Théophile Gautier

Mademoiselle de Maupin

Part IV: Chapters 10 and 11

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

Chapter 10: Théodore to Graciosa

My fair friend, you were quite right to try and deter me from pursuing my plan of observing men, and studying them thoroughly, before granting my heart to any one of them. It has led to my renouncing love, inwardly, and even the possibility of love.

Poor young girls that we are; raised with such care, our virginity defended by a triple wall of precaution and reticence, we, who are permitted to understand nothing, surmise nothing, and whose sum of learning is to know nothing, by what strange errors we live, and what perfidious chimeras rock us in their arms!

Ah! Graciosa, thrice cursed be the moment when the idea of this disguise came to me; what horrors, infamy and vulgarity, I have been forced to see and hear! How my chaste and precious ignorance has been dissipated, and in no great length of time!

Do you recall that beautiful moonlit night? We walked together in the garden’s depths, down that sad and little-frequented path, ending, on the one side, at the statue of a flute-playing Faun, lacking a nose, and whose whole body is covered with a thick coating of blackish moss, and, on the other, in a false perspective, drawn on the wall and half-erased by the rain. Through the still sparse foliage of the hornbeam, we could see the stars sparkling here and there, and the moon’s silver crescent. The scents of fresh shoots and new leaves reached us from the flowerbeds, on the soft breath of a little breeze; an unseen bird whistled a strange, languid tune; we, as young girls do, talked of love, of gallants, of marriage, of the handsome gentleman we had seen at Mass; we exchanged what scant notions we possessed as regards the world and its affairs; we examined in a hundred ways some sentence we had heard by chance and whose meaning seemed obscure and intriguing; we asked each other a thousand ludicrous questions such as only complete innocence can conceive. What primitive poetry, what adorable nonsense, in those furtive conversations between two little fools, who had finished with school but a day or so before!

Lovers on a moonlit lane (1873)

John Atkinson Grimshaw (English, 1836 – 1893)

Artvee

You desired as your lover some bold, proud young fellow, a kind of amorous braggart, with dark hair and a moustache, large spurs, a tall plume, and a great sword; you aimed straight for the heroic and triumphant: you dreamt only of duels and sieges, and of wondrous devotion, and would have gladly thrown your glove into the lions’ den for your Esplandián (see Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo’s ‘The Adventures of Esplandián’, 1510) to retrieve: it was more than comical to watch a little girl like you, blonde, flushed, yielding to the slightest breeze, deliver those fine tirades, in a single breath, and with the most martial air in the world.

I, though only six months older, was six years less of a romantic: one thing intrigued me above all, and that was what men said to each other, and what they did, after they left the salons and theatres: I sensed many a doubtful and obscure affair in their lives, affairs carefully veiled from our gaze, yet which it was most important for us to penetrate. Sometimes, hidden behind a curtain, I spied, from afar, on the cavaliers who came to the house, and it seemed to me that I could discern something ignoble and cynical in their appearance, a gross insouciance or a fierce self-preoccupation, that vanished as soon as they entered, seemingly shed as if by magic on the threshold of the room. All of them, young and old, seemed to me to have uniformly adopted a conventional mask, display of feeling, and mode of speech, when they were with the women. From the corner of the living room, where I sat as straight as a doll, not leaning back in my chair, while rolling the stem of my bouquet between my fingers, I listened, I watched; though my eyes were lowered, I saw everything to right and left, in front and behind: like the fabled eyes of the lynx, my eyes pierced the walls, and I could have told you what was happening in the next room.

I also found a notable difference in the way married women were addressed; no longer in the polite, discreet, childishly-framed phrases delivered to me or my companions; a freer playfulness was on display, a less sober and more relaxed manner, an obvious degree of reticence and subtlety, revealing a level of decadence matched by a correspondingly decadent air: I felt that there was a mutual understanding between them that was lacking between us, and I would have given anything to comprehend its origins.

With what anxiety, and what eager curiosity, I followed, by sound and sight, those groups of young people and the buzz of laughter they emitted, who, having chosen various directions for their promenades, resumed their course, chattering away, and casting ambiguous glances as they passed. On their lips, puckered in disdain, hovered incredulous sneers; they seemed to mock at the words they themselves had said, to retract the compliments and showers of praise they had heaped upon us. I could not hear their words; but I understood, from the movement of those lips, that they were pronouncing words in a language unknown to me, and which no one had ever used before me. Even those who possessed the humblest and most submissive air gave a shrug, and a perceptible expression of rebellious ennui, a breathless sigh, like that of an actor who has reached the end of a long speech, escaped their lips despite themselves; while, once they had passed us they turned on their heels in a brisk, lively manner, displaying a kind of inner satisfaction at being freed from the harsh chore of seeming honest and gallant.

I would have given a year of my life to listen to an hour of their conversation without being seen. Often, I gathered, from a certain posture, a few sidelong gestures, and glances cast obliquely, that it was myself who was in question. and that they were talking either about my age or my appearance. Then I was as if standing on burning coals; the few stifled words, the fragments of sentences that reached me at intervals, roused my curiosity to the highest degree without being able to satisfy it, and I was full of strange doubts and perplexities.

Most often what was said was favourable in tone; it was not that which troubled me: I cared little whether people found me beautiful; but the brief comments whispered in an ear, and almost always followed by mocking smiles, and the odd blink of an eye, they were what I wished to comprehend; and, to overhear one of those phrases spoken quietly, from behind a curtain, or in the angle of a door, I would have abandoned without regret the most flowery, perfumed conversation in the world.

I longed to know in what terms, if I were actually to take a lover, he might speak of me to other men, in what terms he might boast of his good fortune to his drunken companions, elbows on the tablecloth, after a few bottles of wine. I know now, and am truly sorry that I do, that they speak ever in the same manner.

The idea I conceived was foolish, but what’s done is done, and one cannot unlearn what one has learned. I refused to listen to you, my dear Graciosa, and I regret it; but one does not always listen to reason, especially when it comes from lips as pretty as yours, since, I know not why, one imagines good advice as only ever deriving from some old, grey-haired person, as if sixty years of stupidity renders one wise.

Well, it all proved a torment to me, and I could not endure it; I was roasting in my skin like a chestnut in the coals. The fatal apple hung, a globe in the foliage, above my head, and I was tempted to take a bite, even if the taste proved bitter to me and I was forced to cast it aside afterwards. I did as Eve, my ancestress, did — I bit deep.

The death of my uncle, my only remaining relative, left me free to act, and I carried out what I had dreamed of for so long. I took the greatest care, my precautions such that none would question my gender: I had learned how to wield a sword, and shoot a pistol; I rode perfectly, with a boldness of which few squires were capable; I studied the manner of wearing a man’s cloak, and making the whip crack, and, in a few months, succeeded in turning the girl who was considered quite pretty into an even prettier horseman, who lacked little more than a moustache. I realised what funds I had, and left town, determined not to return until I had experienced all.

It was the only way to quench my doubts: taking a lover or two would have taught me nothing, or at least it would have given me only incomplete glimpses, and I wanted to study men thoroughly, to anatomize them inexorably, fibre by fibre, with a scalpel, and view them alive and palpitating on my dissection table; and for that I had to see them alone at home, in a state of undress, and to follow them on visits to taverns and elsewhere. So disguised, I might enter everywhere without being noticed. Men, indeed, could not hide from me; with me, they cast aside all reserve and constraint; I received confidences, and uttered false ones to provoke the truth. Alas, women have only read novels written by men, never their histories!

It is a fearful thing to consider, and women seldom do, how profoundly ignorant we are of the life and conduct of men who appear to love us, and whom we may wed. Their real existence is as completely unknown to us as if they were inhabitants of Saturn, or some other planet hundred of millions of miles from our sublunary orb: I declare they are of another species, and there is not the slightest intellectual bond between the two sexes; the virtues of one seem faults in the other; what renders a man admired renders a woman hated.

