Théophile Gautier

Captain Fracasse (Le Capitaine Fracasse)

Part IV: Chapters XVI-XXII

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2025 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Chapter XVI: Vallombreuse.

- Chapter XVII: The Amethyst Ring.

- Chapter XVIII: En Famille.

- Chapter XIX: Nettles and Spiders’ Webs.

- Chapter XX: Chiquita’s Declaration of Love.

- Chapter XXI: Hymenaios, O Hymenaios!

- Chapter XXII: Epilogue – The Castle of Happiness.

Chapter XVI: Vallombreuse

Isabella, left alone in that unfamiliar room whence danger might arise at any moment in mysterious form, felt her heart oppressed by an inexpressible anguish, even though her wandering life had given her more courage than was common. Yet there was nothing sinister about the place, with its old yet well-maintained luxury. The flames danced cheerfully about the enormous logs in the hearth; the candles shed a bright light which, penetrating to the smallest corners, chased away her fearful imaginings along with the shadows. A gentle warmth reigned within, and everything invited a comfortable feeling of well-being. The paintings in the panels were too well-lit to take on any stranger an aspect, and the portrait in its ornamental frame above the fireplace, which Isabella had first noticed, lacked that fixed gaze, seen on the faces in certain pictures, which seems to follow one so frighteningly. Rather, the figure seemed to smile with a quiet, protective kindness, like the image of a saint one might invoke in times of danger. All this collection of tranquil, reassuring, and hospitable things failed to calm Isabella’s nerves, still quivering like the strings of a guitar that have just been plucked; her glance wandered, anxiously and furtively, about her, since she wished to look but feared to look, while her over-agitated senses tried to interpret, amidst the profound stillness of the night, those imperceptible noises which are the voice of silence, and which terrified her. Lord knows what formidable meanings she attributed to them! Soon her uneasiness became so great that she resolved to quit the room, despite it being so well-lit, warm, and comfortable, and venture into the corridors of the château, at the risk of some dubious encounter, in search of some obscure exit, or a place of refuge. After checking that the doors of her room were not locked, she took, from the side-table, the lamp that the footman had left there for the night and, sheltering it with her hand, set out.

First of all, she located the staircase, with its intricate ironwork banisters, which she had climbed, escorted by the servant; she descended, thinking, rightly, that no exit favourable to her escape existed on the first floor. At the foot of the stairs, in the vestibule, she perceived a large double door, one knob of which she turned. That side of the door opened before her, with a creaking of wood and a grinding of hinges, the noise of which seemed to her equal to that of thunder, though it was scarcely audible three paces away. The dim light of the lamp, whose wick gave off a crackling sound in the damp air of this apartment long-sealed, revealed, or rather offered the young actress, a glimpse of, a vast room, in no way dilapidated, but possessing the deadened feel of a place no longer used; large oak benches leaned against the walls covered with figured tapestries; trophies, formed of coats of arms, gauntlets, swords, and shields, lit by the sudden gleams of candlelight, hung there. A heavy table, on massive legs, with which the young woman almost collided, occupied the centre of the room; she circumnavigated it, but imagine her terror when, on approaching the door which faced the entrance and gave access to a further room, she encountered two figures armed from head to toe, motionless as sentinels, placed on each side of the doorway, their gauntlets crossed on the hilts of large swords whose points had been driven into the floor: the grilles of their helmets represented the faces of hideous birds, the holes simulated their eyes, and the nosepieces their beaks; on the crests, iron plates chiselled to represent feathers bristled like roused and palpitating wings; the lower part of the breastplate, gleaming luminously, bulged in a strange manner, as if swollen by full lungs beneath; from each knee and elbow pad protruded a point of steel curved like an eagle’s claw, and the ends of each sabaton (steel shoe) also extended in a claw. In the flickering light of the lamp, which trembled in Isabella’s hand, these two iron phantoms took on a truly frightening appearance, well-calculated to alarm the most courageous. Also, poor Isabella’s heart was beating so hard that she could hear it throb, and feel the tremors in her throat. One may well believe she regretted having left the room on this adventurous nocturnal expedition. However, as the warriors were motionless, though her presence was obvious, nor made any attempt to brandish their swords to block her path, she approached one of them, and held the lamp beneath its nose. The man-at-arms was not at all troubled and, completely insensible, maintained his pose. Isabella, emboldened, and suspecting the truth, raised the visor which, once open, revealed only a void full of shadow, like a helm on a coat of arms. The two sentries were simply suits of curiously-wrought German armour, arranged on mannequin bodies. But the illusion was indeed credible for a poor captive wandering at night in a solitary castle, so much do these metallic shells like militaristic statues, modelled on the human body, recall its form even when empty, and render it more formidable with their rigid projections, and articulated joints. Isabella, despite her situation, could not help but smile on recognising her error, and like the heroes of chivalric romances, when, by means of a talisman, they have broken the spell that binds an enchanted palace, she bravely entered the second room, no longer concerned by the twin guards thus reduced to impotence.

The chamber was a vast dining room, as evidenced by tall carved-oak dressers on which valuable objects shone dimly: ewers, salt-cellars, spice-boxes, goblets, vases with swollen bellies, great silver or silver-gilt platters resembling shields or chariot wheels, and Bohemian and Venetian glassware, in slender and capricious forms, which, caught by the light, displayed gleams of green, red, and blue. Square-backed chairs arranged around the table seemed to be awaiting guests who never arrived, or, at night, might seat a host of shadowy diners. Cordovan leather, embossed with gold and patterned with flowers, stretched over the oak panelling that covered the walls to half-height, lit up here and there with tawny reflections as the lamp passed over them, adding to the darkness a warm, sombre richness. Isabella, glanced at this aged magnificence and hastened to cross the room to a third door.

The room she now entered, which seemed to be the main salon, was larger than the others, already spacious. The light of the lamp failed to illuminate its depths, and its feeble rays were lost a few steps in front of Isabella, the yellowish threads shining like sunlight in fog. Despite its paleness, the light pierced the shadows sufficiently to render the darkness frightening, and highlight contorted figures, vague sketches of things whose forms fear and imagination completed. Ghosts draped themselves in curtain-folds; the armchairs seemed to seat spectres, and monstrous shapes crouched in the darkest corners, hideously curled upon themselves, or clinging there by bat-like claws.

Quelling these imaginary terrors, Isabella continued on her way, and saw at the rear of the room a lordly canopy topped with feathers, decorated with coats of arms, whose blazons it would have been difficult to decipher, and surmounting a throne-like armchair placed on a platform covered with carpeting, which was reached by three steps.

‘Quelling these imaginary terrors, Isabella continued on her way…’

All this, bathed, confused, drowned in shadow, betrayed only by a few reflections, took on a fierce, colossal and mysterious grandeur. The chair seemed as if presiding over a gathering of spirits, and it would not have required a great effort of the imagination to see a dark angel with long black wings seated therein.

Isabella quickened her pace, and, despite her lightness, the creaking of her shoes seemed dreadfully loud amidst the silence. The fourth room was a bedroom partly occupied by an enormous bed whose curtains, made of dark-red Indian damask, fell heavily from the frame. At its side, the silver crucifix above an ebony prie-dieu shimmered. A curtained bed, even in daylight, is somehow disturbing. One wonders what lies behind those drawn hangings; but at night, in an abandoned room, a closely-draped one is frightening indeed. It may hide a sleeper, a corpse, even a living being lying in wait. Isabella thought she heard behind the curtains the deep, intermittent, rhythmic breathing of a sleeping person; was it illusion or reality? Eager to make sure, she dared to push aside the folds of red fabric and allowed the beam of her lamp to fall on the empty bed.

A library followed the bedroom. In cupboards surmounted by the busts of poets, philosophers, and historians, who observed Isabella with large blank eyes, were shelved numerous volumes, in some disorder, their spines labelled with numbers and titles, the gilding of which was illuminated by the passage of her lamp. At this point, she reached a corner of the building and emerged into a long gallery occupying a different facade of the courtyard. Here, family portraits followed one another in chronological order. A row of windows faced the wall on which these paintings hung in frames of reddened old-gold. Shutters, each pierced at the top with an oval hole, covered these windows, and the arrangement produced at that moment a singular effect. The moon had risen, and its rays pierced these holes painting its light on the opposite wall; sometimes the bluish patch illuminated the face of a portrait and adorned it with a pallid mask. Beneath the magical glow, the painting then took on an alarming life, all the more so because, the body remaining in shadow, the head with its silvery pallor seemed to spring from its frame, as if carved in solid relief, to watch Isabella pass by. Others, which only the lamplight reached, maintained, beneath the yellowed varnish, their solemn, and dead attitude, yet it seemed that, through their dark eyes, the ancestral souls looked out on the world, as if through openings formed expressly for that purpose, and they were not the least sinister effigies in the collection.

