Renaud de Beaujeu

Le Bel Inconnu (The Fair Unknown)

Part V

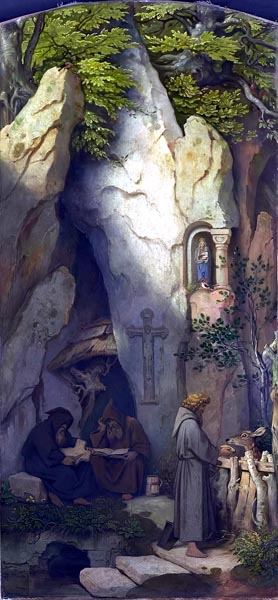

Moritz Ludwig von Schwind (Austrian, 1804-1871)

Picryl

Every single thing God had made,

Skilfully wrought, and there displayed.

In the walls there were windows too,

To allow the warm sunlight through

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2023, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- A maiden appears, an emissary from the Lady of the Isle of Gold.

- She summons Gingalain to her mistress.

- The Lady of the White Hands welcomes Gingalain to her garden.

- Gingalain replies to her admonishment of him.

- The lady relents.

- They dine, then retire to rest; the lady issues a warning.

- Gingalain leaves his bed at midnight.

- He tries to enter her room, but is possessed by an enchantment.

- Roused from his vision, he returns to bed.

- He is thwarted again, and vows not to repeat his error.

- Gingalain is summoned by the lady.

- He enters the lady’s chamber.

- The pair fulfil their every desire.

- Renaud comments on his own case.

- Gingalain recalls the incidents that night.

- She explains her knowledge of the magic arts.

- Gingalain confirms his loyalty, and her noblemen assure him of theirs.

- We return to Blonde Esmerée, on her way to Arthur’s court.

- She reaches London, with the four knights she has met.

A maiden appears, an emissary from the Lady of the Isle of Gold

Robert kept watch o’er his master,

Which added to his own pallor,

Seeing him tormented by Love,

Which oft him to tears did move.

Made anxious by Gingalain’s hue,

His lord’s needs he did then pursue.

For great was the knight’s wretchedness,

Enfeebled, saddened to excess.

Words of solace he went seeking;

And had scarcely finished speaking

When a fair maiden made entry

To their rooms, in the hostelry.

She was a most well-mannered maid,

Hallmarks of virtue she displayed,

Clad in a mantle lined with vair;

Brocade, with gold threads everywhere.

Noble the maid was, and she wore

A fine robe, of two halves they saw;

One part was silk, of purple hue,

The other flowery; the fur too

Lining her cape was of two kinds,

As if its maker was of two minds,

One rich vair out of Hungary,

The other ermine, both fine to see.

O’er the purple lay the latter,

O’er the flowery silk the former.

A sable trim too had the cape;

Rich was the fur about her nape.

As for the mantle’s fair brocade,

It too was most artfully made,

For all the workmanship was rare;

Never was there seen, anywhere,

A finer robe than that she wore;

They went well together, they saw.

She summons Gingalain to her mistress

Gingalain, on seeing the maid,

Bowed low, and a welcome conveyed,

While she returned the compliment:

‘May God, who is omnipotent.

Grant you all your heart may desire,

From her that made it so aspire.

Sir, my lady sends you greeting;

Tis she whom you came here seeking,

The lady who rules o’er this city;

One in a hundred thousand is she.

These garments she has sent to you,

And asks that you visit her; do

So, I beg you, without delay,

As soon as you are well, and may.’

Gingalain heard her joyfully;

‘I am completely cured’, cried he.

‘For I’m rid of my ills entire

Since I’ll see her whom I desire.

There’s naught now from which I suffer,

Since she would have me recover.

God be praised that, through His grace,

She now wishes to view my face!

Blessed be the lady, and this news;

My pain is eased, whate’er ensues.’

He expressed his joy to the maid,

And soon was in fine robes arrayed,

Silken garments that she had brought,

Full ready to appear at court.

The rich clothing suited him well,

Though his pallor, hard to dispel,

Still painted all his face with woe.

His cheeks were pale, yet, even so,

One might search for many a year

Before one found a chevalier,

As brave, wise, handsome, I believe.

The maiden took him by the sleeve,

And said to him: ‘Come now, away,

To see my lady, for we delay.’

