Heinrich Heine

Germany: A Winter’s Tale (Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen, 1844)

Part II: Chapters VIII-XVII

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter VIII: Westphalia: Mülheim.

- Chapter IX: Hagen.

- Chapter X: Unna.

- Chapter XI: The Teutoberg Forest.

- Chapter XII: The Teutoberg Forest - Continued.

- Chapter XIII: Paderborn.

- Chapter XIV: Barbarossa.

- Chapter XV: Barbarossa – Continued.

- Chapter XVI: Barbarossa – Continued.

- Chapter XVII: Barbarossa – Concluded.

Chapter VIII: Westphalia: Mülheim

The cost from Cologne to Hagen, by coach,

Is five Prussian thalers, six groschen,

Unfortunately, the coach was full,

So, I rode in a chaise, in the open.

A late autumn morning, damp and grey;

The carriage ploughed through the mud,

But despite the road and the weather,

I felt sweetly content, neath the hood.

I breathed the air of my homeland!

I felt my cheeks were burning!

And the dirt of that country road,

Twas my fatherland I was churning!

The horses swished their tails

As warmly as old friends do,

And their dung seemed as beautiful

As the apples Hippomenes threw!

We drove through Mühlheim, a pretty place,

The people work hard, each one.

I was last there in the month of May

In eighteen thirty-one.

‘Ice floe in Mülheim on the Rhine (1784)’ - H. Goblé

The Rijksmuseum

Back then, all was decked with flowers,

And the sun was smiling on high,

The birds sang out their longing,

And people thought, with a sigh:

‘These lanky knights, these noblemen,

Will soon be gone from here,

We’ll serve them all a farewell draught,

From our steel barrels, and cheer!

Freedom means games and dancing,

And the tricolour, red, white and blue,

And perhaps it will raise, from the grave

The ten-years-dead Bonaparte too!’

Dear God! The knights are still here,

And many a goose we see

That was lean on its arrival,

Is as fat as ever could be!

Those pale rascals who talked

Of love, faith, hope, at the time,

Have rendered their noses red,

Drinking the best of Mülheim,

While Freedom has sprained her ankle,

And no longer leaps about madly,

And, in Paris, the tricolour

Looks down from the turrets, sadly.

Their emperor rose once more,

But the English worms, his bane,

They rendered the great man silent,

By burying him again.

I myself saw his funeral,

Saw the gilded carriage go by,

With its goddesses of victory,

Bearing the coffin on high.

Along the Champs Élysées,

Midst the fog, o’er the snow,

Through the Arc de Triomphe,

I watched the procession go,

The music eerie, discordant,

The musicians frozen with cold,

The eagles on the standards,

That greeted me, wistfully old.

The people looked like ghosts,

Lost in their memories; all in vain,

The imperial fairytale, the dream

Was conjured to life again.

I wept that day. I felt the tears

Rising to my eyes,

On hearing ‘Vive l’Empereur!’,

Those lost ones loving cries.

Chapter IX: Hagen

I left Cologne at a quarter to eight,

Quite early, the weather was fine,

And arrived in Hagen at about three,

Where we sat down to dine.

The table was set. There I found

The true Germanic cuisine.

‘Greetings to you, dear Sauerkraut;

Fragrant one, how have you been?’

Braised chestnuts on green cabbage,

Just as she did them, my mother!

Greeting to you too, native Cod,

Skilfully swimming in butter!

The fatherland is eternally dear

To every heart that can feel –

I also love poached eggs, and kippers

Braised quite brown, for a meal.

How the sizzling sausages squeaked!

While the fieldfares, roasted angelically,

And served with apple sauce,

Chirped their ‘Welcome!’ to me.

‘Welcome, countryman,’ they chirped,

‘You’ve been away too long,

Flitting about with strange birds,

In foreign lands too; it’s wrong.’

There was a goose on the table,

Who’d loved me perhaps, when young,

That quiet, gentle creature,

Whom many a poet has sung.

