Ariosto: Orlando Furioso

Canto XVIII: Martano's Downfall

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2021, All Rights Reserved.

Illustrations photographed and digitally restored from the Fratelli Treves edition (Milan, 1899) by A. D. Kline.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose.

Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Canto XVIII: 1-3: Ariosto praises Ippolito’s careful judgement

- Canto XVIII: 4-7: Grifone runs amok among the townspeople

- Canto XVIII: 8-16: We return to Rodomonte under attack from Charlemagne

- Canto XVIII: 17-20: He breaks free from the square

- Canto XVIII: 21-25: And escapes down the Seine

- Canto XVIII: 26-31: Jealousy’s plot against Rodomonte

- Canto XVIII: 32-37: She rouses him to seek out Mandricardo

- Canto XVIII: 38-41: Meanwhile Charlemagne furthers the fight

- Canto XVIII: 42-58: The progress of the battle

- Canto XVIII: 59-69: We return to Grifone, and a repentant King Norandino

- Canto XVIII: 70-73: His brother, Aquilante, follows Grifone to Antioch

- Canto XVIII: 74-77: Aquilante encounters Martano near Mamuga

- Canto XVIII: 78-83: Martano attempts to deceive him

- Canto XVIII: 84-86: But his scheme is soon exposed

- Canto XVIII: 87-93: Aquilante finds his brother, and Martano is punished

- Canto XVIII: 94-98: Norandino announces a second tournament

- Canto XVIII: 99-103: Astolfo and Sansonetto meet the warrior-maid Marfisa

- Canto XVIII: 104-109: In the prize, Marfisa recognises her armour

- Canto XVIII: 110-113: And seizes it, causing turmoil

- Canto XVIII: 114-118: Grifone and Aquilante battle the newcomers

- Canto XVIII: 119-124: The warriors on both sides recognise each other

- Canto XVIII: 125-128: Marfisa explains the provenance of the armour

- Canto XVIII: 129-133: And ends by gifting it to Grifone

- Canto XVIII: 134-139: The five leave Syria for France, and visit Cyprus

- Canto XVIII: 140-145: They then meet with a storm at sea

- Canto XVIII: 146-154: We return to the siege, where Rinaldo slays Dardinello

- Canto XVIII: 155-164: The Moors retreat

- Canto XVIII: 165-171: Medoro decides to search for Dardinello’s corpse

- Canto XVIII: 172-181: He and Cloridano slay folk within the Christian camp

- Canto XVIII: 182-187: They retrieve Dardinello’s body

- Canto XVIII: 188-192: But are pursued by Zerbino’s men

Canto XVIII: 1-3: Ariosto praises Ippolito’s careful judgement

My most generous lord, Ippolito,

Your every deed I’ve rightly praised, and praise,

Though a large part of your glory, e’en so,

My harsh, unpolished style, e’er betrays.

One virtue more than any other, though

With heart and tongue, I applaud always:

All find a gracious audience in you,

Yet your judgement is ever wise and true.

Often, to shield some absent one from blame,

Sound reasons for their actions you’ll deduce;

Or wait to let them speak, in their own name,

With one ear open to detect abuse;

Thus, often, before dooming them to shame,

You’ll see them, seek a reasonable excuse,

Defer all for a day, month, year, merely,

To avoid your judging prematurely.

If King Norandino had done likewise,

Then he’d not have treated Grifone so.

Honour and profit accrue to the wise;

His name he darkened, while your fame will grow.

That fault his people came to realise,

For but ten cuts and thrusts, now sent below

Some thirty dead that lay about the cart,

Dispatched in anger, by his skill and art.

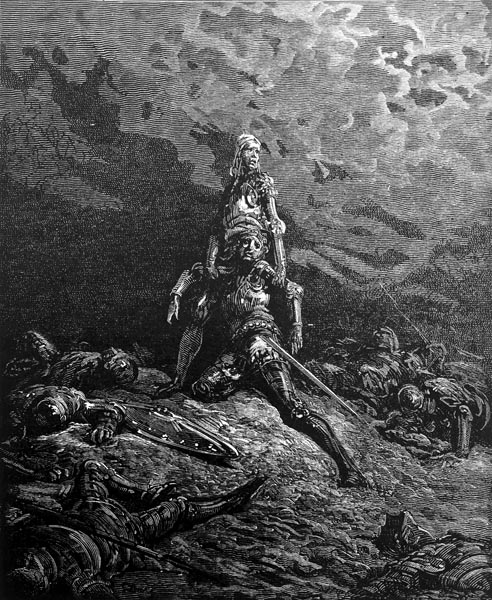

Canto XVIII: 4-7: Grifone runs amok among the townspeople

The others fled, wherever fear drove them,

Some here, some there, routed, o’er road and field,

While others ran for the walls behind them,

Though they were still forced, one by one, to yield.

Nor did Grifone, silent, threaten them,

Not a trace of pity for the mob revealed,

Rather he swung his blade, furiously,

Seeking true vengeance for their mockery.

Of those who first attained the city gate,

Those who had been the swiftest folk to flee,

A part, far more concerned with their own fate

Than their friends’, raised the drawbridge suddenly,

The others wailing, in a deathlike state,

Fled without looking back, through the city;

While wild cries, as they ran, high-pitched and loud,

Midst the noise of tumult, issued from the crowd.

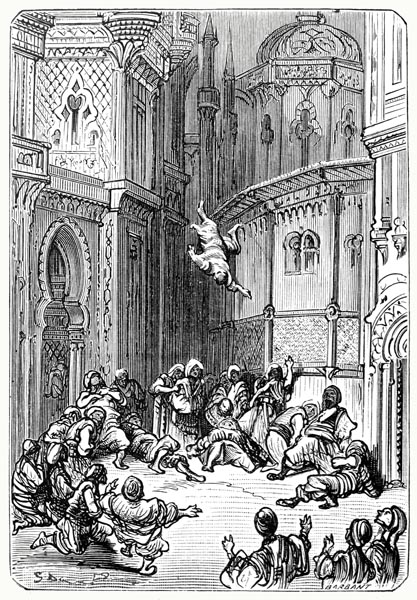

Grifone seized two, forcing them to yield,

For the drawbridge was raised, to their despair.

The first man’s brains he scattered o’er the field,

Striking him with a stone, gripping his hair;

The other’s chest he grasped, better to wield

Him and fling him, o’er the wall, through the air,

Chilling the bones of those who saw him fly,

And then descend, abruptly, from the sky.

Many there were who feared that Grifone

Would decide to leap o’er the battlement,

Nor would it have less appalled the many

If the Sultan had arrived, with dire intent

To assail the walls; their cries for mercy,

The muezzins’ calls, to the heavens lent

Their wailing tones, all mingled with the sound

Of trumpets, drums, those heavens to confound.

Canto XVIII: 8-16: We return to Rodomonte under attack from Charlemagne

But, at a later time, I shall explain

All that in Damascus then occurred;

For tis right that I follow Charlemagne,

Who sought out Rodomonte, as you’ve heard,

As the pagan dealt his folk grief and pain;

For the king had summoned, with a word,

Ugiero, Namus, Oliviero, Avino,

Avolio, Otone, and Berlingiero.

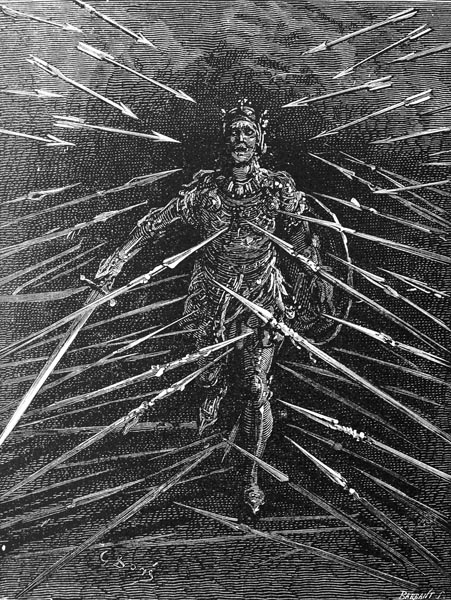

The shock of those eight lances, he defied

The Moor, though great the power of their attack,

As they struck upon the scaly serpent’s hide

With which their foe had clad his chest and back.

As a ship will right itself, and then will ride,

Through calmer water, with the ropes now slack,

The gale once past, so Rodomonte rose,

Though a hill they might have raised with their blows.

Ranier, Ricardo, Guido, Salamone,

Loyal Turpin, faithless Ganelon, as well,

Ughetto, Angioliero, Angiolino, Ivone,

Marco and Matteo, from the plain of Saint-Michel,

With the eight, that I spoke of formerly,

All attacked the Saracen, for a spell;

With Ariman and Edward of England,

Sent to aid Charlemagne, and now on hand.

Groans not so loud, upon its Alpine height,

Some mighty castle, founded on the rock,

When Boreas, or Eurus, rage, in flight,

And tear away the firs and ash, en bloc,

As did the Saracen, amidst that fight,

Filled with anger, and proud, as he took stock;

As thunder accompanies lightning’s fire,

So, in the wicked, vengeance joins with ire.

He struck the head of the nearest of all,

The luckless Ughetto of Dordona,

He cleft him to the teeth, and watched him fall,

Though his helm was of a goodly temper.

