Meditations on the Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri

Inferno Cantos I-VII

A. S. Kline Authored by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2002, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Introduction

- Meditation I: Inferno Canto I

- Meditation II: Inferno Canto II

- Meditation III: Inferno Canto III

- Meditation IV: Inferno Canto IV

- Meditation V: Inferno Canto V

- Meditation VI: Inferno Canto VI

- Meditation VII: Inferno Canto VII

Introduction

Who is Dante? Has he been read? Has he been understood? I want to talk about him and his work primarily as a poet speaking about a poet. I do not want to approach him primarily from the viewpoint of religion, or history, as Dante the moralist, or Dante the political exile. I want to approach him through the word and the life. His life, his religion, his politics, his role as re-vivifier and transmuter of the classical world, as architect of a visionary construct, the story of his love for Beatrice, these are threads which wound into this man’s reality until he became the archetypal lover, writer, man of destiny. All that both makes his greatness as a poet and is secondary to it. His content is poetic in the extreme, it is language heightened to grasp and control those threads and wind them tight.

How to distinguish his essential importance? An isolated, solitary, intense and visionary extremist takes the stage. Individuality, placing itself in its time within the world, weaves a tapestry of elements, to illuminate its own unquenchable desires, for love, for beauty and for truth. What happens here in the Divine Comedy happens in Dante’s mind, at a moment in history. Do not all the heavens and all the realities of time and space circle around him, around the single man? He does not look back into the distant past, he draws from it to illuminate the present. He writes not an epic, but a novel. An Odyssey and not an Iliad or an Aeneid. Odysseus is there too, restless, in the Inferno, inside a burning flame. Dante takes the archetypal motif of the journey, the travels of the hero, only he is an anti-hero, humbling himself, a lover, a pupil, a child with its guides, a sinner, and the object of that journey is illuminated by the events of his own life, so that the journey is above all contemporary and personal. Odysseus’s journey is not Homer’s, Aeneas’s is not Virgil’s, but Dante’s journey is above all his. The individual, that essential heart of Christianity, steps out, burdened with its own past, a lover still weeping the loss of his beloved, dedicated, as the last pages of the Vita Nuova tell, to an act of homage to her which took a lifetime, a poet still learning how to write, an apprentice walking beside his masters, borrowing from them and speaking to them, a live poet among the dead, making them live again, a sinner, a child at fault being shown the essence of how to live and how to succeed in living, and being guided to the heights of vision of what is. Lover, Poet, Sinner. And then into his tapestry he weaves the Classical and Medieval worlds, the one as myth, legend, history and political formula, the other as example, theatre, power play, and political aspiration. Anguished and angered he strikes at his enemies, defends his ideals, refuses to cheat, to be other than he is, sometimes inept, ignorant, awkward, often proud, confessing to sins of lust, but also convinced of the rightness of the vision, its externalised symbolic meaning, its rational and emotional validity.

Dante is an outsider, an exile. His emotional intensity sets him off from others, makes him poet, lover, and sinner. He inhabits a ‘party of one’, wanting to purify the Church on the one hand, and purify the Empire on the other. A reformer without true power, a difficult and an extraordinary man. But not a revolutionary, a visionary. It is the word he turns to, not violence or intrigue. His inner zeal, his need to make both goddess and unattainable ideal out of Beatrice, and with her out of Intellect, out of Knowledge, out of Truth, his desire, his urgent desire all his life, to make Beauty and Truth and Love one, place him already outside the norm. And his own passion and mission, his own need for personal solace, acceptance and redemption, is extended outwards to his society. What is needed for him, right for him, must be needed and right for his whole society, for all men, for all time. He humbles himself to humble his world, he purifies himself to purify his world. Pride and Lust must become Humility and Innocence, Understanding and Light. Beatrice, Beauty, must also be divine philosophy and perfect spiritual love. Knowledge and Aesthetics and Relatedness must come together in a knot of light that illuminates the whole universe in its flow outwards and downwards, and its reflection backwards and upwards.

He is the outsider, the exile who takes it upon himself to interpret the orthodoxies, to reincarnate the Classical and Christian past, to reinterpret his own life and that of his contemporaries, and to do so in a vision, in a dream, in a symbolic journey. Did he believe in the reality of what he saw in his vision? Yes and no. Yes, he believed in the emotional and spiritual truth of what he saw, the values incarnated there, the morality and theology reflected there, the positioning of historical events and personalities within those value constructs. No, he did not believe in the precise material reality of what he knew to be his own construct, a poem, and edifice of words. He himself speaks often of its dream nature, its visionary form, and yet it is also memory, which he cannot easily recall, it is psychological reality. He had been there: he had, in creating it. He had lived its possibility, and hovered on the border between the creation that is never truth, and yet by being created becomes truth, becomes a part of the life. Is memory truth? Is memory real? We re-create events and places, faces and voices in our minds. Are they real? In what sense are they real? Dante is in this region of reality, between and among the realities of meaning and feeling, on the edge of what is externally real, at its extreme boundaries, where what is outside melts into what is inside and becomes one with it. The journey is symbolic, but it is not fantastic. It is a search for truth, beauty and love, through memories of reality, historical and contemporary, set back slightly in the poet’s past to distance it, yet launched at the future, his own future that went on beyond the last canto, and involved his own purgation to come, his own triumph (?) over pride and lust, his own re-visiting of the symbolic Mount yet to come, and launched at us, at posterity, at that fame he knew would be his, proud in his humility, offering his humility to help ensure his fame.

The journey enshrines values: therefore it is no mere story, no mere epic tale. What is Homer’s view of his material? Or Ovid’s? Virgil on the other hand is the perfect guide, not merely because Virgil enshrined, in the Aeneid, a usable store of poetic techniques and scenes, (particularly the Underworld visit of Book VI), and an Empire, a political reality, still ideal in Dante’s mind, not merely because he is the dead, older, morally virtuous, pagan, poet, and poetic historian, but because Virgil himself wrote a great poem with an objective, a political and moral objective, and intended it to reflect the Romans to the Romans in a mirror. Virgil was a poet like Dante with a mission, not a Homer, a great poetic storyteller and upholder of accepted values, not an Ovid, a poet par excellence weaving enchantment and laughter for its own sake, the one a poet of truth and beauty, the other a poet of beauty and love, both sometimes moralists, but in Virgil’s case a moralist and creator using beauty and truth and emotional realities to serve the goal, to achieve an end. I think Dante goes beyond Virgil precisely because Love and Beauty were as vital to him as Truth, but it was Truth, and moral truth, above all he sought to serve, believing that Love and Beauty were part of that Truth.

Dante uses everything he knows to convince us and himself of the concrete possibility of his construct. He is an artificer extreme, knowing, and sensitive to knowledge, as only an exile, an outsider, can be. Like Ovid, even more so than Virgil, he raids his own time and history for examples, he delights in showing off his learning and understanding, because it fuels his pride and his poetry yes, but also because it serves his end, which is Keats’ ‘willing suspension of disbelief’. The agenda is the moral content, the message is the values that he seeks to communicate, the rest beautiful, complex, brilliant is the means. Dante without moral content is as meaningless as Virgil, only a good story well told. Homer, Ovid have a moral intent, yes, but it is quiet, secondary, a facet of the good life, well lived, obvious and humanist. Virgil and Dante have a deeper aim, to enshrine their own morality in the political reality, in the wider world. Virgil to convince Augustus and his peers. Dante to convince his age and posterity.

So Dante walks through history, of the world, of his own times and of his own life, and points that history, as he walks and climbs and soars, at his world and at us, the future. The Mount is a missile aimed. Hell is its reverse in the mirror of the underworld. Paradise is what it is aimed at. Purgatory is a rocket ship, fuelled by the matter of the Inferno, aimed at the stars. The examples, the punishments, the inverted cone of moral failure of the Inferno, is sucked up into the Mountain, transmuted into energy, and fired upwards.

