Renaud de Beaujeu

Le Bel Inconnu (The Fair Unknown)

Part IV

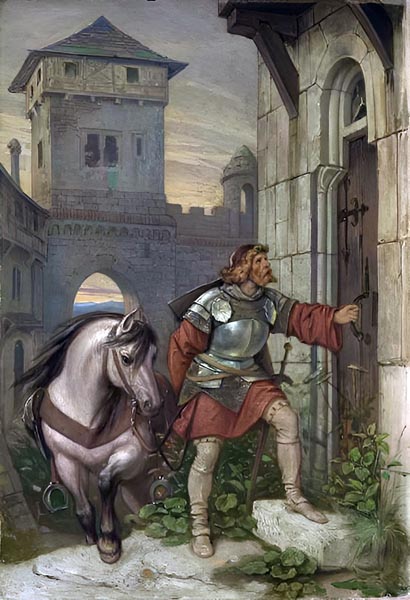

Moritz Ludwig von Schwind (Austrian, 1804-1871)

Picryl

A fine and pleasant hostelry,

I found when we were in this town,

A lodging-place of fair renown,

Where we stabled our horse before.

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2023, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- The Fair Unknown slays the giant knight.

- A serpent appears.

- The Cruel Kiss.

- Gingalain sleeps, then wakes to a lovely sight.

- The maiden, who is Blonde Esmerée, Queen of Wales, tells her tale.

- Gingalain feigns a willingness to wed her, and all the company rejoice.

- The city is cleansed of enchantment.

- Gingalain is asked formally if he will marry the queen.

- He gives an evasive and conditional reply.

- Blonde Esmerée prepares to travel to Arthur’s court.

- Gingalain recalls the Lady of the Isle of Gold.

- He seeks counsel of his squire.

- He executes Robert’s plan.

- And arrives at the citadel of the Isle of Gold.

- He then meets with a hunting party.

- And addresses the Maid of the White Hands.

- He lodges within the city; Robert consoles him.

- Gingalain is tormented by love.

The Fair Unknown slays the giant knight

The duellists were bruised entire,

Their blows so great, dealt with such ire,

Both were exhausted by the fight,

And wounded sorely was each knight.

Great was their woe and weariness,

Yet neither yielded, nonetheless.

The Fair Unknown wielded his blade

And greatly his foe he dismayed,

Sending his helmet through the air,

Who disengaged from the affair.

He sought to flee, his head now bare,

But such a blow our knight dealt there,

The stroke so weighty and so full,

It shattered his enemy’s skull;

His iron cap was split thereby,

The blade it failed thus to defy,

And so, the skull was split in two,

And down he fell, his limbs askew.

A thick and hideous smoke arose

From out the mouth, and from the nose.

The Fair Unknown thrust at the knight

With his sword, dreading the sight;

And, to prove if he lived or no,

Set his hand on the chest below;

All had melted to vile mucus,

Black, foul to smell, and hideous;

All his form it did disfigure,

A witness to his evil nature.

He crossed himself, the Fair Unknown,

And sought his steed, now quite alone,

For, swift, the minstrels fled away:

Each thrusting at their window-bay

With such force, as they did retire,

It shook the palace walls entire;

So violently they fled apace,

The doors banged, rattling in place.

Long, it was, ere the noise abated;

Ill the echoes thus created.

The candles too were swept away;

Upon the hall deep darkness lay.

Indeed, naught could the Unknown see,

Drowned in that vast obscurity.

Scarce could he stand as the place shook,

Forced to the ground as the blows struck

The window frames, the doors as well;

It seemed both earth and heaven fell.

He crossed himself, fearing evil,

Calling on God to keep the Devil

From harming him, then rose again

And forced himself, as if in pain,

To seek the table in empty space,

Groping awhile about the place,

Ere, by chance, he struck the thing

With both his hands, and there did cling.

The sounds, they brought him grave annoy;

All his will did the youth employ

To counter his fear; to God he prayed,

Begging that He might send him aid.

‘Dear Lord,’ he cried, ‘what dare I say?

Tis martyrdom to suffer this way;

This pain it seems will never end,

Nor light return, nor day ascend.

I know I cannot long endure,

Nor can I see the outer door,

Nor find my steed, and yet, I say,

Why do I feel such deep dismay?

Nought is there here that I should fear,

Nor is it right that a chevalier

Should be dismayed, whate’er arise,

If he be armed, in any wise.

Whate’er the ills that might appear,

A man that loves must show no fear.

Should I not bend my every thought

To serving her whom I have sought,

The Lady of the White Hands; she

I must love, not fail, where’er I be.

I would go now, beg her mercy,

Were I but free of this misery;

I shall yet see her, if God please,

And then to serve her never cease.

Already Love grants strength to me;

I dread naught that a man may see.’

A serpent appears

From an opening there shone a light,

A serpent appeared, gleaming bright,

Casting a glow, as from a fire,

Lighting the palace hall entire,

So great the brightness that it shed,

From the place all shadows fled;

No man has ever seen the like;

Its head was raised as if to strike,

Its crimson mouth sent forth a flame,

Great and hideous was that same,

Far wider about its middle

Than is the largest wine barrel.

