Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XV: Astolfo's Travels

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XV: 1-5: Rodomonte survives the fire

- Canto XV: 6-9: Agramante attacks the gate

- Canto XV: 10-15: We return to Astolfo, who takes leave of Logistilla

- Canto XV: 16-24: Andronica’s prophecy regarding the sea-routes

- Canto XV: 25-37: And regarding Charles V and his imperialistic ventures

- Canto XV: 38-41: Astolfo reaches the Nile

- Canto XV: 42-49: He meets a hermit who warns him of a giant

- Canto XV: 50-59: Astolfo overcomes the giant, Caligorante

- Canto XV: 60-65: He reaches Cairo, where he hears of the robber demon, Orrilo

- Canto XV: 66-74: He finds Orrilo at Damietta, in battle with two brothers

- Canto XV: 75-78: The fight is deferred till the following day

- Canto XV: 79-81: Astolfo determines to slay Orrilo

- Canto XV: 82-87: And succeeds in conquering him

- Canto XV: 88-94: The three knights set out to visit Jerusalem

- Canto XV: 95-99: They meet Sansonetto, governor of the Holy Places

- Canto XV: 100-105: Of Grifone and his beloved, Orrigille

Canto XV: 1-5: Rodomonte survives the fire

Victory was e’er a praiseworthy thing:

By good fortune to win, or skilfully.

Though, tis true, to a leader it will bring

Less praise, it it’s a bloody victory.

While, divine honours, fast accruing,

And a glorious claim on posterity,

The general sees, who saves his men from harm,

And puts the foe to rout, remaining calm.

Ippolito, you proved worthy of praise,

When the Venetian lion, so fierce at sea,

Held the banks of the Po, and all the ways,

From Francolino to its mouth, yet we

Did that to him, which though he seeks to raise

A roar, quells fear at the mere memory.

How a battle should be won, you made plain,

For we were saved, the enemy were slain.

This the pagan knight, with too bold a deed,

Failed to achieve; his men were in the moat,

While that sudden, greedy flame guaranteed

None survived, swallowed by its fiery throat.

Devoured by that inferno, packed, indeed,

So tightly together that none could float,

Their flesh reduced, in that heat, to dust,

All to one tomb their king did now entrust.

Of eleven thousand and twenty-eight,

That found themselves inside that burning pit,

Who, though discontented, entered straight,

All were dead, but not he who ordered it.

In that hell of sound and flame, lay their fate,

Consumed by the flames the Christians lit;

Yet Rodomonte the cause of their pain,

Had lived on, so it seemed, to fight again.

For, midst his foes that held the bank, he’d passed,

By vaulting that wide ditch, most wondrously,

While, had he not been first, but of the last,

It would have brought his end, assuredly.

He turned to gaze, now, at the flames, aghast,

Leaping skywards, from that hellish valley,

And, hearing his warriors’ screams and cries,

Called out vile blasphemies towards the skies.

Canto XV: 6-9: Agramante attacks the gate

Agramante, meanwhile, had launched a force

Of substantial size, against a city gate;

For as that cruel battle ran its course,

In which so many men had met their fate,

He thought it undefended or, perforce,

So weakly manned, his soldiers need not wait.

With him, Arzilla’s king, Bambirago,

Went forth; that tub of vice, Baliverso;

Corineo of Mulga; Prisione,

The wealthy King of the Isles of the Blest;

And Malabuferso, who held the city

Of Fez, where summer ever was a guest;

While there followed, a goodly company

Of well-armed men, in battle of the best,

And a naked host, whom this side the grave,

A thousand shields could not have rendered brave.

But all proved contrary; against the foe,

(This King of Africa) the Emperor stood;

Within the walls his person he did show,

With many a knight, to make his mission good:

Salamone, the Dane Ugiero,

Both Angelinis, both Guidos, of high blood,

Bavaria’s duke, Avino, Ganelone,

Berlengier, Avolio, and Ottone,

And many others, though of lesser stature,

Lombards, Franks and Germans, and the rest;

Each, in the presence of their Emperor,

Desiring to be numbered with the best.

Of this I’ll give account, a little later,

For, now, a great duke claims my interest,

Who calls me from afar, and pleads with me,

Not to exclude him from my history.

Canto XV: 10-15: We return to Astolfo, who takes leave of Logistilla

It’s time that I returned to where I left

That venturesome Astolfo of England,

Who, hating exile, still of home bereft,

Burnt with desire to reach his native land.

Logistilla had raised his hopes, who’s deft

Use of her powers had granted her command

Of the battle with Alcina, and whose care

Was now to see him swiftly, safely, there.

And so, by her, a vessel was prepared,

A better ship has never sailed, surely;

And since she feared lest Alcina dared

To perpetrate on him some treachery,

She requested that Andronica shared,

With Sofrosina, his homeward journey,

Their ships armed, till the Arabian Sea

And the Persian Gulf were reached, in safety.

She preferred that a course he should maintain

Past India, Parthia, Nabatea,

And, by that long coastal route, attain

The realms of Persia and Eritrea,

Rather than attempt the northern main,

Where violent gales thwart the mariner,

And, at some seasons, the sun’s so low

For many months, it barely seems to show.

When the faery queen saw all was ready,

She gave permission for the duke to leave,

After instructing him, first, carefully,

In many a thing (a tale too long to weave);

And, so none might delay him, unduly,

By means of magic charms, wrought to deceive,

A fine and a useful book she gave him,

To keep, for love of her, close beside him.

How a man might resist vile enchantment,

This book revealed, which was the faery’s gift;

At start an end, more than in its treatment,

Its contents and its index showed its drift.

