Théophile Gautier

Captain Fracasse (Le Capitaine Fracasse)

Part II: Chapters VI-X

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter VI: The Result of a Snowstorm.

- Chapter VII: In Which This Novel Justifies its Title.

- Chapter VIII: Matters Become Complicated.

- Chapter IX: Swords, Sticks, and Other Goings-On.

- Chapter X: A Face at the Window.

Chapter VI: The Result of a Snowstorm

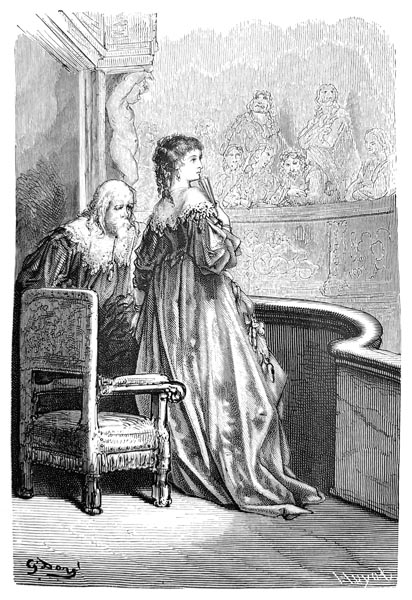

As one might imagine, the actors were highly satisfied with their stay at the Château de Bruyères. Such windfalls did not often come their way in that nomadic life; the Tyrant had doled out to each their share of the fee, and their fingers’ affectionate titillations stirred a few pistoles in the depths of pockets often accustomed to serve as inns for the devil. Zerbina, radiating a restrained, mysterious joy, accepted, with good humour, her comrades’ mocking comments as to the power of her charms. She triumphed, and thereby enraged Serafina. Only Leander, still quite exhausted from the nocturnal beating he had received, seemed reluctant to share in the general gaiety, though he affected a smile, even if it was only that of a dog, at the tips of his teeth, so to speak. His movements were constrained, and the jolts the carriage experienced sometimes forced a significant grimace from him. When he judged that no one was looking, he rubbed his shoulders and arms with his palms; concealed manouevres which might have deceived the other actors, but failed to escape the inquisitive, and sarcastic eyes of Scapin, always on the lookout for misadventures on the part of Leander, whose conceit was particularly unbearable to him.

The collision of a wheel with a rather large stone, which the wagon-driver had failed to see, made the gallant fellow utter an ‘Ouch!’ of anguish and pain, whereupon Scapin began a little speech, under the pretence of pitying him.

— ‘My poor Leander, why are you moaning and lamenting so? You seem as worn out as the Knight of the Woeful Countenance (Don Quixote) when he capered naked in the Sierra Morena as a love-penance (see Cervantes’ ‘Don Quixote’, Chapter XXV), in imitation of Amadis of Gaul on the Rock of the Hermitage (see ‘Amadis de Gaula’, revised and published by Garcí Rodríguez de Montalvo, 1508, Chapter 3). You act as if your bed was made of sticks, and not soft mattresses with sheets, quilts, and pillows, a bed in short more likely to break limbs than grant them rest, so downtrodden are you, so sickly your complexion, and so blackened your eyes. From all this, it appears that Morpheus failed to visit you last night.’

— ‘Morpheus may have lingered in his cave, but that little god Cupid is a prowler who needs no lantern to locate a door in a corridor,’ replied Leander, hoping to divert the suspicions of his enemy Scapin.

— ‘I am a mere valet in Comedy,’ Scapin replied, ‘and have no experience as regards matters of gallantry. I myself have never made love to beautiful women; but I know enough to be aware that the god Cupid, according to the poets and writers of romances, uses his arrows on those he wishes to cause distress, and not thumps from his bow.’

— ‘What on earth do you mean,’ Leander hastened to interrupt, worried by the turn the conversation was taking, ‘by such subtlety, and mythological reference?’

— ‘Not a thing, except that you have there on your neck, a little above your collarbone, though you try to hide it with your handkerchief, a black mark which tomorrow will be blue, the day after that green, and then yellow, until it fades to leave the natural colour behind, a mark which looks devilishly like the authentic signature of a blow from a stick, as if writ on calfskin or vellum, if you prefer that image.’

— ‘Doubtless,’ replied Leander, whose pallid complexion had turned red up to the tips of his ears, ‘some dead beauty, in love with me during her life, must have kissed me in dream while I slept. The kisses of the dead leave bruises on the flesh, as all know, which astonish us when we wake.’

— ‘This dead, and somewhat fantastical, beauty, arrives at just at the right moment,’ replied Scapin; ‘but I would have sworn that vigorous kiss was applied by lips of wood.’

— ‘Wicked mocker, and jester that you are,’ said Leander, ‘you infringe on my sense of modesty. I attributed to the dead, modestly, what might be more aptly claimed by the living. Unlearned and rustic as you affect to be, you have surely heard of such pretty signs, spots, bruises, and teeth-marks; traces of the playful frolics that lovers are accustomed to indulge in together?

— ‘Memorem dente labris notum’, interrupted the Pedant, happy to quote Horace (‘the usual mark of tooth on lip’, see the ‘Odes’ Book I, 13).

— ‘The explanation appears rational,’ replied Scapin, ‘and is supported by suitable authorities. Yet the mark is of such a length, that this nocturnal beauty, dead or alive, must have had in her mouth the single tooth which the Phorkyads (in Greek mythology) lent each other in turn.’

Leander, filled with fury, wanted to hurl himself at Scapin, and punish him, but the pain from the beating, which his sore ribs still felt so keenly as did his back striped like a zebra, was such that he seated himself again, postponing his revenge until a more fitting time. The Tyrant and the Pedant, accustomed to these quarrels, which amused them, encouraged the pair to reconcile. Scapin promised never to allude to the matter. ‘I will absent,’ he said, ‘from my discourse, all mention of wood in any of its forms, whether cut-logs, estate-trees, bed-frames, or even heartwood.’

During this interesting altercation, the cart rumbled on, and they shortly arrived at a crossroads. A crude wooden cross, split by the sun and rain, supporting a Christ whose one arm had detached itself from his body and, attached only by a rusty nail, hung sinisterly, occupied a grassy mound, and marked the junction of the roads.

A pair of men, leading a trio of mules, had halted at the crossroads, seemingly waiting for someone to pass by. One of the mules, as if impatient at standing still, shook its head, which was adorned with pompoms and tassels of every colour and a silvery frisson of bells. Although leather blinkers embroidered with studs prevented it from looking to right or left, it had sensed the approach of the wagon; the anxious twitching of its long ears testified to its curiosity, its curling lips revealing its teeth.

— ‘The Colonel is pricking her ears, and showing her gums,’ said one of the men. ‘Their cart must be near, now.’

Indeed, the actors’ wagon quickly reached the crossroads. Zerbina, seated at the front of the cart, glanced swiftly at the men and animals whose presence in this place seemed not to surprise her.

— ‘By God! There’s gallant equipage,’ said the Tyrant, ‘and fine Spanish mules that will cover fifteen or twenty leagues a day. If we had mules like that, we’d soon reach Paris or thereabouts. But who the Devil are they waiting for? Doubtless it’s a relay arranged for some lord or other.’

— ‘No,’ answered the Duenna, ‘that lead-mule is saddled with blanket and cushion as if for a woman.’

— ‘Then,’ said the Tyrant, ‘it’s a kidnap they plan, for those two squires in grey livery seem very suspicious.’

— ‘Perhaps it is,’ replied Zerbina with a smile, an equivocal expression on her face.

— ‘Is the lady they seek among us?’ said Scapin, as one of the two squires approached the wagon, as if wishing to parley before resorting to violence.

— ‘Oh! Why ask?’ added Serafina, casting a disdainful glance at the Soubrette, which the latter sustained with quiet impudence: ‘There are those who willingly leap into the arms of their captors.’

— ‘It’s not everybody who can be kidnapped so,’ replied the Soubrette; ‘the wish is not enough, one also needs prior agreement.’

The conversation had reached this point, when the squire, signalling to the wagon-driver to rein in his horses, asked, beret in hand, if Mademoiselle Zerbina was not in the carriage.

Zerbina, lively and nimble as a snake, poked her little brown head out of the awning, and answered the question herself; then she jumped to the ground.

— ‘Mademoiselle, I am at your command,’ said the squire in a gallant and respectful tone.

The Soubrette puffed out her skirts, ran her finger around her bodice, as if to give some ease to her chest, and, turning towards the actors, deliberately gave them this little speech:

— ‘My dear comrades, forgive me if I must leave you like this. Sometimes passing Fortune demands one seizes the lock of hair she presents to one’s eyes, in so opportune a manner that it would be pure foolishness not to grasp it with both hands; for the chance once lost is gone forever. Her face, which until now had only shown itself to me as sullen and gloomy, grants me a graceful smile. I shall profit by her goodwill, doubtless fleeting. In my humble role of maid, I could only aspire to a Mascarilla (a thieving valet in Italian comedy) or a Scapin. Only the valets court me, while their masters make love to the Lucindas, the Leonoras, and the Isabellas; the lords hardly deign, as they pass, to seize my face and plant a kiss on my cheek, as they slip a silver half-louis into the pocket of my apron. I have found a mortal of finer taste, who considers that, off-stage, the maid is as good as the mistress, and as the role of Zerbina does not require too absolute a show of virtue, I judged it unnecessary to drive that gallant man to despair whom my departure greatly annoyed. Come then, let me unload my trunks from the back of the cart, and receive my farewells. I will meet you some day or other in Paris, for I am an actress at heart, and could never be unfaithful to the theatre for very long.’

