The Theatre of Words

The Poetry of Arthur Rimbaud

by A. S. Kline

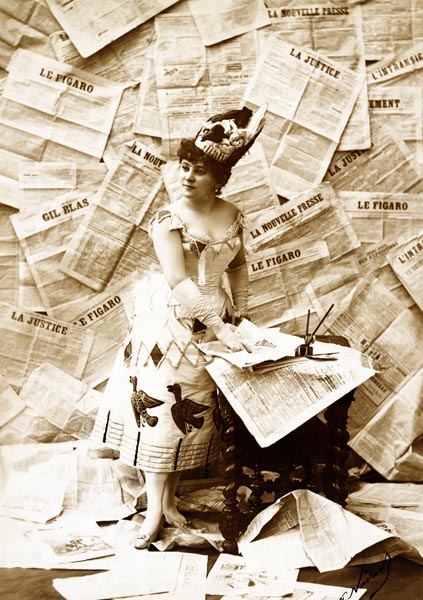

Mlle Beaumaine, Théâtre des Variétés’

Paul Nadar (French, 1856 - 1939)

Getty Open Content Images

An original work by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2024 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- I: Introduction: The Theatre of Words

- II. The Early Poetry (1870-72)

- III. Illuminations (1872-1874)

- IV: ‘Une Saison en enfer’ (1873)

- V: Conclusion

I: Introduction: The Theatre of Words

What should we make of Rimbaud? How to respond to a voice as seductive as that of Baudelaire or Rilke, and perhaps more dangerous to the uncritical mind than either? In a lightning-stroke of literary effort, in a mere five years, between 1870 when he is fifteen years old, until early 1875 when he is twenty, Rimbaud takes on the mantle of Baudelaire, and to all and intents and purposes exhausts and completes Baudelaire’s journey. A journey of words, that is, or rather in Rimbaud’s case of the ‘theatre’ of words, since from the first, he perceives the separation inherent in Romanticism between the Romantic author and the work, the aspiration and the reality, the conscious life and the subconscious prompting. ‘I,’ indeed, ‘is another’, as he wrote in the so-called ‘Voyant’ letter to Paul Demeny.

Rimbaud is the heir of that Romantic yearning which Baudelaire assimilated, and re-presented; a desire, a wish, a prayer even, for the greater ‘something’, that might transcend mundane existence, and justify the life both of the intellect and of the poetic sensibility. The waning of theology, and the advance of Newtonian science, had revealed a view of the Void that challenged the beliefs and rituals of their age. Baudelaire’s fractured vision is of modernity; of humankind divided from nature in the toils of the city, divorced from a ‘vanishing’ God in whom it is harder to believe, plagued by the gulf between the sexes, and a slave to contemporary (bourgeois) materialism. And so Baudelaire, shortly before Rimbaud (in ‘Les Fleurs du mal’, first edition 1857, second edition 1861), sought, through the ‘alchemy’ of words, to change mud into gold, while Rimbaud subsequently appropriated that aspiration to alchemy in his own work, deeply influenced by Baudelaire’s efforts.

Rimbaud’s turbulent adolescence and subsequent rejection of literature and the West, in favour of a life of commerce and trade in North Africa, has caused him to be labelled the archetypal modern ‘rebel’. But one should be precise about the nature of that rebellion. Like Baudelaire he partly adheres to the Catholic religion of his childhood, seemingly to the end of his life, though it is constantly dissolving before him. Despite his apparent rebellion, his poetic excursions, whether in more traditional verse, or in the poetic prose of ‘Illuminations’ and ‘Une Saison en enfer’, nonetheless present material from the past, (elements of the Classics, of his earlier life, of historic events in France, of the contents of his reading) or weave that material into his fantasies; attempts, as Baudelaire would have it, to create ‘artificial paradises’, or in Rimbaud’s case to acknowledge spiritual hells also, and to resolve the problems of his real mental states, only partly generated by the society around him.

Like Baudelaire, he was haunted by the conditions of his childhood. In Rimbaud’s case these constraints were due to an absent militaristic father, a harsh and severe mother, a hothouse education, the claims of early religious devotion, the provincial bourgeois life around him, and the pressures of his own precocious intellect. Rimbaud’s rebellion stemmed from that intense upbringing, and he certainly ran wild in escaping it, but his deepest loyalties and affiliations in literature thereafter are nonetheless to the past, and the tradition, to religious images and concepts, to memories of the events of childhood and youth. He indeed resists material progress, in the form of technology. He favours alchemy over the true sciences, and, in the end, the simpler world of the African continent to the more complex world of Europe. His rebellion then is not against the past, but against the personal issues and problems of the present, coupled with the threat of a scientific and materialistic future; a rebellion prompted by the desire to justify human existence, to revivify it, and to populate the void, the abyss that Baudelaire perceived, with vibrant forms; and to find the lasting love and affection which eludes him.

Baudelaire’s call to sail into the unknown to ‘find the new’ is not answered by Rimbaud except inasmuch as he is an innovator in literary style (though we should remember that in many cases he developed stylistic elements already found in Baudelaire’s verse and prose-poems). Rimbaud was born too early to possess a deep scientifically-informed view of human history (though Darwin had published The Origin of Species, in 1857), or of the universe as revealed by post-Newtonian physics and astrophysics, or of an ecological approach to Nature, or of the long-overdue re-orientation of the sexes towards equality and equivalence. The society he rebels against is the stifling society of his childhood and youth. Like Baudelaire he is essentially apolitical, showing no inclination to change the world, but rather to achieve personal freedom, and ultimately to do so amongst the exotic trappings of past or alien cultures, rather than by addressing the truly modernist future. There is a deep hidden irony, as well as the overt sarcasm, in his statement in ‘Une Saison en enfer’, that one ‘must be absolutely modern’. His ultimate embrace of the modern material world that he had scorned, and within a colonial ethos, was a complex act of renunciation and acquiescence; of despair perhaps, but despair accompanied by a hope of personal salvation through the greater simplicity and the absoluteness of North African life. Yet there is an unintended irony in his abandonment of the West for the supposedly modern, since he thereby ignores and neglects deeper contemporary trends within western society, for example the development of science beyond naïve materialism, the recognition of the origins of our species, and a wider existentialist confrontation of the intentionless universe by the human intellect.

Once his rebellious phase is done with, along with his adolescence and early youth, Rimbaud rejects the theatre of words, and opts for silent activity in a harsher landscape. He embraces the straightforward materialism of trade, after the failure of his literary ‘alchemy’, lacking perhaps the inspiration and spiritual conditions necessary to develop his literary work further, or to explore, philosophically, the deeper nature of humanity, the developments of modern scientific and ethical thought, the political movements within society, or the nature of his own psyche. He came to terms with his past, it seems, by burying it in the soil of Ethiopia. Camus thought Rimbaud’s later life a failure. That is a harsh judgement. Africa may have offered the only resolution of his inner problems possible to him. Literature is not everything: ‘I, is another.’ And those who seek salvation in the theatre of words, may be sadly disappointed. Camus, I suspect, like many another, misunderstood the nature of Rimbaud’s rebellion, which was in the end neither intellectual nor literary.

By using the phrase ‘the theatre of words’, I wish to draw attention to the theatrical, dramatic nature of Rimbaud’s work. Even in the earliest poems he sets out to create a scene, a piece of theatre, even, that is, in his autobiographical verse, by placing significant distance between himself and the subject, or the memory invoked. Rimbaud is a literary ‘photographer’ in an age of early photography, a stage-designer who in the ‘Illuminations’ and ‘Une Saison en enfer’ creates the backdrops to, and characters of, his drama. The theatrical element lends a particular vividness to his verse, while fairy-tale, legend, heroic epic, and the repertoire of myths provides ample material for his invention. Rimbaud is not an analyst of his times, Baudelaire had already nigh-on completed that task, rather he is a witness to them, a syncretist, mingling many images together, in order to endorse Baudelaire’s vision, express the existential void with intensity, and amplify the yearning for a truer life, before turning from literature to reality, in order to seek that true life and save himself. The Surrealists, among others, were strongly influenced by Rimbaud, in that his alchemy of the word sought, as in historical alchemy, to merge and mingle harmonious elements in order to turn the base dross of his existence into an emotional and intellectual precious metal, though the Surrealists tended to juxtapose not harmonious but rather incongruous or conflicting elements, in order to startle and awaken the observer. Was Rimbaud writing for any other observer than himself? He seemed scarcely interested in the publication of his later work.

Only, I think, in ‘Illuminations’ is Rimbaud truly a proto-Surrealist, since therein he opens the door to the extensive use of dreamlike states, and intense deployment of the imagination, in both literature and the visual arts. Wherever his inspiration comes from however, he is always in control of his material. It was not literature he was after: he perhaps despised it as much as Byron did the literary world, a poet for whom reality was far preferable. What Rimbaud seeks is a transformation of the soul, or rather the mind and spirit, through the pure use of words, rather than by means of analytical thought, or philosophical speculation.