She looked at me, with meaning,

So deeply, truly, woefully!

Surely her soul was beautiful,

Though her flesh seemed tough to me.

They also offered a pig’s head

Served on a pewter plate;

We still adorn a pig’s snout

With bay leaves, and its pate.

Chapter X: Unna

Beyond Hagen, it was night.

I was strangely chilled within,

And only grew warm again,

On reaching Unna, at the inn.

There I found a pretty girl,

Who served a glass of punch outright,

Her hair shone like yellow silk,

Gentle her eyes as moonlight.

I heard once more with pleasure

The Westphalian accent, too.

The punch steamed, sweet memories,

I thought of my ‘brothers’ anew,

Those many fine Westphalians

Whom I drank with in Göttingen,

Until our very hearts were moved,

And beneath the table I sank again!

Those dear, good Westphalians;

I’ve always loved them so,

So steadfast, and sure, and true,

And modest, though sometimes slow.

How nobly they stood to fence,

Those lion-hearts, I found!

With tierce and quarte, in defence,

How well they held their ground.

They drink well, they fight well,

And offering you their hand,

From pure friendship, they will weep;

Like mighty oaks they stand.

May Heaven, then, defend the brave,

And bless your harvests all,

Protecting you from glory, war,

And heroes, lest you fall;

And grant that you see your sons

Pass their exams, like honest men,

Find suitors for your daughters,

And marry them off – Amen!

Chapter XI: The Teutoberg Forest

Here’s the Teutoberg Forest

Which Tacitus, no liar,

Described, where Varus came to grief,

Stuck in the classic mire.

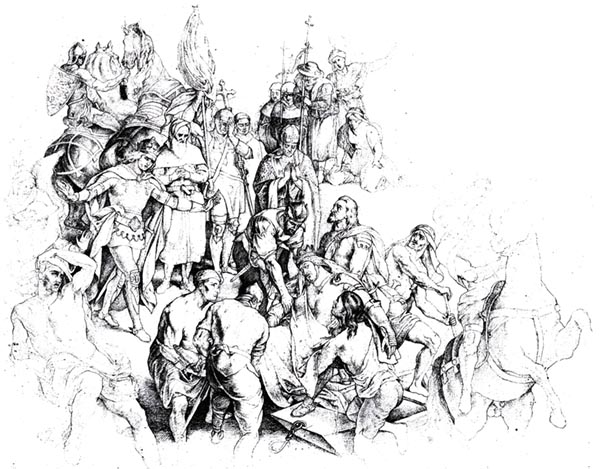

‘Furor Teutonicus" - Battle of the Teutoburg Forest’ - Paja Jovanović (Serbian, 1859-1957)

Wikimedia Commons

Here the Cheruscan prince,

Arminius, brought him low;

The Germanic race, and Hermann,

In the mud there, dealt a blow.

If he had failed to win the fight,

There’d be no German freedom;

Were it not for his blonde horde,

Our land would yet be Roman.

And, in our fatherland, today,

Rome’s customs would prevail,

Vestal Virgins dwell in Munich,

Swabian ‘Quirites’ quaff their ale.

And Hengstenberg, as a haruspex,

Would be deep in the entrails,

And Neander would be an augur,

Watching the flight of quails.

Birch-Pfeiffer would drink turpentine

As Roman ladies used to do.

(It’s said it made their urine

Smell sweeter – if it’s true.)

Raumer would be a Roman rogue

Not one in the German fold,

And Freiligrath’s poems would fail to rhyme,

Like Horace’s of old.

That rude boorish, Father Jahn,

Would, in Latin, be Boorianus.

By Hercules! Massman would be

Marcus Tullius Massmanus!

The friends of truth would be wrestling

Lions, jackals and hyenas,

Not curs in lesser journals,

As in our modern arenas.

And we would have one Nero, and not

Three dozen Fathers of the Nation.