Our female lives are clear, and penetrated at a glance. It is a simple task to follow our trajectory from home to boarding-school, from boarding-school to domesticity; what we do is a mystery to none; everyone can view our inept pencil sketches, and our coloured bouquets, composed of a pansy and a rose as big as a cabbage, and gallantly tied at their stems with a ribbon of tender hue. The slippers we embroider for our father’s or grandfather’s birthday are nothing very strange or disturbing. Our sonatas, and our singing, are performed with the expected lack of emotion. We are well and duly tied to our mothers’ skirts, and, at nine or ten o’ clock at the latest, we retreat to our little white beds, in the depths of our neat, discreet cell-like rooms, in which we are virtuously imprisoned till next morning. The most alert and jealous guardian would find nothing untoward in this. The clearest crystal is less transparent than such a life.

Whatever man marries us knows how we have been occupied from the moment we were weaned, and even before, if he chooses to take his research so far. Our life is not a life, it is a kind of vegetative existence like that of moss or flowers; the icy shadow of the maternal presence hovers about us, poor stifled rosebuds that are scared to open. Our whole business is to hold ourselves upright, very straight and trim, with our eyes properly lowered, and to outdo dolls or mannequins in our immobility and rigidity

We are forbidden to speak, forbidden to join in conversation except, if questioned, to answer yes or no. As soon as we seek to say something interesting, we are sent off to learn to play the harp or spinet, and our music teachers are all sixty years old at least, and take far too much snuff. The plaster models in our rooms possess a most vague and evasive anatomy. The gods of Greece, in order to reveal themselves to a boarding school for young ladies, take care beforehand to buy very ample capes at a second-hand clothes shop, and to have themselves engraved with stippling, which grants them the appearance of doormen or cab-drivers, and so hardly likely to fire our imaginations.

Barred from being romantic, we are rendered stupid. The days of our education are spent not in teaching us something, but in preventing us learning anything.

We are truly prisoners in body and mind; but a young man, free in his actions, who goes out in the morning and returns the following morning, who has funds, and can earn them and dispose of them as he pleases, how would he justify the use of his time? What man would want to tell his beloved what he did during the day, or at night? None, not even among those who are reputed to be purest by nature.

I sent my horse, and my clothing, to a small farm I had bought some distance from town. I dressed, mounted and departed, though not without a strange pain at heart. I regretted nothing, I left nothing behind neither relatives, nor friends, not even a dog, or cat, and yet I was sad, I well-nigh had tears in my eyes. This farm which I had only visited five or six times held nothing special or dear to me, and I felt none of the affection that one feels for certain places, and which moves one when one must leave them, yet I still turned around two or three times, to view from afar the tendrils of blue smoke from its chimney, rising between the trees.

It was there I had left my title of ‘woman’, along with my dresses and skirts; in the room where I donned my new garb, I relinquished twenty years of a life that no longer counted or concerned me. On the door one might have written: ‘Here lies Madeleine de Maupin’; for indeed I was no longer Madeleine de Maupin, but rather Théodore de Sérannes, and none would now call me by that sweet name of Madeleine. The drawer in which my dresses were kept, now abandoned, seemed to me like the coffin of my innocent illusions; I was a man, or at least I had the appearance of one: and the young girl was dead.

Once the crowns of the chestnut trees surrounding the farm were lost to sight, it seemed to me I was no longer myself, but another, and I recalled my former actions as if they had been those of a stranger, actions which I had merely witnessed, or those at the start of a novel I had not yet finished reading.

I remembered, complacently, a thousand little details whose childish naivety brought to my lips an indulgent smile, a little mocking smile, like that of a young libertine listening to the arcadian, pastoral confidences of a third-grade schoolboy; and, at the moment when I departed forever, all my childish and adolescent female selves hovered at the edge of the road, offering me a thousand signs of friendship, and sending me kisses from the tips of their white, slender fingers. I spurred my horse to escape those unnerving emotions; the trees sped by swiftly to left and right; yet that playful crowd, buzzing louder than a hive of bees, ran up and down the side paths, calling: ‘Madeleine! Madeleine!’

I gave my mount a harsh blow on the neck with my whip, which made it redouble its speed. My hair stretched almost straight behind my head, my body was horizontal, the folds of my coat as if carved in stone, so great was my speed; I looked back once, and saw a small white cloud far away on the horizon, the dust that my horse’s hooves had raised.

I halted for a while. I saw something white stirring, amidst a wild rose bush, at the edge of the road, and a small voice, clear and sweet as silver, struck my ear: ‘Madeleine, Madeleine, where are you going so fast, Madeleine? I am your virgin innocence, my dear child; that is why I have a white dress, a white coronet, and pale features. But you, why are you booted like a man, Madeleine? You have very pretty feet. Boots, and breeches, and a large hat with a plume, like a horseman going to war! Why is that sheath striking, and bruising your thigh? Your outfit, is strange, Madeleine, and I know not whether I should keep you company.’

— ‘If you’re afraid, my dear, return home; water my flowers, and tend my doves. But in truth you are wrong, you are safer in these fine clothes than your gauze and linen. My boots prevent anyone knowing whether I’ve a pretty foot or no; the sword is for my defence; the feather fluttering from my hat is to scare away all those nightingales who would come and sing false love-songs in my ear.’

I continued on my way. In the sigh of the wind, I thought I recognised the last phrase of the sonata I’d learned for my uncle’s birthday; in a large rose that raised its head above a low wall, the large rose I had used for a model in painting so many watercolours; and passing a house, I saw the ghosts of my curtains floating at a window. All my past seemed to cling to me, and prevent me from advancing towards my fresh future.

I hesitated two or three times, and turned my horse’s head as if to return. But the little blue snake of curiosity hissed softly and insidiously: — ‘On, on, Théodore; this is a fine opportunity to learn; if you fail to instruct yourself now, you never will. Would you give your noble heart, randomly, to the first man who merely appears honest and passionate? Men hide most extraordinary secrets from us, Théodore!’

I resumed my gallop. I felt my breeches on my body, but not in my mind. I felt a certain unease, a sort of shiver of fear, to grant the thing its name, while navigating a dark corner of the forest; a gunshot, probably fired by a poacher, well-nigh made me faint. Had he been a robber, the pistols in my saddlebags and my formidable sword would certainly have proved of little help. But moment by moment, I hardened myself, and paid my feeling no further attention.

The sun was slowly sinking below the horizon, like the chandelier at the theatre lowered once the performance is done. A pheasant, or a rabbit, crossed the road from time to time; the shadows were lengthening, and all the horizon was tinged with red. Some parts of the sky were a soft and faded lilac, others were a lemon or orange hue; the nocturnal birds were beginning to call, and a multitude of strange noises emerged from the woods: the little light still present was gradually extinguished, and the darkness was complete, deepened as it was by the shadows cast by the trees. I, who had never ventured out alone at night, found myself at eight in the evening in a dense forest! Can you imagine that, my Graciosa, I who used to tremble with fear at the end of the garden? Terror seized me, and my heart beat terribly. It was with great relief, I confess, that I saw the lights of my destination appear and sparkle on the slopes of a hill. As soon as I saw those bright points, like small terrestrial stars, my fear completely vanished. It seemed to me that those indifferent gleams were the eyes of as many friends watching over me.

Woodland Pond at Sunset (c. 1862)

Gerard Bilders (Dutch, 1838-1865)

Artvee

My horse was no less pleased than I was and smelling the sweet scent of a stable, an odour more agreeable to him than those of daisies or wild strawberries, he sped straight towards the Red Lion Hotel.

A pale light shone through the leaded window of the inn, whose tin sign swung from side to side and moaned like an old woman as the north wind began to freshen. I handed my horse to a groom and went to the kitchen. An enormous fireplace, whose black maw yawned, redly, in its depths, consumed a bundle of wood at each mouthful, and on either side, a pair of hounds, sitting on their haunches, and almost as tall as human beings, were toasting themselves, with the greatest composure in the world, content with raising their paws a little, and emitting a sigh of sorts as the heat became more intense; but, preferring, it seemed, to be reduced to ashes than retreat an inch.

My arrival seemed to give them little pleasure and, though I patted their heads several times, so as to introduce myself, it was all in vain; the glances they cast augured nothing good. I was surprised, because animals usually warm to me, quite readily.

