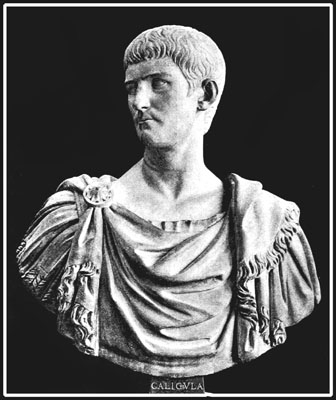

Suetonius: The Twelve Caesars

Book IV: Gaius Caligula

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2010 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book Four: Gaius Caligula

- Book Four: I His Father, Germanicus

- Book Four: II Piso Suspected of Germanicus’s Death

- Book Four: III The Character of Germanicus

- Book Four: IV Germanicus’s Popularity

- Book Four: V The Grief at Germanicus’s Death

- Book Four: VI Prolonged Mourning for Germanicus

- Book Four: VII Germanicus’s Children

- Book Four: VIII The Birth of Gaius (Caligula)

- Book Four: IX The Army’s Devotion to Him

- Book Four: X His Childhood and Youth

- Book Four: XI His Cruel Nature

- Book Four: XII Parricide

- Book Four: XIII His Joyous Reception by the Roman People

- Book Four: XIV His Accession to Power

- Book Four: XV His Filial Piety and Moratorium on Past Charges

- Book Four: XVI His Other Inaugural Actions

- Book Four: XVII His Consulships

- Book Four: XVIII His Public Entertainments in Rome

- Book Four: XIX His Bridge at Baiae

- Book Four: XX His Entertainments in the Provinces

- Book Four: XXI His Public Works

- Book Four: XXII His Pretensions to Divinity

- Book Four: XXIII His Treatment of his Relatives

- Book Four: XXIV His Incest With and Prostitution of his Sisters

- Book Four: XXV His Marriages

- Book Four: XXVI His Cruel Treatment of Others

- Book Four: XXVII His Savage Nature

- Book Four: XXVIII His Murder of Exiles

- Book Four: XXIX His Morbid Wit

- Book Four: XXX Oderint, Dum Metuant

- Book Four: XXXI His Desire for Disasters

- Book Four: XXXII His More Casual Cruelties

- Book Four: XXXIII His Cynical Humour

- Book Four: XXXIV His Hatred of Famous Men

- Book Four: XXXV His Envy of Others

- Book Four: XXXVI His Sexual Immorality

- Book Four: XXXVII His Extravagance

- Book Four: XXXVIII His Plunder and Extortion

- Book Four: XXXIX His Auctions in Gaul

- Book Four: XL His New Methods of Taxation

- Book Four: XLI His Other Nefarious Methods of Raising Money

- Book Four: XLII His Daughter’s Dowry

- Book Four: XLIII His Expedition to Germany

- Book Four: XLIV The Surrender of a British Prince

- Book Four: XLV Mock Warfare

- Book Four: XLVI Victory Over the Sea

- Book Four: XLVII Preparations for a Triumph

- Book Four: XLVIII An Attempt Against the Legions

- Book Four: XLIX His Intentions Towards the Senate

- Book Four: L His Appearance and Health

- Book Four: LI His Over-Confidence and Fears

- Book Four: LII His Mode of Dress

- Book Four: LIII His Oratory

- Book Four: LIV His Gladiatorial and Theatrical Skills

- Book Four: LV His Favourites

- Book Four: LVI The Conspiracies Against Him

- Book Four: LVII Portents of His Assassination

- Book Four: LVIII His Death

- Book Four: LIX His Cremation

- Book Four: LX Confusion Reigns

Book Four: Gaius Caligula

Book Four: I His Father, Germanicus

Caligula’s father, Germanicus, who was the son of Drusus the Elder and Antonia the Younger, was adopted (in 4AD) by Germanicus’s paternal uncle,Tiberius. He served as quaestor (in 7AD) five years before the legal age and became consul (in 12AD) without holding the intermediate offices. On the death of Augustus (in AD14) he was appointed to command the army in Germany, where, his filial piety and determination vying for prominence, he held the legions to their oath, though they stubbornly opposed Tiberius’s succession, and wished him to take power for himself.

He followed this with victory in Germany, for which he celebrated a triumph (in 17AD), and was chosen as consul for a second time (18AD) though unable to take office as he was despatched to the East to restore order there. He defeated the forces of the King of Armenia, and reduced Cappadocia to provincial status, but then died at Antioch, at the age of only thirty-three (in AD19), after a lingering illness, though there was also suspicion that he had been poisoned. For as well as the livid stains which covered his body, and the foam on his lips, the heart was found entire among the ashes after his cremation, its total resistance to flame being a characteristic of that organ, they say, when it is filled with poison.

Book Four: II Piso Suspected of Germanicus’s Death

The general belief was that Tiberius cunningly contrived his death through the agency and with the connivance of Gnaeus Piso, the then Governor of Syria who, concluding that he had no alternative but to give offence to one of the two, the father or the adopted son, displayed an unrelenting enmity towards Germanicus, in words and actions, even when Germanicus was dying. As a result Piso narrowly escaped lynching in Rome on his return, and was condemned to death by the Senate.

Book Four: III The Character of Germanicus

All considered Germanicus exceptional in body and mind, to a quite outstanding degree. Remarkably brave and handsome; a master of Greek and Latin oratory and learning; singularly benevolent; he was possessed of a powerful desire and vast capacity for winning respect and inspiring affection.

His scrawny legs were less in keeping with the rest of his figure, but he gradually fleshed them out by assiduous exercise on horseback after meals. He often killed enemy warriors in hand-to-hand combat; still pleaded cases in the courts even after receiving his triumph; and left various Greek comedies behind amongst other fruits of his studies.

At home and abroad his manners were unassuming, such that he always entered free or allied towns without his lictors.

Whenever he passed the tombs of famous men, he always offered a sacrifice to their shades. And he was the first to initiate a personal search for the scattered remains of Varus’s fallen legionaries, and have them gathered together, so as to inter them in a single burial mound.

He showed such mildness and tolerance towards his detractors, whoever they were, regardless of their motives, that he could not even bring himself to break with Piso, though the man was countermanding his orders, and persecuting his dependants, until he discovered that spells and potions were being employed against him. Even then he simply renounced Piso’s friendship formally, in the time-honoured way, and instructed his household to avenge him if evil befell him.

Book Four: IV Germanicus’s Popularity

Germanicus reaped rich rewards from his virtuous conduct, being so respected and loved by all his kin, not to mention the rest of his associates, that Augustus, after hesitating for some time as to whether to appoint him his successor, instructed Tiberius to adopt him.

He was so popular with the masses, according to many sources, that if he arrived at or left a location, his life was sometimes in danger from the vast crush of people who came to greet him or mark his departure. Indeed, on his return from Germany, after quelling the unrest there, the whole Praetorian Guard turned out to meet him, though only two cohorts had been so ordered, and the entire populace of Rome, regardless of age, sex or rank, thronged the way as far as the twentieth milestone.

Book Four: V The Grief at Germanicus’s Death

In the aftermath of Germanicus’s death, even greater and more profound expressions of public regard for him were evoked. On the day when his death was announced, crowds stoned the temples, and toppled the divine altars, while others flung their household gods into the street, or abandoned their new-born children. It is said that even barbarians who were at war with Rome, or fighting among themselves, made peace unanimously, as if the whole world had suffered a personal loss. It is claimed that princes had their beards and even their wives’ heads shaved, as a sign of deepest grief; while, in Parthia, the King of Kings himself cancelled his hunting parties and royal banquets, in the manner of public mourning there.

Book Four: VI Prolonged Mourning for Germanicus

The Roman people, filled with sadness and dismay at the initial reports of his illness, had been awaiting further news, when suddenly one night wild rumours of his recovery had spread, and people had crowded to the Capitol from every quarter, torches in their hands, some leading sacrificial victims. The Temple gates had been all but demolished by them, in their eagerness to push through and offer their prayers and vows. Tiberius himself was roused from sleep by the shouts of rejoicing, and the widespread chant of:

‘Rome is well, our country’s well: he’s well, Germanicus!’

