Wolfram von Eschenbach

Parzival

Book XII: The Garland

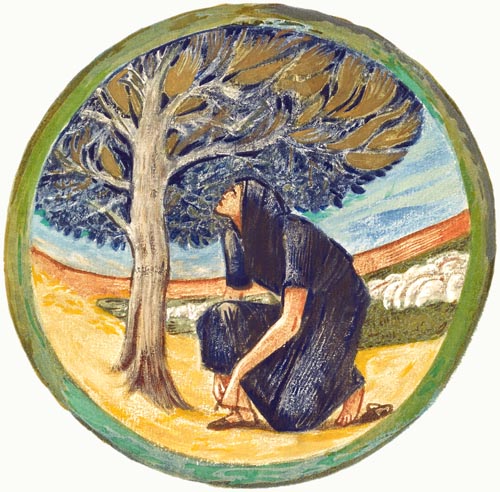

‘Fire Tree’

From The Flower Book, Sir Edward Burne-Jones (English, 1833 – 1898)

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2020 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Wolfram comments on Gawain’s love-pangs.

- Gawain gazes on the wondrous Pilla.

- Queen Arnive explains its nature.

- In the pillar, Gawain sees Orgeluse, with the Turkoyt, Florant of Itolac, approaching.

- Gawain defeats the Turkoy.

- Gawain is set the challenge of the Garland.

- The Perilous Gorge.

- Gawain gains a Garland from the tree.

- Gawain agrees to fight King Gurnemanz at Joflanze.

- Orgeluse seeks Gawain’s aid.

- She speaks of Anfortas, Clinschor and her attempts against Gramoflanz.

- Gawain seeks to maintain his anonymity at the Castle.

- He and Orgeluse are entertained by the ferryman.

- Gawain is welcomed back to Schastel Marveile.

- He writes to Arthur to request his presence at the due.

Wolfram comments on Gawain’s love-pangs

IF any sought to disturb his rest,

When Lord Gawain needs the best

Repose that he can find, I’d say

Much guilt upon that person lay;

For, as the tale bears witness, he

Has taxed his strength dreadfully,

And though crowned with all success,

Achieved it under great duress.

The suffering felt by Lancelot

On the Bridge of Swords, and what

The battle with Meljahkanz brought,

To Gawain’s perils were as naught;

Lesser seem the deeds, as well,

Of proud and mighty King Garel,

Who drove the lion from the court

At Nantes. And then, the knife he brought,

That which caused him so to suffer

There, within the marble pillar.

Were a mule to be loaded, now,

With all the missiles he did allow

To be fired at him, by subtle art,

At the dictates of his noble heart,

The mule could not the burden bear.

The Perilous Ford, that whole affair,

Nor Erec’s winning Schoydelakurt

From Mabonagrin, caused such hurt,

As did these sufferings of Gawain’s;

Not e’en what came of proud Yvain’s

Pouring water on the wondrous stone.

And if all these, not just one alone,

Were placed against those of Gawain,

Who, here, embraced a wealth of pain,

His sufferings would outweigh them all,

So they’d judge who can judge at all.

What suffering do I speak of? I,

(Though the sun’s barely in the sky),

Will tell you plainly, the Lady,

Orgeluse, had entered deeply

Into Gawain’s living heart,

A man who ever played his part

With true courage, steadfastly.

But how could any woman be

Hidden within so small a space?

By a narrow path she came apace

Into that heart, yet the suffering

That to that heart she did bring,

Banished all his woe and pain,

From her great joy it did obtain.

It was but a constricted place

Which, with her presence, she did grace,

Within one whose every thought,

Constantly that presence sought.

Let none mock that some woman,

Can dwell within a warlike man.

Heavens, what then doth all this mean?

Tis Mistress Love; she vents her spleen

On one who’s gained the victory,

And earned himself no little glory.

She found him mighty enough then,

And since he yielded to her when

He was as yet unscathed, she might

Have shown favour to her knight,

And not used force upon him now,

When pain and suffering pales his brow.

Mistress Love, if you seek honour

Such brings naught but dishonour.

Gawain has lived his whole life ever

At your command, as did his father,

King Lot; his mother’s family

Acknowledged your authority,

Since, long ago, when Mazadan

Was taken to Mount Famurgan

By Terdelaschoye, there, where you

Aroused deep passion, as you do.

Of his descendants we have heard

None were spared, all were stirred,

By your attentions. And King Ither,

Of Gaheviez, was such a lover

And bore the mark of your seal.

His name alone did e’er reveal

Your power when it was spoken

Among ladies, a true token,

Of Love’s might to all who saw him,

A bright light, that will ne’er grow dim.

For they, indeed, knew how to love!

Great loss his death to you did prove.

Must death now be Gawain’s sad lot?

Will you hound him like fair Ilinot,

His cousin, who, we understand,

Fled from his father Arthur’s land,

When but a youth? Twas your power

Made him strive (yet, alas the hour!)

For the favour of Kanadic’s Florie.

As an exile from his own country,

He was raised by that same Queen,

Yet she, whom he loved, was seen

To drive him beyond her border;

And you’ll have heard moreover

How he died in her service there.

Gawain’s line has known much care

And anguish, oft by love assailed.

I’ll name one more that love has paled,

His kinsman too; why did the snow,

Blood-tinged, torment Parzival so?

The queen, his wife, was the cause.

Brave Gahmuret obeyed your laws,

And Galoes, his brother, and you

Consigned them to their biers too.

Itonje, Gawain’s sister, did prove

Faithful and constant in the love

She bore King Gramoflanz, and she

Was young, noble, of great beauty.

