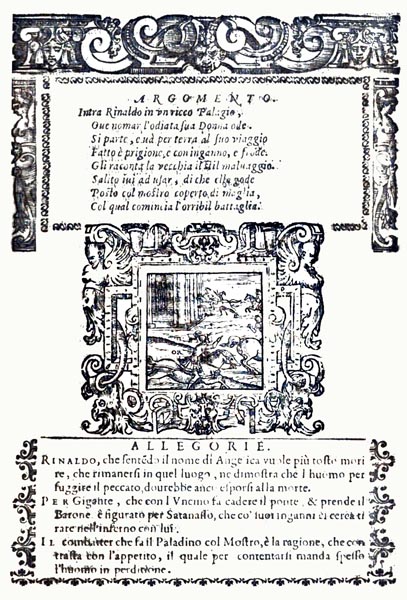

Boiardo: Orlando Innamorato

Book I: Canto VIII: Joyous Palace and Castle Cruel

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2022, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book I: Canto VIII: 1-6: Rinaldo reaches Palace Joyous

- Book I: Canto VIII: 7-9: He is led by maidens to a feast

- Book I: Canto VIII: 10-14: But disdains Angelica’s love for him

- Book I: Canto VIII: 15-18: The ship bears him to a wooded shore; he confronts a kidnapper

- Book I: Canto VIII: 19-24: He fights a giant, and is caught in a net

- Book I: Canto VIII: 25-27: He falls into the clutches of an old crone in Castle Cruel

- Book I: Canto VIII: 28-34: She tells of the murder of Grifone

- Book I: Canto VIII: 35-40: And of how she slew her and Marchino’s two sons

- Book I: Canto VIII: 41-43: And of the evil dish Stella served to Marchino

- Book I: Canto VIII: 44-48: And of Marchino’s cruel vengeance on Stella

- Book I: Canto VIII: 49-52: And of the creature in the tomb

- Book I: Canto VIII: 53-64: Rinaldo fights the monster

Book I: Canto VIII: 1-6: Rinaldo reaches Palace Joyous

Now Rinaldo had reached Palace Joyous

(Such was the name of that magic isle)

The first place at which the masterless

Vessel had touched, and moored, in this long while.

A garden twas, shaded and mysterious,

Encircled by the sea, and many a mile

(Quite fifteen or more) in circumference,

Flat, and verdant; its trees both tall and dense.

Above the shoreline, and towards the west,

A most beautiful palace could be seen,

Formed of polished marble of the finest

Quality, reflecting the island’s green.

Rinaldo, fearing to remain the guest

Of that ship, leapt ashore, and had been

Not a moment on land, ere a lady

Showed herself, who greeted him politely.

The lady said: Sir knight, your destiny

Has brought you to this isle, and so believe

It was not for naught that, fearful, o’er the sea,

You were led to the fair place you now perceive.

A strange and distant land, of a surety,

But though fate seems harsh at first, and you grieve,

To a sweet and pleasant end, you will move,

If you’ve a heart, as I think, fit for love.’

With this, she took Rinaldo by the hand,

And, into that fair palace, led the knight.

The portal was of marble, rich and grand,

In hues of black, and green, pure red, and white.

The pavement upon which they both did stand,

Of that same stone, was varied to the sight.

Here were loggias, of beauty untold,

With reliefs, and ceilings in blue and gold,

Hidden arbours, adorned with fresh verdure,

Showed above the roofs, and on the ground,

And gold, and gems, and splashes of colour

(Rare frescoes) in those pleasant courts were found,

And there were crystal fountains, moreover,

That sweetest shade-giving trees did surround,

But more it was the fragrance of that place

That to grieving heart might grant a joyous face.

Rinaldo was led by the fair lady

To a loggia, rich beyond belief,

Subtly adorned, where each wall and every

Corner held enamellings in gold leaf;

And slender snow-white columns, wrought finely,

Held gold capitals, topping each gleaming sheath.

All about, small trees, set to form a glade,

Covered an open lawn with their sweet shade.

