Wolfram von Eschenbach

Parzival

Book V: The Grail Castle

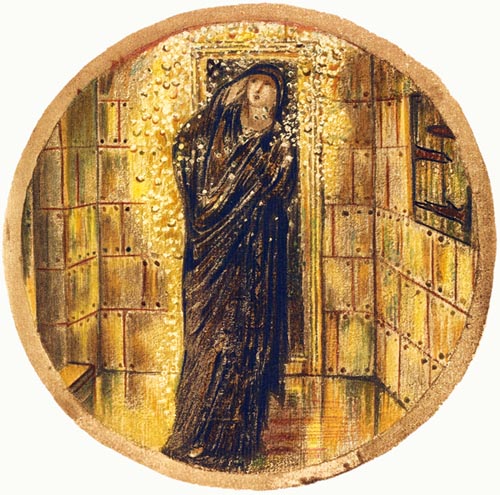

‘Golden Shower’

From The Flower Book, Sir Edward Burne-Jones (English, 1833 – 1898)

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2020 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Parzival meets the Fisherman.

- He reaches the Grail Castle of Munsalvaesche, at Michaelmas.

- Parzival is made welcome.

- He meets the Grail King (Anfortas, his maternal uncle, Frimutel’s son).

- He witnesses the Grail ritual.

- The Grail provides a cornucopian feast.

- Parzival fails to ask the vital question.

- He passes the night there.

- Parzival wakes to find the castle silent.

- He meets his cousin Sigune again and learns more.

- Parzival meets with Orilus and Lady Jeschute.

- He defeats Duke Orilus in single combat.

- Duke Orilus is the third to be sent to King Arthur’s court.

- Parzival exonerates Lady Jeschute.

- Duke Orilus rides with Lady Jeschute to Arthur’s camp.

Parzival meets the Fisherman

WHOE’ER would learn where he did go,

(Twas adventure that spurred him so),

May hear of many a wondrous thing;

Let Gahmuret’s son keep riding;

Kind people everywhere will wish

Luck to one destined for anguish,

Yet for honour and joy no less.

One fact caused him some distress,

That he was far from that woman

Of whom the books and tales say none

Was ever more virtuous or fair.

Thoughts of the Queen troubled him there,

And might have addled his wits quite

If he’d not been a steadfast knight.

His mount trailed its reins, its knees

Deep in mud, o’er fallen trees,

For no man’s hand proved its guide.

The story says no bird might glide

The distance that he rode that day;

And if my source doth not betray

His matter, the journey he made,

After his javelin Ither laid

On the meadow, when from Graharz

He reached the kingdom of Brobarz,

Was shorter by far than this affair.

Would you hear how he did fare?

He came to a lake as evening fell,

And there, upon its gentle swell,

He found some anglers in a boat

(Twas their lake) at anchor did float.

They watched as Parzival drew near,

Quite close enough to shore to hear;

One of those who was there aboard

Was so dressed had he been the lord

Of all the earth none could be finer;

All of peacock’s feathers, moreover,

Was his hat, lined, and with a band;

So Parzival asked the Fisherman,

In God’s name, of his courtesy,

To tell him where’er there might be

A place to shelter for the night,

And, sadly, he answered the knight.

‘Sir, he replied, ‘on either hand,

For thirty miles or so inland,

I know of no such habitation.

Nearby, there is a lonely mansion,

And I’d suggest you visit there,

Since there’s no other anywhere

That you could reach ere fall of night.

Pass the cliff, then turn to the right;

When you reach the wide moat, where

You have to halt, then ask them there

To lower the drawbridge anew,

And open thus the way for you.’

He took the Fisherman’s advice

And his leave. ‘If that doth suffice,

And you can find the right way there,’

Said the Fisherman, ‘I’ll take care

Of you myself this evening, and then

You may give thanks, as and when,

Regarding the treatment you win.

But take care though, as you begin;

Some paths may carry you well wide,

Far astray on the mountainside,

And I’d not wish that upon you.’

He reaches the Grail Castle of Munsalvaesche, at Michaelmas

PARZIVAL then set forth anew,

At a brisk trot, towards the right,

Until the wide moat came in sight.

And there he found the drawbridge raised.

Upon the outer walls he gazed;

Naught had been spared there, to create

A mansion, strong, immune to fate,

Towers smooth, round as from a lathe.

Unless attackers were to brave

The wind and fly there on broad wings,

It seemed secure from mortal things.

Clusters of turrets, and many a hall

Stood all about, strong stone withal.

Had all the armies in the world

Attacked headlong, banners unfurled,

For thirty years, not one defender

Had need to think of its surrender.

A page appeared now, and that same

Asked what he wished, and whence he came.

‘The Fisherman sent me here,’ he said,

‘I thanked him, and his words have led

Me to this place, with hopes I might

Find shelter gainst the coming night.

He said you the bridge would lower,

If I asked, that I might ride o’er.’

‘If twas the Fisherman, I gauge

That you are welcome,’ said the page,

‘You shall be treated with honour,

And housed in the fairest manner,

For his sake, who sent you hither.’

Then the drawbridge he did lower.

Parzival is made welcome

AND then our brave knight rode within,

Entering the long wide court, therein,

Whose green lawn had ne’er been marred

By knights a-jousting in the yard,

For none such vied, in chivalry,

Or sported there, like those we see

At Abenberg, in the meadow, where

The pennants fly, in the summer air.

It had not known, for many a day,

Bright deeds; upon it sorrow lay.

Yet Parzival was welcomed now,

Nor made to feel the woe, I vow,

For a crowd of young gentlemen

Vied to take his bridle, and then

Held his stirrup, while down he came

From his mount, and then that same

Steed removed, while knights did lead

Him to a chamber, fine indeed.

The knights unarmed him right swiftly,

Though all was done most courteously,

And they the beardless youth did honour,

Counting him rich in Fortune’s favour,

Once they’d seen his charming nature.

The young man now asked for water,

And soon the dust, acquired that day,

From hands and face he washed away,

Such that it seemed the fresh dawn light

Shone from his looks, to daze the sight,

He the image of a fine young king.

Those who thus saw to everything,

Now brought a cloak, its every fold

Bright with Arabian cloth-of-gold,

At which the handsome lad did gaze,

Donned it unlaced, and won much praise.

‘Repanse de Schoye, our fair princess,

Was wearing this herself, no less,’

The Master of the Wardrobe said,

‘She lends it to her guest instead;

As yet no clothes are cut for you

But I asked it of her, for one who

Is a man of worth, if I judge aright.’

‘May God reward you,’ said the knight,

‘If you judge right, tis well indeed,

And God rewards a kindly deed.’

They filled his cup, and drank at leisure,

Despite their grief, all shared his pleasure,

Showing him honour and esteem.

And, indeed, there was more, I deem,

Of food and drink taken, that night,

Than at Belrepeire, in its sad plight,

Ere he’d delivered that fair city.

Yet a jest caused near-enmity,

A loquacious fellow, in mock anger,

Felt free to summon this stranger,

To meet his host, and for his jest

Near lost his life; the irate guest,

Not finding his fine sword at his side

(They had placed his weapons aside)

Clenched his fist so hard the blood

Spurted from his nails in a flood,

And wet his sleeve. ‘Hold, sir!’ all cried,

‘This man must not be so denied;

Though we are sad, he is allowed

With jests to entertain our crowd;

Bear with him, as a gentleman.

