Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXXII: Bradamante's Jealousy

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXXII: 1-2: Ariosto’s promise

- Canto XXXII: 3-9: We first return to Agramante and Marfisa

- Canto XXXII: 10-13: And then again to Bradamante

- Canto XXXII: 14-17: She awaits Ruggiero in vain

- Canto XXXII: 18-25: Bradamante’s lament

- Canto XXXII: 26-34: She hears news of Ruggiero and Marfisa

- Canto XXXII: 35-43: And reproaches her lover

- Canto XXXII: 44-48: Bradamante decides to seek vengeance and death

- Canto XXXII: 49-59: The embassy of the Queen of Iceland

- Canto XXXII: 60-68: Bradamante learns of Tristan’s Tower

- Canto XXXII: 69-74: She seeks lodging there

- Canto XXXII: 75-81: She defeats the three kings in joust, and reveals herself

- Canto XXXII: 82-95: The history of Tristran’s Tower

- Canto XXXII: 96-100: The least beautiful lady must leave the Tower

- Canto XXXII: 101-106: Bradamante challenges the judgement

- Canto XXXII: 107-110: And wins the argument

Canto XXXII: 1-2: Ariosto’s promise

I recollect my pledge that I would sing

(The promise made it somehow slipped my mind!)

Of a dread suspicion destined to bring,

To one whom jealousy now rendered blind,

(Bradamante, I mean) much suffering;

Sharper its sting than is Love’s dart she’d find;

For what she had heard from Ricciardetto,

Plunged to her heart like a poisoned arrow.

So, was I pledged to sing, but sang another,

For brave Rinaldo arrived, ere I did so,

And then was delayed by his half-brother

On the way, one Guidon Selvaggio;

And so ran on, only to discover

That Bradamante’s ills I’ve failed to show.

I recalled her but now; of her you’ll hear,

Ere Rinaldo and Gradasso reappear.

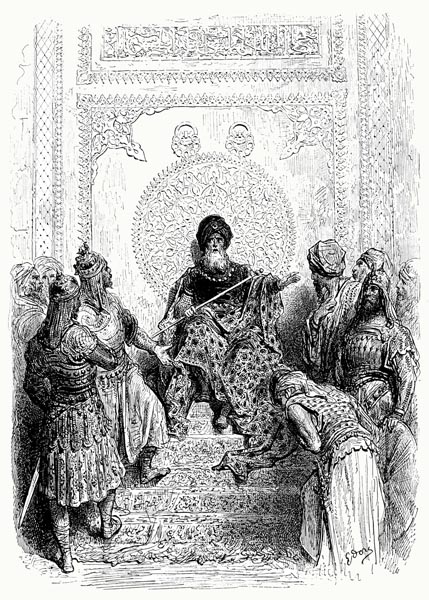

Canto XXXII: 3-9: We first return to Agramante and Marfisa

But tis needful, ere I speak of the maid,

That I give you news of Agramante.

He had, successfully, to Arles conveyed

The remainder of his scattered army,

A useful place to grant them food and aid,

And muster them after their long journey,

On the banks of the Rhône, and nigh the shore,

With Spain not far, and Africa before.

Marsilius meanwhile scoured all his land,

For cavalry and infantry, good or bad,

And armed his ships on Barcelona’s strand,

Persuading some by force; all that he had.

Agramante, with his council e’er to hand,

Spared neither cost nor labour, I may add,

While heavy taxes, and harsh levies, weighed

On Africa, that good his losses made.

He now wished Rodomonte at his side,

Offering him, in vain, Almonte’s daughter,

(She was his cousin) as a noble bride,

Oran her dowry in Algeria.

But he, defending now his bridge, with pride,

Cladding with the spoils of death and capture

The sepulchre’s stone walls, refused to move,

While one more passing knight he yet might prove.

Marfisa had sought the opposite course

To Rodomonte; indeed, when she heard

Of the success of Charlemagne’s force,

The army dead or scattered, and had word

That her king was at Arles, she took horse

And, unsummoned, she to that city spurred.

Offering her skills, and her wealth, to aid

Agramante, and the troops there arrayed.

As a gift, she had brought him Brunello,

Nor had she harmed him in any way,

Although for ten nights the wretched fellow

Had lived in fear of being hung next day;

And while, to his every groan and bellow,

None responded, howe’er hard he did pray,

She disdained to dip her hands in base blood,

And let him loose, to manage as he could;

He, pardoned for the harm he had done her,

To Arles, and Agramante, was conveyed.

You may imagine that monarch’s pleasure

And with what delight he welcomed the maid.

Wishing to show how much he must treasure

Her assistance, once her account she’d made.

The deed which she had said she wished to do,

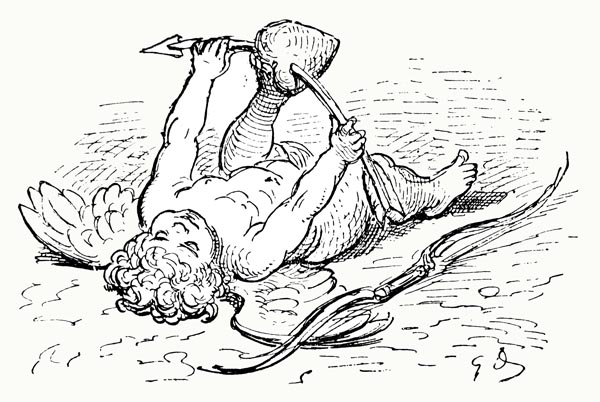

To slay the wretch, the king did now pursue.