But when it became known that he had died (his death occurring on October 10th, AD19), neither official expressions of sympathy nor public decrees could restrain the demonstrations of grief, and they continued throughout December’s Saturnalia.

Germanicus’s renown and the regret for his loss were accentuated by the terror that followed, since there was a general and well-merited belief that Tiberius’s cruelty, which was fully evidenced by his behaviour thereafter, had only been held in check by his respect for and awe of Germanicus.

Book Four: VII Germanicus’s Children

Germanicus had married Agrippina the Elder, daughter of Marcus Agrippa and Julia the Elder, and she had borne him nine children. Two died in infancy, another in early childhood, a charming boy whose statue, portraying him as Cupid, Livia dedicated in the Temple of Capitoline Venus, while Augustus had a second statue of him in his bedchamber which he used to kiss fondly on entering the room.

The other children survived their father: three girls, Agrippina the Younger, Drusilla and Livilla, born in successive years; and three boys, Nero, Drusus, and Gaius Caesar (Caligula). Of the sons, Nero and Drusus were accused by Tiberius of being public enemies, and subsequently convicted of being so, by the Senate.

Book Four: VIII The Birth of Gaius (Caligula)

Gaius Caesar (Caligula) was born on the 31st of August AD12, in the consulship of his father, Germanicus, and Gaius Fonteius Capito. The sources disagree as to his place of birth. Gnaeus Lentulus Gaetulicus claims it was Tibur (Tivoli), Pliny the Elder, says it was among the Treveri in the village of Ambitarvium, above Confluentes (the site of Koblenz) at the junction of the Moselle and Rhine. Pliny adds as evidence that altars exist there, inscribed ‘IN HONOUR OF AGRIPPINA’S PUERPERIUM.’

A verse that circulated soon after he became Emperor suggests he was born in the winter-quarters of the legions:

‘Born in a barracks, reared among Roman arms,

A sign from the start he was bound to be Emperor.’

I find however that the public records give his birthplace as Antium (Anzio). Pliny rejects Gaetulicus’s version, and accuses him of telling a lie simply to flatter the boastful young prince and add to his fame by claiming he came from Tibur, a city sacred to Hercules. And that he lied with more assurance because Germanicus did have a son, born a year or so earlier, also named Gaius Caesar, and of whose lovable disposition and untimely death I have spoken, who was indeed born at Tibur.

Pliny’s chronology is in error, though, since the historians of Augustus’ time agree that Germanicus was not sent to Gaul until the end of his consulship, by which time Gaius (Caligula) had already been born. Nor do the altar inscriptions add weight to Pliny’s opinion, since Agrippina gave birth in Gaul to two daughters, and the term puerperium (childbirth) is used regardless of the child’s sex, formerly girls being called puerae for puellae, just as boys were called puelli for pueri. Then we have a letter of Augustus to Agrippina, his granddaughter, written a few months before his death (in AD14), concerning this Gaius (Caligula), since no other child of that name was alive at the time, which reads: ‘Yesterday I made arrangements for Talarius and Asillius to bring your son Gaius to you on the eighteenth of May, the gods being willing. I am also sending one of my slaves, a physician, with him, whom as I have written to Germanicus he may retain if he wishes. Farwell, my dear Agrippina, and take care that you reach your Germanicus in good health.’

It seems clear enough that Gaius (Caligula) could not have been born in a country to which he was first taken from Rome when nearly two years old! The letter weakens our confidence also in those lines of verse, which in any case are anonymous. We must therefore accept the sole testimony of the public records, especially since he loved Antium as if it were his native place, always preferring it to any other place of relaxation, and when weary of Rome even thought of making it his seat of power, and housing the government there.

Book Four: IX The Army’s Devotion to Him

His surname Caligula (‘Little Boot’) was bestowed on him affectionately by the troops because he was brought up amongst them, dressed in soldier’s gear. The extent of their love and devotion for him, gained by his being reared as one of them, is spectacularly evident from an undeniable incident when they threatened to mutiny after Augustus’s death, and though launched on the path of madness, were instantly calmed by sight of Caligula. It was only when they realised he was being spirited away to the nearest town for protection from the danger they presented, that they quietened down, and hung on to his carriage, in contrition, pleading to be spared this disgrace.

Book Four: X His Childhood and Youth

Caligula accompanied his father, Germanicus, to Syria (in AD19). On his return, he lived with his mother, Agrippina the Elder until she was exiled (in 29AD), and then with his great-grandmother Livia. When Livia died (in 29AD), he gave her eulogy from the rostra even though he was not of age. He was then cared for by his grandmother Antonia the Younger, until at the age of eighteen Tiberius summoned him to Capreae (Capri, in AD31). On that day he assumed his gown of manhood and shaved off his first beard, but without the ceremony that had attended his brothers’ coming of age.

On Capraea, though every trick was tried to lure him, or force him, into making complaints against Tiberius, he ignored all provocation, dismissing the fate of his relatives as if nothing had occurred, affecting a startling indifference to his own ill-treatment, and behaving so obsequiously to his adoptive grandfather, Tiberius, and the entire household, that the quip made regarding him was well borne out, that there was never a better slave or a worse master.

Book Four: XI His Cruel Nature

Even in those days, his cruel and vicious character was beyond his control, and he was an eager spectator of torture and executions meted out in punishment. At night, disguised in wig and long robe, he abandoned himself to gluttony and adulterous behaviour. He was passionately devoted it seems to the theatrical arts, to dancing and singing, a taste in him which Tiberius willingly fostered, in the hope of civilizing his savage propensities. The old man’s innate shrewdness clearly recognized the signs, and now and then would remark that Caligula’s life would prove the death of him and the ruin of all, and that he was nursing a viper for Rome, and a Phaethon for the world.

Book Four: XII Parricide

Not long afterwards, Caligula married Junia Claudilla (in AD33), daughter of the nobleman, Marcus Silanus. He was then appointed augur in place of his brother Drusus, being promoted to the priesthood before he was invested with the former office, on the grounds of his dutiful behaviour and sound character. Since Sejanus’s execution (in AD31) on suspicion of treason, the Court had become an empty and desolate shell, and this promotion gradually accustomed him to the view that the succession was his. To improve his chances, after Junia died in childbirth, he seduced Ennia Naevia, the wife of Macro, commander of the Praetorian Guard, not only promising to marry her if he became Emperor, but guaranteeing it on oath in a written contract, and so through her he wormed his way into Macro’s favour.

Some say he then poisoned Tiberius, ordering the Imperial ring to be removed while Tiberius still breathed, and then, suspecting that the Emperor was trying to cling onto it, having him smothered with a pillow, or even throttling him with his own hands, later sentencing a freedman to death by crucifixion, for protesting openly at the crime. The story may well be true, since various sources claim Caligula himself subsequently admitted, if not to actual parricide, at least at some point to contemplation of that crime, by boasting endlessly of his filial piety in showing pity after entering the bedroom of the sleeping Tiberius, knife in hand, to avenge his mother and brothers, but casting the weapon aside, and leaving the room again, an event of which Tiberius had learned, but had hesitated to investigate, or take action on.

Book Four: XIII His Joyous Reception by the Roman People

Caligula’s accession (in 37AD) gratified the deepest wishes of the Roman people, not to say the whole empire, since he was the ruler most desired by the majority of soldiers and provincials, many of whom were aware of him from infancy, as well as the mass of Roman citizens, not only because of their memories of his father Germanicus, but also through pity for a family that had been all but wiped out.

So when he set out for Rome, from Misenum, though he was dressed in mourning and escorting Tiberius’s body, his progress was marked by the erection of altars, the offering of sacrifices, and the blaze of torches, and he was met by a dense and joyous throng, who shouted out propitious names, calling him their ‘star’, their ‘pet’, their ‘little one’ their ‘chick’.

Book Four: XIV His Accession to Power

On entering the City (on the 28th of March, AD37) full and absolute power was conferred on him, by unanimous consent of the Senate and the people, a crowd of whom forced their way into the House. The Senate also overruled the terms of Tiberius’s will, by which he had named his other grandson Gemellus, who was still a child, joint heir with Caligula.

The public celebrations were so extensive that within the following three months, or less, more than a hundred and sixty thousand sacrificial victims were offered on the altars.