You were but meant to understand

That the Fisherman is now here.

Go join him, for he doth appear

To value you; go, noble stranger,

Shake off all your weight of anger.’

He meets the Grail King (Anfortas, his maternal uncle, Frimutel’s son)

THEY climbed a stairway to a hall

Where a hundred chandeliers, all

With many a candle, shone on high,

Over their heads, as they passed by,

And many a sconce on every wall.

A hundred couches were in that hall,

With as many quilts, and on each one

Sat four companions, and every one

With ample space, and on the ground

A carpet before it, fair and round.

King Frimutel’s son could well afford

Such things, who of all this was lord.

Nor was it thought too great excess

That the three fireplaces did possess

Three square andirons of masonry,

In marble, supporting each a fiery

Burning pile of sweet aloes wood;

(Here, at Wildenberg, none would

Of such great fires e’er be aware!)

Wondrous workmanship was there.

The lord of the castle was in place,

Propped near one great fireplace.

He and ease had settled accounts,

With each other, and the founts

Of life, low in him, did scarce strive

To keep his weakened body alive.

Parzival with bright look did enter;

His host did welcome the stranger,

A host indeed, who’d sent him there;

Bade him approach, and took good care

To seat him, not leave him standing.

‘Sit close by me, to have you sitting

Far off would be to treat you rather

As some most unwelcome stranger

And not indeed as my worthy guest,’

Such was the sorrowful lord’s request.

Because of his ailment this nobleman

Maintained great fires on either hand,

And wore warm clothing, amply made,

With a sable lining and trim displayed,

On his pelisse, and the cloak above.

Their meanest fur of worth would prove,

Being of deep black flecked with grey.

On his head too he bore, that day,

A cap of the same fur, sable, bought

At great price, doubled, worn at court,

With an ornate Arabian border

That ran around its edge; moreover,

At the centre, on top, it bore

A glowing ruby without a flaw.

He witnesses the Grail ritual

THERE sat many a sombre knight,

As witnesses to a mournful sight.

A page from a doorway did advance,

Who bore in his right hand a lance,

(This rite was to evoke deep woe)

And from the steel tip blood did flow,

Ran down the shaft, as all did grieve,

Until it nigh-on reached his sleeve.

All wept throughout that lofty hall;

The folk of thirty lands might all

Mourn deeply and not realise

Such floods of tears from out their eyes.

He bore the lance around all four

High walls, then hastened out the door;

And then their tears ceased to flow,

Which had been prompted by the woe

That his sad progress did recall.

Now, if it will not tire you all,

I’ll speak of their rich ceremony,

One rendered with all due sanctity.

At the hall’s far end, Parzival saw,

There now flew open a steel door;

Through it a pair of maidens came.

Now let me tell you of those same,

Who to one worthy of being loved

Love’s payment in full had proved.

Shining clear, those ladies there,

Had each a garland on her hair,

And no other head-cover wore.

Each a gold candelabra bore.

Their long flaxen hair fell so,

It hung down in fine strands below,

And as they moved, bearing light,

The air about was gleaming bright.

And let us not ignore their dress.

The fine robes of the fair Countess

Of Tenebroc were of umber hue,

And those of her companion too,

Gathered together above the hips,

Clasped by belts with silver clips.

Then came a duchess, silently,

And her companion; of ivory,

Were the two trestles that they bore;

Their lips glowed red. Now all four

Bowed their heads, and then the pair

Set them before their master there.

They stood together, each as fair

As the other, and served with care,

And all alike these four were dressed.

And now, behold, he saw the rest,

Four more pairs of ladies, and four,

Of these fair eight, great candles bore,

While the other four brought a table

Of precious stone the sun was able

To penetrate by day, this stone

Was hyacinth-garnet, as tis known.

Long and wide it was, and the man

Who had measured it to his plan,

Had cut it most thin, so it was light.

The lord of the castle dined this night

At this, as a mark of his rich state.

Bowing their heads as one, all eight

Advanced, in order, before their lord,

And four of them, all in accord,

Set the table on those snow-white

Ivory trestles, all gleaming bright,

That had been placed there before,

Then went to join the other four.

These eight ladies wore green brocade,

Rich samite, in Azagouc made,

Green as grass, of ample fashion,

For length and breadth, in addition,

Fine belts clasped them at their waist,

Long narrow girdles, richly faced.

And each of them did also wear

A dainty garland o’er her hair.

Now two fine ladies dressed in style,

Who had journeyed many a mile,

To serve there, two fair daughters,

(Brought to court by their fathers,

The one Count Iwan of Nonel,

The other Jernis, Count of Ryl)

Bearing a pair of knives, advanced

From each of which the bright light glanced,

Keen as fish-spines, sharp as pins,

Wondrous things, on white napkins,

Fashioned of pure silver were they

Skilfully made, whetted that day

To an edge fit to cut through steel.

And these two trod upon the heel

Of four noble and faultless maids

Summoned to serve them as their aides,

Who went before the silver bright

And each one bore a gleaming light;

All six of them did thus advance.

Hear how, as if in sacred dance,

They bowed low, then bore the silver

To the stone table together,

And set it down, most gracefully,

And then returned, decorously,

To the first twelve, so that if I

Have made no error in all of my

Calculations, midst this affair,

Eighteen ladies are standing there.

Behold! Another six advance,

In dresses, cut for elegance,

One half cloth of gold, the other

A rich brocade from Niniveh.

The former six wore fair gowns too

Of costly fabrics, rich and new.

Following them, came the Princess,

Her face revealing such brightness,

To all it seemed the light of dawn.

This maid, as fair as is the morn,

Wore costly stuffs of Araby.

She bore, on green silk Achmardi,

The perfection, here, of paradise,

Root and blossom, before their eyes;

A thing it was they called the Grail,

Beside which Earth’s perfections fail.

She whom the Grail did there allow

To bear itself, bound by her vow,

Repanse de Schoye was her name.

Such was the nature of that same,

The Grail, that she who had its care

Was required, that she might it bear,

To be of perfect chastity,

Renouncing all mere falsity.

Lights before the Grail were borne;

No mean things, but bright as dawn,

Six slender vials of purest glass,

Where balsam burnt, as they did pass,

Carried by young girls, to whom she,

The princess, bowed, most courteously

When they had reached the proper place,

And they returned the bow with grace.

Loyally, the princess set the Grail

Before his lordship (here the tale

Declares that Parzival gazed intently

On the bearer, and well might he

Consider her, since he now wore

The cloak that had been hers, before.)

All seven of them when this was done

Turned and, with all due decorum,

Joined the first eighteen, while parting

Ranks, to admit the noblest, making

Twelve now on either side of her;

She made, I’m told, a wondrous picture,

The maid with the crown, standing there.

The Grail provides a cornucopian feast

CHAMBERLAINS, who had in their care

Golden bowls, were now assigned

One to every four knights, I find,

Who were seated within that hall,

Pages with towels at their call.

What luxury was there displayed!

A hundred tables too were laid,

One before each group of four,

And pure white tablecloths each bore.