And she bestowed on him next, ere he went,

A war-horn that, whene’er a man did lift

It to his lips, made such a fearful sound

Any foe would flee whose ears it found.

The noise the war-horn made was such, I say

As to put all who heard it to swift flight;

Nor was there any man who, at that bray,

Owned a heart so sound he failed to take fright;

Tempest, earthquake, thunder, their din did weigh

Naught beside it, their whole effect was slight.

With thanks the Englishman did these receive,

Then, of the faery queen, he took his leave.

Canto XV: 16-24: Andronica’s prophecy regarding the sea-routes

Quitting the port, and its calmer waters,

With, at their stern, a favourable breeze,

They sailed south, past rich, populous harbours,

Rounding the perfumed Indies with ease,

Skirting a thousand scattered island markers.

Bound now for Saint Thomas’ land; in those seas,

The helmsman now turned, still following

The coast, and set them on a northward heading,

Furrowing the waves, their fine squadron sailed;

Shaving the Golden Chersonese, and then

Viewing the waters where the Ganges paled

The ocean; south, along rich shores again,

Past Coromandel; with Sri Lanka hailed,

Through the straits between, into the main,

Made Kochi, rounding India’s southern tip

Following the coast northwards, at a clip.

Scouring the ocean with his faithful guide,

One so certain in her knowledge, the knight

Asked Andronica if from the western side,

Of Europe, named, from the fading light,

The Hesperides, a vessel might yet glide

Into the Eastern ocean’s waves outright,

And so, without ever their touching land,

Those of India reach France, or England.

‘You should know’, replied wise Andronica,

‘All Earth’s land is surrounded by the seas,

And the waves pass from one to another,

Whether the water boils or seeks to freeze;

Yet, where the Ethiopian lands lie, further

To the north-west a few sun-scorched degrees,

Some mighty power has, long ago, decreed

That Neptune may not certain bounds exceed.

So that from here, India’s western coast,

No vessel can to Europe makes its way,

Nor can our western navigators boast

That they have sailed to where we lie today.

Though, seeing those lands ahead, that almost

Invite the traveller on, from bay to bay,

To one, or another, it might appear

They could glide into the other hemisphere.

Yet I foresee, in time, that some new Argo,

Steered by some new Tiphys, will be seen

And from our own western lands they’ll go,

Opening a path where none as yet have been.

Rounding Africa, sailing west, also,

Skirting the dark-skinned peoples’ shores, I mean,

From where the sun stands overhead at noon

In Capricorn, to where that’s true in June;

Finding the end of that great length of shore

That seems to border two quite separate seas;

Who have but known the coastlines, heretofore,

Of Araby, Persia, and the Indies.

Others I see who’ll leave us, through that door

That’s marked by the Pillars of Hercules,

Following the westward path of the sun,

Until, indeed, new lands, new worlds, are won.

On some green shore the sacred cross I see,

And the great banner, of your Emperor,

I see men guard the ships from treachery,

While others go to seize new lands in war;

I see ten chase a thousand there who flee,

As Aragon those realms, past India’s shore,

Makes subject to its rule, while, everywhere,

Charles the Fifth’s captains find victory there.

God wished, of old, these paths should be concealed,

That centuries must pass ere they be won,

Nor would allow this prophecy revealed

Until the seventh century was done,

And only then would that true knowledge yield,

When one great monarch ruled the world as one,

The wisest emperor, and most righteous,

That shall be, or has been, since Augustus.

Canto XV: 25-37: And regarding Charles V and his imperialistic ventures

Of the blood of Austria and Aragon,

I see a monarch raised, on Rhine’s left bank,

A prince unequalled, in truth, for none

Shall be his peer, that tale or story rank

As such; Astraea, once more, neath the sun,

He shall install, he, whom all men shall thank,

And Virtue who, with Justice, left the Earth,

From exile shall return, and prove her worth.

Granted his great merit, Goodness Supreme,

Intends that this prince shall not only bear

The crown that on Augustus’ brow did gleam,

That Trajan wore, Aurelius, wisdom’s heir,

And Severus, but those of lands extreme,

That neither sun nor season know or share.

And desires that, beneath this emperor,

The sheep will form one flock, with one pastor.

And to accomplish it with greater ease,

Has ordained above, proclaimed eternally,

That high Providence, on lands and seas,

Shall grant him captains to his greater glory;

I count Hernando Cortez amongst these.

Men who’ll bring him many a city,

And kingdoms in the East so remote

That, of them, we in India take no note.

Now Prospero Colonna, I behold,

And Fernando of Pescara, and I see

A youth, lord of Guasto, who to the gold

Fleur-de-lys will make dear our Italy;

And he, this third, the laurels shall behold,

His prize, as a strong athlete will, swiftly,

Take up the lead, and run with strength and art,

To finish first, although the last to start;

So great his valour, and his loyalty,

This Alfonso (for such will be his name)

That in his unripe age (no more he’ll be

Than six and twenty, although born to fame)

The emperor will trust him with an army,

Saving which, that monarch shall reclaim

The rest, and make the world obey his hand,

With this youth, who at Pavia shall stand.

As with those captains ashore, who grow

His empire, and extend its ancient sway,

So, on the sea, that with its ebb and flow

Divides Europe from Africa, I say

He’ll meet with certain victory also,

Good Andrea Doria his friend alway;

That Doria, who from the pirate horde

Will wrest the waters, their true peace secured.

Nor with Pompey should he be compared,

Who overcame the corsairs; in no way

Were those men equal to the power they dared

To challenge, the mightiest of their day,

While Doria, all alone, will be prepared

To purge the waves, and sweep that horde away;

And, from Calpe to the Nile, all who hear

His illustrious name will quake with fear.