Mistress Love, you did, further,

Through her love for Alexander

(Of Byzantium he was emperor),

Plague Surdamur, Cligès’ mother;

Nor did you ever spare from pain

The many kin of Lord Gawain,

Both these, and every other too,

Who rendered their service to you,

Mistress Love. Now, glory you seek

Oppressing him, wounded and weak,

To whom you should grant repose,

And reserve your strength for those

Who are well and strong. Full many

A man sings of love’s pain, though he

Knows no such torments as Gawain.

Yet sweet silence I should maintain,

And let the love-poets now lament

The state of this knight, who lies spent,

After that perilous venture,

And yet achieved glory and honour,

When Love’s fierce hailstorm, no less,

Broke o’er him, in his helplessness.

‘Alas,’ he mused, ‘that ever I saw

This pair of beds; that one, before,

Wounded me, and brought me pain,

This other has stirred my love again.

The Duchess Orgeluse must show

Me mercy, if happiness I’d know.’

He tossed and turned impatiently,

Bursting his bandages; thus, did he

Lie in anguish, before the dawn.

But lo, the sun heralds the morn,

And shines down on him who waited,

Though to no small discomfort fated,

For in the past he had endured

Many a joust with lance and sword

With greater ease, felt more blessed

Than now, when he but sought to rest.

If any love-poet would maintain

He suffers as much as Lord Gawain,

Let him receive that hail of fire,

From crossbow-bolts, and acquire

As many wounds; they’ll make him smart,

More than all those achieved by art.’

Gawain gazes on the wondrous Pillar

GAWAIN was weighed down with love

And other ills, but the sun did prove

So bright the rays it cast outshone

His bright candle; the night was gone;

He rose. His smallclothes did share

Stains of blood and armour, but there

Beside the bed were doublet and hose

Of fine buckram, which I’d suppose

He’d welcome gladly; a sleeveless

Robe, of marten fur I would guess,

And a jerkin, of like fur, there was,

And then, of some cloth of Arras,

A garment to sit above them all.

A pair of boots too were on call.

All these new clothes he put on,

Opened the door, and strode on,

Till he came to the palace hall.

So fine was it, both wide and tall,

He’d ne’er seen aught to compare.

At one side of the great hall there,

A spiral staircase, broad and strong,

Rose through the space, and beyond,

And bore, within it, a fine pillar

Not made of fragile wood but harder,

And burnished, and so tall in height

Camilla’s sarcophagus might

Have rested there, quite fittingly,

(A fine tomb, in story, had she).

Clinschor had the rare work brought

From Feirefiz’s realm to this court.

The pillar was rounded, like a tent,

And all the measured skill that went

To its making, would now surpass

The skills of Master Geometras,

Were he to set his hand to such,

For subtle art that work did touch.

The stairway’s windows glowed bright

With precious gems, a wondrous sight;

There topaz, garnet, chrysolite,

Amethyst, diamond, shed their light,

Emerald, and sard, and ruby,

So, it seems; so runs the story;

And the windows were as wide

As they were tall, on every side,

While the ceilings above them set,

Were styled like their columns, yet

No window-column could compare

With that pillar within the stair;

The tale tells of its wondrous nature.

Alone as he was, that watch-tower,

With all its costly gems, he climbed,

To view the scene, and he did find

Such marvels as he never tired

Of gazing at, as round he gyred;

For it seemed to him that every land

Showed in the pillar, close at hand,

And there they all went, swirling round,

Great mountains, clashing there, he found,

And he saw people in the pillar,

Riding, walking, here some other

Running, standing; so, he sat then,

In a window-bay, to study again

All this wondrous thing, and see

All its marvels more completely.

Queen Arnive explains its nature

AND now there came the wise Arnive,

And with her, her daughter, Sangive,

Gawain’s mother, and sweet Condrie,

And another sister of his, Itonje.

All four advanced towards Gawain,

Who needs must rise to his feet again.

‘You should be sleeping,’ said Arnive,

‘You who seemed barely alive,

Are too badly hurt to scorn your rest,

If with fresh trials you’re to be blessed.’

‘My lady, and mistress of the art

Of healing, you now, for your part,

Have so restored my mind and body

That I must be your servant wholly.’

‘If you submit to me as mistress,

Then greet these ladies with no less

Than a kiss; so to do is fine,

As all three are of royal line.’

Happy to do so, Gawain, at that,

Kissed those lovely women; they sat

All four, and so did Lord Gawain.

He gazed at the daughters again,

Though the image within his heart

Of she, who did from him depart,

Compelled him to admit that they

Were scarce as bright as a misty day,

Compared with her, such loveliness

He found in Orgeluse, the Duchess

Of Logroys, towards whom his love

Turned, she whom he did so approve.

In the pillar, Gawain sees Orgeluse, with the Turkoyt, Florant of Itolac, approaching

NOW Gawain had been presented,

To all three ladies; all consented

To a kiss in greeting; and all three

Were so dazzling, that full readily

A heart that knew not pain before

Might have been pierced to the core.

He sought now to know the nature

Of that most marvellous pillar.

And Arnive replied ‘Sir Knight,

This stone has shone day and night,

Ever since I first came to know it

Over the countryside below it,

Through a space of six miles wide,

Around the castle on every side.

All that happens within that space,

All that on land or sea takes place,

Can be seen within the pillar,

It acts as if it were a mirror,

For bird and beast, every stranger,

Or local, known or unfamiliar,

All of them are reflected there!

