Théophile Gautier

Mademoiselle de Maupin

Part V: Chapters 12 to 14

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter 12: Théodore to Graciosa.

- Chapter 13: D’Albert to Théodore.

- Chapter 14: Théodore to Graciosa.

Chapter 12: Théodore to Graciosa

I promised you the continuation of my adventures; but in truth I am so lazy where writing is concerned that only the fact that I indeed love you like the apple of my eye, and know your curiosity to be greater than that of Eve or Psyche, prompts me to sit at a table in front of a large sheet of completely white paper that must be darkened, and a well of ink deeper than the sea each drop of which must turn into a thought, or into something resembling one at least, rather than mounting my horse and travelling, at full gallop, the two hundred long miles that separate us, so I might relate to you in person all that I am going to string together imperceptibly, so as not frighten myself by contemplating the prodigious extent of my picaresque odyssey.

Two hundred miles! To think there is all that space between myself and the person I love best in all the world! I feel like tearing up my letter, and having my horse saddled yet. But I forget: in the clothes I am wearing, I could not approach you, and resume the familiar life we led together when we were naive and innocent little girls: if ever I wear skirts again, that will assuredly be why.

I left you, I believe, at my point of departure from the inn where I spent such a strange night, and where my virtue almost suffered shipwreck before leaving port. We all left together, riding in the same direction. My companions were very ecstatic about the beauty of my mare, who is indeed a thoroughbred and one of the best racers there is; this elevated me at least half a yard in their esteem, for to my own merit was added all the merit of my mount.

However, they seemed to fear that she was too frisky and too spirited for me. I told them that they should calm their fears, and, to show them that there was no danger, I made her curvet several times, then leap a fairly high barrier, after which I broke into a gallop.

The troop tried in vain to follow me; I gripped the bridle when I was far enough away, and returned at full speed to join them. As I drew near, I curbed my mare, and stopped her short: which, as you may know, demands real strength.

From esteem they passed, without transition, to the deepest respect. They could scarcely believe that a lad just out of college, could prove such a good horseman. This discovery served me more than if they had recognised in me all the theological and cardinal virtues; instead of treating me like a mere youth, they spoke to me in a tone of obsequious familiarity that pleased me.

In doffing female dress, I had not renounced my pride: no longer being a woman, I wished to be a man complete, and not rest content with mere external display. I was determined to achieve as a cavalier the success to which I could no longer aspire as a woman. What worried me most was lacking the courage, perhaps, to do so; for courage and skill in bodily exercise are the means by which a man most easily establishes his reputation. It is not that I am a timid woman, full of the imbecilic pusillanimity that one sees in many; but from there to the careless and ferocious brutality which men glory in there is still a long way, and my intention was now to become a little swashbuckler, a throat-cutter like these gentlemen with their fine airs, in order to put myself on a good footing with the world, and enjoy all the advantages of my metamorphosis. I found later that nothing could be easier and that the recipe is a very simple one.

I will not tell you, as is customary among travellers, that I journeyed so many miles on such and such a day, that I passed from this place to that other, that the roast I ate at the White Horse, or the Cross Inn, was raw or burnt; that the wine was sour, and the bed I slept in had curtains adorned with figures or flowers: these are very important details and it is good to preserve them for posterity; but posterity will have to do without them on this occasion and you will have to resign yourself to not knowing how many dishes my dinner consisted of, and whether I slept well or badly during the course of my travels. Nor will I give you an exact description of the various landscapes, the wheat-fields and forests, the varied crops, or the hill-slopes burdened with hamlets, that successively passed before my eyes: they are easy to imagine; take a little earth, plant a few trees, and a few blades of grass, daub a little patch of sky as a backcloth, either greyish or pale blue, and you will have a more than adequate idea of the shifting background against which our little caravan was highlighted. If, in my first letter, I indulged in some details of this kind, pray excuse me, I will not do so again. As I had never before journeyed beyond my garden, the slightest thing seemed to me of enormous importance.

One of the riders, the companion who had occupied that bed, the one I had almost tugged by the sleeve on that memorable night whose anguish I described to you at length, acquired a great liking for me, and rode his horse beside me the whole time.

With the one exception, that I would not have wished to take him as a lover though he brought me the most beautiful crown in the world, he did not otherwise displease me; he was educated, and lacked neither intelligence nor good humour: yet, when he spoke of women, it was with a tone of contempt and irony for which I would have very willingly torn the eyes from his head, especially since, ignoring his exaggerations, there was much harsh truth in what he said, the justice of which my manly dress forced me to recognise.

He invited me so insistently, on so many occasions, to visit one of his sisters, a widow who was nearing the end of her period of mourning, and who at that moment dwelt in an old château with one of her aunts, that I could not refuse. I raised a few objections, though merely formal ones, since in truth it was much the same to me whether I went there or anywhere else, and since I could just as readily achieve my goal in that way as any other; and, as he told me that I would certainly disoblige him greatly if I did not grant him my presence for at least a fortnight, I replied that I was willing, and the thing was settled.

At a fork in the road, my companion, pointing to the right leg of this natural Y, said: — ‘Here is our road.’ The others shook hands with us, and turned to the left.

After a few hours at walking pace, we arrived at our destination. A wide ditch which, instead of water, was filled with abundant and bushy vegetation, separated the park from the highway; the sides were of cut stone; and, in the interstices, gigantic artichokes and iron thistles bristled, seeming to have grown naturally between the disjointed blocks of the walls: a small bridge, with a single arch, crossed this dry canal, and allowed access to the gate.

A tall avenue of elms, rounded to a barrel shape, and trimmed in the old fashion, first presented itself; and, after following it for some time, we emerged at a sort of circle.

The elm-trees looked old-fashioned rather than merely old; they appeared to have wigs and be powdered white; and had only a small tuft of foliage at their crowns; all the rest was carefully pruned, so that one would have taken them for enormous plumes planted in the ground at intervals.

After crossing the circle, covered with fine grass carefully flattened with a roller, it was necessary to pass through a curious avenue of foliage adorned with vases, pyramids, and columns of rustic order, all clipped with great care using billhooks and shears, from an enormous series of box trees. One sometimes caught various glimpses, to right and left, of a half-ruined castle of rocks, or the moss-eaten staircase of a dried-up waterfall, or else a vase, or statues of nymphs and shepherds, with broken noses and fingers, and a few pigeons perched on their shoulders and heads.

A large parterre, designed in the French style, stretched out in front of the château; all its compartments were laid out with most rigorous symmetry, employing boxwood and holly; it looked as much ornate carpet as garden: large flowers, in their ballroom finery, of majestic bearing and serene mien, like duchesses preparing to dance a minuet, bowed their heads to you as you passed. Others, apparently less polite, stood stiff and motionless, like dowagers weaving their tapestry. Shrubs, in every possible shape except their natural form, round or square, pointed or pyramidal, in green or grey tubs, seemed to usher you courteously along the great avenue, and lead you by the hand to the lower steps of the porch.

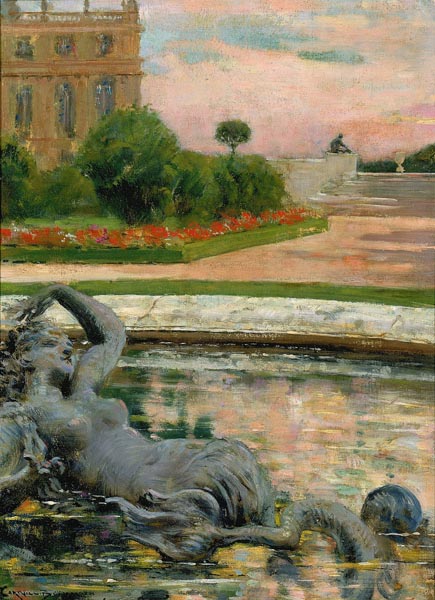

Parterre du Nord, Fontaine des Sirenes (1913)

James Carroll Beckwith (American, 1852-1917)

Artvee

A few turrets, half-buried amidst more recent constructions, protruded above the line of the building to the full height of their slate chimney-tops, while their dove-tailed sheet-metal weathervanes bore witness to a fairly respectable antiquity. The windows of the middle pavilion opened onto a single balcony adorned with an extremely rich and elaborate iron balustrade, while the others were surrounded by stone frames with carved figures and knots.