Beneath the banner of his loyalty,

(This glorious captain of whom I speak)

I see his Emperor enter Italy,

The door to which he opens, yet will seek

For his country, not himself, victory,

Asking the monarch for a gift, unique,

The freedom of his Genoa, alone,

Though he might have claimed it for his own.

The pious love he’ll show his native land

Is worth far more than any honour won

By Julius in France, Spain, your England,

Thessaly or Africa, when said and done;

Nor should Octavius like praise command

Nor Mark Antony (who met neath the sun,

With equal forces) for such civil war

Tarnished them, yet hurt their country more.

Let any man who would rob a country

Of its precious freedom, blush for shame,

Nor raise his eyes, nor call it victory,

While men speak Andrea Doria’s name.

I see that Charles will add to his bounty,

Granting him, beyond the common claim,

Rich lands round Melfi, which had earlier

Watched Norman power wax in Apulia.

Not only will Charles show great courtesy,

Magnanimously, to this great captain,

But to all who, for the Empire, will be

Unsparing of their blood; he will obtain

More pleasure from bestowing some fair city

On a loyal friend than from some new gain,

An empire, or a kingdom, newly won,

Rewarding every worthy deed that’s done.’

Thus, Andronica informed Astolfo

Of the achievements, that, on land and sea,

After long years had passed, this Charles would owe

To his great captains: many a victory.

All this while, as the easterlies did blow,

Sofrosina curbed or loosed them, gently,

Having this gust or that serve their need,

Increasing, or diminishing their speed.

Meantime the Persian Gulf they entered,

And viewed the wide extent of its waters,

Whence the ships, in a few days, visited

The Bay of the Magi, with its harbours,

And here they made port, and swiftly anchored,

Ships’ prows towards the waves, those wanderers;

Then, safe there from Alcina and her war,

Astolfo continued his route on shore.

Canto XV: 38-41: Astolfo reaches the Nile

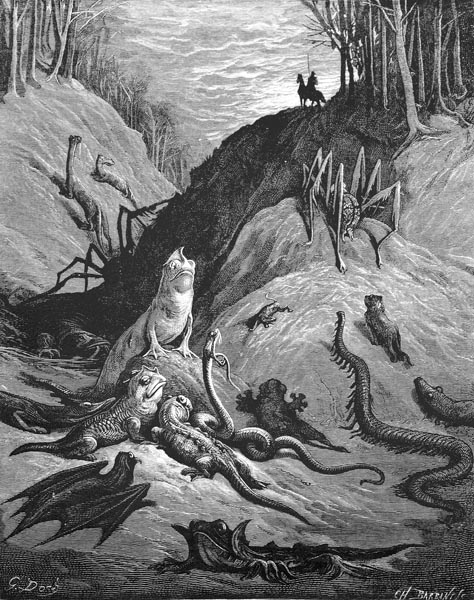

He passed through many a wood and meadow,

O’er many a hill, down many a dale,

Where thieves and brigands his tracks would follow,

Both day and night, as he pursued the trail,

And lions and venomous snakes, as he did go,

And savage monsters, and yet, without fail,

As soon as on his magic horn he blew,

Away the creatures ran, or slid, or flew.

Through Arabia Felix he progressed,

Rich with odorous incense, and with myrrh,

Where the solitary Phoenix makes her nest,

Though all the world is hers should she prefer

Another home; and by that sea did rest

Where God’s vengeful miracle did occur,

Through which the Pharaoh and his troops were lost

While, to the Promised Land, Israel crossed.

Then along Trajan’s wide canal he rode,

On his war-horse that ever lacked a peer,

That moved so lightly that the soft sand showed

No traces of our valiant cavalier,

No more than would the drifts if it had snowed,

Or fresh grass; while, dry-shod, o’er waters clear

Twould pass and, ever with the lightning twinned,

Fly faster than an arrow or the wind.

This charger was Argalia’s before,

Born of the union of wind and flame,

Nourished not on fodder but the pure

Air itself; Rabicano was its name.

He followed the channel, upon the shore,

Till where the Nile united with that same;

Yet, before he reached the river, he saw

A boat upon its waves; a man it bore.

Canto XV: 42-49: He meets a hermit who warns him of a giant

A hermit steered it, seated at the stern,

A snowy beard descended to his chest.

He urged the duke, with evident concern,

To embark: ‘Come, my son, for it were best;

Unless, perchance, you loathe your life, and yearn

For Death to come, and its fair course arrest.

Come, cross the water to the other side,

For on the path, you take, have many died.

Within a distance of six miles or so,

You’ll find the opening to a dreadful cave,

Wherein the giant dwells, a house of woe,

And he seems eight feet taller to the brave.

You have no hope of fleeing from this foe,’

The hermit said, ‘the place would prove your grave,

For some he quarters, and some he flays,

Many he swallows, while none go their ways.

Amidst his cruelties, he takes pleasure,

In a net, a cunning snare divinely made,

Nor far from his den, but a brief measure,

Concealing it, beneath the sand, in shade,

Such that those who seek shade, at leisure,

Unknowingly fall foul (tis so well laid)

Of its mesh, while his shouts then terrify,

Entangling the traveller further, thereby.

Then, with cruel laughter, he drags all those

His malice captures to his dwelling place;

With man or maiden, to his cave he goes,

Plain commoners, or those of noble race.

On their flesh and brains, his mouth will close,

While their bones the desert sands will grace.

And the skins he hangs, all bloodied and torn,

About the walls, his cavern to adorn.

Choose another road; embark, my son.

My boat will take you, safely, to the sea.’

‘Thanks for your counsel, yet if that were done,’

The warrior now replied, fearlessly,

‘Scant honour from such peril would be won,

For more than life I care for chivalry.