A few days after his entry into the City, when he crossed to the prison islands off Campania, vows were offered for his prompt return, and not even the slightest opportunity was missed of showing anxiety and regard for his safety. When he fell ill (in October) crowds surrounded the palace at night. People vowed to fight as gladiators, or posted signs offering to die, if their prince’s life might be spared. And to this outpouring of love from the citizens of Rome was added the marked devotion of foreigners.

For example, Artabanus II, King of the Parthia, always vociferous in his hatred of, and contempt for, Tiberius, willingly sought Caligula’s friendship, attended a conference with the consular Governor, and before re-crossing the Euphrates, paid homage to the Roman eagles and standards, and the statues of the Caesars.

Book Four: XV His Filial Piety and Moratorium on Past Charges

Caligula courted popularity in every way possible, in order to rouse popular devotion towards him. Having delivered a tearful eulogy in honour of Tiberius, in front of a vast crowd, and giving him a magnificent funeral, he promptly sailed for Pandataria and the Pontian Islands to recover the ashes of his mother, Agrippina the Elder, and his brother Nero, the tempestuous weather making his display of filial piety even more noteworthy. He treated the ashes with great reverence, placing them in their urns with his own hands. With no less theatre, he transported the urns to Ostia aboard a bireme, flag flying, and from there upriver to Rome, where they were carried on twin biers, at midday when the streets were crowded, from the Tiber to the Mausoleum of Augustus by the most distinguished knights of the Equestrian Order. He established ceremonial funeral sacrifices, to be offered annually, as well as games in the Circus to honour his mother, her image to be paraded in a carriage during the procession, while in memory of his father the month of September was renamed ‘Germanicus’.

At a stroke, by a single Senate decree, he awarded his paternal grandmother Antonia the Younger every honour that Livia Augusta had received in her whole lifetime. Then he appointed his uncle Claudius, who till then had been simply a Roman knight, his colleague in the consulship, and adopted his paternal cousin Tiberius Gemellus, when he came of age, granting him the official title ‘Prince of the Youths’. His sisters were included in all oaths, as follows: ‘…and I will not count myself or my children dearer to me than Gaius or his sisters’, and in the proposals of the consuls: ‘Happiness and good fortune be with Gaius Caesar and his sisters.’

An equally popular action was his recall of those who had been condemned and exiled, and the dismissal of all cases pending from earlier times; and to further reassure any informers and witnesses involved in the charges against his mother and brothers, he had all the related documents brought to the Forum and burned, having first called the gods as witness to the fact that he had not touched, let alone read, them.

He refused to read a note passed to him regarding his own safety, on the grounds that nothing he had done gave anyone reason to hate him, and he had no wish to grant informers a hearing.

Book Four: XVI His Other Inaugural Actions

Caligula banished the sexual perverts known as spintriae from the City, and was barely restrained from having them all drowned.

He allowed the works of Titus Labienus, Cremutius Cordus, and Cassius Severus, banned by the Senate, to be hunted out, republished, and read freely, stating that it was in his interest to allow historical records to be handed down to posterity. And he published the Imperial Accounts, reviving a practice of Augustus’s discontinued by Tiberius.

He revised the list of Roman knights, strictly and scrupulously, but fairly, publicly denying mounts to those guilty of wicked or scandalous actions, but simply omitting to read out the names of men convicted of lesser offences. And he attempted to restore the electoral system by reviving the custom of voting for magistrates, who were given full authority without recourse to himself. He then reduced the burden on jurors by creating a fifth division to augment the other four.

Despite Tiberius’s will having been set aside by the Senate, Caligula paid faithfully, and without demur, all the legacies bequeathed there, as well as those in the will of Julia Augusta (Livia) the provisions of which Tiberius had suppressed.

Caligula abolished the half-per-cent tax on sales by auction within Italy. He also paid compensation to those who had sustained losses through fire-damage.

Any royal dynasty he restored to the throne was awarded the arrears of tax and revenue which had accumulated prior to its restoration; for example, Antiochus of Commagene received a million gold pieces accrued to the Treasury. And to show that he encouraged noble actions, he awarded a freedwoman eight thousand in gold who though tortured severely had not revealed her patron’s guilt.

All this resulted in his being awarded various honours, including a golden shield, to be carried to the Capitol annually, on the appointed day, by members of the priestly colleges, and escorted by the Senate, while the boys and girls of the nobility sang a choral ode in praise of his virtues. It was also decreed that the Parilia should be formally appointed as the day he assumed power, as a token of the fact that with his accession Rome had been re-born.

Book Four: XVII His Consulships

He held four consulships (in AD37, and 39-41) the earliest from the first of July for two months, the second from the first of January for thirty days, the third up to the thirteenth of January, and the fourth up to the seventh of January, the last three being in sequence. The third he assumed without a colleague, while he was at Lugdunum, not, as some consider, because of arrogance or disregard for precedent, but because the news of his fellow consul’s death just before the New Year had not yet reached him from Rome.

He twice distributed three gold pieces each to the populace, and twice gave a lavish banquet for the Senators and members of the Equestrian Order, together with their wives and children. At the second banquet he made a gift of togas to the men, and red and purple scarves to the women and children. And to make a permanent addition to public rejoicing, he added a day to the Saturnalia, which he called Juvenalis, the Day of Youth.

Book Four: XVIII His Public Entertainments in Rome

Caligula held several gladiatorial contests, some in Statilius Taurus’s amphitheatre others in the Enclosure, which included matched pairs of choice African and Campanian prize-fighters. He sometimes assigned the honour of presiding over the shows to magistrates or friends, rather than attending himself.

He staged many theatrical events, of various kinds and in various locations, sometimes at night, illuminating the whole City. He would scatter tokens about, too, entitling people to gifts as well as the basket of food which each man received. He once sent his own share of food to a Roman knight who was enjoying the banquet with great appetite and relish, and on another occasion a Senator received a commission as praetor, with blatant disregard of the normal process, for the same reason.

He also mounted Games in the Circus, from morning to evening, filling the intervals between races with panther-baiting or the Troy Game. Some of these events were spectacular, the Circus being decorated with red and green, and the charioteers being men of Senatorial rank. Once, he commissioned impromptu games, because a few people on neighbouring balconies called for them, as he was inspecting the preparations in the Circus from the Gelotian House.

Book Four: XIX His Bridge at Baiae

One novel and unheard of spectacle which he devised, was achieved by bridging the gulf between Baiae (Baia) and the mole at Puteoli (Pozzuoli), a distance of about three thousand six hundred paces (over three and a quarter English miles) by gathering merchant ships and mooring them in a double line, then piling earth on them to make a sort of Appian Way.

Caligula rode back and forth over this bridge for two consecutive days. On the first day he was on horseback, resplendent in a crown of oak leaves, with sword, circular shield, and a cloak in cloth of gold, his mount dressed with military insignia. On the second he wore charioteer’s costume, and was pulled by a famous pair of horses, with a boy-hostage from Parthia, Dareus, beside him, and the entire Praetorian Guard, plus a crowd of his friends in Gallic chariots, behind.

Now I know that many people think Caligula devised the bridge to outdo Xerxes, who excited widespread admiration by bridging the much narrower Hellespont, while others claim he wanted some immense feat of engineering to inspire fear in Britain and Germany, on which he had designs. But when I was a boy, my grandfather used to say, in my hearing, that the reason behind it, as divulged by the courtiers in Caligula’s confidence, was a comment Thrasyllus the astrologer made to Tiberius, who was concerned about the succession, and inclined to nominate his natural grandson, that Gaius had no more chance of becoming Emperor than of galloping to and fro over the gulf at Baiae.

Book Four: XX His Entertainments in the Provinces

Caligula gave several entertainments abroad, including Urban Games at Syracuse in Sicily, and miscellaneous Games at Lugdunum in Gaul. During the latter, he held a contest in Greek and Latin oratory, in which the losers gave the winners prizes, and had to compose speeches in praise of them, while the least successful were commanded to erase their efforts with a sponge, or with their tongue, unless they preferred to be beaten with sticks, and flung in the river nearby.

Book Four: XXI His Public Works

He completed those public projects which had been left half-finished by Tiberius, namely the Temple of Augustus and the Theatre of Pompey. He also began construction of an aqueduct near Tibur (Tivoli) and an amphitheatre next to the Enclosure: the former being completed by his successor, Claudius, though work on the latter was discontinued.

