Heinrich Heine

Germany: A Winter’s Tale (Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen, 1844)

Part I: Chapters I-VII

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2026 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen.

- Chapter I: The Franco-German Border.

- Chapter II: The Franco-German Border – Continued.

- Chapter III: Aachen.

- Chapter IV: Cologne.

- Chapter V: Cologne – Continued.

- Chapter VI: Cologne – Continued.

- Chapter VII: Cologne – Concluded.

Translator’s Introduction

‘Portrait of Heinrich Heine’ - Adolf Neumann (German, 1825-1884)

The Rijksmuseum

Christian Johann Heinrich Heine; born Harry Heine (1797 –1856) was a leading poet, author, and literary critic, of the German Romantic Movement. Known for his early lyric poems, frequently set to music in the form of Lieder by composers such as Schumann and Schubert, his later verse and prose were notable for their satirical wit and irony. Regarded as a member of the ‘Young Germany’ movement, his radical political views led to the banning of many of his works, and he spent the last twenty-five years of his life in Paris.

‘Germany: A Winter’s Tale’ (Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen, 1844) his satirical verse ‘epic’ describes a journey from Paris to Hamburg in the winter of 1843. The title ‘A Winter’s Tale’ refers to Shakespeare’s late play, and the work forms a counterpart to Heine’s earlier verse epic ‘Atta Troll: A Midsummer Night’s Dream’.

Heine had emigrated to France, in 1831, due to the political conditions in Germany during the post-Napoleonic German Restoration period and, in 1835, his works were banned with those of the other poets of ‘Young Germany’. On the return journey from a brief visit to Germany in 1843, he wrote the first draft of ‘Germany: A Winter’s Tale,’ later turning it into a satirical travel epic with political overtones. In October 1844, the book was banned in Prussia, while, in December, a royal arrest warrant was issued against Heine. Subsequently, the work was repeatedly banned by the censor. Though available in other parts of Germany in a separate edition, Heine was forced to shorten and rewrite it.

This enhanced edition has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, and the titles given to works of art, have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen

Chapter I: The Franco-German Border

In the sad month of November, it was,

The days were growing darker,

The wind was tearing the leaves from the trees,

When, to Germany, I crossed over.

And as I approached the border,

I felt my heart pounding harder,

Deep in my chest; I even think

My eyes had begun to water.

And when I heard German spoken,

I felt something strange inside,

As if my heart was bleeding,

Or, most pleasantly, liquified.

A maid, to a harp, was singing,

She sang with feeling; it’s true,

In a high-pitched voice, but her playing

Moved me most deeply, anew.

She sang of love and heartache,

Of sacrifice, and renewal,

Up there, in a better world,

Where none suffer, and none are cruel.

She sang of our earthly vale of tears,

Of pleasures enjoyed in vain,

Of the afterlife, where souls in bliss,

Transfiguration, attain.

She sang of renunciation,

Of a heaven, above the steeple,

With which they lull it, when it moans,

That rascally thing, the People.

I know the tune, I know the text,

I also know the authors,

I know, in secret, they drank wine,

In public, drank the waters.

A new song, and a better song,

My friends, I’ll pen for you!

The kingdom of heaven we’ll have

On Earth; it’s overdue.

It’s here we want to be happy,

And suffer pain no more.

Idle mouths shall not consume

What busy hands ensure:

Enough bread for everyone,

To feed all humankind,

Roses, myrtle, beauty, joy,

And sugar-snaps spring to mind.

Yes, sugar-snaps for everyone,

As soon as the pods are ripe!

Leave heaven to the angels,

‘And the sparrows’, they pipe.

And if we grow wings when we die,

We’ll come and visit you,

Up there, above, and eat a cake,

And a blissful pie or two.

A new song, and a better song,

Set for flutes and violins!

Misery and woe are over,

Death is ended, life begins.

Europa, the maiden, is betrothed

To freedom; O joy and bliss,

They lie close, in each other’s arms,

And revel in their first kiss.

And though a priest is lacking,

The marriage is valid no less –

Long live the bride and groom,

And the children they will bless!

An epithalamion is my song,

Of a new, a purer gestation.

In my soul, the stars ascend,

Of a nobler consecration.

