Ovid: The Art of Love

(Ars Amatoria)

Book III

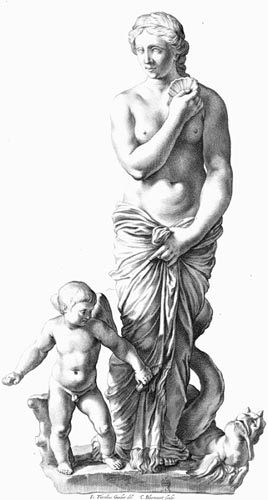

Venus - Cornelis Bloemaert (II) (Dutch, 1603 - 1692)

The Rijksmuseum

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2001 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Book III Part I: It’s Time to Teach You Girls

- Book III Part II: Take Care with How You Look

- Book III Part III: Taste and Elegance in Hair and Dress

- Book III Part IV: Make-Up, but in Private

- Book III Part V: Conceal Your Defects

- Book III Part VI: Be Modest in Laughter and Movement

- Book III Part VII: Learn Music and Read the Poets

- Book III Part VIII: Learn Dancing, Games

- Book III Part IX: Be Seen Around

- Book III Part X: Beware of False Lovers

- Book III Part XI: Take Care with Letters

- Book III Part XII: Avoid the Vices, Favour the Poets

- Book III Part XIII: Try Young and Older Lovers

- Book III Part XIV: Use Jealousy and Fear

- Book III Part XV: Play Cloak and Dagger

- Book III Part XVI: Make Him Believe He’s Loved

- Book III Part XVII: Watch How You Eat and Drink

- Book III Part XVIII: And So To Bed

Book III Part I: It’s Time to Teach You Girls

I’ve given the Greeks arms, against Amazons: arms remain,

to give to you Penthesilea, and your Amazon troop.

Go equal to the fight: let them win, those who are favoured

by Venus, and her Boy, who flies through all the world.

It’s not fair for armed men to battle with naked girls:

that would be shameful, men, even if you win.

Someone will say: ‘Why add venom to the snake,

and betray the sheepfold to the rabid she-wolf?’

Beware of burdening the many with the crime of the few:

let the merits of each separate girl be seen.

Though Menelaus has Helen, and Agamemnon

has Clytemnestra, her sister, to charge with crime,

though Amphiarus, and his horses too, came living to the Styx,

through the wickedness of Eriphyle,

Penelope was faithful to her husband for all ten years

of his waging war, and his ten years wandering.

Think of Protesilaus, and Laodameia who they say

followed her marriage partner, died before her time.

Alcestis , his wife, redeemed Admetus’s life with her own:

the wife, for the man, was borne to the husband’s funeral.

‘Capaneus, receive me! Let us mingle our ashes,’

Evadne cried, and leapt into the flames.

Virtue herself is named and worshipped as a woman too:

it’s no wonder that she delights her followers.

Yet their aims are not required for my art,

smaller sails are suited to my boat,

Only playful passions will be learnt from me:

I’ll teach girls the ways of being loved.

Women don’t brandish flames or cruel bows:

I rarely see men harmed by their weapons.

Men often cheat: it’s seldom tender girls,

and, if you check, they’re rarely accused of fraud.

Falsely, Jason left Medea, already a mother:

he took another bride to himself.

As far as you knew, Theseus, the sea birds fed on Ariadne,

left all by herself on an unknown island!

Ask why one road’s called Nine-Times and hear

how the woods, weeping, shed their leaves for Phyllis.

Though he might be famed for piety, Aeneas, your guest,

supplied the sword, Dido, and the reason for your death.

What destroyed you all, I ask? Not knowing how to love:

your art was lacking: love lasts long through art.

You still might lack it now: but, before my eyes,

stood Venus herself, and ordered me to teach you.

She said to me. then: ‘What have the poor girls done,

an unarmed crowd betrayed to well-armed men?

Two books of their tricks have been composed:

let this lot too be instructed by your warnings.

Stesichorus who spoke against Helen’s un-chastity,

soon sang her praises in a happier key.

If I know you well (don’t harm the cultured girls now!)

this favour will always be asked of you while you live.’

She spoke, and she gave me a leaf, and a few myrtle

berries (since her hair was crowned with myrtle):

I felt received power too: purer air

glowed, and a whole weight lifted from my spirit.

While wit works, seek your orders here girls,

those that modesty, principles and your rules allow.

Be mindful first that old age will come to you:

so don’t be timid and waste any of your time.

Have fun while it’s allowed, while your years are in their prime:

the years go by like flowing waters:

The wave that’s past can’t be recalled again,

the hour that’s past never can return.

Life’s to be used: life slips by on swift feet,

what was good at first, nothing as good will follow.

Those stalks that wither I saw as violets:

from that thorn-bush to me a dear garland was given.

There’ll be a time when you, who now shut out your lover,

will lie alone, and aged, in the cold of night,

nor find your entrance damaged by some nocturnal quarrel,

nor your threshold sprinkled with roses at dawn.

How quickly (ah me!) the sagging flesh wrinkles,

and the colour, there, is lost from the bright cheek.