The men took Zerbina’s trunks, and balanced them carefully on the pack mules; the Soubrette, aided by the squire who held her foot, jumped on the Colonel’s back as lightly as if she had studied the art in some equestrian academy, then striking her heel against the flank of her mount, set off, giving a little wave of her hand to her comrades.

— ‘Good luck, Zerbina,’ shouted the members of the troupe, all except Serafina, who held a grudge against her.

— ‘Her departure is unfortunate,’ said the Tyrant, ‘I would have liked to retain the services of that excellent maid; but she gave no other commitment to us than mere whim. We will have to amend the role of maid to duenna or chaperone in our performances, though somewhat less pleasing to the eye than a roguish face; but Dame Leonarda has a sense of comedy, and knows the art thoroughly. We shall manage all the same.’

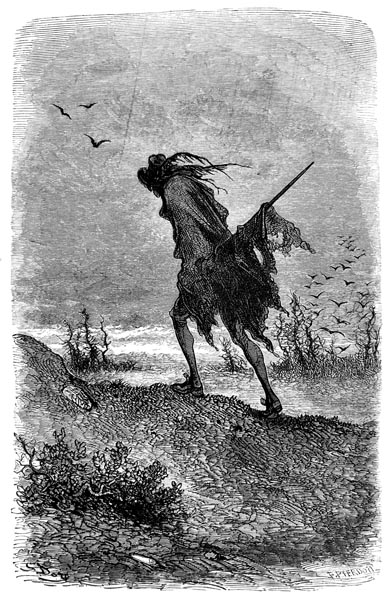

The wagon set off again at a pace somewhat faster than that of the previous oxcart. It crossed a stretch of countryside that contrasted in appearance with the physiognomy of the moorland they had navigated. White tracts of sand had been replaced by reddish soil providing more nourishment for vegetation. Stone houses, announcing a degree of prosperity, appeared here and there, surrounded by gardens enclosed by hedges already stripped of leaves, in which the fruit of the wild roses, their rosehips, were turning red, while the sloe berries were turning blue. At the edge of the road, trees of fine stature raised their vigorous trunks, stretching out strong branches, whose yellow spoils littered the surrounding grass or fled at the whim of the breeze before Isabella and Sigognac, who, tired of the cramped pose they were obliged to maintain in the wagon, were relaxing by walking a little. Matamore had taken the lead, and in the red glow of evening could be seen on the crest of the hill, his frail skeleton a dark silhouette, which, from a distance, seemed as if skewered on his rapier.

‘Matamore had taken the lead…’

— ‘How is it,’ Sigognac said to Isabella as he walked, ‘that you, who have all the manners of a young lady of high lineage, as is seen by the modesty of your conduct, your sober language, and fine choice of words, are thus attached to this wandering troupe of actors, good people, no doubt, but not of the same ilk as yourself?’

— ‘Please do not think,’ Isabella replied, ‘however gracious I may appear, that I am some unfortunate queen or princess driven from her kingdom, and reduced to the sad condition of earning her living on the stage. My story is quite a simple one, and since I have aroused your curiosity somewhat, I will tell you something of my life. Far from having been brought to the state I am in by some fatal catastrophe, some unheard-of disaster or romantic adventure, I was born so, being, as they say, a child of the theatre. Thespis’ chariot was my birthplace, and my travelling home. My mother, who played tragic princesses on the stage, was a most beautiful woman. She took her roles seriously, and even off-stage would hear only of kings, princes, dukes, and other grand folk, treating her tinsel crown and gilded wooden sceptre as if they were real. When she exited to the wings, she trailed the false velvet of her dresses so majestically one would have thought it a river of purple, or the train of a royal mantle. Being proud then, she stubbornly closed her ears to the confessions, requests, and promises of those lovers who always flutter around actresses like moths around a flame. One evening, in her dressing room, when some blond boy sought to take liberties with her, she even rose, and cried out, as if she were Tomyris, queen of Scythia: ‘Guards! Let him be seized!’, in so sovereign, disdainful, and solemn a tone that the young gallant, completely speechless, shrank back in fear, not daring to advance his suit. Now, this unusual show of pride, and the constant rebuffs meted out by an actress, one of a tribe always suspected of loose morals, having come to the attention of a noble and powerful prince, were thought by him to show good taste, and he said to himself that contempt for the common and profane could only proceed from a generous soul. As his rank in society matched that of a queen in the theatre, in her eyes, he was received in a gentler manner and with less fierce a frown. He was young, handsome, spoke well, was insistent, and possessed the great advantage of being nobly-born. What more can I say? On that occasion the queen did not call for her guards, and you see in me the fruit of their beautiful love.’

— ‘That,’ said Sigognac, gallantly, ‘perfectly explains the unparalleled grace you command. Princely blood flows in your veins. I might have guessed!’

— ‘The affair,’ Isabella continued, ‘lasted longer than theatrical intrigues usually do. The prince found in my mother a fidelity that stemmed as much from pride as from love, but which never wavered. Unfortunately, matters of state intervened; he was involved in wars or embassies abroad. An illustrious marriage, which he delayed as long as he could, was negotiated in his name by his family. He had to yield, as he had no right to disrupt, because of a lover’s whim, an ancestral line, established as far back as Charlemagne, or end that lineage in himself. My mother was offered quite large sums of money to soften the rupture which had become necessary, protect her from want, and provide for my upbringing and education. But she would hear none of it, saying that she would never accept the purse without the heart, and that she preferred that the prince be indebted to her rather than she be indebted to him; for she had given him, in her extreme generosity, what he could never repay. ‘Nothing before, nothing after,’ such was her motto. So, she continued her role as a tragic princess, but with a heavy heart, and languished till her death, which was not long in arriving. I was then a little girl of eight years old; I played children, and cupids, and other little roles appropriate to my age and intelligence. The death of my mother caused me grief beyond my years, and I remember I had to be whipped one time when I was forced to play one of Medea’s children. Yet the pain was soothed by the cajoling of the actors and actresses who pampered me as best they could, and as if by chance, always placed some treats in my little basket. The Pedant, who was part of our troupe, and seemed to me then just as old and wrinkled as he is today, took an interest in me, teaching me about recitation, harmony, and poetic metre, ways of speaking and listening, poses, gestures, facial expressions congruent with speech, and all the secrets of the art in which he excels, although only a provincial actor, for he possesses learning, having been a schoolteacher, though expelled for incorrigible drunkenness. Amidst the apparent disorder of a vagabond life, I remained pure and innocent, for to my companions who had seen me in the cradle, I was a sister or a daughter, and as for the gallants I knew how to keep them at an appropriate distance, by adopting a cold, reserved, and discreet manner, so maintaining, off-stage, my role as an ingénue, without hypocrisy or false modesty.’

Thus, as they walked, Isabella told the charmed Sigognac the story of her life and adventures.

— ‘And the name of this nobleman,’ said Sigognac, ‘do you know it, or is it forgotten?’

— ‘It might be dangerous for my peace of mind to repeat it,’ replied Isabella, ‘but it has remained engraved in my memory.’

— ‘Is there any evidence of his affair with your mother?’

— ‘I have a decorative shield with his coat of arms,’ said Isabella, ‘it is the only valuable gift of his that my mother kept, because of its noble and heraldic significance which offset in her mind the notion of material value, and if it would interest you, I will show it to you some day.’

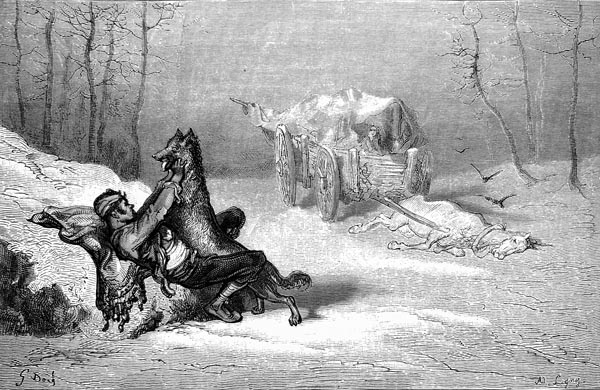

It would be too tedious to follow the Chariot of Comedy yard by yard, especially since the journey was made in a short space of time, without the occurrence of any adventure worth remembering. I will therefore skip a few days, and join the troupe again near Poitiers. The receipts had been insubstantial, and hard times were upon them. The Marquis de Bruyères payment had finally been exhausted, as well as Sigognac’s pistoles, his sense of delicacy obliging him to relieve, to the extent of his meagre resources, his comrades in distress. The chariot, drawn by four vigorous beasts at the start, was now dragged forward by a single horse, and what a horse! A wretched nag who seemed to have been fed on barrel-hoops, instead of hay and oats, so prominent were his ribs. His hip-bones pierced the skin, and the relaxed muscles of his thighs were outlined by large flabby wrinkles; bony growths, spavins, swelled his legs bristling with long hair. On his withers, due to the pressure of a collar whose padding had vanished, bloodstained scratches were ever more vivid, and marks of the whip scarred the bruised flanks of the poor creature. His face was a complete poem of melancholy and suffering. Behind his eyes, one would have thought the deep sockets had been hollowed out with a scalpel. His bluish orbs had the dull, resigned, reflective look of an overworked animal. The result of those careless and useless blows, was sadly visible there, and a snap of the reins could no longer draw a spark of life from him. His tremulous ears, one of which was split at the tip, hung piteously on either side of his brow and, with their oscillations, punctuated the uneven rhythm of his progress. The threads of a lock of mane, turned from white to yellow, were entangled in the headpiece, the leather of which was badly worn due to the bony protuberances of the cheeks, highlighted by their meagreness. The cartilages of the nostrils oozed moisture from laboured breathing, and the worn jaws pouted in sullen lips.

