Robert d'Orbigny

Floire and Blancheflor: Part I

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2023 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction.

- Floire et Blancheflor.

- The author’s introduction.

- The author begins his tale.

- Of King Felis and of Blancheflor’s mother.

- Of the births of Floire and Blancheflor.

- Of their upbringing.

- Of the agreement to part the pair.

- Of the queen’s plan to send Floire to Montoire.

- Of Floire’s sorrow.

- Of the plan to sell Blancheflor into slavery.

- Of the price paid for the girl.

- Of Blancheflor’s empty tomb.

- Of Floire’s return from Montoire.

- Of Floire’s distress at the news of Blancheflor’s supposed death.

- Floire’s Lament.

- Of the enchanter Barbarin.

- Of Floire and the lions’ den.

- The king asks after Floire.

Translator’s Introduction

Floire et Blancheflor is a Medieval verse tale, from the Loire region of France, attributed to Robert d’Orbigny (or d’Orléans), possibly inspired by Neema and Noam one of the tales of the Thousand and One Nights, and propagated in a multitude of versions and languages. The tale first circulated in Europe around 1160AD, in an ‘aristocratic’ French version, and was extremely popular from c1200 to c1350AD.

The author’s introduction

Hear me, every noble lover,

All you that from love do suffer,

Listen, every youth and maiden,

All you, knights and ladies, listen!

If you but hearken to my tale,

You’ll learn of true love, without fail.

The tale of Floire, the infant king,

And of noble Blancheflor, I sing,

She of whom Bertha Bigfoot came,

That was Pepin’s wife, the same

That was mother of Charlemagne,

And once held France, and all of Maine.

Floire who was this maiden’s lover,

A pagan king did engender;

On Blancheflor, that loved him so,

A Christian count did life bestow.

This Floire then was of pagan stock,

Blancheflor of the Christian flock.

Floire was baptised, however,

For Blancheflor’s sake, his lover.

On the same day they saw the light;

Engendered, both, on the same night.

Once Floire became a Christian,

He was a wealthy nobleman,

For he was King of Hungary,

And Bulgaria’s fair country.

An uncle of his was king there

And he’d died lacking a male heir;

Floire was born of the sister,

So inherited through his mother.

If I can but render its glory,

Now shall you hear all the story.

‘King Fenis departs for battle’

The author begins his tale

I once entered in a chamber,

Twas on a Friday, after dinner,

To disport with the ladies there,

Of whom there were many and fair.

In this chamber there was a bed

With a silk cover overspread,

None finer in all Thessaly,

Rich it was, and great in beauty,

For it was worked with flowers too,

And was striped in yellow and blue.

There I sat on the bed, and heard

Two ladies exchanging a word.

A pair of sisters they did prove,

Speaking together of true love.

They were of noble lineage,

Both were lovely, fair and sage.

Of two lovers spoke the elder,

To the younger, her dear sister,

Of love between two children, though

A good two hundred years ago.

A clerk had told her it, she said,

For in a book the tale he’d read.

This tale she told most fittingly,

And you shall have it now from me.

Of King Felis and of Blancheflor’s mother

There was a king came out of Spain,

With a great company in his train.

In his ship he had crossed the sea,

And reached Galicia, for he

Felis, by name, was a pagan.

He’d journeyed to the Christian

Land, to make it his martial prey

And fire its towns, with fierce affray.

A month and fifteen days, fully,

The king occupied that country,

Nor was there a day but this king,

And his company, war did bring.

Towns he despoiled, while sparing none,

Loading his ships with all he’d won.

Till, for nigh fifteen leagues around,

Not a cow or ox could be found,

Not a town nor castle remained;

None sought the cattle he had claimed.

The whole country he’d set alight,

In which the pagans took delight.

Then the king sought his return,

To his quartermasters did turn,

To load the vessels; to his sight,

Summoning many a bold knight,

Forty at least, and cried: ‘Arm swiftly!

We’ll load without you, as quickly.

About the roads seek, high and low,

Rob all the pilgrims, you meet so.’

Off they went to the mountain high

Guarding the pass, beneath the sky,

That held the road, and pilgrims saw

Climbing the slope, both rich and poor.

They pursued and assailed them all,

And the pilgrims did so appal

Scant defence they offered, that day,

Surrendering, from fear, alway.

A Frenchman, in their company,

Was a knight, a man of chivalry,

To Saint James’ shrine he did go,

A daughter of his he had in tow;

To the Apostle she’d made a vow

To travel there, as she did now,

For her husband’s sake, who had died,

And then she was with child, beside.

The brave knight fought to defend her,

Yet they sought not his surrender,

Rather they struck him, left him dead,

And bore her to their lord instead.