It may seem that Rimbaud, while immensely assured and adult in his writing, was simply too young for his own talent, and intellectual power, and burnt out before his thought progressed far enough. Modernity, by contrast, if it is anything, is the mind in the embrace of both the arts and the sciences, in an attempt to place human existence in context within the history of the species, and within the universe, and thereby address the inner challenge of the void, which is as potent to the thoughtful sensibility, now, as it was to Baudelaire and Rimbaud. Empathetic to his attempts at alchemy, we should recognise his unfulfilled intellectual potential, given the assuredness and brilliance of his youthful art. However troubled, and at times obnoxious in consequence, he was in his early youth, we should also note that his early death prematurely ended what may well have proven the most fulfilling period of his life, despite the harshness of his surroundings, one in which, with maturity, he found friendship and respect.

II. The Early Poetry (1870-72)

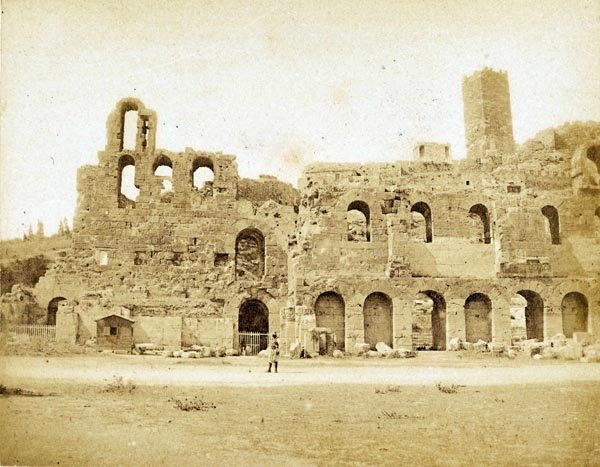

‘Théàtre Hérode Atticus’

Félix Bonfils (French, 1831 - 1885)

Getty Open Content Images

In the ‘Voyant’ letter to Demeny, at the age of fifteen, Rimbaud set out his manifesto. He declares that inspiration arises despite the conscious self; ‘the symphony begins in the depths, or springs with a bound onto the stage.’ Here already is the theatrical flourish. He adds that ‘the first study for the man that wants to be a poet is true complete knowledge of himself.’ Rimbaud goes on to advocate ‘the disordering of all the senses’, and in a passage that advances Baudelaire’s poetic effort has the poet arriving ‘at the unknown.’ This is a young intellect seizing on Baudelaire’s program of sorts for ‘Les Fleurs du mal’ and re-expressing it in his eagerness. The poet will become, it seems, through use of the imagination, ‘an enhancer of progress’, his poems will be filled with ‘number and harmony’ and ‘we should demand ‘new things from the poets – ideas and forms.’

Does Rimbaud follow his manifesto in his early poems? I suggest not. The forms he employed in his early work were mostly pre-empted by Baudelaire, who also set the scene for his ideas. The extent to which the poems arose from subconscious promptings is not made obvious, and was known only to himself. The senses, as displayed there, are not obviously disordered or deranged, though it is true a single often-quoted poem ‘Voyelles: Vowels’ attempts to create a Baudelairean ‘correspondence’ between vowels, and sounds, colours, and images. Nor is Rimbaud noticeably an advocate of progress towards the ‘unknown’ in literature or life, per se, while he treats mere materialistic progress with scorn.

It is then an adolescent manifesto, though skilfully expressed in adult terms; one heavily influenced by Baudelaire, its derangement of the senses executed more evidently in action, in his days ‘on the road’, in the early part of his affair with Verlaine, and in his provocative behaviour in Paris, than in literature. But it is nonetheless a manifesto genuinely felt and expressed, while his harmonious use of images, and his theatrical echoing of emotions and ideas through symbolic visual equivalents, in his later adaptation of the Baudelairean poetic-prose form, both in ‘Illuminations’ and ‘Une Saison en enfer’, goes some way to justifying this earlier statement of intent. He does indeed find a way, as Baudelaire advocated, through the (literary) unknown, to achieve the new.

The key poems of his early work may be grouped loosely according to theme, as follows, though a given poem may appear in more than one of my suggested groupings. There are, firstly, the vaguely erotic poems of seduction, and of sexual or sensual fantasy: including ‘First Evening’, ‘Romance’, ‘A Winter Dream’, ‘The Sly Girl’, ‘The Seekers of Lice’, ‘Sun and Flesh’, ‘Ophelia’, and ‘First Communions’. The first four are essentially playful descriptions of real or imaginary situations. Precedents in Baudelaire’s work, though not equivalents, are ‘Il aimait à la voir’, ‘A Phantom II: The Perfume’, and ‘Afternoon Song’. Rimbaud’s latter four, though, break new ground in terms of content.

‘The Seekers of Lice’ is an imaginary, or perhaps auto-biographical, description of a state of sensual perception, with a fairy-tale or semi-mystical element that is wholly original, embodied in the images of the two sisters. Here Rimbaud achieves a hallmark of his later prose-poems where fantasy and reality blend in potent images or symbols that elude precise meaning, while evoking emotional or spiritual states.

‘Sun and Flesh’ is an even more important landmark poem, which displays Rimbaud’s yearning for the ‘living’ past, and a world beyond the mundane and deathly (to him) provincial background of his childhood. His longing for Cybele (the Great Mother) here is perhaps the yearning for a real mother other than his own, one who might have offered sensual abundance rather than constraint, in the manner of Baudelaire’s ‘mistress of mistresses’. Within the poem he articulates the waning of the pagan religion of love, and its transformation into a harsher religion of Christian love, and yet simultaneously (as in the early French Revolution) into a quasi-atheistic celebration of humankind as the supreme power. Yet ‘Man is finished! Man has played every part!’ and so Rimbaud invokes a re-awakening ‘free of all his deities’ which will result in the return of Cybele/Astarte/Aphrodite. He further invokes a series of Greek gods and mythological characters in sensual episodes, to reinforce his point, extolling the virtues of the pagan mindset. His struggle to embrace both Christianity and its decline (Baudelaire’s ‘vanishing God’), is evident here, along with the related struggle to deal with the constraints of his childhood and early youth, including conventional religion, and a belief that humankind has already exhausted life’s possibilities. While the thought process is immature and confused, the articulation of these three key themes is highly significant for his later work. Their interplay is the source both of a dangerous negativity, generated by real philosophical and spiritual issues, and a fertile literary creativeness. They both make him as a poet, and potentially ruin him as an individual. His ability to survive the negativity, may not have rendered him especially loveable, but it is a tribute to his resilience and strength of will. If renouncing literature and the bourgeois West was his means of defying the negative psychic forces within himself, and re-orientating both his personality and circumstances, then it may well be regarded as a triumph and not a failure.

‘Ophelia’ is a beautiful piece of descriptive writing, the subject deriving from Shakespeare's play Hamlet, that again evidences Rimbaud’s ability to conjure up a mysterious, mystical and dreamlike atmosphere, reminiscent of fairy-tale and legend. Nonetheless there is a sexual element here, and Ophelia is in some sense I think the ‘sacrificial’ girl who is also the subject of ‘First Communions’, a sensually intense poem that reveals and attacks the erotic subservience of the female sex to the strictures of conventional religion, and in doing so evidences Rimbaud’s own feelings of sexual and intellectual constraint prompted by his early upbringing and education. Provincial life and its narrowness are also scorned here, while both themes evidence his accusation that Christ is the ‘thief of vigour’, displaying Rimbaud’s extreme ambivalence towards the religion which he is both committed to and despises. This emotional confusion, a crisis of faith and unfaith, from which he seeks release, often explosively, is one source of the power and intensity behind his poetry.

A second grouping is of poems of warfare and revolution: these include ‘The Blacksmith’, ‘Jeanne Marie’s Hands’, ‘Eighteen-Seventy’, ‘The Famous Victory of Saarbrucken’, ‘The Parisian Orgy’, ‘Rage of the Caesars’, ‘Evil’, and ‘The Sleeper in the Valley’. ‘The Blacksmith’ is a fine evocation of the French Revolution and the new-found power of the common man, while ‘Jeanne-Marie’s Hands’ evokes the corresponding role of the revolutionary women. ‘The Famous Victory at Saarbrucken’, ‘1870’, ‘The Parisian Orgy’, and ‘Rage of the Caesars’ are poems of the Franco-Prussian War, including the French victory at Saarbrucken (one of very few in that conflict), and the suppression of the Paris Uprising of October 1870, with the last poem quoted being a portrait of the complacent, and in Rimbaud’s view tyrannical, emperor Napoleon III. These poems position Rimbaud on the political left, supportive of rebellion, and also in deep sympathy with the fate of the ordinary soldier, as exemplified in the more tender ‘Evil’ (which renders the Christian god as a god of sorrows) and ‘The Sleeper in the Valley’. Rimbaud, in his literary life, seems not to progress politically beyond these early poems of revolt, rebellion, and empathy with the underdog, and this group of poems derive as much perhaps from his own inner state of revolt and rebellion against his upbringing as from wider considerations, which is not to denigrate the genuineness or validity of his intentions here. In his later work and life, he appears to be as fundamentally apolitical as Baudelaire whose approach to society is similarly from the moral, ethical and emotional direction rather than the political.

