Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XXIX: Orlando's Wanderings

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XXIX: 1-2: Ariosto’s pledge to the ladies

- Canto XXIX: 3-7: Rodomonte hurls the monk into the sea

- Canto XXIX: 8-12: Isabella seeks to evade his clutches

- Canto XXIX: 13-18: And devises a deception

- Canto XXIX: 19-24: She proposes a trial

- Canto XXIX: 25-30: And sacrifices herself to preserve her chastity

- Canto XXIX: 31-34: Rodomonte constructs a mausoleum

- Canto XXIX: 35-39: The passage o’er the river

- Canto XXIX: 40-43: Orlando appears and attempt to cross

- Canto XXIX: 44-47: Fiordelisa witnesses the fight

- Canto XXIX: 48-50: Of Orlando’s wanderings and feats

- Canto XXIX: 51-56: He encounters two youths in the Pyrenees

- Canto XXIX: 57-63: Angelica and Medoro encounter him on the shore

- Canto XXIX: 64-66: She employs the ring and vanishes

- Canto XXIX: 67-71: Orlando pursues and seizes her mare

- Canto XXIX: 72-74: Then continues on his mad way

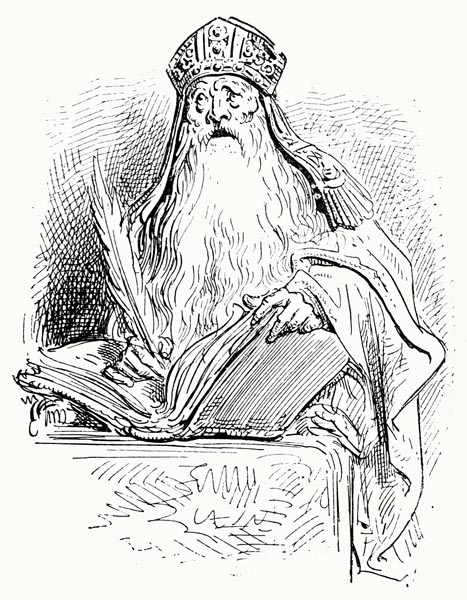

Canto XXIX: 1-2: Ariosto’s pledge to the ladies

O the infirm, unstable minds of men!

How swift they are to alter in intent!

Our thoughts we change, and most easily when

They are born of a lovelorn discontent.

Earlier, I perceived the Saracen

To his scorn of women such ardour lent,

Not only did I think he’d ne’er forego

His anger, but would ever simmer so.

Gentle ladies, all that he sought to utter

Against you, while upon you heaping blame,

So offends, that, till he is taught his error,

I’ll not pardon him; I’ll blacken his name.

With pen and ink, I’ll grant him no quarter,

Till all men perceive, from that very same,

Twere best to hold, or better still to bite,

Their tongues than speak ill of you outright.

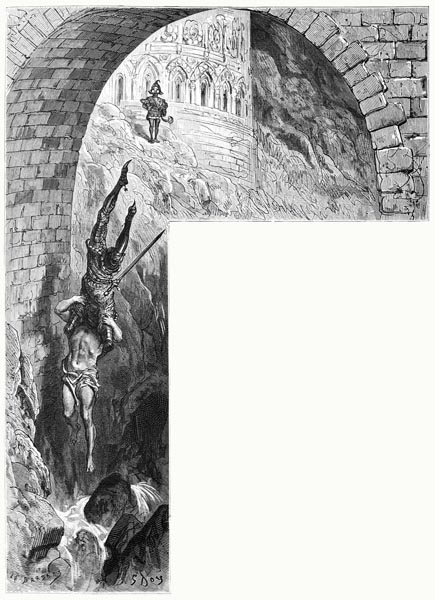

Canto XXIX: 3-7: Rodomonte hurls the monk into the sea

That he spoke in ignorance and folly,

Is clearly demonstrated by our tale;

His anger he displayed, indifferently,

Against all women, yet to no avail;

One glance at Isabella, and swiftly

Another mode of speech did prevail.

