François-René de Chateaubriand

Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem et de Jérusalem à Paris

(Record of a Journey from Paris to Jerusalem and Back)

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2011 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

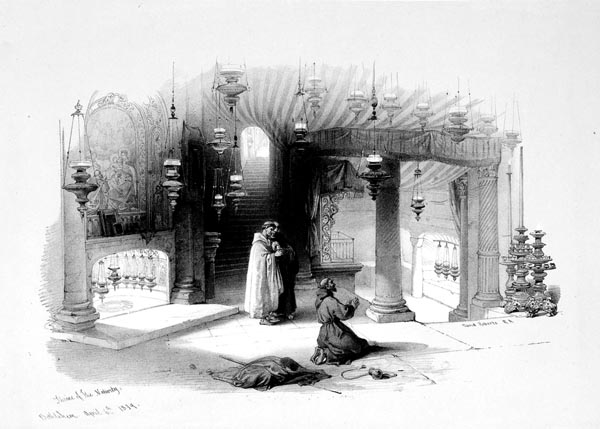

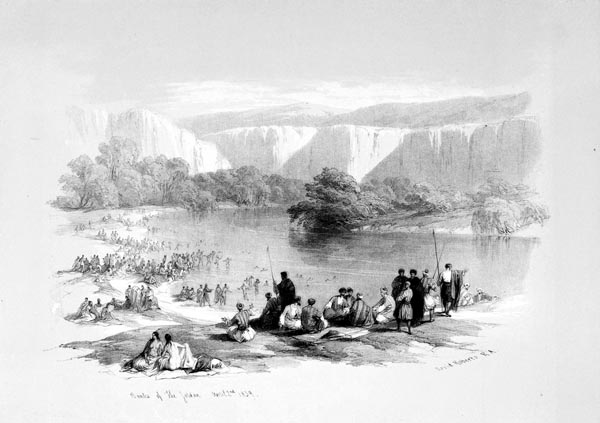

Part Three: Rhodes, Jaffa, Bethlehem and the Dead Sea

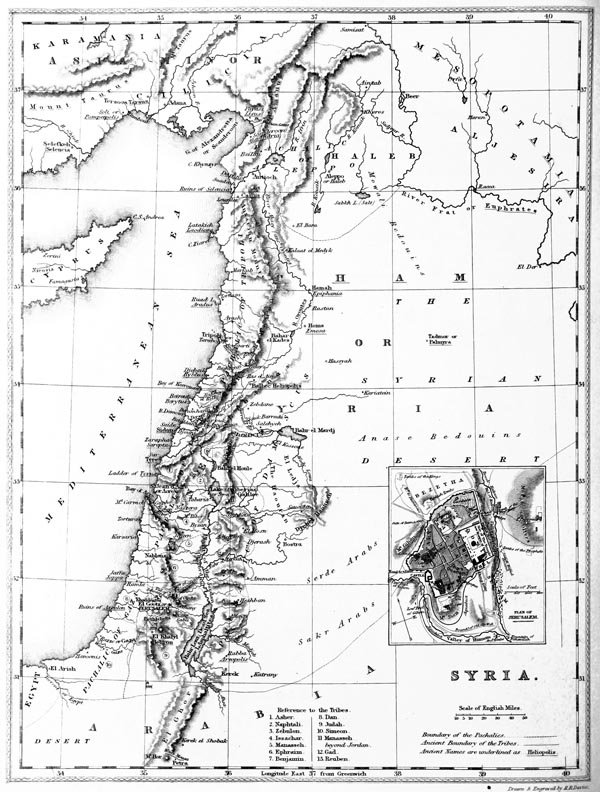

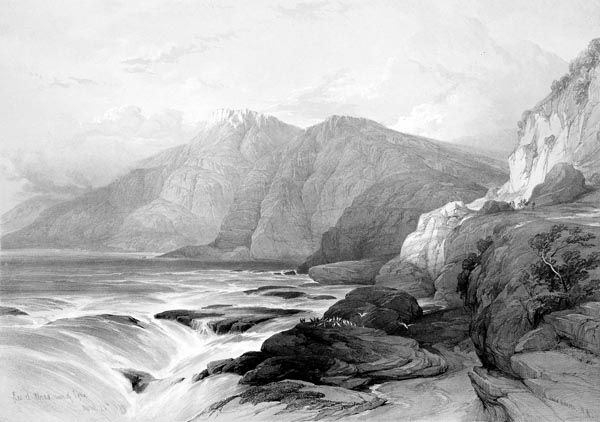

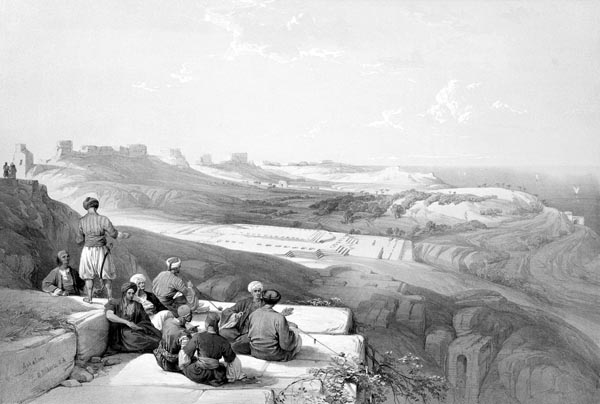

‘Syria’

Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor - John Carne, Thomas Allom, William Henry Bartlett, William C. Stafford (p164, 1861)

The British Library

About two hundred of us passengers were aboard, old and young; men, women, and children. A host of sleeping-mats were visible, ranged along both sides of the deck. Strips of paper, stuck to the bulwarks, indicated the names of the mats’ owners. Each pilgrim hung their staff, their rosary, and a small cross, by their bed. The captain’s cabin was occupied by the priests leading this band of pilgrims. At the entrance to this cabin, two ante-chambers had been constructed. I had the honour of utilising one of these black holes, about six-feet square, with my two servants; a family occupied the other apartment opposite. In this species of republic, each household arranged things as they wished: women nursed their children; men smoked or prepared their dinner; priests chatted together. The sounds of mandolins, violins and zithers were heard on all sides. They sang, danced, laughed and prayed. Everyone was full of joy. They cried: ‘Jerusalem’, at me, pointing southwards, and I answered: ‘Jerusalem!’ Indeed, had it not been for our fears, we would have been the happiest people in the world; but at the least wind, the sailors hauled at the sheets, and the pilgrims shouted: ‘Christos, kyrie, eleison!’ The storm past, we recovered our daring.

I failed, moreover, to note the chaos of which some travellers speak. We were, on the contrary, very decent and orderly. On the first evening of our departure, two priests conducted prayers, which everyone attended with great reverence. The ship was blessed, a ceremony renewed after every storm. The chanting of the Greek Church possesses considerable sweetness, but lacks gravity. I noted something singular: a child would begin the verse of a psalm in a high tone, and sustained it on a single note, while a priest sang the same verse to a different tune, in canon, that is to say commencing the phrase when the child had already passed the middle. They perform an admirable Kyrie eleison: it is simply a single note held by different voices, some bass, others treble, executing andante (slowly) and mezza voce (at half-volume), the octave, fifth and third. The effect of this Kyrie is overwhelming in its sadness and majesty: it is doubtless a remnant of the ancient singing of the primitive Church. I suspect the other psalms belong to this singing style introduced to the Modern Greek liturgy around the fourth century, and of which St. Augustine had good reason to complain.

The day after we left, I was again seized with a quite violent fever: I was forced to remain on my bed. We swiftly crossed the Sea of Marmara (Propontis). We passed the peninsula of Cyzicus (Kapu-Dagh) and the mouth of the Aegospotamos. We rounded the headlands of Sestos and Abydos: Neither Alexander and his army, Xerxes and his fleet, the Athenians and the Spartans, nor Hero and Leander, could overcome the headache that overwhelmed me, but when, on the 21st of September, at six in the morning, I was told that we were about to double the castle of the Dardanelles, the fever was driven off by memories of Troy. I crawled on deck; my first glance took in a high promontory crowned by nine wind-mills: it was Sigeus. At the foot of the promontory I could see two tumuli, the tombs of Achilles and Patroclus. The mouth of the Simois was to the left of the modern castle; farther off, and behind us, towards the Hellespont, the headland of Rhaetaeus appeared, and the tomb of Ajax. In the dip rose the Mount Ida range, whose slopes, as seen from the point where I stood, seemed gentle and harmonious in colour. Tenedos rose in front of the ship’s bows: Est in conspectu Tenedos (Virgil: Aeneid II.21).

I walked about with my eyes on this scene, and my gaze returned, despite myself, to the grave of Achilles. I repeated these verses of the poet:

‘And on a headland thrusting into the wide Hellespont we, the great host of Argive spearmen, heaped a vast flawless mound above them, so it might be seen far out to sea by men who live now and those to come.’

άμφ' αύτοίσι δ' έπειτα μέγαν καί άμύμονα τύμβον

χεύαμεν Ἀργείων ίερός στρατός αίχμητάων

άκτη έπι προύχούση, έπί πλατεί Ἑλλησπόντόω,

ώς κεν τηλεφανής έκ ποντόφιν άνδράσιν είη

τοὶς οί νυν γεγάασι καὶ οί μετόπισθεν έσονται.

(Homer: Odyssey:XXIV:80-84)

The pyramids of the Egyptian Pharaohs are of little consequence, compared with the glory of the mounds of turf that Homer sang, and that Alexander ran around (Plutarch: Alexander 15.8).

At that moment, I felt the remarkable effect of the power of our feelings and the influence of the soul over the body. I had arrived on deck filled with fever: my headache suddenly vanished; I felt my strength revive, and, what is more extraordinary, all my mental faculties. True, twenty-four hours later the fever had returned.

I had nothing with which to reproach myself: I had formed the intention of travelling through Anatolia to the plain of Troy, and you have seen what compelled me to abandon my project; I wanted to reach it by sea, but the captain of our vessel stubbornly refused to land me there, though our agreement obliged him to do so. At the time, these annoyances caused me much grief, but now I console myself. I had made so many errors in Greece, that the same fate perhaps awaited me at Troy. At least I have retained all my illusions regarding the Simois; moreover I have had the good fortune to salute that sacred soil, to have seen the waves that bathe it, and the sun that lights it.

