Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXXI: Fiordelisa and Brandimarte

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

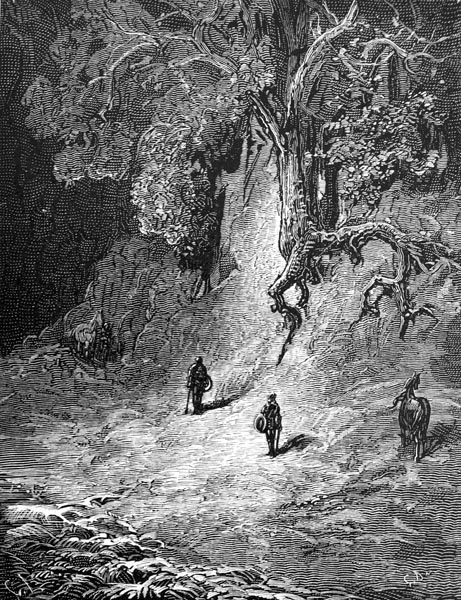

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXXI: 1-7: Ariosto on Jealousy

- Canto XXXI: 8-12: Rinaldo’s company encounter a knight

- Canto XXXI: 13-17: Rinaldo fights and the stranger’s horse is slain

- Canto XXXI: 18-22: They continue to match swords on foot

- Canto XXXI: 23-27: They cease for the night, and Rinaldo offers hospitality

- Canto XXXI: 28-33: They identify themselves to each other

- Canto XXXI: 34-36: Guidon joins their company

- Canto XXXI: 37-40: They meet Aquilante and Grifone

- Canto XXXI: 41-46: Fiordelisa tells them of Orlando’s frenzy

- Canto XXXI: 47-49: Rinaldo pledges to cure Orlando of his madness

- Canto XXXI: 50-58: But first leads an attack on the Saracen camp

- Canto XXXI: 59-63: Fiordelisa tells Brandimarte of Orlando’s state

- Canto XXXI: 64-67: They go to seek Orlando

- Canto XXXI: 68-71: Brandimarte and Rodomonte fight, and plunge into the river

- Canto XXXI: 72-75: Fiordelisa pleads for Brandimarte’s life

- Canto XXXI: 76-79: Then goes to seek help in freeing him

- Canto XXXI: 80-84: King Agramante flees towards the south

- Canto XXXI: 85-88: The wounded Ruggiero is conveyed to Arles

- Canto XXXI: 89-93: While Gradasso seeks out Rinaldo

- Canto XXXI: 94-100: And encounters him in the field

- Canto XXXI: 101-105: They agree to contend for Bayard and Durindana

- Canto XXXI: 106-110: They prepare for the fight

Canto XXXI: 1-7: Ariosto on Jealousy

What sweeter and happier state is there

Than that enjoyed by the amorous heart,

What life more blessed and joyous than to share

Love’ servitude, and feel his piercing dart,

Did not fear and suspicion fill the air,

And doubt to every loving mind impart,

Engendering frenzy, suffering, misery,

Through that inner rage called jealousy?

For every other bitterness that’s born

From that sweetest of the sweets only serves

As an augmentation, night and morn,

That leads to the perfection love deserves.

Hunger and thirst ensure we will not scorn

The food we taste, the drink that life preserves.

And none can know true peace unless, before

That blessedness, they’ve known the pain of war.

Lovers, who gaze within the heart, calmly

Endure: they see what’s hidden from the eye.

The longer their absence, the more surely

Joy’s enhanced by what absence did deny;

While loving service without the mercy

Of reward, can be borne if hope is nigh.

For true service in the end may be repaid

Though the compensation be long delayed.

Disdain, refusal, scorn, the pangs, in sum,

Of love, the hurt endured, the suffering,

Of a heart that recalls its martyrdom,

To love’s delights a greater joy will bring.

But if that plague, hellish and unwelcome,

Infects the mind, poisoning everything,

No longer can the lover taste or savour

The pleasures of love, and its sweet flavour.

Tis like a cruel, envenomed wound; its harm

No balm, or soothing potion, can address,

Nor incantation, spell, nor subtle charm,

Nor favourable stars; seek not redress

From magic arts that would all ills disarm,

Those taught by Zoroaster, scant success

Attends on such. Cruel wound, of deepest woe,

That sends sad lovers to the grave below;

That wound, incurable, so readily

Inflicted on the lover, and no less

By false than true suspicion, cruelly,

Doth intellect and reason so oppress,

That judgement goes astray, endlessly,

Accompanied by sorrow and distress.

Wretched jealousy that thus, so wrongly,

Denied all solace to our Bradamante!

Twas not what her brother, or Ippalca

Had said that affected her so deeply,

I speak of the cruel news thereafter,

News that she took to heart, so bitterly

The former scarce compared to the latter.

The substance of it I’ll relate shortly,

But I must pause to tell of brave Rinaldo

And his folk, that to Paris first must go.

Canto XXXI: 8-12: Rinaldo’s company encounter a knight

On the following day they met a knight

With a fair lady riding at his side,

Both his shield and his surcoat black as night,

Save for a bar across it, white and wide,

He challenged Ricciardetto to fight,

As seeming chivalrous, that first did ride;

And he, who ne’er refused a challenge, wheeled

His steed, and sought the space his lance to wield.