You’ll not persuade me to cross; indeed,

His cavern I’ll now seek, as fate decreed.

I could save myself, to my dishonour,

But worse than death is such salvation;

While, if I go, the worst that can occur

Is that I reach a like destination.

Yet if God directs my arm with vigour,

I live, and send the giant to damnation,

Thousands may, in safety, pass this way;

The greater good the risk does, thus, outweigh;

One life, my own, I risk in this encounter,

To ensure the safety of a countless host.’

‘Go then, in peace, my son,’ said the other,

‘May the Archangel Michael swiftly post

To your side, obedient to God’s order.’

He blessed the knight. Astolfo with utmost

Ardour, pressed on his way beside the Nile,

His hopes set on his horn not sword, the while.

Between the mighty river and a fen,

There ran a trail, along the sandy shore,

Barred by the giant’s solitary den,

From human commerce; there Astolfo saw

The heads, and naked members of dead men,

And even women, set about its door.

From every arch, and window, they were strung;

In every corner, knights and maidens hung.

As, in some Alpine fastness, rich or poor,

A hunter, remembering dangers past,

Will nail some shaggy pelt to his front door,

Or a huge bear’s head and paws, so this vast

Creature, had hung, above, those he’d thought more

Worthy of his attention, at the last.

The bones of other folk lay scattered there;

The ground, and ditches, blood-soaked everywhere.

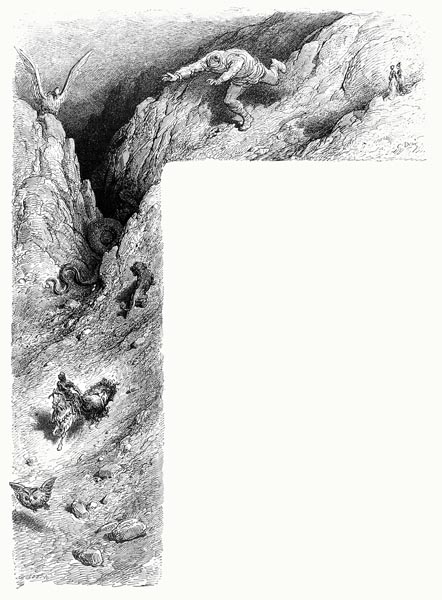

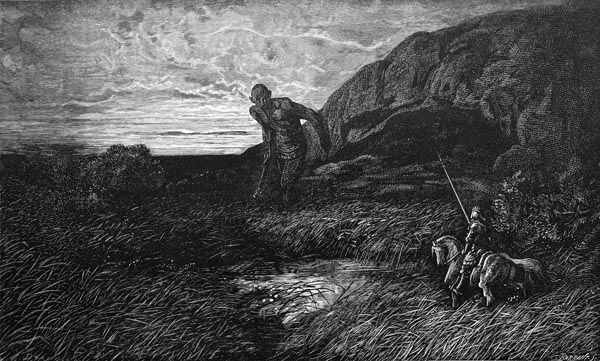

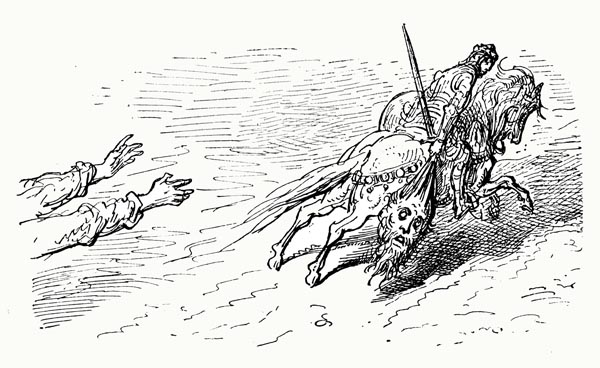

Canto XV: 50-59: Astolfo overcomes the giant, Caligorante

At the threshold, Caligorante stood,

(For such was the pitiless monster’s name)

Whose house was hung with corpses, stained with blood,

As, with cloth of red and gold, folk seek the same.

He scarcely could contain himself, when good

Astolfo down the narrow pathway came,

For two months had gone, and well-nigh a third,

Since a horseman along that way had spurred.

Towards the dense marsh, that hid him from sight,

Being full of tall green reeds, the giant ran,

Wishing to double back behind the knight,

And emerge at his rear, such was his plan,

Then drive him onwards, all so that he might

Trap him in his snare, and then drag the man

To his cave, like those others, previously,

Brought there, as was this knight, by destiny.

As Astolfo approached he saw him there,

And halted, suspecting hidden danger,

Lest his brave charger stray into that snare

Which the hermit had warned of, earlier,

Then to his magic war-horn did repair,

Nor did it fail him now, for its clamour

So struck Caligorante’s heart and head

It shook him to the core, and off he fled.

Astolfo blew again, forever cautious,

Anxious lest pursuit might trip the net.

The felon ran, in a blind careless rush,

For terror robbed him of all sense, as yet;

His fear was so great that, all unconscious

Of the very same trap that he had set,

He stumbled into it, and there was bound;

So entangled, it dragged him to the ground.

Our valiant knight, seeing that mighty fall,

Now safe himself, sped to where he lay,

And left the saddle, swiftly, to forestall

The giant’s rising, and to make him pay

The cost for his most cruel and bloody haul,

But then deemed it dishonourable to slay

So helpless a creature, one tied so tight

He could not stir his limbs enough to fight.

Vulcan, indeed, once forged as strong a net,

With subtle links of steel, and such art,

That he’d have wasted his toil and sweat

That sought to tear its weakest strand apart.

Venus and Mars were trapped, their limbs beset.