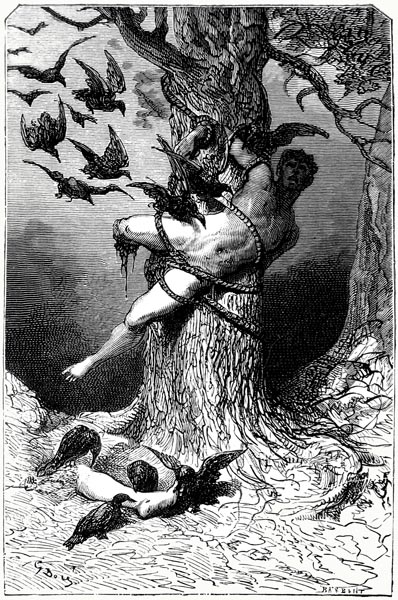

He hung the villain in a barren place,

To suffer the crows’ and vultures’ abuse.

Ruggiero who’d protected him a space,

And might well have saved him from the noose,

Yet lay, his wound unhealed, pale of face,

In his bed, without power to cut him loose.

By the time the news was out, twas too late,

For Brunello, friendless, had met his fate.

Canto XXXII: 10-13: And then again to Bradamante

Meanwhile Bradamante grieved, complaining

That the term of twenty days seemed so long,

At the end of which Ruggiero, returning,

Would, once more, to the Christian faith belong.

To the prisoner or the exile, yearning,

The time drags no less, while no less strong,

Is their pain, as they pine for liberty,

Or that their lost homeland they might see.

And she thought her own fate to be far worse

Than that of Tityus, or Ixion

Bound to a wheel his endless days to curse;

Or Pirithous, ere the time was gone;

Far longer than the day Job did rehearse

Heaven’s injustice, patiently, thereon.

The night wherein Hercules was conceived,

Could ne’er have proved so long, she believed!

Oh, how often that slumber, long and deep,

She envied in the hedgehog, dormouse, bear,

Wishing she could but pass the time in sleep

Until the term was done, and he was there;

Nor wished to hear aught, nor watch to keep,

Till Ruggiero came, his love to share.

Yet not only was this beyond her power,

She failed to sleep at night beyond an hour.

Here and there she squirmed about instead,

Tossed and turned, and never found repose,

Oft oped the window, and thrust out her head,

To see, ere she returned to hers to doze

If Eos soon would leave Tithonus’ bed,

Her arms filled with the lily and the rose.

Nor did she less, in the bright glow of dawn,

Long for the stars, to darkened skies re-borne.

Canto XXXII: 14-17: She awaits Ruggiero in vain

When but four days, or five, were yet to go

Until the term was ended, she awaited,

Full of hope, a message, from the gate below,

Saying: ‘Behold. he comes!’ never sated

With gazing from a tower, whose height did show

The woods and countryside, cultivated

Fields and, beyond, a portion of the road

That led from France to her lonesome abode.

When she saw a glint of armour draw near,

Or aught that might betoken a knight,

She though it her Ruggiero, her dear,

And then her lovely eyes were filled with light.

If one, unarmed, on foot, should next appear,

She trusted his messenger loomed in sight,

And, though she would find herself in error,

But replaced one (failed) hope with another.

Then she would arm, and go to meet him,

Descending from the mountain to the plain,

Yet found him not and, hoping to greet him,

Thought by another route he must attain

The castle, and so made her way to him,

To welcome him there, yet all in vain,

For she found him in neither place, and so

The term he’d set passed at Montalbano.

It passed, and then a day or two went by,

And three, and more, till twenty days had flown.

Without a trace of him before her eye,

Nor any news of Ruggiero known.

She sighed aloud, and bitter tears did cry,

Enough to move the Furies with her moan,

They from whose brow vile serpents glare,

And beat her breast, and tore her golden hair.

Canto XXXII: 18-25: Bradamante’s lament

‘Can it be true,’ she cried, ‘that I await

One who seeks to fly and hide from me?

And prize a man that cares naught for my fate?

One that answers not, and but disdains me?

And let one hold my heart that proves ingrate?

A knight that ranks his virtues so highly

That some immortal goddess needs descend

From the heavens, his loveless will to bend?

He knows of my love, nay adoration,

Yet desires not my service, nor my love;

Knows of my pain and deprivation,

And yet would see me to my grave remove,

Ere he would aid me; to my vexation

Lest to him an obstacle it might prove,

Lends not an ear, as if I were an asp

Whose hissing he’d not hear, nor body clasp.

Love, halt this lover who runs so swiftly

From one that with slow steps seeks to pursue,

Or to my former state now return me,

Where I was slave to neither him nor you!

My hope is foolishness, mere fallacy,

That you are ever moved to pity, who

Take delight in, nay live and feed upon

The tears when a fond lover weeps thereon!

And yet, what reason have I to lament

Except my own irrational desire,

That sends me soaring, with a wild intent,

To the heights, where my wings are set afire,

Then, weary, with no lesser flight content,

Sees me fall, from the air, to my sad pyre;

Nor ends my woe, on new wings has me fly,

But to scorch, and plunge again from the sky?