Though he’d scarce seen her, and knew her not,

His other love already was forgot.

And, being pricked and burned by this new love,

He offered arguments of scant merit,

Her sound and settled mind and heart to move,

Which she had fixed on God; while the hermit,

As her shield and armour, now sought to prove

Lest the maiden’s chaste thoughts should such permit,

With stronger arguments, that he was right,

And, thus, aimed to protect her from the knight.

Rodomonte, though, thinking he’d suffered

The monk’s bold and irritating sermon

Long enough, his own advice then offered,

That to his hermit’s cell he should be gone,

Without her, but finding he yet proffered

His arguments, and would ne’er have done,

He laid fists upon the valiant monk at will,

And whate’er he struck was striking still.

And, as with tongs the smith will grasp the steel,

He now grasped him by the neck, furiously,

Whirled him twice about his head, in his zeal,

And hurled him far, into the raging sea.

I know not, and so cannot here reveal,

What became of him (the rumours vary);

Some say he met the stony reef below,

And all his bones were shattered, head to toe.

Some insist that a graceful arc he made,

Flying two or three miles before he fell,

Yet, despite the fervency with which he prayed,

Not knowing how to swim, was drowned; some tell

Of a patron saint who came to his aid,

Whose saving hand was visible as well!

Whate’er might be the truth of the matter,

In this tale, you’ll hear of him no further.

Canto XXIX: 8-12: Isabella seeks to evade his clutches

Cruel Rodomonte, having sent him flying,

With a less troubled visage, now applied

His efforts to comforting and wooing

The sad, bewildered woman at his side,

She was his very heart and life, employing

The language use by lovers, thus, he cried;

His comfort and his fondest hope, was she;

With other phrases still used commonly.

And he showed himself so temperate now,

That not a sign of violence was revealed.

The gentle eyes beneath her lovely brow,

Subdued the pride in him, now well-concealed,

And though he possessed the power to cow

The maiden, he’d not force her, thus, to yield,

For possession was ill, he yet believed,

Unless as a gift from her twere received.

And so, he thought to mould Isabella,

By degrees, to his desire, while the maid

In that secluded place, alien to her,

Like a mouse with which a cat now played,

Had much rather be plunged in the water;

While, her mind, but one thought conveyed,

Twas that of seeking, ere she was attacked,

A means to remain untouched, and intact.

Thus, she resolved that she would seek to die,

By her own hand, before the barbarous king

Could compass his fell intent, though thereby

She’d betray her pledge made to the dying,

Her dear Zerbino, for, when he did lie

In her arms, she had promised no such thing,

But to live, devoted to his memory,

While vowing perpetual chastity.

She thought Rodomonte’s passion growing,

And seeing this, she knew not what to do,

Believing he’d assault her, on this showing,

She unable to contest the issue.

Yet, within herself furiously debating,

She found at last a course she might pursue,

To save her chastity, and through that same,

As I shall tell, acquire enduring fame.

Canto XXIX: 13-18: And devises a deception

To the cruel Saracen, who, already,

Had revealed, by his words, his true intent,

For he’d put by all that passing courtesy

Which at first to his sweet discourse he’d lent,

She said: ‘Preserve my honour, entirely

Beyond suspicion, and I’ll be content

To grant you a gift that is far greater

Than aught won by robbing me of honour.

For the sake of the pleasures of a moment,

Of which, on Earth, there is ample supply,

Despise not the perpetual contentment,

The joy, second to none, I’ll not deny.

A hundred, a thousand, will give assent,

Fair maidens, ever pleasing to the eye,

But there are few or none, perchance, that live,

That can grant you the gift that I can give.

