Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XIV: Mandricardo, Doralice, and Rodomonte

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XIV: 1-9: Of Charlemagne’s army, and of the Battle of Ravenna (1512)

- Canto XIV: 10-29: King Agramonte reviews his troops

- Canto XIV: 30-33: Orlando appears in the field

- Canto XIV: 34-37: Mandricardo searches for the knight in black

- Canto XIV: 38-48: He attacks the guards of the King of Granada’s daughter

- Canto XIV: 49-56: He carries off the lady, Doralice

- Canto XIV: 57-64: She is soon consoled; they come upon two knights and a maiden

- Canto XIV: 65-67: Meanwhile Agramante prepares an assault on Paris

- Canto XIV: 68-74: Charlemagne’s prayer on the eve of battle

- Canto XIV: 75-82: The Archangel Michael seeks out Silence and Discord

- Canto XIV: 83-86: Not finding Silence, he meets with Discord first

- Canto XIV: 87-90: He enquires of Fraud regarding Silence

- Canto XIV: 91-95: The House of Sleep

- Canto XIV: 96-98: Michael, with Silence’s help, speeds Rinaldo to Paris

- Canto XIV: 99-103: Charlemagne prepares to defend the city

- Canto XIV: 104-108: His state of readiness

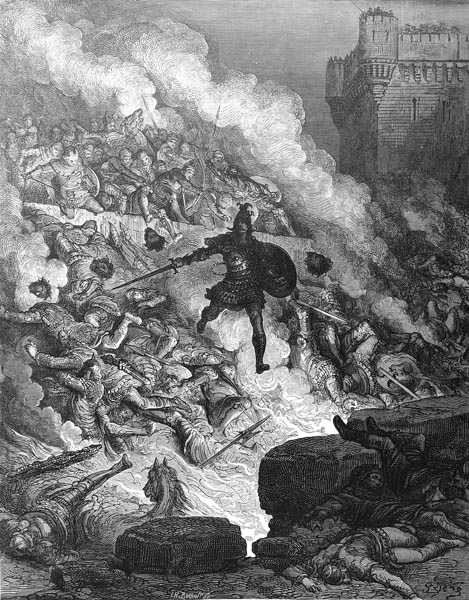

- Canto XIV: 109-116: Rodomonte, King of Sarza, initiates the attack

- Canto XIV: 117-121: He scales the wall

- Canto XIV: 122-128: And sets about the Christian defenders

- Canto XIV: 129-134: Many Saracens are destroyed at the inner moat

Canto XIV: 1-9: Of Charlemagne’s army, and of the Battle of Ravenna (1512)

Those of France, those of Africa and Spain,

In many a battle twixt foe and foe,

Had left a host of dead among the slain,

To feed the eagle, wolf and greedy crow;

But though the many Franks had bled in vain,

Losing the land about them, at a blow,

Great to the Saracens had proved the cost,

Many a great Moorish prince and lord was lost.

Indeed, so bloody was their victory,

It left them little they might cheer about;

And if we may compare the wars, we see,

With those of former times, there is no doubt,

That Duke Alfonso’s deeds with his army,

At Ravenna, the Spaniards put to rout,

And which redound to his praise and glory,

Were part of a not dissimilar story.

When the Gascons and the Picards did yield,

And those of Normandy and Aquitaine,

He, in their midst, with sword and shield,

Assailed the near-victorious troops of Spain.

While a host of brave men upon that field

Took his lead, and followed in his train,

Whom on that day he granted due reward

Of the gilded spur, and the gilded sword.

With the spirited heart that he bore,

Near, or never far from, present danger,

He broke the golden oak-tree, and tore

Apart its red and yellow fruit, forever

Deserving of the laurels which he wore,

Saving the Fleur-de-lys from dishonour.

And one more garland he earned also,

By preserving, for Rome, brave Fabrizio.

That Colonna, pillar of the Holy See,

Whom he captured there, and kept whole,

Granted him more honour, in victory,

Than if his hand had achieved the goal

Of routing all who rich Ravenna’s country

Sought, yet fled again, nigh every soul;

Castile’s standards, Aragon’s, Navarre’s,

Left, to be gathered by this son of Mars.

That hard-won victory brought more relief

Than joy; for the loss of our French captain,

Gaston de Foix, brought us but pain and grief,

And then, the deaths of many more again;

That storm took brave commanders-in-chief,

Glorious princes, fighting to maintain

Their own lands, or wide realms of their allies,

That o’er the frozen Alps had sought the prize.

Our safety and our lives, were, thus, ensured.

By that great victory, we were protected

From harsh winter, the storms that are abroad,

That angry Jove, from out the sky, projected.

Yet joy we cannot feel, nor feasts afford,

Seeing the widows by such pain affected,

Who, dressed in black, still lamenting, go,

Amidst a grieving France, and cry their woe.

There’s need now for King Louis to provide

Fresh captains for the field, fresh companies,

That to restraining greed should be applied,

To guard the honour of the Fleur-de-lys,

From men that monks and nuns, far and wide,

Have harmed, black, white and grey; that seize

On wives and daughters, brides, on Christ divine

Stealing the silver from his sacred shrine.

Wretched Ravenna, twere better if you

Had not, indeed, resisted the victor,

Warned by Brescia’s fate, as you, anew,

Give warning to Rimini and Faenza.

Come, Louis, let old Trivulzio go

Among your squadrons, and teach them, ever,

Greater restraint, and show what wrong has bred,

Italy’s cities heaped now with the dead.

Canto XIV: 10-29: King Agramonte reviews his troops

As the French king needed knights a plenty,

Now, to replace his captains that were slain,

So Marsilio, and Agramante,

There, had need to marshal their troops again,

And, filled with that intent, wished to see

Them, out of winter quarters, on the plain,

So, they might review their every need,

And their good governance be then decreed.

Marsilio first, then King Agramante,

By company, inspected all their men,

The Catalonians headed the army

Of Spain, Dorifebo was made captain.

Next, without their king, Folvirante,

Whom the hand of bold Rinaldo, ere then,

Had slain, came the soldiers of Navarre,

Isolier named to be their guiding star.

Balagante led the forces from Léon,

Grandonio commanded the Algarbi;

Falsirone, Marsilio’s brother, won

Lesser Castile, and all that company;

Men followed Madarasso’s ‘gonfalon’

Out of Malaga, and fair Seville’s city,

Where the great Guadalquivir’s waters play

Twixt Cordova’s rich fields and Cádiz Bay.

Stordilano, Baricondo and Tessira,

Together, displayed their brave companies;

The first led the troops from Granada;

While the second, he commanded, with ease,

The warriors who came from Majorca.

Larbino had of Lisbon held the keys,

Now Tessira ruled his men; Serpentino

The Galicians, for Maricoldo.

Those of Toledo and Calatrava,

Who’d marched beneath bold Sinagon’s flag there,

With those from beside the Guadiana,

That, in bathing, its crystal waters share,

Were governed now by brave Matalista;

While Bianzardin now had in his care,

Salamanca, Piagenza, Astorga,

Palencia, Avila and Zamora.