It shines six miles through the air,

And, then, is so solid and entire

A smith might labour and yet tire

To flaw it, for with all his might

He could hammer yet, and still

He’d fail; twas had of Secundille

The queen in royal Thabronit,

Without her leave, I must admit

To thinking.’ Now, in the pillar,

Gawain saw, as in a mirror,

At that instant, riding swiftly,

A knight, it seemed, and a lady.

He thought that lady very fair.

Man and steed were armoured there,

The helm adorned with its crest.

They rode in haste, and as if pressed,

O’er the causeway, to the meadow.

Gawain was their object, and so,

Through the marsh they made their way,

On the track Lischois took that day

When he was conquered by Gawain.

The lady led the knight, twas plain,

By his horse’s bridle, and the knight

Clearly was brought there to fight.

Thinking the pillar lied, Gawain

Now turned away from it in pain,

Then saw twas Orgeluse indeed,

Who, with a noble knight, at speed,

Approached the quay; this he saw,

And yet like pungent hellebore,

So swift to act, she stung his eyes,

This Duchess, and in similar wise

Pressed onward to his heart, to prove

Him helpless in the face of love;

Just such a man was Lord Gawain.

He turned to Queen Arnive again,

His mistress, on seeing the sight.

‘Madam,’ he said,’ here is a knight

With upraised lance who, to my mind,

Doth seek the fight which he shall find;

Yet tell me now, who is the lady?’

‘The Duchess of Logroys, that lovely

Woman is she; whom doth she seek,

For on that one great harm she’ll wreak?

He is the Turkoyt, of whose spirit

All oft have heard, a man of merit,

Who with his lance has earned great fame,

Enough to grant three lands a name.

You should avoid so brave a knight,

Tis much too soon for you to fight,

Sadly-wounded as you are now.

And even were you not, I vow,

You ought to decline the battle.’

‘If I’m the lord of this fair castle,

As you say,’ said my Lord Gawain,

‘When a brave man seeks, as is plain,

Single combat, upon my honour,

I must reach for arms and armour.’

Gawain defeats the Turkoyt

THE ladies wept, all four: ‘Fight not,

Or fame and fortune may be forgot,’

They cried, ‘for, should you be slain

That would but bring us deeper pain;

And if from death you should escape,

With your wounds in their sad state,

And all armoured, you still would die.

Either way, we’ll suffer thereby.’

Gawain with all this must contend:

The Turkoyt did his honour offend,

His wounds gave him endless pain,

And now Love troubled him again,

Not to mention these ladies four

Whose woe pained him as before,

Full mindful of their sincerity;

‘Weep not, dear ladies!’ was his plea.

He asked then for his fine charger,

And his sword, and his steel armour,

And those four ladies led him down

To where the rest were to be found,

Those other ladies, sweet and fair.

He soon was armed for the affair,

Bringing tears to many an eye,

And giving rise to many a sigh.

This was all done most secretly,

Lest any other man should see,

Apart that is from the chamberlain

Who clad the mount of Lord Gawain.

He tiptoed out to where Gringuljete

Was standing, but his wounds as yet

Were so painful he scarce could carry

His shield, well-clawed by his quarry.

He mounted his war-horse, and then

Rode from the castle, and again

Sought out the master of the ferry,

Whose service proved exemplary.

He gave Gawain a good fresh lance;

(For him twas common circumstance

To gather such things from the field)

Once Lord Gawain a lance did wield,

He asked to be ferried o’er the flood,

To where the proud Turkoyt now stood.

He and Plippalinot, thus, did glide,

With Gringuljete, to the other side.

Now, the Turkoyt was of high renown,

For all he met with he threw down,

All who fought him, seeking honour.

Full free of all stain of dishonour,

He’d sworn his fame he would advance

Employing nothing but the lance,

And sword-less would win his fame.

If any could his downfall claim,

Unseat him wholly, and so render

Him unarmed he would surrender.

Gawain had this of the ferryman,

Plippalinot, who did ever stand

To gain the mounts of those who fell,

If the winner kept his saddle well,

Without that winner, or the loser,

Resenting his gain, moreover,

For he played the stake-holder there;

Such were the terms of each affair.

The loser’s horse he’d lead away,

And leave it to the ladies to say

Who’d won, and who’d lost renown.

While they saw many a joust go down,

He cared little how they were fought!

Thus, to the shore Gawain he brought,

And, telling him to keep his seat,

He led the horse ashore; complete

With lance and shield, Gawain waited.

The Turkoyt barely hesitated,

Now, at the gallop, he did advance,

Neither too high nor low his lance.

Gawain now steered his Gringuljete

Towards the meadow where they met

(The steed from Munsalvaesche obeyed,

Gawain advancing unafraid).

Come, let them joust, now! King Lot’s son

Rode manfully; in his heart twas won.

Where helmet-laces are knotted, there,

The Turkoyt’s thrust did land; but fair

Was Gawain’s, and caught the other

Full squarely amidst his vizor,

And clear it was which man must fall.

Gawain had lifted helm and all

From the Turkoyt, on his brave lance,

Tearing it from him in his advance,

And there upon the ground he lay,

The flower of excellence till that day,

Clothing the grass in sad manner,

The flowers vying with his armour,

In the dew. Gawain rode to the man

And took his surrender, the ferryman

Claiming the horse, as was his due,

And who would deny him? Not you.

‘Oh, you might well be proud indeed,

If it were cause for pride, this deed,

Where a lion’s paw, half-concealed,

Follows, embedded in your shield!’

Cried Orgeluse, to vex Gawain,

‘And now you’ll seek to proclaim

Your renown, since the ladies here

Have witnessed your luck. No fear!

