Théophile Gautier

Captain Fracasse (Le Capitaine Fracasse)

Part I: Chapters I-V

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Chapter I: The Castle of Melancholy.

- Chapter II: The Chariot of Thespis.

- Chapter III: The Inn of the Blue Sun.

- Chapter IV: Scarecrows for the Birds.

- Chapter V: At the Marquis’ Château.

Translator’s Introduction

Théophile Gautier (1811-1872) was born in Tarbes, in the Hautes-Pyrénées region of south-west France, his family moving to Paris in 1814. He was a friend, at school, of the poet Gérard de Nerval, who introduced him to Victor Hugo. Gautier contributed to various journals, including La Presse, throughout his life, which offered opportunities for travel to various countries, among others Spain, Italy, Russia, Turkey and Egypt. He was a devotee of the ballet, writing a number of scenarios including that of Giselle. At the time of the 1848 Revolution, he expressed strong support for the ideals of the Second Republic, a support which he maintained for the rest of his life.

A successor to the first wave of Romantic writers, including Chateaubriand and Lamartine, he directed the Revue de Paris from 1851 to 1856, worked as a journalist for La Presse and Le Moniteur universel, and in 1856 became editor of L’Artiste, in which he published numerous editorials asserting his anti-utilitarian credo of ‘Art for art’s sake’. Saint-Beuve secured his critical acclaim; he became chairman of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in 1862, and in 1868 was granted the sinecure of librarian to Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, a cousin of Napoleon III, having previously been introduced to her salon.

Gautier remained in Paris during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71, and the aftermath of the 1871 Commune, dying of heart disease at the age of sixty-one in 1872.

Though ostensibly a Romantic poet, Gautier may be seen as a forerunner to, or point of reference for, a number of divergent poetic movements including Symbolism and Modernism.

Le Capitaine Fracasse, an episodic novel written in 1863, has as its protagonist the Baron de Sigognac, an impoverished seventeenth-century nobleman who, in the reign of Louis XIII of France, abandons his château to join a theatrical company so as to pursue a young actress whom he loves. (For members of this comedy troupe, Gautier adopted and adapted characters from the traditional commedia dell’arte.) Sigognac travels with them to Paris, intending to petition the king and seek financial aid in memory of the services rendered to royalty by his ancestors. When one of the actors dies, Sigognac replaces him, taking the stage name of Captain Fracasse (the name derived from the word fracas, a skirmish or commotion), and, despite his innate pride, acting the part of a hapless military man. The experience teaches him humility, and this in turn deepens his relationship with the young actress he adores. The novel illustrates Gautier’s love of the theatrical, whether drama or ballet; his ability to navigate the ranks of his society without fear or favour; his aesthetic and poetic sensibilities; his expert command of language; and the humour, humanity, and tenderness with which he deals with the world, in all his writing.

This enhanced translation has been designed to offer maximum compatibility with current search engines. Among other modifications, the proper names of people and places, and the titles given to works of art, have been fully researched, modernised, and expanded; comments in parentheses have been added here and there to provide a reference, or clarify meaning; and minor typographic or factual errors, for example incorrect attributions and dates, in the original text, have been eliminated from this new translation.

Chapter I: The Castle of Melancholy

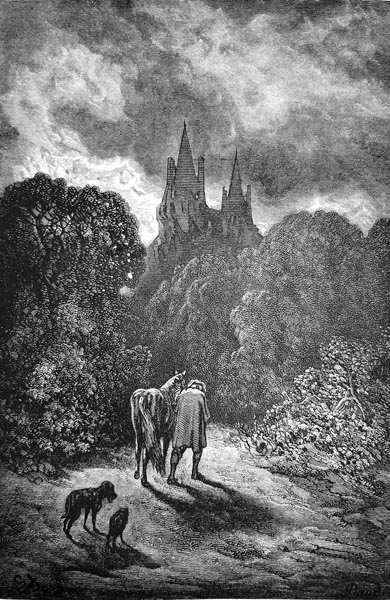

On a slope of one of those barren hills that punctuate Les Landes, between Dax and Mont-de-Marsan, there stood, in the reign of Louis XIII, a manor-house, of the type commonly met with in Gascony, which the local villagers dignified by calling it a château.

Two square towers, topped with sloping four-sided candle-snuffer roofs, occupied the corners of a building the facade of which bore a pair of deeply-cut grooves indicating the former existence of a drawbridge, whose role had been reduced to that of a sinecure due to the filling-in of the moat. The manor-house possessed a somewhat feudal appearance, due to these tall watchtowers, and their conjoined weather vanes. The dark green of a sheet of ivy, half-enveloping one of the towers, contrasted happily with the grey hue of the stone, already ancient at that date.

Any traveller who had seen the castle from afar, its pointed ridges outlined against the sky, high above the broom and heather, might have judged it a suitable dwelling for a provincial squire; but, on approaching, their opinion would certainly have altered The path which led from the road to the château had been reduced, through the invasion of moss and parasitic vegetation, to a pale, narrow track, like tarnished braid on a threadbare coat. Two ruts filled with rainwater, inhabited by frogs, testified that carriages had once passed that way; but the complacency of those amphibians indicated a long period of possession combined with the certainty of remaining undisturbed. On the central strip bordered by straggling grasses, and soaked by a recent downpour, there was not a human footprint to be seen, and the scrub, burdened with gleaming drops of water, appeared not to have been cleared for many a long day.

Large leprous-yellow patches mottled the browned, disordered tiles of the roofs, whose rafters had rotted and given way in places; rust prevented the weather-vanes from turning, and thereby indicating a change in the wind’s direction; the dormer windows were blocked by shutters of warped and split wood. Rubble filled the barbicans of the towers, and of the half-score of windows of the facade, eight were barred by planks, while the other two displayed bombé glass panes, trembling at the slightest breath of the north wind amidst their network of lead. Between these windows, the plaster, fallen in flakes like scales of diseased skin, exposed disjointed bricks, and rubble-stone crumbling due to the pernicious influence of the moon. The doorway, framed by a stone lintel, whose roughened surface bore traces of ancient ornamentation blunted by time and neglect, was surmounted by a crude coat of arms that the most skilled herald would have been powerless to decipher, and whose mantling was fancifully convoluted, and not without numerous breaks, damaging to its continuity. The door panels still offered, towards the top, remnants of oxblood paint, and seemed to blush, ashamed of their state of disrepair; diamond-headed nails held their cracked boards together, and formed incomplete symmetries here and there. One of the door’s two leaves could be opened, and was sufficient for the passage of guests visiting the castle, evidently few in number, while against the jamb of the closed leaf rested a decayed wheel, now falling to pieces, the last remnant of a carriage that had perished during the previous reign. Swallows’ nests obscured the chimney-tops, and the corners of the windows, and, if it had not been for a thin wisp of pale smoke issuing from one of the brick chimneys, and twisting spirally like the chimney-smoke in those attempts at houses that schoolchildren scribble in the margins of their schoolbooks, one might have thought the house uninhabited: the cookery that was being performed in the depths below must have been meagre, since a soldier’s pipe would have produced denser fumes. This smoke was the only sign of life that the house gave, like those at death’s door whose continued life is revealed only by the mist produced by their breath.

If one pushed past the movable leaf of the door, which only yielded under protest, and turned with evident displeasure on its rusty and screeching hinges, one found oneself beneath a kind of ogival vault, older than the rest of the dwelling. It was supported on four bluish, sausage-like granite ribs arching to a projecting keystone on which one could see once more, only a little less worn, the coat of arms sculpted on the outer lintel, consisting of three storks in gold, on an azure field, or some such emblematic creatures since the shadow beneath the vault prevented one distinguishing them clearly. Sealed into the wall, were sheet-metal torch extinguishers, blackened by use, and iron rings to which the visitors’ horses were once tethered, now a very rare occurrence judging by the dust that coated them.

Exiting this porch, beneath which were two doorways, one leading to the apartments on the ground floor, the other to a room which might formerly have served as a guardroom, one emerged into a sad, bare, chilly courtyard, surrounded by high walls which were marked by long black stains from the rains of many a winter. In the corners of this courtyard, amidst rubble fallen from the broken cornices, grew nettles, wild-oats, and hemlock, while the interstices of the paving stones were filled with weeds.

At the far end, a ramp, flanked by stone railings adorned with stone orbs topped by spikes, led to a garden below the courtyard. The broken and dilapidated steps shifted underfoot or, if held in place, it was only by filaments of moss, and the roots of plants; and between the supports of the terrace sempervivums, wallflowers, and wild artichokes had grown.

As for the garden itself, it was slowly returning to a state akin to a woodland thicket or even, in places, virgin forest. With the exception of a square, where a few cabbages with veined, verdigrised leaves and starred by golden suns with black hearts were clustered, whose presence testified to some degree of cultivation, Nature was reclaiming her rights over that abandoned space, and erasing the traces of human activity whose vanishing she ever seems to delight in.

