Théophile Gautier

Constantinople (1852)

Part IV: The Women, The City Walls, Balat, Bayram

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 16: The Women.

- Chapter 17: Breaking the Fast.

- Chapter 18: The Walls of Constantinople.

- Chapter 19: Balata (Balat) – Phanar (Fener) – The Turkish Baths.

- Chapter 20: Bayram (the Festival of Eid-al-Fitre, or Breaking the Fast).

Chapter 16: The Women

The first question that is asked of every traveller returning from the East is this: ‘And what of the women?’ Each person answers with a smile, more or less mysteriously according to his degree of fatuity, thereby implying a respectable number of fortunate encounters. Whatever the cost to my self-esteem, I humbly confess I have not the least indiscretion of this kind to record, and am forced, to my great regret, to forego relating any tale of amorous and romantic adventure. It would have been most useful, though, as a means of varying my descriptions of cemeteries, tekkes, mosques, palaces and kiosks: nothing embellishes a description of the traveller’s visit to the Orient better than the appearance of an old crone who, at the corner of some deserted alley, beckons you to follow her, and introduces you, by means of a secret door, to an apartment adorned with all the refinements of Asian luxury, where a Sultana, dripping with gold and precious stones, and seated on brocaded cushions, awaits you; she, whose smile offers a voluptuous promise soon to be fulfilled. Usually, the intrigue is resolved by the sudden arrival of her lord, who barely leaves you time to flee by a secret exit, unless the affair ends, more tragically, in an armed struggle and the descent, to the bed of the Bosphorus, of a sack in which a human form vaguely struggles.

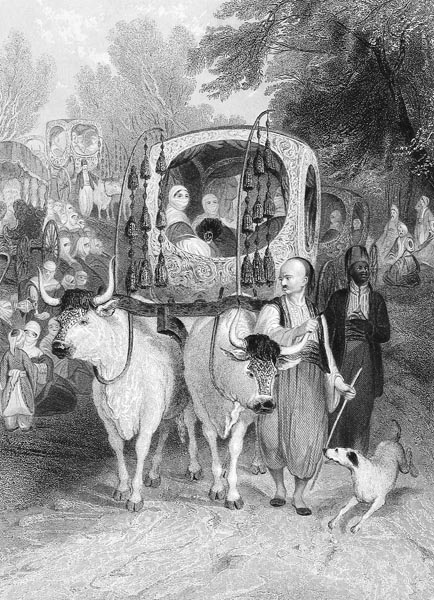

The Sultana in her State Arrhuba

This Oriental commonplace, suitably embroidered, always interests readers, especially female ones. Doubtless there are examples of some young, rich and handsome giaour, who knowing the language of the country thoroughly, and renting a small house conforming to Turkish custom, manages to conduct a love affair with a Muslim woman while running the greatest danger and risking her life; but they are few and far between, and for several reasons: firstly, whatever Molière may say (see his play ‘L’École des Maris’ Act I, Scene 2, and Act III, Scene 6), locks and grilles are materially quite effective obstacles; then there is the difference of religion, and the sincere contempt every believer holds for infidels, reasons to which should be added the difficulty or rather the impossibility of those preliminary meetings which lead to love. While, in France, there is a tacit conspiracy against the husband, all favour the amorous couple, at least by keeping silent, and none proclaim themselves arbiters of public morality, in Turkey, things are otherwise: a kavas, a hammal, a man of the people, who sees a Muslim woman talking to a Frank in the street, or simply signalling her awareness of him, falls on the Frank with kicks, punches, blows from a stick, a show of brutality which meets with general approval, even among the women. Mockery aimed at marital fidelity is unheard of; an instinctive and physical Turkish jealousy almost certainly preserves them from matrimonial incidents, so frequent among us, though jokes about wearing horns are as present on the Karagöz stage as that of the Théâtre-Français, and the word kerata (horned) is inserted in comedic disputes at every opportunity.

It is true that Turkish women go about freely, take walks at the Fresh Waters of Asia and Europe; parade in carriages at Haydarpasha, or in Bayezit square; seat themselves on the edge of the lawns of the Fields of the Dead of Pera and Scutari; spend entire days bathing or visiting their friends; attend the comedies of Kadi-Keuï, and watch the feats of strength performed by the acrobats of Psammathia (Samatya); converse beneath the arcades of the mosques; shop the Bezesten; and travel the Bosphorus in a caique or a steamboat; but they always have two or three companions beside them, or an African servant, or an old woman acting as duenna, or, if they are rich, a eunuch often jealous on the mistress’s behalf. When they are alone, which is rare, a child serves to guarantee respect, and, in the absence of a child, public morality guards and protects them, though perhaps more than they would like, since the freedom of movement they enjoy is only apparent.

Foreigners grant credit to other’s amorous good fortune through confusing Armenian with Turkish women, whose same costume they wear, except for the yellow boots, and who imitate Turkish manners well enough to deceive someone not of their country; all that is then required is an aged go-between who arranges a rendezvous, in some isolated house, between a pretty schemer and the credulous young man; vanity does the rest, and the adventure always ends with the extortion of a more or less substantial sum of money, a detail customarily omitted by the foolish giaour, who imagines every woman to be one of the Pasha’s favourites, and dreams of following in the footsteps of the Grand-Seigneur. But, in reality, Turkish life is hermetically sealed, and it is difficult to know what goes on behind those densely-latticed windows, in which holes are pierced from the inside, to gaze out, as in theatre sets.

One must not think of obtaining information from the natives of the country. As Alfred de Musset says at the beginning of Namouna:

‘Un silence parfait règne dans cette histoire.’

‘Over this story, perfect silence reigns.’

(See de Musset’s ‘Namouna’: Canto I, verse 8, line 1)

To speak to a Turk of the women of his household is to commit the grossest impropriety; one should never make the slightest allusion, even indirectly, to this delicate subject. Thus, banal phrases are banished from conversation such as ‘How is madame?’ and others in a like style; the most fiercely bearded Osmanli would blush like a young girl on hearing such an enormity. The wife of the French ambassador, having wished to present some beautiful silks from Lyon to Mustafa Reshid Pasha, for his harem, gave them to him saying: ‘Here are some fabrics for which you, better than any, will know how to find a use.’ To express the intention behind the gift more clearly would have seemed an incongruity, even to Reshid, who was accustomed to French manners; it was the marquise’s exquisite tact that made her choose a vague and graceful phrase which could in no way offend Oriental sensitivity.

It is obvious, from this, that one would be ill-advised to ask a Turk for details regarding the private life of the harem, or the character and morals of Muslim women. Though he has been on familiar terms with you in Paris, and has drunk two hundred cups of coffee and smoked as many pipes on the same couch beside you, he will stammer, answer evasively, or be angered and avoid you thereafter; civilisation, in this respect, has made little progress here. One’s only means of seeking information is to ask some well-recommended European lady who has been admitted to a harem, to tell you, faithfully, what she has seen. A man, meanwhile, must renounce knowing more of Turkish beauty than the domino mask, or whatever he may have surprised beneath the cover of an arabas (cart), behind the window of a talikas (carriage), or in the shadows of the cypress trees in the cemetery, when heat and solitude cause the veil to be drawn back a little.

Again, if one approaches a woman too closely and there is a Turk close by, one attracts compliments like the following: ‘Christian dog! Infidel! Giaour! May the birds of the sky soil your head, may the plague fall upon your house! May your wife prove sterile!’ A Biblical, and Muslim, curse of the greatest gravity. However, his anger is rather feigned than real, and he is playing to the gallery, mostly. A woman, even a Turkish woman, is never angered by someone gazing at her, while hiding her beauty always weighs on her a little.

At the Fresh Waters of Asia, while leaning against a tree or beside the fountain like someone lost in vague reverie, I was able to view more than one charming profile barely blurred by a mist of gauze, and more than one throat pure and white as Parian marble rounding the folds of a partly-open feredje, while the eunuch strolled about a few steps away, or watched the steamboats pass by on the Bosphorus, reassured by my distant and melancholy air.

And then, the Turks see no more than we giaours; they never penetrate beyond the selamlik (reception room), to the inner rooms of their most intimate friends, and only know the women of their own household. When the ladies of one harem visit another, the slippers of foreigners, placed on the threshold, prohibit entry to the haremlik even to the master of the house, who thus finds himself barred from his own dwelling. The immense female population, anonymous and unknown to the male, circulates mysteriously in a city transformed into a perpetual Opéra ball, at which the dominoes are never allowed to unmask themselves. Fathers and brothers alone have the right to see the faces of their daughters and sisters uncovered; the veil is worn among less close relatives; thus, a Turk may see only five or six full faces of Muslim women in his lifetime. Large harems are the prerogative of viziers, pashas, beys, and other rich personages, since they are excessively expensive, each woman who becomes a mother requiring her own separate house and slaves; Turks of ordinary rank rarely wed more than one legitimate wife, though they are allowed to wed four, along with one or two bought concubines. Sexual superfluity remains for them a phantom and a chimera; it is true that they can compensate for this by gazing at the female Greeks, Jews, Armenians, and Perotes, and the rare female travellers who visit Constantinople.

