Geoffrey Chaucer

Troilus and Cressida

Book I

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2001, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

1.

Troilus’s double sorrow for to tell,

he that was son of Priam King of Troy,

and how, in loving, his adventures fell

from grief to good, and after out of joy,

my purpose is, before I make envoy.

Tisiphone, do you help me, so I might

pen these sad lines, that weep now as I write.

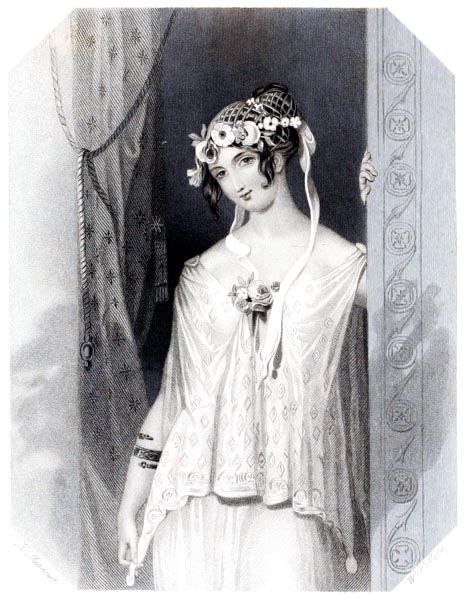

‘Tisiphone takes revenge on Athamas and Ino’

Crispijn van de Passe (I), 1602 - 1607

The Rijksmuseum

2.

I call on you, goddess who does torment,

you cruel Fury, sorrowing ever in pain:

help me, who am the sorrowful instrument

who (as I can) help lovers to complain.

Since it is fitting, and truth I maintain,

for a dreary mate a woeful soul to grace,

and for a sorrowful tale a sorry face.

3.

For I, who the God of Love’s servants serve,

not daring to Love, in my inadequateness,

pray for success, though death I might deserve,

so far am I from his help in darkness.

But nevertheless, if this should bring gladness

to any lover, and his cause avail,

Love take my thanks, and mine be the travail.

4.

But you, lovers that bathe in gladness,

if any drop of pity is in you,

remember all your past heaviness

that you have felt, and how others knew

the same adversity: and think how, too,

you have felt Love dare to displease

if you have won him with too great an ease.

5.

And pray for those that may have been

in Troilus’s trouble, as you’ll later hear,

that love bring them solace in heaven:

and also, for me, pray to God so dear

that I might have the power to make clear

such pain and woe as Love’s folk endure

in Troilus’s unhappiest adventure.

6.

And also pray for those that have despaired

of love, and never can recover:

and also those by falsity impaired,

by wicked tongues, beloved one, or lover,

And so ask of God the benign mover,

to grant them soon to pass from this place,

that have despaired of Love’s grace.

7.

And also pray for those that are at ease,

that God might grant them to persevere,

and send them power their lovers to please,

that it might, for Love, be worship and a pleasure.

For that I hope will be my soul’s best measure:

to pray for those who Love’s servants be,

and write their woes, and live in charity.

8.

And so as to have, for them, compassion

as though I were their own brother dear,

now listen to me, with all good intention:

for now I’ll go straight to my matter, here,

in which you may the double-sorrows hear

of Troilus’s love of Cressid, she, by his side,

and how she forsook him before she died.

9.

It is well known how the Greeks, strong

in arms, with a thousand ships, went

there to Troy, and the city long

besieged, near ten years without stint,

and in diverse ways, and with sole intent,

to take revenge for the rape of Helen, done

by Paris, they strove there as one.

10.

Now it fell out that in the town there was

living a lord, of great authority,

a powerful priest who was named Calchas,

in science a man so expert that he

knew well that Troy would fall utterly,

by the answer of his god that was called thus:

Dan Phoebus or Apollo Delphicus.

11.

So when this Calchas knew by his divining,

and also by answer from this Apollo,

that the Greeks would such a host bring

that, through it, Troy must be brought low,

he planned out of the town to go.

For he well knew by prophecy Troy would

be destroyed, whether or not it should.

12.

For which purpose to depart quietly

was the clear intent of this far-seeing man,

and to the Greek host, most carefully

he stole away: and they with courteous hand

gave him both worship and service, and

trusted that he had cunning in his head

for every peril they might have to dread.

13.

A noise rose up when this was first spied,

through all the town, and generally was spoken,

that Calchas was fled as a traitor and allied

with them of Greece: and vengeful thoughts were woken

against him who had so falsely his faith broken:

and it was said: ‘He and all his kin, as one,

are worthy to be burnt, skin and bone.

14.

Now Calchas had left behind, in this mischance,

all ignorant of this false and wicked deed,

his daughter, who was doing great penance:

for she was truly in fear of her life, indeed,

like one that does not know what advice to heed,

for she was both a widow and alone,

without a friend to whom she dared to moan.

15.

Cressida was the name this lady owned:

and to my mind, in all of Troy’s city

none was as fair, surpassing everyone.

So angelic was her native beauty,

that like a thing immortal seemed she,

as does a heavenly and perfect creature

sent down here to put to shame our nature.

‘Cressida’

The Stratford gallery (p233, 1859) - Palmer, Henrietta Lee, b. 1834

Internet Archive Book Images

16.

This lady that all day heard in her ears

her father’s shame, his falsity and treason,

nearly out of her wits with sorrows and fears,

in her full widow’s habit of silken brown,

before Hector on her knees she fell down,

and with a piteous voice, tenderly weeping,

asked mercy of him, her own pardon seeking.

17.

Now this Hector was full of pity by nature,

and saw that she was distressed by sorrow,

and that she was so fair a creature.

Out of his goodness he cheered her now

and said: ‘Let your father’s treason go

with all mischance: and you yourself in joy

live, while you wish, here with us in Troy.