On his white coat, speckled with red, sweat had traced streaks like those with which rain makes on plastered walls, agglutinised the flakes of hair beneath his belly, stained his lower limbs, and made a pitiful cement of his droppings. Nothing could be more lamentable to see, and the horse Death rides in the Book of Revelation would have seemed a dashing beast, fit to parade at equestrian displays, beside this pitiful and disastrous animal whose shoulders seemed to become more disjointed at every step, and who, with painful gaze, seemed to invoke the crowning mercy of the knacker’s final blow. The temperature falling rapidly, he walked amidst the steam rising from his flanks and nostrils.

There were now only three women in the cart. The men went on foot so as not to overload the wagon, which it was not difficult for them to keep up with, and even outpace. With only unpleasant thoughts to express, they remained silent, and walked in solitary fashion, wrapping themselves in their cloaks as best they could.

Sigognac, well-nigh discouraged, wondered if he would not have done better to remain in the dilapidated castle of his fathers, even if he died of hunger there beside his crude coat of arms, in silence and solitude, than wander the roads with these bohemians.

He thought of brave Pierre, of Bayard, Miraut, and Beelzebub, his faithful companions in that tedious existence. His heart sank regardless, and a nervous spasm rose from his chest to his throat, the kind which usually resolves itself in tears; but a glance at Isabella, seated on the front of the wagon, and wrapped tightly in her cloak, strengthened his courage. The young woman smiled at him; she did not seem upset by their state of misery; her mind was content; what did the sufferings and fatigues of the body matter?

The landscape which they traversed was hardly likely to dispel his melancholy. In the foreground writhed the convulsive skeletons of old elm trees, tormented, twisted, lopped, whose black branches like capricious filaments were highlighted against a low sky, yellowish-grey in colour, and dense with snow, which allowed only a livid light to filter through; in the middle-distance, stretched plains devoid of cultivation, bordered near the horizon by bare hills, or lines of russet-hued woods. From time to time, a cottage like a chalky stain, sending upwards a slight spiral of smoke, appeared between the close mesh of twigs that constituted its fencing. The ravine created by a gutter furrowed the earth with a long scar. In spring, this countryside, dressed in verdure, might have seemed pleasant; but, clad in the grey livery of winter, it appeared merely monotonous, impoverished, and sad. From time to time, a farmhand, or an old woman bent beneath a bundle of dead wood, passed by, haggard-looking and ragged, who, far from animating this desert, on the contrary accentuated its solitude. Magpies, hopping over the brown earth, their tails sticking from their rumps like closed fans, seemed to be its true inhabitants. They chattered at the sight of the wagon as if communicating their thoughts about the actors, and danced in front of them in a derisory way, like the wicked, heartless birds they are, insensitive to the misery of the poor world.

A bitter breeze whistled about the troupe, plastering their thin capes to their bodies, and slapping their faces with its chapped fingers. Snowflakes soon mingled with the whirlwinds of air, rising, falling, criss-crossing each other without reaching the ground, or lodging anywhere, so strong were the gusts. They became so densely crowded that they formed a kind of white fog a few steps from the blinded pedestrians. Through this silvery swarming cloud, the nearest objects lost their true appearance, or were no longer distinguishable.

— ‘It seems,’ said the Pedant, who was walking behind the cart to shelter himself a little, ‘that the heavenly housekeeper is plucking geese up there and shaking the down from her apron all over us. Their flesh would please me more, and I would be man enough to eat it even without lemon or spices.’

— ‘Even without salt,’ added the Tyrant, ‘for my stomach no longer recalls that omelette whose eggs chirped when they were broken on the edge of the pan, and which I swallowed under the sarcastic and fallacious title of breakfast, despite the little beaks that bristled within it.’

Sigognac had also taken refuge behind the wagon, and the Pedant said to him: ‘This is dreadful weather, Monsieur le Baron, and I regret your having to share our bad fortune, yet this is but a temporary reversal, and though we are not progressing swiftly, we are nonetheless nearing Paris.’

— ‘I was not raised to a life of comfort,’ replied Sigognac, ‘so I am scarcely one to be troubled by a few snowflakes. It is these poor women whom I pity, obliged, despite their gender, to endure fatigue and privations like country cart-drivers.’

— ‘They have been accustomed to do so for a long while, and what would be challenging for ladies of quality, or bourgeois women, no longer seems painful to them.’

The storm was intensifying. Driven by the wind, the snow blew like white smoke, skimming the ground, and only halting when it was blocked by some obstacle, the slope of a hill, a pile of scree, a hedge, or the bank of a ditch. There, it piled up prodigiously quickly, overflowing in a cascade on the other side of the temporary dike. At other times it formed spirals like a hurricane, and rose in whirls to the sky, to descend again creating heaped masses which the storm immediately dispersed. A few minutes had been long enough for it to powder Isabella, Serafina and Leonarda with its whiteness, beneath the fluttering canvas of the cart, though they had taken refuge at the very back, sheltered by a wall of luggage.

Stunned by the whiplash from this driven snow and air, the horse was barely able to advance. He was panting, his flanks were heaving, and his hooves slipped at every step. The Tyrant took him by the bridle and, walking beside him, supported him somewhat with hand and arm. The Pedant, Sigognac, and Scapin pushed against the wheels. Leander cracked the whip to excite the poor beast: to strike him would have been pure cruelty. As for Matamore, he had lagged somewhat behind, for he was so light in weight, given his phenomenal leanness, that the wind prevented his moving forward, though he grasped a stone in each hand, and had filled his pockets with pebbles for ballast.

The snowstorm, far from abating, raged more furiously, driving onwards the mass of white flakes which was agitated with a thousand eddies like the foaming crests of an ocean wave. The gale waxed so furious that the actors were forced, though they were in haste to reach the village, to halt the wagon, and steer it away from the wind. The poor nag could stand it no longer; his legs stiffened; shivers ran over his steaming skin bathed in sweat. One more effort, and he would have fallen dead; already a drop of blood was pearling in his nostrils, widely dilated due to the pressure on his chest, and glassy gleams traversed the orbs of his eyes.

In the dark it is easy to imagine terrible things. Darkness readily prompts dread, but the horror of whiteness is less generally appreciated. However, nothing could have felt more sinister than the situation our poor actors were in, pale with hunger, blue with cold, blinded by snow, and lost somewhere on the road, amidst the dizzying whirlwind of icy grains enveloping them on every side. They huddled beneath the tarpaulin to allow the snowstorm to pass, pressing against each other to benefit from one another’s warmth. At last, the gusts faded, and the snow, suspended in the air, fell less tumultuously to the ground. As far as the eye could see, the countryside had disappeared beneath a silvery shroud.

— ‘Where’s Matamore,’ said Blazius; ‘has the storm perchance blown him as high as the moon?’

— ‘Indeed,’ added the Tyrant, ‘I don’t see him. He may be huddled beneath our scenery in the depths of the cart. Hey! Braggart! Shake a leg if you’re slumbering there, and answer the call.’

Matamore spoke not a word. No human shape stirred beneath the heap of old canvas.

— ‘Ho there! Braggart!’ the Tyrant bellowed repeatedly, in his loudest tragedian’s voice, and in a tone that would have awakened the Seven Sleepers, and their dog, in that cave of theirs.

— ‘We’ve not seen him, for a while,’ said the actresses, ‘blinded as we were by whirling snow, but we were not much concerned by his absence, thinking he was but a few steps from the wagon.’

— ‘Lord!’ said Blazius, ‘This is odd! I hope nothing serious has happened.’

— ‘Doubtless he took shelter behind some tree trunk during the worst of the storm,’ said Sigognac, ‘and will soon rejoin us.’

They decided to wait a few minutes, before setting out in search of him. Nothing could be seen on the road, though against the background whiteness, even if it was twilight, a human form should have been readily visible even at a considerable distance. Night, which descends so swiftly after the few brief hours of December daylight, had fallen, but without bringing with it complete darkness. The glimmer of snow fought with the shadows, and by a strange visual reversal it seemed as if what light there was shone from the ground. The horizon betrayed itself as a line of white, and was still apparent in the far distance. The forms of the darkened trees, powdered with snow, appeared in outline like those arboreal patterns with which the frost coats window panes and, from time to time, snowflakes, shaken from some branch or other, fell like the silver tears adorning funeral palls, from the shadowy canopy. It was a spectacle full of melancholy; a dog began to howl like a lost soul, as if to give voice to the desolation of the landscape and express the heartbreaking desolation of the scene. Sometimes it seems that Nature, growing weary of silence, confides her secret sorrows to the moans of the wind, or the lamentations of some creature.