The unpruned trees had thrown forth eager branches in all directions. The boxwood hedges, intended to mark the outlines of borders and paths, had become bushes, having not been pruned for many years. Seeds, carried by the wind, had sprouted at random, and were growing with that perennial robustness peculiar to weeds, in beds once occupied by pretty flowers and rare plants. Brambles with thorny spurs arched from one edge of the various paths to the other, and hooked you as you passed, to prevent you from going further, and to hide from you this mysterious place of sadness and desolation. Solitude dislikes being surprised in a state of undress, and creates all sorts of defensive barriers around itself.

Yet, if one had persisted, without fearing the scratches delivered by the brushwood, or blows dealt by the branches, in following the ancient path to its end, a path which had become more obstructed and overgrown than a path in the woods, one would have arrived at a kind of rocky niche representing a rustic cavern. To the plants formerly sown in the stony interstices, such as irises, gladioli, and black-ivy, others had been added, persicaria, hart’s tongue ferns, and wild vines, which hung down like beards half-veiling a marble statue representing some mythological divinity, Flora or Pomona, who must have been very charming in her time and brought honour to the sculptor, but due to attrition was nose-less, like Medieval depictions of Death. The poor goddess carried in her basket, instead of flowers, mouldy and poisonous-looking mushrooms; she seemed to have been poisoned herself, patches of brown moss marking her once white body. At her feet, beneath a layer of green duckweed, a brown puddle, the residue of the rain, stagnated in a stone shell, since the lion’s mask above, which could still be partially discerned, no longer vomited water, receiving none from the blocked or vanished channels.

This grotesque ‘cabinet’, as it was then called, testified, ruined though it was, to a certain love of ease and taste for the arts, on the part of the former owners of the castle. Suitably cleaned and restored, the statue would have revealed the style of the Florentine Renaissance, executed in the manner of those Italian sculptors who came to France in the wake of ‘Il Rosso’ (Giovanni Battista di Jacopo, 1495–1540) or Francesco Primaticcio (1504-1570), such being the probable period when the now fallen family had flourished in splendour.

The cavern had been constructed adjoining a green, saltpeter-covered wall, erected at the time of the cavern’s construction, which was still crisscrossed by fragments of broken trelliswork, no doubt intended to hide the wall’s surface beneath a curtain of leafy climbing plants. This wall, barely visible through the disordered foliage of now enormous trees, bordered the garden on the inner side. Beyond stretched the moor, its melancholy bareness dotted with heather.

Returning to the castle, the facade opposite that just described, when viewed, appeared even more ravaged and eroded than the latter, the later owners having tried to keep up appearances by concentrating their limited resources on the side previously described.

In the stable, where twenty horses could have been stabled at ease, a lean Breton pony, whose rump jutted forth in bony protuberances, was pulling a few strands of straw from an empty rack with the tips of his loose yellowed teeth, and from time to time turning toward the door an eye set in a socket within whose depths the rats of Montfaucon (where the main gallows and gibbet of the Kings of France were sited, in Paris, until the time of Louis XIII) would not have found the slightest morsel of fat. At the threshold of a kennel, a lone dog slumbered, draped in overly-loose skin beneath which his relaxed muscles were outlined in flaccid lines, his muzzle resting on the meagrely padded pillows of his front paws; he seemed so accustomed to the solitude of the place that he had renounced all pretence of guarding it, and showed no sign of alarm, as dogs, even when drowsy, are wont to do, at the slightest noise they hear.

If one chose to enter the dwelling, one encountered an enormous staircase with a wooden banister and carved balusters. This staircase had only two landings, the building containing no more than two floors. It was constructed of stone up to the first floor, and of bricks and wood from there onwards. On the walls, grisailles partially devoured by humidity had at one time sought to imitate the relief-work of richly-decorated architecture, through the use of chiaroscuro and perspective. One could still divine a series of panels portraying the Labours of Hercules, topped by a moulding, beneath a cornice supported by modillions (projecting brackets) from which arched a bower of foliage festooned with vine branches, revealing a sky, faded in colour, and divided into curious islands by the infiltration of rainwater. Between the Hercules’ panels, busts of Roman emperors and other illustrious figures from history were painted, in niches; but all was so vague, faded, ruined, or obliterated, that it was rather the ghost of art than art itself, that could be seen, and one would need to describe it with the shadows of words, ordinary words themselves being too substantial to convey its state. The echoes in this empty space seemed quite surprised at repeating the sound of footsteps.

A green door, whose serge had yellowed, and was held together only by a few gilded nails, led into a room that might have served as a dining room, in the fabled days when people indeed dined in this deserted dwelling. A large beam divided the ceiling into two compartments lined with exposed joists, the interstices of which had once been covered with a layer of blue, now obliterated by dust and cobwebs, which no brush would ever disturb at that height. Above the fireplace, ancient in form, a ten-tined stag’s head spread its antlers, and along the walls on darkened canvases smoky portraits representing armoured military captains grimaced, their helmets beside them or held by a page, and gazed at one from profoundly black eyes, the only features seemingly alive in the dead faces of those lords in velvet jackets, their heads supported by stiff starched ruffs, each rather like the head of Saint John the Baptist on the silver platter; or they showed dowagers in old-fashioned costumes, terrifying in their lividity and taking on, through the decomposition of the colours, the appearance of Striges, Lamias and Empusai. These paintings, executed by provincial daubers, presented, due to the very barbarity of the work, a heterogeneous and formidable appearance. Some lacked frames; others had borders of tarnished and reddened gold. All bore at their corners the family crest and age of the person represented; but whether the number of years was low or high, there was no appreciable difference between these different heads with their yellowing hues, and dark charred shadows, smoky with varnish, and sprinkled with dust. The colour tones of two or three of these canvases, faded and covered with a flowering of mould, were those of a rotting corpse, and proved that the last descendant of these men of lineage and military prowess, was wholly indifferent to the effigies of his noble ancestors. At eve, this silent and motionless array was doubtless transformed, in the wavering light of the lamps, to a gallery of ghosts, at the same time both terrifying and ridiculous. Nothing is sadder than such forgotten portraits in deserted rooms; half-erased versions of forms long since vanished below the ground.

As it was, those painted ghosts seemed fitting guests to adorn the desolate solitude of the dwelling. Real inhabitants would have seemed far too alive for that dead house.

In the centre of the room stood a table of blackened pear-wood, its legs carved in spirals like Solomonic columns, which woodworms, undisturbed in their silent work, had pricked with a myriad of holes. A thin grey layer, on which the finger could have traced a message, covered its surface, and showed that the table was not often set for diners.

Two sideboards or credenzas in the same wood, decorated with carvings and probably purchased along with the table in happier times, were placed on either side of the room; chipped earthenware, disparate pierces of glassware and two or three rustic figurines, by the potter Bernard Palissy, representing eels, fish, crabs and shells, enamelled on a background of greenery, occupied the otherwise empty shelves.

Five or six chairs covered in velvet that might once have been crimson, but which years and use had rendered a yellowish red, allowed their stuffing to escape through gaps in the fabric, and limped on disparate feet like halting iambic verse, or crippled soldiers returning home after a war. Unless one were a mere spirit, it would have been imprudent to sit there, and, no doubt, those seats were only used when the host of ancestors, having quit their picture-frames, came to sit at the empty table and, over an illusory supper, chatted among themselves, during those long wintry nights so suited to ghostly feasts, regarding the family’s decay.

From this room one entered another, slightly smaller, one. A Flemish tapestry, one of those termed ‘Verdures’ (depicting verdant wooded landscapes) adorned the walls. Let not the word ‘tapestry’ awaken in your imagination the idea of inappropriate luxury. This one was worn, threadbare, and faded; hundreds of loose threads, in coming unwoven, had permitted gaps in the fabric, and the fragments were held together only by a few remaining threads, and longstanding habit. Their discoloured representations of trees were yellowish on one side and bluish on the other. The heron, standing on one leg among the reeds, had suffered considerably from moth damage. The Flemish farm, its wellhead festooned with hops, was almost indistinguishable and of the pale face of the hunter in pursuit of wild duck his scarlet mouth and dark eyes, their dyes apparently more resistant than the rest, had alone retained their original colouring, so that he looked like a corpse, of waxen pallor, whose mouth had been vermilioned and whose eyebrows had been highlighted. Currents of air played between the surface of the wall and the loose fabric, endowing it with curious undulations. Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, if he had been soliloquising there, would doubtless have drawn his sword and poked at Polonius, concealed behind the arras, while crying: ‘A rat! A rat!’ (See Act 3, scene 4 of Shakespeare’s play) A thousand little noises, almost-imperceptible whispers, in the room, rendering the silence more tangible, disturbed the ears and thoughts of any visitor bold enough to penetrate there. The mice nibbled hungrily at some strands of wool on the underside of the fabric which had been woven on a low-warp (horizontal) loom. Woodworms rasped at the beams producing a dull noise like a file in use, and the fell hand of death struck the hour, with clockwork precision, against the wall-panels.