Four or five large dogs came racing towards us, barking at the top of their lungs, and performing prodigious bounds. They gambolled around the horses, and leapt in their faces: they made a point of welcoming my friend’s horse especially, whom they probably visited in the stable often, or accompanied on walks.

Amidst all this uproar, a sort of servant finally arrived, looking half-ploughman, half-groom, who took our mounts by their bridles and led them away. I had not yet seen a living soul, except for a little peasant girl, timorous and wild as a deer, who had fled on sight of us, to crouch in a furrow behind some hemp, though we called her several times, and did our best to reassure her.

No one appeared at the windows; one would have said the castle was uninhabited, or at least was haunted only by ghosts; for not the slightest noise transpired outside. We were about to climb the first steps of the porch, our spurs jingling since our legs were a little heavy, when we heard inside a sound of doors opening and closing, as if someone were hurrying to meet us.

Indeed, a young woman appeared at the top of the balustrade, raced across the space that separated her from my companion, and threw herself on his neck. He embraced her very affectionately and, putting his arm around her waist, he almost lifted her up, and bore her thus to the landing.

— ‘You know, you are hardly a kind or gallant sort of brother, my dear Alcibiades. What point, sir,’ said the young beauty, turning towards me, ‘is there in informing you that he is my brother, for, in truth, he scarcely displays the manners of one?’

To which I replied that if I were not mistaken, it must prove a misfortune, in some degree, to be her brother, and thus find oneself excluded from the category of her admirers; as for me, if I were her brother, I would be at once the most unhappy, and yet the happiest of horsemen on earth. All of which made her smile gently.

While talking thus, we entered a low-ceilinged room whose walls were decorated with a tapestry woven on a high-warp loom in Flanders, in which large trees with sharply-pointed leaves supported swarms of fantastic birds; the colours, altered by time, producing bizarre transpositions of hue; the sky was green, the trees royal-blue with yellow streaks, and in the draperies of the figures the shadows were often of a colour conflicting with that of the background fabric; the flesh resembled wood, and the nymphs who walked beneath the faded shades of this forest had the air of unwrapped mummies; their mouths alone, whose purple had retained its original tint, smiled with an appearance of life. In the foreground, bristled tall plants of a singular green, with large variegated flowers whose pistils resembled peacock-aigrettes. Herons, of serious and pensive mien, their heads sunk into their shoulders, their long beaks resting on their rounded crops, stood philosophically, each on one thin leg, in still, black water striped with tarnished silver threads; through gaps in the foliage, one could see, far off, small castles with turrets like pepper-pots, their balconies laden with beautiful ladies in full court dress who were watching processions or hunts go by. Capriciously jagged rocks, from which white thready torrents fell, merged at the horizon’s edge with dappled clouds.

One of the things that struck me most forcibly was the figure of a huntress shooting at a bird. Her open fingers had just released the string, and the arrow was in flight, but, as this part of the tapestry turned a corner, the arrow was present on the other wall, having seemingly described a wide curve; as for the bird, it was flying on motionless wings, still seeking a neighbouring branch.

This feathered arrow armed with a golden point, forever in the air and destined never to reach its target, produced the most singular effect on me. It seemed like a sad, painful symbol of human destiny, and the more I gazed at it, the more mysterious and sinister the meaning I discovered there. The huntress stood, her foot stretched out before her, the leg bent, her wide-open eyes, with their silken lids, no longer able to observe her arrow deflected from its path: and seemed to be anxiously searching for the flamingo with variegated feathers that she had wished to bring down, and had expected to see, pierced through and through, fall before her. I know not if my imagination erred, but I found in her face an expression as gloomy and as desperate as that of a poet who dies without having written the work which he had counted on to found his reputation, and whom the pitiless death-rattle seizes while he is attempting to dictate it.

I tell you at length of this tapestry; at greater length, certainly, than it justifies; but it is a thing which has always strangely preoccupied me, that fantastic world created by the Flanders weavers.

I love that fanciful vegetation, with passion; flowers and plants that do not exist in reality; forests of nameless trees where unicorns, horned goats, and snow-white deer with golden crucifixes between their antlers, wander, endlessly, pursued by hunters with crimson beards, in Saracenic dress.

When I was a little girl, I scarcely ever entered a tapestried room without experiencing a kind of shiver, and hardly dared wander about there. All those figures on the walls, to whom the undulations of the fabric, and the play of light, lent a kind of fantastic life, seemed to me so many spies, engaged in observing my actions, so as to give account of them at the due time and place, and I would never have dared eat an apple, or a stolen cake, in their presence. What tales those grave personages could tell, if they could open their lips of red thread, and if sound could penetrate the embroidered conches of their ears. To how many murders, treacheries, infamous adulteries, and monstrosities of all kinds have they not been, silently and impassively, witness! But let me forgo the tapestry and return to our story.

— ‘Alcibiades, I will have my aunt informed of your arrival,’ cried the lady.

— ‘Oh! There’s no urgency, sister; let us sit and talk a little first. Let me present this gentleman, Théodore de Sérannes, to you. He will be spending some time with us. I need not ask you to grant him fair welcome; he is his own recommendation.’ (I repeat what he said; please don’t accuse me of inappropriate conceit). The lovely girl nodded slightly, as if in assent, and we three talked of something else.

As we conversed, I examined her in detail, observing her more closely than I had been able to do before. She was twenty-three or twenty-four years old, perhaps, and her mourning dress suited her to perfection; to tell the truth, she seemed neither gloomy nor desolate, and I doubt whether she consumed the ashes of her Mausolus in her soup every day, as Artemisia is said to have done. I know not if she wept profusely for her deceased husband; if she did, it was hardly apparent, and the pretty cambric handkerchief she held in her hand was as dry as could be. Her eyes were scarcely reddened, but, on the contrary, the clearest and brightest in the world, and one would have searched in vain for furrows on her cheeks where tears had flowed; there were in truth only two small dimples produced by her habitual smile, and it is fair to say that her teeth were thereby seen quite frequently, for a widow: which was certainly no unpleasant sight, for she had neat, well-set ones. I esteemed her most of all for not having felt obliged, merely because her husband had died, to veil her eyes, or empurple her nose: I was also grateful that she lacked a mournful expression, and spoke naturally, in a sonorous and silvery voice, without drawing out her speech and interrupting her sentences with virtuous sighs. It seemed to me to be in very good taste; I judged her, from the first, to be an intelligent woman, which indeed she was.

She was well-formed, her feet and hands very neat; her black costume arranged with every coquetry and so happily that its gloomy hue was offset, and she might have attended a ball dressed thus, without anyone finding it strange. If ever I marry, and am widowed, I will ask her for a pattern of her dress, for it fitted her like an angel.

After conversing a while, we visited the old aunt’s apartments. We found her seated in a large, sloping armchair, with a small stool under her foot, while beside her lay a very sullen, bleary-eyed old dog, who raised his black muzzle at our arrival, and greeted us with a most unfriendly growl.

I never think of old women except with horror. My mother died very young; doubtless, if I had seen her features imperceptibly aging, I would have accustomed myself to the process in a tranquil manner. In childhood, I was surrounded only by young and smiling faces, thus I’ve retained an unconquerable antipathy towards old people. So, I shuddered when the beautiful widow’s pure, rosy lips touched the dowager’s yellowing brow. Aging is something I cannot accept. I know that if I reach sixty, I will look the same as she; I can do nothing about it, and I pray I will die young like my mother.

