Wolfram von Eschenbach

Parzival

Book IX: Parzival and Trevrizent

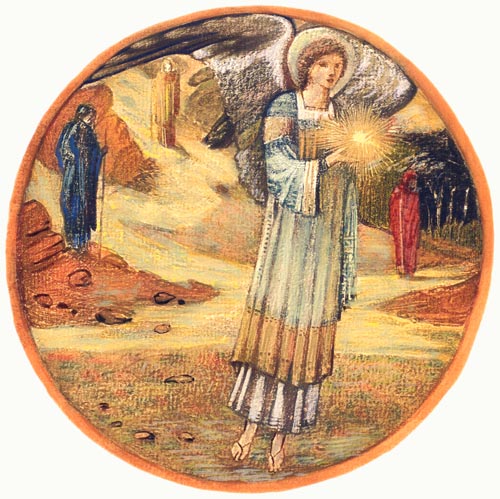

‘Star of Bethlehem’

From The Flower Book, Sir Edward Burne-Jones (English, 1833 – 1898)

Translated by A. S. Kline © Copyright 2020 All Rights Reserved

This work may be freely reproduced, stored and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non-commercial purpose. Conditions and Exceptions apply.

Contents

- Parzival encounters his cousin Sigune for a third time.

- He fights with a Knight Templar of Munsalvaesche.

- On Good Friday he meets with an aged knight coming from confession.

- Wolfram speaks about Kyot, his source, and Flegetanis.

- Parzival encounters Trevrizent the hermit, his uncle.

- Parzival tells Trevrizent of his past deeds and current state.

- Trevrizent preaches to Parzival concerning God.

- He speaks of the Grail and its keepers.

- He speaks of Anfortas, Lord of the Grail.

- Parzival declares his name and lineage.

- Trevrizent tells Parzival of their relationship to the Grail lineage.

- He tells the history of Anfortas’ affliction.

- Parzival dines with the hermit and confesses his error.

- Trevrizent speaks further concerning the Grail King, Anfortas.

- He speaks of his personal history.

Parzival encounters his cousin Sigune for a third time

‘OPEN!’ To whom? Who goes there?

‘To enter your heart thus, I would dare.’

‘Then you try too narrow a space.’

‘How so? Can I not seek a place?

I promise not to jostle and press,

I would tell you wonders, no less.’

‘Is’t you, Lady Adventure? Pray

How does he fare, your knight, this day?

Tis noble Parzival I mean,

Whom, with words harsh and lean,

Cundrie drove forth to seek the Grail,

A quest he sought, whate’er it entail,

Despite a wealth of ladies’ tears.

He left Arthur, and toiled for years,

So how then is he faring now?

Take up the tale, the when and how,

And say if sorrow is his story,

Or if he has achieved great glory,

Whether his fame spreads far and wide,

Or has shrivelled away and died.

Tell us his deeds with all their pain.

Has he seen Munsalvaesche again,

And gentle Anfortas whose sighs

A troubled heart did realise?

Speak, it would console us so.

Is he free of suffering or no?

Let us hear if Parzival was there,

Your lord and mine in this affair;

Reveal the life that he has led.

How has that child, of Herzeloyde bred,

Gahmuret’s son, fared all this while?

Tell us if, riding many a mile

To fight, he has won joy or woe.

The Grail does he still seek to know,

Or does he fester in idleness?

Tell us his life, no more nor less.’

The story tells us that Parzival

Had ranged widely, and twas all

On horseback, or o’er the sea.

None who fought him, certainly,

Kept his saddle, unless he were

Kith or kin, for in each affair,

He tipped the scales for his foe;

For his fame rose as theirs fell low.

He has defended himself full well

In many fierce wars, the tale doth tell,

Such that any who’d lease his fame

Must fear and tremble to gain that same.

The sword Anfortas had given him,

While with the Grail, failed on him,

Broke in a duel, and was re-made,

All with the well at Karnant’s aid;

Lac was the name of that spring.

The blade proved a powerful thing

In battle, and helped him win fame.

He sins who believes not that same.

Now, the tale says, it did befall

That to a forest did Parzival

Come riding, the hour I know not,

Where, in a most secluded spot,

By a fast-flowing stream, he saw

A new-built cell, one end more

Over the water than beside it.

Our brave young knight had lit

On a place where he might further

His endless search for adventure;

God was pleased to lead him so.

There he found an anchoress; know,

That she had dedicated her life

To God, of love, and was a wife

To woe, renouncing happiness.

Ever the seed of woman’s sorrow

Grew in her heart, every morrow

Saw it bloom and die, twas fed

By a love that was never dead,

For Schionatulander, twas he

Lay buried, while Sigune, she,

Above his tomb, led that life of woe.

She needed not the Mass to hear,

Her life was one long prayer here,

Her red lips all withered and dry,

Now that joy had passed her by.

No maid e’er endured such pain.

In solitude her sorrow did reign

In sorrow she had made her vow;

Sigune loved this dead prince now

For the sake of the love that died

With him, though ne’er his bride.

(Had she been his wife, e’en so

Lady Lunete had been full slow

To offer that counsel in distress,

She once gave to her own mistress:

To wed the man who slew her love,

And thus, his deed nigh-on approve.

Yet even today one can still find

A Lady Lunete of such a mind,

Who’ll give counsel out of season.)

If a woman, for whatever reason,

Shuns amorous ties, and doth strive

While her husband is yet alive,

To honour marriage and decency

He has been blessed, it seems to me,

With a rare treasure beyond price;

Her temperance needs no advice.

No restraint suits her so well,

As I, being witness, would tell.

Let her circumstances guide her

If he dies, yet if their honour

She doth maintain then no more fair

A garland could a woman wear

Were she her beauty to enhance,

To seek out pleasure at the dance.

Yet why do I speak of pleasure,

Seeing the woe, in full measure,

To which Sigune’s love brought her?

Better, then, if I drop the matter.

Parzival rode to the cell window,

Over fallen trees he must go,

Since no path at all lead there,

Though he merely sought to fare

Near enough to ask the way

Through the forest, I may say.

‘Does any person here reside?’

He asked, and, ‘Yes!’ a voice replied.

Since twas a woman’s voice he threw

His mount about, and then he drew

The steed onto the untouched grass.

Reproaching himself that, alas,

He’d not at once dismounted, he

Tethered the horse to a fallen tree,

And hung his worn shield there too.

Then, if bold, yet modest and true,

He ungirt his sword from his side,

And gently laid the weapon aside,

As courtesy bade, and then did go

To ask what he desired to know

Beside the window in the wall.

Empty of joy, and bare of all

Pleasure was that place of woe.

To the window he bade her go,

And, pale and worn, she courteously

Rose from her prayers. As yet he

Had no notion who she might be,

Little of her person could he see.

She wore a coarse hair-shirt within

Her grey cloak, next to her skin.

Her lover was Sorrow, and thereby

She must breathe many a sigh,

For he had laid all joy to rest.

The maiden now did meet her guest

At the window and greeted him

In gentle welcome; near to him,

She held a psalter, he could see,

And a ring on her finger, that she

Had kept there for her true love’s sake,

Despite this retreat that she did make.

Its gem was a garnet stone that shone

Forth fiery rays, with the light upon

Its facets from the window, where

A mourning head-dress hid her hair.

‘There is a bench by the wall outside,

She said, ‘be seated, you may bide

A while, if such be your pleasure,

And you own a moment’s leisure.