It was for Isabella, courageous as she was, as brave an action to traverse this gallery, lined with threatening figures, as for a soldier to march in step before a firing squad. A cold sweat soaked her chemise between her shoulders as, anguished, she felt that these phantoms in breastplates and doublets adorned with orders of chivalry, and these dowagers with high ruffs and outsized farthingales, were descending from their frames behind her, and following, funereally, in procession. She even thought she could hear vague footsteps brushing, almost imperceptibly, the parquet floor at her heels. Finally, she reached the end of the long corridor and came to a glass door which opened onto the courtyard; she opened it, not without bruising her fingers on the old rusty key which turned with difficulty in the lock, and after having taken care to hide her lamp, so as to find it if and when she retraced her steps, she left the gallery, that place of terror and nocturnal phantoms.

At the sight of the open sky, in which a few stars, not quite eclipsed by the white light of the moon, glittered with a silvery scintillation, Isabella felt profound and delicious joy, as if she were returning from death to life; it seemed to her that God now looked down on her from his firmament, whereas he might well have forgotten her when she was lost in the intense darkness, under those obscure ceilings, amidst that maze of rooms and corridors. Though her situation was in no way improved, an immense weight had lifted from her breast. She continued her explorations, but the courtyard was enclosed on all sides like the inner court of a fortress, with the exception of a postern, or brick arch, doubtless opening onto the moat, for Isabella, leaning cautiously over it, felt a cool dampness, like that above deep water, rise to her face with a gust of air, and she heard the faint murmur of waves lapping at the base of the moat’s wall. It was probable that the castle’s kitchens were supplied from this moat; but to reach the far side, a boat would be needed, housed no doubt at the foot of the rampart, in some shed beyond Isabella’s reach.

Escape was therefore as impossible on this side as on the others. This explained her relative freedom. Her cage was open, but only like those of exotic birds transported by sea, which, as we know, are obliged to return to perch on the mast after a brief excursion, since the nearest land is still so far away that their wings would cease to bear them before they could reach it. The moat round the castle acted the role of the ocean round a ship.

In a corner of the courtyard, a reddish glow filtered through the shutters of a ground-floor room, and, amidst the nocturnal silence, a vague murmur emanated from its shadowy angle. Isabella moved towards the light and the associated sounds, stirred by a feeling of curiosity readily comprehended; she applied her eye to these shutters, less hermetically sealed than the rest, and was easily able to see what was happening inside the room.

Around a table lit by a three-pronged lamp, which was suspended from the ceiling by a copper chain, a group of rogues of fierce and truculent mien were banqueting, among whom Isabella, though she had only seen them masked, easily recognised the men who had participated in her abduction. They were Piedgris, Tordgueule, La Râpée and Bringuenarilles, whose forms suited their charming names. The light falling from above made their foreheads shine, plunged their eyes into shadow, outlined the bridges of their noses, and clung to their extravagant moustaches, so as to exaggerate still further the savagery of those heads which scarcely needed to be illuminated to appear frightening. A little further away, at the end of the table, was seated, like some provincial brigand who could not compete with Parisian swordsmen, Agostin, free of the wig and false beard which had served him well when playing the part of the blind man. In the place of honour sat Malartic, unanimously elected king of the feast. His face was even paler and his nose redder than usual; a phenomenon which could be explained by the number of empty bottles arranged on the sideboard, like corpses borne from battle, and by the number of full bottles which the sommelier placed in front of him with tireless agility.

Isabella could only make out a few words, amidst the confused conversation of the drinkers, the meaning of which most often escaped her; since they were terms employed in the gambling dens, taverns, and fencing halls, sometimes even hideous slang terms borrowed from the dictionary of the Court of Miracles (the slum district in Paris populated by beggars whose ailments miraculously vanished when not begging) where the languages of Egypt and Bohemia are spoken. She found nothing in these fellows’ speeches that enlightened her as to her fate, and somewhat overcome by the cold, she was about to withdraw when Malartic, to obtain silence, struck the table a frightful blow, that made the bottles reel as if they too were inebriated, and the glasses clink together with a crystalline ringing yielding the notes do, mi, so, ti. The topers, drunk though they were, jumped half a foot in the air on their benches, and their faces turned, instantly, towards Malartic.

Taking advantage of this respite from the noise, Malartic rose, and lifting his glass, the wine glowing in the light like the gem set in a ring, said: ‘Friends, listen to this song I’ve composed, for I employ the lyre as well as the sword; tis a Bacchic song as befits a true drunkard. Fish, that drink water, are mute; if they drank wine, they would sing. So, let us show that we are human with a melody to accompany our drinking session.’

— ‘The song! The song!’ cried Bringuenarilles, la Râpée, Tordgueule and Piedgris, unable to comprehend such subtle dialectic.

Malartic cleared his throat, with a vigorous ‘Hem!’ or two, and, with all the manners of a singer summoned to the king’s chamber, he intoned, in a voice which, though a little hoarse, was not lacking in pitch, the following verses:

‘To Bacchus, that drunkard divine,

All shout “Drink!” and sing, as one:

“Long live the pure juice of the wine,

Trampled from the fruit of the vine!

And long live the ruby liquor won!”

Priests of the vine and grape are we,

The hue of the vintage, now, we bear.

The bottle holds the crimson we see,

With which the grape dyes you and me,

And pricks our noses, here and there.

Shame on him who sips clear water

Instead of downing the purest wine,

Let him bow down to jug and pitcher!

Or be changed to a frog forever,

And splash in the mud, no friend of mine!’

The song was greeted with cries of joy, and Tordgueule, who prided himself on poetry, did not hesitate to proclaim Malartic the emulator of Saint-Amant (Antoine Girard de Saint-Amant, 1594-1661, noted for his Bacchanalian songs) an opinion which proved the degree to which drunkenness had swayed his judgement. A glass of red, full to the brim, was raised by each in honour of the singer, and as the glasses were emptied, they each poured out the last drop onto a fingernail, conscientiously, to show they had done so. This round finished off the weakest of the band; La Râpée slid under the table, where he acted as a mattress for Bringuenarilles, Piedgris and Tordgueule, who being more robust, merely let their heads fall forward, and fell asleep with their crossed arms for pillows. As for Malartic, he sat upright in his chair, cup in hand, eyes wide open and nose glowing so bright a red that it seemed to be shedding sparks like iron from the forge; he repeated, mechanically with the solemn stupor of contained drunkenness, and without anyone joining him in the chorus:

‘To Bacchus, that drunkard divine,

All shout “Drink!” and sing, as one.’

Disgusted by this spectacle, Isabella took her eye from the gap in the shutters, and continued her investigations, which soon found her beneath the vault in which hung the chains and counterweights of the castle’s raised drawbridge. There was no hope of setting the heavy mechanism in motion, and, as it was necessary to lower the bridge to leave, the courtyard having no other exit, the captive had to abandon all plans of escape. She returned to collect her lamp from where she had left it, by the door to the portrait gallery, which she traversed this time with less terror, since she now knew its cause, fear being increased by the unknown. She crossed the library, swiftly, the hall of honour, and all the rooms she had explored with anxious caution. It seemed laughable to her to have been so frightened by the suits of armour, and she climbed the stairs she had descended with a deliberate step, holding her breath, and on tiptoe, for fear of awakening the slightest echo from the silent walls.

But what was her terror when, at the threshold of her room, she perceived a figure seated by the corner of the hearth! It was certainly no ghost, since the light of the candles, and the rays from the fire illuminated it in a way too clearly for her to be mistaken; it was a slender and delicate figure, indeed, but very much alive, as attested by two large black eyes of a wild brilliance, lacking the dull gaze of a spectre, which fixed themselves on Isabella framed in the doorway, with a compelling calmness. Long brown hair, swept back, allowed one to see in all its details an olive-coloured face, with finely sculpted features, and a youthful and lively leanness, the half-open mouth revealing a set of teeth of dazzling whiteness. The hands, tanned by the open air, but charmingly formed, crossed over the chest, showed nails paler than the fingers. The figure’s bare feet did not reach the ground, the legs being too short to reach the parquet floor from the armchair’s seat. Through a gap in the coarse linen shirt, beads of a pearl necklace shone vaguely.

From this last detail, Chiquita was immediately identifiable. It was she, in fact, dressed not as a girl but as a boy still, having adopted that disguise to play the deceitful role of the blind man’s guide. This outfit, composed of a chemise and wide breeches, did not become her badly; for she was at that age when the person’s gender is not always obvious.

Recognising the strange creature, Isabella at once recovered from the emotion this unexpected apparition had caused her. Chiquita was not in herself very formidable, and besides, she seemed to profess, towards the young actress, a sort of confused and unmerited gratitude, which she had displayed in her own way in their last encounter.

Chiquita, while gazing at Isabella, murmured in a low voice the prose-song she had hummed in a wild tone, as she passed through the bull’s-eye window, during that first attempted kidnapping at Les Armes de France: ‘Chiquita climbs through the holes in the wall, dances on the edge of the bars…’

— ‘Do you still have the knife,’ said this strange creature to Isabella as she approached the fireplace, ‘the knife with three red stripes?’

— ‘Yes, Chiquita,’ replied the young woman, ‘I keep it here, between my blouse and my bodice. But why the question? Is my life in danger?’