And then the rest he sought to strike and maul,

With sweeping blows at one, then another.

No more could they pierce his scaly hide

Than a needle can an anvil, though they tried.

The city and defences all around

Were deserted, all lay abandoned there,

For King Charlemagne had the trumpets sound,

And ordered all his soldiers to the square.

They ran to aid the eight, as they were bound,

And, in any case, flight proved a vain affair.

The presence of the monarch stirred each heart;

Their courage rose, as they rose to their part.

Just as, when, to the closely-barred steel cage,

Of a lioness accustomed to the fight,

A wild bull is introduced, filled with rage,

(Tis a contest in which the crowd delight!),

Her cubs will seek, amidst the sand, to gauge,

From its bellowing, the threat that it might

Represent, to those strange horns little used;

And watch, from afar, timid and confused,

Yet if their mother lunges at his ear

And fixes her great jaws on it, firmly,

Will sink their half-grown teeth, without fear,

In its flesh, and seek to aid her, boldly,

Biting the paunch, or back of that huge steer.

So, men now attacked the pagan, freely,

Leaping down upon him, from on high,

As a fierce storm, of weapons, they let fly.

The crowd of knights and men grew by degrees,

Such that the square could scarce contain them all,

They swarmed within it like a hive of bees,

Hastening to bring aid, from street and hall,

Who, if they’d been naked and unarmed, with ease,

Rodomonte might have reaped, and watched them fall,

More readily than scything stems of wheat,

Needing twenty days his harvest to complete.

Canto XVIII: 17-20: He breaks free from the square

The pagan, as the crowd about increased,

Found no means to escape the field of war;

Not an inch of space had the dead released,

Though he’d slain a thousand of them, and more.

But more came still, the number ne’er decreased,

Should he not seek his freedom now, he saw,

While his body was vigorous and sound,

He might not issue forth to win fresh ground.

Casting his fearful gaze about him, then,

He found that he was blocked at every turn,

But at the cost of slaying a tithe of men,

He might forge a way, and that freedom earn.

And, behold, swinging his great sword again,

The Fury led him where he could discern,

The English force, newcomers to that land,

Under Edward’s and Ariman’s command.

Whoever has seen a wild bull shatter

The wattle fence in a crowded square,

(Behind which the crowd stand and chatter),

When pricked and beaten more than it can bear,

And then, as they flee, chase down the latter,

And send a handful flying through the air,

Let them think the African, as he charged

Akin to such a creature, though enlarged.

He smote fifteen or twenty at a blow,

And likewise left each man without a head,

All with a single stroke, reversed or no,

Like to pruning vines, or a willow-bed.

Rank with their blood, he cut a path, and so

From that perilous place he safely sped,

Heads, arms, and other members, underfoot,

Shoulders, and thighs, marred at every cut.

Canto XVIII: 21-25: And escapes down the Seine

He retired from the square in such a way

None could see, in him, the least sign of fear,

While reflecting, as he kept his sword in play,

On how to issue forth, and disappear.

Thus, he came to where the Seine flowed away,

Below the isles, past the walls, tall and sheer.

Meanwhile the crowd of soldiers saw increase,

Pressing hard, so he might not go in peace.

As some great-hearted beast moves, in the chase,

Once roused, in the woods about Marseille,

Which, though fleeing, shows a heart never base,

But threatens harm, as it proudly makes its way

To its lair, he left, at a steady pace,

That strange forest of weapons still in play,

Formed of lance, and sword, and spear, and arrow,

And made for the Seine, his steps long and slow.

Three times or more, driven by his anger,

He turned upon the rabble at his back,

And stained his great sword with blood, as ever,

Slaying a hundred in each fierce attack.

But reason finally his rage did conquer;

Ere the heavens stank, he changed his tack.

Better judgement, in his peril, he applied,

And leapt into the Seine’s fast-flowing tide.

He swam with the current, in full armour,

And floated down until he made the shore.

Surely Africa ne’er saw one stronger,

Though Anteus and Hannibal it bore.

And, once there, he turned to gaze up-river,

To view the city he had left, once more,

Angered that he’d passed through it, entire,

And yet had failed to set the whole on fire.

For so stung was he by his wrath and pride,

He wished to turn, and enter in again,

From the depths of his heart, he groaned and sighed,

And would have tried to swim against the Seine;

But a form approached, along the river-side,

That did his rage and hatred now restrain.

Of who that person was, you’ll shortly hear,

But first another figure must appear.

Canto XVIII: 26-31: Jealousy’s plot against Rodomonte

For of haughty Discord I first must speak,

Who, by the Archangel Michael’s decree,

Was to rouse enmity, and quarrels seek,

Amongst King Agramante’s company.

She left Fraud to take her place midst the meek,

As she made her way from the monastery;

Fraud would maintain the war till her return,

And stoke the fires that ever there do burn.

And, she believed, if Pride accompanied her,

It would add another string to her bow,

And since she dwelt there, with the other,

She had only a little way to go.

Thus, Pride went too, yet taking care

To leave a vicar there; she did bestow

Hypocrisy upon the monastery,

While she was absent, however briefly.

Implacable Discord set out with Pride,

And discovered, as they made their journey,

That down that same road, with a dwarf for guide,

Went troubled, disconsolate Jealousy;

For off, to the Saracen camp, she hied,

The little dwarf keeping her company,

Who’d been sent by Doralice the Fair,

Bearing news, to King Rodomonte there.

When she was seized on by Mandricardo,

(I’ve told you, previously, how and where)

She’d, secretly, ordered the dwarf to go,

And find the king, and say how she did fare,

Hoping (once the dwarf had informed him so)

That, if for her fair self he yet did care,

Rodomonte should ride to her relief,

And wreak summary vengeance on the thief.

The dwarf had been observed by Jealousy,

Who’d learned his mission, beside the way,

And so made him join her on her journey,

While thinking she might have a role to play.

Jealousy encountered Discord gladly,

More pleased still when she chose to relay

The reason for her coming, which would be

Most helpful to her own small task, thought she.

She’d found the means to set Mandricardo,

And Rodomonte against each other.

She’d find further ways to rile the rest, though

This method seemed a perfect gift, to her.

She and the dwarf, thus, swiftly, did go

To where the king had made Paris suffer,

And shortly reached the river, and the strand

Upon which Rodomonte chose to land.

Canto XVIII: 32-37: She rouses him to seek out Mandricardo

As soon as Rodomonte recognised

His lovely lady’s little messenger,

His anger dwindled, calm was realised,

While he felt his courage burning brighter,

Happy of any news to be apprised,

Save that some outrage was done upon her.

He met the dwarf and asked him, cheerfully,

‘Whither go you, and how goes my lady?’

The little dwarf replied: ‘Nor yours nor mine,

But in thrall to another, is that lady;

For on the road, and not by our design,

We met a knight, who seized her.’ Jealousy

Now came and clasped the king, and sought to twine,

Cold as an asp, about him, silently.

Her messenger, continuing, confessed

How one man captured both, and slew the rest.

Discord at once took up her flint and steel,

And struck the one hard upon the other,

And, in an instant, he the fire could feel,

For, beneath it, Pride had spread the tinder,

Until his burning soul could not conceal

The conflagration, now sinking deeper.

Quivering, groaning, with a dreadful sigh,

He cursed the four elements, and the sky.

As a tigress who, descending in vain

To her empty den, pacing everywhere,

Realises that her cubs, to her pain,

Have been taken, feels her great anger flare,

So, on Rodomonte, rage and ire did gain.

Rivers, hills, night or day, were not his care,

Storm and distance would present scant delay,

As he strove to bring that bold thief to bay.

Raging, the Saracen turned, swiftly,

And called out to the dwarf: ‘Away now; go!’

Not waiting for a horse, or company,

Rodomonte set out, his pace not slow,

Much like a lizard in the heat, briefly

Seen, as crossing the path it doth show.

He lacked a horse, but would commandeer

One from the very first knight he came near.

Discord, who perceived his secret thought,

Glanced, smilingly, at Pride, and then she said

That she’d go seek the charger that he sought,

(For thus new grief and strife might be bred).

And she would clear the road that none be caught,

By the king, so he must mount on hers instead.

She knew just how that purpose to attain.

Yet I’ll leave her; to return to Charlemagne.

Canto XVIII: 38-41: Meanwhile Charlemagne furthers the fight

When, with the departure of the pagan,

The fire around the emperor died away,

He reformed the scattered ranks, there and then;

Part he sent where the weaker places lay,

The rest to thwart the Saracens again,

To halt them, and then keep his foes at bay,

Commanding that through every gate they pour,

Thay lay twixt Saint-Germain and Saint-Victor;

And decreed that, at the Saint-Marcel gate,

Beyond which lay a wide stretch of country,

The various troops should group, and wait,

To create one large, and mighty company.

Exhorting them their skills to demonstrate,

To kill and maim, so that in memory

They’d long survive and, heartening them so,

Had the trumpets the battle-signal blow.

Agramante had reclaimed his saddle,

Despite the efforts of his Christian foe,

And was now waging perilous battle,

Against fair Isabella’s Zerbino;

Lurcanio met Sobrino, as well,

While a troop had encountered Rinaldo,

With both Virtue and Fortune at his side;

That he charged, broke, and scattered far and wide.