Ardent stars, they wildly blaze

Melting to streams of fire –

I feel a wondrous strength,

I could shatter oaks entire!

Now I’m here on German soil,

A magic elixir fills my veins –

The giant touches mother earth,

And his powers he regains.

Chapter II: The Franco-German Border – Continued

While the little girl, from heavenly joy,

Trilled and harped away,

The Prussian Customs officers

With my luggage made hay.

They sniffed around, and rummaged about,

Exchanging doubtful looks,

Searching for lace or jewellery,

Or even – forbidden books.

Fools, searching through my suitcase,

Go look elsewhere, instead!

The contraband I’m carrying

Is here, inside my head,

Where I’ve lace and pins finer

Than in Brussels or Mechelen,

I’ll unpack my pins later,

And prick and tease you, then.

In my brain I bear Crown jewels,

Gems of the future scene,

The new god’s temple jewels,

The unknown god’s, I mean.

And there I carry many a book,

More than I bear in hand,

My head’s a nest, atwitter,

With books that have been banned.

Trust me, there are none worse

In any library known to Satan,

More dangerous than any penned

By Hoffmann von Fallersleben! –

A traveller, standing by my side,

Remarked to me, that I

Had the Prussian Customs Union,

In full glory, before my eye.

‘The Customs Union’ he remarked,

‘Will establish our great nation,

Join the fragmented fatherland,

In a single administration.

It will grant us external unity,

A material whole, so-called,

And censorship, a single will;

That’s the true ideal of all –

It will grant us inner unity

Linking sense and thought.

We need a united Germany,

Inside and out, in short.’

Note: The poet August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben (1798-1874), is best known for writing ‘Das Lied der Deutschen’, whose third stanza is now the German national anthem, as well as a number of popular children’s songs.

Chapter III: Aachen

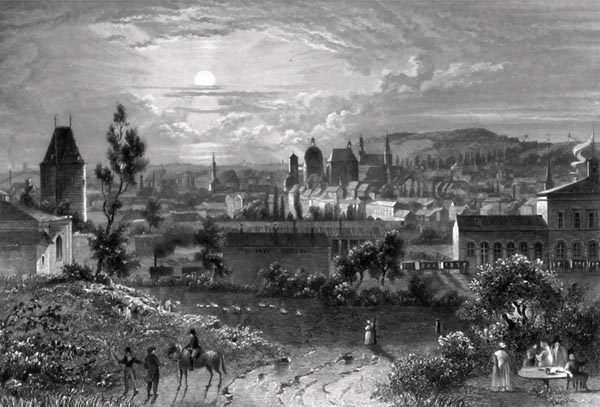

‘Aachen’ (page 391 of ‘The Kingdom of Prussia in picturesque original views...’ engraved by J. Poppel, 1852)

The British Library

In Aachen, Charlemagne lies,

In the old Cathedral there.

(Don’t confuse him with Karl Mayer,

Who in Swabia has his lair.)

I’d dislike being dead and buried,

In Aachen Cathedral, as emperor;

I’d rather be the least of poets,

Alive, in Stuttgart am Neckar.

‘Aachen Cathedral’ (page 385 of ‘The Kingdom of Prussia in picturesque original views...’ engraved by J. Poppel, 1852)

The British Library

In Aachen the dogs are bored,

And humbly beg in the street:

‘Grant us a kick, O stranger,

And make our day complete!’

I strolled around the tedious town,

For an hour, it must have been,

Seeing Prussian soldiers there;

Twas the old familiar scene.

They still wore their coats of grey,

Those with the high red collar,

(Red, for the blood of the French,

So sang the poet Körner).

Still that wooden, pedantic crew,

With angular arms and feet

When marching, faces frozen

With that self-same conceit.

They still march as stiffly,

Still as perfect on parade,

As if they’d swallowed the cane,

That on their backs was laid.

Yes, the rod never wholly vanishes,

They just bear it secretly.

The familiar and informal ‘You’,

Recalls the old impersonal ‘He’.

While the broad moustache,

Is just the latest style of braid,

What used to hang behind

Now beneath the nose arrayed.