— ‘A knife,’ said the little girl, whose eyes shone with a fierce light, ‘a knife is a faithful friend; it does not betray its owner, if its owner allows it to drink; for knives are thirsty.’

— ‘You frighten me, you wicked child.’ replied Isabella, troubled by those extravagantly sinister words, which, given the position in which she found herself, might contain a useful warning.

— ‘Sharpen the point on the marble fireplace,’ continued Chiquita, ‘and strop the blade on your leather shoe.’

— ‘Why are you telling me all this?’ said the actress, looking very pale.

— ‘No reason; but whoever wishes to defend themselves should ready their weapons, that’s all.’

These strange and fierce phrases worried Isabella, and yet, on the other hand, Chiquita’s presence in her room reassured her. The little girl seemed to bear her a sort of affection which, though based on an idle whim of her own, was nonetheless real. ‘I will never kill you!’ Chiquita had said; and, in her savage mind, it was a solemn promise, a pact of alliance which she would not fail to keep. Isabella was the only human being who, after Agostin, had shown her sympathy. She had received from her the first jewel by which her childish coquetry had been pleased, and, still too young to be jealous, she naively admired the beauty of the young actress. That sweet face exercised a seduction over her, who until then had seen only haggard and ferocious expressions harbouring thoughts of rebellion, plunder or murder.

— ‘How is it that you’re here?’ Isabella asked Chiquita after a moment of silence. ‘Are you tasked with guarding me?’

— ‘No,’ Chiquita replied: ‘I came alone; the light of the lamp and the fire guided me. I was bored, stuck in a corner while those fellows drank bottle after bottle. I am so small, young, and thin, that no one pays any more attention to me than to a cat asleep under the table. At the height of their din, I slipped away. The odours of wine and meat repel me, accustomed as I am to the scent of the heather and resinous pine trees.’

— ‘And weren’t you afraid to wander without a candle, through these long dark corridors, these vast rooms full of darkness?’

— ‘Chiquita knows no fear. Her eyes see amidst shadows. Her feet walk there without stumbling. If she meets an owl, the owl shuts its eyes, and the bat folds its wings when she approaches. The ghosts step aside to let her pass or they retreat. The night is her friend, and hides from her none of its mysteries. Chiquita knows the owl’s nest, the thief’s hiding place, the murdered man’s grave, the places haunted by spectres; but never speaks of them in daylight.’

As she uttered these strange words, Chiquita’s eyes shone with a supernatural brilliance. One might surmise that her spirit, exalted by solitude, believed itself to possess magical powers. The scenes of robbery and murder with which her childhood had been filled had exerted a strong influence on her ardent, uncultivated and feverish imagination. Her voice full of conviction had its effect on Isabella, who looked at her with superstitious apprehension.

— ‘I prefer,’ continued the girl, ‘to stay here, near the fire, beside you. You are beautiful, and I like to look at you; you resemble the good Virgin whom I saw shining on the altar; but only from a distance, for they chased me from the church, and set the dogs on me, on the pretext that my hair was unkempt, and my canary-yellow petticoat would make the faithful mock me. How white your hand is! Mine, set beside it, looks like a monkey’s paw. Your hair is as fine as silk; my mop bristles like a bush. Oh! I am very ugly, am I not?’

— ‘No, my little one,’ replied Isabella, touched in spite of herself by this naive burst of admiration, ‘you have your beauty too; you only need to be tidied a little to be the prettiest of girls.’

— ‘Do you think so? I’ll steal some nice clothes, so as to look well, and then Agostin will love me.’

This idea lit the child’s tawny face with a rosy glow, and for a few minutes she remained as if lost in a delightful and profound reverie.

— ‘Do you know where we are?’ Isabella asked, when Chiquita raised her eyelids, fringed with long black eyelashes that she had lowered for a moment.

— ‘In a castle belonging to the lord who has heaps of gold, and who wished to have you kidnapped in Poitiers. I had but to pull back the bolt, and it was done. But you had given me the pearl necklace, and I had no wish to cause you pain.’

— ‘Yet this time you helped to carry me off,’ said Isabella; ‘you don’t love me anymore, handing me over to my enemies thus?’

— ‘Agostin so ordered; it was necessary to obey. Besides, someone else would have acted as guide to the blind man, and I could not have entered the castle with you. Here, perhaps I can be of some use. I am courageous, agile, and strong, though small, and I would not see anyone hurt you.’

— ‘Is this castle where I am being held prisoner far from Paris?’ said the young woman, drawing Chiquita against her knee: ‘have you heard any of these men say its name?’

— ‘Yes, Tordgueule said the place was called...what was it again?’ murmured the girl, scratching her head in embarrassment.

— ‘Try to remember, my child,’ said Isabella, caressing Chiquita’s brown cheeks with her hand. The latter blushed with pleasure at this caress, for no one had ever shown her such attention.

— ‘I think it is Vall-om-breuse,’ replied Chiquita, syllable by syllable, as if listening to an inner echo. ‘Yes, Vallombreuse, I’m sure of it now; the very name of the lord your friend Captain Fracasse wounded in a duel. He would have done better to kill him. That duke is very wicked, though he scatters handfuls of gold about as a sower throws grain. You hate him, don’t you? And you would be very happy if you could manage to escape him.’

— ‘Oh, yes! But that’s impossible,’ said the young actress: ‘a deep moat surrounds the castle, and the drawbridge is closed. Any escape is impracticable.’

— ‘Chiquita laughs at gates, locks, walls, moats. Chiquita can leave the most secure prison at will, and fly to the moon before the astonished eyes of a jailer. If she wishes, before the sun rises, the captain will know where the one he seeks is hidden.’

Isabella feared, on hearing these incoherent sentences, that madness troubled Chiquita’s weak brain; but the child’s countenance was so perfectly calm, her eyes held so lucid a look, and the sound of her voice such an accent of conviction, that the supposition was inadmissible; surely this strange creature possessed some part of the almost magical powers which she attributed to herself.

As if to convince Isabella that she was not boasting, Chiquita said: ‘I will leave in a moment; let me think how to find a way; don’t speak, hold your breath; the slightest noise distracts me; I must listen to the Spirits.’

Chiquita tilted her head, put her hand over her eyes to isolate herself, remained deathly still for a while, then she raised her head, opened the window, climbed onto the sill, and gazed into the darkness with profound intensity. The dark water of the moat, stirred by the night breeze, lapped at the foot of the wall.

— ‘Will she, truly, take flight like a bat?’ the young actress said to herself, following Chiquita’s every movement with an attentive eye.

Opposite the window, on the far side of the moat, stood a large tree, several hundred years old, whose main branches extended almost horizontally, half over the ground, half over the water of the moat; but the end of the longest branch was eight or ten feet short of the castle wall. It was on this tree that Chiquita’s plan for escape was based. She retreated to the room, took from one of her pockets a very fine, tightly-coiled cord woven of horsehair, measuring twelve yards or more, and unrolled it, methodically, on the floor; took from another pocket a sort of iron hook which she attached to the rope; then she approached the window, and cast the hook into the branches of the tree. At the first attempt the iron failed to bite and, along with the rope, it fell back, clattering on the stones of the wall. On the second try, the hook’s claw pierced the bark, and Chiquita pulled the rope towards her, asking Isabella to pull on it with all her weight. The hanging branch gave way as much as the flexibility of the trunk allowed, and its tip drew five or six feet closer to the window. Then Chiquita tied the cord to the window’s ironwork with a knot that would not slip and, raising her wiry body with singular agility, she hung from the rope with both hands, and by shifting her wrists soon reached the branch which she straddled as soon as she felt its solidity beneath her.

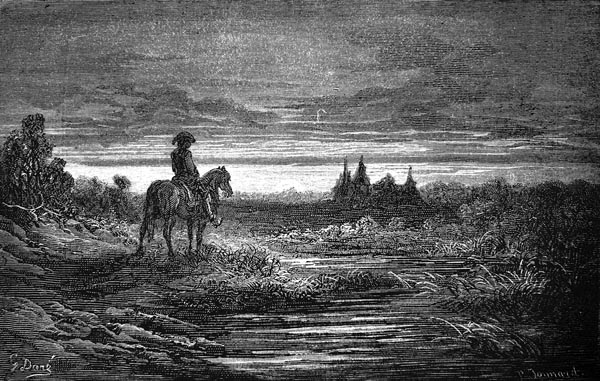

— ‘Now undo the knot, so I can pull it towards me,’ she said to the prisoner in a low but distinct voice, ‘unless you feel like following me; but fear would fill your head, and vertigo drag at your feet and make you fall into the water. Farewell! I’m off to Paris, but I’ll be back soon. One moves swiftly by moonlight.’

Isabel obeyed, and the branch, no longer restrained, resumed its usual position, bearing Chiquita to the other side of the ditch. In less than a minute, using her knees and hands, she found herself at the bottom of the trunk, on firm ground, and soon the captive saw her move away at a quick pace and disappear into the bluish shadows of the night.

