or Turkish steamboat in about an hour and a half. The Turkish boat I had chosen had a singular mechanism, the like of which I have never seen anywhere else: the piston, projecting from the deck, rose and fell like a saw operated by two tall sawyers. In spite of this, the English boat outdistanced us, and well justified the name Swan inscribed on its stern in gold letters. Its white hull sped through the water as the real bird does.

The coast of Büyükada presents itself, when one arrives from Constantinople, in the form of a high bank with reddish escarpments, surmounted by a line of houses; wooden ramps or steep paths, tracing acute angles, descend from the cliff to the shore, which is bordered by wooden bathing huts. The firing of a gun announces that the steamer is in sight, and immediately a fleet of caiques and canoes detaches itself from the land to meet the passengers, since the shallowness of the water does not allow boats with a keel of more than a few feet to approach.

A place had been reserved for me in advance in the only inn on the island: a cool, clean wooden house, shaded by tall trees; from its windows the view extended across the sea into an infinite depth of horizon.

Opposite, I could see the island of Heybeliada, its Turkish village reflected in the sea, its mountain capped by a Greek monastery. The water lapped at the escarpment, at whose foot the inn was perched, and one could descend to it in slippers and a dressing gown, and take a delicious bathe, the sandy bed extending quite far out.

At the table d’hôte, which was very well done, a lady was seated, majestically, behind whom stood a superb Greek servant in a Palikar costume embroidered all over in gold and silver, who served his mistress with a seriousness worthy of an English servant. This characterful fellow, more suited to loading blunderbusses and carbines behind a rock than waitering, produced a rather strange effect: I cannot believe wine has ever been poured into a glass in so grandiose a manner. Malicious tongues went so far as to claim that his functions were not limited to this alone, but one should never believe more than half of what is said.

In the evening, the Armenian and Greek women adorned themselves, and promenaded in the narrow space between the houses and the shore: the heaviest and thickest of silk dresses spread in wide folds; diamonds sparkled in the moonlight, and bared arms were laden with those enormous gold bracelets with multiple chains particular to Constantinople, which adornment our jewellers would do well to imitate, since they make the wrist appear slender and flatter the hand.

Armenian families are as fertile as English ones, and it is no rare thing to see a large matron preceded by four or five girls, each one prettier than the next, and as many very lively boys; the hairstyles, and low-cut bodices, give this promenade the appearance of an open-air ballroom; a few Parisian hats are visible, as on the Prado in Madrid, but in small numbers.

In the cafés, which all have terraces overlooking the sea, people drink ices made with snow from the Bithynian Olympus (Mount Uludağ), sip small cups of coffee accompanied by glasses of water, and burn tobacco in every way imaginable: chibouks, hookahs, cigars, cigarettes, nothing is missing; the colourful silhouette-puppet Karagöz struggles behind his transparent screen, and delivers his lazzi (jests) to the sound of the Basque drum.

From time to time, a blue glow like that from an electric light strangely illuminates a house facade, a clump of trees, or a group of promenaders; one walker turns and smiles: it is some lover lighting a Bengal fire in honour of his mistress or his fiancée. There must be many lovers in Büyükada, because no sooner had one light died down than another was rekindled. I employ the word ‘mistress’, be it understood, as it was used in the age of gallantry, that is, a woman to whom one pays attention, in order to make her love one with the intention of marriage, and nothing else, because the moral law is very rigid here.

Little by little, all return home, and towards midnight the whole island sleeps a peaceful and virtuous sleep; this promenading plus the sea-bathing constitute the pleasures of Büyükada; to vary them, I made a long excursion by donkey into the island’s interior, accompanied by an amiable young man of whom I had made the acquaintance at the table d'hôte; we first traversed the village, its market proving very pleasing to the eye with displays of strangely-shaped cucumbers, watermelons, Smyrna melons, tomatoes, peppers, grapes, and unfamiliar produce; then we followed the shore, sometimes closely, sometimes from afar, through plantations of trees, and cultivated fields, to the house of a priest, a very good-natured fellow, who had raki and glasses of iced-water served to us by a beautiful girl; then, rounding the island, we came to an old Greek monastery, quite dilapidated, now serving as a hospital for the insane.