To King Felis, they showed her then

He gazed at her, once and again,

And from her face could clearly see

She was of true nobility,

And declared she might be conveyed

To his queen, as a lady’s maid,

For she had requested the same

When o’er the sea, to rob, he came.

Thereupon, they boarded the fleet,

And soon had tautened every sheet.

The wind was fair and thereupon

Bore them joyfully on and on.

Not two days had passed, wholly,

Ere they reached their native country.

Soon the king attained the shore,

And all his company went before,

To Naples, that splendid city,

To which his brave vanguard, swiftly,

Brought the news that he had landed,

And, there, delight it commanded.

The citizens came to meet him, then

Expressed their deep pleasure again.

All felt joy that the company

Had arrived in their own country.

The king entered the town, gladly,

Summoning his company, shortly;

Then he shared the spoils, widely,

For he was generous and courtly.

For her part, to the queen, he gave

The lady, a gift that she did crave.

The queen was most pleased to see her,

And carried her off to her chamber.

She let her follow her own law

And honour her faith as before;

They oft spoke at ease together,

For she learnt French from the other.

The lady was good, courteous, fair,

And made herself loved by all there.

The queen her lady’s maid did prize,

And treated her as one full wise.

‘Floire and Blancheflor’s births’

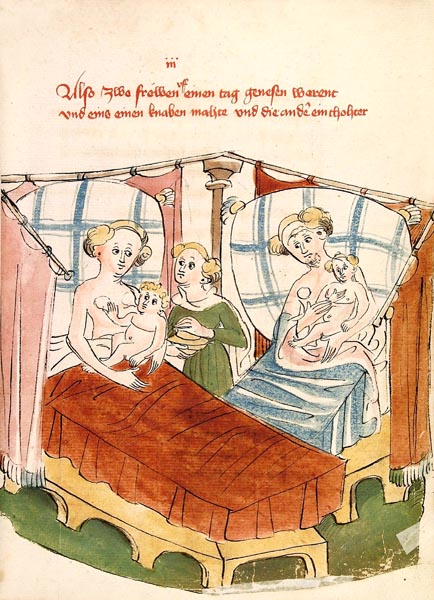

Of the births of Floire and Blancheflor

One day it chanced that the latter,

Was folding, in the queen’s chamber,

A tapestry the king had sent,

That their likenesses did present.

The queen suddenly saw her pale,

And shudder, as if she did ail,

Clasping both of her flanks tightly,

Shaking, and sweating profusely.

The queen recognised all her case,

(That she was with child) from her face.

The queen then asked how long ago

She’d received the amorous blow.

The date she knew; this she told her.

The queen, pondering the matter,

Said that she too was due to bear

A child, and the same date they would share.

For she knew well when it must be

Without recourse to prophecy.

The births took place on Palm Sunday,

So says those ladies’ history;

That was the day on which each bore

A child, whereby grief lay in store.

Travail, they knew, a deal of pain,

Ere the infants a breath did gain.

While a son the pagan queen bore

The Christian a daughter saw.

The children were named for the day,

The flowers, I mean, of Palm Sunday.

Blancheflor was the girl-child’s name,

Floire was that which the boy did claim,

The girl so named in the feast’s honour,

The boy by the king, his father.

The father loved his infant son;

The mother’s heart equally won,

He was cared for by the lady,

She who was both wise and lovely,

Raised thus, and nourished, by her,

(But for the breast-milk however:

A pagan held him to her breast,

Their faith no other wet-nurse blessed).

She raised him in noble manner,

Cherishing him dearly ever,

Much as she did her own daughter,

Nor knew which of them was dearer.

Together, the two of them did grow,

Till they were twelve years old or so,

Once they were weaned, not a thing

Parted them, sharing everything;

They slept together in one bed,

As one they drank, as one they fed.

At five years old, the thriving pair

Were fine, and noble, and most fair.

In all this world beneath the sun,

Lovelier children were there none.

When the king saw that his son

Was of an age where might be won

Knowledge of letters, he then sought

That such his son might now be taught.

Gaides was a master of arts,

None wiser living in those parts,

His parents for learning won fame;

Gaides then was his tutor’s name.

The king commanded his son to learn,

And he replied, for his heart did burn:

‘Sire, what then shall our Blancheflor do?

Shall she not learn her letters too?

Without her, I’ll not learn a thing,

No worth could any lessons bring.’

The king replied: ‘For love of you,

Blancheflor then shall learning accrue.’

The pair would be schooled together!

Great was their mutual pleasure.

Both learnt so much through the other

It was a marvel, none learnt better.

And they loved each other, that pair,

While both were more than passing fair.

No thought had either of those two,

Of which the other lacked a view.

As much as Nature would allow

They set their hearts on love, I trow.

In their books they had the wit

To search out many a trace of it.

Full many a pagan text, they found,

Spoke of love; there love did sound,

Therein they took such rare delight,

The art of love they savoured quite.