How lugubrious, in the silence of the night, is such desperate barking which ends in a moan, and which seems to be provoked by the passage of spectres invisible to the human eye! The instinct of the beast, in communion with the soul of things, senses impending misfortune, and deplores it before it is known. There is in such a howling interspersed with sobs, a terror of the future, the anguish of death, and a voice of dismay provoked by the supernatural. The most steadfastly courageous cannot hear it without being moved, and the cry makes the hair on one’s flesh stand on end, like the passage of that spirit of which Job speaks (see Job 4:15).

The barking, at first distant, drew nearer, and they eventually distinguished in the midst of the plain, seated on its rear in the snow, a large black dog, muzzle raised to the heavens, seemingly whining this gargled lament.

— ‘Something has happened to our poor comrade,’ cried the Tyrant. ‘That cursed beast is howling as if for the dead.’

The women, their hearts heavy with a sinister foreboding, made the sign of the cross, most devoutly. Isabella, virtuously, murmured the beginning of a prayer.

— ‘We must search for him without further delay,’ said Blazius, ‘bearing the lantern; its light will serve as his guide, his pole star, if he has strayed from the road, and wandered into the fields; for amidst such snow which has shrouded the highway in white, it is easy to go astray.’

A flint was struck, and the candle-end, in the belly of the lantern, once lit, cast a bright enough light through its panes made of thin horn to be seen from afar.

The Tyrant, Blazius, and Sigognac set out on their quest. Scapin and Leander remained to guard the wagon and reassure the women, who were increasingly concerned about the whole venture. To add to the gloom of the scene, the black dog was still howling desperately, and the wind driving its aerial chariot over the countryside with a dull murmur, as if bearing souls on a journey.

The storm had so stirred the snow as to erase all traces, or at least to render imprints uncertain. Darkness made the search difficult, and when Blazius angled the lantern towards the ground, he sometimes found the Tyrant’s large hollow footprints moulded in the white dust, but never those of Matamore, which, had he come that far, being no heavier than that of a bird, would scarcely have marked it.

They walked thus for half a mile or more, raising the lantern to attract the attention of the lost actor, shouting at the top of their lungs: ‘Matamore! Matamore! Matamore!’

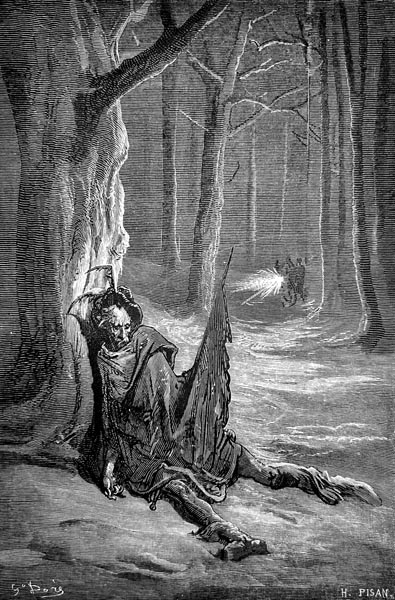

This cry, similar to that which the ancients addressed to the deceased’s corpse before leaving the place of burial, was met with silence, or some bird flew in fear, chirping with a sudden flutter of wings, to lose itself deeper in the night. Sometimes an owl, offended by the light, hooted in a lamentable manner. Finally, Sigognac, who had keen eyesight, thought he could make out amidst the shadows, at the foot of a tree, a figure of phantasmal appearance, strangely stiff, and sinisterly motionless. He warned his companions, who hastened with him in that direction.

It was, indeed, poor Matamore. His back was leaning against the tree, and his long legs were stretched on the ground, half-concealed under a covering of snow. His long rapier, which he never removed, formed an odd angle with his torso, a thing which would have appeared laughable in any other circumstance. He moved no more than a tree-stump does, as his comrades approached. Troubled by his motionless attitude, Blazius directed the beam of light onto Matamore’s face, and almost let the lantern fall, so much terror did the sight cause him.

‘It was, indeed, poor Matamore.’

The mask, thus illuminated, no longer displayed the colours of life. It was pale as wax. The nose, pinched at the sides by Death’s gnarled fingers, gleamed like a cuttlefish bone; the skin was stretched taut over the temples. Snowflakes had caught on the eyebrows and eyelashes, and the dilated staring eyes looked like orbs of glass. At each end of the whiskers glittered an icicle whose weight made the hair curve downwards. The stamp of eternal silence sealed those lips from which so many joyous boasts had flown, and the skull, sculpted in all its leanness, was already apparent beneath that pallid face, in which the habit of grimacing had dug terrifying comedic folds, which the corpse retained, for it is one of the miserable results of such a life, that such actors lack gravity even in death.

Still harbouring a degree of hope, the Tyrant tried to raise Matamore’s hand, but the arm already stiff, fell back again, solidly, with a noise like a puppet’s wooden arm the string to which has snapped. The poor devil had left the theatre of life for that of the after-world. However, unable to accept that he was dead, the Tyrant asked Blazius if he had not his flask about him. The Pedant never parted with that precious piece of equipment. There were still a few drops of wine left in its depths, and he introduced its neck between the Braggart’s violet lips; but the teeth remained stubbornly clenched, and the liquor spurted out in red drops from the corners of the mouth. Vital breath had forever abandoned the frail clay, for the slightest sign of it would have produced visible steam in that chill air.

— ‘Don’t torment his poor remains,’ said Sigognac, ‘don't you see that he’s dead?’

— ‘Alas! Yes,’ replied Blazius, ‘as dead as Cheops beneath his Great Pyramid. No doubt, stunned by the snowstorm and unable to fight its fury, he halted beneath this tree, and as he had not two ounces of flesh on his bones, his marrow will soon have frozen. In order to make an impression on the Paris stage, he reduced his ration every day, and was thinner from fasting than a greyhound after the race. Poor Braggart, now you are safe from the malice, the beating, kicks, and blows which your role obliged you to suffer! No one will laugh in your face again.’

— ‘What shall we do with his body? interrupted the Tyrant. ‘We cannot leave him here on the edge of this ditch to be torn to pieces by wolves, dogs, and carrion birds, though there is little flesh for even the worms to dine on.’

— ‘No, indeed,’ said Blazius; ‘he was a good and loyal comrade, and since he is light enough, you take his head, I’ll take his feet, and we’ll carry him to the cart. Tomorrow at daylight we’ll bury him in some corner as decently as possible; for, to us histrions, our stepmother of a Church closes the gates of the cemetery, and refuses us the blessing of resting in holy ground. We must rot on the gallows, as dead dogs or horses rot, after entertaining the decent people all our lives. You, Monsieur Baron, you will lead us, and hold the lamp.’

Sigognac nodded his agreement. The two actors bent down and cleared the snow that already cloaked Matamore like a premature shroud, lifted the slender corpse which weighed less than that of a child, and set off preceded by the Baron, who directed the lantern beam in front of them to light the way.

Fortunately, no one was passing by the road at that hour, for it would have appeared a somewhat frightening and mysterious spectacle to the traveller, this funereal group, lit strangely by the reddish rays of the lantern, and casting long, deformed shadows on the white expanse of snow behind them. The thought that some crime or deed of witchcraft was afoot, would doubtless have come to them.

The black dog, as if its role as a crier of doom was over, had ceased its howling. A deathly silence reigned over the distant countryside, for snow has the property of muffling all sound.

For some time Scapin, Leander, and the actresses had been aware of the reddened beam of the little lantern swinging from Sigognac’s hand, casting sudden light on objects and drawing them forth from the shadows in strange or formidable guise till they vanished into the darkness once more. Revealed and hidden, alternately, by this wavering light, the Tyrant and Blazius, linked by the horizontal corpse of poor Matamore, like two words joined by a hyphen, took on an enigmatically lugubrious appearance. Scapin and Leander, moved by anxious curiosity, went to meet the procession.

— ‘Well! What’s this?’ said the valet, once he had reached his comrades. ‘Is Matamore ill that you carry him like this, as stiff as if he’d swallowed his rapier?’

— ‘He’s not ill,’ replied Blazius, ‘indeed, he now enjoys permanent health. Gout, fever, catarrh, gallstones, can no longer afflict him.’

— ‘Then, he’s dead!’ cried Scapin in a tone indicating painful surprise, as he leant over the corpse’s face.

— ‘Very dead, in fact as dead as can be, if there are degrees of that state, for added to the natural chill of death is that of the frost,’ replied Blazius in a troubled voice that betrayed more emotion than the words suggested.

— ‘He has lived his life, as the prince’s companion always declares, in the last act of a tragedy!’ added the Tyrant. ‘But relieve us of this burden a little, if you please. It’s your turn. We have carried our dear comrade far enough without hope of pay or reward.’