Three or four unfortunates in rags, with haggard complexions and a morose air, dragged themselves, accompanied by the clatter of their irons, along the walls of a courtyard flooded with sunlight. At the back of the chapel, for a baksheesh of a few piastres, we were shown inferior-looking icons, with a gold background and brown figures, such as are created on Mount Athos, according to the Byzantine model, for the use of Greek worshippers; inside, the Panagia showed her head and swarthy hands, according to custom, on cutouts of silver or silver-gilt plate, while the infant Jesus appeared as a little black babe, in a tri-lobed halo. Saint George, patron saint of the isle, vanquished the dragon in his long-consecrated pose.

The monastery’s situation is admirable: it occupies the platform of a rocky cliff, and from the summit of its terraces, one can plunge in reverie into the twin limitless blues of sky and sea. Next to the monastery, vaulted excavations, half-collapsed, show that it once covered a larger site, and displayed an earlier form of architecture.

The Princes Islands, from the Monastery of the Trinity

We returned by another, wilder route, amidst clumps of myrtles, and clusters of terebinths and pines, which grow naturally and which the inhabitants cut for firewood, and arrived at the inn, to the great satisfaction of our donkeys, who needed to be vigorously spurred and beaten so as not to fall asleep on the way, since we had made the mistake of not employing a donkey-driver, an indispensable person in a caravan of this kind, the Oriental donkey being very contemptuous of the bourgeoisie, and not at all impressed by their blows.

After four or five days, sufficiently edified by the delights of Büyükada, I set off for a trip on the Bosphorus, from the tip of Serai, as far as the entrance to the Black Sea.

Chapter 29: The Bosphorus

The Bosphorus, from Serai Bournou to the entrance to the Black Sea, is furrowed by a perpetual to-ing and fro-ing of steamboats, comparable to that of watermen’s boats on the Thames; the caïdjis, who formerly reigned as despots over its green and rapid waters, view the steamboats passing by with the same eye as postilions do railway locomotives, and regard Robert Fulton’s invention as wholly diabolical. However, there are obstinate Turks still, and cowardly giaours, who take caiques to ascend the Bosphorus, just as there are people among us who, in spite of the rail-tracks on both the left and right banks of the Seine, travel to Versailles in gondolas, and Saint-Cloud in coucou-carriages; yet, they are becoming rarer every day, and the Muslims are quite happy to travel by steamboat. The vessels even occupy their thoughts, and there is not a café or barber’s shop whose walls are not decorated with several drawings in which some naive artist has depicted, as best they could, a plume of smoke escaping from a funnel and paddle-wheels beating the frothing water.

I embarked at the Galata Bridge over the Golden Horn, the point of departure for the boats stationed there in great numbers, spitting out their black and white smoke which condensed to a permanent cloud covering the light azure of the sky. Neither London Bridge, nor the Hungerford suspension bridge (Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s footbridge of 1845), over the Thames, present a more animated scene, a more congested tumult, than this, the approach to which is very inconvenient, because, to reach the boats, it is necessary to cross the railing of the boat-bridge, step over planks, and traverse rotten or broken beams.

It is scarcely an easy task to sail from there; yet success is achieved, though not without bumping a little into neighbouring boats, and one sets off; a few strokes of the piston and the open sea is reached, then one glides freely, between a dual line of hills, villages, palaces, kiosks, and gardens, over lively water, mingling emerald and sapphire, in which your wake creates millions of pearls, beneath the loveliest sky in the world and through the bright sunlight which forms rainbows amidst the silvery mist of the paddle-wheels.

There is nothing comparable, in my experience, to this two-hour trip across a strip of azure which marks the boundary between two of the world’s continents, Europe and Asia, both visible at the same moment.