The innkeeper approached and asked me what I desired for dinner. He was a pot-bellied fellow, with a red nose, squinting eyes, and a grin that stretched from ear to ear. At every word he spoke, he revealed a double row of sharp teeth like an ogre’s. The large kitchen knife that hung at his side seemed capable of several dubious uses. When I had told him what I wished to eat, he went and kicked one of the dogs, which rose and slouched to a sort of mill-wheel, which it entered with a pitiful, sullen air, and a reproachful glance towards myself. Finally, seeing that scant mercy was forthcoming, it began to turn the wheel, and in turn, therefore the spit which held the chicken for my supper. I promised myself to throw it the leftovers as a reward for its efforts, and looked about the kitchen while waiting for my meal.

Wide oak beams lined the darkened ceiling, blackened by the smoke from the hearth, and from the candles. On the dressers, pewter dishes gleamed brighter than silver in the shadows, beside white earthenware pots with bouquets of blue flowers. Along the walls, numerous rows of well-scoured saucepans looked like those depictions of antique shields that were once suspended the length of Greek or Roman triremes (forgive me, Graciosa, the epic splendour of my comparison). One or two plump maids were busy around a large table, amidst a clatter of dishes and forks, music more agreeable than any other, when one is hungry, to the stomach rather than the ear. All in all, in spite of the innkeeper’s coffer of a mouth and jagged teeth, the inn had a fairly honest and cheerful appearance; and though the innkeeper’s smile had been a yard longer and his teeth three times longer and sharper, the rain pattered against the window-panes, and the wind howled, in such a manner as to rob one of all desire to leave, for I know of nothing more lugubrious than such moaning on a dark and rainy night.

An idea struck me that made me smile: that no one in the world would have thought to find me where I then was. Indeed, who would have thought that little Madeleine, instead of lying in her warm bed, with her alabaster candlestick beside her, a novel beneath her pillow, and her maid in the next room, ready to come running at the least nightmare, was rocking on a chair with a straw seat, in a country inn, fifty miles from her house, her booted feet resting on the andirons, her little hands tucked proudly in her pockets?

Yes, Madelinette no longer remained, like her companions, with an elbow lazily propped on the edge of the balcony, amidst the morning glories and jasmines at the window, gazing over the plain, at the violet edge of the horizon, or some little rose-coloured cloud drifting on the May breeze. She no longer filled the mother-of-pearl palaces in which she lodged her chimeras with lily-leaves; she did not, like you, beautiful dreamers, adorn some empty phantom with all imaginable perfections: she wanted to understand men before giving herself to any man; she abandoned everything, her beautiful, brilliantly-coloured dresses in velvet and silk, her necklaces, her bracelets, her birds, and her flowers; she had willingly renounced all adoration, prostrate gallantry, all bouquets and madrigals, the pleasure of being claimed as more beautiful or better adorned than you, her sweet feminine name, everything that was hers, and had run off, that courageous girl, all alone, to gain, amidst the vast world, knowledge of life.

Hearing of it, people might have said Madeleine was mad. You said it yourself, my dear Graciosa. But the truly mad ones are those who fling their souls to the wind, and sow their love at random amidst rocks and stones without knowing if a single ear of it will sprout.

O Graciosa! It is a thought ever accompanied with terror, where I am concerned: the thought of loving someone unworthy of me! To bare my soul to impure eyes, and allow some profane intruder to penetrate the sanctuary of my heart! To stain for a time its limpid waters with a muddy wave! However completely they may part from it, something of its silt always remains, and the flow cannot regain its original transparency.

To think that a man has kissed you and touched you; that he has seen your body; that he can say: ‘She is like this, or like that; she has such and such a blemish in such a place; she has such and such a cast of thought; she laughs at this, and cries at that, and her dream is of this other; and here in my wallet is a feather from the wings of her chimera; this ring is braided with a lock of her hair; a fragment of her heart is enfolded in this letter; she caressed me in this manner,’ or ‘this is her customary tender phrase!’

Ah, Cleopatra, I understand now why you had that lover you had spent the night with slain in the morning. A sublime act of cruelty, for which, I lacked enough imprecations, once! Grand voluptuary that you were, how well you knew human nature, and how much depth there was in that barbarous notion! You wished no living person to be capable of divulging the mysteries of your bed; the words of love, that had flown from your lips, were never to be repeated. In that way, you preserved others’ illusions concerning you. Habit did not consume, piece by piece, the charming phantom you had cradled in your arms. You preferred to be separated from it by a sudden blow of the axe than gradual disgust. What torment, indeed, to see the man you have chosen betray, minute by minute, the idea you have formed of him; to discover in his character a thousand petty traits that you never suspected; to realise that all that had seemed so beautiful to you when viewed through love’s prism was in effect quite ugly, and that he whom you had taken to be a true hero from a novel was revealed, in the end, to be only a prosaic bourgeois who wears slippers and a dressing gown!

I lack Cleopatra’s power, and if I possessed it, I would certainly lack the strength to deploy it. Also, since I shall not, and cannot, have my lovers decapitated when I leave my bed, and am not in the mood to endure what other women bear, I must think twice before taking such a lover; or three times rather, if the desire takes me, which I very much doubt, given all I have seen and heard; unless, that is, I meet in some unknown, yet blessed, land a heart like mine, a pure and virginal heart, as the novels have it, that has never loved though capable of love, in the true sense of the word, which is not, by any stretch of the imagination, a likely thing.

Several horsemen entered the inn; the storm and the darkness had prevented them from continuing their journey. They were all young, the oldest certainly not more than thirty: their clothes announced that they belonged to the upper class, and, if not their clothes, the insolent ease of their manners would have made it sufficiently clear. There were one or two who had interesting faces; the others all had, to a greater or lesser degree, that kind of brutal joviality, and careless show of good nature, which men display among themselves, and which they completely divest themselves of in our presence.

If they could have suspected that the frail young man, half asleep on his chair, in the corner of the fireplace, was not what he appeared to be, but rather a young girl, ‘a pretty little thing’, as they say, they would assuredly have changed their tone promptly; they would have puffed themselves up immediately, and tried to display themselves to advantage. They would have approached me with deep bows, legs planted, elbows out, and a smile in their eyes, on their lips, their noses, their hair, in every attitude of their bodies; they would have omitted the phrases they used among themselves, and uttered satiny and velvety compliments; at the slightest movement on my part, they would have offered to stretch themselves out on the floor as a carpet, for fear that my delicate feet might be offended by its unevenness; all hands would have been raised to support me; the softest seat would have been placed for me in the most comfortable place; but I looked like a pretty boy, not a pretty girl.

I confess I was almost on the point of regretting leaving my skirts behind, finding how little attention they paid me. I was quite mortified for a while; for, I forgot, now and then, that I was wearing male apparel, and was obliged to recall it to maintain a proper manner.

I stood there, saying nothing, arms crossed, and gazing with a seemingly very attentive air at the chicken which was browning nicely, and at the unfortunate dog that I had so sadly disturbed, struggling away inside its wheel like a demon trapped in a font of holy water.

The youngest of the troop approached and dealt me a friendly blow on the shoulder which hurt a great deal, and drew from me a little involuntary cry, then asked if I would not prefer to sup with them than alone, since folk drank better when there were several together. I answered that it was a pleasure I’d scarcely dared hope for, and would do so very willingly. The table was set, and we took our places side by side. The dog was released, panting, and after swallowing a huge bowlful of water, with three laps of its tongue, resumed its position opposite the other hound, who had not moved any more than if he had been made of porcelain, the newcomers not having requested chicken, by heaven’s particular grace.

I learned, from a few sentences that escaped them, that they were off to the Court, which was then at ***, where they were to join other friends of theirs. I told them I was a younger son of rank who had just left university, and was going to visit relatives in the provinces, by the schoolboy’s route, that is to say, by the longest one I could find. This made them laugh, and, after a few remarks about my innocent, candid air, they asked if I had a mistress. I replied I knew nothing about such things, and they laughed even more. Bottle followed bottle swiftly; and though I was careful never to empty my glass, my head became a little heated, and, without losing sight of my object, I ensured that the conversation turned to the subject of womankind. It was scarcely difficult; because after theology and aesthetics, that is the topic men debate most readily when drunk.