I am surprised that travellers, in speaking of the plain of Troy, almost always fail to mention the Aeneid. Yet Troy has been Virgil’s glory as much as Homer’s. It is a rare destiny for a country to have inspired the fnest verse of two of the world’s greatest poets. As I watched the shores of Troy recede, I sought to recall the verses that so beautifully depict the Greek fleet, emerging from Tenedos, and advancing, per silentia lunae:through the silent moonlight (adapted from Virgil: Aeneid: II: 255), towards those solitary shores passing one after another before my eyes. Once awful cries succeeded to the silence of the night, and flames from Priam’s palace illuminated the sea, where our ship sailed peacefully.

The Muse of Euripides, also capturing that pain, prolonged the scenes of mourning on those tragic shores.

The Chorus Hecuba, see you Andromache there, riding a foreign chariot? Her son, the son of Hector, the young Astyanax, hangs at her breast.

Hecuba O ill-fated woman! Where are they leading you, amidst Hector’s weapons and the spoils of Phrygia? ...

Andromache O grief!

Hecuba My children!

Andromache Ill-fated one!

Hecuba And my children!...

Andromache Hurry, my husband!...

Hecuba Yes, come, scourge of the Greeks! O, first of my children! Grant to Priam in death that to which on earth he was so tenderly united.

The Chorus We have only regrets and tears to shed upon these ruins. Grief yields to grief... Troy suffers the yoke of slavery.

Hecuba So the palace where I gave birth has fallen!

The Chorus O my children! Your land is become a wilderness…

(a free adaptation from Euripides: The Trojan Women)

While I was occupied with Hecuba’s grief, the descendants of the Greeks aboard our vessel looked as though they were still rejoicing at Priam’s death. Two sailors danced on deck, to the sound of tambourine and zither: they performed a kind of pantomime. Sometimes they raised their arms to heaven; sometimes they set one of their hands to their side, extending the other like an orator haranguing a crowd. They then raised that same hand to their breast, forehead, and eyes. All this was interspersed with poses, more or less odd, of a vague character, and quite akin to the contortions of savages. One may read on the subject of Modern Greek dance, the letters of Monsieur Guys and Madame Chénier (See Pierre Augustin Guys: Voyage Littéraire de la Grèce, and Elizabeth Santi-Lomaca Chénier: Lettres Grecques). To the pantomime, succeeded a round-dance, where the line, passing and re-passing various points, recalled the subjects of those bas-reliefs depicting the dances of ancient times. Happily, the shadow of the ship’s sails hid the figures and clothing of the actors to some extent, and I could transform my unkempt sailors into shepherds of Sicily or Arcady.

The wind continuing to blow favourably for us, we swiftly crossed the channel that separates the island of Tenedos from the mainland, and skirted the coast of Anatolia as far as Cape Baba (Bababurnu), formerly Lectum Promontorium. We then sailed west to double, at nightfall, the tip of the island of Lesbos. It was on Lesbos that Sappho and Alcaeus were born, and to which the head of Orpheus floated, repeating Eurydice’s name:

Ah! miseram Eurydicen, anima fugientes, vocabat.

He with ebbing breath, cried out: ‘Ah, poor Eurydice!’

(Virgil:Georgics IV:525-526)

On the morning of the 22nd of September, the north wind rose with extraordinary violence. We had to anchor at Chios, to take on board more pilgrims; but through the captain’s fear and poor seamanship, we were obliged to go and anchor in the harbour of Tchesme (Cesme) on a dangerously rock-strewn bottom, not far from the wreckage of a large Egyptian vessel.

There is something fateful about this port of Asia Minor. The Turkish fleet was burned there in 1770, by Count Orlov (Aleksey Grigoryevich); and the Romans destroyed the galleys of Antiochus there, in 191BC, assuming the Cyssus of the ancients is the modern Tchesme. Monsieur de Choiseul has produced a plan, and depicted a view, of the harbour. The reader may recall that I almost entered Tchesme when bound for Smyrna, on the 1st of September, twenty-one days before my second passage through the archipelago.

Throughout the 22nd and 23rd, we waited for pilgrims from the island of Chios. Jean went ashore, and provided me with an ample supply of Tchesme pomegranates: they have a great reputation in the Levant, although they are inferior to those of Jaffa. But I have mentioned Jean, and that reminds me that I have not yet spoken to the reader of this new interpreter, successor to the excellent Joseph. He was the most mysterious man I ever met: two little eyes sunken in his head and as if hidden by a very prominent nose, two reddish moustaches, a habit of constantly smiling, and something flexible in his bearing, will give an initial idea of the person. When he had something to tell me, he began by advancing alongside, and, after a long detour, almost crept up on me, to whisper in my ear the least secret thing in the world. As soon as I saw him, I would cry: ‘Walk straight and speak loudly’; advice worth giving to many people. Jean had an understanding with the head priests: he told strange things about me; he brought me compliments from pilgrims who remained below decks, and whom I had failed to notice. At mealtimes, he had no appetite, as he was above such vulgar necessities, but as soon as Julien had finished eating, poor Jean went down into the shallop where they kept my provisions, and under the pretext of putting the baskets in order, swallowed pieces of ham, devoured a bird, drank a bottle of wine, all with such rapidity that one could see no movement of his lips. He then returned with a sad visage to ask if I had need of his services. I advised him not to indulge in grief, and to take some food, otherwise he ran the risk of falling ill. The Greek thought I was his dupe, and it gave him so much pleasure I allowed him to believe so. Despite his small faults, Jean was basically a very honest man and deserved the trust his masters placed in him. All in all, I have drawn this portrait, and a few others, to satisfy the tastes of those readers who like to know something of the characters whose lives they are asked to follow. For my own part, if I have shown some talent for this kind of caricature, I work hard to stifle it; everything that makes a mockery of the nature of man seems unworthy of esteem: obviously I exclude from that judgement, a good joke, subtle raillery, the grand irony employed by the oratorical style, or high comedy.

On the night of the 22nd of September, the vessel slipped its anchor, and we thought we would foul the wreckage of the vessel from Alexandria, marooned nearby. The pilgrims from Chios arrived on the 23rd at noon: they were sixteen in number. At ten in the evening we sailed, the night being fine, with a moderate easterly wind, which changed to a northerly at dawn on the 24th.

We passed between Nicaria and Samos. The latter island was famous for its fertility, its tyrants, and above all the birth of Pythagoras. That fine episode in Télémaque (Fénelon, Les Aventures de Télémaque: XIV) has surpassed all that the poets have said regarding Samos. We entered the channel formed by the Sporades, Patmos, Leria, Cos, etc. and the shores of Asia Minor. There the Meander pursued its winding course, there stood Ephesus, Miletus, Halicarnassus, Cnidus: I saluted, for the last time, the homeland of Homer, Herodotus, Hippocrates, Thales, and Aspasia, though I failed to see the temple at Ephesus, the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, or the Venus of Cnidus, and without the work of Pococke, Wood, Spon, and de Choiseul, I would not, under its modern inglorious name (Samsun Dagi) have recognized the promontory of Mycale.

On the 25th of September, at six in the morning, we dropped anchor at the port of Rhodes, to take on a pilot for the Syrian coast. I went ashore, and was conducted to the residence of Monsieur Magallon (Charles Magallon), the French Consul: ever the same reception; the same hospitality, the same politeness. Monsieur Magallon was ill; he chose, however, to introduce me to the Turkish commandant, a fine man, who gave me a black goat, and allowed me to wander wherever I wished. I showed him a firman which he placed on his head, declaring that this is how he supported all the friends of the Grand Seigneur.

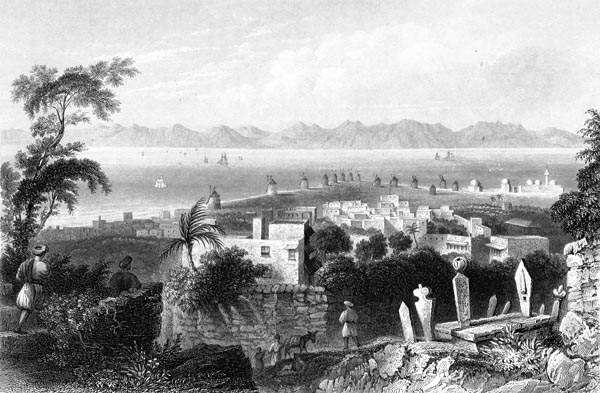

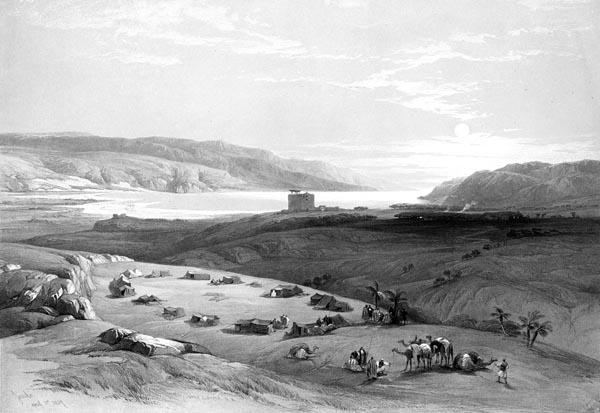

‘Rhodes, the Ancient Dodanim, with the Channel Between the Island and Asia Minor’

Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor - John Carne, Thomas Allom, William Henry Bartlett, William C. Stafford (p507, 1861)

The British Library

I longed to forsake this audience, to at least take a glance at this famous Rhodes, where I would spend only a moment.

Here, for me, commenced that antiquity which formed a transition between Greek antiquity which I was leaving, and Hebrew antiquity whose remains I went to seek. The monuments of the Knights of Rhodes revived my curiosity, somewhat wearied by the ruins of Sparta and Athens. Wise laws regarding trade (one may consult Johanne Leunclavius’s Traité du droit maritime des Grecs et des Romains. That splendid decree of Louis XIV regarding the Navy retains several provisions of the Rhodian laws); a few verses of Pindar (Olympian Ode VII) on the Sun’s marriage with Venus’s daughter (the nymph, Rhodos); comic poets; painters; monuments more grand than beautiful; that, I think, is all that reminds the traveller of ancient Rhodes. The Rhodians were brave: it is somewhat singular that they were rendered famous in warfare for enduring a siege gloriously (305BC), like the knights who were their successors (1522AD). Rhodes, honoured by the presence of Cicero and Pompey, was sullied by the residence of Tiberius (6BC). The Persians seized Rhodes (Chosroes II, in 620AD) in the reign of Pope Honorius I. It was then taken by the generals of the caliphate, in 647AD, and re-taken by Anastasius II, Emperor of the East (715AD). The Venetians settled here in 1203, John II Doukas Vatatzes took it from the Venetians (1232AD). The Turks conquered the Greeks. The Knights of St. John of Jerusalem seized it in 1309. They held it for almost two centuries, and yielded it to Suleiman I (The Magnificent), on the 25th of December, 1522. Regarding Rhodes, one can consult Vincenzo Coronelli, Dapper, Savary, and Monsieur de Choiseul.