The host, one crippled in his pride,

Washed his hands and, at his side,

So Parzival did also, which done

There hastened to them a count’s son,

Who offered them towels graciously,

Presenting them on bended knee.

There were pages, designated

To each table there, who waited

On those seated. While one pair

Knelt and carved the other there

Brought the food and drink and saw

To the diner’s needs. I’ll say more;

Four wheeled tables had been set

With many a precious gold goblet,

One for each knight sat in the hall.

Each one they drew along a wall,

And knights there would reach out a hand,

And on their board the cup would stand,

Until a clerk who owned the task

Of gathering them in again, at last,

After the supper, counted them in.

On further matters I’ll here begin.

A hundred pages received the bread,

The loaves on which this gathering fed,

In white napkins, held respectfully

Before the Grail, then, graciously,

Moved together, then fanned out,

And handed all the loaves about.

Now I am told, and I tell you

On oath, and ask it of you too,

So if I err, you’ll err with me,

That if some other had equally

Stretched out a hand before the Grail,

Whate’er they looked for, without fail,

Would be there, ready and to hand,

Every costly dish you understand,

Whether they sought for hot or cold,

For flavours new, or flavours old,

The meat of creatures wild or tamed:

‘There ne’er was such as you have named!’

Many will feel the need to say,

But tis ill-temper they display,

For the Grail was the fruit of grace,

The world’s sweetness in one place,

And not far short, it thus did prove,

Of what men say of Heaven above.

In tiny vessels of pure gold

That they before the Grail did hold,

They received their pickle or sauce,

Salt and pepper to suit each course.

The frugal man and the glutton too

Had what each man thought his due,

Served with gracious ceremony.

And whate’er the wine was that he

Desired, when he held out his cup,

Ruby, mulberry, once raised up,

He found it then, or red or pale,

Brimming, by virtue of the Grail.

For they partook that company

Of the Grail’s hospitality.

Parzival fails to ask the vital question

PARZIVAL marked what did befall,

The wealth and wonder of it all,

Yet true to Gurnemanz’ direction,

He asked not a single question.

‘The prince of Graharz counselled me,

And twas with true sincerity,

Against my questioning freely.

If I'd stayed, and it may well be,

As long as I did with the prince,

I would have learned long since,

How matters stand in this place.’

While he mused there, bearing apace,

A sword, its sheath worth no doubt

A thousand marks, or thereabout,

Whose hilt a precious ruby bore,

Came a page, and handed his lord

The weapon, a sharp blade indeed,

One fit for many a wondrous deed.

The lord bestowed it on his guest.

‘Sir, in battle, against the best,

Many a time I bore this sword,

Ere I was crippled by the Lord.

Let this gift my amends now be

For the lack of hospitality

You may have suffered at this court;

Twill stand you in good stead; in short,

Whene’er that blade’s put to the test

Twill serve you well, against the rest.’

Woe, that he asked no question then!

Hear how that pains me once again.

The sword was given for good reason,

That Parzival might ask a question.

For his gentle host, I breathe a sigh,

Maimed by an edict from on high,

Which a question would rid him of.

Sufficient have we heard thereof.

Those pages ordained so to do,

Removed the boards, and not a few,

Once the cups were gathered in.

And then those ladies did begin,

The princess first, to rehearse

Their tasks again, but in reverse,

For she was assigned to the Grail,

And gracefully, so runs the tale,

Bowing to their lord once more

And Parzival, back through the door

The maids bore all that they had brought,

With such ceremony, to the court.

As they went, Parzival gazed after,

And on a bed, within a chamber,

Ere its door was closed once more,

The handsomest old man he saw,

That he had e’er heard of, or seen;

His hair it was more silver e’en

Than hoar-frost, so I do attest,

Nor do I seek but to impress.

As to who that old man might be,

Later you’ll learn all his story,

The lord’s names, and his castles too,

And lands; when tis time so to do,

I’ll tell it, with authority,

Nor thwart your curiosity.

You’ll behold the straight bowstring,

No slackened bow, for here’s the thing,

The strung bow is my metaphor;

Its action’s swift, and yet, be sure,

The arrow it lets fly is swifter,

So its aim must be the straighter.

The bowstring fires a straight story?

Then it brings the teller glory;

When the arrow’s flight’s untrue,

The teller works deceit on you.

A well-strung bow the string is straight,

(Except when drawn) yet if one’s fate

Is but to fire a tale that’s bound

To weary folk, that flies around

In one ear, and out the other,

And no lodgement doth discover,

Tis then a waste of all one’s labour;

Drawing the string to find disfavour.

One might as well clear one’s throat

And tell the tale to an old he-goat,

Or a tree-stump that lacks all sense;

Twould prove a better audience.

He passes the night there

I shall indeed speak further though

Of those people; so full of woe,

That where Parzival had ridden

None to the dance were bidden

Nor the joust, none ever sought

Entertainment at that sad court.

Where’er there are folk even those

Of humble station hide their woes,

And seek out many a pleasure,

And there was both wealth and leisure,

At this court, as you have seen.

‘Your bed here for the night has been

Prepared,’ the host said to his guest,

‘If you are tired, please seek your rest.’

Now, as they part, I should lament,

For harm will come and discontent.

Parzival rose from where he sat,

And set his feet upon the mat.

His host wished him goodnight, then

The knights, gathering round again,

Lead him swiftly to his chamber,

Richly-furnished and moreover

Adorned with a great bed, so fine

I’m irked by this poverty of mine,

Since earth doth bear such opulence;

Poverty had been driven thence.

Across it a silk coverlet lay,

And such a gleam did it display,

The fabric seemed almost alight.

Parzival thanked each noble knight,

Dispatching them to take their rest,

With but the one bed for their guest;

And so they took their leave, but now

Further attention must he allow.

The lights and his fair glowing face

Vied with each other in that place,

In shedding brilliance, how could day

Be brighter than that room, I say?

The couch, at the foot of his bed,

Was by a splendid quilt o’er-spread;

He sat there; pages came in sight,

And from his legs, all gleaming white,

Swiftly removed his boots and hose,

And stripped him of his other clothes.

Such handsome lads they were! What more?

Young maids, of whom there were four,

Entered, whose duty was to see,

That he’d been cared for graciously,

And that his bed was to his taste,

And naught attended to in haste.

Before each a page bore a light,

Candles burning clear and bright,

So the tale tells; brave Parzival

Dived under the coverlet withal.

He won a race with haste indeed,

Yet a swift glimpse, so fate decreed,

Of his white body met their eyes,

Ere he’d recovered from his surprise,

While the thoughts of his red lips,

His youthful form, now in eclipse,

His face where not one hair yet grew,

Caused not one flutter but a few.

‘You must not slumber yet awhile,’

Said the maids, as they did file

Past the bed; in her hands one bore

A flask of some sweet wine, he saw,

Another a mulberry cordial,

A third brought mead; the last of all,

On a napkin that dazzled his eyes,

Such fruit as grows in paradise.

The fourth knelt before him then,

And though, the most kindly of men,

He bade her be seated, she said:

‘Yet let me be, for were I led

So to do then I could not serve

In the way I ought, and you deserve.’

He spoke with them pleasantly,

Drank a little, then presently

They took their leave of him, and went.

Parzival lay down, most content,

And the pages set the candlesticks

On the carpet, and trimmed the wicks,

And seeing him asleep, they left.