However, this old woman had retained, of her former beauty, a natural majesty which had prevented her from displaying that baked-apple ugliness which is the fate of women who have been merely pretty or simply fresh-looking; her eyes, though terminated at their corners by wrinkled folds, and possessing wide, drooping eyelids, still emitted some sparks of their original fire, and one saw that, during the reign of the previous king, they must have cast glances fit to dazzle. Her thin, sharp, nose, slightly curved like that of a bird of prey, granted her profile a sort of sombre grandeur, which was tempered, however, by the indulgent smile on her ‘Austrian’ lips, which were painted with carmine, according to the fashion of the last century.

Her costume was antiquated without being ridiculous, and harmonised perfectly with her figure; her headdress was a basic white wimple adorned with a little lace; her long, thin hands, which one might guess to have been very beautiful, were clad in half-mittens without fingers or thumbs. A dress patterned with autumn leaves, and embroidered with foliage of a darker shade, a black mantle, and an apron of smooth silk the colour of a pigeon’s breast, completed her outfit.

Old women should always dress so, and sufficiently respect the approach of death not to adorn themselves with feathers, garlands of flowers, ribbons in lighter hues, and the thousand trappings that only suit the very young. Those who effect the latter may set out to woo life, but life will have none of them; their efforts are wasted, like those of ancient courtesans who plaster themselves with powder and rouge, women whom drunken muleteers thrust against the barriers, accompanied by insults and kicks.

This old lady received us with that ease and exquisite politeness which is a feature of those who, of old, frequented the Court, the secret of which seems to have been gradually lost, like so many other fine secrets, and her speech, though broken and quavering, still possessed great sweetness of tone.

I seemed to please her very much, and she gazed at me for a long while, very attentively, in a most touching manner. A tear formed at the corner of her eye, and slowly coursed down a large wrinkle, where it was lost and dried. She begged me to excuse her emotion, saying that I looked very much like a son of hers who had fallen in battle.

Because of this resemblance, real or imaginary, the whole time I remained at the château I was treated by this good lady with an extraordinary and entirely maternal kindness. I knew more pleasure there than I would have, at first, believed, for the greatest delight that people of my own age can grant me, is never to address me, and to depart as soon I arrive.

I will not describe day by day, in detail, all I did at R***. If I have dwelt a little on my arrival, and have sketched for you, with some care, these few physiognomies of people and place, it is because most singular and yet predictable events happened there, which I should have foreseen when dressing as a man.

My natural frivolity made me commit an imprudence which I cruelly regret, because it has brought, to a good and beautiful soul, trouble that I cannot ease without revealing who I am, and seriously compromising myself. To perfect my role as a man, and divert myself a little, I thought it best to pay court to my friend’s sister. I found it amusing to scrabble on all fours if she dropped her glove, and return it to her with prostrate bows; to lean over the back of her armchair with an adorably languid lair; and to pour into her ear a thousand and one compliments that could not have been more charming. As soon as she wished to move from one room to another, I graciously offered her my hand; if she rode, I held the stirrup for her, and, when she went for a walk, I always walked beside her. In the evening, I would read to her and accompany her singing; in short, I acquitted myself with scrupulous exactitude as regards all the duties of a cavalier servente. I adopted the expressions, I had seen lovers do, which set me laughing, like the true madwoman I am, whenever I found myself alone in my room, reflecting on all the impertinent speeches I had offered in the most serious tone in the world.

Alcibiades, and the old marquise, seemed to view our intimacy with pleasure, and often left us to our own devices. I sometimes regretted my not being truly a man, as I might have taken better advantage of their indulgence. If I had, it would have needed only my own decision, since the charming widow seemed to have forgotten the deceased completely, or, if she did remember him, would willingly have proved unfaithful to his memory.

Having begun in this manner, I could scarcely, in all honesty, retreat, and it was very difficult to do so bag and baggage; however, I could not exceed certain limits, and hardly knew how to seem more amiable except in words. I hoped to reach the end of the month, that I was to spend at R***, and leave, with the promise of my returning, without doing more. I believed that after my departure the fair lady would console herself, and in my absence, would soon forget me.

Yet, in toying with her, I aroused a serious passion, and things turned out otherwise: which reminds one of a truth that has been long known, namely that one should never play with fire, or toy with love.

Before seeing me, Rosette had not yet known love. Married very young to a man much older than herself, she must only have felt a kind of filial friendship for him; no doubt, she had been courted, but had never had a lover, extraordinary as that may seem: either the gallants who had paid her attention were inept seducers, or, what is more probable, the opportunity had not yet arisen. The provincial squires and gentlemen, always talking of leashes and spoor, sightings and antlers, halloos and ten-point stags, interspersed only with almanac references, and ancient moss-covered compliments, hardly suited, and her virtue had no need to struggle hard to avoid yielding to them. Moreover, her gaiety and natural playfulness sufficiently protected her from love, that melting passion which has such a hold over dreamers and melancholics. Her aged Tithonus’ idea of voluptuousness, had doubtless proved mediocre enough not to tempt her to sample it again, and she had savoured the pleasure of being widowed so early, and having so many years of youthful attractiveness left, in a state of calm.

On my arrival, all this changed. I believe that, if I had, at first, kept within the narrow bounds of cold and exact politeness, she would have paid no further attention to me; but, in truth, I was obliged to recognise afterwards that events would have turned out the same, and that this supposition, though showing modesty on my part, was purely gratuitous. Alas, naught can delay the fatal ascendant; none can avoid the beneficent or malignant influence of their stars! Rosette’s fate is to love only once in her life, and experience an impossible love; she is obliged to fulfil her destiny, and therefore she will.

I am beloved, O Graciosa, and it is a sweet thing, though I am loved only by a woman, and in a love thus embodied, there is something painful not be met with on love’s other path. Oh, a sweet thing indeed! When one wakes in the night, and raises oneself on one’s elbow, saying to oneself: ‘Someone is thinking or dreaming of me; someone is interested in my existence; every movement of my eyes or lips causes joy or sadness in another creature; some word I let fall at random was gathered with care, and is commented on, reflected on, for hours on end. I am the pole to which the free magnet turns; my eyes are stars, my lips a paradise more longed for than the real one. If I were to die, a shower of hot tears would warm my ashes, my tomb would be more bedecked with flowers than a wedding-basket. If I were in danger, someone would throw themselves between the sword-point and my breast; and sacrifice themselves for me! It is a beautiful thought; and I know not what in the world one could wish for more.

The thought gave me pleasure, for which I reproached myself, since I had nothing to give, and was in the position of a debtor who accepts a gift from a rich and generous friend, without hope of ever being able to return the favour. It delighted me to be adored so, and at times I let myself experience that delight with singular complacency. By dint of hearing everyone call me ‘Sir’, and finding myself treated as if I were a man, I forgot, unconsciously, that I was a woman; my disguise seemed to me my natural mode of dress, and I felt I had never worn another; I no longer reflected that I was, after all, nothing but a muddle-headed child, who had fashioned a sword from her needle, and a pair of breeches by adapting one of her skirts.

Many men appear more of a woman than I, for I possess little of one but my breasts, a few other rounded contours, and more delicate hands; the skirt around my hips is not I myself. It often happens that the mind’s gender is not the same as that of the body, a contradiction which cannot fail to produce a degree of disorder. I, for example, if I had not taken this resolution, apparently foolish, but at its heart a wise one, to renounce the attire of that sex which is mine only materially and by chance, I would have been most unhappy. I love horsemanship, fencing, every sort of violent exercise. I enjoy climbing, and racing here and there, like a young lad. It bores me to sit with my feet together, my elbows pressed to my sides, to lower my eyes modestly, to speak in a small, sweet, flute-like, voice, and to thread wool through the holes in a piece of canvas a million times. I do not like obeying instructions in the least, and the words I say most often are: ‘I wish.’ Beneath my smooth brow and silken hair, strong and virile thoughts stir; all the most precious nonsense that women find seductive has touched me but moderately and, like Achilles disguised as a girl, I would willingly quit the mirror for the sword. The only thing that pleases me about women is their beauty; despite the inconvenience that results, I would not willingly renounce my looks, however ill-matched they may be to the mind they clothe.

