Robert d'Orbigny

Floire and Blancheflor: Part II

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2023 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Floire attempts to slay himself.

- His mother reproves his action.

- She seeks the King’s agreement to a remedy.

- The queen confesses to her son.

- Floire swears to seek for Blancheflor everywhere.

- He asks leave of the king.

- And requests his support.

- Royal gifts are bestowed on the boy.

- Floire departs in search of Blancheflor.

- He and his company reach the port.

- The company dines, though Floire seems distracted.

- Floire hears news of Blancheflor.

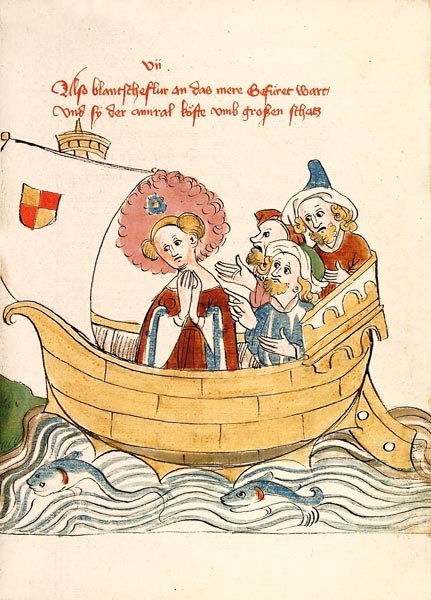

- He boards ship for Babylon.

- Floire hears of the feast to be held there.

- He sets sail with his company and reaches Baudas.

- He finds lodging there.

- Floire hears further news of Blancheflor.

- They take the road to Babylon and reach Monfelis.

- Floire hears that Blancheflor is in Babylon.

- They reach the river-bridge, and Babylon.

- Wisdom and Love debate within him.

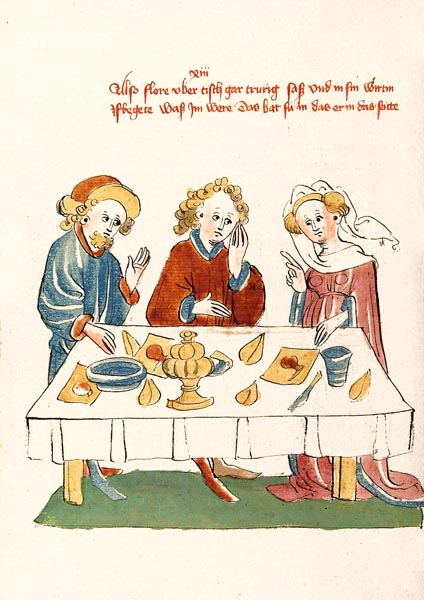

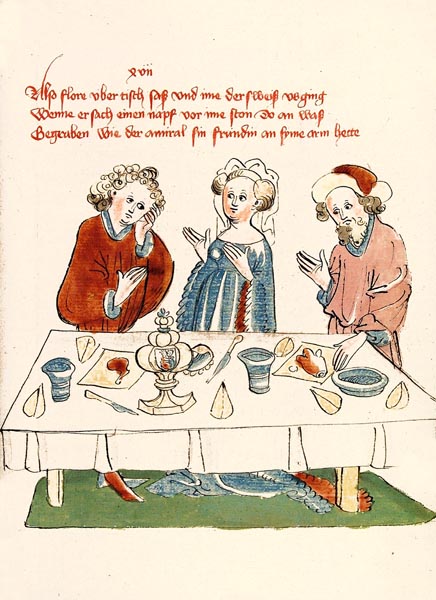

- Floire dines with the host and his wife.

- His pensiveness and sadness is perceived.

- Floire hears yet again of Blancheflor.

- He confesses the nature of his quest.

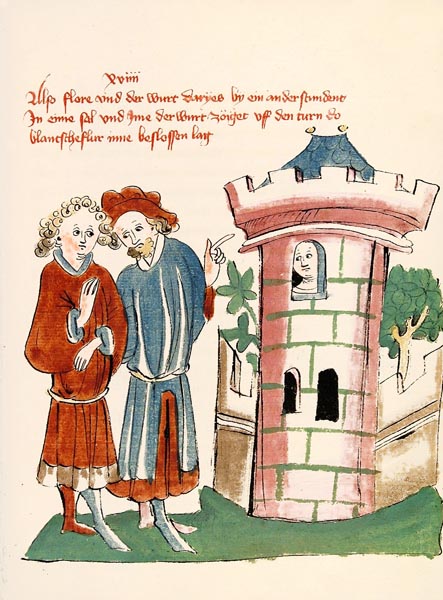

- Daries describes the might of Babylon and its Emir.

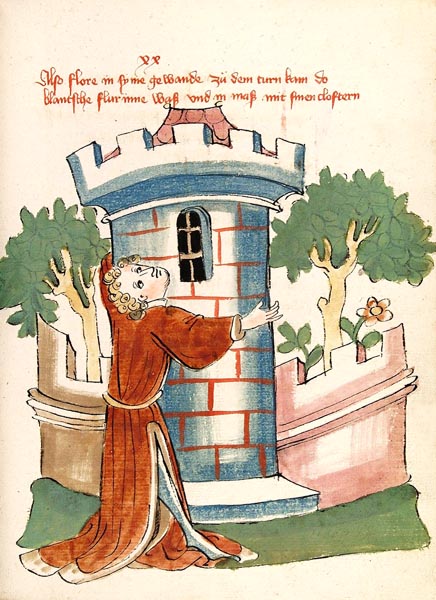

- And the tower in which Blancheflor is held.

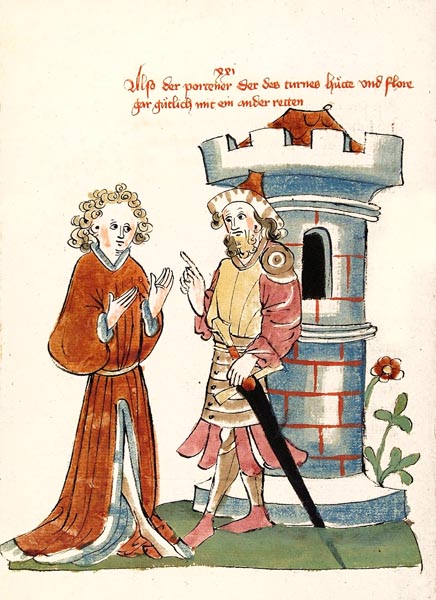

- The host tells of the tower’s porter.

- And the Emir’s behaviour.

- And of the garden of the Emir.

- And of how the Emir chooses his consort.