For we must leave you to your bliss.

Yet you may dance for joy at this,

That the Lit Marveile let you go,

Your shield somewhat battered though,

As if you’d suffered in some fight;

Your wounds too are scarcely light.

You silly goose! Go prize a shield,

That at each point was forced to yield

Pierced by bolts, holed like a sieve;

Great honour indeed such doth give!

Flee now; nurse each ache and pain,

And be witness, thus, to my disdain.

Retire! How could you contemplate

The dangers that must be your fate,

The mountains that you must move,

If you would serve me, out of love!’

‘Madam,’ he answered the Duchess,

‘If I am wounded, yet I may bless

The aid I found here. If such desire

To help a man may be yet entire,

And be reconciled with the favour

Of accepting the service I’d render,

There is indeed no danger so great

I’d not embrace it. Such be my fate;

In serving you, pain may be defied!’

‘Then in my company you may ride

And fight more battles seeking honour!’

Said she, and, thus, Gawain did render

Proud and happy in the extreme.

The brave Turkoyt, whom he did deem

His prisoner, he sent to the castle,

With his host, asking him to tell

The ladies there to honour the man.

Now, Gawain still held in his hand

His stout lance, which was yet whole,

E’en though, in racing to their goal,

The knights had charged ahead, full tilt,

Ere to the grass the one was spilt.

This lance he bore from the meadow.

While fair ladies wept to see him go.

‘He on whom our hopes were pinned

Has chosen a lady, for our sins,

Balm to his eyes, and yet one born

To be to his amorous heart a thorn,’

Lamented Queen Arnive, ‘Alas,

That ever it should come to pass

That he, with the Duchess Orgeluse,

Towards the Perilous Gorge pursues

A path that for his wounds bodes ill.’

Four hundred ladies, grieving still,

Watched him ride forth to win renown;

Yet any pain that might raise a frown

He banished, faced by the radiance

Of Orgeluse, as they did advance.

Gawain is set the challenge of the Garland

‘YOU must win me a garland,’ said she,

‘From the branch of a certain tree,

And, if you grant it me, I shall praise

That deed, for the rest of my days,

And you may ask for my love again.’

‘Madame, wherever,’ replied Gawain,

‘That tree may be, whence I may win

Such honour and bliss I may begin

Once more to speak of my passion,

In fond hopes of your fair attention,

I’ll cull the garland, unless death

Shall rob me of my every breath.’

Howe’er bright the flowery meadow,

Its light was naught beside the glow

That the Lady Orgeluse shed there.

His thoughts of her were such, no care

Or suffering troubled him at all.

Riding forth from the castle wall,

She travelled with her companion

Down the wide road they were on,

For some two miles or so, until

They came to a grove of brazil

And tamarisk trees, willed there

By Clinschor, and now in his care.

‘Where shall I find this certain tree,

And this garland, to mend for me

My happiness that is all threadbare?’

(Yet he ought to have left here there,

As happened since to many a lady).

‘I’ll show where you may prove to be

The doyen of skill and chivalry,

And demonstrate your love, to me,’

She said, and they rode o’er the plain,

Towards a cliff, and there they came

To where they both could see the tree

To grant him a garland. ‘Sir,’ said she,

‘He robbed me of my happiness,

He who tends that tree, no less.

Win me a garland, and no knight

Will have, in his fair lady’s sight,

Won such noble renown ever,

As a servitor, for true love of her.’

Thus, she spoke, Lady Orgeluse,

‘I’ll go no further. If you choose

To ride on, be it in God’s hand!

From your charger you need demand

But one great leap, from here to there;

Once he’s borne you through the air,

The Perilous Gorge you will be o’er.’

She halted on the meadow, and saw

Gawain ride onwards, without cease.

The Perilous Gorge

HE heard a torrent midst the trees

Roaring now, in the deep broad bed

It had cut, yet his journey led

Beyond it though it barred the way.

The noble warrior thrashed away

At his steed’s flanks and spurred him on.

The creature landed, his forelegs on

The far side only, and so the leap

Caused a spill; and she did weep,

The Duchess (much to your surprise?)

The tears fell fast from out her eyes.

The current too was fast and strong,

That carried Lord Gawain along,

Weighted down by all his armour,

Who sought to live a little longer,

Exerting his great strength. Then he,

Seeing a branch of a mighty tree,

That rooted in the river bank,

Seized it, ere he downwards sank.

His lance too, as it did descend,

He seized, and sought to ascend

The bank. Meanwhile Gringuljete

Still struggled in the foam as yet,

Now above it, and now below.

Gawain turned to aid him, though

The steed was driven far downstream;

He hard put to it, it would seem,

To run behind in all his armour

And now weakened even further;

Yet a whirlpool retained the steed.

He reached it, in its hour of need,

At a place where a weight of rain

Had carved a cleft in the terrain,

Cutting through the downward slope,

Such that the breach there gave hope

Of saving Gringuljete. Gawain,

Grasped him by the floating rein,

And to the shore did him advance

With judicious use of his lance.

He hauled the charger to dry ground,

Who shook himself, now safe and sound.

Girthing his horse, he counted the cost

And found his shield had not been lost.

If any there are who’ll not protest

At all his sufferings, let them rest;

He endured much, twas Love’s will;

Fair Orgeluse, she drove him still

Towards the tree, and that garland.

The thing itself was close at hand,

So well-guarded, had there been two

Gawains they would have, tis true,

Both have struggled there to gain

The garland. Yet the one Gawain

Achieved that very thing, we’ll find.