That upbringing is highlighted by a group of auto-biographical, or semi-autobiographical, poems, which express the rebellious moods of his childhood, and his escape into temporary and then more permanent freedom, initially by leaving Charleville and his mother, and then after a brief return departing to meet with Verlaine in Paris. These poems express his desire for a freedom-from, though they fail to deliver a freedom-for. They express his childhood and youthful frustration, his delight at finding himself ‘on the road’, but also the potential failure of mere freedom as a solution to his spiritual anguish, and underlying melancholy. Rimbaud came to be seen as the poet par-excellence of rebellion, which is a fair assessment, but also as a guide to the life to be followed, one of permanent rebellion, whose proponents may equally be interpreted as having failed to develop spiritually and socially beyond adolescence, or as hypocritical wearers of theatrical masks to be shed or adopted at will, according to the needs of those proponents and their followers.

Rimbaud, I would maintain, is dangerous if seen as a guide, being a man who himself relinquished his literary past, and found a materialistic way to address his inner needs, and in so doing stay true to himself. He was never a leader of any social cause or literary school, rather he strove to achieve not only personal freedom from what plagued him inwardly but a reason to continue existing, by embracing a mode of life far from fame and poetry, one that might offer him a just reward for his endeavours, as well as friendship free from turmoil.

These earlier autobiographical poems include: ‘Poets at Seven Years’ and ‘Memory’, as well as his poems ‘on the road’ namely ‘My Bohemia’, ‘At the Green Inn’, and ‘The Sly Girl’ the latter of which has already been mentioned, as well as perhaps the fullest expression of his yearning for freedom, and his failure at the time to find a purpose for that freedom, ‘The Drunken Boat’.

‘Poets at Seven Years’ is clearly an autobiographical display of his childhood situation and his inner response to it: his strict mother, secretly loathed, his rebellious hidden responses, his yearning for space and peace, his unrewarding provincial peers, his sexual stirrings, his literary attempts filled with visions of exotic climes, the dreary Sundays, his hostility to conventional religion, his longing for escape.

‘Memory’ exemplifies Rimbaud’s ability to depict scenes theatrically, operatically, or photographically, staged and captured frozen instants, swift flashes of perception, vividly expressing a mood, or predominant emotion. Here nature is used to convey a mood of stasis, a state of suspension, in which the mother and her children must suffer the father’s departure, and subsequent absenteeism (vanishing much like the god of their religion?). The boy stretches for the toy boat, which is just out of reach, like the yellow flag that might offer a brighter future, and the blue faded iris whose reflection might offer peace and calm. He and his toy boat are identified one with the other, and both equally stuck fast in the ‘mud’ of the present. These verses certainly evidence the lack of an alchemy that might transform life; they rather recall Baudelaire’s ‘Alchemy of Sadness’ a process that achieves the reverse, turning gold into iron, and yet as Baudelaire claimed he himself had, Rimbaud does succeed in changing that mud to poetic riches.

The three poems identified here with Rimbaud’s escapades on the road in 1870, celebrating his first new-found bohemian freedom as a servant of the Muse, are beautifully-written vignettes, the first of the poet sleeping under the stars, the second and third of scenes at the Green Inn, at Charleroi in Belgium. But a deeper perception of his plight, his bid for freedom and its questionable outcome, is contained in the important poem ‘The Drunken Boat’. There, Rimbaud identifies, symbolically, as he did in the poem ‘Memory’, with a sailing-vessel, and indeed returns in the last verses to the toy-boat of that poem. What precedes it is a journey of the unguided vessel of imagination, in which he escapes the sounds of torture and torment, to ride the ‘Poem of the Sea’. Here is Rimbaud’s version of arguably Baudelaire’s finest poem ‘The Voyage’, Baudelaire’s survey of the tedium of modernity, ending in a desire to flee into the unknown to find the new. Rimbaud’s is rather a voyage of imaginative ecstasy, fuelled by the word. Yet the brilliantly-described voyage ends in regret for the parapets of Europe, as the visionary images fade, leaving him exiled perhaps in a darkness that may conceivably signify a more successful future, though the final stage of the journey is a longing and nostalgia for the past, for that toy-boat of childhood.

Rimbaud had expressed his desire for freedom, but had not as yet discovered what to make of that freedom. His deepening relationship with Verlaine appears not to have provided the answer, a relationship which ultimately foundered. A cluster of free-standing poems prior to ‘Illuminations’ testify to his sense of loss, frustration and incompleteness, including ‘The Rooks’ ‘Ballad of the Hanged’ ‘Evening Prayer’, ‘My Little Lovers’ ‘Teardrop’ ‘The Stolen Heart’, ‘The Sisters of Charity’, and the first versions of the poems ‘The Song of the Highest Tower’, ‘Eternity’, and ‘O Seasons, O Chateaux’. It is as though Rimbaud’s highs, the positivity of his literary imagination, inevitably lead to a reality of mental lows, akin to post-coital melancholy, the act of creation being followed by a passive, regretful or self-destructive mood. And lest such moods are ascribed solely to the defects of his upbringing, or of his inborn character and personality, I would contend that they are also in tune with the existential situation of religion, and philosophy, in his and our time. Like Baudelaire, his childhood and youth may explain why he was drawn to the issues of modernity, but do not explain or exhaust those issues themselves. Religion was indeed, intellectually, on the wane. Modernity was, and is, rightly seen as the source of estrangement, alienation, confusion and doubt. The intentionless universe may be seen as a welter of alien forms, or an empty Void, or both simultaneously, both a cornucopia and an ultimately purposeless abyss, as may human civilisation.

‘The Rooks’, ‘Evening Prayer’, and ‘Teardrop’ invoke moods of resignation, sadness, and regret. ‘Ballad of the Hanged’, strongly influenced by Villon and Baudelaire, is a cynical masque of life, death and the devil. ‘My little lovers’ addressed to the enthusiasms and aspirations embodied in his early poems, and their failure, is a poem that despairs of the alchemy of words, while ‘The Stolen Heart’ is a poem that rails at his perceived betrayal by the lover and the mob. All in all, not a happy picture of the free and creative Rimbaud, and yet the poems themselves that embody these negative emotions and perceptions are finely and bravely written, as if to highlight, as per the ‘Voyant’ letter previously quoted, the gulf Rimbaud saw between the artist and the work, between life and literature, between imagination and reality.

‘The Sisters of Charity’ is an important and more complex poem, which reveals a self-made portrait of the twenty-year old Rimbaud, proud of his acts of rebellion, and of his obstinacies, of those first poems indicative of his inner distress yet glittering like diamonds. He shudders at his own sensitivity, wounded by the ugliness of the world, its constraints and hostilities, and is ‘full of profound eternal emptiness.’ Help might have been found in Woman but he views Woman as a burden rather than being a ‘Sister of Charity’, the latter being one who might come to relieve suffering. The female Muse and the Goddess of Justice, who are Sisters of Charity he claims, only serve to kill Love. Nature, study, alchemy, all fail his Faustian character. Rimbaud therefore calls for the poet to embrace truth, dreams, and spiritual journeys (the content of ‘Illuminations’ and ‘A Season in Hell’) while calling on Death, as Baudelaire does at the end of ‘The Voyage’, to be the ‘Sister of Charity’ he so badly needs.

‘The Song of the Highest Tower’, ‘Eternity,’ and ‘O Seasons, O Chateaux,’ exemplify Rimbaud’s ability to conjure up a semi-mysterious scenario and mood, that resonates without the reader or listener quite knowing how or why, by employing his acute pictorial sensibility and symbolist imagination to convey emotion. The first is a poem of regret for his wasted youth, his lost or waning religious sense (note that the religious reference was removed from the version he employs in ‘Season in Hell’) and his longing for a love that might dissolve the boundaries between the lovers, and liberate the self for love and not merely from constraint.

The second, ‘Eternity’, invokes the mingling of sun and sea, an image of sunset, where the mind now calm is free to dream, and the embers of the dying day, speak of our ‘duty’ to exist with ardour and vigour, prior to, and in the absence of, the ‘at last’ of death (note that the meaning is clarified and sharpened in the later version). The symbols of sun and sea, also carry alchemical, sexual, and mystical overtones. The torments of existence, which are real, must be endured with patience, and without hope. The sea is a symbol of the endlessly present world of matter, the sun is a symbol of light and a promise of the light’s return.

