The Dual Realm

A Line-by-Line Commentary on Rilke’s Sonnets to Orpheus

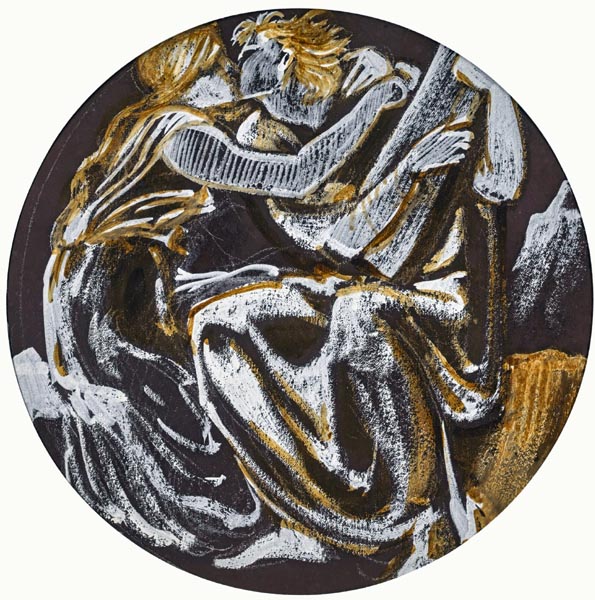

‘Orpheus’ - Gustave Moreau (French, 1826 - 1898), Artvee

Read A. S. Kline's English translation of Rilke's Sonnets to Orpheus.

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2023, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction

- The Myth of Orpheus, and the cult of Orphism

- Part I

- I, 1 (Da stieg ein Baum. O reine Übersteigung!)

- I, 2 (Und fast ein Mädchen wars und ging hervor)

- I, 3 (Ein Gott vermags. Wie aber, sag mir, soll)

- I, 4 (O ihr zärtlichen, tretet zuweilen)

- I, 5 (Errichtet keinen Denkstein. Laßt die Rose)

- I, 6 (Ist er ein Hiesiger? Nein, aus beiden)

- I, 7 (Rühmen, das ists! Ein zum Rühmen Bestellter)

- I, 8 (Nur im Raum der Rühmung darf die Klage)

- I, 9 (Nur wer die Leier schon hob)

- I, 10 (Euch, die ihr nie mein Gefühl verließt)

- I, 11 (Steh den Himmel. Heißt kein Sternbild ‘Reiter’?)

- I, 12 (Heil dem Geist, der uns verbinden mag)

- I, 13 (Voller Apfel, Birne und Banane)

- I, 14 (Wir gehen um mit Blume, Weinblatt, Frucht)

- I, 15 (Wartet..., das schmeckt... Schon ists auf der Flucht)

- I, 16 (Du, mein Freund, bist einsam, weil....)

- I, 17 (Zu unterst der Alte, verworrn)

- I, 18 (Hörst du das Neue, Herr)

- I, 19 (Wandelt sich rasch auch die Welt)

- I, 20 (Dir aber, Herr, o was weih ich dir, sag)

- I, 21 (Frühling ist wiedergekommen. Die Erde)

- I, 22 (Wir sind die Treibenden)

- I, 23 (O erst dann, wenn der Flug)

- I, 24 (Sollen wir unsere uralte Freundschaft, die großen)

- I, 25 (Dich aber will ich nun, Dich, die ich kannte)

- I, 26 (Du aber, Göttlicher, du, bis zuletzt noch Ertöner)

- Part II

- II, 1 (Atmen, du unsichtbares Gedicht!)

- II, 2 (So wie dem Meister manchmal das eilig)

- II, 3 (Spiegel noch nie hat man wissend beschrieben)

- II, 4 (O dieses ist das Tier, das es nicht giebt)

- II, 5 (Blumenmuskel, der der Anemone)

- II, 6 (Rose, du thronende, denen im Altertume)

- II, 7 (Blumen, ihr schließlich den ordnenden Händen verwandte)

- II, 8 (Wenige ihr, der einstigen Kindheit Gespielen)

- II, 9 (Rühmt euch, ihr Richtenden, nicht der entbehrlichen Folter)

- II, 10 (Alles Erworbne bedroht die Maschine, Solange)

- II, 11 (Manche, des Todes, entstand ruhig geordnete Regel)

- II, 12 (Wolle die Wandlung. O sei für die Flamme begeistert)

- II, 13 (Sei allem Abschied voran, als wäre er hinter)

- II, 14 (Siehe die Blumen, diese dem Irdischen treuen)

- II, 15 (O Brunnen-Mund, du gebender, du Mund)

- II, 16 (Immer wieder von uns aufgerissen)

- II, 17 (Wo, in welchen immer selig bewässerten Garten, an welchen)

- II, 18 (Tänzerin: o du Verlegung)

- II, 19 (Irgendwo wohnt das Gold in der verwöhnenden Bank)

- II, 20 (Zwischen den Sternen, wie weit; und doch, um)

- II, 21 (Singe die Gärten, mein Herz, die du nicht kennst; wie in Glas)

- II, 22 (O trotz Schicksal: die herrlichen Überflüsse)

- II, 23 (Rufe mich zu jener deiner Stunden)

- II, 24 (O diese Lust, immer neu, aus gelockertem Lehm!)

- II, 25 (Schon, horch, hörst du der ersten Harken)

- II, 26 (Wie ergreift uns der Vogelschrei...)

- II, 27 (Giebt es wirklich die Zeit, die zerstörende?)

- II, 28 (O komm und geh. Du, fast noch Kind, ergänze)

- II, 29 (Stiller Freund der vielen Fernen, fühle)

- Translator’s Concluding Remarks

- Index of First Lines

Translator’s Introduction

The following commentary on each of the sonnets is a companion piece to my commentary on the Duino Elegies (‘The Fountain of Joy’) which if read first will also help to illuminate the sonnets. Rilke, pursuing one of his most significant themes, the deeper integration of death with the claims of life, wove remembrance of the most significant deaths in his own life into the texture and contents of his poems. In particular he was deeply moved by the early death of his young cousin Egon von Rilke (1873-1880), that of the Expressionist painter Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907) who died shortly after giving birth to her daughter Mathilde, and that of the young dancer Wera Ouckama Knoop (1900-1919) a friend of his daughter. His correspondence with Wera’s mother, was renewed in 1921, and her sending him a book of notes Wera had written was one of the elements that inspired the composition of the sonnets. The set of sonnets was ‘written as a memorial’ to Wera, according to Rilke’s dedication of the published work.

Rilke created a framework for the series, by employing elements from the Greek myths, in particular the resonant cycle concerning Orpheus, the Thracian poet-musician, who visited the underworld (in the journey known as katabasis), and was torn to pieces by the followers of Dionysus. Rilke, who was ever-troubled by thoughts of transience and mortality, nonetheless seeks to stress a positive celebration and praise of life, both here and in the Duino Elegies. The difficulty in reading Rilke lies not so much in the complexity of his thought, and his occasional abstruseness, but in the reader’s reaction to Rilke’s view of the realm of death.

It is far from clear to what extent Rilke believed in his own imaginative realms, that of the Angels in the Duino Elegies (who, as he made clear, are not the angels of Christianity or Islam) or that of Orpheus (viewed as a god) in the sonnets. Equally disconcerting perhaps for many modern readers is his constant use of personification, anthropomorphism, and the pathetic fallacy, all means by which he tries to infuse more conscious life and purpose into the world than, from a scientific perspective, it contains. In doing so he simply continues an age-old poetic custom, but one that leaves him on the traditionalist side of his art rather than that of modernity, though intellectually he is a modernist in the sense of being an heir of nineteenth century existentialism (particularly that of Nietzsche and Kierkegaard) and later of post-World War I angst.

In reading the sonnets, it is for the reader to decide whether they believe in the external reality of a tangible or wholly spiritual realm of the dead, or whether to treat Rilke’s conception of it as an intellectual and emotional journey of the mind, a metaphorical invocation of the manner in which the fact of death and human mortality impinges on and influences our lives, through loss, grief, memory, and commemoration, and may lead to both anguish and inspiration. In either case, Rilke enriches our perceptions, and challenges us, in a profound and creative manner, to reflect on our own lives and on the human condition.