Of myself, and not desire, I should complain,

This burning ardour that consumes my heart,

Whereby reason from my weak form is fain

With all my other powers to depart.

So that unbridled, freed from bit and rein,

From bad to worse I flee, past wit, or art,

And makes me feel that to vile death I’m led;

Through this delay, awaiting greater dread.

Ah, and yet why should I grieve also?

What fault, except to love, did I commit?

What wonder if, through weakness, all this woe

Women bring upon themselves stole my wit?

Yet why defend myself lest noble foe,

With wise words, and fair form, engender it?

Should I protect myself lest harm be done?

Wretched are they that scorn the living sun!

And, besides, my destiny this path ordained,

Led by others’ words, full worthy of belief,

That claim rare happiness shall be attained,

And such must recompense all passing grief.

If Merlin’s counsel was but ill or feigned,

And naught but sorrow here and scant relief,

I might lament, and blame him for my pain,

Yet ne’er love for Ruggiero hence disdain.

I should blame them, Merlin, and Melissa,

And condemn them both, eternally,

Who to reveal a House and its future,

Conjured spirits from the depths, infernally,

And then fed my foolish hopes, thereafter,

To keep me ever bound in slavery;

And why? If not through envy, I suppose,

Of my secure, and sweet, and blest repose.’

Canto XXXII: 26-34: She hears news of Ruggiero and Marfisa

Sorrow so occupied the maiden’s mind

It left no room for comfort or for rest,

Yet, despite her misery, Hope, though blind,

Still found a silent lodging in her breast;

The memory of him for whom she pined

And his last words so lovingly addressed

To herself, left her, despite his lateness,

Waiting, hour upon hour, for Love’s redress.

It was hope, therefore, that thus sustained her

For a full month beyond the twenty days,

Such that the troubled spirit within her

Was ne’er grieved quite as deeply, nor her gaze;

Yet ill news now made its way towards her,

By the road where she looked for him always;

Of him it told, and yet it brought such dread,

As painful as the last, that Hope now fled.

For a Gascon knight passed by, returning

From Agramante’s camp, a captive there

Since the fight before Paris, and sharing

His news he brought the lady to despair;

She had prayed him to tell her everything

That he knew, although it be full of care,

Yet asked but of Ruggiero, her lover,

And barely took note of any other.

The knight gave good account of all he knew,

Being one well acquainted with the court,

And spoke of how her Ruggiero slew

Mandricardo, as o’er the shield they fought;

How, wounded, from the field he made issue,

And lay a month half-dead, the outcome fraught;

And had he ended there, had shown, I’d say,

Sound reason for her lover’s long delay.

But then he added that a warrior-maid

Was in the Moorish camp, named Marfisa,

As beautiful as she was brave, who played

A valiant role indeed, and fought with ardour;

And she loved Ruggiero, and he paid

Her like attention, so oft beside her

That all, amidst the Moorish host, now thought

That they must soon be wed, and such they sought,

Hoping that once Ruggiero was healed,

The marriage of the two would soon follow;

And every Moorish king and prince revealed

Their delight at that fair prospect, for so,

Given their peerless valour in the field,

On the world a great House they might bestow,

In a brief while, warlike, ardent in war,

Mightier than any on this Earth before.

The Gascon had believed all that he’d heard,

And with good reason, for amidst the host

Such was the rumour, such the constant word,

Within the camp, and e’en along that coast.

From many a sign, all who saw concurred,

Till it appeared more than rumour almost,

Rumour which is, for good or ill, once bred

In one mouth, by many another spread.

That she, like Ruggiero, sought to aid

Their king, the pair but seldom seen apart,

Had helped to breed suspicion, and had played

Its role in fuelling rumour, from the start,

But what seemed to confirm it, and thus made

All certain, was, or so felt every heart

The fact that, having carried off Brunello,

It seemed she’d returned to tend Ruggiero.

Solely for him, who languished, wounded, there,

She had come to the Moorish camp, it seemed,

And, not just once, but often, would repair

To his sick-bed, until the pale moon gleamed;

Which gave occasion for the troops to share,

Their view that she, who proud and high was deemed,

And one that disdained all those beneath her,

Was, for him alone, humbler now and sweeter.

Canto XXXII: 35-43: And reproaches her lover

Since the Gascon knight claimed the tale was true

Bradamante was possessed by such deep pain,

The dart so pierced her heart, through and through,

That she could scarce an upright stance maintain,

And then, inflamed with jealousy anew,

Wheeling round, without a word, turned again

Full of disdain and anger, all hope lost,

And to her chamber went, to count the cost.

Mail-clad, she flung herself upon the bed;

Her face she buried there, as sore she grieved;

Biting the sheets that naught might yet be said,

And none suspect the fact she now believed,

While repeating the news lodged in her head,

Till such woe filled a heart perchance deceived

She could no longer her sad plaint restrain,

Forced to voice all her suffering and pain.

‘Alas, who can be thought true, from this day!

All men are false and cruel, I declare,

If, false and cruel, Ruggiero doth betray

Our love, whom I thought loyal, full of care.

What villainy, what treachery, I say,

Is heard in tragedies that players share,

That is not lesser if, in thought, is set

My noble worth against his endless debt?