Space which is inwards, contained, a prison, in the Inferno, is reversed outwards, and liberated in the Purgatorio, to allow a progression towards the Good, towards Moral Truth, and a vision of its fulfilment in the Paradiso. Time which is endless in the Inferno, a pattern of eternal recurrence, eternal penalty, hopelessness, unremitting doom, in that place where there is no way back and no way forward, marked out as passing by the downward journey under the receding sky, becomes a forward movement in the Purgatorio, where hope creates the possibility of an end to purgatory and purgation, to self-torment, an end to time, and in the Paradiso earthly time is suspended as Dante circles with the zodiac, and gazes towards the timeless realms of the Infinite.

Dante is a mask, it is time to humanise him. Dante is relevant beyond his age, it is time to rescue him from theologians and historians. Dante is a poet, it is time to rescue him from scholarship. He has more to say than most to those who are not Christians, not theologians, not historians and not scholars, but who still as human beings search for moral understanding, and have love, truth and beauty as realities in their lives. The language of the Inferno, its babble, its gutturals, its verbal quivering and snapping, its physical concreteness, becomes the language of the Purgatorio, human, gentle, sweetened, softened, singing, and then melts into love, light and the smile of Paradise. Is that not felt by our world? Do we not understand the deathliness of the discourse of violence, and darkness, its babbling rhetoric, its voices of hatred, anger, pain, lust? Do we not try in our own lives to bring about a human world of solace, and compassion, of relationship and tolerance, of purgation and ascent? Do we not long for paradise? A human paradise, of love, truth and beauty? And do we not care about the language, the life of the word, in which love, truth and beauty can be invoked? Do we not want the song-less Inferno, the world of cries, groans and wails, to become the singing Purgatorio, where the harmony of the race might outweigh its disharmonies? Do we not want all singing to become the wordless, ineffable music of the spheres?

In Dante, with medieval economy and directness, all the worlds are contemporary. There is no feeling of the thousand years between himself and Virgil, that lapse of Empire he seeks to abolish. He picks up where Virgil leaves off in Book IV of the Aeneid. Virgil already offers him the Golden Bough, Beatrice the path forward, one will conduct him downwards, a historical Sybil, then upwards, the other will conduct him onwards, a contemporary Muse, but ah, so much more than a Muse. From these ever-contemporary timeless worlds of art and love Dante will send us signals, show us signs, exhibit his points of reference for us, educate us, and ask us about our education, as he piles example upon argument and declaration, not to debate with us, here there is no debate, but to reveal to us, here all is revelation. Christianity declares itself here in its parameters, its rootedness in time, in a moment of time, in history, and Roman history: its celebration of the individual and the life story of the individual, from birth to redemption, from recognition to freedom: its revelatory nature, solidifying into orthodoxy, grounded on words in the Testaments, glorifying the primal Word: its evangelical fervour, its anti-heretical zeal, its appearance as news, its concern for interpretation of the present in terms of the historical past and that revelation. Even to the unbelievers among us, he sends moral signals, a vision of humanised beauty, individual worth and shared possibility, a structuring of experience into that which is destructive, rejected, submerged, defied, that which is accepted, recognised, learnt and acted upon, and that which comes from outside us, is given, and aspired to, that beauty of the world and time, of love and experience, that joy of love granted and shared, that comes to us as final vision and benediction. All those signals we ignore at our peril. Dante sounds all the notes of the flute that others played, and from whom our values have filtered. He does it in the name of Christianity, but he also does it in the name of Humanity and Poetry, of Love, Truth and Beauty.

Dante mirrored a thought process rooted in antiquity, as the Aeneid testifies, and developed by Christianity, in respect of the levels of experience, the gradations of reality whether emotional, spiritual or physical. There is in the mind a hell, a purgatory, a paradise. The echoes in the ancient world are endless, of underworld kingdoms or labyrinths, of the descent through the seven levels below, or beyond: of the places of cleansing and rebirth, the wells, the rivers, the sacred groves, the stone temples, the sacred spaces: and of the Edens, childhood, arcadia, the garden, the paradisial space-less and timeless experience. He echoed the spiritual structure of a belief, the aspirations of spires already stretching towards the sky, of towers. He made a spiritual architecture, and became the master-builder of a pit, a mount, and an ascent through space, all of which the mind and emotions know. We go down into the pit and labyrinth of ourselves, we emerge through the pain and sometimes the redemption of understanding and conception, we aspire towards the space and moment, the infinite space and timeless moment, of freedom. Freedom is the commandment to all things to flower, it’s denial to any living thing is its denial spiritually to all, and no freedom is a true freedom that takes away the freedom of other living entitities. So Dante’s un-free inhabitants of the nine circles of Hell destroy each other’s freedom, gnaw at each other’s present, and past, and future, push each other down, batter against each other, deny each other speech. His purgatorial aspirers know each other, declare each other, and urge each other on to freedom, the freedom of one being the possible freedom of all, so that the Mount shakes when a spirit is freed. Has that no relevance to our world, to our conflicts? And the true freedom of Paradise is everywhere a shared giving, an outpouring that enhances and reflects and swells and sounds and blazes out and glorifies, that increases and does not diminish by free flow, that is devoid of barter and transaction, and enshrines relationship and knowing. What is given is multiplied endlessly, and infinitely. What is taken is transformed and enhanced and repeated as in the image of the Three Graces, in their receiving, thanking and returning.

Down through the circles, up the spirals and levels of the Mount, out through the seven planetary spheres, the motion of the heart. There are endless echoes from pre-history and history of those journeys. Consider them in the stories of every people, and the constructs of every race. The outward or downward journey, to the place of understanding and truth, with the final return as one of the blessed. Turn that in the light, gaze at it in your hands, and it becomes Dante’s journey. He fulfils the motions of the ‘Hero With A Thousand Faces’: he even loses and forgets, as he returns, the experience of the full glory, and is left with the flower of paradise alone, in his hands, his Commedia. The spirit guides, the incidents, the examples all bring echoes of the primeval and ancient and classical journeys. But see how Dante’s journey is mediated through the word. He is not the hero who acts. He is not the lover, not the warrior, not the king, or redeemer, or saint. He is the human being, the individual man, and he travels to see and to learn and to interrogate and be interrogated. The Commedia is a verbal journey. Its protagonist is a Poet. Yes he is a lover and a moralist and a politician and a student of theology and philosophy and science and the arts, but primarily he finds his way through existence by the Word. Beatrice herself is here transformed from real woman, to spirit guide, to Divine Philosophy, to another participant in the final glory. She is metamorphosed, and moved from centre to circumference, so that she can make way for the Word. Is the poet asked to choose between the real woman and the Muse? Between reality and the Word? The true Poet knows how he will always choose, and hopes never to be forced to make the choice.

Dante travels in Vision, has dreams within the Dream, and ends his Commedia with an awakening without sequel. So that the great music swells and rises, and then ends on a long echoing note that goes on resounding within his life, the reader’s life, and within existence itself. He carries the senses with him. Are not the ear, the eye, the mouth, the nose, the touching tongue, all placed near to the brain, the mind, the spirit of a human being? All the senses become one, an ineffable music, a fragrance, a remembered taste, an image in a vision, a feeling of heat and light. The senses are dazzled, and the vision both dies back from mind into the word, from the word into the written text to be passed on written on stone into the future, containing the past, and ever open to the sensitive present. His imagery of the journey, his sailing boats, his moving flames and lights, his metric feet, reach a haven. That haven is only temporary, because the Commedia is a warning too, a sign to the sinner, a call through the dark wood, and it is a challenge to the reader’s or the listeners thoughts on the moral structure of existence, the meaning of love and beauty, the nature of truth. And are these not still intractable problems for us? We have inklings. We know that empathy, appreciation of beauty, love and knowledge exist. We handle them every day. But do we know what drives the mind to seek the good, the beautiful, the beloved, the true? And even if we fully understood the mechanics of our biology and history that create drives towards these things, don’t we still know that for the individual, for you and I, these things have a special status. We choose the empathetic and compassionate, loyalty and respect over their denials. We choose beauty from what is around us, yet we feel it chooses us. We choose love and yet we know we are chosen also. We find knowledge and in the end through a complex process accord it belief. Is it not still true that the good, the beautiful, the beloved and the true, are both within us and beyond us, both demand recognition and demand belief? If so then Dante’s call is to us, and is contemporary, and is beyond his own time. And his problems and agonies, his personal quest and his recognition of his beliefs are also ours, and still alive and demanding of us.