It was something new and piquant, such an intriguing affair, and I would have been greatly amused by it, if it had not been taken seriously by poor Rosette. She loved me with admirable naivety and conscientiousness, with all the strength of her beautiful and virtuous soul, with that love which men do not comprehend and of which they cannot form even a distant idea; she loved delicately and ardently, as I would wish to be loved, and as I would love, if I met the reality of my dreams. What beautiful lost treasure, what pale, translucent pearls such as divers will never find in the jewel case of the sea! What sweet breath, what gentle sighs scattered in the air, might have been gathered from those pure and loving lips!

Her passion might have made some young man happy indeed! So many unfortunate individuals, handsome, charming, well-endowed, full of heart and spirit, have vainly begged, on their knees, before insensitive and gloomy idols! So many fine and tender souls have thrown themselves, despairingly, into the arms of courtesans, or have died silently like a candle in a tomb, individuals who would have been saved from debauchery, or death, by a love that proved sincere! What a strange thing is human destiny! And how fate mocks us!

What so many others ardently desired, fell to me, who did not, and could not, receive it. A capricious young girl takes a fancy to wander about the country in male attire, to learn the nature of her future lovers; she sleeps in an inn with a worthy fellow, who leads her, by the tip of her finger, to his sister, who without more ado falls in love with her as a cat might, or a dove, as might any of the amorous and languid people in this world. It is perfectly evident that, if I were indeed a young man, and had stood to benefit from the situation, all would have transpired differently, and the lady would have abhorred me, since Fortune is rather fond of handing slippers to those who have high arches, and gloves to those who lack hands; the inheritance that might have allowed you to live comfortably inevitably descends to you on the day of your death.

Sometimes, yet not as often as she would have liked, I visited Rosette in her bedroom. Though she usually only received visitors when she was dressed, nevertheless, she received me as I was her favourite. She would have received many another thing, if I had wanted; but, as they say, ‘the most beautiful girl can only give what she has’, and what I have would have proved of little use to Rosette.

She would hold out her hand to me to kiss; I confess I did not kiss it without some pleasure, for her hands are very white and tender, exquisitely perfumed, and softened by natural moisture; I would feel it shiver and contract under my lips, the pressure of which I would unnecessarily prolong. Then Rosette, quite moved, and with a supplicating air, would turn on me her broad eyes, full of voluptuousness, and flooded with moist, transparent light, then she would let her pretty head fall back on the pillow, which she had raised a little the better to receive me. I would observe her breast swell anxiously, and her body quiver suddenly beneath the sheet. Certainly, someone in a position to act might have dared much, and been grateful for her temerity, and for her having skipped a few chapters of the romance.

I would stay for an hour or two, never letting go of her hands, which I placed on the coverlet; we had endless and charming conversations; for, though Rosette was preoccupied with her amorous feelings, she believed herself too certain of succeeding to forego her free, playfulness of mind. Only occasionally did her passion cast a transparent veil of sweet melancholy over her gaiety, which rendered it even more piquant.

Indeed, it would have seemed ridiculous for a novice, such as I appeared to be, to balk at such good fortune and not make the most of the situation. Rosette, indeed, was not made for enduring cruel delay, and, knowing no more of me than this, counted on her charms and my youth, given the apparent lack of love on my part.

However, as this situation began to extend a little beyond its natural bounds, she became uneasy, and a redoubled flow of flattering phrases, and fine protestations, scarcely allayed her insecurity. Two things astonished her as regards myself, contrary aspects of my conduct which she noted and could not reconcile: my warmth of speech and my coldness of action.

You know better than anyone, my dear Graciosa, that with me friendship bears all the characteristics of passion; it is sudden, ardent, lively, exclusive, and loving to the point of jealousy, and my feelings of friendship towards Rosette were almost as strong as those I have for you. One might be confused by less. Rosette was all the more completely deceived, as my attire scarcely permitted any other idea.

Since I have never yet loved a man, my excess tenderness has somehow spilled over into my friendships with young girls and women; into such friendships I have injected the same passion, the same exaltation, that I inject into everything I do, since I find it impossible to act with moderation, and especially in regard to what concerns the heart. In my eyes, there are only two groups of people, those I adore and those I loathe; the others are as if they did not exist, and I would set my horse at them on the highway: they in no way differ, to my mind, from paving stones or milestones.

I am naturally expansive, and affectionate. Sometimes, forgetting the significance of my actions, I would, while walking with Rosette, put my arm around her body, as I did when you and I walked together on the solitary path at the end of my uncle’s garden; or else, leaning over the back of her armchair while she embroidered, I would run through my fingers the little stray hairs turning blond on the back of her smooth round, neck, or polish, with the back of my hand, her beautiful tresses stretched taut by the comb, to restore their lustre, or else I indulged in some other of those little things that I am accustomed to with my dearest friends, as you know.

She attributed these caresses to more than simple friendship. Friendship, as it is ordinarily conceived, does not extend so far; but seeing that I went no further, she was inwardly astonished, and knew not what to think; she settled on this interpretation: that it arose from too great a timidity on my part, due to my extreme youth and lack of experience in amorous relations, and that I sought to encourage myself through all kinds of advances and kindnesses.

Consequently, she took care to arrange a host of opportunities for tête-à-têtes in places likely to embolden me by their solitude, and distance from all noise and unwelcome arrivals; she took me on several walks in the high woods, to see if the voluptuous reverie, and amorous desire that the dense and propitious shade of the forests inspire in tender souls could not be turned to her advantage.

One day, after having us wander, for a long time, through the most picturesque park which extended far behind the château, and of which I knew only the area bordering the buildings, she brought me, by a little path, whimsically laid out in serpentine fashion, and bordered by elder and hazel bushes, to a rustic cabin, a sort of charcoal-burner’s, hut built of logs laid transversely, with a roof of reeds, and a rough door made of five or six pieces of barely-planed wood, the interstices of which were filled with tow, now covered with wild plants and moss; next to it, amidst the green roots of a clump of large ash trees, their silvery bark spotted here and there with black patches, a strong spring gushed forth, which, a few steps further on, spilled down a pair of marble steps into a basin filled with watercress greener than emerald. In places where there was no cress, one could see fine sand as white as snow; the water was crystal clear, and icy cold; emerging from the earth suddenly, and never being touched by the faintest ray of sunlight, in the nigh-on impenetrable shade it had no time to warm, or become clouded. Despite their chill, I love such springs, and, seeing that this one ran so clear, I could not resist the desire to drink; I bent down and cupped a few drops in the palm of my hand, having no other vessel at my disposal.

Rosette expressed the desire, to quench her thirst, by drinking some of this water as well, and asked me to collect her a few drops also, not daring, she said, to bend down to reach it. I plunged my two hands, joined as closely as possible, into the clear fountain, then raised them like a cup to Rosette’s lips, and held them thus till she had drunk the water they contained, which took no time at all, for there was little there, and that little leaked through my fingers, however tightly I held them; it made for a charming scene, and an artist might have made a fine sketch of the subject.

When she had almost finished, as what was left in one palm was close to her lips, she could not help kissing my hand in such a way as to have me believe it was merely to exhaust the last pearls of water there; but I was not mistaken, and the charming blush which suddenly covered her face gave her away.

She took my arm again, and we walked towards the cabin. The lovely lady walked as close to me as she could, and leaned forward while speaking to me, so that her breast rested entirely on my sleeve; an extremely knowing position capable of disturbing any but myself; I felt its firm, pure contour and gentle warmth perfectly; moreover, I noticed a precipitate undulation of breath which, whether affected or real, was no less flattering and engaging.

We arrived, thus, at the door of the hut, which I opened with a kick; I certainly did not expect the spectacle that met my eyes. I thought the hut would be lined with rushes, with a mat on the ground, and some roughly-carved stools as seats: but not at all.