Yet of company he was not bereft:

Toilsome struggles filled his dreams,

Future sorrows sent forth, it seems,

Their harbingers as he lay asleep,

Such that his anguish was as deep

As his mother’s was for Gahmuret;

With woeful dreams she too had met.

The quilting of Parzival’s dream

Was joined and stitched at the seam,

By sword-tips and lance-points; there,

In sleep, twas but a grim affair,

Pain and distress did interlace

With thrusts delivered at full pace.

Death he’d have been glad to suffer

Far more than thirty times over

When awake than bear with all this

Disquiet, now robbing him of bliss.

Parzival wakes to find the castle silent

FROM this oppression he awoke,

His every limb the sweat did soak,

As through his window shone the sun.

‘Where are the pages? Nary a one

Is in attendance here!’ he cried.

‘Am I my clothes to be denied?’

With such thoughts lingering then

He turned about, and slept again.

No one spoke, none made a sound.

All were in hiding, I’ll be bound.

Mid-morning, he once more awoke

Yet all was silent, still none spoke.

There lay on the floor, by his armour,

Two swords, one was that of Ither

Of Gahaviez, forged in that land,

The other his host set in his hand.

‘Alas, what means all this?’ he asked,

‘It seems, indeed, that I am tasked

With dressing and arming alone.

Such trouble in my sleep was sown,

I fancy there’s much toil in store,

Now I am full awake once more.

If this realm’s lord does now demand

Aid from attack, then his command

I shall be happy to obey,

Also, most faithfully, this day,

That of the lady who lent me

Her new mantle, so graciously.

If she’d take me as her servitor,

It would be fitting, although more

For her own sake than any love,

Since Condwiramurs I do approve,

A wife as radiant as is she,

Or more so, thus it seems to me.’

Parzival did what he had to do;

He dressed and armed himself anew,

From head to heels, so as to fight

As doth become a valiant knight,

And both the swords he girded on,

Then out the doorway he was gone,

And found his steed tethered where

His shield and lance stood, by the stair.

This was as he wished, but, before

He mounted, he oped many a door

Of that stronghold seeking out

Its denizens with many a shout,

But to his boundless confusion

He saw or heard, not one person.

With indignation, he now sought

The place where, amidst the court,

He’d dismounted the day before,

There the morning dew, and more

The grass and earth, had been marred

By trampling hooves. About the yard,

Shouting loudly, the young man ran,

Then to his mount, and thus began

To ride forth, and he found the gate

Open wide, and saw there, of late,

Many a steed had been ridden by.

He waited not, went out thereby

And crossed the drawbridge at pace.

A page, hidden but for his face,

Dragged on a cable so sharply,

It all but toppled them wholly,

Into the moat, he and his horse.

Parzival looked back, of course,

In hopes of discovering more.

‘Go, and be damned, a fool for sure,

Where’er the sun doth light your way!

Why had you not the wits, I say,

To ask the question of my lord?

Lost is your wondrous reward!’

Parzival begged that he might know

All he meant, yet it ended so

Without an answer. Howe’er he called,

The page upon the gate’s bar hauled,

As if in dream, and slammed it shut.

For our brave knight this proved all but

A disaster, in its suddenness,

Snatching from him all happiness;

Joy had vanished without a trace.

When he’d chanced upon the place,

And saw the Grail, a single throw

Was his, for either joy or woe,

A cast of the eyes, not dice, or hand;

Trouble before him now did stand,

Rousing him to wakefulness, yet

He with but little woe had met

Thus far, had known little sorrow

Such as he might find the morrow.

He meets his cousin Sigune again and learns more

PARZIVAL now pursued the trail,

Following hard, so says the tale,

Thinking: ‘The men ahead of me

Are no doubt fighting, manfully,

In their good master’s cause this day.

If they so wish, their martial array

Would profit from my being there,

And I should not prove lacking, where

The fight seemed desperate, but I

Would stand by them and, thereby,

Pay for that supper, and this blade,

The gift of which their lord has made,

To one who had deserved it not.

Think they cowardice is my lot?’

Thus he, who was the opposite

Of base, followed what was writ

In hoofprints on the dust ahead,

Noting the marks there he read.

How his departure from that place

Saddens me! Sorrow I embrace.

But now the tale grows stranger.

For the tracks grew ever fainter,

Those ahead had soon dispersed.

Thus, the trail they had rehearsed

Once broad and clear, now grew dim,

Till their way ahead evaded him.

This young man was soon to learn

All that pain and woe doth earn.

Soon the warrior’s ear was bent

On a woman’s voice, in sad lament.

The grass was still drenched with dew;

Before him there appeared to view

A maid who sat by a linden tree,

A slave to her own fidelity.

In her arms a dead knight lay,

The corpse embalmed, and I’d say

That any who saw her sitting there,

And felt not pity at her despair,

Lacks the milk of human kindness.

‘Tis sad to witness your distress.’

Said Parzival approaching her,

And then his aid did offer her.

By his voice she knew the man:

‘You’re Parzival! That maid I am,

Whom you found grieving earlier,

She who told you who you were,

My maternal aunt’s your mother,

You have no reason to be other

Than proud that you are kin to me,

For she’s the flower of modesty,

That needs no help from morning dew,

To shine so brightly. God bless you,

For showing pity for my friend;

A lance-thrust brought about his end.

And here I hold his body still,

Judge of my sorrow that God’s will

A longer life would not grant him.

For all the virtues lived within him.

His dying, it tormented me so,

And ever since has been my woe;

As day has followed day, so I

Have found new cause to weep and sigh.’

‘Alas, is this Sigune? Madame,

You who informed me who I am,

Where are your red lips and where

Your brown tresses? Your head is bare.

When in the forest of Brizljan

I saw you there, I, another man,

You were fair despite your woe.

Your colour and your health also,

You have lost. Grim company,

As you have here, would trouble me

If it were mine. Come, let us plan

How best to bury this dead man.’

(Hear more of this maid’s fidelity:

For such thoughts as another lady,

Lunete, once drew upon, to her

Were ill, for that Lunete, further,

Said: ‘Let him live, the villain who

Did slay your husband, and to you

Make amends.’ Sigune desired

No amends, unlike women mired

In disloyalty, and there are many,

Though, here, I’ll not mention any.)

The tears that from her eyes bedewed

Her clothes were ever there renewed,

Yet she thanked him, mournfully,

And asked him how he came to be

In that place: ‘Tis true wilderness,

Nor should you here seek ingress,

For great harm befalls the stranger;

I have heard, and seen moreover,

That many here must lost their lives,

In armed combat; no warrior thrives;

Turn back from this road, sir knight.

Now say where you passed the night.’

‘A castle back there, a mile or more,

One finer than any I e’er saw,

In splendour and magnificence,

From that place I issued hence.’

‘You should not be so swift to cheat

Such trusting people as you meet,’

She cried: ‘Here you are a stranger!

Crossing the forest in this manner

Would have proved too much for you.

Timber nor stone, and I speak true,

Has been cut from this harsh ground

For more than thirty miles around

To build a dwelling; none decreed,

None was brought about, indeed,

But for one single castle, ever,

One place rich in earthly splendour.

If a man sought, with firm intent

To find it, he’d know discontent.