May God, who doth ever reward

Honest greetings, to you accord

Grace, for bestowing yours on me.’

The knight accepted, courteously,

Seating himself by the window

Requesting that she should also

Be seated there inside. ‘Never,’

She said, ‘have I sat here ever

In the presence of any man.’

Our knight, Parzival, then began

To question how she kept alive,

With no crops around to thrive:

‘I know not madam how you may

Lodge in this place day after day,

A wilderness far from any road,

Or feed yourself in this abode.’

‘Cundrie La Surziere doth bring

Me food, each Saturday evening,

From the Grail, so she provides,

For all this is as she decides.

Little my trouble on that score;

Would that were all, and no more!’

That twas untrue, he did conceive,

For she might yet seek to deceive.

‘For whose sake do you wear that ring?’

He asked, ‘for I know of a saying:

That the anchoress and the anchorite

Should refrain from love outright!’

‘If your words possessed such power,

They’d make me out a liar this hour;

Cry foul, if ever I learn to cheat;

Please God, I am free of all deceit.

It is not in me deny the truth.

I wear this fair token as proof

Of my true love for a dear man,

Of whose love you must understand

I ne’er took possession, indeed,

By any form of mortal deed;

Yet my maiden’s heart doth impel

Me to love him, and love him well.

Here, within, lies one whose ring

I have worn, since in the jousting

Orilus slew him; and thus, always,

I shall love him for all my days,

The joyless days that are left to me.

True love he doth deserve of me,

For he strove that love to advance,

Chivalrously, with shield and lance,

And in my service met his death.

I am a virgin, yet every breath,

Though I am unwed, cries that he

Is my spouse before God; for we

Should be wed if twas mere thought

Engendered deeds, for there is naught

In my mind gainst our marrying.

His death has wounded my being.

And so, this ring, that signifies

True wedlock, shall, in God’s eyes,

Assure my safe passage on high.

The torrent that doth feed my eye,

Welling from my heart, doth prove

A moated defence to my true love.

For there are two here,’ she did sigh,

‘Prince Schionatulander, and I.’

Parzival from her words did know,

That this was Sigune, and her woe

Deeply affected him; in haste,

He bared his head, ere she graced

Him with further speech, and she,

Glimpsing his face, at the sight,

Recognised the valiant knight.

‘You are Parzival! To what avail

Fare you now, as regards the Grail?

Have you learned its nature, at last?

If not, what places have you passed

On your quest, and where go you now?’

‘Much joy have I lost, I will avow,

In that endeavour,’ he told the maid.

‘The Grail has care upon me laid.

I left a land, where I wore the crown,

And a noble wife, of high renown,

No fairer born of human kind.

I long for her, and have often pined

For her modest and courteous ways,

For thus do I yearn for her always,

Knowing her tender love for me,

Yet even more for a chance to see

Munsalvaesche and the Grail. Alas,

The thing has not yet come to pass.

Cousin Sigune, twere wrong this day,

Knowing not all my pain and woe,

To treat me somewhat as your foe.’

‘Cousin, my censure, with its reason,

Your sad error, shall be forgotten,

Since, by not asking, as you ought,

The one question, that would have brought

Honour to you, while Anfortas

Was your host, it has come to pass

That you’ve foregone much happiness.

A single question, would have blessed

You with all that the heart desires.

But now your happiness retires,

And your spirit limps on behind.

Care dwells near your heart, I find,

Yet would have been a stranger still

Had you but questioned him, at will.’

‘I did as ill-fated men will do,

Yet, Cousin, counsel me anew.

Remember, we are kin, and say

How matters stand with me this day.

I would mourn for your sorrow,

Did not a greater weight of woe,

Burden me, a weight that’s more

Than any man has borne before,

For it seeks to crush me indeed.’

‘May He who views every deed,

To whom all suffering is known,

Grant you aid. What if some unknown

Path led you where you might see

Munsalvaesche now, fortuitously,

The very place which you confess

Is bound up with your happiness?

Cundrie La Surziere took her way

From here, not long ago I’d say,

Although I asked her not whether

She rode there, or someplace other,

I regret to say, for tis near at hand.

When she is here her mule doth stand

There where the clear spring doth flow

Out of the rock. I’d have you go

After her, since you may catch her

Full soon, as you ride the faster.’

He fights with a Knight Templar of Munsalvaesche

FORTHWITH, the warrior departed

And along the fresh track started;

That way Cundrie’s mule had gone,

Yet soon the undergrowth, upon

The path, so blocked it, to his cost,

That once again the Grail was lost.

All his hopes were swiftly dashed.

If to Munsalvaesche he’d passed,

Surely, he’d have asked the question

He’d failed to ask on the occasion

That you learned of earlier, reader,

And yet now must journey further.

So, let him ride; where’s he to go?

A mounted man came riding though

Towards him, one whose head was bare;

A splendid tabard he did wear,

Belted o’er his gleaming armour.

But for his lack of helm, this other

Was decked out as became a knight;

He advanced on Parzival outright.

‘Sir,’ said he, ‘it displeases me,

That you beat a track thus, wantonly,

Through forest owned by my good lord,

I shall you this warning afford,

Such a one as you will regret.

Munsalvaesche must never let

Any man close, nary a knight,

Without demanding that he fight

In fierce encounter, or doth proffer

Such amends as death doth offer.’

He bore a helm, in his left hand,

Twas silver-corded, his right hand,

Bore a fresh lance tipped with steel,

Armed he was from head to heel

But for that helm, which he placed

Now on his head, and once laced,

Showing anger, prepared to fight,

(Though his warlike threats alight

On one who will cost him dear,

As brave a warrior, without fear,

Who has shattered many a lance

As fine as this he doth advance).

‘Now were one riding o’er his field,

At harvest-time, then one might yield

A point,’ Parzival thought, ‘to anger,

But here is wilderness, naught other,

And, unless my right arm fails me,

He shall not for ransom bind me.’

They gave free rein on either side,

Then spurred on their mounts, to ride

Full tilt, and neither missed his aim.

Parzival oft had braved the same,

And, on his chest, he took the blow,

While, thrust with skill, his stroke so

Caught the other precisely where

His helmet-lace was knotted, there

Where a knight hangs his shield

At tourney, in the jousting field.

The outcome was that this Templar

Of Munsalvaesche, now flung afar

From his mount, into a gulley,

Rolled without rest, till finally

He reached a stop, while Parzival

Following through, escaped a fall,

For while his horse ran on and fell,

Breaking nigh every bone as well,

He himself grasped a cedar bough,

With both his hands (allow it now;

Twas no disgrace that he did suffer

Hanging, no executioner

Being present!) then his feet found

A purchase on the rocky ground.

His charger lay dead, but not his foe,

In the thick undergrowth below,

For the other knight, indeed,

Was climbing to safety, and at speed.

If he’d intended to share whatever

He won from Parzival, the matter

Now ended such that twould avail

Him better to seek it of the Grail.

Parzival now climbed back again,

And grasped the other horse’s rein,

Which was dangling down below,

And had trailed along the ground so,

That the horse had then stepped through,

And halted, as if told so to do.

Parzival thus renewed his stance,

Having lost naught but his lance,

And, having found a fine steed,

Was reconciled to that, indeed.

Not even mighty Lahelin,

I’d say, nor proud Kingrisin,

Nor Irot’s son, King Gramoflanz,

Nor Lascoyt, scion of Gurnemanz,

Had so splendid a joust e’er run,

As that in which this steed was won.