And hairs that you’ll swear were grey from your girlhood

will spring up all over your head overnight.

Snakes shed their old age with their fragile skin,

antlers that are cast make the stag seem young:

un-aided our beauties flee: pluck the flower,

which, if not plucked, will of itself, shamefully, fall.

Add that the time of youth is shortened by childbirth:

the field’s exhausted by continual harvest.

Endymion causes you no blushes, on Latmos, Moon,

nor is Cephalus the rosy goddess of Dawn’s shameful prize.

Though Adonis was given to Venus, whom she mourns to this day,

where did she get Aeneas, and Harmonia, from?

O mortal girls go to the goddesses for your examples,

and don’t deny your delights to loving men.

Even if you’re deceived, what do you lose? It’s all intact:

though a thousand use it, nothing’s destroyed that way.

Iron crumbles, stone’s worn away with use:

that part’s sufficient, and escapes all fear of harm.

Who objects to taking light from a light nearby?

Who hoards the vast waters of the hollow deep?

So why should any woman say: ‘Not now’? Tell me,

why waste the water if you’re not going to use it?

Nor does my voice say sell it, just don’t be afraid

of casual loss: your gifts are freed from loss.

Book III Part II: Take Care with How You Look

But I’m blown about by greater gusts of wind,

while we’re in harbour, may you ride the gentle breeze.

I’ll start with how you look: good wine comes from vines

that are looked after, tall crops stand in cultivated soil.

Beauty’s a gift of the gods: how many can boast it?

The larger number among you lack such gifts.

Taking pains brings beauty: beauty neglected dies,

even though it’s like that of Venus, the Idalian goddess.

If girls of old didn’t cultivate their bodies in that way,

well they had no cultivated men in those days:

if Andromache was dressed in healthy clothes,

what wonder? Her husband was a rough soldier?

Do you suppose Ajax’s wife would come to him all smart,

when his outer layer was seven hides of an ox?

There was crude simplicity before: now Rome is golden,

and owns the vast wealth of the conquered world.

Look what the Capitol is now, and what it was:

you’d say it belonged to a different Jove.

The Senate-House, now worthy of such debates,

was made of wattle when Tatius held the kingship.

Where the Palatine now gleams with Apollo and our leaders,

what was that but pasture for ploughmen’s oxen?

Others may delight in ancient times: I congratulate myself

on having been born just now: this age suits my nature.

Not because stubborn gold’s mined now from the earth,

or choice shells come to us from farthest shores:

nor because mountains shrink as marble’s quarried,

or because blue waters retreat from the piers:

but because civilisation’s here, and no crudity remains,

in our age, that survives from our ancient ancestors.

You too shouldn’t weight your ears with costly stones,

that dusky India gathers in its green waters,

nor show yourself in stiff clothes sewn with gold,

wealth which you court us with, often makes us flee.

Book III Part III: Taste and Elegance in Hair and Dress

We’re captivated by elegance: don’t ignore your hair:

beauty’s granted or denied by a hand’s touch.

There isn’t only one style: choose what suits each one,

and consult your mirror in advance.

An oval-shaped head suggests a plain parting:

that’s how Laodamia arranged her hair.

A round face asks for a small knot on the top,

leaving the forehead free, showing the ears.

One girl should throw her hair over both shoulders:

like Phoebus when he takes up the lyre to sing.

Another tied up behind, in Diana’s usual style,

when, skirts tucked up, she seeks the frightened quarry.

Blown tresses suit this girl, loosely scattered:

that one’s encircled by tight-bound hair.

This one delights in being adorned by tortoiseshell from Cyllene:

that one presents a likeness to the curves of a wave.

But you’ll no more number the acorns on oak branches,

or bees on Hybla, wild beasts on Alpine mountains,

than I can possibly count so many fashions:

every new day adds another new style.

And tangled hair suits many girls: often you’d think

it’s been hanging loose since yesterday: it’s just combed.

Art imitates chance: when Hercules, in captured Oechalia,

saw Iole like that, he said: ‘I love that girl.’

So you Bacchus, lifted forsaken Ariadne,

into your chariot, while the Satyrs gave their cries.

O how kind nature is to your beauty,

how many ways you have to repair the damage!

We’re sadly exposed, and our hair, snatched at by time,

falls like the leaves stripped by the north wind.

A woman dyes the grey with German herbs,

and seeks a better colour by their art:

a woman shows herself in dense bought curls,

instead of her own, pays cash for another’s.

No blushes shown: you can see them coming, openly,

before the eyes of Hercules and the Virgin Muses Choir.

What to say about dress? Don’t ask for brocade,

or wools dyed purple with Tyrian murex.

With so many cheaper colours having appeared,

it’s crazy to bear your fortune on your back!

See, the sky’s colour, when the sky’s without a cloud,

no warm south-westerly threatening heavy rain.

See, what to you, you’ll say, looks similar to that fleece,

on which Phrixus and Helle once escaped fierce Ino:

this resembles the waves, and also takes its name from the waves:

I might have thought the sea-nymphs clothed with this veil.

