Jean de Meung

The Romance of the Rose (Le Roman de la Rose)

The Continuation

Part XII: Chapter CV-CIX - The Lover Wins The Rose

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter CV: Venus re-launches the assault.

- Chapter CVI: The tale of Pygmalion.

- Chapter CVII: Pygmalion weds the statue.

- Chapter CVII: Pygmalion’s prayer to the gods is answered.

- Chapter CVIII: The castle is taken.

- Chapter CVIII: The Lover sets out to win the Rose.

- Chapter CVIII: The Lover on rich old women.

- Chapter CVIII: The Lover reaches the sanctuary.

- Chapter CVIII: The Lover arrives at the rosebush.

- Chapter CIX: The Lover wins the Rose.

Chapter CV: Venus re-launches the assault

(Lines 21429-21590)

Venus gathered up her dress,

The better the air to address,

And went full swiftly thither,

Yet the castle did not enter.

VENUS, prepared for the assault,

First called out to the foe to halt

Their vain defence and surrender.

Shame it was that gave their answer:

‘Indeed Venus, this means nothing;

For you’ll ne’er set a foot within,

Not if twere I alone were here,’

Said Shame, ‘for I know no fear.’

The goddess, hearing her reply,

‘You slut, what purpose,’ she did cry,

‘Is served by your resisting so?

All this we soon shall overthrow

If the castle’s not surrendered;

By you twill never be defended.

Defend it against us, indeed!

You will surrender it, at speed,

Or I shall burn you all alive,

Every wretch that doth so strive.

For I’ll set the whole place alight,

Raze the tower, and turrets, quite.

I’ll warm your backside and burn

Pillars, posts, and walls in turn.

Your moat will be piled sky high,

With their wreckage, thus say I;

However strong you choose to build,

Down they come, the moat is filled.

And Fair-Welcome will then allow

All whom he welcomes with a bow

To take the Rosebuds and the Roses,

Gifts, or by sale, that wall encloses.

No matter how proud you may be,

You’ll all strike your flag readily.

Then folk may go, and in procession,

For I shall brook no exception,

Among the bushes, midst the roses,

When I throw ope what it encloses.

To overcome vile Jealousy,

I shall make the meadows free,

Lay the fields and pastures low,

I shall enlarge the pathways so,

And all then may gather freely

Buds and Roses; lay and clergy,

Religious folk, and secular,

None shall circumvent the matter,

All shall come in penitence,

Though you may find this difference;

That some folk will come secretly,

While others come quite openly;

And those who come in secret will

Be yet considered fine men still,

While the others will be defamed,

As wretched whoremongers claimed,

Though indeed their fault is smaller,

Than those who scorn their accuser.

But yet, tis true, there is the sinner

(And may the Lord, and Saint Peter,

Confound him, may he be cursed!)

Who shuns the Roses, turns to worse;

He’ll be pricked hard, and the devils,

Shall grant him a crown of nettles;

For Genius, who spoke for Nature,

He has sentenced each vile creature,

For his base proclivities,

With all our other enemies.

Shame, if I could not trick your heart,

Little I’d prize my bow, my art,

Indeed, I could blame no other;

For I’ll never love your mother,

Reason, nor can I love you ever;

She’s bitter towards the Lover.

Who lists to your mother or you,

Will never know a love that’s true.’

This speech fulfilled Venus’ intent,

What she’d said was all-sufficient.

She drew herself to her full height,

Like a woman ready for a fight.

She drew her bow, notched her dart,

And then she exercised her art,

Bringing the bowstring to her ear,

The bow no longer than a mere

Six feet, and aimed, that fine archer,

Towards a narrow aperture,

Half-concealed, which she espied

At the front, not round the side,

Of the tower, where cunning Nature

Had placed it between two pillars.

These pillars, made of ivory,

In place of a reliquary

Supported a silver statue,

Not too short or tall, nor too

Wide or thin, but of a measure

In the body, hand, arm, shoulder,

Neither too little nor too much,

But perfect in its form, as such,

The other parts as fine or finer,

And, more fragrant then pomander,

Within there was a sanctuary,

Covered by precious drapery,

The finest cloth and most noble

Twixt there and Constantinople.

There was no equal on any tower;

Greater than Medusa’s power,

It performed wonders profuse

Though put to far better use.

Gainst Medusa none might survive

For they were turned to rock, alive.

Twas her gaze, ill she did there,

With her evil, snake-filled hair;

For all who looked towards her

Had no sure defence against her,

Except for Jove’s son, Perseus,

Who made this Medusa yield,

By gazing at her in the shield

That Pallas his sister gave him;

And thus that same shield saved him.

By its means, the Gorgon’s head,

He took and kept, once she was dead.

He held it close, and used it well,

In many a conflict that befell;

Many a foe he changed to stone,

Or slew them with his sword alone.