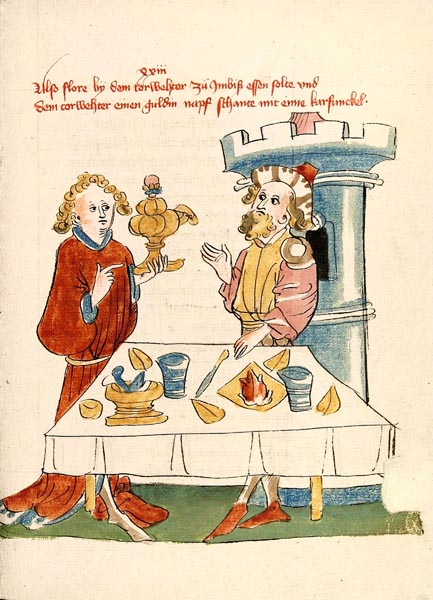

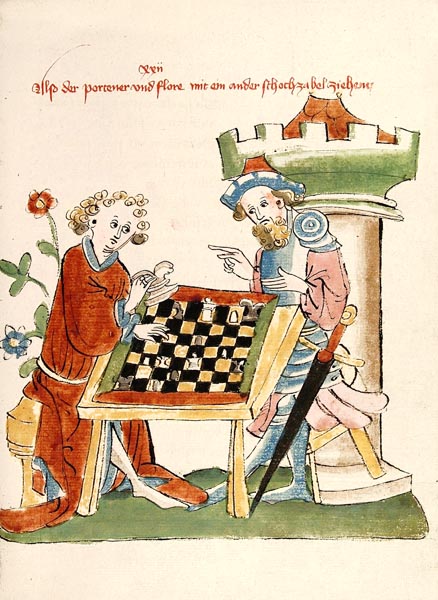

- Daires, the host, counsels Floire.

- Floire carries out his plan.

- He wins the porter’s loyalty.

- Then takes him into his confidence.

Floire attempts to slay himself

Floire now drew his silver dagger

From its sheath; twas all the dearer

As he’d received it from Blancheflor

When he’d last seen the maid, before

He’d made his journey to Montoire.

Twas this that he addressed. Said Floire:

‘My silver dagger, ready, there,

To set an end to this affair,

She gave you as a gift, that I

Would remember her, and thereby

Might do her good service, but now

I must go to her; such my vow.

Blancheflor, one might rightly say:

Too long have I prolonged my stay.’

His mother reproves his action

With it he’d have pierced his heart

But his mother, seeing, him did dart

To his side, and seized the dagger

Reproving him, in gentle manner.

As a mother, she could not see

Him die of sorrow, so tragically.

‘You’re but a child, my son,’ she said,

‘In pursuing death, for on that head,

Ther’s none on earth if they must die

And yet from death itself might fly,

Would not rather live a beggar,

Or in some den, like a robber,

Than suffer all the pains of death;

Tis ill to seek one’s own last breath.

Slay yourself, and you’ll not enter

The Elysium you chase after,

Nor will you find your Blancheflor;

No sinner reaches that fair shore.

Straight to the fires of Hell below,

There, sweet boy, such mortals go.

Minos, Aeacus, Rhadamanthus,

Are the judges there; below us,

In the depths, they judge the sinner,

Amidst the condemned, you’d suffer.

There Dido, Byblis did remove,

Two that slew themselves for love,

And wander yet through Hell in woe,

Seeking their lovers, grieving so.

They seek, and will seek, them ever,

And yet can meet with them never.

My dear sweet son, be comforted;

Seek the living, and not the dead.

For I think to find some remedy,

Whereby she might recovered be.’

She seeks the King’s agreement to a remedy

Weeping, she went to seek the king:

‘Sire,’ she said,’ are you listening;

For God’s sake, His will be done,

I pray He shows mercy to our son,

Who seeks to slay himself; I saw

A dagger he drew, and thus, before

He could attempt the act he planned,

I struck the weapon from his hand.’

‘Lady,’ said he, ‘be calm, dear heart!

His grief he will quench, for his part.’

‘True’, said she, ‘by dying, agreed,

For he will die of his grief, indeed.

We’ve no children but this fair one,

Yet we consent to lose our son.’

‘Lady, what would you have us do?’

He cried, ‘Consider it done!’ ‘Those two,

We must once more view together,

Or, losing one, lose both, forever.’

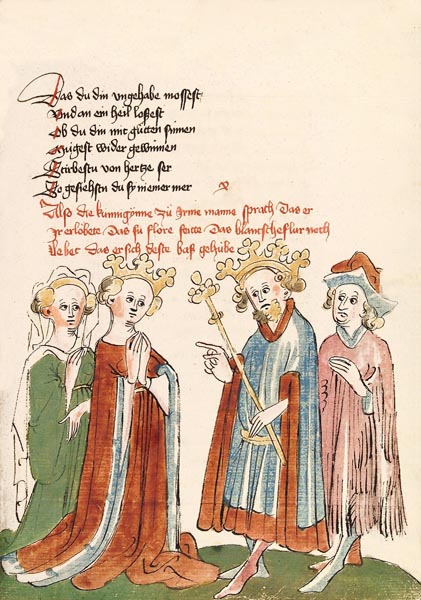

‘The queen requests the king to tell the truth’

The queen confesses to her son

The queen, rejoicing in her heart,

Sought her son, where he sat apart:

‘Dear son,’ said she, ‘by our design,

Partly the king’s, and partly mine,

We had the tomb wrought that you see.

And twould not be there, had not we

Desired that you might forget her,

And, as we wished, wed another,

The daughter of a wealthy king,

And honour us all, by so doing.

We desired that fair Blancheflor

Should be your childhood love no more,

For she was but a Christian lass,

A poor thing, of low rank, alas.

One that did her price command

Has taken her to another land.

‘Mercy, by God, my son!’ said she,

‘All is true you have heard from me.

Suffer this grief, my son, no more,

Be at peace, as you were before.’

Floire swears to seek for Blancheflor everywhere

Hearing this, he was lost in thought.

He sat for a while, seeing naught,

Then, looking one more at the queen,

He swiftly asked here if she did mean

All she’d said; had she spoken true?

‘My son,’ said she, ‘I lie not to you.’

He quit the tomb, his feet he found;

His love lay not beneath that ground;

Thanks, he gave to the Lord above,

Knowing that she still lived, his love.

He swore no effort he would spare,

But would search for her, everywhere.

He claimed he’d find the maid one day,

No matter how wild and harsh the way.

And then he would return with her,

In great joy, no more to suffer.

The joy he felt made him forget

The labour of finding her, as yet.

He asks leave of the king

My lords, I’d have you marvel not

For true Love now governed his lot,

That makes men think that they will do

That which would startle no small few.

Aristotle and Plato say

That many a man will, every day,

Do what they never thought they could

Till Love seized them, for ill or good.

Great was his joy; he gave his word,

And proclaimed he cared not who heard,

That the king’s pain might go for naught,

For he must act now as he ought.

To the king he went, who showed his joy

That his son lived, and clasped the boy,

But yet was troubled, even so,

When the lad asked for leave to go,

And said that he must seek the maid,

Of whom no news had been conveyed;

Where he might find her, he knew not,

Yet to seek her was now his lot.

The king blamed the queen’s plan for

His having sold the fair Blancheflor.

He cursed the hour, great was the cost,

For he’d lost his son when she was lost.

A thousand silver marks he’d gained,

And as much he’d give, he maintained,

If he could find her; and yet could not,

Willing or no, such was his lot.

‘Floire asks his father to aid him’

And requests his support

‘Dear son,’ said the king, ‘dwell here, still!’

‘By my faith,’ came answer, ‘you say ill,

For you but hasten my search the more,

And sooner shall you see Blancheflor.’

‘Son, since you choose not to remain,

Say where you’ll search, for I am fain

To do your will in this matter,

And meet your needs; gold and silver,

Rich silks and bales of cloth I’ll give,

And mules to bear them, as I live.’