Everything that had just happened seemed like a dream to Isabella. In a kind of stupor, having not yet closed the window, she gazed at the motionless tree, the black outlines of whose skeleton were outlined against the milky grey of a cloud penetrated by a diffuse light from the moon’s disc which it half hid. She shuddered at seeing how frail at its tip the branch was to which the courageous and light-hearted Chiquita had not feared to confide herself. She was moved by the thought of the attachment shown by this poor, wild and wretched being whose eyes were so beautiful, luminous and passionate, the eyes of a woman in a child’s face, and who showed so much gratitude for that paltry gift of hers. As the cool air seized her, and made her pearly teeth chatter feverishly, she closed the window, drew back the curtains, and settled herself in an armchair by the fire, her feet resting on the copper spheres of the andirons.

She had barely seated herself when the butler entered, followed by the same two servants as before carrying a small table covered with a rich, fringed tablecloth, on which a supper was served, no less fine and delicious than the dinner. A few minutes earlier, the entrance of these footmen would have thwarted Chiquita’s escape. Isabel, still agitated by that moving scene, left the dishes placed before her untouched, and signalled that they should be taken away. But the butler had a plate of blancmanges and marzipans placed near the bed; he also spread a robe, nightcap, and nightgown, all trimmed with lace and of the finest design, on an armchair. Enormous logs were thrown onto the crumbling embers, and the candles were renewed. This done, the butler told Isabel that if she needed a maid to assist her, one would be sent to her. The young actress having made a gesture of dismissal, the butler left, with the most respectful bow in the world.

Once the butler and the footmen had withdrawn, Isabella, having thrown the robe over her shoulders, went to bed fully-dressed without getting between the sheets, so as to be ready to rise quickly in case of an alarm. She took Chiquita’s knife from her bodice, opened it, locked the ferrule, and placed it near her within reach of her hand. These precautions taken, she lowered her long eyelids desiring to sleep, but sleep was hard to come by. The events of the day had agitated Isabella’s nerves, and the apprehensions of the night were hardly designed to calm them. Besides, those ancient châteaux, no longer inhabited, have, during the dark hours, singular physiognomies; it seems that some being or other has been disturbed, that an invisible guest retreats at one’s approach, into some secret corridor hidden in the walls. All sorts of small, inexplicable noises occur, unexpectedly. A piece of furniture creaks, a deathly hand seems to strike the woodwork sharply, a rat passes behind the curtain, a log riddled with woodworm bursts in the fire like a roasted chestnut and wakes one from a trance just as one is about to doze off. This is what happened to the young prisoner; she would sit up, frightened, open her eyes, look around the room, and, seeing nothing unusual, would rest her head on the pillow again. However, sleep finally overcame her, isolating her from the real world, the rumours from which no longer reached her. Vallombreuse, if he had been there, would have been free to pursue his reckless amorous enterprises; for fatigue had overcome modesty. Fortunately for Isabella, the young duke had not yet arrived at the château. Did he no longer care about his prey, now prisoned in his lair, and had the possibility of satisfying his whim quenched it? Not at all; the will of that handsome and wicked duke was more tenacious than ever, especially the will to do evil; for he felt, apart from voluptuousness, a certain perverse pleasure in flouting all divine or human law; but, so as to divert suspicion, on the very day of the abduction he had shown himself at Saint-Germain, had paid court to the king, followed the hunt, and, unemotionally, spoken to several people. That evening, he had gambled and openly lost sums that would have been significant for someone less wealthy. He had seemed in a charming mood, especially after a confidant had entered with a sombre face, bowed, and handed him a letter. His need to establish, in the event of an investigation, an incontestable alibi had safeguarded Isabella’s virtue that night.

After a slumber punctuated by strange dreams, in which sometimes she saw Chiquita running, waving her arms like wings, in front of Captain Fracasse on horseback, and sometimes the Duke of Vallombreuse with blazing eyes full of love or hatred, Isabella awoke and was surprised at how long she had slept. The candles had burned down to their sockets, the logs had been consumed, and a cheerful shaft of sunlight, penetrating the gap in the curtains, played freely over her bed, uninvited. The return of light was a great relief to the young woman. Her position, no doubt, was scarcely improved; but the danger was no longer magnified by the illusory fears that night and the unknown arouse in the steadiest minds. However, her joy was not long-lasting, for a creaking of chains was heard; the drawbridge was lowered: the sounds of the wheels of a carriage drawn at a brisk pace echoed from the bridge’s platform, rumbled beneath the vault like a dull thunder, and died away in the inner courtyard.

Who could be entering in so haughty and magisterial a manner if not the lord of the place, the Duke of Vallombreuse himself? Isabella felt from these sounds, warning the dove of the hawk’s presence though as yet he was invisible, that it was indeed the enemy, and none other. Her beautiful cheeks became pale as virgin wax, and her poor little heart began to beat wildly behind the fortress of her bodice, though without thought of surrender. Soon, making an effort to calm herself, the brave girl gathered her wits and prepared to defend herself. ‘If only,’ she said to herself, ‘Chiquita arrives in time, and brings help’; and her eyes involuntarily turned towards the portrait medallion above the fireplace: ‘O you, who have such a good and noble air, protect me against the insolence and perversity of your descendant. Let not this place in which your image shines witness my dishonour!’

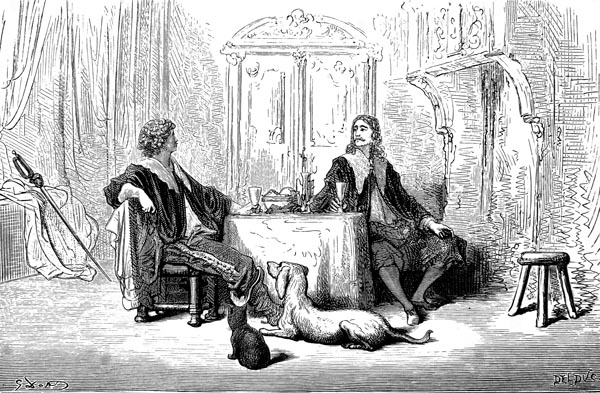

After an hour, which the young duke had spent repairing the disorder that a quick journey always brings to a toilette, the butler entered Isabella’s chamber, and, ceremoniously, asked her if she would receive the Duke of Vallombreuse.

— ‘I am but a prisoner,’ replied the young woman with dignity. ‘My answer is no freer than my person, and this request, which would be polite in an ordinary situation, is only derisory in the state I in which I find myself. I have no means of preventing Monsieur the Duke from entering this room which I cannot leave. I do not accept his visit; I submit to it. It is a case of force-majeure. Let him enter if he pleases, at this hour or at another: it is all the same to me. Go and repeat my words to him.’

The butler bowed, retreated backwards towards the door, for he had been instructed to show the greatest respect towards Isabella, and disappeared to inform his master that ‘Mademoiselle’ agreed to receive him. After a few moments the butler reappeared, and announced the Duke of Vallombreuse.

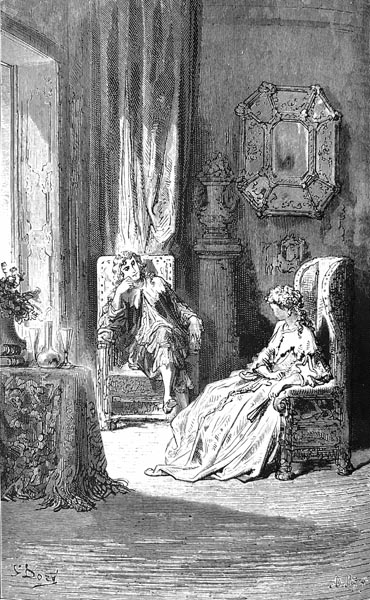

Isabella had half-risen from her armchair, into which emotion made her retreat, covered with a deathly pallor. Vallombreuse advanced towards her, hat in hand, in an attitude of the deepest respect. As he saw her start at his approach, he stopped in the middle of the room, bowed to the young actress, and said to her in that voice which he knew how to sweeten so as to seduce:

— ‘If my presence is too odious to the charming Isabella at the moment, and she requires some time to become accustomed to the idea of seeing me, I will withdraw. She is my prisoner, but I am no less her slave.’

— ‘Such courtesies arrive tardily,’ replied Isabella, ‘after the violence you have employed against me.’

— ‘That is the result,’ the duke continued, ‘of driving people to the limit with too fierce a show of virtue. Denied hope, they resort to extreme measures, knowing that such cannot worsen their situation. If you had been willing to allow me to pay court to you, and shown some indulgence to my suit, I would have remained among the ranks of your adorers, trying, by dint of delicate gallantry, amorous magnificence, chivalrous devotion, ardent and restrained passion, to slowly soften your rebellious heart. I would have inspired you, if not with love, at least with that tender pity which sometimes precedes it and inspires it. In the long run, perhaps, your coldness would have seemed unjust, for nothing would have induced me to wrong you.’

— ‘If you had employed honest means,’ said Isabella, ‘I would have pitied a love that I could not share, since my heart could never yield itself, and at least I would not have been forced to hate you, a feeling that is not familiar to my soul, and which it is painful for me to experience.’