Its two vast eyes glittered and shone,

As if twin garnets glared upon

The hall; it slid, without a sound,

From out the opening, to the ground.

In length it stretched twenty-four feet;

Its tail coiled thrice and, all complete,

No man had e’er seen a greater.

God ne’er created the colour

Of those scales, or that vile glow;

Gilded the beast seemed below.

It slithered now towards the knight,

Who crossed himself at that foul sight.

The Cruel Kiss

The knight upon the table leant,

The serpent nearing with intent,

And watched that demon as it came,

Ready to lunge at him and maim;

But ere he could draw his sword,

And a proper defence afford,

The monstrous snake inclined its head,

And bowed before the knight instead,

In a gesture of humility,

And so, he sheathed his blade. Said he,

To himself: ‘I may strike that not

That yields itself upon the spot.’

The serpent slid towards the knight

Giving no sign it sought to fight.

He thought to draw his blade, once more,

To strike it as it crossed the floor,

Yet the serpent bowed down again,

Its gesture of submission plain,

And so, the knight deferred the blow.

At once the serpent reared and, lo,

To his mouth it raised its muzzle,

Its every action still a puzzle;

He drew his blade then, with a frown,

Yet once again the snake bowed down,

In a gesture of humility.

He looked it over, cautiously,

Yet struck it not, no move made he,

Nor shifted his gaze, for the knight

Could not but marvel at the sight

Of those crimson jaws glowing bright.

Thus, absorbed in contemplation,

The Unknown maintained his station.

Then the serpent, with a low hiss,

Upon his mouth planted a kiss,

And, having done so, turned away.

The Fair Unknown, his sword in play,

Made as if to strike the creature,

Deeply troubled by its gesture,

But the snake bowed down once more,

Then slid away across the floor,

And once it reached the further wall,

Vanished completely from the hall,

The opening there was swiftly sealed;

No further monster was revealed,

Nor any sign of ill adventure,

Except the hall was dark as ever.

The Unknown mused upon the kiss;

It seemed that all had gone amiss:

‘Lord God above, what should I make

Of this Cruel Kiss? Some foul mistake

It seems, yet one presaging woe.

I am betrayed by this strange foe.

The demon has enchanted me,

Though the kiss I had unwillingly.

Little my life’s worth, now,’ said he.

A voice cried out, then, stridently,

Revealing his lineage to the air,

For none other was listening there,

And that high tone it did maintain:

‘Hark now, son of my lord Gawain,

I know well that this fact is true,

That there is none the like could do,

Performing a great deliverance,

Surviving every circumstance,

The Cruel Kiss, and the combat, thus,

That proved so harsh and perilous.

In this world there exists no knight

So brave, so steadfast, in a fight,

And in all else, such now is plain,

Except yourself and your sire, Gawain.

No other could deliver the maid,

From the great trouble on her laid;

A lady, though in strangest guise,

You have saved; one noble and wise.

Wrongly did King Arthur name you,

The Fair Unknown twas he called you;

You were baptised as Gingalain,

Your father is that same Gawain.

All your history I’ll tell to you:

Blanchemal le Fey gave birth to you.

Armour, I gave you, and your sword,

Ere I sent you to that great Lord,

Arthur, I say, who, for his share,

Granted to you this whole affair,

The boon of rescuing the lady.

You quest ends here: in victory.’

With this the voice faded away,

Having ended all it would say,

While the knight remained, filled with joy,

By the words the voice did employ,

Having revealed, that very same,

Who his sire was, and his own name.

And so, my tale, to speak aright,

Is of Gingalain, the valiant knight;

A tale that, sung on every shore,

Throughout the ages shall endure.

Gingalain sleeps, then wakes to a lovely sight

Gingalain was full wearied now.

Upon the table his head did bow.

With his shield beneath his head,

He lay there, sleeping like the dead.

So weary was he, twas no joke;

He slept long, yet at last awoke,

And he did so with great delight

For all the hall was filled with light.

A lady stood at his head, alone.

More beautiful than any known,

Such was that lovely woman there,

Her colour fresh beyond compare.

There’s ne’er a clerk could portray

Her mouth, her lips; no, none, I say,

Owns the power to describe her.

She was a work wrought by Nature;

And none so lovely had She made,

In eyes and lips, in form displayed,

Beauty that every eye commands,

Except for her of the White Hands,

Whom no maid alive could equal,

At whose beauty all did marvel.

And yet, I dare affirm this maid

Lacked in naught, if all be weighed.

Nature had wrought her every part

Forming her with consummate art.

She wore a mantle of pure green,

And none finer was ever seen;

Rich was that mantle, and most fair.

Two sable tassels, made with care,

Fastened it; its collar was fine,

White ermine worked in rare design.

The cloth of which that cape was made,

Both quality and strength displayed,

And it was so skilfully wrought,

It could not be damaged by aught;

Twas the work of a Fey, and she

Dwelt on an isle in the Frozen Sea.

Of the same was the tunic made,

In which the maiden was arrayed,

Of rich worth, artfully wrought,

Trimmed with ermine, fit for a court.