It is worth repeating Rilke’s own comments here. In a letter from 1923 he writes: ‘Whoever does not sometimes give full consent, and a joyous consent, to the dreadfulness of life, can never possess the unutterable richness and power of existence, can only walk at its edge, and one day, when judgement is given, will have been neither living nor dead. To show this identity of terror and bliss, these two faces of the same immortal head, indeed this single face…this is the true significance and purpose of the Elegies and the Sonnets to Orpheus.’

And previously in 1922 he had written ‘Here is the angel, who doesn’t exist, and the devil who doesn’t exist, and the human being who does exist stands between them, and (I can’t help saying it) their unreality makes him more real to me.’

Yet in 1925 he writes: ‘Death is the side of life turned away from us, un-illuminated by us: we must try to achieve the greatest possible consciousness of our existence, which is at home in both of these unlimited provinces, and inexhaustibly nourished by both…there is neither a here nor a beyond, but only the great unity, in which the Angels those beings that surpass us, are at home.’

Finally, consider this letter from 1923: ‘‘Death is not beyond our strength it is the measuring line on the vessel’s brim, and we read ‘full’ whenever we reach it….I am not saying we should love death, but we should love life so generously, so without calculation and discrimination, that we involuntarily come to include, and to love, death also (the half of life turned away from us)….because we have kept it a stranger it has become our enemy…it is a friend, our deepest friend…and that not in the...sense of life’s opposite a denial of life: but our friend precisely when we most passionately and vehemently assent to being here, living and working on Earth, to Nature and love. Life says simultaneously Yes and No. Death (I beg you to believe this!) is the true Yea-sayer. It says only Yes, in the presence of eternity.’

He employs, and toys with, metaphors to such an extent that he himself often seems to hold both the beliefs suggested above simultaneously. The shadow world is at one moment real, an afterlife of some kind, and at the next is a pure flight of the imagination. Orpheus is both a real external power and in the next instance a spiritual force engendered within the mind. It seems not to have mattered to Rilke, who perhaps saw any conflict amongst these ideas as a general expression of the indecisiveness of the species in regard to the subject, and ultimately irrelevant to the true tasks of seeing life and death as a single whole, of transforming the visible into the invisible within ourselves, and of celebrating and praising that whole.

Before commenting on each of the poems, a consideration of the myth of Orpheus and the associated cult of Orphism follows.

‘Orpheus and his Lute’ - Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones (English, 1833 – 1898), Artvee

The Myth of Orpheus, and the cult of Orphism

The best, most accessible, and most poetic retelling of the myth of Orpheus can be found in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, while Virgil also relates the story in Book IV of his Georgics. Ovid writes, at the start of Book X, of Orpheus’ descent into the underworld in a fruitless attempt to rescue his wife Eurydice, and at the start of Book XI of the death of the poet at the hands of the Maenads, or Bacchantes, the followers of the god Dionysus-Bacchus.

The first passage establishes Orpheus’ credentials as one who has passed through the realms of life and death, experiencing both our world and the mythological afterlife. This allows Rilke to absorb the Greek underworld, the realm ruled by Dis, and by the abducted Persephone, into his poetry, and therefore the region of the Shades, the disembodied spirits of the dead. The link to Persephone as a mode of the primal Goddess of pre-Greek thought, is important. As a goddess of vegetation and the cycle of the seasons, spending part of her time above the earth and part below it, Persephone is both a proponent of life and a ruler over the dead. Indeed, she is, in some respects, a more potent symbol of both than is Orpheus himself.

Orpheus however is, mythologically, the first human poet and player of the lyre, and an originator of poetic ‘song’ eclipsed only by the divine Apollo, the guardian of both. He therefore, in Rilke’s eyes, stands as the symbolic master of poets and poetry, referred to indeed as the lord or master in the sonnets, and treated there as himself a divinity. In descending into the underworld, he deliberately entered into the realm of death, as Rilke would have us do emotionally and intellectually. In pursuing the shade of a woman (Eurydice, fatally bitten in the heel by a viper) he echoes Rilke’s conjuring up of the shades of Wera and Paula, and in his failure (an error, a backward-glance, induced in the myth by an excess of longing) Orpheus perhaps reflects Rilke’s own sense of continual failure, but of renewed desire, to seamlessly join the twin realms of death and life, and make them one.

Orpheus, the son of the Muse Calliope, is blessed, through his powers of music and song, with the ability to draw wild creatures to him, and living trees, and even inanimate stones, almost granting the latter life. That kind of anthropomorphism is a fundamental part of Rilke’s poetic style. Orpheus’ song can manifest itself in the form of a lost girl, while Orpheus himself can act as the gatekeeper between worlds, always opening a path for others to follow, especially as concerns poetic effort, inasmuch as it seeks to enliven, celebrate and praise.

Orpheus, who can be seen as an adherent of Apollo the god of the lyre, and therefore of order, is here opposed mythically to Dionysus the god of chaos (an idea Nietzsche expounded in his first work ‘The Birth of Tragedy’). He is therefore attacked and destroyed, torn limb from limb, by the followers of that god (who is the Bacchus of the Romans), the Maenads or Bacchantes, a throng of frenzied women, whose song is the scream, and whose music is the ululation. His detached head floats down the river Hebrus to the sea still singing, and then to the island of Lesbos, where it gives out oracular utterances, in the manner of Bran in Celtic mythology. In this mode Orpheus, though dead, possesses a mental life beyond life, and is still enshrined in the mortal world. His lyre became the constellation of Lyra, and therefore both his singing prophetic head, represented by the poetic tradition, and his mode of musical expression, represented by the constellation, both still have a ‘living’ presence in the world.

Rilke also transfers to Orpheus some of Apollo’s attributes and powers, that of healing, for instance (Apollo both kills with his arrows and acts as a healer, brings disease and cures it, so unifying the two realms); of presiding over the ordered dance as an art-form; and of uttering prophetic truth, though sometimes ambiguously. These dimensions of Orpheus are explored, sometimes only touched on lightly, in the dance of the sonnets.

Orpheus was a key personage in the Ancient Greek and Hellenistic cult of Dionysus, known as Orphism, which celebrated the suffering and death of the infant Dionysus at the hands of the Titans, who were struck by Zeus’ thunderbolt in retribution, and turned to ashes. From the ashes, human beings took bodily form, the resurrected ‘twice-born’ Dionysus infusing them with spirit. The texts in which the cult originated were apparently attributed to Orpheus, hence the cult name of Orphism, and the corresponding Orphic rites. Those initiated into its mysteries underwent ritual purification, and relived the suffering and death of the god. Thereafter, they were granted an eternal life, while the uninitiated were subject to repeated reincarnation, as in the Hindu and Buddhist concept of samsara. The Orphic mysteries were a forerunner of the later Pythagorean cult involving the migration of souls into other forms of being (metempsychosis). Adherents of Orphism, like the Pythagoreans, refrained from eating meat, and lived an ascetic life.

Clearly the cults of Orpheus, Dionysus, and the related cult of Demeter the corn goddess and her daughter Persephone (presiding goddesses of the Eleusinian mysteries, in which Persephone was titled ‘the Maiden’) both derive from the ancient worship of a vegetation god who is a consort of the great goddess; he, ritually dismembered each year in the form of vegetation and the harvest (‘heads’ of corn); she, retiring beneath the ground to reappear again as the spring season. Thus, the cults reinforced the supreme value of life and transient living things, and the sanctity of the nurturing Earth, while at the same time recognising the realm of death. (For all of this see Frazer’s ‘The Golden Bough’, Campbell’s The Masks of God’, and many other texts). Rilke had here, personified by Orpheus-Dionysus, and by Persephone, the girl or maiden, the rich themes of the divine breathing spirit and life into the world, our human experience of death and the loss involved, as well as the resurrection and recurrence of life in the cycle of seasons, the sanctity of Nature, and the sources of both anxiety and inspiration that death and revival represent.

These elements individually are not, of course, unique to Orphism, but they do reinforce the structure and content of the sonnets, and allow, for the informed reader, mythological resonances and echoes to arise from Rilke’s work. For example, Zagreus, an incarnation of Dionysus, is, in myth, tricked by the Titans by means of a mirror prior to his dismemberment, and Rilke utilises the mirror theme in various poems. Again, Zagreus’ remains were gathered and interred by Apollo, God of the lyre, and healer, who in, later manifestations of the Orphic cult facilitated the resurrection of Dionysus, therefore restoring order after chaos, life after death, and joy after torment. The apparent conflict, which Nietzsche highlighted, between Apollo and Dionysus, chaos and order, can therefore be otherwise understood as a relationship, whereby the raw energy of Dionysus and the energy, captured in material forms, of Apollo, are complementary aspects of the creative whole. In one version of the rites, Apollo impregnates Semele, the mother of Dionysus, in order to achieve the latter’s rebirth and forge a unity, so that fertility and pregnancy can be incorporated into the thematic material of the sonnets.