He had the city walls of Syracuse, which had become dilapidated over time, repaired, as well as the city’s temples. He also planned to restore Polycrates’ palace at Samos; to complete the Temple of Apollo at Didyma, near Miletus; to build a city high in the Alps; and above all to cut a canal through the Isthmus in Greece, to which end he sent a senior centurion to perform a survey.

Book Four: XXII His Pretensions to Divinity

So much for the Emperor: it remains now to speak of the Monster.

He had already assumed various titles, calling himself ‘Pious’, ‘Child of the Camp’, ‘Father of the Army’ and ‘Greatest and Best of Caesars’, but when he chanced to hear a dispute among a group of foreign kings, who had travelled to Rome to pay him their respects, concerning their pedigree, he declaimed Homer’s line:

‘One lord, let there be, one King alone.’

And came near to assuming a royal diadem at once, turning the semblance of a principate into an absolute monarchy. Indeed, advised by this that he outranked princes and kings, he began thereafter to claim divine power, sending to Greece for the most sacred or beautiful statues of the gods, including the Jupiter of Olympia, so that the heads could be exchanged for his own.

He then extended the Palace as far as the Forum, making the Temple of Castor and Pollux its vestibule, and would often present himself to the populace there, standing between the statues of the divine brothers, to be worshipped by whoever appeared, some hailing him as ‘Jupiter Latiaris’.

He also set up a special shrine to himself as god, with priests, the choicest sacrificial victims, and a life-sized golden statue of himself, which was dressed each day in clothes of identical design to those he chose to wear. The richest citizens used all their influence to win priesthoods there, and were forced to bid highly for the honour. The sacrificial victims comprised flamingos, peacocks, black grouse, white-breasted and helmeted guinea fowl, and pheasants, offered, according to species, on separate days.

When the moon was full and bright, he would invite the goddess to his bed and his embrace, while during the day he would have intimate conversations with Capitoline Jupiter, whispering to the statue and then pressing his ear to its mouth, sometimes speaking aloud in anger, and once threatening the god: ‘Raise me from the earth, or I’ll raise you.’ Finally he announced that the god had won him over by his entreaties and invited him to share his home, so he bridged the Temple of Divine Augustus and joined his Palace to the Capitol. Then he laid the foundations of a new house in the precincts of the Capitol itself, in order to be even closer.

Book Four: XXIII His Treatment of his Relatives

Because of Agrippa’s humble origins, Caligula hated to be thought of as his grandson, or be addressed as such, and flew into a rage if anyone in speech or song included Agrippa among the ancestors of the Caesars.

He proclaimed that his mother, Agrippina the Elder, was a result of Augustus’s incest with his daughter Julia the Elder, (and therefore not Agrippa’s daughter), and not content with denigrating Augustus in this way, he refused to allow the annual celebrations of the victories at Actium and off Sicily, on the grounds that they had proved disastrous and ruinous for the people of Rome.

He often called his great-grandmother, Livia Augusta, ‘Ulysses in a petticoat’, and dared to describe her in a letter to the Senate as base-born, claiming that her maternal grandfather Aufidius Lurco had been merely a local senator at Fundi, though the public records show that he held high office in Rome. And when his grandmother Antonia the Younger asked for a private audience, he refused unless Macro, the Guards Commander, was present, hastening her death with such indignities and irritations, though some say he poisoned her too. And when she was dead, he showed her no respect, merely glancing at her funeral pyre as it burnt, from his dining-room window.

His brother, Tiberius Gemellus, he had put to death (in AD37/38), sending a military tribune to carry out the order, without warning. And he drove his father-in-law, Silanus, to commit suicide by cutting his throat with razor. His charge against Gemellus was that he had insulted him by taking an antidote against poison, his breath smelling of it, when it was merely medicine for a chronic and worsening cough. Silanus was accused of failing to follow the Imperial ship when it put to sea in a storm, and of remaining behind in the hope of seizing the City if Caligula perished, whereas he merely wished to avoid the unpleasant symptoms of the seasickness to which he was prone.

His uncle, Claudius, he preserved, simply as an object of ridicule.

Book Four: XXIV His Incest With and Prostitution of his Sisters

He habitually committed incest with each of his three sisters, seating them in turn below him at large banquets while his wife reclined above. It is believed that he violated Drusilla’s virginity while a minor, and been caught in bed with her by his grandmother Antonia, in whose household they were jointly raised. Later, when Drusilla was married to Lucius Cassius Longinus, an ex-consul, he took her from him and openly treated her as his lawful married wife. When he fell ill he made her heir to his estate and the throne.

When Drusilla died (in 38AD) he declared a period of public mourning during which it was a capital offence to laugh, or bathe, or to dine with parents, spouse or children. Caligula himself was so overcome with grief that he fled the City in the middle of the night, and travelled through Campania, and on to Syracuse, returning again with the same degree of haste, and without cutting his hair or shaving. From that time forwards whenever he took an important oath, even in public or in front of the army, he always swore by Drusilla’s divinity.

He showed less affection or respect for his other sisters, Agrippina the Younger and Livilla, often prostituting them to his favourites, so that he felt no compunction in condemning them during the trial of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, as adulteresses, as well as conspirators against himself, not only producing their handwritten letters, obtained by fraud and seduction, but also dedicating three swords to Mars the Avenger, which the accompanying inscription described as weapons intended to kill him.

Book Four: XXV His Marriages

It would be hard to say which was more shameful, the way he contracted his marriages, the way he dissolved them, or his behaviour as a husband.

He attended one marriage that of Livia Orestilla to Gaius Calpurnius Piso only to have the bride carried straight from the ceremony to his own house, and then, a few days later, divorced her. Two years later, suspecting that she had returned to her former husband, he banished her. Others say that at the wedding feast, as he reclined opposite Piso, he told him: ‘No dallying with my wife’ and immediately dragged her from the table. He announced the next day that he had taken a wife as Romulus and Augustus were wont to do.

When he heard someone remark that the grandmother of Lollia Paulina, who was the wife of Publius Memmius Regulus, a Governor of consular rank, was once a famous beauty, he suddenly summoned Lollia from her province, forced Memmius to divorce her then married her himself, but quickly discarded her again, forbidding her ever to sleep with another man.

As for Caesonia, who was neither young nor beautiful, had three daughters by another man, and was wildly promiscuous and extravagant, he not only loved her more passionately for it, but also more faithfully, taking her out riding, and showing her to the soldiers, dressed in a cloak with helmet and shield: while he exhibited her to his friends stark naked. He did not honour her with the title of wife until she had given him a child, announcing his paternity and the marriage on the very same day.

This child, whom he named Julia Drusilla, he carried round all the temples of the goddesses, before finally entrusting her to Minerva’s lap, calling on that goddess to nurture and educate his daughter. Nothing persuaded him more clearly that she was his own issue than her violent temper, which was so savage the infant would tear at the faces and eyes of her little playmates.

Book Four: XXVI His Cruel Treatment of Others

It would be tedious and pointless to recount in detail his behaviour towards relatives and friends, such as his cousin King Ptolemy of Mauretania, who was the grandson of Mark Antony by his daughter Cleopatra Selene) or Macro, the Guards Commander, and his wife Ennia, who helped Caligula to power. All were rewarded with violent death for their kinship or loyalty.

Nor was he any more respectful or temperate in his dealings with Senators, forcing some of the most senior to run behind his chariot for miles, clad in their togas; or wait on him, dressed in the short linen tunics of slaves, at the head or foot of his dining-couch. He would continue to send for men he had secretly put to death, as though they were alive, waiting days before claiming falsely that they must have committed suicide.

When the consuls forgot to proclaim his birthday, he dismissed them, and left the State bereft of its highest officers for three days. And when one of his quaestors was accused of conspiracy, he had the clothes stripped from him and spread beneath the soldiers’ feet to give them a firmer foothold while they flogged him.

He was as cruel and arrogant in his dealings with other ranks of society. Disturbed at night by a noisy crowd queuing to secure free seats in the Circus, he had them driven away with clubs, and in the panic twenty Roman knights, and as many married women, were crushed to death with a host of others.