‘With pleasure.’ Gingalain replied,

And, with the maiden at his side,

Took to the street that, by and by,

Led to the palace, there, on high.

On entering, they hurried through,

And by a door issued forth, anew,

Into a garden, where his eyes

Saw much indeed to praise, and prize.

Marble the walls that closed it round,

Upon which, in relief, was found

Every single thing God had made,

Skilfully wrought, and there displayed.

In the walls there were windows too,

To allow the warm sunlight through;

In solid silver they were set,

No nobler sight the eye ere met;

None was as fine, or rich, or fair.

God made never a tree, that there

Had not been found, midst the array,

Had one but searched it all, I say.

There were laurels in quantity,

Many a fig and almond tree,

Many a sycamore and pine,

Palm, and medlar, in its design,

Pomegranate, and oleander,

Planted there, with every other.

Its riches yielded liquorice,

Spices, incense, all that there is,

For God tree, herb or root ne’er wrought

That to that place had not been brought:

Zedoary, and pyrethrum,

Galingale, cloves and cinnamon,

Spikenard, pepper, cumin too,

Came of the wealth that therein grew.

The roses there were without peer,

Bringing forth flowers all the year.

And midst that garden could be heard

The song of many a tuneful bird.

Calandra-larks, amidst its vales,

Orioles too, and nightingales,

Thrushes, and blackbirds, sang away,

Nor ever sought their song to stay.

Such perfumes rose there, at all hours,

From those herbs, and from those flowers,

That any there would not think twice

Ere claiming: ‘Here, lies paradise’.

The Lady of the White Hands welcomes Gingalain to her garden

Gingalain, and the lovely maid

Whom he accompanied and obeyed,

Walked midst the garden till they came

To a fair place within that same,

Where the lady he’d longed to see,

Neath the shade of an olive-tree,

Was surrounded by her young maids

And ladies, in their silk brocades.

The sight was one that brought him cheer.

The lady, seeing him draw near,

Rose to greet him as he did so.

Not she, that set Paris aglow,

Helen, fairer than any seen,

Not Byblis, nor Iseult the Queen,

Lavinia of Lombardy

That Aeneas wed in Italy,

No, nor Morgan le Fay, surely

Possessed a tenth of her beauty.

As well compare her to anyone

As the pale moon to the noon sun;

There was not her equal on Earth,

That to no fairer ere gave birth.

Great was her fame that fair lady.

Gingalain bowed to her humbly.

When he appeared before her face,

The lady welcomed him with grace,

And next acknowledged the young maid,

Then, taking his bare hand, conveyed

The wish that he should sit by her,

On a cushion with silk cover.

Opposite the maids were arrayed;

Admiration that throng displayed,

All there gazing at their lady,

For they knew naught of rarer beauty.

Said the lady: ‘How are you, now?’

‘Both well and ill, I must avow,

My lady; through you, I suffer pain,

May God grant that never again

Shall I pass a fortnight as ill

As that gone by; I feel it still.

And yet, may I suffer like this,

As long as it may be your wish’.

‘Come, now!’ cried the lady, ‘Sir knight,

Have you naught better to recite?

What can the cause of your woe be?

I’m sure tis naught to do with me.

Rather you seek to insult me here,

As you did once before, I fear.

As for me, should I lose your love,

If you as faithless were to prove

Once more, my life too I would lose.

Tis I, not you, Love doth abuse.’

Gingalain replies to her admonishment of him

The youth reddened on hearing this;

Crimson grew those cheeks of his.

He seemed as handsome as before,

Indeed, no knight on any shore

Could equal him in form and face;

In all the world none matched his grace.

He was valiant, courteous, wise,

And replied in eloquent guise:

‘Lady, have you not made me pay

Most dearly for my sin that day

Of failing to take leave of you,

Obliged my quest to then pursue?

My lady, gentle and debonaire,

Will not one who is sweet and fair,

Take pity on a poor knight who

Is pledge to do all he can do,

Whatever indeed that may please,

To win pardon, and ne’er shall cease.

My heart is yours, indeed tis true,

If your faith in me you’ll renew,

Amor shall stand my guarantor;

For, lady, I shall die, for sure,

If you’ll not take pity on me.

Delivered to death I shall be,

Should you seek not to ease my woes,

And through your kindness bring repose.’