Those texts hastened on the thought

Of love in another sense than taught,

Another sense than the nourishment

Of knowledge, erst their sole intent;

Together they read, and understood;

The joys of love were fair and good.

When they were free of school each day

The kissed and they embraced, alway,

Together, they went here and there,

And their delight in love did share.

Of their upbringing

Now, Floir’s father had a garden,

And mandragora grew therein,

All the herbs, and every flower

Of diverse hues, to light the hour;

Many a tree and shrub rose there.

The birds, sweet songs of love did share.

There the children went each morn,

And breakfasted upon the lawn.

While they were eating and drinking,

The birds perched above were singing.

Birds sang about them, as they fed,

Such was the life those children led.

When they’d eaten, and so returned,

Great the joy their path had earned.

And then when to the school they came,

Their ivory tablets they would claim.

You might have seen them writing, there,

Love verses in the wax, with care!

Their styluses were silver and gold,

Their lettering skilful and bold.

Verses they penned to pass the hours,

Of love, the birdsong, and the flowers.

They wished for naught else, free of strife;

Full glorious it seemed, that life.

Thus, in a mere five years, or so,

Both of these young children did know

How to speak Latin, and to write

That language fair, on parchment white,

And understood many a counsel

Therein; few others learnt as well.

Of the agreement to part the pair

Now, the king knew the love his son

Held for Blancheflor; his heart she’d won.

He’d formed the intent, by this stage,

That when his son had come of age

And was ready to take a wife,

The maid must part from him, for life.

He went to the queen’s chamber,

That the two might speak together.

If she agreed with his desire,

He’d resolve the matter entire,

And then seek a wife for his son

Appropriate to such a one.

The queen saw that he was irate,

His colour changed from that of late,

For his face was suffused with blood,

His summons boded little good:

‘Lady,’ said he, ‘your son does ill,

His deeds accord not with my will.

Know that he will be lost, shortly,

Unless we take counsel, swiftly.’

‘How?’ cried the queen, ‘Why, and wherefore?’

‘Because of his love for Blancheflor,

The daughter of your lady’s maid.

He adores the girl, I’m afraid,

So much so that, while she’s alive

Their love will alter not but thrive,

Nor will he wed another, I claim,

But upon all his kin bring shame.

Indeed,’ said he, ‘without more ado,

Her head from her body I’d hew;

Then I’d see my noble son wed,

To some royal daughter instead.’

The queen reflected, thoughtfully,

And felt that he’d spoken wisely.

If he’d agree, she thought to aid

And save from death the little maid;

To both prevent her death, and yet,

Ensure that his wish might be met.

‘Sire,’ said she, ‘we must seek indeed

The best for our son, that is agreed,

That he should lose not honour and more,

Through his deep friendship with Blancheflor.

Yet that we separate the pair

Without causing our son despair

Would be the best it seems to me.’

The king replied, immediately,

‘Lady,’ he said,’ I quite agree,

There’s concord here twixt you and me.’

Of the queen’s plan to send Floire to Montoire

‘Sire,’ said she, ‘let us send our Floire

To acquire knowledge at Montoire.

Sybil, my sister is much there,

For that same town lies in her care.

And there she might seek occasion,

If she can, give him good reason

To forget this Christian, Blancheflor;

Some other shall solace him more.

Gaides must seem to be too ill,

To teach the boy his lessons still,

For we must make him understand

He is sent there at our command

To learn; and if Gaides seems well

Floire indeed may easily tell,

For they are good diviners who

Love with its insight doth imbue.

He will only grieve, I’m afraid,

If he gains sight there of the maid,

So, her mother illness must feign,

Must by her side, the girl, retain,

And say she’ll send on Blancheflor,

In a fortnight’s time, if not before.’

This they agreed should be done.

The king so commanded his son,

But, ere he did so, was content

To ask if he’d hear of his intent,

Then proceeded to state his wish.

Floire, replied, most troubled by this:

‘Sire,’ said he, ‘why must it be

That Blancheflor is parted from me,

With my tutor? Let her go too,

And learn all that you’d have me do.’

The king gave him no alternative,

If he would have his mother live

Not die of grief, but to agree,

Without objection; this did he.

He accepted all, not without pain.

The king ordered his chamberlain

To escort the lad with such might

And pomp, as for a prince seemed right.

Thus, they went to Montoire; there,

A castle stood both strong and fair.

‘Floire is received by Duke Joras’

Of Floire’s sorrow

Duke Joras was lord in that place;

And he received the lad with grace,

While his aunt too was filled with joy;

Yet naught that he heard pleased the boy,

Since, for lack of his Blancheflor, he

Scorned mere life, lost in misery.