It perhaps should be noted that Rilke turned to an ancient ‘dead’ religion, two ‘dead’ classical languages, and many a ‘dead’ poet, before invoking the living spirit, living language, and the living, perpetually-resurrected, art of poetry. From these mythical threads, and from much else, Rilke wove the tapestry of the sonnets. In the commentary that follows, the lines, in order, of the translated poems are shown in italics.

‘Eurydice Bitten by a Serpent’ - Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones (English, 1833 – 1898), Artvee

Part I

I, 1 (Da stieg ein Baum. O reine Übersteigung!)

A tree climbed there. O pure uprising!

Oh, Orpheus sang! O towering tree of hearing!

And all was still. Yet even in that hush

A new beginning, hint, and change, was there.

Rilke opens the sonnet sequence with a metaphor, a tree of hearing. Orpheus, master of the lyre, sang mythically; the poet Rilke sings in the present, pursuing the long tradition, and poetry (like all the arts) now offers an opportunity for one to settle and grant attention, to begin again, to transform oneself through inner awareness, a transformation of life Rilke advocated in the last line of an earlier poem ‘Archaic Torso of Apollo’. The beginning is an uprising, an upward and outward flow of song, the call to the perpetual novice to commence the process of initiation, which only the individual can pass through.

Creatures of silence pressed from the bright

Freed forest, out of nest and lair:

And they so yielded themselves, that not by a ruse,

And not out of fear, were they so quiet in themselves,

But simply through listening. Bellow, shriek, roar

Seemed small in their hearts.

Elements of the myth now come into play. Orpheus’ singing has the power to draw birds and wild creatures from their external silence and opaqueness, and that audience is ‘tamed’ and quietened not by means of trickery or through fear, but by yielding to the power of art, simply attending with full awareness to the external stimulus of song, until the harsher noises of the world, its cacophony of bellows, shrieks, and roars, seems less important than the silence of inner attention.

And where there was

Just barely a hut to receive it,

A refuge out of their darkest yearning,

With an entrance whose gate-posts trembled –

There you crafted a temple for their hearing.

Art, Rilke claims, has the power to provide not merely a simple and fragile (a trembling treescape) refuge for the mind and its emotions, a refuge, that is, for our longings, our yearning for permanence and not transience, for life and not death, for joy and not suffering, for peace and not violence, but also a temple of art and the spirit. The temple, which cannot be bought (See Pound’s Cantos: ‘The temple is not for sale’), and is a sanctuary for the spirit, a place for contemplation, regeneration, transformation, and celebration, is both ‘crafted’ in a creative act, and made more permanent through the artistic tradition; poetry and music originating here with the mythical Orpheus.

Rilke has therefore introduced a key theme, the power of the spirit, and in his case the artistic spirit, to enliven the world, and to praise it. At a deeper level he suggests that the transformation induced also comes from outside us, from the power of the divine or Nature’s power, from Orpheus their representative, and not simply from within the individual.

I, 2 (Und fast ein Mädchen wars und ging hervor)

And it was almost a girl, and she came out of

That single blessedness of song and lyre,

And shone clear through her springtime-veil

And made herself a bed inside my hearing.

Following on from the first sonnet, ‘it’ is the temple of art, which is ‘almost’ solid but not quite; ‘almost’ beyond the mind in its manifestations, Orpheus’ singing, Wera’s dancing or Paula’s paintings, yet only meaningful because of the mind. Or ‘it’ might also be construed as the flow of spiritual energy released by creative acts or external forces. Or as poetry, the performance that arises from the unified combination of song and lyre, of lyric and instrument, content and form. Like Persephone, the Maiden of the Eleusinian Mysteries, who returns to the surface of the Earth in springtime, the poetic sensibility as well as the renewal and revivification it brings, shines through its gleaming veil of form, and beds itself within the poet’s inner mind, their inner ear, and slumbers there as a constant presence.

And slept within me. And her sleep was all:

The trees, each that I admired, those

Perceptible distances, the meadows I felt,

And every wonder that concerned myself.

Rather than merely poetic sensibility or inner meaning we can read this invigorating spirit as energising the whole life of the mind and body, where mind is the singer and body the instrument. Orpheus then may be understood here as a personification of the power of an assumed universal spirit, of whom Persephone or Nature is a manifestation. And Orpheus’ power is also the potential, the reflective mind possesses, to embrace everything around it with wonder.

She slept the world. Singing god, how have you

So perfected her that she made no demand

To first be awake? See, she emerged and slept.

These manifestations of the spirit, our participation in Nature and our realisation of art, are potentials within us, slumbering powers, whom the girl, the maiden, Persephone, represents. She may also be interpreted in a traditional religious manner as the soul, the divine presence-within, the Shekinah of the Kabbalah who is the female aspect of the divine on earth. Rilke does not force a religious interpretation of the sonnets, but the spiritual power he indicates throughout certainly seems to have an external aspect within his world-view. In other words, the spirit is not merely an aspect of mind, of the workings of the brain created through evolution, but flows into the mind and the world from outside, in the manner in which traditional religion views the soul as awakened within the body by the divine. And the soul requires to be awakened, perfect though it may be at its inception, to fully live, since it does not demand to be awake, but merely ‘emerges’ and ‘sleeps’ until some moment of awakening.

Where is her death? O, will you still discover

This theme, before your song consumes itself? –

Where is she falling to, from me?... a girl, almost ...

How does or can the soul, then, die? This theme, of death joined with life, will this too be a theme of the sonnets, which will then not be merely a celebration of life, but an exploration of death also? The poet, Rilke, falters a moment. Expecting to use the sonnets, on the completion of the immense labour of creating the Duino Elegies, as a means for celebration, both of that poetic effort and life itself, must he now also take up again the theme incorporated in the Elegies, of the double realm of life and death? And if his poetic inspiration, which is consumed by the act of creation, is ebbing, is falling away from him, then Persephone is also Eurydice, inspiration, the wife of art, whom the viper (exhaustion, the mundane, the act of completion or consummation itself) bites and slays. Eurydice is she whom the poet must enter the underworld (the unconscious) once more, to find, in order that inspiration (literally ‘a breathing-in’) may reinvigorate him. The lost Eurydice may therefore personify not only Nature (with which we have almost lost, as contemporary human beings, a direct relationship), and artistic performance which has to be endlessly retrieved and recreated, but the soul and the spirit also, which can only be kept alive through endless effort and whose powers frequently sink exhausted, and require to be forever revived.

I, 3 (Ein Gott vermags. Wie aber, sag mir, soll)

A god can do so. But tell me how a man

Is supposed to follow, through the slender lyre?

His mind is riven. No temple of Apollo

Stands at the dual crossing of heart-roads.

The divine, as traditionally envisaged, can operate in both realms, that of the living and the dead. But how can a mere mortal by pursuing the vulnerable art of poetry (slender, slight, because it ultimately depends on inspiration and the mind alone, whether the mind of creator or reader) enter into the subject of death? The human mind is split, between the need to live fully, and the need to face death and suffering. And there is no temple of Apollo, no genuine external sanctuary for hearing (I think Rilke defies any formally religious interpretation of the sonnets here), for the human spirit, which always stands at the crossroads between the two worlds of the heart, between the living moment and the dead past, the pressing need to sing and the transient nature of the song, the urgency of the here and now and the silent ‘sleep’ of those no longer amongst us, the ‘greater majority’ of the Romans whom we must, in time, join.

Song, as you have taught it, is not desire,

Not a proclamation of final achievement:

Song is being. A simple thing for a god.

But when are we in being? And when does he

Turn the earth and stars towards us?

For the true poet, the ‘song’ of poetry, like the arts in general, is not finally about the longing to create, nor about our proclamation of having created the work, nor the achievement and perhaps fame that accompanies it, but about life itself, about engagement with the life of the universe, and with the inner mind; about, in a Taoist or Zen manner, simply living and being. Art is not merely a witness to life, but the cogent expression of it. Not a simple thing for a human being to achieve, though Orpheus the god might. And when do we achieve that state of authentic being, when does the god reveal the inner depths of the world to us, and our own inner depths? Is it when we are in love, in its broadest sense, when we are inspired by our wonder and respect and longing for the Other?