He’d find it not, though many men

Attempt that very thing; yet when

Someone is meant to see that keep,

It comes about as though in sleep.

I deem that you know not its name.

Munsalvaesche they call that same,

And the wide realm that serves it all,

Terre de Salvaesche, they do call.

It was bequeathed by Titurel

To his fair son, King Frimutel,

Such was that brave warrior’s name,

Many the laurels, great the fame,

He did win with his mighty hand,

Until Love had him join the band

Of servitors and die while jousting.

He left four noble children living,

Of whom three, for all their birth,

Now live in misery on this earth,

The fourth in humble poverty,

In God’s name, a penitent he.

The name he bears is Trevrizent.

Anfortas his brother, doth present

A sorry picture, for, understand,

He cannot walk or even stand,

He can ne’er lie down, nor ride,

But leans, and so must e’er abide.

Of Munsalvaesche he is the lord,

And misfortune doth him accord

Its company, decreed on high.

If you that mansion had come nigh,

And found that woeful company

Then that sad lord had been set free

From all the suffering he has borne

Many a year, both night and morn.’

‘I saw great wonders there, he said,

And many a fair lady, nobly bred.’

This our Welshman told the maiden.

And she replied: ‘Come, tell me then,

Saw you the Grail and the master

Bereft of joy? And what news after?

If he was freed from agony,

Praise on your heaven-blessed journey,

And joy to you, for you shall be

High over all that is but earthly,

All that the sky above doth cover;

Every tame, every wild, creature

Shall serve you, for true majesty

Is yours without limit, endlessly.

If aught could bring me joy,’ she said,

‘Twould be this one thing, that it led

To that man of sorrows being free

Of his living death; infirmity

Makes his existence such, I say.

Yet if you helped him, on a day,

You’ve earned high praise; the noble sword,

At your waist, was borne by that lord.

Knowing the secret of the blade,

You may fight yet be unafraid.

Its fashioning, its edge so true,

To high-born Trebuchet is due.

By Karnant there flows a spring,

That gave its name, ‘Lac’, to a king.

A single blow the sword may make,

But on the second blow will break.

It may be rendered whole again,

If that far stream it can regain;

Go take the shattered weapon back

To the spring whose name is Lac,

Yet only draw its water where

Beneath the rock it rises there,

Before tis lit by light of dawn.

Take the blade where it was born;

If the fragments of the sword

Have not been scattered far abroad,

If they are then pieced together,

Once they’re wetted by the water,

Their edges melding, then the blade

Will be as one whole sword remade,

And twill be stronger than before,

Its patterned surface gleam the more.

A magic spell it needs, you’ll find,

Though I fear you’ve left that behind.

If such your lips have learned to utter,

Good luck will follow you forever,

And wax within you, and bear seed.

All the wondrous things indeed,

Dear cousin, you have ever known

Will be at your command, your throne

Shall be on high, and you shall wear

A crown of bliss in reigning there.

You shall have all, and know no dearth,

All one might wish for on this earth.

None will be held in such honour

As to vie with you in splendour,

If you but asked the question there.’

‘I asked no question, that I’ll swear.’

‘Woe, that I have him in my sight,

The man who asked it not outright!

You witnessed such great wonders then,

And yet sought not to ask it, when

In the clear presence of the Grail!

You saw it all, and still did fail,

Those faultless ladies, Garschiloye,

And the noble Repanse de Schoye,

The sharp silver, the bloody lance.

Hear then my sharp remonstrance!

What drove you to greet me here?

A base man, and accursed, I fear,

Revealing a wolf’s venomous

Fangs, once the gall’s poisonous

Canker took deep root in you,

And, marring your true being, grew.

You should have shown deep compassion

For one whom God, in wondrous fashion,

Has visited with infirmity,

And asked about his ills, in pity.

You live, and yet to grace are dead.’

‘Cousin, be kind to me,’ he said,

‘If I’ve done wrong, I’ll make amends.’

‘You are not asked to make amends,’

Replied the maid, ‘I know, right well,

At Munsalvaesche it so befell

Your knightly honour fled away,

True worth, from you, that very day.

This the last word you’ll have of me.’

Thus the knight departed, slowly.

Parzival meets with Orilus and Lady Jeschute

INDEED, it caused him great remorse,

Our Parzival, that, in the course

Of his visit to that stricken king,

He’d failed to ask a single thing.

Thanks to the heat, and his regret,

His body soon was bathed in sweat;

His helm he unlaced, swiftly, there,

Untying his ventail, to feel the air,

And, under all the dust, his skin

Was thus revealed, bright within.

He carried the helmet in his hand.

A fresh trail led across the land,

For ahead of him a steed had gone,

And a nag, not a horseshoe on.

Now this sad palfrey bore a lady,

Along whose trail he rode, and he

Her and her mount soon decried,

The nag such that, through its hide,

Every rib you might have counted

On the creature, ere you mounted,

Its coat as white as ermine there,

Its halter a poor lime-bark affair;

Its mane hung down to the ground

Its eyes deep-set, the sockets round

And large; the lady’s wretched mount

Seemed altogether of small account,

Jaded and neglected, moreover

Oft afflicted with sharp hunger,

Such that it looked dry as tinder.

A wonder it could even stagger;

It was ridden by a lady

Unused to grooming, certainly.

It bore a saddle with its harness,

A narrow one, in sad undress;

From it the bells had all been torn,

The saddle-bow ruined and worn,

And much else it lacked indeed,

Her sorry long-suffering steed.

The sorrowful lady’s surcingle

Was a mere rope, but a single

Strand, unsuited to her rank,

And brambles, on every bank,

Reaching down, had often torn

Her tattered shift with branch and thorn.

Where’er it had been pulled apart,

Knotted strings, with seeming art,

Tied it, yet, beneath, there shone

Her skin far whiter than a swan.

Naught but a net of rags she wore,

Dazzling whiteness Parzival saw,

Where scant privacy she’d won;

Elsewhere she’d suffered from the sun.

Whichever side you’d come at her,

It would have been free of cover;

(No overdressed peasant went there,

In places she was well-nigh bare).

Her lips were crimson, nonetheless,

Their colour bright as fire’s excess.

Trust me, kind folk, twas undeserved

The treatment with which she was served;

Mindful of feminine virtue,

She was a woman good and true.

And the tale of poverty I’ve told?

Well I’d take her like, twentyfold,

Despite all her impoverished show,

Rather than some women I know,

Well-dressed as they are; she is fine

Just as she is, to these eyes of mine.

When Parzival uttered his greeting,

She knew him, at once, on meeting.

He was the handsomest anywhere,

The lad from that previous affair.

‘I’ve seen you before, to my woe,

Yet may God treat you better though,

And grant you more, assuredly,

Than ever you deserve from me,

All happiness, and honour too.

For this all came of meeting you,

My clothes much poorer, as you see,

Than when you last accosted me.

Had you not troubled me, in fact,

My good name was as yet intact.’

Parzival tried the calm approach:

‘Consider, ma’am, ere you reproach

Me, ever since I took the shield,

And I to knightly ways did yield,

No other woman I could name

Has e’er, by me, been put to shame.

Such would have dishonoured me;

While you have all my sympathy.’