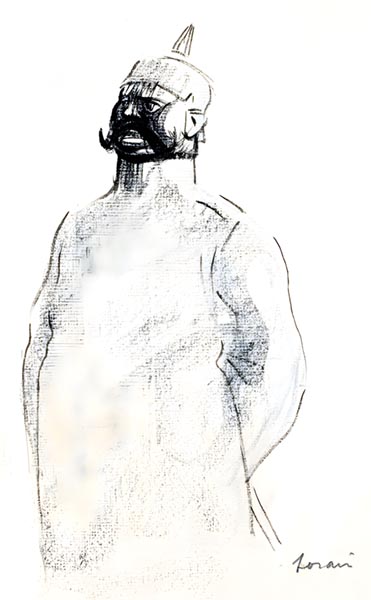

‘Prussian Soldier (c. 1919)’ - Jean-Louis Forain (French, 1852-1931)

Artvee

I rather liked the costume

Of the knights; I must praise,

The Pickelhaube especially,

That spiked helm, borne always.

It’s so chivalrous, reminding us,

Of the lost romance folk seek,

Of ‘Johanna von Montfaucon’,

Of Baron Fouqué, Uhland, Tieck.

It recalls the Middle Ages,

Its lords and squires, I find,

Who bore loyalty in their hearts,

And a coat-of-arms behind;

Of crusades and tourneys,

Love, the duties of a knight;

Of the unprinted age of faith,

Not a newspaper in sight.

Yes, I like that helm, a testament

To the exercise of wit!

It was a noble, royal idea!

With an edge, a point to it!

Yet I fear, when a storm arises.

Its shaft will deal a jolt,

To the Romantic head, drawing down

A modern lightning bolt! –

At the Post Office, in Aachen,

I saw that bird, once more,

I hate so! Full of venom

It gazed down, as before,

You ugly bird, if you ever

Fall to my vengeful hand,

I’ll pluck out those feathers,

And those talons, where you stand.

Then I’ll perch you on a pole

High up, beneath the sun,

And summon Rhenish hunters,

To shoot at you for fun.

And on whoever brings you down,

A sceptre and crown, I’ll bestow,

And calling out ‘Long live the King’,

A fanfare we will blow.

Notes: Karl Friedrich Hartmann Mayer (1786-1870) was a German jurist, and a poet of the Swabian school. Carl Theodor Körner (1791-1813) was a German soldier-poet, who died fighting the French, see his ‘Lied der schwarzen Jäger’. ‘Johanna von Montfaucon’ is a play, written in 1800, by August von Kotzebue (1761-1819), set in the fourteenth century. The author, Friedrich Heinrich Karl de la Motte, Baron Fouqué (1777-1843) romanticised and sentimentalised Germanic history. Johann Ludwig Uhland (1787-1862) was a poet, philologist, literary historian, lawyer and politician who found material for his literary works in the history of the Middle Ages. Johann Ludwig Tieck (1773-1853) was a poet, novelist, translator, and critic, and a founding father of the German Romantic Movement. The ugly bird is, of course, the Prussian eagle.

Chapter IV: Cologne

Late one eve, I reached Cologne,

The Rhine’s flow I could sense;

The German air, it fanned me,

I felt its influence –

On my appetite! And so, I ate

Pancakes, with ham sliced fine,

And since the ham was salty,

A flask of Rhenish wine.

The Rhine wine still shone like gold

Behind the rummer’s green glass.

Drink a few too many,

And up your nose, it’ll pass.

What can one feel but bliss,

The nasal tingling’s so sweet!

It drove me into the twilight,

Out into the echoing street.

The houses gazed, stonily,

As if they’d a tale to tell me,

Some legend from ancient times.

Of Cologne’s holy city.

Yes, here the clergy, once,

Practised their pious rites,

And the Dunkelmänner ruled,

Of whom Ulrich von Hutten writes.

Here the can-can of the Middle Ages,

Was danced by monks and nuns,

And Hoogstraaten, Cologne’s Menzel,

Denounced its errant sons.

Here the flames of the pyre

Devoured both books and people,

And Kyrie Eleison was sung,

To the bells in the steeple.

Here in the streets Stupidity

And Malice, like dogs, mated,

Their progeny still known today

For their religious hatred.