The lady gazed at him a while,

And he at her; each did beguile

The other; two hearts were as one;

In truth, when all is said and done,

The maid loved him, as at the start,

Though she’d tried to hide her heart.

With all her heart she loved the knight,

Though she’d concealed her love from sight.

Indeed, their hearts were so on fire,

They owned but one heart, one desire.

Each o’er the other sorrowed more

Than Tristan and Iseult had before.

What can one say of such a tale?

Grace and beauty will e’er prevail.

The lady relents

The lady gazed at his handsome face,

And then declared: ‘No small disgrace

You brought upon yourself, despite

Your wit and prowess as a knight.

Yet this sole fault I here reprove,

Your ignorance of how to love.

Ill you wrought by your clumsiness,

Though many a virtue you possess,

For I confess this truth to you,

(May God recompense me anew,

If ever faith in Him I’ve shown)

I’d have loved more than any known,

If you had but known how to love.

But now, if you do so approve,

I’d have you sojourn here with me.

I find, in you, true nobility,

And I would have you dwell on high;

Too long were you there below, say I.

Here, above, tis far pleasanter,

And then, twill suit your health better.’

Gingalain, ever courteous,

Replied to his fair lady thus:

‘Do you mock me, lady?’ said he.

‘Were I sure you spoke truthfully,

And from the heart, as you do live,

Then there is naught that God could give,

That would bring me greater joy,

Than all my powers to employ

In serving you; I’d have you know

Most willingly to such I’ll go,

For I shall find no joy elsewhere.

Lady, are these true words you share?’

‘Sir, I mock not, nor speak amiss.’

He thanked her then, on hearing this.

Her speech an end to woe had spelt,

And, in his heart, great joy he felt.

They dine, then retire to rest; the lady issues a warning

Directly, from the garden, they

Into the palace, made their way,

A place of beauty, and delight.

Tables were laid there, in plain sight,

For supper; forth went the commands

For cool water to bathe their hands,

And then they all sat down to eat.

Bread and wine, all that was meet,

Every kind of delicious fare,

All they might wish, was offered there.

When the court had dined at leisure,

Eaten, and drunk, in full measure,

They rose, expressing their delight,

For it was now quite late at night,

And time for folk to seek their rest.

Knights, and ladies, the paths addressed

That led to their dwellings below,

While Gingalain, now free of woe,

Rejoiced that he alone might stay,

Close to his lady, at end of day.

Many a pleasant word was said.

The chamberlain made up a bed,

For Gingalain in the great hall,

And twas not an ill one at all;

Silken sheets from Byzantium,

Fit for a king to lie upon,

And silk coverlets had that bed,

On seeing which, the lady said:

‘My friend, on silken sheets you’ll lie,

That might honour a king, say I,

So quit them not, for I implore

You not to flee me as before.

In my own chamber I shall be,

The door ajar, but list to me:

Though I should close it not this night,

Because I do, think not you might

Dare to enter. I’ll say, once more,

I forbid it, though near the door,

Your bed doth lie; attempt it not,

Let not my warning be forgot;

Enter not my private chamber,

Lest I should fear I’m in danger.

Do naught, except at my command.

I go; I leave you in God’s hand.’

‘And I you, lady,’ he replied;

Then they retired on either side.

Gingalain leaves his bed at midnight

Into her chamber went the lady,

His gaze pursuing her closely

Ere she vanished from the light,

Reluctant to lose her from sight.

Then he lay down upon his bed;

Unquiet were the thoughts in his head,

Such that he could not sleep or rest,

Wide awake, and woeful at best.

Often, he gazed towards her door,

Hoping to look on her, once more,

Hoping that she’d leave her chamber,

Visit his bed, as you’ll remember

She had done when he first was there;

Her absence left him in despair.

Great were his woes, Gingalain,

He could scarce be still, for heart’s pain,

Gazing, endlessly, at the door,

Which stood half-open as before.

Often, he stirred, then sat upright,

As if he would visit her that night.

Then of his action did repent,

And inwardly questioned his intent.

‘Lord God,’ said he, ‘what shall I do?

Go, or stay as she asked me to?

She told me that I must not go,

Yet it seems to me, even so,

That she wished I might do so still.

Lord, if I only knew her will!

If I stay, then I think that she

Will, in truth, think little of me.’

Often, he rose, as if to go,

But then, within himself, said no.

To go or not? Thus, he remained,

As in his bed, he oft complained.