That’s like saffron-flowers: dressed in saffron robes,

the dew-wet goddess yokes her shining horses:

this, Paphian myrtle: this, purple amethyst,

dawn roses, and the Thracian crane’s grey.

Your chestnuts are not lacking, Amaryllis, and almonds:

and wax gives its name to various wools.

As many as the flowers the new world, in warm spring, bears

when vine-buds wake, and dark winter vanishes,

as many or more dyes the wool drinks: choose, decisively:

since all are not suitable for everyone.

dark-grey suits snow-white skin: dark-grey suited Briseis:

when she was carried off, then she also wore dark-grey.

White suits the dark: you looked pleasing, Andromeda, in white:

so dressed, the island of Seriphos was ruled by you.

Book III Part IV: Make-Up, but in Private

How near I was to warning you, no rankness of the wild goat

under your armpits, no legs bristling with harsh hair!

But I’m not teaching girls from the Caucasian hills,

or those who drink your waters, Mysian Caicus.

So why remind you not to let your teeth get blackened,

by being lazy, and to wash your face each morning in water?

You know how to acquire whiteness with a layer of powder:

she who doesn’t blush by blood, indeed, blushes by art.

You make good the naked edges of your eyebrows,

and hide your natural cheeks with little patches.

It’s no shame to highlight your eyes with thinned ashes,

or saffron grown by your banks, bright Cydnus.

It’s I who spoke of facial treatments for your beauty,

a little book, but one whose labour took great care.

There too you can find protection against faded looks:

my art’s no idle thing in your behalf.

Still, don’t let your lover find cosmetic bottles

on your dressing table: art delights in its hidden face.

Who’s not offended by cream smeared all over your face,

when it runs in fallen drops to your warm breast?

Don’t those ointments smell? Even if they are sent from Athens,

they’re oils extracted from the unwashed fleece of a sheep.

Don’t apply preparations of deer marrow openly,

and I don’t approve of openly cleaning your teeth:

it makes for beauty, but it’s not beautiful to watch:

many things that please when done, are ugly in the doing:

What now carries the signature of busy Myron

was once dumb mass, hard stone:

to make a ring, first crush the golden ore:

the dress you wear, was greasy wool:

That was rough marble, now it forms a famous statue,

naked Venus squeezing water from her wet hair.

We’ll think you too are sleeping while you do your face:

fit to be seen after the final touches.

Why should I know the source of the brightness in your looks?

Close your bedroom door! Why betray unfinished work?

There are many things it’s right men shouldn’t know:

most things offend if you don’t keep them secret.

The golden figures shining from the ornate theatre,

examine them, you’ll despise them: gilding hiding wood:

but the crowd’s not allowed to approach them till they’re done,

and till your beauty’s ready banish men.

But I don’t forbid your hair being freely combed,

so that it falls, loosely spread, across your shoulders.

Beware especially lest you’re irritable then,

or are always loosening your failed hairstyle again.

Leave your maid alone: I hate those who scratch her face

with their nails, or prick the arm they’ve snatched at with a pin.

She’ll curse her mistress’s head at every touch,

as she weeps, bleeding, on the hateful tresses.

If you’re hair’s appalling, set a guard at your threshold,

or always have it done at Bona Dea’s fertile temple.

I was once suddenly announced arriving at some girl’s:

in her confusion she put her hair on wrong way round.

May such cause of cruel shame come to my enemies,

and that disgrace be reserved for Parthian girls.

Hornless cows are ugly, fields are ugly without grass,

and bushes without leaves, and a head without its hair.

Book III Part V: Conceal Your Defects

I’ve not come to teach Semele or Leda, or Sidon’s Europa,

carried through the waves by that deceptive bull,

or Helen, whom Menelaus, being no fool, reclaimed,

and you, Paris, her Trojan captor, also no fool, withheld.

The crowd come to be taught, girls pretty and plain:

and always the greater part are not-so-good.

The beautiful ones don’t seek art and instruction:

they have their dowry, beauty potent without art:

the sailor rests secure when the sea’s calm:

when it’s swollen, he uses every aid.

Still, faultless forms are rare: conceal your faults,

and hide your body’s defects as best you may.

If you’re short sit down, lest, standing, you seem to sit:

and commit your smallness to your couch:

there also, so your measure can’t be taken,

let a shawl drop over your feet to hide them.

If you’re very slender, wear a full dress, and walk about

in clothes that hang loosely from your shoulders.

A pale girl scatters bright stripes across her body,

the darker then have recourse to linen from Alexandria.

Let an ugly foot be hidden in snow-white leather:

and don’t loose the bands from skinny legs.

Thin padding suits those with high shoulder blades:

a good brassiere goes with a meagre chest.

Those with thick fingers and bitten nails,

make sparing use of gestures whenever you speak.

Those with strong breath don’t talk when you’re fasting.

and always keep your mouth a distance from your lover.

Book III Part VI: Be Modest in Laughter and Movement

If you’re teeth are blackened, large, or not in line

from birth, laughing would be a fatal error.