At every step Rhodes offered me evidence of our way of life and memories of my homeland. I found a tiny France in the middle of Greece:

Procedo and parvam Trojam simulataque magnis

Pergamon...agnosco…

I walked on, and saw a little Troy, and a copy of the great citadel…

(Virgil:Aeneid III:349-351)

I traversed a long road, still called the Street of the Knights. It is lined with Gothic buildings; the walls of these houses are lined with Gallic emblems and the arms of our ancient families. I noted the royal lilies of France, as fresh as if they had just left the sculptor’s hand. The Turks, who have everywhere mutilated the monuments of Greece, have spared those of chivalry: Christian honour astonished the brave infidel, and Saladin has shown De Coucy respect.

‘Ruins of Medieval Buildings at the Beginning of the Knight's Street in Rhodes’

Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor - John Carne, Thomas Allom, William Henry Bartlett, William C. Stafford (p381, 1861)

The British Library

At the end of the Street of the Knights, three Gothic arches lead to the palace of the Grand Master. The palace now serves as a prison. A half-ruined monastery, served by two monks, is all that reminds Rhodes of the religion that performed so many miracles there. The priests conducted me to their chapel. A Gothic Virgin, painted on wood, is displayed holding the child in her arms: the arms of the Grand Master D’Aubusson are engraved at the foot of the painting. This curious antiquity was discovered some years ago, by a slave who was attending to the monastery garden. There is a second altar in the chapel dedicated to Saint Louis, whose image is found throughout the East, and whose death-bed I saw at Carthage. I left some alms beside the altar, begging the priests to say a Mass for my safe journeying, as if I had already foreseen the dangers I would run on the coast of Rhodes on my return from Egypt.

The commercial port of Rhodes would be secure enough if the old defensive works were restored. Walls with twin towers flank the harbour. These two towers, according to local tradition, replaced the two rocks that served as the base for the Colossus. It is known that ships did not pass between the legs of this Colossus, and I only mention this so as not to neglect anything.

Quite close to the main harbour is the dock for the galleys and their construction site. They were currently building a thirty gun frigate from pine-trees felled on the island’s mountains, which seemed to me worth noting.

‘Rhodes, from the Heights Near Sir Sidney Smith's Villa’

Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor - John Carne, Thomas Allom, William Henry Bartlett, William C. Stafford (p136, 1861)

The British Library

The shores of Rhodes, towards Caramania (Doris and Caria), are roughly at sea level, but the island rises in the interior, and a high mountain is clearly prominent, flattened at its peak, mentioned by all the geographers of antiquity. At Linda there are remains of the Temple of Athene. Camira and Ialyssos have disappeared. Rhodes once supplied oil to the whole of Anatolia, and now does not produce enough for its own consumption. It still exports some wheat. The vines yield a very good wine, which resembles those of the Rhone: the vine-stocks may have been brought from the Dauphiné by the knights of that region, especially since they call the wines, as in Cyprus, vins du Commanderie.

Our geographers tell us that in Rhodes they weave velvets and tapestries which are much esteemed: various coarse fabrics, which they use to cover equally coarse furniture, are the only products of Rhodian industry, of that kind. These people, whose colonists long ago founded Naples and Agrigento, today barely occupy a corner of their desert island. An Agha with a hundred degenerate Janissaries is sufficient to control a herd of slaves. It is inconceivable that the Order of Malta has never tried to return to its ancient domain; nothing would have been easier than to seize the island of Rhodes: it would have been a trivial task for the Knights to renew the fortifications, which are still quite sound: they would not have been expelled again, since the Turks, who were the first to employ trench warfare against the towns of Europe, are now the last people in the art of sieges.

I left Monsieur Magallon on the 25th of September at four in the evening, after having left letters with him, which he promised to dispatch to Constantinople, via Carmania. Taking a caique, I re-joined our vessel, which was already under sail with its coastal pilot on board: the pilot was a German who had lived at Rhodes for many years. We set our course for the cape at the tip of Carmania, once the promontory of the Chimaera in Lycia. Rhodes offered in the distance behind us, a length of bluish coastline, under a golden sky. Within that extent two squared-off mountains could be distinguished, which seemed as if carved to be foundations for castles, and resembled in their form the Acropolis of Corinth, or those of Athens and Pergamon.

The 26th was an unfortunate day. We were becalmed alongside the mainland of Asia Minor, nearly opposite Cape Chelidonia, which forms the tip of the Gulf of Satalia (Antalya). I saw on our left the elevated peaks of Mount Cragus (Babadag), and I remembered the verses of poets regarding chilly Lycia. I was unaware that one day I would curse the summits of that Taurus range, which I was pleased to gaze at, and would count them among the famous mountains whose tops I have seen. The currents were very strong, and carried us off, as we realised the next day. The vessel which was in ballast, rolled wearily: the head of the mainmast snapped, and the yard of the second sail of the foremast. For such inexperienced sailors it was a great misfortune.

It is truly an amazing thing to watch the Greeks navigating. The pilot sits, legs crossed; his pipe in his mouth; he grasps the tiller, which, in order to act at the same level as the hand that guides it, scrapes the stern planking. Before the pilot, who is half-reclining, and therefore possesses little leverage, is a compass, of which he knows nothing, and which he fails to consult. At the slightest appearance of danger, French and Italian charts are deployed on the bridge; the whole crew lie flat, the captain at their head; they examine the chart, tracing its lines with their fingers, trying to establish where they are; everyone gives his opinion: they end up by understanding nothing at all of this arcane parchment of the Franks; they re-fold the map; they bring the sails about, or sail downwind: then pipes and rosaries are taken up once more; we recommend our lives to Providence, and await events. There are vessels that veer two or three hundred miles off course, and land in Africa instead of arriving in Syria; but that does not stop the crew dancing at the first ray of sunlight. The ancient Greeks were, in many respects, mo more than delightful credulous children, who passed from sadness to joy with extreme fluidity; the modern Greeks have retained aspects of that character: happy at least in having recourse to levity to combat their misery!

The northerly wind resumed blowing at about eight in the evening, and hopes of swiftly reaching the end of our voyage revived the pilgrims’ spirits. Our German pilot told us that we should see Cape St. Epiphanius, and the island of Cyprus, at daybreak. We thought only of celebrating being alive. All our provisions were carried on deck; we divided into groups; each passed to his neighbour something his neighbour lacked. I adopted the family who had the berth opposite me, next to the captain’s cabin; it consisted of a wife, two children and an old man, the father of the young pilgrim. This old man was performing his third voyage to Jerusalem, he had never seen a Latin pilgrim, and the good man wept for joy, as he gazed at me: So I supped with the family. I have scarcely witnessed a scene more delightful and picturesque. The wind was fresh; the sea; splendid; the night, serene. The moon seemed to sway amidst the masts and rigging of the ship; sometimes it appeared beyond the sails, and the whole ship was illuminated; sometimes it was hidden by the canvas, and the groups of pilgrims were again plunged into darkness. Who could not bless religion, whilst reflecting that these two hundred pilgrims, so happy at this moment, were nevertheless slaves bowed under an odious yoke? They were travelling to the tomb of Jesus Christ to forget the lost glories of their homeland, and find solace from their present evils. What secret sorrows were they not about to set down beside the Saviour’s manger! Each wave that drove the ship towards the holy shore bore one of our troubles.

On the 27th of September, in the morning, much to the surprise of the pilot, we were at sea, and out of sight of land. We were becalmed: there was general consternation. Where were we? Were we north of, or still west of the island of Cyprus? We spent all day in this one debate. Talking of taking bearings, or soundings, would have been like speaking Hebrew to our mariners. When the breeze got up towards evening, there was a further difficulty. What course should we take? The pilot, who believed himself beyond the Gulf of Satalia (Antalya), and off the northern coast of the island of Cyprus, wanted to head south to reach the latter, though it would yield the consequence that if we were still west of the island, we would sail, on that compass bearing, straight towards Egypt. The captain claimed we must wear northwards, to reach the coast of Carmania: that would mean retracing our course, and indeed, in that respect the wind was contrary. I was asked my opinion, because, in difficult situations, the Greeks and Turks always have recourse to the Franks. I advised them to sail east, for an obvious reason: we were west or north of the island of Cyprus: now, in either case, by heading east we would be on a beneficial course. Moreover, if we were west of the island, we could not fail to see land to port or starboard, in a very short time, either Carmania’s Cape Anamur, or Cyprus’s Cape Kormakittis (Korucam Burnu). We would be free to double the eastern tip of the island, and descend along the coast of Syria.

This advice appeared best, and we turned the bows east. On the 28th of September, at five in the morning, to our great joy, we sighted Cape Gata, on the island of Cyprus; it lay north of us, about twenty-five to thirty miles away. Thus, we were south of the island, and on the right course for Jaffa. The current had previously carried us well to the south-west.

At noon, the wind dropped. The calm continued the rest of the day, and lasted until the 29th. We received three new passengers on board, two wagtails and a swallow. I have no idea what could have led the former to leave their haunts; as to the latter, they were on their way to Syria perhaps, and may have come from France. I was tempted to ask them for news of the paternal roof I had left so long ago (See Les Martyrs, XI). I remember, in my childhood, spending hours of indescribably melancholic pleasure, watching the swallows’ flight in autumn; a secret instinct told me that I would, like those birds, become a voyager. They gathered at the end of September, above the reeds of a large pond: there, emitting their cries and executing a thousand evolutions above the water, they seemed to be trying out their wings, and preparing for lengthy pilgrimages. Why, of all the memories of existence, do we prefer those that recall our birthplace? The pleasures of self-love, the illusions of youth, fail to charm our memory: on the contrary, we find in them aridity or bitterness; but the most trivial of circumstances awake in the depths of the heart the emotions of childhood, and always with a new attraction. By the shores of the American lakes, in an unknown wilderness that has little to say to the traveller, in a land that possesses nothing but the grandeur of its solitude, a swallow sufficed for me to retrace scenes from my life’s earliest days, as it now recalled them to me on Syrian waters, in sight of an ancient land, echoing to the voice of the centuries and historical tradition.

The currents thus brought us to the Island of Cyprus. We reached its sandy, low-lying, and seemingly arid shores. Mythology has set its most happy fables there (see Les Martyrs:XVII.)