The head he gazed at in the shield;

Else to stone he’d have congealed,

Remained a rock there, in that place,

Merely from looking on her face;

Using his shield, but as a mirror,

So great was the Gorgon’s power.

But the statue that I tell you of

Has greater virtue, for thereof

No death comes, for it kills none,

Nor turns to stone a single one,

Rather from rock doth transform them,

And propagates the form of them,

Finer, in truth, than twas before,

Or others could indeed restore.

One works hurt, the other profit,

One kills, the other revives it.

One causes harm, with its fell charm,

The other doth remove the harm,

Since those who were stone before

Or in their senses wounded sore,

If they are brought near the latter

Though it looks on stony matter,

They will be changed from stone,

And their right senses they will own,

And be protected forever,

From every evil and danger.

If I could, if God might help me,

I would approach it more closely,

And touch that form which I revere,

If any may approach so near.

For it is worthy, and virtuous,

And in its beauty it is precious.

And if, by use of one’s reason,

One would make comparison

Twixt this image and the other,

One could say that it was greater

Than that carved by Pygmalion;

As a mouse must yield to a lion.

Chapter CVI: The tale of Pygmalion

(Lines 21591-21692)

Of that statue the tale’s begun,

That was carved by Pygmalion.

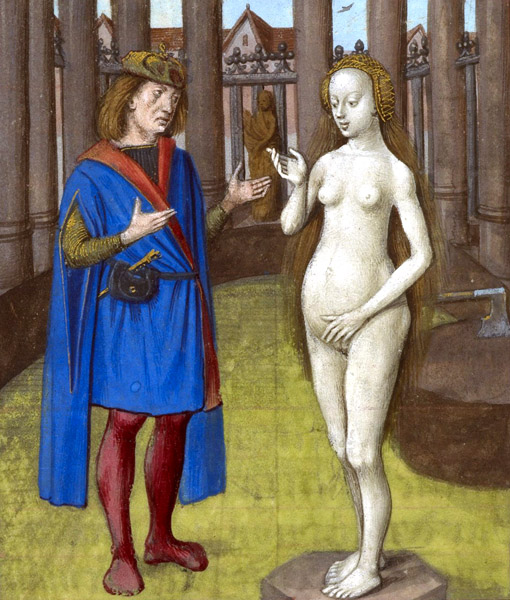

‘Pygmalion and the statue’

PYGMALION, he was a sculptor,

Who worked in hardwood and other

Things suited to the craft, like stone,

And metal too, and wax, and bone,

And all materials that proved fine

To carry out some grand design.

(No better artist could be found

To carve a work of great renown)

A statue he would make would he,

An image carved of ivory,

And gave his work such attention

So executed his intention,

So wrought this work, of his conceiving,

It proved so noble and so pleasing,

It seemed, that form he did contrive,

Fair as the fairest, and alive.

Not Helen, nor Lavinia,

Her complexion could come near,

Nor were born to be as lovely,

Nor owned a tenth of her beauty.

He was amazed, Pygmalion,

When he himself looked thereon.

And, all unwary of the threat,

Love now enmeshed him in his net,

So strongly, he found scant relief;

He grieved, but could not stem his grief.

‘Alas,’ he said, ‘do I wake or sleep?

Many a statue I’ve made; but weep,

And fall in love with them? Never!

Some are beyond price, moreover,

Yet I’m conquered by this fair one,

And she’s robbed me of all reason.

How did this love seize me, though?

Alas, what captured my thoughts so?

Though deaf and mute I love but her;

A statue, she’ll not move or stir,

Nor ever yet grant me mercy;

How did such a love come to be?

There is not one could give an ear

And yet not be dumbfounded here

By, of all fools, the greatest one

In all the world. What’s to be done?

I’faith, if I loved fair royalty,

I might still have hope of mercy,

For such a thing is possible.

But this love is unthinkable,

It arises not from Nature,

But some malaise in the creature;

Nature finds an ill son in me,

She shamed herself in making me.

Yet if I would love so foolishly

Tis not her I should blame; on me

The blame should fall, anon.

Since I was named Pygmalion,

And could walk on my own two feet

With such a love I ne’er did meet.

Yet I love not so foolishly,

For if the tales lie not, many

Have, indeed, proved more foolish still.

Did not Narcissus drink his fill

Of his own face, in the fountain

Neath the branches, gazed again,

Sated his thirst in the pure water?

Did he not lose himself, thereafter?

Then he died, so goes the story,

Yet lives on in the memory.

So I am not so great a fool,

For when I wish to love this jewel,

I can go hold her, clasp her, kiss,

And ease my misery through this.

Narcissus, he could ne’er possess

What he viewed, while scant success

Men have won, in many a country,

In loving many a fair lady.

They served them as best they might,

And yet none would their love requite,

Though they performed to the letter.

Has not Amor served me better?

No for those lovers, howe’er unsure,

Possessed the hope of winning more,

To be kissed, some other favour,

But I lack hope that I shall savour

Such joy as they anticipate

Who the delights of love await.