Without more notice, not a single word

From either, they charged to the encounter.

Rinaldo and his company ne’er stirred,

But awaited the outcome of the matter.

‘I’ll soon unhorse the fellow,’ as he spurred

Onwards, Ricciardetto, chose to murmur,

‘If the ground is but solid, where we meet.’

But when they met twas he who lost his seat:

For he was struck hard below the visor,

And lifted with such force that he fell,

Despatched, by the might of that stranger,

Two lance-lengths beyond his steed, as well.

Alardo rushed to vengeance; however,

He was sent, his head ringing like a bell,

To lie prostrate upon the ground below;

He stunned, his shield shattered by the blow.

Guichardo levelled his lance, in a trice,

When he saw his two brothers on the ground,

Though Rinaldo cried: ‘Pause awhile, think twice,

For this course to my fame should redound.’

But his helm was untied, and his advice

Went unheard, as Guichardo forth did bound,

Held his seat no better than the others,

And ended in the dust like his brothers.

Riccardo, Malagigi, Viviano,

All now desired the outcome to contend,

But before their coursers rode Rinaldo

And thus to their contention put an end,

Saying, gently: ‘To Paris we must go,

And if each of you to earth must descend,

Unseated one by one, in this tourney,

We’ll be delayed too long on our journey.’

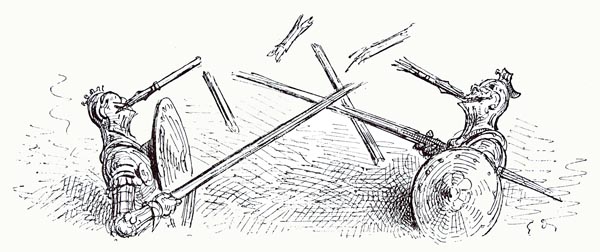

Canto XXXI: 13-17: Rinaldo fights and the stranger’s horse is slain

So, he spoke, but not in such a manner

As to give offence to the other knights.

Then he and his opponent came together

While bold Rinaldo held him in his sights,

Nor was he despatched to the ground either,

Being worth all the others in such fights;

Their lances were shattered, like fine glass,

But neither went backwards, in that pass,

For their coursers had met with such great force,

That both steeds sank back, towards the ground.

Yet Bayard rose at once, the stronger horse,

Scarce delayed, his bold rider safe and sound,

While spine and shoulder broken, in its course,

The other charger lay a lifeless mound;

Though its master had leapt from his seat,

As the steed fell dead, and rose to his feet.

And turning, then, to the mounted Rinaldo,

His empty hand outstretched, the warrior said:

‘Sir, this fine steed whose life is ended so,

Dear to me when alive, now he is dead

I’d ill repay if I landed ne’er a blow,

So let the debt now fall upon your head;

Lay on, and do the best that you can do,

For there is quarrel yet betwixt us two.’

Replied Rinaldo: ‘If we must battle here

For no more than a charger, do not pine,

Since one of equal worth that I hold dear,

I shall grant you, a fine courser of mine.’

‘No, no, you are in error, twould appear,’

Answered the knight: ‘You fail to divine

The meaning of my speech; I shall explain

More clearly, lest you treat me with disdain.

It seems to me I would commit an error,

If I failed to meet you now with the sword,

Not knowing if in our dance, earlier,

You were my peer, or less or more, milord.

So, as it pleases you, on foot or courser,

A second close encounter here afford,

And every advantage I shall grant you,

I so long to match blades betwixt us two.’

Canto XXXI: 18-22: They continue to match swords on foot

Pausing but a moment, brave Rinaldo

Cried: ‘I promise you as fierce a fight.

Yet if you fear that my friends might show

Undue support, you being a lone knight,

They must ride on, and wait for me, and no

Other, but my own squire, remain in sight.’

So Montalbano’s lord; and, thereupon,

Commanded his company to ride on.

The stranger rightly praised the chivalry

Of our paladin, who dismounted outright,

And then handed Bayard’s rein as promptly

To his squire, and when his banner bright,

Gone o’er the plain, he could no longer see,

He gripped his shield and faced the other knight,

Drew his sword and, raising the bright metal,

Challenged his foe in black to do battle.

And a battle indeed they now began

For fiercer contest none has ever seen.

Neither believed himself the lesser man

Nor that the other could resist, I ween,

Yet perceiving neither was stronger than

His foe, nor a swift advantage could glean,

They contained both their fury and their pride,

And every last skill they knew they applied.

The cruel and pitiless blows echoed round,

Filling all the air with their loud clashing;

Now from their shields was raised a dreadful sound,

Now from their plate and chain-mail, set ringing.

Yet twas more needful to maintain their ground,

Than seek to wound, and so keep their footing,

For the first error either warrior made

With irreparable harm would be repaid.

More than an hour and a half they fought so,

Until the sun had sunk into the sea,

While the sky filled with many a shadow

From horizon to zenith, steadily.

They had not stopped or rested, either foe,

Since they’d begun the joust, for chivalry

And the desire for honour made them fight,

Not anger or rancour, knight against knight.

