Théophile Gautier

Captain Fracasse (Le Capitaine Fracasse)

Part III: Chapters XI-XV

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter XI: The Pont-Neuf.

- Chapter XII: The Crowned Radish.

- Chapter XIII: A Dual Assault.

- Chapter XIV: Lampourde’s Delicacy.

- Chapter XV: Malartic at Work.

Chapter XI: The Pont-Neuf

It would make for a long and tedious narrative if I were to follow the Chariot of Comedy step by step to the great city of Paris; nothing that deserves to be recounted occurred on the journey. Our actors possessed a well-lined purse and progressed briskly, being able to hire horses, and pay their way. The troupe halted at Tours and Orléans to deliver a few performances whose takings satisfied Herod, more sensitive in his capacity as manager and cashier to monetary success than the others. Blazius began to reassert himself, and laugh at the terrors that Vallombreuse’s vindictiveness had inspired in him. Meanwhile Isabella still trembled at the thought of the unsuccessful abduction attempt, and although at the various inns she shared a room with Zerbina, she more than once, in dream, thought she saw the wild and haggard face of Chiquita emerging from that black opening, with a show of white teeth. Frightened by the vision, she would wake screaming, and her companion had difficulty calming her. Without otherwise displaying concern, Sigognac slept in the nearest room, his sword under his head and fully dressed, in case of some nocturnal altercation. During the day, he usually walked on foot, ahead of the wagon, as a scout, especially when bushes, coppices, sections of walls or ruined cottages near the road might have served as a place for an ambush. If he saw a group of travellers of suspicious appearance, he would fall back to the cart where the Tyrant, Scapin, Blazius, and Leander represented a respectable garrison, though of the latter two one was old and the other as timid as a hare. At other times, like an experienced general who knows how to detect the enemy’s feints, he remained in the rearguard, since the danger might just as easily come from that direction. But his precautions were redundant and proved supererogatory. No attack came to surprise the troop, either because the Duke had not had time to organise one, or because he had relinquished the idea, or because the pain of his wound had damped his courage.

Although it was winter, the season was not too harsh. Being well-fed, and having taken care to buy warm clothes thicker than the serge of theatrical coats, the actors suffered little from the cold, and the north wind caused no other inconvenience than to make the young actresses’ cheeks appear a little more vivid than usual, sometimes even extending to their delicate noses. These winter roses, though a little out of place, did not suit them too badly, for well-nigh everything suits pretty women. As for Dame Leonarda, her complexion, created by forty years of the Duenna’s rouge, was unalterable. A north wind, and a north wind only, rendered it paler.

Finally, around four in the evening, they arrived at a place very near to the great city, on the banks of the Bièvre, where one crosses the culvert that joins the Seine, that illustrious river whose waters have the honour of bathing the palace of our kings, and many another building renowned throughout the world. The smoke disgorged from the house chimneys masked the horizon with a broad cloud of half-transparent red mist, behind which the sun was setting, dull red and stripped of its rays. Against this half-lit background, the silhouettes of the private and public buildings, and churches, embraced by the view from that point, were outlined in purplish grey. On the other side of the river, beyond the Île Louviers (no longer an island), the bastion of the Arsenal, and the Couvent des Célestins, could be seen, and in front to the left, the tip of the island of Notre-Dame. Once past the Porte Saint-Bernard (on the left bank, not extant), the spectacle was magnificent. Notre-Dame appeared in full view, the apse, with its flying buttresses resembling gigantic fish ribs and its sharp spire, planted above the intersection of the naves, fronting the two square towers. Other, humbler bell-towers, rising above the roofs of churches and chapels themselves buried amidst the crowd of houses, lifted into the clear band of sky, but the cathedral especially drew the gaze of Sigognac, who had never seen Paris, and was astonished by the building’s grandeur.

The movement of the carriages laden with various goods, the tumultuous mass of horsemen and pedestrians traversing the banks of the river, and the streets that led from it, into which the wagon sometimes entered so as to take the shortest route, and the cries of the crowd dazzled and stunned him, being accustomed to the vast solitude of the moors, and the deathly silence of his old and dilapidated castle. It seemed to him as if a millstone was turning in his head, and he felt himself to be staggering like a drunken man. Soon the beautifully crafted needle of the Sainte-Chapelle soared above the roofs of the Palais de la Cité (including the extant Palais de Justice), penetrated by the last glimmers of sunset. The lamps now being lit pricked the dark facades of the houses with red dots, and the river reflected these glimmers stretching like serpents of fire over its black waters.

Soon, the church and cloister of the Grands-Augustins appeared amidst the shadows along the quayside, and on the platform of the Pont-Neuf, Sigognac saw to his right the outline of the equestrian statue of Henry IV, visible despite the growing darkness; but the wagon turned the corner of the Rue Dauphine (created in 1607) piercing the convent grounds, and the rider and horse swiftly vanished.

There was at the top of the Rue Dauphine, near the gate of that name, a vast hostelry where embassies from strange and unknown lands sometimes stayed. This inn could receive numerous companies of travellers at a moment’s notice. Horses and mules were always sure to find hay in the racks, and their owners never lacked for beds. It was this hostelry that Herod had chosen, as a propitious place for his theatrical troupe to lodge.

‘The Hostelry on the Rue Dauphine.’

The brilliant condition of his purse allowed this luxury; a useful luxury, moreover, because it elevated the troupe’s standing by showing that it was not composed of vagabonds, swindlers and debauched people, forced by poverty into this unfortunate profession of provincial histrions, but rather of brave actors whose talents brought them an honest income, which is it seems possible, for the reasons given by Pierre de Corneille, in his play L’Illusion Comique (of 1636, see Alcandre’s speech at the end of Act V).

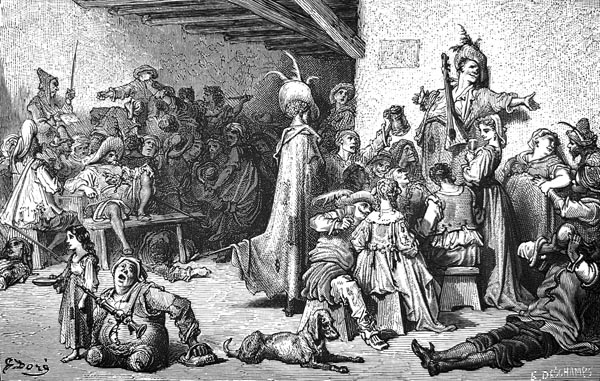

The kitchen the actors entered, while waiting for their rooms to be prepared, was large enough to accommodate, comfortably, a dinner for Gargantua or Pantagruel. At the rear of the immense fireplace, whose opening was as red and flaming as the mouth of Hell is represented in La Grande Diablerie de Doué, whole tree-trunks were burning (Rabelais mentions the Diableries which took place at Doué-la-Fontaine, Maine et Loire, and elsewhere, in ‘Gargantua and Pantagruel’, see Book 3: III, Book 4: XIII, and Book IV: LII. These were parodies of the Mysteries of the Passion, which had led to the banning of the Mystery plays in 1548). On several spits, one above the other, turned by a dog struggling like a creature possessed inside a wheel, strings of geese, pullets, and capons were turning golden, sides of beef were roasting, loins of veal were browning, not to mention partridges, snipe, quail, and other small game. A scullion, half-cooked himself and dripping with sweat though he was wearing no more than a simple canvas jacket, was basting these victuals, plunging his spoon into the dripping pan again, as soon as he had poured out its contents: a real Danaidean labour, since the liquid collected was forever released.

Around a long oak table, covered with dishes being prepared, a whole world of anatomists, cooks, and sauce-makers, busied themselves, from whose hands their assistants received the larded, trussed, spiced cuts, to carry them to the stoves which, incandescent with embers and crackling with sparks, resembled Vulcan’s forges more than culinary ovens, the boys looking like Cyclopes through the fiery mist. Along the walls shone a formidable battery of red-copper and brass cookware: cauldrons, saucepans of all sizes, fish-kettles for cooking leviathans in court-bouillon broth, pastry moulds fashioned into dungeons, domes, little temples, and Saracenic helmets and turbans, in short, all the offensive and defensive weapons that the arsenal of the god of Gastronomy contains.

Every moment some sturdy servant girl, with plump, ruddy cheeks like those the Flemish painters depicted in their art, would arrive from the pantry, carrying baskets full of provisions on head or hip.

— ‘Pass me the nutmeg!’ some cook cried — ‘A little cinnamon!’ cried another — ‘The four spices over here!’ — ‘Fill the salt shaker! Cloves! Bay leaves!’ — ‘A strip of bacon, if you please, sliced thin!’ — ‘Fire up this stove; it’s cooling! And damp the other, it’s too hot, everything will burn like chestnuts left in the pan!’ — ‘Pour some liquid into this puree!’ — ‘Thin out this butter and flour, it’s thickening!’ — ‘Beat these egg whites, as fiercely as ‘Père Fouettard’ (who on Saint Nicholas Day, 6th December, dispenses beatings to naughty children), they’re not foaming enough!’ — ‘Sprinkle breadcrumbs on that hock of ham! Draw that gosling from the spit, it’s ready! Five or six more turns for that chicken! Quick, quick, take the beef away! It should be rare. But leave the veal and the chickens:

Raw chicken, and ill-cooked veal,

Gift the graveyard worms a meal.