Saying full often: ‘Now, I will;

Then, ‘No, I’ll not,’ conflicted still.

Thus, he was restrained by Love,

Who, yet, was urging him to move,

And, in the end, pressed him to go;

Amor, it was, that tortured him so.

He tries to enter her room, but is possessed by an enchantment

He raised himself, though, from his bed,

And slipped a shirt over his head,

Then approached the door, silently,

As midnight neared; yet, suddenly,

As he went towards her chamber,

He could neither move nor enter,

But found himself on a plank of wood,

Above a mighty torrent in flood,

That like a tempest raged and roared;

A wretched foothold it did afford,

He could nor advance nor retreat;

Twas hard enough to keep his feet.

Great now was his desire indeed,

To cross the plank, and great the need,

Viewing the water there below

That shook that quivering plank so.

He felt he was falling, and did well

To grip the plank hard, as he fell,

Such that his body hung below,

Dangling above the torrent’s flow.

Little wonder if he knew fear;

His grasp was weakening, twould appear.

He thought he’d surely fall and drown,

And cried aloud, ere he tumbled down:

‘God, on high, save me! Help me, now!

Death’s nigh without aid, I avow.

Come, succour me, some noble friend;

On this plank, I may not depend!

I cannot grip it for long, say I,

Leave me not here, to fall and die!’

Roused from his vision, he returns to bed

Throughout the palace, people stirred;

His cries were by the servants heard,

Torches and bright candles they brought,

And the source of the trouble sought.

They found Gingalain, after a search,

Clinging to a sparrowhawk’s perch,

Fearful, it seemed, of falling down,

Crying that he would so, and drown.

To that perch, and with all his might

Lest he should perish, clung the knight.

As soon as he saw the servants there,

The river vanished into thin air.

All the enchantment now did fade,

And so, ashamed now and dismayed,

And most wearily, did Gingalain

Return, in woe, to his bed again.

His shame was great, and his anger.

The servants mocked at the danger

He’d perceived, and at all they’d seen;

Thought he: ‘Enchanted, I have been’,

And, from shame, said nary a word.

The servants, thinking him absurd,

Retired to rest; he lay on his bed,

By Love tormented, as I’ve said.

He could find no repose at all,

But simply lay there in the hall,

Much dismayed by his travails,

The wind departed from his sails.

Yet he still gazed upon the door,

Love tormenting him, as before.

‘Dear God,’ he sighed, ‘what have I seen?

What troubled me? Where have I been?

This was some work of trickery.

I know she’s there, whom I would see,

She who makes me endure such ill;

Why should I not speak to her still?

Even if I must count the cost,

And, in doing so, my life be lost,

Should I not, thus troubled, devise

A means to reach her where she lies?

Wretch that I am, why go I not?

Though success was scarcely my lot

When I attempted it before;

I returned, ashamed, to be sure.

And yet tis wrong to say I failed,

Twas but enchantment that prevailed,

I ought not, thus, to yield my ground,

But try again, till she be found,

And see if I may speak to her,

Not merely lie here, and suffer.’

He is thwarted again, and vows not to repeat his error

More determinedly than ever,

He gazed at the lady’s chamber.

Amor had granted him fresh heart

And he was ready, for his part,

Once all was quiet, to try once more;

He rose, and went towards the door.

Suddenly, the whole ceiling’s weight

Seemed to crush him; a cruel fate.

What pain his lady seemed to wish

Upon him! What new trial was this?

Such torment twas, and no mistake,

He thought his very bones would break.

So heavy was the load, at first

He felt his burdened heart might burst.

With all the strength he could muster,

Our knight called aloud for succour:

‘Aid me my friends, help me now,

For I am dying, I avow!

Upon my shoulders, the roof rests;

Its vast weight my endurance tests.

Where are you? For I’ll surely die,

If you should come not, by and by.’

In haste the servants rose once more,

Lit the candles, and there they saw

Gingalain, seemingly quite mad,

His pillow over his head, a sad

Case of illusion; on they came,

While he buried his head in shame

On seeing them, and, to the floor,

Now hurled the pillow that he bore,

Saying not a word to those around,

Failing to voice a single sound.

Silently, he bowed his head low,

And lay down again, full of woe,

Feeling both foolish and ashamed,

Though, in truth, twas Amor he blamed;

Amor goaded and tormented.