At the theatre, he would scatter tickets to the crowd ahead of time, to cause trouble between the knights and the commons, some equestrian seats being allocated twice. And sometimes at gladiatorial shows when the sun was hottest, he would have the canopies drawn back and prevent anyone leaving; or scrap the normal entertainment and pit useless old gladiators against mangy beasts; or hold mock duels between honest householders noted for some obvious disability.

And on occasions too, he would shut the granaries, and let the people starve.

Book Four: XXVII His Savage Nature

His brutal nature is most clearly revealed by the following events.

When the price of cattle to feed the wild beasts for one of his gladiatorial shows seemed too high, he chose criminals to be devoured instead. He simply stood in the middle of a colonnade and reviewed the line of convicts, without bothering to read the charges against them. He then had them all, ‘from one bald head to the other’, led away.

He made one man, who had sworn to fight in the arena if the Emperor recovered from illness, fulfil his pledge. Caligula watched the sword-fight and, when the man won, only relented and let him go after many entreaties. A second, who had offered his life on the same condition, but had not yet discharged his vow, he handed to his slaves with instructions to deck the man in sacred wreaths and ribbons, drive him through the streets while calling for him to fulfil his oath, and then toss him from the embankment into the Tiber.

Many men of good rank were branded then, permanently disfigured by the mark of the iron, and were condemned to labour in the mines, or at road-building; or were caged like animals on all fours, or thrown to the wild beasts; or had their bodies sawn apart. And these punishments were often meted out not for serious offences, but merely for criticising the entertainments he gave, or for failing to swear by his divine Genius. And he even compelled fathers to watch their own sons die, sending a litter for one man who claimed to be too ill to travel; forcing another to attend dinner with him immediately afterwards, and putting on a great show of affability while trying to prod the wretched man into smiling and jesting.

The manager of his gladiatorial and wild-beast shows he had beaten with chains in his presence for several days in succession, and had the man kept alive until the stench of suppurating brains became intolerable. And he had the author of some Atellan farces burnt alive in the centre of the amphitheatre’s arena, simply because of a line containing a double-entendre that caused public amusement. When a Roman knight, on the verge of being thrown to the wild beasts, shouted out his innocence, Caligula had him brought back and his tongue cut out, and then had the sentence fulfilled.

Book Four: XXVIII His Murder of Exiles

He once chose to ask an exile, who had been recalled, how he had passed the time. The man replied, fawningly: ‘I prayed constantly to the gods for what has actually happened: that Tiberius might die and you might become Emperor.’ The answer had Caligula imagining that all the exiles were now praying similarly for his death, so he had them killed by agents sent from island to island.

Deciding he wished one Senator torn to pieces, he persuaded others to attack the man as a public enemy when he entered the House, stab him with their pens, and throw him to the rest to be dismembered, nor was he satisfied until the man’s trunk, limbs, and guts had been dragged through the streets and heaped up at his feet.

Book Four: XXIX His Morbid Wit

Caligula added brutality of language to the enormity of his crimes. He used to say that he approved and admired nothing in his own character more highly than his ‘impassivity’ in other words his shamelessness.

When his grandmother, Antonia the Younger, gave him the benefit of her advice, he not only shut his ears, but replied: ‘Remember, I can do whatever I wish to whoever I wish.’

When he was on the verge of murdering his brother, Gemellus, and thought Gemellus had taken drugs to try and counteract poison, he inquired: ‘An antidote, against Caesar?’ And on exiling his sisters, Agrippina the Younger and Livilla, he remarked threateningly that he could employ ‘swords as well as islands’.

To a spate of requests for an extension of leave from an ex-praetor, who had retired to Anticyra for his health, Caligula replied with an order for his execution, adding that since a long course of hellebore had failed (Anticyra being famous for its hellebore), the man badly needed to be bled.

When signing a list of prisoners to be put to death in ten days time he called it ‘clearing his accounts’. And having sentenced several Gauls and Greeks to die together, he boasted of having ‘subdued Gallograecia’.

Book Four: XXX Oderint, Dum Metuant

His preferred method of execution was by the infliction of many slight wounds, and his order, issued as a matter of routine, became notorious: ‘Cut him so he knows he is dying.’ And when, through an error in the names, someone other than the intended victim was killed, he would say that the victim had deserved the same fate anyway.

He often quoted Accius’s line:

‘Let them hate me, so long as they fear me.’

And he would often abuse the Senators indiscriminately, calling them friends of Sejanus, and informers against his mother and brothers, thereupon producing the documents he was supposed to have burned, and justifying Tiberius’s cruelty on the grounds that Tiberius was unable to ignore such a volume of accusations. The Equestrian order he constantly reviled, also, as devotees of the theatre and the arena.

On one occasion, when the crowd applauded a team other than the one he favoured, he shouted in anger: ‘I wish the people of Rome had but the one neck!’ And on another, when they called out for the brigand Tetrinius he described them all as Tetriniuses.

There was the time too when a group of five net-and-trident men, pitted against five sword-and-shield gladiators, gave up without a fight, but when Caligula sentenced them to death, one of them snatched his trident and killed all the victors in turn. Caligula then issued a public proclamation bewailing this ‘bloodiest of murders’ and execrated those who had been able to endure the sight.

Book Four: XXXI His Desire for Disasters

Caligula openly deplored the state of his times, which had been devoid of public disasters. He used to say that Augustus’s reign was famous for the massacre of Varus and his legions, that of Tiberius for the collapse of the amphitheatre at Fidenae, while his own reign was so fortunate it would be forgotten totally, and he often longed for the loss of an army, a famine, plague, fire, or a large earthquake.

Book Four: XXXII His More Casual Cruelties

His words and actions were just as cruel when he was relaxing, amusing himself or feasting.

Trials by torture were often carried out in his presence, even while he was eating or playing, an expert headsman being retained to decapitate prisoners.

When his bridge at Puteoli (Pozzuoli), which I mentioned, was being dedicated, he invited a number of people to cross to him from the shore then had them thrown, suddenly, into the sea, those who tried to cling onto the rudders of the boats being thrust back with boathooks and oars.

There was a public banquet of his in Rome where a slave was promptly handed over to the executioners for stealing some silver-strip from a couch, his hands to be cut off and hung round his neck, after which he was to be led among the guests preceded by a placard describing his crime.

On another occasion, he was fighting a duel with a swordsman from the gladiatorial school, using wooden blades, when his opponent engineered a deliberate fall. At once Caligula ran up and stabbed him with a real dagger, then danced about waving a palm-branch, as victors do.

Again, he was once acting as assistant-priest at a sacrifice, and swung the mallet high as if to fell the victim, but killed the priest holding the knife instead. And at a particularly sumptuous banquet, he suddenly burst into peals of laughter, and when the consuls reclining next to him politely asked the reason, he answered: ‘Only that if I were to give a single nod both your throats would be cut here and now.’

Book Four: XXXIII His Cynical Humour

Among other cynical jests, he was once standing with the tragic actor Apelles beside a statue of Jupiter and asked him whether the emperor or the god seemed the greater. When Apelles hesitated, Caligula ordered him whipped, extolling the music qualities of his voice from time to time, as the groaning actor begged for mercy.

And as he kissed the neck of wife or sweetheart, he never failed to say: ‘This lovely thing will be slit whenever I say.’ Now and then he even threatened his dear Caesonia with torture, if that was the only way of discovering why he was so enamoured of her.

Book Four: XXXIV His Hatred of Famous Men

He attacked men of every period, with as much malicious envy as savage intolerance, toppling the statues of the famous in the Campus Martius, which Augustus had once moved there to clear space in the Capitol courtyard. Caligula had them shattered so that neither they nor their inscriptions could be restored. He refused to allow the setting up of any further statues of living men without his knowledge and consent.

He even considered destroying all copies of Homer’s works, questioning why he should not exert Plato’s privilege of banning the poet from the state he had envisaged. And he came near moreover to removing the works and busts of Virgil and Livy from all libraries, denigrating Virgil as a man of no talent and little learning, and Livy as a verbose and slipshod historian.

As for lawyers, whose profession he seemed to have every intention of dispensing with, he often threatened to see that none of them, by Hercules, should ever again give advice contrary to his wishes.