If their positive enjoyment seems more certain than ours, they lack the pleasures of imagination. How can one be inflamed by a beauty barely glimpsed, a woman with whom any sustained relationship is impossible, and from whom the very fabric of life rigidly separates us? All this does not prevent, no doubt, some young Osmanli from falling in love with a khanum (lady) or an odalisque (concubine) following a fortuitous chance encounter, nor her returning his advances, despite all obstacles; but the exception proves the rule.

A Turk, in order to find a partner, employs the services of some mature woman, plying the trade of matchmaker, an honourable profession in Constantinople. The old woman, frequenting the public baths, describes to him, in minute detail, some Asma, Ruken, Nourmahal, Pembe-Haré, Leila, Mihri-Mahr, or some other nubile virgin beauty, taking care to adorn with still more Oriental metaphors the portrait of the young girl she favours. The effendi becomes enamored by the description, scatters bouquets of hyacinths on the street where the veiled idol of his heart will pass, and after a few glances have been exchanged, asks her father’s permission to wed her, assures him of a dowry proportionate to his passion and his fortune, and finally, for the first time, in the nuptial chamber, sees the importunate yashmak lowered, which previously robbed him of her otherwise pure and regular features. These proxy marriages give rise to no more misunderstandings and disappointments than our own.

I could repeat here, from the writings of travellers who have preceded me, a host of details on the valide (old lady; here, the go-between), the hasekis (consorts), sultanas, odalisques and the interior arrangement of the seraglio; the books from which I would draw these notions are available to all, and it is pointless to transcribe them. Let me pass on to something more precise, and give you a Turkish interior according to the account of a lady invited to dine with the wife of the ex-Pasha of Kurdistan of whom I have already spoken.

His wife had been a member of the Seraglio before marrying the Pasha. The Sultan freed some of his slaves, when they reached the age of thirty, who found it advantageous to marry given the connection they maintained with the palace, and the credit they were thus supposed to possess. Moreover they had received a sound education, and knew how to read, write, compose verse, dance, and play various instruments, and were distinguished by the fine manners seen only at court; they also possessed, to a high degree, an understanding of the complexities of intrigue and cabals, and often learned, from their friends still within the harem, political secrets of which their husbands might take advantage, either to obtain a favour or avoid disgrace. To marry a girl from the Seraglio was therefore a fine and calculated move on the part of an ambitious or prudent man.

The apartment in which the Pasha’s wife received her guest was as elegant as it was richly adorned, and contrasted with the severe bareness of the selamlik, which I described in the preceding chapter. A row of windows occupied the three external walls, so as to admit as much air and light as possible; a hothouse gives the most accurate idea of such rooms, in which rare flowers are also kept. A magnificent and soft Smyrna carpet covered the floor; arabesques and interlaced, painted and gilded patterns decorated the ceiling; a long divan of yellow and blue satin extended along two of the walls; another small very low divan had been placed in a gap between the windows, from which one could gain in full an admirable view of the Bosphorus; blue damask cushions were strewn here and there over the carpet.

In one corner, a large ewer of Bohemian glass, emerald-coloured, and patterned with designs in gold, sparkled on a tray of the same material; in another was placed a chest, covered with leather embossed, historiated, stitched and gilded in a charming style, and recalling, by the invention shown in its ornamentation, those chests from Morocco that Eugène Delacroix never fails to introduce into his paintings of North-African life. Unfortunately, this Oriental luxury was marred by a mahogany chest of drawers on the marble top of which stood a pyramidal clock complete with a glass globe, between two vases of artificial flowers also under glass, identical to those on the mantelpiece of any honest rentier in the Marais. These dissonances, afflicting the artistic sensibility, are found in all Turkish houses with pretensions to good taste. A room decorated more simply, adjoining the first, served as a dining room, and communicated with the staircase to the offices.

The khanum was sumptuously adorned, as Turkish ladies usually are at home, especially when expecting a visitor. Her black hair, divided into an infinity of small plaits, fell over her shoulders and across her cheeks. The crown of her head sparkled, as if topped with a diamond helm, with the quadruple links of a rivière (a strand or strands of graduated gemstones) and by stones of the finest water sewn to a small cap of sky-blue satin which they almost entirely covered. This splendid adornment suited her aspect of grave and noble beauty, her brilliant black eyes, her thin aquiline nose, her red mouth, her elongated face, the whole physiognomy of this great, haughty, but affable lady.

Her longish neck was circled by a necklace of large pearls, and her half-open silk chemise revealed a pretty and well-formed throat that required no aid from a corset, that embarrassing creation unknown to the Orient; she wore a dark garnet-coloured silk dress open at the front like a man’s surcoat, slit at the sides to knee height, and at the back forming a tail like a court-dress. This dress was edged with a white ribbon curled into star-shapes at intervals; a Persian shawl clasped the top of her wide white taffeta trousers, the folds of which covered small yellow morocco slippers revealing only their curved tips like Chinese clogs.

With a show of grace, she had the foreigner sit beside her on the small sofa, though only after having offered her a chair so she might be seated in the European manner if the Turkish seemed inconvenient to her, and examined her dress curiously, without marked affectation however, as a well-bred person does when a new object presents itself to her. The conversation, between people who do not speak the same language, and are reduced to mime, cannot be very varied: the Turkish woman asked the European if she had children, and gave her to understand that she herself was deprived of that happiness, to her great regret.

When the time to dine arrived, they crossed into the next room, also surrounded by sofas, and a polished copper side-table was brought in, laden with dishes much like those I have already described, except that the meat dishes were presented in smaller portions, and the sweets more numerous and varied. A favourite slave of the khanum took part in the meal beside her mistress.

She was a beautiful girl of seventeen or eighteen, robust, lively, in superb bloom, but far inferior in rank to the ex-odalisque of the seraglio; she had large black eyes beneath broad eyebrows, purplish lips, rounded cheeks, a somewhat rustic and healthy radiance facially, white and fleshy arms, a firm throat, and opulent contours that her loose costume allowed to be freely appreciated. She was wearing a small Greek bonnet from which her brown hair escaped in two large braids, and was dressed in a jacket, in that pistachio yellow that our dyers cannot capture, of a very light, soft tone. This jacket, slashed on the sides and at the rear so as to form a kind of tail like the surcoats of Parisian women, and possessing short sleeves from which others beneath in silk gauze escaped, accentuated, by emphasising her waist, a form which owed nothing to the lie of the crinoline; large baggy trousers in opaque muslin completed this outfit, as neat as it was graceful.

A mulatto woman, the colour of new bronze, with a piece of white drapery round her forehead, in a casually- rolled white abbaya (surcoat) which brought out the dark tone of her skin admirably, stood barefoot against the door, taking the dishes from the hands of a servant who brought them from the kitchen sited on the lower floor.

After dinner, the cadine (lady) rose, and crossed into the drawing-room, where she moved from sofa to sofa with graceful nonchalance. She then smoked a cigarette, instead of partaking of the traditional narghile; the cigarette now being fashionable in the East, with as many papelitos smoked in Constantinople as in Seville; idle Turkish women like to amuse themselves by rolling the straw-coloured threads of Latakia in thin tubes of papel de hilo (thread-paper).

The master of the house appeared, to visit his wife and meet the lady from Europe; and, on hearing him approach, the young slave fled with extreme haste, since, belonging to the khanum, and already affianced, she was not permitted to appear with her face uncovered before the ex-Pasha of Kurdistan, who, however, wished only the one wife, like many Turks.

After a few minutes the Pasha withdrew to pay his devotions in the next room, and the khanum recalled her slave.

The hour for leave-taking arrived; the stranger rose to depart; her hostess signalled her to stay a little longer and murmured a few words in the ear of the young slave, who began to search through the chest of drawers with great activity, until she found a small object in a case, which the Pasha’s wife gave to the visitor as a gracious souvenir of a pleasant evening spent together.