To himself, our knight lamented:

‘Alas!’ he cried, ‘perverse as ever!

The door’s still open to her chamber,

And yet I cannot enter there.

Enchanted seems this whole affair,

And I am shamed at every turn.

What have I done such woe to earn?

Dear God, why was I then so bold,

Ignoring all that I was told?

My lady said that I must not,

Nor her injunction be forgot.

Defying her I thought so to do,

And my own desire to pursue.

All that do wrong believe they’re right.

The reasoning I now indict,

That led me to oppose her wish,

And prove rebellious in this;

For the thoughts my mind doth enclose,

Lead not to virtue or repose.

Twice have they brought shame upon me,

If I choose not the contrary

Path, a third time I’ll be shamed.

Rather by death I’d be claimed

This night than do the like again,

For so to do will bring but pain.

To be but twice shamed, as before,

Is better than three times or four.’

Not to approach her room, he swore,

Yet still he gazed towards her door.

Gingalain is summoned by the lady

As he did so, he saw a maid;

Noble the form and face displayed

By the light of the candle she bore,

In her right hand; from out the door

Of the chamber the maiden came,

And to his bed approached that same.

She drew the curtain a little way,

And, pleasantly, to him did say:

‘Are you sleeping, sir?’ Gingalain

Replied: ‘Greetings to you, tis plain

That I sleep not; what is’t you wish?’

Said she: ‘Great good will come of this.

For my lady has sent me here,

And doth summon you to appear.

Through myself, she now invites you

To her room, where she awaits you.

Fair sir, go now, and speak with her;

She holds you to be her lover.’

‘Fair maid,’ said he, ‘is this a dream?

And is naught here as it might seem?’

‘What, sir!’ exclaimed the lovely maid,

‘My lady’s message I’ve conveyed,

And would lead you to her embrace;

Twas you desired to view her face.

This dream is one you shall possess;

Come, for she summons you, no less.’

He enters the lady’s chamber

Gingalain felt intense delight.

Donning a fur-lined robe, our knight

Now leapt from his bed, joyously,

Knowing, his love, he soon would see.’

‘Fair maiden,’ he cried, ‘lead the way!

Sweet friend, let there be no delay;

Noble creature, come, of your grace,

Deign to add speed to this slow pace.’

The maiden smiled at his command,

And gently took him by the hand,

Then led the way towards the door

He’d sought to navigate before.

On entering, at once, he found

Sweet fragrance scented all around,

Sweeter than incense, pyrethrum;

Sweeter, even, than cinnamon.

Such virtue had that fair odour

That any who was in that chamber,

For even a brief while, in pain,

Felt, in a moment, sound again.

Bright candles, lit there, did suffice

To make it seem true paradise.

Of gold and silver, every treasure,

That room held a goodly measure.

Rare silken clothes it held as well,

Of greater value than I can tell;

Many there were, of diverse sort,

Striped taffetas, dress fit for court,

Eastern silks, many a brocade,

After many a fashion made,

Flowery ones; full many a fair

Silken cloth he gazed on there.

High was the chamber and noble,

Silk drapes from Constantinople

Adorned the ceiling overhead,

While precious stones, beneath his tread,

Of many a kind, paved the floor.

Emeralds, sapphires, there he saw,

Many a rare chalcedony,

Many a bright gleaming ruby.

Their colours were intense indeed;

Thereon, its maker had decreed

Flowers and birds most artfully wrought;

For, though throughout the world you sought,

On land or sea, you’d fail to find

Any creature you called to mind,

Beast, fish, serpent, all that’s known,

That was not on that pavement shown.

The lady on her bed did lie.

None richer was ever seen, say I;

I could tell you the nature of it,

Without the truth being forfeit,

Yet to hasten the joy, indeed,

Of which the knight was so in need,

I’ll not seek to describe that bed,

But, lest I weary, press on instead.

The pair fulfil their every desire

The maid who held Gingalain’s hand

Led him to the bed, close did stand,

And in her most courteous manner,

Being a gracious maiden ever,

She addressed her mistress there:

‘Behold, the knight, now in my care,

Whom I have led here as you see!

Grant him a moment, willingly,

Of your good grace, for love of me.

Treat him well, and with honesty.’

The lovely lady at once replied:

‘I’ll honour your request, fair guide,

And treat him well, for love of you,

Go now, and leave me so to do.’