Canto XXXI: 23-27: They cease for the night, and Rinaldo offers hospitality

Rinaldo pondered as to who this stranger,

Whose right arm was so powerful, might be,

That had put himself in mortal danger,

Many a time, and fought so valiantly,

And so hard and hotly at the task did labour

The issue was in doubt, and willingly

He’d, in truth, have desisted from the fight,

Had such not marred his honour as a knight.

His opponent likewise was unaware

That he fought the lord of Montalbano,

Who was so famed in joust and warfare,

And whom he now encountered as a foe,

Sword in hand, in so causeless an affair,

(For deep enmity did neither of them show)

Though he was certain greater excellence

None could display, or more experience.

He too wished to end their present game,

Of his making, regarding his charger,

And, if he could do so without blame,

Withdraw from thence, ere he met disaster.

So long were the shadows, that to maim

Was possible though neither was master

Of his blows, fighting blindly, two lords

That could barely see their outstretched swords.

Twas Rinaldo that proved the first to say

That they should not fight on in the darkness,

But their duel they might reasonably delay

Till the Wain had turned, with Arcturus,

And that he could rest until twas day

In his pavilion, his safety no less

Than his own, and be met there with honour,

And as well served as he had been ever.

The stranger needed little persuading,

And accepted his offer courteously.

Together they went to where the waiting

Company had pitched their camp securely.

A fine steed, adorned with every trapping,

His squire now led forth, and graciously

Rinaldo gave it, with a lance and sword

Both well-proven, to the delighted lord.

Canto XXXI: 28-33: They identify themselves to each other

The stranger then learned it was Rinaldo

Of whom he was now the honoured guest,

For the paladin had named himself so,

Before they had reached their place of rest;

They were half-brothers, and a tender flow

Of feeling did his softened heart invest,

While, moved by fond affection and surprise,

Tears of love and joy started from his eyes.

This warrior was Guidon Selvaggio

Who, you’ll recall, had sailed with Marfisa,

And Oliviero’s sons and Sansonetto,

On that long course o’er the sea together.

The vile Pinabel had delayed him, so

He could not seek his kinfolk earlier;

Seized by that rogue, he’d been made indeed

To enforce the rule the wretch had decreed.

Guidon, when he learned who was his host,

(That Rinaldo, famed beyond every knight,

Whom he’d been longing to see, almost

As much as a blinded man longs for light)

Cried gladly: ‘Of good fortune I may boast

That led me to engage, my lord, in fight,

With one whom long I have loved, and love,

And, of all men on earth, do most approve.

Guidon am I, born on the Black Sea’s shore,

At Constanta, and of Amone’s seed,

As you are likewise, whom fair Beatrice bore,

Thus, we are brothers then, as fate decreed.

To see you, and my other kin, therefore,

Was my desire, and here my course did lead,

Yet though my wish was but to honour you,

I see my coming has brought injury too.

Yet pardon me for so gross an error,

For I knew you not, nor your company,

And, to amend it, bid me do whatever

You may desire, ask aught you will of me.’

When each had fondly embraced the other,

For they clasped each other repeatedly,

Rinaldo cried: ‘Seek no more to excuse

A fight that neither of us dared refuse.

No better witness is there to your blood,

And that you too are of our ancient line,

Than the manner in which you here withstood

Our fierce contest, mingling that blood with mine.

If your manner were less warlike, we would,

Perchance, have doubted, such is not a sign

Of our House; the deer bears not the lion,

Nor is the eagle born of the pigeon.’

Canto XXXI: 34-36: Guidon joins their company

Not ceasing to speak as they rode on,

Nor ceasing to ride as thus they spoke,

They’d soon reached Rinaldo’s pavilion,

Where that knight then introduced to his folk

Their kinsman, and a half-brother, Guidon,

Whom they’d long desired to see; at a stroke,

He was welcomed among them, and further,

All noted the likeness to his father.

The greetings he received, I’ll not follow,

Those of Ricciardetto, then Alardo,

Then of his three cousins (Viviano,

Malagigi, Aldigier), Ricciardo,

And his eldest half-brother Guicciardo,

Nor the honour every captain did bestow,

But, in conclusion, I will merely say,

He was welcomed by his whole House that day.

At any time, Guidon had been held dear,

By his brothers, yet now, in time of need,

He was dearer still, and thus he did appear

Not only welcome, but fêted indeed.

And when the newly-risen sun shone clear,

Crowned with golden rays, from ocean freed,

Guidon, with his kin, as their new brother,

Found his place beneath Rinaldo’s banner.

Canto XXXI: 37-40: They meet Aquilante and Grifone

That day, and the next, upon their journey

They rode, till ten miles from Paris; there,

Upon the Seine’s wide shore, Aquilante

And Grifone they encountered; that pair

(Met by chance) you’ll recall, for completely

White was Grifone’s armour everywhere,

While Aquilante’s was black, and the two

Were Oliviero and Gismonda’s issue.

They were in conversation with a lady,

Nor was she of low condition to the eye,

For in white robes of samite clad was she,

Edged with gold; yet, rendered lovely thereby,

(Though she was else fair enough to see)

She seemed most sad, and tearfully did sigh,

Showing, by her manner, that she sought

To hold forth on matters of great import.

