Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXXVIII: Agramante Besieged

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXXVIII: 1-7: Ariosto regarding honour

- Canto XXXVIII: 8-11: The warrior-maidens are received by Charlemagne

- Canto XXXVIII: 12-18: Marfisa addresses him

- Canto XXXVIII: 19-21: She takes her place among her kin

- Canto XXXVIII: 22-23: And is baptised

- Canto XXXVIII: 24-28: Astolfo restores the sight of the Emperor of Nubia and Ethiopia

- Canto XXXVIII: 29-31: He imprisons the South Wind

- Canto XXXVIII: 32-35: Then attacks Agramante’s forces in Africa

- Canto XXXVIII: 36-41: Agramante seeks counsel

- Canto XXXVIII: 42-48: Marsilius advises that they continue the campaign

- Canto XXXVIII: 49-65: Sobrino argues for an honourable peace

- Canto XXXVIII: 66-69: Ruggiero and Rinaldo will duel to end the war

- Canto XXXVIII: 70-73: Melissa will aid Bradamante by preventing a fatal outcome

- Canto XXXVIII: 74-80: The two sides gather for the fight

- Canto XXXVIII: 81-87: Appropriate oaths are sworn to seal the pact

- Canto XXXVIII: 88-90: The duel between Ruggiero and Rinaldo commences

Canto XXXVIII: 1-7: Ariosto regarding honour

Courteous ladies, who kind audience

Lend to my verse (I see it in your gaze)

That Ruggiero’s taken himself hence,

So suddenly, from one he loves always,

Displeases you, and in consequence

A pain, that’s no less great in many ways

Than Bradamante’s, you endure; and claim

That low in him burns Love’s eternal flame.

If he had quit her for no greater reason,

(All against her will) than gaining treasure,

Though it might weigh far more, by the ton,

Than Crassus’ or Croesus’ in its measure,

I’d agree with you, Love’s arrow was one

That entered not his heart, for such pleasure,

Such soul’s joy, such a miracle as she,

No gold, or silver yields us, certainly.

Yet to preserve our honour, not only

Serves to excuse us, but merits praise,

And preserve it, I may add, when, truly,

Blame and ignominy might fill our days;

While greater reluctance from the lady,

An obstinacy bringing more delays,

Would have been a sign (in his defence)

Of her showing little love, and less sense.

For if her lover’s life the true lover

Should love more than her own, so much the more

(I speak of a lover here, moreover,

Whom Cupid’s dart has pierced to his heart’s core)

Should she prefer his honour to her pleasure,

And, indeed, set by it the greater store,

For we value our honour more than life,

And seek it o’er the claims of e’en a wife.

His duty to his lord, brave Ruggiero

Pursued, he could scarce do otherwise,

Since he had no true cause to up and go,

And gain but endless shame as the sad prize.

And if Almonte had slain his father, no

Blame fell on Agramante who, nowise

Guilty of his cruel father’s past offence,

Had treated the youth well in recompense.

And it was now his duty to attend

Upon his king, while his Bradamante

Her support to his doing so did lend,

Not begging him to stay; for, put simply,

The youth could at a later time amend

His sad neglect, if aught did now offend;

Two centuries would not erase the blame,

If a moment was lost to honour’s claim.

Ruggiero made for Arles, Agramante

Camping there with the remnants of his force,

While Marfisa, and his Bradamante,

Whose new-found kinship made them friends perforce,

Rode, side by side, to Charlemagne’s army,

He revealing his strength, bent on a course,

Through which he now hoped, by siege or other

Means, fair France’s freedom to recover.

Canto XXXVIII: 8-11: The warrior-maidens are received by Charlemagne

Upon reaching the camp, Bradamante

Was greeted with joy and celebration,

Saluted and welcomed midst the army

Inclining her head to many a brave one.

Rinaldo, on hearing, hastened swiftly

To meet her; Ricciardo, at the run,

Ricciardetto, and others of her kin,

Met her gladly, and escorted her in.

Once it was known that her companion

Was Marfisa, renowned for her prowess,

Who from Cathay to Spanish shores had come,

One crowned with a thousand laurels no less,

All flocked there from tent and pavilion,

A swirling crowd about the two did press,

Pushing, shoving, heaving, but to stare

Upon the beauty of that martial pair.