Now, Parzival rode on, not knowing,

In the slightest, where he was going,

But on that path, none did he see

Of Munsalvaesche’s company;

It grieved him that the Grail thus hid

Itself from him, as now it did.

On Good Friday he meets with an aged knight coming from confession

I’LL tell, if any doth care to hear,

How Parzival progressed from here;

Yet I’ll not count the weeks he saw

While seeking adventure, as before.

One morn, a light mantle of snow

Lay covering the ground, although

Twere deep enough to trouble us now;

Through a dense forest he did plough,

And there an aged knight appeared,

Naked beneath his grizzled beard;

His wife was as grey-haired as he.

O’er their bare flesh, draped loosely,

They both wore coarse cloaks of grey;

On pilgrimage, they made their way

To and from confession, nearby.

His daughters, pleasing to the eye,

Urged on by their chaste hearts, also

In similar cloaks of grey did go;

And all were barefoot, Parzival

Saluted the knight (it did befall

That his counsel would later bring,

Parzival good fortune) on seeing

That he’d the appearance of a lord.

The ladies’ lap-dogs ran at their sides,

And other knights and squires besides,

In seemly and humble attitude,

Made that pilgrimage, pride subdued.

Our noble warrior gave such care

To his clothes and armour that, there,

Being clad as befits a worthy knight,

They outshone the other’s grey outright.

With a tug at the reins, he turned aside,

Then questioned them, ere he did ride,

About their journey, and received

A mild reply, though the other grieved,

And reproached him, in that the day,

Of that holy season, brought no stay

To his journey nor gave him cause

To ride unarmed, or better to pause

And walk there barefoot, as did they.

‘My lord,’ said Parzival, ‘what day

Of the week it is, or when this year

Began, or the weeks gone by I fear

I know not; and then I used to serve

One called ‘God’, till He did reserve

Such shame for me, and yet I never

Failed Him in true devotion ever;

Still there is no help for me there.’

‘Unseemly the armour that you wear,’

Said the other, ‘if you should mean

Our Lord born of the Virgin Queen,

And, thus, believe in his Incarnation,

And the remembrance of the Passion

Which we are observing on this day!

For, know, Good Friday it is today,

Such that the world should rejoice

And at the same time, with one voice,

Cry woe. What greater loyalty

Could any on earth below e’er see,

Than that which God showed for our sake,

When to the Cross those men did take

Him, and hung him there on high?

If you are pledged to the faith, say I,

Let this knowledge bring you pain,

Recalling that great loss again:

He bartered his noble life, His death

Redeemed our debt, with His last breath,

For Mankind, damned, was destined for

Hell, through our sins, by God’s own law.

If you’re no heathen, remember

What day this is, ride on further,

Retrace our tracks, not far away,

Is a man so holy that he may

Counsel you, and grant, indeed,

A just penance for your misdeed.

If to a true confession you win,

Then he’ll absolve you of all sin.’

‘Why so unwelcoming, father,

In this weather? asked a daughter,

‘Why give him such chill counsel?

Lead him where, for a goodly spell,

He may warm himself. However

Fine he looks in his steel armour,

He must be cold, three times over.

You have tents and warm shelter,

If even King Arthur came here,

You could feed him, now appear

As a good host should, and take

This knight with you for pity’s sake.’

‘My daughter speaks true,’ the father

Said, ‘each year, despite the weather,

As the day nears of His passion,

He who rewards our devotion,

We come here, to a place nearby

In this wild forest; we shall share

With you the poor and humble fare

We brought with us to eat this day.’

The girls entreated him to stay,

And be their most honoured guest.

When Parzival their looks addressed

He saw their lips though frosted o’er

Were warm and not quite in accord

With the sorrows of that occasion,

And hesitated, with good reason.

(Had they some small debt to pay,

I’d have been loath to ride away

Rather than take a kiss in fee,

Should they wish to settle with me.

Women are women, a valiant man,

They’ll win over, they always can

And do, as they often have before!)

Parzival listened to all the four,

And thought: ‘The girls are so lovely

Twere ill to join their company,

Riding beside while they walk on,

When counsel tells me to be gone,

Twere more fitting that I go by,

Considering, as well, that I

Am now at odds with Him they love

With all their hearts, and approve

As their true help, yet Who bars me

From His aid, and exposes me

To sorrow.’ He offered his reply:

‘My lord and lady, let me go by.

May you prosper, in happiness!

And, young ladies, may your excess

Of courtesy be rewarded, truly,

And your thoughts of hospitality.

Now, though, allow me to depart.’

He bowed his head; on their part,

They inclined theirs with regret.

Herzeloyde’s child rides further yet.

His knightly order urged modesty

And compassion, and true mercy,

And, since Herzeloyde gave him

A loyal heart, remorse gripped him.

For only now did he dwell further

On the Creation, and his Creator,

And how powerful He must be.

‘What if God has such power, He

Can relieve all my misery?’

He thought:’ Oh, if ever a knight,

Who was remorseful, in His sight,

Earned His favour and His reward,

Or if wielding a shield and sword,

With knightly ardour, may obtain

His aid, and ease life’s cares again,

And if this be the day to aid a man,

Then let Him help, if help He can!’

He looked back, in the direction

From whence he had just ridden;

The good-hearted folk were standing

Where he’d left them, yet regretting

His departure, and with their gaze

The girls watched him on his way,

While he to his heart did confess

That they pleased his sight no less,

Their beauty full clear and bright.

‘If God’s power,’ thought the knight,

Is so great that it guides all things,

Creatures, people, and aid it brings,

Then I will praise it, and if He

In His wisdom guides us surely,

Then let Him lead me to success,

And this Castilian steed no less.

Let Him, of goodness, show His power!

Now, go where God chooses this hour!’

Loosening the reins, he spurred his horse,

Then let his mount decide their course.

For Fontane La Salvaesche it made,

Where to Duke Orilus he’d conveyed

The truth on oath. Twas the dwelling

Of Trevrizent the austere, who dining

Sparsely many a Monday, did seek

Naught finer any day of the week.

He had forsworn both bread and wine,

And, abstaining further, had no mind

For fish, or meat with blood within.

Such was the life, now free of sin,

That this man led. God had inspired

Him to prepare for his desired

Entry among the heavenly host.

He fasted, truly more than most,

Self-denial proving his weapon

Against the Devil’s intrusion.

Now, by Trevrizent, Parzival

Will be tutored and, amidst all,

Many a thing will be revealed

About the Grail, as yet concealed.

All those who have questioned me,

And criticised, you earn, you see,

Naught but shame. For Kyot asked

Me to hide them, thus I was tasked,

Because his source had forbidden

Kyot too, from making mention

Of them till the story attained

The point where they must be explained.

Wolfram speaks about Kyot, his source, and Flegetanis

KYOT, that well-known master, found

The source of this tale, sadly bound,

In some corner of Toledo, twas writ,

In a heathen script. He deciphered it,

After learning its ABC, without

Necromancy’s aid and, no doubt,

That he was a baptised Christian

Helped him, for otherwise no man

Had learned the tale; no magic art,

No hidden wisdom, on the part

Of the infidels. could e’er avail

In learning the nature of the Grail,

And how its secrets might be known.