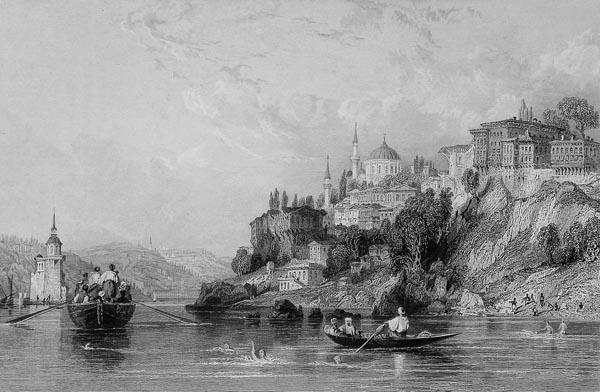

The Maiden’s Tower soon emerges, its white silhouette so charming in effect against the blue background of the waters: Scutari (Üsküdar), and Tophane appear in turn. Above Tophane, the conical verdigris roof of the Galata Tower rises, and on the slopes of the hill are the stone-built houses of the Europeans, and the colourful wooden huts of the Turks. Here and there the spire of a white minaret rises like a ship’s mast; surrounded by a few tufts of dark green; the massive buildings housing the various legations reveal their facades, and the Large Field of the Dead unfurls its curtain of cypress trees, against which the artillery barracks and the military college are clearly highlighted. Scutari the ‘golden city’ (ancient Chrysopolis), presents a somewhat similar spectacle; the black trees of a cemetery also serve as a background for the pink houses, and whitewashed mosques; on both shores, death looms darkly behind life, and each city is surrounded by a suburb of tombs; but that thought, which would sadden folk elsewhere, in no way disturbs the fatalistic serenity of the Orient.

Scutari — and the Maiden's Tower

On the European shore, the Ciragan Palace was now visible - a palace initiated by Mahmud II, and built in the European style (on the site of a former mansion), with a classical pediment, like that of the Chamber of Deputies in Paris, in the centre of which the Sultan’s cypher is intertwined in letters of gold, and two wings supported by Doric columns in Greek marble. I confess I prefer the Arab or Turkish architecture of the Orient; yet this grandiose construction, whose broad white staircase descends to the shore, creates a rather beautiful effect. In front of the palace, a splendid caique with a purple awning, gilded and painted throughout, and bearing a silver bird at the stern, awaited His Highness.

Opposite, beyond Scutari, extends a line of summer palaces, coloured apple green, and shaded by plane-trees, strawberry-trees, and ash-trees, the buildings cheerful despite their latticed windows, and recalling aviaries rather than prisons. These palaces, ranged along the shore, their feet in the water, have rather the appearance of the Vigier Baths or the Deligny swimming-school, on the Seine. The Turkish villas on the Bosphorus often evoke this comparison.

Between Dolma-Baktché (Dolmabahce) and Beschick-Tash (Besiktas) rises the Venetian façade of the new palace built by Sultan Abdülmecid, of which I have given a particular description. Though its architectural style is not very pure, it is at least curiously and richly capricious, and its white silhouette, sculpted, carved, chiselled, and burdened with infinite ornaments, stands forth elegantly on the shore; it is indeed the palace of a caliph tired of Arab and Persian architecture, who, seeking an alternative to the five orders of architecture (as defined in Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola’s text ‘Regola delli Cinque Ordini d’Architettura’, 1562), is housed in an immense jewel of marble worked in filigree. Dolma-Baktché was formerly called Jasonion. It is there that Jason landed with his Argonauts, during his expedition in search of the Golden Fleece.

The steamboat hugs the European coast, where the landing-stations are more frequent; one can, on passing the Beschick-Tash café, see the smokers squatting in latticed rooms suspended over the water.

We soon left behind Orta-Kieuï (Ortakoy), and Kourou-Tchesmé (Kurucesme), which border the sea, and behind which rise, in undulating waves, hills dotted with trees, gardens, houses and villages of the most cheerful appearance.