Those from Zaragoza, and from the court

Ferrau now led, for King Marsilio;

And to that well-armed captain did report

Bold Balinverno, and Malgarino

Malzarise and Morgante, who, in short,

Had lost their realms, and being exiled so,

Had turned to Marsilio; he as friends

Received them, now they furthered his own ends.

The king’s bastard was in his company,

Follicon d’Almeria, with Doricante,

Analardo, Largalife, Bavarte,

And that most cunning lord, Archidante,

The brave Langhiran, and Lamirante,

And many another of whom I’ll write

If e’er the time comes to display their might.

When the Spanish host had passed on by,

In fine style, before King Agramante,

The brave King of Oran now caught the eye,

Almost a giant in stature, and, sadly,

Those who for Martasino gave a sigh,

That was dealt his death by Bradamante,

Pained the warrior-maid had with such ease

Slain that fine king of the Garamantes.

The third company was Marmonda’s,

Whom Argosto had slain in Gascony;

Both it and the second now lacked leaders,

As did the fourth, thus demanding three

Fresh warriors now to lead them onwards,

Agramante feigned to ponder, briefly;

Buraldo, Ormida, Arganio,

Upon those three their care he did bestow.

Arganio’s troops, from Libicana,

Still wept for dark-skinned Dudrinasso,

Brunello ruled those from Tingitana,

With clouded visage, and a look of woe,

For in the woods, not far from the tower

Atlante raised o’er the mountain plateau,

He had lost the ring to Bradamante,

And, thus, was in disgrace with Agramante:

If Isoliero, Ferrau’s brother,

Who found Brunello there, tied to the tree,

Had not explained the truth of the matter,

To the king, they’d have hung him instantly.

The monarch his mind, at length, did alter,

At the request, it would seem, of many,

(The noose was round Brunello’s neck) but swore

To hang him, if the man offended more;

Which was the reason that Brunello rode,

With lowered brow, and sad demeanour.

Came Farurante, on whom were bestowed

The foot and horse once led by Maurina.

Behind them, a new-made monarch followed,

Leading the troops drawn from Constantina,

Libanio, the gold crown on his brow,

Once Pinador’s, but gifted to him now.

Hesperia’s men were ruled by Soridano,

The soldiers from Setta by Dorilon,

The Nasamonians by Puliano;

Agricaltes the Amonians led on,

And Malabuferso those from Fizano;

Finadurro led many a squadron

From the Canary Isles and Morocco,

Balastro took the place of King Tardocco.

Next, the troops of Mulga, and Arzilla,

Mulga still captaining his former band,

The second leaderless, thus, the tiller

The king now set in Corineus’ hand,

While the soldiers from Almonsilla,

Once Tanfirion’s, by Caico did stand;

Those from Gaetulia by Rimedonte;

Those from Cosca by Balinfronte.

The Bolgans’ king was now one Clarindo,

Gifted brave Mirabaldo’s vacant throne.

Then came that earthy figure Baliverso,

Amongst the host his bawdy was well-known.

I think no banner, mid that mighty show,

Above a firmer troop of men was flown

Than that of the valiant king Sobrino,

No Saracen more cunning gainst the foe.

Bellamarina’s men whom Gualciotto

Used to lead, now served the King of Algiers,

Rodomonte of Sarza, who did show

Fresh strength in infantry and cavaliers;

For this king who’d been sent some time ago,

(When in the Centaur and the Goat appears,

The clouded sun) to his African shore,

Seeking men, had returned three days before;

In all the Moorish camp none was stronger,

No Saracen proved bolder, than that king.

And in Paris, rightly, their fear was greater

Of him, midst Agramante’s following

And Marsilius’ than any other

Whom they’d brought to France, or could ever bring.

And, more than any in that company,

To our faith this king proved an enemy.

Came the Alvarrachians’ king Prusione;

And the Zumarans, to Dardinello

Subject; I know not if, on their journey,

From some ruined tower, an owl or crow,

Or other bird of ill-omen, loudly

Cried to one or the other, there below,

That, appointed by fate, the hour was nigh

When both, upon the battlefield, would die.

No more remained but the companies

Raised from Tremisenne and Norizia;

Yet no sign or news had appeared of these;

Both had been expected at the muster.

King Agramante, though, was not at ease,

Knew not what to think, and could but wonder

At the thing, when a squire his presence sought,

Sent by Tremisenne’s king; ill news he brought.

He claimed that Manilardo, Alzirdo,

With all their host, lay dead upon the plain.

‘Sire,’ said the man, ‘the bold and mighty foe,

Who slew our friends, would all the rest have slain,

If they to beat retreat had been as slow

As I, that escaped with no little pain.

This man kills cavalry, and infantry,

As a wolf does goats and sheep, and as swiftly.’

Canto XIV: 30-33: Orlando appears in the field

Now there had come, some few days before,

To the Moorish camp, a warrior lord;

In the West, in the Levant, none was more

Blessed with strength, or did skill afford

To equal his; much honour there he saw,

And much royal grace to him was assured,

Mandricardo his name, of King Agricane

The son, succeeding him, in Tartary.

He was renowned for many a glorious deed,

For all the world had heard of his success,

Exalted by his winning, twas agreed,

In that keep, of the Syrian enchantress,

The shining armour that once clad, indeed,

Two thousand years before, more or less,

The form of Trojan Hector; none could tell,

Without dread, the events that there befell.

Now present, when this melancholy word

Was uttered, he raised his head on high,

Disposed to go, ere others were preferred,

And find this warrior, if he were nigh,

But said naught of it, lest some other heard,

Fearing it might be thought bravado by

His peers, or, even worse, that his brave sword

Might be rejected, and his pleas ignored.

He asked the squire how the knight was dressed,

And of the ensign or emblem that he bore:

He replied that he showed no flag or crest,

His shield was black, and black the clothes he wore.

So it was, for all he said I, now, attest,

Orlando all such ornament forbore,

And since his heart within was in mourning,

Just as dark was all his outer clothing.

Canto XIV: 34-37: Mandricardo searches for the knight in black

Marsilio had gifted Mandricardo

With a fine bay horse, chestnut in colour,

Its tail and mane black, and the legs below,

Frisian its dam, Spanish its father.

Mandricardo, once armed from tip to toe,

Mounted this brave steed, and galloped after

The foe, and swore that thus he’d turn his back

On the camp, till he’d found this knight in black.

Many a frightened fugitive he met,

Escaping from Orlando’s weighty hand,

Some grieving for a son caught in his net,

Or a brother, whom they had seen unmanned.

Ever a colourless face, still pale and wet,

Did the cowardly, and the sad, command,

As, fearful yet, they hastened on, in flight,

Mude pallid, and insensate, from this knight.

He had not ridden far before he saw

A cruel and most inhuman spectacle,

Witness to all he had heard before,

Regarding the site of their debacle,

And searched, midst those fatalities of war,

Lest one was saved, by some miracle,

While moved by a strange envy of the man

That had slaughtered so many, as they ran.

Like a mastiff or wolf, that comes upon

A dead bullock the herdsman’s left behind,

And sees but horns and bones, the rest now gone

To feed the crows, and their ravenous kind,

And glares at useless remnants, here and yon,

So, the barbarous king reviewed his find,

He cursed, lamenting, like some savage beast,

At having come too late to that great feast.