These comrades were not inebriated, they carried their wine too well for that; but they did begin to enter into endless moral discussion, propping their elbows on the table without ceremony. One of them even placed his arm about the plump waist of one of the maids, and was inclining his head very amorously: another swore he would die instantly, like a toad made to take snuff, if Jeannette refused to let him plant a kiss on each of the large red apples that served as her cheeks. And Jeannette, not wishing him to die like a toad, granted his wish with a deal of grace, and even failed to deny the hand that insinuated itself audaciously between the folds of her kerchief, in the moist vale of her breasts, quite ill-protected by a small gold cross, and it was only after a brief conversation, in low tones, that he set her free to remove the dishes.

Yet these were courtiers of refined morals, and assuredly, unless I had witnessed the scene, I would never have thought of accusing them of gross familiarity with inn maids. It is probable that they had just quitted their charming mistresses, to whom they had sworn the finest oaths in the world: in truth, I would never have previously thought of warning a lover not to soil his lips on some Maritorne’s cheeks; lips to which I might have offered mine.

The rascal seemed to take great pleasure in that kiss, no more and no less than if he had kissed Phyllis (see Ovid’s ‘Heroides’ II) or Oriana (see Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo’s ‘Amadis of Gaul): it was a smacking kiss, firmly and frankly applied, which left two small white marks on the damsel’s blushing cheek, and which she wiped away with the back of her hand fresh from washing the dishes. I doubted he had ever given so naturally tender a one to that pure deity who was supposed to command his heart. This was apparently his thought too, for he said in a low voice, and with a completely disdainful movement of the elbow:

— ‘To hell with thin women, and grand sentiments!’

This moral seemed to the liking of the assembly, and all nodded their heads in assent.

— ‘My goodness,’ said another, continuing this theme, ‘I meet with misfortune in everything I touch. Gentlemen, I must confide to you, under the seal of greatest secrecy, that I, who am speaking to you, have a passion for someone at this moment.’

— ‘Oh ho!’ cried the rest. ‘A passion! That’s exceeding droll. And how do you treat your passion’

— ‘She’s an honest woman, gentlemen; gentlemen, you mustn’t laugh; for after all, why shouldn’t I seduce an honest wife? Did I say something ridiculous?... Look, you there, I’ll break your head if you don’t stop.’

— ‘Well! And then?’

— ‘She’s crazy about me: she’s truly the most beautiful soul in the world; in matters of soul, I’m knowledgeable, I know women as well as I do horses at least, and I guarantee you that hers is a soul of the finest quality. She displays elevated thought, ecstasy, devotion, sacrifice, and every refinement of tenderness, everything that one can imagine that’s most transcendent; though she’s almost no breasts, none at all, like a little girl of at most fifteen. She is quite pretty, however; her hands are finely formed, and her feet small. But she has overmuch spirit, and not enough flesh, and for that I wish to quit her. The Devil! One cannot sleep with a spirit. I am most unhappy; pity me, my friends.’ And, mellowed by the wine he had drunk, he began to weep, bitterly.

‘Jeannette will console you for your misfortune in sleeping with a sylph,’ his neighbour told him, pouring him a drink; ‘her soul is so solid one could easily carve others’ bodies from it, and she’s enough flesh to clothe the frames of three elephants.’

O pure and noble lover! If you knew how the man you love most in all the world, he for whom you have sacrificed everything, speaks of you at the inn, casually, in front of people he barely knows! How he shamelessly undresses you and, brazenly, delivers you, utterly naked, to the drunken gaze of his comrades, while you wait, sadly, chin in hand, eyes gazing at the path on which he will return to you!

If someone came and told you that your lover, perhaps no more than twenty-four hours after leaving you, was courting a vile serving-maid, and had arranged to spend the night with her, you’d deem it impossible, and refuse to believe it. Though you’d hardly credit your eyes and ears, yet it is so.

Their conversation, the wildest and most shameful in the world, lasted some time; and their buffoonish exaggerations, their often-filthy jokes, displayed a real and profound contempt for women. I learned more that evening than by reading twenty cartloads of moral treatises.

The enormous, unheard-of things that met my ears tinged my face with a sadness and severity which the other guests noticed, and which they kindly tried to dispel; but my feeling of gaiety was lost. I had indeed suspected that men were not as they appeared to us, but I did not yet believe them to be so different from their masks, and my surprise was equalled by my disgust.

It would take but half an hour of listening to such conversation to correct a young girl’s romantic ideas forever; it would be better for her than all maternal remonstrance.

Some boasted of possessing as many women as they pleased, and of needing only to say the word; others communicated their recipes for procuring mistresses, or discussed the tactics to follow in laying siege to the virtuous; some ridiculed the women whose lovers they were, and proclaimed themselves the most complete imbeciles on earth for having consorted with such creatures. All made little of the idea of love.

So, these are the thoughts they hide from us behind their fine shows of pretence! Who would have conceived it, seeing them grovelling so, and seemingly so humble, so amenable? Ah! How, after their conquests, they raise their heads boldly, and set the heels of their boots insolently on the foreheads they previously adored from afar and on their knees! How they avenge themselves for their temporary humiliation! How dearly they make us pay for their politeness! And how insultingly they brush aside the madrigals they composed! What frenzied coarseness of language and thought they display! What inelegance of manners and bearing! The alteration is complete, and one which is certainly not to their advantage. However extreme my predictions might have been, they fell far short of the reality.

My Ideal, blue flower with a golden heart, pearled with dew, that blooms beneath the Spring sky, amidst the perfumed breath of gentle reverie, and whose fibrous roots, a thousand times more delicate than the silk braids of feys, plunge to the depths of our soul, where their thousand hairy tendrils drink its purest substance; bittersweet flower, one cannot pluck you without the heart bleeding in its deepest recesses, while from your broken stem ooze crimson drops, which, falling one by one into the lake of our tears, serve to measure the tremulous hours of our vigil by the bed of dying Amor.

Ah! Cursed flower, how you had blossomed in my soul! Your shoots had multiplied there like nettles amidst ruins. Nightingales came to drink from your chalices, and sing in your shade; diamantine butterflies, with emerald wings, and ruby-red eyes, fluttered and danced about your frail pistils covered with golden dust; many a bee sucked your poisoned honey unaware; chimeras folded their swan-like wings and crossed their leonine claws beneath their beautiful breasts, as they rested beside you. The tree of the Hesperides was no better guarded. Sylphs gathered starry dew in the hearts of lilies, and watered you magically every night. Plant of the Ideal, more venomous than the manchineel or the upas tree, what it has cost me, amidst your deceptive flowers, and the poison breathed in with your perfume, to uproot you from my soul! The cedar of Lebanon, the gigantic baobab, the palm-tree a hundred cubits high, could not fill the place together that you occupied all alone, little blue flower with the golden heart.

Supper was finally over, and the question of retiring to bed arose; but, as the number of sleepers was twice that of beds, it naturally followed that they either had to take it in turns, or sleep two in a bed. That was a simple matter for the rest of the company, but not nearly so for me, in view of the protuberances which my shirt and doublet together conceal quite admirably, but which a shirt alone would have revealed in all their roundness; and I was scarcely disposed to betray my incognito, before any of those gentlemen, who at that moment seemed to me truly primitive monsters, but whom I have since recognised as fine, devilish, fellows, worth as much as any of their kind.

The one whose bed I was to share was fairly drunk. He threw himself on the mattress, leaving one leg and arm dangling towards the ground, and fell asleep at once; not sleeping the sleep of the just, but in a sleep so deep that the angel of the Last Judgment might have blown his trumpet in the man’s ear and he would not have woken. His falling asleep greatly simplified my difficulty; I removed only my doublet and boots, stepped over the body of the sleeper, and stretched out on the sheet, on the window side.

So, I was lying with a man! A promising way to begin! I confess that, despite all my self-confidence, I was singularly moved and troubled. The situation was so strange, so new, I could hardly admit to myself it was not a dream. The fellow slept as deeply as one can, but I failed to close my eyes all night.

He was a young man, about twenty-four years of age, with a rather handsome face, dark eyelashes and an almost blond moustache; his long hair flowed like the waves rippling from an urnful of water poured into a pool, a slight blush tinted cheeks as pale as clouds reflected in the depths, his lips were half-open and bore a vague and languid smile.