It was a boudoir, furnished with all imaginable elegance. The friezes and mirror-surrounds represented the most gallant scenes from Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’: Salmacis and Hermaphroditus, Venus and Adonis, Apollo and Daphne, and other mythological amours, rendered in pale-lilac monochrome; the panel over the mantelpiece displayed pompom roses, charmingly carved, and small daisies which, with luxurious refinement, had been granted gilt centres and silvered leaves. Silver braid edged all the furniture, and highlighted coverings of the softest blue to be found marvellously suited to enhancing the whiteness and radiance of flesh. A thousand charming curiosities filled the hearth, consoles, and shelves, and there was a luxury of duchess and other sofas, and chaise longues, which showed this retreat as being intended for no austere occupation, for one certainly would not lack comfort there.

A beautiful rocaille clock, placed on a richly inlaid pedestal, faced a large Venetian mirror, and was reflected therein with singular clarity and brilliance. Moreover, its hands had stopped, as if it were a superfluous thing to mark the hours in a place designed for neglecting them.

I informed Rosette that this refinement of luxury pleased me, that I found it to be in excellent taste to hide the greatest refinement beneath a simple appearance, and that I very much approved of a woman wearing petticoats and chemises, trimmed with embroidery, beneath a simple dress; it was a delicate attention for the lover she had, or might acquire, for which one could not be sufficiently grateful, and that it was certainly better to enclose a diamond in a nutshell, than a nutshell in a golden box.

Rosette, to prove to me that she was of my opinion, raised her dress a little, and showed me the edge of a petticoat very richly and flowerily embroidered; it was my choice whether to be admitted to the secrets of some greater hidden magnificence; but I sought not to discover whether the splendour of the chemise corresponded to that of the petticoat: it is probable its luxuriousness was no less. Rosette let the fold of her dress fall, angry at not having been requested to reveal more. However, the exhibition had served for her to show the lower part of a perfectly turned calf. and grant a fine idea of its continuation. In truth, her leg, which she had stretched forward to better spread her skirt, looked wondrously fine and graceful, in its pearl-grey silk stocking, stretched smooth and tight, while the mule with a heel and adorned with a tuft of ribbons, that clad her foot, resembled the glass slipper worn by Cinderella. I paid her the sincerest of compliments, and told her that I scarcely knew a prettier leg or a smaller foot, and thought it impossible to meet with a finer. To which she replied with a frankness and ingenuousness quite spirited and charming: ‘It’s true.’

Then she went to a convenient cupboard in the wall, took out a few liqueur bottles, and various plates of cakes and preserves, deposited everything on a small pedestal table, and sat down beside me on a somewhat narrow couch, so that I was obliged, in order for us not to be too cramped, to place my arm about her waist. As she had both hands free, and I only my left hand, she poured me a drink, and filled my plate with the fare. Observing that I was going about things rather clumsily, she said to me: ‘Come now; I’ll feed you like a little child, since you don’t know how to eat on your own.’ And she herself raised the pieces to my mouth, and forced me to swallow them faster than I liked, pushing them in with her pretty fingers, just as one fattens birds, which set her laughing. I could scarcely avoid granting her fingers a counterpart to the kiss she had granted the palm of my hand a moment ago, while as if to stop me, but in truth to provide the opportunity for me to press home my kiss more firmly, she brushed my lips two or three times with the backs of her fingers.

She had drunk two or three fingers of Crème de Barbades (lemon ratafia) with a glass of Canary Islands wine, and I about the same. Certainly not a great deal; but enough to vivify two women accustomed to drinking only watered-down spirits. Rosette let herself fall back, and leaned on my arm most amorously. She had thrown off her mantlet, her manner of arching her back revealing the curve of her breasts; their skin tone of a ravishing delicacy and transparency; their form, of a marvellous finesse and, at the same time, firmness. I contemplated her for some time with an indefinable and pleasurable emotion, and the thought came to me that men were more favoured than us in their love affairs, that we granted them the most charming treasures to possess, and that they had nothing equivalent to offer us. What a pleasure it must be to run one’s lips over that smooth, polished flesh, those rounded contours which seem to rise to meet a kiss and provoke it! Satiny skin, undulating curves which merge into one another, silky hair so soft to the touch; what inexhaustible incentives for delicate voluptuousness that men fail to provide us with! Caresses, for us, can scarcely be more than passive; yet there is more pleasure in giving than receiving.

These are remarks that I certainly would not have uttered last year; then, I could have viewed all the throats, breasts, and shoulders, in the world, without being concerned as to the grace or otherwise of their form; but, since I doffed the garb of my own sex, and took to living among a wider group of young people, a feeling has developed in me that was unknown to me before: a feeling for female beauty. We women usually seem to lack it, I know not why since, superficially, we would seem better placed to judge it than men; but, as women are the ones who possess it, and since self-knowledge is the most difficult of all, it is scarcely surprising that we understand little about it. Ordinarily, if a woman compliments another woman on being ‘pretty’, one can be sure the latter is in truth quite ugly, and that no man will pay her attention. Equally, all the women whose beauty and grace are praised by men are unanimously considered abominable, and sycophantic, as far as the whole flock of skirted females are concerned; they raise endless cries and clamour. If I were the man I appear to be, I would accept no other guide, and female disapproval would grant me sufficient proof of a woman’s beauty.

Now I both love and appreciate beauty; the clothes I wear separate me from the rest of my sex, and remove from me all rivalry; I am able to judge of their beauty better than they. I no longer see as a woman, though not yet as a man does, thus desire cannot blind me to the point of mistaking mannequins for idols; I gaze cooly, and without prejudice, thus my position is as wholly disinterested as possible.

The length and fineness of her eyelashes, the glow of her temples, the clarity of her pupils, the shape of her ears, the tone and quality of her hair, the nobility of her feet and hands, the greater or lesser slenderness of her ankles and wrists, a thousand things to which I paid no attention before, but which constitute true beauty, and demonstrate a purity of lineage, guide me in my appreciation, and hardly allow me to err. I believe that one could accept unseen any woman of whom I might say, as men do: ‘Truly, she’s not bad.’

As a quite natural consequence, I am much more confident about judging the beauty of paintings than before, and, though I have only a very superficial acquaintance with the masters of portraiture, it would be hard to convince me that a poor effort was good; I find in such studies a singular and profound charm; for, like everything in the world, moral or physical beauty desires to be studied, and refuses to allow one to penetrate it all at once. But let us return to Rosette; to make the transition from the one subject to the other is not difficult, each evoking its counterpart.

As I have said, the lovely woman leant back against my arm, her head resting on my shoulder; emotion tinged her beautiful cheeks with a tender pink hue, which was admirably enhanced by the pure black of a small beauty mark very coquettishly placed; her teeth shone behind her smile like raindrops in the depths of a poppy-flower, and her eyelashes, half-lowered, further increased the moist brilliance of her large eyes; a ray of sunlight made a thousand metallic sparkles play over her silken, wavy hair, some of which had escaped, and fell, in the form of shadowy pentimentos, down her round, smooth neck, whose warm whiteness they emphasised; a few small, stray hairs, more mischievous than the others, stood out from the mass, twined in capricious spirals, gilded with singular reflections, and which, traversed by the light, acquired every nuance of prismatic colour: one might have thought them those golden threads which surround the heads of virgins in old paintings. We both remained silent, and I amused myself by tracing the small azure-blue veins beneath the pearly transparency of the surface of her temples, and the soft and imperceptible down at the end of her eyebrows.

The lovely woman seemed to withdraw into herself, lost in a dream of infinite voluptuousness; her arms hung at her sides, undulating and soft as loose scarves; her head leant further and further back, as if the muscles that supported it had been severed or were or too weak to do so. She had tucked her two feet under her petticoat, and had managed to nestle completely in the corner of the loveseat I occupied, so that, although this piece of furniture was too narrow, there was now an empty space on the other side.

Her body, relaxed and supple, modelled itself against mine like wax, and took on that external contour as exactly as could be: water could not have insinuated itself more precisely into all its sinuosity of line. Attached thus to my flank, it created something akin to the dual line with which painters embellish a drawing on the shaded side, in order to amplify and deepen the effect. Only a woman in love achieves such undulation and intertwining. Ivy and willows are very far from displaying the same.