This cardboard case in lilac, glazed with silver, contained a small glass bottle on which the following legend could be read: ‘Extract of honey - for the handkerchief - Paris’ And on the back: ‘Double extract of guaranteed quality honey - L-T Piver, 103, Rue Saint-Martin, Paris.’ (Louis Toussaint Piver took over management of, and rebranded, in 1823, the perfume-house ‘À la Reine des Fleurs’ established in 1774 by Michael Adam. The manufactory at 111-113 Rue Saint-Martin, and the store at 103, which opened in 1833, were co-owned by his nephews from 1837. LT Piver is the oldest French perfume-house still currently in business.)

Chapter 17: Breaking the Fast

I have often uttered the word ‘caique’, and it would be difficult to do otherwise when speaking of Constantinople; but I perceive that I have given no description of the thing itself, which is worth doing, nonetheless; for the caique is assuredly the most graceful craft that has ever furrowed the blue waters of the sea. Compared to the Turkish caique, the Venetian gondola, however elegant, is only a crude coffer, and the barcarolas (boatmen, gondoliers) ignoble rogues compared to the caïdjis.

The caique is a boat fifteen to twenty feet long, and three feet or so wide, in the shape of an ice-skate, each end being terminated in such a manner as to allow it to move in either direction; the sides are made of two long planks carved inside with a frieze representing foliage, flowers, fruits, knotted ribbons, quivers in saltire, and other small ornaments; two or three upright planks, cut to form flying buttresses, divide the boat and support the sides against the pressure of the water; the prow is armed with an iron beak.

The entire vessel, made of waxed or varnished beech-wood, sometimes enhanced with a few lines of gilding, is extremely clean and elegant. The caïdjis, who each ply a pair of oars whose handles broaden to act as a counterweight, sit on a small transverse bench, covered with sheepskin to avoid them slipping when pulling on the oars, their feet resting against a wooden block.

The passengers crouch at the bottom of the boat, towards the stern, so as to raise the boat’s nose a little at the prow, and enable it to travel more freely: the boatmen even take the precaution of greasing the outside of the boat, so that it slides through the water. A more or less costly piece of carpet covers the rear part of the caique, in which it is necessary to remain utterly still, since the slightest movement might suddenly capsize the boat, or strike the wrists of the caïdjis, at least, who row two-handedly. The caique is as sensitive as a pair of scales, and tilts to right or left at the slightest loss of equilibrium; the Turks sense of balance, they as rooted as statues, accommodates itself marvellously to the constraint imposed, a constraint which is painful initially for a restless giaour, but to which one soon grows accustomed.

There is space for four passengers in a two-oared caique, seated in pairs facing each other. Despite the sun’s heat, these boats are free of awnings, which would slow their progress, and are contrary to Turkish etiquette, awnings being reserved to the Sultan’s caiques; but they carry a parasol, which is closed when passing near to the imperial residences. Such a boat can match the speed of a horse moving at full trot along the shore, and sometimes even overtake it.

Each caique bears a stamp near the prow indicating the landing-stage where it is stationed: Tophane, Galata, Yeşil-Köşk, Yeni-Cami, Beşiktaş, etc.

The caïdjis are superb fellows, Albanians or Armatoles (irregular recruits to the Ottoman army) for the most part, possessed of masculine beauty and herculean vigour. The sun and air, which have browned their skin, render them the colour of beautiful bronze statues of which they already own the forms. Their costume consists of large linen trousers of dazzling whiteness, and a striped gauze shirt with slit sleeves, which allows them to move freely; a red fez, whose tuft in blue or black hangs down six inches or so, topping a head with shaved temples; and a belt of yellow and red striped wool wound round several times above the loins and securing the waist.

They shave their chins, only retaining a moustache, so as to avoid the warmth generated by unnecessary hair; their feet and legs are bare, and their open shirts reveal powerful pectorals bronzed by a solid tan. With each stroke of the oar, their biceps of their athletic arms swell like cannonballs. The obligatory ablutions keep their fine bodies scrupulously clean, purified by exercise, the fresh air, and a sobriety unknown to the people of the North. The caïdjis, despite their hard work, eat little more than bread, cucumbers, corn-cobs, and fruit, and drink only fresh water or coffee, while, during the thirty days of fasting required by Ramadan, the Muslims among them row from morning to night without swallowing a mouthful of water or smoking a pipe.

It would be no exaggeration to suggest that three or four thousand caïdjis must serve the different landing-stages of Constantinople and the Bosphorus, as far as Therapia (Tarabya) or Büyükdere. The layout of the city, separated from its suburbs by the Golden Horn, the Bosphorus and the Sea of Marmara, necessitates perpetual aquatic journeys; one needs to take a caique to travel from Tophane to Seraï-Bournou, from Beschick-Tash (Besiktas) to Scutari (Usküdar), from Psammathia (Samatya) to Kadi-Keuï (Kadikoy), from Kassim-Pacha (Kasimpasa) to Phanar (Fener), and from one side of the Golden Horn to the other, whenever one finds oneself too far from one of the three boat-bridges which link Europe and Asia-Minor.

Nothing is more amusing, when you arrive at one of the landing stages, than to see the caïdjis hastening to fight over your person, as the drivers of coucous (Parisian two-wheeled box carts) used to tear travellers apart, insulting each other with deafening volubility, and each offering you their boat at a discount. The tumult is sometimes mingled with the barking of terrified dogs, trampled on in the midst of the heated debate. Finally, bumped, elbowed, pulled and pushed, you become the prey of one or two gigantic fellows who drag you triumphantly towards their boat through groups of their disgruntled and disappointed colleagues.

To descend into a caique, without overturning it keel in the air, is a rather delicate operation. Usually, a fine old Turk, with a white beard, his complexion browned by the sun, holds the boat with a stick armed with a nail, a para (a small copper coin, there were forty ‘paras’ to the silver ‘kuru’, introduced in 1844, with a hundred kurus to the gold Ottoman ‘lira’) being thrown to him for his trouble.

It is not always an easy thing to extricate the craft from the flotilla gathered around each landing stage, and it requires the caïdjis’ incomparable skill to succeed without boarding and without accident. To disembark its passengers, each caique turns around, stern to shore, an evolution which might lead to dangerous collisions if the caïdjis had not their agreed calls, like those of the gondoliers of Venice, to warn one another. When one disembarks, one leaves the fare at the bottom of the boat, on the carpet, in piastres (kurus) or beshliks (five-para coins), according to the length of the journey and the sum agreed.

It would be a fine thing to be a caïdji in Constantinople, if it was not for competition from the steamboats which are beginning to circulate on the Bosphorus in as great a number as watermen’s wherries on the Thames. From the Galata Bridge, beyond which they cannot ascend the estuary, a crowd of Turkish, English, and Austrian steamboats depart, at all hours of the day, their smoke mingling with the silvery mists of the Golden Horn, vessels which deposit travellers by the hundreds at Bebek, Arnaout-Keuï (Arnavutköy), Anadoli-Hissar (Anadoluhisari), Therapia (Tarabya), and Buyuk-Déré (Büyükdere), on the European shore; or at Scutari (Usküdar), Kadi-Keuï (Kadikoy), and the Princes’ Islands, on the Asian side. Such crossings had to made by caique previously, cost a deal of time and money given the length of the journey, and presented some danger because of the violence of the currents and the wind, which is liable to freshen, from one moment to the next, at the outlet from the Black Sea.

The caïdjis seek, in vain, to compete with the steamboats for speed. They flex their muscles; vying, uselessly, with the steel pistons of the steamboats. Soon only brief intermediate journeys will be left to them, and old backward-looking Turks who weep, at the Elbicei-Atika (Museum of Costume), on viewing the Janissaries’ preserved clothing, will be alone in using them, out of hatred for the diabolical inventions of the giaours, when visiting their summer houses. There are also omnibus-caiques, heavy boats carrying up to thirty passengers or so, manoeuvred by four or six rowers who, at each stroke of the oars, step up onto a wooden board, then lean backwards and employ all their weight to shift their enormous oar. These automatic movements, repeated minute by minute, provide the strangest of sights to the eye; the soldiers, the hammals, the poor, the Jews, and the old women, use this economical but slow means of transport, which will be superseded by the steamboats whenever their owners wish, simply by creating a ‘third class’ at reduced prices.

I was therefore not at all surprised to hear news of a riot instigated by the caïdjis; it was easy to foresee, given, the numerous funnels of the pyroscaphes, near Galata, smoking, and the waters whitening beneath the blades of the paddle-wheels, waters which till then had only been struck by those crescent-shaped oars. During my stay, the boatmen, crouching melancholically on their deserted jetties, already watched, with gloomy eyes, steamboats crowded with passengers ascending the current like shoals of sea-bream.