Five ounces of gold, of a surety,

Were used in its embroidery,

And four ounces of silver net;

With many a jargoon it was set,

While other stones of great power,

O’er the gold, made up its dower.

The maiden, who is Blonde Esmerée, Queen of Wales, tells her tale

Gingalain, on seeing her there,

Bowed his head, and gave her fair

Greeting, at which she did the same:

‘Sir, upon me you now have claim,

Said the maid, ‘and with good reason,

Through freeing me from my prison,

That serpent-form breathing fire.

My dear lord, I am yours entire.

Daughter am I of King Gringras,

Whom Death has reft from me, alas.

And I am that same lady who

Sent the maiden, that follows you,

To King Arthur’s noble court,

Where his aid for me she sought.

You have delivered me from woe;

Full many a week have I grieved so,

In that form being forced to dwell;

How it came about, I shall tell.

Once Death took my father from me,

Two months had passed, twas nigh-on three,

When to court came an enchanter,

Accompanied by his brother.

As two minstrels they presented,

And that day the pair enchanted

All those dwelling in the city,

A good five thousand; completely

Maddening our folk, one and all.

The high turrets they made to fall,

Those two, and brought the belltowers low,

And, a marvel, the earth below

Split side to side and flung on high

Great boulders soaring to the sky,

That struck upon one another,

Then dropped to the ground together.

Sir, it seemed that all things fell,

The heavens and the earth as well.

So great was the enchanters’ power

The folk all fled, that very hour;

None could oppose them, certainly.

And then they sought to enchant me:

They made me touch a certain book,

And, lo, a serpent’s form I took.

Long did they keep me in that state.

When they would speak with me, of late,

They came to me, increased my torment

By lifting that vile enchantment;

Mabon who held the most power,

Addressed me for many an hour,

Urging me to grant him my heart.

Seeking to wed me; all his art,

And fine speeches he did employ,

Claiming he’d free me from annoy,

While, if I’d not be his lover,

I would remain a serpent ever;

Here I would suffer endlessly,

For none would come to set me free,

Except the most courageous knight

Of Arthur’s court, a man of might;

And now I know it to be true,

For none are mightier than you,

Unless it be your sire, Gawain,

That every virtue doth maintain.

The crowd of minstrels whom you saw

After you passed the palace door,

Were all part of the enchantment,

Conjured to seem malevolent.

The knight that you first fought, that same

Was Evrains the Cruel by name;

The other was that vile Mabon,

Who the enchantment cast upon

Myself; and when you struck him dead

You ended all my pain and dread,

For all their work was then undone,

And their enchantments, every one.

The serpent that then kissed your lips

Was but myself, in dark eclipse,

She whom your treated with respect,

And whose kiss you did not reject.

No other way but through that deed,

Through kissing you, could I be freed.

All I have said, without exception,

Is true; herein lies no deception.

Now I tell you another thing,

Of all my realm you shall be king.

Wales is the name of my country,

Whose rulership devolved on me,

While this city you came upon,

Was called, by all folk, Senaudon,

But, once Mabon the place did maim,

The Ruined City was its name.

It is my capital, and three

Bold kings owe it their fealty.

Great is the realm, and the land

Is rich indeed, that you’ll command,

For, I pray you, since tis your right,

Having thus conquered all, sir knight,

To take me for your wife, and so,

As our true king be crowned also,

For they know, all in this castle,

How you’ve saved me from dire peril.’

Gingalain feigns a willingness to wed her, and all the company rejoice

He knew how to feign agreement,

‘Fair maid, I willingly consent

To wed you, if Arthur agrees,

For ever that king I must please.

I shall go and ask him, readily,

For it would be but villainy

To marry without permission.

I would not be in that position.

Rather I shall seek his counsel,

And only wed if it be well,

If it be so, upon my life,

I’ll willingly take you to wife.’

Thus, the marriage he delayed,

While also appeasing the maid,

Who thought him to be her lover.

He turned to see Hélie enter

With Lanpars accompanying;

Then the rest of his following,

Robert his squire, behind the pair,

With the dwarf; joy all did share,

The four all smiles on entering.

Conceive then the loud rejoicing!

All gathered, once more, together,

They warmly embraced each other,

Not a one there but felt delight,

And clasped the victorious knight.

Hélie and Lanpars, of those four,

Joyed to see their mistress once more,

While Robert much relieved appeared

On seeing him for whom he’d feared.

When all had expressed their pleasure,

The four turned, in equal measure,

To removing his armour apace.

Robert the helmet did unlace,

While, once his armour was removed,

Cut and bruised his body proved,

For he’d received so many blows,

From his crown down to his toes,

That he was bleeding everywhere,

Covered in wounds from that affair.

When they’d bathed his weary flesh clean,

They bandaged him and, having seen

To all, led him to a chamber

Where were garments without number;

Silks and brocades they did unfold,

Adorned with Alexandrine gold,

And fur-trimmed mantles, vair and grey;

Gold and silver about them lay.

That chamber was fit for a king,

And the bed a most regal thing.