The Sabins, it was, flowed behind

His back, and a rough ride had he

Through all its perilous territory.

Howe’er radiant was her face,

That Duchess, I would shun the place,

Nor seek love on such terms as those;

I draw the line there, heaven knows!

Gawain gains a Garland from the tree

NOW, the tree, King Gramoflanz kept;

And let none imagine that he slept.

For when Gawain a branch did get,

And, breaking it, then a garland set

Upon his helm, a handsome knight,

In the prime of life, came in sight.

His proud spirit was such that he

Scorned to fight unless two or three

Opposed him, no matter the wrong

Done to him, and, proud and strong,

Shunned a joust with a lone knight

And let things rest, without a fight.

The son of King Irot, Gramoflanz,

Greeting Gawain, did thus advance.

‘Sir, I have not let this thing pass

Unseen. Had there been two alas,

To break that branch from off my tree,

And thought to call it victory,

And add to their renown today,

I would have driven them away.

Tis beneath me to fight but you.’

For that matter, on his part too,

Gawain was disinclined to fight,

Before him was an unarmed knight,

Who carried on his fist a hawk,

Twas a fine moulted sparrow-hawk,

That Itonje, Gawain’s fair sister,

Had gifted him. From Sinzester,

Came his peacock-feathered hat.

A splendid cloak he wore, and that,

Was of grass-green samite lined

With bright ermine, its cut refined,

Such that the points on either side

Brushed the ground as he did ride.

The palfrey that carried the king,

Was of middle height, not lacking

In marks of beauty, good and strong,

Of Danish stock; he rode along,

Unarmed, for he wore no sword.

‘You shield, indeed, seems badly gored,’

Said Gramoflanz, ‘there’s little there.

The Lit Marveile was your affair;

It seems you have endured, I find,

A venture which was rightly mine,

Yet Clinschor chose to set for me

A kinder precedent, while the lady,

I’m at war with, through her beauty

Has won, twould seem, love’s victory.

Alas, her disdain, and her anger

With me, it seems must last forever,

Her just cause lies in deeds long past,

For I slew her husband Cidegast,

One of a company of three.

I abducted Orgeluse, and she

Has since spurned my every offer

To obey her rule and serve her,

And my crown, and all I possess.

I held her one whole year, no less,

Subject to my pleas, yet failed

To win her love; her wrath prevailed,

To my deep sorrow. Now, tis clear,

You have her love, and so are here

To bring about my death. Had you

Brought another, if you were two,

You could have fought me, or died

For your trouble, salved your pride.

My heart is set on another love;

Since, of Terre Marveile, you prove

The lord, thereby gaining honour,

All now depends on your favour.

If you’d deliver me a kindness,

Come, aid me now, in my distress,

With a young lady, for through her

My poor heart does naught but suffer.

Of King Lot, she is the daughter,

No other girl on earth has ever

Gained such a strong hold over me;

I have her love-token, you may see

It here. Convey to that young lady

The strength of my devotion. She,

Is well-disposed, I believe, for I

Fought for her, full ready to die.

Once Orgeluse had, furiously,

Denied me love, and openly,

Any renown I won, or fame,

Aught achieved in joy or pain,

Was brought about by Itonje.

I have scarcely seen her, sadly;

But, if you’d bring solace here,

Deliver this ring, to that dear,

And most sweet, and lovely lady;

For you shall be exempt entirely

From battle here, unless you bring

A greater number to the ring,

One more or two, for what credit,

If I killed you, would I gain by it,

Or if I forced your surrender?

And then, on such terms, I’ve never

Sought to fight, nor e’er agreed.’

Gawain agrees to fight King Gurnemanz at Joflanze

‘THOUGH I’m a man equipped, indeed,

To counter aught,’ replied Gawain.

If you’ll win nor renown nor gain,

By slaying me, nor will I earn

Aught for this garland here, in turn.

What credit would accrue to me

Slaying an unarmed man? Let be.

I’ll bear your message, and the ring,

And convey your duty, telling

All the matter of your sad story.’

The King thanked Gawain, profusely.

‘If tis beneath your dignity,’

Said Gawain, ‘to fight here, tell me,

Who you are.’ ‘Think not the worse

Of me, if I should now rehearse

My name,’ the King replied, ‘Irot

Was my father, slain by King Lot,

And, thus, King Gramoflanz am I.

My spirit, that’s ensconced on high,

Decrees that I shall never fight

With one alone, ne’er a lone knight,

Whate’er the wrong he’s done to me,

Except one knight, unknown to me,

Yet highly praised, on every hand,

Such that I long to meet the man,

And, in battle, avenge my sorrow;

For his father, this fact I know,

Slew my father, treacherously,

In the act of greeting him; I see

Reason to fight, thus, in that quarter.

But now King Lot, Gawain’s father,

Is dead, and this Gawain, the son,

Many an honour he has won,

Fame no other knight can equal,

Among those of the Round Table.

The day then must surely come

When battle twixt we two is done.’

‘If you’d fight so,’ said Lord Gawain

‘To please the lady, and yet maintain

Her father did a treacherous deed,

And would slay her brother, indeed

She, if she is your love, would be

Right full of wickedness, if she

Did not oppose such on your part.

If she had the love of kin at heart,

She’d defend her father’s name,

And her brother, and shield that same,

And seek to quell your enmity.

A father-in-law’s crime can be

No adornment for a man; if you

Yourself should fail to bear a true

And lasting burden of deep shame

Attacking, thus, a dead man’s name,

His son will ensure that you do so.

Should his sister cause you scant woe,

He’ll risk his own life in the task.