Dante’s Commedia is a place where experience is tested, through assay, through example, through observation, through interrogation, through memory and repetition, through recognition and acceptance. And from that grand revelation, that giant glass, Dante believes that truth which must encompass love, goodness and beauty will emerges to the reader’s eye. His Commedia is the gift of his belief.

I have touched on some of the themes. Progress with me now through the Cantos of the Commedia. Reference the indexes to and the text of the Divine Comedy as you go, through the hyper-linking. Let us, with Dante, bend over the text, while gazing outwards and inwards at the reality.

Meditation I: Inferno Canto I

MedI:1 The Individual: Inferno Canto I:1-60

Out of the Void the lone voice. The Individual, circumscribed lost and solitary steps onto the stage of world history. The wood is dark, it already has echoes of Piero delle Vigne and the wood of suicides of Inferno Canto XIII. The light falls on this single, anxious, troubled human being. The Poet himself. Here is no character from a play or hero from an epic. Here is the author, himself. And we have read the Vita Nuova. We have seen the prologue in the art and the life. Here is its sequel in the mind.

There have been works of biography written before, works of history, and works of spiritual journey, Augustine’s ‘Confessions’ is a great pre-cursor to this work. There too a sinner appears, and elements of biography, but not in the depth and intensity with which Dante weaves history, life and self into the Divine Comedy.

It is the end of the night before the dawn of Good Friday, when the annual and historical sacred drama begins, and glancing backwards over his shoulder at the reader, Dante begins his journey, not exactly a Pilgrim’s Progress, (does Dante actually progress fundamentally in the spiritual sense in this work?), but rather a Book of Revelation. The Light is falling through the leaves and the dark twisted branches, a single shaft onto the face of the distraught man. The wood is error and sin, material existence, the knotted and tangled, impenetrable reality of earthbound life, symbolised by the rooted intransigence that Sartre used in ‘Nausea’ to symbolise being here and not elsewhere, among things. That awareness, that coming to oneself, that recognition, of moral error in the self and the life, brings fear. Fear that this is all there is, and that there is no opportunity for change or progression.

And this is a dream, a vision, seen and now retold by the Individual. The Divine Comedy begins as it ends with this lone Individual recounting a dream and its ultimate departure. A vision he has seen. The I has seen. It is for the reader to judge its ‘truth’. Dante does not insist. Above him at the end of the valley in the vision there is already a gleam of light on the hills. But he has been standing at the brink of Hell, the ‘pass….that no living person ever left’. He is in the wasteland at the edge of the Inferno. Over the empty ground he begins to walk. He commences the rhythm of the moving feet, physical and poetic, mental and spiritual. He must walk to make this journey. There must be effort. The walking will indicate chosen direction, freely willed ascent or descent, ease or difficulty, speed or slowness. Here one walks. The exceptions will be interesting, when Dante is carried, drawn along, or moves without conscious will.

The sun’s position is fixed at that of the Creation, the Spring Equinox in Aries, as it will remain through the poem, it is the dawn of Good Friday. There must first be a descent to Hell in the sacred drama. A Crucifixion. A painful self-examination through example. He is obstructed from ascending, by the leopard, the lion and the wolf, by Lust, Pride and Avarice? By Florence, France and the Papacy? Lust that dances before the eyes, and pushes back towards the pit? Pride that creates fear in others, with its raised head and its envious hunger? Avarice with its leanness and craving, destroying the shared experience, buying and selling where giving and receiving should operate? A Florence with potential for hope but seduced by trivialities, by short-termism, by superficiality and pleasure? France, or perhaps the Empire, rapacious and envious, failing to build and bring justice? A Papacy flawed by corruption, drawn to wealth, clutching greedily? At all events three barriers, bringing confusion, fear and sadness. Mirroring perhaps also the three major divisions of Hell, the fraudulent and traitorous, the violent, and those who failed to exercise self-control, taking them in the order of their depth within the Inferno, and identifying them with the wolf, lion, and leopard respectively?

Hope is lost. This is the verge of Hell. The Individual desires the good, but must first understand the darkness. ‘Inferna tetigit possit, ut supera assequi’ says Seneca, ‘I must touch the depths, to achieve the heights.’ Those social forces that should help the Individual, his native place, political structure, institutions of faith, have failed him. The Authorities are bankrupt, City, Empire and Papacy. But this Individual still has desire for the good, has been awakened, has come to himself in recognition. And Dante will throughout recognise examples from the past and the present, he will be aware of what is around him, he will question and seek, he will thereby learn or rather disclose. The pupil is ready, but where is the teacher? The traveller is ready but where is the guide?

MedI:2 Virgil: Inferno Canto I:61

The teacher and guide will come from the past, a poet, a guide to the true Empire, a moral spokesman, a strong character, yet must be a pagan since it is Beatrice who Dante knows will be the guide later on to Paradise. There is such a person to Dante’s knowledge, and one whose own epic work already touched on the nature and structure of Hell, as a pagan Underworld.

Virgil, creator of the Aeneid, and its Book VI, seminal for Dante’s own work, was just such a great poet who sang a salutary message to his Roman world, holding out the path of true virtue to the Empire, revealing its own history and present, strongly moral in his own life, an exemplar.

Virgil appears, hoarse from the long silence of neglect, from his own silence in death, and enters the wasteland. Another human being, in fact a spirit guide, a master of poetic style, and a wise teacher, and one loved, and read intensely by Dante. A Poet will hand on the torch to a Poet. And he was an Italian, of Mantua, a precursor. He is aware now of his own paganism, the false gods of his age, and points Dante towards the path to salvation, expressing surprise. Why doesn’t the intelligent Dante see the way? And Virgil proclaims that the current Papacy, and its Avarice are an obstacle. That Dante must go another way, the way of the Individual (was that not the heretical cry of the Albigenses, and the Manicheists?...that individual path disregarding the established Church, how dangerous for Dante, unguided to attempt it.) Virgil is now his contemporary in the Vision. Time has collapsed or rather concatenated to allow Rome to touch Medieval Italy despite the intervening years. All Christian time is contemporaneous, since Christ and the Deity are ever-present. And are there not many moments in Virgil where the pressure of imminent Christianity is felt, Virgil can almost seem like an early Christian at times. And Dante is humble before him. Dante is the outsider, the exile, where Virgil was the insider. Dante is gauche and inept where Virgil was assured and confident. Dante is morally flawed where Virgil was fine and tempered. Dante is the nervous modern, anxious, wracked, troubled, uncertain, lacking in hope, out of his way. Virgil seems none of those things. Virgil already holds the golden bough, has already read the Sibyl’s leaves, has already been in the Underworld. There is a ‘real’ spiritual journey to be made. One has to look and walk. One has to think and feel. There is no need for mysticism. One only has to read the manuscript of eternity, and history, and thought. One only has to be an expert copyist to achieve some faint imitation of the Divine structure of existence. One has to remember, recognise, be aware and consider. One must ask and listen. The good news will appear from outside the Individual, yet within him, and not mystically but in a revelatory fashion. It is already there. Dante’s Vision is of what exists, not what needs to be created. His task is to make it appear solid in the mind, through symbol and description. He has to draw back the curtain, examine memory, send out ripples and echoes.