Dame Sybil led him by the hand

To meet the maidens of that land,

Hoping he might forget love’s rule,

Or love, at least, in another school,

But naught he heard, and naught he saw,

Joyless without his sweet Blancheflor.

Much he heard, but little he learned;

Scant understanding sorrow earned;

Love within his mind, from the start

Had planted a tree within his heart,

One that grew and flourished there,

And whose sweet perfume filled the air,

Stronger than incense, any spice,

Clove, or ginger; beyond all price,

No other scent surpassed its worth,

Forgot all other joys on earth.

The fruit of that tree he now sought,

But twould be long, as he now thought,

Ere he might cull the sweet fruit there,

Ere he lay by Blancheflor the fair,

All alone, that he might kiss her,

And so, the tree’s fruit might gather.

Of the plan to sell Blancheflor into slavery

Floire waited, though pained thereby,

Till the fortnight had passed, say I.

When she’d arrived not, by its end,

He knew he’d not now see his friend,

That he was mocked, and with a sigh

Cried that, if she came not, he’d die.

He thus forwent all food and drink,

Of joy and play refused to think.

He embraced naught, not even sleep;

All thought his vow to die he’d keep.

The chamberlain informed the king;

Angered and aggrieved, by the thing,

He gave him leave to return to court,

While his wife’s good counsel he sought:

‘Indeed,’ said he, ‘this news so ill,

Deeply involves the maiden still.

Perchance it is by sorcery

She’s gained his love, and loyalty.

Let her be summoned, as I said,

And let her be parted from her head.

Once my son knows that she is gone,

Twill not be long he’ll brood thereon.’

The queen now replied to that same:

‘Sire, let her be sold, in God’s name,

For in this port dwells more than one

Wealthy merchant of Babylon.

Let her be taken there, and sold,

Thus, for the maid you’ll gain much gold.

Let her be led there, for she is fair;

Tis the last you’ll hear of her, I’d swear,

Thus, we’ll be rid of this ill maid,

Nor murder at our door be laid.’

‘Floire and Blancheflor on the Minneburg’

Of the price paid for the girl

The king, reluctantly, agreed.

He sent for a rich noble, at need;

Every aspect of trade he knew,

And spoke many a language too.

Yet twas not from covetousness

The king sold her; no more nor less

Than dead, he wished her, and not sold

For some hundred pieces of gold;

Yet twould be sin, so he let her go.

The merchant at the port did show

The maid, and offered her for sale,

To all who’d buy one sound and hale.

The girl commanded, in that place,

For she was passing fair of face,

Thirty gold coins, twenty silver also,

Twenty silk bales brought from Benevento,

Twenty fur mantles lined with silk,

Twenty blue tunics of like ilk,

And a costly cup, all of gold,

Taken from the treasure, of old,

Of some rich Roman emperor;

And none more costly wine ere bore.

This cup was marvellously made,

Thereon were rare designs portrayed,

Engraved there, and delicately;

Vulcan wrought it, most skilfully.

Upon the chalice there were shown

The walls of Troy, of solid stone,

The Greeks, assailing the city,

Striking at them in great fury,

As those within made stout defence,

Many a sharp missile firing thence.

On the rim, fair Helen was seen,

Whom Paris stole, Menelaus’ queen,

In white enamel fashioned there,

And set in gold, with wondrous care.

That king was pursuing her by sea,

In great distress, most furiously,

The Greek host following him, as one,

Led to Troy by King Agamemnon.

On the lid of the cup was shown

The goddess Venus, not alone,

But with Pallas and Juno too,

Whom Paris, in judgement, did view,

For they sought an apple as prize,

Competing there, before his eyes,

An apple of gold and, on it, writ

That the fairest should be granted it.

The three had brought the apple there,

And conjured him, if he should dare,

To grant it to the fairest of all,

She whose beauty did most enthral.

Each of them promised a reward

If he would yield them that award:

Juno of great riches made offer;

Pallas skill and wisdom; a lover

Venus declared he should acquire

The fairest a man might desire.

To her Paris granted the prize,

For rather than be rendered wise,

Or skilled, or gain great wealth, he chose

To win one fairer than the rose.

The artist had portrayed with skill

The love of Paris who had his will,

How he readied a ship and how

A breadth of water he did plough.

The cup was rich indeed, and fine,

And thereon a ruby did shine,

No fairer a gem neath the sky;

If he were there, a butler, say I,

No brighter a clarity could show,

No hyssop-wine had such a glow.

Above, a bird engraved in gold

With its claw this jewel did hold.

None ever saw a fairer wrought,

For none fairer was sold or bought;

It seemed alive; whoe’er did view

That bird, it seemed as if it flew.

Aeneas brought the chalice there,

When he fled Troy, and to the fair

Lavinia, in Lombardy,

He gave the thing; his love was she.