While so the fighting stood, Charlemagne

Attacked the rear-guard of the enemy,

Where Marsilio, the flower of Spain,

Had halted, with all his vast company.

Towards them, the emperor set in train

A bold attack, foot flanked by cavalry,

With so great a sound of drum and trumpet,

It seemed the world echoed it, in concert.

Canto XVIII: 42-58: The progress of the battle

The ranks of the Saracens, commencing

To withdraw, now began to turn and flee,

And once broken, scattered, fast departing,

Nor could be restored to their company.

Falsiron and Grandonio, the king,

Yet stood fast, who’d met with greater misery,

And Balugante, and Serpentino,

And Ferrau who gave a mighty bellow:

‘Come comrades,’ he cried, ‘come, valiant men,

Stand firm now, brothers, and maintain your place.

Mere cobwebs will they spin, these Saracen,

If we but do our duty for a space.

Consider the great honour, there and then,

Lady Fortune will grant us, of her grace.

And, if we fail, the everlasting shame,

That will accrue to every single name.’

So saying, with a great lance in his hand,

He spurred his steed against Berlingiero,

Who on swift Argaliffa rode the land,

And shattered his steel vizor, at a blow.

Hurling him to the ground, soon unmanned;

Then he dealt with another eight or so,

At sword-point, while at every stroke he made

Another horseman fell beneath his blade.

Elsewhere Rinaldo had slain full many;

And more than I would care to speak of here,

Before him none could stand, the enemy

Were but blown away, scattering in fear.

Lurcanio, Zerbino, equally,

Did such deeds, as seldom meet the ear,

The latter, with a thrust, Balastro slew,

The first cleft Finaduro’s helm in two.

Balastro led the troops from Alzerbe,

Those previously ruled by Tardocco,

The other led those of the pagan army

From Zamor, and Safi, and Morocco.

‘Are there none,’ you ask, ‘midst the enemy,

That the true art of lance and sword can show?’

Indeed, step by step, I unfold my story,

And leave none behind worthy of glory.

Thus, I’ll praise that King of the Zumara,

And son of Almonte, Dardinello;

His steel brought Hubert of Milford lower,

Claude of the wood, Dulphin, and Elio,

And Anselm of Stamford, moreover,

Pinamont of London, and Raimondo;

All downed with the sword (though to warfare bred,

Full strong) two stunned, one wounded, and four dead.

And yet, despite the valour he revealed,

He could not force his men to stand and fight,

Facing our lesser numbers in the field,

Lesser, yet with many a worthy knight,

Men steady in the joust, nor prone to yield,

Long used to stout defence of what was right.

The noble Moors fled; those of Zumara,

The Canary Isles, Morocco, and Setta.

Yet those of Alzerbe fled the faster,

Whom Dardinello bravely tried to stay;

For he, with harsh words, now with prayer,

Sought to raise their courage to face the fray,

‘If Almonte,’ he cried, ‘was worthy ever

To live in your memory, then display

Your valour in the field, come, let me see,

If you’d leave his son, here, in jeopardy.

For Youth and Hope, I beg you, stand and fight,

Those things in which your trust you once did place;

Let not the seed of that courageous knight,

Be lost to Africa, and leave no trace.

If we band not together, joined in might,

If this land’s barred to us before our face,

A wall too high the hills will prove to be,

To seek return, a ditch too deep the sea.

Far better to die here, than seek mercy

From these base hounds, and grovel at their feet.

For vain is every other remedy.

Stand firm, dear friends, the worthless rabble meet.

No more lives than we, has this enemy,

One pair of hands, one flesh, one soul complete.’

So saying, that bold youth, rose up anew,

And, with his sword, the Earl of Huntley slew.

Almonte’s memory so roused their army,

That those men at the forefront of the rout,

Thought it better now to halt, and rally,

Than turn their backs; and gave a valiant shout.

William of Burnich (taller than any

Of his English comrades, without a doubt),

Dardinello downed, then he fell upon

And cleft the head of Cornwall’s Aramon.

Aramon toppled slowly to the ground,

As his brother ran to him, to grant him aid.

But Dardinello’s sword his shoulder found,

Cleft to the fork, by his descending blade.

Next Bogio of Vergalla’s unsound

Defence he penetrated, who betrayed

The promise to return he’d made his wife,

(Within six months, he’d sworn, upon his life).

A knight fought not far from Dardinello;

Lurcanio it was; but now he’d cleft

Dorchino’s throat, and the head of Gardo,

Down to the jaw, while from him fled, bereft

Of courage, his faltering pace too slow,

Altheus, whom Dardinello loved; he left

Altheus dead, striking him from behind,

Rendering him, thus, both dumb and blind.

Dardinello, to avenge him, seized a spear,

And, seeking to slay Lurcanio, swore,

By his Mahomet (if he would but hear),

To vow the spoils to the mosque, and far more.

He went raging, through the field, far and near,

Found him, and soon pierced him to the core,

Driving the spear through, from side to side;

Ordered his armour stripped, and on did ride.

No need to ask if Ariodante,

Lurcanio’s brother, now mourned his fall,

Who desired, with his own hand, and swiftly,

To send his slayer to Hell’s deepest hall,

Though he was barred from him, by not only

The pagans but the baptised, in that maul;

Yet sought revenge and, brandishing his blade,

Now here, now there, a passage-way he made.

He charged, and chased, and struck, all around,

At whoever blocked his course along the plain,

While Dardinello, eager to be found,

Knowing his wish, to fight with him was fain;

The two hosts yet contended, o’er that ground,

Thus, his efforts to meet him proved in vain.

If Christians slew Moors, no less the ranks

Were depleted of the English, Scots, and Franks.

Fortune thwarted the pair, all that long day,

Such that they could not meet, striving idly;

She kept one as a greater champion’s prey;

For rarely does man cheat his destiny.

Behold, Rinaldo turned his face that way,

So refuge was denied him, then, swiftly,

Launched his attack; Fortune played the guide,

To grant him honour; Dardinello died.

Canto XVIII: 59-69: We return to Grifone, and a repentant King Norandino

But enough, it seems to me, has been shown

Of those glorious events in the West.

Tis time to seek Grifone, and make known

How he, with anger burning in his breast,

Had that sorry crowd of rascals overthrown,

Of more than common cowardice possessed.

King Norandino hastened there, when he heard,

With a thousand soldiers, summoned at his word.

The king, with his court for company,

Seeing the people fly, on every side,

Rode up to the gate, with a small army,

And then ordered the portal opened wide.

Our Grifone meanwhile had forced to flee

All of the worthless crowd he had defied,

And donned the armour, they had scorned, once more,

For his defence (the same he’d worn before).

Near a temple, well-walled on every hand,

Encircled by a moat, both deep and broad,

Upon a little bridge, he took his stand,

That most ample protection did afford.

Behold, there advanced a threatening band

As, through the gate, the king’s brave force now poured.

Grifone, not retreating from his place,

Of fear or doubt, showed not the slightest trace.

Rather, when he saw the men approaching,

He advanced, in turn, and met them on the way,

And then his sword, in his two hands, grasping,

Made great slaughter, with a bold display.

Once more, his place on the bridge resuming,

He maintained his stand, and kept them at bay.

He issued forth, and then returned again,

Yet leaving, every time, some bloody stain.

Strokes before and behind he dealt; and threw

Foot-soldiers and horsemen to the ground;

While the fierce host, converging on him, grew,

Until he seemed, beneath the foe, near-drowned.

His concern was great as they waxed anew;

(He fears submergence, whom the waves surround).

With his left shoulder cut, hurt in the thigh,

Even his great powers seemed to fail, thereby.

And yet Valour, who often aids her own,

Brought Norandino to forgive the knight.

For the king amidst the tumult, was shown

The heaps of dead, that he had felled outright,

The wounds inflicted by one man alone,

Which, surely, had required brave Hector’s might;

All witness to the fact that he’d poured shame

On a warrior most worthy of that name.

And then, as he drew nearer, and could see,

More clearly, he who had so many slain,

Who’d raised a mound, amidst the enemy,

And darkened the moat with many a stain,

He thought of him who gainst all Tuscany,

Once held the bridge, Horatius, their bane.

In his honour, and to save men from this foe,

He recalled them; and willingly they did go.

And raising a hand, weapon-less and bare,

A most ancient sign of truce and of peace,

‘I know not,’ he said, ‘if greater grief I share

Or sense of guilt, but let this conflict cease;

Poor judgment have I shown in this affair,

Led by worse counsel; now I seek release

From error, for I’ve subjected the first

Of knights to what is owing to the worst.

And if the bitter injury and shame

That you have suffered here, through ignorance,

Might be cancelled by the honour and fame

You win here (that only serves to enhance

Your name) then aught else you’d seek to claim,

That’s within my scope and power to advance,

But say, so I might know what gifts are due,

Cities, forts, or gold, that would content you.

Full half of my fair kingdom ask of me,

And, from this day, that half you shall possess,

For not only of that you’ve proved worthy,

But that I grant my heart to you, no less.

And as a pledge of faith, here, openly,

Take my hand, a token of friendliness.’

So saying, from his steed he descended,

And his right hand to the knight extended,

Who, finding the king’s manner, thus, benign,

And that he came to clasp his neck also,

To its sheath his sharp blade did now consign,

With all his rancour, and, humbly, bowed low.