I raised myself on my elbow, and gazed at him for a long while, by the flickering light of a candle whose wax had dripped in large sheets, and whose wick was covered with black flecks. Quite a large gap separated us. He occupied one extreme edge of the bed; I, as an extra precaution, had taken myself to the other edge.

All I had heard was assuredly not of a nature to predispose me to tenderness or voluptuousness: I felt a horror of the male sex. However, I felt more troubled and agitated than I ought: the body failed to share the mind’s repugnance as profoundly as it should have done. My heart was beating fast, I was burning hot, and, whichever way I turned, could find no rest.

The deepest silence reigned; only the occasional dull thud of a horse’s hoof striking the floor of the stable could be heard, or the sound of a water-drop falling from the chimney onto the ashes. The candle, having reached the end of its wick, died in a cloud of smoke.

The densest darkness fell like a curtain between us. You can hardly imagine the effect produced by that sudden loss of light. It seemed to me that all was over, and that I would never be free of the dark again as long as I lived. I felt like rising from bed; but how would I have occupied myself? It was still only two in the morning, all the lamps were unlit, and I could scarcely wander about like a ghost, in a dwelling strange to me. I was obliged to stay where I was, and wait till dawn.

I lay on my back, hands clasped, trying to think of something, and with always the one thought, namely: that I was lying with a man. I went so far as to wish that he would wake, and realise that I was a woman. No doubt the wine I had drunk, though small in quantity, had something to do with that extravagant idea, but I could not help returning to it. I was on the point of touching his side, waking him, and telling him who and what I was. A fold of the blanket that obstructed my arm was the reason I failed to carry the thing through to the end: it granted me time to reflect; and, while I was freeing my arm, I recovered the commonsense that had deserted me, if not fully at least enough to restrain me.

Would it not have been strange indeed, if a lovely disdainful person like myself, if I who would have wished to observe a man for ten years before even yielding him my hand to kiss, had given myself, in an inn, on a pallet-bed, to the first man who came along! And, by my faith, it would scarcely have taken much.

Can a sudden hot effervescence in the blood, overcome, thus, the proudest resolve? Does the voice of the body speak louder than that of the mind? Whenever my pride soars too high in the sky, I summon up the memory of that night, and bring myself back down to Earth. I am increasingly in agreement with male opinion: what a poor thing is a woman’ virtue, and, Lord, on what slight things it depends!

Ah! It is in vain that one tries to spread one’s wings; too much dirt and dust weighs them down; the body is like an anchor that moors the soul to the earth: though the vessel spreads its sails before the breath of elevated ideas, it yet hangs motionless, as though all the remora fish in the Ocean clung to its keel. Nature delights in such mockery. When she sees the mind mounted, proudly, on a tall pillar, elevated towards the sky above, she compels the blood to flow faster, and strain the arteries; she commands the brow to swell, the ears to ring, and behold, vertigo seizes the haughty: images merge and blur, the earth seems to sway like the deck of a boat in a storm, the sky rotates, the stars dance a jig; and those lips, which once uttered only austere maxims, purse, and draw closer, as if ready to be kissed; those arms, ready to repel every advance, weaken, become more supple, and clasp another tighter than a scarf. Add to that the touch of the other’s body, the breath of a sigh through one’s hair, and all is lost. Often even less is needed: the scent of cut grass that flows through your half-open window, from the fields; the sight of two pigeons billing and cooing; a patch of daisies; an old love song you recall in spite of yourself, and repeat without registering its meaning; a warm breeze that disturbs and intoxicates you; or perhaps the softness of your bed or sofa, a single one of these things is enough. The solitary nature of your room makes you think there ought to be two of you there, and that there was never a more charming nest for a brood of fledgling pleasures. Drawn curtains, half-light, silence, all arouses the fatal idea that brushes you with perfidious wings, and murmurs softly around you. The fabric that touches your arm, seems to caress you, and drape its folds across your body. It is then that the young girl opens her arms to the first footman with whom she finds herself alone; and the philosopher leaves his work unfinished, and, head in his cloak, runs in haste to the nearest courtesan.

I felt no love, in truth, for the man who roused me to such curious agitation. He had no other charm than that of not being a woman, yet, in the state I was in, that sufficed! A man! That mysterious thing so carefully hidden from us; that strange animal of whose history we knew so little; that god or demon who alone could realise all the vague dreams of voluptuousness that Spring brought us in sleep; the sole object of our thoughts since the age of fifteen!

A man! Some confused idea of pleasure floated in my drowsy head. The little I knew of such feelings nonetheless kindled my desire. Ardent curiosity urged me to quell, once and for all, the doubts that embarrassed me and constantly recurred in my mind. The solution to the problem lay overleaf and I had only to turn the page, for the book was beside me. A handsome enough knight, a narrow enough bed, a dark enough night! A girl whose brain was dazed by a few glasses of champagne! What a propitious chain of circumstances! Well! All that resulted was plain nothing.

On the wall, on which my eyes were fixed, I began to distinguish, thanks to the waxing light, the advent of day. The window-panes became less opaque, and the grey light of morning which penetrated them restored their transparency; the sky was illuminated little by little: it was dawn. You cannot imagine what pleasure those pale rays, lighting the green of my Serge d’Aumale riding-habit gave me, which bordered the glorious battlefield where virtue had triumphed over desire! It seemed to me like a field of victory. As for my sleeping companion, he had slumped to the floor.

I rose, tidied myself as quickly as possible and ran to the window. I opened it, the morning breeze did me good. I stood before the mirror, to comb my hair, and was astonished at the pallor of my face, which I had thought must be blushing crimson.

The others entered to see if we were still sleeping, and nudged their friend with their foot, who showed little surprise on finding himself in the position he occupied.

The horses were saddled, and we set off. But let that suffice for today; my pen is blunt, and I too tired to sharpen it. I’ll tell you the rest of my adventures later. In the meantime, love me as I love you, Graciosa the aptly-named, and, despite what I’ve just written, don’t think too badly of me, or my virtue.

Chapter 11: D’Albert to Silvio

Many things are a bore: it’s a bore to return money one has borrowed, funds one was accustomed to regard as one’s own; it’s a bore to caress the woman today one loved yesterday; it’s a bore to visit a house for dinner, and find the owners are in the country for a month; it’s a bore to write a novel, and more boring to read it; it’s a bore to find a pimple on one’s nose, and to possess chapped lips on the day one goes to visit the idol of one’s heart; it’s a bore to be shod in ridiculous boots that yawn at the pavement through every seam, and above all to have emptiness lodge in one’s cobwebbed purse; it’s a bore to be a doorkeeper or an emperor; it’s a bore to be oneself, or to be another; it’s a bore to walk when your corns hurt, ride a horse when you your backside aches, in a carriage where some fat fellow is bound to make a pillow of your shoulder, or aboard a steamer if you feel seasick, and so vomit up all the contents of your stomach; it’s a bore to endure the winter in which you shiver, and the summer in which you sweat; but the most tedious thing in earth, hell, or heaven, is certainly to attend the performance of a tragedy, unless it be a romance, or a comedy.

A tragedy truly makes my head ache. What could be more foolish or more stupid? Those great tyrants with bull-like voices, pacing the stage from side to side, swinging their hairy arms like windmill sails, and imprisoned in flesh-coloured stockings, are they not wretched imitations of Bluebeard, or the Ogre? Their inflated pride would make any audience still awake burst into laughter.

Those lovers of the romances are no less ridiculous. It is something indeed to see them advance, dressed all in black or all in white, with hair down to their shoulders, sleeves that cover their hands, bodies ready to pop from their corsets like kernels pressed between one’s fingers; and seeming to drag the soles of their satin shoes along the floor, or, in great movements of passion, pushing their coat-tails back with a little kick of the heel. The dialogue, composed exclusively of ‘Oh!’s and ‘Ah!’s that emerge amid their giggles, as they preen themselves, is truly a pleasant meal and easy to digest. Their princes are always most charming; only a little dark and melancholic, which does not prevent them from being the finest companions in the world, and elsewhere.