It passed to every ancestor,

The lords of Rome, each emperor,

And then was stolen by a thief,

Who bore it to the place, in brief,

Where the cup a merchant saw,

That gave it now to gain Blancheflor.

He bartered it, in fair exchange,

And was delighted, tis not strange,

For he believed double he’d gain

If he returned home; such was plain.

A favourable wind blew gently,

Back he sailed to his own country,

And made his way to Babylon,

Where to its lord he came anon.

Thus, to that lord the maid was sold

For seven times her weight in gold,

For she was lovely, right fair of face,

And nobility her form did grace.

The merchant was filled with delight,

For he’d gained great profit outright.

While to the king his noble brought

All that she’d fetched, and gave report.

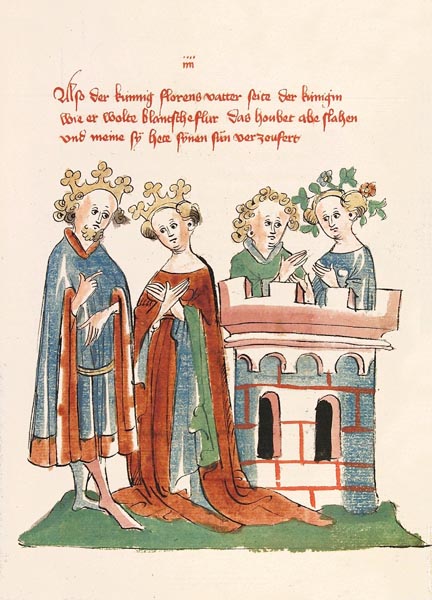

Of Blancheflor’s empty tomb

The queen gave thought to the matter,

And spoke to the king thereafter:

‘Sire, said she, what will you say

When Floire, our son, seeks, on a day,

Once to this place he is conveyed,

To know what happened to the maid?

When he asks about his lover,

What bold answer will you offer?

For, by my faith, I greatly fear,

He’ll die when he finds she’s not here.’

‘Lady,’ said he, ‘come, give some thought

As to how his comfort might be sought.’

‘Sire,’ she said, ‘now, listen to me:

A noble tomb we’ll raise, full swiftly,

Of marble, crystal, all over

Adorned with pure gold and silver.

“Fair Blancheflor is dead”, we will say;

And bring him comfort, on that day.’

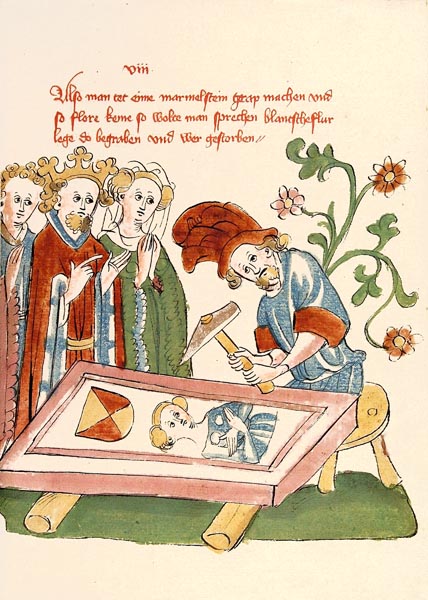

So, they summoned many a mason,

And many another worthy person,

Skilled artisans, to raise a tomb,

Finer than any, you may assume.

All of the workmanship was fair;

Gold and silver adorned it there.

No beast or bird beneath the sky

But to that tomb they did apply,

Every serpent that one could name,

Every fish, that sea or lake did claim.

Before a church, beneath a tree,

That marble tomb, the eye might see.

And above it was set a stone,

A Frisian artisan worked, alone.

The stone he set above it, there,

Was made of marble, fine and rare;

Of red and yellow, green and blue,

It shone in the sun, right rich in hue.

And a frieze about it, pierced inlay,

As employed in Solomon’s day.

Within that the enamelling was

All in silver, and gold, and glass.

On the tomb, in gold, cast with care,

Were two children, tender and fair;

No eye saw ever, wrought in gold,

Such fine likenesses, e’en of old.

One of the two seemed Floire, and naught

A closer likeness could have caught.

The other cast was fashioned too

Like fair Blancheflor, the likeness true.

And the image of fair Blancheflor

Held out a single flower, before

Floire, her true love; there it did hold,

That lovely form, a rose of gold.

Floire too held, before his face,

A lily of pure gold, in place.

Opposite each other, the pair,

Noble of countenance, sat there.

The child Floire wore, upon his brow,

A glowing ruby I avow,

And one might see, in darkest night

A league around, by its fair light.

Within the tomb four pipes were set,

Fine and sound, from which air might jet

Through four nozzles, and, when the air

Flowed in the pipes, the statues there

Of those children touched together,

Kissed, and as if by magic arts,

Spoke all that lay in their two hearts.