Why, Ruggiero, since there exists no one

More ardent or more handsome to be seen,

Or that approaches you in valour, none,

Nor in grace nor nobility, I ween,

Why should loyalty be the grace you shun,

And steadfastness be absent from the scene?

Why is it that these two you disavow;

To which all other virtues yield a bow?

For, know you not that lacking both those two,

All nobility proves worthless, in a knight?

Just as there is naught lovely to the view

That is perceived without the help of light?

Tis easy some poor maid to draw to you,

Her lord, divine, an idol in her sight,

With cunning speech, and make her heart conceive

The sun is cold and dark, and such believe.

What crime can e’er trouble you, cruel lover,

If of her murder you shall ne’er repent?

If, so lightly, you view the sin, moreover,

Of breaking faith with one so innocent?

What dire ill-treatment must your foes suffer,

If I, who love you, you would thus torment?

Justice lies not in Heaven I declare

If such wrongs high Heaven doth not repair!

Of all the sins committed here below

Impious ingratitude is far the worst,

And, for that, the fairest angel, as you know,

Was banished to the darkness, and accursed.

And if great errors earn the deepest woe,

And cannot be amended, like the first,

Beware lest deepest vengeance fall on you,

Ungrateful, thus, yet unrepentant too!

And of theft, I accuse you, cruel man

That grieves me, besides your other vice;

Not of stealing my poor heart, a fine plan;

For that I pardon you, not once, but twice.

Rather I say that once our love began,

You stole yourself from me, by ill device.

Wretch, restore my heart, tis not your toy,

For what some other holds none can employ!

You depart from me Ruggiero, and yet I

Have not the will or power to quit you;

But to leave all pain and grief, and to die,

That strength I own, and the longing too.

And yet, without your favour, so to fly

From sorrow, makes me but lament, anew.

If the gods required it, and you loved me,

Then death, indeed, would seem but sweet to me.’

Canto XXXII: 44-48: Bradamante decides to seek vengeance and death

And, so saying, she was for death disposed.

Leaping from her bed, inflamed with anger.

Against her breast her naked sword she posed,

Ere she recalled she was clad in armour!

But then the better spirit that lay enclosed

Within her mind, reasoned: ‘Oh, fair sister,

Born to such high lineage, that great name

Would you yet mar, and end your days in shame?

Is it not better to that field to go;

On which you may win both praise and honour?

There, if you fall to Ruggiero’s blow,

He must repent of slaying, you forever.

And if it were his sword that laid you low,

Then what death could suit your purpose better?

Tis reasonable if he robs you of life

That condemns you, living, to pain and strife.

And then, perchance, before you must remove,

You may take vengeance on this Marfisa,

That with fraudulent and treacherous love

Has seduced your lover; and destroy her.’

This thought of revenge seemed to prove

More pleasing to the lady, who, moreover,

Chose to weave a surcoat, that would imply

Her desperation, and her wish to die.

The surcoat was of that tawny colour

That dyes the autumn leaves before they fall,

Scattered from the branches, in November,

That made the woods appear a living wall,

Embroidered with cypress sprigs all over,

Sad emblems to adorn a noble pall,

(That tree once bared will ne’er recover)

The garment suited to a grieving lover.

She took the charger that Astolfo rode,

His golden lance as well, whose touch alone

Would relieve a knight’s courser of its load.

Perchance the story is already known,

Why he gave it her, where and when bestowed,

And from whom he obtained it for his own.

The maiden took the lance, yet little guessed

The nature of the power that it possessed.

Canto XXXII: 49-59: The embassy of the Queen of Iceland

Alone, without a squire, or company,

She descended the hills, and took her way

To Paris by the straightest road, and swiftly,

Thinking the Saracens before it lay,

Not having heard yet that the enemy,

Routed by brave Rinaldo (helped, that day

By Malagigi and King Charlemagne)

Had abandoned the siege, and fled the plain.

Quercy lay behind her, and the city

Of Cahors, with all the mountains where

The Dordogne is born (tis the country

Of Clermont, and Montferrand the fair)

When she met, on the way, with a lady,

Of a kindly face, who her road did share;

And by her saddle hung a golden shield,

While three brave knights at her side, held the field.

Before her, and behind, many a squire

And many a maiden kept her company,

And Bradamante expressed her desire

To one that passed, to learn of the lady.

He replied: ‘She, of whom you thus enquire,

Comes to the French king, on an embassy,

From nigh the northern pole, many a mile

She has sailed, o’er the sea, from the Lost Isle,

Though others say that Iceland is its name,

That far island, of which its lovely queen

Excels all other beauties known to fame,

For Heaven gave her charms ere now unseen.

To Charlemagne she sends a shield (that same)

Upon condition that he should convene

A muster of his knights, and grant it there

To whichever, to his mind, is past compare.

She deems herself and, in truth, is fairest

Of all the ladies there have ever been,

And so would find the mightiest and bravest

Of warriors, one fit to wed this queen;

And thus, she is resolved to seek the best,

E’en though a hundred thousand haunt the scene.

The man most famed in fight with lance and sword,

She desires as her lover and her lord.

She hopes there may be found at the court

Of France’s Charlemagne, a noble knight,

Who has proved himself where’er he fought,

The best of those of whom the king has sight.