Book I: Canto VIII: 7-9: He is led by maidens to a feast

Entering this loggia our knight was met

By a group of lovely maids, of whom three

Sang, while one played an instrument, as yet

Unknown to us, that wrought fair harmony;

While other maidens danced; none did forget

The measure of their steps, and thus, sweetly,

The handsome knight within their court did bring,

And, dancing still, drew round him, in a ring.

One, of kindly semblance, said: ‘My lord,

The table’s laid, your dinner is prepared.’

Then they led him past a fountain, to a board

Set beneath a rose-trellis; naught was spared

To adorn that place, with all it might afford

Of beauty or delight, its pleasures shared;

And each place was set in turn, while fold on fold

Of white napkins lay upon the cloth of gold.

Four maidens were seated there, and they

Drew our knight in amongst them, courteously.

He marvelled at his chair, which did display

Pearls of great size; twas wrought splendidly;

Rare delicacies, on gold plates, about him lay,

Wine-cups of great worth, most fine to see,

Were filled with wine, of most rare bouquet,

Served by three maids, each fairer than the day.

Book I: Canto VIII: 10-14: But disdains Angelica’s love for him

When this fine dinner was well-nigh complete,

And the golden ware removed from the board,

Harps and lutes could be heard, rare and sweet,

And a maiden soft speech did him afford,

For these fair words Rinaldo’s ear did greet:

‘These fine treasures and this palace, my lord,

And whatever else that your eyes may please,

(For much remains to view) are for your ease.

And all this place was brought about for you;

Our queen constructed it for you, solely.

Happy are you that, with a love that’s true,

You are beloved by our well-travelled lady,

She’s more blushing than the rose, to the view;

And, than the lily of the field, more lovely,

In her whiteness; Angelica her name;

More than her heart she loves you, she would claim.’

When Rinaldo heard, in that joyful place,

The name of the lady he hated so,

A pained expression passed across his face;

In all his life, he’d felt no deeper woe.

Now he no longer prized the wealth and grace

Of that mansion, it seemed a piteous show.

But the maiden said: ‘My lord, do not refuse

Her love; surely a prisoner may not choose.

Your sword, Fusberta, has no power here;

Nor would it help to possess Baiardo.

The sea encircles us, its depths unclear,

Here valour and courage but fail also.

Your hard heart you must soften now, I fear;

She seeks but a kind glance from you, I know.

If gazing at her eases not your heart,

How do you view those who take hatred’s part?’

So spoke the lovely maiden in his ear,

But her whole speech was wasted on the knight.

He left her side, most troubled did appear,

And fled through the garden, beyond their sight.

His heart devoid of pity, proud, severe,

Nothing he saw around him brought delight;

He sought to stay within that isle no more,

And made his way, thus, westwards, to the shore.

Book I: Canto VIII: 15-18: The ship bears him to a wooded shore; he confronts a kidnapper

He reached the vessel upon which he came,

And climbed aboard, again its only guest.

E’en shipwreck were better than this shame;

Rather than remain, to voyage seemed best.

Yet the ship appeared scarcely worth the name;

She seemed held fast, increasing his unrest.

He felt he’d rather drown there in the sea

If she moved not, than linger there, unfree.

But the sails, in a moment, filled once more;

She ran before the wind, towards the east;

Faster than eye could follow, on she bore,

From every constraint, it seemed, released;

Until next day she neared a wooded shore,

And, coasting to the land, her voyage ceased.

Rinaldo disembarked; treading the bare

Sand, he found an old man standing there.

The white-haired fellow wept, copiously:

‘Oh, desert me not,’ he cried, ‘sir knight,

If honour moves you, of your chivalry,

Support my cause, and so defend the right.

A brigand snatched my dear daughter from me,

And the false thief is scarcely out of sight,

But two hundred paces off, on the road;

Pursue, and he’ll be hampered by his load.’

Pity moved the valiant Rinaldo,

Who hastened, on foot, and in full armour,

To follow the villain; nor was he slow

To draw his sharp blade as he chased after.