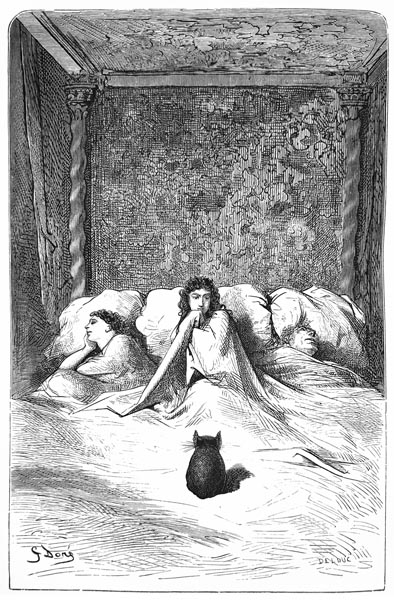

Sometimes a piece of furniture would creak unexpectedly, as if ennui, engendered by solitude, were stretching its joints, causing one, despite oneself, to shudder nervously. A four-poster bed with conical pillars, enclosed by brocatelle-fabric curtains open at every fold, whose green and white pattern had merged to a single yellowish tint, occupied a corner of the room, nor would one have dared to raise the hangings for fear of revealing, in the shadows, some crouching monster, or a stiff form outlined beneath the white sheets, with a pointed nose, bony cheekbones, clasped hands, and conjoined feet, like the feet of those commemorative statues adorning tombs, so swiftly do things made by human beings, and from which humanity is absent, take on a supernatural air! One might even have supposed that some innocent young princess, laid under a spell, was resting there in centuries-old slumber, like Sleeping Beauty, though the folds had too sinister a rigidity and seemed too mysterious for that, dispelling all ideas of Romance.

A black wooden table with a loosened copper inlay; a vague and cloudy mirror whose silver had blackened, weary of not reflecting a human figure; and an armchair its fabric worked in needlepoint, leisure’s patient labour brought to completion by some grandmother or other, but in which nothing but a few silver threads could be discerned amidst the faded silk and wool, completed the furnishings of this room, habitable only for a person who feared neither spirits nor ghosts.

These two rooms corresponded to the two unblocked windows of the facade. A pale, greenish light streamed through the frosted panes, which had last been cleaned a good hundred years ago, and which seemed tinted on the outside. Ample curtains, rumpled where they joined, and which would have been torn apart if anyone had tried to slide them along their rust-eaten rods, further diminished the dim light, adding to the melancholy of the place.

On opening the door at the end of the second room, one was plunged into complete darkness, entering a void, strange and obscure. Little by little, however, the eye became accustomed to the shadows, crossed by a few livid shafts of light filtering through the joints of the boards blocking the windows, and one discovered a confusing series of dilapidated rooms, with uneven parquet floors, strewn with broken panes of glass, their bare walls half-covered by a few shreds of frayed wallpaper, their ceilings revealing the rafters, and allowing water to drip from the sky above, admirably arranged for a horde of rats, and colonies of bats. In some places, it would not have been safe to advance, since the floor undulated and bent beneath one’s feet, though no one ever ventured into this Thebaid (desert) of shadow, dust and cobwebs. Standing at the threshold, a lingering odour, a scent of mould and abandonment, and the damp, black chill peculiar to dark places, rose to your nostrils as if one had lifted the stone sealing a vault, and leant into its icy darkness. Indeed, it was the corpse of the past that was slowly collapsing to dust in these rooms, in which the present never set foot; the silent years that rocked themselves, as if in hammocks, in the grey canvases occupying their corners.

Above, in the attics, barn owls and tawny owls roosted during the day, and jackdaws with their feathery ears, cat-like heads, and round phosphorescent eyes. The roof, collapsing in twenty places, allowed those amiable birds to come and go freely, they being as at-ease there as in the ruins of Montlhéry (in the Île-de-France) or Château Gaillard (in Normandy). Every evening, the dusty occupants flew forth, uttering those clamorous cries that trouble superstitious folk, to seek far-off the nourishment absent from their barren tower.

The ground-floor rooms contained nothing but a half-dozen bales of straw, corn-stalks, and a few gardening implements. In one of these rooms lay a straw mattress filled with dry heads of Turkish wheat and cloaked by a rough woollen coverlet, which appeared to constitute the bed of the only servant in the manor house.

Since my reader may have been wearied by this tour amidst solitude, misery and abandonment, let me take him or her to the only room in the deserted castle that possessed any life, that is the kitchen, whose chimney emitted to the sky that pale, whitish cloud mentioned in the external description of the castle.

A meagre fire licked the chimney-back, with yellow tongues of flame, and from time to time reached the bottom of a cast-iron pot with a handle, that hung from the iron rack, while faint reflections illuminated with their reddish gleams the rims of a few saucepans attached to the wall, amidst the shadows. Daylight falling through the large chimney-pipe with reached the roof unbendingly, highlighted the ashes with bluish tints, and made the fire appear paler, thus, in that cold hearth, the very flames seemed frozen. Without the precaution of its cover the pot would have filled with rainwater, and storms diluted the broth.

The water, slow to heat, finally began to boil, and the kettle complained in a low tone, like an asthmatic person: a few cabbage-leaves simmering, indicated that the still-cultivated portion of the garden had been used for this more than Spartan broth.

A scrawny old black cat, as threadbare as a worn-out muff, the missing fur revealing bluish skin in places, was seated on its rump, as close to the fire as possible without its whiskers burning, and stared at the pot, the pupils of its green eyes as narrow as a letter I, with an air of interested surveillance. Its ears had been cropped close to its head, and its tail close to its spine, which gave it the appearance of those Japanese monsters that are placed in cabinets among other curiosities, or even of those fantastic creatures whom witches, off to their Sabbath, entrust with the task of tending the cauldron in which their potions are seething.

This cat, all alone in the kitchen, appeared to be cooking soup for himself, and doubtless it was he who had set out, on the oak table, a plate decorated in green and red, a pewter goblet, presumably polished with his claws as it was so scratched, and a stoneware pot on the sides of which the coats of arms seen in the porch, on the keystone, and adorning the portraits, was roughly drawn in blue.

Who would seat themselves at this modest meal, in this manor without inhabitants; perhaps the familiar spirit of the house, the genius loci (the spirit of the place), the Kobold (the household spirit, ‘hausgeist’) faithful to its adopted home, while the black cat, with the profoundly mysterious gaze, was waiting for its arrival to serve the soup, napkin on paw.

The pot boiled away; the cat remained motionless at its post, like a sentry whose relief had been neglected. At last, a heavy and ponderous footstep was heard, that of an old person; a short preliminary cough sounded, the door latch creaked, and a man, half-peasant, half-servant, entered the kitchen.

At the appearance of the newcomer, the black cat, which seemed a long-time friend of the man, left the hearth and the glowing ashes, and rubbed itself amicably against his legs, arching its back, opening and closing its claws, and emitting from its throat that hoarse murmur which indicates the highest level of satisfaction amongst the feline race.

‘Well, well, Beelzebub,’ said the old man, bending down to pass a calloused hand twice or thrice over the cat’s hairless back, so as not to be outdone in politeness by an animal: ‘I know that you love me, and we are solitary enough here, my poor master and I, not to disparage the caresses of a creature lacking a soul, but which nevertheless seems to understand us.’

These mutual courtesies completed, the cat began to walk away from him, leading him towards the fireplace, as if to direct him to the pot, which it was looking at with the most touching air of eager covetousness in the world, for Beelzebub was beginning to grow old, his hearing was less acute, his eyesight less sharp, his paw less nimble than before, and the resource that hunting birds and mice had formerly provided was noticeably diminished; therefore, he kept an eye on the soup, of which he hoped to receive a share, and which caused him lick his lips in anticipation.

Pierre, for that was the old servant’s name, took a bundle of twigs, and threw them onto the half-dead fire; they crackled and contorted, and soon a flame, preceded by a billow of smoke, rose bright and clear amidst a joyous fusillade of sparks. It seemed as if the salamanders of legend were frolicking and dancing in the flames. A poor pulmonic cricket, delighted with the warmth and brightness, even tried to chirp by rubbing its wings together, but only managed to produce a wheezing sound.

Pierre, draped in an old piece of green serge, with a toothed border, and yellowed by smoke, sat down on a wooden stool before the hearth, with Beelzebub beside him.