Who’d believe it? Girls must even learn to laugh,

they seek to acquire beauty also in this way.

Laugh modestly, a small dimple either side,

the teeth mostly concealed by the lips.

Don’t strain your lungs with continual laughter,

but let something soft and feminine ring out.

One girl will distort her face perversely by guffawing:

another shakes with laughter, you’d think she’s crying.

That one laughs stridently in a hateful manner,

like a mangy ass braying at the shameful mill.

Where does art not penetrate? They’re taught to cry,

with propriety, they weep when and how they wish.

Why! Aren’t true words cheated by the voice,

and tongues forced to make lisping sounds to order?

Charm’s in a defect: they try to speak badly:

they’re taught, when they can speak, to speak less.

Weigh all this with care, since it’s for you:

learn to carry yourself in a feminine way.

And not the least part of charm is in walking:

it attracts men you don’t know, or sends them running.

One moves her hips with art, catches the breeze

with flowing robes, and points her toes daintily:

another walks like the wife of a red-faced Umbrian,

feet wide apart, and with huge paces.

But there’s measure here as in most things: both the rustic’s stride,

and the more affected step should be foregone.

Still, let the parts of your lower shoulder and upper arm

on the left side, be naked, to be admired.

That suits you pale-skinned girls especially: when I see it,

I want to kiss your shoulder, as far as it’s shown.

Book III Part VII: Learn Music and Read the Poets

The Sirens were sea-monsters, who, with singing voice,

could restrain a ship’s course as they wished.

Ulysses, your body nearly melted hearing them,

while the wax filled your companions’ ears.

Song is a thing of grace: girls, learn to sing:

for many your voice is a better procuress than your looks.

And repeat what you just heard in the marble theatre,

and the latest songs played in the Egyptian style.

No woman taught under my control should fail to know

how to hold her lyre with the left hand, the plectrum with her right.

Thracian Orpheus, with his lute, moved animals and stones,

and Tartarus’s lake and Cerberus, the triple-headed hound.

At your song, Amphion, just avenger of your mother,

the stones obligingly made Thebes’s new walls.

Though dumb, a Dolphin’s thought to have responded

to a human voice, as the tale of Arion’s lyre noted.

And learn to sweep both hands across the genial harp

that too is suitable for our sweet fun.

Let Callimachus, be known to you, Coan Philetas

and the Teian Muse of old drunken Anacreon:

And let Sappho be yours (well what’s more wanton?),

Menander , whose master’s gulled by his Thracian slaves’ cunning.

and be able to recite tender Propertius’s song,

or some of yours Gallus or Tibullus:

and the high-flown speech of Varro’s fleece

of golden wool, Phrixus, your sister Helle’s lament:

and Aeneas the wanderer, the beginnings of mighty Rome,

than which there is no better known work in Latin.

And perhaps my name will be mingled with those,

my works not all given to Lethe’s streams:

and someone will say: ‘Read our master’s cultured song,

in which he teaches both the sexes: or choose

from the three books stamped with the title Amores,

that you recite softly with sweetly-teachable lips:

or let your voice sing those letters he composed, the Heroides:

he invented that form unknown to others.’

O grant it so, Phoebus! And, you, sacred powers of poetry,

great horned Bacchus, and the Nine goddesses!

Book III Part VIII: Learn Dancing, Games

Who doubts I’d wish a girl to know how to dance,

and move her limbs as decreed when the wine goes round?

The body’s artistes, the theatre’s spectacle, are loved:

so great’s the gracefulness of their agility.

A few things shameful to mention, she must know how to call

the throws at knucklebones, and your values, you rolled dice:

sometimes throwing three, sometimes thinking, closely,

how to advance craftily, how to challenge.

She should play the chess match warily not rashly,

where one piece can be lost to two opponents,

and a warrior wars without his companion who’s been taken,

and a rival often has to retrace the journey he began.

Light spills should be poured from the open bag,

nor should a spill be disturbed unless she can raise it.

There’s a kind of game, the board squared-off by as many lines,

with precise calculation, as the fleeting year has months:

a smaller board presents three stones each on either side

where the winner will have made his line up together.

There’s a thousand games to be had: it’s shameful for a girl

not to know how to play: playing often brings on love.

But there’s not much labour in knowing all the moves:

there’s much more work in keeping to your rules.

We’re reckless, and revealed by eagerness itself,

and in a game the naked heart’s exposed:

Anger enters, ugly mischief, desire for gain,

quarrels and fights and anxious pain:

accusations fly, the air echoes with shouts,

and each calls on their outraged deities:

there’s no honour, they seek to cancel their debts at whim:

and often I’ve seen cheeks wet with tears.

Jupiter keep you free from all such vile reproaches,

you who have any anxiety to please men.

Book III Part IX: Be Seen Around

Idle Nature has allotted these games to girls:

men have more opportunity to play.

Theirs the swift ball, the javelin and the hoop,

and arms, and horses made to go in a circle.

You have no Field of Mars, no ice-cold Aqua Virgo,

you don’t swim in the Tiber’s calm waters.