The three that do the lady here escort,

Rule mighty realms, each one a king, of right,

The lords of Gothland, Sweden, and Norway;

Few equals there in arms, or none, have they.

These three whose lands are far from hers, although

They are the closest ones to her Lost Isle,

(So called because few sail those seas, or know

Of that island, distant many a mile)

Have wooed, and woo her yet, and often show

Their valour in the fight, to win her smile,

For they have done many a deed to please her,

That, while the sky turns, we’ll speak of ever.

And yet the queen will have none of these three,

Nor any that is not the best knight known.

‘I hold as naught the deeds you do for me,

In this benighted place; though one alone’

She says, ‘a shining sun might seem to be

Matched against the other two, I’ll not own

That he could boast of being the best knight

Of all who carry arms, and wage a fight.

To King Charlemagne, whom I honour

And esteem as the wisest king of all,

A golden shield I’ll send, a rich favour

To be granted to the knight in his hall

He considers the best in strength and valour,

Of the many upon whom he may call.

Whether knight or vassal or some other,

It shall be the monarch’s choice however.

When King Charlemagne has received the shield

And granted it to one so brave and strong

That to him all others (he believes) must yield,

Though to his court or not he may belong,

Then regain, one of you three, in the field,

That golden targe, before the noble throng;

All my love, and realm, to him I’ll afford,

And he shall be my husband and my lord.’

Her closing words thus caused these lords to sail

Across the sea, from that far distant land,

To fight for the shield, seeking to prevail

Or die, gainst he who grasps it in his hand.’

Bradamante listened to the squire’s tale,

Then mused on the contest thereby planned,

While he sat his horse, stirring restlessly,

Then spurred it, and re-joined his company.

Canto XXXII: 60-68: Bradamante learns of Tristan’s Tower

She followed them, though scarcely hastening,

For twas but slowly she pursued her way,

Upon the fight for the shield pondering,

And on what might occur in that affray,

And, in sum, could see the matter bringing

Great discord to fair France, and disarray,

Amidst the king’s paladins, and the rest,

If he must grant the shield, thus, to the best.

Indeed, the thought weighed greatly on her heart,

Though another burden proved the greater

The fear that Ruggiero, for his part,

Had transferred his love to this Marfisa.

It so occupied her mind, that bitter dart,

That she barely saw the road, forever

Straying so, and despite the fading light,

Scarcely caring where she might spend the night.

Like a vessel that, by chance, or by a gale

Is driven from the river-bank, and ever

Drifts about, at the whim of wind and sail,

While lacking its customary master,

So, she wandered, far and wide, o’er hill and dale,

Her mind and heart absorbed, and, wherever

He wished, she was borne by Rabicano,

While lost in thoughts of her Ruggiero.

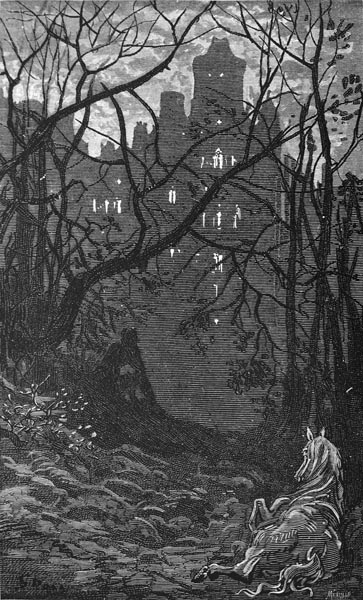

She raised her eyes, at last, and saw the sun,

Had turned his back on Mauretania,

Then, like a cormorant, his journey done,

Had plunged, beyond Morocco, to the water;

And that twas foolish now for anyone

To be lodged out of doors, without shelter,

For a blustery wind began to blow,

One chill enough, that eve, to threaten snow.

She, therefore, urged her mount to greater speed,

And had not gone much further ere she saw

A shepherd with his flock (that there did feed)

Bent for the fold, driving his sheep before.

The maiden-warrior told him of her need

For lodging, no matter how ill or poor,

Since never was there lodging e’er decried

That proved less pleasant than a night outside.

The shepherd answered her: ‘I know of none,

That I could point to you, that is nearer

Than six leagues from this place, but for one,

That the folk hereabout call Tristan’s tower;

Though not readily, there, is entrance won,

For, lance in hand, and in grave encounter,

Prepared to hold their ground, and to defend,

Must those knights be that entry there intend.

If, when a knight arrives, the tower is empty

But for its castellan, the knight may stay,

But if another knight appears, then swiftly

The former must despatch him on his way.

If none appears, the knight may rest easy,

Else, the lance and sword must set in play,

For whoever’s bested in the joust, say I,

Must yield their place, and seek the open sky.

Should two or more knights arrive together

They are allowed to dwell there in peace,

While if they’re followed by a lone stranger

His task must, correspondingly, increase.

If but the one is lodging there, moreover,

He must joust with two or more, ere they cease,

Should that number appear later; therefore,

Great valour’s needed to approach that door.

No less if wife or maid approach the tower,

Whether they’re alone, or in company,

And another should arrive, then the fairer

May remain, yet not the other, sadly.’

Bradamante now sought to know further

Where this brave tower was, and he, gladly,

Described the place, pointing with his hand

To where, six miles away, the keep did stand.