‘Sire,’ said he, ‘now listen to me,

If you will, of your grace and mercy.

When to this merchant, I am known,

Seven beasts of burden I would own;

Two to bear the silver and gold,

And whate’er boxes I’d have hold

Aught else, and then a third, indeed,

To hold the coins that I might need,

And two more, Sire, to bear rich gear,

Like that in which fine lords appear,

Robes of sable, or martens’ fur,

And seven men with them, to defer

To my orders, and lead the mules,

And three good squires, none of them fools,

Who can forage for food, and guard

Our horses, in stable and yard.

Your chamberlain, Sire, if you please,

Send with me to ensure my ease,

For he knows how to buy and sell,

And give counsel so all goes well.

Everywhere we’ll make occasion

To seek the mart where she may be won,

And if we can find the place and she

May be purchased right easily,

We’ll give generously and buy,

And return right swiftly, say I.’

Royal gifts are bestowed on the boy

So, the lad ended his request.

The king, gathering of his best,

All that was needed did bestow.

When it came time for him to go,

The monarch told what price was paid

For the girl, when the deal was made.

‘My son’ he said, ‘such you must take;

You’ll have to give, if you would make

An equal bargain, the like amount

As Blancheflor cost, by all account.’

He gave the lad a palfrey to ride

For his own, and its gear beside.

The creature was partly milk-white,

Part red as blood; fit for a knight.

Of rich silk, the caparison,

In fine-wrought chequering was done.

All the saddle and saddle-bow,

Was made of pure whalebone below,

Coloured a blue-grey naturally;

A great marvel it was to see,

Wondrously carved, and fine gold

Was set about that work of old.

The saddle cover of silk was made

And this Castilian silk displayed

Flowers done in rare embroidery;

All this the king gave generously.

Silk were the stirrup-straps, and cinches,

And skilfully-wrought counter-cinches,

Fastened wondrously tight and sure;

The silver buckles, fashioned of yore.

The stirrups were worth a castle,

Worked in gold and black enamel.

The horse’s bit was of rich design,

No other steed bore one as fine.

Its shanks and chain were wrought of gold,

With gems, a treasure to behold,

In white enamel, here and there,

Set, to show their beauty, with care;

The whole was wrought of Spanish gold,

No finer workmanship was of old,

Nor richer; while the gems, thereon,

Were perfect, each and every one.

The bridle straps with gold were set

From where the gold curb-shanks they met.

Thus was the steed adorned, I say,

That the king granted Floire that day.

And the queen, too, a ring did offer

To set upon the maiden’s finger.

‘My son,’ said she, ‘now guard this well,

While you possess it, fear no ill,

Iron nor solid steel can harm you,

Nor fire burn, nor water drown you.

My son, great power has this ring

If you but believe in the thing,

So that my sole request is this:

In guarding it prove not remiss.’

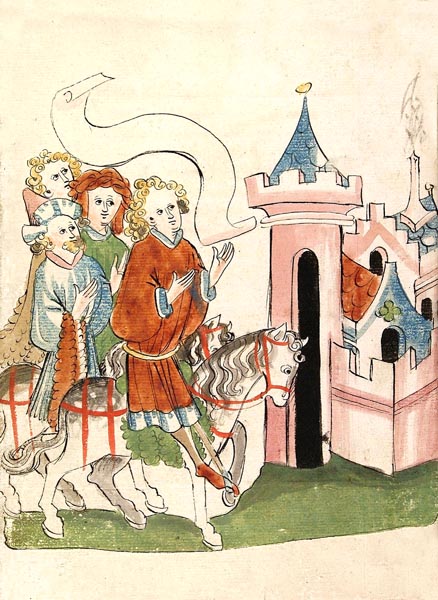

Floire departs in search of Blancheflor

He gave her thanks and took the ring,

And took his leave, then, of the king,

Saying: ‘I’ll find my true love, so!’

The king granted him leave to go.

Weeping; he took leave of the queen

Amidst a hundred kisses, I mean.

Many a tear wept the royal pair,

Wrung their hands, and tore their hair,

And showed such grief at that parting

As if they’d die there, of weeping.

Then, commended to God alway,

Floire departed, and went his way.

‘Ride of the knights to the orchard’

He and his company reach the port

Once he was outside the city,

He readied his men for the journey.

He and the chamberlain concurred

On their route, and then gave the word.

For the port, at once, they started,

From which Blancheflor had departed.

They travelled on until they came

To a townsman’s house, where that same

Lodged many a merchant, great and small,

And there dismounted, one and all.

Once the horses were stabled there,

And fed, with oats and hay to spare,

Servants went to the market place,

And roamed about it for a space.

Food they bought, of every kind

The finest viands one could find.

This, the master had commanded:

None must return empty-handed.

Indeed, much bread and wine they bought;

And for the dinner these they brought.

Merchants were they, claimed the company,

Set to sell their goods beyond the sea.

Floire said he was their sovereign lord,

The goods were his; once reassured

The host had their dinner prepared,

While no attention now was spared.

They washed their hands, and wiped them dry,

And sat down to supper, by and by.

‘The meeting of knights and ladies in the orchard’

The company dines, though Floire seems distracted

Now, Richier was their host’s name.

His place at their table he did claim.

He honoured them much, held them dear,

And urged them to eat, his kindness clear.

The table bowed under the weight

Of the rich food that company ate.

They were served most handsomely,

Wine was brought, then poured swiftly

Into their cups from bowls of silver;

The clear wine and mead flowed over.

They laboured hard that company

At eating and drinking copiously,

Oft saying the wine was good, indeed;

Saint Martin had blessed it they agreed.

While they were dining cheerfully,

Floire’s mind was on Blancheflor, for he

Despite the good wine, ne’er forgot

That, without her, woeful was his lot.

Thoughts of her troubled him greatly,

Such that he oft sighed profoundly,

Ever careless of whether his hand

Raised his cup, or bread did command.

The hostess observed him, keenly,

As she filled her lord’s cup, neatly:

‘Sir, said she, ‘do you note this lad,

So self-contained, and seldom glad?

He leaves his food, so full of thought,

See him sigh, for with woe he’s fraught.

Upon my life, no merchant is he,

He’s a lord, and upon some journey.’

He set to questioning the young man.

Floire hears news of Blancheflor

‘Sire, much thought you seem to command.

I have watched you; as to food and drink,

Little you take, while much you think.

What you have eaten of this meal

Would count for but little, I feel.

A like face I saw the other day,

A maiden, Blancheflor, passed this way

(Such was the name that she gave me)

And, by my faith, you’re as sad as she!

She looked to be the very same age,

And seemed as woeful in her visage.

She pondered likewise over her food;

On one she loved she chose to brood.

Floire, it seems, was this lover’s name,

She to be sold, and lose that same.

She dwelt here for two weeks or so,

And endlessly her tears did flow.

She pined for Floire her true lover,

And night and day bemoaned him ever;

Except for that, the girl did naught.

She was sold in this very port.

The one who bought her, so they said,

To Babylon has that maiden led.

The commander there now owns her,

Who for twice her price obtained her.’

When Floire heard his lover named,

And news of her was likewise claimed,

The prince was struck by sudden joy,

While the cup with which he did toy,

Filled with wine, the lad knocked over,

Struck mute at word of his lover.