The third poem acknowledges how poetry, and the attempted alchemy of the word, have possessed his life, and how the charm of poetic creativity has scattered his efforts. It is both a statement of regret, and an acknowledgement of a character ‘flaw’ within him, while at the same time being a celebration of the only project that truly roused his intellectual ardour and vigour.

III. Illuminations (1872-1874)

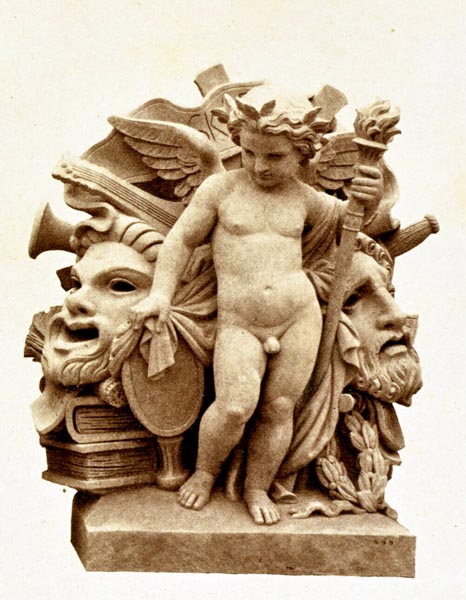

‘The Moulin Rouge’

Eugène Atget, photographer (French, 1857 - 1927)

Getty Open Content Images

In the prose-poems (and two examples of free verse) of ‘Illuminations’, a title indicating the coloured plates of illustrated books, as well as flashes of insight and inspiration, Rimbaud turned from the traditional, realistic style of his previous poetry to a radical technique in which the scenes depicted are a product solely of the imagination, but which through the use of symbolism and poetic phrasing create a mood, and express his existential state, his attitudes and his emotions. His views on society, displayed in the work, are condemnatory of modern civilisation and ‘progress’. The whole is tinged with resignation to the human condition and the materialistic future, while retaining his yearning for various forms of liberation.

In many of these poems, the quality, seductive charm, and imaginative vigour of the writing contrasts with the generally negative tendency of the content. Rimbaud’s brilliant pictorial abilities, and the smoothness of literary flow are undeniable, but vagueness of reference, symbolic ambiguity, and the difficulty of subjecting the content to wholly rational thought and analysis, can be simultaneously both stimulating and frustrating to the reader. The search for Rimbaud’s ‘meaning’, is often a difficult task. While many elements of the poems are employed symbolically, exactly what is symbolised may be hard to interpret. Rimbaud, given such use of symbols, many of which are, deliberately perhaps, ambiguous in terms of what they denote, is therefore viewed not just as a major poet of the Symbolist movement, but is also acknowledged as a significant influence on the Surrealists, through his use of novel and exotic imagery, and the free flow of the imagination. Rimbaud was aware, as in the Voyant letter quoted, of the powers of the ‘subconscious’ mind, while predating the use of the term subconscious itself. He appears though to have been in control of his poetic content throughout, and aimed at harmonious use of reinforcing images rather than assembling arbitrary elements in order to shock and raise awareness in the manner of Zen satori, or employing devices like automatic-writing in the manner of Surrealism to produce his linguistic material.

What follows here is an attempt to elucidate each poem, and extract, if possible, an analytical meaning from what was for Rimbaud an essentially non-analytical project, being rather an expression of thoughts and an articulation of feelings already substantially worked-through in his mind. Rather than simply a collection of isolated, disconnected pieces, I view the flow of the ‘Illuminations’ as a consistent, interconnected, sometimes serial, revelation of his thoughts, offered in a highly symbolic and brilliantly pictorial manner.

Illuminations I: After the Flood expresses a mood of calm after the deluge (a Biblical deluge of childhood and youthful experiences, of passion and of poetic inspiration), but also of yearning for the flood’s return. The commonplace world, of work and trade, is once more in action, ‘progress’ is in motion, the world is being re-populated, the status quo is re-established, and God’s promise, signified by the rainbow, apparently of a world without inspiration, a mundane world, is enacted. There are references to childhood, although the children are in mourning, and to religious observance. Eucharis, a nymph (who does not appear in Greek mythology, but is one of the nymph Calypso’s attendants in Fénelon’s novel Les Aventures de Télémaque, 1699), claims the setting as a new spring season. And yet Rimbaud exhorts the flood to return, along with its waters and sadness (a reference to the ecstatic journey and muted finale of ‘The Drunken Boat’ perhaps). The Queen, the Sorceress, is then a symbolic representation of Life or Nature, which anthropomorphically ‘hides’ its ‘precious stones’, its inner reality and power, from view, while displaying its ‘flowers’, the external and visible reality.

Illuminations II: Childhood I is initially reminiscent of a Gauguin painting. Rimbaud’s memories of his own childhood seem to underly the exotic references. The mood is feminine, and one of tedium, a deep ennui accompanying others’ artificial pretences of love. Childhood II conjures up a picture of the moribund, and of absence and neglect, while the child is nonetheless immersed in magical and fabulous visions which cradle him. Childhood III, again conjures up the timeless world of the child. The cathedral represents inspiration perhaps, rather than religion; the lake, sadness. The bird and the white creatures may represent sexual arousal. The little carriage, with its stasis or action, is symbolic of the abandoned and emotionally deserted child, but also of his moments of joy. The troupe of little players are perhaps the child’s peers whose inner states are only glimpsed. The poem ends with a scene of rejection and hostility.

In Illuminations III: Tale, the Prince appears to be a representation of Rimbaud himself, and his attempt to transcend the ordinary state of existence. This negative version of himself in reality creates havoc, as Rimbaud seems to have done in his youth, and he questions here whether such a state of rebellion and destruction, mischievousness and cruelty, can produce any kind of spiritual alchemy. The Genie, the Spirit, then represents the positive aspect of the poet, and also Nature’s agent, the power of Life; and of Love, life’s essence. The negative and positive aspects combine to form the individual, living and dying with him. The Genie moreover is embodied, for the moment, in Verlaine, and the mutual ‘death’ the poet speaks of is also the fate of their mutually destructive relationship, which both have nonetheless survived, as one. Is there a reference here to the Genie, or Genius (the Latin term for the personal god, the inner spirit) who is a symbolic character in Jean de Meung’s continuation of The Romance of the Rose, representing the Spirit and agent of Nature working in the world, Nature’s enabler as regards the sexual urge in particular? Yet even the most complex and subtle of relationships falls short, says, Rimbaud of the heart’s desire, by which he implies human relationship, but equally the relationship of the poet to his art, and to his material life.

Illustrations IV: Parade presents a theatrical view of poets, writers, or perhaps just literary ‘entertainers’ in general. Their faces are masks, their expressions grimaces – the real self is another. Their finery, the tradition, appears faded, while Rimbaud himself, he claims, holds the key to this whole literary opera, in another words fully comprehends it and its failure, as he seeks to transcend it and discover the new.

Illustrations V: Antique may be a portrait and celebration of Rimbaud, or Verlaine, or simply of mankind, transported to ancient times when Cybele/Astarte/Aphrodite ruled, as in his earlier poem ‘Sun and Flesh’.

Illustrations VI: Being Beauteous (or, equally, Beauteous Being) is a paean to immortal Beauty, whom Rimbaud, the poet, seeks to defend against the hostile world. Beauty represents life countering death; colour against the blank of snowfall; and art set against the ‘mortal whistling and raucous music’ of the world.

Illustrations VII: Lives I transports us again to the exotic realms of Rimbaud’s youthful imagination, the terraces of the temple in the sacred land of poetry. He notes the treasured texts of the tradition, but also perceives what will follow, his own poetry that is, and though his insights are scorned the alternative is the ‘stupor’ engendered by merely retracing the old paths and guarding the old riches. In Lives II Rimbaud boasts of his poetic ability practised in a harsh, that is materialistic, country. His art feeds on his own past, his strict upbringing, his escape from it to Paris, and his wild behaviour, concerning which he has no regrets. His scepticism and disillusionment with western society is complete, but his intellectual rebellion appears futile, and he anticipates a sombre and embittered future. In Lives III he remembers the journeys of the imagination he indulged in when young, and his sexual awakening. But he has now relinquished his self-perceived ‘duty’ to literature. He is genuinely ‘beyond the grave’, the phrase perhaps recalling Chateaubriand’s ‘Memoirs from Beyond the Grave’, written, after Chateaubriand had ended his worldly career, in order to fill the hours that remained, being free now of all previous burdens.

Illustrations VIII: Departure follows on from the preceding poem. Rimbaud has seen, acknowledged, and now knows enough to choose to relinquish the past, and seek a new existence, involving a new search for love or simply affection, amongst the noise of materialism.

Illustrations IX: Royalty appears to be a straightforward celebration of his relationship with Verlaine, now declared publicly. The hangings and palm-trees may symbolise sexuality.