Remember that, you rascal. Not everyone can roast well. It’s a gift from heaven. Take this soup to the princess at table six. Who asked for the quail gratin? Quickly, ready this saddle of spiced hare!’ Thus, amidst a cheerful tumult, alimentary exchanges and culinary rants criss-crossed, justifying their title better than the icy words Panurge handed out at the melting of the Frozen Sea (see Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel, Book IV: LVI), for they all related to some dish, condiment, or delicacy.

Herod, Blazius, and Scapin, who were gourmands, and devoutly greedy like cats, licked their lips at this delivery of exceedingly plump, succulent, and well-fed eloquence, which they said they highly preferred to that of Isocrates, Demosthenes, Aeschines, Hortensius, or Cicero, and other such chatterers whose sentences were nothing but hollow bones lacking in marrow juice. ‘I have a longing’ said Blazius, ‘to kiss, and on both cheeks, that fat cook, as large and pot-bellied as a monk, who rules all these saucepans with such a superb air. Never was a captain more admirable under fire!’

At the very moment a servant came to inform the actors that their rooms were ready, a traveller entered the kitchen, and approached the fireplace. He was a man of about thirty, tall, thin, vigorous, with an unpleasant, though regular, physiognomy. The light from the hearth endowed his profile with a fiery edge, while the rest of his face was bathed in shadow. Its luminous touch emphasised a somewhat prominently arched eyebrow sheltering a hard and scrutinising eye, a nose of aquiline curvature whose tip curved back to form a hooked beak above a thick moustache, and a very thin lower lip which merged abruptly with a short, squat chin as if nature had lacked the material to complete the face. The lean neck, exposed by a flap of starched batiste, revealed in its thinness that protruding cartilage that old wives claim to be a piece of the fatal apple remaining in Adam’s throat, which some of his descendants have not yet swallowed. His costume consisted of a doublet of iron-grey cloth beneath a buff jacket, brown breeches, and felt boots, reaching above the knee and folding in spiral layers about his legs. Numerous specks of mud, some dry, others still fresh, indicated a long journey, and the spurs, reddened with blackish blood, said that, to reach the end of it, the rider had been forced to savagely wound the flanks of his weary mount. A long rapier, whose wrought iron basket-hilt must have weighed more than a pound, hung from a wide leather belt fastened by a copper buckle clinched about the man’s thin spine. A dark-coloured cloak and hat, both of which he had thrown onto a bench, completed the account of his attire. It would have been difficult to determine to what class the newcomer belonged. He was neither a merchant, nor a bourgeois, nor a soldier. The most plausible supposition would have placed him in the category of those poor gentlemen or minor noblemen who become servants to some great man and attach themselves to his company.

Sigognac, who was not a man of the kitchen like Herod or Blazius, and therefore not absorbed in contemplation of those magnificent victuals, looked with a certain curiosity at this tall fellow whose physiognomy seemed somehow familiar to him, though he could not remember where or when he had encountered it. In vain he summoned up his memories, but failed to find what he was searching for. However, he felt, confusedly, that this was not the first time he had found himself in contact with this enigmatic personage who, little concerned about the former’s inquisitive examination of his features, of which he seemed to be aware, turned his back completely upon the room and leant towards the fireplace under the guise of warming his hands more effectively.

As his memory provided him with nothing precise, and any longer insistence might have given rise to a useless quarrel, the Baron followed the actors, who took possession of their respective lodgings, and after having made a brief toilette, gathered in a lower room where supper was served, which they celebrated being hungry and thirsty people. Blazius, clicked his tongue, proclaimed the wine good, and poured himself numerous full glasses, without forgetting those of his comrades, for he was not one of those selfish drinkers who worship Bacchus alone; he loved to drink with others almost as much as drinking by himself; the Tyrant and Scapin granted him the opportunity; Leander feared, by indulging in too frequent libations, that he might impair the whiteness of his complexion, while adorning his nose with those bumps and pimples unsuitable as ornaments for a lover. As for the Baron, the long periods of abstinence suffered at the castle of Sigognac had developed in him a habitual Castilian sobriety which he was able to forego only with difficulty. He too was preoccupied with the character glimpsed in the kitchen, whom he found to be suspicious without being able to say why, since nothing was more natural than the arrival of a traveller at a well-stocked inn.

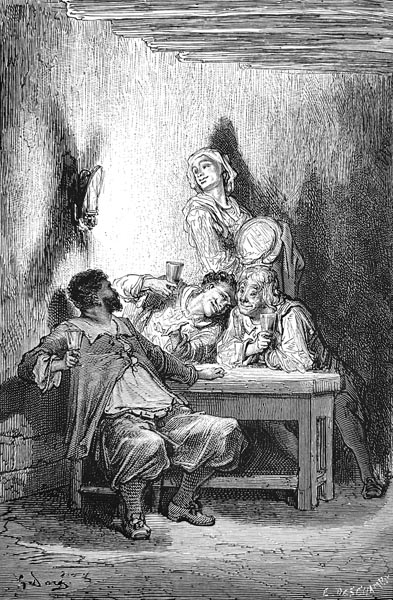

The meal was a cheerful one. Enlivened by wine and good food, joyful at being, at last, in Paris, the Eldorado of all people with ambitions to fulfil, and imbued with a warm glow, so pleasant after long hours spent in the cold wagon, the actors indulged in the wildest hopes. They rivalled in their opinion the troupes of the Hôtel de Bourgogne (the first permanent theatre in Paris, built in 1548 on the ruins of the palace of the dukes of Burgundy, on the Rue Mauconseil, later the Rue Étienne Marcel, and home to the Comédiens du Roi, from 1628) and the Théâtre du Marais (on the Vieille Rue du Temple, founded 1634). They saw themselves applauded, feted, summoned to court, able to commission plays from the finest minds of the time, treating poets as mere scribblers, invited to feasts by great lords, and riding in carriages. Leander dreamed of the most elevated conquests, and it was even uncertain if he would consent not to seduce the queen. Though he had drunk nothing, he was intoxicated with vanity. Since his affair with the Marquise de Bruyères, he believed himself utterly irresistible, and his self-esteem knew no bounds. Serafina promised herself that she would remain faithful to the Chevalier de Vidalinc only until the day a finer, and more eligible, suitor presented himself. As for Zerbina, she had her marquis who was soon to join her, and no further ambition. Dame Leonarda, being excluded by reason of her age, and able only to serve as a messenger, like Iris (female messenger to the Greek gods, embodied by the rainbow), found these trivialities unamusing, and failed to waste a single bite of the dinner before her. Blazius loaded her plate and filled her goblet to the brim with comical rapidity, a jest that the old woman accepted with good grace.

Isabella, who had long since stopped eating, absentmindedly rolled a ball of bread-crumbs between her fingers, shaping it into a dove and rested her eyes, bathed in chaste love and angelic tenderness, on her dear Sigognac, seated at the other end of the table. The warmth of the room had brought a delicate blush to her cheeks, which had recently been somewhat pale from the fatigue of the journey. She looked adorably beautiful like that, and if the young Duke of Vallombreuse had been able to see her at that moment, his emotions would have been exasperated to the point of rage.

For his part, Sigognac contemplated Isabella with respectful admiration; the beautiful feelings expressed by this charming girl touched him as much as the attractions with which she was abundantly endowed, and he regretted that, through excess of delicacy, she had refused him as a husband.

When supper was over, the women withdrew, along with Leander and the Baron, leaving the trio of accomplished drunkards to finally empty the bottles, a procedure which seemed far too meticulous to the servant in charge of serving drinks, but a thoroughness for which a solid silver coin consoled him.

‘…The women withdrew…leaving the trio of accomplished drunkards.’

— ‘Barricade yourself in your chamber,’ said Sigognac, escorting Isabella to the door of her room. ‘There are so many strangers in these inns one cannot take too many precautions.’

— ‘Fear not, dear Baron,’ replied the young actress, ‘my door is locked with a triple lock that would secure a prison-cell. There is a bolt as long as my arm as well; the window is barred, and there is no hole like a bull’s-eye in the wall gazing out of its dark pupil. Travellers often have valuables that might tempt thieves’ greed, so the rooms in hostelries are always hermetically sealed. Never has a fairy-tale princess threatened with a spell been safer in her tower guarded by dragons.’

— ‘Sometimes,’ replied Sigognac, ‘enchantment is not needed, and the enemy enters without the use of charms, incantations, or conjurations.’

— ‘Because the princess,’ Isabella replied, smiling, ‘chose to favour that enemy through her own curiosity or amorous complicity, wearying of being so secluded, even though it was for her own good; which is not my case. Therefore, since I am not afraid, I who am by nature as timid as a doe at the sound of the hunting-horn and the baying of hounds, you should be reassured, you who are equal in courage to Alexander or Caesar. Sleep soundly.’

And as a sign of farewell, she extended to Sigognac’s lips a soft and slender hand whose whiteness she knew how to preserve as well as any duchess, by the use of talcum-powder, cucumber cream, and gloves treated with a preparation. Once she was within, Sigognac heard the key turn in the lock, the latch slide home, and the bolt creak in its slot in the most reassuring way; yet, as he reached the threshold of his own room, he saw the shadow of a man, cast by the light from the lantern that illuminated the corridor, pass along the wall, a man whom he had not heard approaching and whose body almost brushed against his. Sigognac turned his head quickly. It was the stranger from the kitchen, doubtless on his way to the lodgings that the host had assigned him. All quite normal. However, the Baron, feigning not to locate the keyhole at once, followed this mysterious personage, whose appearance strangely preoccupied him, with his eyes, until a bend in the corridor hid him from view. A door closing, with a noise that the silence descending on the inn made more perceptible, informed him that the stranger had located his room, and that he was lodged in a region of the inn quite distant from his own.