18.

And all the honour that men have as yet

done you, as fully as when your father was here,

you shall have, and your body shall men protect,

in so far as I can enquire or hear.’

And she thanked him humbly, full of cheer,

and would have all the more, if it had been his will,

and took her leave, and home, and held her still.

19.

And in her house she lived with such company

as her honour obliged her to uphold:

and while she was dwelling in that city

kept her estate, and both of young and old

was well beloved, and well, of her, men told,

but whether she had children then or no,

I have not read, therefore I let it go.

20.

Things fell out as they do in war’s affair,

between those of Troy and the Greeks, oft:

for some days the men of Troy it cost dear,

and often the Greeks found nothing soft

about Troy’s folk. And so Fortune up aloft,

and down beneath, began to wheel them both

after their course, while they were still wrath.

21.

But how this town came to destruction

it falls not within my purpose to tell:

for it would be here a long digression

from my matter, and delay you too long as well.

But the Trojan exploits as they fell

out, in Homer, Dares, or Dictys, might

whosoever read them, as they write.

22.

But though the Greeks them of Troy shut in,

and besieged their city all about,

they would not leave off their old religion,

so as to honour their gods, being truly devout:

but foremost in honour, without doubt,

they had a relic, called the Palladion,

that they trusted beyond all other ones.

‘Diomed with the Palladium’

Six Greek sculptors (p127, 1915) - Gardner, Ernest Arthur, 1862-1939

Internet Archive Book Images

23.

And so it befell, when there came the time

of April when the meadow was spread

with new green (of lusty Ver the prime)

and sweet smelling flowers, white and red,

in sundry ways worshipped (as I have read)

the folk of Troy, in their observance old,

and used Palladion’s feast to hold.

24.

And to the temple, with best garments on,

many went in a crowd to the rite,

to hear the service for Palladion:

And in particular many a lusty knight,

many a lady fresh, and maiden bright,

full well arrayed, the highest and the least,

yea, both for the season and the feast.

25.

Among these other folk was Cressida

in widow’s habit black: but nonetheless,

just as our first letter is now an ‘A’,

in beauty first, so stood she matchless.

Her good looks gladdened all the press.

Never was seen a thing praised so far,

nor, under black cloud, so bright a star,

26.

as Cressid was, as folk said, everyone,

that beheld her in her black dress:

and yet she stood humbly and still alone,

behind other folk, in little space or less,

and near the door, ever in shame’s distress,

simple in clothing, with an air of cheer,

with a confident look and manner.

27.

This Troilus, used, as he was, to guide

his young knights, led them up and down,

through that large temple, on every side,

beholding all the ladies of the town,

now here, now there, for he owned

no task that might rob him of his rest,

but began to say whom he liked least or best.

28.

And in his walk he soon began to watch

if knight or squire of his company

began to sigh or let his eyes catch

on any woman that he could see.

He would smile and hold it as a folly,

and say to him: ‘God knows, she sleeps softly,

free of love for you, while you turn endlessly.

29.

I have heard tell, by God, of your way of living,

you lovers, and your mad observance,

and such labour as folk have in the winning

of love: and in the keeping, what grievance:

and when your prey is lost, woe and penance.

O very foolish, weak and blind you be:

there is not one who warned by another can be.’

30.

And with that word he began to wrinkle his brow,

as if to say: ‘Lo, is this not wisely spoken?’

At which the god of Love showed anger’s token,

ready with spite, set on revenge, all woken.

He showed at once his bow had not been broken:

for suddenly he hit him, through and through:

who can pluck as proud a peacock as him too.

31.

O blind world! O blind intention!

How often all the effect falls contraire

of arrogance and foul presumption:

for caught are the proud, and the debonair.

This Troilus has climbed up the stair,

and little knows he must again descend.

But, every day, things that fools trust in end:

32.

as proud Bayard begins to shy and skip

from the right course ( perked up by his corn),

till he receives a lash from the long whip:

then he thinks ‘Though I prance before,

all others, first in the traces, fat and newly-shorn,

yet I am but a horse, and a horse’s law

I must endure, and with my fellows draw.’

33.

So fared it with this fierce and proud knight

though he a worthy king’s son were,

and thought nothing had ever had such might

against his will, so as his heart to stir,

yet with a look his heart had taken fire,

that he, but now, who was most in pride above,

suddenly was most subject unto love.

34.

Thereby take example of this man,

you wise, proud and worthy folks all,

to scorn Love, which so soon can

the freedom of your hearts take in thrall

For ever it was, and ever it shall befall,

that Love is he that all things may bind,

for no man may undo the law of kind.

35.

That this be true is proven, and true yet:

for this I mind you know, all or some.

Men do not think folk can have greater wit

than they whom Love has most overcome,

and strongest folk are with it stunned,

the worthiest and greatest of degree:

this was and is, and still men shall it see.

36.

And truly it is fitting it be so,

for the very wisest have with it been pleased:

for they that have been foremost in woe

with love have been comforted most, and eased.

And often it has the cruel heart appeased,

and worthy folk made worthier of name,

and causes most to dread vice and shame.

37.

Now since it may not be well withstood,

and is a thing so virtuous, of its kind,

do not refuse to be bound by Love,

since as he pleases he may you bind.

The branch is best that can bend and be entwined,

than that that breaks: and so with you I plead

to follow him that so well can you lead.

38.

But to go on telling, in more detail,

of this king’s son of whom I told,

and let other things be collateral:

of him I mean my tale to unfold,

both of his joy and of his cares cold:

and all his work as touching on this matter,

since I began it I’ll thereto refer.

39.