A heathen, Flegetanis, well-known

For his skills, he and no other,

A natural philosopher,

Descended from King Solomon,

Of Israelite lineage a scion,

(His stock did many a sage yield,

Till baptism became our shield

Against hellfire) this man of note,

Of the true Grail’s wonders wrote.

Yet he worshipped a calf as though

The thing was his god, even so,

Being a heathen like his father.

How is it that the Devil’s laughter

Mocks people as wise as was he,

And puts them to scorn endlessly,

And that the Lord whose power

Is greatest, who at every hour,

Comprehends all wonders, wholly,

Fails to part them from their folly?

Flegetanis, this infidel,

The heavens understood full well,

The retreat and coming again

Of every heavenly body made plain,

And the time that doth appertain

Ere each doth reach its place again.

All humankind is affected by

Their rotation through the sky.

This Flegetanis thus did see,

And spoke of them reverentially,

The secrets that were concealed

In the constellations, as revealed.

He spoke of a thing called the Grail,

Whose name he read, without fail,

In the stars: ‘A heavenly band

Left it here, upon earth did stand

And then they rose above the sky,

If innocence drew them on high.

Then a pure Christian progeny,

Bred to a pure life, had the duty

Of its guard. Worthy, says the tale,

Are all those summoned to the Grail.’

So Flegetanis wrote of this matter.

The wise master Kyot did, later,

Search in Latin texts for the tale,

To find where keepers of the Grail

Might have dwelt, for such duty fit,

And, so disciplined in guarding it.

He read the chronicles of each land,

Of Britain, and France, and Ireland,

Yet in Anjou he found the tale,.

He read the truth about the Grail,

About Mazadan; the record there,

Of his scions, was laid out fair,

How, in the one line, Titurel,

And, in turn, his son Frimutel,

Bequeathed the Grail to Anfortas,

And then of how it came to pass

That Herzeloyde, his sister, bore

Gahmuret a son, as told before,

To whom this story doth belong,

And who is riding now, along

The fresh tracks the knight in grey,

And all his kin, had left that day.

Parzival encounters Trevrizent the hermit, his uncle

DESPITE the snow upon the ground

Parzival, gazing all around,

Recognised a field, where flowers

Had brightened it in other hours;

At the foot of a steep slope it lay

Where, with his right hand, on a day,

He had forced Orilus to relent

Towards Jeschute, all innocent,

And Orilus’ anger had died there.

Yet now the tracks continued where

A path still led, pace after pace;

Fontane La Salvaesche was the place

It ran towards. And there its lord

He found at home, who did afford

Parzival a courteous greeting.

‘Alas, sir! he cried, on meeting,

‘That you should be in such a state

On this holy day! Some desperate

Affair made you don your armour,

No doubt? If not, in some other

Garb perchance twere best to ride

If twas permitted by your pride?

Pray dismount, for to that action

I fancy you’ll make no objection;

Come, warm yourself by my fire.

If you ride forth from some desire

For adventure and Love’s reward,

And with true love you’re in accord

Love then, for love now you may,

Since Love indeed doth own this day!

And thereafter you may honour

Womankind, and seek her favour.

But come, dismount, as I suggest.’

Parzival did so, then, as his guest,

Stood before him, courteously.

He told him of those he did see,

Good people indeed he must own,

On the way, how the one had shown

Him the path to the hermit’s cave,

And praised too the advice he gave.

‘Sir, guide me now, I am a sinner.’

And the good man said, in answer,

‘I shall guide you, but tell me who

Spoke of myself, and directed you.’

‘Waking towards me in the wood,

A grey-haired man, his aspect good,

Saluted me kindly, as did his kin.

That honest man, absolved of sin,

Sent me here to meet with you,

And so, his tracks I kept in view.’

That was Gabenis,’ said his host,

‘And he is far nobler than most.

He is a prince of Punturteis,

And the mighty king of Kareis

Married his sister. No offspring

Of mortal line were in anything

Purer than his daughters you met

In the forest; far the purest yet.

And the Prince is born of royalty,

And every year he visits me.’

‘When you stood there, in full view,

Were you afraid as I rode nigh you?

Did I trouble you?’ asked Parzival.

‘Believe me, sir, no, not at all.

A bear or stag I would fear more

Than ever I’ll fear mankind, for

Tis but a man that here you see,

Possessed of human ability.

From the field I did ne’er remove

Myself, nor did a coward prove,

Nor of love was I innocent,

I was a knight, with your intent;

In bearing arms, I strove to win

The love of women, pairing sin

With chastity in thought, and I,

To win a lady’s favour thereby,

Lived in a fine and courtly way.

But all of that is forgot, I say.

Hand me the reins, your steed may rest;

Here by the cliff foot were best,

And then bracken we may gather

And fir-shoots for I lack fodder,

Yet he will have sufficient feed.’

Now, Parzival held back indeed,

But the good man said: ‘Trust me,

You are forbidden by courtesy

From contending with your host

Thereby shaming yourself almost.’

So Parzival yielded up the bridle

To his host, without a struggle,

And where a waterfall did flow

He led the knight’s mount below

The overhanging rock; that place

The sun’s rays did never grace,

It made a savage stable indeed.

A lesser man would have found

The cold bitter on its chill ground,

Freezing in steel armour there.

His host showing every care,

Led Parzival to his wide cavern

Sheltered from the wind, within

Which burned a bright charcoal fire,

Whose warmth the knight did much desire.

The master of this dwelling lit

A candle, while the knight did sit

On a bed of straw and ferns after

Removing his weight of armour,

And let the fire warm his limbs,

And add some colour to his skin.

It was no wonder he was weary,

Riding through rough forest many

A mile each day, and then at night

Sleeping unsheltered till first light,

And rising to find frosted ground.

Yet now a kind host he had found.

Parzival tells Trevrizent of his past deeds and current state

THERE was a warm coat lying there,

Which the hermit lent him to wear,

Then to the next cave he was shown;

Where were books, and an altar-stone

Bare of its cloth, as was but right,

In accord with the Good Friday rite;

On it there stood a reliquary,

Well-known to Parzival, for he

Had laid his hand on it to swear

His oath when Lady Jeschute there

Found her suffering turned to joy,

And new happiness without alloy.

Said Parzival: ‘I know this vial;

I swore an oath upon it a while

Ago, and found a painted lance,

Beside it. Sir, I took the lance,

And later, before I set it down,

I was told it brought me renown.

Two fine jousts with it I fought,

Yet I was so absorbed in thought

Of my wife that I knew it not,

Obliviousness was then my lot,

Though honour had not forsaken me.

Yet now more care comes to me

Than e’er was seen in any man.

How long is it since I laid a hand

Here on the lance that I did find?’

‘My friend Taurian left it behind,’

The hermit answered, ‘he told me

He’d missed it, and twas precisely

Four and a half years and three days

Since on that lance you first did gaze.

I’ll reckon it for you, if you care

To listen.’ From his psalter there,

A full and true account he cast

Of the years and weeks gone past.

‘It is only now,’ said Parzival,

That I’m aware how long in all

I have wandered directionless,

And absent from true happiness.

Such is no more than is a dream

To me, or at least so doth seem,

For I ever bear a weight of grief.

And I’ll say more: tis my belief

I’ve ne’er entered any place

Where God’s praise is sung; my face

Is turned towards battle ever.

God I resent, since as godfather

To all my troubles He doth stand;

He has raised them in His hand,

And buried deep my happiness.