When he came upon the kidnapper, though,

The vile fellow dropped the maid, and rather

Than turn and fight, sounded a huge horn;

To the heavens above its call was borne.

Book I: Canto VIII: 19-24: He fights a giant, and is caught in a net

Rinaldo raised his eyes, and there, on high,

Sited on a headland, looming o’er the sea,

He saw a castle, framed against the sky.

And while that great horn-blast echoed, loudly,

A drawbridge descended, and, by and by,

A fell and wicked giant emerged, slowly,

Measuring a good sixteen feet in height,

That, with spear and chain, threatened him outright.

A hook hung from the loose end of the chain;

And who might guess the purpose of the thing?

While, at once, the monstrous giant was fain

To hurl his spear, that through the air did sing,

To strike Rinaldo’s shield, and not in vain;

It passed through that and his breastplate, piercing

Plate and mail, its passage ne’er denied,

And wounded the knight, lightly, in the side.

Said Rinaldo to the giant: ‘Let us see

Which, of us two, is better with a blade.’

He then attacked the fellow so fiercely,

That the giant, who sought his charge to evade,

Turned his heels, and disengaged swiftly;

Towards the nearby river-bank he made.

Once there, he crossed the bridge that spanned the flood,

Formed of a massive stone, on which he stood;

With his hook and chain, he caught up a ring

Set fast in the slab, and when Rinaldo,

Who was close behind him, and nearing,

Mounted the bridge, in pursuit of his foe,

He twisted the chain, and hauled at the ring,

And opened a hollow space carved below,

Into which Rinaldo fell, calling, loudly,

For aid, to God and the Virgin Mary.

Into the darkness he fell, nor could hear

The river roar beneath him, as he fought

Against the net concealed there, in his fear,

An iron mesh, by which our knight was caught.

Now the giant into that hole did peer,

Extracted him, and the net pulled taught,

And bound him on his back and said: ‘My snares

Catch all who’d interfere in our affairs.’

Rinaldo said naught; to himself he thought

‘Fate heaps one shameful thing on another,

Other folks’ disasters seem as naught,

Compared to mine; woes on woes, forever,

I experience, yet not a one I’ve sought.

There’s scarcely a moment to recover

Betwixt them; tis but endless misery,

Though why tis so remains a mystery.’

Book I: Canto VIII: 25-27: He falls into the clutches of an old crone in Castle Cruel

Such were his feelings as they made entry

O’er the drawbridge to the cruel castle.

Severed heads on spikes showed, eyeless, gory,

While corpses hung high on hooks of metal;

And, further on, darkening our story,

Some seemed to breathe, like disjointed cattle.

Crimson the keep that on that headland stood,

Like far-off flame; it shone with human blood!

Rinaldo now called on his God for aid;

I must confess our knight was filled with fear.

There came a crone, in dark garments arrayed,

Wan of face, and white-haired; she did appear,

Harsh and pitiless; her foul hand she laid

Upon him, and then ordered, with a leer,

The cruel giant to lower him to the ground,

Still enmeshed; then, with a crowing sound,

She declared: ‘Perchance you’ve heard a rumour

Of the savage ways and customs that we strive

To maintain, within this keep; however,

If you have not, while you are yet alive,

(And you shall die at dawn, like every other

Brought here; forsake all hope, you’ll not survive)

I’ll explain the origins of our custom,

The means by which it’s kept, and the reason.

Book I: Canto VIII: 28-34: She tells of the murder of Grifone

There was one a knight of infinite power,

Lord of this fortress, who ruled over all;

He kept a noble court, at any hour

Would welcome passing strangers to his hall.

He honoured visitors to his high tower;

Knights, ladies, worthy folk, on him would call.

And, in his wife, owned to the fairest lady;

She, beyond all others, shone with beauty.

The name of that brave knight was Grifone,

And this keep was then called Altaripa;

His wife, bright as a star, and as lovely,

Was named, and quite rightly so, fair Stella.