Illustrations X: To Reason (or a reason, a cause) is perhaps addressed to the rational scientific materialism of the future, to that force of progress which human beings now expect to deliver material benefits, cures for disease, and all they desire. Alternatively, the poem may be addressed to the new poets, including himself, or to whatever conquers Time, or whatever new movement or cause promises to do so.

Illustrations XI: Drunken Morning One interpretation is as follows. Rimbaud’s poems, he declares, are written against the backcloth of materialistic ‘progress’, its noise, its ‘fanfare’, and his poetry, his ‘poison’ (spoken ironically?) which he produces without faltering, will remain despite that fanfare. The ‘laughter of children’ would seem to denote his and Verlaine’s scorn of such materialism. The ‘mad’ promise offered by a combination of materialism, science, and colonialism, the promise of luxury and elegance, that is, achieved by means of technology and violence, also abolishes the old ‘tyranny’ of conventional virtue and sin, and leaves us beyond good and evil (in Nietzsche’s later phrasing). His and Verlaine’s homosexual affair should therefore be seen as pure, and ‘a riot of perfumes’ rather than as an object of others’ disgust. He and Verlaine are then ‘angels of ice and fire’, whose previous covert behaviour is now to be celebrated. Poetry, literature, has granted them a mask to present to the world, that literature which has been the glory of (and also excessively glorified?) the past. He believes in this ‘poison’ of his verse, and in his method of composition, and knows how to continuously distil his life into art. This then is the age of Assassins (those hashish-eaters, who were sent out to kill and destroy), the age of those who set out to erase the old world and its false morality, as he does through the ‘poison’ of his poetry which erases the old literary forms.

Illuminations XII: Sentences To whom are these phrases and sentences addressed? Verlaine? Poetry? The Muse? Any of these might be viewed as the ‘monstrous child’ his ‘companion’. Who are the ‘Daughters and Queens’? His poems? His dreams? His visions? Regardless, this text is a celebration of both love and poetry. Both are achieved through purity, clear-sightedness, loyalty; through memory, joy, laughter, and strength of will. How little the Muse, or Verlaine, or his poetry, care about his sufferings and methods! What matters is the poet’s ‘impossible’ voice, his creations, which are his only hope. Poetry is the ‘bell of rose-coloured fire’, tolling the death of the past, which is also the sunset of Romanticism, bringing on the dawn of Modernity. The solitary vision and the poet’s vigil, are contrasted with the ‘fraternal feast’.

Illuminations XIII: Workers appears to offer a stylised, almost surrealist, portrait of Verlaine and himself, or conceivably the Muse and himself. Note that ambiguities of poetic interpretation may co-exist, and both may be simultaneously true. The tiny fish left by the flood, are perhaps these ‘Illuminations’. The mood is of melancholy and ennui, the scene is stale full of ‘vile odours’; it is time to depart elsewhere!

Illuminations XIV: The Bridges is an imaginary scene, inspired by the bridges of the Seine perhaps, set against the grey skies of tedium. It is reminiscent of Baudelaire’s poem ‘Parisian Dream’, the starting point for many of Rimbaud’s visionary pictures. Are the bridges these ‘Illuminations’, bridges to the future poetry, or are they bridges to the literary past, a fading music of popular airs and public anthems? In either case a’ white ray’, of reality, time, disillusion annihilates this comedy (or commedia?). Rimbaud conjures up simultaneously hope and its negation.

Illuminations XV: City is again a Baudelairean perspective on the modern metropolis, its content akin to that writer’s poem Epilogue. Materialism is without artistic taste, devoid of subtle language or morals, a phantasmagoria of individuals leading brief antlike, meaningless lives. Rimbaud, in his small corner (a rural poetic setting to contrast with the materialistic urban one) is not immune from this, which penetrates his mind and heart, both filled with inner deathliness, desperation, and frustration.

Illuminations XVI: Ruts, gives us a magical view from the ‘window’ of his imagination. The procession of wagons is the train of these poems, full of visionary creatures and people, out of ancient myths and modern fairy-tales; some of the images joyful and magical, some dark and funereal.

Illuminations XVII: Cities (or, strictly, Towns) is a succession of theatrical, operatic pictures and scenes which correspond to Rimbaud’s ‘unknown music’ the product of his dreams, and his subconscious mind. We are close again to Surrealism; the collage of elements forming, in this case, a harmonious whole, in order to communicate a non-rational visionary state of mind, with the aim of dislocating the reader’s or listener’s habitual rational thought.

Illuminations XVIII: Vagabonds appears to be an invocation of his intense and later stormy relationship with Verlaine, relating to their various journeys and travels. A useful point of reference is Verlaine’s own autobiographical poem ‘Laeti et Errabunda’ (‘Happily Wandering’). Rimbaud once again looks back, nostalgically, perhaps regretfully, on his efforts to find the transformational alchemy which might render one a ‘primitive’, a ‘child of the sun’, free of civilisation’s restraints.

Illuminations XIX: Cities is again reminiscent of Baudelaire’s poem ‘Epilogue’. Here an authoritarian, hierarchical civilisation is conjured, perhaps an extended metaphor for a materialistic present, in which democracy is limited, and privilege reigns supreme. Rimbaud is developing and extending his use of pure description of imaginary constructs, to invoke a mood or ambience. His message, if any, is unclear, though the individual here appears diminished, and the collective and its mysteries dominant. Vagabonds and rebels are submerged, if they exist at all, beneath strange laws and the weight of commerce. The sunlight is only a semblance, the light is an artificial light, that created perhaps by science and progress

In Illuminations XX: Vigils I, we find Rimbaud facing what he perceives as the neutral reality. A rest which is neither fevered nor languishing, a friend who is neither burning with love nor enfeebled, a lover neither tormented nor tormenting, and around him open air and a world he never asked to be born into. Is this the sum total and truth of existence? His dream of a mysterious alchemy, of a higher destiny is cooling, as adolescence fades and adulthood looms. Is this the end of rebellion, and the beginning of a different duty: a duty to the harsh constraints of the human condition? The poem is a precursor to his renunciation of literature and his immersion in commerce, in a foreign land. In Vigils II, the author turns his face to the wall, to find in its markings and undulations the material on which to build dreams, and free the imagination once more. This is akin to Leonardo da Vinci’s notebook-comment about deriving inspiration from the random shapes and forms seen on a plastered surface. Vigils III gives us the poet in his room, adrift on the sea of imagination, and finding magical groves of imaginary trees into which peaceful and amorous thoughts float. Amélie may refer to the anonymous erotic text ‘Amélie ou les Écarts de ma Jeunesse: Amélie, or my youthful indiscretions’ published in 1798.

Illuminations XXI: Mystic, is a pictorial representation of human history, conflict on the left, progress (materialist?) on the right, and the heavens above and below.

Illuminations XXII: Dawn is another replay of Rimbaud’s youth, and his departure, on the road and by rail, for Paris. The precious stones are his poetry, the Goddess may equate to the Queen, and Sorceress, of Illuminations I: After the Flood, and signify Life or Nature, as well as Imagination, or the Muse. The poet lifts the Goddess’ veils, recalling the shrouded statue of Isis, or Neith who was sometimes equated with her, in the Egyptian city of Sais, mentioned by Plutarch. The statue bore an inscription saying ‘I am all that has been, and is, and shall be; and no mortal has ever lifted my veil.’ This motif of the veiled goddess is common to many mythologies, indicating the concealed truth of existence. Rimbaud chases after the truth, glimpses it in dream or imagination, but then awakes. The implication of the poem is that the dawn light of youthful imagination fails and fades, and is replaced by the harsh and glaring light of noon reality.

In Illuminations XXIII: Flowers, the ‘flowers’ are perhaps his poems, these ‘Illuminations’ which are the products of his imagination, and which inspiration delivers to the hard and cold marble terraces of the material world.

Illuminations XXIV: Mundane Nocturne, suggests an initial picture of the poet at night staring into the coals of a fire. The imagined coach is the vehicle of his art, outdated perhaps, a product of sleep and dream, a minor dwelling, in which the poet is isolated from the world, a coach that follows a road already abandoned by materialism, and from which an occasional glimpse of the Goddess, Nature, Life, the Muse is visible through its flawed window. When the dream ceases, dispelled in a breath, the world is a patch of gravel, while the poet is left, subject to the vicissitudes of reality, yearning for a renewal of the dream state.

Illuminations XXV: Marine is written in vers-libre, free verse where the phrase is the basic unit, rather than in plain poetic prose. The scene conjured is one of retreat and departure; the metallic chariot, symbolic of his relinquishment of literature, ploughs up the remains of the poet’s thorny past, and conveys him towards the east, and the dawn light.