The gentle warmth of her body penetrated through her clothes and mine; a thousand magnetic lines radiated around her; her vitality seemed to have passed into me, wholly, and abandoned her, completely. From minute to minute she languished, and died, and arched more and more: a light perspiration beaded her glossy brow: her eyes moistened, and two or three times she made the movement of raising her hands as if to hide them; but, halfway there, she failed to reach them, and her arms fell back weakly against her knees; a large tear overflowed an eyelid and rolled down her burning cheek, where it soon dried.

Dante’s Dream (Io sono in pace) (1875)

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (English, 1828 - 1882)

Artvee

My situation was becoming most embarrassing and even somewhat ridiculous; I felt I must look enormously foolish, and this annoyed me to the last degree, although it was not in my power to assume any other posture than that. An enterprising manner was denied me, yet it was the only one that would have been appropriate. I was certain of not meeting with any resistance to risk it, yet, in truth, could make nothing of it. Uttering gallantries and rattling off compliments might have been fine at the start, but nothing could have proved more insipid at the point we had reached; to rise and depart would have been the height of rudeness; and besides, who knows if Rosette would not have played the part of Potiphar’s wife, and held me back by the corner of my cloak. I could have offered no virtuous motive to excuse my resistance; and then, I will confess to my shame, this scene, however ambiguous its character was not without a certain charm for me, which detained me more than it ought; a flame of ardent desire licked me, and I was truly sorry not to be able to satisfy its urging: I even wished I were a man, in accord with my attire, in order to crown this love, and regretted, greatly, that Rosette was mistaken in me. My breathing quickened, I felt a hot blush rise to my cheeks, and was hardly less troubled than my poor lover. The thought of our like gender was gradually fading, leaving only a vague feeling of pleasure; my eyes were veiled, my lips trembled, and, if Rosette had been a man instead of a woman, ‘he’ would certainly have found me easy prey.

At last, unable to contain herself, she rose suddenly, with a sort of spasmodic movement, and began to walk about the room with great activity; then she halted in front of the mirror and adjusted a few locks of her hair, which had lost their shape. During all this, I cut a poor figure, hardly knowing how to behave.

She stopped in front of me and seemed to think. She no doubt thought extreme shyness alone was restraining me, that I was more of a mere schoolboy than she had first believed. Beside herself, having mounted to the highest degree of amorous exasperation, she chose to make a supreme effort, and dare everything, at the risk of losing all.

She approached me, with a lightning motion seated herself on my knees, threw her arms about my neck, crossed her hands behind my head, and seized my mouth in a furious embrace. I felt her breasts, rebellious and half-naked, press against my chest, as her intertwined fingers tightened in my hair. A shudder ran through my whole body, and the tips of my breasts rose on end.

Rosette mouth never left mine; her lips enveloped my lips, her teeth struck against my teeth, our breaths mingled. I drew back for a moment, and averted my head two or three times to avoid her kiss; but an unconquerable attraction drew me back, and I returned the kiss almost as ardently as she delivered it. I know not what would have occurred, if loud barking had not been heard outside the door, and the sound of scrabbling paws. The door gave way, and a fine white greyhound entered the cabin, barking and frolicking.

Rosette rose, suddenly, and ran to the far end of the room: the greyhound leapt around her vigorously and joyfully, trying to reach her hands to lick them, such that she had great difficulty arranging her mantle on her shoulders. This greyhound was her brother Alcibiades’ favourite dog: he never left her brother’s side, and his arrival meant his master was not far behind; that is what had so frightened poor Rosette.

Indeed, Alcibiades himself entered a minute later, all booted and spurred, with his riding-whip in his hand: ‘Ah! There you are,’ he cried, ‘I’ve been seeking you for an hour, and certainly would never have found you if Snug, my brave greyhound, had not roused you from your hiding place.’ And he cast a half-serious, half-playful look at his sister, which made her blush to the whites of her eyes. ‘You must have had some thorny subject or other to discuss for you to retreat to such deep solitude? Doubtless you were talking theology, concerning the dual nature of the soul?’

— ‘Oh! Good Lord, no. Our occupation was by no means so sublime; we were nibbling cake, and talking of fashions; that was all,’ Rosette answered.

— ‘That, I don't believe; you seemed deeply immersed in exchanging sentiments; but, to distract you from your vapid conversation, I think it would be no bad thing if you were to ride beside me. I’ve a new mare I wish to try. You may ride her too, Théodore, and we shall see what can be done with her.’

The three of us exited together, he lending me his arm, I giving mine to Rosette: the expressions on our faces were singularly varied. Alcibiades looked thoughtful, I quite at ease, Rosette excessively annoyed.

Alcibiades had arrived at just the right moment for me, and at the wrong moment for Rosette, who thus lost, or thought she had lost, all the fruit of her clever attacks and ingenious tactics. It was all for her to do again; a quarter of an hour more, and the Devil take me if I know what outcome the affair would have had. I can’t see what it would have led to. Perhaps it would have been better if Alcibiades had not intervened at precisely the most delicate of moments, like a deus ex machina: one way or another, it would have had to have ended. During this whole scene, I was, two or three times at least, on the point of confessing what I was to Rosette; but the fear of passing for an adventuress, and my secret being divulged, kept the words from my lips, though ready to flee.

Such a state of affairs could not continue. My departure was the only way to put an end to this hopeless affair; so, at dinner, I officially announced that I was leaving the very next day. Rosette, who was seated next to me, almost fainted on hearing the news, and dropped her glass. A sudden pallor covered her beautiful face: she threw me a pained and reproachful look, which moved and troubled me almost as much as she did herself.

The old aunt raising her wrinkled hands, with a movement of painful surprise, asked, in a faint, trembling voice, which quavered even more than usual: ‘Ah! My dear Monsieur Théodore, you are leaving us so soon? That is wrong of you; yesterday you seemed not in the least disposed to go. There was no post: so, you received no letters, and can have no reason. You promised us another fifteen days, and you are retracting; you really have no right to do so: a promise given may not be withdrawn. You can see what Rosette’s face is like, and how she reproaches you; I warn you I shall reproach you at least as much as her, and make just as dreadful a face at you, and a sixty-eight-year-old face is somewhat more terrible than a twenty-three-year-old one. Now see what you voluntarily expose yourself to: the anger of both the aunt and the niece, and all for some whim that has momentarily seized you!

Alcibiades swore, thumping his fist on the table, that he would barricade the gate and hamstring my horse, rather than let me go. Rosette gave me so sad and pleading a look it would have required the ferocity of a tiger that had been fasting for eight days not to be touched by it. I yielded, and, though it greatly annoyed me, made a solemn promise to stay.

Dear Rosette would have gladly jumped on my neck, and kissed me on the mouth, at this kindness. Alcibiades enclosed my hand in his larger one, and shook my arm so violently he almost dislocated my shoulder, left my rings oval instead of circular, and scored three of my fingers quite deeply. The old woman, delighted, took a huge pinch of snuff.

However, Rosette failed to regain her cheerfulness completely; the idea that I might leave and harboured a desire to do so, an idea which had not clearly presented itself before to her mind, cast her into a deep reverie. The colour which the announcement of my departure had driven from her cheeks did not return as vividly as before; her cheeks remained pallid, and she still seemed marked by anxiety. My conduct towards her surprised her more and more. After the marked advances she had made to me, she could not understand my motive for exercising such restraint in my relations with her: what she desired was to obtain my decided commitment before I left, not doubting that afterwards it would be quite easy for her to detain me as long as she wished.

In this she was right, and, if I had not been a woman, her calculation would have been wholly correct; for, whatever has been said about the satiety of pleasure and the disgust which ordinarily follows, every man whose heart is true, and who is not wretchedly jaded without recourse, feels his love increase with his happiness, and very often the best way of keeping a lover who seeks to leave, is to yield oneself to him with complete abandon.