The god was jealous, and had, for his part,

Woven, to no less end, fine thread on thread,

Merely to catch that flagrant pair in bed.

Mercury stole it from the smith, likewise,

Seeking to catch young Chloris in that snare,

Sweet Chloris, who behind Aurora flies,

At sunrise, as she travels through the air,

Shedding roses and violets, o’er the skies,

From her robe, and pure lilies, everywhere.

Bold Mercury his trap so deftly set,

One day, he caught her in his airy net.

It seems that she was taken as she flew,

Where Ethiopia’s flood meets the sea,

And in Anubis’ shrine twas placed on view,

At Canopus, for many a century;

After three thousand years, the giant anew

Stole it, and deployed it, mercilessly;

Not only did the vile wretch rob the shrine,

He burned the city, scorning things divine.

He set it then, with care, beneath the sand,

In such a manner that the folk he chased

Towards it, needs but touch a single strand

Ere feet, and arms, and neck were embraced.

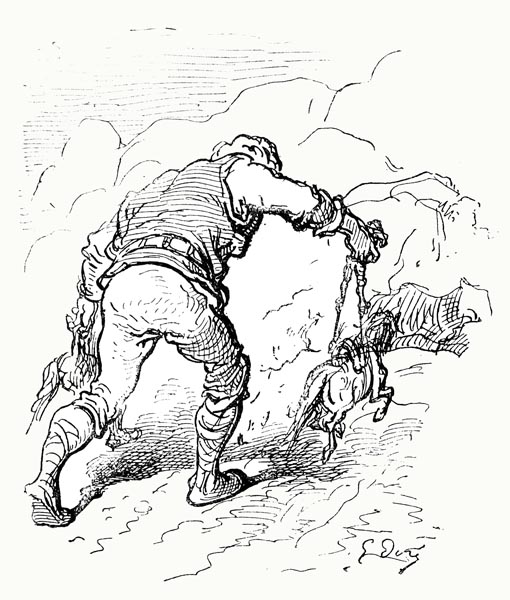

From this, Astolfo took a thread in hand;

The giant’s wrists behind his back he placed,

And tied them, and bound him in such guise

He could not free himself; then let him rise.

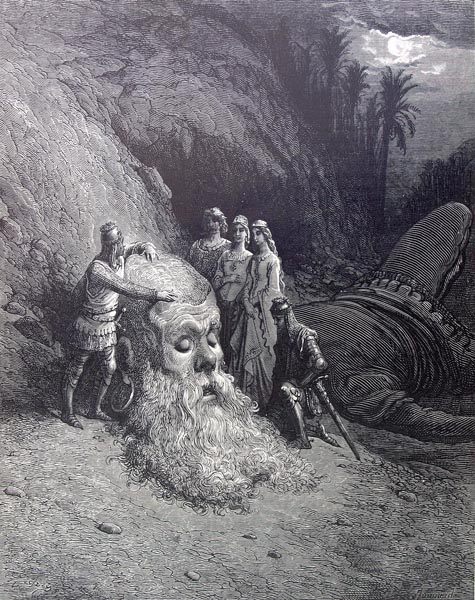

Canto XV: 60-65: He reaches Cairo, where he hears of the robber demon, Orrilo

Next, forgoing the knots (the giant now tame

As any maid), he led him, fast or slow,

Through villages and towns, where’er he came,

And oft would halt, and put the freak on show;

The net as well, for finer none could claim

Was forged beneath the hammer, long ago.

On the giant, as on a mule, it was laid,

And, in triumph, down the road, thus conveyed.

He gave him, too, his helm and shield to bear,

As his squire, while he travelled on his way,

Gladdening all the pilgrims, everywhere,

Since they could pass in safety, night and day.

So well upon his road the knight did fare,

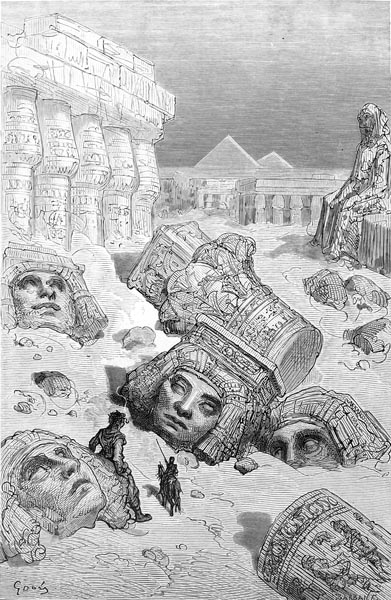

Soon the tombs at Memphis before him lay,

Memphis famed for its Pyramids, and more;

For crowded Cairo, opposite, he saw,

O’er the Nile. All the people came to see

That immeasurable giant passing by,

‘How could one so weak rule, so easily,

One so strong?’ all about, the folk did cry,

Astolfo could scarcely progress freely,

So closely was he pressed yet, by and by,

He freed himself, so that all might honour,

And admire, the knight and his monster.

Cairo was less extensive, in those days,

That it is now, in this our present age,

Where eighteen thousand districts, a maze,

Still cannot lodge all in its wealthy cage;

Tall houses, full three stories high, they raise,

Yet still the people’s needs cannot assuage,

Who oft sleep on the street; the Sultan, there,

Has a wondrous palace, one most rich and fair;

And, therein, fifteen thousand servants lie,

All Christian renegades, beneath one roof,

(Their wives, their families, their horses nigh)

That of their loyalty give constant proof.

The duke desired to view with his own eye

The Nile’s delta, and see how far, in truth,

The river’s flow might penetrate the sea,

At Damietta, where he’d heard lay treachery.