To Blancheflor, Floire, this speech did make:

‘Kiss me, my fair one, for love’s sake.’

Blancheflor replied, kissing him too:

‘More than life itself, I love you.’

So that pair spoke, when the air blew,

When those statues embraced anew,

And then, when the air ceased to flow,

They ceased speaking, that pair, also.

So sweetly they gazed at each other

It seemed those two smiled together,

At the head of that tomb, a tree

Was planted, beautiful to see;

Lovely it was, and in full leaf,

With flowers fair beyond belief,

Springing from every branch also,

And all were fresh, and white as snow.

The name of this tree was ebony,

And all was alight upon that tree.

At the tomb’s foot, like to the sun,

A crimson terebinth stood, and none

Fairer neath the sky, I’d suppose,

For it was lovelier than the rose.

To the right, a tree gave holy oil;

To the left, balsam was the spoil.

And ne’er was there a scent so sweet,

No flower today could compete,

For, on the one side, balsam flowed,

The other holy oil bestowed.

They who planted those four trees,

In seeking, thus, the gods to please,

Made such supplication there,

They flowered every year as fair.

Amidst the trees’ rich flowering

Ever a thousand birds did sing,

And yielded such sweet melodies

As ne’er were heard, but midst those trees.

Such sweet melodies filled the air,

From the little birds that sang there,

That if heard by youth or maiden,

Who by ardour had been smitten,

With the sweet songs that they heard,

They, seized by love so, in a word,

Ran to clasp each other, swiftly,

And kiss one another, sweetly.

If any heard the singing who

The pains of love, as yet, ne’er knew,

Yet from the air did sweetness reap,

In that moment, they fell asleep.

And there, amidst those four trees, stood

The tomb so wrought, and no man could

Conceive a tomb for any maid

As fair as the one in that glade.

With rich borders it was bounded,

By rare enamels was surrounded.

Gems of power, in past days formed,

Many a miracle there performed.

Sapphire, jacinth, chalcedony,

Emerald, sardonyx, and many

A pearl, coral, and chrysolite,

Diamond, and amethyst bright,

Rare beryl, rose-quartz, they were there,

Jasper, topaz, and agates fair.

Letters engraved, in niello,

Of Arabian gold’s rich yellow,

Were wrought upon it; thus, pure gold

To the reader did her name unfold:

‘Within this tomb lies fair Blancheflor,

She whom Floire did greatly adore.’

‘The king and queen prepare Blancheflor’s tomb’

Of Floire’s return from Montoire

Now Floire returned, as soon as he

Was allowed, to his own country.

From his palfrey swift descending,

In the courtyard, before the king.

Welcomed by his father and mother,

Twas Blancheflor he first asked after.

They were slow to yield a reply.

Entering a chamber, by and by,

To the maid’s mother he did appeal,

To whom his heart he did reveal:

‘Lady, where is my love?’ he cried,

‘She is not here,’ the dame replied,

‘Where, then?’, ‘I know not’, ‘Summon her, then.’

‘I know not whence.’ ‘You jest, again!’

‘Is she hiding?’ ‘Sire, no indeed.’

‘By God,’ said he, ‘here’s an ill deed!’

When she could hide it no longer,

Piteously, in tears she did utter

These words, while weeping: ‘She is dead.’

‘Can this be true?’ ‘Tis true,’ she said.

‘Where is her corpse?’ ‘To the churchyard, go.’

‘When did she die? ‘Eight days ago,

Blancheflor died, Sire, all is true,

And her death was for love of you.’

She lied about the matter though,

For the king made her say twas so.

Of Floire’s distress at the news of Blancheflor’s supposed death

When Floire was told that she was dead,

He was filled with sorrow and dread,

His face grew pale, all strength failed him,

He fell fainting, his sight was dim.

The Christian dame, troubled thereby,

From sheer fright, now uttered a cry.

The cry was loud, and the king heard,

Who hurried there, with nary a word,

While the queen ran to seek her son

Both were concerned, feeling as one.

He fainted thrice for an hour or so,

And when he revived, wept, in woe.

‘Death, why neglect me thus,’ he said,

‘Now that my own true love is dead?

Lady,’ said he, ‘since you know where

My fair love lies, come lead me there.’

The king it was led him to the tomb,

Floire went there, as if to his doom,

And saw twas writ that this Blancheflor

Loved but one, whom she did adore.

He read the words three times, but fell

Fainting, ere a word he could tell.

Thereafter, he sat upon the stone

About the tomb, and there made moan.

‘Floire faints on hearing of Blancheflor’s alleged death’

Floire’s Lament

The lad wept bitterly once more,

And, thus, lamented his Blancheflor.

‘Blancheflor! Blancheflor! They ever say,

We were born on the very same day;

On the same night were engendered,

By the count our mothers rendered.