MedI:3 The Salvation of Italy: Inferno Canto I:100

The poet and guide immediately initiates another great theme by prophesying a political saviour, an Augustus, who will return the world to Roman law, to Virgil’s own moral rectitude. This political champion will feed on the great triad, on Wisdom or Truth, on Love, and on Virtue or Goodness. Perhaps it is Can Grande, this Greyhound, this destroyer of the wolf of Avarice. Dante strengthens the link to Rome with Virgil’s references to his own well-known characters, Trojan and Italian, from the Aeneid who are killed in the process of Aeneas the Trojan establishing the proto-Roman rule over Lower Italy. With this initial thrust Dante declares the political disaster of Church and State competing for total rule over both spiritual and temporal domains. He sets himself ultimately against Black Papally-oriented Guelphs and White Imperially-oriented Ghibellines, and is ‘a party of one’. The political exile finds here in this speech of Virgil’s a more ancient ally for his political cause. Already here Virgil is implying the reality of and diagnosing a recognised disease in the body politic, and subtly declaring Dante’s own political stance. Avarice will be chased back into Hell along with the corrupt Popes, like Boniface, whose place is reserved in the Eight Circle. The prophecy of a saviour will be repeated twice more, by Beatrice in Purgatorio XXXIII, and by Saint Peter in Paradiso XXVII.

MedI:4 The Boundary of the Pagan: Inferno Canto I:112

The iron structure of the universe is now revealed. Virgil as a pagan cannot enter Paradise. Though as we will see in Inferno Canto IV some of the great Jewish spirits of the Old Testament have been snatched from the Inferno to Paradise as Christian pre-cursors. Virgil in not acknowledging the Old Testament Deity (though in ignorance we presume) but acknowledging the false gods of Greece and Rome, and the deified Aeneas, Romulus and the Caesars is outside the pale. He will lead Dante through the places he has seen, having been to Purgatory before.

Hell is where the tortured beg to die again in order to escape, though there is no escape. Dante’s pity will be stirred by the desperation and pain. Purgatory is a place of hope where the pain is a precursor to salvation. And Paradise, which lies beyond Virgil’s personal knowledge, is the space of faith, of the blessed, where Beatrice will be the guide. All is ruled by God, but Paradise is his city.

Already the cities of Florence, Rome, and the Deity have been indicated. The city is Dante’s primal social construct, and the citizen the primary civilised human being. Here is Aristotle’s influence.

And so Canto I closes with that reference in passing to Beatrice, his third great theme, the first two being those of the journey of the Individual towards redemption, and the political state of Italy, Empire and Papacy, or Dante’s need for salvation, and his aspirations for the politics of the Western world.

There she is, implicit since we have read the Vita Nuova and know the story, as yet un-named, the feminine guide of the soul, who will eventually take over from the masculine guide of the mind, divine philosophy who will transcend and amplify natural and temporal philosophy.

The three great themes have been skilfully laid out, the first guide has been acquired, the future journey has been outlined in nature and architecture, time and place have been defined, the promise of finding Beatrice again has been hinted at. The two poets, old and new, move on. The Individual is no longer totally isolated, he already has helpers and sympathisers. What could not be achieved alone, can now be contemplated and begun.

Meditation II: Inferno Canto II

MedII:1 Doubts and Fears: Inferno Canto II:1

Dante’s triple rhythm, his terza rima, celebrating the Trinity in the inner structure of his verse, has drawn the triple strands of his life together in Canto I: his spiritual journey (the soul), his political existence (the mind and body), and his poet’s love of Beatrice (the heart). The three cities, of God, Rome and Florence are the backcloth to these aspects of his life and each figures in each thread. The city of Florence is where his love for Beatrice began, is the place from which his politics exiled him, and is where his spiritual journey also started. The city of Rome, Imperial and Sacred, is his political and poetic reference point, and is the seat of the corrupt Papacy. The city of God is his greater authority, granting temporal rights to the Empire, and the space where he will again find Beatrice and the true path of the soul.

Now in Canto II, which is the first Canto proper of the thirty-three Cantos of the Inferno (there are thirty-three Purgatorial and thirty-three Paridisial Cantos also) since Canto I has served as an introduction to the whole work, immediate self-doubt sets in. Having wound the three strands together, Dante now realises the magnitude of his task. The light fades, other creatures may sleep, but the Individual, the ‘one, alone’ must now set out on his painful labour, his ‘inner war’. The journey through the Inferno will be one of Pity.

The Medieval view here conflicts with ours. In our age we feel that pity and compassion must be translated into the alleviation of suffering, in an attempt to confer some dignity and humanity on even the worst offenders against the moral and civil laws. To the Medieval and Classical ages, pity was wholly compatible with a ruthless execution of the law, and the greatest agonies of destiny. Pity was a response of the individual to the pitiable, but not a reason for commuting or reducing punishment, which was written into the structure of the Universe by an all-powerful, and loving Deity. (Ivan Karamazov could not accept such a Deity and nor can I, but the Middle Ages certainly could and did). Faith, Hope and Pity are the great themes of the Paradiso, Purgatorio and Inferno. The Paradiso embodies Faith, the Purgatorio reveals Hope, the Inferno inspires Pity. The Inferno does not embody Pity, because Divine Justice is without pity there. The Pity is in the poetry, and in the witness, in the observer, that lone Individual. Failure to feel Pity would condemn Dante, as a soul not worthy to be saved.

The Muses are now invoked. And error-free Memory, not Invention, is what Dante calls on. He will be a faithful scribe of the Divine reality, glancing up and across tirelessly at the manuscript of the Universe, of the Past, Present and Future, as he illuminates the book of the Commedia, the Divine Theatre. Bent to his desk we see him: destroying his eyesight for the sake of the faithful reproduction of the Vision.

At once the self-examination begins, and the request to Virgil to begin the wider external examination. Aeneas went to the Underworld in Book IV of the Aeneid, well Dante is no Aeneas, no founder of Rome and Empire, those two sacred spheres of action. Not a Paul who made Rome the centre of the Faith. He is neither of those builders of the earthly City. So Virgil alone must judge if he is worthy, he thinks. Dante’s poetic and political pride, his sense of being in the right and fulfilling a destiny, his certainty of his age’s political errors, and of his own future fame, both give way before his spiritual anxiety, his uncertainty concerning his own soul. He wavers, he almost ‘unwishes, what he wished’. Here the Christian sense moves counter to the old Classical certainty. In the Classical world one propitiated the Gods as best one could, and the Gods chose, the uncertainty was in the nature of chance and fate not in the individual. Here one is on one’s own, faced with a true way and therefore able to determine one’s own spiritual destiny, even in the last breath of life, yet uncertain of ultimate worth and capability, needing intervention, assistance, grace. Does he trumpet his own Humility? Is there a secret certainty that if not building an earthly city he is at least building an intellectual structure that will reveal the spiritual City? That lurking Pride is always endearing in the man, even his pride in his awareness of the need for humility, which is almost a step on the way to humility itself! But there is a genuine feeling of concern too. As a poet as a politician he feels certain of his worth, but as a lover and as a Christian soul he is unsure. His confidence in himself fails before Beatrice and before the Light of Truth.

Dante inherited three great modes that made three great threads of his life. He inherited the spiritual world of Christianity and faith, where humility is a pre-requisite of the spiritual journey. He inherited the poetic, political, and Imperial world of Rome, the world of ‘being in the world’. And he inherited the poetic world of the Troubadours and Provence, that Arabic and Christian influenced world of courtly love, with its commitment to the beloved, humility before the beloved and the Lord of Love, and denial of self-worth. Here in the dusky air on the dark shore it is the anxious spirit and nervous lover who is uppermost.