The glow of the fire illuminated his features, which age, sunlight, fresh air, and the inclemency of the seasons had smoked, so to speak, till they were darker than those of a native of the Caribbean; a few strands of white hair, escaping from his blue beret and plastered to his temples, further enhanced the brick tones of his swarthy complexion; his black eyebrows provided a contrast with his snowy hair. Like others of the Basque nation, he had an elongated face, and a nose like the beak of a bird of prey. Large vertical wrinkles, like sabre cuts, furrowed his cheeks from top to bottom.

A sort of livery with faded braid, and of a colour that a professional painter would have found difficulty in defining, half-covered his chamois jacket, rendered shiny and black in places due to the friction produced by a breastplate, producing on its yellow surface tints like those that render green the belly of a well-hung partridge; for Pierre had been a soldier, and some remnants of his military gear were now visible in his civilian attire. His narrow breeches revealed the warp and weft of a material as light as embroidery canvas, and it was impossible to know whether they had been made of broadcloth, ratteen, or serge. All texture had long since disappeared from these worn breeches; never was a eunuch’s chin more hairless. Noticeable patches, added by a hand more accustomed to holding a sword than a needle, which had addressed their weak points, testified to the care taken by the garment’s owner to extend its longevity to the furthest point. Like Nestor, these ancient breeches had lived three ordinary lifetimes. It is a strong probability that they were once red, but that vital fact is not absolutely proven.

Rope-soled shoes, which recalled Spanish alpargatas (espadrilles), attached with blue-cord to woollen stockings from which the foot had been removed, served as Pierre’s footwear. These coarse buskins had doubtless been chosen as being more economical than court shoes or drawbridge shoes (solid shoes with a gap between the heel and the sole), since a strict, sober, and honest poverty was betrayed in the smallest details of the old man’s appearance and even in his pose of gloomy resignation. Sitting with his back against the inner side wall of the chimney, he crossed his large hands, reddened to purplish tones like vine leaves in late autumn, over his knees, so forming a motionless counterpart to the cat, Beelzebub, crouched in the ashes opposite him, with a famished and pitiful air, and gazing with profound attention at the asthmatic bubbling of the cooking pot.

‘The young master is very late today,’ murmured Pierre as, through the smoky, yellow panes of the only window that lit the kitchen, he watched the last streak of sunlight fade and diminish at the edge of a sky marked by heavy, rain-filled clouds. ‘What pleasure does he find walking alone on the moor this way? Though it’s true this castle is so sad nowhere else could inspire a greater feeling of tedium.’

A hoarse but joyous barking was now heard; the pony, in the stable, stamped the ground, making the chain that tethered it to the side of its manger rattle; the black cat interrupted its grooming by passing a paw, moist with saliva, over its face, and cropped ears, and stepped towards the door in the manner of a polite and affectionate creature that knows its duty and conforms to it.

The door opened; Pierre rose, respectfully removing his beret as the newcomer appeared in the room, preceded by the old dog we have already mentioned, who attempted to leap up but fell back heavily, weighed down by age. Beelzebub declined to treat the dog, Miraut, with the antipathy that his peers usually profess for canines. On the contrary, he looked at him in a very friendly manner, rolling his green eyes, and arching his back. It was clear that they had known each other for a long time and often kept each other company amidst the solitude of the castle.

The Baron de Sigognac, for it was the young lord of the dilapidated mansion who had just entered the kitchen, was a young man of twenty-five or twenty-six, although at first glance one might have thought him older, so grave and serious did he appear. The feeling of impotence, which accompanies poverty, had made all gaiety flee his features and the bloom of spring, which smooths young faces, fade. Bistre-coloured halos already encircled his bruised eyes, and his hollow cheeks strongly accentuated the prominence of his cheekbones; his mustachios, instead of being cheerfully pointed, drooped a little, and seemed to weep sadly beside his mouth; his hair, combed without due care, hung in black locks around his pale face, with an absence of coquetry rare in a young man who might have passed for handsome, and showing an absolute renunciation of any thought of pleasing. His habit of nursing a secret sorrow had caused sharp lines to mar a countenance which a modicum of happiness would have rendered charming, and the resolution natural to his years, seemed to have yielded before some misfortune countered in vain.

Although agile, and of a constitution rather robust than weak, the young baron moved with the apathetic sluggishness of one who had relinquished life. His gestures were feeble and somnolent, his countenance inert, and one saw that he was perfectly indifferent as to whether he was here or there, abroad or at home.

His head was covered with an old greyish felt hat, dented and torn, and much too broad, which sloped down almost to his eyebrows, forcing him to raise his nose in order to see clearly. A feather, whose sparse barbs gave it the appearance of a fishbone, was attached to the hat, and was obviously intended to act as a plume, but drooped behind limply as if ashamed of itself. A collar of antique guipure lace, not all of whose shape was due to the skill of its creator, and to which years had added more than one feature, lay flat against his jerkin, the loose folds of which announced that it had been tailored for a man taller, and more ample in form, than the slender baron. The sleeves of his doublet hid his hands like the sleeves of a monk’s robe, and he was plunged almost to his thighs in ‘cauldron’ boots (also termed ‘court’ boots, the knee piece flared in the shape of a funnel or cauldron) equipped with iron spurs. This motley wear was that of his late father, who had been dead for some years, and whose clothes, already ripe for the second-hand clothes dealer at the time of the death of their previous owner, he was wearing to their end. Dressed thus, in garments fashionable perhaps at the beginning of the previous reign, the young baron looked at once ridiculous and touching; one might have taken him for his own grandfather. Though he professed for the memory of his father a completely filial veneration, and tears often came to his eyes when he donned these dear relics which seemed to preserve in their folds the gestures and attitudes of the deceased gentleman, it was not exactly out of preference that young Sigognac adorned himself with the contents of his father’s wardrobe. He had no other clothes, and had been pleased to disinter this portion of his inheritance from the depths of a trunk. The garments from his adolescent years no longer fitted. At least, in his father’s clothes, he was comfortable. The local villagers, accustomed to seeing a doublet on the old baron’s shoulders, judged it no more ridiculous on the son’s back, and greeted it with the same reverence and deference; they no more noticed the rents in that doublet than the cracks in the castle walls. Sigognac, poor as he was, was still their lord in their eyes, and the decline of the family did not strike them as forcibly as it might have struck a stranger; and yet it was a somewhat grotesque and melancholy spectacle seeing the young baron pass by in his old clothes, on his aged horse, accompanied by his aged dog, like the knight in Albrecht Durer’s engraving (‘Knight, Death, and the Devil’, 1513).

The Baron seated himself, silently, at the table, after responding with a kindly gesture of the hand to Pierre's respectful greeting. The latter detached the cooking-pot from its rack and poured the contents onto a piece of bread he had already placed in the common earthenware bowl which he set before the Baron; it was the everyday soup still eaten in Gascony, under the name of ‘garbure’ (combining slow-cooked vegetables of all kinds with preserved meats); then he took from the cupboard a block of ‘miasson’ (thick cornmeal pancake, baked in the oven) quivering on a napkin, sprinkled it with a little corn-flour and brought it to the table on the board that supported it. This local dish with the ‘garbure’ and a piece of purloined bacon, once doubtless the bait of a mousetrap, formed, in all its meagreness, the Baron’s frugal meal. The latter ate with a distracted air, Miraut and Beelzebub on either side, both eagerly raising their muzzles in the air on each side of his chair, hoping for some crumbs from the ‘feast’ to fall to them. From time to time the Baron threw a mouthful of bread, whose close proximity to the slice of bacon had granted it at least the aroma of meat, to Miraut, who did not let the piece reach the ground. The crust fell to the black cat, whose satisfaction was expressed by a low growl, and a paw extended, claws out, as if ready to defend its prey.

His frugal repast over, the Baron seemed to yield to painful thoughts, or at least to a distraction whose subject was far from pleasant. Miraut laid his head on his master’s knee and fixed on him eyes that age had clouded with a bluish veil, yet in which a spark of almost human intelligence nonetheless flickered. One would have said that he understood the Baron’s thoughts and wished to show his sympathy. Beelzebub, the cat, made his purring noise, much like the hum of a spinning wheel turning as loudly as that of ‘Bertha the Spinner’ (Bertha of Swabia, also known as La Filandière or La Reine Fileuse, twice Queen of Italy in the 10th century), and he uttered little plaintive cries to attract the Baron’s fleeting attention. Pierre stood some distance apart, as motionless as those long, stiff, granite statues one sees on the porches of cathedrals, respecting his master’s reverie, and awaiting his command.