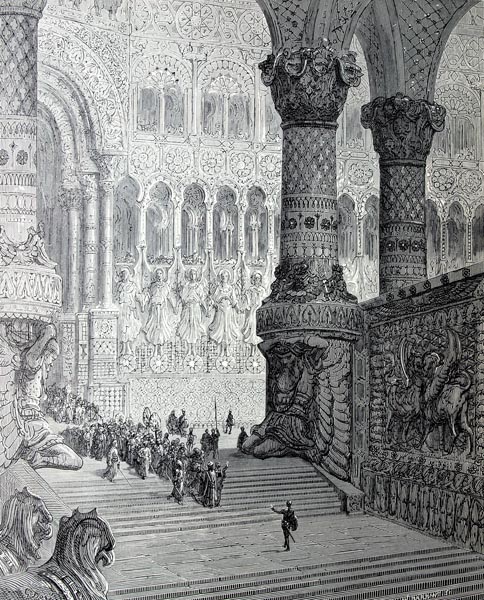

They greeted Charlemagne with reverence;

This the first day (so Bishop Turpin writes)

That Marfisa, in any king’s presence,

Bowed the knee, yet here, amidst his brave knights,

To Pepin’s son, she did so, for her sense

Of what was great, set him upon the heights,

O’er Christian or Moorish royalty,

Known for their riches or their chivalry.

Charlemagne welcomed her benignly,

Issuing from his tent to greet the maid,

And seated her at his side, royally,

Midst kings, princes, barons, there arrayed.

He gave leave to depart to the many

While a few of the good and true yet stayed;

His great lords and paladins remained,

The rest flocked outside, somewhat pained.

Canto XXXVIII: 12-18: Marfisa addresses him

Marfisa, in a grateful tone, began

‘Glorious, and unconquered, Emperor,

That East to West, makes many a man,

From Scythia, Ethiopia to this shore,

Bow to the white cross borne in your van,

King, wisest and most just, to kneel before

You here, your fame, that knows no boundary,

Has, from a distant land, thus, enticed me.

And, to speak true, envy alone moved me.

To make war on you alone, I came here,

Thinking none so powerful, so mighty,

Should rule, and yet not to my faith adhere.

For that reason, we’ve rendered this country

One pool of Christian blood and, tis clear,

Yet fiercer wrath was kindling here within,

Till one befriended me, who proved my kin.

For, while I sought to do you harm, I found

That Ruggiero of Risa was my father,

(I could at greater length the story sound)

One brought to ruin by an evil brother.

I, within my mother’s womb yet bound,

Carried o’er the sea, was in that other

Country born; raised, till seven years of age,

And then by Arabs wrested from, a mage.

Those rogues sold me, as a slave, in Persia,

To a king who, at a later time, I slew,

For my virginity he’d sought thereafter,

And all his court I slaughtered, but a few.

The kingdom I ruled, shared with no other,

And, such was my fortune, a mere two

Months short of my nineteenth year, I gained

My sixth kingdom, and o’er those realms I reigned.

And then, moved by envy of your fame,

I set my heart, as I have said but now,

On assailing the grandeur of your name,

And could, in error, have achieved my vow.

But blind chance, that has served my will to tame,

And clip my fury’s wings, has taught me how

I am come of a Christian line, and we

Are bound by ties of consanguinity.

And since my father served you, being kin,

Likewise, I bind myself to serve, also.

And that envy, that hatred felt within

Towards you once, all such I will forego.

I reserve for Agramante’s father’s sin,

And all that race, my anger born of woe;

All those that are descended from the three

That robbed me of my parents, cruelly.’

And Christianity she would embrace,

She said and, having slain Agramante,

Would seek leave to return to her own place

And see the folk baptised in that country,

And take arms against those who would replace

Her faith with the infidels’; and she

Promised that whate’er she might thus gain,

Would belong to Holy Church, and Charlemagne.

Canto XXXVIII: 19-21: She takes her place among her kin

The emperor who was no less eloquent

Than he was brave and wise, praised the maid,

And exalted her as one of true intent,

And to her father and kin tribute paid.

He replied point by point, gave his assent,

His true heart, in his face and speech, displayed,

And concluded his warm words, thereafter,

By accepting her as both kin and daughter.

Then he rose, and embraced her like a father,

And kissed her brow, while, with joyful face,

Those of Chiaramonte, and Mongrana,

Showed the maid honour, and did her grace.

Twould take too long to tell how, thereafter,

Rinaldo praised her, as of his martial race,

Whose valour he had often seen on show

When they’d besieged Albracca, long ago.