The hour, patiently awaited, which ended the fast, had arrived, an event solemnised by public celebration. The Bosphorus, the Golden Horn and the basin of the Sea of Marmara presented a most lively and happy aspect: all the ships in the harbour were decked with multi-coloured banners; the flags, once hoisted, fluttered in the wind; the Turkish standard, ending in a swallowtail, showed three silver crescents on a sinople (green) shield within a field gules (red). France unfurled its tricolour; Austria displayed its banner striped with red and white and charged with a crowned escutcheon; Russia had its azure cross in saltire on a silver background; England, its cross of Saint George; the United States, the striped ensign adorned with stars (the thirteen-starred ‘boat-flag’); Greece, its blue cross, on a white background, bearing at its centre the white and black diamond-chequering of Bavaria; Morocco displayed its red pennant; Tripoli its three half-moons on a field of the Prophet’s favourite colour (green); Tunis its flag with two blue stripes, two red, and a single central green stripe like a silken belt, while the sun gaily played on, and flickered across, all these banners whose reflections extended and meandered over the limpid water; artillery salvoes greeted the Sultan’s caique, which passed, resplendent with gilding and purple, driven forward by the efforts of thirty vigorous oarsmen, while sailors, standing on the yards, shouted hurrahs, and albatrosses, scared by the noise, swirled amidst the cottony clouds of smoke.

I took a caique at Tophane, and was borne in it from one vessel to another, so I might examine the cross-sections of the various ships, my preference being for us to linger beside the boats coming from Trebizond (Trabzon), Moudania (Mudanya), Ismick (Izmit), and Lampsaki (Lapseki, ancient Lampsacus), whose castle-like sterns, swan-breasted prows, and masts with long spars, differ little, one supposes, from the vessels of which the Greek fleet was composed at the time of the Trojan War. The much-vaunted American clippers are far from possessing the former’s elegant curves, and it takes scant imagination to picture the blond-haired Achilles, son of Peleus, seated on one of those high sterns bathed by the sea, where the Simois (the Dümrek Cayi) discharged its waters.

As we sped along, the boat skimmed the islet of rocks on which stands what the Franks call, for some reason or other, the Tower of Leander, and the Turks, Kiz-Kulesi, the Tower of the Maiden. Needless to say, Leander’s name is attached to this white turret most improperly, since it was the Hellespont and not the Bosphorus that he swam to visit Hero, the beautiful priestess of Aphrodite. The following graceful legend explains the Turkish name.

The Sultan Mahmud I had a daughter of rare beauty, whom a gypsy claimed would die from the bite of a snake. Her alarmed father, to thwart the sinister prediction, built a kiosk for her on this islet, a reef to which not even a lizard clung; the son of the Shah of Persia having heard of the wondrous beauty of Mehar-Schegid (such was the name of the young girl) fell passionately in love with her, and arranged for one of those bouquets by means of which the Orient write its confessions of love in flowery symbols to reach her. Sadly, an asp lurked amidst the mass of hyacinths and roses, and bit the princess on the finger. She was on the verge of death, for lack of one devoted enough to suck the venom from her wound, when the young prince, the cause of all this evil, came to her side, and passionately and courageously took the poison in his own mouth, thus saving Mehar-Schegid, whom Mahmud then granted him as his wife.

In fact, the tower, or its predecessor at least, was built during the Late Empire (in the twelfth century AD) by Manuel I Comnenus, served to support a chain attached to a corresponding tower on the European shore and, with a defensive wall to the Asian shore, barred the entrance to the Golden Horn to enemy vessels out of the Black Sea. Even earlier in time, it is said that Damalis, wife of Chares, the general sent from Athens (in 340 BC) to the aid of Byzantium which had been attacked by Philip of Macedon’s fleet, died at Chrysopolis, and that she was buried on this islet, in a tomb surmounted by the statue of a heifer (the meaning of the name Damalis).

A Greek epitaph, which has been preserved, was inscribed on the tomb’s pillar, and from this comes, no doubt, the true origin of the name Kiz-Kulesi, the tower or tomb of the maiden. The epitaph reads: ‘I am not the image of that heifer, the daughter (Io) of Inachus, who gave a name to the Bosphorus (βοὸς πόρος, the cow-strait) stretching before me. Juno’s cruel resentment once drove her beyond the seas; I who occupy this tomb, am the daughter of Cecrops. I wed Chares, and sailed with that hero when he came to fight Philip’s fleet. Till then I was called Boiidion, the Little Heifer, now, wife of Chares, I enjoy two continents.’

Thus is explained the sculpture of a heifer on Damalis’ funeral column. We know that, among the Greeks, the cow evoked more than one flattering comparison, and that Homer gives Juno the eyes of a heifer. Boiidion is therefore a graceful epithet according to ancient ideas, and one that we should not be surprised to see applied to a beautiful young woman. But enough of Greek, let us return to Turkish.

On breaking the fast, it is customary that, his valide (mother) gifts the Sultan a virgin girl of the most perfect beauty; to find this phoenix, the slave traders or jellabs search Georgia and Circassia for several months in advance, and she may well command an enormous price. If the girl conceives on the night which is considered blessed it is treated as a favourable omen for the empire’s prosperity. Strangely, in contrast, during the seven days following the breaking of the fast, true believers abstain from any carnal contact with their wives, for fear of producing deformed, monstrous children, or children disfigured by birthmarks, thus His Highness, at that time, is the only Muslim in the empire to whom, to his good fortune, the pleasures of love are permitted!

The day is devoted to prayers and to visiting the mosques, and in the evening the city is illuminated. If the sight of the port, with all its flag-bedecked vessels and the perpetual movement of vessels, was already a marvellous spectacle beneath the splendid Eastern sky, what can be said of this nocturnal festival? It is then that one feels the impotence of the pen and the brush; a diorama alone could, with the help of its varied lighting, give a faint idea of those magical chiaroscuro effects.

Artillery discharges, following one another without respite, for the Turks are very fond of burning powder, burst forth on all sides, deafening the ears with their celebratory din; the minarets of the mosques were lit up like beacons; verses from the Koran were inscribed in fiery letters on the dark blue of the night, and a motley and compact crowd descended, in a human cascade, the sloping streets of Galata and Pera; around the fountain of Tophane, thousands of lights sparkled like glow-worms, and the mosque of Sultan Mahmud soared into the sky, outlined in points of fire, like those palaces pricked out on black paper and revealed by the lamp behind them, of François Dominique Séraphin’s shadow-play sets.

A caique took me out to sea, one of my friends in Constantinople having kindly arranged a place for me aboard a Lloyd’s registered ship. Tophane, lit by red and green Bengal lights, blazed amidst the clouds of an apotheosis, torn apart, moment to moment, by cannon-fire, the crackling of fireworks, the zigzags of serpentines, and the explosions and flowering of fiery bombs. The Mahmudiyah (Mahmut Pasha) Mosque appeared, amidst opal-coloured smoke, like one of those carbuncular edifices created by imaginative Arab storytellers to house the queen of the peris; it was dazzling.

The ships at anchor, their masts, yards and planking outlined by rows of green, blue, red and yellow lamps, looked like jewelled ships floating on an ocean of flame, so brightly were the waters of the Bosphorus lit by the reflection of this blaze of lanterns, fire-pots, starry suns, and illuminated forms.

Seraï-Bournou extended like a promontory carved of topaz, above which, encircled by coronets of fire, sprang the silver minarets of Hagia Sophia, the Sultan-Ahmet Mosque, and the Nuruosmaniye Mosque; on the shore of Asia-Minor, Scutari (Üsküdar) emitted myriads of luminous sparks, as both fiery shores of the Bosphorus as far as the eye could see framed a glittering spangled surface incessantly whipped to foam by the oars of the caiques.

Inner Court of the Mosque of Sultan Osman

Sometimes a distant ship, previously unnoticed, would burst into flame, wear a sudden purple and bluish halo, then vanish again in the shadows like a dream. These pyrotechnic surprises produced the most charming effect.

Steamboats, bright with panes of coloured glass, passed by, carrying orchestras whose fanfares were scattered joyfully in the breeze.

Above all this, the sky, as if it wished to join the celebrations, spread its lavish casket of stars over a field of lapis lazuli of the darkest and richest blue, the border of which the fiery earth below barely reddened.

I remained an hour or two aboard the Austrian vessel, intoxicated by that sublime spectacle, unrivalled anywhere in the world, attempting to engrave in my memory forever those glittering enchantments rendered double by the magic mirror of the Bosphorus. What are our poor festivities on the Place de la Concorde, where a few dozen lanterns smoke, next to that firework-display of diamonds, emeralds, sapphires, and rubies bursting and crackling over an area nine or ten miles in length, which, instead of being quenched in the water, is seemingly rekindled more phosphorescently and more vividly?