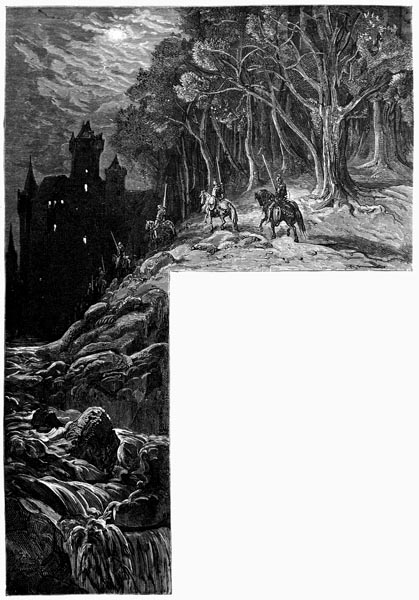

Canto XXXII: 69-74: She seeks lodging there

The lady, though Rabicano went well,

Had no heart to drive him any faster

Along that broken path, nor magic spell,

(The surface rendered worse by the weather)

So as to reach it first, ere evening fell,

And thus darkened all the world around her.

Arriving there she found the door was barred,

Yet she asked a night’s lodging of the guard.

He answered that the place was occupied

By three knights, and a lady, come before,

Who were seated now, about the fire-side,

And awaiting their supper, to be sure.

‘I doubt the meal is ready,’ she replied,

‘If these three knights but lately passed the door,

Go say that I attend their presence, here:

They, as your rule decrees, must now appear.’

The guard bore his message to the place

Where the knights were seated, at their ease.

They, obliged now to fight outside, and face

The wintry weather, it did much displease.

A heavy rain had fallen for a space,

And was it seemed unlikely now to cease;

They donned their armour slowly, then the rest

Remained within, while they their task addressed.

They were the three knights, most fine and worthy,

(For few were, in this world, worth more than they)

Bradamante, had met, with the lady,

On the open road, earlier that day,

The three who’d, in Iceland, boasted bravely,

That the golden shield they would bear away,

Who, by pursuing their path more swiftly,

Had arrived there before Bradamante.

Of all the folk in arms few were better,

Though Bradamante among those made one,

Nor would she remain to brave the weather,

Wet-through and cold, when all was said and done.

Those within at the windows chose to gather,

To peer at the course the knights must run.

Though the moon’s rays often pierced the cloud,

Yet the rain sheeted down, a murky shroud.

As a welcome lover’s filled with delight

Seeking entry to the furtive realms of love,

When, at last, they hear the bolt in the night,

Nigh-on silently, in its socket move,

So Bradamante, who desired to fight

These three, and their skill and mettle prove,

Rejoiced, when she heard the door flung wide,

The drawbridge lowered, and the three descried.

Canto XXXII: 75-81: She defeats the three kings in joust, and reveals herself

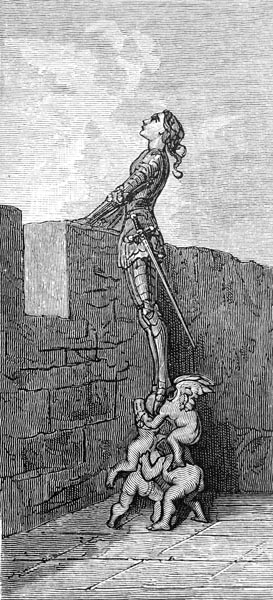

As soon as they had reached the open field,

Together (or with no great space between),

She turned her valiant steed aside, then wheeled,

And charged, full speed, across the darkened green,

Lowering Astolfo’s gift, that had sealed

Many a knight’s fate (that fey lance I mean)

That would unseat, its power being such,

Even Mars himself, with a single touch.

The King of Sweden was the first she met

And, thus, the first to topple to the ground,

Such the touch of the lance on his helmet,

The unfailing spear ever strong and sound.

Gothland’s king was next, a slighter threat,

Who feet in air, at some distance, might be found.

The third king was left gasping, upside-down,

Half-buried in the mud, and like to drown.

Once she’d dealt each of the three a fierce blow,

Their heads now on the earth, their feet in air,

She rode to the tower, which thus did owe

Her lodging, though indeed obliged to swear

That she would issue forth if one did show

That sought the same, and so do battle there.

Its lord within, a witness to her valour,

Now welcomed Bradamante with honour,

As did the lady who’d arrived that night

With the three, who’d journeyed as I said

From the Lost Isle to seek the finest knight

At France’s court, sent by a queen unwed;

Courteously she welcomed her, on sight,

Being gracious, and kind, and nobly bred,

Rising to greet her, calmly and serenely,

Then leading her to stand near the chimney.

Then she began to remove her armour,

First taking her helmet and her shield,

But, when the helmet was off, a cluster

Of golden tresses was at once revealed,

That fell, in a cascade, to her shoulder,

The maid within the armour unconcealed;

And a maid no less lovely to the eye

Than fierce in battle, none there would deny.

As when the curtain’s raised o’er the stage

And a thousand lamps or more light the scene,

With many an arch and tableau (all the rage!)

Statues, paintings, perchance a gilded screen;

Or when the bright sun deigns to disengage

From the clouds, and show a face all serene;

So, as she doffed her helm, before their eyes

Each gained a sudden glimpse of paradise.