For a herb I viewed, as I came on my way,

And I recall where I did see the thing,

That boiled with rue and ivy, for a day,

O’er a fire of cypress wood simmering,

And then squeezed in a virgin’s hands, I say,

Gives a juice such that when a valiant king

Bathes his flesh thrice, such virtue he’ll acquire

Twill protecs him thenceforth from steel and fire.

If he anoints himself thrice, as I’ve said,

For a month, then, he’ll be invulnerable,

And then every month, from heel to head,

Since for only so long is it powerful.

This I can work, before the sun has fled,

And thereby you may prove if I’m truthful.

And, if I’m not wrong, more grateful you’ll be

Than if o’er Europe you won sovereignty.

As my reward, I but demand of you,

That, upon your sword, you swear to me

That you will attempt naught that’s untrue,

And, in word and deed, respect my chastity.’

At this the knight his passion did subdue,

For so great a desire had Rodomonte

For that protection he’d have accepted

More than Isabella now requested.

He would obey her till the thing was done,

And the marvellous liquid was achieved,

And ensure, until its virtue was won,

That no sign of violence was perceived.

But he vowed that same pact to abandon,

Thereafter, as a man who’d ne’er believed

In God or His saints and, like faith lacking,

Thus, wayward Africa yielded to this king.

Canto XXIX: 19-24: She proposes a trial

To Isabella, Rodomonte swore,

A thousand times, he’d not molest her,

As long as he could win what long before

Achilles had, and Cygnus, from another.

So, she, from cliffs and dells, along the shore,

Far from any human gaze, did gather

A store of herbs, while the Saracen

Kept an eye on her, ever and again.

When she’d gathered enough, from every place,

With roots or without, to serve her aim,

They returned, as cool shade the Earth did grace;

And all that night she boiled and squeezed those same,

That paragon of continence, her face

And every action observed (in this game)

By the Saracen, who watched, most carefully,

As she rehearsed that arcane mystery.

Rodomonte spent the night though drinking,

And so did his people who remained,

For the heat from her fire had him sweating,

And was then in such a small space contained

He was parched, and drank, without thinking,

Till between them two barrels they had drained,

Of Grecian wine that a few days before,

Had been seized by the squires who served the Moor.

Now Rodomonte was unused to wine

Because his creed denied it him, by law,

So, to his taste the liquor seemed divine,

Sweet as nectar or manna, or yet more.

Great cups of it he quaffed, and thought it fine,

Thus, resuming the pagan rites of yore.

He drank the potent wine, and drank it still

Though his head turned like the wheel of a mill.

Meanwhile, the maiden lifted from the fire

The cauldron in which she’d boiled the lot,

And said to the monarch: ‘Since I aspire,

To prove, thus, that my pledge is not forgot,

And that lies are quenched by truth we acquire

Through experience, with what’s in the pot,

I’ll demonstrate its virtues; not on you,

But first upon myself, to show tis true.

I will, ere you attempt it, try the liquor,

Happily, blessed with power and virtue,

Upon myself, lest you’re fearful of danger,

And think symptoms of poison may ensue.

I’ll anoint myself with it, all over,

From my head down to my breast, and then you

May with your sharpened sword demonstrate

Herein lies power enough to counter fate.’

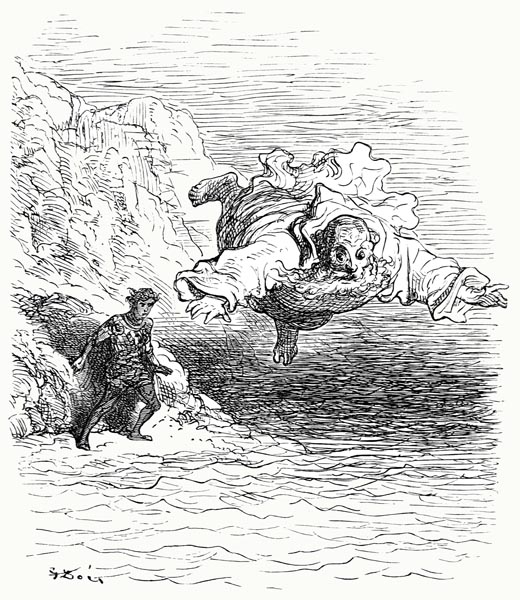

Canto XXIX: 25-30: And sacrifices herself to preserve her chastity

She bathed herself, head to breast, as she’d said.