Gawain am I, if you should ask!

Whate’er you claim my father’s done,

Now he is dead, address the son.

To defend him from such calumny

All the honour that's come to me

I’ll stake in battle, here and now!’

‘If you are that man, then, I avow,

Your noble nature brings me joy,

My prowess I shall thus employ

On one worthy of the honour

Of single combat; tis a favour

That I concede to you alone;

And yet, it saddens me to own

There’s that in you that pleases me.

Then, it would enhance the glory

If, both, fair ladies did invite,

As witnesses, to watch the fight;

Full fifteen hundred I might bring.

From Schastel Marveile, to the ring,

Bring forth your dazzling company;

And King Arthur too, of courtesy.

Bems, on the Korcha, in the land

Of Löver, holds his knightly band;

Your uncle can be here in a week,

His glad presence we should seek.

At the field of Joflanze, I vow,

On the sixteenth day from now,

I shall appear, to exact a toll,

For the fair garland that you stole.’

The King now asked my Lord Gawain

To accompany him, o’er the plain,

To Rosche Sabins, his castle there.

‘O’er no bridge may you now fare.’

‘I shall return the way I came,

All else I’ll do, to meet your claim.’

They pledged their word to appear

At Joflanze, the terms being clear.

He took his leave; my Lord Gawain,

Now giving Gringuljete free rein,

Far from wishing to check his steed,

Spurred onward to the gorge; indeed,

His heart was light, his venture blessed:

He sported the garland as his crest!

Gringuljete timed his leap so well,

That neither he nor his master fell.

Orgeluse rode straight to the place.

Gawain alighted, while Her Grace

Dismounted opposite on the grass.

Given all that had come to pass,

She threw herself down, at his feet,

His triumph seeming thus complete.

Orgeluse seeks Gawain’s aid

‘OH, my lord, I did ne’er deserve

That you should thus, so nobly, serve,

Such suffering should undergo.

Truly your trials oppress me so,

With such pain as a loyal woman

Must feel for so renowned a man’

‘Well, if no hidden scorn should lie

In what you say, madame, thereby,

You may retrieve your good name.

Yet you’ve proven much to blame,

If knighthood shall receive its due.

The office of the shield have you

Mocked, madame; tis one so high

That none who practise it, say I,

May mockery such as yours allow.

All that have e’er seen me, I vow,

Engaged in chivalrous deeds, agree

On my courage and ability,

Yet several times since we met,

You have said otherwise. And yet,

No matter; receive this garland now.

But madame, you must ne’er allow

Such conceits to your lips again,

Or seek to speak in such a strain.

By your fair looks, if I’m to be

The object still of your mockery,

I would rather myself remove,

And live on so, without your love.’

‘My lord,’ fair Orgeluse replied,

(At this point she wept and sighed)

‘When I tell you of the distress

That weighs upon my heart no less,

You will hold mine the greater woe.

Let all those I’ve mocked, now show

Their courtesy, by pardoning me.

No greater joy from me can flee

Than that which I lost in Cidegast,

My peerless lover, to the last!

Inspired by a wish for true honour

His renown was such that, ever,

Men acknowledged his great fame

Unmatched by any other name.

He was the fount of virtues, he

A man all unmarred by falsity,

His youth all that proves excellent.

From obscurity, he made ascent,

Unfolding, thus, towards the light,

And raised his fame to such a height

That it could be attained by none

Whose honours were but basely won;

Springing, thus, from his heart’s seed,

His glory grew so great indeed,

It o’er shadowed all those below,

As Saturn, in its course, doth go

Beyond the other planets on high.

My spouse, my paragon, for know

That I can truly call him so,

Was, like the unicorn, a creature

That proves so loyal in his nature

Maids at his death must cry their pain,

Since for love of purity he’s slain.

He was my life, and I his heart,

I lost him, and I, for my part,

A woman fraught with loss remain.

By King Gramoflanz he was slain,

From who you took the garland here.

My lord, if it truly should appear

That I have used you ill, twas so,

Because I wished by it to know

If you were worthy of my love.

Though I well know that I did prove

Offensive in some things I said,

It was but to provoke your aid.

Quench your anger now, graciously,

Forgive me, of your courtesy,

In that you are a gallant knight.

You are the gold, glowing bright,

That’s purified within the fire,

Your true spirit, purged, rises higher.

That warrior whose harm I sought,

I yet would see that fellow brought

To battle and great harm, ere long,

For he has done me mortal wrong.’

‘Unless death forestall my plan,’

Gawain replied, ‘I shall, madame,

Acquaint that king with my fury

And check his arrogance, entirely.

I have pledged my word to ride

And fight him, and then his pride

Shall suffer, when we battle there.

My lady, your part in this affair

I have pardoned. If you would now,

Without a frown upon your brow,

Be so civil as to receive my plea,

I might then counsel what would be

To your honour, as a woman quite,

And what nobility seeks of right.

We are alone; upon my honour,

Madam, grant me, now, your favour.’

‘I ne’er warm to a mail-clad arm,

She said, ‘but then I see no harm

In your claiming, at some later date,

The fair reward you’ve earned of late.

Meantime I’ll mourn your suffering

Till you are well, and seek to bring

You comfort till you’re healed anew;

I’ll up to Schastel Marveile with you.’

‘Then you’ll make me a happy man,’

And the ardent lover took her hand,

And, clasping her, helped her mount.

(She had thought him of small account,

And of such a favour most unworthy,

When she’d addressed him openly

Beside the spring, where they first met)

Gawain rode happily on, and yet

Her tears they never ceased did flow,

Till he had joined her in her woe,

And asked why she was full of care,

And in God’s name bade her forbear.