But see there, in the moonlight!

The building is colossal!

Its towers devilishly black,

That’s Cologne Cathedral.

Built to be the mind’s Bastille,

The cunning Papists’ fondest wish

Was that in that giant prison,

German thought would languish!

Then Luther came along,

And, at his cry of: ‘Halt’,

Construction was suspended,

Somewhere above the vault.

It’s incomplete – which is fine;

In its very incompleteness

It’s an emblem of German strength,

And of Protestant success.

‘Cologne Cathedral’ (page 457 of ‘The Cathedral of Cologne (Der Dom In Cöln)’ engraved by J. Poppel, 1852)

The British Library

You rascals, friends of the place,

With feeble hands, and nervous,

Desire to complete the work,

And top off the old fortress!

O foolish folk! All in vain

With a silver plate you sidle

To beg from heretics and Jews:

A fruitless task, and idle.

All in vain, the great Franz Liszt

Performs his benefit,

A king, with eloquence, declaims;

In vain, both do their bit.

The work will not be finished,

Though the Swabian fools have sent

A shipload, complete, of stone,

Merely lacking the cement.

The work will not be finished,

Despite the owl’s and raven’s cry,

Who, old-fashioned in their ways,

Like to nest in spires, on high.

Yes, the day may even come,

When instead of its completion,

The space inside will stable

Many a mare and stallion.

‘And if it becomes a stable,

What shall we do then,

With the relics that rest therein,

Tis said, of the Three Wise Men?’

That’s what I hear you ask.

But why, indeed, should we care?

The Three Kings from the Orient,

Must simply rest elsewhere.

Take my advice, and stick them

In those three iron cages,

High on the tower, in Münster,

Of St. Lambert’s, there for ages.

The tailor-king, he sat in one,

His councillors in the others,

But now let’s use the baskets

For these three royal brothers.

On the left can sit King Melchior,

On the right, King Balthasar,

In the midst King Gaspar, God knows,

What lives they lived afar!

The Holy Alliance of the East,

Which is now canonised,

Perhaps was not, in action,

Always so good and wise.

Balthasar and Melchior

Were two dolts maybe,

Who promised a constitution

For the kingdom, foolishly.

And later failed to keep their word –

While Gaspar, King of the Moors,

Repaid, with rank ingratitude,

His people’s loud applause.

Notes: The Dunkelmänner were Christian humanists of the Reformation, authors of the ‘Epistolae obscurorum virorum’ a collection of satirical Latin letters which appeared between 1515 and 1519 in Haguenau. Ulrich von Hutten (1488-1523) was a German knight, scholar, poet and satirist, and later a Protestant reformer. Jakob van Hoogstraaten (1460-1527), a Brabantian Dominican theologian, supported Johannes Pfefferkorn, a Jewish convert to Christianity, who sought to ban and destroy Hebrew books, against Johann Reuchlin (1455-1522), a Catholic humanist and scholar who defended them. Wolfgang Menzel (1798-1873) was a poet, critic and literary historian, and a strident opponent of Heine. The three iron cages hanging from the tower of St. Lambert’s in Münster held the corpses of three Protestant Anabaptists, executed in 1536 for fomenting rebellion. Their leader John of Leiden was a tailor’s apprentice.

Chapter V: Cologne – Continued

When I came to the Rhine Bridge,

From the bridgehead, I could see,

Father Rhine, there, flowing by,

In the moonlight, quietly.

‘Cologne (1824)’ - J.M.W. Turner RA (British, 1775–1851)

Wikimedia Commons

‘Greetings, dear Father Rhine,

How have you fared, old sire,

I’ve often thought of you

With longing and desire.’

Then I heard, deep in the water,

In a strange and gloomy tone,

Much like an old man coughing,

A softly-murmured groan:

‘Welcome, my boy, I’m glad

You’ve not forgotten me,

I’ve not seen you for thirteen years,

And I’ve been ill, you see.

At Biebrich I swallowed stones,

Truly, I’ve tasted better,

But heavier on my stomach lies,

The verse of Nikolaus Becker.

He sang of me as if I was

The purest maiden ever,

Who would deny every thief

That sought to steal her honour.