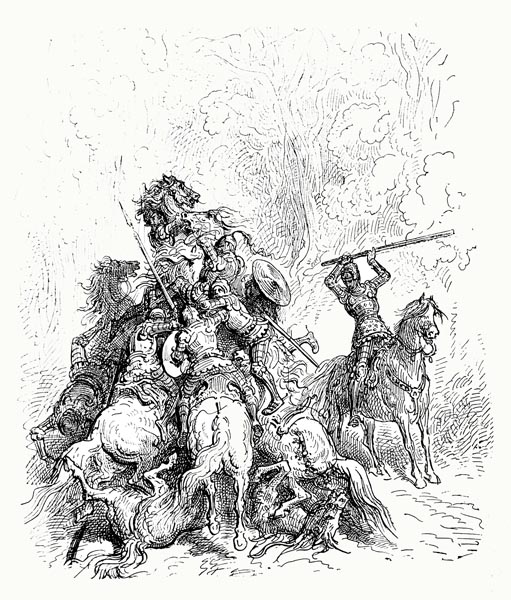

Canto XIV: 38-48: He attacks the guards of the King of Granada’s daughter

That day, and half the next, he searched around,

Seeking the knight in black, loudly calling.

Behold, a space, dusk shadowing the ground,

And there a river, past the meadows winding,

In tight, sinuous curves, to form their bound,

A narrow space between each, in its flowing;

A like set of close bends the Tiber makes,

Near Otricoli, as its course it takes.

Where this river might be crossed, he saw

A crowd of well-armed warriors and, seeking

To know their purpose on the further shore,

He questioned them, their captain answering,

Moved by his manner, and the garb he bore,

All his gear with gems and red gold gleaming,

Quite rich enough for it to illustrate

Some great man, whose word there carried weight.

‘We accompany the daughter,’ he replied,

‘Of the King of Granada; to be now

Rodomonte the King of Sarza’s bride,

Though tis little known, I would allow;

And we’ll convey her, this evening-tide,

While only the cicadas on the bough

Can be heard, into her father’s keeping,

Within the Spanish camp; she’s still sleeping.’

This lord, who held all others in disdain,

Sought to determine now how well they might

A defence of the lady, thus, maintain,

Whom they were to accompany that night.

‘The maid, from what I hear, is far from plain,

And it would please me greatly to have sight

Of her,’ he said, ‘so lead on, while tis day;

And, swiftly now, ere I pursue my way.’

‘You must be mad, indeed!’ the other cried.

At the Granadan, then, with levelled lance,

The Tartar, not a man to be denied,

Flew, and through him did the point advance,

Steel armour failed to turn the blade aside;

And to the ground he fell, dead perchance.

Agricane’s son his weapon swift regained,

Unarmed, in truth, if there it had remained,

Since the king bore neither sword nor mace;

For when Trojan Hector’s armour he’d won,

Finding never a true blade in that place,

He was obliged to swear, ere all was done,

That Orlando’s sword his armour would grace,

And that, until that time, he would bear none;

Durindana, the blade Almonte bore,

Orlando’s now, was Hector’s long before.

Great was the monarch’s daring, who now chose,

Though disadvantaged, to extend the fight;

With levelled lance, advancing on his foes,

Shouting, in fury: ‘Who shall thwart this knight?’

Some pointed their spears, others drew close

Upon him with their swords; with all his might,

He laid about him, and a host he slew,

Before his shattered lance to pieces flew.

Nonetheless, he gripped the broken shaft,

In both hands, its wood still strong and sound,

And then swept that brave remnant fore and aft,

Laying the foemen dead upon the ground;

Nor ere was havoc wreaked with greater craft.

Like to the jawbone Samson whirled around,

In slaying all the Philistines, just so,

He crushed helm, shield, knight, charger, at a blow.

To hasten to that fight, the wretches vied,

Nor did they cease because their friends were slain,

And yet the vile manner in which they died,

(More bitter than death itself, I’d maintain)

Stole not only life, but each warrior’s pride;

Struck by that lance-shaft, bitter was the pain

They felt, beneath its pounding, to forsake

This life, crushed, broken, like some frog or snake.

But then deciding, once they viewed the cost,

That it was ill to die in any guise,

And with two thirds of them already lost,

The rest now thought it better to be wise,

And fled, although the pagan, thwarted, crossed,

Feeling that they’d robbed him of his prize,

Determined that, from that desperate strife,

Not a man there should escape with his life.

As reeds in a dry fen are soon consumed,

Or stalks in a stubble field, by the fire,

(Set by some careful farmer) swiftly doomed,

As the wind-blown flames rise ever higher,

Halt for a moment, then, their course resumed,

Speed through the furrows, ere they can expire,

To the sound of crackling and snapping, so

None could defend against this Mandricardo.

Canto XIV: 49-56: He carries off the lady, DoraliceHe attacks the guards of the King of Granada’s daughter

Finding his path free of all obstruction,

Now unsecured, without a guard in sight,

Following clear tracks in that direction,

Midst cries of loud lament, the Tartar knight

Made his way, to execute his intention,

Of discovering if the lady was, on sight,

As lovely as was claimed; from the dead

He rode, since to the river these prints led.

In the middle of the meadow, he saw

Doralice, such was the lady’s name,

Who, neath an ash tree, on the grassy floor,

Her miserable fate did now proclaim.

In a bright flowing stream, her tears did pour,

Down her breast, to more than wet that same,

And, from the pallor of her face, she appeared,

To mourn the dead, while for herself she feared.

Her fear increased as he now approached her,

Stained with blood, dark and impious of face,

And loud cries rose to the skies above her,

From her, and all her people in that place,

For as well as the knights who had led her

To the river, older men, there, did grace

Her presence, and many a dame, and maid,

The fairest that Granada’s realm displayed.

When the Tartar king viewed that fair visage,

Unequalled for its beauty, throughout Spain,

And where amid the tears (what wars he’d wage

To see her smile) Love newly forged his chain,

He knew not if heaven or earth were her stage,

And from his victory naught else did gain

But this: that he was captive now to her,

Imprisoned, yet knew not in what manner.

However, he balked at thus conceding

To a maid all the fruits of his labour,

Though it was plain from her bitter weeping

That she grieved, as much as woman ever,

And hoping, now, to turn her lamenting

To joy, he determined to console her,

So, setting her upon a white palfrey,

He now prepared to resume his journey.

The ladies and the men, and every maid,

Who’d accompanied her from Granada,

He benignly dismissed: ‘Be not afraid,’

He cried, ‘I shall be her guide, none better,

And lord, and master, yet she’ll be paid

Due respect, to all her needs I’ll cater;

So, farewell!’ Thus, unable to undo

The harm, her folk, with tears and sighs, withdrew;

Crying: ‘How distraught will be her father,

When he hears of her miserable state!

How great then the bridegroom’s grief and anger,

And the revenge he’ll exact, for her fate!

O why, in this time of need and danger,

Is there no knight nearby; ere tis too late

To save the ancient blood of Stordilano;

Ere she has vanished where none can follow?’