As for those comedies that are supposed to correct our morals, but which fortunately fulfil that role rather badly, I find their paternal sermons and carping uncles, as tiresome on stage as in reality. It is not my opinion that we should double the count of fools by presenting them theatrically; there are already enough as it is, thank the Lord, nor is the species about to become extinct. Why portray someone who has a snout like a pig, or a muzzle like an ox, or repeat the nonsense of some fool whom one would hurl from the window if he visited your house? An actor playing a pedant is as uninteresting as the pedant himself; seen in a mirror, he’s no less of a pedant. A mime who imitates the poses and mannerisms of a cobbler, perfectly, amuses me no more than the real cobbler.

But there is one form of theatre that I love: an impossibly fantastic, and extravagant form, which the honest public would hiss, mercilessly, from the very first scene, for want of being unable to understand a word of it.

It is a most singular form too. Glow-worms serve as lamps; a beetle beating time with its antennae directs the music. The cricket performs its part; the nightingale is first flute; little sylphs, emerging from pea-flowers, clasp lemon-peel double-basses between their pretty legs which are whiter than ivory, and with bows made from Titania's eyelashes scrape away at the strings made of spider’s thread; the little wig with triple curls, worn by the beetle who acts as conductor, quivers with pleasure, and scatters luminous powder around, so sweet is the harmony and so well executed the overture!

A curtain woven of butterfly wings, thinner than the inner membrane of an egg, rises slowly after the three initial and obligatory chords. The room is full of the souls of poets seated in mother-of-pearl stalls, watching the spectacle through drops of dew mounted on the golden pistils of lily flowers which form their opera-glasses.

The sets are unlike any known before; the countries they represent are more unknown to us than America prior to its discovery. The palette of the richest painter bears not half the hues with which they are decorated: everything is painted in strange and singular colours. Ash-green, ash-blue, ultramarine, yellow, and crimson lacquers are lavished on them.

The sky, a greenish-blue, is striped with broad pale and tawny bands; the foliage of small, slender, spindly trees, the colour of a dried rose, sways in the background; the landscape, instead of drowning in azure vapour, is the most beautiful apple-green, and spirals of golden smoke escape from it here and there. A stray shaft of light catches the pediment of a ruined temple, or the spire of a tower. Cities full of bell-towers, pyramids, domes, arches, and ramparts, sited on the hills, are reflected in crystal lakes; the intertwined trunks and branches of tall trees with broad leaves, cut by the feys with magic scissors, form the wings. Snowy clouds gather above them, and deep in the trees’ cracks and hollows one can see the glittering eyes of dwarves and gnomes, while the twisted roots plunge into the ground like the fingers of giant hands. Woodpeckers strike the trunks in time with their hard beaks, as emerald lizards bask in the sun, on the moss at their feet.

Sunset by the Ruins

Hermann David Salomon Corrodi (Italian, 1844-1905)

Artvee

Mushrooms watch the comedy, hats on heads, like the insolent folk they are, while charming violets stand on tiptoe between the blades of grass, opening wide blue eyes, to see the hero pass by. Bullfinches and linnets lean from the tips of the branches to prompt the actors.

Through the tall grasses, and purple thistles, and burdocks with velvet leaves, streams of tears from baying stags wind, like silver snakes. From time to time, anemones gleam on the lawn like drops of blood, and daisies raise their heads laden with crowns of pearls like duchesses.

The characters are of no known time or country; they come and go without anyone knowing how or why; they neither eat nor drink, they live nowhere, and do no work; they have neither land, income, nor houses; though sometimes they carry under one arm a small box full of diamonds as big as pigeon’s eggs; as they pass by, not a single drop of rain falls from the tips of the flowers, nor does a single grain of dust rise from the roads.

Their clothes are the most extravagant and fanciful in the world. Hats pointed like steeples, their brims as wide as Chinese parasols, adorned with enormous feathers plucked from the tails of phoenixes and birds of paradise; capes striped in brilliant colours, doublets of velvet and brocade that reveal their satin or silver cloth lining through gold-laced slits; breeches puffed out, inflated like balloons; scarlet stockings with embroidered heels; high-heeled shoes with large rosettes; small, slender swords, blades in the air and hilts pointing downward, decorated with braid and ribbons; that’s how the men are clothed. The women are no less curiously dressed.

The drawings of Stefano della Bella and Romeyn de Hooghe would serve to represent the character of their attire: full-bodied, undulating dresses, with wide pleats that shimmer like turtledoves’ throats and reflect the changing hues of the iris-flowers; large sleeves; corsets loaded with bows and embroidery; braided cords, curious jewels, aigrettes of heron-feathers, necklaces of huge pearls, peacock-tail fans with mirrors at their centres; little mules and pattens; garlands of artificial flowers, sequins, and gauze in gold and silver lamé; rouge, beauty-spots; everything that can add interest and piquancy to a theatrical toilette.

The style is neither precisely English, nor German, nor French, Turkish, Spanish, or Tartar, though it includes a little of all these, adopting from each country all that is most graceful and characteristic. Actors so dressed can speak as they wish, without concerning themselves with verisimilitude. Fantasy has run riot everywhere, fashion unfurls its variegated coils at ease, like a snake warming itself in the sun; the most exotic conceits open their singular blooms fearlessly, and spread about them perfumes of amber and musk. Nothing constrains them; neither place, name, nor costume.

How amusing and charming their speeches! These fine actors are not those screechers of the playhouses, mouths distorted, eyes bulging to add effect to their tirades; they never present themselves like workers pursuing a task, oxen yoked to the action, and hastening to finish; they are free of chalk and rouge plastered half an inch thick; they wield no daggers made of tin, nor hide pig’s bladders filled with chicken’s blood under their coats; nor drag the same oil-stained rag around for entire acts.

They speak without haste, without shouting, like people in company who attach scant importance to their actions: the lover makes his declaration to his beloved with the most detached air in the world; while talking, he taps his thigh with the tip of his white glove, or adjusts his adornments. The lady, in turn, nonchalantly shakes the dew from her bouquet, and strikes poses along with her maid; the lover cares little about wooing his lady: his principal business is to let fall, from his lips, streams of pearls, and cascades of roses, and scatter poetic gems like a true worker of miracles; often he even retires completely, and lets the author woo his mistress for him. Jealousy is not a fault of his; his nature is most accommodating. With his eyes raised to the airy cornices and friezes of the theatre, he waits, complacently, for the poet to finish saying whatever caught the latter’s fancy before resuming his role and kneeling before her again.

Everything is tied and untied with admirable carelessness: effects lack cause, and causes have no effect; the wittiest character is the one who talks the most nonsense; the most foolish person utters the wittiest things; young girls say things that would make courtesans blush; courtesans reel off moral maxims. The most unheard-of adventures follow one another in quick succession without being explained; the noble father arrives expressly from China, in a bamboo junk, to reclaim his kidnapped daughter; the gods and feys do little but descend and ascend in their machines. The action plunges beneath the topaz domes of the ocean waves, and wanders the sea-bed, through forests of coral and madrepores, or rises to the sky on lark’s wings, or those of a griffin. The dialogue is universal; the lion contributes with a vigorous roared ‘Oh’ (see Shakespeare’s ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ Act V, Scene I, Snug as the lion) the wall speaks through its crannied hole or chink (ditto: Snout, as the wall), and, provided they have a remark, disguise or pun to add, all are free to interrupt the most interesting of scenes: Bottom’s ass’s head is as welcome as Puck’s blonde one; the author’s spirit is seen there in all forms; and all these contrasts are like so many facets which reflect different aspects, adding their prismatic colours.

This apparent chaos and disorder, this fantastic guise, ultimately renders real life more accurately than the most minutely studied drama of morals. Each character contains the whole of humanity within, and by uttering what comes into their head succeeds far better than a copyist with a magnifying glass in portraying objects without.

O fair throng! Romantic young lovers, vagabond damsels, obliging attendants, caustic jesters, naive servants and peasants, good-natured kings, often with names unknown to the historian and kingdoms unknown to the geographer; colourful ‘fools’, clowns of sharp repartee and miraculous capers; O you, above all, who let free caprice speak through your smiling mouths, I love and adore you: Perdita, Rosalind, Celia, Pandarus, Parolles, Silvia, Leander, and the rest; you, charming types, products of artifice and yet so true, who, on the colourful wings of fancy, rise above gross reality; you, in whom the poet personifies his joy, his sadness, his love and his most intimate dreams under the most frivolous and impersonal of masks.