The king who of his two wounds saw the sign,

Stains of blood, asked a messenger to go

For his doctor; they bore him to the town,

Then, in the palace, gently laid him down.

Canto XVIII: 70-73: His brother, Aquilante, follows Grifone to Antioch

There, wounded, he remained for some few days,

Ere he could arm, and pursue his journey.

But let us leave our knight, and go our ways,

And turn to his brother Aquilante,

With Astolfo, in Palestine, always

Intent upon their search for Grifone,

Through Jerusalem, every monastery,

And many a place far from the city.

Neither could divine, one nor the other,

Where Grifone might have gone, or could be;

But they met with that Greek pilgrim brother,

Who, in conversation, chanced to make free

With Orrigille’s name; she her lover

Had gone to Antioch to meet, o’er the sea,

So, he said, which was where this lover dwelt:

He had kindled her love, or so she felt.

Aquilante asked the man if he’d told

Grifone of all this (indeed, he had)

And surmised the rest, for he knew of old

His brother’s mind, and that he, driven mad,

Would go seek her within that Arab hold,

Before the maiden to her sins might add,

And snatch her from the hands of her lover;

His swift vengeance remembered forever.

Aquilante was unhappy that his brother

Should go alone without him, so to do.

And quickly clad himself in his armour,

But asked Astolfo, first, if he’d pursue

All his business there, and cease to further

His voyage to fair France, before the two,

Returned from Antioch; then, from Jaffa,

He travelled by sea, as that seemed quicker.

Canto XVIII: 74-77: Aquilante encounters Martano near Mamuga

So fair was the south-easterly that blew,

And the sea so calm, that, on the third day,

He saw famous Tyre, and Saffeto too,

Passing, next, by Beirut, upon his way,

To Zibeletto (with, beyond their view,

Cyprus’ isle to larboard) where they lay,

Then Tripoli to Tartus, to Lizza,

And so, to Latakia’s safe harbour.

From there to the north-east the vessel steered,

The pilot at the helm, lightly, swiftly,

Until the wide Orontes’ mouth they neared,

Waited their moment, and entered neatly.

Next, in a trice a broad gangplank appeared,

And down it went his steed, and Aquilante,

Who, once ashore, made his way upriver,

Till to Antioch he came, armed, as ever.

There he made enquiry for Martano:

That he was gone to Damascus, he heard,

With Orrigille and the servants in tow,

To a tourney, decreed by royal word.

His fixed intent set him then to follow,

Certain that his brother thus had spurred

From Antioch, and so, that very day,

By land, not sea, southwards, he made his way.

To Lidia and Larissa, he did maintain

A course, then returned north, to Aleppo,

Where he rested a while. God next did show

That the good win mercy, the evil pain;

For, a league from Mamuga, Martano

Aquilante encountered, on the plain;

Martano, parading, on his journey,

Before his steed, the prize from the tourney.

Canto XVIII: 78-83: Martano attempts to deceive him

At first, he mistook him for his brother,

Since the armour and the coat that he wore

Deceived him; white as snow was the latter,

And twas brave Grifone’s gear that he bore,

And, with that ‘Oh!’ we joyfully utter,

In our delight, began to speak, before,

On coming nearer, his expression altered,

For, on finding the lover, he faltered.

He thought that Grifone must be dead,

Through his companion’s treachery.

‘Come, tell me, you,’ he cried, ‘that have been bred

A traitor and a thief, as I can see,

Where did you steal those arms? You, now seated

On my dear brother’s charger, knavishly.

Say if my brother is alive or no,

And then how you deprived him of them so?’

Orrigille, hearing him speak in anger,

Wheeled her palfrey about, prepared to fly;

But Aquilante, swift to restrain her,

Blocked her passage, in the blink of an eye.

Martano, at the threats of the brother,

Taken all unawares, seemed like to die;

He turned pale, and trembled like a leaf,

For he lacked a ready answer, our thief.

Aquilante cried out, fulminating;

At Martano’s throat he pointed his sword,

As he glared at Orrigille, swearing

He’d have both their heads, by the Lord,

If all the facts were slow in appearing;

Martano thought what tale he might afford

That would serve to lessen, in some manner,

His grave fault, and these words chose to utter:

‘Know sir,’ he replied, ‘this is my sister;

Of good, and virtuous, parents likewise born.

Yet treated shamefully by your brother,

Who therefore, of her good name has been shorn.

Troubled by her plight, I rode to free her,

Yet thinking that he’d but put me to scorn,

That most puissant knight, I wrought, astutely,

A scheme born of my ingenuity.

I planned, with her, who wished to return

To a far more honourable life, that she,

When Grifone to his chamber did turn,

Should steal away from him, all silently,

This she did; and lest Grifone should learn

Our route, and un-weave our web, readily,

We left him deprived of horse and armour,

And, as you can see, have travelled hither.’

Canto XVIII: 84-86: But his scheme is soon exposed

He might well have boasted of his cunning,

(Aquilante, no doubt, would have believed,

Since, but for the horse and such, his thieving

Had wrought no harm upon the well-deceived,

Or so he claimed) yet, by over-cooking

His tale, he found the thing most ill-received;

For it was well-wrought in every feature,

Except that he’d claimed her as his sister.

For Aquilante, in Antioch, had heard

She was his mistress, and so said many,

Whence, foaming at the mouth with every word,

He cried: False thief, tis all mendacity!’

While, upon him, such a blow he conferred,

Two teeth went vanishing throat-wards, swiftly.

Then, without resistance from Martano,

He tied his arms behind him, to his woe.

And then he did the same to Orrigille,

Though excuses enough the lady tried.

And then he dragged them both, willy-nilly,

To Damascus, through all that countryside,

And would have dragged the pair, most willingly,

Another million miles or so beside

Till he found his brother who, at leisure,

Might deal them vengeance, in equal measure.

Canto XVIII: 87-93: Aquilante finds his brother, and Martano is punished

Aquilante had their squires, steeds, and gear,

Returned, with him, to Damascus, where Fame,

On beating wings, had flown, both far and near,

Through the place, trumpeting Grifone’s name.

There, great and little knew, it would appear,

His skill with the lance, and his prior claim

Upon the tourney’s glory and the prize

His companion had stolen, with his lies.

Meanwhile, the populace reviled Martano,

And pointed him out to one another,

‘Is this not he,’ they cried, ‘that gigolo,

Who was praised for the deeds of the other?

And while the braver knight was sleeping, so

Shamefully his greater worth did smother?

And is she not that servant of the devil,

That betrays the good, and aids the evil?

And others said: ‘How well those two agree,

Marked with the self-same brand, and of one race.’

Some chased behind, others cursed them loudly,

And cried: ‘Hang, draw, and quarter them, apace!’

All gathered to view them, filled with fury,

Then ran before them to the market-place.

The news now reached the king, who prized it more

Than if he’d gained a realm on some far shore.

Just as he was, though lacking many a squire,

Behind, before, the king came forth to meet

This Aquilante, who revenge, entire,

Wrought for Grifone; and there, in the street,

He honoured him, and begged him to retire

To his palace (his manner gentle, sweet)

And, with his consent, saw the wretches well

Bestowed, deep in the darkest prison cell;

Next, conducting him to Grifone’s bed,

(From which, with his wounds, he’d not yet stirred),

Who, at his brother’s coming, waxed bright red,

Deducing that the whole sad tale he’d heard;

And when Aquilante his say had said,

Containing more than one reproachful word,

They decided what the punishment should be

For that pair, in their hands. Now, Aquilante,

And the monarch, thought they should undergo

A thousand torments, but our Grifone

Sought pardon for the pair of them, e’en so;

(He dared not seek it for the maiden only!)

And many an argument went to and fro.

He was answered, and they concurred swiftly:

Martano must the hangman’s whip endure,

Till no more than half an inch from Death’s door.

They bound him, but not midst grass and flowers,

And he was flogged, all the next long morning;

Orrigille, in one of those high towers,

Was imprisoned, till the fair Lucina’s coming,

To whose wise presence were reserved such powers

As might appertain to her sentencing.

Aquilante sampled, now, Damascus’ charms,

Till Grifone was sound, and might bear arms.

Canto XVIII: 94-98: Norandino announces a second tournament

King Norandino could not choose but be

Repentant now, regretting his error,

For he’d become more temperate, clearly,

After the harm he’d wrought, and far wiser;

Remorseful, for treating so wretchedly

One most worthy of reward and honour;

Such that the monarch pondered, day and night,

How the wrong he had done he might set right.

He decided, as the guilty party,

That, since he ought to grant the knight the prize

Which was stolen from him, through treachery,

Twere best done openly, before all eyes,

With such honours granted as royalty

Bestows upon a perfect knight; likewise

He was bound to hold another tourney,

In a month, and so informed the country.

For this he made solemn preparation,

As great as could be made by any king,

And Rumour echoed his proclamation,

Speeding through Syria, on beating wing,

Phoenicia, Palestine, each location,

Till in Astolfo’s ears the news did ring;

Both he and the viceroy, then agreed

That each must do there some glorious deed.