Ipsa Paphum sublimis abit, sedesque revisit

Laeta suas, ubi templum illi, centumque Sabaeo

Thure calent arae, sertisque recentibus halant.

She herself soars high in the air, to Paphos, and returns to her home

with delight, where her temple and its hundred altars

steam with Sabean incense, fragrant with fresh garlands.

(Virgil: Aeneid I:415)

It is better, as regards the island of Cyprus, to keep to poetry rather than history, unless one takes pleasure in recalling one of the most glaring injustices of the Romans and that shameful expedition led by Cato the Younger (58BC, see Plutarch: Cato the Younger: 36). Yet it is a strange thing to imagine the temples of Amathus and Idalia converted to prisons in the Middle Ages. A French gentleman was king of Paphos (Guy de Lusignan, ruled 1192-1194), and barons dressed in doublets were ensconced in the sanctuaries of Eros and the Graces. One may read the whole history of Cyprus in Olfert Dapper’s Archipel: while the Abbé Mariti (Giovanni Mariti: Viaggi per l’isola di Cipro e per la Soria e Palestina, 1792) has described the revolutions of modern times, and the current status of the island, still important today because of its situation.

The weather was so beautiful, and the air so mild, that all the passengers remained on deck at night. I had disputed possession of a corner of the quarter-deck with two large Greek Orthodox monks who had grudgingly yielded it to me. It was there that I was sleeping on the 30th of September, when I was awakened, at six in the morning, by the sound of loud voices: I opened my eyes, and saw the pilgrims who had been keeping watch at the prow. I asked what the matter was; they cried: Signor, il Carmelo! Carmel! The wind had risen before eight the previous evening, and during the night we had arrived in sight of the coast of Syria. As I had been sleeping fully dressed, I was quick to rise to my feet, while asking about the sacred mountain. Everyone was eager to point it out to me, but I could see nothing, as the sun was rising ahead of us. The moment had something religious and august about it; all the pilgrims, rosary in hand, remained quietly in the same attitude, awaiting the appearance of the Holy Land; the head priest prayed aloud: we listened to the prayer and the sound of the ship’s passage, as a favourable wind drove the vessel swiftly over a shining sea. From time to time a cry rose from the bow as Carmel again became visible. Finally I caught sight of that mountain myself, like a round stain under the sun’s rays. I fell to my knees in the manner of Latins. I felt a different kind of emotion to that which I had felt on first seeing the shores of Greece; but the sight of that cradle of the Israelites, and homeland of Christians, filled me with awe and respect. I was about to reach a land of wonders, the source of the most astonishing poetry, places where, even speaking of mankind alone, the greatest of events occurred, that changed the world forever, I mean the coming of the Messiah; I was about to land on those shores visited by Godfrey of Bouillon, Raymond de Saint Gilles, Tancred the Brave, Hugh the Great, Richard the Lion Heart, and that Saint Louis whose virtues were admired by the infidels. An obscure pilgrim, how did I dare to tread a soil consecrated by so many illustrious ones?

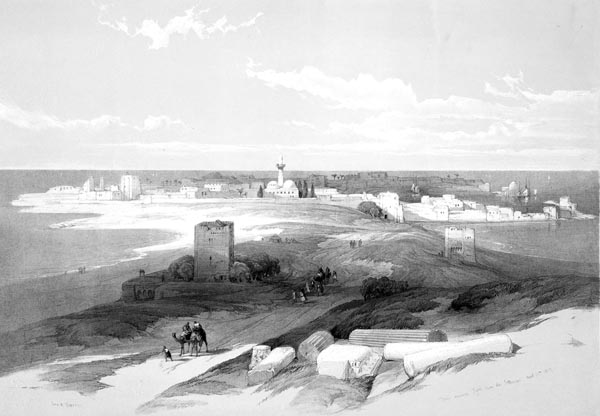

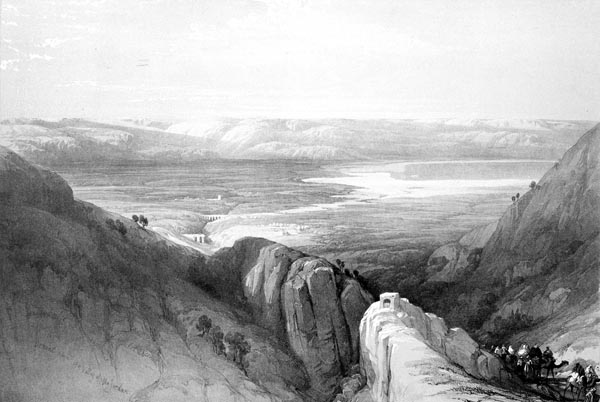

‘Tyre, from the Isthmus’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

As we advanced, and the sun rose in the sky, the land unrolled before us. The furthest point we could see in the distance, to our left, towards the north, was the tip of Tyre; followed by Cape Blanc (Rosh Hanikra), Saint Jean d’Acre (Akko), Mount Carmel with Haifa at its foot; Tantura, the ancient Dor; Château-Pèlerin (Atlit, Castle Pilgrim), and Caesarea, whose ruins were visible. Jaffa ought to have been beneath the very prow of the vessel, but we could not see it yet, then the coast dropped gradually to a last headland in the south, where it seemed to vanish: there the shores of ancient Palestine commence, which join with those of Egypt, and are almost at sea level. The land, which was twenty-five to thirty miles away, seemed generally white, with dark undulations produced by shadows; there were no salient features on that oblique line traced from north to south: not even Mount Carmel projected from the background: everything was uniform and mottled. The overall effect was almost that of the mountains of the Bourbonnais (Allier/Cher), when viewed from the heights of Tarare. A line of white jagged clouds on the horizon followed the line of the land, and seemed to repeat its appearance in the sky.

‘Mount Carmel Looking Towards the Sea’

Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor - John Carne, Thomas Allom, William Henry Bartlett, William C. Stafford (p400, 1861)

The British Library

‘St. Jean d'Acre, from the Sea’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

The wind failed us at noon; it rose again at four, but through the pilot’s ignorance, we overshot our destination. We were heading full sail towards Gaza, when the pilgrims realised, by an inspection of the coastline, our German’s error; we had to tack; all this caused lost time, and night fell. However, we were still approaching Jaffa; we could even see the lights of the city, when the wind from the northwest beginning to blow with fresh force, fear seized the captain; he dared not seek the roads at night: suddenly he swept the bows round, and returned to the high seas.

I was leaning over the stern, and watched the land disappear with a real feeling of grief. After half an hour, I saw what looked like the distant reflection of a fire on the summit of a mountain range: the mountains were those of Judea. The moon, which produced the effect with which I had been struck, soon revealed its broad reddened disc over Jerusalem. A beneficial hand seemed to have raised this beacon on the heights of Sion to guide us to the holy city. Unfortunately we did not, like the Magi, follow the helpful star, and its light only served to help us flee the harbour we so longed for.

On the next day, Wednesday, the first of October, at daybreak, we found ourselves floundering offshore, almost opposite Caesarea: we needed to return south along the coast. Fortunately the wind was favourable, though light. In the distance rose the amphitheatre of the mountains of Judea. At the foot of these mountains, a plain sloped to the sea. It showed barely a trace of cultivation, and its only structure was a Gothic castle in ruins, surmounted by a crumbling and abandoned minaret. On the shore, the land ended in yellow cliffs, speckled with black, which overlooked a beach where we saw and heard the waves breaking. Arabs, wandering the coast, followed, with a covetous eye, our ship passing by on the horizon, anticipating the spoils of shipwreck on the same coast where Jesus Christ commanded us to feed the hungry and clothe the naked.

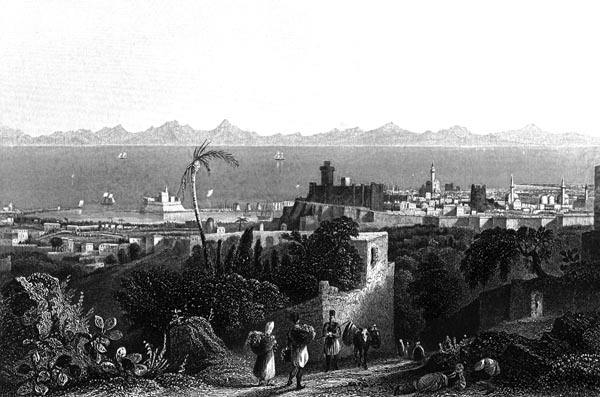

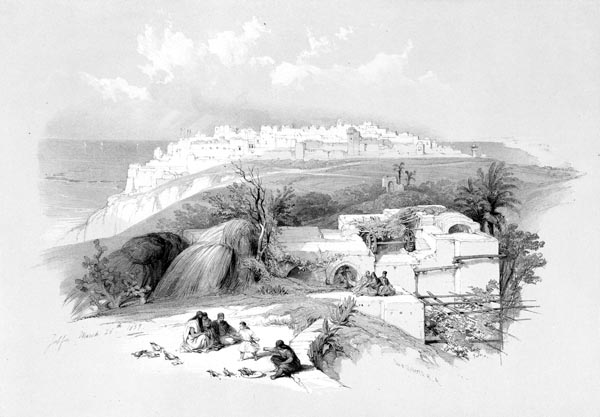

‘Jaffa’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

At two in the afternoon, we saw Jaffa at last. We had been observed from the city. A boat detached itself from the harbour, and advanced to meet us. I took advantage of this boat to send Jean ashore. I handed him the letter of recommendation that the Custodians of the Holy Land had given me in Constantinople, which was addressed to the priests at Jaffa. I wrote, at the same time, a word to them.

An hour after Jean’s departure, we came to anchor before Jaffa, the city lying to the south-east, and the minaret of the mosque to the east-southeast. I note the compass directions here for an important reason: the vessels of the Latins usually anchor farther offshore; they are then moored above a layer of rocks that may well sever the cables, while the Greek ships, on approaching land, find a less hazardous anchorage, between the basin of Jaffa and the line of rocks.

‘Jaffa Looking South’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

Jaffa presents itself as no more than a wretched cluster of houses gathered together, and arranged in an amphitheatre, on the slope of a tall hill. The misfortunes that this city has so often experienced have multiplied its ruins. A wall that at its two ends reaches the sea, envelopes it on the landward side, and protects it from attack.