The host cried: ‘Come, tis forfeit, now!

We must amend this thing, I vow.’

‘True; that we must!’ cried one and all;

Filled with delight, thus they did call.

Floire filled the cup, of rare design,

Right to the brim, with vintage wine,

And presented it to him graciously:

‘This I present to you,’ said he,

‘For you have brought me certain sure

News of that maiden, fair Blancheflor.

For tis of that sweet maid I think,

And sigh, rather than eat or drink,

And though knowing not where to go,

Set forth to seek her high and low.

Now I’ll follow her to Babylon,

Nor will quit her, ere I am done.’

Then he added: ‘Once being spilled

Tis right the cup should be refilled.

Drink if you please to my return,

If you would our good fortune earn.’

Four servants came where they did dine,

And brought the guests four bowls of wine;

To make amends, the wine they poured;

To the host, his cup Floire did afford,

When from it he had drunk a sup;

The host drank, and returned the cup.

And all the rest, within the place,

Contended then, and drank apace.

The poorest matched the richest there,

And right boldly acquired their share.

They enjoyed themselves happily,

Till the wind blew, propitiously.

He boards ship for Babylon

Afternoon now had turned to eve,

The tide had risen; and they might leave.

The air was clear, bright and serene,

The heavens shone on all that scene.

The ship’s captain did then declare,

That all was set, the wind was fair.

They had lingered there long enow,

And were desirous of sailing now.

The owner cried the news abroad

Through all the town, that those should board

Who would journey to Babylon,

Or to the land, there, would be gone.

Floire was delighted when he heard,

He was eager to leave, in a word.

One he’d gathered his company,

And then rewarded his host fully,

He took leave of him, went aboard,

To be borne by that ship abroad.

Floire hears of the feast to be held there

Of the owner he had requested,

And he on oath had so attested,

That they arrive at that fair port

Nearest the city that he sought,

That of Babylon, for he had heard,

Or rather the owner had brought word,

That in a month from that very day,

All of the monarchs who held sway

Over the Emir’s lands, in short

All the kings that adorned his court,

Would gather there to a feast he’d hold.

‘There,’ said the merchant, ‘may be sold

All of my cargo, and I gain greatly,

All of it shall be bought, and swiftly.’

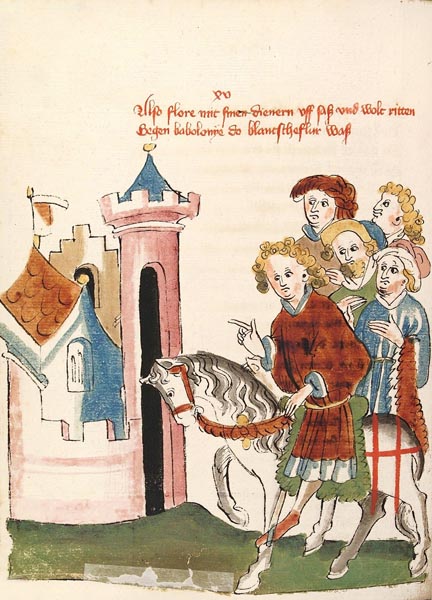

‘Floire sets sail’

He sets sail with his company and reaches Baudas

The sky was clear, the wind blew free;

At once the ships set out to sea.

From the port they issued that day,

On the ebb, to gain steerage way.

The sails were unfurled to the light,

And to the top-castles drawn tight.

The wind drove them astray, swiftly,

As soon as Floire was out to sea.

The company he’d brought aboard,

Was such as befitted a royal lord.

Eight days they wandered fitfully,

And never a sight of land did see.

Baudas, they reached, on the ninth day;

The city stood high over the bay,

On a rock grey-brown in colour,

Above the port, and the harbour.

From there, on a clear day, the eye

Viewed a hundred leagues of sea and sky.

The ships’ owner well knew the road

To the height, which they now followed.

Twas the city that Floire had sought,

When he went aboard, the very port.

From there twas but four days journey,

If naught delayed the company,

Or little longer, till he might come

To the Grand Emir in Babylon.

The merchant asked for his reward

And Floire, like a generous lord,

Gave him twenty pieces of gold,

Then twenty of silver, all told,

For he thought himself in paradise,

Since there he might attain the prize,

And find his love, in that far country,

She whom he sought o’er land and sea.

‘Floire’s voyage to Babylon’

He finds lodging there

Swiftly he disembarked on the shore,

While the ship was loaded once more,

Then ascended to the city,

Which he now wished to enter quickly.

There was lodged a rich ship-owner,

Merchant and contractor, moreover.

He owned a vessel of ample size,

In which was loaded merchandise,

And so traversed the seas and served

To bear the goods therein reserved.

In this the merchants, furthermore,

Had sailed, who purchased fair Blancheflor,

The lovely maid that Floire now sought

For whom his heart was ever fraught.

In that house he now passed the night,

Once he had climbed the city height.

From the merchant Floire hoped to hear,

News of her, whether far or near.

The company unloaded their effects,

And stabled the mules and horses next,

Ensuring the creatures were well fed,

Granted hay and straw for a bed.

In that hostelry, they found to hand

Everything that one might demand,

Feed for the horses, bread and wine,

Meat, salt, and fish on which to dine.

They asked for supper hastily,

For they were weary from the sea.

Floire hears further news of Blancheflor

The Emir commanded the port;

Many a merchant there he caught,

For rightly or wrongly all who came

Were obliged to pay to that same

A sixth part of the goods they brought,

And swear too that they held back naught.

To the mistress of the city,

The Lady Marsile, went this fee.

Once the company had paid,

And the supper table was laid,

They washed their hands, and sat to eat;

Floire was granted the noblest seat.

They were offered the choicest fare,

That might please all palates there.

But Floire little sustenance sought,

For his lost love was all his thought.

The host gazing upon his guest

Thought his spirits not of the best:

‘Sir, said he, ‘it would seem to me,

You are brooding upon the fee

Charged against the goods you’ve brought.’

Floire answered: ‘Tis indeed my thought.’

‘I saw a like frown the other day,

In this hostelry,’ the host did say.

‘That day there came a company

Of merchants out of Spain, you see,

And to this port they had conveyed,

Tis truth I tell, a pretty maid,

And she looked much the same as you,

For she was quite as pensive too.

The name that I heard was Blancheflor,

And she could not have sorrowed more.

She too, at her supper, sat and sighed,

Thoughts of her love she could not hide.’

At this news, Floire felt great delight:

‘Where did they go, after that night?’

‘When they left, the very next day,

To Babylon they made their way.’

Floire gave to him a cloak, full fine,

And a silver goblet for his wine.

‘Sir,’ said he, ‘I would have you take

These gifts for lovely Blancheflor’s sake;

For she you speak of, understand,

Was reft from me in my own land.’

The host, in thanking him, replied:

‘Lord Jesus return her to your side!’

When they had eaten what they would

The servants made the table good.

Their beds prepared, the company

Went to their rooms and slept soundly.

Though Floire would sleep, his heart would not,

He thought of Blancheflor, and her lot,

And if he found sleep, twas but light.

When dawn broke, dispelling the night,

The company woke, and were ready

To start once more on their journey.

They take the road to Babylon and reach Monfelis

Soon on their road they were gone,

To seek the city of Babylon.