True histories have praised Sansonetto,

This viceroy, as a famous warrior;

Baptised, as I have said, by Orlando,

While Charlemagne had made him governor

Of the Holy Land. He, and Astolfo,

Now set out for the city that Rumour

Declared the venue and, on their journey,

Heard, everywhere, of the impending tourney.

By easy stages, these two made their way

Slowly and comfortably, so as to come

To Damascus, fresh, and ready for the fray,

On the day of the joust; and came upon

At a crossroads, in a knight’s full array,

And seeming like a knight in her person,

One who was in fact a warrior-maid,

Wondrously fierce in war, and unafraid.

Canto XVIII: 99-103: Astolfo and Sansonetto meet the warrior-maid Marfisa

Marfisa was this brave warrior’s name,

And of such valour that she’d fought Orlando,

Raising sweat on his brow, despite his fame,

And Rinaldo, Lord of Montalbano;

And now, armed fully night and day, she came

In search of some knight errant; high and low,

She sought, o’er hill and dale, in every town,

Hoping to win great glory and renown.

She saw Astolfo and Sansonetto,

Approaching her, slowly, clad in armour;

Each man as a seasoned knight did show,

Each a large-boned and doughty warrior,

And worthy of consideration so,

Against whom she might prove herself further.

And, viewing them closely, as they came near,

She found she recognised the English peer.

She remembered Astolfo with pleasure,

From the days when she’d known him in Cathay.

She called out his name and raised, thereafter,

Her visor, and towards him made her way,

Drew off her gauntlets, and clasped the warrior,

Though far prouder than many, I should say;

While, no less gladly on his part, the knight

Greeted the paladin with true delight.

They questioned each other on their journey,

And when Astolfo, who was first to reply,

Said he sought Damascus, where a tourney

Would be held by its monarch, by and by,

And, there, knights might display their chivalry,

Marfisa, who ever such things would try,

Witnessing to it, said, with firm intent,

‘I shall go with you, to this tournament.’

Astolfo was gratified that she would be

A comrade-in-arms, Sansonetto too.

They were there the day before the tourney,

And lodged outside the walls, until, anew,

Aurora should raise her old spouse, gently,

From his abiding slumber; there the two

Now rested, entertained at greater ease

Than in some great palace, where all must please.

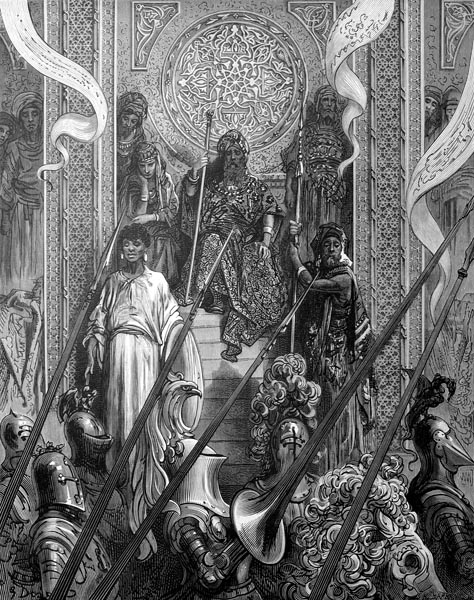

Canto XVIII: 104-109: In the prize, Marfisa recognises her armour

And when the morning sun shone clear and bright,

And everywhere had spread its fulgent ray,

The lovely lady armed, as did each knight,

Sending men to the city, to relay

News of all that appertained to the fight,

And tell them when the king arrived, that day,

To see strong lances broken, and delight

In this joust, held to judge their skill and might.

At the word, they swiftly made their way,

Down the main road, to the crowded square,

Where, awaiting the sign, in brave array,

Knights stood, of noble rank, ranged here and there.

The prizes to be given on that day,

Were a fine club and a mace, both rich and fair,

And, to accompany those arms, a steed,

Fit for a knight supreme in word and deed.

Norandino was convinced, in his heart,

That Grifone the White would, yet again,

Win the joust, and display his skilful art;

And, thus, a second prize was like to gain,

To match the first, and so sustain his part;

Nor to less reward should the knight attain,

In adding to the armour, in due course,

The mace, the club, and the noble horse.

The armour, that in the first joust was won

By Grifone, who’d overcome all there,

Which Martano had stolen (now undone),

By feigning to be him, in that affair,

The king had hung in view, for everyone

To contemplate, and admire, in the square,

While the club and mace, as he’d decreed,

Were fastened to the saddle of the steed.

He was denied the effect that he’d intended

By the noble-hearted warrior maid.

She with her companions had descended

To the square, and seen the arms, there, arrayed.

On viewing the armour, thus suspended,

She swiftly recognised what was displayed

As hers before, for which she yet did care,

As we ourselves do for things rich and rare;

Twas she who’d left the armour by the road;

She’d found its weight a great impediment

And from her shoulders she had slipped the load,

Upon Brunello’s capture then intent,

One worthy of the rope, though ill-bestowed

Were further words on such a story spent;

Enough that you’ve understood why, there,

Marfisa found her armour decked the square.

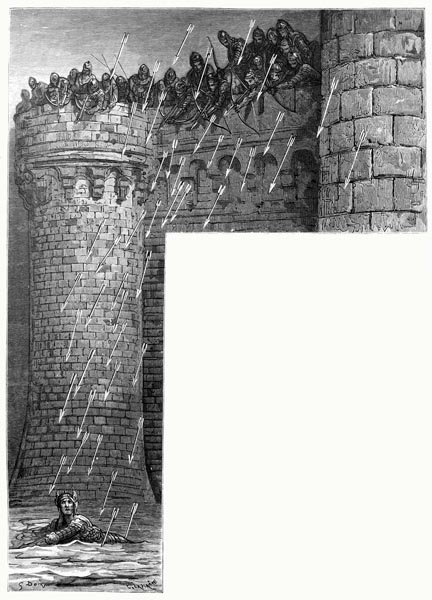

Canto XVIII: 110-113: And seizes it, causing turmoil

You’ll comprehend, again why, having seen

And recognised it, of a certainty,

She would not leave it (hanging there, I mean),

For aught in the world, e’en an hour; so, she

Not thinking of this mode or that, I ween,

To gain them, seized them, precipitously,

Riding closer, and stretching out her hand,

Till that armour, which was hers, she did command,

And because twas in haste she took the armour,

She dragged gear owned by others to the ground.

The Syrian king, offended, in his anger,

With a glance, summoned the guards around,

To avenge this misdeed by the warrior;

(A clash of weapons instantly did sound),

Forgetting that but a short day before,

He’d caused another brave knight wounds full sore.

No less glad than a child, in spring, playing,

Midst the flowers’ yellow, blue, red elegance;

Nor less willing than a maid obeying

A summons to the concert, or the dance,

Was she, midst true knights, engaged in slaying,

Midst the clatter, and clash, of sword and lance,

Where blood is shed, and cruel death draws near;

One, strong beyond belief, and free of fear.

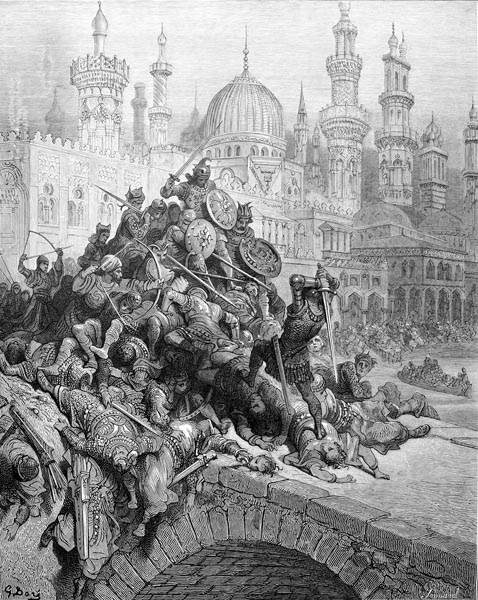

She spurred her steed, charged, impetuously,

With lowered lance against that foolish crew,

Piercing some chest or neck, most shrewdly,

And hurling to the ground more than a few;

Then with the sword-blade pressed others nearly,

And broke one head, and sliced another through;

Or smote a knight, and struck him in the flank,

As, lacking arm or leg, his neighbour sank.

Canto XVIII: 114-118: Grifone and Aquilante battle the newcomers

Nearby, Sansonetto and Astolfo,

Clad, like her, in their brave suits of armour,

(Intended for a different battle though)

Viewing the fight, did their visors lower,

And then their lances, and prepared to mow

A path through the hostile crowd before her;

Their sharp swords they unsheathed, and brought in play,

And swiftly, through the crowd, they carved a way.

The knights who’d come there from many a land,

That they might play their part in the tourney,

Seeing the turmoil rise, on every hand,

And pleasure turning to hostility

(Not knowing the reason, you understand,

For the fight, nor why the host were angry,

Nor why the monarch should seem offended)

In doubt and stupefaction were suspended.

Some chose to be with royalty allied,

Though they’d come to repent of it later;

Others, inclined to join neither side,

That of the natives, or of the stranger,

Sought to depart; while others did abide,

Reins warily in hand, seeming wiser,

To view the outcome; while Aquilante

Flew to exact vengeance, with Grifone.

Seeing the monarch’s eyes red with fury,

And learning of the reason for the fight,

From those who were about him, Grifone,

Thought it presented just as great a slight

To himself as to the king, an injury

That he needs counter with all his might,

And so, he and his brother did advance

And sought true vengeance with sword and lance.