Twould take too long to tell here, also,

Of how Guidon rejoiced to see Marfisa,

And Aquilante and Sansonetto,

And Grifone (all in that city with her)

And Ricciardetto; and Viviano

And Malagigi, who when Maganza

Had sought to trade with those traitors of Spain

Found in her a true comrade, to their gain.

Canto XXXVIII: 22-23: And is baptised

All was prepared for the following day,

Charlemagne himself most carefully

Adorning, with a sumptuous array,

The platform where her baptism would be.

The bishops and the clerics paved the way,

Wise in the rites of Christianity,

So that in all its sacred lore, Marfisa,

Might be instructed, its new-found daughter.

Archbishop Turpin, suitably arrayed,

Baptised Marfisa, while Charlemagne,

From the health-giving font, raised the maid,

With fitting ceremony, once again.

But tis high time Astolfo brought his aid,

And the phial that his sense must contain,

To mad Orlando; speeding from the Moon,

In Elijah’s fiery car, and none too soon.

Canto XXXVIII: 24-28: Astolfo restores the sight of the Emperor of Nubia and Ethiopia

Down from the shining orb flew Astolfo,

To the Earth, and laned on the lofty height,

Bearing the phial destined for Orlando

(Twould end his madness, if he’d judged aright).

Once there, Saint John, to him, a plant did show,

The herb that would restore the emperor’s sight,

If, at his Nubian court, he would but touch

His eyes, with a prayer or two and such.

For, having done so, as his first reward

He’d be granted men to march on Hippo.

And how he might train them, as their lord,

Clad in plate and mail, to fight, and also

How, from the sandstorms, he might afford

Sound shelter (that blind folk when they blow);

And. point by point. the ordering of his force,

The aged saint explained, and did endorse;

Then had him mount on the winged courser,

(Ruggiero’s and Atlante’s steed before).

On taking leave of Saint John, thereafter,

His holy guide, he sought the Nile once more,

And coasting above one bank or the other,

Flying swiftly, along the river’s shore,

To the Nubian realms he came that day,

And to the Emperor Senapo made his way.

Great was the show of pleasure and delight

With which the emperor received the peer,

Who’d not forgotten how the valiant knight

Had made the Harpies things of yesteryear;

But when Astolfo then restored his sight,

The opaqueness gone, and his eyes as clear

As they had seemed at any former time,

He worshipped the peer as a god sublime:

So that not only the force he asked for,

To war against Bizerte (which was Hippo)

He gave him, but a hundred thousand more,

And then declared that he himself would go.

Travelling on foot, on that desert floor,

The Nubians, might well be hampered though;

Few were the horses that their sand dunes saw,

Of elephants, and camels, they owned more.

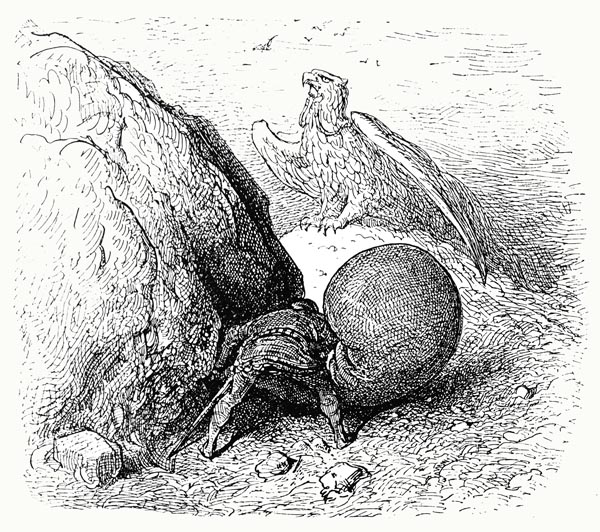

Canto XXXVIII: 29-31: He imprisons the South Wind

The night before they left (his Nubian force)

Astolfo mounted on the hippogriff,

And then flew swiftly on a southwards course,

To where Auster dwelt, on a beetling cliff;

For that angry god, the South Wind’s source,

Once he was restrained (twas when not if),

Could n’er thwart their passage (his open mouth,

Forever blew vast sand-storms from the south).

As he’d been instructed by his master,

Once Astolfo had reached the lofty cave,

O’er its vent he placed an empty bladder.

The weary wind was resting there; a brave

And silent man it took that crack to cover,

The only exit from that deep enclave.

Auster heard naught, and issuing from within,

At dawn, was held a prisoner, in that skin.