That night they came to a fine inn,

And found decent lodgings therein.

And the next day, upon the morn,

Took to the road again, at dawn.

That night they lodged in a town

Whose market was of some renown,

There they heard talk of Blancheflor,

For she’d passed that way before.

The third day, at eve, the company

Arrived at an arm of the sea,

‘Hell’s Deep’ its name, in that country.

On the far side, lay Monfelis,

A great castle where those were found

That conducted folk o’er that sound.

The castle knew neither bridge nor ford,

The flood was too deep such to afford,

And too wide, but a horn hung high,

Set on a post, beneath the sky.

Floire proceeded to blow the horn,

To call the ferryman who, borne

On the wave, now rowed to their shore

As briskly as he could pull an oar.

He commanded a boat in which

The gentlemen might toss and pitch,

And so might every man, and squire,

And the mules, to their heart’s desire.

Then they began to cross the water,

The travellers and the boat’s owner,

Who gazed at Floire; to this ferryman,

The other seemed a rich nobleman,

He asked of him: ‘Where are you bound?’

‘Merchants are we, and o’er the sound

We go to seek Babylon, where we

Would buy and sell in that country.

If that castle might lodge a knight,

I would lodge in that place tonight.

‘I’d lodge you willingly, by my creed,

For there lies good lodging indeed.

But fair friend, come tell me why,

You’re sad and pensive to my eye,

Ne’er so sad a face did any show

To my sight since, six months ago,

A sorrowful maiden entered here,

Who quite as pensive did appear.

I know not if you are kin to her,

For, by my faith, you resemble her.’

‘Floire rides to Babylon’

Floire hears that Blancheflor is in Babylon

On hearing this, Floire raised his head,

‘Sir,’ said he, ‘where to was she led?’

‘To Babylon, to the Emir’s court,

For tis he that the maid has bought.’

As the man spoke, they reached the shore,

And were on solid ground once more,

And having lodged there for the night,

Floire took his leave, in the dawn light.

He gave his host a hundred in gold,

And prayed that, if in Babylon’s fold

He had a friend who’d aid the cause

Of a stranger from foreign shores,

He would send word, if he agreed,

That he might counsel them, at need.

‘Sir,’ said he, ‘ere you can enter

Babylon, you’ll reach a river

That you’ll find both deep and wide.

Once o’er the bridge, then confide

In the toll-keeper, who is my friend,

And to a like task his life doth lend.

In Babylon, a rich man is he,

With a house there that’s fine to see.

We are companions in our trade,

And share the profits we have made.

Here is a ring that you must bear,

And give my friend, once you are there,

And say I’d have him counsel you,

And he will grant you lodging too.’

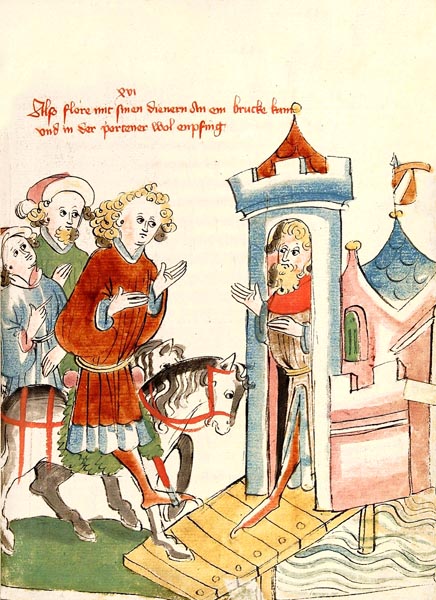

They reach the river-bridge, and Babylon

The company went on their way,

And came to the bridge at midday.

There they found, beneath a tree,

He who let none there pass for free.

Beneath the tree he sat alone,

On a block of marble like a throne.

His body was richly clad, and he

A man of substance seemed to be.

None could pass the river, I say,

Lest four silver coins he did pay,

And for his horse four of the same,

Floire saluted him, in the name

Of all the gods, and then the ring

He gave to him, that he did bring

From his friend, and requested he

Should lodge them there, and kindly

Grant them his good counsel, at need

For love of that friend, if he agreed.

He, in turn, recognised the ring,

And was delighted by the thing.

And his own ring he then did send

To his wife, that she might extend

Hospitality to them, that hour,

Pointing out his house and tower.

He told them to go there swiftly,

For his ring would grant them entry.

They were welcomed hospitably,

And lodged with stabling, splendidly.

Now was Floire within the city,

Where he had long desired to be,

Lodged with his host as agreed.

Of good counsel he had great need,

For though within this foreign place

Which he had long wished to grace,

He lacked knowledge of what to do

For of its customs naught he knew.

‘Floire arrives in Babylon’

Wisdom and Love debate within him

Wisdom set this thought in his mind

To recall his rank, and be not blind,

And not to err now, foolishly,

Through ignorance of this country.

Saying: ‘What know you of these men,

To whom you speak, Floire, as and when?

What will they make of what they hear?

Reveal all, and you’re a fool, tis clear.

Twould be your ruin, for the Emir

Will know your folly if he should hear.

If he does, he’ll have you taken,

And hung, if I’m not mistaken.

Be wise, and return whence you came,

Once there, a fair wife you may claim,

Your parents will find you a fine bride,

A girl of good parentage beside.’

But Love replied: ‘What’s this I find?

Depart? And so, leave the maid behind?

Was it not for her you chose to roam?

Yet, without her, would scuttle home!

Recall you not how the other day

You’d draw your dagger, and would slay

Your own self for the love of her,

Yet would return to wed another!

And if you were there without her,

Willing or no, you’d yet remember.

Can you live, and yet lack her now?

You’d be mad to think so, I avow.

All the goods in the world, its gold,

Without her must but leave you cold.

Remain here, and be wise instead,

And rescue her, if she be not dead.

None can hold a creature readily

That is determined to be free!

If she knows you’re here, she’ll find a way

To speak to you, if indeed she may.

Many a way true Love will find,

That many a guard has rendered blind.

Folk do say that God e’er labours,

If He pleases, for those He favours.’

This the contest within his mind,

Which argument Love won; I find.

Floire dines with the host and his wife

In a while, to his host he came.

Finding Floire so silent, that same

Questioned him quite openly:

‘Young sir, I must demand of thee,

Can it be that aught troubles you?

The lodging with us, do you rue?

If you see aught that may displease,

I shall amend it; so be at ease.’

‘Sir, I thank you,’ was Floire’s reply,

‘You speak kindly, none could deny;

Naught’s amiss here, assuredly,

I but pray that God allows me

To recompense you for my stay,

And all the kind words that you say.

Sir,’ said he, ‘my thought dwells upon,

A thing I seek; yet thinking thereon,

What I seek, I’ll not find, I fear,

Or fail to win, though I find it here.’

The host was a gentleman complete,

‘Sir, said he, ‘let us go and eat.

Afterwards, if I can so do,

I willingly will counsel you.’

He ceased then, his wife he sought

So that the supper might be brought:

‘Lady, said he, ‘honour our guest,

For none is as fair, you will attest.’

The pair, Daires and Licoris,

Seated Floire twixt them, at this,

And they drank fine wine together,

From cups wrought of gold and silver;

Vintage wines both red and white,

The mulled, and the sparkling bright.