Illuminations XXVI: Winter Feast, again suggests that the flood, the cascade, will carry the poet away from the comic-opera, the theatre of words, though these ‘Illuminations’ temporarily provide a gaudy show which prolongs the worn-out poetic and artistic display with its various historical styles, and movements, these symbolised by incarnations of the Muse, from Horace’s Latin ‘Odes’, to the eighteenth-century artificial Rococo world of the painter Boucher, known for his idyllic and voluptuous paintings.

Illuminations XXVII: Anguish, a key poem, asks whether the mysterious She, who perhaps is identical to the Goddess and Sorceress of previous poems, symbolising Life or Nature, as well as Imagination, or the Muse, will bring him some kind of peace and redemption. He addresses himself, here both demon and deity, representing the depths and heights of the human; the poet seeking Love and Vigour, greater than all other forms of glory. Will his attempted alchemy of the word and his companionship with Verlaine achieve the primal freedom he desires? The Goddess, the Sorceress, Life, is also a Vampire feeding on us, driving us on to create the new, or be condemned to what it left to us by the past, and so inflicting the existential torment that we experience. Here Rimbaud forgoes much of his pictorial ability to focus on the human condition, and sets the scene for ‘Une Saison en enfer’, which he may well have been writing at about this point in the sequence, before his completion and final revision of the ‘Illuminations’.

Illuminations XXVIII: Metropolitan, displays all Rimbaud’s considerable pictorial skills once more, to remind us of what is left to us by the past, that which the Vampire, Life, drives us to accept or attempt to transcend. Here are, in order: ‘the city’ (civilisation), ‘the battle’ (our efforts to transcend), ‘the countryside’ with all its phantasmagoria of natural life, ‘the human drama’ (communal life, the arts, social interactions) and ultimately ‘the sky’ (that which is beyond us), and our own innate intellectual and physical ‘Vigour’, symbolised by the sun that grants us the strength to wrestle with Her, Life.

Accordingly, Illuminations XXIX: Barbarian appears to celebrate the poet’s current state. Rimbaud portrays himself as a barbarian, as he does in ‘Une Saison en enfer’, one who challenges the existing view of civilisation, his youthful season finished, yet still waving the banner of art, amid the battle to achieve the non-existent victories of the mind, symbolised as cold arctic flowers; still employing, that is, his ecstatic imagination to create fires amid the rain, poems from diamonds, his words hurled from the burning heart of the self, and doing so while isolated from the previous forms of poetry, the old retreats and flames. Equally, one might offer an erotic interpretation, focussed on the ecstasies of his relationship with Verlaine, both intellectual and sexual, after the loveless aspects of his childhood and early youth.

Illuminations XXX: Promontory displays, in a near-Surrealist manner, modern civilisation as a rich phantasmagoria, which tolerates art as mere entertainment, the arts that is of the past or their imitations symbolised as ‘faint eruptions, crevasses of flowers, and glacial water’. The poet is left to anchor his wandering vessel opposite this fantastic exhibition of modern ‘marvels’, which travellers and the wealthy embellish with fresh flourishes of fashion.

Illuminations XXXI: Scenes, gives us another deeper pictorial view of the social comedy, played out in the materialistic theatre of the present, in much the same way as it was in the ancient amphitheatre of history. The symbolism is vague, but suggests the re-invoking of the known rather than any achievement of the new. The title ‘Illuminations’ here invokes the bright glitter of civilisation that hides a tawdrier truth.

Illuminations XXXII: Historic Evening completes the rising crescendo, with an apocalyptic vision. The poet turns away from the ‘economic horrors’, described in the previous poem, and envisages the ‘bourgeois’ world, and its inhabitants, being swept away, in accord with the ancient prophecies. Note that the language used in the poem is itself calm and quiet rather than exaggerated. Rimbaud’s art is almost emotionless by this point.

Illuminations XXXIII: Movement, his second poem in vers-libre, describes the onward march of scientific progress and exploration from which the ‘young couple in the ark’, that is Rimbaud and Verlaine in their poetic retreat, hold aloof, while continuing to write, and guard the sacred world of the intellect and the passions. This, and the following two poems turn the poetic flow towards their relationship.

The title of Illuminations XXXIV: Bottom refers to the character in Shakespeare’s play ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, turned by magic into an amorous ass, in love with the faery-queen Titania. Rimbaud is a parallel case, made foolish by his poetic aims, while at the same time deeply involved with Verlaine. There is perhaps also a reference to Apuleius’ ‘The Golden Ass’ where a like transformation is only undone by the powers of the Goddess, in Apuleius’ case the goddess Isis.

The title of Illuminations XXXV: H refers presumably to the Hortense of the poem. The female name is derived from the Latin hortus, a garden, and may signify Nature, or simply primitive Life and human sexuality, open to even infants and the poor, and potentially a place of health and healing. Like Love, Nature is beyond good and evil, devoid of intrinsic morality. This is the state that Rimbaud seems to desire, or at least invoke, in his relationship with Verlaine.

Illuminations XXXVI: Prayer initiates the closing sequence of the work. Its form perhaps derives from Villon’s poetry, his ‘testaments’ listing the recipients and purpose of his prayers, rather than his heirs and what he leaves to them. The names of the religious Sisters, Louise Vanaen (Norwegian vanaeren, disgraced or shamed?) of Voringhem (a fictitious place, Norwegian for Spring-home?) and Léonie Aubois (the lioness in the wood?) of Ashby (in England, mentioned notably in Walter Scott’s novel ‘Ivanhoe’) are presumably inventions. The point is rather to offer a prayer for the shipwrecked; that is for himself, and equally for the pair of ‘children’, Verlaine and himself. The prayer is also addressed to Lulu (from Sumerian lilu, a male demon: Verlaine?) offered on behalf of men (‘Les Amies’ was a set of six sonnets by Verlaine, published in 1867, celebrating Lesbianism, as a cover for homosexuality), and to the anonymous Madame *** of the first poem of ‘Illuminations’, who may again be an alternative version of Verlaine. He then continues his prayers, addressed to his adolescent self, to the saintly aspect of Verlaine and his poetic mission, to the spirit of the poor, and to conventional religion tailored as it is to the demands of the moment. His last prayer is to Circeto (derived from Circe, the Sorceress of Homer’s Odyssey, perhaps also from the Latin circare ‘to wander’?) who presides over the icy heights of modernity on which he writes his ‘daring’ poems of every kind, even metaphysical, amidst the polar darkness and cold. But after this last prayer, he declares, there will be no more. He resigns himself to material existence.

Illuminations XXXVII: Democracy displays colonialism in action, furthered in pursuit of material progress.

In Illuminations XXXVIII: Fairy, the homosexual poet, in his feminine aspect as Helen, conjures antiquity again, contrasting it with the destructiveness of progress, that ‘murmur of the torrent below the ruined woods’, while Illuminations XXXIX: War describes his emergence from a confused childhood and adolescence, to an exact poetic mission, a war against that progress which destroys the essential purpose of life.

Illuminations LX: Genie, returns us to the material of Illuminations III, where the Genie represents the poet in his positive aspect, as his other self, the self of inspiration, and therefore also represents the earthly power of creative Life and Love. In the former poem the Genie is, ultimately, identical with that Prince who represents the destructive and negative self, since both combine to form the individual.

Life is both present and future, the past being dead. The power of Life and Love, the Genie, is the force to which we ultimately must surrender, the power that sweeps away the past. Some of the attributes of the force of Life and Love evoked here are also aspects of Christian love, and its embodiment in the figure of the loving Christ, to whom Rimbaud appears to remain loyal, although the Christian cycle of divine incarnation and human redemption is finished. The Genie is also evocative of the powerful deities of previous epochs, for example of the Hindu religion, and also of archaic and primitive beliefs generally.

Here, then, is Rimbaud’s hymn to Life and Love, and the finest expression in the ‘Illuminations’ of his yearning for the greater more intense powers that we might seek to follow, and which in turn would inspire us more deeply. Poems III and XL are thus strategically placed to tie together the whole ‘Illuminations’ as a revelation of that longing, the poems between the two expressing both the journey of the poet, and his resistance to the merely material world.

Illuminations XLI: Youth is a recap of the insights gained from that journey towards his twenty-year old self. Youth I is Rimbaud returning his poetic efforts, as he descends from such dreams, to memory and rhythm, the primary ingredients for this prose-poetry of his. Images of reality surround him, and he too must be a worker. Youth II reveals that the delights of early inspiration and of the flesh are now over, that his youthful impatient manifesto has been fulfilled to the extent that it could be, and he is left with the remains of the intellectual dance, his poetic voice, as its legacy. Youth III weighs up his nigh-on twenty-year old self. He is done with the poetical tradition; his physical yearnings now consummated seem stale. He looks back, resignedly, on his adolescent egotism and arrogance. The melodies are now nocturnal, the days of his youth are done with. Youth IV, though, shows him still tempted by those first aspirations. The inspiration is weaker, but he will set himself again to his work, the editing and completion of these ‘Illuminations’, and perhaps the preparation for the next phase of his life, which will be a self-transformation, such that his old world of France and poetry will be no more, and his new world will possess a different aspect, ultimately North Africa and the material life.