She speaks of Anfortas, Clinschor and her attempts against Gramoflanz

‘I must complain,’ she said, at last,

‘Of he who slew brave Cidegast,

Bringing my heart great woe, thereby

Where happiness had dwelt, while I

Enjoyed his love. I am not so slight

A power, that I have not that knight

Sought to trouble, as best I may,

For many a joust has come his way;

And you indeed will grant me aid,

And so, avenge me, the grief repaid

That lends the edge to all my anger.

I accepted what one king did offer,

In search of Gramoflanz’ demise,

That king most precious, in my eyes,

The lord of earth’s greatest treasure,

Service he gave in no small measure.

And with it, for my own benefit,

The merchandise, from Tabronit,

That stands yet before your gate,

Lost to all but the fortunate.

Sir, that king’s name was Anfortas,

Yet he gained little by it, alas,

For he was wounded in my service,

Instead of him finding love by this,

I was forced to seek fresh sorrow.

For Anfortas’ wound dealt me woe

As great as that which Cidegast

Had power to bring me, at the last.

Now tell me how am I, poor woman,

And loyal heart, to keep my reason,

In the face of that pain and woe?

My mind is filled with trouble so,

And almost brings me to despair,

When I think of him lying there,

Helpless, the man to whom I turned

To solace me for the harm I earned

Through the cruel loss of Cidegast,

And likewise claim revenge at last.

That rich merchandise at your gate,

How Clinschor gained it I’ll relate.

When Anfortas, who gave it me,

Renounced all bodily ecstasy,

I went in fear of being shamed,

For magic arts Clinschor has tamed,

And he can bind women and men,

With his spells; he troubles them,

All those on whom his eye doth fall.

And so, I gave to Clinschor all

My precious goods, so I might be

Left in peace; he made me agree

That I would seek love of the man

Who adventured here, twas his plan.

Whoe’er succeeded in the venture,

I must seek to gain his favour,

Yet were I viewed unfavourably,

The goods would all revert to me.

Such the terms sworn in his presence.

And as things are, then the essence

Of those terms is that we’ll share

Possession of the rich goods there.

I’d hoped that Gramoflanz would be

Destroyed by that adventure; sadly,

No such vengeance was brought about.

Had he ventured, as you did, no doubt

He would have met with equal pain,

And there been overcome, and slain.

Clinschor is both wise and subtle,

He lets me deploy my people,

For the sake of his own renown,

In deeds of chivalry, up and down,

With sword and lance, throughout the land.

Each day, all year through, I command

My folk to keep sharp lookout for

Proud Gramoflanz, and what is more,

They watch by night as well as day;

Whate’er it costs me, he must pay.

Oft they’ve fought with him, I know,

Yet not why he’s protected though

I seek his death in many a way.

Many a man serves me this day

For love, not reward or promise,

Unrequited, favouring me in this.

None e’er saw me whose service I

Could not have secured, by and by,

Except one who wears red armour.

My retinue he did promptly scatter,

Riding up to Logroys, and then,

Menacing, unhorsing my men,

Strewing them around, at leisure,

Granting me but little pleasure.

Five of my knights, gone in pursuit,

He discomfited, did there uproot,

Between Logroys and the ferry,

Delivering their mounts promptly

To the ferryman. And I rode after

The knight myself, and I did offer

Lands and person. He made clear

He had a wife whom he held dear,

Far lovelier, he claimed, than me.

Piqued, I asked who she might be.

“She is the fairest of the fair,

And is the Queen of Belrepeire,

And my own name is Parzival.

And I seek not your love, withal.

My pursuit of the Grail demands

That I meet trouble in other lands.”

And, thus he departed, angrily.

Tell me, was it so wrong of me

To offer a noble knight my love,

Seeking vengeance? By that move,

Is my love worth any the less?’

Gawain answered thus: ‘Duchess,

That man whose service you desired,

I know is by such merit inspired,

That had he sought you as his lover

Your worth in no way could suffer.’

Gawain, and fair Orgeluse likewise,

Looked deep into each other’s eyes.

Gawain seeks to maintain his anonymity at the Castle

THEY were nearing the castle again

Where our knight had met with pain,

And yet where he’d achieved success.

‘My lady,’ said he, ‘may I request,

That, within, you conceal my name.

Though the knight gave out that same,

He who rode off with Gringuljete,

I would not have it mentioned yet.

And, if they should ask it of you,

Answer that you cannot say who

Your companion is, nor his name;

He has ne’er told you that same.’

‘Since tis your wish I withhold it,’

Said she, ‘I’ll most gladly hide it.’

Gawain, and the lovely lady, turned

Towards the keep, where all had learned

Of the knight and his bold venture,

How the lion he’d sought to conquer,

Slain it, and then, in combat, brought

The Turkoyt down, so well he fought.

They rode through the meadow slowly,

Towards the landing, and the ferry,

Watched from the walls; many a knight

Came riding forth, perchance to fight,

Thought Gawain; they were mounted

On Arab steeds, this host uncounted,

Pennants flying, raised a mighty din,

As they came forth, to lead them in.

Seeing them at a distance, Gawain

Turned to the Duchess: ‘Are they fain

To attack us here?’ but she replied:

‘Clinschor’s company thus do ride

To welcome you with joy, for they

Have long awaited so fair a day;

Let it not rouse your displeasure,

Tis but happiness in full measure.’

He and Orgeluse are entertained by the ferryman

NOW Plippalinot, the ferry-master,

With his proud and lovely daughter,

Brought the ferry o’er the water.