The city is cleansed of enchantment

Now it behoves me to relate,

Though briefly, lest I tempt fate,

(For naught here should be forgot,

And twould go ill if I did not)

Succinctly then, within reason,

How ever great lord and baron,

Abbot, and bishop, and prince too,

Of that Welsh realm, arrived to view

The knight who’d saved their lady,

Once they’d all heard the story

Of how the rescue came about.

For, to allay their every doubt,

None delayed but swiftly sought

To share the joy of it, at court.

All the people now gathered there,

At the news of that great affair,

Hastening to see their lady,

Great was the crowd now, and noisy.

Archbishops, bishops, abbots, all

The clergy gathered at the call,

And through the streets made progression

Chanting, bearing, in procession,

Crosses, censers, reliquaries,

Tall banners, and rich draperies;

Many a relic they did bear,

As the bells sounded everywhere.

The city streets, as they progressed,

With holy water, too, they blessed.

Those friends of God, those saintly men,

Blessed the city, and cried ‘Amen’.

Once Mass had been celebrated

In the largest church, they vacated

That place and at the citadel,

Prayed again that all might be well,

Springling holy water once more

That all might be both cleansed and pure,

And from every enchantment free

Produced by Mabon’s sorcery.

Then to the palace they returned,

Having fresh right of entry earned.

Once the palace was blessed, delight

Overcame them all, at the sight,

Of their lady, whom, to their cost,

They had considered all but lost.

Great was the joy among them then

At viewing their queen once again,

She of the free and open air,

Her manner ever sweet and fair.

Great was the love her lords did show,

For her absence had brought them woe,

She who was so noble and wise,

While she spoke lovingly likewise:

‘My lords,’ she said, ‘come list to me;

What shall I do for such as he,

Who has endured for me such pain,

No knight finer from here to Maine?

You all must show him honour,

For he’s a man of true valour.

Noble is he, this Gingalain,

Whose sire is the faithful Gawain

Nephew to the great King Arthur

Who rules as far as Spain or farther.

Advise me now how I should show

The greatness of the debt I owe?’

All the lords called out, as one:

‘Noble lady, let this be done;

Accept him as your spouse; indeed,

He saved your life by his true deed.

We wish him now to be our lord;

None better could this world afford.’

‘My lords, if it please him,’ said she,

‘Then more than happy shall I be;

What pleases him, needs no amends,

Now go and speak to him, my friends:

If he will wed me, have no fear;

I shall love him, and hold him dear.’

Three noble Dukes swift departed,

To speak to him; with them started

Four Counts whom she called upon;

Lanpars, with Hélie, followed on;

While three abbots, and bishops two,

That brave company did pursue.

Gingalain is asked formally if he will marry the queen

They came to where Gingalain lay,

At his side, Robert, night and day,

And, on entering the chamber,

Greeted the brave knight together.

To their greeting he then replied;

Courtesy ruled on either side.

He raised himself to listen then,

Feigning to be nigh sound again,

While they sat down, about the bed.

A lord the conversation led,

As emissary, having been

Selected to speak for the queen.

‘Good sir, but hear me out,’ said he,

‘My lady, and all her company,

Do, through myself, a thing offer

That will bring to you much honour.

Accept without hesitation,

Delay, or procrastination,

Our lady’s hand in marriage now,

And dukes, princes, and barons, vow

That they’ll obey you loyally,

Without treason or villainy.

All live but to do your pleasure,

To serve you, and show you honour.

Wealthy, powerful, you shall be,

And not one baron shall you see,

In all this land, that will not do

Whatever you command him to.

So, take our lady for your wife,

Who’ll devote to you her life,

For great the honour you shall know;

All our folk pray you will do so,

Trusting to you the realm entire;

That you should rule is their desire.

All of the land you shall possess,

For they will grant you nothing less

Than everything, forest and plain,

The rivers, with all they contain,

And gyrfalcons and sparrowhawks,

And peregrines, and fierce goshawks,

And fine steeds, and silver and gold

That you may give to those you hold

In affection, that honour you,

And so, reward all who prove true.

And when you ride to the tourney,

The finest arms you will carry,

And wear the armour that best suits

A royal knight in such pursuits,

And by your side many a knight

Will go well-armed to the fight.

For you may ever rest secure

In their support, in peace and war.

Now grant me, good sir, your reply

So, I may repeat it, by and by,

To the queen, to whom I am bound;

She loves you with a love profound.’

He gives an evasive and conditional reply

This answer came from Gingalain,

Who yet could scarce his strength maintain,

And was most pale: ‘Sir, I render,

Thanks to you, and every other,

For all that I have heard you say.

I shall not hide from you, this day,

That I would gladly marry so,

But first to Britain I must go,

And there beg leave of King Arthur,

Otherwise, I may not wed her;

For if to this the king says nay,

It would prove but folly, I say,

To marry without his consent.

Tis as his envoy he has sent

His nephew; he must needs agree

To my marriage; for he chose me,

Amidst his court, knowing me not,

And ne’er shall that boon be forgot.

I pray my lady will thank the king,

For the succour that I could bring.