Those lovely tresses that the hermit sheared

Had now re-grown, though shorter than before,

And gathered in a knotted coil appeared,

Behind her head, free of the helm she bore,

While the lord of the tower, as she neared,

(He had viewed her in former times) now saw

Twas Bradamante, and more warmly then,

He welcomed her, and honoured the maiden.

Canto XXXII: 82-95: The history of Tristran’s Tower

With simple and pleasant conversation,

Seated before the fire, their minds were fed,

While, to nourish their bodies, a collation

Was brought to them, a light but tasty spread.

Bradamante, seizing the occasion,

Asked if the custom were but newly-bred,

To which she had adhered, or when and where,

And by whom, it had been established there.

‘In olden days, when Faramund was king,

Replied the warden, ‘Clodion, his son,

Had a mistress, more beautiful and pleasing

Than any woman in that age, bar none.

And he loved her deeply, no more losing

Sight of her than Io’s watchful guardian

His charge; for his jealousy waxed as great

As his love, and seclusion was her fate.

Here he kept her (for this tower, his father

Had granted him) and rarely went abroad;

Ten proud knights lodged here with him, moreover,

The best in France, set to defend their lord.

To this keep came Tristan with another,

A fair lady, whose rescue he’d ensured,

For, from the savage grip, he’d released her

Of a fearsome giant who had seized her.

They arrived when the sun had retreated

From Seville, and all the land of Spain,

Hoping with fair welcome to be greeted,

(For ten miles around naught else graced the plain)

But jealous Clodion, though entreated

To grant them lodging there, ne’er would deign

To permit a strange knight to lie therein,

Who acquaintance with his lady might win.

When despite his request, oft repeated,

He was still denied entry to the tower,

Tristan cried: ‘I yet hope, undefeated,

Despite you, to demonstrate my power.’

And Clodion, and his knights, he greeted

With a challenge, to fight that very hour,

Offering, with lance and sword in hand,

To mark him with Discourtesy’s vile brand,

And, if he should unseat them, villains, all,

While in the saddle he did yet remain,

The lady and he would lodge in the hall;

Let Clodion, and the rest, enjoy the rain.

So as not suffer shame, at this bold call,

Prince Clodion and the ten sought to maintain

Themselves against one man alone, but Fate

Saw them fall; and Sir Tristan barred the gate.

On entering the tower, he found the maiden,

So dear to Clodion and passing fair,

Wrought so by Nature, the gift so given

Not one She grants to maidens everywhere.

They spoke, as, by fierce jealousy riven,

Clodion hammered at the gate, in despair,

While begging and praying that the knight

Would grant him his lady, now, outright.

Tristan, though not prizing her as deeply,

For none but Iseult could win his heart,

(He’d loved not, nor embraced, another, truly,

Since the potion had worked its magic art)

Yet would avenge the vile discourtesy

That Clodion had shown, so, for his part,

Replied: ‘Twould be wrong it seems to me,

To deny this tower to such rare beauty;

Since you grieve, sorely, in the open air,

Beneath your tree, and company demand,

There is a maid, perchance not quite as fair,

Though she is young and lovely, close to hand,

And I would rest content were she to share

Your lodging, and obey your least command.

Yet the most beautiful, I think, sir knight,

Should belong to the best man in a fight.’

Clodion, excluded, discontented,

Huffed and puffed, about the tower, all night,

As if he were guarding the contented

Residents who slept there, out of sight.

More than the cold and wet, he resented,

His lady’s bold retention by the knight,

Yet, in the morning, Tristan, moved by pity,

Ended his woes, and restored the lady.

And said to Clodion, and made it clear,

That he now returned her as he’d found her.

Twas reason for shame, he told the peer,

That grave discourtesy, shown earlier,

Yet he was content he’d spent a drear

Night outside, contending with the weather;

Though Love was scarce an adequate excuse

For his offering a stranger such abuse,

For Love should render an ill nature kind,

And not achieve the contrary effect!

Long enough Clodion remain behind

Once Tristan had departed, to select

A knight to keep the tower (who, to his mind,

Was welcome to it) one sworn to reject

All requests for lodging made at random,

Unless they accorded with this custom:

That the knight that was of greater power,

And the fairest lady, might there remain,

While any lesser guest must quit the tower,

And lodge outside it, in the wind and rain.

Thus, the rule, that has lasted to this hour,

He fixed, and we the custom yet maintain.’

While the lord of the tower told his tale,

A meal was prepared, on a larger scale.

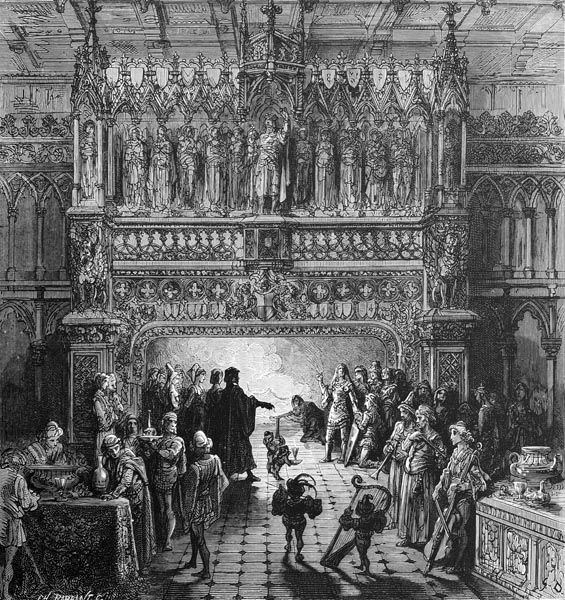

In the great hall the tables had been laid,

No finer chamber has there ever been,

And to it the two ladies were conveyed,

By the light of torches, nor had they seen

Aught so fine; Bradamante now surveyed,

As did the other lady, that fair scene,

Where noble paintings there adorned the hall,

Rather than tapestries on every wall.