What a host of lamp-posts and yew-trees, of three-masted ships illuminated from deck to weather vane, of lances of flame, and minarets a hundred feet high, was alight in that immense amphitheatre that Nature seems to have created to surround her capital of the world, and in which the philosopher Charles Fourier placed, in anticipation, the throne of the global Omniarch!

Here and there the lights began to fade, breaches appeared in the lines of fire, the powder, almost exhausted, proved difficult to detonate; enormous banks of smoke, which the breeze could no longer disperse, crawled over the surface like monstrous sea-creatures; the cold dew of the night soaked even the thickest clothes; it was necessary to think of departing, an operation not without difficulty and peril. My caique awaited me at the foot of the ship’s ladder; I hailed the caïdjis, and we made way.

The Bosphorus was covered by the most prodigious swarm of vessels of all kinds that one could imagine and, despite warning cries, oars were constantly entangled, boats brushed against one another, and the oarsmen were obliged to fold those same oars, like the legs of insects, against the sides of the boats, or risk them being shattered.

The points of prows passed within two inches of one’s face, like javelins or the beaks of birds of prey; the reverberations from all these explosive fireworks, scattering in last glimmers, blinded the caïdjis and deceived them as to their true direction; a boat driven at full speed nearly passed over ours, and I would certainly have been cut in two, or drowned in the depths, if the boatmen had not, with incomparable skill, hauled us backwards with a superhuman show of strength.

At last, I arrived, safe and sound, at Tophane, amidst the lapping and shimmer of the waves, a tumult of boats, and cries enough to drive one mad, and returned to the Hotel de France, via the little Champ-des-Morts, through streets that were gradually more and more deserted, stepping carefully over the encampments of sleeping dogs.

Meanwhile, the happy Caliph, in the depths of the Seraglio, was lifting the veil of the beautiful slave gifted to him by the Sultana his mother, his gaze dwelling slowly upon those hidden charms that no human eye but his beheld.

Chapter 18: The Walls of Constantinople

I decided to perform a grand tour of the remoter districts of Constantinople, which travellers rarely visit. Their curiosity hardly extends beyond the Bedesten, the Atmeidan (Atmeydani, Sultanahmet Square), Bayezit Square, the Old Seraglio, and the surroundings of Hagia Sophia, on which all the activity of the Muslim city is concentrated. I therefore set out early, in the company of a young Frenchman who has lived in Turkey for some time; we quickly descended the slope of Galata, crossed the Golden Horn on the boat-bridge, threw four paras at the toll-keeper and, turning from Yeni-Cami, plunged into a maze of Turkish alley-ways.

As we advanced, the solitude increased; the dogs, wilder, gazed at us with haggard eye, and followed us, growling. The faded and tottering wooden houses, with plain latticework, their storeys out of true, had the appearance of collapsing chicken coops. The water of a ruined fountain, extravasated, filtered into a greening conch-shaped basin; a dismantled turbe (tomb), invaded by brambles, nettles, and asphodels, revealed, through grilles obstructed by cobwebs, a few funeral cippi, leaning left and right in the shadows, and offering only illegible inscriptions; a marabout (a religious leader’s mausoleum) with a round dome roughly plastered with lime, was flanked by a minaret like a candlestick topped by its snuffer; above the long walls, black cypress tips sprang, while branches of sycamores and plane-trees bent down towards the street. No more mosques with marble columns, and Moorish arcades, no more Pasha’s konaks (mansions) painted in bright colours with their gracefully projecting aerial rooms, but, here and there, were piled large heaps of ashes from the centre of which rose a few blackened brick chimneys, still standing tall, while over this scene of wretchedness and abandonment, gleamed the pure, white, implacable light of the Orient, which cruelly exposes every melancholy detail.

From alley to alley, via crossroad after crossroad, we arrived at a large, dreary and dilapidated khan (caravanserai), with tall arches and long stone walls, intended to house strings of camels: it was the hour of prayer, and, on the outer gallery of the minaret of the neighbouring mosque, two muezzins dressed in white walked, at a ghostlike pace, uttering, in voices full of strange tones, the sacramental formula of Islam towards those mute, blind and deaf houses, crumbling silently in solitude. This verse of the Koran, which seemed to descend from the sky, modulated by a sweetly guttural voice, awakened no other noise than the plaintive sigh of some dog troubled by dreams, or the beating of some frightened dove’s wings. The muezzins nevertheless continued their impassive ritual, scattering the names of Allah and the Prophet to the four winds of the horizon, like sowers careless of where the seed falls, knowing full well that it will find the furrow. Even beneath those worm-eaten roofs, perhaps, in the depths of apparently abandoned shanties, the faithful spread their poor little worn carpets, turned towards Mecca, and repeated with deep faith: ‘Ash-hadu alla ilaha illa-llah! Ash-hadu anna Muhammadar Rasulullah!’

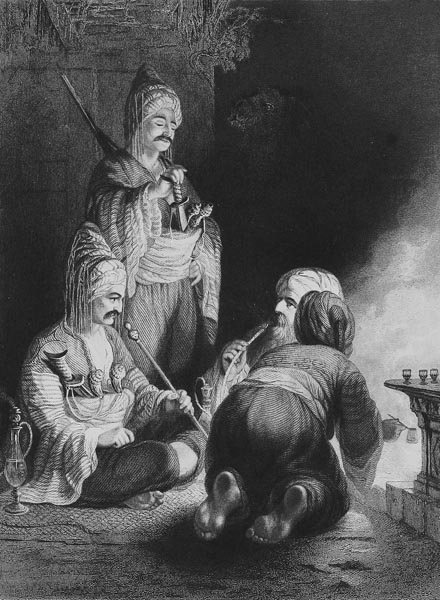

Halt of Caravaniers at a Serai

A black North-African on horseback passed by from time to time; an old mummy pressed against a wall extended a monkey’s paw from a pile of rags, begging for alms, taking advantage of this unexpected opportunity; two or three urchins who had escaped from an Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps watercolour were trying to thrust pebbles into the neck of a dried-up fountain. A few lizards ran over the stones, in complete safety, and that was all.

I felt overwhelmed with sadness, despite myself, and would have forgotten the object of our walk, which was to go and see the acrobats near the Silivri-Kapi gate, if my companion had not reminded me of it several times. I was weary and famished, for we had travelled, without being aware of it, an enormous distance, and had strayed considerably from our route, which we had regained, but not without difficulty; we crossed the courtyard and the garden of a mosque whose name I forget, while the sound of shrill, barbarous music emerging from a wooden enclosure indicated to us that we were on the right path. This indeed was the place. We seated ourselves on those stools four-inches in height, coffee and pipes were brought, and we watched the performance taking place in the centre of the courtyard, in a layer of fine dust: they were Moroccans carrying out the same tricks anyone can see executed at the Cirque des Champs-Élysées by the Arab troupe there.

I even thought I recognised the massive fellow who served as the base of the human pyramid, and who carried eight men, in tiers, on his tanned shoulders and on his bluish skull. Frames with taut ropes strung between them indicated that the show came complete with tightrope dancing; but we had arrived too late to see that part of the program; a mishap that I greatly regretted, since we were told the acrobats were little girls of nine or ten years old, very pretty, and of a rare lightness of foot; there were also buffoonish tightrope-walkers, Turks with large beards and large parrot noses, who gravely assumed all sorts of grotesque and comically bizarre poses. At the rear of the courtyard a latticed gallery, a seraglio as they say in Turkey, served as a platform or box for the women, and we were made to withdraw so that they could pass forth freely, the presence of giaours troubling their sense of modesty; an exaggerated sense, certainly, since we saw them from afar, wrapped to the eyebrows, and resembling those pieces of wicker basketwork round which linen is draped in the washhouse.

We looked around for something to eat, for, though we had sated our eyes, our stomachs had received no nourishment, and every minute increased our anguish. There were, in this half-deserted district, none of those appetising rotisseries where kebabs, sprinkled with pepper, turn in the flames on a perpendicular spit; none of those shop-window slabs on which large portions of baklava are spread, covered by the pastry chef’s hand with a light snow of sugar; none of those triumphant eateries offering rice-balls wrapped in vine leaves, and bowls of cucumber wedges swimming in oil, with lumps of added meat. There was nothing to buy except white mulberries and black soap: a mediocre offering!