Within the temple he went him forth, toying,

this Troilus, with everyone about,

on this lady and now on that looking,

whether she were of the town or without:

and it fell by chance that through a crowd

his eye pierced, and so deep it strayed

that on Cressid it smote, and there it stayed.

40.

And suddenly he found himself marvelling,

and began to look more closely with careful eye.

‘O mercy, God’: thought he, ‘where were you living,

that are so fair and goodly to describe?’

Therewith his heart began to spread and rise,

and he soft sighed, lest him men might hear,

and caught again at his first look of cheer.

41.

She was not among the least for stature,

but all her limbs so well answering

to womanhood, that no creature

was ever less mannish in seeming:

and the pure air of her being

showed well that men in her might guess

honour, estate, and womanly nobleness.

42.

To Troilus, right wondrously, all in all,

her being begins to please, her looks appear

somewhat disdainful, for she lets fall

her glance a little aside in such manner,

as if to say: ‘What may I not stand here?’

And after that her face fills with light,

that he never thought to see so good a sight.

43.

And from her look, in him there grew the quick

of such great desire and such affection,

that in his heart’s bottom began to stick

of her his fixed and deep impression:

And though before he had gazed up and down,

he was glad now his horns in to shrink:

he hardly knew how to look or wink.

44.

Lo, he that declared himself so cunning,

and scorned those that love’s pains drive,

was full unaware that Love had his dwelling

within the subtle streams of her eyes,

that suddenly he thought he felt dying

straight, with her look, the spirit in his heart.

Blessed be Love, that can folk so convert!

45.

She, this one in black, pleasing to Troilus,

above all things he stood to behold:

of neither his desire, nor why he stood thus,

did he show a sign, or by a word told,

bur from afar, the same aspect to hold,

on other things his look he sometimes cast

and again on her, while ceremonies last.

46.

And after this, not completely bested,

out of the temple all easily he went,

repenting him that he had ever jested

at Love’s folk, lest, fully, the descent

of scorn fell on himself: but what it meant,

lest it were known on every side,

his woe he began to dissimulate and hide.

47.

When he was from the temple so departed

he straight away to his palace turns,

right with her look pierced through, and through-darted,

feigning that all in joy he sojourns:

and all his looks and speech hide his concerns,

and also, from Love’s servants all the while,

to mask himself, at them he began to smile.

48.

And said: ‘Lord! You all live in such delight,

you lovers: for the most cunning of you, in it,

that serves most attentively and serves aright

has harm from it as often as he has profit:

you are repaid again, yea, and God knows it!

Not well for well, but scorn for good service:

in faith, your order is ruled in good wise!

49.

In unsure outcome lie all your attentions,

except in some small points where you strive,

and nothing asks for such devotions

as your faith does, and that know all alive.

But that is not the worst, as I hope to thrive:

but if I told you the worst point I believe,

though I spoke truth, you would at me grieve.

50.

But take this: what you lovers often eschew,

or else do with good intention,

often your lady will it misconstrue

and call it harm, in her opinion:

And yet if she for other reason

be angered, she will soon complain to you,

Lord! Well is him that might be of your crew.’

51.

But for all this, when he could he chose his time

to hold his peace, no other point being gained.

For love began his feathers so to lime,

that scarcely to his own folk he feigned

that other busy needs him detained.

For woe was him: he knew not what to do,

but told his folk, wherever they wished, to go.

52.

And when he was in his chamber alone,

down upon the bed’s foot he took his seat,

and first he began to sigh, and often groan,

and thought on her like this so without cease,

so that as he sat awake his spirit dreamed

that he saw her in the temple, and the same

true manner of her look, and began again.

53.

So he began to make a mirror of his mind,

in which he saw all wholly her figure:

and so that he could well in his heart find

that it was to him a right true venture

to love such a one, and, dutiful what’s more

in serving her, he might still win her grace,

or else hold one of her servants’ place.

54.

Imagining that labour nor pain

might ever for so good a one be lost

as she, nor himself, for his desire, be shamed,

if all were known, but valued and borne

above all lovers more so than before:

so he argued in his beginning,

all unaware of his woe coming.

55.

So he purposed love’s craft to pursue,

and thought that he would work most secretly,

first to hide his desire, closely mewed,

from every person born, and completely,

unless he might gain anything thereby:

remembering that love too widely blown

yields bitter fruit, though sweet seed be sown.

56.

And over all of this yet more he thought

what to speak of, and what to hold in,

and what might urge her to love he sought,

and with a song at once to begin,

and began aloud, himself out of sorrow to win.

For, with good hope, he gave his full assent

to loving Cressid, and nothing to repent.

57.

And of his song not only the sense,

as my author wrote, named Lollius,

but plainly, save our tongue’s difference,

I dare say truly all that Troilus

said in his song, lo! every word thus

as I shall say it: and who might wish can hear,

lo! in the next verse he can find it here.

58.

‘If no love is, O God, what feel I so?

And if love is, what thing and which is he?

If love be good, from whence comes my woe?

If it be evil, a wonder, thinketh me,

when every torment and adversity

that comes of it seems savoury I think,

for I ever thirst the more the more I drink.

59.

And if for my own pleasure I burn,

whence comes my wailing and complaint?

If harm delights me, why complain then?

I know not why, unwearied, I still faint.

O living death, O sweet harm strangely meant,

how, in me, are you there in such quantity,

unless I consent that so it be?

60.

And if I so consent, I wrongfully

complain, indeed: buffeted to and fro,

all rudderless within a boat am I

amid the sea, between winds two

that against each other always blow.

Alas! What is this wondrous malady?

Through heat of cold, through cold of heat I die.’

61.

And to the god of Love thus said he

with piteous voice: ‘O lord, now yours is

my spirit, which ought yours to be.

I thank you, lord, that have brought me to this:

but whether goddess or woman, she is

I know not, that you cause me to serve,

but as her man I will ever live and love.