Yet Astolfo spurred on Rabicano,

And encountered the brothers as they came,

His enchanted golden lance aimed at the foe,

Which had such power within it, that same,

That, at a touch, twould lay all-comers low.

To Grifone the weapon first laid claim,

Then Aquilante, who with shield in hand,

Barely struck, tumbled straightway to the sand.

Canto XVIII: 119-124: The warriors on both sides recognise each other

Meanwhile men of prowess and of might,

Fell before the lance of Sansonetto.

As the crowd fled from the square at the sight,

The king raged at the triumph of the foe.

Marfisa now possessing, as of right,

Her former armour, with the new also,

Seeing the soldiers, and the crowd fleeing,

Set out, as conqueror, for her lodging.

Likewise, Astolfo and Sansonetto

Were swift to follow her towards the gate,

(The fleeing throng, parting, so they might go);

The trio halted there, to contemplate

The victory, while the brothers, in their woe

At having been unseated, cursed their fate,

And heads bowed low in shame, dared not appear

Before the king, whose anger both did fear.

They seized the reins, and mounted, rather;

Then turned their steeds towards the enemy.

The king, with many a man, followed after,

Invoking death and vengeance, furiously.

The foolish crowd cried ‘On, on!’ with fervour,

Then stood, afar off, watching avidly.

Grifone now approached the drawbridge, where

The bold trio faced the advancing pair.

As he drew near, Astolfo recognised

Oliviero’s son, who, as he came,

Bore the arms he’d worn the day he’d devised

Orrilo’s death; his armour, steed, the same.

While he’d failed to note, he now realised,

Astolfo, in the square, to his great shame,

But knew him now; he greeted him warmly,

Then asked who his companions might be,

And why one of them had seized the armour,

And had shown the king scant reverence, thereby.

Grifone named the one, then the other,

But as to the armour he gave swift reply:

That he had no knowledge of the matter,

(In that, more ignorant than you and I)

But, as they’d come with the warrior-maid,

Sansonetto and he had lent their aid.

Meanwhile, as the two of them were talking,

Came Aquilante, who knew Astolfo,

And drawing near, on hearing them speaking,

Quenched that anger best reserved for the foe.

And then came a host of those belonging

To the number despatched by Norandino,

That, seeing them in conference, stood by,

Listening in silence, to who, what, and why.

Canto XVIII: 125-128: Marfisa explains the provenance of the armour

Yet, on hearing that Marfisa was there,

Known throughout the world for her bravery,

A guard turned back, to make the king aware

That if he would not lose his court, wholly,

He should swift withdraw from that affair,

Out the hands of Death, and Tisiphone;

For no thief, in the square, but Marfisa

Had seized upon, and removed the armour.

When Norandino heard that dreaded name,

For throughout the Levant she was feared,

(The hair bristled on men’s heads at that same,

Though she seldom in the kingdom appeared)

Knowing, where’er she went, ill often came,

Saw that he must act, ere disaster neared,

And ordered the guards, whose former ire

Had been replaced by fear, to swift retire.

For their part, the brothers, with Astolfo,

And Sansonetto, pleaded with Marfisa,

Till in the end she acquiesced, and so

The fight ended, yet not all the matter,

For she turned proudly to the king, to know

Why he would grant the armour as a prize,

When it was not his own, in any wise.

‘This is my armour; that I left, one day

By the road, that leads from Armenia,

Obliged there to pursue on foot, some way,

A thief who’d offended.’ said Marfisa,

‘My insignia the armour doth display,

Which you may witness, if you look closer.’

And there, clear upon the breastplate, did she

Reveal a crown imprinted, split in three.

Canto XVIII: 129-133: And ends by gifting it to Grifone

‘Tis true,’ replied the king, ‘of Armenia

Was the merchant, he who found the armour,

And if you had but asked me earlier,

You would have gained it, without bother,

For though I granted it to another,

I know so well this Grifone’s nature,

He’d have yielded it, most willingly,

That you might then receive the thing from me.

For you need do no more, to prove it yours;

The armour bears your own insignia.

Indeed, your word sufficed to gain your cause,

Weighing more than aught else might offer.

And, to yield it, but to Virtue restores

The prize, who is worthy of far greater.

Now take the thing, and let us not contend;

The knight, on me, may, for his due, depend.’

Grifone, who cared little for the armour,

Compared with contenting Norandino,

Said: ‘Sire, if I can but grant you pleasure,

Then all other gifts I’d gladly forego.’

To herself Marfisa said: ‘My honour

Is bound up with this.’ Kindly she did show;

Granting, our knight, the armour, courteously,

As a gift; which he accepted, finally.

To the city, they peacefully did go,

Where redoubled were the festivities;

Next came the tourney, where Sansonetto

Carried off the jousting prize, with ease;

For the brothers abstained, with Astolfo

And (the best of them) Marfisa, to please

Their companion and, in that way, devise

A means by which he’d likely gain the prize.

They dwelt there, feasting and celebrating,

Ten days or so, with King Norandino,

Until a strong desire for France, swelling

Within, that would not let them linger so,

Urged them to leave; Marfisa, deciding

To accompany them, when they chose to go,

For she wished to prove, with sword and lance,

Her skills against those of the knights of France.

Canto XVIII: 134-139: The five leave Syria for France, and visit Cyprus

She would seek by experience, to know

Whether their valour was as Rumour said.

Another deputised for Sansonetto,

And would rule Jerusalem in his stead;

Then, taking their leave of Norandino,

To the distant coast the company sped,

Five who few could equal for their skill,

Seeking a ship their mission to fulfil.

Once there, they found a carack set to load

Rich merchandise, returning to the West;

So, with its captain’s agreement, they stowed

Their steeds aboard, their armour, and the rest,

(He an old hand, from Luni); the sky showed

Fine and clear, and spoke of days fair and blessed.

They left the shore, the waves calm and serene,

As a following breeze bore them from the scene.

Cyprus, sacred isle of the Love-Goddess,

Breathed an air upon them, in its harbour,

That mars people, and rusts iron no less.

Life is but brief there; the marsh brings fever.

Nature, assuredly, has failed to bless

(Poisonous those vapours!) Famagusta,

Foul Costanza’s swamp acrid and malign,

Though the rest of Cyprus is so benign.

The noxious odours, rising from the fen,

Prevent any vessel lingering there.

With a north-north easterly, they sailed again,

Eastwards, round Cyprus, to Paphos the fair.

Anchoring, the knights and crew, as and when,

Disembarked, all the island’s joys to share,

The crew to trade, the rest, at their leisure,

To view Venus’ land of love and pleasure.

Some six or seven miles from the sea,

There rises, to the view, a pleasant hill.

The orange, myrtle, bay and cedar-tree,

And a thousand others its inclines fill;

Thyme, marjoram, the crocus, the lily,

From their scented leaves, such sweets distil,

That those who sail the sea, on every hand,

Know that fragrant breeze, flowing from the land.

A stream, from a limpid fount, runs around

All of that fair, and sweetly perfumed, space.

Truly, it may be said, that Venus found

For herself, a fine and delightful place.

For every woman bred upon that ground,

More than those born elsewhere, proves full of grace.

And Venus wills that they feel love’s ardour,

Young and old, all their life, near that harbour.

Canto XVIII: 140-145: They then meet with a storm at sea

There they heard the same tale of Lucina,

And of the Ogre, that they’d heard before

In Syria; and that, from Nicosia,

She was preparing to return once more,

To her lord. Their captain now raised anchor,

(For a fair wind rose, blowing from the shore)

And westward then he turned the vessel’s head;

Thus, they sailed on, with all their canvas spread.

Before that north wind, blowing from starboard,

The ship drove on awhile, when suddenly,

The wind changed, as the sun upwards soared,

To a soft breeze, a light south-westerly;

But by nightfall, as a strong gale, it roared,

Raising the waves mast-high, blowing fiercely,

With such loud thunder, lightning-bolts so dire,

It seemed the heavens, splitting, rained down fire.

A gloomy bank of cloud obscured the light,

So dense that neither sun nor star could show;

On every side, the wind raged all that night,

The heavens roared above, the sea below,

With icy rain that robbed the crew of sight,

And scourged them more, the harder it did blow,

While, as time passed, the darkness deepened further,

Over the fearful and angry water.

The master blew his whistle, and so taught

The sailors to apply their vaunted skill

To the sheets, those to starboard and to port;

While they bent to their labours with a will.

Some deployed the sea-anchor on its taut

Cable; some reefed the mainsail further still.

While these secured the tiller gainst the blast,

Those cleared the decks, and re-lashed the mast.

The cruel wind grew, in their vicinity,

The sky was denser, darker than in hell;

The captain stood his ship far out to sea,

Where a little less broken seemed the swell,

And steered to port or starboard, cautiously

Adjusting to the blasts, where’er they fell;

Never without hope that, come the morn,

The tempest would relent with the dawn.

The fierce wind neither dropped nor eased, but grew

In power, with the morning; if twas day,

For twas only from the hour that they knew

That dawn had come, and not by any ray

Of welcome light; with ebbing hope, the crew

Felt greater fear, as their captain gave way

To its violence, and ran before the gale,

Driven on, with the storm-jib for a sail.