We were raised together, closely,

So, twould be best, it seems to me,

Since we two issued forth as one,

If to join you I’m swiftly gone.

Oh, Blancheflor, so fair of face!

No maid in this age had such grace,

Such wisdom, or such loveliness,

As you who did all three possess.

Dead is she, that most precious gem!

Nor shall we seek her like again.

Fair one, none could fathom surely,

No tongue could describe, your beauty,

For whatever might come to mind

To silence would ever be consigned.

Who’d describe, her face, head, hair,

Would own to a wisdom most rare.

That face of such delicate hue!

Oh, none were born to equal you,

That lived in such sweet chastity;

O, you, the very form of beauty.

You were humble and honourable,

And to the needy most merciful,

Loving all, both small and great,

Of your goodness, whate’er their fate.

Fair one, in our confidences we

Exchanged good counsel privately,

Telling our news both ill or good,

In that Latin both understood.

Ah Death! E’er seeking harm are you,

So evil, and contrary too,

That when summoned you come not;

Those who love you, you have forgot,

Those who hate you, you love the more,

Leading them to that fatal shore.

Wisdom against your power doth fail,

Prowess nor possessions avail.

To folk of worth who ought to live,

Mortal suffering and pain you give;

To those that should live in delight

You grant not joy but endless night.

Yet when some old beggar you see,

Trembling with age, and misery,

Who summons you, then, merciless,

You give no heed to their distress.

When you took my sweet love from me,

Who wished to live, wrong you did me,

And wrong again is this you do,

Who come not, when I summon you.

Death, I follow you, while you flee;

I seek you, while you hide from me.

By God, one that of love would die,

You shall not long evade, say I.

When a poor wretch summons you,

Then your chariot flies from view,

And yet when you’d regain your ground,

The die is cast, swift end is found.

By my faith, I’ll ask you no more,

But, this eve, make my own death sure,

For life to me must hated be,

Now my sweet love is reft from me.

My soul my love’s will now pursue,

In Elysian Fields; seek me anew,

Where I now go to seek my flower,

For Love holds us yet in his power.

Swiftly, I go where she has gone,

For, swift as I can, I follow on.

And soon her love my love shall see;

In Elysium, where she waits for me.’

Of the enchanter Barbarin

Such was the plaint uttered by Floire,

On returning home, from Montoire.

He had no joy by night or day,

His life wretched in every way.

If he’d but had a naked dart,

He’d have plunged it into his heart,

It weighed on him that he had none.

The king begged him to have done

With sorrow, and the queen likewise,

Naught kept the tears though from his eyes.

He could not forget his Blancheflor;

Night and day, he but wept the more.

The king summoned an enchanter;

Among his peers, no wizard finer

Was to be found in those days;

Folk would tremble at his displays.

Wise in all magic was this fellow,

He could make stones rise and follow;

He could make a cow fly, or a mare;

Or an ass, on the harp, play an air.

For twelve gold coins, he’d willingly

Cut off his head, for all to see;

Severing his head, at a blow,

He’d hand it to a witness so,

Then the open mouth would demand:

‘Have you a head there in your hand?’

‘Yes, by God!’ the fellow would cry,

But when upon it he turned his eye,

He held but a lizard, or a snake;

Such was the magic he could make.

On entering the hall, smoke arose,

Issuing forth from the wizard’s nose,

Such that none could see his form,

For about him its clouds did swarm.

When he sought a breath to claim,

He lit the palace with bright flame.

(So, they might see what he could do)

His actions troubling to view.

On seeing the flames, many ran,

Fleeing the palace, to a man.

And once they’d exited the place,

Called the wizard a vile disgrace.

Though when they chose to look behind,

Nary a flame there could they find.

The wisest held the thing mere folly!

Returning to the hall full swiftly,

Monks and nuns, their eyes now saw,

And each nun gripped a monk, and bore

A knife, and held it to his throat;

Before their eyes this sight did float.

Now they saw them and now did not.

For mere enchantment was their lot,

And thus, they saw twas but folly.

The king called out, approvingly:

‘Barbarin, work magic for me,

And I’ll reward you, handsomely.’

‘Gladly,’ he said, ‘I’ll work a thing.

Be seated all, and you, great king,

Be seated, on the instant now;

A bird I’ll summon, if you’ll allow.’

The king sat; a bird came in sight.

Listen to what its beak held tight!

The bird it was a turtle-dove,

And it held a roundel, from above,

The roundel was wrought of topaz,

And yet it seemed as clear as glass,

And it was twelve-foot all around,

And therein a gold form was found,

Shaped like a man who, on command,

Played on a harp, held in his hand;

The Lay of Orpheus he played,

And those that heard the sounds he made,

Ever followed their rise and fall;

Twas found harmonious by all.