Before the unthinking pagan, filled with wine;

Then she knelt, bared her neck, and bowed her head.

His blade, which on helm and shield did dine,

Then fell (an act of faith), and struck her dead,

So true the steel; thus, furthering her design.

That head, where Love had found a place to rest,

Was severed from the snowy back and breast.

Thrice it bounced, and then was clearly heard

A voice that proclaimed Zerbino’s name,

To follow whom that death she had incurred,

While fleeing Rodomonte and vile shame.

Soul, that held faith dearer, in a word,

And, nigh unknown to our age, the sweet name

Of chastity, to us an alien thing,

Dearer than life to you, and your green spring,

Soul, go in peace, forever blessed and fair!

Oh, if my tongue had but the power to show

Your virtues, with what endless joy and care

I’d ply my art, that grant verse here below

Rare beauty, so the light that you shed there,

Should for ten thousand years, hereafter, glow!

Depart in peace, to that sweet realm above,

And leave to Earth the story of your love.

Upon that deed, unequalled, tremendous,

The Creator, in heaven, turned his eye,

And said: ‘I deem her act as virtuous

As Lucretia’s ousting Tarquin thereby,

And I shall make a law, impervious

To time, and swear, though I am here on high,

By the inviolable river below,

That ages yet to be this law shall know:

I decree that, in future, all who bear

Her name shall be blessed with genius,

The banner of true honour they shall share,

And be noble, wise, fair, and courteous,

That to all writers matter rich and rare

They may supply, and so on Parnassus,

And Pindos’ spur, Helicon, forever,

“Isabella” shall sound; fair “Isabella”.

So spoke the Lord, and rendered all the air

About the place serene, and calmed the sea.

Her chaste soul to the third sphere did repair,

To her Zerbino, for eternity.

On Earth, with shame and scorn for his share,

A second ‘Breuse sans Pitié’, we see,

Who, once he had recovered from the wine,

Cursed his error; though not one to repine.

Canto XXIX: 31-34: Rodomonte constructs a mausoleum

Yet the blessed soul of Isabella,

He thought to placate to some degree,

Although of her death he was the author,

And at least give life to her memory,

While the means was easy to discover:

He could convert the church readily

To a sepulchre, near where she had died,

In which the lovers’ relics might abide.

He brought stonemasons there from all around,

Some came out of respect, some out of fear.

Six thousand there were that he thus found,

That quarried stone from the hills, far and near.

Ninety yards, from the top to the ground,

Was the wall that they built, both strong and sheer,

To enclose the church where Isabella

And Zerbino were entombed together.

Twas like that which Hadrian constructed,

(Castel Sant’Angelo) by the Tiber,

And a tower by its side he erected,

Intended as his own brave sepulchre,

With a bridge, six feet wide, that connected

That site to the far bank of the river.

Long and narrow was the bridge, while a pair

Of steeds could barely pass each other there.

Two great coursers yet might meet together,

Or rather clash together on its height,

Nor at each side was there any barrier,

To guarantee the passage of a knight.

He would pay a heavy toll, the traveller,

Moor or Christian, who’d pass it and alight,

For, a thousand trophies, the monarch swore,

Would adorn the maid’s tomb, from roof to floor.