Meanwhile, night had fallen, and great shadows filled the corners of the kitchen, like giant bats clinging to the walls with fingers cloaked in membranous wings. A remnant of fire, fanned by the gusts of wind blowing down the chimney and into the fireplace, coloured with strange reflections the group gathered around the table in a sort of sad intimacy that further emphasised the castle’s melancholy solitude. Of the once powerful and wealthy family, only this single isolated offspring remained, wandering like a shade about the manor peopled by his ancestors; of the large household, only this one devoted and irreplaceable servant was left; of the pack of thirty hounds, only the one dog survived, almost blind and grey with age, while the lone black cat served as the soul of the deserted dwelling.

The Baron signalled to Pierre that he wished to withdraw.

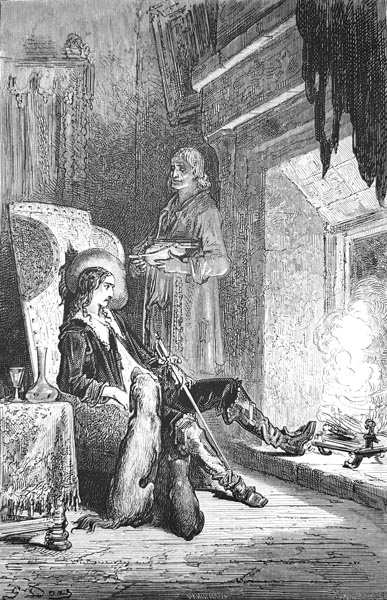

‘His frugal repast over, the Baron seemed to yield to painful thoughts’

Pierre, stooping to the hearth, lit a length of pine wood coated with resin, a kind of economical candle used by the poor, and preceded the young lord; Miraut and Beelzebub joined the procession: the smoky glow of the torch made the faded frescoes on the walls of the staircase flicker, giving an appearance of life to the smoky portraits in the dining room whose black, fixed gaze seemed to cast a pained look of pity on their descendant.

Arriving at the curious bedroom I described previously, the old servant lit a small copper lamp with a nozzle, whose wick was folded in the oil like a tapeworm steeped in alcohol in an apothecary’s timepiece, and withdrew, followed by Miraut. Beelzebub, who savoured his grand entrances, settled himself in one of the two armchairs. The Baron collapsed in the other, overcome by solitude, idleness, and ennui.

If his chamber looked like a roomful of ghosts during the day, it appeared even worse at night, in the wavering light of the lamp. The tapestry took on livid tones, and the huntsman, against a background of dark vegetation, seemed, illuminated thus, almost real. With his arquebus at the ready, he resembled an assassin waiting for his victim, and his red lips were highlighted even more strangely in his pale face. His mouth looked like that of a vampire flushed with blood.

In the damp atmosphere, the lamp gave off a crackling sound, and threw forth intermittent gleams; the wind caused the corridors to give out organ-like sighs; while frightening and unusual noises were heard issuing from the rooms.

The weather had worsened, and large drops of rain, driven on gusts of wind, tinkled against the panes of glass and rattled them in their networks of lead. Sometimes the glass seemed about to bend, and part from its frame, beneath the pressure from outside. It was as if the storm was leaning against the frail obstacle. Sometimes, to add a further note to the strange harmony, one of the owls, nesting beneath the roof, would utter a cry like that of a child whose throat was being cut, or, troubled by the light, would fly down to strike the window with slowly beating wings.

The lord of this sad manor, accustomed to such gloomy symphonies, paid no attention. Beelzebub alone, with the anxiety natural to members of his species, stirred the roots of his cropped ears at every noise and stared fixedly into the dark corners, as if he had perceived, by employing his scotopic vision, something invisible to the human eye. This far-seeing cat, with his diabolical name and manner, would have alarmed a less brave person than the Baron; for the creature seemed to know many things learned in his nocturnal wanderings through the attics and uninhabited rooms of the castle; more than once, at the end of a corridor, he must have encountered that which might turn a person’s hair white.

Sigognac took from the table a small volume whose tarnished binding bore the stamped crest of his family, and began to turn the leaves with an indifferent finger. Though his eyes followed the lines exactly, his mind was elsewhere, or showed only a mediocre interest in Ronsard’s short odes (odelets) and love sonnets, despite their lovely rhymes, and their ideas acquired from the Greeks. It was not long before he set the book down, and began to unbutton his doublet slowly, like a man who has no desire for sleep but, weary of war, lies down because he knows not what else to do, and seeks to drown his boredom in slumber. The grains of sand in the hourglass fall slowly and sadly on a dark, rainy night in the depths of a ruined castle, surrounded by a sea of heather, and bare of a single living being for ten leagues about!

The young Baron, now the sole survivor of the Sigognac family, had, indeed, many reasons for melancholy. His ancestors had ruined themselves in various ways, whether through gambling, warfare, or the vain desire to shine amongst their peers, such that each generation had bequeathed an increasingly diminished heritage to the next.

The fiefs, farms, tenant-farms, and land that belonged to the castle had vanished item by item; and the previous Baron de Sigognac, after incredible efforts to restore the family fortune, efforts without result because it is ever too late to repair the leaks in a sinking ship, had left to his son only the castle in disrepair, and the few acres of sterile land that surrounded it; the rest had to be abandoned to his creditors.

Poverty had thus cradled the young child in its thin hands, and he had suckled at a withered breast. Deprived, while yet very young of his mother who had died of melancholy in that dilapidated castle, thinking on the misery that would later weigh on her son and prevent him winning a career, he had lacked the sweet caresses and tender care with which youth is surrounded, even in the least happy of families. The solicitude of his father, whose absence he nonetheless regretted, had hardly translated into anything more than a few kicks in the rear, or the order that the whip be applied to it. Now, he was so filled with ennui that he would have been happy to receive one of those paternal admonitions whose memory brought tears to his eyes; for a kick dealt by the father to the son still represents a human relationship of a kind, and, during four years that the old Baron had lain outstretched beneath his flagstone in the Sigognac family vault, his son had lived in the midst of a profound solitude. His youthful pride rendered him reluctant to appear among the nobility of the province, at festivals or hunts, without the equipage appropriate to his status.

What would they have said, indeed, on seeing the Baron de Sigognac dressed like a beggar at the door, or like an apple-picker from Le Perche (in Normandy, famed for its orchards and cider)? This consideration had prevented him from offering his services as a servant to some prince. Many were those who believed that the line of the Sigognacs was extinct, and oblivion, which hides the dead even more swiftly than the grass, had erased this once important and wealthy family, while pitifully few were those who knew of the existence of a last descendant of that diminished race.

For some moments, Beelzebub had seemed restless; he raised his head as if he suspected some disturbance; he stood against the window, pressing his paws against the panes, trying to pierce the sombre black of the night streaked with an impressed hatching of raindrops; his nose wrinkled and twitched. A prolonged howl from Miraut, amidst the silence soon endorsed the cat’s pantomime; something unusual was definitely happening in the vicinity of this castle, usually so quiet. Miraut continued to bark with all the energy that chronic hoarseness allowed him. The Baron, to be ready for any eventuality, buttoned the doublet he had been about to doff and rose to his feet.

‘What’s driving Miraut to make such a racket, he who as soon as the sun sets ever snores like the Seven Sleepers’ dog, midst the straw in his kennel? Could a wolf be prowling near the walls?’ said the young man to himself, girding on a broad iron sword which he detached from the wall, and buckling the belt at its innermost hole, since the leather cut to fit the old baron’s waist would have gone twice round that of the son.

Three violent knocks on the castle door sounded at measured intervals, making the empty rooms echo. Who could it be at this hour who disturbed the manor’s solitude and the nocturnal silence? What unwise traveller now knocked at a door which had not been opened for a guest for so long a period of time, though not through lack of courtesy on the part of the master, but merely because of the absence of visitors? Who sought to be received in this inn of starvation, this plenary courtyard of Lent, this hotel of misery and poverty?

Chapter II: The Chariot of Thespis

Sigognac descended the stairs, employing his hand to protect his lamp against the drafts that threatened to extinguish it. The light of the flame penetrated his thin phalanges, and coloured them a diaphanous red, so that, although it was night and he was followed by a black cat instead of himself preceding the sun, he deserved the epithet applied by the good Homer to the hands of Dawn (‘rosy-fingered’).

He lowered the bar at the door, half-opened the movable leaf, and found himself facing a personage, to whose nose he held his lamp. Illuminated by its rays, a somewhat grotesque figure was highlighted against the shadowy background without: amidst the rain, a skull the colour of rancid butter gleamed in the light. Grey hair plastered to the temples; a nose crimson as September wine (traditionally a strong, well-aged, red), and adorned with small buboes, which flowered on the bulbous heights, between two small odd-shaped eyes covered with very thick and strangely black eyebrows; flabby cheeks, marked by winey tones, and crossed with reddened veins; the swollen lips of a drunkard and satyr; and a chin decked out with a wart in which were implanted a few rough, harsh hairs like those on a clothes-brush, composed a physiognomy wholly worthy of those sculpted faces beneath the cornice of the Pont-Neuf in Paris. A certain look of witty bonhomie tempered a visage that might have appeared uninviting at first glance. The creases at the corners of the eyes and the lips directed towards the ears indicated the makings of a gracious smile. This head of a marionette, set on a ruff of equivocal whiteness, surmounted a body in a loose black smock, that bowed in an arc with an exaggerated affectation of politeness.