The lady wept as on she rode,

Upon her breasts she bestowed

Tears like dew, those breasts all smooth,

As if turned upon a lathe, imbued

With whiteness, rounded and set high;

No man was e’er so skilled, say I,

That he could turn two shapelier.

Fair was she, as he gazed on her,

And so he could not but feel pity.

She covered herself, in modesty,

With arms and hands, from Parzival.

‘Here is my surcoat, ma’am, withal,

Drape it about to good effect,

I offer it with sincere respect.’

‘E’en if my future happiness

Depended on it, nonetheless,

I would not seek to touch the thing.

If you’d save us both from dying,

Then ride some way apart from me;

Tis not for myself I’d be sorry,

Tis your death I fear.’ ‘Dear lady,

What man will prove our enemy?

The Lord granted me strength, and should

A whole army demand our blood,

I’m ready to defend us now.’

‘He’s a noble warrior, I avow,’

She answered, ‘one so full of fight,

Were you yourself six times the knight,

You’d be well occupied. Your riding

So close, tis not to my liking,

For I was once that brave knight’s wife,

But thus neglected, now my life

Is but a serving maid’s or worse;

Thus, his anger he does rehearse.’

‘Who else is with your husband here?

He asked, ‘Were I to yield to fear,

And go, I know you’d not approve.

I’d gladly die ere I would move

For such as him; perish the day

That sees me scurrying away!’

‘He has none with him but for me,’

Declared the barely-covered lady,

(Though but the tattered skein, and all

The knotted tangle therewithal,

Was whole, in her humility,

She was the flower of purity.

True goodness perfect and unmarred,

A maid to cherish, and to guard)

‘But scant assurance that supplies,

Whate’er the tactics you devise.’

He defeats Duke Orilus in single combat

PARZIVAL fastened his ventail,

Adjusted his helm and chain-mail,

Till he saw well enough ahead;

Meanwhile his mount dipped its head,

Towards the palfrey, gave a whinny,

And Orilus turned around swiftly,

(He it was who was riding slowly,

Ahead of Parzival and the lady)

To see who had joined here there.

Wheeling his mount for this affair,

Angrily spurring the horse clear

Of the trail, the Duke did appear

Poised for battle, and well-prepared

To joust with any man who dared.

From Gaheviez came his lance,

Its paint his blazon did advance;

His helm was from Trebuchet’s hand;

In Toledo, King Kaylet’s land,

His shield was wrought, its steel rim,

And solid boss, protecting him.

At Alexandria, in heathendom,

The costly silk there was spun

Woven into that rich brocade

That the coat and tabard made

Which this proud nobleman now wore.

The chain-mail that his charger bore

At Tenebroc was forged, his pride

Drove him to flatter either side

With a fine brocade spreading

Over the horse’s steel covering.

Greaves, mail-cap, mail-shirt there

Were splendid and yet light to wear,

And he was armed that fearless man

In knee-pieces from Bealzenan,

Anjou’s capital (the lady,

Who followed him dejectedly,

She was dressed quite otherwise,

Lacking the means for such a guise).

From Soissons came his fine breastplate;

His warhorse had been won of late,

At joust, by his brother Lahelin,

Who had then gifted him his win;

And Lahelin did from Brumbane

De Salvaesche that steed obtain.

The brave combatants were well-paired,

Parzival was as well prepared,

As Duke Orilus de Lalander;

He rode to meet that commander,

On whose shield there appeared

A life-like dragon; another reared

From his helm now laced for war.

On his housings there were more,

Tiny golden dragons, and then,

On his surcoat, were more again,

Set with gemstones and, likewise,

Each one had rubies for its eyes.

Each warrior rode a curving course

Before engaging; spurred his horse

Then charged, with no challenge given;

By no treaty was that forbidden.

Following their first bold advance,

Showers of splinters from each lance

Flew high in the air. I’d boast if I

Saw such a joust with my own eye;

Perchance no finer has been seen.

Jeschute thought she’d never seen

A fiercer, watching with alarm,

For she wished neither hero harm.

Both their steeds were bathed in sweat,

As, seeking victory, those men met.

Sparks from each man’s helm and sword,

Lighting the scene, scattered abroad;

And whate’er the outcome was to be,

Two brave men struggled valiantly.

Though their steeds turned at a word,

Towards each other they yet spurred,

Nor did the gleaming swords e’er rest;

Parzival bravest, I’d suggest;

A hundred dragons, if but one man,

Were attacking him, on every hand!

The dragon on Duke Orilus’ helm

Parzival sought to overwhelm.

That brave dragon soon felt a wound,

And wound was added now to wound,

As bright gems scattered from the foe,

Catching the light as they did so.

All this was on horseback not on foot.

With blades that dealt cut after cut,

They fought for Lady Jeschute’s favour,

Time after time they crashed together,

Those steadfast warriors, at each blow

Steel mail-rings flying, above, below;

They showed all their strength and skill,

I trust you’ll agree, with dauntless will.

I’ll tell you why the Duke felt anger.

His wife had been forced to suffer

The coarse attentions of this man;

While he was her lawful guardian,

And looked to him for protection.

He thought that she’d lost affection

For him, and then brought dishonour

On her name, by taking another;

He’d made her error his concern.

Such dire punishment did she earn

No women e’er endured a harsher,

Short of death; yet in this matter

Jeschute was wholly innocent.

Now, free from any man’s dissent,

The Duke could withdraw his favour

From his spouse, now and whenever

He so pleased, none could prevent it;

Wives must do as spouses permit.

Parzival, was demanding, now,

At sword-point, that he should allow

His Jeschute to return to favour.

Till now I have heard none other

Than kind words used thus to sue;

Here were naught but swords in view.

As I see it, both men were right.

The Duke had cause, so did the knight.

He who makes the crooked and straight,

May He avert a tragic fate,

Since they strike at one another

So fiercely as to harm each other.

The joust reached fresh intensity,

Each man seeking his own glory.

Duke Orilus de Lalander fought

With skill; I doubt that any court

Saw one of such experience.

He possessed both knowledge and strength,

Known to fame on many a field,

And thought to make Parzival yield.

Relying on his might, he clasped

His arms about the knight, who grasped

The Duke, in turn, and jerked him out

Of the saddle, swung him about,

Tucked under his arm like a sheaf

Of oats, granting him no relief,

Leapt from his horse and, forcefully,

Thrust him against a fallen tree.

The Duke, his downfall near complete,

Was forced to countenance defeat.

‘You shall pay in greater measure

For inflicting your displeasure

On one so fair,’ cried Parzival.

‘Unless to favour you now recall

This lady, you are lost indeed!’

‘Not so fast, nor shall I concede.

You have not forced me so to do.’

Cried Orilus; Parzival strove anew,

And clasped Duke Orilus so tight

A shower of blood drenched that knight,

Forth from his vizor it did pour,

Forced now to do the will and more

Of Parzival, fearing for his life.

Here was an end to all their strife.

‘Alas, bold warrior, when have I

Done aught decreeing I must die?’

He asked of Parzival. ‘Live then,

If you’ll return your wife again

To favour.’ Parzival replied.

‘That I will not! For she has lied,

A grievous wrong she did to me.

Once rich in virtue, yet thereafter

She has fashioned rare disaster.