In this form of theatre, written for feys, and to be performed by moonlight, there is one piece which delights me most; it is a play so errant, so vagabond, whose plot is so wayward, and the characters so singular, that Shakespeare himself, not knowing what title to give it, called it ‘As You Like It’, an adaptable name, that suits the whole.

In reading that strange play, one feels transported into an unknown world, of which one nevertheless has some vague reminiscence: one no longer knows whether one is dead or alive, whether one is dreaming or awake; graceful figures smile at you gently, and throw you, as they pass, a friendly hello; you feel moved and troubled at the sight of them, as if, at the bend of a road, you suddenly encountered your ideal, or the forgotten ghost of your first mistress suddenly stood before you. Springs flow, murmuring half-stifled complaints; the wind stirs the old trees of the ancient forest over the head of the old exiled duke, with compassionate sighs; and, when the melancholic Jaques lets his philosophical complaints flow with the willow leaves, it seems to you that it is you yourself that speaks, and that the most secret and obscure thought of your heart is revealed and illuminated.

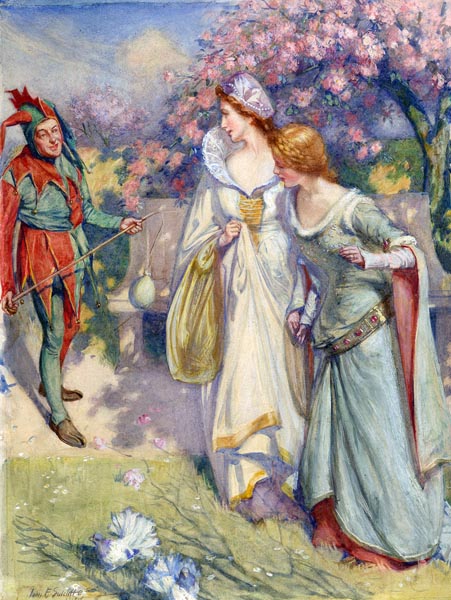

As you like it, act 1, scene 2 (1901)

John E. Sutcliffe (English, 1876-1923)

Artvee

O youngest son (Orlando), so mistreated by fate, of the brave knight Rowland de Boys! I cannot help being jealous of you; you still have a faithful servant, Adam, whose old age is green beneath his snowy hair. You are banished, but at least you are banished after having fought and triumphed; your wicked brother robs you of all your wealth, but Rosalind gives you the chain from her neck; you are poor, but you are loved; you leave your country, but the daughter of your persecutor follows you beyond the sea.

The trees of the forest of Arden open great arms of foliage to receive and hide you; that good forest, so as to lodge you, gathers silkiest moss from deep in its caves; it inclines its arched branches over your head to protect you from rain and sun; the tears of its founts show their pity for you, as do the sighs of its fawns, and the baying of its stags; it makes of its rocks pleasant writing-desks for your amorous epistles; it lends you its thorn-bushes to hang them from, and commands the satin bark of its aspens to yield to the point of your stylus whenever you wish to engrave Rosalind’s name there.

If only, Orlando, one had, like you, a large, shady forest to retreat to, there to isolate oneself in one’s sorrow, and if, at the turn of an alley, one could meet the one who is sought, recognisable, through their disguise! But, alas, the world of the spirit owns to no verdant Arden, and it is only in the flowery beds of poetry that the capricious little wild-flower blooms, whose perfume makes one forget all. We shed tears, but they do not flow as beautiful silvery cascades; we sigh, but no complacent echo troubles to return our complaints, adorned with assonance and conceits. In vain we hang our sonnets on the prickly brambles, Rosalind never reads them; and we carve amorous ciphers on the tree-bark to no purpose.

Birds of the sky, each of you lend me a feather, the swallow and the eagle, the hummingbird and the rock dove, so that I may make a pair of wings for myself, so as to fly high and swiftly through unknown regions, where I shall find nothing that recalls the cities of the living, where I can forget that I am myself, and live a strange, new life, beyond America, Africa, Asia, beyond the last isle of the world, across the northern ice, beyond the pole where the aurora borealis trembles, in that impalpable kingdom to which the divine creations of poets, and examples of supreme beauty, take flight.

How can one endure the ordinary conversations of our circles and salons, once one has heard you speak, glittering Mercutio, whose every sentence bursts in showers of siler and gold, like firework rockets beneath a sky strewn with stars? Pale Desdemona, what pleasure do you expect us to take in earthly music, after the romance of your ‘Willow Song’? What woman can seem beautiful, faced with your Venuses, you ancient sculptors, you poets of the marble stanza?

Ah! Despite the furious embrace in which I have sought to clasp the material world, lacking the other, I feel that I am ill-born, that life was not fashioned for me, and repels me. I cannot mingle with the crowd: yet whatever path I follow, I go astray; the trim alley, the rock-strewn track, lead me equally to the abyss. If I wish to take flight, the air congeals around me, and I remain captive, my wings spread, and I unable to close them. I can neither walk nor fly; on earth, the sky attracts me, the earth when I mount the sky; on high, the north wind tears my feathers from me; below, the pebbles offend my feet. These feet are far too tender to tread the glass shards of reality; my wingspan is too narrow to hover high above things, or rise, from circle to circle, in the mystical azure, and attain the inaccessible summit of eternal love; I am the most unfortunate hippogriff (see Ariosto’s ‘Orlando Furioso’), the most miserable collection of heterogeneous fragments that has ever existed since the Ocean fell in love with the Moon, and women chose to deceive men. The monstrous Chimera, put to death by Bellerophon, with her virgin’s head, lion’s paws, goat’s body and dragon’s tail, was an animal simply composed compared to me.

In my frail breast dwell the violet-strewn reveries of a modest girl, and the mad ardour of an orgiastic courtesan: my desires stray, like lions sharpening their claws in the shadows, seeking something to devour; my thoughts, more feverish and more restless than those of goats, cling to the most threatening cliffs; my hatred, bloated with venom, twists scaly folds in inextricable knots, and drags itself endlessly through ruts and ravines.

My soul is a strange country, flourishing and splendid in appearance, but moist with more putrid and deleterious marshes than the shores of Batavia: the slightest ray of sunlight on the mud there causes reptiles to hatch and mosquitoes to swarm; the large yellow tulips, the nagassari and ashoka flowers, veil, in their pomp, filthy carrion. The amorous rose opens its scarlet lips, and shows its little dew-wet teeth, smilingly, to the gallant nightingale, who recites to it madrigals and sonnets: nothing is more charming; but I wager that, in the grass, in the shade of the rose-bush, a dropsical toad crawls on lame legs, silvering the path with its slime.

Here are springs clearer and more limpid than purest diamond; but it would be better to draw stagnant marsh water from beneath a mantle of rotting rushes, and drowned dogs, than to dip your cup in this wave. A serpent haunts the depths, and twines about itself with frightening rapidity, while disgorging its venom.

Plant wheat, and asphodel, henbane, darnel, and pale hemlock with its greyish-green branches will grow. Instead of the roots you buried, you’ll be surprised to find hairy, twisted tentacles of black mandrake emerging from the ground.

If you leave a souvenir here, and return later to collect it, you’ll find it greener with moss, teeming more busily with woodlice, and fouler insects still, than a stone left on a damp cellar floor.

Don’t try crossing the dark forests; they are more impassable than the virgin forests of America, or the jungles of Java: lianas as strong as cables run from tree to tree; plants, leaves bristling and pointed like spearheads, obstruct your passage; the grass-blades themselves are like downy stinging nettles. From arches of foliage, gigantic vampire bats hang by their claws; scarabs of vast size shake threatening antennae, and whip the air with their quadruple wings; monstrous creatures of fantasy, like those seen in nightmares, advance, painfully, shattering the reeds before them. There are herds of elephants, whose dry and wrinkled skin crushes flies, or that rub their flanks across stones and trees; rhinoceroses, with rough hides; and hippopotami, whose bloated muzzles bristle with hair, ploughing and kneading the forest’s mud and detritus with their broad feet.

In the clearings, where the sun’s luminous rays cut golden wedges through the moist air, where you might hope to rest yourself, you’ll forever find some streak of tigers casually lying, sniffing the air, blinking their sea-green eyes, and licking their velvet fur with crimson, papillae-covered tongues; or some knot of boa constrictors half-asleep, digesting the bull they last swallowed.