Various caiques soon arrived, from all sides, to transport us pilgrims to shore: the clothing, features, complexion, facial appearance, and language of the owners of these caiques, immediately proclaimed the Arab race, and the proximity of the desert. The disembarkation of the passengers was achieved without fuss, though with a justifiable eagerness. This crowd of men, old men, women, and children on setting foot in the Holy Land uttered no such cries, tears, and lamentations as painters are pleased to depict in creating their imaginary and ridiculous works. They were quite calm; and of all those pilgrims I was certainly not the least moved.

I finally saw a boat coming towards us, in which I made out my Greek servant, accompanied by three monks. They recognized me in my French clothing, and waved their hands, in a kindly manner. They were soon on board. Although these monks were Spanish, and spoke an Italian which was hard to understand, we shook hands like true compatriots. I descended with them into the shallop; we entered the port through a convenient opening in the rocks, dangerous even for a caique. The shore Arabs walked through water up to their waists, in order to carry us on their shoulders. Rather an amusing scene took place: my servant was wearing a white greatcoat; white being the colour of distinction among the Arabs, they decided that my servant was the sheikh. They seized him, and carried him off in triumph despite his protestations while, dressed in my blue coat, I was borne away in obscurity, on the back of a ragged beggar.

We went off to the monks’ hospice, a simple wooden house built beside the harbour and enjoying a fine view of the sea. My hosts initially conducted me to the chapel, which I found well-lit, and where they thanked God for having sent them a brother; they are most touching, these Christian institutions through which the traveller finds friends and succour in the most barbarous of countries; institutions I have mentioned elsewhere, and which are never sufficiently admired.

The three monks who came to find me on board were named John Truylos Penna, Alexandre Roma and Martin Alexano; they comprised the entire hospice, their priest, Dom Juan de la Concepcíon, being absent.

On leaving the chapel, the monks installed me in my cell, where there was a table, bed, ink, paper, water and fresh white linen. One needs to have disembarked from a Greek vessel loaded with two hundred pilgrims, to appreciate the value of all this. At eight in the evening, we went to the refectory. We found two other priests who had come from Rama (Ramla) and were leaving for Constantinople; Father Manuel Sancha and Father Francis Munoz. We sang the Benedicite together, preceded by the De Profundis; a remembrance of how Christianity mingles death with all the events of life to render them more serious, as the ancients mingled it with their banquets to render their pleasures more piquant. I was served poultry, fish, and excellent fruit; pomegranates, watermelons, grapes, and mature dates; at a small, clean and separate table; I drank a discreet amount of Cypriot wine and Levantine coffee. While I filled myself with this excellent fare, the monks ate some fish without salt or oil. They were lively but modest; familiar but polite; no pointless questions, no idle curiosity. All was directed to my trip, on the measures needed for me to complete it in safety, ‘For,’ they told me, ‘we now owe a responsibility to your country with regard to yourself.’ They had already dispatched a message to the sheik of the Arabs of Mount Judea, and another to the pastor of Ramla. ‘We welcome you’, Father Francis Munoz told me, ‘with a heart limpido e bianco.’ It was unnecessary for this Spanish monk to assure me of the sincerity of his feelings; I would have guessed them readily, from the pious frankness of his brow and his gaze.

This reception, so Christian and so charitable, in the land where Christianity and charity had their birth; this apostolic hospitality, in a place where the first apostles preached the Gospel, touched me to the core: I remembered how other missionaries had received me with the same cordiality in the wilds of America. The monks of the Holy Land possess yet more merit, in demonstrating to pilgrims travelling to Jerusalem the charity of Jesus Christ, they have guarded on their behalf the Cross that was planted on those shores. That monk, with his heart limpido e bianco, assured me that he still found the life he had led for fifty years un vero paradiso. Would you like to know what that paradise is like? Daily affronts, the threat of beatings, shackles, death! This monk, on the previous Easter, having washed the altar cloths, water, impregnated with starch, flowed out of the hospice and whitened a stone. A passing Turk, seeing the stone, reported to the cadi that the monks were repairing the building. The cadi, arriving at to the scene, decided that the stone which was black, had become white; and without hearing the monks’ testimony forced them to pay ten bags of coin in reparation. On the very eve of my arrival at Jaffa, the pastor of the hospice had been threatened with the rope by a servant of the Agha, in the presence of the Agha himself. The latter was content to stroke his moustache tranquilly, without deigning to speak a word in favour of the dog. Such is the veritable paradise experienced by the monks who, according to some travellers, are petty sovereigns in the Holy Land, and enjoy the highest honours.

At ten in the evening, my hosts led me down a long corridor to my cell. The waves broke with a crash against the rocks of the harbour: with the window closed, it sounded like a tempest, with the window open, a beautiful sky was visible, a tranquil moon, a calm sea, and the pilgrim ship anchored offshore. The monks smiled at the surprise I experienced at this contrast. I said, in poor Latin: Ecce monachis similitudo mundi; quantumcumque mare fremitum reddat, eis placidae semper undae videntur: omnia tranquillitas serenis animis. Behold, how like this is to the monks of this world; no matter how the sea roars, to them the waves seem always calm: all is tranquil to the tranquil mind.

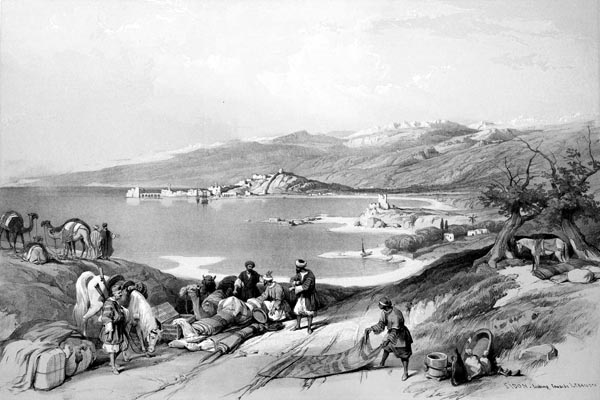

‘Sidon, Looking Towards Lebanon’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

I spent part of the night contemplating the Tyrian Sea that Scripture calls the Great Sea, which bore the fleet of the prophet-king on his way to the cedars of Lebanon and the purple of Sidon; that sea where Leviathan makes the deep to boil (Job:41:31); that sea that the Lord shuts up with doors (Job:38:8); that sea that saw God and fled (Psalms 114:3). Here was neither the savage Ocean of Canada, nor the smiling waves of Greece. To the south lay Egypt, where the Lord had entered on a swift cloud, to dry up the channels of the Nile, and overthrow idols (Isaiah: 19:1-30); north rose the queen of cities, whose merchants were princes (Isaiah 23:8): Ululate, naves maris, quia devastata est fortitudo vestra...Attrita est civitas vanitatis, clausa est omnis domus nullo introeunte...quia haec erunt in medio terrae...quomodo si paucae olivae, quae remanserunt, excutiantur ex olea; et racemi, cum fuerit finita vindemia (Vulgate: Isaiah 23:14 and 24:10,13): ‘Howl, vessels of the sea, because your power is destroyed ...The city of vanity is razed, all its houses are closed and none may enter ... What remains of men in these places shall be left as the handful of olives on the tree after harvest, as grapes hanging from the vine when the harvest is done.’ Here other antiquities are revealed by another poet: Isaiah succeeds to Homer.

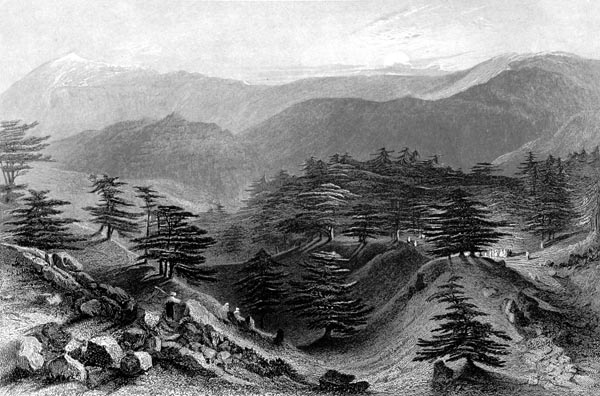

‘Cedars of Lebanon’

Syria, the Holy Land, Asia Minor - John Carne, Thomas Allom, William Henry Bartlett, William C. Stafford (p33, 1861)

The British Library

And that is not all, for the sea I gazed at bathed, to my right, the land of Galilee and, on my left, the plain of Ascalon: the former recalled the early traditions of the life of the patriarchs and the Nativity of the Saviour; the latter, memories of the Crusades and the shades of the heroes of the Gerusalemme:

Grande e mirabil cosa era il vedere,

quando quel campo e questo a fronte venne:

come, spiegate in ordine le schiere,

di mover già, già d’assalire accenne:

sparse al vento ondeggiando ir le bandiere,

e ventolar su i gran cimier le penne:

abiti e fregi, imprese, arme e colori

d’oro e di ferro al sol lampi e fulgori.

It was a great, and a wondrous sight,

When, face to face, those armies met:

How in every troop rode every knight

Prepared to fight, catch glory in his net:

Free in the wind waved, those banners bright,

On their helms the quivering plumes were set;

Brave arms and emblems, smiling, in the sun,

Colours of gold and steel, glittering shone.

(Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata XX:28)

‘Askelon’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

Jean-Baptiste Rousseau has depicted for us the success of that day:

La Palestine, enfin, après tant de ravages,

Vit fuir ses ennemis, comme on voit les nuages

Dans le vague des airs fuir devant l’aquilon;

Et des vents du midi la dévorante haleine

N’a consumé qu’ à peine

Leurs ossements blanchis dans les champs d’Ascalon.

Palestine, at last, after such great devastation,

Saw its foes flee, as clouds are seen to run,

Through wastes of air, the northerly drives on;

While the south wind’s hot devouring breath

Has scarce consumed as yet

Their bones that bleach on the fields of Ascalon.

(J-B Rousseau: Odes III:5, Aux Princes Chrétiens)

It was with regret that I tore myself from the spectacle of that sea which awakens so many memories, but it was necessary to snatch some sleep.