Not desirous of sleeping, Sigognac began to write a letter to the brave Pierre, which he had promised to do on his arrival in Paris. He took care to form the characters very distinctly, for the faithful servant was no great scholar and could hardly make out anything other than block letters. The epistle was worded thus:

‘My good Pierre, here I am at last in Paris, where, it is said, I shall make my fortune and re-establish my ruined House, though to tell the truth I hardly see the means. However, some fortunate opportunity may bring me closer to the Court, and if I succeed in speaking to the king, from whom all grace emanates, the services rendered by my ancestors to his predecessors will doubtless be taken into account. His Majesty will surely not allow a noble family that rendered itself destitute in the wars to become extinct in so miserable a manner. In the meantime, for lack of other resources, I am acting on the stage, and have, by this trade, earned a few pistoles, a share of which I will send you as soon as I have found a secure method. I would perhaps have done better to enlist as a soldier in some company, but I had no wish to constrain my freedom, and besides, however poor he may be, obeying orders is repugnant to someone whose ancestors issued them, and who has never accepted such from anyone. And then solitude has made me somewhat wild and untameable. The only notable adventure I have had during this long journey was a duel with a certain very unpleasant duke, though a fine swordsman, from which I emerged to my glory, thanks to your excellent teaching. My blade passed straight through his arm, and nothing would have been easier than to lay him dead on the field, since his skill in parrying scarcely matched his skill in lunging, he being more fiery than prudent, and less firm than nimble. Several times he left himself undefended, and I could have dispatched him with one of those inexorable strokes that you taught me with such patience during those long bouts we mounted in the basement room at Sigognac, the only one whose floor was solid enough for us to maintain our footing, so as to kill time, stretch our arms, and gain sleep through fatigue. Your pupil does you honour, and I have grown greatly in general esteem after this victory which in truth was all too easy. It seems that I am decidedly a fine blade, a first-rate swordsman. But let us leave that subject. I often think, despite the distractions of this new life, of the poor old castle whose ruins crumble above the tombs of my family, and where I spent my sad youth. From a distance, it no longer seems as ugly or gloomy to me; there are even moments when I wander, in thought, through those deserted rooms, gazing at the yellowed portraits which, for so long, were my only company, and causing a shard of glass fallen from a collapsed window to crackle underfoot; the reverie brings me a sort of melancholic pleasure. It would give me great joy, too, to see again your good old face, browned by the sun, light at the sight of me in a cordial smile. And, why should I blush to say it? I would like to hear the purring of Beelzebub, the barking of Miraut, and the neighing of that poor Bayard, who gathered his last strength to carry me along, though I was scarcely heavy. Those who are unfortunate, and whom men abandon, give a part of their soul to those creatures, more faithful than they, whom misfortune fails to scare away. Do those brave creatures who loved me still live, and do they seem to recall me, and miss me? Are you able, in that miserable dwelling, to at least prevent them from dying of hunger, by tossing them a few morsels from your own meagre fare? Try to stay alive all of you until I return, whether rich or poor, happy or desperate, to share my fortune or my desolation with you, and end together, as the fates decide, in the place where we have suffered together. If I must be the last of the Sigognacs, may God’s will be done! There is still an empty place for me in the ancestral vault.

Baron de Sigognac.’

The Baron sealed this letter with a ring, the only jewel he had inherited from his father, which bore the three storks on an azure field engraved upon it; he penned the address, and placed the letter in a wallet to be sent when some courier or other left for Gascony. From the castle of Sigognac, to which his thoughts of Pierre had transported him, his mind returned to Paris, and his present situation. Though the hour was late, he heard around him the dull, vague murmur of a great city which, like the ocean, is never silent even when it seems at rest. It was the hooves of a horse, the rumble of a carriage dying away in the distance, the song of a late drunkard, the clatter of rapiers against each other, the cry of a passer-by assailed by the thieves of the Pont-Neuf, the howl of a lost dog or some other indistinct noise. Among these sounds, Sigognac thought he could distinguish the footsteps of a booted man walking the corridor, cautiously, as if seeking not to be heard. He extinguished his candle, so the light would not give him away, and, half-opening his door, saw, in the depths of the corridor, an individual carefully wrapped in a dark-coloured cape, who was heading for the room of that unknown traveller whose appearance had seemed so suspicious. A few moments later, another companion, whose shoes creaked, though he tried to lighten his tread, took the same path as the first. Half an hour had not passed when a third fellow, possessed of a rather truculent air, appeared beneath the wavering light of the lantern, which was about to die, and entered the corridor. He was armed like the other two, a long sword lifting the border of his cloak behind. The shadow cast over his face by the rim of a felt hat with a black feather made it impossible to distinguish his features.

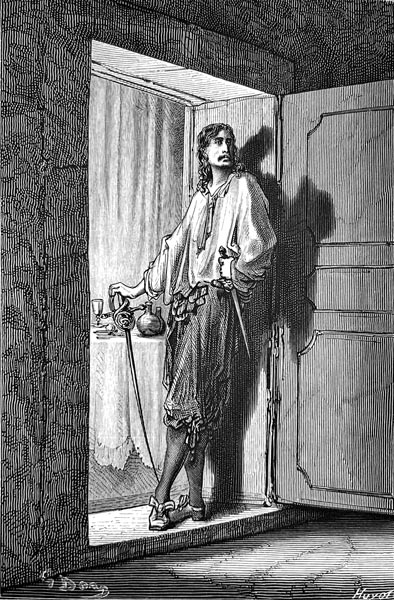

This procession of ruffians seemed strange and untimely to Sigognac, and the group of four recalled the ambush of which he had almost been the victim in the alley at Poitiers, on leaving the theatre after his quarrel with the Duke of Vallombreuse. His awareness was roused, and he recognised in the man who had intrigued him in the kitchen the scoundrel whose previous assault could have been fatal to him if he had not been expecting the like. It was indeed that same fellow with his hat sloped down to his shoulders, who had rolled about, legs and arms in the air, beneath the blows that Captain Fracasse had bravely administered to him with the flat of his sword. The others must have been his companions, valiantly routed by Herod and Scapin. What chance, or rather what plot, had brought them together at the inn where the troupe had taken up its quarters, and on the very evening of his arrival? They must have followed his journey step by step. Sigognac had watched the road diligently; but how is one to perceive an adversary in a cavalier who passes with an indifferent air, and pursuing his way, barely throws you the vague glance that any encounter excites when travelling? What was certain was that the hatred towards himself, and the love of the young duke for Isabella, were undimmed, and the duke was seeking to satisfy both. His vengeance was aimed at catching Isabella and Sigognac in the same net. Exceptionally brave by nature, the Baron felt no fear, on his own account, of these hired rascals’ mission, whom a waft of his good blade would put to flight, and who would prove no more courageous with the sword than the stick; but he feared some subtle and cowardly move against the young actress. He therefore took his precautions accordingly, and resolved not to rest. Lighting all the candles in his room, he opened his door so that a flood of light projected onto the opposite wall of the corridor, at the very point where Isabella’s door stood; then he seated himself quietly after drawing his sword and dagger, so as to be ready if anything untoward occurred. He waited for a long time without noting anything. Two o’clock had already struck on the carillon of La Samaritaine (the pumping station built 1602-8) and on the clock nearer the Grands-Augustins, when a slight rustling was heard, and soon, against the illuminated area of wall, appeared the first individual, uncertain, hesitant, and possessed of a very sheepish air, who was indeed none other than Mérindol, one of the Duke of Vallombreuse’s swordsmen. Sigognac stood at the threshold, sword in hand, ready for attack or defence, with a face so heroic, so proud and so triumphant, that Mérindol passed without saying a word, lowering his head.

‘Sigognac stood at the threshold…’

The other three, approaching in line, and surprised by the sudden flood of light, in the centre of which stood the Baron simmering quietly, slipped away as nimbly as they could, and the last one dropped a crowbar, no doubt intended to force open Captain Fracasse’s door while he slept. The Baron bid them farewell with a derisory gesture, and soon the noise of horses clattering from the stable could be heard in the courtyard. The four rogues, their attempt having failed, scampered off at full speed.

At breakfast, Herod addressed Sigognac. ‘Captain, does not curiosity compel you to go and tour this city, one of the principal ones in this world, and of which so many stories are told? If it is agreeable to you, I will serve as your guide and pilot, knowing from long experience, having navigated them in my adolescence, the reefs, shoals, shallows, Euripi (the Euripus Strait separates Euboea in the Aegean Sea from Boeotia in mainland Greece), Charybdises and Scyllae (Charybdis and Scylla were two sea-monsters, in Greek mythology, located on opposite sides of the Strait of Messina) of this sea, perilous to foreigners and provincials. I will be your Palinurus (Aeneas’ helmsman in Virgil’s ‘Aeneid’), but will not permit myself to fall head-first into the waves, like he of whom Virgil speaks. We are well placed to view the spectacle, the Pont-Neuf being to Paris what the Sacred Way (the Appian Way) was to Rome, the thoroughfare, meeting-place and peripatetic gallery of news-writers, innocents, poets, swindlers, thieves, entertainers, courtesans, gentlemen, bourgeoisie, soldiers, and people of all ranks.’