Scapin replaced the Tyrant, Leander took over from Blazius, though an undertaker’s work was scarcely to his liking, and the procession resumed its march. In a few minutes, they reached the wagon which had halted in the middle of the road. Despite the cold, Isabella and Serafina had jumped down from the cart, where the Duenna alone still crouched, her owlish eyes open wide. At the sight of Matamore, pale, stiff, and frozen, his face a motionless mask through which the spirit no longer looked forth, the actresses uttered cries of terror and pain. Two tears even sprang from Isabella’s clear eyes, which promptly froze in the harsh nocturnal breeze. Her beautiful hands, red with cold, were clasped together, devoutly, and a fervent prayer for the man, who had so suddenly been swallowed by the trap-door of eternity, rose on wings of faith into the depths of the dark sky.

What was to be done? Their situation was still troublesome. The village where they were to sleep was still four or five miles distant, and when they reached it all the house-doors would have been locked a long time ago and the countryfolk would be asleep; on the other hand, they could not remain in the middle of the road, in the snow, without wood to light a fire, or food to comfort themselves, in the sinister and gloomy company of a corpse, waiting for dawn, which does not break till very late at that time of year.

They decided to advance. The hour’s rest, and a bag of oats Scapin had provided, had restored a little of his vigour to the poor, weary old horse. He seemed refreshed and capable of doing what was required. Matamore’s corpse was placed in the depths of the cart, beneath a piece of canvas. The actresses, not without a certain shudder of fear, seated themselves at the front of the wagon, for death makes a spectre of the friend with whom one was talking but a few hours ago, and he who once amused you now frightens you like a ghost or a monster.

The men walked, Scapin lighting the way with the lantern whose candle had been renewed, the Tyrant holding the horse’s bridle to prevent it from straying. They progressed quite slowly, for the route was difficult; however, after two hours they began to distinguish, at the foot of a fairly steep descent, the first of the village’s houses. The snow had added white sheets to the roofs, which highlighted them, despite it still being night, against the dark background of the sky. Hearing the cart’s iron wheels clanking from afar, the dogs, once disturbed, made a row, and their barking woke others on isolated farms, deep in the countryside. It was a concert of howls, some muffled, others loud, with solo flights, responses, and choruses in which all the canine inhabitants of the neighbourhood took part. Thus, when the cart arrived there, the village was fully awake. More than one head wrapped in a nightcap showed itself at a skylight, or framed in the upper leaf of a half-open door, which made it easier for the Pedant to seek, audibly, lodgings for the troupe. The inn was pointed out to him, or at least the house that served as one, the village being little frequented by travellers, who usually journeyed on farther. This inn was at the other end of the village, and the poor nag had to drag the cart for a little longer; but he smelt the stable, and with a supreme effort, his hooves, tore sparks from the pebbles beneath the layer of snow. There was no mistaking the house; a branch of holly, not unlike those used to sprinkle holy water, hung over the door, and Scapin, raising his lantern, noted the presence of that hospitable symbol. The Tyrant drummed his heavy fists on the door, and soon a clatter of wooden shoes descending a staircase was heard within. A ray of reddish light filtered through the cracks in the wood. The door opened, and an old woman, sheltering, with a wrinkled hand that seemed alight, the flickering flame of a taper, appeared in all the horror of her indelicate negligee. Her two hands being fully occupied, she held between her teeth or rather between her gums, the edges of her coarse linen smock, with the modest intention of hiding from libertine eyes charms that would have made the he-goat at a Witches’ Sabbath flee in terror. She led the actors to the kitchen, planted the candle on the table, rummaged through the ashes of the hearth to awaken some slumbering embers, and soon set a handful of brushwood to crackling; then she ascended to her room to put on a petticoat and a jacket. A fat boy, rubbing his eyes with filthy hands, went to open the gate to the courtyard, led in the cart, removed the horse’s harness, and stabled the poor beast.

— ‘We cannot, however, leave poor Matamore in the carriage, like the body of a deer borne back from the hunt,’ said Blazius, the Pedant, ‘the farmyard dogs would worry at him. He has been baptised, after all; and we must hold a wake over him like the good Christian he was.’

The body of the deceased actor was lifted out, laid out on the table, and covered respectfully with a cloak. Beneath the fabric, the rigidity of death was sculpted in great folds, and the sharp profile of the face was outlined, perhaps more frighteningly so, than if it had been uncovered. Thus, when the innkeeper returned, she almost fell backward with fright at the sight of the corpse which she took to be that of some man the actors had murdered. She held out her aged trembling hands, and began begging the Tyrant, whom she judged to be the leader of the troupe, not to have her slain, promising him absolute secrecy, even under torture. Isabella reassured her, and told her in a few words what had happened. Then the old woman went off to fetch two more candles, and arranged them at the dead man’s head and foot, offering to keep watch with Dame Leonarda, for she had often dealt with the village dead, and knew what had to be performed as regards those sad offices.

These arrangements made, the actors retired to another room, where, with appetites little whetted by the gloomy scenes they had encountered, and touched by the loss of the brave Matamore, they ate only half-heartedly. For perhaps the first time in his life, although the wine was good, Blazius left his glass half-full, forgetting to drink. He must have been heartbroken, indeed, for he was one of those drinkers who wished to be buried beneath the barrel’s tap, so the wine would drip into their mouths, and would have risen from the coffin to cry ‘Santé!’ over a brimming glass of red.

Isabella and Serafina arranged a pallet for themselves in the next room. The men lay down on bales of straw which the stable boy brought. They all slept badly, their slumber interrupted by painful dreams, and rose early, for it was time to proceed with Matamore’s funeral.

For lack of a burial cloth, Leonarda and the hostess had wrapped him in a scrap of old scenery representing a forest, a shroud worthy of an actor, akin to a military coat if a soldier’s corpse had been involved. Some remnants of green paint simulated, on the worn canvas, wreaths and foliage, and gave the effect of a scattering of greenery to honour the body, which was stitched and bundled up like an Egyptian mummy.

A board set on two poles, the ends of which were held by the Tyrant, Blazius, Scapin, and Leander, formed the bier. A large black velvet robe, studded with stars and half-moon shaped spangles, employed for the roles of pontiff or necromancer, served as a decent enough funeral pall.

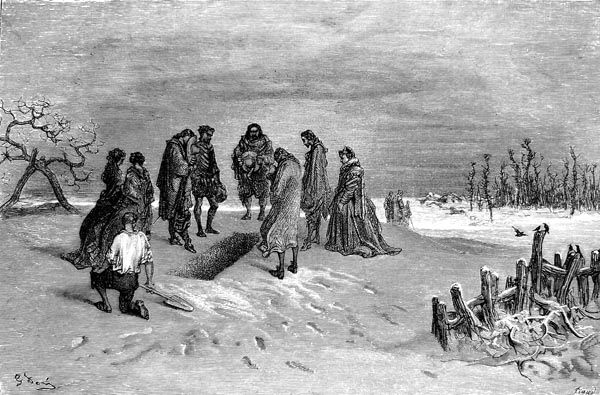

Organised thus, the procession left by a back door opening onto the fields, to avoid the glances and gossip of the curious, so as to reach a vacant lot that the hostess had designated as a serviceable burial plot for Matamore, and one which none would query, the custom being to dispose there of animals that had died of disease; a place unworthy and unsuitable for human remains, mortal clay modelled in the likeness of God above, but the rules of religion are strict, and an excommunicated histrion cannot be buried in holy ground, unless he has renounced the theatre, its works, and its pomp, which was not Matamore’s case.

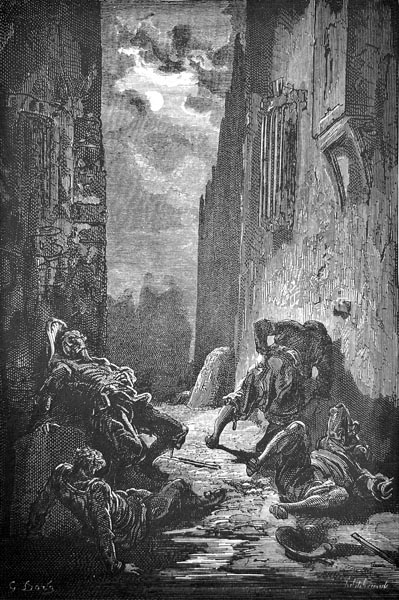

Grey-eyed morning was awake, and was descending the hill slopes with snow underfoot. A cold light spread over the plain, whose whiteness made the pale tint of the sky appear livid. Astonished by the sudden appearance of the procession, which was preceded by neither cross nor priest, and was not on the path that led to the church, a group of countrymen on their way to gather wood halted, and looked askance at the actors, suspecting them of being heretics, sorcerers, or protestants, but nevertheless dared say nothing. Finally, they arrived at a fairly open spot, and the stable boy, who was carrying a spade with which to dig the grave, said that they would do well to stop there. Animal carcasses half-covered with snow littered the ground all about. Equine skeletons, anatomised by vultures and crows, stretched out long, emaciated heads with hollow eye-sockets, at the end of a row of vertebrae, their ribs laid open and stripped of flesh, like the ribs of a fan from which the paper has been torn away. Touches of snow, as if fancifully placed, added to the horror of this charnel-house spectacle by emphasising the projections and articulation of the bones. These spectral creatures seemed those that demons and ghouls ride in their Sabbath cavalcades.

The actors laid the body on the ground, and the boy began to dig vigorously throwing black clods of earth onto the snow, a particularly gloomy scene, as it seemed to the living that the poor deceased, even though he felt nothing, would be colder still on his first night in a grave amidst the frost.