Father Juan de la Concepcíon, the curé of Jaffa and head of the hospice, arrived the next morning, the 2nd of October. I wanted to explore the city, and visit the Agha, who sent me his compliments; the curé deterred me from executing this plan:

‘You do not know these people,’ he said, ‘what you take for politeness is merely malicious curiosity. They only welcome you to find out who you are, whether you are wealthy, whether you can be despoiled. Do you wish to see the Agha? You must first give him presents: he will not fail to give you an escort to Jerusalem, regardless of your wishes; the Agha of Ramla will add to this escort; the Arabs, seeing that a wealthy Frenchman is going on pilgrimage to the Holy Sepulchre, will raise the amount of the caffaro levy, or attack you. At the gate of Jerusalem you will find the camp of the Pasha of Damascus, who has come to levy contributions, before leading the caravan to Mecca: your trappings will give umbrage to the Pasha, and expose you to insult. Arriving in Jerusalem, you will be asked for three or four thousand piastres to pay for the escort. The people, informed of your arrival, will lay siege to you, such that if you possessed millions, you could not satisfy their greed. The streets will be blocked to obstruct your passage, and you would not enter the holy places without running the risk of being set upon. Trust me, tomorrow we will disguise ourselves as pilgrims and we will travel to Ramla together; there I will receive a response to my message; if it is favourable, you can leave at night, and you will reach Jerusalem safely, and cheaply.’

The priest supported his reasoning with a thousand examples especially that of a Polish bishop, whose air of excessive wealth had cut short his life, two years previously. I mention this only to show to what degree corruption; greed for gold; anarchy and barbarism have been taken in that country.

So I yielded to the experience of my hosts, and confined myself to the hospice, where I spent a pleasant day in peaceful conversation. I received a visit from Monsieur Contessini, who aspired to the vice-consulate of Jaffa, and the Damiens, father and son, of French origin, formerly living under Djezzar (Cezzar Ahmet Pasha), at Saint-Jean d’Acre. They told me singular tales of recent events in Syria; they spoke of the reputation that the Emperor Napoleon and our armies had won in the desert. Men are more sensitive to the reputation of their country when far from it, than they are at home, and we have seen the French emigrés claim their part in victories that appeared to condemn them to eternal exile (James II, who lost a kingdom, expressed the same sentiment at the battle of La Hogue, in 1692).

I spent five days in Jaffa, on my return from Jerusalem, and I examined it in minute detail; I ought therefore to speak of it at that time; but in order to follow the sequence of my travels, I will set down my observations here; moreover, after a description of the holy places, it is likely that readers would find Jaffa less interesting.

Jaffa was formerly called Joppa, which signifies beautiful or comely, pulchritudo aut decor, as Adrichomius (Christianus Crucius Adrichomius: Theatrum Terrae Sanctae et Biblicarum Historiarum, 1590) said. D’Anville derives the current name from a primitive form, Japho (I know it is pronounced Yafa in Syria, and Monsieur de Volney writes it thus, but I know no Arabic: I have no other authority for altering D’Anville’s orthography which is that of so many other learned writers.) I note that, in the land of the Hebrews, there was another city named Jaffa, which was taken by the Romans; this name may then have been transferred to Joppa. If we are to believe the translators, and even Pliny (V:XIV.69), the origin of this city dates back to antiquity, since Joppa was built before the flood. They say it was at Joppa that Noah entered the ark. After the retreat of the waters, the patriarch gave Shem, his eldest son, as his share, all the dependent territories of the city founded by his third son Japheth. Finally Joppa, according to the traditions of the country, guarded the tomb of the second father of the human race.

According to Pococke, Shaw and perhaps D’Anville, Joppa fell to Ephraim’s share, and formed the western part of this tribe, with Ramla and Lidda. But other authors, among them Adrichomius, and Roger (Eugène Roger: La Terre Sainte, 1664), allocate Joppa to the tribe of Dan. The Greeks extended the setting of their myths to these shores. They said Joppa took its name from a daughter of Aeolus. They located the tale of Perseus and Andromeda in the vicinity of that city. According to Pliny (IX:IV:11), Marcus Aemilius Scaurus brought the bones of the monster created by Poseidon to Rome, from Joppa. Pausanias (IV:35:9) claimed a fountain was to be seen near Joppa where Perseus washed off the blood with which the monster had covered him: hence the fountain acquired a red tinge. Finally, Saint Jerome (Letter CVIII: To Eustochium:8) says that in his time they still showed the rock at Joppa, with the ring to which Andromeda was fastened.

It was Joppa where Hiram’s fleeted landed, laden with cedar for the temple, and from which the prophet Jonah sailed when he fled from the face of the Lord. On five occasions Joppa fell into the hands of the Egyptians, Assyrians and the various peoples who made war against the Jews, before the Romans arrived in Asia Minor. It became one of the eleven toparchies (administrative districts) in which the idol Ascarlen was worshipped. Judas Maccabeus burned this city, whose inhabitants had massacred two hundred Jews (II Maccabees 12:3-7). Saint Peter resurrected Tabitha there (Acts 9: 36-42), and received the men from Caesarea, at the house of Simon the tanner (Acts 10: 5-23). At the beginning of the troubles in Judea, Joppa was destroyed by Cestius (Josephus: The Jewish Wars:2.18.10). Pirates having rebuilt the walls, Vespasian sacked it once more, and garrisoned the citadel (Josephus:3.9.3 427).

We have seen that Joppa existed about two centuries later, at the time of Saint Jerome, who called it Japho. It passed with all of Syria under the Saracen yoke. It is found in the histories of the Crusades. The anonymous eyewitness who began the Dei Gesta per Francos (re-worked by Guibert de Nogent) said that, the crusader army being beneath the walls of Jerusalem, Godfrey of Bouillon sent Raymond Pilet, Achard de Mommellou, and Guillaume de Sabran, to guard the Genoese and Pisan ships which had arrived at the port of Jaffa: qui fideliter custodies homines and naves in portu Japhiae. Benjamin of Tudela speaks of it at about at that time under the name Gapha: Quinque abhinc leucis est Gapha, olim Joppa, aliis Joppe dicta, ad mare sita: ubi unus tantum Judaeus, isque lanae inficiendae artifex est: eight miles hence to Gapha, formerly Joppa, otherwise the Joppe of Scripture, on the coast; one Jew only, a dyer by profession, lives here. Saladin re-took Jaffa from the Crusaders, and Richard the Lion Heart took it from Saladin (1192). The Saracens returned and massacred the Christians. But at the time of Saint Louis’ first voyage to the East it was no longer in the power of the infidels; since it was held by Gautier de Brienne, who assumed the title of Count of Japhe, according to the spelling of the Sire de Joinville. ‘And when the Count of Japhe saw that the king was come, he went and put his castle of Japhe in such case, that it resembled a well-defended town. For on every battlement of his castle he had fully five hundred men, every one with a shield and a banner showing his arms. Which thing was very beautiful to behold. For his arms were pure gold, with a cross-patee gules, very richly worked. We camped in the fields all around this castle of Japhe, which was sited at sea-level, on an island. And the king began to enclose and build a fortification all around the castle, from one inlet to the other, on whatever ground was there.’

It was in Jaffa that the Queen, the wife of Saint Louis (Marguerite of Provence), gave birth to a daughter named Blanche (in 1253); Saint Louis had also received the news of the death of his mother (Blanche of Castile, in 1252) in that same city. He had thrown himself on his knees and cried out: ‘I thank my God, that you lent me my dear lady mother, so long as it has pleased your will; and that now, according your pleasure, you have taken her to you once more. It is true that I have loved her above all the creatures of the world, which she well merited; but since you have removed her from me, may your name be eternally blessed.’

Jaffa, under the domination of the Christians, possessed a suffragan bishop of the See of Caesarea. When the knights had been forced to abandon the Holy Land entirely, Jaffa with the rest of Palestine fell under the yoke of the Sultans of Egypt, and then under Turkish rule.

From that epoch, until our own time, we find Joppa or Jaffa mentioned by all voyagers to Jerusalem; but the city we see today has existed for little more than a century, since Monconys (Balthasar de Monconys), who visited Palestine in 1647, found a castle at Jaffa, and three caves carved from the rock. Thévenot says that the monks of the Holy Land built wooden huts in front of the caves, and that the Turks forced the priests to demolish them. That explains a passage in the diary of a Venetian monk. The monk says that on arrived in Jaffa, pilgrims were shut in a cave. De Brèves (François Savary de Brèves), Opdam, Deshayes (Louis Deshayes de Cormenin), Nicole le Huen, Barthélemey de Salignac; Duloir (Le Sieur du Loir: Voyages), Zuallart (Jean Zuallart), Père Roger (Voyage de la Terre Sainte) and Pierre de La Vallé are unanimous on the limited extent and wretchedness of Jaffa.

One can read in Monsieur de Volney (Constantin François de Chassebœuf, Comte de Volney) an account of modern Jaffa, the history of the sieges it suffered during the wars of Daher el-Omar and Ali Bey Al-Kabir, and other details about the excellence of its fruit, the adornment represented by its gardens, etc. I will add a few remarks.

Apart from the two fresh springs at Jaffa, cited by travellers, there are freshwater sources all along the coast, towards Gaza; one only need dig with one’s hands to strike fresh-water, even at the very edge of the waves: I myself, in the company of Monsieur Contessina, experienced that curious phenomenon, which can be replicated from the southern corner of the city as far as a hermitage, visible some distance away on the coast.

Jaffa, already ravaged in Daher’s assaults, has suffered greatly from recent events. The French, commanded by the Emperor, took it by storm in 1799. When our soldiers returned to Egypt, the English, with the help of the Grand Vizier’s troops, built a bastion at the southeast corner of the city. Abu-Marak (or Abou-Marak, the self-styled Pasha of Palestine), a favourite of the Grand Vizier, was appointed commander of the city. Djezzar, (variously Achmed Pasha, Jezzar, or Ahmed al-Jazzar) the Pasha of Acre, the enemy of the Grand Vizier, laid siege to Jaffa after the departure of the Ottoman army. Abu-Marak defended it valiantly for nine months then found an opportunity to escape by sea. The ruins visible to the east of the city are the results of that siege. After the death of Djezzar (1804), Abu-Marak was appointed Pasha of Jeddah, on the Red Sea. The new Pasha set out to cross Palestine; due to one of these uprisings so common in Turkey, he halted at Jaffa, and refused to enter on his pashalik. The Pasha of Acre, Suleiman Pasha, the second successor of Djezzar (the immediate successor of Djezzar was Ismael Pasha, who seized authority at Djezzar’s death), was ordered to attack the rebels and Jaffa was besieged again. After limited resistance, Abu-Marak took refuge with Mahamet Pacha-Adem, then appointed to the pashalik of Damascus.

I hope I will be pardoned the aridity of these details, because of the importance that Jaffa once possessed and that which it has acquired in recent times.