And be slicing at our veins,

Scorning slavery’s prostration.

Schelling would be our Seneca,

And perish the same way;

‘Cacatum non est pictum,’

To Cornelius, we’d say.

Thank God, that Hermann won the fight,

And so drove out the Romans!

Varus and his legions fell,

And we are still the Germans!

Germans we are, German we speak,

As we spoke it, and ever will.

An ass is an ass, not an asinus,

Swabians are Swabians still.

Raumer remains a German rogue

In our northern Germany;

Freiligrath, whose poems rhyme,

Was never a Horace to be.

Massman speaks no Latin, thank God!

Birch-Pfieffer simply writes plays,

And never drinks vile turpentine,

As they did in ancient days.

O Hermann, we have you to thank!

Thus, they’ve raised, and inscribed,

A monument, near Detmold, to you.

Indeed, I myself subscribed.

Notes: The silver groschen equal to twelve pfennigs was worth a thirtieth of a silver thaler, (the thaler was equivalent to an English crown, therefore the groschen was equivalent to two pence). In the Greek myth Atalanta was thwarted in a footrace by her suitor Hippomenes, who threw three golden apples in turn to divert her attention. Varus, the Roman general, famously committed suicide after the defeat of his three legions by Arminius (Hermann) at the Battle of the Teutoberg Forest in 9AD. Quirites were citizens of Rome. A haruspex interpreted omens by inspecting animal entrails, an augur by examining the flight of birds. Joachim Neander (1650-1680) was a Calvinist teacher, theologian and hymnwriter. Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer (1800-1868) was an actress, writer, director of the Stadttheater in Zürich, and the author of many plays and librettos. Friedrich von Raumer (1781-1873) was a historian who popularised the writing of history in German. Ferdinand Freiligrath (1810-1876) was a poet, translator and liberal agitator. Friedrich Ludwig Jahn (1778-1852), a gymnastics educator and nationalist, gained the epithet ‘The Father of Gymnastics’. Hans Massmann (1797-1874) was a philologist, also known for his work introducing gymnastics to Prussian schools. Friedrich Schelling (1775-1854), was an idealist philosopher. Peter von Cornelius (1783-1867), was a painter belonging to the Nazarene movement. ‘Cacatum non est pictum’ means ‘shit should not be painted.’ The memorial to Hermann, the ‘Hermannsdenkmal’ is located southwest of Detmold, on a hill in the Teutoburger Wald.

Chapter XII: The Teutoberg Forest - Continued

Through the dark forest rumbled

The chaise. We crashed in an instant,

A wheel had come adrift; we halted,

Our state was less than pleasant.

The postilion leapt to the ground,

To the village, swiftly hastening;

Alone, in the forest, at midnight,

Around me rose a howling,

The wolves were calling, loudly.

Their hunger was most dire;

Like lamps in the darkness

Their eyes were full of fire.

They had heard of our coming,

The pack showed honour to us,

By kindling the forest,

And howling out in chorus.

Twas a serenade, I realised;

It was myself they celebrated.

So, instantly, I struck a pose,

An oration was indicated:

‘Fellow wolves, I’m most pleased

To be here with you this eve,

With so many noble souls

Howling their love, I believe.

What I feel at this moment is

Profound, and quite immeasurable,

This hour, in its beauty, will prove

I know, wholly unforgettable.

I thank you for your trust in me,

Which is greatly to your honour,

And of which, in times of trial,

The clearest proof you offer.

Fellow wolves, you’ve never doubted me,

You were ever undeceived

By the slanderers who said I’d gone

To the dogs, which you ne’er believed;

Nor that I, a renegade, midst the sheep

A councillor soon would be.

To contradict their lies was quite

Beneath my dignity.

The sheepskin that, for warmth,

That, occasionally, I’ve worn,

Trust me, has never made me,

One of the sheep I scorn.