62.

You stand in her eyes so mightily,

as in a place worthy of your line,

and so, lord, if my service or I

may please you, so be to me benign:

For my royal estate I here resign

into her hand, and full of humble cheer

become her man, as to my lady dear.

63.

In him, never deigning to spare blood royal,

the fire of love, saved from which God me bless,

spared him not in any degree, for all

his virtue and his excellent prowess:

but held him as his slave in low distress

and burned him so, in various ways, anew,

that sixty times a day he lost his hue.

64.

So much, day by day, his own thought,

for lust of her, began to quicken and increase,

that every other charge he set at nought:

Therefore often, his hot fire to cease,

to see her goodly looks he began to press:

for to be eased thereby he truly yearned,

and ever the nearer he was, the more he burned.

65.

For ever the nearer the fire, the hotter it is:

this, I think, know all this company.

But were he far or near, I dare say this,

by night or day, for wisdom or folly,

his heart, that is his breast’s eye,

was ever on her, that fairer was when seen

than ever Helen was, or Polyxene.

‘Achilles and Polyxena’

Franz Ertinger, after Peter Paul Rubens, 1679

The Rijksmuseum

66.

Ever of the day there passed not an hour

but that to himself a thousand times he said:

‘Good goodly one, whom I serve for and labour

as best I can, now, would to God, Cressid,

you might take pity on me before I am dead.

My dear heart, alas! my health, my beauty,

my life is lost lest you take pity on me.’

67.

All other fears were from him fled,

both of the siege and his own salvation,

in him desire no other offspring bred

but arguments to this conclusion,

that she on him would have compassion,

and he to be her man while he might endure:

lo! such his life, and from his death the cure.

68.

The sharp fatal showers, that their arms proved,

which Hector and his other brethren showed

were not to make him even once moved:

and yet was he, wherever men walked or rode,

one of the best, and longest time abode,

where peril was, and ever took such trouble

in arms, that to think of it was a marvel.

69.

But no hatred of the Greeks he had,

nor any rescue of the town,

made him, there in arms, battle-mad,

but only, lo, this one reason,

to please her better through his renown:

From day to day in arms he so sped,

that all the Greeks, like death, did him dread.

70.

And henceforth, as love deprived him of sleep,

and made his food his foe, and as his sorrow

began to multiply, so that to whoever might keep

a watch, it showed in his hue, eve and morrow,

therefore the name he began to borrow

of another sickness, lest, of him, men learned

that the hot fire of love him burned.

71.

And said he had a fever and fared amiss:

but how it was, I cannot truly say,

whether his lady understood not this,

or feigned she did not, either way,

I think that not for a single day

it seemed did she consider what he sought,

nor his pain, nor whatsoever he thought.

72.

But then fell to this Troilus such woe,

that he was almost mad: for ever his dread

was this, that she had loved some man so

that she would never of him take any heed:

for thought of which he felt his heart bleed.

Nor of his woe dared he begin

to tell, for a whole world to win.

73.

But when he had a space from his care,

he began, like this, to himself to complain:

he said: ‘O fool, you are now in the snare,

who formerly mocked at love’s pain:

now you are caught, now gnaw at your own chain:

you were accustomed each lover to reprehend

for that from which you cannot yourself defend.

74.

What will every lover now say of thee

if this be known, but ever in your absence

laugh in scorn and say: “Lo, there goes he

that is the man of such great sapience,

that held us lovers least in reverence:

now, thanks be to God, he may go in the dance

of those that Love moves feebly to advance.

75.

But O, you woeful Troilus, if only God would,

since you must love because of your destiny,

set your heart on such a one that should

see all your woe: even though she lacked pity:

but all so cold in love towards thee

your lady is as frost in winter moon,

and you consumed, as snow in fire is, soon.”

76.

Would God I were arrived in that port

of death, to which my sorrow will me lead!

Ah, lord, to me it would be a great comfort:

then I’d be done languishing in fear indeed

for if my hidden sorrow blows on the breeze

I shall be mocked a thousand times

more than that fool whose folly men tell in rhymes.

77.

But now help me God, and you sweet, for whom

I moan, caught, yea, never a man so fast.

O mercy, dear heart, and help me from

death: for I, while my life may last,

more than myself will love you to the last.

And with some friendly look, gladden me, sweet,

though with never another promise me you greet.’

78.

These words, and full many another too,

he spoke, and called ever in his complaint

her name, so as to tell her his woe,

till he near drowned in salt tears, faint.

All for nothing, she did not hear his plaint:

and when he thought about that folly

a thousand-fold his woe began to multiply.

79.

Bewailing in his chamber thus alone,

a friend of his, that was named Pandarus,

came in unnoticed and heard him groan,

and saw his friend in such care and distress.

‘Alas!’ he said, ‘what has caused all this?

O mercy, God! What mishap may this mean?

Have the Greeks made you so, ill and lean?

80.

Or have you some remorse of conscience,

and have now fallen into some devotion,

and wail for your sin and your offence,

and have, through fear, caught contrition?

God save them that have besieged our town

and can so send our jollity amiss,

and bring our lusty folk to holiness!’

81.

These words he said, and that was all,

so that he might him angry make,

and with anger down his sorrow might fall,

for the time being, and his courage wake.

But well he knew, as far as tongues spoke,

there never was a man of greater hardiness

than him, or one who more desired worthiness.

8.

‘What chance,’ said Troilus, ‘or what venture

has led you to see my languishing,

because I am refused by every creature?

But for the love of God, at my crying,

go hence away: for certainly my dying

will distress you, and I needs must die:

therefore go now, there is no more to say.

83.