— ‘Your proposal pleases me greatly, brave Herod,’ replied Sigognac, ‘but warn Scapin that he is to remain at the hotel, and with his fox’s eye observe anyone who appears whose status is unclear. He must not leave Isabella undefended. Vallombreuse’s vengeance-seekers prowl around us, seeking to devour us. Last night I saw those four marauders again, whom we accommodated so fully in the alley at Poitiers. Their plan was, I imagine, to force my door, surprise me in my sleep, and do me an ill deed. As I was awake in fear of an abduction of our young friend, their plan failed, and, finding themselves discovered, they fled in haste, their horses having been fully saddled in the stable under the pretext that they wished to leave early in the morning.’

— ‘I doubt,’ replied the Tyrant, ‘that they will dare attempt anything by day. Help would arrive at the slightest call, and they will still be reeling from their disappointment. Scapin, Blazius and Leander will be enough of a force to guard Isabella till we return. But for fear of some quarrel or altercation in the streets, I will bear my sword in support of yours if necessary.’

Having said this, the Tyrant buckled a belt, supporting a long and solid rapier, about his ample belly. He threw over the corner of his shoulder a short cape that would not hinder his movements, and he sloped his red-feathered felt hat over his eyebrows; for one must beware, when crossing bridges, of the north-west wind or galerne, which soon blows a hat into the river, to the great delight of pages, footmen, and urchins. Such was the reason given by Herod for his defensive head-dress, though, in truth, it was because the honest actor thought it might perhaps do harm thereafter to Sigognac the gentleman to have been seen in public with a histrion. That is why he hid his face as much as possible which he deemed too well known to the people.

At the corner of Rue Dauphine, Herod pointed out to Sigognac, beneath the porch of the Convent of the Grands-Augustins, those folk who hastened to buy meat seized from the butchers on proscribed days, and so obtain a cut at a lower price. He also showed him the newsmen, discussing, among themselves, the destinies of kingdoms, rearranging borders at will, dividing empires, and reporting item by item the speeches the ministers had made when alone in their offices. There were gazettes, libels, satirical writings, and other small pamphlets being peddled from beneath various cloaks. All these odd people possessed haggard faces, a wild air, and worn clothing.

— ‘Let us not wait,’ said Herod, ‘to listen to their never-ending nonsense; unless, however, you wish to know the latest edict of the Persian Sophy, or the ceremonial employed at the court of Prester John. Let us advance a few steps and enjoy one of the most beautiful spectacles in the universe, one the theatre cannot present by means of its scenic effects.’

Indeed, the perspective which unfolded before the eyes of Sigognac and his guide, as they crossed the bridge thrown over the river, had not then, and still has, no rival in the world. The foreground was formed by the bridge itself with its graceful half-moon bastions set above the piers. The Pont-Neuf was not burdened, like the Pont au Change and the Pont Saint-Michel, with two rows of tall houses. The great monarch who completed it (Henri IV, in 1606) had not wanted feeble and gloomy buildings to obstruct the view of the sumptuous palace (the Tuileries Palace, destroyed by fire, in 1871, during the Commune) in which our kings reside, and which can be seen from this point in all its glory.

On the platform forming the tip of the island, the good king, with the calm air of a Marcus Aurelius, rode his bronze mount atop a pedestal on which at each corner leaned a bronze captive, twisting in his bonds (The extant equestrian statue was unveiled in 1613, the captives in 1618, later destroyed in 1792). A wrought iron grille, with rich volutes surrounded it, to protect its base from the undue familiarity and irreverence of the people; since, on occasion, after clambering over the grille, various rascals ventured to mount behind the debonair monarch, especially on days of royal entry to the city, or interesting executions. The severe tone of the bronze stood out strongly against the misty air, and the backcloth of distant hills that could be seen beyond the Pont Rouge (Built around 1632, and located near the present-day Pont Royal, it linked the St-Germain quarter to the Tuileries. It was washed away in 1684.)

On the left bank, above the houses, rose the spire of the old Romanesque church, Saint-Germain des Prés, and the high roofs of the Hôtel de Nevers, a grand palace still unfinished (not extant, later the Hôtel de Guénégaud then the Hôtel de Conti, it was located on the Quai de Nevers, now the Quai de Conti, on the site of the present day Hôtel des Monnaies, the Mint). A little further on, the tower (the Tour de Nesle), an ancient remnant of the Hôtel de Nesle, dipped its feet in the river, amidst a heap of rubble, and though long since in a state of ruin, still maintained a proud attitude against the horizon. Beyond, stretched La Grenouillère, and amidst a vague azure mist one could distinguish at the edge of the sky the three crosses planted at the top of the hill of Calvary, Mont Valérien (Suresnes).

The Louvre, in all its splendour, occupied the right bank, illuminated and gilded by a cheerful shaft of sunlight, more luminous than warm, like a winter sun, but which gave a singular relief to the details of its architecture, both noble and rich. The long gallery joining the Louvre to the Tuileries, a marvellous arrangement allowing the king to be, whenever he pleased, either in his good city or in the countryside, displayed its nonpareil beauties, fine sculptures, historiated cornices, vermiculated bossages, columns and pilasters equalling the efforts of the most skilful Greek and Roman architects.

From the corner where the balcony of Charles IX stands, the building in its retreat, gave way to gardens and parasitic constructions, mushrooms sprouting at the foot of the old edifice. On the quay, culverts rounded their arches, and a little further downstream than the Tour de Nesle stood a courtyard, the remains of the old Louvre of Charles V, flanking the gatehouse (the Tour de Bois) built between the river and the palace. These two old towers, coupled in the Gothic fashion, facing each other diagonally, contributed not a little to the pleasantness of the perspective. They recalled the time of feudalism, and held their place amidst the new and more tasteful architecture, like an antique pulpit or a curiously crafted old oak dresser amidst modern furniture plated with silver and gilding. These relics of vanished centuries grant cities a respectable appearance, and we should take care they are not allowed to disappear.

At the far end of the Tuileries Gardens, where the city terminated, one could see the Porte de la Conférence (not extant, it stood on the right bank, part of Louis XIII’s wall), and along the river, beyond the gardens, the trees of the Cours-la-Reine, a favourite promenade of courtesans and people of quality, who frequented it to display their carriages.

The two banks, of which I have just drawn a quick sketch, framed like two wings the animated scene presented by the river furrowed by boats crossing from shore to shore, obstructed by others moored together near the bank, some loaded with hay, some with wood or other goods. Near the quay, at the foot of the Louvre, the royal galliots (galleys) attracted the eye with their sculpted and gilded ornaments, and their flags in the colours of France.

Looking back towards the bridge, one could see above the sharp peaks of the houses, like cards leaning against one another, the steeples of Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois. Having sufficiently contemplated this view, Herod led Sigognac to La Samaritaine (the hydraulic pump, established downstream of the second arch of the Pont-Neuf, on the right bank, began operation in 1608. The facade, topped by a campanile, was decorated with a high relief representing Christ and the Samaritan woman at the well, and the building was swiftly named ‘La Samaritaine’)

— ‘Even though it is a meeting place for simpletons who stand there for long periods of time waiting for the brass bell-ringer to strike the hour on the clock, one must go there, and do as the others do. A little idleness does not go amiss as regards a newly arrived traveller. It would be more boorish than wise to despise and rebuff, in an over-scrupulous manner, that which charms the people.’

It was in these terms that the Tyrant excused himself to his companion as they stood at the foot of the facade of the little building which housed the hydraulic pump, waiting for the clock’s hand to set the joyous chime in motion, and gazing at the gilded-lead Jesus speaking to the Samaritan woman leaning on the edge of the well; the astronomical dial with its zodiac and its ebony discs marking the course of the sun and the moon; the masked face emitting the water drawn from the river; the sheathed Hercules supporting the whole mass of decoration; and the hollow statue serving as a weather-vane like that of Fortune on the Dogana in Venice, or the Giraldillo on the Giralda bell-tower in Seville.

The tip of the hour-hand finally reaching the number ten, the bells began to ring most joyously, their thin, silvery or brassy tones playing a sarabande; the bell-ringer raised his brazen arm, and the hammer descended on the bell as many times as there were hours to strike. This mechanism, ingeniously devised by the Fleming, Jean Lintlaër, greatly amused Sigognac, who, though naturally intelligent, was experiencing much that he did not know, having never left his manor house amidst the moors.