The Tyrant relieved the boy, and the pit was rapidly deepened It already gaped wide enough to swallow the lean corpse in a single bite, when the gathered peasants began to shout ‘Huguenots’ and made as if to attack the actors. A few stones were even thrown, which happily hit no one. Enraged by this rabble, Sigognac raised his sword and ran at the scoundrels, striking them with the flat of his blade, and threatening them with the point. At the sound of the altercation, the Tyrant had leapt from the grave, seized one of the poles from the bier, and was flailing the backs of those who had been knocked down by the Baron’s impetuous rush. The troupe dispersed, shouting and cursing, and Matamore’s funeral rites were then completed.

‘Matamore’s Funeral.’

Lying at the bottom of the hole, the body, sewn into its sylvan canvas, looked more like an arquebus wrapped in green serge, buried so as hide it, than like a human corpse to be interred. When the first shovelfuls pattered down over the meagre remains of the actor, the Pedant, deeply moved, and unable to hold back the tear that fell from the tip of his reddened nose into the pit, like a pearl issuing from the heart, sighed in a doleful voice, by way of a funeral oration, this sentence which was all the eulogy and myriologue (an improvised Greek lament) uttered there: ‘Alas! poor Matamore!’

The honest Pedant, in speaking so, little suspected that he was imitating the words of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, as he handled the skull of the former court jester, Yorick, in Shakespeare’s tragedy.

In a short while the grave was filled. The Tyrant scattered snow over it to conceal the spot, for fear that some insult might be visited on the corpse. This task completed: ‘Now,’ he said, ‘let us leave the place quickly, as we have no more to do here, and return to the inn. Let us hitch up the cart, and take to the open road; for these rascals, if they return in strength, might well assail us. Your sword, and my fists would not suffice. A host of pygmies can overcome a giant, while victory over them would be inglorious, and of scant benefit to us. Even if we disembowelled a half-dozen of these rascals, our loss would be no less, while their death would place us in a difficult position. There would be a lamentation of widows, and a wailing of orphans, which are tiresome and pitiful things that lawyers take advantage of to influence the judge.’

The advice was sound, and was followed. An hour later, the reckoning settled, the wagon was on its way once more.

Chapter VII: In Which This Novel Justifies its Title

At first, they progressed as quickly as the old horse’s strength, restored by a good night’s stay in the stable, and the state of the road, covered with the snow that had fallen the day before, allowed. The country folk challenged by Sigognac and the Tyrant might return to the attack in greater numbers, and it was a matter of putting enough space between themselves and the village to render pursuit useless. Five long miles were travelled in silence, for Matamore’s sad end added funereal thoughts to the melancholy of their situation. Their sole reflection was that one fine day they too might be buried on the side of the road, among the carcasses, and abandoned to remorseless desecration. The wagon, continuing its journey meanwhile, symbolised life, which ever advances without concern for those who fail to maintain the pace, and are left behind, dead or dying, in the ditch. A symbol merely renders the hidden meaning more visible, and Blazius, whose tongue was itching, began to moralise on the theme with many quotations, apophthegms, and maxims that he had memorised in his role as a pedant.

The Tyrant listened silently, with a sullen air. His thoughts were elsewhere, such that Blazius, noticing his comrade’s distracted expression, asked him what he was thinking.

— ‘I am thinking,’ replied the Tyrant, ‘of Milo of Croton, who with a blow of his fist slew an ox, and ate it in a single day. The exploit pleases me, and I feel capable of repeating it.’

— ‘Unfortunately, the ox is lacking,’ said Scapin, entering the conversation.

— ‘Indeed,’ replied the Tyrant, ‘I possess only the fist, and the stomach, for it. Oh, blessed are ostriches who live on pebbles, shards, gaiter-buttons, knife-handles, belt-buckles, and other victuals indigestible to humans. At this very moment, I could even swallow our theatre props. It seems to me that, in digging the hole for poor Matamore, I dug one deep in myself so wide, long, and profound, that nothing can fill it. The ancients were most wise, who followed funerals with a meal, with abundant meat and copious wine, for the greater glory of the dead and the better health of the living. I wish, right now, I could perform that philosophical rite so suitable for drying tears.’

— ‘In other words,’ said Blazius, you desire to eat, you gluttonous ogre. Polyphemus, Gargantua, you disgust me.

— ‘And you, like sand or a sponge, you long to drink,’ replied the Tyrant. ‘You funnel, you siphon, you wineskin, nay wine-barrel, you excite my pity.’

— ‘How sweet and profitable a fusion of our two passions would be!’ said Scapin with a conciliatory air. ‘Here, by the side of the road is a small coppice wonderfully suited to a halt. We could divert the wagon to the spot, and if there are still some provisions left, lunch as best we can, sheltered from the north wind behind a natural screen. The stop will allow the horse time to rest, and permit us to converse, while nibbling a morsel, about the course of action to be taken as regards the troupe’s future, which seems to me devilishly hazy.’

— ‘Your speech is golden, friend Scapin,’ said the Pedant, ‘and we shall indeed exhume from the entrails of the knapsack, which is flatter alas and more deflated than the purse of the prodigal son, a few remnants, the remains of the splendour of former times; pie-crusts, ham-bones, sausage-skins, and scraps of bread. There are still two or three flasks of wine in the chest, the last of a valiant troop. With all that, we can not only stave off but satisfy our hunger and thirst. What a pity that the soil of this inhospitable canton is not like the clay with which certain natives of South America weight their stomachs when their hunting and fishing fails!’ (In the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes, a type of clay called ‘chaco’ or’ pasa’ is eaten, to counter toxins)

The wagon’s course was diverted; it halted amidst the thicket; and the horse once unharnessed began to search beneath the snow for a few scant patches of grass which he tore at with his long yellow teeth. A carpet was spread in an open place. The actors sat around this improvised tablecloth in the Turkish fashion, and Blazius symmetrically arranged the leftovers taken from the carriage, as if it were a bounteous feast.

— ‘Oh, what a beautiful sight,’ cried the Tyrant, in delight. ‘A prince’s butler could not have arranged things better. Though you are a wonderful Pedant, Blazius, your true vocation is that of victualler.’

— ‘I did harbour such an ambition, but adverse fortune thwarted it,’ replied the Pedant modestly. ‘Above all, little bellies, don’t go throwing yourselves at the food greedily. Chew slowly, and with care. Besides, I shall ration the fare, as is done by sailors on rafts after shipwrecks. To you, Tyrant, this ham bone from which a shred of flesh still hangs. With your strong teeth you will crack it open, and philosophically extract the marrow. To you, ladies, this pâté base coated with stuffing in its corners, and basted internally with a very substantial layer of lard. It is a delicate, tasty, and nutritious dish that will make you desire no other. To you, Baron de Sigognac, this piece of sausage; just be careful not to swallow the string tying the skin tight like a purse. It must be set aside for supper, for dinner is an indigestible, excessive and superfluous meal that we may do without. Leander, Scapin and I will be content with this venerable piece of cheese, scowling and bearded like a hermit in his cave. As for the bread, those who find it too hard will have the option of dipping it in water, and removing the crust to carve toothpicks. For the wine, everyone is entitled to a goblet, and as sommelier I ask you to lick your fingernails, so that none is lost.’

Sigognac had long been accustomed to this more than Spanish frugality, and had consumed, in his Castle of Misery, more than one meal whose crumbs the mice would have been embarrassed to nibble, for he himself had played the mouse. However, he could not help admiring the good humour and comic verve of the Pedant, who found something amusing where others would have moaned like calves, and groaned like cattle. What concerned him was Isabella’s state. A marble-like pallor covered her cheeks, and, in the intervals between bites, her teeth chattered like castanets with a feverish movement that she tried in vain to repress. Her thin clothes protected her poorly against the bitter cold, and Sigognac, sitting near her, threw half of his cape over her shoulders, although she resisted, drawing her close to his body to warm her and transfer a little of his vital heat. Isabella warmed herself at this kindly hearth, and a faint blush of modesty appeared on her face.

While the actors were eating, a rather singular noise was heard, to which they paid no attention, at first, taking it to be the effect of the wind whistling through the bare branches of the coppice. Soon the noise became more distinct. It was a sort of hoarse, strident hiss, both non-human and angry, the nature of which was difficult to explain. The women showed a degree of fear.

— ‘If it’s a snake,’ cried Serafina, ‘I will die, so much do those dreadful things inspire my aversion!’

— ‘In these temperatures,’ said Leander, ‘snakes are numbed and, rigid as sticks, they sleep in the depths of their lairs.’

— ‘Leander is right,’ said the Pedant, ‘it must be something else; some creature that haunts groves, that our presence frightens or disturbs. Let’s not interrupt our meal.’

At the sound of this hissing, Scapin had pricked his fox-like ears, which, despite being red with cold, were nonetheless sharp of hearing, and he looked closely in the direction from which it came. Blades of grass rustled as they moved, as if at the passage of some animal. Scapin signalled to the actors to remain motionless, and soon a magnificent gander, neck outstretched, head held high, and waddling with majestic stupidity on his broad webbed feet emerged from the thicket. Two geese, his wives, followed him, trustingly and naively.