The salutations accomplished, the burlesque character, anticipating, on the Baron’s lips, the question that was about to spring from them, said, in a slightly emphatic and declamatory tone: ‘Please forgive me, noble castellan, if I come knocking at the postern of your fortress without being preceded by a page, or a dwarf blowing a horn, and at this late hour. Necessity knows no laws, and forces the politest people in the world to barbaric conduct.’

— ‘What is it you want?’ interrupted the Baron rather sharply, annoyed by the old fellow’s verbiage.

— ‘Hospitality for me and my comrades, princes and princesses, Leanders and Isabellas (commedia dell’arte characters), doctors and captains who travel from town to town, in the chariot of Thespis (the first actor, according to Greek legend, being also a poet and dramatist), which chariot, drawn by oxen in the ancient manner, is now stuck in the mud a few steps from your castle.’

— ‘If I understand you correctly, you are provincial actors on tour, and you have deviated from the straight and narrow?’

— ‘My words could not be better explained,’ replied the actor, ‘and what you say fits the situation precisely. May I hope that Your Lordship will grant my request?’

— ‘Though my house is rather dilapidated and has little to offer, you will nonetheless be a little more comfortable here than out in the open, in the pouring rain.’

The Pedant, for such appeared to be his commedia dell’arte role, bowed in assent.

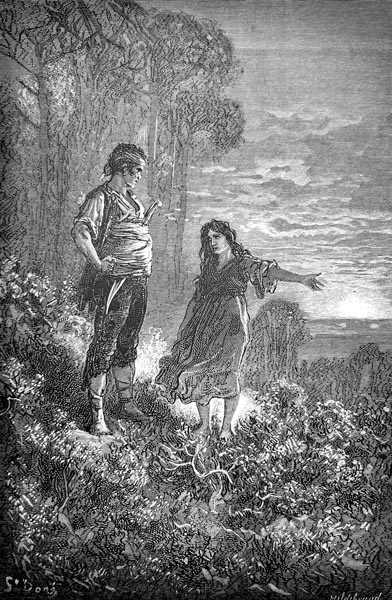

During this conversation, Pierre, awakened by Miraut’s barking, had risen, and joined his master in the porch. Informed of what was happening, he lit a lantern, and all three headed towards the foundered wagon.

The ‘Leander’ and the ‘Captain Matamore’ (two other commedia dell’arte characters, ‘Matamore’ means ‘Braggart’) of the troupe set their shoulders to the wheels, while the ‘Tyrant’ pricked the oxen with his ‘tragic’ dagger. The women, wrapped in their cloaks, moaned in despair, and uttered little cries. The unexpected reinforcements, and especially Pierre’s experience, soon extracted the heavy wagon which, directed to firmer ground, reached the castle, passed under the ogival vault, and was soon stationary in the courtyard.

‘The unexpected reinforcements, and especially Pierre’s experience, soon extracted the heavy wagon.’

The unharnessed oxen went to take up their places in the stable, next to the white Breton pony; the actresses jumped out of the wagon, smoothing their crumpled skirts, and ascended, guided by Sigognac, to the dining room, the most habitable room in the house. Pierre found a bundle, and a few loose armfuls, of brushwood in the depths of the woodshed, which he added to the fireplace, and which began to blaze cheerfully. Though it was still only the start of autumn, the fire was necessary to dry the ladies’ damp clothing; besides, the night air was cold, and whistled through the disjointed woodwork of that frequently uninhabited room.

The actors, though accustomed by their wandering life to the most diverse lodgings, looked with astonishment at this strange dwelling which seemed long since abandoned to the shades of the dead, and which involuntarily gave rise to thoughts of past tragedies; yet, as well-bred people, they showed neither terror nor surprise.

— ‘I can give you no more than a table to eat at,’ said the young Baron, ‘my pantry barely contains enough to feed a mouse. I live alone in this manor, and never receive guests, and, as you can see without my saying, Fortune does not dwell here.’

— ‘No matter,’ replied the Pedant; ‘though, in the theatre, we are served cardboard chickens and bottles carved from wood, we deal, in real life, with more substantial dishes. Those hollow pieces of meat and simulated drinks would rest poorly on our stomachs, and, as quartermaster of the troupe, I always keep a little Bayonne ham in reserve, along with some venison pâté, a loin of Rivière veal (from the river-meadows near Rouen, by the Seine,), and half a score of bottles of Cahors and Bordeaux wine.’

— ‘Well said, Pedant,’ exclaimed Leander, ‘go and fetch the provisions, and if this lord permits it and deigns to sup with us, let us set the table here for a feast. There is enough crockery in these sideboards, and these ladies will set the table for us all.’

At a nod of assent from the Baron, who was quite astounded by the whole adventure, Isabella and Donna Serafina both seated near the fireplace, rose and laid the table, which had been previously wiped clean by Pierre, and covered with an old, worn, but still white tablecloth. The Pedant soon reappeared carrying a basket in each hand, and triumphantly placed, in the centre of the table a fortress of a pie with blond and golden walls, which enclosed within its flanks a garrison of ortolans and partridges. He surrounded this gastronomic fort with six bottles, to act as advanced works, which would have to be taken away before the fortress could be conquered. A smoked ox-tongue, and a slice of ham, completed the symmetry.

Beelzebub, who had perched on top of a sideboard and, full of curiosity, was following these extraordinary preparations with his eyes, tried to appropriate, at least by smell, all these exquisite things displayed in abundance. His truffle-coloured nose inhaled the fragrant emanations deeply; his green eyes exulted and sparkled, while a little hint of covetousness silvered his moist chin. He would have liked to approach the table and take his share of this Gargantuan-style feast so beyond the normally hermitic sobriety of the house; but the sight of all these new faces terrified him, and his cowardice countered his gluttony.

Not finding the light of the lamp sufficiently radiant, Captain Matamore recovered two theatrical torches, made of wood wrapped in gilded paper and each equipped with several candles, from the wagon, reinforcements which produced a rather magnificent level of illumination. Such torches, whose shape recalled that of the seven-branched candlestick of Scripture (see Exodus 25: 31-40), were ordinarily placed on the marriage altar, at the conclusion of plays with spectacular staging, or on the banquet table in Alexandre Hardy’s ‘Mariamne’ (c1605) and ‘La Marianne’ by Tristan L’Hermite (François L’Hermite, 1636; ‘La Marianne’ is derived from Hardy’s play).

In their light, and that of the blazing brushwood, the moribund room had taken on a kind of life. Faint blushes coloured the pale cheeks of the portraits once more, and if the virtuous dowagers, huddled in their ruffs and stiffened beneath their farthingales, took on a somewhat frosty air at the sight of the young actresses frolicking in that grave manor-house, the warriors and Knights of Malta, on the other hand, seemed to smile at them from the depths of their frames, happy to attend such a celebration, with the exception of two or three old grey-moustachioed gentlemen stubbornly sulking beneath their yellow varnish, and retaining, despite everything, the forbidding expressions with which the painter had endowed them.

A warmer and more lively air circulated in this vast room, where one usually breathed only the mouldy humidity experienced in a sepulchre. The decayed state of the furniture and hangings was less visible, and the pale spectre of misery seemed to have abandoned the castle even if only for a few moments.

Sigognac, to whom their surprising arrival had at first seemed disagreeable, gave way to an unknown sensation of well-being. Isabella, Donna Serafina, and even the Soubrette, gently troubled his imagination and seemed to him more like divinities descended to earth than mere mortals. They were, in fact, very pretty women, and would have occupied the thoughts of lesser novices than our young baron. All this produced a dream-like effect, and he feared at any moment to awake from its delights.

The Baron gave Donna Serafina his hand, and placed her on his right. Isabella took a seat on his left, the Soubrette sat opposite, the Duenna sat next to the Pedant, and Leander and Captain Matamore, sat where they chose. The young master of the castle was then able to study at leisure the faces of his guests, brightly-illuminated and highlighted in full relief. His examination focused first on the women, of whom it would not be out of place to draw a slight sketch here, while the Pedant made a breach in the ramparts of the pie.