Of fine dishes there were many

At that supper, with fowls a plenty,

And plates of venison; on wild boar

They dined, and then asked for more;

Nor for goose, crane, heron, did want,

Partridge, bustard, or cormorant;

All you can think of they addressed,

And, after they had paused to rest,

Daires, the host, had ripe fruit brought,

All to delight his little court,

Pomegranates, and figs, and pears,

– With many a cup to drown their cares! –

Peaches, and chestnuts a-plenty,

For such were grown in that country.

Sweet wine they drank, sweet fruit they ate;

All that was fine filled cup and plate.

‘The mourning Floire at the richly set table’

His pensiveness and sadness is perceived

Floire gazed in the cup they did pour

While thinking still of his Blancheflor;

Twas filled to the brim, moreover,

With wine clearer than spring-water.

Helen was carved there; she did stand

By her Paris, who held her hand.

He gazed thereon, at that image,

And Love, within, roused his courage.

He said to himself: ‘Now envy, there,

Paris that his love’s hand doth share.

Ah, God above, will the day e’er be,

When I’ll have Blancheflor thus, by me?

Come, Floire! Once from the table,

You shall have your host’s wise counsel.’

The lengthy meal had weighed on him;

The host’s wife had gazed long on him,

And had perceived his heart was sore;

He was sad and thoughtful and, more,

Down his face, that was open, tender,

She saw that heartfelt tears flowed ever.

She pitied him, and made it known,

To her husband, in a quiet tone.

Napkins fell from their hands, and they,

All but those three, now moved away.

‘The goblet’

Floire hears yet again of Blancheflor

Then the host said: ‘Fair sir, tell me,

If twould not annoy too deeply,

Of your thoughts; grant me a view,

And, by my faith, I’ll counsel you.

Hide not your inner self from me,

Tis simple, as far as I can see,

To sell your goods; you seem, rather,

Troubled by some other matter.’

‘Sir, by my faith,’ added Licoris,

‘When I first saw your face, I wis,

I thought it was Blancheflor the fair,

And that her twin was standing there.

Such a face, and form, and manner

Is yours, she might be your sister.

I thought you both related, for you

Are so wondrously alike to view.

A fortnight she was here, with grief,

Regrets, and tears, her sole relief.

She pined for Floire, her love, I say,

And wept for him both night and day.

Twas in this very house she stayed,

Until the Emir bought the maid.

You are her brother, or her lover.’

Floire could scarce a word now utter.

‘The wailing Blancheflor aboard ship’

He confesses the nature of his quest

Then, blurted out a hasty reply:

‘A lover, and no brother am I.’

Yet, repenting of what he’d said:

‘I misspoke, lady’, he cried; ‘instead,

Forget my words, she is no other

Than my sister, and I her brother.’

‘My friend,’ Daires replied, ‘fear naught,

To find this maid you seek the court,

And since the maiden you would win

With truth not falsehood should begin!’

‘Sir, for the Lord’s sake, have mercy,

A prince am I, I swear, and truly,

My true love is that same Blancheflor,

Snatched from me, by vile envy’s claw.

I have followed her to this land,

Yet here am lost, you understand.

Rich am I, in silver and gold,

And can grant to you, wealth untold,

If you can advise me, in this plight.

Judge for yourself, tell me aright,

How this will end, shall I win her,

Or die of grief, a faithful lover?

Daries describes the might of Babylon and its Emir

Daries said: ‘Harm that would be

To die for love, so foolishly,

An act of which I scarce could say

That in the deed wise counsel lay.

Better to hear what I tell you:

If act is what you choose to do,

Though I think that you’ll do naught

But throw your life away for sport.

The Emir hearing of such a one,

Would leave you to your martyrdom.

No king that rules in this country

Could ever, as far as I can see,

Seeking to win the like, achieve

His aim, in any way, I believe,

By use of force, or by enchantment,

No, such would ne’er serve his intent.

If all the folk that there ever were,

With all that live, in seeking her,

Thought to take her from this Emir,

Then all would fail, such is my fear.

The Emir’s law spreads its wings

O’er a hundred and fifty kings.

If he summons them to Babylon,

None may excuse himself, not one.

And Babylon, on every side,

Extends for twenty leagues full wide.

The walls that guard it are full high,

And they encompass it all, say I,

And they are made of such a mortar

No pick can pierce in any quarter;

They are full thirty feet in height,

Unassailable by day or night.

Through seven score gates all enter in,

With towers above, that none can win.

To the mart, open to all men there,

All week long the good folk repair.

Within the walls of this place, say I,

Seven hundred towers rise on high.

With each held by a noble lord,

That to the city defence afford.

And the weakest of those towers

Fears no king or prince’s powers;

Even Rome’s mighty emperor

Is worth not a fig in this matter.

By the use of force, therefore,

None may win the fair Blancheflor.

She is so guarded night and day

That none can steal the maid away.

‘Daries shows Floire the prison tower’

And the tower in which Blancheflor is held

In the midst of this vast city

Is a tower of great antiquity,

Two hundred feet high, a hundred wide,

Round like a chimney its outside.

The whole is of green marble wrought;

With no beam or strut its wall is fraught,

But like a belltower, tis roofed with wood,

Gilded with purest gold its hood,

While ninety feet tall is its spire,

Of the finest gold one might acquire

In minted coins, and the roof below

A hundred marks of gold doth show.

A ruby, by enchantment, on high,

Set on the spire’s tip, lights the sky,

By magic and art, it glows so bright

It shines as twere the sun, at night.

All about the city, everywhere,

It sheds such splendour in the air,

That ne’er a lad on the darkest night

Bears a lantern, or a brand alight.

No knight or merchant has to guess

Where he might be, midst the darkness,

Nor others find themselves astray,

In the city at night; tis bright as day.

On land or at sea, none can doubt

Where they are, nor must cast about.

From twenty leagues away, tis clear

And bright as one not far but near.

Three floors do this high tower grace.

Skilful were they who built the place.

The floors of all three are of marble,

And unsupported (tis a marvel),

Except those above by a pillar

That rises upwards at the centre,

Reaching from the ground below

To the spire that on high doth show;

And, within it, there’s a channel

Made of marble clear as crystal,

From which a flow rises higher,

Of clear and health-giving water,

Lifting as high as the third floor,

Whence the flow returns once more,

(The designer having wrought with skill)

Through another channel it doth fill

Within the pillar, and descends

From floor to floor, ere its journey ends.

The ladies that inhabit the tower

Take all they need to that bower.

Seven score chambers lie inside

Within which those ladies abide.

No place was e’er more delightful,

The pillar wrought all of marble,

And of costly wood is the portal,

Of a kind that’s wellnigh immortal.

The windows are wrought of ebony

And myrtle-wood, splendid to see.

All who the Emir’s tower wrought

With great labour his comfort sought,

No gliding serpent can come there,

Nor can other vermin climb the stair.

The ceilings and the walls there hold

Paintings done in azure and gold,

And the inscriptions there reveal

The subjects the paintings conceal;

All the Emir’s forebears are there,

Their battles and prowess they declare.

In each high chamber he has placed

A maiden suited to his taste,

That might serve him at his pleasure

And be summoned at his leisure.

From one tier to another go

Flights of stairs, above and below.