— ‘Here’s a roast offering itself up to the spit,’ said Scapin in a low voice, ‘one which heaven, touched by our pangs of starvation, has sent us most opportunely.’

The cunning fellow rose, moved away from the troupe, and executed a semicircle so light-footedly that the snow emitted never a creak beneath his feet. The gander’s attention was fixed on the group of actors whom he looked at with mistrust mingled with curiosity, and whose presence in this usually deserted place, lacked an explanation as far as his limited brain was concerned. Seeing him fully occupied in his contemplation, the histrion, who seemed to be accustomed to such marauding, approached the gander from behind, and flung his cape over him with a movement so precise, so dexterous, and so rapid, that the action lasted less time than it takes to describe it.

Once it was hooded, he rushed upon the bird, and seized it by the neck beneath his cape, which the fluttering wings of the poor, suffocating animal would quickly have sent flying. Scapin, in this pose, resembled that much-admired ancient group called The Child with a Goose (a Hellenistic sculpture, attributed to Boethus of Chalcedon; see the Roman copy in marble of the bronze original, in the Louvre). Soon the gander, strangled, ceased to struggle. Its head bowed limply in Scapin’s clenched fist. Its wings no longer jerked. Its orange morocco-leather booted feet stretched out with a final quiver. It was dead. The geese, its widows, fearing a similar fate, gave a lamentable cluck by way of funeral oration, and returned to the woods.

— ‘Bravo, Scapin, a clever move,’ exclaimed the Tyrant, ‘and as good as any you execute on the stage. Geese are harder to surprise than Gerontes (the French version of Pantalone, a commedia dell’arte character) or Truffaldino (a character likewise derived from Harlequin), being by nature very vigilant and on their guard, as appears from the story where we find that the geese of the Roman Capitol sensed the nocturnal approach of the Gauls, and thus saved Rome (in 390BC, according to the legend). Master goose here, has saved us, in another way, it is true, but one no less providential.’

The goose was bled and plucked by old Leonarda. While she was tearing away its down as best she could, Blazius, the Tyrant, and Leander, plunged into the thicket, gathered pieces of wood, shook off the snow, and piled it in a dry place. Scapin used his knife to carve a stick, stripping it of bark, to serve as a spit. Two forked branches cut short above the knot were planted in the ground as its supports. Thanks to a handful of straw taken from the cart, to which the spark from a flint was applied, the fire was soon alight, and glowing cheerfully, tinting the skewered gosling red, and reviving, with its invigorating warmth, the troupe seated in a circle round the improvised hearth.

Scapin, with a modest air, as befitted the hero of the situation, stood stock still, eyes lowered, his expression softened, turning the goose from time to time, which, in the heat from the embers, took on a beautiful golden colour, very appetising to witness, and gave off an odour of such succulence that it would have made Bonaventure- Catalagironne (General of the Franciscan Order, and one of the negotiators of the Peace of Vervins, 1598) fall into ecstasy, who, in all the great city of Paris, admired nothing so much as the rotisseries of the Rue aux Oües (‘Street of the Geese’, later corrupted to Rue Aux Ours: see Henri Sauval’s ‘Histoire et Recherches des Antiquites de la Ville de Paris, 1724, Volume II, Book II, page 142), and the Rue de la Huchette.

The Tyrant had risen, and was walking about briskly to distract himself and thereby avoid, he said, the temptation to throw himself upon the half-cooked roast, and swallow it spit and all. Blazius was at the cart, extracting from a trunk a large pewter dish used for feasts on stage. The goose was solemnly placed upon it, and around it, beneath the attentions of the knife, spread a blood-stained juice with a most delicious aroma.

The bird was butchered into equal portions, and lunch began anew. This time it was no longer an imaginary or illusory feast. No one, since hunger silenced every conscience, expressed any qualms about Scapin’s actions. The Pedant, who was a fastidious man as regards cuisine, apologised for the lack of slices of bitter orange to seat the goose on, which is an obligatory and regular addition, but was forgiven wholeheartedly for this culinary solecism.

— ‘Now that we are sated,’ said the Tyrant, wiping his beard with his hand, ‘it would be appropriate to consider what to do. There are barely three or four pistoles left in the purse, and my job as treasurer is very close to becoming a sinecure. Our troupe has lost two valuable members, Zerbina and Captain Matamore, nor can we act a comedy in the open air for the amusement of crows, rooks, and magpies. They would decline to pay for their seats, lacking cash, with the possible exception of the magpies, who, it is said, steal coins, jewels, spoons, and tumblers. But it would be unwise to count on such takings. With a horse of the Apocalypse dying between the shafts of our cart, it is quite impossible to reach Poitiers in under two days. Which is most tragic, because by then we risk dying of hunger or cold beside some ditch. Geese don’t emerge from the bushes every day to be roasted.’

— ‘You explain the evil of our situation very eloquently,’ said the Pedant, ‘but fail to suggest a remedy.’

— ‘I think,’ replied the Tyrant, ‘that we should stop at the first village we come across; work in the fields is over. It is the season of long nocturnal vigils. They will gladly let us lodge in some barn or stable. Scapin will rattle the box in front of the doors, and promise an extraordinary and magnificent spectacle to the astonished rustics with the offer of their paying for their seats in kind. A chicken, a joint of ham or beef, a jug of wine, will entitle them to a seat at the front. For them to secure one in the second row, we’ll accept a brace of pigeons, a dozen eggs, an armful of vegetables, a loaf of bread, or any other similar victuals. Country folk, stingy with money, are seldom stingy with provisions, which they have in store, and which cost them nothing, being supplied by good Mother Nature. Though this will not fill our purse, it will assuage our appetites, a vital matter, since the whole economy and health of the body politic depends on the stomach, as Menenius wisely remarked (Agrippa Menenius Lanatus, was a Roman consul in 503 BC. In 494/3 he reputedly used a Greek parable of the limbs refusing to feed the stomach to convince the plebs of the futility of secession, see Livy ‘Ab Urbe Condita’ 2. 32. 8). Then there will be little difficulty in our reaching Poitiers, where I know an innkeeper who will grant us credit.’

— ‘But what play can we perform,’ said Scapin, ‘if the village folk gather at the time appointed? Our repertoire is highly varied. Tragedy or tragicomedy would be pure Hebrew to these rustics, ignorant of history and fable, who have no grasp of the beauty of the French language. We need some good, joyous farce, sprinkled not with Attic salt but with the coarse variety, with plenty of beatings, kicks in the backside, clownish tumbles, and buffoonish Italian-style scurrilities. Captain Matamore’s Rodomontades would have been marvellously suitable. Sadly, Matamore has lived his life, and will deliver his tirades now only in the lines he left behind.’

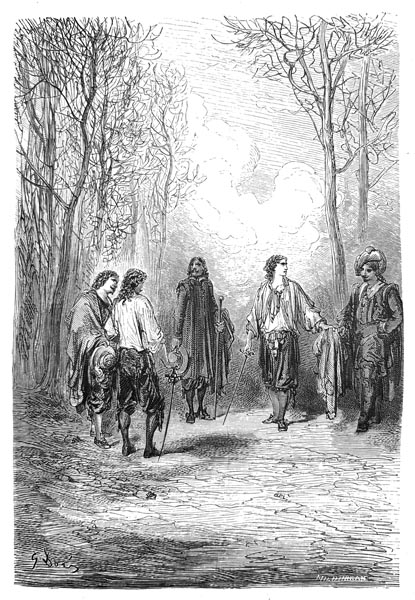

When Scapin had finished, Sigognac signalled with his hand that he wished to speak. A slight blush, a flow of blood sent by yielding though noble pride from the heart to the face, coloured his features, despite the bitter assault of the north wind. The actors remained silent and expectant.

— ‘Though I lack the talent of poor Matamore, I am almost as thin as he was. I will act his role, and replace him as best I can. I am your comrade, and wish to be so completely. Also, I am ashamed to profit from your good fortune yet prove useless to you in adversity. Besides, who in the world cares about the Sigognacs? My manor crumbles in ruins over the tomb of my ancestors. Oblivion cloaks our once glorious name, and ivy erases the coat of arms on our deserted porch. Perhaps one day those three storks which adorn it will shake their silvery wings joyously, and life and happiness will return to that sad hovel, where my youth, devoid of hope, was being wasted. Instead, you who held out your hand to me and urged me to leave that vault, please accept me, frankly, as one of your own. My name shall no longer be Sigognac.’

Isabella placed her hand on the Baron’s arm as if to interrupt him; but Sigognac paid no attention to the young girl’s pleading expression and continued:

— ‘I shall roll up my title-deed to the baronetcy, and hide it at the bottom of my trunk, like a garment that’s no longer worn. Please don’t address me by it again. Let us see if, in disguise, I will be recognised by Fortune. Thus, I succeed Matamore, and will adopt as my nom de guerre: Captain Fracasse!’

— ‘Long live Captain Fracasse!’ shouted the whole troupe, in acceptance. ‘Let applause greet him everywhere!’