Serafina was a young woman of twenty-four or twenty-five, whose habit of playing the grande coquette had given her a worldly air, and somewhat the manners of a lady of the Court. Her face, a slightly elongated oval, her slightly aquiline nose, her grey eyes set flush with her head, her crimson mouth, whose lower lip was cut by a small cleft, like that of Anne of Austria, and resembled a cherry, formed a charming and noble physiognomy, to which twin cascades of chestnut hair falling in waves across her cheeks contributed; a physiognomy to which animation and warmth had brought pretty shades of pink. Two longish locks of hair, each tied by a trio of rosettes of black ribbon, detached themselves capriciously from her crimped curls, and emphasised their vaporous grace much as do the vigorous touches a painter gives to the picture he is completing. Her round-brimmed felt hat, adorned with feathers, the last of which curled around the lady’s shoulders in a plume, while the others curled in billows, gave Serafina the look of a cavalier; a man’s turned-down collar, trimmed with Alençon lace, and fastened in front by a black ribbon, overlapped a green velvet dress with slashed sleeves, trimmed with braided cords and knots, whose cleavage allowed her linen to show; and a white silk scarf, across the shoulder, completed her gallant and resolute appearance.

Thus attired, Serafina had the air of a Penthesilea (the Amazonian queen who fought at Troy) or a Marfisa (the queen of India who fought for the Saracens in the ‘Orlando Innamorato’ of Matteo Boiardo, and its sequel the ‘Orlando Furioso’ of Ludovico Ariosto), most appropriate to adventures and comedies involving cloaks and swords. Certainly, all her attire was not in its first freshness, wear had polished the skirt’s velvet in places, the frieze-cloth was a little crumpled, the lace would have appeared a little russet in hue in broad daylight; the embroidery of the scarf, on closer inspection, was reddening, and betrayed the underlying strips of tinsel; several braided cords had lost their studs, and the braid of various knots had unravelled in places; the ruffled feathers of her plume flapped flaccidly against the edges of the felt, her hair was a little uncurled, and a few straws, acquired during the journey by hay-wagon, mingled rather poorly with its opulence.

These small details did not prevent Donna Serafina from showing the bearing of a queen without a kingdom. Though her dress was faded, her face was fresh and glowing, and, indeed, her attire seemed the most dazzling in the world to the young Baron de Sigognac, unaccustomed to such magnificence, and who rarely saw anything but peasant women dressed in sackcloth skirts and shiny woollen capes. He was, moreover, too preoccupied with the lady’s eyes to pay attention to any deficiencies in her costume.

The company’s ‘Isabella’ was younger than Donna Serafina, as her role as an ingénue required; nor was her costume so audacious, but of an elegant and bourgeois simplicity, as befits the daughter of Cassandro (a commedia dell’arte character, elderly and troublesome). She had a charming face, almost childlike; lovely hair, a silky chestnut in hue; eyes veiled by long eyelashes; a small heart-shaped mouth; and an air of virginal modesty, more natural than feigned. A bodice of grey taffeta, trimmed with black velvet and jet, extended downwards to a point over a skirt of the same colour; a ruff, slightly starched, rose behind her pretty neck where little curls of wild hair, and a string of false pearls bordered her nape; and although at first sight she attracted the eye less than did Serafina, she held the attention longer. If she did not dazzle, she charmed, which has its advantages.

The Soubrette fully deserved the epithet morena that the Spaniards endow brunettes with. Her skin was golden and tawny in tone like that of a gypsy-girl. Her thick, frizzy hair was a deep black, and her yellow-brown eyes sparkled with diabolical malice. Her mouth, large and crimson red, revealed a set of teeth, flashing white, that would have done credit to a wolf cub. In addition, she was lean, as if consumed by ardour and wit, but with that youthful healthy thinness that is not unpleasant to look at. She was doubtless as expert at delivering and receiving a love-letter in the city as on the stage; but the lady who used such a ‘Dariolette’ (a go-between; the character created by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo in his novel Amadis de Gaula, 1508) must surely be reliant on her charms! In her hands, more than one declaration of love had not reached its destination, and the neglected gallant was left lingering in the antechamber. She was one of those women whom their female companions find ugly, but who are irresistible to men, one seemingly seasoned with salt, pepper, and cantharides (Spanish fly, an extract from the blister beetle, a traditional aphrodisiac) though that fails to prevent them from being as cold as usurers when it comes to their own interests. A fanciful costume, blue and yellow with a bib of false lace, composed her attire.

Dame Leonarda, the noble mother of the troupe, was dressed all in black like a Spanish duenna. Her plump, many-chinned face was framed by a muslin headdress, pale and soiled as if by forty years’ worth of rouge. Shades of yellowed ivory, and old wax, paled her unhealthy plumpness, which derived more from age than unhealthiness. Her eyes, above which hung drooping eyelids, had a shrewd expression, and were like two black spots in her pale face. A few hairs were beginning to obscure the corners of her lips, although she carefully plucked them out with tweezers. Feminine character had almost disappeared from this face, the wrinkles of which might have a told a tale or two, had anyone taken the trouble to look for them. An actress since childhood, Dame Léonarda had followed a career in which she had successively filled all the roles, and now that of duenna, so difficult for the coquette to accept, being always unconvinced of the ravages of time. Leonarda had talent, and old as she was, she knew how to win applause, even when cast beside the young and pretty, who were surprised to see the cavaliers pay their addresses to this ‘witch’.

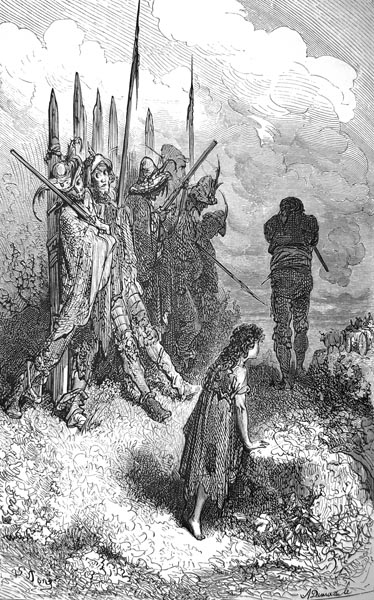

So much for the women. The main female roles of comedy were represented there, and if a character was missing, some wandering actor, or follower of the theatre, acquired along the way, was ever happy to take on some small role, and thus bolster the Angelicas and Isabellas. The male cast consisted of the Pedant, already described and to whom there is no need to return, Leander, Scapin, the Tyrant, and Captain Matamore, the Braggart.

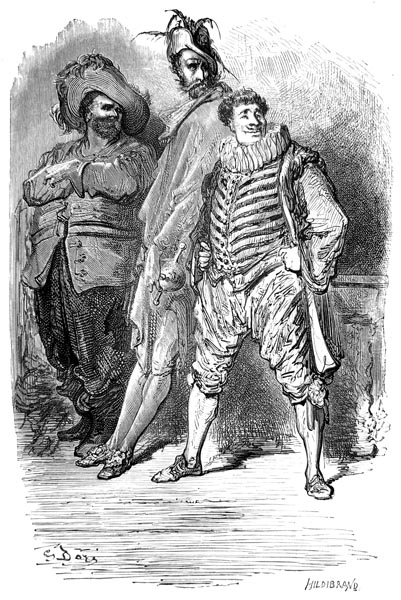

(Left to right) The Tyrant, Captain Matamore, and Scapin

Leander, obliged by his role to render the fiercest Hyrcanian tigress as gentle as a sheep, to dupe Truffaldino (the ‘Servant of Two Masters’, in Carlo Goldoni’s play, and a variant of Harlequin), to push aside Ergastes (the shepherd in Honoré d’Urfe’s ‘Astrea’), and to ever appear superb and triumphant on stage, was a young man of thirty whose excessive care for his own person made him appear much younger. It is no small matter to represent, for the audience, the ‘Lover’, that mysterious and perfect being, whom each one fashions as he pleases after Amadis or Celadon (the lover in ‘Astrea’). So, Leander greased his muzzle with whale blubber, and floured himself every evening with talcum powder; his eyebrows, from which he plucked the unruly hairs with tweezers, each resembled a line drawn in Indian ink, and ended in a rat’s tail. His teeth, brushed to excess and rubbed with paste, shone like oriental pearls in his red gums, which he uncovered at every opportunity, ignoring the Greek proverb that says ‘a fool laughs even when nothing is amusing’ (Arsenius, 5.29b). His comrades claimed that, even in the city, he added a touch of rouge to brighten the effect of his eyes. Black hair, carefully arranged, twisted across his cheeks in shiny spirals, now a little sodden from the rain, which he took the opportunity to twine with a finger on which glittered a diamond much too large to be real, thus revealing a very white hand. His turned-down collar revealed a rounded, white neck shaved so closely that no beard was visible. A length of fairly clean linen showed between his jacket and his hose, piped with a world of ribbons, the preservation of which seemed to occupy him greatly. Gazing at the wall, he seemed to be dying of love, and could scarcely ask for a drink without swooning. He punctuated his sentences with sighs and, when talking about the most indifferent things, he winked, launched meaningful glances, and made laughable faces; but the women found him charming.