If only God’s power would bless

And succour me, as an anchor

Joy would prove, that now doth rather

Drag through sorrow’s silt and mud.

If my heart is wounded (how could

It be whole when her thorny crown

Woe doth set upon true renown,

Won by brave deeds from mighty foes?)

Then all shame upon Him who shows,

Though aid lies within His power,

No mercy to me, and aids me not;

For if tis true that, whate’er our lot,

He is ever prompt to help mankind,

No help from Him do I e’er find,

For all the good they tell of Him.’

Trevrizent preaches to Parzival concerning God

HIS host sighed, and gazed at him,

‘Sir,’ he said, ‘if you would be wise,

And, thus, God’s mercy would realise,

Then in God you’ll place your trust.

He will help you, since help He must.

God aid us both! You must tell all;

Sit, though!’ said he, to Parzival,

‘Tell me how your anger arose

Such that hatred of God now grows

Within you; yet, as a man of sense,

Wait while I tell of His innocence,

Since you accuse Him to my face;

Ever present is His help and grace.

Though I was a layman I could read,

And copy, the sacred truth indeed:

That, as the Scriptures say, to gain

Help, His service we must maintain,

He who is never tired of granting

Aid to the soul at risk of plunging

Down to Hell. Be loyal to Him then,

Since God is forever loyal to men,

And steadfast in scorning falsity.

We should grant Him our loyalty,

For His sublime nature did take

Our form, for humanity’s sake.

God is Truth, and is e’er named so;

Of falseness, He was ever the foe;

You should think upon that deeply,

For in Him there’s no falsity,

So train your thoughts, to abjure

Falseness to Him, on any score.

You gain naught by your anger.

Any who heard you would rather

Think you of weak understanding,

For hating Him notwithstanding

What Lucifer and his company

Of angels reaped for their enmity.

As angels, lacking in bitterness,

Where did they find all that excess

Of malice that made them wage war

And earn the reward, furthermore

Of the fierce bitterness of Hell?

Astiroth and Belcimon fell,

Belet and Radamant, and more

That I could name, they all bore

The mark of their malice and envy,

A hellish hue that bright company

Of Heaven took on, when they fell.

When Lucifer descended to Hell

With his followers, Man came after.

For God made noble Adam later,

Out of earth, and from his body

God took that rib from which He

Formed the body of Eve, and so

We were consigned to grief and woe,

For she heeded not her Creator,

And so our bliss she did shatter.

By mortal birth then, these two

Had children, one son driven to

Take his grandmother’s virginity,

Out of discontent, and vainglory!

Now many will be pleased to ask,

Not understanding me at my task,

How is that possible? Nonetheless

It came to pass through sinfulness.’

‘I doubt that such a thing could be,’

Said Parzival, ‘who then was he

Descended from; that sinner who

Did the deed, according to you?

Such as this you should scorn to claim.’

‘Yet I will speak; let there remain,

No shadow of doubt; of deceit

Accuse me, if the truth complete,

I fail to tell; for Earth, she was

Adam’s mother, and because,

Though she nourished Adam, she

Was yet whole in her virginity,

Then it remains for me to tell

Who stole her maidenhead. Blood fell,

Upon the earth, and it was gone,

Taken from her by Adam’s son,

For Adam to that Cain was father,

Who for a trifle slew his brother,

Abel; thus, hatred among men

Began, and has endured since then.

Naught is pure as an honest maid.

Think of their purity; God made

Himself flesh, as the Virgin’s child.

Two men came thus of virgins mild,

For God a human face took on,

That of the first virgin’s son,

A condescension to mankind

From His sublimity. Now, we find

In Adam’s race both joy and woe

For he shares our blood, although

He sits above angels now, and in

His lineage lies the root of sin

Of which we all must bear our load.

Yet may the mercy that He showed

Through his power, be present here,

And keep our spirits free from fear!

Since He in human shape contended

Loyally with disloyalty, then ended

Must be your quarrel with Him now.

In hopes of heavenly bliss, thus vow

Penance here for your sins, then be

Of your words and deeds less free.

Let me tell you of the reward

For those who in loose speech afford

Relief to their anger. They are damned

By their own mouths, thus, out of hand.

If old sayings teach of loyalty too

Then let all such be spoken anew.

In ancient times prophetic Plato

And the Sibyl claimed twould be so,

Foretelling, beyond doubt, that we

Would have, of Heaven, a surety

For our great debt. Of divine love,

He, in the highest, did yet remove

True souls from Hell, and behind

He left those souls to evil blind.

These glad tidings speak forever

Of the true and constant Lover.

The unwavering light, He shines

Through all things and so defines

Himself; and all those to whom

He shows his love, they find room

In their hearts for true contentment.

Twin offerings to earth he sent,

Love and anger; which aids more?

While the impenitent flee before

God’s anger, and from his love,

Yet any that repentant prove,

Atoning for their sins, will ever

Serve him, to seek his favour.

To Man’s thought he brings grace;

If thought denies the sun a place,

All locked away, without a key,

Secure from all things that may be,

Darkness lit by nary a ray,

Yet of its nature the Godhead may

Pierce the wall of night, and ride

Unseen and noiseless, there inside,

Without a leap or thud or jingle.

And when, from the heart, a single

Thought arises, tis not so rapid

As to pass the body, and lie hid,

And only if the thought is pure

Does God accept it, for be sure

He sees our every thought so plain

That our frail deeds must cause Him pain.

When a man denies God’s name

And his benevolence, and in shame

God turns aside, what human aid

Can teach him not to be afraid?

What refuge has the wounded soul?

If you would wrong God, His whole

Being bent on Love, though anger

Is his sword, tis you who’ll suffer!

Now so direct your thoughts that He

Rewards your goodness equally.’

‘Sir, forever shall I feel gladness,

That you taught me, in your goodness,

Of Him who rewards all; indeed,

Requiting the good or evil deed.

I’ve spent my youth,’ said Parzival,

‘In care and trouble, in spite of all

I’ve learned, until this very day,

While woe my loyalty doth repay.’

‘Unless you do not wish to tell,

I should like to assay, as well,

Your sins and your sorrows, now’

His host replied, ‘if you’ll allow

Me to be the judge of them so,

I might well judge of your woe

And advise in ways that you

Might not yourself be able to.’

‘My deepest woe concerns the Grail,

Said Parzival, ‘next, I grow pale

For my wife than whom this earth

To none more fair has given birth.

I pine and languish for them both.’

‘And you are right sir,’ said his host,

‘In feeling such distress, the pain

You give yourself I too maintain

Derives from longing for your wife.

Howe’er you suffer in this life,

Or in Purgatory next are found,

If in true wedlock you are bound,

Your torments full soon shall end,

For on God’s aid you may depend;

Yet all your longing for the Grail,

You foolish man, shall not avail

You, for no man alive can gain

The true Grail, I do here maintain,

Except one whom Heaven doth say

Is destined for it; tis thus alway.

This much I know of the Grail,

For I have seen it; without fail,

I hold this to be true indeed.’

‘Were you there, or did so read?’

Asked Parzival.’ ‘Yes, I was there,’

His host his answer thus did share.

Parzival gave no sign that he

Too had been there, but eagerly

Asked to be told about the Grail.

He speaks of the Grail and its keepers

‘TIS known to me, and tis no tale,

That many bold warriors reside

At Munsalvaesche, and forth do ride,

In search of adventure, and whether

They reap glory, or something other,

For their sins, they must bear it well.