They knew Guidon, as he to them was known,

They’d been together some few days before;

And to Rinaldo he cried: ‘Those two alone

Are worth a hundred other knights and more.

Were they to fight for Charlemagne’s fair throne,

The Saracens and Moors would flee our shore.’

Rinaldo believed that such was true,

On recalling sundry tales of those two.

He’d also recognised the pair on sight,

From their usual contrasting armour

The one in black, the other all in white,

Their weapons, the trappings, and their manner.

While the brothers knew Montalbano’s knight,

And saluted Guidon too, and every other;

While both embraced Rinaldo as their friend,

And brought that former quarrel to an end,

Canto XXXI: 41-46: Fiordelisa tells them of Orlando’s frenzy

For they’d been involved in a lasting feud,

Through Truffaldino (the tale too long to tell),

Yet now expressed a kindly attitude,

And sought their former anger to dispel.

Meanwhile, Sansonetto he now viewed,

That came to join their little group, as well,

And Rinaldo welcomed him with honour,

Knowing his reputation, and his valour.

As the lady had watched our knight draw near,

She had recognised that mighty warrior

(She, acquainted with every knight and peer)

And shared her ill, most woeful, news further:

‘Orlando, your cousin, whom all hold dear,

In whose debt are Church and Empire ever,

Once honoured for his wisdom and prowess,

Now wanders the world, possessed by madness,

Through which things strange and ill have occurred,

Of which I know not how to tell the tale;

I saw his armour which he did ungird

Scattered o’er the field, in a lonely dale,

And a respectful knight, without a word,

Gather them, piously, from that sad vale,

And hang that fine and glorious panoply,

In the manner of a trophy, from a tree.

But the sword Mandricardo acquired,

The son of Agricane, that same day;

You may conceive the ills that might be sired

By Durindana, what harm that it may

Inflict on Charlemagne, what undesired

Fell part that sword, in pagan hands, might play.

Brigliador as well, that strayed, forsaken,

Round the scattered arms, was also taken.

Tis but few days since I saw Orlando,

Running naked, bereft of sense or shame.

With most dreadful cries and shouts, to and fro

He sped about; stark mad I deemed that same;

And had these eyes not seen it, such a show

I’d ne’er believed, so pitiful a game.’

Then she said how she’d seen him fall, swiftly,

From the bridge, embraced by Rodomonte.

‘To all those that were not an enemy

Of Orlando’s,’ she said, ‘I’ve told the tale,

So that one of those who heard the story,

(Strange, indeed) in whom mercy might prevail,

Might strive to bring him to Paris, shortly,

And purge his brain (perchance to small avail)

For, I know, if Brandimarte heard the news,

Despite all else, that task he’d not refuse.’

Canto XXXI: 47-49: Rinaldo pledges to cure Orlando of his madness

Fair Fiordelisa it was, the very same,

Dearer than his life to Brandimarte,

That in pursuit of him to Paris came.

And then she told of the sword, though briefly,

The source of dispute and rival claim

Twixt Gradasso and the Tartar, which he,

(Gradasso) once the Tartar king was slain,

Had been granted as a gift, and did regain.

By events so strange, and so full of woe,

Was Rinaldo pained, grieving, endlessly;

He felt his heart melting, in his sorrow,

As snow does in the sun on field and tree;

And was disposed, immutably, to go

And seek Orlando where’er he might be,

In hopes, could he but find the Count again,

Of purging that vile madness from his brain.

Yet, having gathered that fair company,

(Whether by pure chance or heaven’s will)

His next thought was to rout the enemy,

Ere that, leaving Paris unconquered still,

But thought to delay his foray, briefly,

Seeking to benefit from darkness, till

Deep in the first, or second watch, maybe,

Sleep sprinkling, then, the waters of Lethe.

Canto XXXI: 50-58: But first leads an attack on the Saracen camp

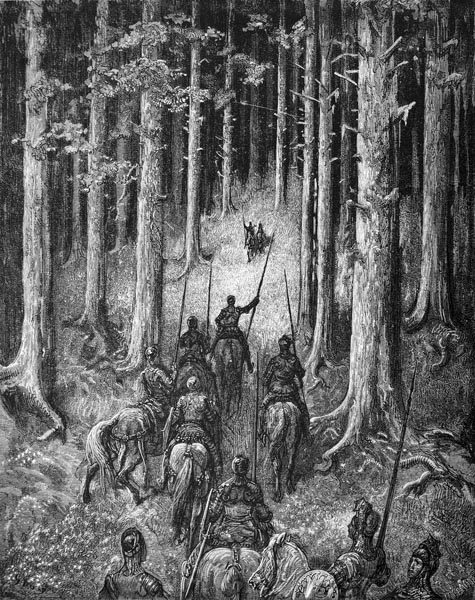

He placed his martial host within a wood,

And made them lie in ambush all that day;

But, when the sun had quenched his flame for good,

To his ancient nurse withdrawn, and so made way

For darkness, while the Bears and Dragon stood

In the sky, beasts invisible by day,

Hidden by the blaze of his greater light,

Rinaldo led his forces through the night.