We wandered about, half-starved, rolling our eyes eagerly here and there, choosing those streets a little less deserted than the others, which seemed to promise some chance of finding food. A kindly old Greek lady, followed by a little servant carrying a large package, took pity on us and pointed out, not far from there, an inn where we would probably find something to eat. Her information was correct, but the inn had been closed for several years. The good matron’s memory of it was that of her youth.

The district we were traversing presented a completely different physiognomy; it was no longer Turkish in appearance. The half-open doors of the houses allowed one’s gaze to penetrate into the interior. At windows lacking grilles, appeared charming women’s heads, coiffed with pink or blue crepe, and crowned with a large braid of hair forming a diadem; young girls sitting on the threshold glanced freely at the street, and we were able to, admire without scaring them away, their fine, pure features, large blue eyes, and blonde braids; in front of the cafés men in white fustanellas, red skullcaps, and jackets with long braided sleeves, swallowed large glasses of raki (doubly-distilled grape pomace flavoured with aniseed) and drank till inebriated like good Christians. We were in Psammathia (Samatya), a district inhabited by the rayas, the non-Muslim subjects of the Ottoman Porte, a sort of Greek colony in the midst of the Turkish city. Animation had replaced silence; joy had replaced sadness; one felt oneself in the midst of a living people once more.

A young rascal, seeing us searching for a tavern, came to offer himself as a guide, after showing us his passport like the true rogue that he was, and led us, with many a detour to grant importance to the service he was rendering, to a kind of locanda (inn) situated ten paces from the place where he had found us. We gave him a few paras for his trouble; but doubtless not finding himself sufficiently rewarded, he stole, with the expertise of a skilled and mean-spirited thief, my comrade’s purse, containing about thirty francs in beshliks and piastres.

We entered a large room where, behind a counter laden with food and bottles, stood a truculent Palforio (the innkeeper in Alfred de Musset’s play ‘Les Marrons du Feu’), apparently more suited to cutting the necks of travellers than of chickens. This dread cook, with an olive face, a blue beard forming green tones against the yellow tones of his skin, and the eyes and beak of a bearded vulture, nevertheless condescended to serve us shrimps, fried red mullet in frilled paper wraps as one serves lamb cutlets, peaches, grapes, cheese, and a flask of white wine resinato (resinated), resembling Turin vermouth in taste, its bitter flavour not too unpleasant once one is used to it. He was unable, despite our wishes, to produce any meat, since they were celebrating some Greek festival or other that day, which made abstinence from meat obligatory. But we were so hungry, that the simple collation he did provide seem to us a dish from Belshazzar’s feast, and we fully expected to see a fiery script appear on the wall. However, Psammathia failed to collapse on its foundations, and we were able to finish our meal without Biblical catastrophe.

Duly comforted, we set out with fresh vigour, and soon reached the nearest gate of the ‘Fortress of the Seven Towers’, in Greek ‘Heptapyrgion’, or in Turkish ‘Yedikule Hisari’, names with an identical meaning. There we met one of those renters of horses, so numerous at Tophane, near the Harbour of the Dead (L’Échelle des Morts), at the Green Kiosk (Yeşil-Köşk), at the Large Field of the Dead of Pera, and in all the much-frequented places of Constantinople, but a phenomenal rarity here. We mounted his two beasts, which were harnessed in a proper manner, and certainly equal to the so-called English nags our victors ride on the Champs-Élysées. These gentle Kurdish horses, one white, the other a bay, set off, fraternally, at a brisk pace, followed by their owner on foot, and we headed to the right, leaving the scarred towers of the fortress, the ancient state prison, behind, on our left. We wished to skirt the exterior of Byzantium’s ancient walls, along the shore, and then inland as far as Edirne-Kapissi (Edirnakapi) or even further if we were not too wearied.

Nowhere in the world, I believe, is there a walk more austere or gloomier than this path which runs for nearly three miles between a cemetery and the ruins.

The ramparts, composed of two lines of wall flanked by square towers, overlook, at their feet, a wide moat now sown with crops, and covered by a stone parapet, which made three enclosures to cross. These are the Emperor Constantine’s ancient walls, such as time, and various sieges and earthquakes, have rendered them; in their courses of brick and stone, one can still see the breaches made by the catapults, the ballistae, the battering rams and the gigantic culverin, the mastodon of artillery, which was served by seven hundred gunners, and which launched marble cannonballs weighing six hundred pounds. Here and there an immense crack splits a tower from top to bottom; further on, a whole section of wall has fallen into the depths of the moat; and where the stone has been lost, the wind accumulates dust and seeds; a shrub grows in place of the missing crenellations, and becomes a tree; a thousand claws of parasitic plants restrain the crumbling brick; the roots of strawberry-trees, at first pincers gripping the joints of the stones, become crampons to hold them, and the wall continues without interruption, its eroded silhouette highlighted against the sky, its spreading curtains draped with ivy, and gilded by time in rich yet severe tones. From near to far rise the old gates in the Byzantine style, plastered with Turkish masonry but nevertheless still recognisable.

It is hard to imagine a living city behind these dead ramparts, which nonetheless hide Constantinople. One might well think oneself on the outskirts of one of those cities in the Arabian tales whose entire population has been petrified by some curse; a few minarets alone raise their heads above the immense line of ruins, proclaiming Islam’s capital. The conqueror of Constantine XI, if he returned to the world, could utter still, and most aptly, his melancholy Persian quotation: ‘Now the spider is chamberlain in Caesar’s palace, and the owl hoots the watch on the towers of Afrasiab.’ (Sultan Mehmed II, took Constantinople in 1453 AD, quoting those words, as legend has it, on his entry to the city. Afrasiab was a mythical king of Turan, and the main protagonist of Ferdowsi’s ‘Shahnameh’).

These reddish walls, cluttered with the vegetation that clothes such ruins, walls which are crumbling slowly and in solitude, and over which a few lizards scamper, witnessed the hordes of Asia, led by the fearsome Mehmed II, gathered at their feet. The bodies of the Janissaries (elite infantry) and Timariots (cavalrymen) fell, riddled with wounds, into the ditch where peaceful vegetables now flourish; cascades of blood streamed down where the filaments of saxifrages and wall-plants now hang. One of the most dreadful of human contests, a struggle of one people against another, of religion against religion, took place in this solitude where a deathly silence now reigns. As always, youthful barbarism prevailed over a decrepit civilisation, and, while some Greek priest fried his fish, unable to conceive of the capture of Constantinople, Mehmed II, rode his horse, in triumph, into Hagia Sophia, and set his blood-stained handprint on the wall of the sanctuary, as the crosses were toppled from the summit of the domes to make way for the crescent, and the body of Emperor Constantine was retrieved from beneath a heap of dead, bloody and mutilated, and recognisable only by the golden eagles which clasped his purple knee-high boots.

I spoke of the caloyer (Greek Orthodox monk) busy frying fish during the final assault on Constantinople, who is said to have responded incredulously to the announcement of the Turkish triumph: ‘Bah! I’d rather believe that these fish will be resurrected, emerge from the boiling oil, and swim across the floor.’ A miracle which, it seems, actually took place, and must surely have convinced the obstinate monk.

The descendants of those miraculous fish wriggle in the cistern of the ruined Greek church of Balikli, which can be seen some distance from the city walls, a little before arriving at Silivri-Kapi. They are red on one side and brown on the other, in memory of the frying that their half-cooked ancestors endured; a poor devil of a priest still shows them to strangers, saying: Idos psari, effendi. (‘Look at the fish, sir.’) Though I profess to no Voltairean opinion regarding miracles, I thought it inappropriate to seek to verify this one for myself, especially since it was a schismatic miracle in which I was not obliged to believe; I therefore contented myself with the legend and continued on my way.

What a pity that my friend, the fine landscape painter, Jean-Joseph Bellel, has not travelled to Constantinople! What advantage he could take of these superb ruins, these great cypress trees, these sections of tottering wall supported by vigorous vegetation! How his firm and masterly charcoal would delineate the leaves of the plane-trees, strawberry-trees, and mastic-trees that have conquered this moat filled with human detritus!

Winter rains, summer winds, and the work of time have carried away the earth at the sides of the road, which has probably not been repaired since Constantine, and have eroded the path which in places seems rather the crest of a large half-buried rampart than a passable way; two arabas were nevertheless navigating this improbable route, one gilded and painted, jolting along, with five or six well-dressed and carefully-veiled women, within, holding beautiful children on their knees; the other fashioned simply of planks held together by wooden pegs, shaking a clan of male and female Gypsies about, who were brown as Indians, gaunt and ragged, and were squawking out a strident Bohemian song, behind which buzzed the dull murmur of Basque drums.