I waited, with impatience, for my moment of departure for Jerusalem. On the 3rd of October, at four in the afternoon, my servants dressed themselves in goat-hair tunics, made in Upper Egypt, such as the Bedouins wear; beneath my coat I had on a robe similar to those of Jean and Julien, and we mounted on small horses. Our packs served us as saddles; and ropes acted as stirrups. The head of the hospice walked in front of us, like an ordinary monk. A half-naked Arab showed us the way, and another Arab followed behind, driving before him a donkey laden with our baggage. We left from the rear of the monastery, and attained the city gate, on the south, through the ruins of houses destroyed in the last siege. At first we rode through gardens, which were once delightful: Père Néret (Charles Néret) and Monsieur de Volney praise them. These gardens have been ravaged by the various armies that have disputed the ruins of Jaffa, but there are still pomegranates, Pharaoh figs (ficus sycomoros), citrus-trees, palm-trees, clumps of prickly-pear (opuntia ficus-indica), and apple trees, which are also seen in the Gaza area, and even at the monastery of Mount Sinai.

‘Ascent of the Lower Range of Sinai’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

We advanced into the Plain of Sharon, whose beauty is praised in Scripture (see Les Martyrs XVII). When Père Néret passed by here in April 1713, it was covered with tulips. ‘The variation in their colours,’ he says, ‘forms a pleasant garden.’ The flowers that clothe this renowned landscape in the spring include pink and white roses, narcissi, anemones, white and yellow lilies, stock, and a species of fragrant immortelle. The plain extends along the coast, from Gaza in the south to Mount Carmel in the north. It is bounded on the east by the mountains of Judea and Samaria. It is not level throughout: it forms four plateaux, separated from each other by bands of bare, weathered stone. The soil is thin and coarse, white or reddish in colour, and, though sandy, appears to be extremely fertile. But thanks to the despotic Muslims, the ground on all sides offers only thistles, and dry withered grasses, interspersed with stunted patches of cotton, dura (doura: sorghum vulgare), barley and wheat. Here and there villages appear, always in ruins, with a few clumps of olive trees and sycamores. Halfway from Ramla to Jaffa, is a well, noted by every traveller: the Abbé Mariti (Giovanni Mariti: Viaggi per l’isola di Cipro e per la Soria e Palestina, 1760-68: Vol II: Chapter XVI)) mentions it, in order to have the pleasure of comparing the charity of a celebrated Dervish, who lived there, to the reclusive life of the Christian monk. Near the well a grove of olive trees is visible, planted in a quincunx, whose origin the tradition traces to the time of Godfrey of Bouillon. Rama, or Ramla, is found to be located on a charming site, at the extremity of one of the plateaux or folds of the plain. Before entering, we left the path, to visit a cistern, the work of Constantine’s mother (if we believe the local traditions, Saint Helen must have built all the monuments in Palestine, which is hardly consistent with the great age of the Empress when she made her pilgrimage to Jerusalem. Nevertheless, it is certain, according to the unanimous testimony of Eusebius, Saint Jerome and all ecclesiastical historians that Helen contributed greatly to the restoration of the holy places). One descends it by means of twenty-seven steps; it is thirty-three paces long by thirty wide; it is composed of twenty-four arches, and receives the rainfall through twenty-four openings. From there, through a forest of prickly-pears, we returned to the Tower of the Forty Martyrs, today the minaret of an abandoned mosque (the White Mosque), once the bell-tower of a monastery, of which the delightful ruins remain; the ruins are of covered arcades of a type similar to the Stables of Maecenas at Tibur (Tivoli); they are full of wild figs. One imagines that Joseph, and the Virgin and Child might have halted at such a place during the flight into Egypt: it would certainly prove a delightful setting for a depiction of The Rest of the Holy Family; Claude Lorrain’s genius seems to have divined this very landscape, judging from his admirable version in the Doria Palace in Rome (Galleria Pamphilj, 266).

On the door of the tower is an inscription in Arabic described by Monsieur de Volney: close by is a ruin, described by Muratori (Ludovico Antonio Muratori) and associated with a miracle.

After visiting these ruins, we passed an abandoned mill: Monsieur de Volney mentions it as being the only one he had seen in Syria; there are several others today. We descended to Ramla, and arrived at the hospice of the Monks of the Holy Land. This monastery had been sacked five years ago, and they showed me the tomb of one of the brothers who had perished on that occasion. The monks had finally obtained permission, after a great deal of trouble, to make most urgent repairs to their monastery.

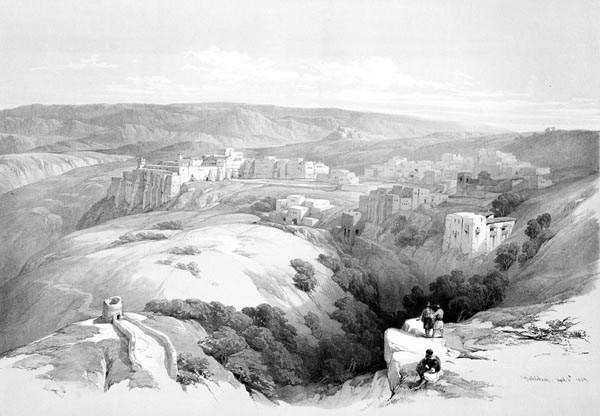

Good news awaited me at Ramla: I found a dragoman there, from the monastery in Jerusalem, whom the Custodian had sent to meet me. The Arab chieftain of whom the fathers had informed me, and who was to serve as my escort, was waiting some distance away in the countryside, since the Agha of Ramla did not allow the Bedouin to enter the city. The tribe, the most powerful in the mountains of Judea, made their residence in the village of Jeremiah (Abu Ghosh); they open and close the Jerusalem road to travellers, at will. The Sheikh of the tribe had died a short time previously; he had left his son Utman under the guardianship of his uncle Abu Ghosh: the latter had two brothers Djiaber and Ibraim Habd-el-Rouman, who both accompanied me on my return.

It was agreed that I would leave in the middle of the night. As the day had not yet ended, we dined on the terraces that form the roof of the monastery. The monasteries of the Holy Land are like fortresses heavy and overwhelming, and not in any way reminiscent of the monasteries of Europe. We enjoyed a delightful view: the houses of Ramla are mud huts, topped by a small dome like that of a mosque or a saint’s tomb; they appear set in a grove of olive, fig and pomegranate-trees, and are surrounded by large prickly-pears which take on strange shapes, their thorny palettes piled one upon another in disorder. From the midst of this confused group of trees and houses, soared the loveliest palm-trees of Idumea. In the courtyard of the monastery, there was one, in particular, that I never tired of admiring: it rose in a column to a height of more than thirty feet, where its gracefully curved branches unfurled, below which its half-ripened dates hung like crystals of coral.

Ramla is the ancient Arimathea, home of that just man who had the glory of burying the Saviour. It was at Lod, also known as Lydda, or Diospolis, a village three miles from Ramla, that Saint Peter worked the miracle of the healing of the paralytic. For the situation of Ramla with regard to trade, one may consult the Memoirs of Baron de Tott (Louis, Baron de Trott) and Monsieur de Volney’s Travels.

We left Ramla on the 4th of October, at midnight. The head priest took us by a circuitous route to the place where Abu Ghosh was waiting, and then returned to his monastery. Our group was composed of the Arab chieftain, the dragoman from Jerusalem, my two servants, and the Bedouin from Jaffa, who was driving a donkey, loaded with baggage. We held to the robes and countenances of poor Latin pilgrims, but we were armed beneath our robes.

After riding for an hour over uneven terrain, we arrived at some huts at the summit of a rocky hill. We crossed one of the ridges of the plain, and after another hour’s ride reached the first undulation of the Judean Mountains. We turned, through a rugged ravine, around an isolated and barren mound. On the top of this hillock a ruined village could be seen, and the scattered stones of an abandoned cemetery: this village bears the name of Latroun, or Latron: the home of the criminal who repented on the cross, and by so doing drew from Christ his last act of mercy (Luke 23:40-43). Three miles further on, we entered the mountains. We followed the dry bed of a stream; the moon, diminished by a half, scarcely illuminated our progress through those depths; wild boars could be heard around us uttering strange wild cries. I understood, given the desolation of these hills, why Jephthah’s daughter wanted to weep among the mountains of Judea (Judges 11:37), and why the prophets went to lament in the high places. When daylight came, we found ourselves in the midst of a labyrinth of conically-shaped mountains, somewhat similar to each other, and linked to each other at the base. The rock which formed the foundation of these mountains pierced the soil. Its bands or parallel ridges were arranged like the levels of a Roman amphitheatre, or like those stepped walls that support the vineyards in the valleys of Savoy (they were once supported in the same manner in Judea).

On each bulge of rock grew clumps of scrub-oak, boxwood, and oleander. In the ravines olive-trees lifted their heads; and there were sometimes whole groves of these trees on the mountain slopes. We heard the calls of various birds, including jays. Arriving at the highest point of the range, we saw behind us (to the south and west) the plain of Sharon as far as Jaffa, and seawards the horizon to Gaza; ahead (to the north and east) opened the valley of Saint-Jeremiah (Abu Ghosh), and in the same direction, on a rocky height, we saw in the distance an old fortress called the Fortress of the Maccabees. It is believed that the author of Lamentations was born in the village which retains his name, in the midst of these mountains (though the local tradition does not stand up to criticism). It is certain that the sadness of the place seems to breathe throughout the hymns of the sorrowful Prophet.

However, on approaching Saint-Jeremiah, I was somewhat consoled by an unexpected sight. Herds of goats with pendant ears, long-tailed sheep, and donkeys, that reminded me by their beauty of form of the onagers of Scripture, were leaving the village at daybreak. Arab women were drying grapes in the vineyards; some had their faces covered with a veil; and bore a vase full of water on their heads, like the daughters of Midian (Exodus 2:16). Plumes of white smoke rose from the hamlet, in the first rays of dawn; you could hear muffled voices, chants, shouts of joy: this scene formed a pleasant contrast with the desolation of the place and the memories of the past night. Our Arab chieftain had received in advance the permission which the tribe grants to travellers, and we passed without hindrance. Suddenly I was struck by these words pronounced distinctly in French: ‘Forward; march!’ I turned my head and saw a troop of little naked Arabs who were drilling, with palm-wood sticks. I do not know if some old memory of childhood torments me; but when I hear mention of French arms, my heart beats; and to see little Bedouins in the mountains of Judea imitating our drill and maintaining the memory of our valour; to hear them utter words that are, so to speak, the watchwords of our armies and the only ones our grenadiers know, would have been enough to touch a man less enamoured of the glory of his country than I am. I was not as startled as Crusoe when he heard his parrot speak (Defoe: Robinson Crusoe: X), but I was no less delighted than that famous voyager. I gave a few medins (silver coins) to the little battalion, saying: ‘Forward; march!’ and so as to neglect nothing, called out: ‘God willing! God willing!’ like the companions of Godfrey and Saint Louis.