The Tartar king, content with his fair prize,

Which he’d won by chance, and through his valour,

Seemed to lack the urgency (tis no surprise)

He’d possessed, to follow and chase after

The knight in black; and, in wandering guise,

Now fast, now slow, looked about for shelter,

For some convenient and fitting place,

Wherein his fond desire he might embrace.

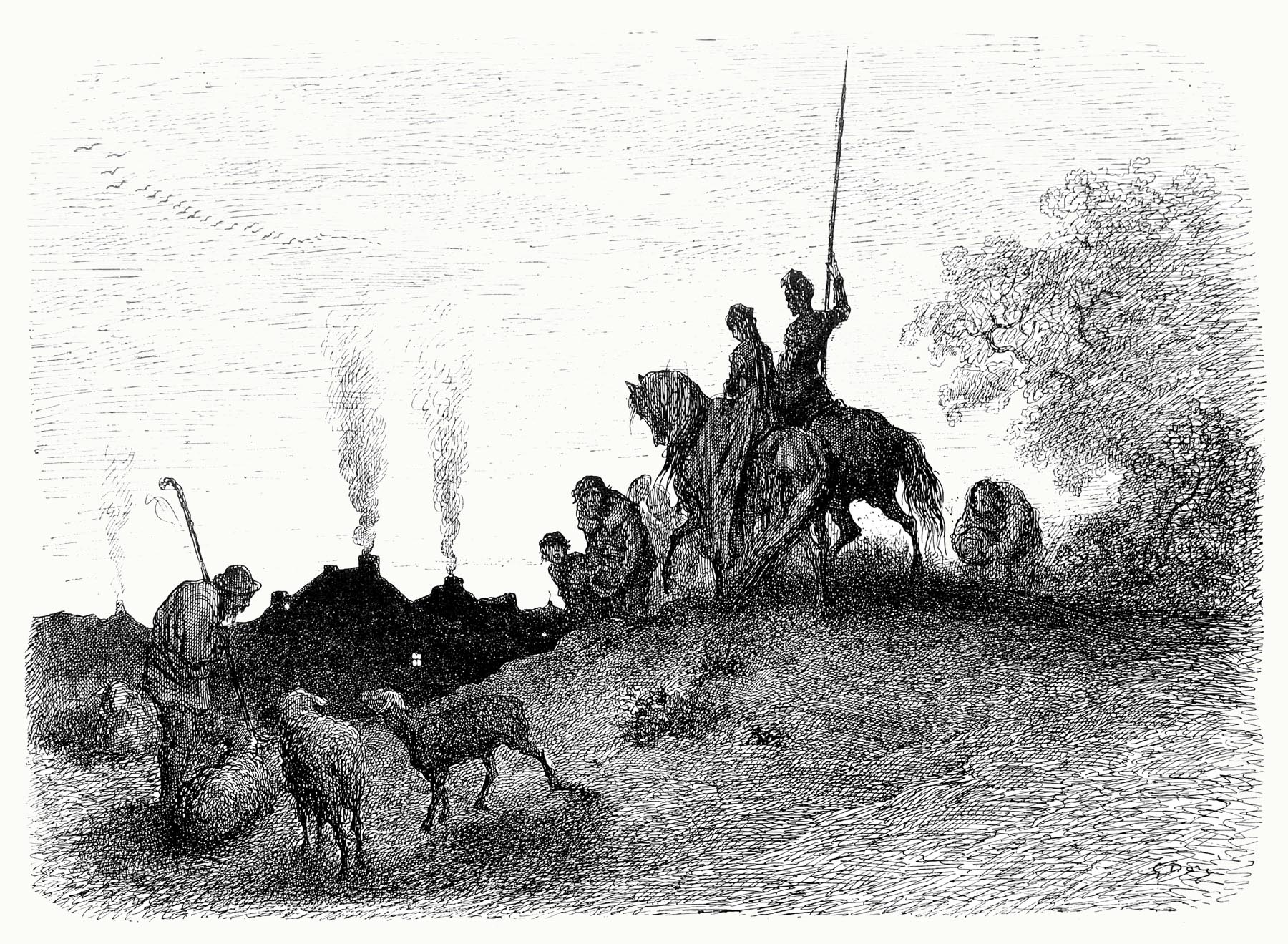

Canto XIV: 57-64: She is soon consoled; they come upon two knights and a maiden He attacks the guards of the King of Granada’s daughter

Doralice, he comforted the while,

Her fair cheeks wet, her bright eyes filled with tears,

Feigning many things, in masterly style;

How, hearing of her, he’d loved her for years,

And how his land, of many a square mile,

Was praised for its vast size by all his peers,

Which he’d quitted not to view France and Spain

But that the sight of her face he might gain.

‘If a man ought to be loved, for loving,

Then your love I deserve; if by birth,

Then who is nobler born, remembering

Agricane’s my father? If by worth,

As measured in riches, who in counting

Has more than I, that dwells upon this earth?

If by valour, I think this day I’ve proved

That for valour I merit being loved.’

With these words and others, Love dictated

And set there on Mandricardo’s tongue,

He sought to ease a heart by sorrow weighted,

That unhappy maid’s, by her fright unstrung.

Her fear ceased, and then her grief abated

With the tears that her fair cheeks had stung.

And then, with greater patience, she began

To give closer attention to the man;

And, thus, with much more courteous replies

She showed herself both kindly and pleasant,

And sometimes there was pity in her eyes,

Though her averting of her gaze was frequent.

The pagan then, more certain of his prize,

Having played Love’s game before the present,

No longer hoped but thought the lady would

Resist him not; such things he understood.

In her pleasing and happy company,

Which brought him satisfaction and delight,

Near to the hour when all would hope to see

A shelter from the cold, to pass the night,

Now the setting sun, half-hidden, silently

Dipped lower, more swiftly rode the knight,

Until they heard a fluting reed-pipe sound,

And came upon a hut, smoke wreathed around.

It was a country dwelling, much less fair

Than spacious, built for convenience;

For a courteous herdsman he lived there,

Who welcomed them, a good man, full of sense,

Whose table pleased, despite the rustic fare.

Not only castle halls show the presence,

Or cities, of true people who prove kind,

Oft the like in cottages and huts we find.

As to what took place, later, in the darkness,

Twixt the maiden and Agricane’s son,

I was not there, and so am not a witness;

Others I’ll leave to judge whate’er was done;

Yet, as they seemed happier, nonetheless,

When they arose to share the morning sun,

Both appeared in accord, while the maiden,

For his kindness, sweetly thanked the herdsman.

They roamed, then, from one place to another,

But found themselves, at last, upon the shore

Of a river that, in silence, chanced to wander

To the sea, though its flow was most unsure,

Yet clear, such that the light on the water

Fell unbroken to the stream’s sunlit floor.

On the bank, there lay two knights and a maid,

In the coolness and freshness of the shade.

Canto XIV: 65-67: Meanwhile Agramante prepares an assault on Paris He attacks the guards of the King of Granada’s daughter

Noble Imagination, that prevents me

From merely following a single course,

Now leads me back to the Moorish army,

The French deafened by their cries, the source

That pavilion where King Agramante

Plots to attack the Empire, and in force,

While Rodomonte’s boast doth yet resound:

To burn Paris, level Rome to the ground.