When, to comfort myself, I wish

To clasp her, and embrace, and kiss,

I find my love is as rigid

As a post, and just as frigid,

My mouth a frozen orifice,

When I touch there so as to kiss.

Ah, I have spoken too coarsely,

Sweet friend, I beg your mercy,

And beg you to accept amends,

For inasmuch as your gaze extends

To me, and you do smile sweetly,

That, I think, should suffice me;

A tender regard, a sweet smile,

Delight the lover and beguile.’

Chapter CVII: Pygmalion weds the statue

(Lines 21693-22048)

How Pygmalion asks his friend

For pardon, seeking to amend

The words he used which did seem

Wrong and foolish in the extreme.

THEN Pygmalion knelt, his face

Wet with tears, and sought to place

A pledge, in her hand, as amends,

But she cared naught for his ends.

For she felt and understood naught

Of him, nor of whate’er he sought,

So that he felt his efforts vain,

That love for this thing brought but pain.

He knew not how to regain his heart,

Reft of wit and sense by Love’s art,

Such that he was discomforted;

Was she alive or was she dead?

Gently he clasped her in his arms,

Thinking he felt there tender charms,

That it was with true flesh he dealt,

Yet it was his own hand he felt.

Thus Pygmalion strove to love,

But peace remained at one remove;

His mood unstable, at her side,

He loved and hated, laughed and cried,

Now was happy, now ill at ease,

Now tormented, now all did please.

He dressed the statue in diverse ways,

In robes, skilfully wrought always,

Clothes woven of silk or cotton,

Of pure wool, of finest linen,

In vert, or russet, or azure,

The colours bright, and fresh, and pure.

Many were lined with rich fur,

Ermine, or grey, or subtle vair.

He’d unclothe her, and then re-try

The effect of silk stuffs on the eye,

Sendal, Arabian melequin,

In purple, scarlet, yellow, green,

Then ornate samite or camelot.

Angelic faces might be forgot

Beside her face of innocence,

Which indeed he would then commence

To surround with a full headdress,

Wimple, kerchief and all the rest,

Yet took care not to veil her face

For he had no longing to embrace

That custom of the Saracen,

Who covers the face of woman,

So full is he of jealousy,

Such that no passer-by may see

A woman’s face as they go past.

At another time, in clear contrast,

He’d remove it, then add for show

Ornaments, crimson and indigo,

Green and yellow, fine and noble,

Silk and gold, and fair seed-pearl.

Above the ornament he’d set

A delicate gold coronet,

Where was many a precious stone,

In squared settings, richly shown,

Each facet semi-circular;

And many a small gem, bright and rare,

Many more than I could count,

About the gold crown he did mount.

And from her small neat ears he hung

Earrings from which gold pendants swung.

Then, to hold her collar in place,

Two gold clips did her neck embrace,

Another, there, her breast embraced,

While a slender belt clasped her waist;

Yet it was so rich and fair a belt

No other maid its like has felt,

And from the belt he hung a purse,

None more precious doth disburse

Any man; five small stones were set

Within, he from the shore did get,

The kind with which maids play around

When they find them, pretty and round.

And then he gave great attention

To her two shoes, I should mention,

And stockings, trimmed what’s more

Two finger-lengths from the floor;

(No boots though did he add to this

For the maid was not born in Paris,

They prove too coarse as footwear

For a young girl not born there)

Then with a needle of fine gold,

Which a golden thread did hold,

So that she might be better dressed

Sewed up her sleeves to match the rest.

Then he brought to her fresh flowers

With which, in springtime bowers,

Pretty girls make lovely garlands;

And little birds placed in her hands,

And every diverse novel thing

That to maids doth pleasure bring.

Chaplets he wove from the flowers

Upon which he spent long hours,

Yet unlike any you have seen.

A gold ring he placed, there to gleam

Upon her finger, and then he said:

‘Sweet one, here now we are wed,

For I am yours, and you are mine;

May Hymen and Juno incline

Towards us, and with joy appear;

(No priest or clerk needs visit here,

No prelate’s mitre shall us please)

For they’re the feast’s true deities.

Then, in a loud clear voice, he sang,

For filled with his great joy it rang,

In lieu of the Mass, fair chansonettes,

Concerning love’s delicious secrets,

And made his instruments sound out,

So none might hear God’s thunder shout,

For he’d a host, of diverse fashion,

And hands more skilled, in addition,

Than Amphion of Thebes possessed,

Harps, gigues and rebecs, and the rest,

Guitars and lutes, in full measure,

All such chosen to bring pleasure;

And his clocks he made to sound

In his hall, and the rooms around,

All by means of intricate wheels,

To run sweet, and ring their peals;

He had organs, held in one hand,

Thus portative, you understand,

So the bellows he could squeeze,

While he sang as he might please,

Motets, in treble or tenor voice;

Then in the cymbals he’d rejoice,

Or seize a fretel and flute away,

On a chalumeau pipe, or play

On some drum or tambourine,

Full loud as any could, I wean;

Bagpipes, trumpet, and citole,

And the psaltery, and viol,

He would take and play them all,

All as the notes did rise and fall,

Then take up his bagpipes, set

To work, the Cornish or musette,

And then spring, leap and prance,

Through the halls in rapid dance;

He clasped her hand tight, so to do,

But heavy-heartedly tis true,

For, despite his exhortation,

No answer came from his creation.