Astolfo, with the bladder, joyfully

Returned to Nubia. That very day,

Swiftly leading forth his dark-skinned army,

Supplies behind, he northwards took his way.

O’er the shifting desert lands in safety,

Towards Mount Atlas, with his whole array,

The glorious duke travelled o’er the sand,

Unharmed by captive Auster, as he’d planned.

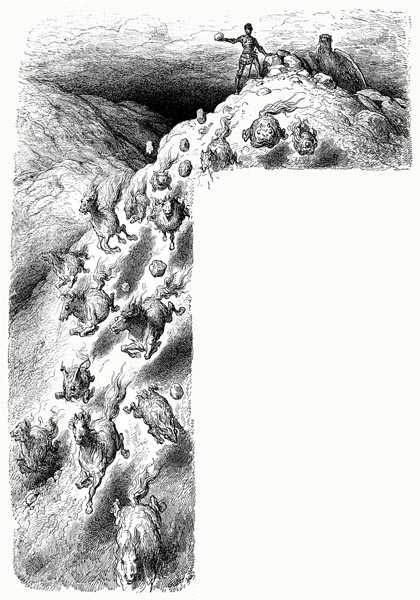

Canto XXXVIII: 32-35: Then attacks Agramante’s forces in Africa

Having gained the far side of the mountain,

Whence was visible the plain and the sea,

He chose the noblest of his force of men,

Bold, yet disciplined and orderly,

At its foot, divided them in troops, and then

Disposed them o’er the flat ground evenly.

Leaving them there, he once more climbed the steep,

Filled full of thought both reverent and deep.

For, kneeling on the summit of the mount,

He now sought aid from his holy master,

And, sure of being heard at that pure fount,

The host of pebbles there began to scatter.

What can he not do, that on Christ doth count!

The stones, descending, grew ever larger,

And, on nearing the level plain below

Heads, necks, legs, and bellies they did show!

Neighing loudly, down the slopes they sped,

Leaping lightly, till they reached flat ground,

Arching their backs, bold stallions, strangely bred,

Bay, roan, and dappled grey, yet strong and sound.

The men, who waited, found they could be led

(All were saddled and bridled); at a bound,

Astolfo had acquired his cavalry,

Each man sitting his brave steed, steadily.

His eighty thousand one hundred and two

Men on foot became horsemen, in a day,

Who scoured the plains, and sacked, and burned, and slew,

Felling all who sought to stand in their way.

King Agramante, till he was there anew,

Had left the King of Ferza to hold sway,

The Algazeris’ king, and King Branzardo,

And they it was who now opposed Astolfo.

Canto XXXVIII: 36-41: Agramante seeks counsel

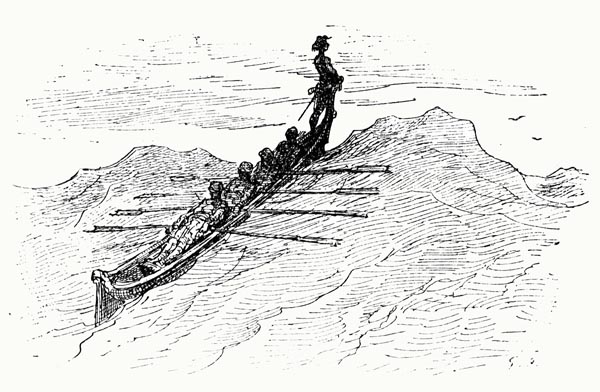

Meanwhile a barque had been sent, promptly,

That winged its way, borne by sail and oar,

To carry the news to Agramante

That his power there was less than secure.

It flew on night and day, unwearyingly,

Until it reached the far Provençal shore,

To find the king at Arles, under strain,

For camped within a mile lay Charlemagne.

Agramante, on hearing of the danger

To his realm, threatened by his French campaign,

Summoned to him, to counsel him further

All the brave kings and princes of his train;

Marsilio and Sobrino, ever

The wisest of them, caught his eye again,

And glancing at them once or twice, he then

Addressed that gathering of his noblest men:

‘Though I know it ill behoves a leader

To say “I had not planned for this” yet when

Tis from a most unexpected quarter

The blow falls, one far from the thoughts of men,

It seems a fair excuse for his failure.

Such is my case; I was in error then

In leaving our realms open to attack

From these Nubians massing at our back.