‘Take him then; the knight I render.’

The lady, with a look most tender,

Took his hand; once at her side,

His delight he could scarcely hide.

No man e’er felt such keen delight;

The joy he longed for was in sight.

By each other the lovers lay,

And, once close together, I say,

Most sweetly did the pair embrace,

Lips met, and limbs did interlace.

Each, of the other, had their due.

Kisses could scarce content those two,

For each would more and more impart

Of that which doth delight the heart;

Those loving kisses, unconstrained,

From the heart drew all that pained,

And filled the heart with deepest joy.

Amor led them far from annoy.

Their eyes were turned to gazing quite;

While each now clasped the other tight.

Their hearts were bent on their desire,

Each would claim the other entire.

So greatly each for the other cared,

What each would do, the other shared.

Who knows what they did, he and she?

I was not there, nor aught did see;

But next to her lover sweetly laid,

She could scarcely be called a maid.

That night great solace did afford,

For the long wait that they’d endured.

Renaud comments on his own case

Gingalain had his wish and more,

For he possessed what he’d longed for;

While the lady was scarce dismayed,

But sweetly commanded and obeyed.

For all the ills, and woes, he’d felt,

Which Love to Gingalain had dealt,

She, as his recompense, was sent.

And nor do I of my love repent,

Nor show the least disloyalty

Towards Amor, nor my fair lady,

Who, in a day, could reward me

With more than I deserve; for she

Who can grant a man such delight,

Should be loved, and loved outright.

He that would serve a lady, though

He suffers at length for doing so,

Should not forsake her for an hour;

For the ladies possess such power,

That when they offer recompense,

All our woes, and every offence

We’ve long suffered, is swift forgot.

God made them such, it is our lot

To serve the virtues He instilled

In them, the beauty that He willed;

For God formed men, I do believe

To honour them, and not deceive,

And do all that they may command.

A lout he that takes not the hand

Offered him, for all virtues flow

From them; he’s a fool thinks not so.

Lord God above us, send them joy!

Hear this prayer, that I oft employ:

May those that speak ill of the sex,

And ‘fin amour’, with scant respect,

Be cursed forever, and rendered mute;

Lord God, their lies ever refute!

By their falsehoods flown afar

They but show just what they are,

Who labour so to spread those lies.

Ah, Lord above, that such despise,

When shall I see her, I love so,

And seek my pleasure here below?

Gingalain recalls the incidents that night

Of Gingalain I’ve more to tell,

For whom all that he did was well;

Between his arms he held his love,

Midst kisses that she did approve,

Both at ease; though he did recall

All that had happened in that hall,

The sparrowhawk’s perch, the pillow,

And wondered at it happening so.

Thinking of how he’d hung, or bowed,

He could not help but laugh aloud.

While the fair lady, at his side,

Hearing him laugh, sweetly cried:

‘My love, what entertains you so?

Tell me the cause, for I would know.

But now you laughed aloud; say why.

Dear friend, come give me your reply.

Hide this not, but indulgence lend,’

Gingalain answered: ‘My sweet friend,

I merely laughed aloud in wonder

At the marvels that saw me blunder

Of which none saw the like before,

In the hall there, beside your door,

All that happened to me this night,

When all slept, though my ease was slight,

As I lay abed, so troubled, I fear,

I could not sleep, for you were near.

I was so full of thoughts of you,

I tossed and turned, and turned anew,

Till I fell from my bed indeed,

As love and my passion decreed.

That desire, it was, drove me here,

Though I was enchanted, tis clear,

For at first, when I sought your door,

Here was a plank, and not the floor.

Above the torrent’s foam, I hung,

Loud it roared, but tightly I clung,

For I had fallen in such a way

That I yet gripped the plank, I say,

Though I feared I must fall again.

That I was set to drown was plain.

Greatly afraid that I would die,

I was forced for succour to cry.

All the servants hastened there,

And the end of that sad affair,

Was their seeing me swing and squawk,

Where once perched a sparrowhawk.

A second ill I then endured,

Heavier still, as a harsh reward,

For seeking to reach your chamber,

A greater anguish than ever.

Tis truth I tell; twas scarcely fun;

Lady, know you why this was done?

Tell me the reason, if you know,

For, this night, I was spellbound so.’