MedII:2 Beatrice: Inferno Canto II:43

Virgil, the pagan in Limbo, was chosen then by Beatrice, moved by love, to go to Dante’s assistance. Dante is to understand that the journey is triggered from outside, initiated by Love, furthered by Beatrice, prompted by Virgil directly. She is Divine Philosophy and she is also his beloved Beatrice, of the angelic voice, her eyes brighter than two stars (eyes brighter than the twin Gemini stars of his birth-sign). God’s grace that prevents her fear, which must temper fear in Dante also, allows her to enter Limbo, from Paradise. She represents virtue and beauty, love and truth. She is that on which Dante’s mind must fix on his way to the goal beyond her, that of the ultimate Truth, the ultimate Love, Virtue and Beauty. She offers Dante through Virgil, friendship and humanity, aid and eloquence. She has passed through the fire to bring Dante help, unscathed and without fear, through grace. He must pass through the fire at the top of Purgatory to reach her, in fear but unscathed, and aided by grace. She has descended through the fire, out of love, to bring help to a man troubled by lust, and he must pass from the circle of the Mount where lust is purged, through the fire, to reach her, in his love for her. She is the object of courtly love of the troubadours with the erotic charge of that tradition, but she is spiritualised with the attributes of the saint. Love itself is no longer Amour but empowers the spirit to rise to Heaven, it is no longer a rhetorical device or a pagan concept but a marrying of intellect and emotion, of feeling and reason, of mind and heart. It is a force for good, for spiritual redemption, as a reflection of Divine Love that enfolds the universe, and no longer the potentially destructive force of the Troubadour lyrics. And so Beatrice can symbolise everything that leads upwards in Dante’s hierarchy, Love, Intellect, Philosophy, Theology, Faith, Hope, Pity. She is the directional arrow.

MedII:3 The Hierarchy of Love: Inferno Canto II:94

And it is the Virgin who has interceded. The feminine principle, the Goddess (I will not trace all the well-known aspects of the ancient Goddess that were incorporated in the Medieval Cult of the Virgin, and the continuity between her attributes and those of earlier feminine divinities, but she is associated with the sea, and starlight, with lions and doves, with beauty and remoteness, and so on, from earliest times). At the top of the hierarchy of Love she calls to her a saint, Dante’s personal Saint, Lucia, Illuminating Grace, associated with the eyesight and light, Lucia ‘opposed to all cruelty’, and she passes on the message, down the hierarchy, to Beatrice, Divine Philosophy, who is sitting with Rachel, Contemplation, in the third rank. Rachel for whom Jacob patiently worked and waited, as Dante has in a sense for Beatrice leaving ‘the common crowd’. Rachel the Jewess one of those Old Testament figures raised by Christ from Hell to Paradise. Beatrice carries the message to Virgil, as he will to Dante. ‘No one on earth was ever as quick to search for their good, or run from harm’ says one of Dante’s lovely similes, one of his swift examples that bind the real world to the world of the Vision. The threefold feminine message is sealed with her tears as Virgil receives it. And the passing of the message is an exception to the rules, as Dante’s journey is an exception, in taking a living man among the shades. So the whole Divine Comedy is a movement of compassion, and intercession, an act of love, at its very inception.

MedII:4 The Descent to Hell: Inferno Canto II:121

Virgil proclaims the trinity of ladies in Heaven, who care for Dante. And Dante himself brings forward another perfect simile, one of great beauty, as the man bent with the chill of fear and anxiety, unbends like the night-chilled flowers at the light of this sun of Love. And, Dante’s will empowered, recognising Beatrice’s help and Pity, Virgil’s gentility and swift agreement to her request, she who has placed faith in Virgil’s true speech, and he who has obeyed her true words, he and Virgil move forward again, down the steep way which is tree-shadowed in the Classical sources, that path of which Virgil said: ‘Facilis descensus Avernus’ (Aeneid VI:126) ‘the way to Hell is easy’, and Ovid speaks of as ‘gloomy with fatal yew trees’ (Metamorphoses IV:432), the path that leads to the City of Dis. They are somewhere in Italy, at one of the chasms, the downward tracks to the Underworld, perhaps at Cumae, where Aeneas entered. But the precise location does not matter. As Virgil says, it is easy to enter Hell from any place. This is the downward path of the spirit.

Meditation III: Inferno Canto III

MedIII:1 Divine Justice: Inferno Canto III:1

The Gates of Hell are the gates of adamantine Justice. Dante, anxious and bewildered, gazes at the message over the entrance. Here we have to stretch our modern imagination and sympathy. Constructed by Love, by Wisdom? By Power certainly. The very thing we might mistrust in our age, Power, is evident here, and the values we might honour of wisdom and love, are not obvious to our ethically different eyes. This is God’s plan for humanity (the creatures don’t appear, lacking souls, other than for the purposes of analogy or symbol, which is another problem for our biologically oriented era). This is a threshold, requiring courage, incorporating the Holy Trinity of Power, Wisdom and Love. And Virgil offers small comfort. What Hell signifies though is the loss of that good derived from the intellect, and it is the medieval world of reason that Dante must use to penetrate Hell and beyond, reason embodied in philosophy, philosophy that is a conduit for divine truth to the world below, that strengthens human faith and points up the ladder of creation again through the angels to God who is pure intellect (Convivio III vii 5). This is a neo-platonic vision. And though Dante sees the beatitude of this world as dependent on the intellectual and moral virtues and ideally under the control of the Emperor, while the beatitude of the higher world is dependent on faith, hope and pity, the theological virtues, and ideally, on earth, under the control of the Pope, once beyond this world intellect does not vanish but is refined as it nears the godhead. The progress through this world is benefited by the operation of one’s own virtue, while that through the next requires divine assistance. (Monarchia III XV). The light of intellectual love holds the Universe bound together, and its power flows downward to humanity.

The Gate of Justice is the first guardian of the threshold, and beyond is danger. The intellectual companion Virgil reaches out with a calm expression, he has been here before and is one who knows, to comfort Dante, hand on hand. The message over the gate is desolate, but through the good of the intellect, through endless observation and questioning, through listening and seeing with the mind, there is hope. Pity embodied in Dante the Christian, more so than in Virgil the pagan, takes a walk through Hell.

MedIII:2 Spiritual Neutrality: Inferno Canto III:22

The darkness is full of cries. What terrible sins have these spirits committed? Intellectual sloth, spiritual indifference, the self-centred neutrality of those spirits that strive neither for the good nor for the bad, who fail because ‘they have never lived’. Harsh? All sin and error is Hell, the depths are merely symbolic. There is no hope here, any more than deeper down. This is a terrible medieval no-man’s land, a place where there is nothing to hope for, nothing to repent of, and nothing of beauty to remember. This is one of the very strangest chambers of Dante’s imagination, and indicates the deep hatred of the non-intellectual that every intellectual revolutionary secretly nurtures. They suffer more than the pagans in Limbo who at least like Virgil used their intellects, though falling short, through ignorance of the Christian message. This place, the very first place entered after Virgil’s comment about intellectual good shows the importance Dante placed on living a whole life, with mind spirit and heart, the three great strands he weaves endlessly in the Commedia. It is a vision of the sensitive mind that looks for an echo of sensitivity in all parts of the universe. God’s inscrutable logic is here at work. Dante is here to see and learn. The first lesson is that loss of the intellect, indifference to it, is also Hell. The punishment fits the crime, the no man’s land of life becomes a no man’s land of non-death. And their symbol is Celestine V, the Pope who was driven by the winds of fortune into the Papacy and who abdicated from it, a refusal that clearly irritated Dante deeply. The courage Virgil called for is not merely physical courage, but intellectual and moral courage too. And punishment is an imaginative parallel, an analogy, throughout Hell, so that torments may appear to us to be heavier or lighter than they ‘should’ be according to a grading of torments that might have matched the gradations of Hell. God is a poet too! Failure to use the free will is a crime as great as any, since free will is the greatest gift of God.

MedIII:3 Crossing the Acheron: Inferno Canto III:70

A pause almost, for a powerful poetic vision of the spirits gathering at the second threshold of the Acheron. Beyond it is Limbo and the First Circle proper of Hell. Dante asks a question. Virgil tells him he will receive a reply. Dante is humbled, ashamed and downcast, fearful of having offended. He is as he frequently is in the Commedia awkward and troubled, unsure of himself or of the etiquette, noble but somehow impoverished. The opposite of a pagan hero, a Christian anti-hero, a student, a child almost. But Virgil, the courteous master (Dante enshrines the values of Troubadour cortesia and transcends them), confirms to Charon that Dante is aligned with Aeneas and Paul, that his journey is willed above, that he is one of those whose work is to bind Empire and Church to their proper places, and to reveal earthly dualism, and Heavenly hierarchy, in a neo-platonic vision. The spirits in pain and blasphemy are misusing language as they have misused free will, as Adam did, of whom they are the evil seed. And Justice is the goad that converts their fear to a desire to cross where no one in their right mind would wish to cross. These must be recently dead contemporary spirits, but Dante singles none of them out, recognises none of them. He is the anti-modernist, the anti-contemporary, who is looking back and forward not sideways. He does not even recognise the ‘some among them’ whom he recognised among the spiritually neutral. He faints now, and somehow the Acheron is crossed.