Yet who but God alone, that ever knows

What is to come on Earth, would have conceived

That from a land, through which the far Nile flows,

So great a host would come, or have believed

They could pass where the shifting sand e’er blows

O’er the wastes between us? I was deceived;

To besiege Bizerte they have come in haste,

And the shores of Africa now lay waste.

I, thus, seek your counsel on the matter,

On whether, without gaining from this war,

I should return, or not quit our venture,

Till Charlemagne, a prisoner, sees that shore;

And how then, we raise the siege, together

To be threatened by his armies no more.

Let who has aught to say, not be silent,

That the best advice might fuel our intent.’

So Agramante spoke, and turned his eye

On Marsilius, who in his glance now read

That he should be the first to make reply,

To all that Africa’s great lord had said.

The Spanish monarch, who was seated nigh

The king, knelt graciously, and bowed his head,

And then returned to take his place once more

Ere he, eloquently, addressed the floor.

Canto XXXVIII: 42-48: Marsilius advises that they continue the campaign

‘Whatever good or ill news Rumour brings

The tale forever grows in the telling.

Thus, I ne’er despair at the news she sings,

Nor am less bold, in all I’m pursuing,

Whether tis good or ill towards us wings,

Treating fear and hope alike, and holding

Them as lesser things, and beside the way,

As many a tongue affirmed in its day.

And I trust the less that news which seems

To stretch the bounds of credibility,

And here, to me, tis but a thing of dreams

That one who rules so remote a country

Would dare to set afoot such warlike schemes,

Or succeed in mustering an army,

Or cross those sands where Cambyses, tis said,

Sent his ill-omened force to join the dead.

I well believe an Arab band, or two,

Have descended the mountains to the plain,

And finding none to counter them, or few,

Have then sacked, and burned, destroyed and slain.

And that Branzardo who rules there, for you,

As viceroy in control of your domain,

Writes of thousands, where of tens he should write,

To excuse himself for his own oversight.

And if these Nubians, by some miracle,

Were to rain down from the skies above,

Or, perchance disguised as clouds, to battle

Came o’er the sands, so none saw them move,

Do you think of your men, there, so little;

Your realm at risk, if such the case did prove?

Cowards indeed your garrisons appear,

If such unwarlike peoples they now fear.

But should you choose to send a modest fleet,

As long as your banners at the masts are seen,

Rather than our bold opposition meet,

Whether tis Arabs that now haunt the scene,

Or Nubians indeed, they’ll soon retreat,

Tis through hearing you’re here with us, I ween,

And parted by the sea from your own land,

That they’ve dared to send some marauding band.

Seize this moment for revenge; Charlemagne

Is without his bold nephew, Orlando,

Scant resistance will you meet, I maintain,

If you choose to go forth against the foe.

If through blindness or neglect, you’ll not deign

To engage them, then Fortune will not show

Her shining face to you, for many a day,

To our great shame and harm; such is her way.’

Like arguments Marsilius did advance,

Seeking thus to persuade the high command

That the Moorish army should hold to France,

Till Charlemagne was banished from the land;

But Sobrino, who’d perceived, at a glance,

The plan Marsilius would put in hand,

Preferring public good to private gain,

Said this, in answer to the King of Spain:

Canto XXXVIII: 49-65: Sobrino argues for an honourable peace

‘My lord, when I exhorted you to peace,

If but my prophecy had not proved true,

Or you had placed a little trust, at least,

In me, ere my foresight was shown anew,

And not in those men that I’d be pleased,

To view here, at this moment, before you,

Alzirdo, Marbalusto, Martasino,

And Rodomonte, who boasted so

Of wishing to shatter France like glass,

Following you to heaven or to hell.

E’en your royal self he sought to pass,

And send the Christians fleeing pell-mell;

Yet now, immersed in idleness, alas,

In your time of need, he with sloth doth dwell.

While I, that as a coward was decried

For my true prophecy, am at your side;

And will be so, until I reach the end

Of this life, bowed by a weight of years,

And every day your honour will defend

Against the bravest among France’s peers.

For there’s none dare say, be he foe or friend,

That my actions proved ill, despite my fears.

And none has done as much amidst this host,

Some far less, that of their deeds now boast.

This I declare, to show that everything

That I said before, and now say again,

Comes from a firm heart, noble, unflinching,

Faithful, and full of truth, inured to pain.

I counsel you to think now of departing,

And returning swiftly to your own domain.

For little wisdom has that man, my brothers,

That would lose his own to gain another’s.