With him went Aquilante, Grifone

Alardo of his blood, and Viviano,

A mile at least, and all most silently

And slowly; there too was Sansonetto.

Asleep lay all the host of Agramante.

They took no prisoners, but slew the foe,

For they were in amongst them well before

They were seen or heard by a single Moor.

That first move against the infidel band

Took the sentries posted round by surprise,

So swift, so fierce they scarce could raise a hand.

Soon all lay dead there, nevermore to rise.

The first point taken, and the guards unmanned,

The Saracens were lost to wild surmise,

For those not slain while helpless in their sleep

Scarce understood the harm their foes did reap.

To stir the greater dread, the bold Rinaldo

At the very instant of their attack,

Had the drums sound and the trumpets blow,

And his war-cry ring out, as with no lack

Of vigour he spurred Bayard gainst the foe,

Clearing the fences, hurling on their back

Those who tried to rise, and in his wrath

Tearing down the tents and booths in his path.

There was none so brave before Rinaldo

That did not stiffen, all their hair on end,

Hearing the mighty shouts of ‘Montalbano!’

While groans and cries did to the sky ascend,

The hosts of Africa and Spain scarce slow

To abandon what they’d failed to defend,

Unwilling to stand firm and fight, in vain,

Against a foe that brought such grief and pain.

Guidon followed him, in eager quest,

With the warrior sons of Oliviero.

Onwards Alardo, Guicciardo, pressed

Ricciardo, and Ricciardetto,

With Sansonetto; each the foe addressed,

While Aldigier and Viviano,

Following the flag of Chiaramonte,

Fell valiantly upon the enemy.

Seven hundred men had Rinaldo drawn

From Montalbano, and the lands around,

Used to heat and cold, to fighting born,

Like Achilles’ Myrmidons, strong and sound;

Ever were they to Chiaramonte sworn.

A hundred gainst a thousand would be found

Firmer of stance, while many known to fame,

Proved less valiant than many of those same.

If Rinaldo’s estate was not so wealthy,

He less possessed of cities or treasure,

He drew them by fair speech and courtesy,

And granted to every man just measure,

Rewarding their valiant service freely,

Such that none deserted him at pleasure,

And men from Montalbano mustered there,

Unless some pressing need found them elsewhere.

Thus, had he brought them to aid Charlemagne,

Leaving his own great castle lightly guarded.

Down upon the African camp like rain

They fell, that force that brave Rinaldo led,

Wreaking the havoc that a wolf is fain

To wreak upon the fine flocks that are bred

By the Galeso, or some lion at the throat,

By the Libyan Cinyps, of many a goat.

Canto XXXI: 59-63: Fiordelisa tells Brandimarte of Orlando’s state

Charlemagne who had news from Rinaldo

That he was close to Paris, and would seek

To assault the Saracen camp by night also,

Had thereon summoned up his troops to wreak

Vengeance, and aid Rinaldo gainst the foe,

And now they came, as needed, midst the reek

Of death, with them the son of Monodante,

Fair Fiordelisa’s love, Brandimarte,

Whom she had searched for many a day,

Throughout the whole of France, and yet in vain.

By the emblem he alone did display

She knew him, in the dawn light, saw him plain,

And when he found her gazing on the fray,

He shunned the battle, and her side did gain,

Embraced her warmly, on her eyes did feast,

And kissed the maid a thousand times at least.

Great trust was placed in maidens in those days.

Women journeyed, without escort, everywhere,

O’er hill and dale, in strange lands, rode the ways,

And yet, on their return, were thought as fair

And virtuous, and earned not scorn but praise;

None earned doubt and suspicion for their share.

Fiordelisa told her Brandimarte

Of Orlando, and his sudden frenzy.

He found the news so strange he received,

He’d not have believed it from another,

And yet stranger things she had perceived,

Thus, he believed it, from fair Fiordelisa;

Nor had she heard the tale, and been deceived,

Her eyes had seen it, she told her lover,

For she knew the Count as well as any,

And told him where and when, midst many

Other details, and how Rodomonte

On his perilous bridge had met the knight,

Beside the sepulchre where in glory

He hung the arms won in many a fight.

Of Orlando’s frenzy she told the story,

And of the battle they had fought outright,

And how the Saracen fell to the flood,

In grave danger of sinking there for good.

Canto XXXI: 64-67: They go to seek Orlando

Brandimarte, whom the Count loved as much

As one could love a friend, son or brother,

Was disposed to seek for him, and do such

As he could Orlando’s wits to recover,

Through healing arts or some wizard’s touch,

Scorning, as he went, all thought of danger.

As he was in the saddle, armed and ready,

He swiftly took his way, beside his lady.

They directed them both to the place,

Where she had last seen the mad Orlando,

Riding many a day, at a steady pace,

Until they reached the bridge that spanned the flow.

The guard called out, and, as was e’er the case,

Rodomonte appeared, gazed at his foe,

And received from his squire steed and lance,

Prepared for Brandimarte’s bold advance.