Canto XVIII: 146-154: We return to the siege, where Rinaldo slays Dardinello

While Fortune so troubled those out at sea,

She granted little rest to those ashore,

Those in France, I mean, seeking victory,

The English, and the armies of the Moor.

There Rinaldo had charged all he could see,

Broke the ranks, overthrowing them, and tore

Their banners to the ground. On Bayard, lo,

He spurred next towards brave Dardinello.

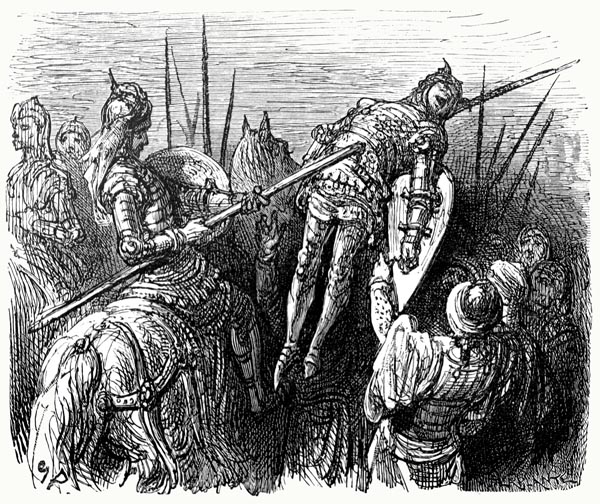

His quartered coat of arms Rinaldo spied,

Of which Almonte’s son was greatly proud;

And thought him bold and valiant, to ride

With that badge which had to Orlando bowed.

Approaching him, the thought was verified,

Viewing the slain he’d reft from out the crowd.

‘Better,’ he cried, ‘to crush this ill-got seed

Before it shoots and grows; be mine the deed!’

Wherever brave Rinaldo turns his gaze,

Those before him recoil, and so make space,

Both Christians and Saracens, always

Anxious lest Fusberta they must face,

Except this warrior, who boldly stays,

This Dardinello, bound for Death’s embrace.

‘Child, your father a fatal gift did yield

To his fond heir, in leaving you that shield;

For if you’ll await me,’ Rinaldo cried,

‘I’ll see how you defend the red and white

Of your shield; for if mine be not denied,

So much the less would be Orlando’s might.’

‘Now clearly comprehend,’ the king replied,

That what I bear I e’er defend in fight,

More honour I shall gain than blood now shed,

From my paternal quartering, white and red.

Though I am young, yet think not I will yield,

Or fly; no quarter shall you have from me.

Take now my life, if you can take my shield,

Though I hope, by God, for the contrary.

Yet, be that as it may, none in this field

Shall claim I ever shamed my ancestry.’

Thus speaking, sword in hand, Dardinello

Attacked the great Lord of Montalbano.

A chilling fear ran through the Moorish host,

As they gazed now upon Rinaldo’s face;

He charged towards their king, his glare almost

That of a lion (whose speed he would outpace)

Charging some bull, unable yet to boast

Of mounting a lady-love; thus, he did race.

The first blow to land was Dardinello’s,

Vainly, upon that helm once Mambrino’s.

Rinaldo smiled, and said: ‘I’d have you know,

That I am better skilled at drawing blood.’

He spurred on Bayard, and the reins let flow,

And thrust his blade, as a brave knight should,

With such force, against the breast of his foe,

That the veins spurted forth a mighty flood,

The breath emerging, as the lungs it found;

Cold and bloodied, the king fell to the ground.

As a crimson flower languishes and dies,

Caught by the plough’s sharp steel as it passed by,

Or as the dew-filled poppy droops, likewise,

And bows its head, so there, before the eye,

As the colour fled his face, in such sad guise,

Dardinello’s soul, from out the flesh, did fly;

He passed so from this life, and with him went

His strength, his courage, all his bold intent.

As water, trapped by human art and skill,

Is contained, and so blocked in its flowing,

Yet when the dam is broken, from the hill

Pours down, and fills the vale in its going,

With a mighty noise, so, without the will

Of their young king to prevent them fleeing,

His Africans ran here and there, dismayed,

On seeing him descend into Death’s shade.

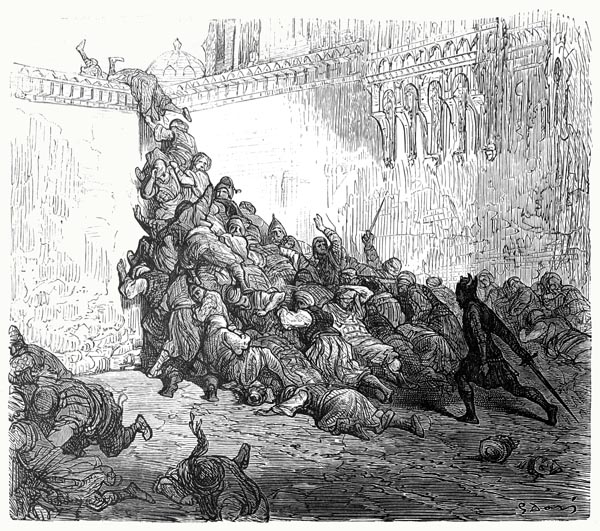

Canto XVIII: 155-164: The Moors retreat

Those who would fly, Rinaldo let them fly,

And waited to attack those who would stand;

Ariodante caused so many there to die,

Their counts of the slain went hand in hand.

Lionetto too, he approached them nigh,

And Zerbino who’d many there unmanned,

Charles discharged his role, and Oliviero,

Guido, Turpin, Salamone and Ugiero.

The Moors, on that day, were in grave danger

Of ne’er seeing their heathen shores again.

But the wise King of Spain brought together

All who were left, and then withdrew his men;

To avoid further losses seemed much better

Than to chance his all in that gambling den.

Far better to save the remnants, thereby

Than order them to stand their ground and die.

The banners went, with every fighting man,

To their camp, defended by ditch and wall;

With Andalusia’s king, and Stordilan,

And the Portuguese, obeying his call.

Then he sent to the King of Barbary

To retreat if he could, and scape the maul;

He that would earn no little praise that day,

Saving his army, leading them away.

For Barbary’s king, thinking himself wholly

Doomed to see Bizerte never more,

Since Fortune’s aspect never so grimly

Shown had that monarch witnessed e’er before,

Was cheered that Marsilio had swiftly

Retrieved part of the host, and was secure.

He faced the flags about and, to the beat

Of the recall, commenced a brave retreat.

Yet the best part of the scattered army

Had heard neither drum nor trumpet sound;

Some were confused, some simply cowardly,

But many a man in the Seine was drowned.

Sobrino accompanied Agramante

In scouring the squadrons that they found

For sound officers to gather in the men,

And retreat with them to the camp again.

But the King, Sobrino and their officers

Could save no more than a third of the host,

Despite their endless threats and menaces,

And rescue a third of the flags at most.

The rest had all relinquished their banners,

Were slaughtered, dying, or had fled their post.

Many had painful wounds, in front or back,

Wearied survivors of that fierce attack;

The Christians yet slew those who defied,

As to their camp the stragglers proceeded,

Which, in turn, was ill-suited to provide

Replenishment of all that they needed.

Charlemagne, with Fortune on his side,

Would have soldiered on till they’d conceded,

If the shadows of night had not descended,

Hampering all, and ensured the action ended;

Perchance twas the Creator hastened night,

Pitying the creatures He’d created,

For the blood ran in rivers, left and right,

And drenched all that soil, now desecrated.

Eighty thousand had been slain in the fight,

To a death by the lance or sword, thus fated.

From their dens came the wolves and scavengers,

Those nocturnal devourers and despoilers.

Charlemagne remained outside the city,

Pitching camp that night opposite the foe.

He besieged the quarters of the enemy,

And, about them all, his watchfires did glow,

While the pagans dug the earth, frantically,

Carved ditches, bastions, tunnelling below;

Then he stirred the guards, as he made his tour,

While, throughout that night, full armour he wore.

And, all that night, insecure, in their tents,

The Saracens lay, gloomy and oppressed,

Pouring out their tears, groans and laments,

Though, as best they could, such things they suppressed.

Some grieved at the result of past events,

Mourned kith and kin, others their wounds distressed,

Far more anxiety, as yet unsure

Of what dire ills their future held in store.

Canto XVIII: 165-171: Medoro decides to search for Dardinello’s corpse

Two Moors there were midst the pagan army,

In Ptolomita born, of stock base and low;

A rare example of true love, their story,

Their names Cloridano and Medoro;

For they had ever served, most faithfully,

And loved, their master Dardinello,

Whether Fortune smiled, or frowned uneasily;

And so had journeyed with him o’er the sea.

Cloridano was both nimble and strong,

All his life he’d been a follower of the chase;

Medoro’s snowy cheeks showed red among

The white, thus adding to his youthful grace.

And if the foe you’d searched, both wide and long,

Ne’er was a fairer or more joyful face.

His hair was crisp and golden, black his eyes,

A seeming angel sent down from the skies.

They were posted, with many another,

To defend the encampment overnight,

And gazed at the sky, or at each other,

With somnolent eyes, till it be light.

As they talked together, Medoro ever

Harped on memories of past delight,

And Dardinello, their lord; moreover,

That his corpse lay now bereft of honour.