‘My love,’ she said, ‘the reason why

You suffered so, I’ll not deny,

For the enchantment all was mine,

Your troubles came by my design,

Because of the shame brought on me

When you once chose to up and flee.

For that reason, the thing was done,

That you might learn (and everyone)

To guard yourself throughout your life

From scorning the sex, maid or wife,

For if you do such wiles employ

Think not that it will bring you joy.

He who betrays a maid, that same

Will meet with but trouble and shame.

Be on your guard against it then,

And so should all other true men.

She explains her knowledge of the magic arts

Now I’ll tell you, if you desire,

How twas I managed to acquire

Such knowledge of the magic arts.

My father was king in these parts;

Powerful, courteous, wise was he,

And had no heir apart from me.

He loved his daughter so truly,

The liberal arts were my study:

Arithmetic, geometry,

Necromancy, astrology,

And the others of the seven.

I learnt of the lights in heaven,

And studied with such firm intent

I understand the firmament,

The motions of the moon and sun,

And all that is by magic done,

And all that the future may hold.

I knew of you, and learnt, of old,

That when you visited that day

You’d seek not to prolong your stay.

I knew then you’d abandon me,

For I divine all that shall be,

Yet knew it mattered not a jot,

(Though success would prove your lot,

In pursuing your bold affair,

Since you would win great honour there)

For still, within my heart, I knew

That your love would yet prove true,

And that as soon as e’er you might,

You would return to me, sir knight.

Through my science I learned all this;

Long ere we were fated to kiss,

I loved you, ere you were a knight,

Long ere you were before my sight,

For I knew that in Arthur’s court

No better man could e’er be sought,

Except that faithful lord, your sire.

Your virtues fuelled my desire;

For that reason, I loved you then,

Met your mother time and again,

Simply that I might see you there,

And that your presence I might share.

Your mother, twas, dubbed you a knight,

Then sent you to the court outright;

There, obeying her strict command,

This royal boon you would demand:

That, whatever might be at stake,

The next quest you must undertake.

I knew that quest would be my own,

This adventure, that you alone

Were destined to pursue, you see,

For tis our mutual destiny.

Through my prescience, twas, I knew

This, the course you must pursue.

And so, dear heart, twas I that sent

Hélie to court, with one intent,

Telling her that she should seek aid

From King Arthur, for me, a maid,

For I was sure, from all I’d learned,

From all my science had discerned,

That you would undertake the quest

And, ere you saved me, never rest.

To obtain your aid, I did so do,

Born of the love I hold for you.

And sweet friend, it was mine, also,

That voice you heard, after the foe,

Mabon, you slew, and then did take

The Cruel Kiss; all for my sake.

My voice it was that, like a sage,

Pronounced your name and lineage,

To grant you peace and calm, outright,

And help you win some rest, that night.

Then all the country learned that you

Had freed their lady, while I knew

I owed it to many a party,

That had supported their lady,

To seek to win you to my side,

And have you take me as your bride.

God be praised, I possess you now!

And, from now on, I here avow,

We shall have peace, and shun discord;

And know this fact, my gentle lord,

As long as you have faith in me,

All you wish you’ll gain instantly,

But if you e’er should cease to trust,

Then lose me, my fair lord, you must.’

Gingalain confirms his loyalty, and her noblemen assure him of theirs

‘Speak no more, my lady,’ said he,

‘Not for all the world shall you see

Me prove so foolish as to lose

My own heart, and thereby refuse

Your strict commandment to obey,

Nor cause you pain in any way.’

With this their speech was at an end.

At dawn, when the sun doth ascend,

The church bells rang; and at first light,

From out the bed, arose the knight.

His lover rose and, with one intent,

To Saint Mary’s church they both went,

There to repent of all trespass,

While the lady chanted the Mass.

Once the Mass was ended, they

Back to the palace made their way,

And the lady sent messages,

To her dukes, counts, and marquises,

Summoning them all to the court,

There to divert themselves and sport,

For her partner she’d now regained,

Whom she had longed for, she explained.

Once the lords of the realm were there,

Her thoughts the lady sought to share:

‘My lords,’ she said, ‘now list to me:

This valorous knight that you see,

Is he whom I have long desired.

Those that to serve me have aspired

Should now be pleased to serve him too,

And what he asks of them should do;

For, in all the world, none is found

In whom more valour doth abound,

And I’d have his commands obeyed.’