But if you think that I am sick for dread,

it is not so, and therefore scorn not:

there is something of which I take heed

more than anything the Greeks have wrought,

which is my cause of death, for sorrow and thought.

But though of its secret I do not now divest,

do not be angered. I hide it for the best.’

84.

This Pandarus, nearly melted from pity and ruth,

often repeated: ‘Alas! what may this be?

Now friend,’ he said, ‘if ever love or truth

has been, or is, between you and me,

never do me such a cruelty

to hide from your friend such great distress

do you not know that it is I, Pandarus?

85.

I will share with you all your pain,

if it be that I can do you no comfort,

as is a friend’s right, truth to say,

to share woe just as to happiness support.

I have and shall, through true or false report,

in wrong and right, loved you all my life.

Hide not your woe from me: tell it outright.

86.

Then began this sorrowful Troilus to sigh,

and he said thus: ‘God grant it is for the best

to tell it you: since it is as you like,

I will tell it, though my heart should burst:

and I well know you cannot give me rest.

But lest you think I do not trust in thee,

now listen, friend, for thus it stands with me.

87.

Love, against which whosoever defends

himself most, him least of all avails,

with despair so sorrowful me offends,

that straight unto death my heart sails.

And desire so burningly me assails,

that to be slain would be a greater joy

to me than to be king of Greece or Troy.

88.

Let this suffice, my true friend Pandarus,

that I have said, for now you know my woe:

And, for the love of God, my cold sadness,

hide it well, I tell it to no one more.

For harms might follow, more than two,

if it were known: but be you in gladness,

and let me die, unknown by my distress.’

89.

‘How have you thus, unkindly and so long

hid this from me, you fool?’ said Pandarus:

Perhaps, it may be, you after someone long,

so that my advice now might be help to us.’

‘This were a wondrous thing,’ said Troilus:

‘You could never in love your self do this:

how the devil can you bring me to bliss?’

90.

‘Yea, Troilus, now listen,’ said Pandarus,

‘fool though I be: it often happens so,

that one who through excess does evil fare

by good counsel can keep his friend from woe.

I have myself often seen a blind man go

where one fell down who could look clear and wide:

so a fool may often be a wise man’s guide.

91.

A whetstone is no carving instrument,

and yet it makes sharp carving tools:

and where you see my time has been misspent

avoid you that, as though ’twere taught in schools.

So, often wise men have been warned by fools.

If you do so, your wit’s made well aware

that by its contrary is everything declared.

92.

For how might sweetness ever have been known

to him that never tasted bitterness?

No man may be inwardly glad, I own,

that never was in sorrow or some distress.

Ever white by black, and shame by worthiness,

each set by the other, more so seem,

as men may see: and so the wise deem.

93.

Since this, of two contraries, is the law,

I, that have so often in love found

grievances, ought to be able, all the more,

to counsel you in those that you confound,

and you ought never to with ill abound

if I desire with you to share

your heavy charge: it will be less to bear!

94.

I know well that it is with me

as when, to your brother Paris, a shepherdess

who was named Oenone,

wrote in complaining of her wretchedness.

You saw the letter that she wrote, I guess.’

‘No, never yet, indeed,’ said Troilus.

‘Now,’ said Pandarus, ‘listen: it was thus:

95.

“Phoebus, that first found the art of medicine,”

she wrote, “and could find, for each one’s care,

remedy, and aid by herbs he was knowing in:

yet to himself his cunning was impaired:

for love had him so bound in a snare,

all for the daughter of the King Admete,

that all his craft could not his sorrow beat.”

96.

‘Right so, I am, unhappily for me:

I love one best, and that afflicts me sore.

And yet perhaps I can give aid to thee,

if not myself: reproach me no more.

I have no cause I know it well to soar

as a hawk does that has a mind to play:

but for your help still something I can say.

97.

And of one thing right sure you can be,

that even though I die in torture’s pain,

I indeed shall never betray thee.

No, by my troth, I do not intend

to keep your from your love, though it were Helen,

who is your brother’s wife, if I should know it is.

Let her be who she be, and love her as you wish.

98.

Therefore of my friendship be full assured,

and tell me plainly what is your end

and the final cause of woe that you endure:

for, do not doubt, what I intend

is not in any way to reprehend

you, in so speaking, since no one can part

a man from love unless that’s in his heart.

99.

And know well that both of these are vices –

to mistrust all, or else offer all love, -

but I know that the mean of both no vice is,

since to trust some people is to prove

one’s truth, and for you I would remove

your wrong belief, and make you trust that there is

one you can tell your woe to: and tell me if you wish.

100.

The wise man says: “Woe to him who is alone,

since, if he falls, he has no help to rise.”

But since you have a friend, tell your moan.

For it is not the easiest way to my eyes

to win love, so they teach us, the wise,

to wallow and weep like Niobe the queen,

whose tears can yet in marble still be seen.

101.

Let be your weeping and your dreariness,

and let us lessen woe by other speech:

so may your woeful time seem the less:

delight not in woe your woe to seek,

as do those fools that their sorrows increase

with sorrow, when they meet misadventure,

and do not wish to find another cure.

102.

Men say: “To wretchedness it is consolation

to see another fellow in his pain.”

That ought well to be our opinion,

since both you and I of love complain.

So full of sorrow am I, truth to say,

that certainly no more hard misfortune

can sit on me, because there is no space.

103.

Please God, you are not afraid of me,

that I would entice away your lady:

you know yourself whom I love, indeed,

as I best can, a long while since you see.

And since you know it is not guilefully,

and since I am he you trust the most,

tell me some part, since all my woe you know’st.’

104.

Yet Troilus, for all this, no word said:

But long he lay, as still as dead he were.

And after this he lifted up his head,

and to Pandarus’s voice he lent his ear.