— ‘Now,’ said Herod, ‘let us turn in the other direction; upstream, the view is not quite so magnificent. The houses on the Pont au Change obstruct it too much. The buildings on the Quai de la Mégisserie (which stretches from the Pont au Change to the Pont Neuf) are worthless; however, the Saint-Jacques tower, the Saint-Méderic (the church of Saint Merri, on Rue Saint Martin) bell-tower, and those distant church spires clearly proclaim the great city. Meanwhile, on l’Île du Palais, (l’Île de la Cité) along the quay beside the river, those regular red-brick houses, linked by bonds of white stone, have a monumental appearance which is happily completed by the old Clock Tower (the Tour de l’Horlogue) topped with its candle-snuffer roof, which often pierces the mist alone. The Place Dauphine, its triangle extending beyond the bronze statue of Henri IV, and allowing a view of the Palace gates, can be ranked among the most orderly and cleanest. See how the spire of the Sainte-Chapelle, that church on two levels, so famous for its treasure and its relics, dominates the high slate roofs nearby most gracefully, pierced as they are with ornamented dormer vents, and which still shine with a brand new splendour, for these houses were not built long ago, and in my childhood I played hopscotch on the land they occupy; thanks to the munificence of our kings, Paris is becoming more beautiful every day, and is greatly admired by foreigners, who, upon returning to their own countries, tell of her wonders, while finding her improved, enlarged and well-nigh new on every visit.’

— ‘What astonishes me,’ replied Sigognac, ‘even more than the grandeur, wealth, and sumptuousness of the buildings, both public and private, is the streets, squares, and bridges amidst which an infinite number of people swarm and teem, like ants whose anthill has been overturned, and who race about wildly, here and there, in a manner whose purpose one cannot suspect. It is strange to think that among the individuals who make up this inexhaustible multitude, each has a room, a bed good or bad, and eats almost every day, without which they would die of starvation. What a prodigious pile of provisions, how many herds of oxen, barrels of flour and of wine are needed to feed all these people piled up in the one place, while on our moors one scarcely meets a single inhabitant, now and then!’

Indeed, the crowd of people circulating on the Pont-Neuf was more than large enough to surprise a provincial. In the middle of the roadway, carriages with two or four horses followed or passed each other, some freshly painted and gilded, upholstered in velvet with mirrors in the doors, and gently swaying on their springs, attended by footmen at the rear, and driven by coachmen with crimson faces, in full livery, who could barely restrain, amidst the crowd, the impatience of their teams; others less brilliant, with tarnished paint, leather curtains, and taut springs, were drawn by far more docile horses whose ardour had to be roused by the whip, and who announced the lesser wealth of their masters. In the former, behind the windows, one could see magnificently dressed courtiers, and coquettishly attired ladies; in the latter, those of lesser means, doctors and other serious-looking people. Amidst all this, carts passed, loaded with stone, wood or barrels, and driven by brutal carters whose difficulties in doing so led them to deny their God with frenzied energy. Our cavaliers tried to force a passage through this moving maze of wagons, unable to avoid on occasion finding their boots scraped and muddied by a wheel-hub. Sedan chairs, some owned by their masters, others hired, attempted to keep to the edges of the current, so as not to be swept away by it, skirting the parapets of the bridge as much as possible. A herd of oxen chanced to pass, and the disorder was then at its height. The horned beasts, and by that I do not mean any married bipeds who were then crossing the Pont-Neuf, but rather the oxen, swung to and fro, lowering their heads, frightened, harassed by the dogs, and beaten by the drivers. At the sight of them the horses, also fearful, stampeded or reared. Passers-by ran for their lives, for fear of being gored, while the dogs, slipping between the legs of those less agile, upset their centre of gravity, and caused them to fall flat as pancakes. A lady, painted and speckled with beauty-spots, and trimmed with jet and flame-coloured ribbons, who looked like a priestess of Venus in search of adventure, even stumbled from her high-arched pattens and fell flat on her back, without hurting herself, ‘as if accustomed to such falls’, the jokers who gave her a hand to help her up, did not fail to say. At another time, a company of soldiers on its way to some post, standards unfurled and drummer at the head, passed by, and it was necessary that the crowd make way for these Sons of Mars unaccustomed to encountering any resistance.

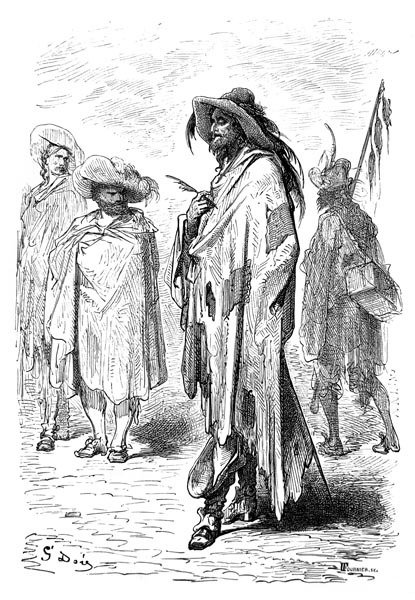

— ‘All this,’ said Herod to Sigognac, who was absorbed by the spectacle, ‘is merely commonplace. Let us try to pierce the crowd, and attain those places where the eccentrics of the Pont-Neuf are to be found, extravagant, entertaining figures whom it is good to examine more closely. No other city but Paris produces such heterogeneous ones. They flourish amidst its paving stones like weeds, or rather, like deformed and monstrous fungi for which no soil is as well suited as this black mud. Ah! Look, here, as I speak, comes the Périgourdin, Du Maillet, called ‘the muddy poet’, who is paying court to the bronze king on his horse. Some claim he is an ape escaped from some menagerie; others that he is one of the camels brought back by Monsieur de Nevers (Charles I Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua and Montferrat, who was also titled Charles III, Duke of Nevers, had laid claim to the throne of Constantinople. He died in 1637). The problem has not yet been resolved: I consider him to be human, given his madness, arrogance, and uncleanliness. Monkeys groom themselves, seek out the insects amidst their fur, and eat them, out of revenge and retaliation; he takes no such care of himself; camels cleanse and sprinkle themselves with dust as if it were iris powder; they have several stomachs and chew their food; which this fellow cannot do, for his crop is always as empty as his head. Toss him a coin; he will take it, grumbling and cursing you. He is therefore a man indeed, since he is mad, dirty and ungrateful.’

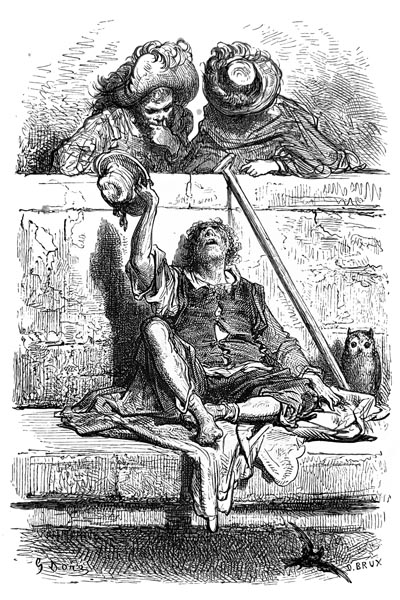

‘Ah! Look, here, as I speak, comes the Périgourdin, Du Maillet.’

Sigognac took a silver coin from his purse and proffered it to the poet, who, lost in a deep reverie, as these folk of feeble brains, and fantastical moods commonly are, failed at first to see the Baron standing before him. He finally did so and, emerging from his empty meditation, took the coin with a wild and abrupt gesture and plunged it into his pocket, muttering a few vague insults, then, the demon of verse taking hold of him again, he began to grind his lips, roll his eyes, and grimace in at least as curious a manner as those grotesque masks (replaced by copies and dispersed) sculpted by Germain Pilon (1525-1590) beneath the cornice of the Pont-Neuf, accompanying the whole with movements of the fingers to mark the feet of the verse he was murmuring between his teeth, which made him look like a man playing Morra (a finger game) and delighted the rascals gathered in a circle around him.

This poet, it must be said, was more singularly attired than the Mardi Gras effigy, when it is taken to be burned on Ash Wednesday, or one of those mannequins raised in orchards or vineyards to frighten away greedy birds. One would have said, on seeing him, that the bell-ringer of the Samaritaine, the little Moor of the Marché-Neuf (a former market on the Île de la Cité) and the Jacquemart of Saint-Paul (in the Marais) had visited a second-hand shop and left their clothes there to provide his garb. An old felt hat, scorched by the sun, washed by the rain, girded with a greasy cord, topped, by way of a plume with a moth-eaten cockerel’s feather, and more comparable to an apothecary’s filtering-bag than a piece of human head-gear, hung down over his eyebrows, forcing him to raise his head to see, for his eyes were almost hidden under its flabby and filthy rim. His doublet, of an indescribable fabric and colour seemed in a better mood than himself, since the comical garment was gaping openly, at every seam, and appeared bursting with laughter, and due to old age too, having doubtless existed for more years than Methuselah. A strip of frieze cloth served as his belt and baldric and supported, as a sword, a fencing foil shorn of its button whose point dug, like a ploughshare, into the pavement behind him. Breeches made of the yellow satin which had once adorned the masked dancers in some ballet scene, were swallowed by boots, one an oyster fisherman’s, of black leather, the other of white Russian leather with a knee-pad, this latter with a flat sole, the other, which was equipped with a spur, an arched and peeling sole which would have long since departed its boot without the help of a piece of string twisted several around the foot like the bands of an antique buskin. A red goat-skin coat, which every season found at its post, completed his attire, which would have shamed an apple-picker from Perche, and of which our poet seemed not a little proud. Beneath the folds of the coat, next to the pommel of the sword doubtless charged with protecting him, a stick of bread showed its nose.