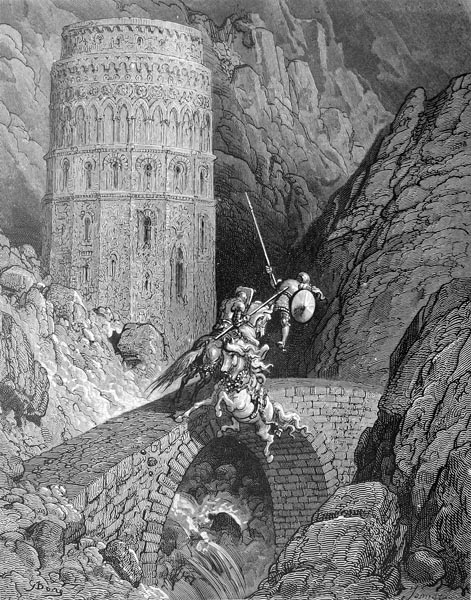

Canto XXIX: 35-39: The passage o’er the river

Ten days or so it took to span the river

With the bridge, that arched o’er the stream below,

While the wall and the tower took far longer,

Though presenting, when done, a mighty show.

A guard, on the summit of the latter,

Upon his bugle a warning would blow,

Whene’er to the bridge a knight sought entry,

Alerting his master, Rodomonte,

Who would arm and, if he was opposed,

He on this, his foe on the farther side,

He’d ensure the narrow passage was closed,

For every knight that came there he defied,

And, upon the bridge, a duel he proposed,

While if their steed but swerved a foot aside,

They plunged to the water, wide and deep.

No greater peril than to seek that keep!

The Saracen, in his imagination,

Conceived that by oft tumbling to the flood,

Head-first, from the bridge to damnation,

Gulping the water, ere he could make good,

He might cleanse himself, by that oblation,

Of the fault wine had induced, if aught could,

As if, any more than wine, it might erase

The errors wine, in act or speech, displays.

On many a day, some knight would appear.

Oft he’d followed the road beside the main,

For none was more direct, running clear

Across that land, from Italy to Spain;

Or courage urged him on, or, as dear,

Honour, which he thus sought to maintain.

Yet all, who’d hoped to win, but met with strife,

And oft lost arms, and armour, and their life.

If they were Moors or Saracens, he acquired

Their arms, content to let the living go,

And of the best among them, whom he fired

From the bridge into the waters below,

He hung the arms, named (once he had enquired)

In the tomb; with Christians twas not so:

To Algiers were many sent, in his name,

Ere mad Orlando to the bridgehead came.

Canto XXIX: 40-43: Orlando appears and attempt to cross

The frenzied Count had reached the river,

Where, as might be witnessed, Rodomonte

Had completed his work, though the tower,

And the sepulchre, were not quite ready.

The bridge was scarce finished, moreover,

Yet, visor open, else armoured fully,

Rodomonte appeared, all set to fight,

As the Lord of Anglante came in sight.

As his madness dictated, Orlando

Leapt the barrier, and o’er the bridge did fly,

But Rodomonte, frowning at his foe,

As he stood by the tower, gave a cry

From afar yet full of menace, although,

Foregoing sword or spear, he let them lie.

‘Halt, villain,’ he called, ‘and curb your rashness;

Tis pride and arrogance fuel recklessness.

For lords and valiant knights that bridge was made,

Not for you, mad creature!’ Yet Orlando,

With mind distracted, but scant notice paid,

And deaf to every threat, onward did go.

‘This madman on the ground must be laid,’

Thought the Saracen, ‘or drowned there below!’

And drew nigh to despatch him to the river,

Not thinking some fell blow he might deliver.

Meanwhile a gentle lady reached the place,

Wishing to cross to the further shore,

Most richly arrayed, and most fair of face;

Reserved in mien, wisely herself she bore.

You may recall her, she whose steed did pace

The roads around, while ever searching for

Some trace of her beloved Brandimarte,

Except where he lay (in Paris seemingly!)

Canto XXIX: 44-47: Fiordelisa witnesses the fight

Fiordelisa came upon them, suddenly,

(For she it was, as you no doubt have guessed)

As Orlando grappled Rodomonte,

And sought to hurl him down, his mind oppressed,

Into the flood. His emblem she could see,

And recognised; his name she could attest,

Yet she wondered at the cause that had led

To his roaming here half-naked and, in dread,

She halted, that the end she might know

Of the fury with which this pair now fought.