With the Grail that company doth dwell,

And I will tell you of the nurture

They receive, each brave warrior.

They are kept alive by a stone,

And the name by which tis known

If you have heard it not, is this,

It is named there “Lapsit exillis”.

It is by virtue of this stone

That the Phoenix dies, alone,

Burns to ashes, and is reborn –

Moults and rises with the dawn;

For then it shines as bright as ever,

Fair as before, in every feather.

Further, all mortals, however ill,

On seeing the stone, live on still

For a week, and from that day

Lose not their colour in any way;

If any, maid or man, could view

The Grail for a hundred years or two,

Then their colour you would confess

Was as it had been, and just as fresh

As in their prime, though it would grey.

Such power the stone confers, I say,

On mortals, that their flesh and bone

Renews, for young they have grown.

This stone they also call “The Grail”.

On this Good Friday, a dove doth sail

Downwards from heaven, and doth bear

That which governs the Grail there;

A small white wafer it doth bring,

And leaves it there, and then takes wing,

All dazzling bright, and doth return

To Heaven; of it the stone doth earn

Its highest virtue, for the dove I say

Brings a wafer each Good Friday,

And then, of that, the stone doth yield

All that is good from earthly field,

Though of paradisal excellence,

All food and drink; from its presence

Men take the flesh of all wild things,

That live upon the earth, with wings,

Or feet or fins, such the portion there

The Grail grants, of its power; a share,

To that brotherhood in chivalry.

Now those appointed; list to me,

Hear how it is that they are known:

Beneath the top edge of the stone

An inscription there makes plain

The lineage, and then the name,

Of one that’s summoned to the Grail;

And then the name itself doth pale,

Such that no need for erasure

Appertains to it for, whether

It told of man or maid, outright,

The writing vanishes from sight.

Those there who are full-grown came

As children, summoned by their name.

Happy the mother of any child

Destined to serve there; if their child

Is chosen, both rich and poor, of grace

Bidden to send them to that place,

Rejoice; from many a land they come,

From many a place in Christendom,

And then are free of shameful sin,

And they to Heaven will enter in,

For a rich reward they may expect;

Paradise is theirs, in the next

World, whenever they die in this,

And, in that realm, they find their bliss.

When Lucifer and the Trinity fought

With each other, those who sought

Not to battle, those angels, worthy

Noble, were made to fly, swiftly,

To earth, and to that self-same stone,

Ever-pure. If they did atone,

I know not, whether God forgave,

Damned them forever, or did save.

If twas His will, he took them back.

Since that day, it has seen no lack

Of guardians, for tis in the care

Of those God appointed to share

In that task, and to whom He sent

His angel; a sacred complement.

And this, sir, is what doth prevail

In matters concerning the Grail.’

He speaks of Anfortas, Lord of the Grail

‘IF knightly deeds with shield and lance

One’s earthly self can thus advance,

And win paradise for one’s soul,

Such chivalry has been my goal,’

Said Parzival, ‘I fought where’er

Men fought, and found glory there

Within my grasp. If God can judge

Of warriors, He will not grudge

A place to me in that company

Howe’er noble and fine they be,

That, thus, they may know a knight,

One who has never shunned a fight.’

‘There, of all places,’ said his host

You must guard yourself the most

Against such pride, and cultivate

Humility as man’s proper state.

Your youth may betray you yet,

Such that temperance you forget;

Pride ever reigns before a fall.’

His kindly host wept to recall

The tale he now began to tell;

For many a woeful tear did well.

‘Sir, there lives a king, his name

Is Anfortas, that very same,

Who was punished for his pride,

His agony such that you and I

Should be moved to endless pity.

He it was brought harm to many

Through his youth and his riches,

And then seeking love to excess,

Beyond the marriage bond, a tale

Unfit for those who guard the Grail.

In its service, knight and squire

Must set a curb on their desire;

Humility their pride must master,

And guide their actions thereafter,

Those of that noble brotherhood,

Who have sought to serve the good,

Warding off, by strength of hand

And arms, the men of every land

So that the Grail has been revealed

Only to those summoned to yield

Themselves to the Grail company

At Munsalvaesche. And one only,

Came there without such direction,

Lacking as yet in discretion,

Announced, it seems, but unassigned.

And since he, as if dumb and blind,

Uttered not one word to question

His host regarding the affliction

That tormented that noble man,

He departed from out that land

Saddled with sin; tis not for me

To speak of blame but, surely, he

Is bound to pay for that error,

Not asking why his host did suffer.

For Anfortas bore a weight of pain

The like of which none did sustain

Before. Now, twas ere this very same,

That Lahelin came there, to Brumbane,

Where Lybbeals of Prienlascors

Waited to joust with him; his horse

Lahelin took, after he had slain

Lybbeals, and tis more than plain

By doing so, despoiled the dead.

Sir, are you Lahelin?’ his host said,

‘For the horse you rode here, I see,

Like to those of the Grail company,

Is of Munsalvaesche, for there,

On the saddle, that mark they bear

Of the turtledove, as does your own,

And that mark to me is known

As the same device that Anfortas

Employs, though that emblem was

Ever depicted upon their shield.

The dove they bear upon the field,

It was bequeathed by Titurel

To his dear son, King Frimutel,

Which he displayed, that brave knight,

When he was slain in fair fight.

Frimutel loved his wife so dearly

No man ever loved more deeply

With such devotion. And you too

Should that manner of love renew,

And love your wife with all your heart.

Follow his path and, for your part,

You resemble Frimutel closely,

In form and manner equally.

He too was lord over the Grail.

Ah, sir, from whence do you hail?

Come, say who you are.’ In reply,

Parzival looked him in the eye.

Parzival declares his name and lineage

‘THE son of one who, seeking honour,

And urged on by knightly ardour,

Lost his life jousting,’ said Parzival,

‘And I would ask that you recall

Him in your prayers, sir, his name

Was Gahmuret, and, sir, he came

Of Angevin lineage. No, I

Am not King Lahelin, and, if I

Have e’er despoiled a mortal man,

Twas that I did not understand

What I did; yet I did the thing,

For I am guilty of slaying

That King Ither of Cumberland,

Who, with my own sinful hand,

I stretched dead upon the grass,

And then took what I would, alas.’

‘Ah, wicked world why do you so?

Cried his host. ‘You bring more woe

And bitter sorrow than you do joy!

Is this the means that you employ

To reward us? Thus, ends your song?

My nephew, you did great wrong;

What counsel can I give you now?

Your own flesh and blood, I avow,

You did slay. If you stand before

God, with the deed unatoned for,

And He judges, with justice true,

Why then so much the worse for you;

For you and King Ither were kin.

And God made manifest in him

Those virtues, born of nobility,

That grant life its true quality.

All misdeeds saddened him, for he

Was the very balm of constancy.

From all ill-thought he stood apart,

All that was noble filled his heart.

Worthy ladies should revile you,

For the loss of one, fine and true,

His service so entire, that knight,

On seeing him their eyes shone bright.

May God have mercy, in that you

Were the cause that they must rue

His passing. And, sadly, my sister,

Herzeloyde, who was your mother,

On your account, died of anguish!’

‘Ah no, cried Parzival, ‘what’s this?

For were this so, twould not avail,

If I myself were lord of the Grail,

Since naught could console me. Say,

Are these things so? And, I pray,

If I am your nephew, speak true

As good and honest people do.’