And he cast up his eyes, so that in fear

was Pandarus, lest than in a frenzy

he should fall, or else soon die:

105.

And cried: ‘Awake!’ wondrously sharp:

‘What? Do you slumber in a lethargy?

Or are you like an ass, to the harp,

that hears sound when men the strings play,

But in his mind, of that, no melody

sinks in to gladden him, since he

so dull is of his bestiality.’

106.

And with that Pandar his words constrained:

but Troilus yet him no word answered,

since to tell was not his intent,

to any man ever, for whom it was he suffered.

For it is said: ‘Man often makes a rod

with which the maker is himself beaten

in sundry ways,’ as the wise know for certain,

107.

And particularly, to his mind’s telling,

what touches on love should a secret be:

since of itself it would enough out-spring

unless it were governed carefully

and sometimes it is craft to seem to flee

from the thing which in effect men hunt close.

All this Troilus began in his heart to gloss.

108.

But nonetheless when he had heard him cry

‘Awake!’ he began to sigh wondrous sore,

and said: ‘Friend, though I silent lie,

I am not deaf: now peace and cry no more,

since I have heard your words and your lore:

But suffer me my mischief to bewail,

since your proverbs may me not avail.

109.

Nor have you now another cure for me:

and I will not be cured, I will die.

What know I of the queen Niobe?

Forget your old examples, pray, say I.’

‘No,’ said Pandarus, ‘that is why I say,

such is a fool’s delight to sit and weep

his woe, but never a remedy to seek.

110.

Now I know that reason in you fails.

But tell me: if I knew who she were,

for whom in all this distress you ail,

would you dare to let me whisper in her ear

your woe (as you dare not yourself for fear),

and beseech her to have some pity on you?’

‘Why no,’ he said, ‘by God, and by my truth!’

111.

‘What? not if it were as carefully,’ said Pandarus,

‘as though my own life rested on this need?’

‘No, for certain, brother,’ said Troilus.

‘And why?’ – ‘Because you never could succeed.’

‘Are you sure of that?’ – Yes, that is so, indeed,’

said Troilus, ‘whatever you would see done,

she’ll not, by such a wretch as I, be won.’

112.

Said Pandarus: ‘Alas! what may this be,

that you are in despair so causelessly?

What? Does the lady not live? Bless me!

How do you know that you are so unworthy?

Such evil’s not always sent so incurably.

Why, do not deem impossible your cure,

since things to come are often at a venture.

113.

I well grant you that you endure woe

as sharp as does Tityus in hell,

whose stomachs birds tear at for evermore,

those they call vultures, as books tell.

But I cannot endure that you dwell

in so foolish an opinion,

that of thy woe there is no termination.

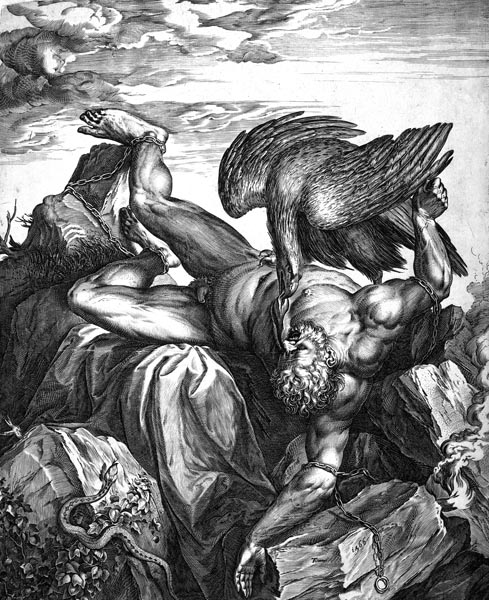

‘Tityus in hell’

Cornelis Cort, after Titiaan, 1566

The Rijksmuseum

114.

But because of your coward’s heart,

and your anger and foolish wilfulness,

through mistrust, you will not your sorrows impart:

nor in your own cause do business,

even to give a reason more or less,

but lie there as he that to nothing can stretch.

What woman could ever love such a wretch?

115.

How can she think otherwise of your death

(if you die, and she not know why that is)

but that through fear you yielded up your breath

because the Greeks have so besieged us ?

Lord! What reward then you will have from this!

This she will say, and all the town as one:

“The wretch is dead, the devil have his bones.”

116.

You may weep here alone and cry and kneel:

but love a woman so she knows it not,

and she’ll repay you with what you cannot feel:

unknown, unkissed, and lost, is what’s unsought.

What! Many a man has love full dearly bought,

who has his lady twenty winter’s blessed,

yet never has his lady’s mouth he kissed.

117.

What? Should he therefore fall into despair,

or be cowardly to his own ruin,

or slay himself, though his lady still be fair?

No, no, but ever and a day be fresh and green

to serve and love his dear heart’s queen,

and think it is a prize (her to serve)

a thousand times more than he can deserve.

118.

And of that word took heed our Troilus,

and thought now what a folly he was in,

and how the truth was told by Pandarus,

that by slaying himself he could not win,

but both do an unmanly thing and a sin,

and of his death his lady not to blame,

since of his woe she’d never know the name.

119.

And with that thought he began to sorely sigh,

and said: ‘Alas! What is it best to do?’

To which Pandar answered: ‘If you like,

the best is for you tell me your woe,

and have my promise, if you do not find this so,

that I am your helper before too long,

have me drawn in pieces, and then hung.’

120.

‘Yes, so you say,’ said Troilus then: ‘Alas!

But, God knows, it is none the better so:

it would be hard to help in this case,

since I well know that Fortune is my foe,

none of the men that can ride or go,

may the harm of her cruel wheel withstand:

for as she wills she plays with free or bond man.

121.

Said Pandarus: ‘Then you blame Fortune

in anger, yes, for the first time I see.