The girl walked a long way, over

The meadow, to meet Lord Gawain,

Then greeted him, joyfully, again.

He in turn saluted her, while she

Kissed his stirrup then, gracefully,

Welcomed Orgeluse. By the bridle,

His steed she held; from the saddle

He now leapt to assist the lady,

And both went aboard the ferry,

At the vessel’s bow, a carpet

Was laid ready, and next it set

A quilt, on which, at his request,

The lady sat, by his side, to rest.

Bene, the daughter, once again

Unarmed him I’ve heard, and then,

When that onerous task was done,

Brought him a cloak, the very one

Which had served to cover the knight

When he’d lodged with them that night;

Indeed, it proved most timely now.

He received the cloak, with a bow,

Donned his own surcoat, and then

The cloak, as she went from them

Carrying his armour; the Duchess

As they sat side by side, to rest,

Could, only now, study his face.

Sweet Bene next brought them a brace

Of larks, a glass of wine, and two

White loaves on a fresh napkin, new

And white as a napkin could be,

Laying them all down carefully.

The merlin had caught, on the wing,

Those larks. They washed their hands, serving

Themselves with water. Now, Gawain

Was filled with joy, all free of pain,

Dining there with the lovely lady,

For whose sake he was full ready

To garner hardship or pleasure.

When the wine-glass she did offer,

Her lips had touched, then the thought

That he would drink there also, brought

New joy, and all his pain and sorrow

Lagged behind as his heart did borrow

Wings, and flew far ahead of him.

The sight of her sweet mouth, her skin

So fair, had chased away his care,

Wounds and woes all forgotten there.

The ladies in the castle had sight

Of all this, while many a knight

Had come down to the far shore

There to practise games of war.

Gawain thanked the ferry master

For the meal, likewise his daughter,

As did the duchess, on her part.

‘That knight I saw as I did depart

Yesterday, what became of him there?’

Asked the Duchess, ‘in that affair,

Was he beaten, did he live or die?’

‘I saw him alive today, for I

Exchanged the man for a brave steed.

Madame; if you’d wish him freed,

Let Swallow (that Queen Secundille

Once owned, then Anfortas, until

He sent the harp to you) be mine.

If amongst your goods that fine

Gilded harp, you will grant to me,

The Duke of Gowerzin goes free.’

‘This lord, who sits here’, she said,

‘Holds all the power, on that head,

And commands all the other wares,

If he so wishes. In such affairs

He must decide. If, however,

I was dear to his fond heart ever,

Then Lischois, Duke of Gowerzin,

He will ransom; I’d also win

Freedom for one who is the knight

Who commands my watch by night,

Florant of Itolac, one that I

Do value greatly; and so high

Is the value I place on that man,

As my Turkoyt, you’ll understand

That I’ll ne’er be happy, I know,

If brave Florant is full of woe.’

‘You’ll see both free ere nightfall,’

Gawain promised, ‘if that be all.’

Gawain is welcomed back to Schastel Marveile

THEY now crossed to the farther shore,

Where Gawain handed her once more

On to her palfrey. Many a knight

Received them there with true delight,

And as they turned towards the castle

Their escort, riding as if to battle,

Displayed such skills, most eagerly,

As did great honour to chivalry.

What more? Except to say Gawain,

And she, were welcomed once again

To Schastel Marveile, in a manner

To satisfy the one and the other.

Count him a lucky man that day

That such fair fortune came his way.

Arnive led him to a fine chamber,

To rest, granting him her favour,

And those skilled in medicine,

Attended to his wounds therein.

He writes to Arthur to request his presence at the duel

‘MADAME, I need a messenger.’

Said Gawain, to the Queen, later

And Arnive sent her young lady,

Who returned with a squire, manly,

And discreet, as ever a squire

Can be, to meet Gawain’s desire.

The youth swore on oath that he,

Whether all went well or badly,

Would not divulge the message to

Any other than those folks who

Were intended. And then Gawain

Sought ink and parchment, and was fain

To write a message with his own hand,

Which must be carried to that land

Called Löver; and most elegantly

He penned it; his most humble duty,

He offered to his lord, King Arthur,

And Queen Guinevere and further

Assured them of his loyalty,

And went on to say that, if he

Had attained the least fame at all,

Then it would be erased withal,

Unless they helped him, indeed,

By recalling, in his hour of need,

Those bonds of kinship and loyalty,

And bringing all their company,

To Joflanze with their ladies, fair,

And that he would meet them there,

For he must fight for justice’ sake,

And his whole honour was at stake.

He said the terms agreed further

Required of him that King Arthur

Come with all due ceremony.

He asked that each knight and lady,

Think of their loyalty towards him,

And that they thus advise the king

To do so, and enhance their honour.

He sent them his respects, moreover,

And told them of the difficulty

The duel placed him in; and lastly,

Folded the message, without a seal,

Since his known hand would reveal

Who had sent it. ‘And now delay,

No longer, come, be on your way!’

Cried Gawain, ‘the King and Queen

At Bems, by the Korcha, are seen.

Seek her early one morn, then do

Whatever the Queen tells you to.

And keep this well in mind, say naught

Of my being lord here, of this court.

Nor must you e’en say that you serve

In this place; now, my thanks deserve!’

The squire was in haste to be gone.

Yet Arnive caught him, whereupon,

She asked him where he was going.

‘Oh, Madam, I may tell you nothing,’

He cried, ‘such is the oath I swore.

God keep you! I can say no more.’

And he went his way, full loyally,

In search of that famous company.

End of Book XII of Parzival