Trevrizent tells Parzival of their relationship to the Grail lineage

‘TIS not in me to deceive,’ he said,

‘Once you had left, she was dead

Of her love for you, all the reward

That her care for you did afford.

You were the creature that she bore,

The dragon that away did soar,

In a dream that came upon her,

Sweet lady, ere she did suffer

In bearing you! I have a brother,

Still living, and so too a sister.

Another sister, Schoysiane, died

Bearing a child (here he sighed).

Her husband was the Duke Kyot

Of Katelangen, who then forgot

All thought of future happiness,

Tormented so by grief’s excess;

The child, Sigune, his daughter,

Was thus entrusted to your mother.

Ah! Schoysiane’s death hurts me.

How could it not? Her heart, you see,

Full of woman’s virtue did float

Like an ark, like a sacred boat,

Above the tides of wantonness.

My living sister is no less

Virtuous and, as yet, unwed,

For, taking no man to her bed,

She still maintains her chastity.

Repanse de Schoye, that is she,

One who is charged with the Grail.

Its weight is such, all would fail

Who were sinful, and lacked grace,

To lift that wonder from its place.

My brother, and hers, is Anfortas,

Who Lord of the Grail is and was,

By hereditary right. Alas!

Happiness lies beyond his grasp,

He has but the hope that his task,

With its sufferings, will, after this,

Earn, for his soul, eternal bliss.

Things have reached this sad state

In a wondrous way, as I’ll relate,

And nephew, if your heart is true,

Pain, at his woe, must trouble you.

He tells the history of Anfortas’ affliction

ON the death of Frimutel, my father,

Then his eldest son, my brother,

Was summoned to the Grail as King

Lord and guardian of everything,

Both of the Grail, and its company,

And Anfortas indeed was worthy

Of the crown, and of the kingdom.

At that time, we were but children,

But when my brother reached the age

At which beards start, at that stage,

Love attacked him, as is her way

With young men, e’en to this day;

One might call it shameful of her,

The way she doth make them suffer.

But any Lord of the Grail bowed

By other love than that allowed

By the writing, is forced to pay

With pain and suffering alway.

My brother chose as his lady

One whom he considered wholly

Pure in her conduct; as to who

She was, let silence be her due.

He served her bravely, many a shield

He pierced, many he taught to yield.

As knight-errant, charming, comely,

In all the lands of chivalry

He won such fame no risk he ran

Of being surpassed by any man.

“Amor!” was ever his battle-cry,

Though it lacks humility, say I.

One day, when urged on by Love,

(Although his kin did not approve)

Enjoying Love’s encouragement,

To seek adventure this king went.

Jousting, amidst his swift advance

He was struck by a poisoned lance,

Through the thigh, and thereafter

He could not his health recover,

So serious was your uncle’s hurt.

His foe, small comfort I’d assert,

He’d slain, a heathen of Ethnise,

Born where, out of paradise,

The Tigris flows. This pagan thought

By valour to gain what he sought,

The Grail. His name was on the lance,

And he had sought, through circumstance,

An encounter in some far country,

Some distant land, beyond the sea,

To gain the Grail. Twas his prowess

That, thus, destroyed our happiness.

And yet your uncle did not yield,

He left him dead upon the field,

And brought the lance-tip away

Lodged in his body; yet that day

When he returned to his family

His sorry plight was clear to see.

When the king returned, at length,

So pale and so drained of strength,

A physician probed full deep,

And found the lance-head, complete

With a piece of the bamboo haft,

With was buried, and both the shaft

And the steel lance-tip he retrieved.

To the God, in whom I believed,

And do so now, I sought to pray,

And, on my knees I vowed, that day,

To renounce the path of chivalry,

In the hope that, to His glory,

He’d aid my brother in his need.

I forswore bread and wine, indeed

All the foods too, I used to relish,

Every kind of meat, every dish

Containing blood; yet, dear nephew,

That brought my people sorrow too,

That renunciation of the sword.

“Who now will be the Grail’s lord,

And, of its wonders, the guardian?”

They asked, as tears filled the land.

They sought God’s help by carrying

Him nigh the Grail, but when the king

Set eyes on it, came fresh affliction

He might not die such was its action,

Nor was it fitting that he should

Now that my own existence would

Embrace this life of wretchedness,

And our state was one of weakness.

The king’s wound festered, and none

Of the books of physic, no, not one,

Yielded a cure for his wound; all

Antidotes on which we might call,

Against the hot and vicious venom

Of snakes: the asp, the ecidemon,

The echontius, the licis,

The jecis, and the meatris,

And other poisonous serpents; all

The juice of herbs that withal

The learned doctors could extract

By the art of physics were, in fact,

(Let me be brief) of no use to him.

God thwarted us. We sought for him,

Some flower that might float upon

The waters of Gihon, or Pishon,

Tigris, Euphrates, where they rise,

All four, and flow from paradise,

Such that its fragrance is unspent

And their streams retain the scent,

Hoping, by this, to end our woe.

But all in vain, fresh sorrow also

Came there; yet we tried other means.

We obtained the twig that gleams,

From the golden bough the Sybil

Told Aeneas of, to dispel

The fumes of Phlegethon, and offer

Defence against all Hellish danger.

We sought to gain it lest the lance

Had been tempered in advance

In Hellfire, which had it cursed thus,

But with that lance, that tore from us

Our happiness, it was not so.

There is a bird of which we know,

Called the Pelican, that doth love

Its young to excess, and doth prove

Its innate fondness by piercing

Its own breast and then allowing

Blood into their mouths to flow,

And then it dies. To ease his woe,

We sought the blood of that bird,

To find if all that we had heard

Of its love might bring him aid,

And this upon his wound we laid,

As best we could; a hope forlorn.

There is a beast, the unicorn,

Monicirus, which so esteems

Virginal purity that, it seems,

In maidens’ laps it falls asleep.

This creature’s heart, to ease the deep

Pain the king felt, we obtained

And used, and from its brow retained

That red gemstone the unicorn

Doth grow at the base of its horn.

We stroked the wound with the stone,

And then went deeper, nigh the bone,

But still corruption it did show;

To him, and us, it brought but woe.

The herb they called trachonte, said

To grow, where some dragon has bled,

From that serpent, once tis slain,

We sought for, and did then obtain;

(It is said the herb doth partake

Of air’s nature) this we did take

To ascertain if it might prove

(That Serpent in the stars above)

To counteract the many changes

Of the moon there, as she ranges,

And certain planets, their return,

Those that greater pain did earn

For his wound, and yet the virtue

Of that rarest herb failed us too.

And now, before the Grail, we knelt,

Where, of a sudden, we saw spelt

Out, beneath its edge, the message

That a brave knight would make passage

To us, and were he heard to ask

A certain question (his sole task!)

Then our woe would pass away.

Yet if it chanced, before that day,

That some child, man, or maiden,

Did forewarn him of the question

Then it would fail of its effects,

And the wound, in all respects,

Would seem exactly as before,

Though deeper pain would lie in store.

Twas writ then: ‘Is it understood?

Forewarn the knight, and it would

Prove harmful. If he should omit

The question, that first eve, then it

Will cease to function, yet, should he

Be there in season and, correctly,

Ask the question, the man shall gain

The kingdom, and God will be fain

To end your woe; while, though healing,

Anfortas shall no more be king.’

On the Grail, and in this manner,

We read his anguish would be over

If the question were asked of him.