Fear everything: grass, fruits, water, air, shade, sun; all are deadly. Close your ears to the chatter of the parakeets with golden beaks and emerald necks that hop down from the trees, and perch on your fist, fluttering their wings; for, with their pretty golden beaks, those little parakeets with emerald necks will gently gouge out your eyes the moment you stoop to kiss them. That’s how things are!

The world does not want me; it rejects me, as if I were a ghost escaped from the tomb; I’m almost as pallid as one: my blood refuses to accept that I’m alive, and fails to colour my skin; it drags, itself slowly, through my veins, like stagnant water in a clogged canal. My heart beats at nothing that makes a man’s beat. My sorrows and joys are not those of humankind. I violently desire what none desire; yet I disdain what others desperately seek. I have loved women who bore no love for me, and have been loved when I had rather been hated: always too soon or too late, less or more, below, beyond; never what was needed; either I failed to arrive, or travelled too far. I have scattered my life from the window, or focussed it to excess on a single point, and from the restless activity of the ardelio (busybody) have attained the gloomy drowsiness of the tiryaki (addict), or the stasis of a Stylite (ascetic) on his column.

Whatever I do always seems like a dream; my actions seem more the outcome of somnambulism than free will; there is something in me, felt obscurely, deeply within, that makes me act without my own involvement and always outside of the common law; the simple, natural aspect of things reveals itself to me only after every other has done so, and I grasp, first of all, the bizarre: if a line is a little skewed, I will soon turn it into a spiral, more twisted than a snake; contours, if they are not carved in the most precise of manners, quickly seem blurred and deformed. Figures take on a supernatural air, and gaze at me with a dreadful gaze.

Also, through a kind of instinctive reaction, I have always desperately clung to the material, the external features of things, and have given a deal of space in my life to the plastic arts. I comprehend statues perfectly, yet I fail to understand human beings; when life arises, I halt and recoil in terror, as if I had seen Medusa’s face. The mere phenomenon of life itself causes me a degree of astonishment from which I fail to recover. I will doubtless make an excellent corpse, given I make a poor show as a living being, while the point of my existence escapes me completely. The sound of my own voice startles me, unimaginably, and I often mistake it for the voice of another. When I want to stretch out my arm, and it obeys me, it seems to me quite a prodigious thing, and I fall into the most profound stupefaction.

And yet, Silvio, I understand what is unintelligible to others perfectly; the most extravagant things seem natural to me, and I enter into them with singular ease. I follow the most capricious and disorganised of nightmares easily. That is the reason why the kind of theatre I was speaking of just now pleases me above all others.

I have lengthy discussions with Théodore and Rosette on this subject: Rosette has little taste for my system, she is for actual reality; Théodore allows the poets more latitude, and admits a truth derived through artificial conventions, and visual effects. I maintain the field must be left completely free to the author, and that fantasy should reign supreme.

Many of my companions, based their argument mainly on the fact that such plays were generally beyond the scope of theatrical effects, and were thus unperformable. I replied that this was true in one sense and false in another, like almost everything else that is said, and that their ideas regarding the possibility and impossibility of staging such pieces seemed to me lacking in accuracy and derived from prejudice rather than reason, and I claimed, among other things, that ‘As You Like It’ was certainly very performable, especially for amateurs unaccustomed to playing other roles.

This gave rise to the idea of actually enacting it. After all, the season is drawing on, and every kind of amusement has been exhausted; people are weary of hunting, riding, and water-play; and card-games like Boston, however varied they may be, lack enough interest to occupy an evening, so the proposal was received with universal enthusiasm.

A young fellow who knew how to paint a scene offered to do the sets; he is working on them, at present, with great ardour, and, in a few days, they’ll be finished. A stage has been erected in the orangery, which is the largest room in the château, and I think all will go well. I am to play Orlando; Rosette was to play Rosalind, as was only fair. Being my mistress, and mistress of the house, the role belonged to her by right; but she disdains to disguise herself as a man, due to some singular whim of her own, of which prudishness is certainly not the cause. If I had not been certain of the contrary, one would have thought she wished to hide ill-shaped legs. Currently, none of the society ladies wish to show themselves as any less scrupulous than Rosette, and this almost caused the idea to be abandoned; but Théodore, who had accepted the role of the melancholic Jaques, offered to replace her, since Rosalind is almost always in male disguise, except in the first act, where she is in female dress; and with makeup, a corset, and a gown he will be able to maintain sufficient illusion, not yet possessing a beard, and being very slim.

We are learning our parts, and it is a curious thing to see. In every solitary corner of the park, you are sure to find someone, script in hand, muttering their lines under their breath, raising their eyes to heaven and suddenly lowering them, and repeating the identical gesture seven times or more. If one did not know we are about to play a comedy, we might certainly be taken for a house of madmen or poets (which is well-nigh a tautology).

I think we’ll soon be ready to hold a rehearsal. I expect something very singular. Perhaps I am wrong. I was afraid, at first, that instead of acting in an inspired manner our actors would try to reproduce the poses, and inflections of voice, of some fashionable player of comedy; but fortunately they have not followed the theatre with sufficient zeal to fall into this error, and I believe they will display, due to their awkwardness, being folk who have never acted on stage, precious flashes of naturalness, and the charming naiveté the most consummate talent cannot reproduce.

Our young painter has truly worked wonders: it would be impossible to give a more whimsical turn to the old tree trunks, and the ivy that entwines them; he has modelled them on those in the park, accentuating and exaggerating them, as should be the case as regards a stage-set. Everything is done with admirable liveliness and caprice; the stones, the rocks, the clouds are of a mysteriously steely form; reflections play on the trembling waters, shimmering more than quicksilver, and the usually chilly foliage is marvellously enhanced with saffron tints applied with an autumnal brush; the forest varies from emerald-green to a carnelian purple; the warmest and freshest tones merge harmoniously, and the sky itself passes from tenderest blue to the most ardent of colours.

He has also designed all the costumes according to my instructions; they are of the loveliest character. At first, there arose a cry that they could never be translated into silk and velvet, nor any known fabric, and I almost dreaded the moment when troubadour costume might be generally adopted. The ladies said that such bright colours would eclipse the light of their eyes. To which I replied that their eyes were perfectly inextinguishable stars, and that it was, on the contrary, their eyes that would eclipse the colours, and even the oil lamps, the chandelier, and the sun, if needs be. They made no reply to this; yet a bristling host of other objections appeared, like the tentacles of the Lernaean Hydra; no sooner had the tip of one been severed, than another reared its head, more stubborn and stupid than ever.

— ‘How do you expect that to hold up?’ — ‘It’s all fine on paper, but something else on one’s back.’ — ‘I’ll never get into that!’ — ‘My petticoat’s at least four inches too short.’ — ‘I’d never dare show myself in this!’ — ‘This ruff’s too tall; I look like a hunchback with no neck.’— ‘This hairstyle ages me intolerably’.

— ‘With starch, and pins, and goodwill, everything will be fine.’ — ‘Are you joking! With a waist like yours, slenderer than a wasp’s, one that would fit through the ring on my little finger! I wager twenty-five louis against a kiss that the bodice will have to be made shorter.’ — ‘Your skirt is far from being too short, and if you could see what adorable legs you have, you’d certainly be of my opinion.’ — ‘On the contrary, your neck stands out admirably well in your lace halo.’ — ‘That hairstyle doesn’t age you at all, and, even if it made you look a few years older, you’re so exceedingly young that it couldn’t matter less; in truth, one would suspect you were barely an adult, if one did not know where the pieces of your last doll lie scattered’... et cetera.

You cannot imagine the prodigious quantity of compliments I was obliged to offer, to force our ladies to wear those charming costumes which suit them perfectly.

I also had a deal of trouble getting their fascinators adjusted properly. What devilish taste women have! And what titanic stubbornness is possessed by some vaporous little mistress who believes that a cold straw-yellow suits her better than daffodil, or bright pink. I am sure if one were to apply to public affairs half the tricks, and half the intrigue I did to have a red plume worn on the left, and not on the right, one could easily become Emperor, or a Minister of State at the very least.