His decision, which had astonished the actors at first, was not as sudden as it seemed. Sigognac had already been thinking of it for a long while. He had blushed at behaving in a parasitic manner towards these honest performers who had shared their own resources with him so generously, without ever making him feel that his presence was inconvenient, and he judged it less unworthy of a gentleman to act on stage and bravely earn his share than accept it as an idler, like alms or a stipend. The thought of returning to Sigognac had indeed presented itself to him, but he had rejected the idea as cowardly and shameful. It is not in times of defeat that a soldier should retire from service. Besides, even if he had sought to leave, his love for Isabella would have held him back, and moreover, though he was not given to fantasising, he glimpsed in vague perspective all sorts of intriguing adventures, reversals, and strokes of fortune, which he would have had to renounce in confining himself to his manor house.

Matters thus settled, the horse was hitched to the wagon, and they set off again. Their excellent meal had revived the whole troupe, and all except the Duenna and Serafina, who were unwilling to walk, followed the carriage on foot, thus relieving the poor nag. Isabella leaned on Sigognac’s arm, turning her tender eyes, furtively, towards him on occasion, not doubting that it was for love of her that he had taken the decision to become an actor, something so inimical to the pride of a well-born person. She would have liked to reproach him, but felt she lacked the strength to scold him for a proof of devotion that she would have prevented him from granting if she could have foreseen it, for she was one of those women who ignore their own interests when they love, and only pursue those of their beloved. After a while, finding herself becoming a little weary, she remounted the carriage and curled up under a blanket next to the Duenna.

On either side of the road, a whitened and deserted countryside stretched as far as the eye could see; with no sign of a town, village, or hamlet.

— ‘There goes our chance of a good showing,’ said the Pedant, after having gazed around at the horizon, ‘theatre-goers scarcely seem to be flocking to us in large numbers, and that recipe involving salt-pork, poultry, and bunches of onions, with which the Tyrant whetted our appetites seems to me to be quite compromised. Not even a smoking chimney in sight. Not one traitor of a rooster revealing a steeple below, as far as the eye can see.’

— ‘Have a little patience, Blazius,’ replied the Tyrant, ‘dwellings pollute the air, and it is most healthy to space the villages widely.’

— ‘Well, as regards that, the inhabitants round here have nothing to fear from epidemics, whether of the bubonic plague, termed the Black Death, or sweating sickness, or malignant and confluent smallpox, all of which, according to the medical men, arise from overcrowding. I’m afraid, if this continues, that our Captain Fracasse won't be making his debut anytime soon.’

While he was speaking, the day was rapidly fading, and beneath a thick curtain of leaden cloud one could barely distinguish the faint reddish glow that marked the place where the sun was setting, tired of illuminating the livid, gloomy landscape dotted with crows.

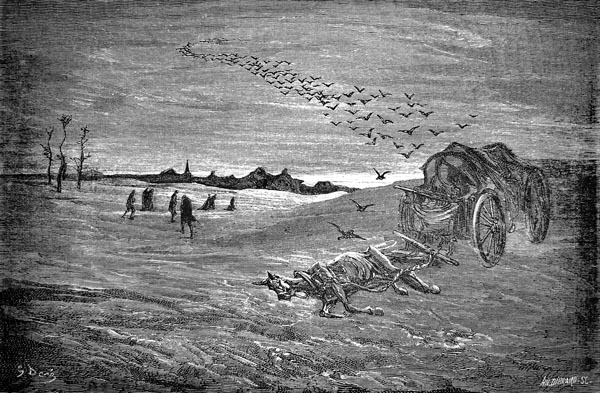

An icy wind had hardened and glazed the snow. The poor old horse advanced with extreme difficulty; on the least slope his hooves slipped, and though he planted his scarred legs like stakes, and tried to sink onto his lean rump, the momentum of the carriage pushed him forward, despite Scapin, who was walking beside him, supporting him by gripping the bridle.

‘The poor old horse advanced with extreme difficulty.’

Despite the cold, streams of sweat trickled over the horse’s gaunt ribs, and down his weak limbs, sweat beaten to a white foam by the friction of the harness. His lungs panted like the bellows of a forge. Vague terror dilated his bluish eyes, which seemed fixed on something spectral before him, and now and then he sought to turn away as if obstructed by some invisible obstacle. His swaying, tottering frame struck against one shaft, then the other. He raised his head, revealing his gums, then lowered it as if he wished to bite at the snow. His hour had come; he was dying though as yet still upright like the brave horse he was. Finally, he fell, and with a weak defensive kick against death, lay on his side, never to rise again.

Frightened by this sudden shock, which almost spilled them to the ground, the women began to cry out in distress. The actors rushed to their aid, and soon freed them. Leonarda and Serafina were uninjured, but the violence of the shock and the fright had caused Isabella to faint, and Sigognac lifted her, unconscious and inert, in his arms, while Scapin, bending, felt the ears of the horse, which lay flat on the ground like a paper cut-out.

— ‘He’s quite dead,’ said Scapin, raising himself again with a discouraged air. ‘The ears have lost their heat, and the pulse in the vein there is no longer beating.’

— ‘We shall be obliged,’ cried Leander piteously, ‘to harness ourselves to ropes, like beasts of burden or sailors hauling a boat, and pull our own cart. Oh! Curse the fancy I pursued of becoming an actor!’

— ‘What a time to moan and lament!’ roared the Tyrant, irritated by this untimely jeremiad, ‘let us instead consider, more manfully, as fellows whom fortune can never confound, what should be done, and firstly let us see if our good Isabella is seriously harmed; but no, here, she is opening her eyes again, and regaining her senses, thanks to the care of Sigognac, and Dame Leonarda. Therefore, let the troupe divide into two parties. One shall remain near the wagon with the women, and the other traverse the countryside in search of help. We cannot like the Russians, accustomed to Scythian frosts, winter here until dawn, our rumps in the snow. We lack the furs for that, and morning would find us crippled, frozen and white with frost, like candied fruit. Come, Captain Fracasse, Leander and you Scapin, who are the lightest, and have swift feet like Achilles the son of Peleus. On your way! Run like lithe cats and find us reinforcements quickly. Blazius and I will stand sentry, meanwhile, beside the luggage.’

The trio, so designated, prepared to leave, though the darkness augured ill for their expedition, for the night was as black as the mouth of an oven, and only the reflected glow from the snow allowed them to find their way; but darkness, though it eclipses objects, reveals any signs of light, and a small reddish star was seen to twinkle at the foot of a hill some considerable distance from the road.

— ‘Here,’ said the Pedant, ‘is the star of our salvation, a terrestrial star as pleasant to lost travellers as the polar star to sailors in periculo maris (‘in danger on the sea’). This star, with its benign rays, is some candle or lamp set beside a window; which supposes a well-sealed and warm room forming part of a house inhabited by human and civilised beings rather than by savage Laestrygonians (man-eating giants in Greek mythology, see Homer’s ‘Odyssey’). Doubtless, there is a bright fire blazing in the chimney, and over this fire a pot in which a rich soup is cooking; oh, pleasant imagining, at which fancy licks its lips, whose thirst I shall quench, in ideal manner, with two or three bottles seized from behind the wood-pile, and draped in ancient style with cobwebs!’

— ‘You ramble, my dear old Blazius,’ said the Tyrant, ‘and the cold, freezing your brain beneath that bald pate, has set mirages flickering before your eyes. However, there is this truth in your delirium, that a light supposes an inhabited house. This alters our plan of campaign. We shall all make for this beacon of salvation. It is hardly likely that thieves will pass tonight on this deserted road to steal our canvas forest, public square, or living room. Let us each take our clothes. The packages are not very heavy. We shall return tomorrow to reclaim the cart. Besides, I am beginning to suffer from cold, and can no longer feel the tip of my nose.’

The actors set off, Isabella leaning on Sigognac’s arm, Leander supporting Serafina, Scapin leading the Duenna and Blazius, with the Tyrant as the vanguard. They cut across the fields, straight towards the light, sometimes obstructed by a bush or a ditch, and sinking into the snow up to their knees.

‘They cut across the fields…’

Finally, after more than one fall, the troupe reached a large walled building, with a carriage door, which seemed to belong to a farm, as far as could be judged through the shadows. Amidst the dark wall, a lamp within illuminated a square frame, containing the panes of a little window whose shutter was not yet closed.

Sensing the approach of strangers, the watchdogs began to stir and raise their cries. They could be heard, in the silence of the night, running, leaping, and fretting behind the wall. Footsteps and human voices mingled with their row. Soon the whole farm was awake.

— ‘Stay there, the rest of you, and keep your distance,’ said the Pedant, ‘our numbers might frighten these good people who could take us for a band of rogues seeking to invade their rustic home. As I am old and have a fatherly and good-natured air, I alone will knock at the door, and begin negotiations. They will not be afraid of me.’

This wise advice was followed. Blazius rapped, with his knuckles, on the door. It opened slightly, then flew wide. From where they were standing, feet in the snow, the actors witnessed an inexplicable, and surprising spectacle. After a few words had been exchanged inaudible to the actors, the Pedant and the farmer, who had raised his lamp to illuminate the face of the man who had disturbed him, began, to gesticulate in a strange manner, and embrace one another, as is customary on recognising a fellow thespian.

Encouraged by this reception, which they scarcely comprehended, but which, based on the warmth of the pantomime, they judged to be cordial and favourable, the actors approached timidly, assuming a pitiful and modest demeanour, as befits travellers in distress seeking hospitality.