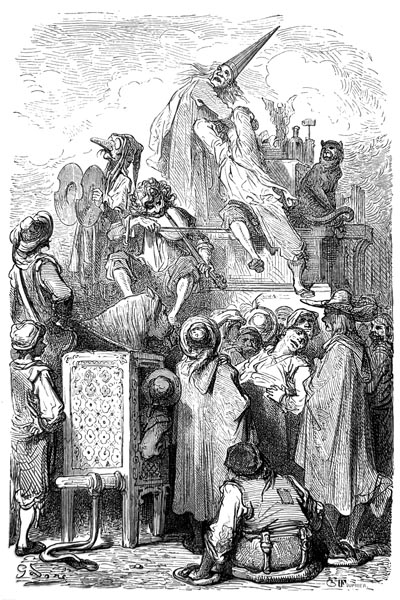

Further on, in one of the bastions set above each pier, stood a blind man, accompanied by a fat female companion who served as his eyes, and bawled out boisterous couplets or, in a comically lugubrious tone, intoned a lament on the life, crimes and death of some famous criminal. In another place, a charlatan, dressed in a red serge costume, was struggling, with a pair of pliers for extracting teeth in his hand, on a platform adorned with garlands of canine, incisor, and molar teeth threaded on brass wires. He delivered a speech to the gathered onlookers in which he undertook to remove without any pain (to himself) the most stubborn and deeply-rooted stumps, with a stroke of a sabre or a pistol, at the patient’s discretion, unless, however, they preferred to be operated on by ordinary means. ‘I don’t pull them...’ he cried, in a screeching voice, ‘I pluck them! Come now, let any of you who has bad teeth enter the circle without fear, and I will cure him instantly!’

‘…I will cure him instantly!’

A sort of boor, whose swollen cheek showed that he was suffering from an abscess, came and seated himself on the chair, and the operator plunged his formidable pair of polished-steel pliers into his mouth. The unfortunate man, instead of holding onto the arms of the chair, followed the trajectory of his tooth, which was separated from him with great difficulty, raising himself more than two feet in the air, which greatly amused the crowd. A sudden jerk ended his torment, and the operator brandished his bloody trophy above their heads!

During this grotesque scene, a monkey attached to the platform by a chain riveted to a leather belt which encircled his kidneys, imitated, comically, the patient’s cries, gestures and contortions.

This ridiculous spectacle did not detain Herod and Sigognac for long, who were more inclined to stop before the sellers of newspapers (Theophraste Renaudot, a Protestant physician and protégé of Cardinal Richelieu, founded the first weekly newspaper in France, La Gazette, in 1631), and second-hand books, installed on the parapets. The Tyrant pointed out to his companion a ragged beggar who had settled himself before the bridge, against the solid cornice, his crutch and bowl beside him, and who from there, raising his arm, thrust his filthy hat beneath the noses of those bending over to leaf through a book, or watch the flow of the river, so that, if they chose, they could throw into it a copper or two, or even a silver tester, or more still if they wished, for he refused nothing, being quite capable of passing off a counterfeit coin.

— ‘In our country,’ said Sigognac, ‘only swallows haunt the ledges; here it’s men!’

— ‘You call this fellow a man!’ said Herod. ‘That’s most polite, though as Christians, we should not despise any. Besides, all kinds of people cross this bridge, perhaps even honest ones, since we ourselves are here. According to the proverb, one cannot cross it without meeting a monk, a white horse, and a whore. Here is a friar hurrying along, his sandals clicking; the white horse is not far off; there, look, in front of you, by God; that nag, who is curveting as if between the training-posts. All that’s missing is the whore. We won’t have long to wait. Instead of one, here come three, bare-throated, painted like carriage-wheels, and laughing affectedly to show their teeth. The proverb proves true.’

‘You call this fellow a man!’ said Herod.’

Suddenly a tumult was heard at the far end of the bridge, and the crowd ran towards the noise. Four swordsmen were fencing on the platform at the foot of the statue, as the freest and most open place. They shouted: ‘Death! Death! and pretended to charge furiously. But theirs were only simulated thrusts, restrained and courteous thrusts as in comedy duels, from which, whether killed or wounded, no one ever dies. They fought two against two, and seemed animated by extreme rage, pushing aside the swords which their companions interposed in attempts to separate them. This feigned quarrel was intended to drum up a gathering so that the thieves and cut-purses could carry out their trade, amidst the crowd, with complete ease. Indeed, more than one curious person who had entered the group with a fine coat lined with panne (fabric worked like velvet) over his shoulder, and a well-lined pocket, left the place in a plain doublet, having spent his money without knowing it. The swordsmen, who had never quarrelled at all, being as thick as thieves, which indeed they were, at a fair, soon reconciled, and shook hands with great affectations of loyalty, declaring honour satisfied. Which was not difficult; the honour of such scoundrels lacking any great points of delicacy.

Sigognac, on Herod’s advice, had not approached the combatants too closely, so could only see them vaguely through the gaps left by the heads and shoulders of the onlookers. However, he thought he recognised in these four rogues the men whose mysterious movements he had observed the previous night at the inn on Rue Dauphine, and he communicated his suspicion to Herod. But the swordsmen had already slipped away, prudently, in the crowd, and were now harder to find than a needle in a haystack.

— ‘It’s conceivable,’ said Herod, ‘that their quarrel was only a ruse to draw you to them, for it may well be that we are being followed by emissaries of the Duke of Vallombreuse. One of the swordsmen would have pretended to be embarrassed or shocked by your presence, and, without giving you time to draw his sword, he would have struck you some murderous blow, seemingly inadvertently, and, if necessary, his comrades would have finished you off. The whole thing would have been attributed to a chance encounter and a brawl. In such altercations, the one who receives the blows retains them. Premeditation and a subsequent ambush cannot be proven.’

— ‘I find it hard to believe,’ replied the generous Sigognac, ‘that a gentleman could be capable of such baseness as to have his rival assassinated by swordsmen. If he was not satisfied by our first encounter, I am ready to cross swords with him again, until the death of one or the other of us ensues. That is how things are done between men of honour.’

— ‘Doubtless,’ replied Herod, ‘but the duke well knows, however enraged and proud he may be, that the outcome of the fight could not fail to be fatal to him. He has tasted your blade, and felt its point. Believe me, he holds a diabolical grudge following his defeat, and will not be delicate about the means of taking revenge.’

— ‘If he disdains the sword, let us fight on horseback with pistols,’ said Sigognac. ‘He’ll be unable then to employ my strength in fencing as an excuse.’

While talking in this manner, the two companions reached the Quai de l’École (the name is not extant, it ran from the Pont-Neuf to the Place du Louvre), and there a carriage almost crushed Sigognac, even though he moved aside promptly. His slim build prevented him from being flattened against the wall, so close was the carriage to him, though there was plenty of room on the other side and the coachman, by directing his horses a little that way, could have avoided this passer-by whom he seemed to be assailing. The windows of this carriage were raised, and the interior curtains drawn; but whoever had pulled them aside would have revealed a magnificently dressed nobleman, his arm supported by a wide strip of black taffeta arranged as a sash. Despite the light within, reddened by passing through the closed curtains, he himself was pale, and the thin arches of his black eyebrows were prominent against the matt white of his face. His teeth, purer than pearls, had bitten his lower lip until it bled, and his thin moustache, stiffened with wax, bristled with feverish contractions, like that of a tiger scenting its prey. He was quite handsome, but his physiognomy displayed such a cruel expression that it was more likely to inspire fear than admiration, at least at that moment, when evil and hateful passions distorted it. In this portrait, sketched while lifting the curtain of the carriage passing at full speed, the reader has undoubtedly recognised the young Duke of Vallombreuse.

— ‘Another failure,’ he cried, as the carriage carried him along the Tuileries towards the Porte de la Conférence. ‘I promised my coachman twenty-five louis if he was clever enough to trap that damned Sigognac and crush him against a post as if by accident. My star is definitely fading; this little country squire is getting the better of me. Isabella adores him, and hates me. He has beaten my men; he has wounded me. Though he seems invulnerable as if protected by some amulet, he must die, or I shall forego my name, and my title of duke.’

— ‘Hmm!’ said Herod, drawing a deep breath from his chest, ‘the horses drawing that carriage seem to have the same temper as Diomedes’ horses (in Greek myth), which hunted men, tore them to pieces, and fed on their flesh. You are not hurt, at least? That unfortunate coachman saw you quite plainly, and I’d wager our best takings that he was seeking to kill you, deliberately setting his team against you, as part of some private design of revenge. I’m certain of it. Did you notice if there was a coat of arms painted on the door? As a gentleman, you are familiar with the noble science of heraldry, and the coats of arms of the principal families are familiar to you.’

— ‘I couldn’t say,’ replied Sigognac. ‘Even a herald at arms, in that situation, would have failed to discern the enamels and colours of a shield, much less its field and divisions, its emblems and devices. I had far too much to do, in avoiding the wheels, to see if it was decorated with guardant or issuant lions, birds or martlets, gold bezants or plain roundels, crosses clechées or vivrées, or any other designs.’

— ‘That is unfortunate,’ replied Herod, ‘such an observation would have set us on the right trail, and helped us perhaps to discover the thread of this dark intrigue; for it is evident that someone is trying to rid themselves of you, quibuscumque viis (by one means or another), as the Pedant, Blazius, would say in his Latin. Though proof is lacking, I should not be at all surprised if this carriage belonged to the Duke of Vallombreuse, who wished to give himself the pleasure of driving his chariot over the body of his enemy.’