Young man, this is not your having loved, even if

Your voice forced open your mouth, then – learn

To forget that you sang out. It fades away.

To sing, in truth, is a different breath.

A breath of nothing. A gust within the god. A wind.

Rilke demurs somewhat. Having loved is not sufficient to join us to the universe, and even if we felt the compelling demand for utterance, love, creation, even if our own inner longing forced us to bear witness, to sing, we must accept that it fades away, that we are transient as the song is transient. That, in the end, we are as the song is, a breath of nothing, a disturbance of the air, that vanishes again. Ourselves the breeze and its passing.

I, 4 (O ihr zärtlichen, tretet zuweilen)

O you tender ones, sometimes progress

Deep inside the breath not meant for you,

Let it part before your face and, behind you,

Tremble, once more, as it flows together.

Rilke makes a plea to the sensitive, the spiritually aware mind. He asks it to enter the flow of the universe, the stream of Orphic singing, which is not intended for us. Scientifically, the universe is without intent, and we and the other sentient creatures are the only vehicles for purpose and intent, while, in a traditional religious reading, the divine intent is not directed specifically to the individual but has a greater existence beyond any one person.

O you blessed ones, O you healers,

Who seem to be, where the heart begins,

Arrows fired from the bow, and the target,

You whose smile ever shines through tears,

Don’t be afraid to suffer the heaviness,

Return its weight once more to the Earth;

Mountains are heavy, the seas are heavy.

By entering that flow, those who are blessed with sensitivity and Apollo’s power to heal the world (through art, performance, praise, courage, or in some other way), those who seem to be both the arrows of intense awareness fired from Apollo’s bow, and the target of them (the ‘heart-felt’ arrows that cause heightened perception or empathy, especially of both the need for celebration and the awareness of suffering), can, through taking upon themselves the burden of creation or healing, return significance and meaning, and purpose to mortal life, to the Earth itself, the heaviness of reality, its intellectual and emotional gravity. In the same way Zen points to the three modes of awareness of a mountain (or sea), firstly our everyday perception of it, secondly a deeper perception that understands its composition (to the atomic level), use as a symbol, geographic place, intellectual presence and more, until its covert meaning to us is exhausted, and thirdly the enlightened return to seeing and feeling all that, but expressed as awareness of its shimmering presence, its tangible and intangible reality, where it is once more simply a mountain, and yet not the same mountain in the mind. Such is the enlightenment true poetry can bring, the deeper resonance of being.

Even the trees you planted as children

Soon became too heavy. You cannot bear them,

But the air… but the space …

Even trees, other creatures, the things around us, soon become too heavy to those sensitive to the world and its suffering, as they mature. But the air and space into which we can project our spirits, the mental and spiritual existence we possess, that can liberate us, and that flow from Orpheus, from the spirit, can allow us to bear what may seem unbearable, and even sing of it (as Anna Akhmatova assured another patient sufferer she could do, even while standing in the queue before the prison gates, even in the depths of a hell created by human beings, see her poem sequence ‘Requiem’).

I, 5 (Errichtet keinen Denkstein. Laßt die Rose)

Raise no gravestone. Only let the rose

Bloom every year to favour him.

Since it is Orpheus. His metamorphosis

Into this and that. We need not strive

For other names. Once and for all

It is Orpheus, when he sings. He comes and goes.

Is it not much already that he, sometimes,

Stays, for a while, in the petal of the rose?

Though Orpheus was torn to pieces by the Maenads, though order is destroyed and we return to chaos, he is also a god of transformation, so we need not raise a gravestone for him, or mourn to excess. This transformation within, which Rilke stressed in the Duino Elegies, the need to take the things, the objects of this world, into ourselves, transform them and make them our own, is his care. Orpheus metamorphoses, into the form of the rose (which is also Persephone, or her manifestations in other modes of thought and religions, though ‘we need not strive for other names’ for the spirit, for life), the rose that flowers again, in the cycle of the seasons, and into many another living form. ‘Once and for all’, Orpheus represents life, and the life of the spirit, and Orpheus singing is a metaphor for the flow of life and spirit, which is transient. Life is transient. Artistic performance passes. But is it not already a great thing to receive and accept life, to feel life in the petal of the rose, or the human mind, or the poem as it is read, or the piece of music as it is performed, the dance as it is danced, the painting as it is created, all human achievement as it is played and replayed through our being in the world?

Oh, he must vanish, for you to understand!

And though he himself feared his vanishing,

Even as his word surpasses the being-here,

He is already there, where you cannot go.

The lyre-strings fail to constrain his hands.

And he responds, by his passing-beyond.

It is only by being aware of life’s transience (which creates the particular and peculiar weight that life possesses, its deep beauty, and the beauty of great art) that we can understand life, Rilke claims. Orpheus himself, the greatest of spirits, must also fear the spirit’s transience, must be aware of its repeated death and passing (transience is the death of every moment, and its rebirth in the next, not merely our termination in bodily death). But, despite that fear, Orpheus’ singing, the greater life of the spirit, transcends our mortal singing and existence (in the life of the species, or in religious interpretation as some other life of the spirit), and he has already passed to the realm of the dead where the living cannot go. He is not constrained by his role as singer and poet on Earth, he also passes beyond into the underworld (also therefore into the subconscious, the realm of remembrance, where the shades of the dead linger). He has the power of return, and must continually seek out Persephone in the depths, seek to rescue her, Eurydice, who is also Nature, and a reflection of his own soul and spirit, though he must continually fail in the attempt, as the poet must in the attempt to create the poem, through an excess of longing, and an incomplete awareness and retrieval of order, for which his ‘punishment’ is to die at the hands of Maenads, yet sing on prophetically as a disembodied mind, parted from non-sentient Nature (Eurydice is only partly-aware of what passes. Rilke portrays her here as slumbering initially, and likewise she is only half-aware of what passes in his earlier poem ‘Orpheus. Eurydice. Hermes.’)

I, 6 (Ist er ein Hiesiger? Nein, aus beiden)

Does he hail from here? No, from both

The realms his expansive nature grew.

Knower, bend the branches of willow

So, you may understand the willow roots.

Does Orpheus hail from this realm of the living? Rilke asks. And answers that the god is a dweller in both realms, of life and death. We must seek the roots of the willow, a tree associated with death and grief, especially in its weeping form, in order to understand the roots of life.

When you go to bed, leave on the table

Neither bread nor milk; they bring the dead;

But he, who is the Summoner, mingles

There, under the mild gentleness of eyelids,

Their apparitions with everything seen,

While the magic of rue and fumitory,

Is as true to him as the clearest relation.

Rilke enjoins against leaving the remnants of food and drink on the table because (so superstition claims) such things bring the ghosts of the dead; rather allow Orpheus, who is a Summoner (one who ‘endeavours to call up the spirits of the deceased’) to bring the apparitions of the dead to the sleeping mind, where they will be mingled with living memories of them. Orpheus is aware of the traditionally ‘magical’ value of mourning, as an agent of emotional healing. The role of grief (symbolised by rue) and tears (symbolized by fumitory, whose juice Pliny said caused weeping) is clear to him.

Nothing lessens a valid form for him.

Whether it be in the room, or the grave,

He praises the jug, the bracelet, the ring.

Every form of life is sacred to the god, and therefore every object which is associated with the living and which may subsequently adorn the grave, for example those found in ancient tombs, vessels and jewellery, is valid to him (the spirit of life) and not lessened by its use in either realm.

I, 7 (Rühmen, das ists! Ein zum Rühmen Bestellter)

Praising, that’s it! One appointed to praise,

He emerged like ore from the silent stone.

His heart, oh, the transient wine-press, among

Humankind, of an inexhaustible wine.

Rilke here speaks of Orpheus, but as a representative of poets in general, whose task in Rilke’s view is to praise (see his poem elsewhere entitled simply ‘Praise’). The living word emerges from the verbal silence of the inanimate world, like ore, perhaps the ore of gold, the raw material for transformation into usable metal, in this case into praise itself. The poet’s capability for feeling is like a wine-press extracting the juice of the grape harvest, from which an inexhaustible wine, language and poetic form, is produced.

When the divine mode grips him

The voice from his mouth never fails.

All becomes vineyard, all becomes grape,

Matured in his sentient south.

An inexhaustible wine because when seized by inspiration (in the mode of those who uttered the oracles of Apollo in ancient times) the poet continues the poetic tradition, the never-failing mouth, whereby the word is enlivened. For Rilke, Orpheus represents an even wider personification of the energised and energising spirit itself, which is immune to the reality of transience and death.

Neither the must in the tombs of the kings

Nor from the gods that a shadow falls,

Detracts at all from his praising.

That spirit perpetually praises life, despite the passing away of power, as evidenced by the tombs of dead rulers, and despite the presence of illness, poverty, plague, war, suffering, and death in the world, which things are collectively the shadow that the gods, according to Rilke here, allow to darken human existence.

He’s a messenger, who always remains,

Still holding, far through the doors of the dead,

A dish with fruit they can praise.

And so, the positive-minded poets fulfil the role, with Orpheus as their representative, of messengers who present in their work aspects of the world and of human life that are deserving of praise, including those memories and achievements of the dead that are deserving of respect and celebration.

I, 8 (Nur im Raum der Rühmung darf die Klage)

In the region of praise alone may Lament walk,

That Nymph of the weeping fountain,

Watching over what flows about us,

So, it may fall here, bright, on the stone

That supports the gates and the altar.

Using personification again as his literary method, Rilke posits that we only have the right to lament death where we also praise life as a whole, and that in that case lament (the utterance of true grief and mourning) is valid, and ensures that life incorporates praise of the dead, and purifies our attitude towards death as a natural and inevitable end to existence, or alternatively, as perhaps Rilke believed, a gateway to an afterlife of the spirit.

See, round her motionless shoulders,

Dawns the feeling that she is the youngest

Among her siblings here in the mind.

Jubilation knows, Longing confessed,

Only Lament’s still in the process of learning,

With childish hands counting her ancient woes.

Lament, personified, is motionless in the attitude of one with head lifted upwards, or bowed downwards in grief, absorbed in mind and memory rather than action. Jubilation is a mature celebration of life, Longing is a mode of thought we are accustomed to, but Lament, sorrow, true grief when encountered and experienced is always as if wholly new to us, an intense bolt of lightning that forces us to learn, or learn again, the painful pathways of loss. The experience then brings understanding of the ancient nature of loss, as undergone in the past, and by others, since time immemorial.

Then, suddenly, in the sky, awkward, unpractised,

She holds up our voices, a starry constellation,

A concatenation their breath yet fails to cloud.

In that process of mourning, that expression of grief, the personification of Lament may be seen as representing our individual sorrowing voices. Awkward and unpractised, because death and grief are always sudden and new when experienced, she offers up our acts of mourning, our cries of pain, to the heavens, as if they were a starry constellation whose chance concatenation of stars is not clouded by the breath of sorrow, but remains bright and alive in the face of transience and death.

I, 9 (Nur wer die Leier schon hob)

Only one who has raised the lyre,

Already, among the shades,

May sense how to return

The unending praise.

Rilke emphasises, once more, the nature of the double-realm of life and death. Only the person who has experienced the impact of a death, who has lived for a while among the memories, the shades of the departed, can sense the endless need for praise of life itself. An unending praise, repeated by many voices within the species, in the effort to assert the supreme value of being alive.

Only one who ate, with the dead,

Of the poppy, that is their own,

Will not lose the slightest

Note ever again.

Only those who have entered far enough into this understanding of the dual nature of human existence, where life and death are intertwined through memory, tradition, and history (or religiously, and superstitiously, in the presence of the spirits of the dead amongst the living) can hear the full music of being, and so will not fail to hear every note of that music, and recreate it in their work.

The poppy in Greek myth is associated with the goddess Demeter who ate poppies to help her sleep and forget her grief, after the abduction of her daughter Persephone. Poppies sprang from her footsteps, and Mecon her lover was transformed into the flower. The juice (ancient Greek, opós) of the opium poppy (papaver somniferum) was the source of the narcotic drug. According to Ovid, Demeter supplied Triptolemus with poppies in order to induce sleep. The poppy was adopted as one of the symbols of the goddess, and on a carved basket at Eleusis is portrayed in combination with ears of corn. As a symbol it is seen in the hands of statues of the divinities of the underworld, and because of the multiplicity of its seeds, was considered to be a symbol also of abundance and fertility.

Wish even the image in the pond

That blurs for us, often:

Know the reflection.

We should seek to perpetuate the memory of the dead, and review the images of them, though often elusive, which are reflections of our own image in the pool of the mind.

Only within the double sphere

Will the voices become

Kind, and eternal.

Because only by perceiving and appreciating the double-realm of life and death, will we experience the voices of the dead, for example through our memories or dreams, or the art of past, as positive, life-giving, and enduring.

I, 10 (Euch, die ihr nie mein Gefühl verließt)

To you, never lost from my feelings,

You ancient Sarcophagi, my greetings,

That the glittering water of Roman times

Flows through like a verse while walking,

Or that open wide, like the charmed eyes

Of some awakening shepherd in August –

Full of silence, and honeysuckle –

Out of which joyous butterflies go soaring.

Rilke turns to such examples of past art, the ancient sarcophagi (caved stone tombs, displayed above ground) which are now often deployed as stone basins for fountains (as, for instance, in Antonio Sarti’s 1842 fountain in the Via de Bocca Leone in Rome, where a Roman sarcophagus was redeployed) through which water now flows, like the verses of a poem created while walking ( like Dante’s ‘Commedia’ for example as he trod the pathways of Italy, in exile), or from whose empty, silent depths, now filled with honeysuckle, butterflies (traditional symbols of the soul) rise.

All those who are snatched from limbo,

I greet, all the newly-reopened mouths,

Who know now what true silence means.

Having used the analogy, for the wide-open tombs, of an awakening shepherd’s now-open eyes, Rilke expands on the analogy by greeting all those whose mouths were closed in sleep and which now open as they awake. Having been lost in the mute limbo of sleep, they now know what true silence means, the silence which surrounds the dead.

Are we certain, friends, or uncertain?

The juncture of both brings that doubt

Shown by the eyes in a human face.

Are we certain, asks Rilke of being awake, much like the Taoist Zhouang Zhou in Chinese legend who dreamt he was a butterfly, and subsequently was unsure whether he was Zhouang Zhou dreaming he was a butterfly or a butterfly dreaming he was Zhouang Zhou; are we certain, if religious, of there being an afterlife of the spirit? Rilke suggest that the expression of uncertainty on a waking face, or otherwise, results from our uncertainties concerning dream and reality, life and death.

I, 11 (Steh den Himmel. Heißt kein Sternbild ‘Reiter’?)

Halt the stars. Is there not one called the ‘Rider’?

That which is strangely imprinted within us,

The pride of the Earth? And then a second,

That he urges on and restrains, that bears him?

Rilke would like to explore that uncertainty. He notes the existence of a star called the ‘Rider’ (a word resonant for us, since we think, in our pride, that we are the summit of natural life, and by analogy the rider astride the Earth, the steed that bears us) and a second star that represents their mount. There are in fact two stars Mizar and Alcor its binary companion, in the constellation of the Plough (Ursa Major) situated in its ‘handle’, which in Arabic are also dubbed ‘the Rider, and the Horse’. A mutual urging-on and restraint is a good description of the motion of binary stars gravitationally bound to each other, and of the rider and their steed.

Is not the sinewy nature of Being pursued so,

And tamed? Turned to this side and that,

By merely the lightest of pressures,

Into a fresh tract of space. And the two are one.

Is not our pursuit of the nature of Being, and our effort to tame it, Rilke asks, like the rider directing their mount by the slight pressure of their body and limbs, guiding the mind into new regions of thought and analysis? So that Mind and Existence-in-the-world are one entity, a unity of spirit and matter, of internal and external reality.

Or are they? Do not either mean the path

That the two of them both travel together,

Still nameless, between ‘Table’ and ‘Field’.

Or should we rather regard the path of the rider and mount, mind and matter, as the combined and nameless Way (like the Tao) which the two separate entities travel (if mind can be considered an entity, rather than a complex process of the brain which is truly the entity here), in the region between the table (does Rilke intend other parts of the constellation Ursa Major here?) which holds the food that nurtures the human rider, and the field which the horse grazes, in other words between the pasture of the mind and that of the body.

Though a concatenation of stars deceives,

Yet we are happy to believe awhile

In its configuration. And that is enough.

Though a constellation, like Ursa Major, is merely a chance combination of visible stars, viewed by us as a unity, though those stars are in fact significantly distant from one another in space-time (though that is less true of the Mizar-Alcor binary) as long as we are prepared to believe even if only for a while in that illusory unity, that should be sufficient for us to dispel, for a while, our uncertainty about mind-body duality, and about the dual-realm.

I, 12 (Heil dem Geist, der uns verbinden mag)

Hail to the spirit, that holds us together,

Since we only exist by shape and form.

And in miniscule steps the clock ticks,

Set beside our actual day.

Having raised the question as to the unity of mind and matter, Rilke goes on to praise the mental reality (‘spirit’) by which both operate together to create our living selves, and the inner forces or powers which hold us together in a unique combined form. His approach is from the spiritual rather scientific direction, and in that he is a poet of his times, but the point is valid as a celebration and acknowledgement of the ‘miracle’ of Nature which is sentient being. Not only do we exist in measurable space, but in time (our measure of change) which ticks by at a different pace (an objectively steady pace to all strictly local clocks) to that of our subjective impressions, where moments or whole tracts of time may extend and contract, be recalled or forgotten, according to our mental state.

Without knowing our own true place,

We achieve real relationship;

The antennae feel the antennae,

And suffer the distance between…

Seemingly miraculously, we possess empathy, such that without fully understanding what we are and how we function in space and time, we can still achieve real relationship with each other through the antennae of emotion, through language, and in other ways, not excluding the purely physical, and with the world, through experience, knowledge and even emotionally through the pathetic fallacy, where we feel the presence of identity, personality etc. in other creatures, and in non-conscious, non-sentient things.

Pure tension! O music of forces!

Is it not through a venial struggle,

That disaster’s deflected from you?

Through, and not despite, the tension between horse and rider, mind and matter, internal and external reality, we achieve a unity, a musical harmony, of Being. The struggle, between these poles of the mental and the physical, is venial, an understandable and justifiable tension, through which we are able to unify ourselves (sufficiently) to avert the disaster which a sudden separation or rupture of mind and body, of horse and rider, of the internal and external, would represent.

Though the anxious farmer labours

So that the seed becomes harvest,

It is never enough. Earth must bear.

The anxious and uncertain individual, attempting to reconcile those tensions, is forced to struggle and labour like the farmer ploughing the ground, and sowing the seed, in order to achieve their spiritual harvest. Individual must transform themselves, become themselves, through significant effort, in order to achieve a high degree of unity and awareness. Nonetheless all that is not quite enough, we always need external help from Nature, from others, from the living and the dead.

I, 13 (Voller Apfel, Birne und Banane)

Fullness of apple, pear, blackcurrant,

Gooseberry…it all speaks life and death

In the mouth…I anticipate…

Go read it in some child’s face

As they taste it; it comes from afar. Are you

Slowly becoming nameless in your own mouth?

Rilke turns to an example of our awareness of the double realm. In the act of eating the fruits named (the translation substitutes blackcurrant here for the poetically unfortunate ‘banana’) the child tastes both ripeness and destruction, arrival and vanishing. The experience is deep, ‘from afar’, because it arises from the roots of our physical being, from the most ancient and primitive layers of sensation and consciousness. As adults, we eventually become fully aware of our own transience, of the process of losing identity in death, ‘becoming nameless’, and here in consuming the fruit we seem for an instant to meet with a lesser loss of identity in pure sensory perception, in the ecstatic process of tasting, as we may within the flow of any physical act, and therefore for a moment we become the species, its history, and its mortal reality.

Where there were words, find a flow,

Strangely surprised from the flesh.

That moment of pure sensation, beyond language, that flow, may feel strange as we allow language and reasoning to lapse for a time and the ‘flesh’, the body, to dictate our awareness.

Dare to say what an ‘apple’ is called,

This sweetness that deepens within,

Gently ripening in taste,

To become, clear, alive and transparent,

Ambiguous, sun-kissed, earthy, and here:

Oh, experience feeling. Infinite joy!

In the physical act we may re-establish the primitive meaning of the word ‘apple’, reconnect to its taste and form, in a sensory experience that almost seems a ‘thing’, and we feel joy in our own living presence, in the inwardness of the feeling, which also connects us more deeply to the outer world, though we remain ‘ambiguous’, creatures of body and mind, of the physical and the spiritual realms.

I, 14 (Wir gehen um mit Blume, Weinblatt, Frucht)

We’re involved with flower, vine-leaf and fruit.

They don’t only speak the language of seasons,

A vision of colour that rises from darkness,

Betraying perhaps the jealous glances

Of the dead themselves, who enrich the Earth.

We are involved with the whole life of the living vine (sacred to Dionysus-Bacchus) of Nature, from flower to fruit, and the vine does not merely reveal the passage of the seasons in its transformations, but it provides the wine that is laid down for many a year, the dark red vintage wine perhaps, the ultimate product of the dark soil, that rises from the wine-cellar, glimmers in the light, and Rilke suggests (half-seriously?) betrays in that perhaps the jealous glances of the dead, who are beneath the soil, enriching the Earth.

What do we know of her part in this?

It has long been her art to brand the clay

Freely, with her distinguishing mark.

Deep into his personification of the Earth, and thereby Nature, Rilke strays into imagining Earth herself setting her own distinguishing mark on the clay, which is the ancient clay of the wine-bottle’s seal, and the ‘clay’ of our own bodies. Her distinguishing mark is that of the dark Earth, the soil, whose part in the history of our species, and our continuing nurture, we ignore at our peril.

The question is: does it bring them pleasure?

Urging the fruit forth; labouring enslaved,

To enclose and offer it, to us their masters?

Are they the powers that sleep in the roots,

And indulge us simply out of abundance,

Something between mute effort and kisses?

Rilke then asks whether the buried dead derive some pleasure, in the vague afterlife he credits them with here, from their urging growth, stimulating the roots, and offering us the overflow of their abundance. Are they slumbering powers, forces, that bear fruit for us, the living? To apply the metaphor directly, and perhaps less fancifully, do the dead, as embodied in art and civilisation (in poetry for example) in the form of their surviving works and their place in our history, nourish the living arts, the present and future of our civilisation? Their abundance of spirit expressed itself in leaving behind something beyond themselves, for later generations to savour and take inspiration from. And those powers, that abundance, involved both the effort, now past and mute, expended in creating their still-living works, and the works themselves which are a loving embrace of life (the ‘kisses’) shared with the living, so that those works lie somewhere between the past silence and their present utterance. Equally our memories of the dead which lie ‘buried’ in our minds can invigorate and inspire us.

Note that the difference between assumed belief and metaphor in Rilke is often a deterrent to accepting his world-view, so it is always worth re-reading as metaphor what may be antipathetic when read as a direct statement concerning reality and belief. Are the Angels of the Elegies, for example, thought, by Rilke, to be real external entities, or are they an imaginative intellectual construct that helps to redefine the nature and situation of humankind? If the former deters the reader, the latter, the metaphor, may be more conducive.

I, 15 (Wartet..., das schmeckt... Schon ists auf der Flucht)

Wait…that taste…It’s already in flood…

A slight music only, a throbbing, a murmur.

You girls, you warm, you silent ones, dance

The dance of the fruit that’s tasted and known.

Rilke links the taste of the mature fruit to female ripeness (in a time when women were so often treated merely as vessels for sex and childbirth, a latent or active misogyny of the time that Rilke fails to fully escape, though he himself appreciated the artistic abilities of Wera and, especially, Paula). He exhorts young girls to the sexual ‘dance’ that results in pregnancy and childbirth.

Dance the orange; how could one forget

How, drowned in itself, it defends

Itself against its own sweetness; the fruit,

You possess, has been sweetly changed into you.

The pregnant woman, with her swollen belly, must to some extent defend herself from the demands of the foetus, from her own ripeness, until that fruit of coition becomes, within, a genetic image of the woman (and the man, therefore not identical to either but partaking of both). What is involved is a transformation, a process which Rilke sees as essential to all creatures that would fully participate in life.

Dance the orange. The warmer landscape,

Fling it from you, so that ripeness may glow

In your native air! Shining, unveiled.

Thus, the dance he advocates is that of the orange, which ‘defends’ its sweetness with its rind, as the pregnant woman also defends her foetus from damage by external forces, with her own swollen flesh. The unveiling that he suggests arises from, and prompts thoughts of, the Expressionist art of Paula Modersohn-Becker, one of the living though departed, shades in Rilke’s own life, whose ground-breaking portraits of herself nakedly pregnant were probably the first such in the pictorial art of her day.

Scent after scent. Create the connection

With the pure, the resisting rind,

With the juice that fills the fortunate mouth!

Create the connection, Rilke exhorts, between the form and the content, the rind and the juice in the mouth (‘fortunate’ because it carries the potential for connection), between the pregnant womb and the foetus within it, and between the body and the mind. Do so in poetry, scent by scent, line by line. In that art-form, create a connection between the tenuous creative inspiration, the ‘scent’ of the trail that leads to the finished poem, and the completed work. The association of pregnancy with creativity is hardly new; authors see their works as their progeny. Both the labour of childbirth and the labour of artistic production are seen as in some way akin. There is also implicit sexual imagery here. Nietzsche, Rilke’s contemporary, and a significant influence on his thought, claimed that our sexuality ‘reaches up into the ultimate pinnacle of the spirit’.

I, 16 (Du, mein Freund, bist einsam, weil....)

You, my friend, are lonely, because…

With our words, with our gestures,

We gradually make this world our own,

Our weakest, most perilous, perhaps.

After Paula, Rilke now thinks of a second friend of his, Franz Xaver Kappus, with whom he had corresponded (see ‘Letters to a Young Poet’). Kappus had sought advice and guidance, and Rilke had responded with his thoughts on poetic and personal development. Here he summarises. If one feels loneliness then that is because we have to gradually interpret the world to ourselves, in order to create ourselves and come to terms with reality, and so possess it. And often it is the words and gestures of ours that seem weakest and most dangerous that we must employ.

Who can gesture towards a scent?

And, of the many forces that threaten,

You feel a multitude. You know the dead,

And shudder at the spell that is cast.

Who, indeed, can easily invoke inspiration, the scent of creativity, that often seems to come to us from without, and not within? And his friend is sensitive to the multitude of inner and outer forces that threaten the mind, and self. The young poet, Kappus, is alive to the tradition, to that ‘communication of the dead’ which Eliot said ‘is tongued with fire beyond the language of the living’, and it can cause the heart to shudder at the message and the power with which it is delivered.

See, now is a time to endure the mass

Of bits and pieces as if they were whole.

To help would be hard. Do not, above all,

Plant me in your heart, I’m growing too swiftly.

As in the letters to Kappus, Rilke recommends that one suffers the fragmentation of life, as if one were whole, in the hopes of achieving true wholeness later. For someone outside the self to assist in the process of development is difficult, and Rilke advised Kappus, as here he advises his readers, not to follow his own path of development too closely, because he is developing in his own way too swiftly for that to be meaningful.

Yet I will guide my master’s hand to say,

Here, now. Here is Esau in his own pelt.

Nonetheless he will guide Orpheus’ hand, through his own, to write that here and now, that is in every moment of existence, one is born or reborn in one’s own skin, as Rilke himself can be seen to be still developing his thought within the text of the Sonnets. According to the Christian Bible Esau, son of Isaac, was born with hair on his body like a full-grown man. He can therefore stand for the physical, the body, though later Hebrew texts also associate him with spiritual power.

I, 17 (Zu unterst der Alte, verworrn)

In the depths, ancient tangle,

The mass of old roots,

The hidden source,

That is never seen.

In the depths of the poetic tradition, in our history as a species, that ‘tangle’ of events, inventions, and intellectual and ethical advances, lies the invisible source of our creativity, the spiritual power that is symbolised in the mythical person of Orpheus.

Spiked helms and hunting horns,

Speaking of greyness,

Men in fraternal rage,

Women like lutes…

Contemplating the roots of a tree (the willow of sonnet I.6?) Rilke sees, fancifully, the shapes of ancient helmets, and hunting horns, the ‘grey’ forms, that are banal and dark, forms of male aggression, and also the lute shapes of pregnant women, both sexes being assigned their traditional social roles.

Branch thrusting at branches

None of them free… one there!

Oh climb…Oh climb…

He views society and history, as one well might, as an endless realm of conflict, none of its participants free to develop and become themselves, except perhaps for the odd one here or there, poets in particular, since poetry is one of the most ancient of the arts. He breathlessly exhorts those individuals to climb.

Though they are broken still,

Yet the one there, on high,

Bends to a lyre.

Though as individuals they and we may perish, yet a few achieve, and behold, there is always Orpheus, on high, bringing music out of the strings of the lyre.

I, 18 (Hörst du das Neue, Herr)

Do you hear the new, Master,

Roaring and trembling?

The harbingers, heralds, come

That proclaim it.

Developing his critique of a social world that constrains and imprisons the individual, Rilke turns his attention to the contemporary age of the machine, which is filled with the roar and trembling of engines. Though he saw the twentieth century technological revolution in its early days, those machines already present were, he felt, the ‘shapes of things to come’, their harbingers and heralds.

True no hearing is whole

Amidst this raging,

But the machine demands

That its role be praised.

Indulging in pathetic fallacy, Rilke seemingly endows inanimate machines with will and intent. As a literary trope it is traditional to ascribe sentience to non-sentient things, but may well be a weakness here. Despite the noise machines make, says the poet, the machine still ‘demands’ that its role be praised and thereby its ‘voice’ heard.

See, how the machine heaves

And takes its revenge,

Distorting and weakening us.

Gaining its strength from us,

He asks us to observe how the machine, seemingly imbued with ‘life’, moves energetically, and takes its revenge on us (though it is not clear why there is a need or motive for revenge here, other than perhaps the revenge of the servant on the oppressive master). Rilke sees the machine age as distorting and weakening human nature, without his specifying in what manner it does so.

Let it, without passion,

Urge us onward, and serve.

Finally, he wishes the machine to be set in its place, as an emotionless servant, and a means of supporting us, which also ‘urges’ us onward as a species.

I, 19 (Wandelt sich rasch auch die Welt)

Though the world alters swiftly

Like patterns of cloud,

All that’s perfected

Returns to its ancient place.,

After his brief (and poetically and intellectually not wholly successful) skirmish with technological advance in sonnet I.18, Rilke returns to his main theme, and asserts that despite the pace of change, perfected things remain or return to their proper place. He is presumably thinking here of enduring artistic works, including architecture; of ethical and other values, for example the rule of law; besides like expressions of lasting human achievement.

Beyond the change and departure,

Further away, and freer,

Your prelude still endures

God of the lyre.

Accordingly, he asserts that Orpheus, as the elevated human spirit, exists in a realm beyond superficial change, and less constrained by the path of the species. Orpheus’ music, of the spirit, permanently endures.

Suffering is not grasped,

Love is not learned,

Nor is that which takes us far-off

In death ever unveiled.

Unlike Orpheus, human beings forever fail to comprehend loss and suffering, or learn from their experience of love, or gain any communicable view of the reality of death and the existence, or not, of an afterlife.

The song alone, over the earth,

Celebrates, sanctifies.

The song of the spirit, of Orpheus, alone celebrates, sanctifies and praises.

I, 20 (Dir aber, Herr, o was weih ich dir, sag)

But to you, Master, what shall I dedicate

To you, who taught creatures to listen? –

A memory of a spring day,

Its evening, in Russia – a horse,

From the village, a white horse came,

Alone, a rope at his forefoot,

To be fettered alone in the meadow,

All night – how his full mane shook

Over his neck, in tune with his spirits.

Having dwelt on the need to praise and celebrate, Rilke searches for something that inspires both, some offering that he can dedicate to the god. He settles on a memory from his time in Russia. He was there, and in the Ukraine, in 1899 and again in 1900, accompanied by his wife Lou Andreas-Salomé. He called his presence there the ‘decisive event’ of his life, and considered Russia his ‘homeland’, meeting Tolstoy, Leonid Pasternak, Diaghilev and many others, and absorbing the experience of high culture. For his offering, he recalls the image of a white horse released to pasture for the night, and its spirited showing.

In his roughly-hindered gallop,

How the fount of the species rose!

In the horse’s gallop, hindered only by the rope by which he will subsequently be tethered for the night, may be read the journey of the human spirit, hindered only by its being rooted in the body. In that show of spirit, the nature of the horse becomes apparent, and reveals the common nature of its species.

He felt the vastness – deep down!

He sang, and he heard – your legendary

Cycle enclosed within.

Rilke envisages the horse ‘hearing’ the call of its own genetic depths, and in its movements and attitude responding to the larger flow of spirit, that Orpheus represents. We should remember however that ‘the legendary cycle’ involves the death and transience of the individual, as well as semi-permanence through the persistence of the wider species. Anticipating the unravelling of the genetic code, Rilke asserts that the cycle of reproduction, birth, life, and death, is ‘enclosed within’ the individual, and by extension the species.

His image, I dedicate.

Rilke then adds a line to the traditional fourteen lines of the sonnet form, formally dedicating that image of the legendary cycle of the spirit, to the god, who embodies that cycle in his divine form.

I, 21 (Frühling ist wiedergekommen. Die Erde)

Spring has returned, once more. The Earth

Is like a child that knows many a poem,

Many, oh many…for her long labour

Of learning she’s granted this prize.

Rilke now celebrates the legendary Orphic cycle, as evoked by the course of the terrestrial seasons, and the return of Spring, which is like a prize granted to the Earth (by whom? – again anthropomorphism dominates the poetic style and thought), in the same manner that we give a reward to a child who can learn and recite poetry, except that the Earth knows many poems, many variants on the theme of renewal and regeneration.

Her teacher was strict. We admired

The white of the old-man’s-beard,

What, we ask, should the green, the blue,

Be called: she knows, she knows!

Rilke extends his analogy of the child learning and reciting poetry (though again we must ask who the ‘teacher’ might be in the context of Earth).

Earth, in your freedom, lightly you play

With the children. We’d love to catch you,

Joyful Earth. For the joyful succeed.

The poet celebrates the freedom, the lightness of Nature. This is not Nature ‘red in tooth and claw’ but the kindlier side of existence, the kind that a sheltered childhood enjoys. The joyful succeed, both in their inward development, and the sense of becoming a successor in the line of generations.

Oh, all that the teacher has taught her,

The many things printed on roots

And tall intricate stems: she sings, she sings!

Rilke would seem to suggest that the teacher is Orpheus, the singer, the spirit of life. Again, is not clear in such passages if Rilke envisages the life and spirit of the world as deriving from a real external spiritual force, or whether we are simply dealing here with metaphor, and the poet’s projection of his own spiritual elation onto the external world. Rilke in his letters rejected a conventional religious interpretation of his later work. He might therefore be embracing a pantheistic view of a divinity concealed within the fabric of existence, or identical with it; or positing a spiritual force not of divine origin that ‘inspires’ living forms; or he is simply personifying, in the figure of the ‘teacher’, life itself in its natural manifestations, which infuse Nature with living energy, and consciousness in the form of her creatures, without being the whole of Nature herself.

I, 22 (Wir sind die Treibenden)

We are the shoots,

But the pace of time

Treats us as slight

In the ever-enduring.

We are the bearers of life (certainly the life of the intellect), its shoots which are perpetually renewed in the cycle of seasons, in the cycle of life and death and rebirth of the species, though we are slight in our transient and brief lives, compared with the enduring universe.

Everything urgent

Will swiftly be gone,

Initiate first, in us

The lingering.

Since the transient passes swiftly, Rilke appeals to the god to initiate us in the process of simply lingering here, being aware, in the Taoist sense, perhaps, of immersion in Nature’s flow, or the Zen Buddhist sense of enlightenment and the achievement of the mental state of Nirvana (‘the going-out of the flame’). This ‘lingering’ might be viewed as contemplation only, or focused action (the ‘hew wood, carry water’ of Zen).

Youth, don’t brave mere speed,

Or throw yourself into

Every attempt to fly,

All things here are at rest:

The dark and the light,

The flower and the book.

The poet thinking of the contemporary development of powered flight, and also perhaps of the Greek myths of Icarus, who flew too near the sun, and Phaethon who failed to control the sun-god’s chariot, advises the young to restrain themselves, and consider the Things, the objects and forms within the world, which are in themselves unmoving and at rest, for example a single flower (as in Zen meditative practice), or a book which when closed is still and silent, and which must be read and interpreted in order to acquire ‘motion’ within the processes of mind.

I, 23 (O erst dann, wenn der Flug)

Oh, only then, when the flight,

No longer for its sake alone,

Soars into the heavenly

Stillness, enough in itself

To sail out, lightly, in space

With a skill that succeeded,

In play, the wind’s darling,

Rocking there, slender and sure –

Only when the attempt at flight, or by analogy the soaring nature of creativity (or personal development), rises into that stillness of the material atmosphere about us, into engagement that is with form and content, and becomes enough of a force purely in-itself to begin to create (or develop), summoning its skills in lifting from the ground of the prosaic, in creative play, confidently and in balance, will that attempt be truly effective.

Only when a pure ‘where to’

Prevails against youthful pride

In the dynamic ascent,

Will it, hastened by victory,

Close to the far-off distance,

Be, that which it alone reaches.

Only when we are absorbed in the task, in the flow, and forget pride, fame and the other distractions which hinder our efforts to create or develop, can the mind achieve what it aims at in its highest flights, and be both the arrow and the target. Only then can we be near to the god, to Orpheus, to the deeper life, which creativity or self-development alone allow us to reach.

I, 24 (Sollen wir unsere uralte Freundschaft, die großen)

Will we retain our old friendship with the great gods,

That fail to woo us, our harsh steel raised so sternly,

Knowing them not, rejecting them now, or suddenly

Being forced to search them out on our ancient maps?

Given that only the creative effort (say for example the art of poetry, or the process of self-development) will allow us to reach our true potential, Rilke asks whether the modern world can provide an environment where we can exercise our creative powers fully. Are the traditional paths to creativity and self-development waning in power, faced with a world of machines, of steel, that is indifferent to religion and the deeply human art and architecture of the past? Will we inherit only the traces of past effort, which we have to search out, as we search for the faces of gods in the corners of antique maps?

Those formidable friends, who bear the dead from us,

Without touching our turning wheels, at any point?

Our banquets are distanced from them, our bathing

Removed, and their messengers now far too slow,

Whom we always overtake.

Will we be separated from the spiritual forces that left us in touch with the dead, those spiritual forces that have nothing to do with our mechanised world, or the aspects of modernity that divorce our routine everyday lives from the natural world in which we originated?

Alone now, wholly

Dependent upon, yet not knowing each other,

We no longer treat the paths as lovely meanders,

But like flights of steps.

In a complex modern world of specialisation where we are dependent on each other but often strangers to one another, we no longer have time to wander creatively or contemplate the world and develop ourselves internally, Rilke claims, but rather we treat every moment as a material ascent, as ‘progress’ towards some unspecified goal that requires an expenditure of intense effort, an ascent, when we might achieve more by lingering in the maze of wandering paths.

In the furnace the old fire burns,

There alone, while the hammers are raised in the steam,

Ever larger. While we, like swimmers, lose strength.

The ancient paths to the spirit are still alive, the ancient creative fire still burns in the mind, that furnace of creativity and inspiration, but in a new solitude, a disconnectedness from the increasingly material world around it, whose power over us grows ever greater, while we, like exhausted swimmers wane in strength.

I, 25 (Dich aber will ich nun, Dich, die ich kannte)

But you now, you whom I knew like a flower

Whose name I did not understand,

Once more I’ll remember, and show them you, stolen one,

Beautiful player of the unsuppressible cry.

Rilke searches for some way to display, in contrast to this, the creative life-giving power of Orpheus, whom he had previously failed to comprehend, though being aware of the mythical name. He wishes to recall some image from his life that embodies creative performance, that reveals the presence of the life-force itself which Orpheus represents, a life-force that is beautiful in its manifestations and which cannot be suppressed or repressed but insists on outward expression. At the same time, he wishes to emphasise the double-realm, the transience of the artist, and the way in which death impinges on, and is interwoven with, our lives.

A dancer first, sudden one, body filled with hesitation,

Pausing, as if one had cast your young being in bronze:

Grieving, listening – Then, from the riches on high,

Music fell through your altered heart.

Illness was close to you. Already seized by the shadows,

Your blood ran darkly, yet, though suspicious of flight,

It still drove outwards into your natural springtime.

Again and again, broken by darkness and fall,

Earthbound, it gleamed. Until after that dreadful pounding,

It passed through the inconsolable open door.