Yet I’ll perform aught else you wish,

If you’ll grant me my life, though this

God granted to me long ago,

Yet now your mighty sword is so

Like the Archangel’s, I, this hour

Must owe my life to your power.’

So spoke the prince, now grown wise:

‘I’ll buy life royally; your prize,

If you refrain from slaying me,

One of two mighty lands shall be;

Both these my brother holds in sway;

Take which realm you wish, this day.

He loves me well; he’ll ransom me,

Bound by the terms we both agree.

And, in fee, my duchy I’ll hold

From you, thus, ere the day is old,

I’ll add to your wealth and honour.

But, exempt me, brave warrior,

From readmitting to my favour

This woman here; ask whatever

Else of me, you wish, that will serve

To bring you that which you deserve.

Whatever else may prove my fate,

I cannot with dishonour mate.’

Duke Orilus is the third to be sent to King Arthur’s court

‘LANDS and people, wealth, and all,

Avail you not,’ said Parzival,

‘Except you pledge your word to me

To ride to Britain, where you’ll see

At Arthur’s court a fair maiden,

Who by a certain man was beaten,

Vengeance on whom I’ll not forego,

Unless the lady commands it so.

To her, then, your person render,

And of my fond regard assure her,

Or you may stay here and be slain!

To Arthur, and his Queen, be fain

To speak my loyal compliments,

And ask them, of their fair intent,

To reward my services, and then

Make their amends to the maiden

For the blows that she received;

For, failing this, be not deceived,

You’ll leave this place on a bier.

And I would see this lady, here,

Reconciled, full soon, with you,

And restored to your favour too.

Turn my words to deeds; so, vow;

Give me your word, here and now.’

‘If gifts won’t do it,’ said Orilus

Then I shall do that which I must,

As you demand, for I wish to live.’

Meanwhile Lady Jeschute dared give

No aid to her spouse for fear of him,

And yet was sorry indeed for him.

Since he’d promised her his favour,

Parzival had him rise, with honour.

‘Madam,’ said the defeated knight,

‘Since I was conquered in the fight,

And that defeat was for your sake,

Come and be kissed; I must make

Light of the blow to my renown,

Received through you; ne’er a frown;

We’ll not be by anger riven,

Let the whole thing be forgiven.’

The lady slipped from her palfrey

To the grass, ran to him swiftly

And, though the blood from his nose

Had dyed his mouth, heaven knows,

She kissed him thus, at his command.

Parzival exonerates Lady Jeschute

THEN the two knights and the lady

Rode to a hermit’s cell, promptly,

Carved out nearby, in a cliff-face;

And Parzival saw, in that place,

A reliquary, as they did advance,

And there, beside it, a painted lance

Was propped. Trevrizent was the name

Of the hermit, absent from that same.

Parzival did a good deed then,

He took the relics and swore on them,

Himself administering his oath,

Before the lord and lady both:

‘If I have worth (and whether I do

Or not, those seeing that I pursue

The way of the shield, will place me

Among the ranks of chivalry;

And then the office of the shield

Tells us the virtue it doth yield

Has won it great renown alway,

And its name is honoured today)

May I forever in this life know

Disgrace, all my honour brought low,

(And let my wealth stand surety

In the eyes of Him who over me

Stands highest in power indeed;

The Lord, according to my creed)

If what I swear should prove untrue:

(May I be damned in this life too

As well as the next, by His power,

And suffer for it this very hour)

I mean, if she did aught amiss,

When I chanced, in being remiss,

To tear her brooch from her, there,

And her gold ring away did bear.

I was no grown man, but a fool,

Not wise enough himself to rule.

Weeping, bathed in perspiration,

She suffered much, in that station,

Enduring wretchedness. I say

That she is innocent; and may

My honour, and my hope of bliss,

Stand as my surety in this:

My true oath seeks not to deceive.

She shall be innocent, by your leave!

Here! I return the ring. By chance,

I lost the brooch, through ignorance.’

Accepting the thing, the good knight,

Wiping the blood earned in the fight

From his lips, kissed his heart’s joy,

Then his broad surcoat did employ,

Though its fine brocade was torn

By the blows that it had borne,

In hiding his darling’s nakedness.

He replaced her ring. I confess,

I ne’er saw a lovely lady wear

A tabard so torn, nor an affair

Where such tears as theirs were shed;

Nor lances broken, with such ado;

It seems to me two fools would do

Better at tourney if such were staged.

The lady’s woes were thus assuaged.

Turning to Parzival once more,

The Duke said: ‘Knight, the oath you swore

So freely brings much happiness

And little sorrow, I must confess.

Defeat in battle brings joy again,

And that joy doth ease my pain,

For I may make amends with honour,

To her I banished from my favour.

Twas I left that sweet woman alone;

What could she do there on her own,

To thwart advances? Then I thought,

Since your good looks she did report,

It must have led to something more;

Now, God reward you, her I adore

Is cleared of infidelity.

I failed to treat her with courtesy,

In riding forth to that borderland,

Nigh the forest of Brizljan.’

Parzival, so the tale does tell,

Took with him from the hermit’s cell

The lance of Troyes, which had been

Left there, by Dodines’ brother (I mean

Taurian the Wild) forgotten there.

Now, the warriors, how and where

Will these two seek to pass the night,

Their shattered shields, marred in the fight,

And beaten helms, hacked and torn?

Where will this pair be, ere the morn?

Parzival took leave of the lady,

And her lover, upon which he,

The Duke, now wiser, suggested

Parzival would be more rested

If he joined him beside his fire,

But such was not the knight’s desire

Howe’er he pressed and, finally,

The two men parted company.

The story says that Orilus

Repaired to his pavilion thus,

Where his people were, and they

Were overjoyed, on that fair day,

To see him favour the Duchess,

And she so filled with happiness.

At once they unarmed their master,

Who washed the blood, thereafter,

And all the dust from his body.

And then he led the graceful lady

To their couch, while baths were filled.

There Jeschute, anxieties stilled,

Lay beside her lover in tears,

Not of sorrow, roused by fears,

But tears of joy, such as still may

Be true of good women this day.

Of such the old proverb doth treat:

‘Eyes that weep have a mouth that’s sweet’.

This I’ll add: true affection’s so

Marked, forever, by joy and woe.

If one sought to set Love’s nature

On the scales and then did measure

Its weight, it would always show

A weight of joy, a weight of woe.

They took joy in their reunion

Most royally; twas thus begun:

First to their bath each one went;

Twelve lovely maids did present

Themselves, and these had cared

For her, since so ill she had fared

Due to her husband’s displeasure,

Yet by no fault of hers however;

Despite her tattered shift by day,

These maids had made certain alway

That she was well-attired by night.

They bathed her now, with delight.

From his bath Duke Orilus came,

And Lady Jeschute, in the same

Manner, came forth most readily.

That woman, sweet gentle, lovely,

Stepped from her bath to his bed,

And, there, joy of sorrow was bred;

Her limbs found better covering

Than that she had long been wearing.

In close embrace the love of these two,

The prince, now wiser, the lady too,

By all the means they did employ

Attained the very summit of joy.

Duke Orilus rides with Lady Jeschute to Arthur’s camp

NOW will you kindly lend an ear

To how Duke Orilus came to hear

Of the journey King Arthur was on.