From the valley of Jeremiah we descended to that of Elah (the valley of terebinth). It is deeper and narrower than the former. You find vines, and stands of sorghum there. We arrived at the river from which young David took the five stones with which he struck the giant Goliath (1 Samuel 17:2, 19). We crossed the river-bed over a stone bridge, the only one you encounter in those desert places: the river still retained a little stagnant water. Nearby, to our left, in a village called Kaloni (Colonia), I noticed among more recent ruins the remains of an ancient building. The Abbé Mariti attributed this monument to unknown monks. For an Italian traveller, the error is startling. If the architecture of this monument is not Hebrew, it is certainly Roman: the self-assurance, the dimensions, and mass of the stones can leave no room for doubt on the matter.

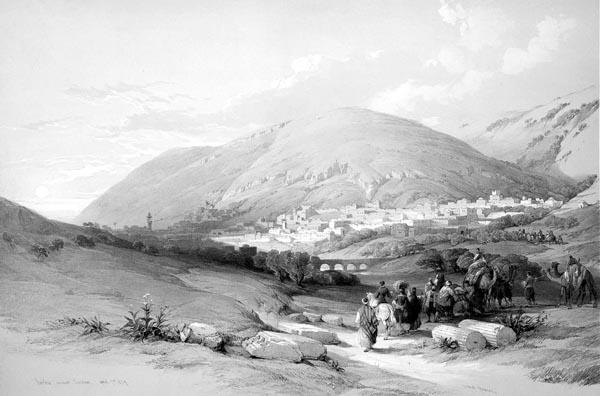

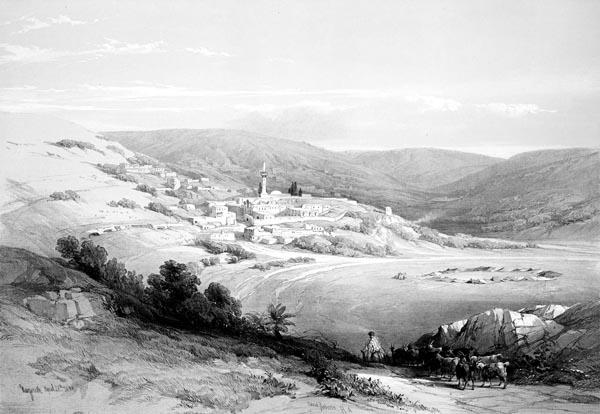

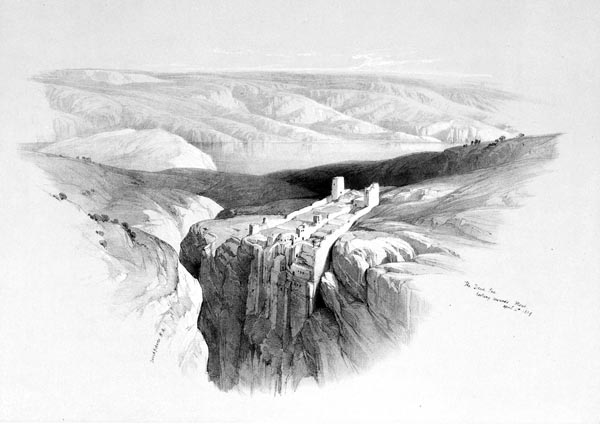

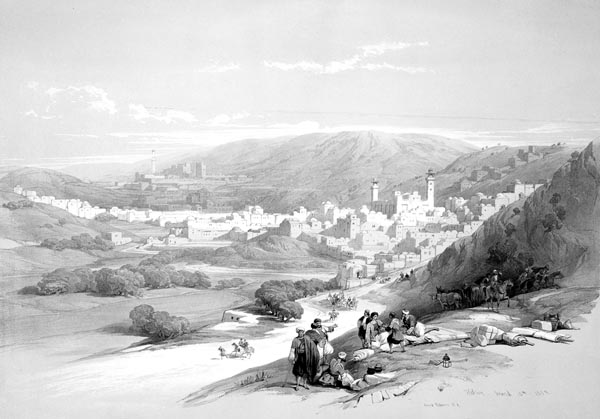

‘Nablous, Ancient Shechem’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

After passing the river, you come to the village of Keriet-Lefta at the edge of another dried-up river-bed that looks like a wide dusty track. El-Biré (al-Bireh) is visible in the distance on the summit of a high mountain, on the road to Nablus, Nabolos, or Nabolosa, the Shechem of the Kingdom of Israel and the Neapolis of the Herods. We continued to advance into a wilderness, where a scattering of wild fig trees extended their blackened leaves to the south wind. The earth, which until then had retained some green, was laid bare the mountainsides grew broader, and took on an appearance at once grander and more sterile. Soon all vegetation ceased; even the mosses disappeared. The amphitheatre of mountains was dyed a fiery red. We progressed through this desolate region for an hour, to reach an elevated pass visible in front of us. Reaching this pass, we rode for a further hour over a bare plateau, strewn with loose stones. Suddenly, at the end of this plateau, I saw a line of gothic walls flanked by square towers; behind which rose the spires of various buildings. At the foot of the walls, a camp of Turkish cavalry appeared, in all its eastern pomp. The guide exclaimed: ‘El-Kuds! The Holy City (Jerusalem)!’ and took off at full gallop (Abu Ghosh, though subject to the Grand Seigneur, was afraid of being humiliated and beaten by the Pasha of Damascus, whose camp we could see).

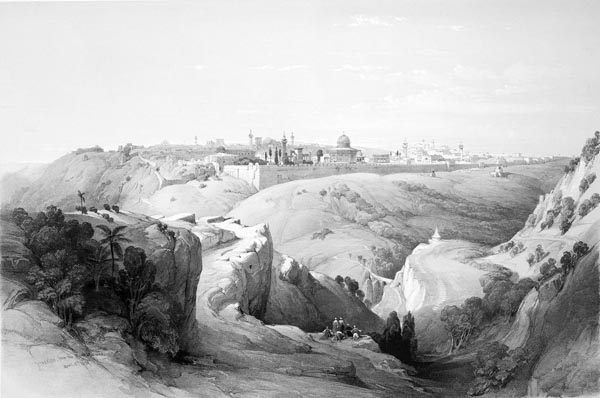

‘Jerusalem from the Road Leading to Bethany’

Holy Land, Syria, Idumea, Arabia, Egypt and Nubia - David Roberts, George Croly, Louis Haghe (1842 - 1849)

The New York Public Library: Digital Collections

I now understand what historians and travellers have related, as to the deep emotion felt by crusaders and pilgrims alike on first catching sight of Jerusalem (See Robert le Moine: Histoire de la Première Croisade:IX, also Baldric of Dol: Historiae Hierosolymitanae:IV, and Tasso: Gerusalemme Liberata:III.5, 7).

I can assure you that anyone who has, as I had, the patience to read the nigh on two hundred modern accounts of the Holy Land, the Rabbinical compilations, and the passages in the classical writers regarding Judea, still has little idea of that emotion. I halted gazing at Jerusalem, measuring the height of its walls; recalling in a moment episodes of history, from Abraham to Godfrey of Bouillon; thinking how the whole world was altered by the mission of the Son of Man; seeking in vain that temple of which not one stone is left upon another (see Luke:19:44). If I live a thousand years, I shall never forget that desert which seems to breathe again the greatness of Jehovah and the terror of death (our old French Bibles call death the king of terror).

The cries of the dragoman, who told me to close rank since we were entering the camp, roused me from the stupor into which the sight of the holy places had thrown me. We passed amongst the tents; the tents were of black sheep-skin: there were a few pavilions of striped cloth, among them that of the Pasha. The horses, saddled and bridled, were picketed. I was surprised to see four horse-drawn guns; they were well mounted, and the carriage-work looked English to me. Our slender numbers and pilgrims’ robes excited the soldiers’ derision. As we approached the city gate, the Pasha was leaving Jerusalem. I was immediately obliged to remove the handkerchief which I had thrown over my hat, to protect me from the sun, for fear of incurring an embarrassment like that of poor Joseph at Tripolitsa.

We entered Jerusalem through the Pilgrims’ Gate (the Jaffa Gate, Bab el Khalil: the Gate of the Friend). Near to this gate stands the Tower of David, better known as the Tower of the Pisans. We paid the tribute, and followed the street that lay before us: then turning left, between buildings of plaster like prisons that they call houses, we arrived, at twenty-two minutes past noon, at the monastery of the Latin fathers. It had been invaded by the soldiers of Abdallah (Azamzade Abdallah, Pasha of Damascus), to whom was given anything they found to their liking.

One would have to be in the same situation as the Fathers of the Holy Land to understand the pleasure my arrival caused them. They believed themselves rendered safe by the presence of only a single Frenchman. I delivered, to Father Bonaventura da Nola, Father Superior of the monastery, a letter from General Sébastiani. ‘Sir,’ said the Father Superior, ‘Providence brings you here. You have firmans for the journey? Allow us to send them to the Pasha; he will know that a Frenchman has arrived at the monastery; he will believe that we are under the special protection of the Emperor. Last year he forced us to pay him sixty thousand piastres; according to tradition, we only owed him four thousand, and even then simply as a gift. This year he wants to take the same amount from us, and threatens to force us to the last extremity if we refuse. We will be obliged to sell the sacred vessels; for the past four years we have no longer received alms from Europe: if this continues, we will be forced to abandon the Holy Land, and relinquish the tomb of Jesus Christ to the Muslim.’

I was only too happy to render the Father Superior this slight service. However I begged him to let me visit the Jordan, before sending the firman, so as not to add to the difficulties of a trip which is always dangerous: Abdallah could have me assassinated en route, and blame it all on the Arabs.

Father Clément Pères, procurator of the monastery, a highly educated man, with a fine, gracious and pleasant spirit, took me to the room of honour for pilgrims. My luggage was deposited there, and I prepared to leave Jerusalem a few hours after entering it. However, I was more in need of rest than of waging war with the Dead Sea Arabs. I had been travelling by sea and land for a goodly length of time in order to reach the holy places: I had barely attained the purpose of my trip, when I was off again. But I felt obliged to make some sacrifice on behalf of those monks who themselves make perpetual sacrifice of their property and their lives. Besides, I could reconcile the interests of the fathers and my own safety by abandoning a visit to the Jordan, and it was my responsibility alone to set bounds to my curiosity.