The Tyrant, for his part, was a most benign man whom nature had endowed, doubtless as a jest, with all the outward signs of ferocity. Never did a gentler soul display a more forbidding exterior. Large, black eyebrows, two fingers wide, as if they had been made of moleskin, meeting at the root of his nose; frizzy hair; a thick beard reaching up to his ears, which he neglected to trim so as not to have to adopt a hairpiece when he played the tyrannous Herod, or Polyphonte (see Voltaire’s ‘Mérope’, 1743); a swarthy complexion of a hue akin to that of Cordoba leather, gave him a truculent and formidable look, such as painters like to grant to executioners and their assistants, when depicting the flaying of Saint Bartholomew, or the beheading of John the Baptist. A bull’s bellow of a voice that made the windows tremble, and the glasses on the table rattle, contributed not a little to maintaining the terror inspired by his appearance, that of a bogeyman, which was enhanced by a black velvet doublet in an outmoded style; he achieved enormous success by howling out, terrifyingly, lines from the dramas of Robert Garnier and Georges de Scudéry. He was, moreover, ample in breadth, and capable of filling a throne.

Captain Matamore had a thinnish face, gaunt, dark, and scorched, like a hanged man in summer. His skin looked like parchment stuck to the bones beneath; while a large nose, curved like the beak of a bird of prey, the narrow bridge of which gleamed like horn, partitioned the two sides of a face like a shuttle-shaped knife-blade, which was further lengthened by a pointed goatee. These twin profiles, separate yet close together, found great difficulty in forming a whole face, and the eyes, to accommodate their presence, were upturned somewhat in the Chinese manner towards the temples. The half-shaven eyebrows curved into a black comma above anxious-seeming pupils; his moustaches, of an excessive length, greased and coated at each end with pomade, rose in an arc to stab at the sky; his ears set far apart from the surface of the head represented the twin handles of a cooking pot, and provided a grip for those who might deal a light flick or a punch to his nose. All these extravagant features, more caricatured than natural, might have been sculpted in playful fancy on the head of a rebec (a Medieval and early Renaissance stringed instrument with an angled head to the neck) or copied from those absurd creatures, those chimeras à la Rabelais, which rotate in the evening on pastry-cooks’ lanterns. His hair was tawny and, similar to a wolf’s coat was felt-like, reinforcing the character of some malicious beast that his physiognomy conveyed. One was tempted to look at the hands of this fellow to see if there were any calluses on them caused by handling the oar, for he certainly looked as if he had spent several seasons writing his memoirs, at sea, with that fifteen-foot quill. His falsetto voice, sometimes high, sometimes low, proceeded by sudden changes of tone and bizarre yelps, which surprised one, and made one laugh without wishing to; and his unexpected movements, as if determined by the sudden release of a hidden spring; represented something illogical and disturbing, and seemed to serve more to delay an interlocutor than to express a thought or a feeling. They were part of the fox’s swift gyrations, as he performed a hundred evolutions beneath the tree from the top of which the fascinated turkeys observed him before falling, dizzied, to the ground (see Aesop’s fable ‘The Fox and the Turkeys’). He wore a grey smock over his costume, the stripes of which were visible, either because he had not had time to undress after his last performance, or because the limited capacity of his trunk, allowed him too little room to pack both his city clothes and his theatrical clothes, but over the smock he had draped, for greater effect, a blanket whose border was raised by his sword, an oversized rapier that he never discarded, and whose iron hilt, of fenestrated openwork, weighed a good fifty pounds. Had he danced, his cockerel-legs would have swung about like flutes in their carrier when the musician bears them away. Such were the accoutrements of this rascal. Let me add, so as not to omit anything, that two cockerel-quills, bifurcated like a cuckold’s crest, adorned, grotesquely, his grey felt hat, which was extended into a funnel of cloth.

As for Scapin, he had a fox’s face, shrewd, pointed, mocking: his eyebrows rose on his forehead in the shape of circumflex accents, above swivel eyes ever in motion, whose yellow pupils trembled like gold coins in quicksilver; crow’s feet, forming malignant wrinkles, creased the corners of his eyelids fit to conceal lies, trickery, and deceit; his lips, thin and flexible, moved perpetually, and showed, through an equivocal smile, sharp canines rather ferocious in appearance; and, when he removed his white and red striped cap, his short hair revealed the contours of a strangely humped head. His boastful grimaces had become, in the long run, his habitual physiognomy and, on emerging from the wings, he would walk onstage, legs flung wide as those of a compass, head thrown back, his left hand, rounded in a fist, on his hip, and his right hand on the hilt of his sword. A yellow jerkin, curved like a cuirass, embellished with green, and slashed in the Spanish-style, its slits ranged along the ribs; a starched ruff supported by iron wire and cardboard, as wide as the Round Table and about which the Twelve Peers could have taken their meals; breeches adorned with, and held up by strips of braid; and pale shoes of Russian leather, completed his costume.

The writer’s art is inferior to that of the painter in that it can only describe objects successively. In a painting, a glance would be enough to grasp the various figures, grouped by the artist about the table, whose forms have just been detailed; one could view them there, the shadows and highlights, their contrasting attitudes, the colours proper to each, and an infinity of details as regards the scene, which are missing from a description already too extensive, though I have sought to make it as brief as possible; yet it was necessary in order to acquaint you with this comedy troupe that had penetrated, so unexpectedly, the solitude of the manor of Sigognac.

The meal commenced in silence; great appetites are mute like great passions! But, the first pangs of hunger appeased, tongues were loosened. The young Baron, who perhaps had not dined adequately since the day he was weaned, although possessed by the greatest longing in the world to appear an amorous and romantic figure before Serafina and Isabella, ate, or rather devoured, the meal with an ardour that would not have aroused the slightest suspicion that he had already eaten. The Pedant, amused by this youthful hunger, heaped partridge-wings and slices of ham onto the lord of Sigognac’s plate, which disappeared as swiftly as snowflakes on a red-hot shovel. Beelzebub, in transports of gluttony, had determined, despite his fears, to leave the unassailable post he occupied on the cornice of the dresser, and had concluded, triumphantly, that it would be hard for any of the troupe to tug at his ears, since he possessed none, and that none of them could indulge in the vulgar jest of shining a saucepan on his rear end, since his missing tail prohibited such an act, one more worthy of rogues than decent folk, as the guests gathered around this table, laden with dishes of unusual succulence and fragrance, seemed to be. He had approached, taking advantage of the shadows, and so flat to the ground that the joints of his front legs formed angles above his head, like a black panther stalking a gazelle, without anyone having paid any attention to him. Having reached the Baron’s chair, he had reverted to his normal stance, and, so as to attract the attention of his master, plucked a tune on his knee with his ten claws as if playing a guitar. Sigognac, indulgent to this humble friend who had suffered so long from lack of nourishment in his service, allowed him to share in his good fortune by passing him bones and leftovers under the table, which were received with frantic gratitude. Miraut, for his part, who had managed to enter the banqueting hall behind Pierre, also received more than one good morsel.

Life seemed to have returned to this dead dwelling; there was light, warmth, and noise. The actresses, having drunk two fingers of wine, chattered away like parakeets on their perches, and complimented each other on their mutual successes. The Pedant and the Tyrant disputed over the superiority of theatrical comedy or tragedy; the one maintaining that it was harder to make honest people laugh than to frighten them with nursery tales whose only merit was their antiquity; the other claiming that the scurrility and buffoonery employed by the makers of comedies greatly debased the author. Leander had taken a small mirror from his pocket and was gazing at himself with as much complacency as the long-dead Narcissus viewing his reflection in the water. Contrary to Leander’s custom, he was not in love with Isabella; he aimed higher. He hoped, by means of his grace and gentlemanly manners, to catch the eye of some rich and readily-moved widow, whose four-horse carriage would arrive to collect him at the stage door, and carry him off to some château, where the susceptible beauty would await him, dressed in the most charming of negligées, seated in front of a most delightful feast. Had this vision ever been realised? Leander affirmed it... Scapin denied it, and it was the subject of endless disputes between them. Scapin, that accursed valet, as malicious as a monkey, claimed that poor Leander had fluttered his eyes, cast murderous glances at the boxes, laughed so as to show his thirty-two teeth, stretched his hamstrings, arched his waist, passed a small comb through the hair of his wig, and changed his linen for each performance, even though he had been forced to skip lunch to pay the laundress, but had not yet managed to make the least baroness, even one of forty-five years or more, afflicted with rosacea, and adorned with an incipient moustache, yearn for his presence.