Neither a sheep, nor a hound am I,

Nor a councillor, nor a dogfish,

I’ve ever remained a wolf at heart,

And my teeth are still as wolfish.

I am a wolf, and will always howl

With the wolves, when midnight’s due.

So, count on me, and help yourselves,

Then God will help you too!’

That was the speech I gave them,

On every last word, they hung.

Kolb has printed it, mutilated

In the ‘Allgemeine Zeitung.’

Note: The ‘Allgemeine Zeitung’ (‘Public Newspaper’) founded in 1798, was the leading political daily journal in Germany in the first part of the 19th century. Heine was a major contributor, and from 1831 reported on music and art, becoming its Paris correspondent. Gustav Eduard Kolb (1798-1865) was its editor from 1828 onwards, often publishing in defiance of the censors.

Chapter XIII: Paderborn

The Sun arose, at Paderborn,

With a gloomy expression.

Lighting the stupid Earth

Is indeed a gloomy mission!

When, in the planet’s course,

One side has seen the light,

The sun shines on the other,

The first plunges into night.

The Danaid’s jars are never filled;

The stone rolls down again

Once Sisyphus has reached the top;

The Sun lights Earth in vain.

And as the morning mist dissolved,

And cleared from the wayside,

I saw the image of a man,

Of the one who was crucified.

I’m filled with sadness, every time

I behold you, my poor cousin,

A fool who sought to save the world,

And Humanity therein!

They played a nasty trick on you,

Those members of the Sanhedrin.

What possessed you to speak recklessly,

Of the state, religion, and sin!

Sadly, for you, the printing press

Was absent in those days.

You might have issued a book

Explaining God’s celestial ways.

The censor would have expunged

Whatever he deemed no loss,

And thereby saved you, kindly,

From dying on the Cross.

If only you’d chosen another text

For your Sermon on the Mount,

You’d enough wit and talent

To have made mere piety count!

But you drove the money-changers

From the Temple, and with zest –

Unhappy extremist, now you hang

On the Cross, to warn the rest!

Notes: In Greek myth, the Danaids (the ‘daughters of Danaos’) were punished for killing their husbands by being forced to endlessly fill their leaking jars with water. Sisyphus revealed Zeus’ abduction of Aegina to the river god Asopus, thereby incurring Zeus’ wrath. After death. his eternal punishment was to roll an immense boulder up a hill, only for it to roll back down again, each time it neared the summit.

Chapter XIV: Barbarossa

A damp breeze, a bare landscape,

The chaise, the mud the same,

While in my soul a voice was singing,

‘Oh, Sun, your mournful flame!’

Twas the last line of an old song,

One my nurse sang many a day;

‘Oh, Sun, your mournful flame!’,

Like a hunting-horn, far away,

The tale had a murderer in it,

Who lived most pleasurably,

Yet was found hanging in the woods,

From a grey willow tree.

The Feme Court’s sentence was nailed

To the trunk of the tree, below,

‘Oh, Sun, your mournful flame!’

Vengeance was taken so.

The Sun had accused, and caused, him,

To be condemned to death.

‘Oh, Sun, your mournful flame!’

His victim cried, with her last breath.

And whenever I think of the song

I think of my dear old nurse,

I see her weathered face again,

All wrinkles, and folds, and worse.

She had been born in Münsterland

And knew how to regale

The listener with some ghost-story,

Folk song, or fairy-tale.

How my heart beat when she told

Of that princess, young and fair,

Who sat alone, by the hearth,

Combing her golden hair.

She had to look after the geese,

As a goose-girl, and when she

Drove the geese to the yard at eve,

She stood gazing, sorrowfully,

For nailed over the gateway,

There hung a horse’s head,

That of the unfortunate steed,

Who to exile, with her, had sped.

The princess sighed deeply:

‘O Falada, that you hang so!’

And the horse’s head replied:

‘Oh, that you must live in woe!’