The middle tier has a single door

In a chamber leading to that floor,

Through which the maidens descend

To the Emir’s chamber and ascend.

And all there must serve the Emir,

As it pleases him, it would appear.

Seven score maids are in that place,

Of noble form and fair of face.

And since those maids are in its power

They name that place the Maiden’s Tower.

Two pairs of maids serve the Emir,

On rising and sleeping they draw near,

One of the pair brings him water,

His towel’s held by the other.

The guards set to man the tower,

Bear no lances within that bower.

Three of them, the steadiest men

Control each floor, and under them,

Are nine who are appointed there

To serve him humbly and prepare

The food he eats, and make his bed.

Those overseers fill all with dread,

And, so guard the floors of the tower

They know its state at any hour.

In their fists they grasp a blade,

A dagger or poleaxe there displayed,

In the passageway each doth stand,

To guard the way, you understand,

And not a bird could fly within,

Though it might seek to enter in,

For aught that it could seek to do;

They’d obstruct it, and slay it too!’

Of this porter, I’d have you know,

For great knowledge he did show;

The Emir loved him with all his heart,

Though if he’d thought that by his art

He might deceive him in any way

He’d not have left him there a day!

Firm and steadfast was this porter,

For if he’d been a useless idler

Whom one might bribe in any way

As I have heard some are today,

And one that Floire might have deceived,

I’d tell you so (and be believed!)

‘Blancheflor at the window of her prison tower’

The host tells of the tower’s porter

I’ll leave him be, but let me tell

Of the host again, and what befell.

For he now laboured to devise

A means for Floire to realise

His aim, and soon spoke again, so:

‘Floire, be not so filled with woe,

Though of the porter I would speak,

Who guards the path to her you seek.

He lets none pass at any hour,

To spy, on high, within the tower.

For except the Emir should allow

That passage, they’ll be harmed, I trow.

If they do not depart that place,

In silence, and with no ill grace,

He’ll beat and plunder them until

They obey him, and do his will;

For he has leave from the Emir

To beat those who show little fear.

He guards the tower thus with care,

Without him none can enter there,

None can put e’en a foot inside;

With him the power doth reside.

Four watchmen, upon that tower,

Watch night and day, every hour.

Of these watchmen I tell you true,

They are paid well for what they do,

For they must watch all day and night,

Both in the darkness and the light.

If any would approach, they blow

A horn, and signal to those below.

‘Floire talking to the guard before the tower’

And the Emir’s behaviour

The Emir’s custom is to hold

Each maiden a full year, all told,

And then command that she be led

To execution, and lose her head.

He lets no clerk nor knight appear

To champion her, from far or near.

Head from body is struck asunder,

Such honour to the maid they render.

Then when he would take another

He has the rest descend together

To a fair garden there below,

With fluttering hearts and full of woe,

Little doubting the loss of honour

That might come, thus shamed for ever.

And of the garden of the Emir

Now, of this garden you shall hear

For, there, they’ll be, after a year.

The garden is large and very fine,

And none is as lovely, I’d opine.

One part a wall doth there enfold,

Adorned with azure and with gold.

And on the wall, so I have heard,

Upon the right, there sits a bird.

Copper covers it, body and wing,

None may in silence view the thing,

For when one comes, it gives a cry,

That all must hear who thus pass by;

Fiercer it sounds than any creature,

None there is can match its manner.

Wolf, lion, tiger, drop to the ground,

And lie still, when they hear that sound.

When the bird has vented its anger,

It sings most sweetly thereafter,

And, the garden now grown serene,

Such sweet birdsong fills all the scene,

Whether you deem it false or true,

Of larks, and jays, and blackbirds too,

Of starlings, nightingales, they say,

Orioles, finches, in bright array,

And all the other birds found there,

That fill with joy the garden’s air,

Who hears their chorus and their song

Cannot but for their loved-one long.

Round another, flows, by strange device,

One of the streams of Paradise,

The Euphrates that river’s name,

And no man can traverse that same,

No none can seek to pass it by

Except they own the wings to fly.

In its clear depths, every manner

Of precious stone lights the water;

There sapphires gleam, chalcedony,

Sardonyx, jacinth, one may see,

Rubies, topazes, and jasper,

Emeralds, quartz, and many another

Jewel, whose name I will not list,

Or know not, bright as amethyst.

This garden too is ever in flower,

And birdsong fills the pleasant hour.

There is no tree of proper worth

That rises here, upon this Earth,

Ebony, rowan, or plane-tree,

No new graft, no fine fig-tree,

Peach, or walnut-tree, or pear,

No sound fruit tree, but prospers there.

Incense, cinnamon, and pepper,

Clove, and zedoary, and ginger,

And other spices that smell sweet

Make the inventory complete;

None finer grant both taste and scent,

Twixt Orient and Occident.

Who dwells there midst the odours,

Of the spices, and the flowers,

And hears the birdsong up on high,

The grasshoppers beneath the sky,

That do the listener, thus, entice,

Think themselves in Paradise.

On a central lawn doth appear

A spring, that is both fresh and clear;

It runs in a squared-off channel,

Wrought of silver and of crystal.

A tree is planted o’er the spring;

None born e’er saw a fairer thing.

Since it ever flowers there above,

They call that tree the Tree of Love.

A fresh flower blooms, if one should fade;

The gardener’s skill is there displayed,

For the tree’s leaves are ever green.

Its careful planting may be seen,

For they that did the place conceive

Wrought subtle art there, I believe.

At dawn, when the sun seeks the sky,

The green leaves are all lit thereby,

And so auspicious is its setting,

That tree is forever flowering.

And of how the Emir chooses his consort

When the Emir chooses a maid,

He has the maidens there arrayed,

Beside the ever-flowing river,

Gold its gravel neath the water,

And o’er its channel they must pass,

That’s wrought of gold and crystal glass.

They cross in orderly manner,

While the Emir views the water,

And wills his people to draw near,

For a marvel doth now appear.

When a virgin passes o’er,

The water is both clear and pure.

But when one passes that is not,

The water’s turbid, at that spot.

Tis a wonder all that affair,

To which no other can compare.

Any woman the trial shames

Is given at once to the flames.

And then he has the rest pass by

Neath the tree, that he might spy

Which shall serve that year, of all;

Tis she on whom the flowers fall.

The tree behaves in such manner

That she on whom falls a flower,

Is then crowned, immediately,

And named as queen of the country.

He weds the maid with great honour,

And as her husband he loves her,

For the year to come, as I’ve said,

Then violates her, and she is dead.

Yet if there is a maiden there,

That he loves best, and is most fair,

Then by enchantment, at his will,

The flower falls on that maid still.

On a month from this day will fall

The feast to which that lord will call

All the noblemen of his court,

For on that day his queen is sought.

Blancheflor he will choose that day,

For none is dearer to him, I say,

Of seven score there’s none so fair,

Whom he might choose to marry there.

He desires her as his consort,

His mind is set on her, in short.

The time that yet remains doth fly,

And the hour of the feast is nigh.’

‘You have my thanks.’ was Floire’s reply.

‘Though if tis thus, then I must die!

For should she marry the Emir,

Then my mission has failed, I fear.

Daires, dear host, what shall I do?

Upon my life, here’s a pretty stew.

Yet what care I, if I lose my life,

If I cannot take the maid to wife?’