Rosette intended to bring me to the requisite point, before my departure. Knowing how difficult it is to resume a relationship at the point where one has left it, and, moreover, being by no means certain of ever finding herself close to me and in such favourable circumstances again, she neglected no opportunity that might present itself to allow me to speak clearly, and abandon the evasive manner behind which I had taken refuge. Since I, for my part, had the quite decided intention of avoiding any kind of meeting similar to that in the rustic cabin, but could not, however, without appearing ridiculous, affect too much coldness towards Rosette or adopt a little girl’s prudish manner, I knew not quite what attitude to take, and tried to ensure there was always a third person by us.

Rosette, on the contrary, did everything she could to be alone with me, and quite often succeeded, the château being far from the town and little frequented by the neighbouring nobility. My silent resistance saddened and surprised her; at times doubts and hesitations arose in her in regard to the power of her charms, and, seeing herself so little loved, she was sometimes not far from believing that she was ugly. Then she redoubled her attentions and coquetry, and though her mourning did not allow her to employ all the resources of her attire, she nevertheless knew how to adorn and vary it so as to be two or three times more charming each day, which is saying something. She tried everything: she was playful, melancholy, tender, passionate, considerate, coquettish, even simpering. She adopted, one after the other, all those adorable masks that suit women so well that one no longer knows whether they are indeed masks or their real faces; she successively assumed nine or ten contrasting roles, to discover which might please me, and settle on that. All by herself, she created a complete seraglio, in the course of which attentions I was merely required to submit; but nothing, of course, came of it.

Her lack of success, despite every stratagem, made her fall into a profound stupor. Indeed, she would have turned old Nestor’s brain, and melted the ice of chaste Hippolytus, themselves, and I appeared no less of a Nestor or Hippolytus: though young, I possess a haughty and resolute air, a bold way of speaking, and, everywhere except in private, a very decided countenance.

She might have believed that all the witches of Thrace and Thessaly had cast a spell on my body, or that, at the very least, my ‘cord was knotted’, and might have formed a very poor opinion of my virility, which was indeed rather lacking. However, it seems the thought never occurred to her, and she simply attributed my singular reserve to a lack of love for her.

The days passed, and the affair failed to progress: she was visibly affected: an expression of anxious sadness had replaced the fresh smile that had previously always bloomed on her lips; the corners of her mouth, so joyfully arched, fell noticeably, forming a firm and serious line; a few small veins were drawn in a more marked manner on her moistened eyelids; her cheeks, formerly like the skin of a peach, had retained only their imperceptibly velvety quality. Often, from my window, I saw her crossing the flowerbed in her morning-gown; she walked, barely lifting her feet, sliding along, her two arms limply crossed on her chest, her head inclined, more bowed than a willow branch over water, with something undulating and sagging about her, like an over-long piece of drapery whose end was touching the ground. At those moments, she looked like one of those ancient lovers fallen prey to Venus’ anger, against whom the pitiless goddess acted in a completely ruthless manner: such is how I imagine Psyche to have been when Eros had forsaken her.

On the days when she was not trying to overcome my coldness and hesitation, her love had a simple and primitive allure that might have charmed me; it was a silent, trusting abandonment of self, a chaste readiness for caresses, an inexhaustible abundance and fullness of heart, all the treasures of a beautiful nature poured out without reserve. She had none of that pettiness and meanness that one finds in almost all women, even the most gifted; she never sought to disguise her feelings, and quietly allowed me to witness the full extent of her passion. Her self-esteem did not rebel for even a moment, even though I failed to respond to her many advances, for pride quits the heart the moment love enters it; and if ever someone was truly loved, it was myself, and by Rosette. She suffered, yet without complaint or bitterness, and attributed the small success of her attempts only to herself. However, her pallor increased every day, and the lilies had so engaged the roses in her cheeks, on the field of combat, that the latter had been decisively routed; this distressed me, but, in good conscience, I could do less than anyone to address it. The more I spoke to her in a gentle and affectionate manner, the more amorous she was with me, the more I plunged the barbed arrow of unrequited, and unrequitable, love into her heart. By consoling her at present, the greater the despair I was preparing for her in future; my remedy poisoned her wound while appearing to lull her to sleep. I repented, in a way, of all the pleasant things I had chosen to say to her, and would have liked, because of the great friendship I had for her, to find a means of making her hate me. One can carry disinterestedness no further. I might have lost my temper with her; which would have been better.

Indeed, I tried two or three times, to address her harshly, but quickly returned to complimenting her, fearing her tears even more than her smile. On such occasions, though loyalty of intent fully absolves me in all conscience, I was more touched than I should have been, and felt something not far from remorse. A tear can hardly be dried except by a kiss, and one cannot decently leave that office to a handkerchief, even if it is of the finest cambric in the world. I undid what I had done, the tear was soon forgotten, more swiftly than the kiss, redoubling, in the event, my degree of embarrassment.

Rosette, who now sees that I am about to escape her, clings stubbornly and miserably to the remains of her hopes, and my position becomes more and more complicated. The strange sensation I experienced in the little cabin, and the inconceivable disorder into which the ardour of my beautiful lover’s caresses threw me, have been renewed in me several times, although less violently; and often, sitting near Rosette, her hand in mine, hearing her speak to me in a sweet cooing voice, I even imagine I am a man, as she believes me to be, and that, if I do not respond to her love, it is simply cruelty on my part.

One evening, I know not by what chance, I found myself, in that room decorated in green, opposite the old lady; she had some tapestry-work in her hands, for, despite her sixty-eight years, she never remained idle, wishing as she said, to finish, before dying, this decoration for a piece of furniture, which she had begun, and had been working on for a long while. Feeling a little tired, she set down her work, and leant back in her tall armchair: she looked at me most attentively, and her grey eyes sparkled behind her glasses with a strange vivacity; she passed her moisture-less hand two or three times over her wrinkled forehead, and seemed to be deep in thought. The memory of times that were no more, whose absence she regretted, gave her face a melancholy and tender expression. I remained silent, for fear of disturbing her thoughts, and for a few minutes there was a silence, which she finally broke.

‘Those are the real eyes of my Henri, my dear Henri, the same moist, shining look, the same set of the head, the same proud but gentle physiognomy; one might think you were he. You cannot imagine the extent of the resemblance, Monsieur Théodore. When I see you, I can no longer believe that Henri is dead; I think him returned at last from some long journey. The sight of you has given me much pleasure, and a deal of pain, Théodore: pleasure, by reminding me of my poor Henri; pain, by showing me how great the loss I suffered; sometimes I have taken you for his ghost. I cannot get used to the idea that you must leave us; it seems to me that I am losing my Henri once again.’

I told her that if it were really possible for me to stay longer, I would choose to do so with pleasure, but that my stay had already extended well beyond the limits set; that, moreover, I fully intended to return, and that the château would leave me too many pleasant memories to forget in haste.

— ‘As sorry as I am at your departure, Monsieur Théodore,’ she continued, pursuing the subject, ‘there is someone here who will be sorrier than I. You will understand who I mean without my naming her. I know not what we will do with Rosette when you are gone; this old château is a sad place. Alcibiades is always out hunting, and, for a young woman like her, the society of a poor cripple like me is scarcely entertaining.’

— ‘If any should regret it, it is neither you nor Rosette, madame, but I; you lose but little, I much; you will readily gain the company of those more charming than I, while it is more than doubtful that I can ever replace that of Rosette and yourself.’

— ‘I’ve no wish to decry your modesty, my dear sir, but I know what I know, and I say what is true: it is likely we will not see Madame Rosette in good spirits again for a long while, since it is you yourself who now determine the colour of her complexion. Her period of mourning is about to end, and it would be truly unfortunate if she were leave off happiness along with her last black dress; that would set a very poor example, and be quite contrary to custom. It is something you could prevent without too much trouble, and will surely prevent,’ said the old woman, emphasising the last words.

— ‘I’ll certainly try my best to ensure your dear niece remains cheerful, since you suppose I have such influence over her. However, I scarcely see how.’