— ‘What mean you by that, Master Herod?’ cried Sigognac. ‘That would be a base, infamous, and villainous action, all too unworthy of a gentleman of a great house, such as this Vallombreuse is, after all. Besides, did we not leave him in his hotel at Poitiers, rather unwell from his wound? How could he already be in Paris, when we only arrived yesterday?’

— ‘Did we not stop at Orléans and Tours, where we gave performances, a period long enough for him to have been able, with the carriages at his disposal, to follow us, and even arrive in advance of us? As for his wound, treated by the most excellent doctors, it will have closed and healed quickly. It was not, moreover, of a nature dangerous enough to prevent a young and vigorous man from travelling at his ease in a carriage or litter. You must therefore, my dear Captain, be on your guard, because they are plotting some kind of blow, à la Jarnac, against you, or to ambush and slay you, disguising it as some kind of accident. Your death would leave Isabella defenceless in the face of the duke’s schemes. Can we, poor actors, stand up to such a powerful lord? If it is questionable whether Vallombreuse can be in Paris as yet, his emissaries, at least, are acting in his stead here, since this night past, if you had not kept watch, while armed, roused by a valid suspicion, they would have cheerfully slit your throat in your room.’

The reasons given by Herod were too plausible to be questioned further; therefore, the Baron merely replied with a sign of assent, and placed his hand on the hilt of his sword, which he half-drew, in order to make sure that it moved smoothly, as regards the scabbard.

While talking, the two companions had passed beyond the Louvre and the Tuileries, and had reached the Porte de la Conférence, which led to the Cours-la-Reine, when they saw before them a great whirlwind of dust amidst which weapons glinted, and cuirasses gleamed. They stood aside to let the cavalry squadron go by, which preceded the king’s carriage, returning from Saint-Germain to the Louvre. They could see within, since the windows were lowered and the curtains drawn back, doubtless so that the people could contemplate to their heart’s content their monarch and the arbiter of their destinies, a pale phantom, dressed in black, with a blue ribbon on his chest, as motionless as a wax effigy. Long brown hair framed that lifeless face, its saddened expression one of incurable ennui, a Spanish boredom, à la Philip II, such as only the Escorial could concoct in its silence and solitude. It seemed as if the eyes reflected nothing; no desire, no thought, no expression of will appearing to enliven them. A profound disgust with life had slackened the lower lip, which drooped morosely in a sort of sulky pout. A pair of thin, white hands rested on the knees, in the manner of certain Egyptian statues. However, there was still a royal aura surrounding this gloomy figure which personified France, and in which the generous blood of Henry IV had congealed.

The carriage passed in a flare of light, followed by a large body of horsemen bringing up the rear. Sigognac was plunged in reverie on seeing this apparition. In his naivety, he had pictured the king as a supernatural being, radiant and powerful, shining amidst a sun formed of gold and precious stones, proud, splendid, triumphant, greater, stronger, and more beautiful, than all; and yet he had seen nothing more than a sad, puny, bored, sickly figure, poor in appearance, in a dark costume like a suit of mourning, who seemed not to notice the outside world, occupied as he was by some gloomy thought. ‘What!’ he said to himself. ‘Here is the king himself, the person in whom so many millions of men are summed up, who sits atop the pyramid, and towards whom so many hands stretch out from below, in supplication; who silences the cannons or makes them roar, elevates or demotes, punishes or rewards, pardoning, if he so wishes, when justice proclaims the death sentence; he who can change a destiny with a word! If his gaze fell upon me, I would soar from poverty to riches, from weakness to power; previously unknown, I would thereafter flourish, hailed and flattered by all. The ruined turrets of Sigognac would rise proudly once more; estates would be added to my diminished patrimony. I would be the lord of hill and plain! Yet how could he ever come to know of me, buried in this human anthill teeming distantly at his feet, and which he neglects to view? And even if he did see me, what sympathy could there be between us?’

These reflections, and many others that would take too long to recount, occupied Sigognac, as he walked, in silence, beside his companion. Herod respected his reverie, amusing himself by watching the carriages come and go. Eventually, he pointed out to the Baron that it was nearly noon, and that it was time to follow the compass needle that pointed towards the culinary pole, nothing being worse than a cold dinner except a re-heated one.

Sigognac yielded to this peremptory reasoning, and they returned to their inn. Nothing unusual had occurred in their absence. Only two hours had passed. Isabella, seated quietly at the table in front of a bowl of soup, its contents starred with more eyes than Argus’ body, welcomed her friend with her customary sweet smile and extended her white hand. The actors asked him playful questions, or expressed their curiosity, about his excursion through the city, asking if he still had with him his coat, handkerchief, and purse. To which Sigognac cheerfully replied in the affirmative. This amiable chatter soon made him forget his gloomy preoccupation, and he wondered whether he was not merely the dupe of an obsessive imagination that foresaw danger everywhere.

His instinct was correct, however, and his enemies, despite their aborted attempts, had not renounced their shadowy plans. Mérindol, threatened by the duke with a return to the galleys from which he had rescued him, if he did not overcome Sigognac, decided to request the help of a brave friend of his, to whom no enterprise was repugnant, however hazardous it might be, as long as it was well paid. He did not feel strong enough himself to defeat the Baron, who, moreover would recognise him, which rendered an attack on him difficult to achieve, since he was now on his guard.

Mérindol therefore went in search of this swordsman who dwelt in the Place du Marché-Neuf, near the Petit-Pont (rebuilt many times, the current bridge dates from 1852), an area populated mainly by swordsmen, rogues, thieves, and other folk of ill repute.

Noticing among the tall black houses, which leant on one another like drunkards afraid of falling, one blacker, more dilapidated, more leprous than the others, whose windows, overflowing with filthy rags, resembled slashed bellies leaking their entrails, he entered the dark alley which served as the entrance to this cavern. Soon the daylight from the street was lost, and Mérindol, feeling the wall, as sweaty and slimy as if snails had glued themselves to it and left their trails behind, sought in the shadows the rope that served as a banister for the staircase, a rope which one might have thought had been detached from the gallows, coated as it was with human grease. He hoisted himself up this miller’s ladder as best he could, stumbling at every step over the bumps and callouses formed on each step by the ancient mud piled there, layer on layer, since the days when Paris was called Lutetia (the Gallo-Roman town of the Parisii, which preceded the later city).

However, as Mérindol advanced in his perilous ascent, the darkness became less intense. A pale light filtered through the opaque yellow panes of the fixed windows intended to light the staircase, and which looked out onto a courtyard as dark and deep as a mineshaft. Finally, he arrived at the top floor, half suffocated by the mephitic vapours exhaled by the leading. A trio of doors opened onto the landing whose dirty plaster ceiling was embellished with obscene arabesques, curlicues, and more-than-Rabelaisian flourishes traced by the candle-smoke; frescoes well worthy of such a hovel.

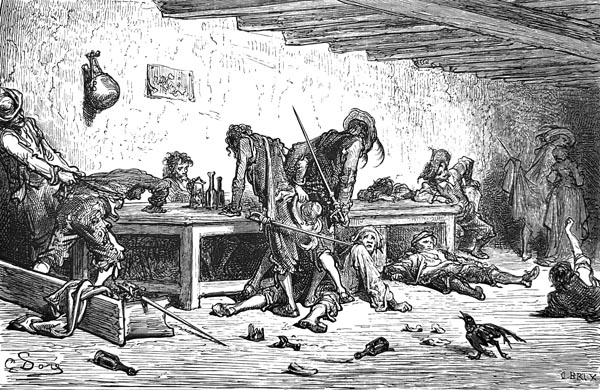

One of these doors was ajar. Mérindol pushed it open with a kick, not wanting to touch it with his hand, and entered, without further ceremony, the only room constituting the palace of the swordsman Jacquemin Lampourde.

Acrid smoke so stung his eyes and throat that he began to cough like a cat that had swallowed a feather while devouring a bird, and it was a good two minutes before he could speak. Taking advantage of the open door, the smoke spread onto the landing, and the fog becoming less thick, the visitor was able to discern, more or less, the interior of the room.

This den deserves special description, because it is doubtful whether the honest reader has ever set foot in such a hovel, and therefore may be unable to imagine its destitute state.

The place consisted of four walls on which infiltrations from the roof had drawn islands and rivers unknown to any geographical map. In places within reach, the successive tenants of the hovel had amused themselves by engraving with a knife their names, incongruous, baroque, or hideous, following that urge which drives the most obscure to leave a trace of their passage through this world. To these names was often attached a woman’s name, Iris of the Crossroads, surmounted by a heart pierced by an arrow like a fishbone. Others, more artistic, had attempted, with a piece of coal removed from the ashes, to sketch some grotesque profile, a pipe between its teeth, or a hanged man with protruding tongue frolicking on the arm of the gallows.

On the edge of the chimney, where pieces of a stolen bundle of wood were smoking and spurting, a world of bizarre objects was piled in the dust: a bottle with a half-consumed candle, the tallow of which had run in wide sheets over the glass, stuck in its neck, a true torch of the prodigal son and the drunkard; a trictrac cup (trictrac is a points-scoring game with similarities to backgammon), three lead-dice (often made from spent musket balls), Robert Beinières’ manual for players at lansquenet (the card game), a bundle of old pipe-ends, a stoneware pot for tobacco, a slipper containing a toothless comb, a dark lantern its lens as round as the pupil of a nocturnal bird, bundles of keys, doubtless false for there were no drawers in the room to lock or unlock, a moustache-curler, a corner of a mirror, its silver plate scratched as if by the claws of the Devil, in which only one eye at a time was visible, if slenderer that is than those of Juno, whom Homer calls Βοῶπις (cow-eyed), and a thousand other trinkets tedious to describe.