For the one made every effort to throw

The other in the stream, and all for naught.

‘How can a fool such strength and prowess show?’

The Saracen cried, every sinew taut,

While shifting here and there, and back again,

Filled full with pride, and anger, and disdain.

He gripped with one hand, and then the other,

While seeking a fresh hold, as best he might,

And, with a leg twixt his foe’s, sought further

To throw him to the left, and then the right.

Rodomonte, clasping the Count tighter,

Mirrored the fierce bear that, with all its might,

Seeks to uproot the tree from which it fell,

Filled with anger, hatred, and guilt as well.

Orlando whose wits were lost (though where

I know not) and now used his strength alone,

That kind of strength in which few others share,

And seldom in this world is ever known,

Hurled himself from the bridge into the air,

Still clasping the Saracen’s flesh and bone.

They plunged into the river together,

And the bank groaned neath the weight of water.

Canto XXIX: 48-50: Of Orlando’s wanderings and feats

The current swiftly bore the pair apart.

Orlando, naked, swimming like a fish,

Flung his arms and legs about, with inborn art,

And gained the bank, nor sought to embellish

His victory, but on his way did start,

Careless of praise or blame, at the finish,

While the Saracen, impeded by his armour,

Reached the shore later, and with much labour.

Meanwhile, the fair Fiordelisa had crossed

The bridge, and thus had reached the further shore,

And then had searched for the one she’d lost,

Some trace of Brandimarte to secure,

But, finding not one sign, to her sad cost,

Still, in hope, turned to her long search once more;

While we turn to our tale of Orlando,

Who’d quit the tower, bridge, and river also.

Twere madness if I offered to relate

Orlando’s mad endeavours, one by one;

There were so many we’d be here till late,

And who knows when their tally would be done.

Yet some of his wild deeds I should narrate,

As seem pertinent here, rather than none;

Nor to tell of that wonder should refuse

Wrought in the Pyrenees, above Toulouse.

Canto XXIX: 51-56: He encounters two youths in the Pyrenees

The Count now wandered through the countryside,

Urged on by his wild and reckless frenzy,

And reached the top of that range, high and wide,

Twixt Tarragona and fair France, madly

Pursuing a straight course, to where he spied

The descending sun sink beyond a valley,

There he joined a path o’er the mountain steep,

Which hung above that vale both dark and deep.

He chanced to meet there, on the mountain track

Two bold young foresters that led a mule,

With a heavy load of wood on its back;

And since he had the semblance of a fool,

And his head every sign of sense did lack,

They shouted to the Count, in accents cruel,

To retreat, or stand aside, not block the path

Unless, indeed, he wished to feel their wrath.

To their threats, the Count answered not a word,

But kicked the mule, in the chest, violently,

Then stood his ground, as if he had not heard.

His strength, unparalleled, used furiously,

Sent it flying through the air like a bird,

The mule descending, less than gracefully,

To strike the mountainside above the track,

A mile beyond the vale, upon its back.

Then he turned on the youths, his ire increased.

One, with better luck than sense, made a leap

From the path, and fell sixty yards at least,

Such his fear, yet few injuries did reap.

For amid the brambles his speed decreased,

Since they were green, and prickly, damp and deep,

And while he was scratched, copiously,

He was rendered safe thus, and at liberty.

The other clung to an outcrop of stone,

Thinking he might regain the path once more,

And then, once among the cliffs swiftly flown,

Might well hide from the madman, he was sure.

But, once he’d climbed, with many a loud groan,

The Count grasped his feet, raised him from the floor,

Pulled his legs apart, and tore the lad in two,

Though, in his madness, scarce intending to,

Much as a falconer deals with a heron,

Or a chicken, whose entrails he removes,

To feed a merlin, or some other falcon,

With the offal that such a bird approves.