If this be gain, you know: full thirty-two

Brave vassal kings of yours left Africa,

Yet if we pause to count those kings anew,

Scarcely a third survive; may no further

Losses, God be pleased, henceforth accrue:

If you will pursue this quest, however,

I fear lest not a fourth or fifth remain,

And we yet leave the field to Charlemagne.

It aids us that our foe lacks his Orlando,

For where our men are few, none might there be,

But that does little to remove our woe,

Though it delays our fate. Behold we see

No less brave a knight, I mean Rinaldo,

To whom this fight but seems his destiny;

And then his bold race are warriors all,

Whose acts and deeds our Saracens apall,

For a second Mars, a second God of War,

(Although it grieves my heart to praise the foe)

Goes with him, Brandimarte; on a par

In terms of prowess with bold Orlando.

His skills I’ve proven, or have viewed afar,

Or heard from others, and have learned tis so.

Though, of their force, Orlando makes not one,

Still have we lost more fields here than we’ve won.

If we have lost great noblemen to date,

I yet fear we’ll lose far more in future.

Mandricardo has met a grievous fate;

Gradasso has ceased his martial succour,

While Marfisa has left her post of late,

And Rodomonte dwells here no longer;

Were he as true, as he’s brave, gainst the foe,

Less need for Gradasso, Mandricardo.

And while we have lost the aid of those four,

And many thousands, on our side, lie dead,

And our champions are present on this shore

With none left to be furnished in their stead,

Charlemagne is but re-supplied with more;

Like to Orlando and Rinaldo bred,

No less brave, for from here to Bactria

Such as his recruits you’ll hear of never.

Of Guidon Selvaggio you may know,

And three whom I both respect and fear,

Sansonetto, and the sons of Oliviero,

More than every other bold knight or peer

Of Germany or elsewhere, that doth show

Allegiance to the Christian Empire here,

High though I rate those of newer stamp

That, to our cost, are gathered in that camp.

As often as you ride forth on that plain,

So oft will you be scattered o’er the field.

If we, the men of Africa and Spain,

With twice their strength, were yet obliged to yield,

What will ensue when France, renewed again,

With Germany, Italy, England for her shield,

And Scotland too, but half their number meet?

What will we know, but loss and sore defeat?

If you prove obstinate, and seek to stay

You’ll lose your people here, and there your land,

While if we now depart, you’ll save the day,

Your kingdom, and the forces now to hand.

To quit Marsilius, would bring shame, I say,

Since your friends would blame you, yet understand,

The remedy is peace with Charlemagne;

If it pleased you, he would agree that same.

Though it might seem there is small honour there,

If you seek peace, who sought not enmity,

And though you would prolong this whole affair,

Which meets with scant success, as you may see,

At least, if you’d be ruled by me, take care,

And perchance by craft achieve the victory.

Let our quarrel lie with but a single foe,

And let our champion be Ruggiero.

For our knight is such, you and I both know,

That in fighting hand to hand, one on one,

He’s a match for Orlando, Rinaldo,

Or any other warrior neath the sun.

But if to universal war you go,

Though more than mortal are the deeds he’s done,

He’s but one man amongst a host of men,

And faces as great a host, and what then?

It seems to me, if it seems good to you,

That you should seek an end to this conflict.

To spare the waste of blood that would ensue,

The harm each side would certainly inflict.

Say to the Christian king, allow but two,

His champion and yours, and both hand-picked,

To dispute the whole question of this war,

Till one conquers, and the other breathes no more.

Let the pact be that he whose champion

Fails, shall pay tribute to the other.

This should not displease the Christian,

Who thinks his warrior is the greater;

While our Ruggiero, set man to man,

Will more than hold his own, and conquer.

The right is with him, in this cause of ours;

He’d succeed, though his enemy were Mars.’

With this, and many a sound argument,

Sobrino gained the end he had in sight,

And, on that day, interpreters were sent

To Charlemagne to offer peace outright.

He, seeing the advantage, gave consent,

Thinking the war now won, for the knight

He chose to fight the duel was Rinaldo,

Trusting in none more, except Orlando.

Canto XXXVIII: 66-69: Ruggiero and Rinaldo will duel to end the war

Those of both armies welcomed the accord,

For weary both in body and in mind,

This pact would a well-earned rest afford,

And all could there a source of comfort find;

To pass what time their fate would yet afford

In quiet, and sweet repose, all were inclined,

And all now cursed the hatred and the ire

That had filled their hearts with warlike desire.