News had reached the ear of Troyano’s son

That the English had already passed the sea;

Garbo’s aged king he now did summon,

With Marsilio, and his goodly company

Of captains, who all counselled him as one,

To launch a grand assault on the city.

Of victory they swore he’d be deprived,

If all were not done ere that aid arrived.

Already, scaling ladders were to hand,

Planks and beams, and hurdles, and whatever

Was needed to execute his command;

Pontoon boats were there, ready to deliver

Bridges o’er the moat and river, all were manned;

And what might serve Agramante better,

The first and second hosts for the assault,

Which he would lead as ever, by default.

Canto XIV: 68-74: Charlemagne’s prayer on the eve of battle

On the eve of that battle, Charlemagne,

Was in Paris to celebrate the Mass,

All the priests, black, white, and grey, in his train,

Who granted absolution, en masse,

To those who’d confessed (and once again

Had been rescued from the infernal pass

To Stygian gloom) lest they should fall,

On the next day, when they must man the wall.

In the church, before his barons and his knights

Midst preachers and princes, his piety

Was displayed, as he assisted in the rites,

Showing an example to the laity,

As with palms joined, face towards the heights

Of heaven, he cried out: ‘O Lord, hear me!

Though my sins are great, in our hour of need,

Let no man suffer for my least misdeed!

Or, if it is thy will that they suffer,

And my sins allow for supplication,

Let the punishment at least be other

Than to die at the foe’s instigation,

For if tis granted them to deliver

To death the friends of your congregation,

These pagans will deem you powerless

To save your people in their last distress.

A hundred then would rebel against you

For every one that may elect to now,

Such that Babel’s chaos would then ensue,

And good Christians to bold pagans bow.

Defend your people, these warriors who

Have cleansed your sepulchre; relief allow

To those who, by your enemies offended,

Have Holy Church, and her priests, defended.

I know our merit is not such that we

Can repay an ounce of the debt we owe;

Nor should we harbour hopes of your mercy,

As regards our sinful lives, here below;

Yet our ills may be healed utterly,

If you your grace upon us will bestow.

Nor indeed can we despair of your aid,

While your pity for us is yet displayed.’

Thus, the pious emperor prayed aloud,

With humble heart, and with deep contrition,

And added other prayers, as he had vowed,

Appropriate to his need, and position;

Nor did his request go un-avowed

For his guiding spirit heard his petition,

Amidst the angels, and spread wide its wings,

And to the Saviour bore his offerings.

A great host of other prayers were borne,

By like messengers, to the skies above,

Such that the blessed throng that there adorn

The choirs of heaven, faces filled with love,

Gazed on the place where Love is ever born,

And, with but one desire, the plea did move,

That He hear the request, so rightly made,

By His Christian people, seeking aid.

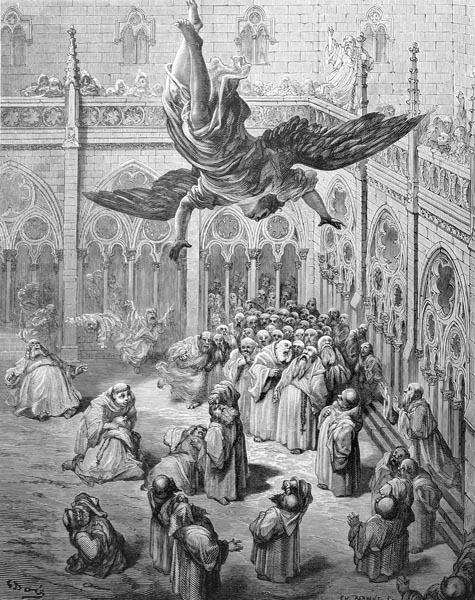

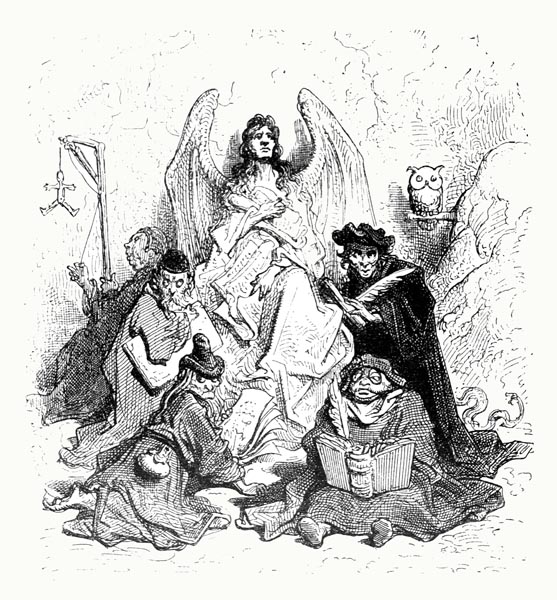

Canto XIV: 75-82: The Archangel Michael seeks out Silence and Discord

The ineffable Good, none seek in vain

That pray with a faithful heart and true,

Raised a merciful eye, and then was fain

To summon the Archangel to his view,

And to Michael said: ‘Go, seek that train

Of men that sailed for Picardy; do you

Then bring them to the walls of Paris, so

That not a sound is heard by their dread foe.

Find Silence first, and then ask him, from me,

To lend his aid to your fair enterprise,

Since he is well equipped, assuredly,

To know what you require, being wise.

Then swiftly go where Discord you may see,

And command that she takes, from her supplies,

Steel and tinder, and then, with fierce intent,

Sets fires, amid the Moors’ whole encampment;

And spreads strife, amongst those who are said

To be their greatest leaders; let them quarrel,

Such that some lie wounded there, others dead,

Others captured, trapped like rats in a barrel,

While some, in disdain, from the camp are fled,

No longer loyal to their king, or useful.’

The Archangel Michael gave no reply,

But, in silence, descended through the sky.

Where’er the Archangel steered his flight,

The dark clouds fled, the heavens were serene;

As bright as lightning flaring in the night,

His golden aureole displayed its sheen.

Meanwhile, he pondered where he should alight,

Since Silence can be neither heard nor seen,

Seeking the enemy of the spoken word,

To whom that first command must be referred.

He gave a deal of thought to the question,

As to where Silence was most wont to dwell,

And recalled that a monk, as if in prison,

Says nothing in the quietness of his cell,

In those orders where speech is not the fashion;

And Silence, where the monks their psalters tell,

Where they sleep and eat, should be present there,

And in every room be written, that they share.

Believing he’d find Silence there, he sped

On his golden wings swiftly through the sky,

Thinking fair Peace to such realms was wed,

And Charity, and Quiet must dwell nearby.

But found he was in error, since, instead,

As soon as he had entered where monks lie,

He found Silence absent, and was told

That twas only in old books such tales did hold.

Nor Love nor Peace appeared there, at all,

Nor Pity, Quiet, nor Humility,

That had dwelt there, as ancient tomes recall,

Now driven forth by Wrath and Gluttony,

By Avarice, Envy, Pride, from out the hall,

And Sloth and Cruelty; amazed was he

At the news, when, gazing at that crew,

Amid the rest, foul Discord he did view;

Whom the Eternal Father had commanded

Him to find, after Silence, not before.