But it’s fine to be seen out walking in the shade of Pompey’s

Porch when your head’s on fire with Virgo’s heavenly horses:

visit the holy Palatine of laurel-wreathed Phoebus:

he sank Cleopatra’s galleys in the deep:

the arcades Livia, Caesar’s wife, and his sister, Octavia, started,

and his son-in-law Agrippa’s, crowned with naval honours:

visit the incense-smoking altars of the Egyptian heifer,

visit the three theatres, take some conspicuous seat:

let the sand that’s drenched with warm blood be seen,

and the impetuous wheels rounding the turning-post.

What’s hidden is unknown: nothing unknown’s desired:

there’s no prize for a face that truly lacks a witness.

Though you excel Thamyras and Amoebeus in song,

there’s no great applause for an unknown lyre.

If Apelles of Cos had never sculpted Venus,

she’d be hidden, sunk beneath the waters.

What do sacred poets seek but fame?

It’s the final goal of all our labours.

Poets were once the concern of gods and kings:

and the ancient chorus earned a big reward.

A bard’s dignity was inviolable: his name was honoured,

and he was often granted vast wealth.

Ennius earned it, born in Calabria’s hills,

buried next to you, great Scipio.

Now the ivy wreaths lie without honour, and the painful toil

of the learned Muses, in the night, has the name of idleness.

But he’s delighted to stay awake for fame: who’d know Homer,

if his immortal work the Iliad were unknown?

Who’d know of Danae, if she’d always been imprisoned,

and lay hidden, an old woman, in her tower?

Lovely girls, the crowd is useful to you.

Often lift your feet above the threshold.

The wolf shadows many sheep, to snatch just one,

and Jupiter’s eagle stoops on many birds.

So too a lovely woman must let the people see her:

and perhaps there’ll be one among them she attracts.

Keen to please she’ll linger in all those places,

and apply her whole mind to caring for her beauty.

Chance rules everywhere: always dangle your bait:

the fish will lurk in the least likely pool.

Often hounds wander the wooded hills in vain,

and the deer, un-driven, walks into the net.

What was less hoped for by Andromeda, in chains,

than that her tears could please anyone?

Often a lover’s found at a husband’s funeral: walking

with loosened hair and unchecked weeping suits you.

Book III Part X: Beware of False Lovers

Avoid those men who profess to looks and culture,

who keep their hair carefully in place.

What they tell you they’ve told a thousand girls:

their love wanders and lingers in no one place.

Woman, what can you do with a man more delicate than you,

and one perhaps who has more lovers too?

You’ll scarcely credit it, but credit this: Troy would remain,

if Cassandra’s warnings had been heeded.

Some will attack you with a lying pretence of love,

and through that opening seek a shameful gain.

But don’t be tricked by hair gleaming with liquid nard,

or short tongues pressed into their creases:

don’t be ensnared by a toga of finest threads,

or that there’s a ring on every finger.

Perhaps the best dressed among them all’s a thief,

and burns with love of your finery.

‘Give it me back!’ the girl who’s robbed will often cry,

‘Give it me back!’ at the top of her voice in the cattle-market.

Venus, from your temple, all glittering with gold,

you calmly watch the quarrel, and you, Appian nymphs.

There are names known for a certain sort of reputation too,

they’re guilty of deceiving many lovers.

Learn from other’s grief to fear your own:

don’t let the door be opened to lying men.

Athenian girls, beware of trusting Theseus’s oaths:

those gods he calls to witness, he’s called on before.

And you, Demophoon, heir to Theseus’s crimes,

no honour remains to you, with Phyllis left behind.

If they promise truly, promise in as many words:

and if they give, you give the joys that were agreed.

She might as well put out the sleepless Vestal’s fire,

and snatch the holy relics from your Temple, Ino,

and give her man hemlock and monkshood crushed together,

as deny him sex if she’s received his gifts.

Book III Part XI: Take Care with Letters

Let me speak closer to the theme: hold the reins,

Muses, don’t smash the wheels with galloping.

His letters written on fir-wood tablets test the waters:

make sure a suitable servant receives the message.

Consider it: and read what, gathered from his own words, he said,

and perhaps, from its intent, what he might anxiously be asking.

And wait a little while before you answer: waiting

always arouses love, if it’s only for a short time.

But don’t give in too easily to a young man’s prayers,

nor yet deny him what he seeks out of cruelty.

Make him fear and hope together, every time you write,

let hope seem more certain and fear grow less.

Write elegantly girls, but in neutral ordinary words,

an everyday sort of style pleases:

Ah! How often a doubting lover’s been set on fire by letters,

and good looks have been harmed by barbarous words!

But since, though you lack the marriage ribbons,

it’s your concern to deceive your lovers,

write the tablets in your maid’s or boy’s hand,

don’t trust these tokens to a new young man.

He who keeps such tokens is treacherous,

but nevertheless he holds the flames of Etna.

I’ve seen girls, made pallid by this terror,

submit to slavery, poor things, for many years.

I judge that countering fraud with fraud’s allowed,

the law lets arms be wielded against arms.