Do you not know that Fortune is common

to every manner of man in some degree?

And yet you have this comfort, God help me,

that as her joys must vanish and be gone,

so must her sorrows pass, every one.

122.

For if her wheel ever ceased to turn,

she would no longer Fortune be.

Now, since her wheel may not sojourn,

it may be that her mutability

the thing yourself would wish will do for thee:

or that she be not far from you in helping?

Perhaps you may have cause to sing.

123.

And so will you accept what I beseech?

let your woe be, and your gazing at the ground:

For he who wants help from his leech,

he must first reveal his wound.

To Cerberus in hell may I be bound,

if, were it all for my sister, all your sorrow,

I would not will that she be yours tomorrow.

124.

Look up I say and tell me who she is

now, so that I can satisfy your need.

Do I know of her? For love of me tell this,

then I would have more hope that I’d succeed.’

Then began Troilus’s vein to bleed,

for he was hit, and grew all red with shame.

‘Aha!’ said Pandar, ‘here begins the game.’

125.

And with that word he began him to shake

and said: ‘Thief! You shall her name tell.’

But then poor Troilus began to quake

as though men were to lead him into hell,

and said: ‘Alas! Of all my woe the well:

then is my sweet foe called Cressid,’

and almost from fear of that word was dead.

126.

And when Pandarus heard her name given

Lord, he was glad and said: ‘Friend so dear,

now you are right, by Jupiter’s name in heaven,

Love has set you right: be of good cheer:

since of good name and wisdom and manner

she has enough, and also gentleness.

If she is fair, you know yourself, I guess.

127.

I have never seen one more bounteous

in her position, nor gladder, nor of speech

a friendlier, nor a more gracious

to do good, nor less had need to seek

for what to do: and all this better to be

high in honour, as far as she may stretch,

a king’s heart seems by hers that of a wretch.

128.

And therefore look you of good comfort to be:

for certain, this is the main point itself

of noble and well ordered courage, namely

for a man to be at peace with himself.

So ought you, for it is nothing else

but good to love well, and in a worthy place:

you ought not to call it fortune, but grace.

129.

And also think (and with this joyful be)

that since your lady is virtuous in all,

so it follows that there is some pity

amongst these virtues in general:

and therefore see that you, in special,

seek out nothing that is against her name:

for virtue does not stretch itself to shame.

130.

But it is well that I was born

to see you set in so good a place:

for, by my truth, in love I would have sworn

you never would have won to so fair a grace.

And you know why? Because you used to chase

away Love in scorn, and for spite him call

“Saint Idiot, lord of these fools all.”

131.

How often have you made your foolish japes,

and said that Love’s servants everyone

in foolishness were all God’s apes:

and some would munch their food alone,

lying abed, and pretend to groan,

and some you said had a pale fever,

and prayed to God they should not recover:

132.

And some of them took on about the cold,

more than enough, so you said full often:

and some have often feigned, and told

how they are awake, when they sleep soft:

and so they would have talked themselves aloft,

and nevertheless were fallen at the last,

so you said, and jested quick and fast.

133.

Yet you said that for the most part

these lovers used to speak in general,

and thought that it was a surer art

for not failing with one to attempt them all.

Now might I jest about you, if I should at all.

But nevertheless, or may I hope to die today,

you are none of those, that I dare say.

134.

Now beat your breast and say to the god of Love,

“Your pardon, lord! For now I repent

if I mis-spoke, since now I also love.”

Say it with all your heart, and good intent.’

Said Troilus: ‘Ah, lord! I do consent,

and pray to you my jests to forgive,

and I will jest no more while I live.’

135.

‘You speak well,’ said Pandar: ‘and now I hope

that you have the god’s wrath all appeased:

and since you have wept many a drop,

and said those things with which your god is pleased,

now let God grant only that you are eased:

and think that she from whom comes all your woe

hereafter may your comfort be also.

136.

For the same ground that bears the baneful weed.

also bears the wholesome herbs, as often

near the foul nettle, rough and thick, breed

the roses sweet, and smooth, and soft:

and near the valley rises the hill aloft:

and after the dark night the glad morrow:

and also joy is near the end of sorrow.

137.

Now look to be moderate with your bridle,

and, for the best, wait for the tide,

or else all our labour will be idle:

he hastes well who wisely can abide.

Be diligent and true, and all thoughts hide.

Be joyful, free, persevere in your service,

and all will be well, if you work like this.

138.

But he who is scattered in every place

is nowhere whole, as wise clerks say in this:

what wonder is it such-like gain no grace?

And see you how it goes with some men’s courtship?

As well go plant a tree or herb like this

and on the morrow pull it up alive:

it is no wonder it can never thrive.

139.

And since the god of Love has you bestowed

in a place fitting for your worthiness,

stand fast, since to a good port you have rowed:

and for yourself, despite your heaviness,

always hope on: for unless dreariness

or over-haste, ill-luck to our two labours send,

I hope of this to make a good end.

140.

And do you know why I am less concerned

of this matter with my niece to treat?

because I have heard it said by the wise and learned,

“There never was man or woman made complete

that was disinclined to feel love’s heat,

celestial love, or love of humankind”:

Therefore some grace I hope in her to find.

141.

And to speak of her especially,

thinking of her beauty, her youthful brow,

it does not suit her to love celestially

as yet, though she would and could I allow.

But truly, it suits her best right now

a worthy knight to love and cherish,

and if she does not, I call that a vice.

142.

So I am, and will be always, ready

to take some pains for you in this service:

since to please you both thus hope I

afterwards: since you are wise in this,

and can your council keep, and so it is

that no man shall the wiser of it be,

and so we may be gladdened, all three.

143.

And, by my truth, right now, I have of thee

a good opinion in my mind, I guess:

and what it is I wish you now to see.