Twas in Avernus, once he had landed

He’d thought to see her, on that evil shore,

Among the damned, yet here she demanded

Her part, midst Mass and prayers what is more,

(Who’d credit it?) Twas all the unkinder,

In that he’d thought twas in Hell he’d find her.

Canto XIV: 83-86: Not finding Silence, he meets with Discord first

He knew her by her multi-coloured dress,

Wrought from a host of unequal fragments

That covered her or not, as the wind’s excess

Revealed or hid all its unsewn segments;

Silver, or gold, or black, or brown each tress

Upon her head, dyed with various pigments;

Some tied with a ribbon, some in a braid,

Or to her shoulders, or her breast, they strayed.

Of summons, and affidavits she’d a store,

And of writs, and letters of attorney,

Of such her hands were full, her breast held more,

Sound counsel, and advice, and commentary,

From which the minds and hearts of the poor

Are never free, in any town, or city.

Before, behind, and all about, attended

Such folk as prosecuted, or defended.

Michael summoned her, and gave his command

That among the Saracens she should go,

Seek the first opportunity on hand

To bring upon them, ruin, war and woe.

Next, as she was like to know, he did demand,

Where Silence lay, for he did often show

Himself here and there, in many a place,

Scattering fire among the foolish and base.

Discord replied: ‘I cannot now recall

Seeing Silence himself hereabout,

But have often heard him mentioned by all

As noted for his shrewdness and, no doubt,

Fraud’s a friend of his on whom you might call,

For she’s accompanied him, in and out,

And, therefore, may have news; now, let me see,’

She pointed with her finger, ‘that is she.’

Canto XIV: 87-90: He enquires of Fraud regarding Silence

With a pleasing face, and modestly dressed,

Eye downcast, and sober manner, I would say,

And of a quiet and friendly tongue possessed,

A Gabriel she seemed, her greeting: ‘Ave!’

Yet foul and deformed throughout the rest

Of her form, hid by a mantle alway;

Long and wide it was, and beneath her cloak

A knife she had, concealed from other folk.

The Archangel asked her by which road

He should travel, if Silence he would find,

‘Near the Virtues’ she said, ‘was his abode,

Nor did he dwell elsewhere, to my mind,

Long ago; beside Benedict he showed,

And in the abbeys, too, with Elias’ kind,

When they were new; and through the schools did pass,

When Pythagoras lived and Archytas,

In ancient days; but those times being gone,

With the saints, and philosophers he knew,

He strayed from the paths he’d walked upon

And from good to evil wandered, sad but true;

He’d spend the night with lovers and, anon,

With thieves, and he sinned with others too,

For, as often, with Treason he would dwell,

And I’ve known him lodge with Murder as well.

With the forgers of false coins, he would seek

Shelter in some safe, half-darkened chamber,

And he’d change his rooms and friends every week,

Meeting with him was a rare adventure,

And yet I’ve hopes, indeed, that you may peek

Upon his present dwelling, at a venture.

If you’ll visit, this night, the House of Sleep,

You’ll find him there, perchance, in slumber deep.’

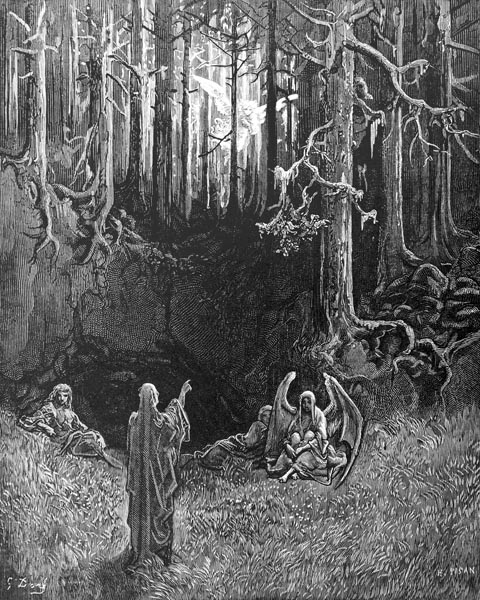

Canto XIV: 91-95: The House of Sleep

Though Fraud was a liar ever, say I,

Her account seemed so credible, that he,

Believing her, at once took to the sky,

Flying, swiftly, from the monastery,

Though tempering his speed such that, thereby,

He’d find himself where he would wish to be,

Where Sleep now dwelt (a place he knew full well)

When Silence would be there: thus, it befell.

In Arabia lies a pleasant valley,

In the shadow of twin hills; in that dale,

Far from any village, town, or city,

Mighty beech-trees, and ancient firs prevail.

The sun shines above, and circles brightly,

But its rays rake the boughs to no avail,

The foliage is far too dense and deep:

And here a cave is found: the House of Sleep.

Beneath the trees this cavern, long and wide,

Runs far into the cliff, and ivy, there,

Wanders o’er the opening, while, inside,

Sleep slumbers heavily, devoid of care.

Ease, gross and corpulent, doth there abide,

On Sleep’s one side and, in that darkened lair,

Sloth too, upon the other, one may meet,

She who can barely stand, or move her feet,

While at the entrance stands Oblivion,

All memory lost, so none may enter,

Nor does she recognise a single one;

She will hear and bear no message ever,

Driving all away; Silence dressed in dun,

Felt shoes, and a long dark cloak, forever

Paces round, on guard, and, from afar,

With a wave of his hand, the way doth bar.

The angel approached and, speaking softly

But quite distinctly, said: ‘God wishes you

To lead Rinaldo, and his company,

To Paris, there to aid the king anew,

And yet ensure all is done silently,

So that the Saracens hear naught, nor view

Their swift approach, and so that he is near,

Ere Rumour comes to whisper in their ear.’

Canto XIV: 96-98: Michael, with Silence’s help, speeds Rinaldo to Paris

Silence granted him no other answer

Than, with a nod, to signal he’d comply,

Then he placed himself behind the other;

And off to Picardy they both did fly.

Michael stirred the host of men and ever

Shortened the road before them, whereby

They came to Paris safely, ere none

Was aware that the miracle was done.

For Silence sped about them, everywhere,

In the vanguard, on the flanks, to the rear,

And spread a covering fog through the air,

Though the sunlight all about them shone clear;

While, through that strange mist, the trumpets’ blare,

Nor the sounding war-horns could any hear.

Then Silence went the pagan camp to find,

And, somehow, rendered all both deaf and blind.

While Rinaldo so hastened, with his men,

That is seemed to him they had an angel guide,

And in such silence that the Saracen

Encampment had heard naught, upon his side,

Agramante had closed on Paris, then

Distributed his forces, far and wide,

About the moat, beneath the city wall,

To launch a broad attack upon them all.

Canto XIV: 99-103: Charlemagne prepares to defend the city

He who would count the troops that Charlemagne

Had gathered, against Agramante’s host,

Might as easily have numbered, though in vain,

All the trees the Apennine forests boast;

Or the waves that race o’er the rolling main,

Down Mauretanian Atlas’ miles of coast;

Or, at midnight, how many watching eyes

Watch the furtive acts of lovers, from the skies.