Meditation IV: Inferno Canto IV

MedIV:1 Limbo: Inferno Canto IV:1

On the brink of the First Circle, even though he is returning initially to his familiar place in Limbo, Virgil pales. But he replies to Dante that it is not fear that causes his loss of colour. It is Pity. Justice is pitiless in operation, but its results create pity in the observer. Pity, charity, is the keynote of the Inferno, but not mercy. To alleviate the torments of the sinners, symbolic or real, would be mercy for those who have not deserved mercy, because they have died denying God. But pity and compassion, empathy and identification are attributes of human feeling. There but for the right use of intellect and Christian baptism go us all, says Dante. The Pity is in the seeing, in the voyeurism of the passer-by, not in the structure of Justice, which is implacable. For some things there is no forgiveness. Forgiveness is for those who recognised God and purge themselves of their sins. Paradise requires Divine intervention, God’s grace. Hell is where there is no way forward and no way back. It is this infinite howling.

So Virgil pities those below. But in fact the First Circle is ‘without torment’. Here are the un-baptised. Those who died before being able to know God, historically or in their life. The heathens and those dying before baptism. It is not a barrier to worth, there are many worthy spirits here, but to redemption. That is God’s law. It is a place, says Dante initially, that is not a place of torment, and yet those there live in desire without hope. What is that to us Moderns but torment? And Virgil confirms it: that is their ‘only’ torment, as if that were not enough!

Jesus has entered Limbo to pluck from it the Old Testament great ones: Adam the source: Abel and Noah, the pious: Moses, the lawgiver, and the Patriarchs: Rachel: and ‘many others’ who remain undefined here, but later we will find Solomon for example in Paradise, and Eve and others are there sitting below the Virgin, believers in the Christ to come. Such are the rules: and Dante here accepts what appears to us the extreme injustice of un-baptised infants remaining in Limbo, something even Saint Bernard had problems with, and the eternal condemnation of his master Virgil and the other great pagan spirits to their place in the Inferno.

MedIV:2 The Great Poets: Inferno Canto IV:64

For Dante time in the Vision is God’s synchronous moment, even though time passes and the chronology of the Vision is so carefully worked out. Delightful! Though time’s processes run on, and the characters walk and talk, and dawn and evening happen, nevertheless, like some great instrument sounding many notes from different ages, the moment of the Vision contains all history, and all the famous people of the past can appear together. In a sense this is the old Greek and Roman afterlife, where the heroes of many ages brush shoulders with each other, but in the Odyssey and the Aeneid the Greek cultural unity blurs the impact of that reality. Here Classical, Biblical, and Christian spirits are in a sense contemporaneous with those of later Imperial history and the Medieval past. Here any of the dead from one age can be alongside any of those appropriate from some other (though Dante is careful to preserve artistic form and harmony in extended passages), and only Dante is still a living spirit. All examples are present, all those who need to be questioned can be. Yet earthly time is still to come and only prophecies can lead forward into it. History is still being played out. The Vision is set at a specific time. There are souls still to arrive beyond, there are places set aside in Hell for some of them as we shall see. Dante’s own spiritual life is still unfolding, real events beyond the Vision of 1300 are still to happen and Dante must not let obvious knowledge of them intrude except as those self-fulfilling prophecies. But into the construct of the Inferno are crammed all the ages past: into the thunder of the abyss. Beyond is Christianity and the Purgatorio and Paradiso, with some choice spirits plucked from pre-Christian times. But here, deeper down than Limbo, all history is present in one great cacophony of sin. Hell is here an eternal recurrence, while Purgatory will be a progression upwards to the eternal moment of the Paradiso where all times are truly contemporaneous and ever-present.

For a moment though there is peace and tranquillity. The great Poets recognise Virgil, and, in a blush of false modesty, Dante is also allowed to join them. He already knows his destined place. And he recognises Pride as one of his major faults. He is a sixth beside Homer, bearer of the sword, who appears ‘as if he were their lord’, Horace, Ovid, Lucan and Virgil himself. Dante here declares his major Classical sources and influences. Horace, as moralist, and Lucan, as epic historian, we might find a little surprising. Dante walks on with the Poets, in a secret inner conclave of the great. The modest mask slips a little. We are not allowed to hear the conversation. It is ‘best to be silent’. There is also clearly no one sufficiently great to be worth mentioning here between Lucan and himself, a thirteen hundred year pause. He sets himself in the direct line of Imperial Rome and the Classical secular poets.

MedIV:3 Heroes, Heroines, Philosophers: Inferno Canto IV:106

After Poetry and a resonance of the personal life, come characters from Imperial History, from Troy and through the Wars in Latium of the Aeneid to the Republic and Empire, with the interesting addition of Saladin, the noble infidel, and then characters who exemplify the life of the Intellect, with Aristotle not Plato as the master, and showing the debt to Arabic commentators. Dante is again weaving together the personal, historical, and spiritual or at least intellectual themes. The Greek, Roman, and Medieval worlds provide the large majority of examples.

He and Virgil move on rapidly from the calm of Limbo to Minos, the Judge, and the lower Circles of the Sinners.

Meditation V: Inferno Canto V

MedV:1 Minos, and The Carnal Sinners: Inferno Canto V:1

Minos is the guardian of the next threshold, the judge of those who have truly sinned, by abusing and misusing their freewill. Those we have seen above were the spiritually neutral who failed to use their free will through passivity, indifference and selfishness, and those in Limbo who were unable to exercise it fully in a spiritual sense through ignorance of God, despite their worth. Now we begin the descent through those who had the chance to embrace God but chose otherwise, through weakness, or malice. First are the circles of those who lacked self-control, and below them are the circles of the violent and fraudulent.

Minos is the judge and decision-maker here, his Classical role of lawmaker and judge of the dead confirmed by Dante. Like Charon he addresses Dante and Virgil: Hell has its voices. Virgil again asserts that Dante’s journey is willed from above, once more placing Dante in the line of Aeneas and Paul, Empire and Church. They pass on to the carnal sinners in the whirlwind those who gave up the good of the intellect, and ‘subjected their reason to their lust’.

Two of Dante’s beautiful extended similes follow, the flock of starlings and the line of cranes, invoking memories of Classical augury from the flight of birds: the Iliad Book II where Homer compares the Achaean clans to the flocks of geese, cranes, or long-necked swans that gather by the River Cayster in Asia Minor: and Ovid’s love of birds revealed in the Metamorphoses. He creates a feeling of numbers, of the extent of Hell, sweetly, and without strain.

Dante momentously parts company, as he did in the Vita Nuova, from the Troubadour tradition, while absorbing it, since adultery or at least adulterous desire was a cornerstone of that tradition. Dante retains the other characteristics of that tradition, Humility, Courtesy and the Religion of Love, but all three are subsumed in the spiritual life. Love grants the power to rise to Heaven if coupled with Intellect and Reason. Beatrice has the characteristics of the Saint, of a Clare or a Margaret of Cortona, and their authority, as well as the erotic charge of the tradition of courtly love. Love is then a redeeming force, the spirit preventing ruin through raw desire and emotion. And Beatrice can also be the philosophic intellect, pure intelligence mediating divine truth to the world below, aiding faith and showing Heaven’s beauty and joy. But here, condemned to Hell, are those who took the path of their passions, losing the good of that intelligence. Tristan is there and presumably Iseult. Cleopatra presumably with Antony, though Dante may subtly be hinting at the relative guilt within these pairings. Virgil points out the shadows with his finger, naming ‘more than a thousand’.