— ‘Then, you hate me so greatly?’ said the Duke of Vallombreuse, his voice quivering with spite. ‘Yet I have not deserved it. My wrongs towards you, if any, derive from my passion alone; and what woman, however chaste and virtuous she may be, seriously resents in a gallant man the effect that her charms have produced on him despite herself?’

— ‘Certainly, there is no reason for aversion when the lover keeps himself within the bounds of respect, and sighs away with discreet timidity. The most prudish can bear it; but when his insolent impatience gives way at the outset to the last excess, and proceeds by way of ambush, kidnapping, and sequestration, as you have not feared to proceed, there is no other possible feeling than unconquerable repugnance. Any soul, though the least haughty and proud, rebels when one tries to force it. Love, which is a divine thing, cannot be commanded or extorted. It arises where it wishes.’

— ‘So, unconquerable repugnance, is all I may expect from you,’ replied Vallombreuse, whose cheeks had grown pale and who had bitten his lips more than once as Isabella spoke to him with that gentle firmness which was the natural tone of that young person, as sensible as she was amiable.

— ‘You have a way to regain my esteem and win my friendship. Grant me the freedom you have robbed me of. Have me borne by carriage to my anxious companions who do not know what has become of me, and are desperately searching for me, in mortal fear. Let me resume my humble life as an actress before this venture, from which my honour would suffer if it became known amongst a public astonished by my absence.’

— ‘What misfortune,’ cried the duke, ‘that you should ask me for the one thing I cannot give you without betraying myself! If you desired but an empire, a throne, I would grant it; a star, I would go and seek it for you, by mounting into the heavens. But you wish me to open the door of this cage to which you would never return once you had left. Impossible! I find that you love me so little that I have no other way to see you other than to imprison you. Whatever the cost to my pride, I employ that means; for I can no more do without your presence than a plant can do without the light. My mind turns to you as to its sun, and it is as night for me where you are not. If what I have risked is a crime, I must at least profit by it, for you would refuse to forgive, whatever you say. Here, at least, I hold you, I surround you, I envelop your hatred with my love, I breathe on your cold icy wastes the warm breath of my passion. Your eyes are forced to reflect my image, your ears to hear the sound of my voice. Something of myself insinuates itself into your soul despite you; I act upon you, if only by the terror I cause you, for the sound of my footsteps in the antechamber made you shudder. And then, this captivity separates you from that person you regret, and whom I abhor for having seduced the heart that should have been mine. My jealousy, sated, revolves around this small happiness, and will not risk it by granting you a freedom you would use against me.’

— ‘And how long,’ said the young woman, ‘do you intend to hold me in seclusion, acting like a Barbary corsair not a Christian lord?’

— ‘Until you love me, or tell me so, which amounts to the same thing,’ replied the young duke with perfect seriousness, and the most assured air in the world. Then he bowed, most graciously, to Isabella, and made his exit, smoothly, like a true courtier whom no situation embarrasses.

Half an hour later, a footman brought her a bouquet, an assemblage of the rarest flowers, of blended colours and perfumes; though, all were rare at that time of year, and it had taken all the talent of the gardeners and the artificial climate of the greenhouses to induce these charming daughters of Flora to bloom so early. The stem of the bouquet was clasped by a magnificent bracelet, worthy of a queen. Among the flowers, a sheet of white paper folded in two attracted her eye. Isabella opened it roughly, for in her situation, these small details of gallantry no longer had the significance they would have had if she had been free.

It was a note from Vallombreuse, written in the following terms, in bold handwriting consistent with the character of its author. The prisoner recognised the hand that had written ‘For Isabella’ on the jewellery box left in her room in Poitiers:

— ‘Dear Isabella, I send you these few flowers, although I am certain they will be poorly received. Coming from me, their freshness and novelty will find small favour in the face of your unparalleled rigor. But, whatever their fate, and even if you only choose to cast them from the window as a sign of your vast disdain, they will force, by your very anger, your mind to pause for a moment, if only to curse the one who declares himself, in spite of everything, your stubborn admirer.

Vallombreuse.’

This elegant note of gallantry, which nonetheless revealed in he who had written it a formidable tenacity, which nothing could dispel, produced, in part, the effect that the duke had promised himself. Isabella held it in her hand with a gloomy air, and the figure of Vallombreuse presented itself to her mind in a diabolical manner. The perfumes of the flowers, most of them not native to France, placed near her, on the pedestal table, by the footman, were enhanced by the room’s warmth, and their exotic aromas spread through the air, powerful and dizzying. Isabella took them, and placed them in the antechamber, without removing the diamond bracelet which surrounded the stems, fearing that the flowers were impregnated with some subtle philtre, narcotic, or aphrodisiac, calculated to trouble her reason. Never were lovely blooms mistreated more, and yet Isabella loved such things greatly; but she feared that if she were to keep them, the duke’s conceit would take advantage of the fact; and besides, these plants with their bizarre shapes, strange colours, and perfumes unknown to her, lacked the modest charm of common flowers; their proud beauty recalled that of Vallombreuse, and resembled him too much.

She had barely set the forbidden bouquet on a sideboard in the next room, and seated herself once more in her armchair, when a chambermaid appeared to assist her in dressing. This girl, quite pretty, very pale, and with a sad and gentle air, was somehow inert in manner, seemingly subdued by secret terror, or a dreaded influence. She offered her services to Isabella, almost without looking at her, and in a toneless voice as if she feared being heard by the walls themselves. At an affirmative sign from Isabella, she combed the latter’s blond hair, which was in disarray following the violence of the previous evening, and the nervous anxieties of the night, tied her silky curls with velvet bows, and relinquished her work like a hairdresser who knows her trade. She then took from a wardrobe, set in the wall, several dresses of rare richness and elegance, which seemed tailored to Isabella’s measurements, but which the young actress refused, even though hers was faded and wrinkled, since she would have appeared to be wearing the Duke’s livery, and her formal intention was to accept nothing from him, even if her captivity were to last longer than she hoped.

The chambermaid did not insist, and respected her whim, since condemned persons are allowed to do what they wish within the confines of their prison. It was also as if she avoided becoming intimate with her temporary mistress, for fear of taking an unnecessary interest in her. She reduced herself as much as possible to the state of an automaton. Isabella, who thought she might gain some insight from her, understood that it was superfluous to question her, and abandoned herself to her silent attentions, not without a kind of dread.

When the maid had retired, dinner appeared, and despite the sadness of her situation, Isabella did honour to it; nature imperiously demands its rights even in the most delicate of people. This refreshment gave her the strength she sorely needed, her own being exhausted by her emotions and the assaults upon her. With her mind a little calmer, the prisoner began to think of Sigognac, who had behaved so valiantly, and though alone would have snatched her from her kidnappers, if he had not lost time unravelling himself from the cloak thrown over him by the blind traitor. He must surely have heard news by now, and there was no doubt that he would rush to the defence of the one he loved more than his life. At the thought of the dangers to which he was about to expose himself in this perilous undertaking, for the duke was not a man to let go of his prey without resistance, Isabella’s breast swelled with a sigh and a tear rose from her heart to her eyes; she blamed herself for being the cause of such conflict, and almost cursed her own beauty, as the origin of this evil. However, she was modest, and had not sought, out of coquetry, to excite the passions around her, as many actresses, and even great ladies or members of the bourgeoisie do.

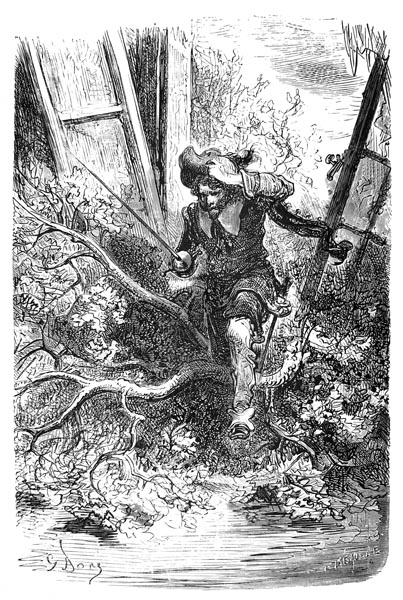

She was lost in reverie, when a brief but sharp knock sounded at the window, a pane of which was starred, as if it had been struck by a hailstone. Isabella approached the window, and saw Chiquita, in the tree opposite her, who signalled mysteriously to her to open the window, while swinging the cord equipped with that iron claw. The actress understood the child’s intention, obeyed her gesture, and the device, thrown with a sure hand, bit into the balcony support. Chiquita tied the other end of the rope to the branch, and hung from it as she had the day before: but she was scarcely halfway across, when the knot came undone, to Isabella’s great fright, and the rope detached itself from the tree. Instead of falling into the green waters of the moat, as might have been feared, Chiquita, whose presence of mind was untroubled by the accident, if it was one, swung forward on the rope fastened to the balcony by the iron claw, and hung flat against the wall of the castle, beneath the window, which she soon reached, employing her hands and feet pressed hard against the stone. Then she climbed over the balcony, and leapt down lightly into the room. Seeing Isabella quite pale, and almost fainting, she said, with a smile:

— ‘You were scared; you thought Chiquita would join the frogs in the ditch. I only tied a slipknot about the branch so I could pull the rope towards me. At the end of that black line, thin and brown as I am, I must have looked like a spider climbing back up its thread.’