For on the banks of the Nile, at the delta,

A robber had found refuge in a tower,

To travellers, and the natives, a danger;

As far as the gates of Cairo, he’d scour

The countryside, troubling the stranger;

And none could slay him, or thwart his power,

For a hundred thousand wounds he’d borne,

And yet he lived, and put them all to scorn.

Canto XV: 66-74: He finds Orrilo at Damietta, in battle with two brothers

To see if he could break the fatal thread

Of Orrilo’s life (twas the robber’s name);

Wishing to see so foul a demon dead,

To Damietta, next, Astolfo came.

And then he passed to where the river fed

The wider sea, and saw that tower of shame,

And hoped the charmed creature lay within,

Fruit of a faery’s union with a goblin.

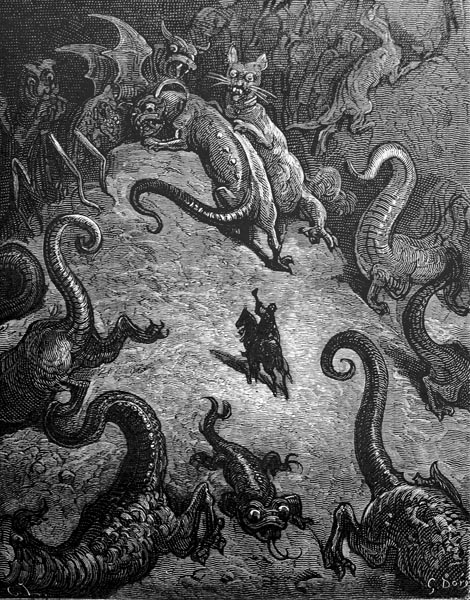

There, he was witness to a cruel fight

Twixt Orrilo and two brave warriors.

Orrilo was alone, and yet his might

Seemed sufficient to defeat their cause,

Though the earthly fame of either knight,

Might have given the vile demon pause.

Aquilante the Black, he there made one,

With Grifone the White, and each the son

Of Oliviero; true the demon came

With a major advantage on his side,

To the battle, since he had brought, that same,

A creature to the field, from out the tide,

Found only in those parts, with a claim

To live beneath the Nile, but yet abide

On shore, and prey on human travellers,

Incautious folk, and careless mariners.

This beast slain by the two, lay on the sand,

Near the harbour, and so they did no wrong

To Orrilo though two gainst one did stand,

And struck at him, and both of them full strong.

For they’d cut from him, say a leg or hand,

Dismember him entire, and yet, ere long,

He’d replace those limbs, as if made of wax,

Despite the fierceness of their twin attacks.

Aquilante and Grifone would cleave

His head down to his teeth, or to his chest;

He’d mock the blows they might achieve,

While they, in vain, attempted his conquest.

He that knows quicksilver, which, I believe,

Alchemists call mercury, can attest

To how each separate scattered silvery ball,

Will reunite with the mass, if he’ll recall.

And if his head was severed by the pair,

He would grope around till it was found;

He’d grasp it by the nose, or by the hair,

And re-attach it, plucked from off the ground.

Though oft Grifone hurled it through the air,

Into the flood, in vain the thing was drowned;

For Orrilo swam, straight to the river bed,

And emerged, in possession of his head.

Two lovely ladies, beautifully dressed,

The one in black, the other all in white,

The battle being fought at their behest,

Stood by to gaze upon the savage fight.

Two faeries were they, both with kindness blessed,

Who’d nourished one, and the other, knight,

Oliviero’s sons, after they’d been torn

From the clutches of two great birds, one morn,

That had snatched them away, in Gismonda,

And carried them far from that country,

But no more of that tale need I utter,

For all the world has heard their story;

Though the author has misnamed the father,

Mingling one with another history.

Now, the battle had been set in motion

At these lovely ladies’ instigation.

The sun, in that place, had already set,

And off to the Fortunate Isles had run;

Beneath the moon, the deepening shadows met,

Ere, for lack of light to see, the fight was done.

The sisters, white and black, pleased to forget,

(Orrilo, to the tower, his way had won)

The failure of their knights, and so defer

The fight till a new day would light confer.

Canto XV: 75-78: The fight is deferred till the following day

Astolfo, who’d recognised Grifone

And Aquilante by their insignia,

As much as by their skill in every

Blow, was swift to greet them, they moreover,

Knew, in this knight who’d won a victory

Over the giant whom he led a prisoner,

The Baron of the Leopard (for twas so

He was named at court) greeting him also.

The two ladies, to grant the knights some rest,

Led them to a sumptuous palace nearby,

Where squires and maids, in fine garments dressed,

Lit their way with torches, and, by and by,

Some led away their horses, while the rest

Took their armour; in a garden, on high,

They saw the tables for a feast now laid,

Close to where a pleasant fountain played.

Astolfo tethered the giant, securely,

Fastening him, with a great length of chain,

To an ancient oak, both tall and mighty,

Quite sufficient, he thought, to take the strain,

While ten officers guarded him closely,

Lest the giant should free himself again,

And attack them, and cause a deal of harm,

Before any there could sound the alarm.

At this rich and sumptuous occasion,

Where the food itself was the least delight,

The major topic of conversation,

Was Orrilo, and the wonders of the fight;

For one and another sought the reason

For his strange ability to re-unite

His severed parts and, re-attaching all,

Return to the fray, after every fall.

Canto XV: 79-81: Astolfo determines to slay Orrilo

His book Astolfo opened then, and read

(For it contained a counter to the charm)

That if he could pluck one hair from its head

Then he could do the demon lasting harm,

Or leave the monster lying there, stone dead,

Could he but grasp that hair, and wield his arm.

So, the volume said, yet failed to say

Where, amidst those tufts, the one hair lay.