‘Floire clasps the tower in his arms’

Daires, the host, counsels Floire

Daires replied: ‘Since it doth appear

That your heart’s possessed by that fear,

Such that you care not for your life

If you take not the maid to wife,

Now listen closely to what I say;

I’ll grant the best advice I may.

Tomorrow, go straight to the tower,

Having made your plan this hour,

And though you go with rapid stride

Take great care your aim to hide.

The porter, who’s a vicious one,

Will e’er your intention question,

But you, with cunning, must reply

Such a tower you’d raise on high,

Once you return to your own land,

That might be viewed close to hand.

Of your fine speech he’ll take heed,

And think you a rich man indeed,

Then to acquaint himself with you

He’ll play a game of chess or two,

For he most willingly plays the game

And takes great pleasure in that same.

Now you shall have, of a surety,

A hundred ounces of gold, from me,

Go not, if you’d live till you’re old,

To that meeting without the gold,

For with that gold, you’ll succeed;

My plan it is to arouse his greed.

Let him win, and to him render

All the gold, when you surrender.

And he will marvel that you seek

To play him, your game being weak.

On the morrow go there once more,

And concede the game, as before,

But take twice the gold with you,

Of your own store, and likewise do,

Grant him all, but then maintain

You’ll not return to play again.

His thanks he’ll give for that same,

And then beg you for one more game.

You will say: ‘Thank you, in turn,

My love, for this, you rightly earn,

Of gold and silver, I’ve a store,

So won’t object to play once more,

For you have welcomed me with grace,

And good address, sir, to this place.’

Four hundred ounces of fine gold,

In your hand take there, all told,

And your goblet in the other hand,

The next day, and let him command

The play, and in losing render up

All of your gold, but not the cup.

He’ll offer to play for that same,

If you would risk another game.

Say that you’ll play no more that day,

But take him to dine right away.

He’ll be delighted with his treasure,

Having plundered you at leisure,

And he’ll honour you as you dine,

Hold you dear, as he sups the wine.

He will covet that cup of yours,

And long to own it, in due course.

He’ll offer a thousand marks, in lieu,

To obtain the goblet from you,

But tell him you’ll not sell it him,

But from pure friendship grant it him.

At which, deceived completely, he

Will love you all the more, you see;

He’ll fall at your feet, full of joy,

And words of homage will employ.

And you’ll accept them, not despise

His trust in you, if you are wise.

For love and honour he will afford

To you, as if you were his lord.

And then you may reveal your plight,

Say why you languish day and night,

And if he will, he’ll grant you aid;

And if not, all’s lost, I am afraid.’

‘Floire bribes the guard’

Floire carries out his plan

Floire thanked Daires from his heart,

For the counsel he did impart.

He went to bed, having drunk deep,

Although his thoughts robbed him of sleep.

Floire arose at the break of day,

And Daires saw him on his way.

He went to the foot of the tower

And gazed about, in the dawn hour.

The porter came, and shouted aloud,

So that the youth was almost cowed:

‘A spy, I see, or perchance a traitor,

Gazing at us!’ so cried the porter.

‘Sir,’ Floire replied, ‘by my faith, no,

I come but to view the tower, so

I might build the like in my own land,

And would but see it close to hand.’

Now, Floire spoke so courteously,

A nobleman as the guard could see,

And appeared so handsome indeed

The man abandoned his harsh creed,

Saying: ‘He looks not like a spy.’

And he asked of Floire, by and by,

If he liked chess, and would play a game,

For he was partial to that same.

Floire said he would. ‘What stake, my friend,’

Said the porter, ‘will you defend?’

‘A hundred ounces of purest gold.’

‘And I the same, since you’re so bold.’

They sat down to play, as they’d agreed,

Floire was the better player indeed,

Yet did the game to the guard concede,

And paid him, as Daires had decreed.

The porter marvelled at one so bold,

And thanked Floire for the heap of gold.

Then begged him to play one more game

By which he might retrieve that same.

Floire agreed without more delay,

And so returned the very next day,

With two hundred in gold in his hand,

And staked it all, as Daires had planned.

Floire was no slower to concede,

And yielded the winnings as agreed.

The porter was overjoyed and gave

Him thanks, and dubbed his tactics brave.

Floire took his leave of him, but then

Agreed to return and play again,

And the next day was at his command,

With the prized goblet in his hand,

And four hundred gold pieces more,

Which he staked, as he had before.

And then the porter did the same,

And they sat down to play the game.

Before the board sat the porter

And set all the pieces in order.

With his knight Floire now wrought havoc

And cried ‘Check!’; the porter took stock,

And having counted up the cost,

Perceived the game was truly lost.

He offered Floire the gold he’d won;

He refused, and would accept none,

Delighting the other by doing so,

Who to retain it proved not slow.

Being deceived as to his aim,

He sought to play another game,

With the cup at risk on Floire’s side,

‘No, in truth, I cannot!’ he replied.

‘Floire and the guard playing chess’

He wins the porter’s loyalty

Floire led the porter off instead

To his lodgings, to be wined and fed.

He was honoured by the latter

For his wealth, and then the matter

Of the cup moved the man deeply,

For he coveted it greatly,

Cried he’d offer for it, all told,

A thousand ounces of pure gold.

Floire, finding him so covetous

Feigned to be truly generous

And said: ‘No gold I’ll have of you,

But gift you it, for love of you,

And you may grant to me indeed

Some favour if I seem in need.’

The porter took the cup and swore

He’d serve him gladly, evermore.

Seduced by the gift he’d received,

The porter was thus well-deceived.

And led Floire, without more ado,

Into the garden, its grounds to view,

Fell at his feet, and scarce would rise,

(Which Floire accepted, being wise)

And swore again he would afford

Him service, as if he were his lord,

And would prove both faithful and true;

No other course would he pursue.

‘Floire confesses his love for Blancheflor to the guard’

Then takes him into his confidence

‘Sir,’ said Floire, ‘since that be so,

Then, as my man, I’ll let you know

A secret, for I trust in you:

In this tower, that we now view,

My friend’s prisoned, her name Blancheflor,

I so love the maid, furthermore,

That I have followed her to this land;

She was reft from me, you understand.

Come, aid me now, sir, of your grace,

For in your hands my life I place.

The end will be that either I gain

The maid, or die of grief, in vain.’

The porter hearing this was dismayed,

And saw that he had been betrayed.

‘Bemocked am I, I see it now;

Deceived by your gift, I avow!

Thus,’ he cried, ‘wronged by my greed,

For your gift, I’ll win death indeed.

And yet for this there is no recourse,

You have bound me, though not by force.

Whether ill or good come to me,

I must break one bond of loyalty,

And if I know aught, then say I,

All three of us are bound to die.

To your lodgings now be on your way,

And return again, on the third day.

Tis then I’ll address the matter.’

Floire gave answer to the porter:

‘Your terms are too severe, say I.’

The porter rendered him this reply:

‘I’ll set the course, for if we’re caught,

Tis death to me, and all unsought.’

Floire departed, the guard remained;

Each of the other thus complained,

The guard at length, the other in brief,

For Floire cared not, tis my belief,

What he must do to win his love;

Death he’d risk, mountains he’d move.

The End of Part II of ‘Floire et Blancheflor’