Then before them was the sight

Of a marvellous mounted knight,

His body was not two foot high,

But his legs were full long, whereby

He was a good six feet or so.

A melody began to flow,

That pleased them all exceedingly,

Though Floire heard naught, nor did see,

The others all joyed at what they saw,

Floire could not; twas his Blancheflor

Kept his eyes from these delights,

From the hall he fled, and such sights.

Of Floire and the lions’ den

The fact was perceived by the king.

‘Barbarin, he said, ‘are you listening?

Halt your magic, reveal no more.’

‘Gladly, Sire, all’s now as before.’

At once he ceased his conjuring;

His magic, he to an end did bring.

It seemed to all, before their sight,

The whole palace was filled with light,

The ground trembled, or so they thought,

All fell to earth, with terror fraught.

None was so brave they trembled not,

All but Floire who had quit the spot.

They shook with fear, then fell asleep,

While Floire, upon his way, did keep.

He could not forget his lover,

In his mind, he thought upon her;

She seemed to say: ‘Sweet friend, dear Floire,

You must return now to Montoire.’

Floire reflecting on this, apart,

Was grieved and felt sad at heart,

Many a time he was seen to faint,

And on reviving made complaint:

‘Sweet Blancheflor, my lovely friend,

For love of you, this life he’d end,

Your Floire!’ he cried, in discontent.

About the silent halls he went,

While all within the palace slept,

Both great and small, and ever wept.

He thought to die and end his strife,

Lacking the talent, thus, for life.

While he was wandering, grieving so,

He came to a pit; there, below,

The king had two great lions penned,

Both strong and fierce; to make an end,

He thought he might anger the pair,

Then leap into the den, and there

Be slain, and eaten, and none say nay.

He thus approached, without delay.

But before he sought to enter there,

He uttered this plaint, in deep despair:

‘Our sovereign Father, who commands

All things, for all lies in your hands,

That made Adam in your semblance,

(Thereafter granting him abundance,

Fruits of the earth, in great plenty,

All there within his grasp, wholly,

Every fruit, for none was hidden,

Only the apple then forbidden)

Who ate of the tree, for his sin,

And, hence, our errors did begin,

Plunging us in darkness, the more,

May I and my sweet friend, Blancheflor,

Dwell in Elysium, we two,

Our Lord above, I beg of You.’

Floire, ending his words in a sigh,

Entered the pit, with this loud cry:

‘Blancheflor, my sweet and lovely friend,

For you, of this life, I make an end.’

Floire went towards the creatures;

They lay down, belied their natures.

My lords, we who read his story

Find that Floire was granted glory;

The beasts lapped at his hands and feet,

Their pleasure seemingly complete.

But Floire, at this, feeling but woe,

Called angrily to the lions so:

‘Lions, come, slaughter me now;

And no sight of it, here, allow

To the king; come, slaughter this Floire;

Let him think me gone to Montoire!

When the king takes a thief or two,

Their deliverance rests with you.

So, deliver me, and my flesh devour;

Lions, my death lies in your power!’

Floire’s heart was filled with ire and woe.

The lions their sharp claws did show,

For other weapons they had none,

But they touched him with nary a one,

Struck not, despite all he could do,

Cried Floire: ‘Perverse creatures are you,

You do wrong in not slaying me,

I’m worth more than a thief, truly,

And far better than such to eat,

Though you resist such tender meat!’

Floire remained, thus, in great woe.

Now hear of the wizard; for, lo!

He ended the enchantment then,

The king and lords awoke, again.

They were awake, but scarce knew where,

Feeling but mocked by this affair.

The king asks after Floire

The king demanded of Barbarin:

‘Have you seen Floire, here within?’

‘Yes sire, though he’s now lost to you.

I hope you shall not find it true,

But he has leapt in the lions’ pit.’

The king now fell into a fit,

His barons fainted, dropped to the floor,

Fearing that Floire was now no more.

The king began to shout aloud:

‘My barons, tarry not; in a crowd

Rush those lions, and slay the pair.

Wretches,’ cried he, ‘what repair

If we have lost fair Floire, my son?

Twas ill he returned; yet tis done,

And now he’s lost beyond recall,

Hapless the prey on which you fall,

And great the prize you gain, truly!’

To the pit he ran, instantly,

And in delaying not, he found

That Floire was alive, safe and sound.

Imagine the king’s profound delight

As he dragged him forth to the light.

He led him swiftly to the hall.

His mother looked pale, amidst them all.

Father and mother were filled with joy

Yet Floire’s heart did but pain enjoy.

He determined, ere night, he must die,

And so, erase his failure thereby.

That thought so weighed upon his mind,

Nor joy nor delight could Floire find.

The End of Part I of ‘Floire et Blancheflor’