Through him she’s delivered from woe,

And to his court now she should go,

There to do King Arthur honour,

For the grace bestowed upon her.

By his command have I wrought all,

And so, to him the rule should fall.

A noble boon he granted me,

Adding me to his company.

In good faith I ask that the queen

At Arthur’s court should soon be seen,

Her loyalty, there, to tender,

And her deepest thanks to render.

Honour and favour she shall gain,

And, if a husband she’d obtain,

Then I shall take good counsel there,

And, by his will, seal the affair.

And so, indeed, tis my counsel,

That she prepares her apparel

To visit his court, in rich guise,

With many a nobleman likewise.

And, if she’ll journey to his court,

Let her do so swiftly, in short.’

Blonde Esmerée prepares to travel to Arthur’s court

All this the lady agreed to do,

All Gingalain had asked her to:

Thus, she would go to Arthur’s court,

And thank him for the aid she’d sought.

She set the date when she would go:

In a mere seven days or so.

Once the word had gone to and fro,

The emissaries prepared also,

And took their leave of Gingalain,

Whom they left feeble and in pain,

Commending him to God’s good care.

To him the surgeons did repair,

Sent by the queen to tend the knight,

For he was precious in her sight.

Throughout the length of his stay

She honoured him in every way.

Before the lady left that place

For Arthur’s court, there came apace

To the city, those folk once more,

Who had paid her fealty before,

At least those who were safe and sound,

And still in riches did yet abound,

And they brought her silver and gold.

Shall not the tale be swiftly told?

All the city was soon restored,

And welcomed there many a lord.

The queen summoned a rich escort,

To go with her to Arthur’s court.

In her chamber she did address

The clothes she’d wear, and then no less

Attention gave to her equipage;

Honour, she’d seek, at every stage

Of that journey; her company

Held thirty cities in fealty.

Blonde Esmerée, which was the name

That queen had been granted by fame,

Prepared to wed, filled with desire

For one who’d won her heart entire.

Gingalain recalls the Lady of the Isle of Gold

While he waited for the lady,

The knight rested in the city.

After a fortnight he was healed,

Yet fate another ill revealed.

Love possessed his every thought,

A whirlwind of unrest it brought.

He who’d never sighed with love,

The worst of sufferers did prove,

All for the Maid with the White Hands;

He was made pale by love’s demands.

Since he had left the Isle of Gold

Of which I previously told,

He had not forgotten the maid;

Not once did the memory fade,

Of going without taking leave,

Of having laboured to deceive.

From the dawning of that day,

His heart was sore wounded, I say,

And, since then, he’d longed for her so,

That heart had redoubled its woe.

The joy seemed double he had known,

And the signs of love she’d shown,

And many a time it seemed he saw

Her face in dream as, once before,

It had bent low above his head,

As he lay there upon the bed

In the palace, in that chamber.

A cape her shoulders scant cover,

She bare-footed in her chemise,

In such semblance as could but please,

Appearing as when she had come

To his bed, and he was struck dumb.

Now the thought his mind tormented;

On a day, he thus lamented:

‘Alas, I know not what to do!

What is this pain that hurts anew?

It must be love, or so it seems,

For I have heard: not as in dreams

A lovely woman should be loved.

The thing is true, for now tis proved

By my feelings for that fair maid

For whom I die, a man dismayed.

Great honour she did me, that fey,

Whom I fled at the break of day;

Twould have been better far to die

Than, like a villain, thus to fly

From the one that I so desire.

Now I repent that deed so dire.

Now my whole heart is full of woe.

I scarce dare ask, Lord, here below,

For Your pardon; yet what to do?

I die of love, that much is true.

For there is none can aid my plight,

Nor can I now forgive my flight.

Rather, a sad death I must die,

No ease I win, but only sigh.

Yet, be silent! Tis ill you speak!

Go now to her, and mercy seek;

Grant not your heart to suffer so,

Until you lack the means to go,

Through enduring the pain too long.

Depart now while yet you are strong,

Or indeed you will surely die,

For no good will be got thereby.

There’s no escaping such desire.’

With that thought, he summoned his squire.

He seeks counsel of his squire

His advice he sorely needed;

Any counsel would be heeded.

The squire to his lord did go,

Who told him briefly of his woe.

‘Robert,’ he said, ‘now counsel me,

For I suffer most wondrously;

I cannot sleep or even rest,

Such the thoughts that my mind invest,

Thoughts of her that I did behold

When visiting the Isle of Gold.

She torments me, death lies therein;

She of the White Hands I must win,

For I desire her wondrously;

Oft love stirs me, and will slay me.

Love brings me anguish without end;

Long have I suffered so, my friend.

What shall I do, since you are wise?

Till now such ills I did despise,

But she will prove the death of me.’

Said Robert: ‘You make mock of me!

Whene’er I spoke to you of love,

Ever the jester you did prove.’

‘This is no jest!’ cried Gingalain,

‘If ever I mocked Amor, tis plain,

He is wreaking his vengeance now;

His darts slay me; neath them I bow.’

Robert replied: ‘Praise to the maid,

She that has, thus, your heart waylaid!