Book Four: XXXV His Envy of Others

Out of envy, Caligula deprived the noblest Romans of their historic family emblems. Torquatus was robbed of his collar; Cincinnatus was stripped of his lock of hair; while Gnaeus Pompeius lost the surname ‘Magnus’ belonging to his ancient House.

After extending an invitation to Ptolemy of Mauretania to visit him in Rome, and greeting him with honour, Caligula suddenly ordered his execution, as I have said; simply because, at a gladiatorial show, he resented the adulation Ptolemy received on entering in a splendid purple cloak. And whenever he came across handsome individuals with fine heads of hair, he had the backs of their heads closely shaved to imitate his own baldness.

A certain Aesius Proculus, son of a leading centurion, was so well-built and handsome he was nicknamed Colosseros (‘Mighty Eros’). Caligula had him plucked from his seat in the amphitheatre one day, and dragged into the arena, where he pitted him against two heavily-armed gladiators in succession. When Proculus managed to win both contests, Caligula had him dressed in rags, tightly bound, and led through the streets without delay, to be jeered at by the women, and then put to death.

In short, it seems there was none so poor or low but Caligula could find something in him to envy.

Because the Sacred King at Nemi had held his priesthood for a long stretch of years, he sent a stronger slave to challenge him.

And when a chariot-fighter called Porius drew massive applause during the Games for freeing his slave to mark a victory, Caligula rushed from the amphitheatre in such indignant haste that he trod on the fringe of his robe and fell headlong down the steps. He rose, shouting in rage that this race that ruled the world honoured a gladiator more for a trivial gesture than all their deified emperors, or the one still there among them.

Book Four: XXXVI His Sexual Immorality

Caligula had scant regard for chastity himself, nor respected that of others. He was accused of exchanging sexual favours with Marcus Lepidus, with Mnester the comic actor, and with various foreign hostages. And a young man of consular family, one Valerius Catullus, boasted publicly of having had the emperor, and that he had worn himself out in the process.

Besides his incest with his sisters and his notorious passion for the concubine Pyrallis, there was scarcely a woman of rank in Rome who did not receive his attentions. He would invite a number of them to dinner with their husbands, and would then have them pass by the foot of his couch while he inspected them slowly and deliberately, as if he were at a slave-auction, even stretching out his hand and lifting the chin of any woman who kept her eyes modestly cast down. Then, whenever he fancied, he would leave the room, send for the one who best pleased him, and returning a little later, flushed with his recent activity, he would openly criticise or commend his partner, enumerating her good and bad points, physically, and commending or otherwise her performance. There were those too, to whom he sent bills of divorce, registering the documents publicly in the names of their absent husbands.

Book Four: XXXVII His Extravagance

His ingenuity for reckless extravagance exceeded all the spendthrifts of the past. He would bathe in perfumed oils, hot or cold, for a novelty; drink costly pearls dissolved in vinegar; and serve up unnatural feasts, with gold used in preparing the bread and meat, asserting that one should either be frugal or be Caesar. And for several days in succession, he scattered a small fortune in coins from the roof of the Julian Basilica, for the public to gather.

He built Liburnian galleys, but instead of the usual one or two banks of oars these had ten, with gem-studded sterns, multi-coloured sails, vast roomy baths, whole colonnades and banqueting halls, plus a wide variety of vines and fruit-trees. In these ships he would take early-morning cruises along the Campanian coast, reclining at table among dancers and musicians.

He had villas and country-houses built regardless of expense, delighting above all in achieving the seemingly impossible. For that reason too he had moles built out into deep and stormy waters, tunnels drilled through the hardest rocks, flat ground raised to mountain height and mountains levelled to plains, and all at breakneck speed, with death the punishment for delay.

Suffice it to say, that in less than a year he squandered a vast amount, including the twenty-seven million gold pieces amassed by Tiberius.

Book Four: XXXVIII His Plunder and Extortion

Having impoverished himself in this way, he was forced to turn his attention to extortion through a complex and cleverly designed combination of false rulings, auctions and taxes.

Firstly, he decreed that to claim Roman citizenship, where that status had been obtained by an individual ‘for themselves and their descendents’, then ‘descendents’ was to be interpreted as ‘sons’, and that a remoter degree of kinship was not legally acceptable.

Then, when presented with diplomas (diplomata, signifying honourable discharge from service, and entitling the holder to special privileges) issued by the deified Julius and Augustus, Caligula simply waved them aside as out-of-date and invalid.

Further, he impounded estates where any addition to the estate had been made since the census, claiming that the original census return must have been false.

If any leading centurion since the start of Tiberius’s reign had not named the emperor as an heir, he voided their wills on the grounds of ingratitude, and did likewise with those of any other individuals who had said they intended to, but had not in fact done so. When he had roused such fear by this, that even those who were not close to him told children and friends they had made him their sole heir, he then accused them of mocking him by stubbornly staying alive after doing so, and sent many of them poisoned sweetmeats.

Caligula conducted trials of those charged, in person, declaring in advance the sum of money he intended to garner during the sitting, and not ending it till he had done so. The slightest delay irritated him, and he once condemned more than forty defendants, charged on various accounts, in a single judgement, boasting to Caesonia, when she woke from a nap, that he had resolved a heap of business while she was sleeping.

He would auction whatever properties were left over from his entertainments, himself driving the bidding to such heights, that some who were forced to make ruinous bids at exorbitant prices committed suicide by opening their veins. On one notorious occasion, Aponius Saturninus fell asleep on a bench, and Caligula warned the auctioneer not to ignore the repeated nods of the said praetorian gentleman, who before the bidding was ended found himself the unwitting owner of thirteen gladiators at a price of ninety thousand gold pieces.

Book Four: XXXIX His Auctions in Gaul

When he was in Gaul, he sold his condemned sisters’ jewels, furniture, slaves, and even freedmen there, at such high prices that he decided a similarly profitable venture would be to auction the contents of the Old Palace, and so he sent for them from Rome, commandeering public carriages and even draught animals from the bakeries for the purpose, causing disruption to bread supplies in the City, and the loss of many lawsuits where the litigants were unable to find transport to the courts, and so failed to appear to meet their bail. At the auction which followed, he resorted to every kind of trick and enticement, scolding bidders for their avarice, or their shamelessness in being richer than he was, while pretending sorrow at allowing commoners to buy the property of princes.

Learning that a rich provincial had paid a bribe of two thousand gold pieces to the officials who sent out the Imperial invitations, so as to be added to the list of guests at his dinner-party, Caligula was not in the least displeased, the honour of dining with him having been rated so highly, and when the man appeared at the auction next day, Caligula sent an official over to demand another two thousand in gold for some trifling object, along with a personal invitation to dinner from Caesar himself.

Book Four: XL His New Methods of Taxation

He levied new and unprecedented taxes, at first through tax-collectors, and then, because the amounts were so vast, through the centurions and tribunes of the Praetorian Guard. No group of commodities or individuals escaped a levy of some kind. He imposed a fixed and specific tax on all foodstuffs; and a charge of two and a half per cent on the value of any lawsuit or legal transaction, with a penalty for anyone found to have settled out of court or abandoned a case. Porters were required to hand over twelve and a half per cent of their daily wage, while prostitutes were docked their average fee for a client, this latter tax being extended to cover ex-prostitutes and pimps, and even marriage was not exempt.

Book Four: XLI His Other Nefarious Methods of Raising Money

Many offences were committed in ignorance of the law, since the new taxes were decreed but nothing was published to the public. After urgent representations, Caligula finally had a notice posted, in an awkward spot in tiny letters to make it hard to copy.

To cover every angle for raising money, he even set apart a number of palace rooms as a brothel, and furnished them in style, where married women and freeborn youths were on show. Then he sent pages round the squares and public halls, advertising the place to men of all ages. Its patrons were offered loans at interest, and were registered as contributors to Caesar’s revenues.

He was even happy to profit from playing dice, swelling his winnings by cheating and lying. Once, having given up his place to the man behind him and strolled off into the courtyard, he spotted two rich knights passing by, ordered them arrested and their property confiscated, and returned, exultant, boasting that his luck had never been better.