He took her in his arms, once more,

And lay beside her, as before,

And embraced and kissed her close,

But did no good, you may suppose,

As when two kiss, all at their ease,

And yet the gods they cannot please.

Thus Pygmalion, so deceived,

Captive of what he’d conceived,

Moved by his dumb statue, fell

Beneath the madness of her spell.

He decked her out in every way,

And sought to serve her night and day,

Though she appeared no less lovely

When naked as when dressed finely.

It happened, in that country fair,

A feast was celebrated where

Many a wondrous thing occurred

And all its people, at the word,

Came, like the youth, to keep vigil

All day before Venus’ temple;

He came in hopes of good counsel,

Regarding his love, in his trouble,

For to the gods he did complain,

Of this sweet love that dealt such pain.

For many a time he had served

The gods well, as they’d observed,

Since he was a fine, skilled worker,

Carving their sacred statues ever,

Who lived, in his maturity,

A life of perfect chastity.

Chapter CVII: Pygmalion’s prayer to the gods is answered

‘FAIR gods, he cried, ‘who can do all,

May my prayer now on your ears fall;

And you, the Lady of this place,

Saint Venus, fill me now with grace,

For angered you must be with me,

Who have so worshipped Chastity,

That I deserve great punishment

For all the time with her I’ve spent.

No more malingering; I repent;

Let pardon be your kind intent,

Grant me now, of your mercy,

Your sweetness, and your amity,

Pardon; to banishment I’ll flee,

Should I not shun now Chastity,

If but she who stole my heart,

Who seems ivory in every part,

Might become my faithful lover,

Her body, soul and life discover.

And if you grant me this in haste,

And I hereafter am found chaste,

Then I agree that I should die,

Be cut to pieces, hanged on high,

Or Cerberus, Hell’s guardian,

May bind me with an iron band;

Then watch it swallow me alive

His triple gorge wherein I’ll dive.’

Venus heard the young man’s prayer

And was overjoyed by this affair;

He’d now abandoned Chastity,

And strove to serve her loyally,

As a truly repentant lover,

Ready, in penitence, to suffer

All naked now in his love’s arms,

If life was granted to her charms.

For joy, then, and to put an end

To the youth’s sorrows, she did send

A soul into that statue’s breast,

Which gave it life and, for the rest,

None there was in any country

Had ever seen so fair a lady.

Pygmalion, being in great haste,

No time dare in the temple waste,

But to his statue swift returned,

Now his pardon he had earned.

For he, indeed, could barely wait

To see her, hold her, she, his fate.

He ran and skipped for all that day,

Till he reached her, along the way.

He knew naught of the miracle,

But to the gods was most loyal,

And now that he saw her nearer

His heart it burned ever brighter.

He saw that she was alive no less,

He uncovered her naked flesh,

And saw her blonde hair shining,

Like fair waves together flowing,

And felt the bones, and saw the veins,

Full of blood, that waxes and wanes,

Feeling a pulse move there and beat.

A lie perchance, or truth complete?

He drew back, knew not what to do,

Nor dare draw too close, in view

Of his fear of being enchanted.

‘What now, am I being tempted?’

Am I awake? No, tis a dream,

Yet none e’er saw so true a dream.

A dream! I wake; no dream is this;

Whence comes this miracle? She is

Possessed within by some phantom,

Perchance, or by some foul demon?’

At once the maid, so pleasing fair,

With her lovely flowing hair,

Replied to him: ‘I am no demon,

My dear friend, nor a phantom,

Rather I am your sweet lover,

And ready all my love to offer,

And to receive your company

If you’ll accept true love from me.’

Once he’d found the thing was fact

The miracle a divine act,

And drawn closer for assurance

That hers was a living glance,

He pledged himself willingly,

As one who was hers entirely;

They bound themselves in speech,

As thanks passed from each to each.

There was no joy left unexpressed,

And deep in love they embraced,

Like two doves kissed one another,

Loved and delighted each other.

Both to the gods thanks rendered,

For the favour they’d extended;

To the goddess Venus mostly,

Who had helped them more than any.

Now was Pygmalion at ease,

Nothing now could him displease,

For she refused naught he wished,

If he opposed her, she’d desist,

If she commanded, he obeyed,

Every wish that she displayed

He now hastened to approve;

Now he could lie beside his love,

Sans resistance or denial,

And she, since they loved so well,

Bore Paphus, who gave his name

To Paphos, the isle known to fame.