The duke rejoiced in hopes of victory

As though the palm was already won,

Anticipating that a blow or three,

Would suffice to see the wretch undone.

And convinced the brothers that only he

Should seek to shoulder the burden, or none.

Orrilo he would take in hand, and slay,

If the two of them would not say nay.

They granted it, however, willingly,

Though believing his toil would prove in vain;

A new dawn broke, and they arose to see

Orrilo fast descending to the plain.

The duke and he then battled furiously,

Sword against mace, down the blows did rain,

Astolfo waiting on the stroke that might

Part that vile spirit from the flesh outright.

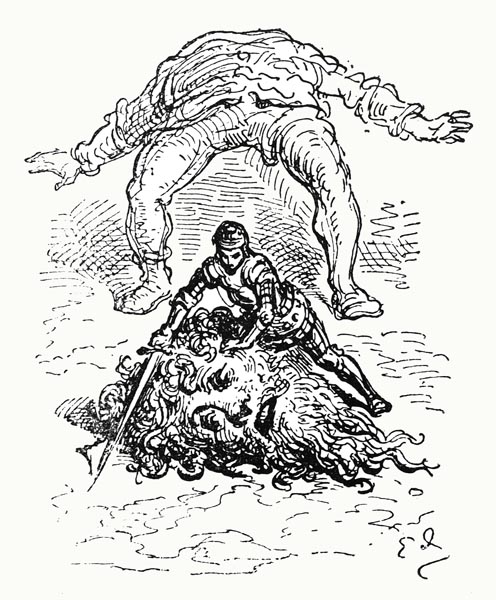

Canto XV: 82-87: And succeeds in conquering him

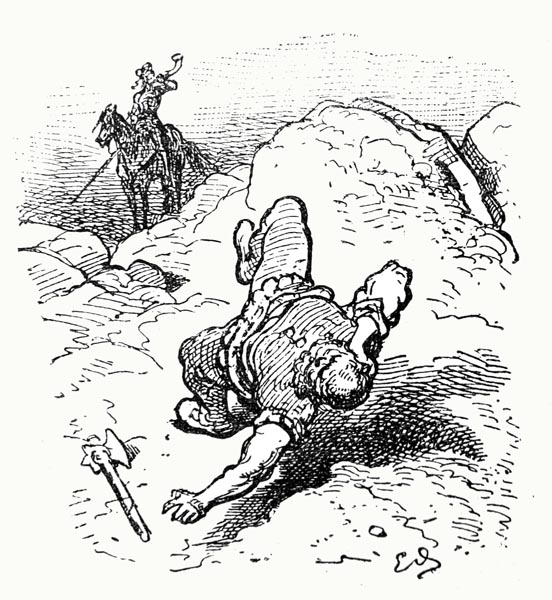

He cut away the hand that grasped the mace,

Then one, and then the other, arm as well;

Pierced through the breastplate, in every place,

While he trimmed him all around, as he fell;

But Orrilo a hail of blows would face,

Then repair himself, as sound as a bell

Once more; though sliced in a hundred parts,

He thus pursued the fight, in fits and starts.

After a thousand cuts, one solid blow

Landed twixt the shoulders and the chin,

And lopped the head and helmet from the foe;

Astolfo leapt that fallen part to win,

Sprang to his horse again, and off did go,

Gripping it by the hair, blood red as sin;

All along the bank of the Nile he fled,

So that the wretch might not regain his head.

The fool, not seeing Astolfo’s deed,

Still was searching for the head, on the ground,

But, hearing the pounding hooves of the steed,

As the knight fled, and following the sound,

Mounting his charger, he pursued at speed,

Ready to go where’er the knight was bound,

And would, indeed, have cried out: ‘Stay, man, stay!’

Had the duke not snatched his mouth away.

Yet, pleased that the knight had not, likewise,

Removed his heels, he drove his horse amain.

Rabicano, though, fast as the lightning flies,

Had now consumed a vast part of the plain,

While our Astolfo was casting his eyes

Over the hair, again, and yet again,

Searching to find the single entity

That granted the wretch immortality.

Amid the innumerable hairs, no one

Appeared to be much crisper or straighter,

What then, Astolfo thought, was to be done,

Since he sought to slay the demon robber?

‘Better,’ he thought, ‘to cut them all than none!’

And, since he lacked scissors or a razor,

He had swift recourse to his gleaming sword,

So sharp a decent shave it would afford.

So, gripping the severed head by the nose,

He sheared the locks, behind, atop, before,

And cut the one amongst the rest, I suppose

That held the charm; the visage, wounded sore,

Turned up its eyes, its life now at the close,

While every mark of looming death it bore.

Then the body, still severed from its head,

Fell from the saddle, and the wretch was dead.

Canto XV: 88-94: The three knights set out to visit Jerusalem

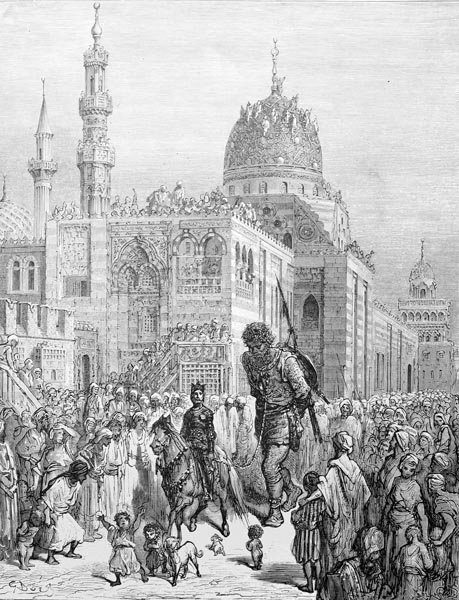

The knight returned, the robber’s head in hand,

To where the ladies, and the brothers, stood,

And, pointing to the body on the sand,

He raised the gory emblem stained with blood.