One form’s used in exercising many hands,

(Ah! Perish those that give me reason for this warning)

don’t write again on wax unless it’s all been scraped,

lest the single tablet contain two hands.

And always speak of your lover as female when you write:

let it be ‘her’ in your letters, instead of ‘him’.

Book III Part XII: Avoid the Vices, Favour the Poets

If I might turn from lesser to greater things,

and spread the full expanse of swelling sail,

it’s important to banish looks of anger from your face:

bright peace suits human beings, anger the wild beast.

Anger swells the face: the veins darken with blood:

the eyes flash more savagely than the Gorgon’s.

‘Away with you, flute, you’re not worth all that,’

said Pallas when she saw her face in the water.

You too if you looked in the mirror in your anger,

that girl would scarcely know her own face.

Pride does no less harm to your looks:

love is attracted to friendly eyes.

We hate (believe the expert) extravagant disdain:

a silent face often sows the seeds of our dislike.

Glance at a glance, smile tenderly at a smile:

he nods, you too return the signal you received.

When he’s practised, so, the boy leaves the foils,

and takes his sharp arrows from his quiver.

We hate sad girls too: let Ajax choose Tecmessa:

a happy girl charms us cheerful people.

I’d never ask you, Andromache, or you, Tecmessa

while there’s another lover for me than you.

I find it hard to believe, though I’m forced to by your children,

that you ever slept with your husbands.

Do you suppose that gloomy wife ever said to Ajax:

‘Light of my life’: or the words that usually delight a man?

Who’ll prevent me using great examples for little things,

why should we be afraid of the leader’s name?

Our good leader trusts those commanders with a squad,

these with the cavalry, that man to guard the standard:

You too should judge what each of us is good for,

and place each one in his proper role.

The rich give gifts: the lawyer appears as promised:

often he pleads a client’s case that must be heard:

We who make songs, can only send you songs:

we are the choir here best suited above all to love.

We can make beauties that please us widely known:

Nemesis has a name, and Cynthia has:

you’ll have heard of Lycoris from East to West:

and many ask who my Corinna is.

Add that guile is absent from the sacred poets,

and our art too fashions our characters.

Ambition and desire for possession don’t touch us:

the shady couch is cherished, the forum scorned.

But we’re easily caught, torn by powerful passions,

and we know too well how to love with perfect faith.

No doubt our minds are sweetened by gentle art,

and our natures are consistent with our studies.

Girls, be kind to the poets of Helicon:

there’s divinity in them, and they’re the Muses’ friends.

There’s a god in us, and our dealings are with the heavens:

this inspiration comes from ethereal heights.

It’s a sin to hope for gifts from the poet:

ah me! No girl’s afraid of that sin.

Still hide it, don’t look greedy at first sight:

new love will balk when it sees the snare.

Book III Part XIII: Try Young and Older Lovers

No rider rules a horse that’s lately known the reins,

with the same bit as one that’s truly mastered,

nor will the same way serve to captivate

the mind of mature years and of green youth.

This raw recruit, first known of now in love’s campaigns,

who reaches your threshold, a fresh prize,

must know you only, always cling to you alone:

this crop must be surrounded by high hedges.

Keep rivals away: you’ll win while you hold just one:

love and power don’t last long when they’re shared.

Your older warrior loves sensibly and wisely,

suffers much that the beginner won’t endure:

he won’t break the door down, burn it with cruel fire,

attack his mistress’s tender cheeks with his nails,

or rip apart his clothing or his girl’s,

nor will torn hair be a cause of tears.

That suits hot boys, the time of strong desire:

but he’ll bear cruel wounds with calm mind.

He burns, alas, with slow fires, like wet straw,

like new-cut timber on the mountain height.

This love’s more sure: that’s brief and more prolific:

snatch the swift fruits, that fly, in your hand.

Book III Part XIV: Use Jealousy and Fear

Let all be betrayed: I’ve unbarred the gates to the enemy:

and let my loyalty be to treacherous betrayal.

What’s easily given nourishes love poorly:

mingle the odd rejection with welcome fun.

Let him lie before the door, crying: ‘Cruel entrance!,

pleading very humbly, threatening a lot too.

We can’t stand sweetness: bitterness renews our taste:

often a yacht sinks swamped by a favourable wind:

this is what bitter wives can’t endure:

their husbands can come to them when they wish:

add a closed door and a hard-mouthed janitor,

saying: ‘You can’t,’ and love will touch you too.

Drop the blunted foils now: fight with blades:

no doubt I’ll be attacked with my own weapons.

Also when the lover you’ve just caught falls into the net,

let him think that only he has access to your room.

Later let him sense a rival, the bed’s shared pact:

remove these arts, and love grows old.

The horse runs swiftly from the starting gate,

when he has others to pass, and others follow.

Wrongs relight the dying fires, as you wish:

See (I confess!), I don’t love unless I’m hurt.

Still, don’t give cause for grief, excessively,

let the anxious man suspect it, rather than know.

Stir him with a dismal watchman, fictitiously set to guard you,

and the excessively irksome care of a harsh husband.