The princess sighed deeply:

‘Oh, if my mother knew!’

And the horse’s head replied:

‘Her heart would break in two!’

With bated breath I listened

As her voice she lowered once more;

And spoke of Barbarossa,

Our secret emperor.

She swore he wasn’t dead

As the scholars claimed, one and all,

But, with his comrades-in-arms,

Still lived, in a cavernous hall.

‘The discovery of the body of Emperor Frederick Barbarossa in the Kalykadnus River (c. 1828-1834)’ - Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld (German, 1794 - 1872)

Artvee

Neath a mountain, named Kyffhäuser,

Is the cave, where he lives in state,

In a ghostly high-vaulted hall

That bright lamps illuminate.

The first of four great chambers,

Holds a stable, where many a steed,

In full harness, beside its manger,

Stands, awaiting some epic deed.

All are saddled and bridled

And yet not a single steed

Neighs or stamps, all are silent,

As if cast in iron, indeed.

In the second chamber, on straw,

Thousands of soldiers are lying,

Bearded, with warlike features

For none are afraid of dying.

They’re armed from head to toe,

But no watch those brave men keep;

They neither wake, nor move,

Merely lie there, deep in sleep.

In the third chamber stacked high,

Are weapons, as if under seal,

Swords, axes, Frankish firearms, armour,

Spears and helms, of silver and steel;

And a few cannon, sufficient to form

A triumphant pile; overhead,

A banner is raised, its colours

Are black, and gold, and red.

In the fourth hall, sits the emperor,

As he has for centuries,

On a stone chair, at a stone table,

His head on his arms, at ease.

His beard, which touches the ground,

Is as red as a glowing fire,

And now he blinks his eyes,

And now he frowns with ire.

I he asleep, or thinking?

It’s impossible to say,

But he’ll shake himself and rise

On the appointed day.

For, then he’ll seize his banner,

‘To horse, to horse!’ he’ll call,

His mighty host will awake

And rise noisily, one and all;

Then mount their snorting steeds,

And behind his banner, unfurled,

As the trumpets raise their cry,

They’ll ride forth into the world.

He rides well, he’ll fight well,

He’s slept well, in short.

Now, to punish the murderers,

He’ll hold his imperial court.

Those murderers who slew

The precious, the wondrous dame,

The golden-haired maid, Germania –

‘Oh, Sun, your mournful flame!’

Many a lord in his castle, thinking:

‘I’m secure against loss, sir!’

Will not escape the hangman’s rope –

Nor the wrath of Barbarossa!

How lovely and sweet they sound

The tales, of those heroes known to fame,

Bringing joy to my superstitious heart,

‘Oh, Sun, your mournful flame!’

Notes: The medieval German ‘Feme’ Courts, for example those in Westphalia, had the power to issue death sentences. Frederick Barbarossa (1122-1190), also known as Frederick I was the Holy Roman Emperor from 1155 until his death. His coat of arms was a black eagle, with red beak and claws, on a field of gold. Legend claims him to be asleep, with his knights, in a cave in the Kyffhäuser mountains in Thuringia, and that when the ravens cease to fly around the mountain, he will awake and restore Germany to its ancient greatness.

Chapter XV: Barbarossa – Continued

A fine rain drizzled down,

Ice-cold, like a needle’s tip;

The horses swished their tails, sadly,

And shivered at every drip.

The postilion sounded his horn

Summoning the ancient tune:

‘Three riders are riding forth from the gate!’

I felt languid, as if in a swoon.

I finally fell asleep, and dreamed,

And behold, there was I,

With the emperor Barbarossa,

Neath that mountain, broad and high,

He no longer sat in his chair of stone,

A stone statue, at a stone table,

Nor did he look quite as venerable

As one imagines, if one’s able.

He waddled about the four halls,

Holding intimate conversation,

Showing me, like an antiquarian,

The past treasures of the nation.