From one village to another, palaces and summer residences stretch in an uninterrupted quay. The Valide Sultana (the Sultan’s mother), the Sultan’s sisters, the viziers, ministers, pashas, and noble personages, have all built charming dwellings there, in a perfect harmony of Oriental comfort, which bears no resemblance to the English version, but serves them well.

The palaces are of wood, with the exception of the columns, which are usually cut from a single block of Marmara marble, or pillaged from the remains of ancient buildings. But they are no less elegant in their transient grace, with their overhanging floors, projections and retreats, kiosks with Chinese roofs, trellised pavilions, terraces decorated with vases, and their fresh colour constantly renewed. Amidst the cedar-wood grilles, which cover the windows of the apartments reserved for women, round holes gape, akin to those made in theatre curtains through which the cast can inspect the auditorium and audience; it is through these that the nonchalant beauties seated on carpets, can watch the ships, steamboats and caiques sail by, without themselves being seen, while chewing mastic from Chios to keep their teeth white.

A narrow granite quay, forming a towpath, separates these pretty dwellings from the sea. Passing by, one feels, in spite of oneself, a vague desire to do as Hassan, Alfred de Musset’s hero, did (see his poem ‘Namouna’ of 1832, Canto I, verse XLII), and throw his cap over the windmills in order to take the fez.

Near Arnaout-Keuï (Arnavutköy), the water of the Bosphorus boils like a cauldron because of its rapid flow, called the mega reuma (the great current): the blue water flies like an arrow beside the stones of the quay; however robust their sun-tanned arms may be, the caïdjis feel the oar bend in their hands like the blade of a fan, and were they to fight against that imperious flow, the oar would shatter like glass. The Bosphorus is full of these currents, whose directions vary, that give it the appearance of a river rather than an arm of the sea.

In those reaches, a piece of rope is thrown from the boat to the shore; three or four men harness themselves to it like horses, and, bending their strong shoulders, tow the boat, whose prow carves out ribbons of white foam.

Once the rapids are passed, the oars are taken up again and the calmer water provides easy passage. At the foot of the houses, one frequently sees groups of three or four Turkish women, crouched beside their children at play; on the quay, young Greek ladies hold hands as they walk, and cast curious glances at the European traveller; men pass by on horseback, sailors drag a caique back into its vaulted boathouse; figures to view are rarely lacking.

My readers are now sufficiently familiar with the local architecture that there is no need of a further description of the houses of Arnaout-Keuï. I will, however, note as of interest some old Armenian dwellings painted black, formerly the obligatory colour, lighter hues belonging by right to the Turks, ox-blood red or antique red to the Greeks; today everyone can paint their house as they please, other than in green, the colour of Islam, of the hadjis and the descendants of the Prophet.

On the coast of Asia, more densely-wooded and shady than the European shore, villages, palaces and kiosks follow one another, a little less closely-packed perhaps, but still quite near to one another. These are Kous-Goundjouk (Kuzguncuk), Stavros (Istavroz)-Beylerbeyi, where Mahmud II had a summer residence built, Tchengel-Keuï (Cengelkoy), Vani-Keuï (Vanikoy) and, opposite Bebek, the Sweet-Waters of Asia (Goksu).

A charming fountain in white marble, embroidered with arabesques, and decorated with inscriptions in gold letters, and topped by a large roof with a pronounced overhang, and small domes surmounted by crescents, can be seen from the sea, highlighted against a background of opulent verdure, indicating to the traveller that favourite Ottoman promenade. A vast lawn, velvety with fresh grass, framed by ash-trees, plane-trees and sycamores, is encumbered, on Friday, by arabas and talikas, and there one can see the idle beauties of the harems stretched out on Smyrna carpets.

Black eunuchs, tapping their white trousers with the ends of their whips, walk between the crouching groups, watching for some furtive glance, some gesture of communication, especially if there is a giaour there trying to penetrate, from afar, the mysteries of the yashmak or the feredje; sometimes the women tie shawls to tree branches and rock their children in these improvised hammocks; others eat rose-jam or drink snow-water; some employ a narghile, or smoke cigarettes; all babble or gossip about the Frankish ladies, who are so brazen, who show themselves with their faces uncovered, and walk beside men, in the streets.