MedV:2 Love’s Heretics: Inferno Canto V:70

What this space invokes in Dante is Pity. His weakness was Lust, as well as Pride. Another bird image: Paolo and Francesca approach at Dante’s call, like ‘doves, claimed by desire’. Dante begins here that endless questioning which will run through the Commedia, a great demonstration of the path to knowledge, through enquiry and thought. Francesca speaks in reply, and the poetry of her voice affirms the power of passionate love. She speaks to Dante since ‘you take pity on our sad misfortune’. The root of their love was a single moment, hovering over one of the tales of courtly and adulterous desire, that of Lancelot for Guinevere. Dante both warns here, and affirms the influence of that tradition’s sweetness on himself. Was not he drawn to poetry through the Troubadours and Virgil’s tale of Dido, and Ovid’s tales of passion, and so on? And Dante faints from Pity. Justice demands that those who misused the intellect, and the power of the feelings, who did not sublimate desire in the quest for reason, should be condemned to this eternity of longing without rest. At least they are together.

The whole episode immediately calls to mind the story of Abelard and Heloise, that twelfth century cry of the heart that Dante knew (he had been in Paris himself it is surmised). That Abelard whose reliance on the questioning intellect was so excessive, Bernard condemned it, Bernard for whom the mystery of faith transcended human reason, and could only be gained by contemplation and grace. This ultimately is Dante’s own position, though he still insists on intellect as the path towards that point where Divine grace can intervene. Bernard condemned Abelard as a heretic. Abelard told the tale which must be read, of how ‘more words of love than reading passed between us, and more kisses than teaching’, and then we have Heloise’s letters (perhaps a literary invention but no less powerful for that) those calls of total human love and of a soul in longing that tear the heart, ‘a love beyond all bounds’, she who ‘would not have hesitated, God knows, to follow you or go ahead at your request into the flames of Hell’. Like Tristan and Iseult, their story which is also one of punishment by fate, and of moments of living hell, is pagan, secular, sensuous and ultimately Stoic, and asserts the cry of human freedom. Dante could not ignore it, it was his own early story in many respects, but he denies like Bernard that unbridled love is the right path. And so caught himself in that conflict, a conflict he was still passing through, between the claims of love on this earth and the claims of the spiritual life, he faints.

The understanding of this episode and the reason for its emotional and poetic power is critical. Dante embraced wholly that tradition of courtly love, was seized by it, yet transformed himself, through commitment to intellect and learning, as he spells out at the end of the Vita Nuova and later exemplified, and so ultimately transcended the old tradition. Love became a marriage of mind and heart, of intellect and feeling, of spirit and emotion. Beatrice was spiritualised, as Dante came to deny Guido Cavalcanti’s view of love as an accident, an irrational force, and destructive of virtue, and himself drew from Franciscan radical thought and the reality of the ‘holy woman’, her miraculous power, devotion, influence, saintliness. The religion of love in his hands becomes the religion not of Amor but of God, Still the old stories drew him. Their human poetry. Their human reality. Their cry of deep human love. And their sense of tragedy woven with beauty, transience with commitment, delight with disaster. The story of Paulo and Francesca is almost irrelevant. Go read the story of Abelard and Heloise, the conflict of passion with religion, of Abelard’s path of total intellect with Bernard’s of contemplation and grace, to understand why Dante is so powerfully affected that, out of Pity, he falls ‘as a dead body falls’. It was his spiritual and personal crisis too. And the questions and answers in the Commedia are part of his journey from Courtly Love, and the even more dangerous reality of Abelard, to the spiritualised Beatrice. Abelard and Heloise are conspicuously absent from the named spirits of the Inferno, though Heloise might be expected among the heretics rather than the lovers. Dante fought in his own mind for orthodoxy, and it is Bernard the lesser intellect but the deeper mystic who presides over the last Cantos of the Paradiso, as perhaps Abelard and Eloise in spirit preside over this first true circle of the sinners.

Meditation VI: Inferno Canto VI

MedVI:1 Ciacco’s Prophecy: Inferno Canto VI:1

Dante recovers from the empathetic trauma of Francesca’s story, his ‘complete sadness’, and the poets pass by Cerberus through the tainted rain, over the putrid earth. This is the third circle of the gluttonous, and Virgil quiets Cerberus by stuffing his greedy maw with the corrupted soil. Cerberus, the monster, carves away from the shades that substance they have added through their gluttony.

Paulo and Francesca have given us the first encounter of conversational substance in this Commedia of interrogations and avowals, of autobiographies and instructions, of examinations and responses, of introductions and challenges. Dante’s inner tensions and anxieties, his hopes and fears, surface in these dream encounters, these visionary dialogues, these pocket dramas where he can rehearse both his failures and his imagined triumphs in verse within his own control. Dante selects his examples and then has them reveal, or divulge, or present, just that of themselves that fulfils his purpose, and usually enough to make them live again, briefly, or at some length, in words like those on the plaques below statues, or the inscriptions on sepulchres, in dramatic exchanges, or with whole monologues.

Now there is the first of the ‘guess who I am - I don’t know, tell me’ types of meeting. After the personal and spiritual challenge to Dante of the Paolo and Francesca episode, he moves to the personal and political. Here is Ciacco the Florentine. Dante wants to awaken an immediate interest in his Italian audience, and he uses a ‘prediction’ of the near-term political future to do so. Ciacco’s prophecy outlines the outcome of the struggles of the Black and White factions in Florence during 1301-1303. The Blacks under Corso Donati allied to Pope Boniface VII, who was in turn allied to the French King, Philip IV, and his brother Charles of Valois, defeating and expelling the Whites led by the banker Vieri de’ Cerchi. Allied to the Whites and their desire for Papal reform coupled with support for the Hapsburg Empire, Dante nevertheless incurred the enmity of both parties, though he was exiled in 1302 as a White. His desire for a separation of Empire and Church, involving the reform of both, placed him against the pro-Papacy Blacks and the pro-Empire Whites. His idealism struggled to find a place in the complex web of politics. He was of those who hoped for a spiritualised Papacy, and a ‘saviour’ for the Empire, one of the dreamers and revolutionaries, like the Franciscan radicals, wishing the Church to return to its goals of poverty and spiritual authority and to cease meddling in power politics, and like the political ‘right’ yearning for the return of ancient Imperial authority, law and structure, a political regime that would equally cease to meddle in the affairs of the Church, and the world of the spirit. Alas, idealism is usually doomed to disappointment.

Dante has managed already then, at this early stage, in this and the preceding Canto, to sound the three great notes of his Commedia, his personal life of thought and poetry, love and Beatrice, Florence and exile: his political life and aspirations for a reformed Empire and Papacy: and his spiritual life with its struggle to weld reason and love, intellect and passion, learning and revelation, into one whole, one single Vision of the Divine Light. The Francesca episode hints already at the unspoken text of his spiritualization of love, the Ciacco prophecy at his as yet unrehearsed dualistic concept of Church and State. Both were already obvious to his contemporary audience. The first from his Vita Nuova and its closing words. The second from his forays into politics and his continuing exile.

Now Ciacco, in passing, highlights Pride, Envy and Avarice, as the root of the political evils. Dante calls the prophecy ‘mournful’ (!), and then swiftly asks after some of the great Guelph (Black, Papal alignment) and Ghibelline (White, Imperial alignment) captains and politicians of the recent past who are already dead. Ciacco tells him those he named are deeper down in Hell, but for other reasons than their political allegiances. Ciacco then issues the first of many requests by the spirits to be recalled or prayed for in the world of the living. This is the human desire for recognition, for remembrance, and for assistance expressed by the dead to Dante so that he can communicate with those who are still alive.