— ‘Oh! How poor your vision is then! What use are those fine eyes? I never thought you so short-sighted. Rosette is free; she has an income of eighty thousand livres, which no one else has any claim on, and women twice as ugly as her are considered very pretty. You are young, handsome, and, I think, unmarried; the thing seems to me the simplest thing in the world, unless you have an unconquerable dislike for Rosette, which is hard to believe...’

— ‘And is not the case, and could not be, as her soul is equal to her person, and she is one who could appear ugly without anyone thinking or wishing them otherwise than they are…’

— ‘She could appear ugly with impunity, yet, in truth, she is charming. That is doubly right; I do not doubt your words; she always presents herself well. As for her, I would willingly answer that there are a thousand people she dislikes, while, if she were questioned, she would end by confessing that perhaps you do not exactly displease her. You wear a ring there that would suit her, for your fingers are as slender as hers, and I am quite sure she would accept it with pleasure.’

The good lady paused for a few moments to see what the effect of her words might be, and I doubt she was satisfied with the expression on my face. I was cruelly embarrassed and knew not what to reply. From the start of the conversation, I had perceived where her insinuations were leading; and, though I had well-nigh anticipated her words, I still felt surprised and speechless. I could only refuse, but what valid reason could I give for such a refusal? I had none, except that I was, in reality, a woman: an excellent reason, true, but certainly one I could not confess to.

I could scarcely claim some ridiculous objection on the part of my parents; any parent in the world would accept such a union with delight. Had Rosette not been what she was, kind and beautiful, and of good family, the eighty thousand pounds that were hers would remove all difficulty. To declare that I did not love her would have been neither true nor honest, for I really loved her deeply, and more than a woman usually loves another of her sex. I was too young to pretend to be engaged elsewhere: the best I could do was to claim that, being a younger son, family interest required that I enter the Order of Malta, and did not allow me to think of marrying: a fact which caused me the greatest grief in the world now I had met Rosette.

This was not worth a fig as an answer, and I felt it perfectly well. The old lady was not fooled, and refused to regard it as definitive; she thought that I had spoken thus to give myself time to reflect and to consult my parents. Indeed, such a union was so advantageous to me, and out of the common, that she thought it scarcely possible for me to refuse, even if I loved Rosette little or not at all; it was hardly a piece of good fortune to be neglected.

I do not know if the aunt made her overture to me at the instigation of her niece, but I am inclined to believe Rosette had nothing to do with it: she loved me too simply and ardently to think of anything other than possessing me, and marriage would certainly have been the last means she would have employed. The dowager, who had not failed to notice our intimacy, which she doubtless believed to be much greater than it was, had doubtless conceived this whole plan in her head, so as to have me stay to replace, as far as was possible, her dear son Henri, killed in action, to whom she had found I bore such a striking resemblance. She took delight in the idea, and had used this moment when I was alone with her to her advantage. I could see from her expression that she did not consider herself defeated, and that she intended to return to the assault, and soon, which irritated me to the last degree.

That night, Rosette for her part, made a last attempt on me, which had such serious results that I must render you separate account of it, and cannot do so in this already excessively inflated letter. You will see to what a singular affair I was predestined, and how heaven has singled me out, in advance, to be the heroine of a novel. I am uncertain what moral one can draw from it all, but lives are not works of fiction, with every chapter ending in a fine sentence or two. Often life’s only meaning is that it is not death. That’s all for now. Farewell, my dear friend, I kiss you on your lovely eyes. You will receive the continuation of my wondrous biography shortly.

Chapter 13: D’Albert to Théodore

Théodore, or Rosalind, for I know not by which name to call you, I caught sight of you a moment ago, and now am writing to you. How I wish I knew your family name! It must sound as honey tastes, and flutter on the lips more sweetly and harmoniously than poetry! I would never have dared to say this, face to face, and yet I am dying to do so. What I have suffered, no one knows, no one could know, I myself can only give a faint idea of it; words cannot convey such anguish; I could force myself to contort the language, wilfully; drive myself to say new and singular things; to yield to the most extravagant exaggeration, and yet still describe what I experienced in images that barely sufficed.

O, Rosalind! I love you; I adore you; would there were a stronger word even than that! I have never loved, have never adored, anyone as I do you. I prostrate myself; I annihilate myself before you, and would like to force all creation to bend the knee before my idol; you are to me more than all Nature, more than myself, more than any god; it seems strange to me that the Lord himself does not descend from heaven to be your slave. Where you are not, all is desert, all is dead, all is darkness. You alone people the world for me; you are my life, my sun; you are my all. Your smile brings on the day, your sorrow the night. The heavenly spheres follow the movements of your body, and the celestial harmonies are regulated by you, O my beloved queen! O my real, and lovely dream! You are clothed in splendour, and you bathe in endless radiance.

I have known you for a mere three months, but have loved you a long while. Before I saw you, I already longed for you. I called to you, I sought you, and despaired of not meeting you on my life’s path, for I knew I could never love another woman. How many times you have appeared to me, at the window of a mysterious château, leaning melancholically on the balcony, casting the petals of some flower or other to the breeze, or else, a lively Amazon, on a Turkish horse whiter than snow, galloping the dark alleys of the forest! Yours indeed were those proud and gentle eyes, diaphanous hands, and beautiful wavy hair, accompanied by a half-smile, so charmingly disdainful. Yet the goddess of my dream proves less beautiful, since the most ardent and unbridled imagination, that of the artist and poet, cannot attain to the sublime poetry of reality. There is in you an inexhaustible source of grace, an ever-flowing fount of irresistible seductiveness: you are a forever-open casket of the most precious pearls, and, your slightest movements, your most forgetful gestures, your most abandoned poses, exhibit at every moment, in regal profusion, beauty’s inestimable treasures. If the soft undulations of contour, if the fleeting lines of a gesture could be fixed, and retained, by a mirror, those before which you passed would cause the divinest canvases of Raphael to be scorned, and regarded as no more than cabaret posters.

Every attitude, every expression of your head, every varying aspect of your beauty is engraved on the mirror of my soul in diamond point, and nothing in the world could erase its profound imprint. I recall how the shadows lay, how the light fell, the planes that the sun’s rays illuminated, and the region where some stray reflection merged with the more softened tints of neck and cheek. I could draw you in your absence; your image is always before me.

As a child, I would stand for hours before the paintings of the old masters, eagerly searching the dark depths. I would gaze at those lovely figures of saints and goddesses whose flesh, white as wax or ivory, stood out so wondrously against a background darkened to charcoal by the fading of its colours. I would admire the simplicity and magnificence of their figures; the strange grace of their hands and feet; the proud, beautiful character of their features, at once so fine and so firm; and the grandeur of the draperies that fluttered about their divine forms, and whose purple folds seemed to lengthen to embrace those beautiful bodies. By dint of plunging my eyes, obstinately, beneath the smoky veil thickened by the centuries, my vision became blurred, the contours of objects lost their sharpness, and a kind of motionless, deadened life animated all those pale phantoms of vanished beauty. I ended by believing that those figures vaguely resembled the beautiful stranger whom I adored in the depths of my heart. I sighed at the thought that she whom I had been destined to love was perhaps one of them, yet had been dead for three hundred years. This idea often affected me to the point of making me weep, and I would feel anger within at not having been born in the sixteenth century, when all that beauty was alive. I felt it to be the result of an unpardonable, hapless, yet awkward error on my part.

As I grew older, the sweet phantom haunted me even more assiduously. I saw it, forever hovering between myself and each woman who was my mistress, smiling ironically, mocking their human beauty in all the perfection of its divine loveliness. It made me seek out ugly women, who were yet truly charming, and born to console any not enamored of that adorable shade whose body I did not conceive of as actually existing and whose beauty was only a presentiment of your own beauty. O Rosalind! How unhappy I was, on account of you, yet before I knew you! O Théodore! How unhappy I am, on account of you, now I have seen you! If you wished, you could open the paradise of my dreams to me. You stand at the threshold, like a guardian angel wrapped about by its wings, and hold the golden key in your beautiful hands. Say, Rosalind, say if you wish it so?