Further along the coast, Bulgarian peasants in their antique sayons, their bonnets surrounded by enormous fur crowns, perform their national dances in hopes of baksheesh. The kahwedjis prepare their coffee in the open air; Jewish tradesmen, their robes split at the sides, their turbans speckled with black like penwipers, offer various small items to the passers-by, with that humble air of the Jews of the Orient, always bowing from fear of being insulted; and the caïdjis seated on the edge of the quay, legs dangling, watch their boats from the corner of an eye.

It would take too long to describe, one by one, all those villages that follow one another, and resemble one another with nigh-imperceptible variations. A row of colourful wooden houses, like some unboxed toy-village from Nuremberg, is forever extending itself along a quay, or dipping its feet, at a stroke, in the water wherever a towpath is lacking, highlighted against a curtain of rich greenery from which rises the chalky minaret of a shrine, or a small mosque; beyond, the hills, their slopes gentle, and managed, rise harmoniously, washed with azure beneath the bright sky; sometimes one might wish for a steeper escarpment, an arid cliff, a bone of rock piercing the epidermis of the earth; for all is really too graceful, too cheerful, too coquettish, too well-combed; it would benefit, here and there, from a few bold, accentuated touches to serve as a foil.

At certain points along the shore, chicken-coops of a kind, of strange and picturesque construction are perched, each on a scaffolding of poles, in which fishermen stand, watching for the passage of shoals of fish, so as to announce the right moment to cast, and haul in, their nets; sometimes they happen to fall asleep and tumble head-first from their aerial perches into the water, where they drown without waking. Their sentry-boxes, similar to the nests of aquatic birds, seem to have been built expressly to provide foregrounds for artists.

At one point, the two shores are considerably closer together. Here is the place where Darius I led his army, during his expedition against the Scythians, over a bridge constructed by Mandrocles of Samos. Seven hundred thousand men marched across, vast regiments of the hordes of Asia, with their exotic faces, curious weapons, and fabulous accoutrements, cavalry-troops mingling with elephants and camels. On two stone columns, erected at the head of the bridge, were engraved lists of all the peoples marching in Darius’ wake. These columns rose on the very spot occupied by the fortress of Guzeldjé-Hissar (Guzelce Hisar, or Anadoluhisari) built by Bajezid I, Bayezid-Yilderim the Thunderbolt. Mandrocles, as Herodotus relates (in ‘The Histories’ Book IV, chapter 88) depicted this crossing on a board which he hung in the temple of Hera, on Samos, his native isle, with this inscription: ‘Mandrocles, having built a bridge over the fish-filled Bosphorus, dedicated the drawing to Hera; by carrying out this work of King Darius, Mandrocles procured glory for the Samians, and for himself a crown.’ The Bosphorus, at this place, is eight hundred metres wide, and it is this way that the Persians, Goths, Latins and Turks passed: the invasions, whether they came from Asia or from Europe, followed the same route, all those great overflows of peoples coursed along the same channel, marching in the wheel-ruts left by Darius.

The fortress of Europe, Rumelihisari, also called Boğazkesen (Cutter of the Strait), is a fine sight on the slopes of the hill with its white towers of unequal height and its crenellated walls. The three large towers, and the smaller one near the shore outline, in reverse, according to Turkish script, the four letters, MHMD, an abbreviation of the name of their founder, Mehmed II. This architectural rebus, not readily noticed, brings to mind the plan of the Escorial Palace, north of Madrid which, in turn, represents the gridiron of Saint Lawrence, in whose honour the monastery was built. One is only aware of this curiosity if informed of it beforehand. The Fortress of Europe faces the Castle of Asia (Anadoluhisari), which I mentioned before.

Near Rumeli-Hisar there is a cemetery whose tall black cypresses and white cippi are reflected gaily in the azure waters of the sea, at the sight of which one might wish to be buried there, so cheerful, flowery and perfumed is the place. The dead can surely feel no ennui, lying as they do in this fresh garden brightened by the sun, and animated by birdsong.