MedVI:2 A Question to Virgil: Inferno Canto VI:94

Now, Virgil offers the first example of an extended series of statements, questions, and answers to those questions, that reveal religious orthodoxy and dogma throughout the Vision. The Commedia sounds always the deep, and sometimes harsh or sombre, notes of the appeal to Divine authority. Dante enjoys finding the eloquent phrase that will express that resonance of the accepted truth. And there are appeals to Imperial orthodoxy also. They are not presented as mindless bowings to received opinion, or mere protection against error. Dante is learning, and testing the dogma also, reasserting the reason for it, and sometimes the need for unreason and faith, for trust. He presents himself in the Commedia as an eternal student, questioning but accepting the word of the great spirits he meets and is guided by, above all Virgil and Beatrice. Ultimately he trusts in the authority of revealed truth: and therefore, in the world, he would like to trust in the authority of an Imperial central power, and a reformed Church, that would express that Divine authority and trust in worldly terms. But beyond this world he also has revelation, contemplation, intellectual light, and spiritual passion to trust in, and ultimately it is the Franciscan purity of Lady Poverty, and the Classical purity of early Rome as expressed by Virgil, idealistic and ethically sound, that feeds Dante’s spiritual yearning. His sources are the noblest things he knows and has read, and the noblest things he feels and has experienced.

Virgil states that Ciacco like the other sinners in Hell is doomed not to progress, until the Day of Judgement. Hell is a place of spiritual stasis. A place where the spirits cannot go forward or back. Its very space constricts as the Poets descend. It becomes a dead weight pressing on the spirits, and on our and Dante’s spirits. Dante accepts Virgil’s authority regarding the afterlife and asks about the nature of the torments, will they increase after the Judgement when the spirits have returned to the flesh? Virgil replies in a slightly convoluted way, perhaps to dull the impact of the conclusion, that the sinners will be more perfect, therefore they will feel pain more!

Dante has illuminated another facet of his great theme in a simple way, the theme he enunciated in his letter to Can Grande della Scala accompanying his gift of part of the Paradiso ‘The subject then of the whole work taken in the literal sense alone is the state of souls after death, pure and simple…from the allegorical point of view the subject is man according as by his merits and demerits in the exercise of his Free Will he is deserving of reward or punishment by Justice.’

Meditation VII: Inferno Canto VII

MedVII:1 The Avaricious Church: Inferno Canto VII:1

Plutus, gabbling some unknown language of threat, guards the next circle of those lacking in self-control, the avaricious and their contrary. Virgil ‘who understood all things’ can interpret this mutilated tongue of the monster, a creature derived from Pluto the god of the underworld and Plutus god of wealth. In Hell language itself suffers, and becomes childish, guttural, nonsensical, or sibilant, as appropriate. Its moans and sighs, hisses and cries will become familiar to us.

For a third time Virgil confirms that Dante’s journey is willed on high, and mentions the Archangel Michael who fought against Satan, he who fell through the sin of Pride, a weakness Dante found in himself.

In this circle those greedy for material things, or careless of them, are made to suffer by rolling weights, lumps of matter. The churchmen, the Cardinals and Popes are the worst examples, since they are the ones who should have adhered to the way of poverty. Here is a condemnation straight out of Franciscan Radicalism, reflecting Christ’s own teaching: Francis’s ‘Lady Poverty’ must have appealed deeply to Dante’s imagination, as yet another and different allegorical spiritualization of courtly love. These sinners are evidence of that corruption of the Church and Papacy that Dante fiercely rejected. It is interesting that Dante classes prodigality with avarice as a sin, indicating that he is opposing the ‘getting and spending’ culture, particularly in the religious sphere, and again evidencing his underlying rationale, his sins are abuses of the gift of freewill.

His ethics are not concerned as our modern ethics often are with moral conflict, the problems of conflicting ‘rights’. It is not at all clear how Dante would have resolved those problems, as in his structure his examples are made to appear clear-cut. Brutus and Cassius, for example, in assassinating Caesar commit the greatest of crimes, as traitors, regardless of any view that they might have held that they were ‘striking a blow for freedom’. Note that it is not the physical violence involved in the murder, or the sacredness of life, that are Dante’s main grounds for condemnation, reasons that we might find fundamental to our condemnation of their action, but rather the act of treachery itself, the misuse of freewill. His sins are all in a sense intellectual, since it is reason that differentiates Man from other creatures in the Medieval world view. Reason is the unique human attribute, and its abuse is therefore the root of sin, which is a concept specific to human beings, who possess knowledge of the tree of good and evil, through being the seed of Adam.

In this schema moral conflict is in a sense to be avoided so as not to mar the perfection of God’s design, while in our world based on neo-Darwinian understanding of our biology and history as a species, and on cultural values spread by civilisation, moral conflict is recognition of our unplanned reality. That is not to invalidate Dante’s, nor our, belief in higher values, nor his and our condemnation of the abuses of intellect and of reprehensible actions and intentions. We can still support his view of certain things as fundamentally undesirable, and others as overpoweringly desirable, while also admitting the problems of moral choice, and the reality that many of our moral instincts, that derive from nurturing mammalian empathy and our creative drive, are inputs to the reasoning process from the non-rational roots of our being. We are more compassionate and merciful in our punishments often, as a result of seeing the complexities, but that equally does not change our repugnance for crime or the pain caused.

It is interesting to reflect on modern secular attitudes to suicide, for example, to abortion, to crimes committed in self-defence, to genetic engineering, and to the concept of ‘rights’, to see how our view of ethics has changed and is changing. Despite all that, if we are moral agents, we still have the same struggle inwardly with our own spiritual journey, against destructive and corrupting forces, and the same aspiration towards creative and empathetic actions and feelings. We can all still be in favour of modified forms of Love and Goodness, as well as Truth and Beauty. It is not hard then to identify with Dante’s personal journey.

Once one frees oneself from any requirement to endorse Dante’s specific grading and classification of evils, wrongdoings, misuses of freewill, which can seem both arbitrary and unjust by modern standards, then it is easier to endorse strongly his general thrust away from destruction and darkness, and towards creation and light, away from hatred and violence and imbalance, and towards love, peace, and harmony. If that is unashamedly a poet’s reading, then so be it. Poetry is often a different way of approaching reality, and a different kind of truth.

MedVII:2 Fortune and Mutability: Inferno Canto VII:67

Dante immediately asks about Fortune, and Virgil replies, giving a neo-platonic description of the downward flow of Divine light through the guiding powers of the heavenly spheres, including Fortune the guide of earthly splendour, who is concealed behind the world ‘like a snake in the grass’, a reference to that simile in Virgil’s own Eclogue III. Fortune is beyond human reason, and hidden from it, an agent of mutability and of the redistribution of wealth and power between nations. But time is passing, and the stars of Libra, the scales of Justice, are setting.

MedVII:3 The Wrathful and the Styx: Inferno Canto VII:100

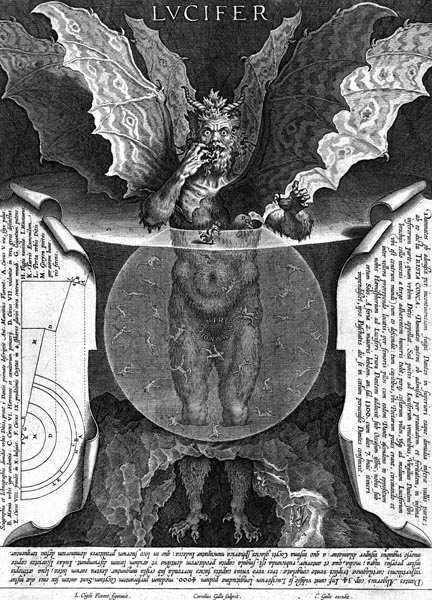

Dante has so far been adapting and enriching much of Virgil’s imagery in book VI of the Aeneid, a reading of which shows his indebtedness to Virgil for the idea of a structured Other-world. Charon, the Acheron, the gates and ditches and towers, Cerberus etc. much of the imagery of these early parts of the Inferno derives from Virgil. Now the Poets descend to the Stygian marshes where the Wrathful, sullen and violent, are tormented for their sins of Anger. They are submerged in the mire of their dark passion. The Poets are nearing the city of Dis, and must first cross the marsh. They will then have passed through the circles of the incontinent, of Lust, Gluttony, Avarice and now Anger, of those lacking in self-control, and into the lower regions, of Dante’s devising, whose structure Virgil will soon explain.