Though I know naught of chivalry,

He lacks valour, it seems to me,

That never once desires to love,

Ere his heart too old doth prove;

Nor should one grant that man a prize,

Who ne’er for Amor lives and dies.

Sire, be not dismayed if Amor

Had made you subject to his law;

He loves brave fellows, for his part;

Slow to strike rascals with his dart.

For that reason, be not dismayed;

Traverse Love’s passage, unafraid,

And I’ll counsel you, man to man,

In all, as wisely as I can.

Now, if you’ll listen to me closely,

When the queen is good and ready,

To depart for King Arthur’s court,

And to her the mules are brought,

Her palfrey, and her other steeds,

And with the royal robes she needs

You see them loaded, and with gold

As much as the panniers will hold,

Let her depart whene’er she will,

But you, keep to your lodgings still,

And arm yourself, in privacy,

Then take to the road, instantly.

When you re-join the queen that day,

To whom this realm honour doth pay,

Speak sweetly, and her ear command

And then your leave of her demand.

Say you’ll go with her no further,

But must go to meet another,

With whom you have business to do,

And cannot linger, but will pursue

The matter as swiftly as you can;

To meet her at court is your plan.

And when you have won her leave,

Ride as fast as man can conceive;

Return, and we will make our way,

Galloping hard, both night and day,

Till we come to the Isle of Gold

Where your love you may behold.’

‘Fair friend, what’s this you say to me?

Dare I own the effrontery,

To return to that lovely maid,

She that I fled, and so betrayed?’

Robert replied: ‘Why yes, you may,

And tell her of your deep dismay.

He who seeks not mercy to claim,

He must forever bear the blame;

He who from great pain doth suffer

Must show his wound to the healer.

“He,’ folk say, “that feels great hunger,

Must seek bread, if he’d live longer”.

How, indeed, can she know your heart,

If you tell her not, nor play your part?

You must tell her how you suffer

From the love you possess for her.

Forgiveness you will swiftly find;

After tears, joy’s not far behind.’

Gingalain said: ‘Tis long to wait;

Before the queen departs in state,

Three days at least must yet pass by,

And yet, ere they do, I must die,

If I ease not my suffering here.’

‘Sire, hide your heart, and own no fear.

Let naught the loving mind dismay,

For you will win her heart, I say.’

He executes Robert’s plan

So Gingalain endured three days,

While suffering Love’s ills always,

And then a fourth, until, at morn,

At the very first break of dawn,

Upon the fifth, Blonde Esmerée

Prepared to set out on her way,

And with no small host before her;

Each noble astride his charger.

Next her companions rode on,

With a peregrine, or gyrfalcon,

A goshawk or a sparrowhawk

Upon their fists; at a slow walk,

The beasts of burden came after,

With many a trunk and coffer,

Destined to show the wealth of Wales,

Gold and silver cups, rich bales

Of cloth, and spoons and bowls of gold,

From all her treasury did hold.

Then the queen mounted her steed;

Great was her own escort indeed,

A hundred knights in company,

And all equipped most sumptuously.

Thus, they issued from Senaudon,

The queen and her lords, every one.

With them their spare horses they led,

Fine palfreys, and chargers pure bred.

They issued forth from the city,

While Gingalain armed, silently.

As the queen set out, she sought

For Gingalain amidst her court,

But no trace of him could she see.

‘The Lord help me, my lords,’ said she,

Where is my friend, and spouse to be?’

None about her knew, or could say,

She halted, questioning them alway.

At last, looking towards the city,

They saw him armed, riding swiftly,

With his squire Robert at his side.

They gazed, their eyes open full wide,

Wondering why he should arm that day;

Towards the queen he made his way.

When Blonde Esmerée saw him there

She turned her steed, at him did stare,

Then questioned the knight, at some length;

What need for this display of strength?

Why arm, thus? What had he to say?

Gingalain answered, straight away:

‘My friend, I cannot go with you;

There’s a matter I must pursue.

Most urgent business it is indeed.

But, when all is done and agreed,

I’ll follow you at once to court,

Nor shall I be delayed by aught.

Greet King Arthur there, for me,

And grant me leave, willingly.’

Said the queen: ‘Have mercy, sire!

You doom me to sorrow entire.’

‘Lady, to God, I commend you;

Go I must; may He defend you,

You, and all your fair company.’

He parted from them instantly,

Though not without a deal of pain,

And took to his own road again.

They grieved as the knight turned to go,

But none felt such a weight of woe

As did the queen, who paled at this,

For parting so was ne’er her wish,

And oft she shed a tear and sighed,

Saddened, as onwards she did ride,

Dismayed was she, and troubled so,

Yet nonetheless the maid did go

Upon her way to Arthur’s court,

Though mournful, and alive to naught.

Shortly I will tell the story

Of the queen’s onward journey,

But first I’ll tell of Gingalain,

Who galloped swiftly o’er the plain.

The Lady of the White Hands, he,

Most anxiously, desired to see.

The sight of her was his great need,

And so, the road seemed long indeed.