Pleasure that comes with safety’s less enjoyable:

though you’re freer than Thais, pretend fear.

Though the door’s easier, let him in at the window,

and show signs of fear on your face.

A clever maid should leap up and cry: ‘We’re lost!’

You, hide the trembling youth in any hole.

Still safe loving should be mixed with fright,

lest he consider you hardly worth a night.

Book III Part XV: Play Cloak and Dagger

I nearly forgot the skilful ways by which you can

elude a husband, or a vigilant guardian.

let the bride fear her husband: to guard a wife is right:

it’s fitting, it’s decreed by law, the courts, and modesty.

But for you too be guarded, scarcely released from prison,

who could bear it? Adhere to my religion, and deceive!

Though as many eyes as Argus owned observe you,

you’ll deceive them (if only your will is firm).

How can a guard make sure that you can’t write,

when you’re given all that time to spend washing?

When a knowing maid can carry letters you’ve penned,

concealed in the deep curves of her warm breasts?

When she can hide papers fastened to her calf,

or bear charming notes tied beneath her feet?

The guard’s on the look-out for that, your go-between

offers her back as paper, and takes your words on her flesh.

Also a letter’s safe, and deceives the eye, written with fresh milk;

you read it by scattering it with crushed ashes.

And those traced out with a point wetted with linseed oil,

so that the empty tablet carries secret messages.

Acrisius took care to imprison his daughter, Danae:

but she still made him a grandfather by her sin.

What good’s a guard, with so many theatres in the city,

when she’s free to gaze at horses paired together,

when she sits occupied with the Egyptian heifer’s sistrum,

and goes where male companions cannot go,

when male eyes are banned from Bona Dea’s temple,

except those she orders to enter?

When, with the girls’ clothes guarded by a servant at the door,

the baths conceal so many secret joys,

when, however many times she’s needed, a friend feigns illness,

and however ill she is can leave her bed,

when the false key tells by its name what we should do,

and the door alone doesn’t grant the exits you seek?

And the jailor’s attention’s fuddled with much wine,

even though the grapes were picked on Spanish hills:

then there are drugs that bring deep sleep,

and close eyes overcome by Lethe’s night:

or your maid can rightly detain the wretch with lengthy games,

and be associated herself with long delays.

but why use these tortuous ways and minor rules,

when the least gift will buy a guardian?

Believe me gifts captivate men and gods:

Jupiter himself is pleased with the gifts he’s given.

What can the wise man do, when the fool love’s gifts?

He’ll be silent too when a gift’s accepted.

But let the guard be bought for once and all:

who surrenders to it once, will surrender often.

I remember I lamented, friends are to be feared:

that complaint’s not only true of men.

If you’re credulous, others snatch your joys,

and that hare you started running goes to others.

She too, who eagerly offers room and bed,

believe me, she’s been mine more than once.

Don’t let too beautiful a maid serve you:

she’s often offered herself to me as my lady.

Book III Part XVI: Make Him Believe He’s Loved

What am I talking of, madman? Why show a naked front

to the enemy, and betray myself on my own evidence?

The bird doesn’t show the hunter where to find it,

the stag doesn’t teach the savage hounds to run.

Let others seek advantage: faithful to how I started, I’ll go on:

I’ll give the Lemnian girls swords to kill me.

Make us believe (it’s so easy) that we’re loved:

faith comes easily to the loving in their prayers.

let a woman look longingly at her young man, sigh deeply,

and ask him why he comes so late:

add tears, and feigned grief over a rival,

and tear at his cheeks with her nails:

he’ll straight away be convinced: and she’ll be pitied,

and he’ll say: ‘She’s seized by love of me.’

Especially if he’s cultured, pleased with his mirror,

he’ll believe he could touch the goddesses with love.

But you, whatever wrong occurs, be lightly troubled,

nor in poor spirits if you hear of a rival.

Don’t believe too quickly: how quick belief can wound,

Procris should be an example to you.

There’s a sacred fountain, and sweet green-turfed ground,

near to the bright slopes of flowered Hymettus:

the low woods form a grove: strawberry-trees touch the grass,

it smells of rosemary, bay and black myrtle:

there’s no lack of foliage, dense box and fragile tamarisk,

nor fine clover, and cultivated pine.

The many kinds of leaves and grass-heads tremble

at the touch of light winds and refreshing breezes.

The quiet pleased Cephalus: leaving men and dogs behind,

the weary youth often settled on this spot,

‘Come, fickle breeze (Aura), who cools my heat’

he used to sing, ‘be welcome to my breast.’

Some officious person, evilly remembering what he’d heard,

brought it to the wife’s fearful hearing:

Procris, as she took the name Aura to be some rival,

fainted, and was suddenly dumb with grief:

She grew pale, as the leaves of choice vine-stalks

grow pale, wounded by an early winter,

or ripe quinces arching on their branches,

or cornelian cherries not yet fit for us to eat.