Now in the month of May he, frequently,

Would venture forth, in the summer weather,

To hunt in the woodlands by the shore,

Where you arrived this morn, to be sure.

Once, traversing the woods, he found a knight

Hunting there and of his great courtesy,

Invited him to his castle, for the night,

Treating him with honour, and graciously.

This other, who accepted with polite,

And most eloquent speech, was wed to me,

My lord of Aronda, named Marchino;

And he was greeted by the lady also.

Marchino, having seen the fair Stella,

Was seized by a love beyond measure,

Adored that delicate face, and forever

Thought of naught but that noble creature.

And was possessed by the sole idea,

(His heart, thus inflamed by his adventure)

Of stealing the woman from Grifone,

Not loving her, from a distance, only.

The wretched man departed, by and by,

Changed in both looks and demeanour,

And twas he alone knew the reason why.

With a band of his men, he left Aronda,

Clad like Grifone to deceive the eye,

(He resembled him) and, in like manner,

He dressed his force in a deceptive way,

Concealing them midst the woods, that same day.

Then, unarmed, as if he were out hunting,

He traversed the forest, sounding a horn,

Till Grifone heard the echoes ringing,

(For he knew he was hunting there that morn).

Grifone, to that place, soon came riding,

And found Marchino, seeming quite forlorn,

Who, as if he thought the other far away,

Cried: ‘Devil take it, for I’ve lost the prey!’

Then he turned at once, as if catching sight

Of Grifone for the first time, and said:

‘Tis vanished, and my hound was in full flight;

He’s vanished too! Perchance, the rogue is dead.’

The pair rode on, Marchino and the knight,

Until they reached the place, not far ahead,

Where Marchino’s men lay hid, and, briefly,

Grifone was slain, most treacherously.

Book I: Canto VIII: 35-40: And of how she slew her and Marchino’s two sons

Wearing his emblems, they took the fortress,

And few were left alive in that sad place.

Old and young, had no defence or redress,

Especially the women, to man’s disgrace,

Except Stella; with many a fond caress,

Cruel Marchino sought to win her good grace,

But her high heart to him would never yield,

And he was forced, awhile, to quit the field.

She dwelt only on the outrage he’d sought

To perpetrate upon her, and on Grifone,

Whom she had loved most dearly, and she sought

Some path to vengeance, for his cruelty;

Night and day, her husband was in her thought.

Yet she found no means to avenge him truly,

Until the cruellest creature in the world,

Offered her aid, and a dark scheme unfurled.

For on earth there’s no more vicious creature,

None more feared, crueller than a raging fire,

Than a loving wife once scorned; now a monster

Of jealousy, consumed by dark desire.

No wounded lion is ever fiercer,

No trodden serpent is more filled with ire,

As the wife that’s abandoned by her lover,

And sees her lord in love with another.

And such, in truth, was my state, I declare,

For I have never felt a greater pain,

Than when I was first told of that affair;

The hearing of it left me scarcely sane.

The cruelty I showed, what I wrought there,

You may wonder at; if so, learn again

That the well of mercy is oft drained dry,

By jealousy; the innocent may die.

Two infant sons had I, by Marchino.

I slit the first’s throat with my own hand.

The other cried: “For God’s sake, mother no!”

I took him by the feet, as I had planned,

And struck his head against a rock; to know

If my vengeance was complete, you demand?

Why, these vile deeds were only just begun!

Much more remained to do, ere all was done.

I quartered both; when they were well-nigh dead,

I plucked the heart from out each little breast,

And cut their limbs to pieces, while they bled.

Conceive the madness of a wife distressed!

I joyed in my revenge; preserved each head

(No, not from love; no, not with pity blessed)

For a darker purpose, spurred by vengeance still,

Such was the savage fury of my will.

Book I: Canto VIII: 41-43: And of the evil dish Stella served to Marchino

Next, I brought their remains here in secret,

And then set the flesh to grill o’er a flame,

Such spite can do, when upon vengeance set.