Book Four: XLII His Daughter’s Dowry

When his daughter, Julia Drusilla, was born, he had a further pretext for his complaints of poverty, his expenses as a father not merely a ruler, and so he took up a collection for her maintenance and dowry.

He also proclaimed that New Year’s gifts would be welcome, and sat in the Palace entrance on the first of January, grasping handfuls and pocketfuls of coins that people of every rank showered on him.

Ultimately he was driven by a passion for the very touch and feel of money, and would trample barefoot over great heaps of gold pieces poured on the ground, or lie down and roll in them.

Book Four: XLIII His Expedition to Germany

He only experienced war and the business of arms on a single occasion, and that was the result of a sudden impulse. On visiting the sacred grove of the River Clitumnus (Clitunno) near Mevania (Bevagna), he was warned to supplement the numbers of his Batavian bodyguard, which gave the impetus to a German expedition (to the mouths of the Rhine). He promptly gathered legions and auxiliaries from every quarter, held strict levies everywhere, and collected supplies on an unprecedented scale. Then he set out on a march, which was so swift and immediate that the Praetorian Guards were forced to break with tradition, lash their standards to pack mules, and follow. Yet sometimes he was so lazy and self-indulgent that he travelled in a litter carried by eight bearers, and insisted that the inhabitants of towns he passed through swept the roads and sprinkled them to lay the dust.

Book Four: XLIV The Surrender of a British Prince

On reaching his headquarters, Caligula decided to show his keenness and severity as a commander by dismissing ignominiously any general who was late in gathering his auxiliaries from wherever. He then reviewed the troops and downgraded many leading centurions, on the grounds of age and infirmity, though they had years of service, and in some instances only days left to complete their term, He upbraided the rest for their avarice, before halving their bonus on discharge to sixty gold pieces each.

His only achievement in this campaign was to receive the surrender of Adminius, the son of Cunobelinus, a British king. Adminius had been banished by his father and had deserted to the Romans with a few followers. Nevertheless Caligula composed a grandiloquent despatch to the Senate, written as if all Britain had surrendered to him, ordering the couriers not to halt their carriage, regardless of their hour of arrival, but to drive straight to the Forum and Senate House, and hand it to no one but the Consuls, in the Temple of Mars the Avenger, in front of the entire Senate.

Book Four: XLV Mock Warfare

Finding no ready opportunity for battle, Caligula had a few German guardsmen sent over the Rhine, with orders to hide. Word was then brought, after lunch, with a deal of drama and excitement that the enemy were nearby. He at once galloped into the neighbouring woods with his staff, and a contingent of the Horse Guards, where they cut branches and trimmed them as trophies, then rode back by torchlight, taunting as idle cowards those who had not been of the party. He thereupon decorated his comrades in arms, with a new kind of chaplet, adorned with images of the sun, moon and stars, which he named the Rangers’ Crown.

On another day he took hostages from a school for grammarians and sent them on ahead of him in secret. Then he suddenly abandoned his banquet and chased them with the cavalry as if they were fugitives, ‘capturing’ them once more, and herding them back in chains, in a similar wild show of extravagant nonsense. When the officers were assembled and he was ready to return to the table, he urged them to take their seats as they were, in their coats of mail, and exhorted them in Virgil’s famous words to: ‘Endure, my friends, and preserve yourselves for happier days!’

Meanwhile he despatched a rebuke to the Senate and the Roman people, reprimanding them most severely by edict for indulging themselves in feasts, and idling their time away at the theatre or in pleasant country retreats while Caesar was exposed to all the dangers of war.

Book Four: XLVI Victory Over the Sea

Finally, as though bringing the campaign to a close, he lined up the army in battle array, with its catapults and other artillery facing the Channel. The soldiers were standing there, with not the least clue as to his intentions, when he ordered them, suddenly, to start collecting sea-shells, and fill their helmets and the folds of their tunics with what he called ‘the ocean’s spoils, that belong to the Capitol and the Palace.’

As a memorial of this great victory, he had a tall lighthouse built, like the Pharos at Alexandria, to provide a point of reference for ships at night. Then he promised the soldiers a bounty of four gold pieces each, as if it were an act of unprecedented generosity, saying: ‘Go in happiness, go with riches.’

Book Four: XLVII Preparations for a Triumph

He was now free to turn his attention to planning a triumph.

He chose the tallest of his Gauls, and various chieftains, with others he considered ‘worthy of a triumph’, to supplement the few genuine captives and deserters from native tribes in the Roman camp. He reserved all these for his triumphal procession, making them grow their hair long and dye it red, as well as learning German and adopting German names.

Meanwhile he sent his ocean-going triremes on to Rome, having them carted overland for much of the journey, and wrote to his financiers telling them to organise a triumph on a grander scale than ever before, but at the lowest possible cost to himself since everyone’s property was at their disposal.

Book Four: XLVIII An Attempt Against the Legions

Before quitting Gaul, he plotted a cruel act of revenge, planning to massacre the soldiers in those legions which had mutinied years before, after the death of Augustus, because they had laid siege to his father Germanicus’s quarters, while he was there too, a young child. He was with difficulty persuaded to relent of this madness, but only inasmuch as he schemed instead to decimate their ranks. He therefore ordered them to parade without their arms, including their swords, and flanked them with armed cavalry. But a number of the legionaries, scenting trouble, stole away quietly to fetch their weapons, in case of attack, and realising this Caligula fled the camp in haste and headed for Rome. To distract attention from his own dishonourable behaviour he savaged the Senate, openly threatening the Senators. Amongst other complaints, he claimed to have been cheated of a well-earned triumph, though shortly before he had ordered them to do nothing to honour him, on pain of death.

Book Four: XLIX His Intentions Towards the Senate

When met on the way by a group of distinguished Senators begging him to return immediately, he struck repeatedly at the hilt of his sword and shouted: ‘I will, and this will be coming with me! Then he issued a proclamation announcing his return but only to those who wanted him back, the knights and the people, since he would never consider himself the Senators fellow-citizen or emperor again. And he refused to allow the Senate to welcome him. Having relinquished or at least postponed his triumph, he entered the City on his birthday (31st August 40AD) and received an ovation.

Within five months he was dead, having committed great crimes in the meantime, and contemplated even worse ones, for example he intended to slaughter the leading senators and knights, and govern first from Antium and then Alexandria. The proof is conclusive, since two notebooks were found among his private papers, one labelled ‘Sword’ and the other ‘Dagger’, listing the names and details of those he had marked out for death. A large chest containing various poisonous materials was also found, which they say Claudius disposed of in the sea, the contents killing shoals of fish, which littered the neighbouring beaches.

Book Four: L His Appearance and Health

Caligula was tall and very pallid, with an ill-formed body, and extremely thin neck and legs. His eyes and temples were sunken, his forehead broad and forbidding, and his hair thin, and absent on top, though his body was hairy. Because of his baldness it was a capital offence to view him from above, or because of his hairiness to mention goats in any context. His face was naturally grim and unpleasant, but he deliberately made himself appear more uncouth by practising a whole range of fearsome and terrifying expressions in front of the mirror.

He was unsound in body and mind. As a boy he suffered from epilepsy, and though he seemed tough enough as a youth, there were times when he could barely stand because of faintness let alone walk, or gather his wits, or even raise his head. He was well aware of his mental illness, and sometimes thought of retiring from Rome to clear his brain. Some think that Caesonia his wife administered a love potion that had instead the effect of driving him mad.

He was especially prone to insomnia, and never achieved more than three hours sleep a night, and even then his rest was disturbed by strange visions, among other nightmarish apparitions once dreaming that the spirit of the Ocean spoke to him. Bored by lying awake for the greater part of the night, he would sit upright on his couch, or wander through the endless colonnades, longing for daylight and often calling out for it to come.

Book Four: LI His Over-Confidence and Fears

I think I can rightly attribute to his mental infirmity two contrasting faults in his personality, on the one hand excessive over-confidence, and on the other extreme fearfulness. Here was a man who despised the gods utterly, but at the slightest approach of thunder and lightning would shut his eyes tight, muffle his hearing, and if the storm came nearer would leap from his bed and hide beneath it.

In Sicily he mocked the miracles supposedly witnessed in various places, but fled Messana (Messina) at night, terrified by the roar from Aetna’s (Etna) smoking crater.