Opposite the fireplace, on a section of wall less damp than the rest, and covered with a hanging of green serge, shone a bundle of carefully polished swords, tempered, tested, and bearing on their steel the marks of the most famous armourers of Spain and Italy. There were double-edged blades, triangular blades, blades hollowed in the middle to allow the blood to drain; daggers with large basket-hilts, cutlasses, daggers, stilettos and other expensive weapons whose richness made a singular contrast with the dilapidation of the den. Not a speck of rust, not a speck of dust soiled them; they were the tools of the killer, and could not have been better maintained in a princely arsenal, rubbed with oil as they were, sponged with wool, and preserved in their original state. One would have said they came fresh from the forge. In them Lampourde, so careless about everything else, invested his self-esteem and they were his absorbing interest. This professionalism, when one thought of the trade he practiced, took on a dreadful character, and over those well-polished pierces of metal a reddish play of the light seemed to flicker.

There were no seats in the room, and one was free to stand upright, unless one preferred to employ, so as to spare the soles of one’s shoes, an old battered basket, a trunk, or the lute-case lying in a corner.

The table consisted of a shutter placed on two trestles. It also served as a bed. After having caroused, the master of the house would lie down on it, and, taking the corner of the tablecloth, which was none other than the tail of his coat, the upper portion of which he had sold to line his stomach, he would turn towards the wall so as to avoid seeing the empty bottles, a singularly melancholic spectacle for a drunkard.

It was in this position that Mérindol found our Jacquemin Lampourde, who was snoring like an organ-pipe, though all the clocks in the vicinity had struck four in the afternoon.

An enormous venison pie, which showed in its vermilion ruins the marks of pistachios, and was more than half-devoured, lay disembowelled on the floor, like a corpse left behind by wolves in the depths of a wood, surrounded by a fabulous number of flasks from which the soul had been extracted, and which were now nothing more than the ghosts of bottles, hollow apparitions good only for broken glass.

A companion, whom Mérindol had not at first seen, was sleeping, fists outstretched, beneath the table, still holding in his teeth the broken stem of a pipe, the bowl of which stuffed with tobacco had fallen to the ground, and which, in his drunkenness, he had forgotten to light.

— ‘Hey there, Lampourde!’ cried Vallombreuse’s officer, ‘enough of this sleeping; don’t look at me with those eyes, rounder than marbles. I’m no commissioner or agent come to fetch you to the Châtelet (The Grand Châtelet was a fortress on the right bank of the Seine, on the site of the current Place du Châtelet; with a court and police headquarters, and a number of prisons.) The matter is important: try to rescue your reason sunk to the bottom of the glass, and pay attention.’

The person thus summoned rose, with the slowness of the newly awakened, sat up, stretched out his long arms, the fists of which almost touched the two walls of the room, opened an immense mouth toothed with sharp fangs, and, clicking his jaws, gave a formidable yawn, like that of a bored lion, accompanied by inarticulate, guttural clucking noises.

Jacquemin Lampourde was no Adonis, though he claimed to be favoured by women as greatly as many another, and even, according to him, by the noblest and best-placed. His great height, of which he took pride, his thin, heron-like legs, his bony spine, his chest reddened with drink which was visible at that moment through his half-open shirt, and his monkey-like arms long enough for him to tie his garters almost without bending, scarcely made for a pleasing physique; as for his face, a prodigious nose, reminiscent of that of Cyrano de Bergerac, the pretext for so many historic duels, occupied the most important place. But Lampourde consoled himself with the popular axiom: ‘A large nose never spoiled a face.’ The pupils of his eyes, though still clouded with drunkenness and sleep, displayed cold flashes of steel announcing courage and resolution. On his gaunt cheeks two or three perpendicular furrows, like sword-strokes, that were scarcely love-bites, traced their rigid lines. A mop of intricately tangled black hair rained about this physiognomy fit to be sculpted on a violin neck, which, however, none chose to mock, so disturbing, mocking and ferocious was his expression.

— ‘May the plague take the creature that comes to disturb my joys, and muddy my Anacreontic dreams! I was happy; the most beautiful princess on earth greeted me graciously. You’ve driven her away!’

— ‘Enough of your nonsense,’ cried Mérindol, impatiently, ‘lend an ear, and your attention, for a moment or two.’

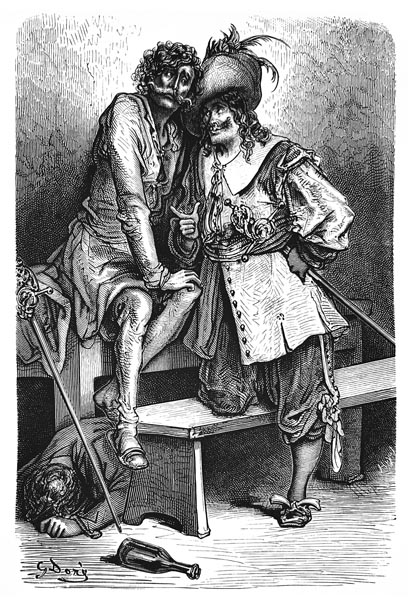

— ‘I never listen to anyone when I’m drunk,’ Lampourde replied majestically, propping himself on his elbow. ‘Besides, I have funds, ample funds. Last night we robbed an English lord decked out with pistoles; I’m eating and drinking my share. But a game or two of lansquenet, and it will soon be gone. So, tonight, to serious business. Meet me at midnight at the centre of the Pont-Neuf, by the foot of the statue of the bronze horse. I shall be there, fresh, clear, alert, in full possession of my faculties. We will tune our flutes, and agree on my share, which should be considerable, for I like to believe that no one bothers a brave man like me for the sake of base rascality, insignificant theft, or petty peccadilloes. Decidedly, theft bores me; I only commit murders now; it’s nobler. We are leonine carnivores, not predatory beasts. If it’s a matter of killing, I’m your man, and even then, the victim must be allowed to defend himself. My victims are so cowardly sometimes, it disgusts me. A little resistance heartens the work.’

‘If it’s a matter of killing, I’m your man…’

— ‘Oh! Have no fear on that score,’ replied Mérindol with a wicked smile. ‘You’ll find an opponent to address.’

— ‘So much the better,’ replied Lampourde, ‘it’s been long since I’ve fought with someone of a skill to equal mine. But that’s enough. On that note, goodnight, and allow me to sleep.’

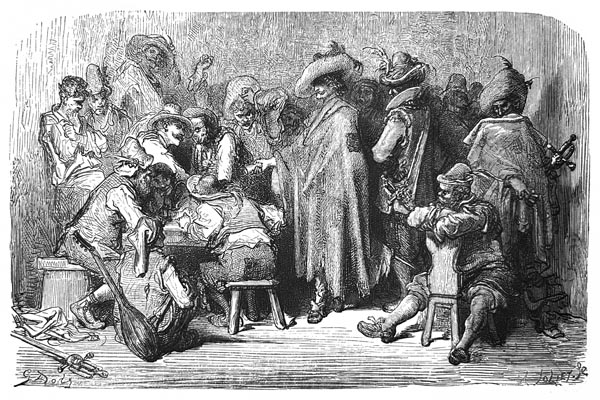

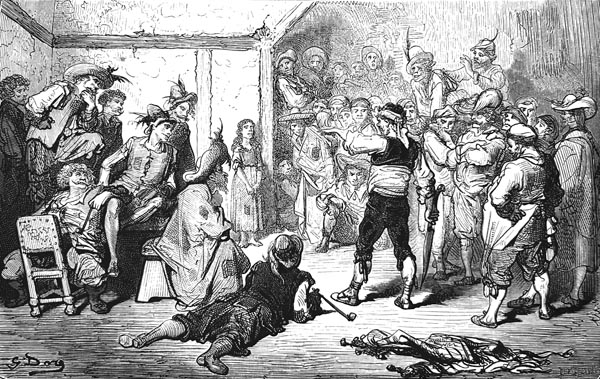

Once Mérindol had departed, Jacquemin Lampourde attempted to rest, but in vain. Sleep, once interrupted, failed to return. The swordsman rose, shook his companion, roughly, who was still snoring beneath the table, and the pair went off to a gambling den where lansquenet and basset (both card games involving a banker) were played.

‘…The pair went off to a gambling den where lansquenet and basset were played.’

The participants were drunkards, swordsmen, rogues, lackeys, clerks, and a few naive bourgeois brought there by loose women, poor pigeons destined to be plucked alive. One heard only the sound of dice rolling about in their cup, and the rustle of cards being shuffled, for the players were customarily silent, except, in the event of a loss, when they emitted a few blasphemous interjections. After his luck alternating between good and bad, a vacuum, which Nature and Man especially abhor, occupied Lampourde’s purse. He wanted to play on account, but that was not common currency in the place, where the players, on receiving their winnings, bit hard on the coins to prove the louis were not gilded lead, nor the silver testers made of the tin from which spoons were cast. He was forced to withdraw naked as an infant Saint John, having entered like a great lord, brandishing a pistol in each hand!