Illuminations XLII: Sale, completes the poetic sequence. Rimbaud offers for sale the riches of the ‘Illuminations’ themselves, these diamonds of his intellect and his poetic sensibility, none of which were previously available. He implies that commerce is the only thing that the material world truly understands. He therefore presents his poems, ironically, as objects of trade. He claims they represent a freeing, a derangement of the senses, such as he originally desired, and that they will exist for sale for a long time to come, and he displays their attributes and effects as the poetic equivalent of technology and progress. This is the challenge left for the mature Rimbaud, to accept modernity on its terms, and yet in the same breath to defy it on one’s own terms.

In summary, it is possible, I suggest, to view the ‘Illuminations’ not as a collection of unconnected poems, of disparate elements merely thrown together, but as a carefully arranged and edited sequence, the underlying themes of which are: firstly, his resistance to the material, bourgeois and colonialist world of commerce, science, technology and material ‘progress’ and his desire to transcend it; secondly, the youthful journey of the poet from arrogance to a degree of resignation, from rebellion against his childhood constraints to an ironic and sceptical concession to material reality; and, thirdly, the ultimate power of Life and Love to which the Self must submit, yet which are also its inspiration and its means of fulfilment.

Far from being the outpourings of a mind still trapped in adolescence, Rimbaud’s work may then be seen as remarkably mature and assured, emotionally and intellectually astute. Equally, absorbing his work has its dangers, as with all ‘existentialist’ literature, since it risks generating extreme negativity, and a self-destructive view of life, in the reader or listener. Human civilisation is a more subtle and complex process than Rimbaud appears to credit it with being. Extremist rebellion over-simplifies that complexity, and there is a certain blindness in Rimbaud, a persistent arrogance in his social and philosophical analysis, in line with the more unpleasant aspects of his personality, as reported by his contemporaries, a blindness and arrogance with origins no doubt in his difficult childhood, and accompanied by the rebellious, antagonistic emotions it generated within him.

An acceptance and understanding of the nature of the intentionless, undesigned universe, involving both order and chaos, and of human society as a construct both aspirational and flawed, does not demand that we ignore the existential emotions produced in us by our random place in that universe, or the yearning for something deeper from life. The acceptance of truth and the emotions generated co-exist. Broad labels such as ‘bourgeois’ and ‘materialist’ seem outdated. Science itself has altered our view of matter, time and space, in favour of form and process, flow and dynamic interaction. Our response in necessarily complex.

Acknowledgement of the human condition is both an acceptance of life, and a questioning of it. Love, and beauty may co-exist with essential truth. Science and technology may prove positive tools, not merely negative threats. Trade and commerce may become agents of peace rather than colonialism and stultification. Poetry and literature survive and continue, because there is always a need to express our situation. In Rimbaud’s case, as in others, precocious ability does not confer infallible wisdom. Permanent rebellion is not, in the end, a viable mode of existence, though moments of personal rebellion are crucial in expressing resistance to petrifaction or injustice, and as a call to fresh human inspiration.

Rimbaud recognises this to some degree in the ‘Illuminations’. His relinquishment of literature was partly due to his exhaustion of his major themes, but, more essentially, was due to his personal and pressing need to find another mode of existence, in order to save himself from self-destruction. It was that need to resolve his inner problems (and here a deeper consideration of his childhood, and his psychology is helpful) which led to his silence, his immersion in distant territories, in trade and commerce, in primitive, or simply different, cultures. But that silence should not be seen, judgementally, as rendering his life a failure. Life can only be judged by the standards of life, not that of literature. Were it not for the medical condition that prematurely brought his life to an end, Rimbaud might well have been, and remained, satisfied with his mature role, his ‘new’ life. As a poet, the ‘Illuminations’ show his literary brilliance, but also that a life in literature ultimately proved insufficient to satisfy his inner needs.

IV: ‘Une Saison en enfer’ (1873)

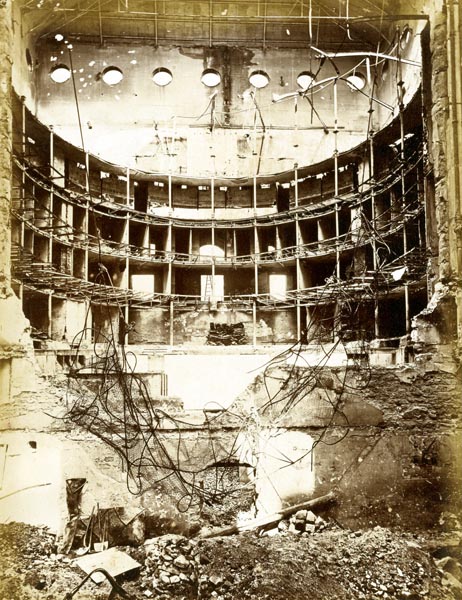

‘Le Theatre Lyrique Incendié’

Alphonse J. Liebert, photographer (French, 1827 - 1913)

Getty Open Content Images

During the creation of the ‘Illuminations’, and before their final editing and publication, Rimbaud wrote and published ‘Une Saison en enfer’. In the latter work he turns from the predominantly pictorial, imagistic, and symbolic prose-poems of the former, to a harsher prose which gains in intensity what it loses in charm, its content amounting to a history, the ‘tale’ of himself. It is an extended soliloquy on-stage, a session in the confessional booth expressed in direct autobiographical terms, sarcastic and often ironic, with a bitter tone, yet still with theatrical literary flourishes, as he attempts to convey his attitudes, emotions, and state of mind. It is a work of self-presentation, and also a poem of farewell, a farewell to his past life and to literature, to the ‘theatre of words’, before his plunge into the silence of material existence. It therefore feels as if the publication of the work should have followed the ‘Illuminations’ rather than punctuating them, and it is helpful to consider it as his last creative effort in poetry, regardless of the circumstances surrounding the publication of both works.

We begin with Rimbaud’s Prologue. He introduces the sequence by recalling his childhood, his rebellion and escape from provincial life, his early poetry, and his first arrival in Paris involving Verlaine, where he ‘played some fine tricks on madness’. His appetite for this new life exhausted, he had turned to poetry again in the ‘Illuminations’, seeking the ‘key to the old feast’, the key to renewed poetic vigour and fresh inspiration, as well as existence itself. ‘Charity’ (charitas in Saint Paul’s sense of Love, but also charity towards himself?) is that key, the practising of which he views sceptically as an illusion, merely an aspect of his solitary ‘dreaming’. He now condemns his former actions, and is scornful of his own character and personality. He is a ‘hyena’, feasting on the scraps of kills, a sinful spirit, a creature of appetite, practising a form of egotism and self-interest rather than relationship with others. Mockingly, he addresses Satan (Baudelaire’s Satan, who is a symbol rather than a reality, a token of deathliness of spirit, and destructive tendencies), to whom he dedicates this series of prose-poems, these ‘delightful poppies’ (the adornment, in Greek mythology, of the god of death, Thanatos, and his twin brother Hypnos, the god of sleep, whose son was Morpheus, the god of dreaming). His confession then is addressed to his demons, to Satan as the spirit of self-destruction and negativity. Note that a childhood allegiance to the symbols of Christianity, akin to Baudelaire’s, continues to fuel his symbolism, despite the perceived failure of conventional religion.

In ‘Bad Blood’, Rimbaud starts by attributing to himself all the vices inherited from his Gallic ancestors, including an innate idleness. He has survived nonetheless in his idleness, like all the heirs of the Revolution, though he himself is without forerunners in his mode of rebellion. He classes himself amongst ‘the inferior race’ whose rebellions are for their own gain not for any higher aim. His only memories are of a solitary Christian childhood, in provincial France, and he can only imagine himself in history in any one of a number of lone roles, a vagabond, a mercenary, a leper, but never among the upper echelons of his times, nor in the councils of conventional religion. Paradoxically, he portrays himself as an outsider within his native society, who can only locate himself in actuality, that is in the present day not the past.

Following the Revolution and the assertion of the Rights of Man, the inferior race, he claims, has spread everywhere, the people and reason, ‘the nation and science’, and such lone roles as his have almost vanished. Through science, the ‘new nobility’, the people pursue material progress, and, irony of ironies, think to advance towards the spiritual through the material, towards the qualitative by means of the quantitative. He is a pagan though, and spiritual grace is absent; the gospel teachings lie in the past, though he himself yearns still for revelation, and waits ‘for God, with greed’.