First a butcher, then a cook I became.

Their hapless father to the table did get,

And so feasted happily upon the same.

O wicked day! O cruel, unfeeling sun,

That could gaze on this evil I had done.

My exit from the fortress I did win,

(My hands and breast stained with blood) secretly,

And sought Orgagna’s king, for he was kin

To Stella, and had long felt love for me.

And told him all the details of my sin,

And that of cruel Marchino, equally,

And then led that lord, he in full armour,

To seek revenge for Grifone’s murder.

But we both came too late upon the scene,

For after I had crept from the fortress,

Feigning calm, Stella served up the obscene

Conclusion to our vengeance, with no less

Than his children’s heads, both of which had been

Concealed by me in a dish, with grim success,

For though death their sad visages did blight,

Their father knew their features, at first sight.

Book I: Canto VIII: 44-48: And of Marchino’s cruel vengeance on Stella

Stella’s hair was wild, as with altered face,

Triumphant in mind, her revenge secure,

She cried: “Your two dead sons your table grace.

Bury their heads, the rest has passed your maw;

Yourself their tomb, you their dead flesh embrace;

Vile murderer your punishment is sure!”

Now that false traitor knew the depths of pain,

As desire combined with cruelty in his brain.

The immeasurable outrage urged him then

To have her cruelly racked and tormented;

And yet her lovely form he viewed again,

With the heat of desire nigh demented.

He chose vengeance in the end, as often

Fury will, but what revenge presented

Itself, that was commensurate with the deed?

None seemed cruel enough; yet he decreed

That Grifone’s corpse be borne from the plain

Where it lay, and to the blood-stained body

He had Stella bound, the manner did ordain:

Face to face, with both their hands clasped tightly;

And then his pleasure on her did obtain.

Was ever such abuse, or such vile cruelty?

For the corpse was foul, yet the fair Stella

Was raped thus, with the pair bound together.

At last, Orgagna’s king, and I, came there;

With him he’d brought a goodly company.

Though Marchino saw us, he did not spare

The woman, but slit her bare throat, swiftly,

And then used her, dead; the worst he did dare;

Treating her lifeless corpse as savagely

As her living flesh, as if to prove that he

Was as vile a creature as Earth might see.

We fought a bloody fight, and took the keep,

And seized Marchino; his punishment

Was fierce indeed, for he was prisoned deep

In its heart, and flayed there, with harsh intent,

Torn by hot irons that scorched flesh did reap,

His bones shattered, till his last breath was spent.

Stella was entombed within, and, rightly,

Beside her, was laid her dear Grifone.

Book I: Canto VIII: 49-52: And of the creature in the tomb

Then Orgagna’s king departed, while I

Remained here in this darkened citadel.

Nine months had passed already when a cry

Came from the sepulchre, as if from Hell,

A cruel and dreadful screech to terrify

All who might hear and, on the ears, it fell

Of the three giants the king had left with me,

Appalling and scaring them, equally.

One of the three, the boldest, undertook

To open the tomb, and then peer inside,

But soon regretted that one fearful look,

For the creature, imprisoned there, defied

His gaze and, with a claw used like a crook,

Drew him near; in short, the giant died;

For once dragged within, ere his plight was known,

Torn to pieces, he was eaten, flesh and bone.

None was brave enough, within this hall,

To make entry to that vault and its tomb.

I encircled it with a strong and lofty wall,

And, by artifice, oped that stony womb;

A deformed creature, made but to appal,

Came forth; a shape of misery and doom.

Nor need I now describe that thing of woe;

To meet it, as its prey, you soon must go.

For such is the custom that we keep here:

One of our captives is set down each day,

Inside the wall; the creature then draws near,

And consumes the man, without more delay.

We take so many prisoners each year

Some we decapitate, their heads display

Above the castle gate, through which you’ve been;

While some we hang, or quarter, as you’ve seen.’