As her breath returned, she tore the thin clothing from her breast,

and scratched at her innocent cheeks with her nails:

Then she fled quickly, frenzied, down the ways,

hair flowing, like a Maenad roused by the thyrsus.

As she came near, she left her companions in the valley,

bravely herself entered the grove, in secret, on silent feet.

What was in your mind, when you hid there so foolishly,

Procris? What ardour, in your terrified heart?

Did you think she’d come soon, Aura, whoever she was,

and her infamy be visible to your eyes.

Now regretting that you came (not wishing to surprise them)

now pleased: doubting love twists at your heart.

The place, the name, the witness, command belief,

and the mind always thinks what it fears is true.

She saw signs that a body had pressed down the grass,

her chest throbbed, quivering with its anxious heart.

Now noon had contracted the thin shadows,

and dawn and twilight were parted equally:

behold, Cephalus, Hermes’s child, returned to the wood,

and plunged his burning face in the fountain’s water.

You hid, Procris, anxiously: he lay down as usual on the grass,

and cried: ‘Come you zephyrs, you sweet air (Aura)!’

As her joyous error in the name came to the miserable girl,

her wits and the true colour of her face returned.

She rose, and with agitated body moved the opposing leaves,

a wife running to her husband’s arms:

He, sure a wild beast moved, leapt youthfully to his feet,

grasping his spear in his right hand.

What are you doing, unhappy man? That’s no creature,

hold back your throw! Alas, your girl’s pierced by your spear!

She called out: ‘Ah me! You’ve pierced a loving heart.

That part always takes its wound from Cephalus.

I die before my time, but not wounded by a rival:

that will ensure you, earth, lie lightly on me.

Now my spirit departs into that air with its deceptive name:

I pass, I go, dear hand, close my eyes!’

He held the body of his dying lady on his sad breast,

and bathed the cruel wound with his tears.

She died, and her breath, passing little by little

from her rash breast, was caught on her sad lover’s lips.

Book III Part XVII: Watch How You Eat and Drink

But to resume the work: bare facts for me

so that my weary vessel can reach harbour.

You’re anxiously expecting, while I lead you to dinner,

that you can even ask for my advice there too.

Come late, and come upon us charmingly in the lamplight:

you’ll come with pleasing delay: delay’s a grand seductress.

Even if you’re plain, with drink you’ll seem beautiful,

and night itself grants concealment to your failings.

Take the food daintily: how you eat does matter:

don’t smear your face all over with a greasy hand.

Don’t eat before at home, but stop before you’re full:

be a little less eager than you can be:

if Paris, Priam’s son, saw Helen eating greedily,

he’d detest it, and say: ‘Mine’s a foolish prize.’

It’s more fitting, and it suits girls more, to drink:

Bacchus you don’t go badly with Venus’s boy.

So long as the head holds out, and the mind and feet

stand firm: and you don’t see two of what’s only one.

Shameful a woman lying there, drenched with too much wine:

she’s worthy of sleeping with anyone who’ll have her.

And it’s not safe to fall asleep at table:

many shameful things usually happen in sleep.

Book III Part XVIII: And So To Bed

To have been taught more is shameful: but kindly Venus

said: ‘What’s shameful is my particular concern.’

Let each girl know herself: adopt a reliable posture

for her body: one layout’s not suitable for all.

She who’s known for her face, lie there face upwards:

let her back be seen, she who’s back delights.

Milanion bore Atalanta’s legs on his shoulders:

if they’re good looking, that mode’s acceptable.

Let the small be carried by a horse: Andromache,

his Theban bride, was too tall to straddle Hector’s horse.

Let a woman noted for her length of body,

press the bed with her knees, arch her neck slightly.

She who has youthful thighs, and faultless breasts,

the man might stand, she spread, with her body downwards.

Don’t think it shameful to loosen your hair, like a Maenad,

and throw back your head with its flowing tresses.

You too, whom Lucina’s marked with childbirth’s wrinkles,

like the swift child of Parthia, turn your mount around.

There’s a thousand ways to do it: simple and least effort,

is just to lie there half-turned on your right side.

But neither Phoebus’s tripods nor Ammon’s horn

shall sing greater truths to you than my Muse:

If you trust art’s promise, that I’ve long employed:

my songs will offer you their promise.

Woman, feel love, melted to your very bones,

and let both delight equally in the thing.

Don’t leave out seductive coos and delightful murmurings,

don’t let wild words be silent in the middle of your games.

You too whom nature denies sexual feeling,

pretend to sweet delight with artful sounds.

Unhappy girl, for whom that sluggish place is numb,

which man and woman equally should enjoy.

Only beware when you feign it, lest it shows:

create belief in your movements and your eyes.

When you like it, show it with cries and panting breath:

Ah! I blush, that part has its own secret signs.

She who asks fondly for a gift after love’s delights,

can’t want her request to carry any weight.

Don’t let light into the room through all the windows:

it’s fitting for much of your body to be concealed.

The game is done: time to descend, you swans,

you who bent your necks beneath my yoke.

As once the boys, so now my crowd of girls

inscribe on your trophies ‘Ovid was my master.’

End of The Ars Amatoria