From him descended Cynaras,

A splendid king except, alas,

That he was tricked by his daughter,

And brought to ill; that was Myrrha

The Fair, one whom disaster found,

For the Crone (whom God confound!)

Who feared not to sin outright,

Brought her to his bed at night.

The queen was at a feast, dining.

The girl lay down beside the king,

And he knew naught by word or sign

Of her incestuous design.

It was a strange trick to play,

That he should know her in this way.

After his bed she did adorn,

The fair Adonis then was born,

And she was changed into a tree,

For the king had slain her if he

Had come to know of the fraud;

Yet the truth ne’er ran abroad,

For when he had the candles brought

She, now no longer virgin, sought

To vanish in the shades of night,

Lest he should destroy her quite.

All this strays far from my matter,

Tis right I take it no further,

For you’ll know all it signifies

Ere this Romance I realise;

No longer now shall I delay,

I’ll return to the former way,

For I must plough another field.

Whoever then might seek to yield

A comparison of those statues,

As to their beauty, which to choose,

Could draw one thus, it seems to me:

As much as a mouse in degree

Is smaller than a lion, and less

In bodily strength, and worthiness,

Pygmalion’s was less lovely

Than this image, I swear truly,

That I here esteem so greatly.

Venus gazed long and closely,

At the statue that I described,

The statue that had been devised

To dwell, on either side a pillar,

Upon the tower, in the centre;

None did I view more willingly,

And so adore, on bended knee,

The opening and the sanctuary.

For all the gods’ fine archery,

I’d not forsake it, nor forego

My entry, for arrow or bow;

At least I’d do all in my power

Whate’er might come at that same hour,

To find one who might so offer

Entry, or but my presence suffer.

For I, by God, have sworn a vow

To those relics I speak of now,

Which I will seek, if God please,

The moment I regain my ease,

With sack and staff, and may He

Protect me from all trickery,

And the barrier such may pose,

To my enjoyment of the Rose!

Venus now delayed no longer,

She let fly with brand and feather,

And so loosed her burning dart

As to bring panic through her art.

But Venus did so covertly

Launch the dart, that none did see

However closely they were watching

The burning brand, nor its landing.

Chapter CVIII: The castle is taken

(Lines 22049-22500)

How those of the castle came forth

As soon as they felt all the force

Of fair Venus’ burning brand;

None fought naked, you’ll understand.

‘The castle is taken’

ONCE the burning brand had flown,

Panic amongst the foe was sown,

Fire blazed out about the tower;

It seemed captured that very hour.

None could from the fire recover,

Nor could they defend the tower.

All cried out: ‘Betrayed! Betrayed!

‘We are all dead! The tower’s unmade!

Woe, woe! Now flee the country.’

And each hurled away their key.

Resistance seemed good as dead,

His clothes burning, as he fled

Fast as a stag over the heath.

None lingered there, to bring relief;

Each, with their clothes around their waist,

Thought only to depart, in haste.

Fear fled, and forth came Shame,

All left the castle wreathed in flame.

None then wished to heed the lesson

That was taught to them by Reason.

At this point appeared Courtesy,

That worthy, fair, and noble lady;

On viewing the rout, her desire

To snatch her son from out the fire;

So with Openness and Pity,

She commenced a sudden sally,

Deterred by naught, as on she came,

To save Fair-Welcome from the flame.

Courtesy, she addressed him first,

For she was ne’er slow to rehearse

Her eloquence and, much relieved,

Said: ‘Fair son, how I have grieved,

All full of sorrow was my heart,

That you were in prison, apart;

May ill-fire and an ill-flame burn

He who served you that evil turn!

Now, thank God, you are delivered

From Ill-Talk the slanderer; dead,

In the moat beyond, he lies, hard

By his crew of Norman drunkards;

Now he can neither see nor hear.

Nor Jealousy ought you to fear;

One should not through Jealousy

Forbear to live full joyously,

Nor seek comfort from a friend

In privacy, I would contend;

For she no longer has the power

To hear or see, though she glower;

There’s none here to tell her aught,

Nor could she find you if she sought.

And the others, arrogant, vile,

Haste, the wretches, to long exile.

Disconsolate, they fled swiftly;

The castle is completely empty.

Fair sweet son, by God’s mercy,

Don’t let yourself be burned, be free;

We beg you, out of amity,

I, and Openness, and Pity,

Grant to this faithful Lover

Whate’er he may ask; for, ever,

Has he suffered pain for you,

And never has he proved untrue.

He’s ne’er deceived you, he confesses,

Receive him, and what he possesses;

His very soul he offers you,

For love of God, receive it too.

Fair sweet son, do not refuse me,

By the loyalty you owe me,

And by Amor who sets his course,

And drives him on with such great force.

Fair son, Love conquers everything,

All’s in his power; so doth sing

Virgil, who doth confirm the thought,

Which in a fine verse he hath caught,

“Love conquers all,” you there will find,

If through the Eclogues you do wind;

He says that we should welcome love;

And good and true his verse doth prove,

A single line doth thus regale,

Nor could he tell a better tale.

Fair son, now rescue this Lover,

So God may love both together,

Grant him the gift now of the Rose.’

‘Lady, I shall, you may suppose

Right willingly,’ Fair-Welcome said,

‘He may pluck it, the gift be sped,

While there are but the two of us;

I should have been more generous,

For he loves, I see, without guile.’

I thanked him then in noble style,

And soon, like a good pilgrim, went

Wholehearted, fervent, impatient,

Thence, as a true lover should do

After so great a favour, to

Seek the end of my pilgrimage,

And to that shrine made my voyage.

Chapter CVIII: The Lover sets out to win the Rose

WITH a deal of effort, I bore along,

My sack, and my staff, stiff and strong,

That needs not be shod with iron,

For journeying; and travelled on.

The sack too was fashioned well,

Of skin both seamless and supple,

And know it was far from empty,

For Nature, who gave it to me,

Had placed within, with great care,

At the same time, working there

As diligently as she knew how,

Two hammers; two she did allow,

So subtly made, it seems to me,

She knew her craft more profoundly

Than Daedalus; she made the pair

As I believe, that I might hammer

Away, at need, as I went along,

And so she made them good and strong.

And so I shall do certainly,

If there’s any possibility;

For, God be thanked, I do know how.

For I place greater weight, I vow,

On my sack, and my hammers two,

Than my lute and my harp; tis true.

Nature did me a great honour

In arming me with the hammer,

And taught the use, and altogether

Made me a good and wise worker:

The staff too she herself had made,

As a gift to me it was conveyed,

And put her hand to polishing it,

Ere ever I learned to read a bit;

But twas not necessary to tip it,

With iron, tis no less without it.

And, since I did receive it, ever

It goes with me, I leave it never,

Have not lost it, for e’en an hour,

Nor will not, if tis in my power,

For I’d not be deprived its hold

For fifty million livres in gold.

Her fine gift, I guard it closely,

And when I gaze on it am happy,

And give thanks for her present

When I grasp it, and am content.

For many a time it comforts me

In any place where I may be,

And serves me well, do you know how?

If I find myself in a place now

That’s remote, as on I journey,

I’ll set it in the holes before me,

Whene’er my road I cannot see,

To know if I can ford them safely,

And then I can boast quite freely

That there’s no obstacle to fear;

Thus readily the fords I clear,

Through each river, and each spring.

But some are deep as anything,

And with their sides so far apart,

Twould require less pain, less art,

To swim a good two leagues or more,

Through the waves, along the shore;

And less weariness twould afford

Than passing so perilous a ford.

For many a deep one I have tried,

And yet have reached the other side;

For when I was ready to begin,

I’d try them, ere I entered in,

And if they proved so profound,

It seemed no bottom could be found,

With a pole, or e’en with an oar,

Then I would go along the shore,

Where either bank did there extend,

Such that I came forth in the end;

But I’d not have emerged, you see,

If I had lacked the armoury

That Nature granted me outright.

Let those on such broad roads alight,

Who seek to go there willingly,

Let us on narrow paths go free

That lead us on, delightfully,

Seducing us, intriguingly,

Not those cart-roads full of strife;

We who seek the pleasant life.

Chapter CVIII: The Lover on rich old women

YET old roads bring greater gain,

Than those new ones in the main;

More things you find there, truly,

From which you may profit greatly.

Juvenal himself doth state:

Who seeks a path to great estate

Can journey by no shorter one,

Than finding a rich old woman;

If he seeks to serve her gladly,

It boosts him to the heights swiftly.

And Ovid says, if you read him,

In a tried and trusted maxim,

That he who takes up with the old

Will often win his weight in gold;

By dealing in such merchandise

Thus he may soon be rich likewise.

But he who doth so must beware

To say and do naught, anywhere,

That might seem but trickery,

If her love he’d steal, e’en if he

Seeks to snare her honestly yet

In the windings of Love’s net.

For by those wretches, hard and old,

Whose youth long ago grew cold,

(Youth when they knew flattery,

And were robbed through trickery,

And were oft the more-deceived)

They are more readily perceived,

Those sweet lies, than by young girls

Of tender age, with golden curls,

Who when they hear the flatterer

Suspect no trickery whatever;

Trickery and guile they’re liable,

To think as true as is the Bible;

For they have not been scalded yet.

But the wrinkled old ne’er forget,

Malicious and cunning they see

Through all the arts of trickery,

Deployment of which they sense,

With time, and with experience,

So that when the flatterers come

And with their lies fill the room,

And drum into their ears, apace,

All their deceitful pleas for grace,

And abase themselves and sigh,

Clasp their hands, and mercy cry,

And seek to kneel, and bow full low,

And flood the place with weeping so,

And cross themselves before a lady

So as to appear trustworthy,

And promise, quite deceitfully,

Goods and service, heart and body,

And pledge themselves and swear,

By all the blessed saints, that there

Ever were, or are, or shall be,

They know that tis but flattery,

That what into their ears were dinned,

Are merely words, borne on the wind.

Such men do as the fowlers do,

Who spread their nets, and not a few,

Then call the birds with their sweet airs,

So they may trap them in their snares.

Spread in the bushes, you understand,

And then may take their birds in hand.

Some foolish bird will oft draw near,

That knows not the false snare to fear,

Nor can resolve that strange sophism,

A string of sounds yet pure deception;

So doth the hunter cheat the quail,

That into the net the bird might sail,

And when the quail hears the sound

It draws near, over the ground,

And throws itself into the snare

That the hunter has set with care

In the dense new grass, in spring.

But old quails, wary of everything,

Scalded, beaten, as they have been,

Full many a snare they have seen,

From which it seems they had fled,

When they should have been, instead,

Taken amidst the new-born grass.

Such are these old women, alas,

Whose favours were once in request;

Who, by such suitors then distressed,

Now know, by the words they hear,

By those countenances they fear,

Such trickery; know it from afar,

More wary now of what doth mar.

Or if the suitors seem in earnest,

In wishing to reap love’s harvest,

Much like those who, once caught,

That the net’s sweet solace sought,

Find their travail so delightful,

Nothing being more agreeable,

Than the fond hope, they believe,

That doth so please them, and doth grieve;

Then they’re filled with suspicion,

Frightened of the angler’s mission,

And so they listen and reflect,

As if some lie they would detect,

And weigh every word they hear,

So much plain fraud they do fear,

Because of all that’s gone before,

Of which the memory is sore.

Every old woman doth believe

That all are labouring to deceive.

If you wish to incline your heart

To such, the sooner to depart

With riches, or to find pleasure,

You may have both, at your leisure;

You readily can trace that road,

Make comfort, pleasure, your abode.

And you who wish for some young maid,

By me shall never be betrayed,

Howe’er my master may command,

(For all’s fair that he doth demand.)

I’ll tell you true, I’d not deceive,

(Believe me all who would believe)

That it is good to try all things,

Better to savour what life brings,

Just as the gourmet doth linger

Over morsels, a connoisseur,

Of titbits, tasting every dish,

Simmered, roasted, at his wish,

Fried, marinaded, en galantine,

When in the kitchen he is seen;

Knows which to praise as fitter,

This too sweet, and this too bitter,

For every one he’s tested out.

Thus believe me, there’s no doubt,

That he who has not tried the bad

Knows naught of the good to be had,

As one can only know of shame,

Who knows all of honour’s game.

None knows if a thing is easy,

If they’ve not met with difficulty,

Nor do those deserve their ease,

Who wish to never know unease;

So to that man no comfort offer

Who doth not know how to suffer.

And so things go, by contraries,

One reveals the other, and he

Who would seek to define the one

Must bring to mind the other one,

Or he will fail of his intention,

And never frame the definition,

For he who does not know the two,

Fails to perceive their difference, too,

Without which it will come to naught,

That definition that he sought.

Chapter CVIII: The Lover reaches the sanctuary

IF all the equipment that I bore

I could but bear to that fair port,

I wished to touch it to the relic,

If I could fittingly approach it.

I’d come so far, so much had done,

My staff untipped by any iron,

That, vigorous and agile still,

Without delay, I knelt, at will,

Betwixt that pair of pillars fair,

So keen was I to worship, there,

That fair sanctuary, on my part

With a pious and devoted heart.

All had been razed by that fierce fire,

To war with which naught dare aspire;

All had been levelled to the earth

Except that thing of precious worth.

I raised the curtain a little way

Which covered the relic alway,

And approached the statue closely,

To know the shrine, more deeply.

Kissing it now most devoutly,

And, wishing to enter safely,

I thrust my staff in the opening,

Leaving the weighty sack hanging.

I thought to penetrate easily;

My staff rebounded back on me;

I thrust in vain, again to fail,

I could not, despite all, prevail,

Something therein prevented me,

Which I could feel, but could not see,

And it had blocked the opening,

From the creation of this thing,

For it bordered on the aperture,

So it was strong and more secure.

I tried again now, oft assailing,

Thrusting hard, but ever failing,

And if you’d seen me jousting there,

Positioning yourself with care,

Hercules you would oft remember,

He who would Cacus dismember,

Three times battering at his door,

Three times falling to the floor,

Three times, wearied half to death,

Sitting there to catch his breath,

So great the pain and his labour;

And I, who did likewise suffer,

Covered with sweat, in anguish,

Sad and weary, I did languish,

At failing to break the door so,

Like Hercules, or even more so.

But I strove so hard, nonetheless

I perceived the means of ingress,

A narrow passage by which I sought

To pass the blockage I now fought.

By means of this, narrow and tight,

Through which I sought to pass outright,

I broke down the obstruction,

And, moving in that direction,

Gained access to the aperture,

But only half-way, and no more,

Troubled I could go no deeper,

But possessing not the power.

Yet I’d cease not for anything,

Until that staff was fully in.

So I pushed on without delay,

Though the sack was in the way,

With its two hammers hanging

Outside, and there remaining.

I was now somewhat in distress,

Caused by the entry’s narrowness;

For I’d not freed sufficient space

To move an inch within that place;

And, if I knew aught about it,

No other had yet passed through it,

And I was the first so to do,

And, as of yet, it was so new

None charged a toll to enter it.

Whether it’s granted benefit

To other entrants since, that I

Know not, but I so loved that I

Could scarcely believe that any

Had been there before me, truly;

For no one disbelieves lightly

In the beloved, shame weighs heavy,

And I shall not believe it now.

At least I knew that, anyhow,

It was no well-worn beaten track,

And other paths there I did lack,

To gain entry ere others should,

And take the rosebud, as I would.

You shall know how I went on,

Till, at my pleasure it was won.

You shall know, both deed and manner,

So if the need arises, ever,

In the sweet season of the year,

Young Lords, for you to press full near

The Roses, and gather them too,

Either open or closed to you,

You may act then so discreetly

You shall win them all completely.

Do as you hear that I have done,

Knowing no better course to run;

And if you can, more easily,

Navigate the way, more deftly,

Tire yourself less, strain less than I,

Find a better means to pass by,

Then do so in your manner, tis fine,

Once you know all this path of mine.

At least you have this advantage,

That I tell you of the passage

Without robbing you of a sou;

For that you should be grateful too.

Chapter CVIII: The Lover arrives at the rosebush

CRAMPED as I was in there, twas clear

That I could touch the bush, so near

That, stretching out my hand I could

Draw back the branch, and take the bud.

Fair-Welcome had begged, with a prayer,

That I commit no outrage there,

And since he’d asked me in God’s name,

I’d sworn to him I’d shun the same,

And do all that was good and fine,

In accord with his wish and mine.

Chapter CIX: The Lover wins the Rose

(Lines 22501-22580)

The ending of the Romance is:

That the Lover attains his wish

And wins the Rose he doth admire,

Which has aroused all his desire.

‘The Lover wins the Rose’

I took the rosebush by the waist

Suppler than any willow I’d faced;

And, gripping it with either hand,

Then, very gently I began,

Shunning the thorns, to shake the bud,

Yet spoil it as little as I could,

Although I could not help but make

The branches to tremble and shake,

Yet drew not any branch too far,

For naught there did I wish to mar;

Though I had to, in due course,

Scrape the bark with a little force,

Since no other means did I know

To win that which I longed for so.

And, in the end, I had, indeed,

Over the bud, spread a little seed

When I had shaken the bud about.

That was as I touched it, no doubt,

Within, to examine each petal,

For I desired to search it all,

To the very depths of the bud,

Since, to me, all within seemed good;

Such that I mixed the seeds together,

So they could scarce be parted ever,

And thus all the bud so tender,

I made to swell and grow fuller.

See you how wrong I was in this;

But for all that I worked in this,

That sweet fellow, who thought no ill,

He would bear me yet no ill will;

Rather he’d suffer such, and agree

Whate’er he thought pleasing to me;

He’d but remind me of my pledge

And that I wronged him he’d allege,

And I was too rough, he would say,

Yet still he’d let me have my way,

To take, and reveal all, and gather

Both Bush and Rose; leaf and flower.

Now, exalted to such high degree,

An estate I had gained so nobly,

My method in no way suspect

Since I’d proved loyal, and direct

And open, with each benefactor,

As so ought every good debtor,

For I was much obliged to them,

Since it was purely through them

That I was now so rich; indeed,

No other wealth could this exceed,

I rendered thanks, ten or twenty

Times, to Amor and Venus gladly,

Who had aided me most of all,

Then to the host before the wall,

Whose help I pray God will never

Remove from the true lover;

Speaking twixt each fragrant kiss,

Yet Reason included not in this,

She who’d granted me naught but pain;

And cursed vile Wealth who, again,

Had shown me not the least pity,

When she had refused me entry

To the path that she guarded there.

For this path she’d failed to care,

By which I had struggled within,

For all secretly had I entered in;

Cursed too each mortal enemy,

Especially vile Jealousy

Who had so obstructed me,

With her chaplet of anxiety,

Who doth from Lovers guard the Roses,

And even now great danger poses.

Ere I removed from that fair place

(A garden that I yet would grace)

With great delight, I did gather,

From that leafy bush, the flower,

And so the crimson Rose I won;

Day broke, I woke; my dream was done.

The End of Part XII, and of the Romance of the Rose Continuation