The steamboat, after passing Balta-Liman (Baltalimani), Steneh, Yeni-Keuï (Yenikoy), and Kalender, stops at Therapia (Tarabya), a town whose name means healing in Greek, and which justifies its medicinal appellation by the healthiness of its air; it is there that the French embassy has its summer palace. In the graceful little gulf which adjoins it, a golden cup filled with sapphires, Medea, returning from Colchis with Jason, went ashore, and there unpacked the box containing her philtres and magical drugs, hence the name of Pharmakia which Therapia formerly bore.

Therapia is a delightful place in which to stay; its quay is lined with cafés decorated with a certain degree of luxury, a rare thing in Turkey, as regards inns, pleasure-houses and gardens. In a passage leading to the landing stage, I noticed in the stones of the wall two marble torsos, one of a man dressed in an antique cuirass, the other of a woman, veiled in rather crude draperies, the barbarian builders having embedded them in the middle of the rubble like any common material to hand.

In the harbour the corvette Chaptal was anchored, commanded by Monsieur Poultier, whom I went to visit, and who received me with the affectionate good nature which is characteristic of him, and the exquisite politeness common to all naval officers.

The palace housing the French Embassy, which Pierre-Louis Renaud (architect of the Gare d’Austerlitz in Paris) ought to rebuild with more solidity, richness, and taste, is a large Turkish-style construction, all in wood and rammed earth, devoid of any architectural merit, but vast, airy, comfortable, cool, sheltered from the most violent heat of summer, and in the most admirable situation in the world.

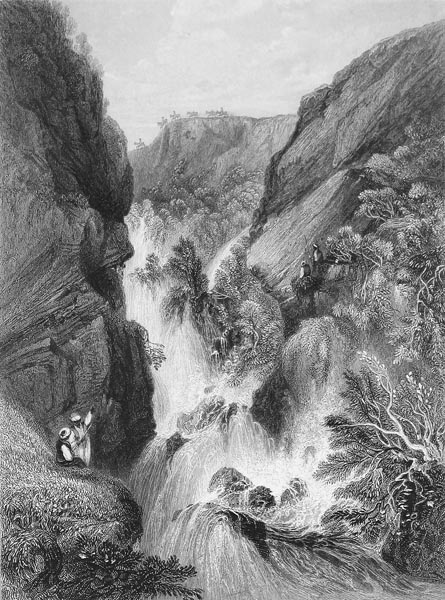

Behind the palace are terraced gardens, planted with centuries-old trees of prodigious height, endlessly agitated by the breezes of the Black Sea. From the upper embankment, one enjoys a marvellous perspective. The shore of Asia-Minor displays before your eyes the cool shades of the ‘Waters of the Sultana’, further away are the bluish heights of the Giant’s Mountain (Yuşa Tepesi), where tradition places the Bed of Hercules. On the shore of Europe, Buyuk-Déré (Büyükdere) reveals its graceful curve, and the Bosphorus, past Rouméli-Kavak (Rumelikavagi, on the European shore), and Anadoli-Kavak (Anadolu Kavagi, on the Asian shore), widens out beyond the Cyanean Islands (the Symplegades) of myth, identified with two small rocky islets, and is lost in the Black Sea. White sails come and go like seabirds, and the mind wanders in an infinite dream.

Chapter 30: Buyuk-Déré (Büyükdere)

Buyuk-Déré (Büyükdere), which can be seen from the terrace of Therapia (Tarabaya), is one of the most charming villages in which to enjoy oneself, in all the world. The coast is cut away at this point, and describes an arc against which the waves die in gentle undulations. Elegant dwellings, among which one notes the summer-palace of the Russian Embassy, rise on the shore, against a backdrop of green gardens, at the foot of the last ridges of hills which plunge to form the bed of the Bosphorus; the rich merchants of Constantinople own country-houses there to which, every evening, the steamboat brings them, their business affairs over, and from which they depart again each morning.