The other was all too happy to abandon

That place, and flee alive, as history proves,

For he told of it so oft (it ne’er grew stale)

Bishop Turpin heard it, and retold the tale.

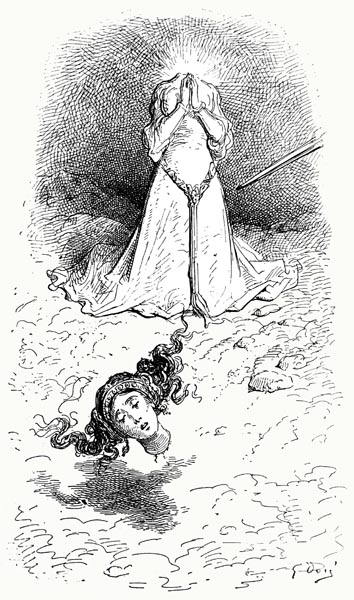

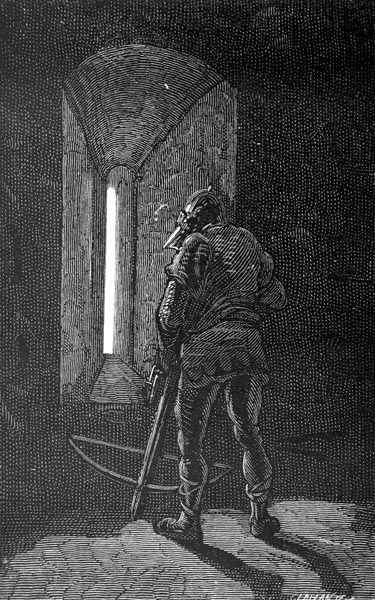

Canto XXIX: 57-63: Angelica and Medoro encounter him on the shore

Orlando wrought these and other marvels

As he strayed all about the mountain peak,

But, after many a wandering on his travels,

A path descending towards Spain did seek,

And roamed the coast, amidst the infidels,

By Tarragona, disinclined to speak,

Till driven, by his madness, as before,

He made his dwelling on the barren shore,

Where he countered the burning midday sun

By covering himself in powdery sand.

And such indeed was his situation,

When Angelica passed that lonely strand,

(With Medoro, as you know, for they’d won

Their way from the mountains to that land)

And had approached within a yard or so,

Before she’d realised it was Orlando.

But not the Orlando she remembered,

So altered from his former self was he.

The madness his wits had so encumbered

Naked in sun and shade, roaming free,

Had he midst Syene’s folk been numbered

Or where Ammon is worshipped endlessly,

Or midst the hills the Nile its way doth win,

He could ne’er have revealed a darker skin.

His eyes were well-nigh buried in his skull,

While his face was thin, and dry as a bone,

His hair was all dishevelled, long and dull,

Like his beard, vile, and sadly overgrown.

As soon as they were close, she, now fearful,

Drew backwards, all atremble, with a moan,

And shrieked aloud, at him, and as she cried

Turned about, for protection, to her guide.

Once he was aware of them, Orlando,

Leapt to his feet, to seize on one so fair,

So pleasing was her face to him, and so

Wildly his mad passions he must share.

And yet the maid he did no longer know.

His memory seeming lost beyond repair,

He ran behind her now, in such a manner

As a dog will pursue a hunted creature.

Medoro, seeing him chase his lady,

Drove his courser against him at full speed,

And struck at Orlando long, and fiercely,

When he turned his back, though he scarce gave heed.

He dealt him a blow on the head, sharply,

Though the skin was hard as bone, indeed

Harder than steel, for that same from birth,

Was rendered quite as hard as aught on earth.

The Count, feeling himself struck from behind,

Turned and, lunging at his youthful foe,

With a strength that few in the world can find,

Dealt the Saracen’s horse a mighty blow.