And despite a spate of threats against the barbarians, a comment from a member of his staff, as they were riding through a narrow gorge in a chariot, that there would be no end of panic if the enemy should appear, caused him to mount a horse there and then and gallop back to the Rhine. Finding the bridges blocked by servants and baggage, he had himself passed from hand to hand over the men’s heads in his impatience.

Not long afterwards, hearing of a new uprising in Germany, he readied his fleet to flee the region, comforting himself with the thought of the provinces overseas which would still be his, even if the enemy conquered and took possession of the Alpine passes, as the Cimbri had once done, or even of Rome as had the Senones.

It was this trait of his, I think, that later gave his assassins the idea of deceiving the angry guards with the tale that rumours of a defeat had led him to commit suicide in terror.

Book Four: LII His Mode of Dress

Caligula ignored Roman fashion and tradition in clothing, shoes and other elements of dress, even wearing female costumes and imitating the attire of the gods. He often wore cloaks embroidered with precious stones in public, with long-sleeved tunics and bracelets, sometimes dressing in the silken robes only permitted to women. His footwear might be slippers, or platform-soles, or military boots, such as those worn by his bodyguard, or women’s sandals.

Then again, he would often appear with a golden beard, grasping a lightning-bolt, a trident, or a caduceus, as an emblem of the god, or robed as Venus. And even before his campaign, he frequently wore triumphal dress, sometimes donning Alexander the Great’s breastplate which he had stolen from the sarcophagus (at Alexandria).

Book Four: LIII His Oratory

Regarding liberal studies, Caligula gave little attention to literature but much to rhetoric, and was as ready and eloquent as you please, especially when prosecuting anyone. When angered, his words and thoughts flowed spontaneously, he moved about excitedly and his voice carried a great distance.

When beginning a speech, he would warn that he was about ‘to draw the sword forged by the light of his midnight lamp’, but despised the polished and elegant style so fashionable at that time, saying that the popular Seneca composed ‘from a text-book’ and was ‘mere sand without lime.’

He would also pen rebuttals of orators’ successful pleas, or compose speeches both for and against important defendants in Senate trials, the facility or otherwise of his pen determining which speech decided the outcome, whether ruin or acquittal, and would invite the knights, by proclamation, to attend and listen.

Book Four: LIV His Gladiatorial and Theatrical Skills

He was an enthusiastic devotee of a wide variety of arts and skills, making appearances as a heavily-armed gladiator fighting with real weapons, a charioteer in a number of different arenas, or even as a singer and dancer. He was so enraptured by his delight in song and dance that, at public performances, he could not help chanting along with the tragic actor as he delivered his lines, or freely mimicking his gestures, by way of praise or correction.

Indeed, on the very day of his death, it seems, he commanded an all-night performance in order to take advantage of the licence it allowed, and make his first stage appearance. He even danced at night on occasions, and once summoned three senators of consular rank to the Palace at midnight, seating them on a platform when they arrived half-dead with fear, then suddenly bursting forth, clad in a cloak and an ankle-length tunic, in a clatter of clogs, to the din of flutes, danced and sang, and vanished again.

Though with all these varied skills, he still couldn’t swim a stroke.

Book Four: LV His Favourites

His partiality towards those he loved bordered on madness. He would kiss Mnester, the comic actor, even in the theatre, and if anyone made a noise while his favourite was dancing, he had that person dragged from their seat and beat them with his own hands. Once, when a knight created just such a disturbance, he was commanded, via a centurion, to set off for Ostia without delay, and carry a message to King Ptolemy in Mauretania. The message when opened by Ptolemy read: ‘Do nothing to this man, either good or bad.’

He gave some swordsmen among the gladiators, whom he liked, command of his German bodyguard, but reduced the protective armour of those he did not. When one of the latter, Columbus, won a contest, he had the slight wound he had suffered rubbed with poisonous salve, which he dubbed columbinum, at least that was one of the names in his list of poisons.

He was such a devotee of the Green faction (the others were the Reds, Whites, and Blues) that he frequently dined in their quarters and spent the night there, and once after carousing with the charioteer Eutychus gave him twenty thousand gold pieces worth of gifts.

He would send out soldiers the day before the Games to order the neighbourhood to be silent, so that his horse Incitatus (Swift) was not disturbed by noise. This horse had a marble stall and ivory manger, blankets of royal purple and a gemstone collar, with his own house and furniture, and a full complement of slaves, to provide a fitting environment for guests who were invited to the Games in his name, and they even say that Caligula planned to make him Consul.

Book Four: LVI The Conspiracies Against Him

Caligula’s wild and vicious behaviour prompted various conspiracies against his life. After a couple of these plots had been detected, while those still harbouring such thoughts awaited the right opportunity, two men joined forces and put an end to him, thanks to the help of his most powerful freedmen and the Guards commanders. The latter had been accused of involvement in one of the conspiracies which had been detected. The charge was false, but Caligula hated and feared them none the less. In fact he had exposed them to public odium by calling them out, and declaring, sword in hand, that he would do the deed himself if they thought he deserved death, and had never ceased denouncing them to each other, from that moment on, and creating dissent between them.

Finally, they decided to kill him at the Palatine Games, as he left for lunch, at midday. A tribune of one cohort of the Praetorian Guard, Cassius Chaerea, a man well on in years, claimed the principal part, because Caligula persistently taunted him, with being weak and effeminate, insulting him in a variety of ways. When Cassius asked for the password Caligula would reply ‘Priapus’ or ‘Venus’, and when Cassius thanked him for anything he would hold out his hand to kiss, and waggle the fingers obscenely.

Book Four: LVII Portents of His Assassination

There were numerous portents of Caligula’s imminent murder.

The statue of Jupiter (Zeus) at Olympia, which he had ordered to be disassembled and transported to Rome, uttered such a peal of laughter that the scaffolding collapsed, and the workmen ran for their lives. Immediately afterwards a man named Cassius appeared, saying that he had been ordered in a dream to sacrifice a bull to Jupiter.

The Capitol at Capua was struck by lightning on the Ides of March, as was the doorkeeper’s lodge of the Palace at Rome, some taking the former to mean another assassination of the kind that had occurred before on that very same day (that of Caesar), and the latter to mean that danger threatened the owner at the hands of his own guards. And when Caligula consulted the soothsayer, Sulla, about his horoscope, he too declared that death was imminent.

The Oracle of Fortune at Antium likewise warned him to beware of Cassius, so he ordered the death of Lucius Cassius Longinus, the proconsul of Asia, neglecting the fact that Chaerea’s family name was also Cassius.

The day before he was killed, he dreamt he stood beside Jupiter’s throne in heaven, and that the god sent him tumbling to earth with a blow from the toe of his right foot. And other things that happened on the morning of his death were later seen as portents. As he was sacrificing a flamingo he was splashed with its blood. Mnester the actor danced a tragedy (Cinyras) which Neoptolemus had performed years before during the Games where Philip of Macedon was assassinated. And in a farce entitled Laureolus the Highwayman, at the close of which the lead actor had to die while trying to escape, and appear to vomit blood, the understudies were so keen to show their talents that in their imitation of him they covered the stage with gore. Finally, a nocturnal performance also was in rehearsal, set in the Underworld, and acted by Egyptians and Ethiopians.

Book Four: LVIII His Death

On the 24th of January, just after midday, Caligula was deciding whether or not to rise and take lunch, since his stomach was still out of order after a heavy banquet the previous day. Eventually his friends persuaded him to do so. In the covered way outside, some boys of noble family who had been summoned from Asia Minor to appear on stage were practising their parts, and he stopped to watch and encourage them, and would have returned and ordered their performance to begin if the leader of the troop had not complained of a chill.

There are two versions of what happened next. Some say that while he was talking to the boys Cassius Chaerea approached him from behind, and crying ‘Do it!’ gave him a deep wound in the neck, which was the cue for Cornelius Sabinus, the tribune, his co-conspirator, who was facing Caligula, to stab him in the chest. Other say that Sabinus told the centurions in the plot to clear the crowd, and asked for the password as soldiers do, and that when Caligula replied ‘Jupiter’ Chaerea shouted from behind him ‘Receive his gift!’ and split Caligula’s jawbone as he turned, with a blow from his sword.