— ‘Little one,’ said Isabella, kissing Chiquita on the forehead, ‘you are a dear, brave and courageous child.’

— ‘I found your friends, they were looking for you; but without Chiquita, they would never have discovered your retreat. The captain was pacing back and forth like a lion; his hair was steaming, his eyes flashing. He set me on his saddlebow, and now he is hidden in a small wood not far from the castle with his comrades. They dare not show themselves. Tonight, as soon as darkness falls, they will attempt your rescue; there will be sword thrusts and pistol volleys. It will be superb. Nothing is as fine as men fighting; but don’t be scared or scream. A woman’s screams would lessen their courage. If you wish, I’ll stay with you to reassure you.’

— ‘Worry not, Chiquita, I’ll not trouble with foolish fears the brave friends who risk their lives to save me.’

— ‘That’s good’ the girl continued; ‘defend yourself if you need to, until this evening, with the knife I gave you,. The blow must be struck from below, upwards. Don’t forget. As for me, we must not be seen together, so I’m off to seek some place where I can sleep. Above all, don’t look out of the window, it might arouse suspicion by suggesting you’re waiting for help from that quarter. Then they’d conduct a search around the castle and discover your friends. The attempt would be a failure, and you would remain in the power of this Vallombreuse whom you hate.’

— ‘I’ll not go near the window, I promise you,’ replied Isabella, ‘however curious I might feel.’

Reassured on that important point, Chiquita disappeared and went to join the swordsmen in the lower room who, drowned in drink, and weighed down like beasts by sleep, had not even noticed her absence. She leant against the wall, clasped her hands on her breast, which was her favourite position, closed her eyes and was soon asleep; for her doe’s feet had travelled more than twenty miles the previous night, between Vallombreuse and Paris. The return on horseback, at a pace she was unaccustomed to, had perhaps tired her more. Although her wiry body had the strength of steel, she was exhausted, and her sleep was so profound that she seemed dead.

— ‘How prone to sleep children are!’ said Malartic, who had finally awakened. ‘In spite of our bacchanal, she takes a nap! Hey! You amiable brutes, try standing on your hind legs, go to the courtyard, and each of you pour a bucket of cold water over his head. The Circe named Drunkenness has made pigs of you (see Homer’s Odyssey, Book X); turn yourselves back into men again by means of that baptism, and then we’ll do the rounds and see if anything is planned on behalf of this beauty, with whose guardianship and defence Lord Vallombreuse has entrusted us.’

The swordsmen rose, heavily, and departed, in order to comply with the wise instructions of their leader, though not without wandering a little between the table and the door. When they had more or less regained their wits, Malartic, taking Tordgueule, Piedgris and La Râpée, with him, went towards the postern, and unbolted the padlock which held the chain mooring the boat to the water-door of the kitchen. The boat, driven forward by a pole, after cleaving the glaucous mantle of duckweed, soon landed at a narrow staircase cut into the embankment of the moat.

— ‘You stay here,’ Malartic said to La Râpée, once his men had clambered up, ‘and guard the boat, in case the enemy tries to seize it, and enter. Besides, you don’t look too firm on your feet. The rest of us will patrol around and beat the bushes a little, to make the birds fly away.’

Malartic, followed by his two acolytes, circled about the château for more than an hour, without encountering anything suspicious. On returning to their starting point, he found La Râpée asleep, standing, but leaning against a tree.

— ‘If we were regular troops,’ he said, waking him with a blow of his fist, ‘I’d have you shot for napping on sentry duty, something contrary to all good martial discipline; but since we are not, I pardon you and only sentence you to drink a pint of water.’

— ‘I'd rather have a pair of bullets in my brain than a pint of water in my stomach,’ replied the drunkard.

— ‘A fine answer,’ said Malartic, ‘and worthy of a Plutarchan hero. Your fault is forgiven, go unpunished, but sin no more.’

The patrol returned, and the boat was carefully moored and padlocked, with all the precautions customary in a stronghold. Satisfied with his inspection, Malartic said to himself: ‘If the charming Isabella can escape, or the valiant Captain Fracasse enter, for both cases have been foreseen, may my nose turn white and my cheeks red.’

Left alone, Isabella had opened a volume of Monsieur Honoré d’Urfé’s L’Astrée, which was lying forgotten on a console table. She tried to focus her thoughts on her reading. But her eyes, alone, followed the lines mechanically. Her mind flew far from the pages, unable to identify for a moment with its now-outdated shepherdesses. Bored, she threw down the volume, and folded her arms, awaiting events. By dint of conjecturing, she had grown tired of the process, and without trying to guess how Sigognac would deliver her, she counted on the absolute devotion of that gallant fellow.

Evening came. The footmen lit the candles, and soon the butler appeared announcing a visit from the Duke of Vallombreuse. He entered on the heels of his valet, and greeted his captive with the most perfect courtesy. He was, in truth, supremely handsome and elegant. His charming face was fit to inspire love in every unprejudiced heart. A jacket of pearl-grey satin, crimson-velvet breeches, pale-leather cauldron boots trimmed with lace, and a silver-brocade sash supporting a sword with a jewelled pommel, highlighted the advantages of his person wondrously well, and it required all of Isabella’s virtue and constancy not to be impressed by his appearance.

— ‘I visit you, my adorable Isabella,’ he said, seating himself in an armchair close to the young woman, ‘to see if I will be better received than my bouquet; I am not so conceited as to believe so, but I wish you to become accustomed to my presence. Tomorrow, a fresh bouquet and a further visit.’

— ‘Both your bouquets and your visits will prove useless,’ Isabella replied, ‘it may seem impolite to say so, but my sincerity leaves you no hope.’

— ‘Well,’ said the duke, with a gesture of haughty indifference, ‘I shall forego all hope, and be content with the reality. You do not know, poor child, what Vallombreuse is, you who try to resist him. Never has a desire unfulfilled entered his soul; he pursues what he longs for, and nothing can sway or divert him: neither tears nor supplications, nor cries, nor corpses, nor smoking ruins obstructing his path; a universal collapse would not surprise him, for on the ruins of the world he would fulfil his whim. Be not the woman impossible of approach, who swells his passion, imprudently encouraging the tiger to scent the presence of the lamb, then driving him away.’

‘Both your bouquets and your visits will prove useless.’

Isabella was frightened by the change in Vallombreuse’s expression as he spoke these words. His gracious look had vanished. Nothing remained but cold malice, and implacable resolution. With an instinctive movement, Isabella drew back her chair, and reached up to feel Chiquita’s knife at her bosom. Vallombreuse moved his chair closer, without affectation. Controlling his anger, he had already reassumed that charming, playful, and tender air which had hitherto proved irresistible.

— ‘Accommodate yourself to what is; cease to look back towards a life that must henceforth appear but a forgotten dream. Forego this obstinate and fanciful loyalty to a love languishing and unworthy of you, and reflect that in the eyes of the world you will be mine from henceforth. Consider above all that I adore you with a passion, a frenzy, a delirium no woman has ever before inspired in me. Seek not to escape the flames that envelop you, an inescapable will that nothing can deflect. Like cold metal thrown into the crucible in which molten iron is already seething, your indifferent self, drowned by my passion, will melt, and amalgamate therein. Whatever the future, you must love me, either willingly, or through force, because that is my wish, because you are young and beautiful, and I am young and handsome. Resist, you may, but, despite your struggles, you will fail to free yourself from the arms that close about you. Therefore, resistance is merely ungracious, since it will but prove in vain. Resign yourself, with grace and a smile; is it so great a misfortune, after all, to be loved, and desperately so, by the Duke of Vallombreuse? A misfortune that would render more than one person happy.’

While he was speaking with that warm ardour that conquers a woman’s reason, and overcomes her modesty, but which on this occasion had scant effect, Isabella, attentive to the slightest noise without, from whence her deliverance must come, thought she heard a small, almost imperceptible noise on the far side of the moat. It sounded dull, and rhythmic, like the sound of repeated efforts directed, cautiously, against some obstacle. Fearing that Vallombreuse would note it, the young woman replied in such a way as to wound the proud conceit of the young duke. She preferred him in a state of irritation to one of amorous affection, and preferred his outbursts to his tenderness. She hoped, moreover, by quarrelling with him, to prevent him from hearing.

— ‘Such happiness, she said, ‘would shame me, one that I would escape by death if I lacked all other means. You will never gain anything from me but my corpse. You fill me with indifference; I hate you for your outrageous, violent, and infamous conduct. Yes, I love Sigognac, whom you have sought, several times, to assassinate, have you not?’ The furtive sounds had continued, and Isabella, no longer sparing herself, had raised her voice to hide them.