I know not, though all had gone as planned,

If they praised him as fully as they should,

(He’d robbed the knights of victory) for they

Received him in a sadly human way.

Nor do I think the ladies felt happy,

That the battle had ended as it did,

Since that display of knightly chivalry,

Far away from war in France, was a bid

To keep the brothers from their destiny,

And (met with Orrilo) that path forbid;

In hopes that their fate they might delay,

Till the starry influence passed away.

As soon as the castellan was notified

In Damietta, that the thief was dead.

He let loose a pigeon, having tied

A letter to one leg, with a strong thread.

She flew to Cairo and, thus, country-wide

The news of vile Orrilo’s death was spread,

(As was their practice) till, to all, twas plain,

Throughout Egypt, the demon had been slain.

Since he’d brought the business to an end,

Astolfo now consoled the noble pair,

Suggesting Holy Church they might defend,

And the cause of Charlemagne, far from there;

(Though he found that he had no need to bend

Them to his wish, since they were well aware

Of the war) for to quit the East were best

And journey to seek honour in the West.

Aquilante and Grifone took their leave

Of their respective ladies, and withdrew;

They, though the knights’ departure could but grieve

Them deeply, knew no means to keep the two.

The duke turned landwards, yet not to deceive

The pair; twas that his thoughts had turned anew

To viewing the sites where God incarnate

Had dwelt, ere he again embraced his fate.

They might have taken the seawards route,

It being less hilly, and more pleasant,

Never to leave the shore, in their pursuit

Of the road, yet he chose, in but an instant,

To take the shorter path, as that did suit;

For he knew that along the coastline scant

Sites with fresh grass, or drinking water, lay;

Here, Jerusalem was but six days away.

Before our travellers took to the road,

They gathered all they needed together

And to the giant’s back they tied their load,

That might have borne a weight far heavier.

A hill, to them, the nearer distance showed,

Before their harsh and stony ride was over:

That sacred hill, on which Heavenly Good

Purged us of all our sins, with His blood.

Canto XV: 95-99: They meet Sansonetto, governor of the Holy Places

They met, at the entrance to the city,

A noble young man, whom the brothers knew,

Sansonetto of Mecca, for chivalry,

Well-respected all that country through,

And for his goodness, and his prudency,

Wise beyond his years, and ever true;

Converted to our faith by Orlando,

Baptised at that warrior’s hands also.

They found him with the Caliph of Egypt,

Designing a defensive wall around

The Mount of Calvary; this, by his edict,

Was to be two miles in length, and surround

The hill completely, and yet with no strict

Countenance they were met, for sound

And kindly was the heart that it betrayed.

With him their entry to the fort they made.

He was the ruler of the Holy Land,

And, for Charlemagne, he governed that place.

Astolfo, who good manners did command,

Gifted him the giant, who for a space

Had borne a mighty load, quite as grand

As ten cart-horses might have had to face.

He gifted him the giant and better yet

His means of catching him, that ancient net.

Sansonetto in return, at this encounter,

Gave him a rich and fine belt for a sword,

And costly spurs, wrought for a warrior,

And a golden buckle, fitting for a lord.

All these, twas thought, the knight wore earlier,

That freedom to a maiden did afford,

And slew the dragon; all from Jaffa brought,

When he’d captured the city, and its court.

Once purged of sin in a monastery,

From which the odour of good works arose,

They contemplated every mystery

Of the Passion, for every shrine they chose

To visit, which, with many an infamy,

The Moors now to our holy pilgrims close.

(Europe’s in arms, and war is everywhere,

And yet our hosts, in arms, are needed there.)

Canto XV: 100-105: Of Grifone and his beloved, Orrigille

While our three knights, with humble spirits, sought

Penitence, and sacred ceremony,

A Greek pilgrim, Grifone knew, now brought

News, from afar, that distressed him sorely,

(From his first vow, and former train of thought,

So distant as to disturb him wholly)

This inflamed his breast, now filled with care,

And distracted him, utterly, from prayer.

To his misfortune, he loved a lady,

The name of this maid was Orrigille,

Not one in a thousand matched her beauty,

Her form and visage ever lovelier;

Yet, by nature, so fickle, and flirty,

Was she, you might search the whole world over,

Every continent or island in the sea,

Yet ne’er find one so born to treachery.

In Constantinople, he had left her,

Suffering from a fever, that lady.

He’d hoped to find her, lovelier than ever,

On his return, and seek her company.

Now, he heard, the witch had with a lover,

Sailed forth, for Antioch across the sea,

Declaring she would never sleep alone

While the flower of youth she yet did own.

From the moment Grifone heard the news,

He ne’er ceased his lament, night or day;

Whate’er pleasure the busy world pursues,

Seemed but to vex him, more than I can say,

(Let him reflect, who Love’s court doth choose,

How finely tempered are his darts in play)

While all the more grievous was his pain,

In that his shame was too great to complain.

And this because a thousand times before

Aquilante had reproved him for that love,

Begged him to banish it from his heart’s core,

Being wise, and reluctant to approve

This foolish maiden, who he felt was more

Fickle than all others, and so would prove.

The knight forgave her, despite his brother;

It seems we prize our own opinion ever.

Therefore, without telling Aquilante,

He thought to ride to Antioch alone,

And carry her away, who, so sweetly,

Had borne away his heart as twere her own;

And find him who’d taken her and, swiftly,

Wreak vengeance on him, such as few had known.

I’ll relate what came of this, every word;

My next canto shall tell all that occurred.

The End of Canto XV of ‘Orlando Furioso’