I am still trying to understand how those heavy carriages twenty-times avoided being overturned and shattered at the bottom of those three-or-four feet deep ruts; but the oxen are sure-footed, and their drivers hang onto the beasts’ horns. As for me, I quit that tumultuous stone quarry, and walked my horse beneath the cypresses of the immense Champ-des-Morts which faces the ramparts from the Seven Towers to the foothills of Eyüp.

I was walking slowly along a narrow path distinguishable between the tombs, when I saw, lingering beside a funeral cippus, a young woman, masked by a somewhat transparent yashmak, and draped in a soft green feredje; in her hand she held a bunch of roses, and her large eyes, brightened with antimony, floated, lost in indefinable reverie. Was she bringing the flowers to lay on some beloved tomb, or was she simply taking a walk in the gloomy shade? I cannot say; but, at the sound of my horse’s hooves, she raised her head, and, behind the clear muslin, I could discern a charming face. Doubtless, my eyes expressed my naive and honest admiration, since she approached the edge of the road, and, with a movement full of timid grace, held towards me a rose taken from her bouquet.

My comrade, who was following, joined me, and she offered him one also, with a shade of delicate modesty which corrected what might have appeared too free a first impulse. I greeted her as best I could in the Oriental manner. Two or three companions joined her, and she disappeared among the dense cypress trees. So ended my only Turkish ‘affair’; but I have not forgotten those large black eyes, the eyelids tinted with kohl (surmeh), and the rose, a precious relic, yellowing in Paris in a white satin sachet.

Chapter 19: Balata (Balat) – Phanar (Fener) – The Turkish Baths

If I were on an antiquarian’s journey instead of an artist’s tour, I could, with the help of a great many books, have discoursed at length on the probable locations of the ancient edifices of Byzantium, reconstructed them from a few doubtful fragments lost under aggregations of Turkish buildings, and reported a certain number of Greek inscriptions relevant to the subject, which would grant me the air of a very learned man; but I prefer a sketch made from nature, a true impression, sincerely rendered. So, I will not detail each ancient door, or seek the precise place where the unfortunate Constantine XI Dragases Palaiologos fell, a place marked, it is said, by a gigantic tree, growing from the rampart. The portals open beneath tall and massive towers, decorated with a few columns of a composite order indicating Byzantine decadence, whose shafts are often borrowed from some ancient temple, while an arch filled with solid masonry designates the Golden Gate, since, according to an old tradition, any future conqueror of Constantinople must enter the city by that portal, which saw Alexis Strategopoulos, lieutenant to Michael VIII Palaiologus, pass through triumphantly (in 1261AD) when he reconquered Byzantium, in a night, from the forces of Baldwin II, and thus put an end to the Latin empire in the East. Is this wall about to fall, as the Greeks anticipate, to allow entry to their Russian co-religionists after the four-hundred years interval, fixed by prophecy as extending from the capture of Constantinople, which date fell precisely on the twenty-ninth of May? And will Mass be celebrated at Santa Sophia in the presence of the Tsar? That is a matter I will not enter into; but the presence of Prince Alexander Menshikov, should one credit Russia with hostile intentions, could not chime more exactly with popular prejudice and belief.

Near the Adrianople Gate (Edirnekapi), we dismounted to drink a cup of coffee and smoke a chibouk in a café populated by a motley clientele, then continued our route, always flanked by the never-ending cemetery; though we found the end of the wall at last, and were able to re-enter the city, guiding our faltering mounts with caution as they stumbled amidst the marble turbans, and the tombs whose slippery slopes bristled with fragments.

We thus arrived in a strange district with a very particular physiognomy: the hovels were more and more dilapidated, low and soiled. Their facades, shabby, bleared and scarred, were cracking, warping, disintegrating, ready to turn to rot. The roofs appeared to suffer from ringworm, and the walls from leprosy; bits of their greyish coating had flaked away, like dandruff from a scaly skin. A few blood-stained dogs, reduced to skeletons, eaten away by vermin and insect-bites, lay asleep in the black and fetid mud; vile rags hung from the windows, behind which we could see, since we were high on our mounts, strange heads, of a sickly livid hue between that of wax and lemons, surmounted by enormous rolls of white linen, attached to small, slender bodies with flat chests, on which a shimmering fabric, like that of a damp umbrella gleamed. Dull, lifeless eyes, with vanquished gazes, like embers set in the omelettes of these yellow faces, rose to view us, and fell back again to some task or other; while furtive ghosts passed amongst the huts, their foreheads girded with a white rag speckled with black as if wear and tear had wiped its pen there day after day, their bodies lost in smocks varnished with filth.

We were in Balata, the Jewish quarter, the ghetto of Constantinople. Here dwell the remnants of four centuries of oppression and humiliation, a midden in which these people, proscribed everywhere, huddle as certain insects do to escape their persecutors; they are protected by the disgust they inspire, living amidst filth, and acquiring its hue. It would be difficult to imagine anything more soiled, infected or purulent: plague, scrofula, scabies, leprosy, all the biblical impurities, of which they have not been cured since Moses, devour them without their opposition. Their need to earn a living of sorts, prevents their recoiling even from those dead of the plague, if they can gain something from the corpses’ clothes. In this hideous quarter the people of Aaron, Isaac, Abraham and Jacob are crowded pell-mell; these unfortunate folk, some of whom nonetheless acquire a little wealth, feed on fish-heads rejected as poisonous, and which cause certain specific diseases. This tainted food has the advantage of costing almost nothing.

Opposite Balata, on the far side of the Golden Horn, on an arid, bare, dusty slope, lies the cemetery that absorbs their sickly generations. The sun burns the shapeless stones of their tombs where not a blade of grass grows, not a single sheltering tree. The Turks sought to deny sweetness to the corpses of the proscribed, and insist on the Jewish Field of the Dead continuing to look like a bare stretch of road: they grudgingly allow the engraving of some mysterious Hebrew character or other on the cubes of stone roughly scattered over that desolate and accursed hillside.

What a contrast between these unhealthy-looking women, whose age one cannot discern, and the splendid Jewish women of Constantine (the city in Algeria), who are as stately in their progress as the Queen of Sheba, adorned like her with their dalmatics of half-parted damask, their belts with metal plates, their gold chains, and their headbands embroidered with spangles! They are of the same descent, though one would hardly think so. The latter might have posed for a Raphael Madonna; Rembrandt alone would have been capable of allowing the former a place in some magical scene of his, by gilding them, on a bitumen background, with those marvellous herring-red tones of which Amsterdam granted him the secret.

This same debasement is also noticeable among the men: none have the purity of type common among the Jews of North-Africa, who appear to have preserved the original stamp of the Orient.

The Turks, who accept Isa (Jesus) as a prophet, have made the Jews pay cruelly for procuring, as the former believe, his death; however it must be said that the latter are no longer mistreated as before, and that their lives and possessions are more or less safe from insult and extortion; but, plunged immutably in the mud, they are not yet reassured, and force themselves to continue the wretched commedia; still stinking, sordid and abased, they hide their treasure beneath rags. They take revenge on the Christians, Greeks and Turks by means of loans and interest. In the depths of these soiled huts, more than one Shylock, biding his time, runs his knife over the leather of his shoe, ready to remove his pound of flesh from Bassanio (see Shakespeare’s ‘The Merchant of Venice’); more than one rabbi pours ashes on his head, and utters cabbalistic conjurations, in order to obtain, from the deity, the chastisement of enemies long purged from the face of the world.

We finally left this sad and ignoble quarter, and entered the Phanar (Fener), where the distinguished Greeks live, a sort of West End neighbouring on that Court of Miracles; the stone houses constitute a fine architectural statement. Several have balconies supported by stepped consoles, or voluted modillions; others, older, recall the narrow facades of those small ‘hotels’ of the Middle Ages, half-fortress, half civil-residence; the walls are thick enough to support a siege, the iron shutters are bullet-proof, enormous grilles defend the narrow barbican-like windows, the cornices are denticulated, by choice, like battlements, and project as moucharabiehs (ornate latticed balconies), an innocent luxury of defence that serves only against fire, whose powerless tongues lick this stone quarter in vain.

Here, ancient Byzantium has taken refuge, here in obscurity live the descendants of the Comneni, the Doukas, the Paleologi, princes now lacking principalities, whose ancestors wore the purple, and who have imperial blood in their veins; their slaves treat them as kings, and they console themselves for their downfall by these simulacra of respect. Considerable wealth is piled up in these solid houses, ornately decorated within, though very simple without; for in the Orient luxury is timid, and hidden from sight. The Phanariots have long been famous for their diplomatic skill: they once directed all the international affairs of the Ottoman Porte; but their credit seems to have declined greatly since the Greek War of Independence.