And, turning to his friend, Medoro cried:

‘What deep and dreadful pain, Cloridano,

I suffer, knowing that he lies outside,

Upon the plain, a prey to wolf or crow.

Thinking how on his kindness I relied.

It seems to me a small thing to forego

My life, to honour him, in recompense,

In that my obligation seems immense.

So, he lacks not a burial, I must go

And seek for his poor corpse amidst the plain,

For God, perchance, will keep me hidden, so

None spy me from the camp of Charlemagne.

Stay here; and if my death be writ, also,

In heaven above, you shall here remain

And tell the tale, and though Fortune shuns me,

Fame will declare my heart true, and praise me.’

Cloridano, amazed that a mere youth

Should show such courage, and such loyalty,

Was yet, though loving him, inclined, in truth,

To curb the lad’s intent, yet fruitlessly;

He’d not be comforted, so great his ruth.

Intent upon his plan, absorbed wholly,

Medoro was disposed, indeed, to die,

Rather than leave the corpse there neath the sky.

On finding that naught could change his purpose.

Cloridano said: ‘Then, I shall go as well;

I too would seek a death as glorious,

I too would prove myself, like him that fell;

What would be left to me if, dying thus,

My Medoro amidst the shades did dwell?

To die with you, fighting, is far better

Than to die of grief, mourning you, later.’

Canto XVIII: 172-181: He and Cloridano slay folk within the Christian camp

Thus resolved, and leaving, in their stead,

Others to guard the camp, they went their way,

And, quitting the wall and ditch, quickly sped

Towards the Christian camp, with scant delay.

There men slumbered, free of care and dread;

Little fear of the Moors did they display,

Their fires quenched, midst carts and arms supine,

Drowned to the very eyes in sleep, and wine.

Here Cloridano paused awhile, then cried:

‘Why should we lose this opportunity?

Should we not draw vengeance to our side,

Medoro, and destroy the enemy

That slew our lord? Now, do you here abide,

Use your ears and eyes, and so support me.

For I offer to create, with my good sword,

A broad and spacious pathway through this horde.’

With this, he ceased speaking; then he came

To where the wise Alpheus lay asleep;

A physician, and a mage, was that same,

And in knowledge of astrology full deep.

To Charles’ court, the year before, seeking fame,

Had he come, yet all his skill failed to keep

Him alive; the death he’d foreseen, a lie,

That full of years, on his wife’s breast, he’d die.

For, swift, the Saracen, with silent blade,

Had cut his throat; and then four others too.

Not a sound or movement had they made,

As, beside the mage’s body, such he slew.

(Bishop Turpin their names perchance mislaid,

Or time had obscured those same from view)

Next Palidon of Moncalieri

That slept between two chargers, died swiftly.

Then Cloridano came to poor Grillo,

Who lay with his head propped on a barrel,

And, having drained it, had thought to follow

His draughts with peaceful sleep, free of quarrel.

The bold Saracen trimmed him neatly though,

(And from the severed neck there flowed a rill

Of wine amidst the blood, the cask empty)

While dreaming there, scorned by his enemy.

And near Grillo, a German and a Greek,

Their names were Conrad and Andropono,

Who’d passed part of the night there, cheek to cheek

O’er the flask and dice, he slew at a blow,

Happier if they’d lived the dawn to seek,

When the sun o’er India raised his glow;

But worthless all our dreams of destiny,

If mortals could their future end foresee.

Like to a famished lion, in a fold,

Whom hunger has rendered lean and spare,

Who bites, and devours both young and old,

Slaying the helpless creatures, everywhere,

So, the pagan slew all those in his hold,

For the dead there all fell to his share.

Medoro’s sword was just as sharp, I’d say,

Yet he disdained the baser crowd to slay,

And came to where the Duke of Labretto

Lay sleeping in his lady’s warm embrace;

Each there clasping the other tightly, so

Between the two was not the smallest space.

Both of them were slain, there, by Medoro;

Yet may God bless them with eternal grace,

For my belief is that with their bodies, lo,

Their souls embracing to their bourn did go.

Malindo, he slew then, and his brother

Andalico, the Count of Flanders’ sons,

Both newly knighted, one and the other.

Charlemagne had, for their escutcheons,

Granted them the lily, marks of honour;

For, amidst the brave, these were the ones

He’d noted; and he’d promised land also,

Denied to them, now, by this Medoro.

With their insidious blades, they drew close

To where the knights and lords, on the plain,

Guarded King Charles’ pavilion from his foes,

And yet the pair did not their path maintain.

Their impious slaughter ended, they chose

To sheathe their swords and withdraw again,

Thinking that, amidst those sleepers, one

Must be awake; and, thus, their work was done.

Canto XVIII: 182-187: They retrieve Dardinello’s body

For though they could have borne the spoils away,

They thought their own escape sufficient prize,

And so, by what he thought the safest way,

Went Cloridano, hidden from men’s eyes,

With Medoro behind, to where there lay,

Midst bows, shields, lances, swords, beneath the skies,

King and vassal, rich and poor, equally,

Men and their mounts, lost, for eternity.

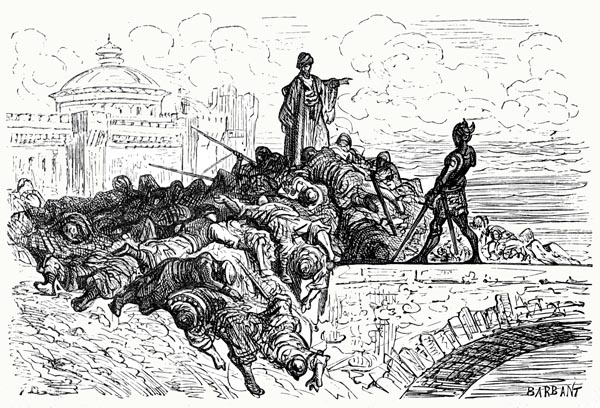

The dreadful mingling of the slaughtered, there,

That filled the blood-stained space, all around,

Might well have rendered vain the faithful care

The two gave to their search, o’er that ill ground,

Had not the Moon, at young Medoro’s prayer,

Emerged from out the clouds, and lit the mound

Of corpses; to her orb he turned his eyes,

And with devotion, spoke, and in this wise:

‘O sacred Goddess, whom the ancients knew

In triple form; you, whose sovereign beauty

Is revealed on earth, in hell, and heaven too,

In many shapes; who, neath the greenwood tree,

Many a beast and monster doth pursue,

Proving of the chase its immortal lady;

Show me where, midst these, my master lies,

That, once, your holy mysteries did prize.’

The Moon shone from the clouds at his prayer,

(Whether it was the work of faith or chance)

As lovely as when, all naked, to the fair

Endymion, she gave herself; while France

The hostile camps, and Paris, everywhere

Her light revealed, and every circumstance;

The gleaming hills, Montmartre on the right,

Montlhéry on the left, a distant sight.

The light was bright where Dardinello lay,

Greater the splendour o’er Almonte’s son.

Medoro went weeping neath that silver ray,

Knowing the white and the vermilion

Quartering of that shield, as though twere day;

And many a bitter tear he shed upon

His master’s corpse, and gave forth such sweet sighs,

Such sweet lament, as stilled the breeze, likewise,

But in so low a murmur none might hear.

Not that he cared if any heard him sigh,

If by so-doing it but brought death near,

Loathing his life, he wished that he might die;

That they might thwart his aim, his only fear,

That he might fail of his purpose, thereby.

The king they took upon their shoulders straight,

So, in that way, they might divide the weight.

Canto XVIII: 188-192: But are pursued by Zerbino’s men

They sought to move apace, as best they might,

Beneath the cherished burden they conveyed.

Now came the Sun, banishing, with his light,

The stars from heaven, and from earth the shade,

As Zerbino, who e’er rose to Virtue’s height

When needed, and on whom sleep scarcely weighed,

Having pursued the Moors all night, his way

Retraced now, at the coming of the day.

Some knights were there, that kept him company,

Who from afar the two companions saw,

And now, upon them, descended swiftly,

Hoping to gain, by that, the spoils of war.

‘Brother,’ cried Cloridano, ‘we must flee,

And drop this burden we can bear no more.

For foolish it would prove if, for one dead,

Two living men were to be lost, instead.’

He dropped the corpse, certain that his brother

Would do the same, on his part, but the lad,

Loving his master more than did the other,

Took up the task that formerly he’d had

While Cloridano hastened all the faster,

(Thinking him at his back still, I should add)

Who if he’d known he’d left him to his fate,

A thousand deaths had died, or soon, or late.

The knights, disposed to make the brothers yield,

And take them prisoner, or slay them there,

Some here, some there, had occupied the field,

And so, the two were hemmed in everywhere.

Their captain, riding with them, now revealed

His wish to end, at once, that whole affair;

For viewing their speed, that of hares almost,

He’d deemed they came from the enemy host.

There was, of old, an ancient wood nearby,

Dense thickets, floored with tangled undergrowth,

A labyrinth, to deceive the watching eye,

To enter which all but wild beasts were loath.

Here the brothers hoped, concealed, to lie;

Its depths, from their pursuers, hiding both.

Yet those who in my canto found delight,

Must wait to hear the rest, as is my right.