Book I: Canto VIII: 53-64: Rinaldo fights the monster

Once Rinaldo fully comprehended

The custom’s immeasurable cruelty,

And whence that evil creature descended,

From which no prisoner could win free,

He turned to the crone, lest undefended

He should meet it, and said: ‘Of your mercy,

For God’s sake concede that I may enter

That place with my sword, and in this armour.’

She sneered, and said: ‘Twill prove of no avail!

Yet I’ll allow the armour and the blade,

The monster’s fangs can pierce through plate and mail,

Against those claws, no defence can be made,

Invulnerable its hide; within that pale,

Tis your place to die, although blows you trade;

Yet I’ll happily worsen what lies in store,

The creature makes armed captives suffer more.’

When the sun’s first rays announced the dawn,

Rinaldo was let down within the wall.

From a gate within, the bolts were drawn,

And a creature emerged, as at some call.

Vile and disfigured, from pure evil born,

It snarled, the many watchers to appal,

That stood afraid, and insecure, on high;

While some fled from the sight, or hid nearby.

Rinaldo, alone, showed no trace of fear,

Fully armed, with Fusberta in his hand;

But how the thing’s outward form did appear,

I believe you may wish to understand;

So, concerning its birth, let us be clear,

Twas the devil’s child, and his to command,

Born of Marchino’s seed, left in the womb

Of the murdered wife interred in that tomb.

The thing was larger in size than a bull,

Its long snout was like that of a dragon.

The mouth was three feet wide, and overfull

Of six-inch teeth; the whole a deadly weapon.

The mask was like a wild boar’s; so dreadful

In appearance that none dared gaze thereon,

And from each temple issued a great horn

It could sweep about at will; keen, not worn,

For each sharp horn was like a two-edged blade.

As it moved, it gave out a savage bellow.

Its skin was an unpleasant greenish shade,

Mottled with black, white, red, and yellow.

A thick and bloodstained beard it displayed,

Treacherous eyes, that fierily did glow,

And half-human hands, with nails like talons,

Longer than the claws of bears or lions;

The nails and teeth so strong that the creature

Could pierce through armour plate, and iron mail.

Then, its hide was so hard, and dense in nature,

That it thwarted every weapon, without fail.

Bent on slaying the knight, that dread monster,

Running upright on two feet, sought to impale

Rinaldo on its horns, while the latter

Stood his ground, swinging his sword, Fusberta.

He struck the beast in the middle of its snout.

The monster seemed to blaze with sudden fire,

Then, turning on Rinaldo, it reached out,

One great arm, with intent both dark and dire.

It barely touched him, yet it tore all about,

Sections of his plate and mail stripped entire;

And so sharp were those claws, beyond compare,

They left the knight defenceless, his flesh bare.

Twas insufficient to deter Rinaldo;

He, despite his sore plight, was unafraid.

To its head he delivered a sharp blow,

Two-handed, but the beast ignored the blade.

At each stroke of his, it gave a bellow,

And greater the fierce anger it displayed,

It pounced, and struck at him, with its paws

A mere blur; while it opened wide its jaws.

Rinaldo was wounded in many a place,

Yet no man on this Earth possessed such heart.

Astonished he still lived, he yet would face

Its claws, and seek to tear the thing apart.

To die fighting seemed the lesser disgrace,

And was much the better choice on his part;

He might not slay the thing but, dead, at least

Would not feel himself the object of its feast.

By now the day was dark, the shadows grew,

And still they battled on, in fading light.

Rinaldo gainst the wall, sought strength anew,

Loss of blood had sorely weakened the knight.

But still he swung his sword, the blows yet true,

Though feeling that he fought a losing fight,

For he’d failed to draw a drop of its blood,

Though his sword struck home, be it understood.

His only hope was to render it senseless,

And so, he took a great two-handed swing.

It wrested away his blade, nonetheless.

What could he do? There seemed no escaping

The monster now, and no hope of success,

Lacking Fusberta, against this vile thing.

I’ll tell you the tale of what did follow;

Not here, my lords, but in the next canto.

The End of Book I: Canto VIII of ‘Orlando Innamorato’