In the hall of weapons, he demonstrated

How a club should be employed,

And with his ermine rubbed the rust

From a sword with which he toyed.

With a peacock’s feather in hand,

From many a suit of armour,

And many a helm, he cleaned the dust,

And from many a Pickelhaube.

He dusted off the banner too,

And said: ‘It fills me with pride,

That moths have never eaten the silk,

While woodworm, the shaft’s defied.’

And when we came to the hall,

Where the warriors slept, on the ground,

In those many thousands, waiting for war,

Great pleasure, the old man found:

‘Walk quietly, and speak low,’ he said,

Or you’ll waken them, I’m afraid.

A hundred years have passed,

And today is the day they’re paid.’

And, behold, he approached, softly,

And secretly placed a ducat,

Owed to every warrior there,

Into the man’s deep pocket.

He said, with a smile on his face,

As I stared at him: ‘You see,

I pay a good wage to every man,

A ducat per century.’

In the first hall where the steeds,

Stand in long rows, in silence,

The emperor rubbed his hands,

Strangely pleased by their presence.

He counted them, one by one,

He patted their flanks, and then,

His lips moving anxiously,

As he counted them all again.

‘The number’s not complete,’ he said,

With a frown, when he was done,

‘I’ve weapons and warriors enough,

But of steeds lack many a one.

I’ve sent men all over the world,

To buy the best steeds for me,

And already have quite a few,

Of the finest, as you can see.

I’ll wait till the number’s complete,

Then I’ll strike, and freedom I’ll win

For my Fatherland, and my people

Who trust that, one day, I’ll begin.’

So, spoke the emperor, but I cried:

‘Strike, then, old fellow, strike now,

And if you lack a few horses,

There are asses enough, I vow!’

Old Redbeard, replied, with a smile:

‘Come, Rome wasn’t built in a day,

Good things take time to develop,

Folk can cope with a little delay.

If it can’t be today, then tomorrow;

Great oaks grow slowly, as well;

Chi va piano, va sano,

They say, where the Romans dwell.’

Note: ‘Chi va piano, va sano’, is an Italian phrase, meaning ‘Those who go slowly, go safely.’

Chapter XVI: Barbarossa – Continued

A jolt of the carriage awoke me,

But my eyelids soon closed, and then,

I fell asleep, and I dreamed

Of Barbarossa again.

I chatted with him, once more,

As we circled the echoing hall,

He asked about this and that,

Demanding I tell him all:

‘I’ve not had a word from outside,

For many and many a year,

Not since the Seven Years War

Has anyone new been here.’

He asked about Moses Mendelssohn,

And ‘Die Karschin’ no less,

And asked after the Countess Dubarry,

Who was Louis XV’s mistress.

‘O emperor’, I cried, ‘how dated you are,

That Moses died long ago,

As did Abraham and Rebecca,

And their son’s with the worms below.

There’s an Abraham who with Lea

Had a boy named Felix, who later

Made great progress in Christianity,

And is now a fine choirmaster.

Old Anna Karsch, too, is dead,

And Caroline von Klencke, her daughter,

Though Helmina von Chézy’s alive, I think

Who is ‘Die Karschin’s grand-daughter.

While Louis XV reigned,

Madame Dubarry was on the scene,

And she was already old

When she went to the guillotine.

Louis XV, he died peacefully

In his bed, but who can forget

That the sixteenth was guillotined,

With Queen Marie Antoinette?

The latter showed great courage,

As was fitting for a queen,

But Dubarry wept and howled,

As she went to the guillotine.’

‘Jeanne Bécu, Countess Du Barry’ - Jean Baptiste André Gautier d'Agoty

Raw Pixel

The emperor halted, suddenly,

Gazed at me with his staring eyes,

‘What, in God’s name, is this guillotine?

He asked, showing some surprise.

‘The guillotine’, I explained to him,

‘Is a new method devised, alas,

To hasten folk from life to death,

Fit for people of every class.