In a voice, well-suited to his anger

The Saracen called to Brandimarte:

‘Whoe’er you may be, that in error,

Of one sort or another, fate has sadly

Guided here, be prompt to doff your armour,

And pay homage at the tomb ere, swiftly,

I despatch you to the shades, there below,

Though scant merit I gain by doing so.’

Brandimarte offered naught in reply

Other than to level his sturdy lance,

And spur his steed Batoldo, by and by,

And show his ardour by his fierce advance,

To show his spirit was as great, thereby

As any valiant warrior in France,

While Rodomonte levelled his also,

And at full pace along the bridge did go.

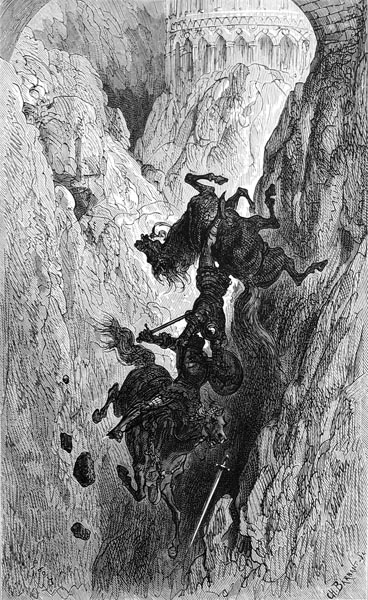

Canto XXXI: 68-71: Brandimarte and Rodomonte fight, and plunge into the river

His steed charged safely to the encounter

Accustomed to make that very crossing,

Where the fate of many another

Was to fall to the stream while advancing;

Batoldo, not used, like the king’s charger,

To the bridge, was doubtful and trembling;

The stones seemed to shake, the world to sink,

And twas narrow, and unwalled at the brink.

As a master of the joust, each knight

Bearing his lance weighty as a spar,

A sapling cut and hewn for the fight,

Dealt thus no gentle blow, but aimed to mar;

Nor was the experience or the might

Of their advancing coursers a bar

To disaster, upon the bridge both fell,

The riders downed, and their steeds as well.

Both the horses tried to rise, with that haste

That a spur in the flank sought to ensure,

But on the narrow bridge were yet ill-placed

To gain a footing, their swift steps unsure,

And both, of equal fate, the air now graced,

While a mighty splash Fiordelisa saw,

Like that which issued from the River Po,

When Phaethon, scorched, fell to the earth below.

Each courser, with the full weight of its knight,

Upon its back, had plunged into the deep,

The riders no doubt hoping to catch sight

Of a lovely water-nymph to grace their leap.

Not the first descent, nor the second flight,

Was this in which the king had, by a steep

Descent, attained the river’s watery bed,

By now in all its mysteries well read.

Canto XXXI: 72-75: Fiordelisa pleads for Brandimarte’s life

Where it was firmer or softer, this he knew,

And where the water was deep or shallow.

His head, and chest, and flanks thus rose anew,

And, standing there, he landed many a blow.

Brandimarte the current nigh overthrew,

While his horse was rooted in the mud below,

And sand and gravel too, such that the courser,

And his master, risked drowning in the water;

Great plumes of spray they raised, and fought the flow,

Yet only slid down deeper in the stream,

The horse now uppermost, the knight below.

Fiordelisa, from the bridge, her fear extreme,

Tears, prayers, and vows on them did bestow.

‘Rodomonte,’ she cried, ‘for her you deem,

Though dead, your goddess, now, uphold the right;

Spare, for her sake, so valiant a knight.

Oh, most courteous lord, if you have loved,

Show me, that loves him, a little mercy,

If by such prayer your heart may be moved,

Make him your prisoner, such is my plea;

Hang the spoils on the wall, your deed approved

By all the powers that be, none more worthy.’

And her plea had been framed with so much art,

It served to move even so hard a heart.

Rodomonte, now brought aid to her lover,

Held by his horse almost beneath the flow,

His life itself in question, moreover,

And thirsting not, yet drinking even so.

Before he gave him succour, however,

The helm and sword he chose not to forego,

Then drew the knight, half-dead, from out the deep,

To hold him with the others in his keep.

Canto XXXI: 76-79: Then goes to seek help in freeing him

The lady’s unhappiness was great, though,

When she saw her knight made a prisoner,

Though she was better pleased to view him so

Than see her lover drown in the river.

That she was now the reason for his woe,

She regretted, blamed herself, no other;

For her tale of the Count, and that affair

At the perilous bridge, had brought him there.

She departed, while planning to return

After seeking the aid of Rinaldo,

(Who would surely her lover’s freedom earn)

Or that of Guidon or Sansonetto,

Or some other who to joust might yearn,

Not on land alone, but in water also,

And, if not stronger yet more fortunate

Than Brandimarte might escape his fate.

She rode for many a day ere she found,

A knight who had the semblance of being

What she was seeking, one who might astound

The Saracen, her lover then freeing;

Butt, after searching all the country round,

Such a man now came within her seeing,

A richly embroidered surcoat he wore,

For woven cypress trees the garment bore.

Who he was I will tell you of elsewhere,

For first to Paris I must go, then speak

Of how Malagigi and Rinaldo there

Great discomfort upon the Moors did wreak.

Countless numbers fled in sheer despair,

While countless other folk the Styx did seek.