And arrives at the citadel of the Isle of Gold

All that day till the evening hours

He journeyed, ere he saw the towers

Of the keep of the Isle of Gold,

Having ridden thirty leagues all told.

On the outworks he cast his eye,

The walls before him strong and high.

And quite enough to give one pause.

If the folk as far as Limours

Had besieged it for thirty years

Their toil had but ended in tears.

Great was the beauty of that place,

Though, as to that, I seek your grace,

Having described it all, elsewhere.

To be brief, there was none so fair.

Gingalain, on viewing that sight,

Felt his heart swelling with delight.

He had long held the keep in view,

And now came to its walls anew;

All about that place lay the sea.

Towards the Isle of Gold, rode he,

That fine and wave-begirt stronghold.

And there a fair host did behold.

He then meets with a hunting party

As towards the group he did draw,

Ladies, knights, young maidens, he saw,

Bearing sparrowhawks, fierce merlins,

Tercels, goshawks, and peregrines,

Since a-hunting that host did go.

His joy he could not help but show,

For his beloved he could see

Amidst that noble company;

Upon a white palfrey she sat,

Ambling slowly, though, as to that,

Its white showed spots of black also;

O’er its neck a gold mane did flow.

She was the Maid of the White Hands;

The harness straps, in Moorish lands

Were wrought, with artistry untold,

Of a hundred little scales of gold;

Thus, as the palfrey ambled by,

They tinkled softly neath the sky,

More sweetly than a harp or rote.

None ever heard a sweeter note

From the rebec or the vielle.

What can one say of the saddle

Upon which the fair lady sat?

An Irish master had wrought that,

So fine, and of such value too,

That to describe it’s hard to do;

It was made of gold and crystal,

All encrusted with enamel.

And addresses the Maid of the White Hands

The maid was fair and much esteemed,

Her unbound hair behind her streamed

As she rode; she’d doffed her mantle,

And had taken to the saddle

In a riding coat trimmed with gold,

The day’s weather not proving cold;

Fine was the cloth, embroidered o’er.

A little hunting cap she wore,

To hide her pale brow from the sun;

Many-coloured, twas richly done,

In green and brown, and blue, and white,

Shading her visage from the light,

While birds in gold were there portrayed;

A thing of worth, skilfully made.

Her hair flowed free, as I have told,

Gleaming more brightly than pure gold;

Loosely it flowed behind her head,

Looped by a single golden thread.

With shapely hips, a slender waist,

Her whole form was by beauty graced.

Long sleeves her hands revealed below,

Whiter than hawthorn flowers that blow.

What could any bold clerk say more

Of that maid than I’ve said before,

Other than this: no maid wiser

Dwelt in this world, nor one nobler

Of heart; none fairer e’er was known;

Nature wrought her to shine alone.

The sparrowhawk on her wrist, she bore,

Moulted thrice, the maid did adore.

Gingalain knew her from afar,

For she shone bright as any star.

He doffed his helm, and bared his face,

And then saluted her, with grace:

‘Lady,’ said he, ‘I’d speak with you,

That my inmost thoughts you may view,

If you were pleased to turn aside.’

‘May God defend us!’ she replied.

Wishing to tell her all, the knight

Now placed himself upon her right.

‘Lady, come, lend to me an ear,

Joyful am I to see you here;

That you slay me, I cannot hide.

Mercy, I beg of you!’ he cried.

‘For God’s sake take pity on me,

Relieve my suffering, and be

No crueller towards me today,

On account of aught I may say.

For Love will not let me alone

Till all the truth to you I own;

Ashamed am I, though all in vain;

Love doth assault me, and constrain

My heart, and leads me as he will.

Lady you may be sure, until

I die, your prisoner I shall be,

To be hung, burnt, slain or set free.

My feelings I cannot conceal.

Whether you list to my appeal

Or no, the power is wholly yours;

My life’s now subject to your laws.’

‘Who may you be?’ archly, she asked.

‘Lady,’ said he,’ a true knight, tasked

With serving you, since first he saw

Your face, and then viewed it no more.’

‘And should I know you then?’ said she.

‘Lady, I shared your company,

When I lodged in your palace here,

Ere I was forced to leave, I fear,

To aid the daughter of King Gringras;

On which quest I went forth, alas.

Twas then your hand you offered me,

Though I departed, foolishly,

That I might bring another aid.

Since then, my love for you, fair maid,

Has oft brought torment to my heart;

Scant repose have I, for my part.’

‘What!’ she cried, ‘are you not that man

Who behaved as ill as any can,

And my feelings did so outrage,

Scorning myself, my lineage,

By fleeing from the keep at dawn,

Without taking leave, one ill morn?

And yet I did you great honour,

Myself, my realm, love forever

Offering you, with all my heart.

Twas a vile insult on your part!

Think not lightly of that affair.

If I’d not loved you, for my share,

I’d have treated you as vilely,

And punished you, without mercy,

For the shame you brought upon me

Through offending me so deeply.

Your error leaves you in danger.

A duke, a prince, or some other

Lord or knight, of this fair country,

Will prove so keen to act for me,

That, whether it be right or wrong,

He’ll strike you dead before too long,

Should he discover where you are.