I think since Love, out of his goodness,

has converted you from wickedness,

that you will be the best pillar, I believe,

of all his creed, and most will his foes grieve.

144.

For reason why: see how these wise clerks,

that have erred the most against the law

and have been converted from their wicked works

through God’s grace, who wishes them to Himself to draw:

then are they folk who hold God most in awe,

and are the strongest in faith, I understand,

and can an error best of all withstand.’

145.

When Troilus had heard that Pandar assented

to be his helper in loving of Cressid,

he became by woe, as it were, less tormented,

but his love grew hotter, and so he said,

with sober look, although his heart played:

‘Now blissful Venus help, before I die

you Pandar to deserve my thanks thereby.

146.

But, dear friend, how will my woe be less

till it be done? And good friend tell me this:

how will you tell her of me and my distress?

Lest she be angered, this my great fear is,

or will not hear or credit how it is.

And that it comes from you, all this I fear,

from her uncle, she’ll not such things hear.’

147.

Said Pandarus: ‘You might have as great a care

lest the man might fall out of the moon!

Why, lord! I hate in you this foolish fare!

Why - attend to that which you have to do!

By God’s Love I ask from you a boon,

leave me alone, and it will work for the best.’

‘Why, friend,’ he said, ‘well do then as you wish.

148.

‘But listen, Pandar, one more word: I would

that you should not suspect in me such folly

that I might desire for my lady what could

touch on harm or any villainy:

for certainly I would rather die

than that she, of me, things understood

except those which might work to her good.

149.

Then Pandar laughed and at once replied:

‘And I your pledge? Fie! All men wish so:

I would not care if she stood and heard

what you have said: But farewell, I will go:

Adieu! Be glad! God speed us both two!

Give me this labour and this business,

and from my efforts yours be all that sweetness.’

150.

Then Troilus began to his knees to fall,

and seizing Pandar in his arms held him fast,

and said: ‘Now fie on the Greeks all!

Yet, by faith, God will help us at the last:

and be certain, if my life shall last,

and with God’s help, lo, some of them shall smart:

and pardon me that this boast leaves my heart.

151.

Now Pandar, I can nothing more say,

but – wise, you know, you may, you are all!

My life, my death, whole in your hand I lay:

help now,’ he said. ‘Yes, by my truth, I shall.’

‘God repay you friend: in this so special,’

said Troilus, ‘that you recommend me

to her that to the death may command me.’

152.

Pandarus, then desirous to serve

his good friend, then said in this manner:

‘Farewell, and know I will your thanks deserve:

have here my promise, good tidings you will hear.’ –

And went his way thinking on this matter,

and how he might best ask her for grace,

and find a time for it, and a place.

153.

For any man that has a house to found

does not rush the work he must begin

with rash hand, but waits a moment and

sends his heart’s intent out from within

first of all his purpose for to win.

All this Pandar in his heart thought

and planned his work out wisely before he wrought.

154.

But Troilus then no longer lay down,

but up at once upon his steed, the bay,

and in the field he played the lion:

Woe to the Greek that met with him that day.

And in the town, from that time, he in his way

so winning was, and won him such good grace,

that each man loved him that looked on his face.

155.

For he became the friendliest of men,

the gentlest and also the most free,

the sturdiest, and best knight, then

that in his time was, or might ever be.

Gone were his jests and his cruelty,

his loftiness and his aloofness,

and each of them changed to a goodness.

156.

Now let’s leave Troilus awhile, he’s found

to be like a man who is hurt sore,

and is somewhat eased of his wound,

but is not well until he heals the more:

and, an easy patient, obeys the lore

of him that sets about his cure:

and so his own fortune does endure.

End of Book One.

Notes

BkI:1 Tisiphone: One of the three Furies, The Eumenides, in Greek mythology. The Three Sisters, were Alecto, Tisiphone and Megaera, the daughters of Night and Uranus. They were the personified pangs of cruel conscience that pursued the guilty. (See Aeschylus – The Eumenides.) Chaucer invokes her as his Muse, and invokes her again in Bk IV:4 along with her sisters.

BkI:21 Dares and Dictys: Two supposed eye-witnesses of the war at Troy. To Dares the Phrygian was ascribed De Excidio Troaie Historia (The History of the Fall of Troy) a late sixth century Latin text. To Dictys the Cretan was ascribed the Ephemeris Belli Troiani (A Calendar of the Trojan War) a fourth century text. These works are the basis of the medieval Trojan legends.

BkI:23 Palladion: The Palladium, the sacred image of Pallas, supposed to save Troy from defeat, and stolen by Ulysses and Diomede.

BkI:25 First Letter: A reference to Anne of Bohemia wife of Richard II, indicating the poem was written after their marriage in 1382.

BkI:32 Bayard: A generic name for a carthorse.

BkI:57 Lollius: Chaucer’s work was based not on the works of the fictitious Lollius, but on Boccaccio’s poem Il Filostrato, deriving some lines and words closely from the Italian and also from a French translation by Beauveau.

BkI:58 ‘If no love is..’: An adaptation of Petrarch’s poem 132 from the Canzoniere. (S’amor non è, che dunque è quel ch’io sento?)

BkI:65 Polyxene: Polyxena was one of the daughters of King Priam of Troy and Queen Hecuba, and sister of Troilus. See Ovid’s Metamorphoses Bk XIII:429-480. She was sacrificed to appease the ghost of Achilles.

BkI:131 Tityus: The giant, a son of Earth and Jupiter, sent to Hades to be tortured for attempting to rape Latona. See Ovid’s Metamorphoses Bk IV:416-463. Vultures feed on his liver, which is continually renewed. Bk X:1-85. His punishment in the underworld ceases for a time at the sound of Orpheus’s song.