Let the dark leave Bishop Turpin to tell

How many were slain amidst the infidel.

Canto XXXI: 80-84: King Agramante flees towards the south

Agramante was sleeping in his tent

When a guard awoke him, and warned the king

That he was like to be a prisoner, pent

Among the foe, unless, the camp forsaking,

He chose to make swift flight his sole intent.

He looked about, and saw the army fleeing,

Naked and unarmed, o’er the darkening field,

Lacking the time to grasp a sword or shield.

Confused by these events, lacking counsel,

He had forced himself to don his armour

When Falsiron joined him, his son as well,

Grandonio, and many another

With Balagante, while the noise did swell.

They too advised the king of his danger,

And that Fortune would now prove most kindly

If he could issue from the camp, in safety.

So said Marsilio and Sobrino,

While the others confirmed it with one voice;

Their destruction was nigh, for Rinaldo

Came upon them; flight was his only choice.

For to await the fierce paladin so

Given the strength in which he did rejoice,

And seek to make a stand, amidst that strife

Would be to risk his liberty and life.

To Narbonne or to Arles he might retreat,

With all the troops he could yet command,

Since either place was sound, and complete,

And many a day gainst the foe could stand;

While, having saved his person from defeat,

He could avenge himself, his force re-manned,

And then expunge every trace of shame,

By destroying these friends of Charlemagne.

Agramante now favoured their opinion,

Though thought of retreat he did abhor.

Towards Arles he went, on swift pinion,

By the path that seemed the most secure.

Beyond all else, the darkness held dominion,

And rendered their flight the more obscure;

Twenty thousand men of Africa and Spain

Escaped Rinaldo’s grip, to fight again.

Canto XXXI: 85-88: The wounded Ruggiero is conveyed to Arles

Those whom Rinaldo and his brothers slew,

With Oliviero’s sons, that valiant pair;

Those whom his seven hundred, good and true,

Encountered, and then slaughtered everywhere;

Those whom brave Sansonetto overthrew,

That drowned themselves, in the Seine, in despair;

He who’d count them all, might count indeed

The flowers that Zephyr and fair Flora breed.

One might surmise that Malagigi bore,

A large part in the victory that night,

Not that he drenched the field with blood and gore,

Nor broke as many heads, but that the might

Of the infernal angels, he, through magic lore,

Conjured from Tartarus, to join the fight,

Bearing many a banner and sharp lance;

More than twice the force deployed by France;

And raised so great a noise of clashing metal,

And made so many different drums resound,

And invoked so many sounds amidst the battle,

Of horses neighing, feet trampling the ground,

Echoing from hill and dale, to rattle

The startled enemy with deafening sound,

That the Moorish troops were filled with dread,

And from the field, in panic, turned and fled.

Yet the king forgot not Ruggiero,

Who was wounded, and in desperate plight,

But had them bear him to a steed, and so,

Convey him from the field, as best they might.

They bore him, their pace secure and slow,

By a safe path, aboard ship set the knight,

And so bore him to Arles, in comfort; there,

The army his safe haven soon might share.

Canto XXXI: 89-93: While Gradasso seeks out Rinaldo

Those who fled Rinaldo and Charlemagne,

(A hundred thousand, I believe, at least)

Through the woods and dales, over hill and plain,

Sought escape from the Franks’ most bloody feast,

Yet the greater part was penned in, and slain,

And stained the pale grass ere the battle ceased.

Though Gradasso’s tents lay further away,

And he chose to fight on that fatal day:

For finding the foe led by Rinaldo,

His heart rejoiced, filled with such delight

That he strode here and there, to and fro,

Thanking his god for his grace that night,

And blessing his fate for aiding him so,

In allowing him to face that fierce knight,

Hoping to garner Bayard, that rare steed,

In valiant duel, and on the terms agreed.

For Gradasso had longed, many a year,

(As you may have read in another place)

To own that mighty horse devoid of fear,

And have Durindana his armour grace;

Thus, with a hundred thousand, in full gear,

He’d sailed to France its warriors to face,

And this Rinaldo he had sworn to fight,

Hoping to gain the charger from the knight.

And thus, his passage led him to that shore

Where the ownership might be contested.

But Malagigi marred his attempt before

They’d met: his cousin’s course he arrested

Then, by enchantment, o’er the waves he bore

Rinaldo (long the tale, its truth attested)

While Gradasso thought both timid and base

A knight that would not meet him face to face.

So, he rejoiced knowing twas Rinaldo

Who’d assailed the camp, and with delight

He leapt upon his fine steed, Alfano,

And went searching for him in the dark of night.

And, where’er he went, he trampled on the foe,

And left them dead, or wounded, in the fight;

Though men of Libya not just of France,

In that darkness, were food for his brave lance.

Canto XXXI: 94-100: And encounters him in the field

He searched for Rinaldo here and there,

Summoning him, as loudly as he could,

Then steered his charger to the region where

The corpses were piled highest, like dead wood.

Till they met; blade to blade was that affair,

For their lances had broken; to the mud

Fell the fragments, while sharp splinters, in flight,

Rose to strike the starry chariot of Night.