‘That good king’s grand pavilion,

And then a thousand tents or more,’

Declared a knight, ‘all these I saw,

Pitched on a broad meadow there,

Then hastened to tell of the affair;

Noble Arthur, the Britons’ lord,

Lies encamped beside a ford,

With a great company of knights,

And lovely ladies; I saw these sights

Not a mile away, as the crow flies,

For beside the Plimizoel he lies,

And they are camped on both its banks.’

Duke Orilus expressed his thanks,

And swiftly had his armour brought,

While his wife her maidens sought

Who their mistress did soon attire,

In a fine gown all must admire.

Those two sat on their bed eating

Little birds caught while roosting,

Jeschute received many a kiss;

Orilus being the culprit in this.

They led forth a handsome palfrey

All equipped to suit the lady,

It was possessed of a fine bridle,

One as fine as was the saddle

Onto which they now lifted her,

For she was to ride forth with her

Valiant husband, whose charger

Was caparisoned with no other

Trappings than those of the fight.

The same sword too was there in sight,

Slung, in front, from his saddle-bow.

Orilus armed from head to toe,

Strode to his mount, leapt to the saddle,

As she watched, sat there astraddle,

Then, ere he and Jeschute rode out,

Ordered his people to turn about,

And make their way back to Lalant.

When they’d progressed, in elegant

Style, as far as this camping place,

A mile or so downstream, apace,

Orilus sent the knight away,

Who’d shown them the path that day.

Now the Duke had his lovely lady,

And no other, there, for company.

Arthur, the good and true, had gone

From supper, to a meadow whereon

He sat surrounded by many a knight,

And twas here Orilus did alight.

His helm and shield were badly scarred,

His coat of arms so greatly marred

It could not be discerned, such blows

Had Parzival dealt him, God knows.

He handed fair Jeschute the reins;

A crowd of pages were at pains

To hasten to them, and surround

Them both, for in a trice they found

Themselves amidst a little crowd.

‘We shall care for your mounts!’ The proud

And worthy Duke laid down his shield,

On the grass, all its scars revealed,

And then enquired for that lady

Whom he sought, as was his duty.

Duke Orilus offers his surrender to Cunneware, his sister

THEY showed him, on the instant,

To where Cunneware de Lalant,

Was seated, who was his sister!

He advanced now in full armour,

The King and Queen greeted him,

He thanked them equally, and then

Offered submission to the lady.

She would have known him readily

By the dragons on his surcoat (she

Knew thus twas her brother) yet she

Possessed the doubt as to whether,

(His face concealed by his vizor)

He was Lahelin or Orilus.

‘You are my brother, kin to us;

Whichever brother I now detect,

From neither one will I accept

Any such abject surrender.

Both of you would ever render

Any service I requested;

If I were to see you so bested,

I would betray my kith and kin,

And the affection here within.’

The Duke knelt before the lady.

‘Twas the Red Knight undid me;

Ordering me to submit to you,

And Orilus is here, so to do.

Come, accept my surrender now,

That I may then discharge my vow.’

Her white hands enfolding his,

She received his pledge in this,

And by doing so, graciously,

This Knight of the Dragon, set free.

Once this was done, he made complaint,

‘The bond that ties us, not constraint,

Demands that I should seek redress.

Who was the man who did address

Such blows to you? I feel the pain

Of each of them; it shall be plain

To any who shall witness it,

That, when the time and place are fit

For my revenge, I too was wronged.

Moreover, he, to whom belonged

My defeat, and the boldest man

A woman bore, in any land,

Who calls himself the Red Knight,

He shares my cause, as if of right.

My lord the King, my lady Queen,

He pledges loyalty, and doth mean

Through me, to do so to my sister,

(Knowing not that I’m her brother),

Especially, asking you to requite

His humble duty as your knight,

And make amends to this lady

For the blows. Indeed, more lightly

I had escaped had we both known,

That knight and I, that not alone

Was he in feeling this great ill;

Close kin to her, I share his will.’

The anger then of many another

Towards Sir Kay strength did gather,

There by the Plimizoel. As one,

Gawain and Jofreit, Idoel’s son,

And King Clamide, the prisoner,

Whose fall we witnessed earlier,

And many another known to fame,

Knights whom I could readily name

(If it were not my wish to be

One who e’er shuns prolixity)

Pushed forward with due urgency.

Their exertions met with courtesy.

Jeschute was now led in, still seated

On her palfrey, and thus was greeted

By Arthur and Queen Guinevere, who

Welcomed her, and there did ensue,

Among the ladies, much kissing then.

Arthur spoke: ‘From the instant when

I learnt of it, I deplored your plight.

I knew your sire, a worthy knight,

King Lac, the mainstay of Karnant,

A man of honour, and valiant.

And then, indeed, you are so fair,

Your husband his ire should spare.

Did not your beauty gain the prize

At Kanedic, before our eyes?

He won the sparrow hawk that day;

It sat your fist, as you rode away.

Howe’er Orilus did wrong me,

I’d not wish yourself unhappy,

Nor would I find, in any place

Marks of sorrow on your face.

Tis joy that you return to favour,

And after travail’s bitter savour,

Are dressed as a lady should be.’

‘May God reward you,’ the lady

Said, ‘such courteous words ever

Serve but to increase your honour.’

Cunneware de Lalant did then

Lead Lady Jeschute forth again,

With Duke Orilus by her side.

Cunneware’s tent sat there beside

The king’s abode, on level ground,

(Where a clear stream could be found

Rising there) and upon the crest

A dragon floated o’er the rest,

As if, by it, its crown was clawed;

There, tethered to four ropes, it soared

As if alive, and on the wing,

And carrying off some tented thing,

To the realms of the upper air.

Orilus knew his emblem there,

For his device was hers as well,

Beneath its guardianship he fell,

And there the Duke doffed his armour.

His sweet sister showed him honour,

And saw to his needs, for she knew

In her wisdom, all one should do.

King Arthur’s household said, as one,

That glory was now companion

To the Red Knight’s bravery;

Not in whispers, but full loudly.

Now Kay asked Kingrun to attend

On Orilus, and did there depend

On him to wait there in his stead;

Kingrun, as if to that role bred,

Had long done such at Clamide’s court

In Brandigan; for Kay now sought

To avoid that office, since ill-chance

Had led to that sad circumstance

Whereby he’d thrashed the sister hard,

With his staff, and her flesh had marred;

And thus, his sense of propriety

Made him forego this courtesy,

Since, indeed, the noble maiden

Scarcely deemed the man forgiven.

Nonetheless he made fair provision

Of food and drink; all this, Kingrun

Brought to Orilus, whose fair sister

Served it for him, her dear brother,

Being accomplished in everything

Commendable; hers the carving,

Effected by that soft white hand,

While Lady Jeschute of Karnant,

Ate delicately as women do.

Arthur chose to visit them too,

Where they sat, companionably,

At their meal. ‘If poor fare it be,

Then such is far from my intent,

For you ne’er saw a master bent

On hosting you with a better will,

Or such sincerity. Eat your fill,

And my lady Cunneware please see

Your brother treated well, for me.

And now God bless you, and goodnight.’

Arthur retired, till morning light,

While Orilus sought his bed too,

Such that his lady Jeschute knew

The kind care of her spouse till morn,

Whereon the bright sun rose at dawn.

End of Book V of Parzival