He intends to quit Europe, to become one of the true colonialists, of whom he gives a wholly condemnatory portrait. Then, on his return, he will be seen as a member of contemporary society, involved in trade and politics, and therefore ‘saved’. All this is said with a degree of sarcasm, rather than irony; to a large extent he means what he says, the tone is more bitter than humorous. Nonetheless, despite his intentions, he remains in France, and fails to leave. He despises his own character and actions, and exhorts himself to depart, to embrace ‘a hard life, pure brutalisation’. He envisages it as a form of death, conjuring up an image derived perhaps from the final paragraph of Chateaubriand’s ‘Memoirs d’outre tombe’ (first published 1859/60), of opening the coffin lid, and seating himself ready for eternity. He feels so forsaken he is ready to offer himself and his yearning for perfection to any religion, located as he is deep in Hell.

He next imagines himself in another lone role, as a convict, wandering through France, an image perhaps derived from Jean Valjean, the convict in Hugo’s ‘Les Miserables’ (first published 1862), mirroring his own escape from Charleville to Paris, and his travels on the road. He sees himself beyond his society and the law, or rather before it, a primitive, a ‘brute’. Nonetheless he considers he can be saved, and is about to depart to Egypt, the land of Ham in the Bible. He considers he knows neither nature nor himself, and intends to embrace silence: ‘no more words.’ He will be a primitive among the primitives. He will escape the torments of civilisation, renouncing his vices. Other choices seem impossible, and, in the end, he must choose divine Love rather than earthly love, and feels that he has been chosen for salvation, of a kind.

He will live on, silently, and praise God in doing so. If this is Rimbaud’s return to faith, it is scarcely a return to conventional religion, and the figure of Divine Love may or may not be a representation of Christ the Redeemer. He wishes to lay down the burden of his previous life, its tedium and its vices. He demands freedom and work, rather than happiness, even if that is a form of death. Not only in the theatre of words, in reality also, ‘life is the farce all perform’. An end to talking then; Rimbaud finally in this section of the work sets himself to silence and labour, the ‘path of honour’. Renunciation of the intolerable, and acceptance of a means of salvation is his personal solution to his predicament.

Rimbaud is here the archetypal superfluous man of the previous century, a hero of modern times out of Lermontov, a victim of his own ‘sensitivity’ and intellectual penetration, condemned to tedium and disillusionment….and yet. The depth of his hatred of modern civilised existence is immeasurable, even if it is unclear what the source of that powerful hatred is, stemming we may assume from childhood experiences, but enhanced by maturity. His may often seem an intellectual, spiritual and emotional rebellion without sufficient reason, a prolonged adolescent howl of scorn, absent the ‘wisdom’ of maturity, yet it continues to resonate, since within his howl of rejection, and self-loathing, lies a genuine critique of the modern world, with its intellectually barren creeds, its overt materialism, and its pursuit of progress, of science and technology, without due regard to the moral and spiritual life of human beings.

Ultimately, he yearns for the extremes, for inspiration, exaltation, a relief from the tedium of the human condition, for a mysterious power of Love transcending reality. All this is symptomatic of the death of the gods, in an age where the majority have even now not understood that death, as Nietzsche rightly claimed, nor as yet created a wholly secular society of equivalent spiritual depth. Such a society would need to founded on a more subtle and dynamic comprehension of morality than previously, and embody self-created purpose, in an intentionless universe. Rimbaud is therefore a primary witness, following on from Baudelaire, to the intellectually empty nature of contemporary religion, monarchy, and imperialism, and the moribund forms of the poetic and artistic tradition, and to the stifling nature of the mundane, bourgeois, materialist and colonialist world of trade and commerce accompanied by war for the purpose of gain, which dominated his society. He is a witness who, though predisposed to being such by his childhood and background, nonetheless can testify to the reality of that intellectual demolition of the past, and to the angst it brings to many. His answer is in one sense merely nihilistic, yet in another a necessary clearing of the path to the future, where a more sober and tenacious awareness might lead human beings to accept the reality of their condition in a deeper existential way. They might then summon up the energy to create their own individual purposes in the world beyond the self, a world which is intrinsically purposeless, but in which mind can, and is obliged to, creates purpose.

‘Night in Hell’ (or ‘Hellish Night’) begins with a portrait of the poet in spiritual hell, having achieved only a glimpse of salvation, of spiritual heaven. He laments his Christian background, without which, in the absence of the concept of hell, he would be immune to such visions, like a true pagan. The promise of poetry, of an alchemy of words, was an illusion. He views himself as stupid, and as an object of pity, while his voice is unheard by others, that world of indifferent phantoms. He is beset by hallucinations, and a disbeliever in all that materialistic society believes in, its traditions and its principles.

He again summons elements from his Christian childhood and youth, those of Satan (Ferdinand was a name employed in the Ardennes for the Devil) running wild, as he, Rimbaud did, sowing his wild oats, and of Jesus behaving in miraculous manner. He, the poet, will reveal all the mysteries of being and nothingness, since he is a master of phantasmagoria. He claims, egotistically yet sarcastically, that he possesses all the talents, can entertain in every way, deploying magic and alchemy, and asks only that people have faith in him. He will now ‘make all the grimaces’ within these prose poems, though he regrets that poetry is no longer his sanctuary, his domain, his ‘chateau’, his imaginary castle in Saxony, the easeful bank of willows in his early poem ‘Memory’. Although he has suffered, he considers himself fortunate not to have suffered more. Nonetheless, he feels as if her were dead, ‘beyond the world’, and yearns to be returned to life, even to the deformities of vice, the poison of earthly love, ‘that kiss a thousand times damned’, which is also perhaps the Judas kiss of betrayal. He asks his God, who may here equate to Satan, for pity. He is revealing himself and his love to the world, while plunged in his hell, which is the unseen mind. Love, I think, and specifically homosexual love, is here the fire that flames upwards, containing his ‘damned’ soul, a remembrance perhaps of the spirits as they appear to Dante in the flames of Canto 26 of the Inferno, but with a hint also of the ‘concealing flame’ which hides Arnaut Daniel the poet, in Purgatorio 26. Rimbaud will now speak of that love, in the next section.

Ravings I – Foolish Virgin, the Infernal Spouse grants us a portrait of Verlaine as the ‘foolish virgin’, and Rimbaud as the ‘infernal spouse’. It is voiced by his fictional Verlaine in the form of an invented confession, or rather complaint, after the fashion of the classical and medieval plaints, a confession in which Rimbaud mocks his ‘companion in hell’ portraying his moaning and whining, and parodying his religious leanings. Verlaine within the plaint, meanwhile, portrays Rimbaud as a young Demon, crediting Rimbaud in turn with speech which reflect the latter’s savagery, disdain, and wild behaviour. This portrait of Rimbaud, attributed to Verlaine, is then further developed, thus becoming Rimbaud’s own self-portrait, a portrait of one who seeks ‘to evade reality’ and might prove ‘a danger to society’. We therefore see Rimbaud, as author, innovatively portraying and analysing himself as a character seen through the theatrical mirror of Verlaine’s monologue, while likewise displaying a mock-Verlaine.

Verlaine is portrayed as the one who loves, Rimbaud as the one who is loved, who proves an indifferent, tormentor of the former. The torment only deepens Verlaine’s love, who envisages them as ‘two good children’, as reflected in Verlaine’s own poetry, for example in ‘Is it not so?...’ and ‘You see we need…’, many of his poems, seemingly addressed to a female lover, being intended for Rimbaud; while clearly Rimbaud judged himself the dominant and colder partner in the relationship.

Within the text here, Verlaine identifies Rimbaud as one who seeks ‘secrets’ which will ‘transform life’, and whom he credits with possessing ‘magical powers’, one who had ‘days when all human activity seemed to him a plaything of grotesque delirium.’ Verlaine’s admiration is nonetheless clearly apparent, since though the relationship was stormy, and difficult for him, it both stimulated him, and inspired him poetically as his own verse shows. Rimbaud’s final sarcastic comment to this section is: ‘A strange ménage!’ As complex a relationship, in other words, on both sides, as any. As in their respective poetry, Rimbaud is harder and more self-contained, betraying some of the less pleasant aspects of his character and personality, shaped as he was by his childhood. Verlaine exhibits the revealing sweetness and humility which grants endless charm to his works, at least until near the chaotic, deeply religious close of his life, works which exemplify the tender and loving quality of the man, a quality which Rimbaud may have exploited, while equally perhaps considering himself exploited. An archetypal love-hate relationship, in fact; a bond which both ultimately severed.

Rimbaud shows a depth of self-awareness in this section, conscious, I think, of his inability to alter himself or his behaviour. Both the permanent rebelliousness shown in his life and art, and his inability to love deeply, or at least in the way Verlaine wished, may be traced to that upbringing of his, absent the father, by an effectively-single mother of strict and narrow views, an upbringing which polarised his thoughts early on, and from whose constraints he felt the intense need to free himself. He proves self-aware enough to display his failings, but not, I think, to fully address them. Unable to rid himself of his adolescent dreams and his desire for both freedom and transformative love, in life and art, he ultimately chose to forsake both his adolescent views and literary endeavour, and embrace a different reality, perhaps successfully, perhaps not.