When I hear that stupid song,

I long to pluck my beard,

(Before I go drown myself),

And swallow it when it’s sheared.

That I’m certainly no virgin

The French have discovered,

Having mixed their waters

With mine, when they’re uncovered.

That stupid song, that foolish man,

Embarrassed me, shamefully,

And in a certain sense he has

Politically compromised me.

For if the French return now,

I can only blush anew,

I who’ve waited, tearfully

Praying that’s what they’ll do.

I’ve always liked them greatly,

The French, the little darlings,

Do they still wear white breeches,

And leap about while singing?

That street-urchin, De Musset,

Will lead them here, maybe

Beating out, on his drum,

Those sad jokes aimed at me.’

So, Father Rhine lamented,

Oozing discontent,

I spoke awhile, to lift his spirits,

Such, at least, was my intent:

‘Oh, fear not, Father Rhine,

The Frenchman’s mockery,

Their breeches gone, instead

New trousers you would see.

Not white they are, but red,

The buttons have changed too,

No longer do they sing or leap,

They’re thoughtful, just like you.

They philosophise, and speak

Of Fichte, Kant and Hegel,

Smoke tobacco, and drink beer,

And even play bowls a little.

They’ll soon be Philistines like us,

Or, worse, they’ll go farther,

Followers of Voltaire no more,

With Hengstenburg their master.

While De Musset, to be sure,

That ‘urchin’, should be hung,

We’ll be sure to still

His shameless, mocking tongue.

And if he drums up some bad joke

Or other, we’ll pipe worse,

We’ll shrill what he gets up to

With fair women, and lame verse.

Flow softly then, Father Rhine,

Don’t fret at one poor tune,

You’ll soon hear a better song.

Farewell, I’ll see you soon.’

Notes: The ‘Rhine Bridge’, at that time the only one spanning the river there, was the Deutzer Schiffbrücke (the Ship Bridge) a pontoon bridge connecting Deutz and Cologne, opened in 1822. Biebrich (Biberich) Palace, beside the Rhine, upriver from Cologne, was the main residence of the Princes and Dukes of Nassau. Nikolaus Becker (1809-1845) was a German lawyer, and poet. His sole work, of note was his patriotic ‘Rheinlied’ (‘Rhine Song’,1840) many times set to music. Ernst Hengstenberg (1802-1869) was a German Protestant theologian and Old Testament scholar.

Chapter VI: Cologne – Continued

Paganini, always had, at his side,

A familiar spirit, sometimes

It appeared in the form of a dog;

Georg Harrys, at other times.

Napoleon saw a man in red,

When great events were in train.

Socrates had his daemon,

No slight product of his brain.

I myself, at my desk, at night,

Have sometimes seen, behind me,

A sinister guest, standing there,

Masked, and out to find me.

Under his cloak he held

(I simply give the facts),

Something that gleamed, in the light,

Like an executioner’s axe.

He seemed of solid stature,

Each eye shone like a star,

He let me write, untroubled,

Watching, quietly, from afar.

I hadn’t seen him for a while,

Twas a great relief, I own,

But suddenly I saw him there,

In the moonlight, in Cologne.

I strolled, musing, down the street,

He followed me, at will,

Like a shadow, and when I stopped,

He stopped too, and stood still.

He stopped there, as if waiting,

I sped on like a hare,

Yet he pursued me, till

I reached the Cathedral square.

It was unbearable, I turned

And said: ‘Tell me, aright,

Why follow me where’er I go,

In the middle of the night?

I always meet you at a time

When base feelings elevate,

And inspiration fills my brain,

Although the hour be late.

Fixed and firm is your gaze,

Speak: what’s that gleam, unstill,

You hide beneath your cloak?

Who are you, what’s your will?’

He merely answered, drily,

Even phlegmatically,

‘Don’t seek to exorcise me, pray,

Quite so emphatically!

I’m no ghost from the past,

No scarecrow from the grave,

I’m no friend of rhetoric,

It’s philosophy I crave.

I’m practical by nature,

I’m calm, and silent too,

But know: whatever you conceive

In mind, that, I will do.

And even if long years go by,

I’ll not rest till I enact

Your thoughts as true realities;

You think, and I will act.

You are the judge, the bailiff, I,

Who’ll play the servant’s part,

I’ll execute the sentence,

Though unjust, that you impart.

In ancient Rome, they bore an axe

Before the Consul; you’ll find

You too will have your lictor,

But the axe will go behind.

I’ll be your lictor; and will walk

Behind you, as I ought –

Carrying the gleaming blade,

And acting out your thought.’

Chapter VII: Cologne – Concluded

I returned to the inn, and slept

As if the angels rocked me.

One sleeps so sound in German beds,

The feathers plump so softly.

How oft I’ve missed the pleasure

Of my own native pillow,

Exiled, in the sleepless night,

A hard mattress there below!

One sleeps so well, and dreams so deep,

On one of our featherbeds;

There the German soul feels free

Of the earthly chains it dreads.

The soul feels free, and soars on high

Midst Heaven’s furthest gleams,

O German soul, how proud your flight,

In your nocturnal dreams!

The gods grow pale, when you draw near!

You have kindled, on your way,

Many a star as you passed by,

With your wingbeats, so they say!

The French and Russians hold the land,

While Britain rule the waves,

But the airy realm of dreams,

Is the realm our being craves.

There is our hegemony,

There we are united,

Let other kingdoms remain

With their flat earth, delighted…

And as I fell asleep, I dreamed

I strolled, though not alone,

In moonlight, through the echoing streets,

That form ancient Cologne.

There, behind me, walked, once more,

My dark, hooded, shadow,

I so weary my knees gave way,

Yet onwards we did go.

Onwards we went, although my heart

Showed in my gaping chest,

And all about the red drops fell,

From the wound at my breast.

Now and then, my fingers dipped

Within, and now and then,

I smeared the doorposts with blood,

As I passed them, one in ten.

And every time I marked a house

With my fingers, as I say,

Softly and sadly a passing bell,

It seemed, tolled far away;

While, in the sky, the moon,

Grew ever darker and dimmer,

Wild clouds like black stallions

Obscuring her pale glimmer.

And always there behind me, he

Gripped his hidden weapon,

That dark figure – thus, we two

Kept wandering on and on.

On and on, till, once again,

In the Cathedral square,

The doors stood open wide,

And we two entered there.

Within that vast space, only

Death, night, and silence reigned,

While lamps burned here and there,

Thus, light the darkness framed.

I walked amongst the pillars,

And nothing more I heard

Than my companion’s footsteps,

For he uttered not a word.

We reached a place that shone

With gold and jewels bright,

The Chapel of the Three Kings,

Glowed in the candlelight.

Those three wise men, however,

Who silent once did lie,

A miracle, sat upright

On their sarcophagi!

Three skeletons, in fancy dress,

With crowns upon their heads,

And sceptres in their bony hands,

They’d risen from their beds.

Like jumping-jacks, they twitched

Their long-dried yellow bones;

They smelt of ancient mould,

With resinous overtones.

One even worked his jaws,

And gave a lengthy speech,

Explaining why respect was due

To all of them, and each.

First, because they were all dead,

And secondly, were kings,

And thirdly they were holy,

With the cachet that it brings.

Unmoved, and smiling bravely,

‘In vain, your rod you cast!’

I cried: ‘In every way, I see

You’re rooted in the past.

Off with you! Deep in the grave,

Is your proper place,

The treasures of this chapel

Life’s coffers now will grace.

The merry cavalry’s fine steeds

Will dwell within these walls

And if you don’t go willingly,

You’ll dislike what befalls.’

So, I spoke, and turned my head,

And saw the dread blade shine.

Twas my companion’s dreadful axe.

He understood my sign,

Drew near, and with his axe-blade,

The bones of superstition,

He shattered all to pieces,

With merciless precision.

The echo of those blows rang forth

From every vault; there broke

From out my chest great streams of blood –

And, suddenly, I awoke!

Note: Johann Georg Carl Harrys (1780-1838) was a German journalist and author, who accompanied the violinist and composer Paganini on a concert tour, in 1830, and published in that same year a memoir entitled ‘Paganini in his Travelling Carriage.’

End of Part I of Heinrich Heine’s ‘Deutschland: Ein Wintermärchen’