Proposed by Monsieur Guillotin,

The method employs a new machine,

Which is why the thing is named

After its sponsor, the guillotine.

You’re strapped to a board, like so.

It lowers; you’re strapped in tight;

There’s a slanted blade, you’re below;

One can struggle, with all one’s might,

But they pull a rope, the blade descends,

To vast merriment, and cheers,

And your head falls into a sack,

Full of a number of your peers.’

The emperor interrupted me:

‘Silence! Who wants to know?

God forbid I should use it,

Or deal any head such a blow!

A king and queen indeed,

Strapped to a board thus set,

It shows a lack of respect,

And flouts the rules of etiquette!

And who are you, that dare,

To address me familiarly,

Just wait, you cheeky rascal

And I’ll clip your wings; you’ll see!

It stirs my bile, the manner

In which you speak to me,

Your every word is high treason,

A crime against majesty!’

The old fellow was so enraged,

And sneered so, no longer quaint,

That my most secret thoughts,

Burst forth, without restraint:

‘Herr Redbeard,’ I cried, ‘you are

A merely mythical old creature,

Go back to sleep, we’ll save ourselves,

Without your needing to feature.

The Republicans simply laugh

When they see that we have, as leader,

As if in some form of bad joke,

A ghost with a crown and sceptre.

Nor do I like your banner, the fools

In my old fraternity

Spoiled my enthusiasm,

For red, gold, and black, you see.

It’s best if you stay at home,

In the old Kyffhäuser, here.

On reflection, we’ve no need

Of an emperor, that’s clear.’

Notes: Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786) was a German-Jewish philosopher and theologian, whose writings on Jewish religion and identity were central to the Haskalah, the ‘Jewish Enlightenment’ of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Anna Louisa Karsch (1722-1791) was an autodidact and poet from Silesia, known to her contemporaries as ‘Die Karschin’ and ‘the German Sappho’. Jeanne Bécu, Comtesse du Barry (1744-1793) was the last ‘maîtresse-en-titre’ of Louis XV of France. She was guillotined during the French Revolution. ‘Felix’, is Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847), the composer, the son of Abraham Mendelssohn and Lea Salomon. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin (1738-1814) a French physician, politician, and freemason, proposed in 1789 the use of the device, known by his name but invented by Antoine Louis, as a less painful method of execution.

Chapter XVII: Barbarossa – Concluded

I was forthright with the emperor;

In dream, of course, in dream –

When one’s awake, with princes

One’s approach is less extreme.

A German only dares to give

In idealistic dreams,

The true opinions he holds

About reality, it seems.

Awake, passing by the forest,

Seeing all those ranks of trees,

In bare, wooden actuality,

My dream fled with the breeze.

Oak-trees shook their branches gravely,

Birches bowed, and furthermore,

Waved a warning: ‘Oh,’ I cried,

‘Forgive me, my dear emperor!

Forgive my speaking hastily,

Indee, you’re wiser far than I,

Who have but little patience;

Yet, come now, not by and by!

And if the guillotine’s not fitting,

Let the ancient means suffice,

The sword for the noblemen,

The rope, though less precise,

For the peasants, and at times,

Let the lords hang and behead

The citizens, and the masses;

We’re God’s creatures, live or dead.

Restore that court of justice,

Charles the Fifth’s audiencia;

Sort all by class, guild, and trade,

And divide the people more.

Give us back again, complete,

Your Holy Roman Empire, all

Its ancient mouldy rubbish;

All its frills and furs, recall.

For, in fact, the Middle Ages,

In their true reality,

I could endure, but save us

From this hybrid mockery,

This Order of the Garter,

A disgusting mix, most foul,

Of the Gothic and the modern,

That is neither fish nor fowl.

Chase away the pack of clowns,

Close the theatres, all this lie

That merely parodies the past;

Yet come now, not by and by!

End of Part II of Heinrich Heine’s ‘Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen’