Rainer Maria Rilke

Sonnets to Orpheus

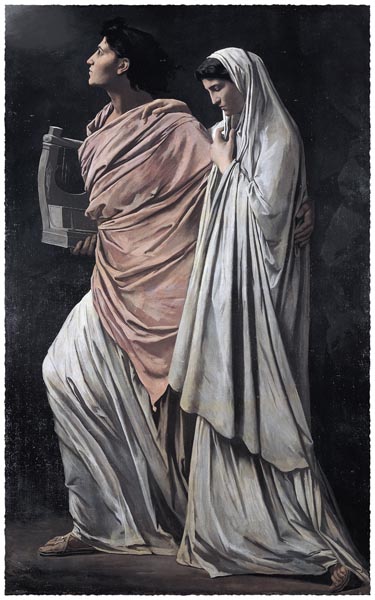

‘Orpheus and Eurydice’ - Auguste Anselm Feuerbach (German, 1829 - 1880), Artvee

Read more with a commentary on the Sonnets entitled The Dual Realm.

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2023, All Rights Reserved.

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Translator’s Introduction

- Part I

- I, 1 (Da stieg ein Baum. O reine Übersteigung!)

- I, 2 (Und fast ein Mädchen wars und ging hervor)

- I, 3 (Ein Gott vermags. Wie aber, sag mir, soll)

- I, 4 (O ihr zärtlichen, tretet zuweilen)

- I, 5 (Errichtet keinen Denkstein. Laßt die Rose)

- I, 6 (Ist er ein Hiesiger? Nein, aus beiden)

- I, 7 (Rühmen, das ists! Ein zum Rühmen Bestellter)

- I, 8 (Nur im Raum der Rühmung darf die Klage)

- I, 9 (Nur wer die Leier schon hob)

- I, 10 (Euch, die ihr nie mein Gefühl verließt)

- I, 11 (Steh den Himmel. Heißt kein Sternbild ‘Reiter’?)

- I, 12 (Heil dem Geist, der uns verbinden mag)

- I, 13 (Voller Apfel, Birne und Banane)

- I, 14 (Wir gehen um mit Blume, Weinblatt, Frucht)

- I, 15 (Wartet..., das schmeckt... Schon ists auf der Flucht)

- I, 16 (Du, mein Freund, bist einsam, weil....)

- I, 17 (Zu unterst der Alte, verworrn)

- I, 18 (Hörst du das Neue, Herr)

- I, 19 (Wandelt sich rasch auch die Welt)

- I, 20 (Dir aber, Herr, o was weih ich dir, sag)

- I, 21 (Frühling ist wiedergekommen. Die Erde)

- I, 22 (Wir sind die Treibenden)

- I, 23 (O erst dann, wenn der Flug)

- I, 24 (Sollen wir unsere uralte Freundschaft, die großen)

- I, 25 (Dich aber will ich nun, Dich, die ich kannte)

- I, 26 (Du aber, Göttlicher, du, bis zuletzt noch Ertöner)

- Part II

- II, 1 (Atmen, du unsichtbares Gedicht!)

- II, 2 (So wie dem Meister manchmal das eilig)

- II, 3 (Spiegel noch nie hat man wissend beschrieben)

- II, 4 (O dieses ist das Tier, das es nicht giebt)

- II, 5 (Blumenmuskel, der der Anemone)

- II, 6 (Rose, du thronende, denen im Altertume)

- II, 7 (Blumen, ihr schließlich den ordnenden Händen verwandte)

- II, 8 (Wenige ihr, der einstigen Kindheit Gespielen)

- II, 9 (Rühmt euch, ihr Richtenden, nicht der entbehrlichen Folter)

- II, 10 (Alles Erworbne bedroht die Maschine, Solange)

- II, 11 (Manche, des Todes, entstand ruhig geordnete Regel)

- II, 12 (Wolle die Wandlung. O sei für die Flamme begeistert)

- II, 13 (Sei allem Abschied voran, als wäre er hinter)

- II, 14 (Siehe die Blumen, diese dem Irdischen treuen)

- II, 15 (O Brunnen-Mund, du gebender, du Mund)

- II, 16 (Immer wieder von uns aufgerissen)

- II, 17 (Wo, in welchen immer selig bewässerten Garten, an welchen)

- II, 18 (Tänzerin: o du Verlegung)

- II, 19 (Irgendwo wohnt das Gold in der verwöhnenden Bank)

- II, 20 (Zwischen den Sternen, wie weit; und doch, um)

- II, 21 (Singe die Gärten, mein Herz, die du nicht kennst; wie in Glas)

- II, 22 (O trotz Schicksal: die herrlichen Überflüsse)

- II, 23 (Rufe mich zu jener deiner Stunden)

- II, 24 (O diese Lust, immer neu, aus gelockertem Lehm!)

- II, 25 (Schon, horch, hörst du der ersten Harken)

- II, 26 (Wie ergreift uns der Vogelschrei...)

- II, 27 (Giebt es wirklich die Zeit, die zerstörende?)

- II, 28 (O komm und geh. Du, fast noch Kind, ergänze)

- II, 29 (Stiller Freund der vielen Fernen, fühle)

- Index of First Lines

Translator’s Introduction

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875-1926) wrote the ‘Sonnets to Orpheus’ over an intensely creative three-week period in February 1922, during which he also completed the ‘Duino Elegies’. The Sonnets were prompted by the earlier death of Wera Knoop, a childhood friend of his daughter Ruth, and in them Rilke develops the theme of the double-realm of life and death, pursuing, as in the Duino Elegies, his desire to more-closely integrate what he saw as the valid sphere of death with the claims of life.

The descent of Orpheus, the mythical poet-musician of Thrace, into the underworld in a failed attempt to reclaim his dead wife Eurydice, and his subsequent death at the hands of the Bacchantes, provided Rilke with the framework of the sonnets. Elements of the Hellenistic Orphic rites of Dionysus may also have influenced Rilke’s thinking, in which adherents of the cult sought union with the divine in order to acquire mystic knowledge.

The poems also resonate with other deaths which figure elsewhere in his work. The overall tone of the sonnets is, however, positive and life-affirming. Rilke’s poetry was not, as he himself stated, intended as death-seeking, but rather a celebration of life, and an act of praise, in which death is recognised primarily in terms of the memories of the dead recalled by the human mind, and their influence on the living. In that sense the double-realm is certainly both valid and authentic.

The translations below do not attempt to recreate the rhyming verse forms used by Rilke, focussing instead on clarity of meaning and poetic intention. The first line in German of each sonnet is given in its heading, while an index of first lines in English is provided at the end. The division of the fifty-five sonnets into Part I, of twenty-six poems, and Part II, of twenty-nine, is Rilke’s, and reflects their two main phases of composition, either side of his completion of the ‘Duino Elegies’, rather than a structural division dictated by poetic form or content. It is recommended that the ‘Duino Elegies’ are read prior to, and in conjunction with, the sonnets, as the two works illuminate each other, reflecting the interwoven nature of their completion and final editing.

Part I

I, 1 (Da stieg ein Baum. O reine Übersteigung!)

A tree climbed there. O pure uprising!

Oh, Orpheus sang! O towering tree of hearing!

And all was still. Yet even in that hush

A new beginning, hint, and change, was there.

Creatures of silence pressed from the bright

Freed forest, out of nest and lair:

And they so yielded themselves, that not by a ruse,

And not out of fear, were they so quiet in themselves,

But simply through listening. Bellow, shriek, roar

Seemed small in their hearts. And where there was

Just barely a hut to receive it,

A refuge out of their darkest yearning,

With an entrance whose gate-posts trembled –

There you crafted a temple for their hearing.

‘Orpheus Playing to the Animals’ - Master of the Orpheus Legend (artist) Italian, active fourth quarter of the 15th century, The National Gallery of Art

I, 2 (Und fast ein Mädchen wars und ging hervor)

And it was almost a girl, and she came out of

That single blessedness of song and lyre,

And shone clear through her springtime-veil

And made herself a bed inside my hearing.

And slept within me. And her sleep was all:

The trees, each that I admired, those

Perceptible distances, the meadows I felt,

And every wonder that concerned myself.

She slept the world. Singing god, how have you

So perfected her that she made no demand

To first be awake? See, she emerged and slept.

Where is her death? O, will you still discover

This theme, before your song consumes itself? –

Where is she falling to, from me?... a girl, almost ...

I, 3 (Ein Gott vermags. Wie aber, sag mir, soll)

A god can do so. But tell me how a man

Is supposed to follow, through the slender lyre?

His mind is riven. No temple of Apollo

Stands at the dual crossing of heart-roads.

Song, as you have taught it, is not desire,

Not a proclamation of final achievement:

Song is being. A simple thing for a god.

But when are we in being? And when does he

Turn the earth and stars towards us?

Young man, this is not your having loved, even if

Your voice forced open your mouth, then – learn

To forget that you sang out. It fades away.

To sing, in truth, is a different breath.

A breath of nothing. A gust within the god. A wind.

‘Meleager and Atalante’ - Master of the Orpheus Legend (artist) Italian, active fourth quarter of the 15th century, The National Gallery of Art

I, 4 (O ihr zärtlichen, tretet zuweilen)

O you tender ones, sometimes progress

Deep inside the breath not meant for you,

Let it part before your face and, behind you,

Tremble, once more, as it flows together.

O you blessed ones, O you healers,

Who seem to be, where the heart begins,

Arrows fired from the bow, and the target,

You whose smile ever shines through tears,

Don’t be afraid to suffer the heaviness,

Return its weight once more to the Earth;

Mountains are heavy, the seas are heavy.

Even the trees you planted as children

Soon became too heavy. You cannot bear them,

But the air… but the space …

I, 5 (Errichtet keinen Denkstein. Laßt die Rose)

Raise no gravestone. Only let the rose

Bloom every year to favour him.

Since it is Orpheus. His metamorphosis

Into this and that. We need not strive

For other names. Once and for all

It is Orpheus, when he sings. He comes and goes.

Is it not much already that he, sometimes,

Stays, for a while, in the petal of the rose?

Oh, he must vanish, for you to understand!

And though he himself feared his vanishing,

Even as his word surpasses the being-here,

He is already there, where you cannot go.

The lyre-strings fail to constrain his hands.

And he responds, by his passing-beyond.

I, 6 (Ist er ein Hiesiger? Nein, aus beiden)

Does he hail from here? No, from both

The realms his expansive nature grew.

Knower, bend the branches of willow

So, you may understand the willow roots.

When you go to bed, leave on the table

Neither bread nor milk; they bring the dead;

But he, who is the Summoner, mingles

There, under the mild gentleness of eyelids,

Their apparitions with everything seen,

While the magic of rue and fumitory,

Is as true to him as the clearest relation.

Nothing lessens a valid form for him.

Whether it be in the room, or the grave,

He praises the jug, the bracelet, the ring.

I, 7 (Rühmen, das ists! Ein zum Rühmen Bestellter)

Praising, that’s it! One appointed to praise,

He emerged like ore from the silent stone.

His heart, oh, the transient wine-press, among

Humankind, of an inexhaustible wine.

When the divine mode grips him

The voice from his mouth never fails.

All becomes vineyard, all becomes grape,

Matured in his sentient south.

Neither the must in the tombs of the kings

Nor from the gods that a shadow falls,

Detracts at all from his praising.

He’s a messenger, who always remains,

Still holding, far through the doors of the dead,

A dish with fruit they can praise.

I, 8 (Nur im Raum der Rühmung darf die Klage)

In the region of praise alone may Lament walk,

That Nymph of the weeping fountain,

Watching over what flows about us,

So, it may fall here, bright, on the stone

That supports the gates and the altar.

See, round her motionless shoulders,

Dawns the feeling that she is the youngest

Among her siblings here in the mind.

Jubilation knows, Longing confessed,

Only Lament’s still in the process of learning,

With childish hands counting her ancient woes.

Then, suddenly, in the sky, awkward, unpractised,

She holds up our voices, a starry constellation,

A concatenation their breath yet fails to cloud.

I, 9 (Nur wer die Leier schon hob)

Only one who has raised the lyre,

Already, among the shades,

May sense how to return

The unending praise.

Only one who ate, with the dead,

Of the poppy, that is their own,

Will not lose the slightest

Note ever again.

Wish even the image in the pond

That blurs for us, often:

Know the reflection.

Only within the double sphere

Will the voices become

Kind, and eternal.

‘Aeneas Descending to the Underworld’ - Master of the Orpheus Legend (artist) Italian, active fourth quarter of the 15th century, The National Gallery of Art

I, 10 (Euch, die ihr nie mein Gefühl verließt)

To you, never lost from my feelings,

You ancient Sarcophagi, my greetings,

That the glittering water of Roman times

Flows through like a verse while walking,

Or that open wide, like the charmed eyes

Of some awakening shepherd in August –

Full of silence, and honeysuckle –

Out of which joyous butterflies go soaring.

All those who are snatched from limbo,

I greet, all the newly-reopened mouths,

Who know now what true silence means.

Are we certain, friends, or uncertain?

The juncture of both brings that doubt

Shown by the eyes in a human face.

I, 11 (Steh den Himmel. Heißt kein Sternbild ‘Reiter’?)

Halt the stars. Is there not one called the ‘Rider’?

That which is strangely imprinted within us,

The pride of the Earth? And then a second,

That he urges on and restrains, that bears him?

Is not the sinewy nature of Being pursued so,

And tamed? Turned to this side and that,

By merely the lightest of pressures,

Into a fresh tract of space. And the two are one.

Or are they? Do not either mean the path

That the two of them both travel together,

Still nameless, between ‘Table’ and ‘Field’.

Though a concatenation of stars deceives,

Yet we are happy to believe awhile

In its configuration. And that is enough.

I, 12 (Heil dem Geist, der uns verbinden mag)

Hail to the spirit, that holds us together,

Since we only exist by shape and form.

And in miniscule steps the clock ticks,

Set beside our actual day.

Without knowing our own true place,

We achieve real relationship;

The antennae feel the antennae,

And suffer the distance between…

Pure tension! O music of forces!

Is it not through a venial struggle,

That disaster’s deflected from you?

Though the anxious farmer labours

So that the seed becomes harvest,

It is never enough. Earth must bear.

I, 13 (Voller Apfel, Birne und Banane)

Fullness of apple, pear, blackcurrant,

Gooseberry…it all speaks life and death

In the mouth…I anticipate…

Go read it in some child’s face

As they taste it; it comes from afar. Are you

Slowly becoming nameless in your own mouth?

Where there were words, find a flow,

Strangely surprised from the flesh.

Dare to say what an ‘apple’ is called,

This sweetness that deepens within,

Gently ripening in taste,

To become, clear, alive and transparent,

Ambiguous, sun-kissed, earthy, and here:

Oh, experience feeling. Infinite joy!

I, 14 (Wir gehen um mit Blume, Weinblatt, Frucht)

We’re involved with flower, vine-leaf and fruit.

They don’t only speak the language of seasons,

A vision of colour that rises from darkness,

Betraying perhaps the jealous glances

Of the dead themselves, who enrich the Earth.

What do we know of her part in this?

It has long been her art to brand the clay

Freely, with her distinguishing mark.

The question is: does it bring them pleasure?

Urging the fruit forth; labouring enslaved,

To enclose and offer it, to us their masters?

Are they the powers that sleep in the roots,

And indulge us simply out of abundance,

Something between mute effort and kisses?

I, 15 (Wartet..., das schmeckt... Schon ists auf der Flucht)

Wait…that taste…It’s already in flood…

A slight music only, a throbbing, a murmur.

You girls, you warm, you silent ones, dance

The dance of the fruit that’s tasted and known.

Dance the orange; how could one forget

How, drowned in itself, it defends

Itself against its own sweetness; the fruit,

You possess, has been sweetly changed into you.

Dance the orange. The warmer landscape,

Fling it from you, so that ripeness may glow

In your native air! Shining, unveiled.

Scent after scent. Create the connection

With the pure, the resisting rind,

With the juice that fills the fortunate mouth!

I, 16 (Du, mein Freund, bist einsam, weil....)

You, my friend, are lonely, because…

With our words, with our gestures,

We gradually make this world our own,

Our weakest, most perilous, perhaps.

Who can gesture towards a scent?

And, of the many forces that threaten,

You feel a multitude. You know the dead,

And shudder at the spell that is cast.

See, now is a time to endure the mass

Of bits and pieces as if they were whole.

To help would be hard. Do not, above all,

Plant me in your heart, I’m growing too swiftly.

Yet I will guide my master’s hand to say,

Here, now. Here is Esau in his own pelt.

I, 17 (Zu unterst der Alte, verworrn)

In the depths, ancient tangle,

The mass of old roots,

The hidden source,

That is never seen.

Spiked helms and hunting horns,

Speaking of greyness,

Men in fraternal rage,

Women like lutes…

Branch thrusting at branches

None of them free… one there!

Oh climb…Oh climb…

Though they are broken still,

Yet the one there, on high,

Bends to a lyre.

I, 18 (Hörst du das Neue, Herr)

Do you hear the new, Master,

Roaring and trembling?

The harbingers, heralds, come

That proclaim it.

True no hearing is whole

Amidst this raging,

But the machine demands

That its role be praised.

See, how the machine heaves

And takes its revenge,

Distorting and weakening us.

Gaining its strength from us,

Let it, without passion,

Urge us onward, and serve.

I, 19 (Wandelt sich rasch auch die Welt)

Though the world alters swiftly

Like patterns of cloud,

All that’s perfected

Returns to its ancient place.

Beyond the change and departure,

Further away, and freer,

Your prelude still endures

God of the lyre.

Suffering is not grasped,

Love is not learned,

Nor is that which takes us far-off

In death ever unveiled.

The song alone, over the earth,

Celebrates, sanctifies.

‘The Sacrifice of Iphigenia’ - Master of the Orpheus Legend (artist) Italian, active fourth quarter of the 15th century, The National Gallery of Art

I, 20 (Dir aber, Herr, o was weih ich dir, sag)

But to you, Master, what shall I dedicate

To you, who taught creatures to listen? –

A memory of a spring day,

Its evening, in Russia – a horse,

From the village, a white horse came,

Alone, a rope at his forefoot,

To be fettered alone in the meadow,

All night – how his full mane shook

Over his neck, in tune with his spirits.

In his roughly-hindered gallop,

How the fount of the species rose!

He felt the vastness – deep down!

He sang, and he heard – your legendary

Cycle enclosed within.

His image, I dedicate.

‘The Sacrifice of a Bull’ - Master of the Orpheus Legend (artist) Italian, active fourth quarter of the 15th century, The National Gallery of Art

I, 21 (Frühling ist wiedergekommen. Die Erde)

Spring has returned, once more. The Earth

Is like a child that knows many a poem,

Many, oh many…for her long labour

Of learning she’s granted this prize.

Her teacher was strict. We admired

The white of the old-man’s-beard,

What, we ask, should the green, the blue,

Be called: she knows, she knows!

Earth, in your freedom, lightly you play

With the children. We’d love to catch you,

Joyful Earth. For the joyful succeed.

Oh, all that the teacher has taught her,

The many things printed on roots

And tall intricate stems: she sings, she sings!

I, 22 (Wir sind die Treibenden)

We are the shoots,

But the pace of time

Treats us as slight

In the ever-enduring.

Everything urgent

Will swiftly be gone,

Initiate first, in us

The lingering.

Youth, don’t brave mere speed,

Or throw yourself into

Every attempt to fly,

All things here are at rest:

The dark and the light,

The flower and the book.

I, 23 (O erst dann, wenn der Flug)

Oh, only then, when the flight,

No longer for its sake alone,

Soars into the heavenly

Stillness, enough in itself

To sail out, lightly, in space

With a skill that succeeded,

In play, the wind’s darling,

Rocking there, slender and sure –

Only when a pure ‘where to’

Prevails against youthful pride

In the dynamic ascent,

Will it, hastened by victory,

Close to the far-off distance,

Be, that which it alone reaches.

I, 24 (Sollen wir unsere uralte Freundschaft, die großen)

Will we retain our old friendship with the great gods,

That fail to woo us, our harsh steel raised so sternly,

Knowing them not, rejecting them now, or suddenly

Being forced to search them out on our ancient maps?

Those formidable friends, who bear the dead from us,

Without touching our turning wheels, at any point?

Our banquets are distanced from them, our bathing

Removed, and their messengers now far too slow,

Whom we always overtake. Alone now, wholly

Dependent upon, yet not knowing each other,

We no longer treat the paths as lovely meanders,

But like flights of steps. In the furnace the old fire burns,

There alone, while the hammers are raised in the steam,

Ever larger. While we, like swimmers, lose strength.

I, 25 (Dich aber will ich nun, Dich, die ich kannte)

But you now, you whom I knew like a flower

Whose name I did not understand,

Once more I’ll remember, and show them you, stolen one,

Beautiful player of the unsuppressible cry.

A dancer first, sudden one, body filled with hesitation,

Pausing, as if one had cast your young being in bronze:

Grieving, listening – Then, from the riches on high,

Music fell through your altered heart.

Illness was close to you. Already seized by the shadows,

Your blood ran darkly, yet, though suspicious of flight,

It still drove outwards into your natural springtime.

Again and again, broken by darkness and fall,

Earthbound, it gleamed. Until after that dreadful pounding,

It passed through the inconsolable open door.

I, 26 (Du aber, Göttlicher, du, bis zuletzt noch Ertöner)

But you, divine one, sounding out till the end,

Surrounded by the swarm of rejected maenads,

Have drowned their shrieks with order, lovely one;

Out of the chaos, your music rose in reply.

None could destroy your head, or your lyre,

How they rushed to attack you, how the sharp

Stones they hurled at your heart, were melted

In you, and endowed, there, with hearing.

Finally, urged by revenge, they shattered you,

While your sounds still lingered in lions, in stones,

And in birds, and trees. You’re still singing there!

O lost god! O everlasting sign of the way!

Only through enmity that tore you to shreds,

Are we, the hearers, a mouth for Nature.

‘The Death of Orpheus’ - Master of the Orpheus Legend (artist) Italian, active fourth quarter of the 15th century, The National Gallery of Art

Part II

II, 1 (Atmen, du unsichtbares Gedicht!)

Breath, you, invisible poem!

Always about individual

Being, pure exchange of space. Counterweight,

Through which I rhythmically exist.

Single wave who’s

Eventual sea I am,

You, the sparest of possible seas,

Gainer of space.

How many of these, spaces, were places already

Within me? Many a breeze

Is like some child of mine.

Do you know me, air, filled with my former places?

You once smooth bark,

Bole, and leaf of my words.

II, 2 (So wie dem Meister manchmal das eilig)

Just as the master, sometimes, in haste,

Strikes a true line from the paper drawn near,

So, a mirror will often draw the divinely

Unique smile of some girl, deeper within,

As she faces the morning, alone –

Or in the gleam of the evening lights;

And, upon the breath of the real face,

Later, descends the merest reflection.

What did her eyes discern in the ashes

Long smouldering there in the hearth;

Glimpses of life, vanished forever?

Oh, who can know of our losses on Earth?

Only those whose voices, nonetheless, praise,

Who sing of the heart, born to wholeness.

II, 3 (Spiegel noch nie hat man wissend beschrieben)

Mirror, none have ever truly described

What you are in your being.

You, like a sieve full of nothing but holes,

Filled with intervals of time.

You who squander the empty hallway,

When evening falls, as in some far forest,

And the chandelier, a sixteen-point stag,

Vanishes into your inaccessibility.

Sometimes you are full of paintings.

Some seem to have settled within you.

Others you’ve shyly sent on their way.

But the loveliest will remain – until

Into those frames, contained within,

Bright Narcissus, dissolving, enters.

II, 4 (O dieses ist das Tier, das es nicht giebt)

O this is the creature that has never been.

They never knew it and yet none the less

Its movements, aspects, slender neck,

Up to the still bright gaze, were loved.

True it never was, yet, it was, through their love,

A pure creature. They left it room enough.

And in that space, clear and un-peopled,

It raised its head lightly and scarcely needed

Being. It was never nourished with food,

But only the possibility of being.

And that gave the creature such power

That a horn grew from its brow. One horn.

In its whiteness it drew near a virgin girl –

And was in the silvered mirror, and in her.

II, 5 (Blumenmuskel, der der Anemone)

Flowery unfolding, that of the windflower,

Gradually opening in the meadow,

Until the polyphonic light pours

Into its lap from the sonorous sky,

Into the silent starry flower,

Unfolding in endless reception,

Sometimes so overwhelmed by abundance

That the lulling sense of falling

Is scarcely capable of returning

Those far-flung borders of leaf to you,

Enduring strength of how many worlds!

We, the violent ones, last longer,

But when, and in which of all our lives,

Are we, finally, open receptors?

II, 6 (Rose, du thronende, denen im Altertume)

Rose, you enthroned one, to those in ancient times

You were a single-rimmed chalice,

But to us you are the full, countless flower,

The inexhaustible object.

In your richness, you seem like fold on fold,

Clothing a body of nothing but splendour,

Yet at the same time your single leaf,

Is refusal, avoidance of every garment.

For centuries your scent has called out

To us – its sweetest name.

Suddenly it’s like fame, here in the air.

Still, we don’t know what to call it, we…

Guess, and the memory we summon

Goes to meet it, from sweet hours recalled.

II, 7 (Blumen, ihr schließlich den ordnenden Händen verwandte)

Flowers, at the end, you find hands arranging you,

(The hands of young girls, now, as long ago)

You who lie, end to end, on the table,

Wearied, and tenderly hurting,

Waiting for water, so you might revive,

In the death that’s already begun – then be,

Suddenly, raised between moistened tips

Of sensitive fingers that soothe you far more

Than you thought them able to, delicate ones,

On finding yourselves again, in some vase

Slowly cooling; warmth, like a girlish confession

Of dull wearisome sins, flowing from you,

Who celebrate being culled; warmth, like a bond

With them, who thrive in communion with you.

‘Mars and Venus’ - Master of the Orpheus Legend (artist) Italian, active fourth quarter of the 15th century, The National Gallery of Art

II, 8 (Wenige ihr, der einstigen Kindheit Gespielen)

(In memoriam Egon von Rilke)

You few, childhood playmates long ago,

In gardens scattered throughout the city,

How we found, and hesitantly liked, each other,

And, like the Lamb with the written scroll,

Spoke silently. When we found delight,

No one owned to it. Whose was it then?

How it dissolved among those going by,

And in the anxieties of the endless year.

Carts passed by us, vanishing strangers,

Houses surrounded us, solid but untrue;

None knew us. What was real in it all?

Only the ball flung high. Its glorious arc.

Not even the children…though sometimes one,

Oh, a vanishing one, beneath its fall.

II, 9 (Rühmt euch, ihr Richtenden, nicht der entbehrlichen Folter)

Judges, don’t boast that torture’s redundant,

That necks no longer bow beneath chains.

Nothing’s enhanced, not one heart…because

A longed-for spasm of tenderness melts you.

The scaffold returns what it received through

The ages, like a child re-giving the presents

From its last birthday. Into the high, pure, foolishly

Open heart, the god of true mercy would walk

Otherwise. He would come powerfully,

Seize us more radiantly, as a god will.

More than the breeze round an anchored ship,

Not less than the secret, quiet awareness

That in silence subdues us within,

Like the gentle play of the child of an infinite pairing.

II, 10 (Alles Erworbne bedroht die Maschine, Solange)

The machine would threaten all we have done,

If it dared to exist in spirit, not simply serve us.

Lest the controlling hand show a sweet hesitation,

It cuts the stone more exactly, to build more firmly.

It never lingers long enough for us to escape it,

To leave it, oiled, to itself, in the silent factory.

It is life – and thinks it best if the same exact

Intent arranges all, and creates, and destroys.

But for us existence is still enchanted, our origin

In a hundred places, a play of pure forces, no one

Encounters without kneeling in admiration.

Words are still sensitive to the unsayable,

And music, ever-renewed, from quivering stone

Still builds its heavenly house in unusable space.

II, 11 (Manche, des Todes, entstand ruhig geordnete Regel)

Many calmly-ordered norms for death have arisen,

Since ever-conquering man insisted on hunting.

More than the snare and the net, I know you,

You, strips of canvas, hanging in caves of karst.

You were set there quietly, as though as a signal

To celebrate peace. But then a lad shook the edge,

And, from some cavern, the night threw a handful

Of pale fluttering doves to the light…yet that too is lawful.

May the hunter not experience regret,

Nor the onlooker either, for such an act,

Though it be vigilant, prompt in its action.

Killing’s a grievous form of our straying…

While what happens within ourselves

Is pure, to the calm and serene spirit.

‘Meleager Hunting the Calydonian Boar’ - Master of the Orpheus Legend (artist) Italian, active fourth quarter of the 15th century, The National Gallery of Art

II, 12 (Wolle die Wandlung. O sei für die Flamme begeistert)

Will transformation. O long for the flame,

Where a Thing escapes you, splendid in change:

That designing spirit, master of what is earth,

Loves only the turning-point in the form’s curve,

What closes itself, to endure, already freezes:

Does it feel safe in the refuge of drabbest grey?

Wait: the hard’s warned, by the hardest – from far away,

A blow – the absent hammer is drawing back!

Who pours out like a spring, knowing knows him:

And leads him delighted through the bright creation,

That often ends with the start, and begins with the end.

Every fortunate space is a child or grandchild of parting,

Whose passing-through amazes. And Daphne, altered,

Since she became laurel, wants you to alter to breeze.

‘Apollo and Daphne’ - Master of the Orpheus Legend (artist) Italian, active fourth quarter of the 15th century, The National Gallery of Art

II, 13 (Sei allem Abschied voran, als wäre er hinter)

Be in front of all parting, as though it were now

Behind you, like the winter gone by.

Because among winters is one so endlessly winter

Only by over-wintering does your heart still survive.

Be always dead in Eurydice – climb, with more singing,

Climb with praising, back to the pure relation.

Here, in the failing place, the exhausted realm,

Be a sounding glass that rang as it shattered.

Be – and know, at that time, the state of non-being,

The infinite ground of our deepest vibration,

So that you may wholly complete it this one time.

In both the used-up, and the hollow and dumb

Recourse of all nature, the un-tellable sum,

Joyfully count yourself one, and destroy the number.

‘Orpheus and Eurydice Before Pluto’ - Master of the Orpheus Legend (artist) Italian, active fourth quarter of the 15th century, The National Gallery of Art

II, 14 (Siehe die Blumen, diese dem Irdischen treuen)

See the flowers, those, so true to the Earth,

To whom we lend fate from the margin of fate –

But who knows! If they regret withering,

It is for us to be their regret.

All would soar. Only we walk round complaining,

Laying down Self from it all, delighted with weight:

Oh, to Things what wearisome teachers we are,

While endless childhood succeeds in them.

Let someone fall into profound slumber, and sleep

Deeply with Things – O how easily they’d come

Differently to a different day, from the mutual deep,

Or perhaps remain: and flowers would bloom, and praise

Their convert, one now like them

All those mute brothers and sisters, in the winds of the fields.

II, 15 (O Brunnen-Mund, du gebender, du Mund)

O fountain-mouth, you Giver, you Mouth,

Inexhaustible speaker of one pure thing –

You, marble mask in the flowing face

Of water. And, in the land behind,

The aqueducts’ sources. From further,

Past graves, from Apennine slopes,

They bring you your speech, that then,

Past the darkened age of your chin,

Falls, down to the basin below.

This is the sleeping recumbent ear,

The marble ear you always speak to.

An ear of the Earth. She only talks

To herself like this. Place a jug there,

It seems to her that you’ve interrupted.

II, 16 (Immer wieder von uns aufgerissen)

Torn open by us, again and again,

The god is the place that heals.

We are the eager ones, seeking to know,

While he is joyously scattered.

Even the pure, the sacred offering,

He receives in no other way into his world

Than by being himself the free pole,

Both counterpoised, and unmoving.

Only the dead drink

From the source we but heard here,

When the god silently beckons them, the dead.

We are offered only its sound. While the lamb,

With its greater feeling for silence,

Seeks out the bell.

II, 17 (Wo, in welchen immer selig bewässerten Garten, an welchen)

Where, in what blissfully watered garden,

On what leafless trees, from what tender blossom,

Do the strange fruits of consolation ripen?

Those delicacies found in the trampled meadow,

Perhaps, of your need. Do you sometimes wonder

At the size of the fruit, at its wholeness,

It’s softness of rind, how some careless bird

Failed to be there before you, or a jealous worm

From beneath. Are there trees where angels perch,

Slowly, strangely, tended by hidden gardeners,

So, they sustain us without them being ours?

Have we ever been able, we Shades, we Shadows,

With our too-quickly-ripe, swift-decaying actions,

To disturb the summer’s serene equanimity?

II, 18 (Tänzerin: o du Verlegung)

Dancer, oh movement,

Vanishing in passing, how you performed.

And that whirl at the end, a sapling swaying,

Did it not take possession of this harsh year?

Did it not bloom, so your earlier motion

Suddenly surrounded its crown of silence?

And, above, wasn’t that summer, the sun,

The warmth, the undying warmth in you?

It bore fruit too, fruits, your tree of rapture,

Aren’t these they: the richly-striped pitcher,

And, there, the more-slowly maturing vase?

And in the portraits: does not the sketch remain,

That the line of your darkened brow drew

On the whirling-about of its whirling?

II, 19 (Irgendwo wohnt das Gold in der verwöhnenden Bank)

In the bank somewhere, gold is accommodated.

It lives on close terms with thousands. But here

The blind beggar is like the location of some lost coin,

Is akin to some dusty corner under the cupboard.

Money, it would seem, is at home in the stores,

Clothing itself there in silk, furs, carnations,

He, the silent one, stands, here where it pauses

For breath, all that wealth, sleeping or waking.

Oh, how does it close at night? That ever-open hand?

Pale, and wretched, and wholly destructible

Tomorrow fate overtakes it, extends it to all.

If but one watcher might comprehend and praise,

In amazement, that endless feat of endurance!

Sayable to those who sing. Audible to the god.

II, 20 (Zwischen den Sternen, wie weit; und doch, um)

The stars…how distant, yet how much further

What is found here. One, for example a child…

And, beside that child, a second, another –

Oh, how unbelievably distant.

Fate measures us with Being’s measure,

Perhaps; such that, to us, it seems strange.

Think of the distance between woman and man,

Whenever she moves apart, and considers, him.

All’s distance – nowhere the circle closes.

Look at the bowl on the neatly-laid table,

At the peculiar face of the fish.

Fish are dumb, people say…but who knows?

Is there not, in the end, a place where one might

Speak the language of fish, without speaking it?

II, 21 (Singe die Gärten, mein Herz, die du nicht kennst; wie in Glas)

Sing those gardens, my heart, that you know nothing of.

Like gardens enclosed in clear glass, unattainable.

The fountains and roses of Isfahan, Shiraz,

Sing them, as blessed; praise them, incomparable.

Show, my heart, that you’re never deprived of them,

That their ripening figs are still meant for you,

That with them you frequent, midst blossoming branches,

The swelling breeze that caresses the face.

Avoid the mistake of fearing some deprivation

As a result of that decision once made: to be!

Silken thread, you are a part of the weave.

Whatever the image you’re joined to, within,

(Be it only for a moment, in a life of pain)

Feel that the whole of the glorious tapestry is meant.

II, 22 (O trotz Schicksal: die herrlichen Überflüsse)

Oh, despite fate, the glorious effervescence

Of our existence, overflowing in parkland,

Or as stone statues, carved beside keystones,

Bearing the arches, treed beneath balconies!

Oh, the brass bell that raises its clapper,

Each day against dull everyday life;

Or that pillar in Karnak, that column,

That outlasts the ‘eternal’ temples.

Today, in the same way, that over-abundance

Soars past, from the horizontal yellow

Of day to the blinding outflow of night.

Though the tumult fades, leaves no trace behind,

The arcs of airy flight, those that create them,

Are, perhaps, not nothing, but those once merely imagined.

II, 23 (Rufe mich zu jener deiner Stunden)

Summon me to that hour, among those

Of yours, that, endlessly, resists you,

Close and imploring like a dog’s face,

But turning away, as you think, at last,

You might finally comprehend it.

What is elusive is yours most of all.

We are free. We’re released from that

Which we thought had made us welcome.

Anxious, we long for something to hold,

Often too young for what is ancient,

Too old for what never existed.

We, truly here, only when we praise,

We, that, alas, are the branch and the axe,

And the sweetness of ripening danger.

II, 24 (O diese Lust, immer neu, aus gelockertem Lehm!)

Oh, the delight, ever new, of loosened soil!

There was scant help for the earliest venturers.

Yet cities rose beside fortunate bays.

Water and oil, nonetheless, filled the jars.

Gods, in bold strokes we define them,

Which fate morosely erases, again and again.

And yet they are the immortals. Behold,

We may in the end obey those who listen.

We, one species, through the millennia,

Parents filled evermore with the child we bear,

That will, one day, shake, then transcend, us,

We, endlessly daring, what time we yet have!

And only death, silently, knows what we are,

And what’s gained from what’s lent to us.

II, 25 (Schon, horch, hörst du der ersten Harken)

Listen, can you hear the first plough

Already labouring? The human rhythm

Once more, in the subdued silence,

Of early spring’s winter-hardened soil.

It never seems banal, what is to come.

What came to you so many times before

Seems now to reappear as if it were new.

Ever longed-for, you never seized it, it seized you.

Even the leaves of once-wintry oak-trees,

Shine in the evening with colour to come.

Sometimes the breezes exchange a sign.

The bushes are black. Yet the heaps of dung

Are an even deeper black in the fields.

Every hour that goes by seems younger.

II, 26 (Wie ergreift uns der Vogelschrei...)

How we are moved by the bird’s call…

Some single screech uniquely created.

Yet the children scream, as they play

Outdoors, beyond the need for screaming.

Screaming at random. Into this world-space,

Of cosmic space (into which the whole

Bird-call enters as people enter our dreams)

They drive their screams like wedges.

Oh, where are we? Ever more freely,

Like the loose dragon-kites we chase

At half-height, brimming with laughter,

Torn by the wind. God of song, so order

The screaming throng that, in rushing, they waken

A flowing current bearing the head and the lyre.

II, 27 (Giebt es wirklich die Zeit, die zerstörende?)

Does it truly exist, Time, the destroyer?

On the silent hill, will it raze the castle?

Will the Demiurge, then, violate you,

Heart, that forever belongs to the gods?

Are we really so dreadfully fragile

As fate would have us believe?

Is the promise, deep at the roots

Of childhood, afterwards stilled?

Oh, the ghost of the transient,

Through receptive innocence

Passes, like smoke.

As that which we are, the doers,

We apply to that which remains,

The godlike strength of the known.

II, 28 (O komm und geh. Du, fast noch Kind, ergänze)

Oh, come and go. You, almost a child still, add,

For a moment, your dance-move

Into the pure constellation of dances

In which dull orderly Nature’s

Transiently overcome, for she was stirred

To total hearing only when Orpheus sang.

You were still moved by those things

And easily surprised if any tree took time

To follow after you into the listening.

You still knew the place where the lyre

Was lifted, in sound – the un-heard centre.

For it, you tried out your lovely steps,

In hope; to turn, one day, your friend’s face,

And course, towards healing celebration.

II, 29 (Stiller Freund der vielen Fernen, fühle)

Quiet friend of the many distances, feel

How your breath still enlarges space.

Let yourself ring out, a dark cradled bell

In the timbering. That, which erodes you

Gains a strength from your sustenance.

Go out and in, through transformation.

What do you know of the greatest loss?

Is drinking bitter? Then, become wine.

Be, in this night made of excess,

The magic art at the crossroads of senses,

The feel of their strange encounter.

And, if the earthbound forget you,

Say to the silent Earth: I flow.

To the rushing water: I am.

Index of First Lines

- A tree climbed there. O pure uprising!

- And it was almost a girl, and she came out of

- A god can do so. But tell me how a man.

- O you tender ones, sometimes progress

- Raise no gravestone. Only let the rose.

- Does he hail from here? No, from both.

- Praising, that’s it! One appointed to praise,

- In the region of praise alone may Lament walk,

- Only one who has raised the lyre,

- To you, never lost from my feelings,

- Halt the stars. Is there not one called the ‘Rider’?.

- Hail to the spirit, that holds us together,

- Fullness of apple, pear, blackcurrant,

- We’re involved with flower, vine-leaf and fruit.

- Wait…that taste…It’s already in flood…...

- You, my friend, are lonely, because…...

- In the depths, ancient tangle,

- Do you hear the new, Master,

- Though the world alters swiftly.

- But to you, Master, what shall I dedicate.

- Spring has returned, once more. The Earth.

- We are the shoots,

- Oh, only then, when the flight,

- Will we retain our old friendship with the great gods,

- But you now, you whom I knew like a flower

- But you, divine one, sounding out till the end,

- Breath, you, invisible poem!

- Just as the master, sometimes, in haste,

- Mirror, none have ever truly described.

- O this is the creature that has never been.

- Flowery unfolding, that of the windflower,

- Rose, you enthroned one, to those in ancient times.

- Flowers, at the end, you find hands arranging you,

- You few, childhood playmates long ago,

- Judges, don’t boast that torture’s redundant,

- The machine would threaten all we have done,

- Many calmly-ordered norms for death have arisen,

- Will transformation. O long for the flame,

- Be in front of all parting, as though it were now..

- See the flowers, those, so true to the Earth,

- O fountain-mouth, you Giver, you Mouth,

- Torn open by us, again and again,

- Where, in what blissfully watered garden,

- Dancer, oh movement,

- In the bank somewhere, gold is accommodated.

- The stars…how distant, yet how much further

- Sing those gardens, my heart, that you know nothing of.

- Oh, despite fate, the glorious effervescence.

- Summon me to that hour, among those.

- Oh, the delight, ever new, of loosened soil!

- Listen, can you hear the first plough.

- How we are moved by the bird’s call…...

- Does it truly exist, Time, the destroyer?.

- Oh, come and go. You, almost a child still, add,

- Quiet friend of the many distances, feel

Read more with a commentary on the Sonnets entitled The Dual Realm.