At these audacious words, Vallombreuse turned pale with rage, his eyes flashed viperous glances; a light foam frothed at the corners of his lips; he convulsively raised his hand to the hilt of his sword. The idea of killing Isabella had flashed through his mind; but, by a prodigious effort of will, he restrained himself and began to laugh, in a shrill, fraught tone, as he advanced towards the young actress.

— ‘By all the devils,’ he cried, ‘you please me so; when you insult me, your eyes take on a particular brightness, your complexion a supernatural radiance; your beauty is redoubled. You do well to speak frankly. Restraint bores me. Ah! You love Sigognac! So much the better! It will be sweeter still, for me to possess you. What a pleasure to kiss those lips that say: ‘I abhor you!’ Far more stimulating than thet eternal and insipid ‘I love you,’ with which women so disgust us.’

Fearful of Vallombreuse’s resolution, Isabella rose, and slid Chiquita’s knife from her corset.

— ‘Excellent!’ said the duke, seeing the young woman armed, her dagger already freed. ‘If you knew anything of Roman history, my dear, you would recall that Lucretia used her dagger only after the attempt on her by Sextus, the son of Tarquinius Superbus. That example from antiquity is a good one to follow.’

And as indifferent to the blade as he would have been to a bee’s sting, he advanced on Isabella, seizing her in his arms before she had time to raise the knife.

At that very moment, a crack was heard, followed promptly by a loud crash, and the window, as if it had suffered a blow from the knee of a giant, fell, midst a din of pulverised glass, into the room, as a mass of branches, catapulted downward and forward to act as a flying bridge, penetrated loudly.

Here was the tree’s crown that had facilitated Chiquita’s exit and re-entry. The trunk, sawn through by Sigognac and his comrades, had yielded to the law of gravity. Spanning the water, its fall had been so directed as to link the bank of the moat to Isabella’s window.

Vallombreuse, surprised by this sudden irruption, which cut short his assault, released the young actress and, sword in hand, stood ready to receive the first person who presented himself.

Chiquita, who had entered on tiptoe, light as a shadow, pulled Isabella by the sleeve, and said to her: ‘Take shelter behind this piece of furniture, the dance is about to begin.’

The girl was speaking no less than the truth, for a flurry of shots rang out in the nocturnal silence. The garrison had discovered the attack.

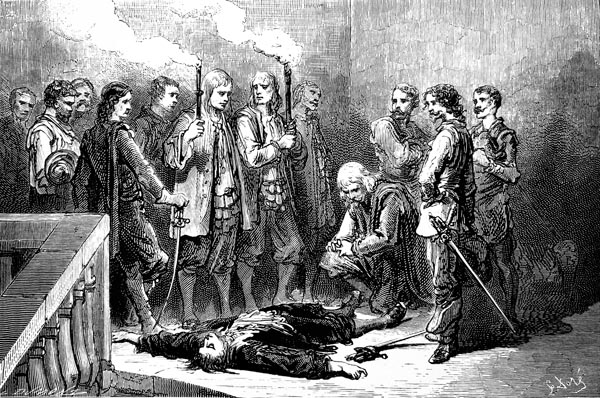

Chapter XVII: The Amethyst Ring

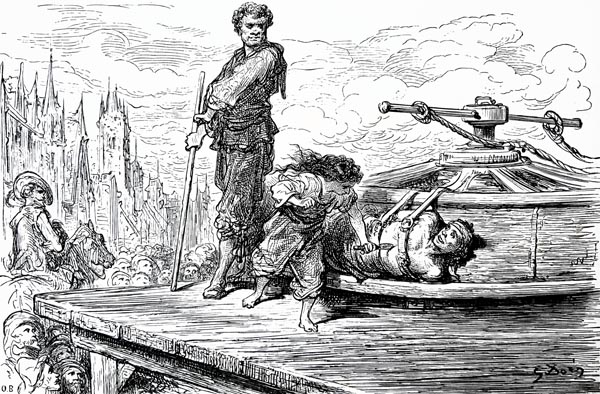

Climbing the steps four at a time, Malartic, Bringuenarilles, Piedgris and Tordgueule rushed to Isabella’s room to bring aid to Vallombreuse, and defend him, while La Râpée, Mérindol and the Duke’s usual swordsmen, whom he had brought with him, used the boat to cross the moat so as to attempt a sortie, and take the enemy in the rear. A clever strategy, worthy of a sound army general!

The tree’s top branches, blocking the window-opening which was quite narrow, extended almost to the middle of the room; it was therefore impossible to present a sufficiently wide front to the enemy. Malartic lined up with Piedgris against the wall, on one side, and ordered Tordgueule and Bringuenarilles to the other, so that they would avoid the initial fury of the attack, and possess a greater advantage. Before entering the room, it was therefore necessary to pierce this menacing line of soldiers waiting with sword in one hand and pistol in the other. All had replaced their masks, for none of those honest people cared to be recognised in case the affair turned out badly, and they made for rather a frightening sight, that quartet of faces clad in black, motionless, and silent as ghosts.

— ‘Withdraw, or conceal yourself,’ Malartic murmured in a low voice to Vallombreuse, ‘it is needless for you to be seen in this encounter.’

— ‘What matter?’ replied the young duke. ‘I fear no one in the world, and those who have seen me will not live to speak of it,’ he added, waving his sword in a threatening manner.

— ‘At least take Isabella, the Helen of this new Trojan War, to another room, since a stray bullet might spoil your plan, which would be a shame.’

The Duke, finding the advice judicious, advanced towards Isabella, who was sheltering with Chiquita behind an oak chest, and seized her in his arms, though she clung with clenched fingers to the sculpted projections on its sides, and vigorously resisted Vallombreuse’s efforts; the virtuous girl, overcoming her timidity, preferred to remain on the battlefield, exposed to bullets, and sword-thrusts which at worst could only end her life, to being alone with Vallombreuse, protected from the fight, but exposed to an assault which would shame her honour.

— ‘No, no, leave me,’ she cried, struggling, and desperately gripping the doorframe, for she knew Sigognac could not be far away. At last, the duke, having succeeded in half-opening the door, was about to drag Isabella into the next room, when the young woman freed herself from his hands, and ran towards the window; but Vallombreuse caught hold of her again, lifted her from the ground, and bore her to the rear of the apartment.

— ‘Save me,’ she cried, in a weak voice, feeling at the end of her strength, ‘save me, Sigognac!’

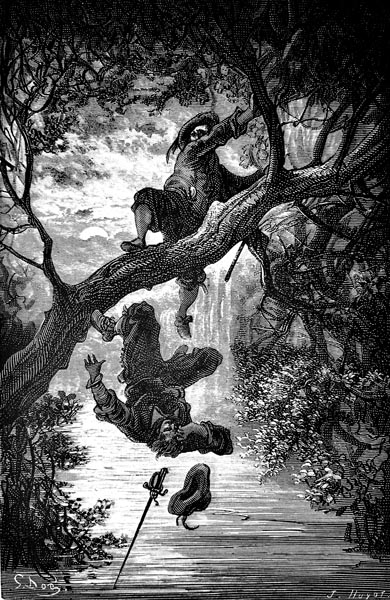

A rustling amidst the tree-branches was heard, a loud voice that seemed to fall from heaven cried: ‘Here I am!’ and, a dark shadow passed swiftly between the twin pairs of swordsmen, driven by such momentum, that it was already in the middle of the room, when four pistol shots rang out almost simultaneously. Clouds of smoke spread in dense patches that for a few seconds hid the result of this quadruple fire. When they had dissipated a little, the swordsmen saw Sigognac, or, to be more accurate, Captain Fracasse, since they only knew him by that name, standing upright, sword in hand, and with no harm done, but the feather in his felt hat trimmed, the discharge from their wheel-lock pistols not having been achieved swiftly enough, nor his foes able to aim accurately enough, for their bullets to find him in a passage as unexpected as it was rapid. But Isabella and Vallombreuse were no longer there. The duke had taken advantage of the tumult to carry off his half-fainting prey. A solid and bolted door, stood between the poor actress and her generous defender, already hindered by the quartet on hand. Happily, Chiquita, lively and supple as a snake, seeking to be of use to Isabella, had slipped through the half-open door, in the footsteps of the Duke, who, amidst the chaos of violent action, and the crackle of firearms, failed to notice her, especially since she instantly hid in a dark corner of the vast room, which was only dimly lit by a lamp placed on a sideboard.

— ‘You wretches,’ cried Sigognac, ‘where is Isabella? I heard her voice just now.’

— ‘We are not her keepers,’ replied Malartic with the greatest composure in the world, ‘nor are we cut out to play the role of duenna.’

With that, he fell upon the Baron with sword raised high, the latter countering him in fine style. Malartic was not an adversary to be disdained; he was considered, after Lampourde, the most skilful gladiator in Paris, but he was not a strong enough swordsman to fight with Sigognac for long.

— ‘Guard the window, while I deal with this fellow,’ he shouted, as he fought, addressing Piedgris, Tordgueule and Bringuenarilles, who were hastily reloading their pistols.