Rinaldo was seen to be elated,

That he was trusted so by Charlemagne,

Whom the emperor had so highly rated,

And glad to undertake this prize to gain.

Ruggiero’s skills he thought over-stated,

That he was bound to win, with little pain,

And deemed Ruggiero the lesser knight,

Though he’d slain Mandricardo in fair fight.

Ruggiero, though honoured for his part,

On being chosen likewise by his king,

As better than the rest in warlike art,

And so trusted to accomplish this thing,

Nonetheless revealed a troubled heart

In his gaze, though ne’er the duel fearing,

For he went not in dread of Rinaldo,

Though he were leagued gainst him with Orlando,

But because he knew the Christian knight

Was brother to the maid that he held dear,

That in her every word she chose to write

Had complained of his failures, loud and clear.

If with such errors he must now unite

This mortal duel, where both must appear,

He’d prove so hateful to her, as a lover,

She well might be lost to him forever.

Canto XXXVIII: 70-73: Melissa will aid Bradamante by preventing a fatal outcome

If Ruggiero lamented, silently,

This battle, that scarcely augured well,

A stream of tears flowed from Bradamante,

On hearing news of all that there befell,

Wetting her fair cheeks, and breast completely,

The latter of which she beat upon as well,

And tore her hair, and called Ruggiero

Ungrateful, and cruel, and her fate more so.

Whatever was the outcome of the fight,

To her it promised naught but bitter pain,

If Ruggiero proved the lesser knight,

And died there, twould break her heart in twain;

Yet if Christ would see the fall of France’s might,

To punish her for faults that honour stain,

She’d mourn a second wound, deep and bitter,

Besides the loss of her beloved brother,

For she could not, without scorn and blame,

And the dire enmity of all her kin,

Return to Ruggiero, his fondness claim,

(Unless twere secretly, as if in sin)

For she had thought to do that very same,

Musing upon it, night and day, within;

And such a promise lay betwixt the two,

That neither could withdraw, nor wanted to.

But she, who, when things were adverse, ever

Appeared her most faithful, and helpful friend,

I mean, of course, the mage, kind Melissa,

Hastened now to console her, and amend

Her trouble, sore pained to see her suffer;

And came in time her doubts and woes to end,

Saying she would end the duel proposed,

That such a threat to love and life now posed.

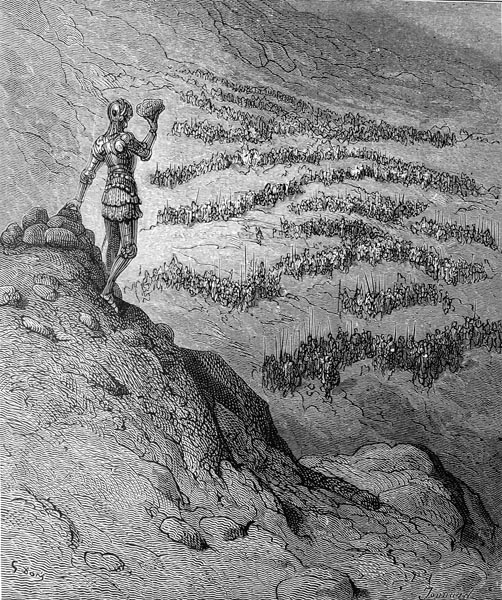

Canto XXXVIII: 74-80: The two sides gather for the fight

The two prepared, meanwhile, for the fight,

I refer to Rinaldo and Ruggiero,

The choice of weapons resting with the knight

That championed the Empire, Rinaldo;

He, as one who on foot e’er showed his might

Since he had lost his fine steed, Baiardo,

Decided now, armoured in such metal

As served, with axe and dagger to battle.

Whether moved to do so by mere chance,

Or because Malagigi, deep and wise,

Knew how e’en the finest sword of France

Might be shattered in this mortal enterprise,

By sharp Balisarda, nor sword nor lance

He chose; while Ruggiero armed likewise.

Close to the wall of ancient Arles, the place;

They’d meet, on level ground, there, face to face.

Scarcely had the watchful Aurora

Put forth her head from Tithonus’ dwelling,

Accompanying the light of day, as ever,

The day which this duel now would bring,

When the deputies came there to gather,

Issuing from both sides, then securing

Two pavilions at each end of the ground,

And raising an altar on a nearby mound.

Not long after this, many a squadron

Of Moorish warriors appeared, row on row,

And rich in barbaric pomp came on

Africa’s king, armed to address the foe.