Canto XXXII: 96-100: The least beautiful lady must leave the Tower

So fine were the paintings that they marvelled

At the art, and scarcely thought of dinner,

For there was little further they needed,

Wearied by the long day past, moreover.

The servants saw their plates went unheeded,

And the food untasted, though the master

Cried: ‘Come, tis surely better, if you’re wise,

To feed the stomach first, and then the eyes!’

The company were seated at the board,

When, all at once, the master realised

That to lodge them both was scarce in accord

With the custom of which they’d been apprised.

Room for the loveliest he must afford,

While the other faced the wind and rain, despised;

Since they had come there separately that day,

One lady must depart, the other stay.

He summoned two sage elders to the hall,

And the women of the household likewise,

Then asked, when they had hastened to his call,

Which lady was loveliest, to their eyes;

After gazing at the two, one and all

Said Bradamante best deserved the prize;

And no less in beauty outdid the other

Than she had surpassed the kings in valour.

To the Icelandic lady, who’d surmised

The outcome of the matter, he then said:

‘Lady, that the custom was so devised,

Is scarce our fault, we must refuse a bed

To one of you, and you are best advised

To seek for one elsewhere, for it is clear,

That, unadorned, she’s yet the fairer here.’

As, in an instant, a dark mist will rise

From out a rain-drenched valley to the sky,

Veiling the sun’s bright face from our eyes

So, from that lady issued a deep sigh,

Clouding her face, that she must realise

The cruel sentence; cold and rain thereby

Her lot; with altered look she was no more

That lovely lady she had seemed before.

Canto XXXII: 101-106: Bradamante challenges the judgement

The colour fled from her visage, dreading

To face the darkness, while Bradamante

Full of pity, and opposed to her going,

Cried: ‘It seems to me that little mercy

Accompanies all such judgements, lacking

True justice, indeed, where ere a hearing

In which opposing arguments are weighed

The court’s decision is already made.

I, that now take upon myself her cause,

Say this: ‘That however fair I may be,

I came not as a woman to your laws,

Nor would be judged as such, assuredly;

And can you say, and this should give you pause,

That naked I am less or more than she?

For what we know not we should not assert,

And least of all if others may be hurt;

Many another wears their hair as long,

And yet is not a woman. You now know

Whether, fighting here, I proved as strong

As any, and could deal an equal blow;

Then why should I to womanhood belong

To suit your custom, and be treated so?

You law is that a woman shall lose place

To a woman, not a knight kings must face.

Let us assume I am, as you believe,

A woman (though I here concede it not)

And less than her in beauty (so conceive)

Would you then, all my chivalry forgot,

Drive me from here, and this fair maid receive?

Twould be less than justice, were such my lot:

To lose, through lack of beauty, what was won

By conquering, in the field, as I have done.

And though tis your custom that the lady

Who is of lesser beauty must depart,

Though ill might come of my obstinacy

I would insist on staying, for my part.

An unequal contest it seems to me,

Twould be, and a judgement lacking heart,

For in such a matter she has much to lose,

And I little to gain, if thus you choose.

And if unequal be the loss or gain,

The contest is undoubtedly unfair,

So that, as of right (I do here maintain)

If not courtesy, the lady must share

Our lodging, and if any would again

Challenge my conclusion, then let them dare

Take the field, for I’ll there uphold my cause,

Decrying the injustice of such laws!’

Canto XXXII: 107-110: And wins the argument

Thus, Bradamante, moved to pity,

That such a noble lady should be wronged

And driven forth to shelter neath a tree

From the blustery showers (which were prolonged)

Persuaded the lord to show her mercy

And concede that she was where she belonged.

Especially her last words were in his thought,

So, he proved content to yield, and say naught.

When a plant, in the burning summer heat,

(Well-nigh parched, and so thirsting for water,

Sap ebbing in the stem once full and sweet,

And close to withering its fair flower)

Shakes its leaves, the welcome rain to greet,

So, after that defence, the messenger

Appeared revived, and showed her delight,

And seemed as lovely as before, to the sight.

The dinner which had long been neglected,

Being heated once more, they now enjoyed.

With no further knights-errant expected,

They were, at last, more pleasantly employed.

All but Bradamante, who rejected

The thought of food, or at best but toyed,

Still plagued by the suspicions, doubts, and fears

That robbed her of the joy shown by her peers.

When the meal was done (though rendered shorter

By their desire to feast their eyes once more)

She rose to her feet, Amone’s daughter,

And, after her, the queen’s ambassador.

A servant ran, at the warden’s order,

To light the torches that the chamber bore,

Shedding splendour on walls, and floor as well;

Of what followed, the next canto must tell.

The End of Canto XXXII of ‘Orlando Furioso’