At the same moment, a new assailant burst into the room. It was Scapin, whose former professions, of acrobat and soldier, had developed in him a singular facility for this sort of siege warfare. With a quick glance, he saw that the swordsmen’s hands were occupied in reloading their weapons with powder and bullets, while they had laid their swords beside them; as swift as lightning, he took advantage of that moment of uncertainty in the ranks of his enemies, astonished by his sudden entrance, to gather their rapiers and hurl them through the window; then he ran towards Bringuenarilles, seized him by the body, and employing his foe as a shield, he thrust him before him, turning him so as to present his face to the muzzles of the pistols pointed at him.

— ‘By all the devils, don’t shoot,’ cried Bringuenarilles, half-suffocated by Scapin’s wiry arms, ‘don't shoot. You’ll strike my chest or my head, and it would go hard to be slain by my comrades.’

So as not to give Tordgueule and Piedgris the opportunity of firing at his rear, Scapin prudently backed against the wall, using Bringuenarilles as a defence; and, in order to spoil their aim, shoved the swordsman here and there, who, though his feet sometimes touched the ground, failed to regain fresh strength as Antaeus did (in the Greek myth).

The manoeuvre was most judicious; for Piedgris, who thought little of Bringuenarilles, and cared not a straw about killing a man, even if he was his companion, aimed at Scapin’s head, who was a fraction taller than the swordsman before him; the shot sped true, but the actor had bent forward, raising Bringuenarilles to protect himself, and the bullet pierced the woodwork, after striking the latter and removing the ear of the poor devil, who began to shout: ‘I’m killed! I’m killed!’ with a vigour that proved him very much alive.

Scapin, who was in no mood to wait for a second pistol shot, knowing full well that the bullet might pass through the body of Bringuenarilles if the latter fell sacrifice to his merciless comrades, and could still wound him grievously, now employed the wounded man as a projectile, and thrust him so roughly against Tordgueule, who was advancing, with the barrel of his weapon lowered, that the pistol slipped from Tordgueule’s hand, while that swordsman rolled hither and thither on the floor beside his comrade, whose blood spurted in his face and blinded him. The fall had been so sudden that he remained stunned and bruised for several minutes, which gave Scapin time to kick the pistol under a piece of furniture, and raise his dagger to meet Piedgris, who was charging at him furiously, poniard in hand, enraged at having missed his shot.

Scapin bent down and, with his left hand, seized Piedgris’ wrist, and forced the arm that held the dagger upwards, while with his right hand, gripping his own knife, he dealt his enemy a blow that would certainly have slain him, had it not been for the thickness of his buff leather vest. The blade sliced it open and pierced the flesh, but was deflected by a rib. Although it was neither mortal, nor even dangerous, the wound surprised Piedgris and made him stagger; so that the actor, giving the arm he still held a sudden jerk, had no difficulty in knocking his enemy down, the latter already having collapsed on one knee. As an extra precaution, he hammered at his opponent’s head with his heel to make him stay completely still.

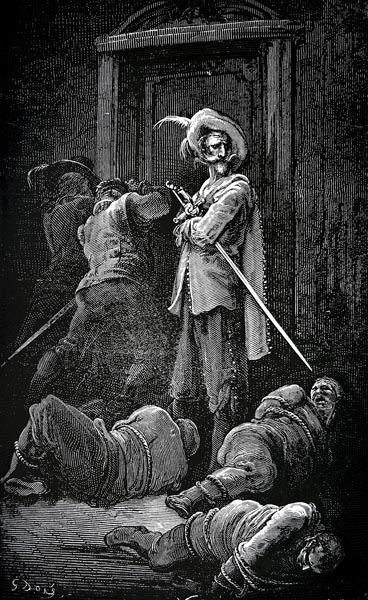

While all this was occurring, Sigognac, possessed of the cold fury of one whose profound knowledge of the art was at the service of great courage, was fencing with Malartic. He parried all the swordsman’s strokes, and had already grazed his arm, as evidenced by a sudden flush of crimson on Malartic’s sleeve. The latter, feeling that, if the fight continued, he was lost, resolved to make a supreme effort, and lunged fiercely, so as to deliver a direct blow to Sigognac. The two blades clashed with so sharp and rapid a movement that the shock caused sparks to fly; but the Baron’s sword, gripped in a fist of iron, drove aside the other’s arched sword. The point passed beneath Captain Fracasse’s armpit, scratching the fabric of his doublet without piercing. Malartic rose; but, before he could readopt his defensive stance, Sigognac knocked the rapier from his hand, placed his foot upon it, and raising his blade to Malartic’s throat, cried: ‘Surrender, or die!’

At this critical juncture, a solid figure, striding through the litter of branches, entered the heart of the battle, and the newcomer, seeing Malartic’s compromised position, said, in a tone of authority: ‘You may yield, without dishonour, to this valiant man; he has your life at the point of his sword. You have done your duty, loyally; consider yourself a prisoner of war.’

Then, turning to Sigognac: ‘Trust to his word,’ he said, ‘he is a gallant fellow in his own way, and will not attempt anything against you from here on.’

Malartic nodded, and the Baron lowered the point of his formidable rapier. As for the swordsman, he picked up his weapon with a rather pitiful air, replaced it in its scabbard, and seated himself silently in an armchair, where he clasped his handkerchief around his arm, on which the red blotch was widening.

‘…A solid figure, striding through the litter of branches…’

— ‘As for these others, who, if not dead, are more or less wounded,’ said Jacquemin Lampourde (for it was he), ‘it is best to make sure of them; we will, if you please, tie their legs as they do poultry borne upside down to market. Else they might leap up and bite, if only at our heels. They are pure scoundrels capable of pretending to be hors de combat, in order to spare their skin, which is however of little account.’

And, bending over the bodies lying on the floor, he pulled from his breeches various pieces of thin rope and with marvellous dexterity lashed together the feet and hands of Tordgueule, who pretended to resist, of Bringuenarilles, who began to utter cries like a lively plucked jay, and even of Piedgris, though the latter reacted no more than a corpse, the livid pallor of which he possessed

If the reader is surprised to behold Lampourde among the besiegers, I reply that the swordsman was possessed of a fanatical admiration for Sigognac, whose fine fencing style had so charmed him in their encounter on the Pont-Neuf, and that he had placed his services at the disposal of the captain; services which were not to be disdained in such difficult and perilous circumstances. It often happened, moreover, that in these hazardous enterprises, erstwhile comrades, being paid by opposing interests, met, with torch or dagger in hand, without it causing an issue.

Let it not be forgotten that La Râpée, Agostin, Mérindol, Azolan and Labriche, at the beginning of the attack, had left the castle, crossing over by boat, in order to create a diversion and fall upon the enemy’s rear. They had skirted the moat, silently, and arrived at the place where, detached from its base, the large tree-trunk crossed the water, serving both as a flying bridge, and a ladder for the liberators of the young actress. The noble Herod, as one may well imagine, had not failed to offer his services, brave as he was, to Sigognac, whom he prized highly and whom he would have followed to the very gates of Hell, even if it had not been dearest Isabella, beloved by the whole company, and by himself in particular, who was to be rescued. If he was not visible at the height of the battle, it was in no way due to cowardice; for he possessed as great a store of courage as the captain, even though he was merely an actor. He had straddled the tree, like the others, raising himself on his hands and arms, and shuffling forward at the expense of his breeches, the seat of which was frayed from the rough bark. In front of him, as best he could, slid the doorman of the comedy troupe, a determined fellow accustomed to using his fists, and countering the pressure of the crowd. The doorman, having reached the part where the branches forked, seized hold of a substantial one, and continued his ascent; but, having reached the same region, Herod, endowed with the corpulence of a Goliath, excellent for his role as Tyrant, but ill-suited to climbing, felt the branch bend beneath him, and crack in a disturbing way. He looked down and glimpsed in the shadows, about thirty feet below, the black waters of the moat. The prospect gave him thought, and he scrambled onto a more solid piece of wood, capable of supporting his body.

— ‘Hmm!’ he reflected, silently, ‘As wise for an elephant to dance on a spider’s thread as for me to risk my life on twigs a sparrow could bend. They might look fine to a lover, a Scapin, or some other agile creature obliged by their role to remain slim. A king and tyrant of comedy, more given to the table than to the ladies, I possess no such frivolous, acrobatic, tightrope-walking skill. If I make but one more move to go to the Captain’s aid, who must certainly need it, since I comprehend, from the pistol shots and the hammering of sword-blades, that the matter waxes hot, I will surely fall into that Stygian water, thick and black as ink, green with slimy plants, teeming with frogs and toads, sink into the mud up to my head, and meet an inglorious death, a fetid fate, a miserable and utterly profitless end, for I will have grieved the enemy not all. There is no shame in retreating. Courage here can do nothing. If I were Achilles, Roland or El Cid, I could not bring aid, weighing as I do two hundred and forty pounds and some ounces, and seated on a branch as thin as my little finger. It is no longer a matter of heroism but of physics. So, about-face; I will find a surreptitious way to enter the fortress, and prove useful to this brave Baron, who must presently doubt my friendship, if he has time to think of anyone or anything.’