Once Gradasso had recognised his foe,

(And not by the insignia he bore,

But by the force of his every blow,

And by Bayard, driving men on before)

He was not slow to call upon Rinaldo,

To amend his quitting of that shore,

(Where he’d left him alone upon the field

Appointed for their battle) and to yield.

And then he said: ‘You had hoped perchance

That by your hiding on that occasion

You might for evermore escape my lance,

(Or, as now, my sword) and, by evasion,

Avoid us meeting more, yet I advance

To meet you now, needing no persuasion,

For I’d search for you in heaven or hell,

Above the earth, and deep below as well,

Until that mighty charger you forego.

Yet if you think the odds are unequal

And honour of less worth than life, bestow

Your horse on me, and this piece of metal,

And life you’ll have, if life is dearer; so

Amend the wrong, and now quit the battle,

On foot, being unworthy of the steed;

If on Chivalry you’d work so ill a deed.’

In hearing, was Guidon Selvaggio,

Who brandished his gleaming sword on high,

As did his half-brother Ricciardetto,

Who thought to strike Gradasso, by and by;

But they were both thwarted by Rinaldo,

Who preserved him, with his sudden cry;

‘Am I not man enough then, in your view,

To respond without aid from both of you?’

Then he turned to the infidel and said:

‘Hark, Gradasso, and you may understand,

Without my raining blows upon your head,

That I did indeed seek you, on the sand,

And this I tell you true, ere you lie dead,

And such I shall maintain, by strength of hand,

And that you lie, if you should choose to say,

The laws of chivalry I’d e’er betray.

But I pray you, ere we decide to fight,

To, courteously, accept my fair excuse,

And pardon so my vanishing from sight

Against my will, and cease this vile abuse.

And, as to Bayard, I pray you sir, alight,

Contend for him (unless you would refuse)

As you desire, and in some sandy place

We may duel, on foot, and face to face.’

Canto XXXI: 101-105: They agree to contend for Bayard and Durindana

King Gradasso, fuller now of courtesy,

(For all magnanimous folk behave so)

Was thus content to hear the whole story,

And perchance excuse the brave Rinaldo.

Towards the river bank, immediately,

They repaired, where our knight sought to show

In simple words, thereby lifting the veil,

The truth (by Heaven!) of his honest tale;

Then called on Aldigier as witness

To the history, which he knew entire,

And asked him that same tale to address

To Gradasso, once more, twas his desire,

And tell of the enchantment, while no less

Would Rinaldo prove it true, or expire

In duel, where’er, whene’er Gradasso chose;

‘For there’s no finer proof of it, God knows.’

King Gradasso who, not for a moment,

Wished to trade one quarrel for another

Accepted the excuse and was content,

Though doubting the truth of the matter.

They agreed to execute their intent

On Barcelona’s sandy beach, hereafter,

Then set the time for the following morn,

Hard by a neighbouring spring, and at dawn.

And there Rinaldo would lead the charger,

And tether it between them on the sand,

And if Gradasso then proved the victor,

Why brave Bayard would be his, to command;

But if the king failed to kill or capture

Rinaldo and (not dead upon the strand)

Sought mercy, let Gradasso not mistake

That the sword, Durindana, he would take.

For it had been with wonder and sorrow

That Rinaldo had heard (as I explained),

From the fair Fiordelisa, of Orlando,

And of his frenzy, wild and uncontained,

And how the sword was gained without a blow;

How, through a quarrel, it was then ordained

That Gradasso should, thus, hold in his hand

That blade long-famed in many a fair land.

Canto XXXI: 106-110: They prepare for the fight

Once decided, the king rode to his tent,

Though Rinaldo suggested he might stay

The night with him; the king would not relent,

And so, to his own household made his way.

In accord with their solemn agreement,

Both armed themselves and, at the break of day,

Rode to the place by the spring; there, either

Might attain both Bayard and Durindana.

Of this battle, where they’d fight one to one,

It seemed Rinaldo’s friends were much in fear,

And were grieving ere the thing was begun,

Lest he should fall, who to them was most dear,

King Gradasso’s strength was second to none,

He had skill and ardour, and wielded here

Orlando’s sword, that dealt a mighty blow;

Thus, their cheeks were pale who hailed Rinaldo.

Malagigi was more fearful than the rest,

And, doubtful of the outcome of the fight,

Would willingly have done his very best

To thwart the paladin’s intent, outright,

Yet was concerned if he should seek to, lest

He made an enemy of that brave knight,

Still angry with him from the time before,

When he had made him vanish from the shore.

Yet leave those others to their doubts and fears!

Rinaldo went his way and, dreading naught,

Sought to erase the shame which, it appears,

Was far too great to bear; such was his thought,

And to silence slander, in after-years,

In Altafoglia, Poitiers, or at court,

Confident that he’d triumph midst the sand,

And return with Durindana in his hand.

They appeared, well-nigh at the same moment,

From opposite directions, near the spring,

Greeting each other, seemingly content

To show a friendly and a welcoming

Countenance, despite their grave intent,

As if they were kin, and gifts did bring.

But to another time I shall defer

The tale of what was destined to occur.

The End of Canto XXXI of ‘Orlando Furioso’