The tocsin bells now rang to hammer blows

And the sound of their pealing filled the air,

And pleas and vows, from every church, arose,

As hands and lips beseeched the Lord in prayer.

If He prized wealth as much, with all its shows,

As our weak judgement does, so foolishly,

The Consistory would have ruled, that day,

That our statues were to be of gold alway.

The godly old could be heard lamenting

That they had been reserved for such a fate,

Saying the dead in holy ground now lying,

Lost years ago, had known a happier fate.

But the young, their eager spirits burning,

Thought little of dull sorrow at the gate,

Scorning the counsel of their elders now,

As they ran to the walls, with ardent brow.

Here could be seen the baron, and the knight,

King, duke, marquis, count and commoner,

Citizen and stranger, all there to fight,

Ready to die for Christ, and their honour,

Now begging to attack the foe outright,

Crying that the emperor should lower

The drawbridges; their spirit he adored,

But their plea to issue forth, he ignored.

Rather he disposed of them here and there

As was required, to thwart the pagan foe;

Here, content that few men he needs spare,

Yet a company on that side must bestow;

Some were set to hurl flame through the air,

Others to work the catapults; to and fro,

Charlemagne went, looking, unceasingly,

To assist, and their weaknesses foresee.

Canto XIV: 104-108: His state of readiness

Paris is sited on a spacious plain,

At the core of France, the heart rather.

Piercing its wall, then flowing forth again,

The Seine creates islands in the river,

That the city’s noblest part e’er sustain;

The other two, either side the water,

(It’s divided in three parts, I recall)

Are defended by the river, and a wall.

An attack could be made from any side

On those walls that ran for many a mile,

But wishing not to scatter far and wide

His vast host, Agramante, with due guile,

Sought but the one approach, and chose to guide

His troops from the west, as they made trial

Of the defences, for the towns, o’er that plain,

Were all his, and the land as far as Spain.

Within the walls that circled the city,

Charlemagne his vast munitions placed,

Fortifying the embankments strongly,

The counterscarps, within, he encased.

Where the river flowed in and out, there he

Laid great chains across, iron interlaced,

And, above all else, took care to ensure

That all the weakest points were made secure;

With as many eyes as Argus, Pepin’s heir,

Charlemagne, foresaw the line of the attack,

All of Agramante’s plans were laid bare

To his clear mind, nor vision did he lack.

Isoliero, Serpentino were there,

Ferrau too, neath Marsilio; at his back,

Balugante, Grandonio, held the plain,

Falsirone, and the forces brought from Spain.

Sobrin, on the Seine’s left bank, appeared,

With Dardinel d’Almonte, and Pulian,

And, six feet tall and more, the much-feared

Form of the giant monarch of Oran.

But why, my pen, so painfully steered

To tell of these, unstirring, in the van?

For Sarza’s Rodomonte, filled with anger,

Shouted, swore, and would delay no longer.

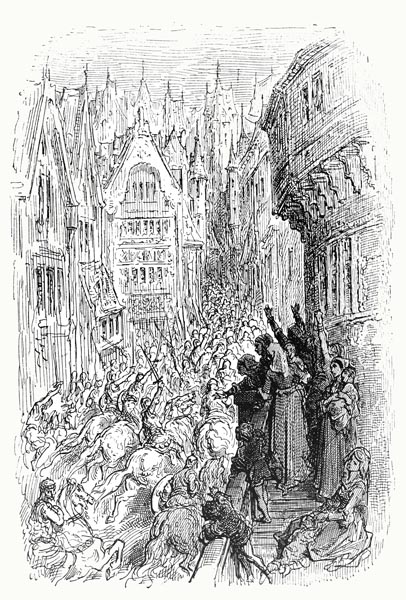

Canto XIV: 109-116: Rodomonte, King of Sarza, initiates the attack

As a host of flies, in the countryside,

Attack our tables, from a summer sky,

(On buzzing wings, in the heat, they ride

Then feed upon the plates that we let lie);

As starlings to the vine-poles, in a tide,

Descend, where now the ripe grapes hang, on high;

So seemed the Moorish army to men’s eyes.

The heavens echoed to their shouts and cries.

On the walls, those of Charlemagne’s army,

With their lances, swords, axes, stones, and fire,

Defended the fair city, fearlessly,

Disdaining the Saracens’ pride and ire;

And when Death snatched a man, randomly,

Another would, swiftly, grasp the briar.

The Moors at the moat, at first, retreated,

By a storm of blades and blows defeated.

Nor was that show of steel alone the cause,

For huge rocks, whole boulders, descended,

Pieces of the battlements gave them pause,

Stones from the very walls, thus defended;

While streams of boiling water struck the Moors,

Fierce deluges, with which none could fight,

Entering helmets, robbing them of sight.

And things far more damaging than steel:

What of that fine mist of lime-dust ever?

What of the pain that burning vessels deal;

Their nitre, pitch, turpentine and sulphur?

What of the heated iron hoops; that reveal

Themselves as wreathes of flame, moreover?

These hurled upon them, by some willing hand,

Form cruel garlands for the foe, as they land.

Now, a second wave, the King of Sarza

Launched, beside Ormida and Buraldo,

(Of men from Garamante and Marmonda)

With them went Soridano and Clarindo.

And there rode Setta’s king, as bold as ever,

And the kings of Cosca and Morocco,

That those around might their great valour know.

Rodomonte’s banner flew o’er the plain,

On its field of vermeil, stood a lion,

Which a bit and bridle did not disdain

To receive from the hands of a maiden;

For, as the savage beast, the king did feign

To depict himself, its jaws wide open;

Doralice was intended by the other,

The King of Granada’s lovely daughter.

She had been borne away, as I related;

(And from which location, and by whom)

She it was whom Rodomonte indicated

On his flag; loving her, you may assume,

More than all his realm; he demonstrated

His skill for her now, the intended groom,

Not knowing Mandricardo had laid claim

To her love, yet he’d still have fought the same.

A thousand ladders were now raised, or more;

Two men, at least, on each, now scaled the wall.

The man behind urged on the man before,

Sometimes a third climbed, seeking not to fall.

Whether brave at heart, or shaken to the core,

All found the strength to climb, and I say all,

For Algier’s fierce king wounded or slew

Any that baulked, and those proved but a few.

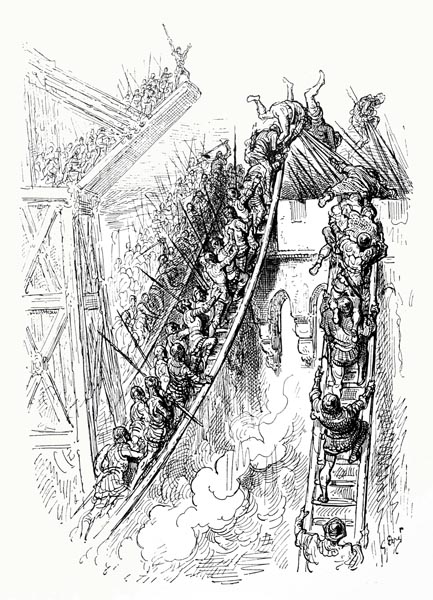

Canto XIV: 117-121: He scales the wall

Thus, amidst the fire and ruin, climbed the foe.