Twas a black-maned bay steed he sat upon,

With snowy brow, and two legs pied also;

And beside Agramante, came Ruggiero,

Attended by no less than Marsilio,

Who the helm Ruggiero had gained now bore,

Wrested with such pain from Mandricardo;

Twas Hector’s helm two thousand years before,

And celebrated in a greater canto

Than is mine, such helms ancient heroes wore;

Here other lords and princes bore, also,

The rest of his armour, set with gold,

And enriched with rare pearls, and gems untold.

From the other side came Charlemagne,

With equal squadrons in battle order,

The same disposition they’d maintain

If asked to fight, each man a warrior.

His famous peers did his great pomp sustain,

And with him came Rinaldo, in like manner,

Armed save his helm, once worn by Mambrino,

Borne here by the Dane, brave Ugiero.

One of the two axes, Duke Namo bore,

To the field, the other King Salamon,

On the one side the host of France one saw,

To the other Agramante’s host had gone.

An empty space lay twixt the sides, the floor

Assigned, and none allowed to walk thereon,

But for the pair of warriors, who would fight;

Twas death to any who that rule did slight.

Canto XXXVIII: 81-87: Appropriate oaths are sworn to seal the pact

Once the choice of daggers had been made

By Ruggiero, ere the duel began,

Two holy functionaries next conveyed

A book from either side, the Christian

The Gospel carried wherein is displayed

Christ’s perfect life, the Moor the Koran.

The emperor took the Gospel in his hand

King Agramante the other did command.

At the altar, he’d decreed, Charlemagne

Raised his hands towards the sky and said:

‘O God that suffered death, in bitter pain,

To redeem our sinful souls and from the dead

Raise us up; Lady, whom He did sustain,

That in the flesh He might on Earth thus tread,

Borne for nine months in your sacred womb,

While yet the virgin flower preserved its bloom,

Bear witness to the promise that I make,

For myself and those who rule after me:

To King Agramante and those who take

Command, later, of his realms, full twenty

Loads of gold each year we shall forsake,

And grant to them, if they have victory;

And I promise the war on them shall cease

At once, and pledge henceforth perpetual peace;

And if I fail, may your dread wrath descend,

Upon me, may you scourge us equally,

I and my heirs, if we should so offend;

Yet none but I, and my sinful family,

So that all others swiftly comprehend

My breach of promise wrought the misery.’

In his hand he held the book that Christians prize,

Fixing his solemn gaze upon the skies.

That done they sought a place which, equally,

The Moors had set aside upon the plain,

Where Agramante swore to cross the sea,

With his men, into Africa again,

And pay tribute to France, if it should be

That Rinaldo the victory did gain;

And would observe the pact for evermore,

On the terms Charlemagne had set before.

And, likewise, in a strident voice, he swore

Calling on Mohammad as his witness;

And upon the book that his imam bore,

Pledged to perform all this, and no less.

The two having followed their own lore,

Repaired to their tents, to await success.

And then their champions upon the plain

Swore an oath their honour to maintain.

First Ruggiero swore that should his king

Attempt to mar their duel, or end the fight,

He would obey him not in anything,

But on Charlemagne attend, as his knight.

While Rinaldo swore a similar thing,

That, if Charlemagne intervened outright,

So that neither he nor Ruggiero

Could win, to Agramante he would go.

Canto XXXVIII: 88-90: The duel between Ruggiero and Rinaldo commences

Each of them returned to his own side,

Once these ceremonies were complete,

Nor waited long ere the trumpets cried

The moment that in combat they must meet.

Now carefully measuring each his stride

They advanced, seeking to avoid defeat.

And lo, the assault began; now high, now low

The sharpened steel rang out at each fierce blow.

Now with the axe’s heel now with the blade

They struck at head and foot, to win success;

Revealed their great strength, and such art betrayed

As would pass belief could I their skill express.

Ruggiero faced the brother of the maid,

Who did his troubled heart and soul possess,

With such caution, with such subtle blows,

That he was thought the lesser of the foes.

He sought to parry rather than to kill,

Having scant desire to slay Rinaldo,

Uncertain of his own desire, yet still

Most unwilling to be slain, even so.

Yet here I must rest awhile, and will

Pursue the matter in another canto;

To the next I’ll defer this canto’s tale,

If upon your patience I might prevail.

The End of Canto XXXVIII of ‘Orlando Furioso’