He broke its skull like glass, to death consigned

The creature, which slumped to the ground below,

While, in an instant, the Count turned, and sped

After Angelica who’d onwards fled.

Canto XXIX: 64-66: She employs the ring and vanishes

The lady drove her mare, and spurred her on;

The whip upon her flanks she did bestow,

And would have thought her too slow if she’d gone

As swiftly as an arrow from the bow.

Then the ring, she yet wore, she thought upon;

And set it twixt her lips, to scape the foe,

Then vanished (twas every bit as powerful)

As the light does when you snuff a candle.

Either from fear, or from her hand shaking

As she slipped the ring from her finger,

Or because the mare stumbled in fleeing,

(That may have been the cause, or another)

At the very moment when she was handling

The ring, and then vanished altogether,

One foot left the stirrup, all unplanned,

And she fell upon her back, on the sand.

If her leap had been two inches shorter,

She’s have ended in the madman’s embrace.

He would have slain her if he’d caught her,

But good fortune now had charge of her case.

Let her, by a second theft, gain another

Fair steed, as she did in that other place,

For she will ne’er regain this mare once more

That, pursued by Orlando, pounds the shore.

Canto XXIX: 67-71: Orlando pursues and seizes her mare

Doubt not that she must needs go find another,

While we’ll pursue the Count’s wild career,

Whose rage and fury were as great as ever,

Though she had sought the means to disappear.

Over the naked sand he chased the creature,

Drawing close to the mare till, looming near,

He touched her, and then grasped her by the mane,

And, at the end, held her fast by the rein.

He seized the palfrey with the same delight

As another might seize a fair maiden,

Dragged at the bit and bridle, held on tight,

Leapt to her back, then urged her on again.

Thus, the creature many a mile in flight,

Without repose, here and there, was driven,

Never rid of his weight in the saddle,

Nor allowed to run free of the bridle.

Meeting a ditch, and leaping over all,

She went head over heels with her rider;

He was unharmed, and never felt the fall,

But the mare landed hard on her shoulder.

From the depths, Orlando sought to haul

The winded steed, and in the end raised her

On his back, then climbed out, and thus he bore

Her along, for three bowshot-lengths or more.

Then, finding the beast was somewhat heavy,

He set her down, and led her by the rein,

While, lamed, the poor creature followed slowly.

‘Walk on!’ Orlando cried, but all in vain.

Though if she’d followed at a gallop, truly,

She’d still not have pleased a man insane.

So, he unloosed the halter from her head,

Then he tied it to her hind legs instead.

And thus, he dragged her all along the ground

So that she might follow, at her ease,

While she was scraped by the stones all around,

And hide and hair were reduced by degrees,

Till with constant wear and tear, ne’er unbound,

The beast died. One would think that he might cease

To drag the corpse, and yet he halted not

But pursued his way, the mare well-nigh forgot.

Canto XXIX: 72-74: Then continues on his mad way

Though the mare was dead, he dragged her yet,

Continuing his course, towards the west,

While some farmhouse or hamlet he’d beset

When in need of food or otherwise oppressed,

And using force on everyone he met,

Seizing bread and meat, leaving some distressed,

Beaten, crippled, and the rest as good as dead,

Halting but a moment, ere on he sped.

And he’d have done as much to the lady,

If she’d not used the ring and disappeared;

He knew not black from white in his folly,

And harmed, where he would not, all he neared.

A curse upon that same enchanted thing,

And he that gave it her, and interfered!

For, were if not for that ring, Orlando

Would have avenged a thousand lovers so;

And not slain her alone, but every other

That he might have laid his mad hands upon,

Of those at whose hands men must suffer,

And not an ounce of virtue in them, none!

But lest my notes now jar upon the hearer,

And sound discordantly before I’m done,

I’d best defer this to another time,

Lest the ladies find tedious this, my rhyme.

The End of Canto XXIX of ‘Orlando Furioso’