All but Rodomonte took good care

To find the safest route by which to go,

Chancing least danger on the passage there.

Sarza’s monarch scorned such fears to show;

He sought the swiftest journey through the air.

And in that desperate case, while many a Moor

Prayed to his deity, he cursed and swore.

He was clad in good and solid armour,

Like to the scaly hide of a dragon,

The kind once borne by his ancestor

Who built the tower of Babel and, anon,

Sought the governance of the stars to claw

From God Himself, and then see Him gone;

His helm and shield were equally well-made,

Perfected to good purpose, like his blade.

No less than mighty Nimrod, long ago,

He seemed indomitable, wrathful, proud;

A king who’d scale the heavens if, below

His feet, those rungs he felt but allowed;

The furious king had waited not to know

If aught was breached, onwards had he ploughed;

All careless of its depth, ran, flew, the moat,

Though plunged in filthy water to his throat,

Dripping wet, and foul, as yet, with mud,

Midst fire, and stone, and arbalest, and bow,

As through the marshy reeds, scenting blood,

The wild boar of our Malea oft will go,

That with chest, and snout, and tusk, will make good

A passage for himself; he had done so,

This Saracen, that with shield raised on high,

Dared not the wall alone, but braved the sky.

No sooner had the bold king won his way

O’er the wall than on the platform he stood

That within the outer battlements lay,

A wide and roomy bridge, of solid wood;

Here many a skull he shattered on that day,

Shaved tonsures better than a friar could;

Heads flew and arms, a crimson river fell

Streaming from the walls, like that in Hell.

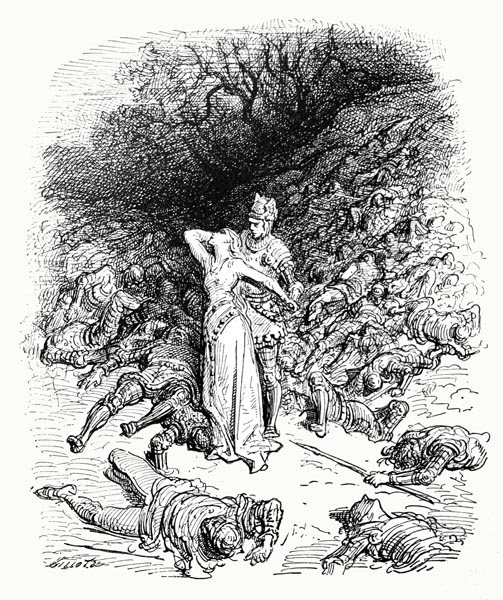

Canto XIV: 122-128: And sets about the Christian defenders

He doffed his shield and, in his two strong hands,

Took his sword, and struck at Duke Arnolfo,

(Who came from where the wide sea commands,

At long last, the mighty Rhine’s broad outflow).

No more than a lump of sulphur withstands

The flame’s touch, the man resisted, to his woe.

This Duke gave a shudder and slumped down,

Cleft to the neck, from high upon the crown.

At a stroke Spineloccio he slew,

With Anselmo, Prando and Oldrado,

For many had filled up the space anew,

Therefore, many fell to that sweeping blow.

Half of them were Flemings, not a few

Were Normans, whom he swiftly sent below;

Orghetto, the Manganese, fell there,

Cleft to his belly, where he held the stair.

He hurled down Andropono and Moschino,

Into the moat below, the first a priest,

The second loved his wine and, at one go,

Could drain a flagon and a half at least.

He treated water like the poisoned flow

Of venom from a viper; now, released

To the ditch beneath, amidst the slaughter,

What dismayed him most was death by water.

Then Louis of Provence was cleft in two;

Arnoldo of Toulouse pierced through the chest;

Hubert of Tours and brave Claudio too,

Dionigi, Hugo, slain among the rest;

Odo, Ambaldo, Satallone, who

With Walter were of Paris, and the best

Of men; to many, there, did death befall,

Whose name and country I can scarce recall.

The foe, behind those led by Rodomonte,

Raised many a ladder, and scaled the wall.

The Parisians made some little headway,

Though, in their first reply, a host did fall.

And still their enemies must forge a way,

Past further snares, designed to trap them all,

For between the wall, and the inner bank,

A fearful moat descended, deep and dank.

Add again that our defenders, below,

Fighting the Saracens, showed great valour.

New men succeeded, sent to stem the flow,

Those who had fallen, true men of honour,

And with long lances, and many an arrow,

Strong challenge to those climbing did offer,

Though many, in the end, might have run

Had it not been for King Ulieno’s son.

He encouraged some, and rebuked the rest,

And drove them forward, for good or ill;

And here a head he cleft, and there a breast,

Midst the enemy, and those he could not kill

He pushed, and herded backwards, as they pressed,

Grappling with heads, necks, and arms at will;

And hurled so many outwards, from above,

Those in the moat below him scarce could move.

Canto XIV: 129-134: Many Saracens are destroyed at the inner moat

Meanwhile a host of barbarians descended,

Or rather leapt into the second moat within,

And then by many a means they ascended,

The summit of the inner bank to win.

Rodomonte (as if on wings suspended)

Despite the great bulk which did underpin

His mighty strength, and weight of armour,

Leapt clean across the ditch, in his ardour,

(Its width no less than twenty feet, or so)

Swift as a greyhound, eager to compete;

Making as little noise in landing, though,

As a man would with felt bound round his feet;

And then at coats of armour he did hew,

As if of pewter wrought, and not of sheet

On sheet of steel, or soft as willow rind,

Such was his sword and strength, as all did find.

Ere this time arrived, our forces had laid

An insidious trap in the moat below,

Where cut broom, and thick branches, overlaid

Cartloads of pitch, yet all well-hidden though,

For all was sunk below, and heavily weighed,

All that dense covering, so naught did show.

This depth of matter ran from bank to bank,

And, in the water, many a cask they sank,

Charged with saltpetre, or oil, or sulphur,

Or with some other flammable substance.

Our men (intent on bringing ruin, ever,

Upon the Moors and thwarting their advance

Beyond the ditch, which, crammed together,

They thought to leave) our men of France,

And elsewhere, hearing the signal, set fire

To the ditch, lighting one great funeral pyre.

For the many scattered flames soon united,

And set the moat ablaze, from side to side,

So high that the moon they’d have blighted,

Even her watery bosom they’d have dried;

While a vast dark cloud left all unsighted,

Hiding the sun, and spreading far and wide,

As, from the pit, a mighty roaring sound,

Like endless peals of thunder, shook the ground.

A dreadful concert rose, in harmony,

Of shrieks of pain, of bitter shouts and cries,

(From those lost ranks, in their last misery,

Who perished, led to death in such a guise,

By their fierce king) according, seemingly,

With that mighty flame, that on high did rise.

No more, no more, of this sobering canto!

For I am hoarse, and needs must rest, also.

The End of Canto XIV of ‘Orlando Furioso’