They cried all honour would be paid

To the knight, and they would afford

Him due respect, as her true lord.

Now Gingalain of joy was sire,

For he had won his heart’s desire.

We return to Blonde Esmerée, on her way to Arthur’s court

I’ll tell now of Blonde Esmerée.

From Wales, her realm, upon a day,

She had set out for Arthur’s court.

A journey of four days had brought

The queen to a passage from a wood,

Where four knights on horseback stood,

Each on a palfrey not a charger,

Without shields or weapons, rather

They were emerging from a field

Their purpose there simply revealed,

For each bore a fine sparrowhawk,

And of the hunt was all their talk.

Once the queen had reached the four,

She greeted them; that noble corps

Saluted her in return, and all

Who accompanied her, great and small.

She addressed them in this manner:

‘My lords, where go you hereafter?

And who you are I fain would know,

If a queen may pose the question so.’

‘We journey to King Arthur’s court,

My lady, as we, prisoners, ought,

For we are all sworn so to do,

And to that oath we must be true.

Each of us has given his word

To a brave knight who, so we heard,

Goes to rescue a lovely maid;

To the Fair Unknown we have paid

Homage, for so the knight is named,

That victory o’er us all has claimed.

We come not all from the same place;

Yesterday, we came face to face

With each other, upon this scene.

Of what realm are you, fair queen?’

‘By God in heaven, my lords,’ said she,

‘Know this for a truth, come list to me,

I am that maid he went to save.

Your captor, bravest of the brave,

Rescued me, with force and vigour,

Through his prowess and his valour.

A fine knight is that knight, indeed,

Strong in battle, a friend in need.

Yet tis wrong to speak of that same

As you have done; tis not his name.

He was baptised as Gingalain,

His father being Lord Gawain.

He has demanded that I render,

At the court of his King Arthur,

Thanks, for what ne’er can be repaid;

Since twas the king that sent his aid.

For that, he bids me do honour,

To the king, his lord and master.

To this same court he soon returns

If, from God, a safe path he earns,

Though I know not where he is now.

Tis good to meet with you, I avow.

We might ride together, I deem,

For noble lords are you, twould seem.’

They answered: ‘We shall do your will,

If tis in our power to serve you still.’

She reaches London, with the four knights she has met

They thus proceeded on their way.

The queen did much delight betray

At having met the four; those same,

I’ll now recall to you, by name.

Blioblïeris, he made one,

Brave and courteous, scorned by none;

The lord of Saies was another;

The third I need scarce discover,

Orguillous of la Lande was he,

That, o’er many, gained victory.

The fourth was Giflet, son of Do;

All four respected by the foe.

They traversed a wide plain that led,

To England; riding straight ahead.

They followed the road, up and down,

Which led them on to London town,

Where, at present, King Arthur lay.

Before arriving there that day,

The queen had sent servants ahead

To secure lodgings, in her stead.

Richly furnished they were to be.

These servants met her, dutifully,

And led here where she might alight.

Those four, and every other knight,

Dismounted and escorted her,

To a fine tapestried chamber,

Where she might recover and rest.

Then in a costly robe she dressed,

Rich and fine, from the Orient.

Depicted there, for ornament,

Was every creature there may be

Upon the land, or in the sea.

Crocodiles, leopards, and lions,

Flying serpents, fiery dragons,

Eagles, and every other bird,

Parrots, of every kind averred,

All were there portrayed in gold;

A work of art, in every fold.

Of rare sable was her mantle,

Richly wrought, most comfortable;

Of a strange pelt was its border,

A sea creature’s, its sweet odour

Sweeter by far than cinnamon.

God has made no finer a one,

Than that creature; upon the shore

It feeds on herbs, and furthermore

It yields a powerful antidote

Against every poison of note,

And should be on one’s person borne,

To be taken both night and morn;

Its virtues more than I can tell.

Around her waist she wore, as well,

A silken belt in gold brocade;

Most elegantly twas displayed,

And suited that most graceful queen,

Who to advantage now was seen.

If one had searched the world entire

No other maid could one set higher.

There was naught foolish in her speech,

True courtesy her words did teach.

Her looks were full of tenderness.

No other maid did e’er possess

A quarter of the beauty there,

Nor with that lady could compare.

The End of Part V of ‘Le Bel Inconnu’