At the end of the Phanar, one enters the Turkish streets which border the Golden Horn, in which an active commercial population swarms. At every step, one meets hammals carrying loads suspended from twin poles: while donkeys each supporting their respective ends of the two long planks attached to them, obstruct the traffic and mow down everything in their path whenever they are obliged to turn into a side street. The poor animals sometimes remain trapped against the walls of an over-narrow alley, unable to move forward or backward, which quickly generates an agglomeration of horsemen, pedestrians, porters, women, children, and dogs, who grumble, curse, squeal, and bark in all tones, until the donkey-driver grasps his beast by the tail, and raises the lock-gate, so to speak. Then the gathered crowd disperses and calm is restored, though not without a few prior blows being distributed, of which the donkeys, the innocent cause of the problem, receive the major part, as is their lot.

The ground rises in an amphitheatre, from the sea to the ramparts we had just skirted externally, and, above the tumultuous roofs of the Turkish houses, the eye catches here and there some fragment of crenellated wall, the arches of an ancient aqueduct which straddles the puny modern buildings, that are like pyres ready for firing which a match would suffice to ignite. How many Constantinoples have already seen the old blackened stones fall to ashes at their base! A hundred-years old Turkish house is a rarity in Istanbul.

My sais, who was walking with his hand resting on the rump of my horse, guided my friend and myself through the maze of crowded streets, and we soon arrived at the second bridge which crosses the Golden Horn; we regained, via Kassim-Pacha (Kasimpasa) , the slopes of the Petit-Champ-des-Morts, and he deposited us at the door of the Hôtel de France, without appearing tired from our lengthy journey.

As for myself, seated on my sofa, I leaned on the window-sill, and indulged in the sweetness of kief, a little dizzy from fatigue, and the opiate tobacco, with which I had loaded the bowl of my pipe. That evening, after supper, which was of brief duration, I was in no way tempted to go for a walk, as was my habit, along the front of the cafés of the Petit-Champ where Perote society meets.

Next day, being a little sore, I decided to go and enjoy a Turkish bath, for nothing is as relaxing, and I chose the Baths of Mahmud (the Mahmut Pasha Hamam, completed in 1466), near the Bazaar. They are the most beautiful and the largest in Constantinople.

The ancient tradition of public baths, lost among us, has been preserved in the Orient. Christianity, though preaching contempt for the material world, has gradually caused care for the perishable body to fall into disuse as overly-suggesting paganism. Some Spanish monk, I no longer know which, living after the conquest of Granada, preached against the use of the Moorish bathhouses, and declared those who would not renounce them guilty of sensualism and heresy.

In the Orient, where physical cleanliness is a religious obligation, the baths have retained all the features of their ancient Greek and Roman predecessors: they are large buildings of architectural appearance, with cupolas, domes, and columns; marble, alabaster, and coloured breccias having been employed in their construction; and are served by an army of scrapers, masseurs, and tellaks (bath-attendants), recalling the strigilists, malaxators and iatraliptes of Rome and Byzantium.

The client is received in a large room, its entrance opening onto the street and hung with a piece of tapestry. Near this door, squats the bath-keeper, between a box containing his takings, and a chest in which he keeps money, jewels, and other precious objects deposited by customers on entering, and for which he is responsible. Around this room, its temperature almost equal to that of the street, reign two superimposed galleries of a sort furnished with camp beds; a fountain darts a trickle of hot water into a double basin set in the centre of the marble floor which is shimmering wet. Around the fountain, a few pots of basil, mint, and other fragrant plants of whose perfume the Turks are very fond, are arranged.

Blue, white and pink-striped towels hang drying from ropes, or from the vault above as do the flags and banners in Westminster Abbey, and in the Saint-Louis Cathedral of the Invalides.

On the beds, bathers in swimsuits smoke, drink coffee, take sherbets, or sleep, wrapped to the chin like infants, until they are no longer sweating and can don their clothes again.

I ascended to the second gallery by a small wooden staircase, and was shown to a bed; and, when I had doffed my clothes, two tellaks wrapped a white towel in the shape of a turban round my head, and covered me from waist to ankles with a piece of Guinea cloth, fastened like the loincloths carved on Egyptian statues. At the bottom of the stairs, I found a pair of wooden slippers into which I placed my feet; and, my tellaks supporting me by the armpits, I passed from the first room into the second, which was at a higher temperature; I was left there for a few minutes to prepare my lungs for the heated air of the third room which was kept at about thirty-five to forty degrees.

The Ottoman baths differ from ours: a continuous fire burns beneath the marble slabs, and the water is poured onto them, evaporating as steam, rather than spurting from a boiler in strident jets. They are, in a sense, dry baths, and the extreme heat alone causes one to perspire.

Under a dome, lit by large greenish glass ‘portholes’ that let in only a vague light, seven or eight tomb-shaped slabs are arranged which receive the bodies of the bathers, who, stretched out like corpses on the dissection table, undergo a preliminary massage: the muscles are lightly pinched, and kneaded like soft dough until they are covered in a pearly sweat like that which forms round the ice-bucket in which a bottle of Champagne sits, which result is soon achieved.

Once the sweat from your open pores is trickling down your limbs, now more supple, you are lifted up, made to put your slippers back on to spare the soles of your feet from torrid contact with the paving, and are led to one of the niches set around the rotunda.

A white marble fountain, and basin, equipped with hot and cold taps, occupies the rear of each niche. Your tellak makes you sit beside the basin, arms his hands with camel-hair gauntlets, and crushes first your arms, then your legs, then your torso, so as to raise the blood to your skin, without scratching you or doing you the slightest harm, despite the apparent severity with which he performs this exercise.

Then he draws several bowlfuls of warm water from the basin, into a yellow copper bowl, and pours the liquid over your body. When you have dried a little, he recommences, rubbing you with the palm of his bare hand, and causing long greyish rolls of dirt to slide from your arms, which greatly surprises Europeans convinced of their cleanliness; with a sharp blow, the tellak removes them, and shows them to you with an air of satisfaction.

A fresh deluge of water carries away these offerings, and the tellak gently whips you with lengths of tow soaked in a soapy foam; he parts your hair, and cleans the skin of your head, an operation followed by another cataract of fresh water to avoid cerebral congestion which the rise in temperature could cause.

My bath-attendant was a young Macedonian boy of fifteen or sixteen years, whose skin, macerated by continual immersion, had acquired a uniform brown tone, and an incredible smoothness; he was all muscle, his plump flesh had simply evaporated, which did not prevent his being vigorous and in good health.

These various ceremonies complete, I was wrapped in dry towels, and led back to the bed, where two little lads massaged me one last time. I rested there for about an hour, in a drowsy reverie, drinking coffee and iced lemonade; and, when I emerged from the baths, I was so light, so energised, so supple, so free of fatigue, that it seemed to me that ‘the angels of heaven were walking beside me’! (See, perhaps, Genesis 19: 15-16)

Chapter 20: Bayram (the Festival of Eid-al-Fitre, or Breaking the Fast)

Ramadan was over: and, without wishing to tarnish anyone’s view of Muslim zeal, it may be said that the cessation of the fast is welcomed with general satisfaction; for, despite its dual nocturnal carnivals this Lent of theirs is no less painful than ours. At this time, every Turk renews their wardrobe, and nothing is prettier than to see the streets dappled with fresh costumes, in bright, cheerful colours, embellished with brilliant embroidery, instead of being marred by picturesquely sordid rags which are more pleasing in a painting by Alexandre-Gabriel Decamps than in reality; every Muslim now puts on what is richest and most cheerful: blue, pink, pistachio-green, cinnamon-yellow, and scarlet shine on all sides; the muslins of their turbans are clean, their slippers free of mud and dust; the metropolis of Islam has renewed its toilette from top to bottom. If a traveller arriving by steamer were to land at this moment, and depart the following day, he would leave Constantinople with a very different idea of it, than after a prolonged stay. The city of the Sultans would seem to him much more Turkish than it usually is.

In the streets, musicians with flutes and drums, who during Ramadan have played serenades beneath the windows of the most important houses, promenade about. When the din they make has lasted long enough to attract the attention of the inhabitants of the dwelling, a grating is moved aside, and a hand appears which lets fall a shawl, a piece of cloth, a belt, or some similar object, which is immediately hung on the end of a pole loaded with gifts of the same kind: it is a form of baksheesh which recognises the trouble taken by the instrumentalists, usually Dervish novices. They are a kind of Muslim pifferari (strolling musicians), paid thus, instead of being thrown a sou or a para each time they have performed.