You’re the maddest of all, by far,

Who dare to return to this court,

And seek to speak to me of aught.

I loved you deeply; which I recalled

Full oft, and though, in truth, appalled,

Restrained myself, sought not your shame,

Recalled that love and, in Love’s name,

Still loved no other man but you;

And had I not, then vengeance true

I had wrought; that alone is why

I chose that you should live, say I.

Yet I warn you that, in no wise,

Shall I be thus taken by surprise,

Again, and set my heart on you;

But shall to my own self be true.’

Hearing her speak so, Gingalain

Grew pale; his face revealed his pain,

His visage dimmed, his eyes less bright,

His brow, and cheeks, and lips, showed white:

Feebly, he said: ‘What? Is it thus?

Will you be less than generous,

And show no mercy? Then I must die.

No longer can I endure, say I.

No comfort is there now for me,

You render death a certainty.

On you a weight of sin must fall

For wounding me beyond recall.

Since no escape now can I see,

Nor ease to end my misery,

I’ll end my life here in this land.

You are my death; for, understand,

Such is my need to have you nigh,

That in your realm I seek to die.

Little I care you wield the knife,

Tis through you, I forgo this life.’

He lodges within the city; Robert consoles him

They’d talked so long in this manner,

That they reached the city together.

When they came to the portal, she

Rode within, while her company

Of knights and ladies did the same;

There entered many a fair dame.

Dismounting then, beyond the wall,

They sought their dwellings one and all.

Meanwhile, our hero, Gingalain,

Gazed upon the palace in vain.

Not a word to him did any say;

A foolish part was his to play.

He knew not what he ought to do,

Left there, without an end in view.

‘Robert, where shall we go?’ said he.

‘The day goes ill, as you can see;

And here are we, without a plan.

Go find us lodgings, if you can.’

Robert replied: ‘Now list to me:

A fine and pleasant hostelry,

I found when we were in this town,

A lodging-place of fair renown,

Where we stabled our horse before.

The host was courteous; to be sure,

Nor will we lack for decent fare.

Said Gingalain: ‘Then lead us there.’

Onwards rode the squire and knight,

And were welcomed, with delight,

At that hostelry; be not surprised,

For Robert was soon recognised;

They lodged in comfort there, that night,

Though his lord shared not his delight,

Amor had caught him in his net,

And he did naught but grieve and fret,

Pained by love for that fair lady.

Thus, to his squire, he said, sadly:

‘Robert, what is to do? Alas,

Shortly the gates of death I’ll pass;

Amor but wishes to see me die.’

This was his loyal squire’s reply:

‘What did the lady say to you,

When you her lovely face did view?’

‘Truly, no comfort found I there;

It seems that death must be my share.

Indeed, she said to me, that same,

That she’d have brought on me great shame,

If, that is, she’d not, for her part,

Once loved me, and with all her heart.

She thought of it oft, she did own;

What restrained her, was that alone.’

‘Sire,’ said Robert, ‘be not dismayed,

For here another tale’s conveyed,

In her saying she once loved you;

Love may yet be kindled anew.

I’d take solace from her reply;

Her love may waken, by and by.

Her response bodes well for you.

Fret not, but keep your aim in view,

I deem the words she did employ

Enough to fill your heart with joy.

Could I speak to her, tis my view

She’d not be slow to pardon you.’

Gingalain is tormented by love

So Gingalain, for many a day,

Waited, though suffering alway,

Hoping to have sight of his love.

Ever empty his hopes did prove;

He saw her not, whate’er he tried.

The little he owned he applied

To the problem, all he possessed.

Many a one there he addressed,

Offering gifts to any that might

Accept such things to aid a knight.

He gave, traded, borrowed, and spent,

Till all was gone, with that one intent.

For two full weeks he laboured so;

And from him all his wealth did flow;

All his equipment too he sold.

Truly Love had him in his hold,

Such that he neither slept nor ate;

An ill port had he reached of late.

Love governed one so oppressed

That though he pondered without rest

On some means of speaking to her,

None could he find, that sad lover.

Of Love, that all his thoughts constrained,

Night and day our hero complained.

Love it was denied him repose;

Woeful thoughts did his mind enclose.

He neither ate nor slept, for still

He was led about, at Love’s will.

Greatly was he anguished thereby;

On his bed Gingalain did lie,

Thinking himself about to die.

Unable to rise, he could but sigh,

Tremble, and shake, and weep ever.

Greatly did Love’s martyr suffer.

He tossed and turned, all day and night,

Lay on his left side, then his right,

In the manner of every lover.

Ill the foe that I did discover,

In the one I’ve sought to embrace.

From the moment I saw her face,

My heart was never free of her,

Nor can it be, although I suffer.

Though my death she seeks, endlessly,

More than aught is she worth to me.

Never have I done her a wrong,

Except in loving her too long,

And yet, through that, she works me ill,

In that my heart must seek her still,

That finds her here within each day.

Listen, then, to what I shall say

Of Gingalain, dying, through Love,

That his enemy, thus, did prove.

The End of Part IV of ‘Le Bel Inconnu’