And so, we salved the wound for him,

With whate’er might grant him ease,

Nard that doth ever soothe and please,

Theriac, gainst venom proved good,

And the strong incense of aloeswood;

Yet the pain remained, nonetheless.

I chose this place; scant happiness

I’ve achieved with each passing day.

Since then a knight did ride that way,

Yet better were it if he had not,

That knight I told you of, whose lot

Was but to garner shame, for he

Saw signs of suffering, certainly,

Yet he failed to ask the question,

“Good sir, what is your affliction?”

Of his host, youthful ineptness

Saw that he thus failed to address

The question; and, in so doing, he

Lost that rare opportunity.’

Parzival dines with the hermit and confesses his error

THEY carried on their tales of woe,

Lamenting, till noontide or so.

‘Let me attend to dinner,’ said

The host, ‘and then your mount’s unfed;

Though I shall fail in this unless

God provides; no smoke doth bless

My kitchen; such your fate today,

And for as long as you shall stay.

If only this snow would allow

Of wild herbs I might teach you now.

God grant that the snow soon thaws.

Meanwhile for this horse of yours

We’ll gather bracken; though he ate

Better at Munsalvaesche, I’ll state

That neither he nor you e’er came

Where, more willingly, the same

Would not be had, if good fodder

Were at hand.’ They went together

To seek it, he for many a root;

Bracken was Parzival’s pursuit;

With such they must rest content.

The host flagged not in his intent,

His rule was, that of all he won

Ere three o’clock, he ate none,

But hung it on bushes, before

Going abroad to look for more.

(Many the day he ate them not,

And fasted to the glory of God.)

The two companions did not fail

To go to the stream and, there, avail

Themselves of its pure flow to lave

The roots and herbs; both were grave,

From their lips there came no laughter.

Both men washed their hands, and after

Parzival set some bracken before

His horse though the feed was poor,

And then they returned to their fire,

And reclined to eat; they did aspire

To no other course; the kitchen bare,

No stew, no roast was present there.

Yet stirred by affection for his host,

Parzival deemed that he’d almost

Eaten with more contentment here

Than with Gurnemanz in that year

When he’d taught him, or when many

A lovely, and a noble, lady

At Munsalvaesche had passed by,

Where the Grail had met his eye,

And had feasted him. ‘Dear nephew,’

Said his wise host, ‘scorn not to view

This poor repast, for you’ll not find

A host, so it seems to my mind,

Who wished you good appetite more

Than I do, whom you sit before.’

‘Sir,’ answered Parzival, ‘may the grace

Of God ne’er attend me, in any place,

If aught was better that I’ve received,

Or more fitly hunger relieved.’

Had they forgot to lave their hands

After meeting hunger’s demands,

It would not have harmed their eyes

As handling fish doth, some surmise.

For my part, were I a moulted hawk,

You could have taken me a walk,

And I’d have risen from the fist

With ravening eagerness, fed on this!

You’d have soon seen me in flight.

Yet why mock the hermit and knight?

Tis ill of me! For you have heard

What had made them, in a word,

Poor in happiness, rich no more,

Oft cold now, though warm before,

That word was ‘love’; deepest woe

They suffered now for loving so,

Pure love, naught else indeed, and yet

They had their reward, twas set

Upon the hand of God; His grace

The one had earned in that place,

And the other the Lord would take

Into that grace, for his love’s sake.

Parzival and the good man rose,

To see to the horse. ‘Heaven knows,

Viewing your meagre fare, I suffer,

Knowing you have so poor a manger,

(The hermit spoke sadly to the creature)

Given the badge that doth feature

On your saddle, that of Anfortas.’

As they tended to the steed, alas,

They found a further cause for woe.

‘Now if shame would allow me so

To do,’ said Parzival, ‘my dear lord,

And uncle, to you I would afford

The history of a sad mischance

That befell me, through circumstance,

Which I beg you, of courtesy,

To forgive, and to pardon, in me,

For my faithful heart has sought

Refuge here, and contrition brought.

So greatly I erred, without intent,

That, if you accord me punishment,

Then farewell to a fair tomorrow,

For I shall ne’er be free of sorrow.

Condemn my youthful foolishness,

But grant me your aid, nonetheless.

That man who viewed the suffering

At Munsalvaesche, never asking

The saving question, that was I;

Such the error that makes me sigh.’

‘What say you nephew?’ cried his host,

Since you have approached almost

To rare success, and scorned it yet,

Then happiness we’ll both forget,

And we’ll attach ourselves to grief.

God gave you senses, tis my belief,

Yet no help did they grant to you,

Your pity they did betray, tis true,

With Anfortas’ wound so presented;

Yet to my counsel you’ve consented,

You must not grieve then to excess,

Grieve now, but then seek happiness.

Human nature may prove perverse,

For youth may be foolish or worse,

And age may prove less than wise,

Clouding a life once clear, likewise,

Such that whiteness has been marred,

And the young fresh shoots barred

From bearing sound and noble fruit.

Could I see them green, in pursuit

Of restoring your heart and vigour,

That you might yet win high honour,

And not despair of God; why, then,

You might seek glory once again,

Having achieved new life, and lo,

Make full amends by doing so.

For God will ne’er abandon you;

So I do counsel, in His name too.

Trevrizent speaks further concerning the Grail King, Anfortas

AT Munsalvaesche, now, did you see

The lance? We knew, of a certainty,

By the wound, and the summer snow,

Of Saturn’s return; here, below,

The frost caused your dear uncle more

Anguish, then, than ever before.

To the wound they must set the lance,

One pain quelled the other’s advance,

And so the lance was red with blood.

Certain planets, tis understood,

That circle, near to us or farther,

Whose times of return thus differ,

Bring the people here much woe,

And then the moon’s changes also

Are bad for the wound. No ease,

Then, comforts the King, no peace,

The frost it doth torment him so,

His flesh is colder than the snow.

And since the venom burns so hot

That from the spear-head is got,

Upon the wound the spear they lay.

The lance doth draw the frost away,

From his body, like to icy glass,

Which none could remove, alas.

Wise Trebuchet, he wrought however,

Proving skilful in such a matter,

Two knives of silver that cut through;

A charm it was that taught him to

Work so; twas writ on the King’s sword,

And to him did its aid afford;

Many will tell you, and I in turn,

That asbestos fibres will not burn,

But when fragments of this glass

Touched them, such came to pass,

For they were lit by a fiery flame;

Wondrous the nature of that same

Poison that sets such things ablaze!

The king is confined all his days,

Unable to ride, walk, lie or stand,

Thus, he reclines you understand,

He cannot sit, for he suffers pain

That with the moon’s changes doth gain

Power over him. There is a lake

Called Brumbane, and they take

Him there, for the clear breeze

Quells his wound’s stench, and doth ease

His anguish; and he calls those days

His days for sport; for all his catch,

Racked by agony, he needs match

It, back at home, with plenty more.

Yet twas claimed, by any who saw,

The he was indeed a fisherman,

And so that most unhappy man

Has been forced to suffer the tale,

Though he ne’er had aught for sale;

Salmon or lamprey, he had neither.’

‘I came upon him, seated, at anchor,

On that lake,’ said Parzival, swiftly,

‘And thought him so. My journey

Was long and wearisome that day,

From Belrepeire I took my way

By mid-morn, and so by evening

Safe shelter I there came seeking.

My uncle granted it there and then.’

‘The path you rode was perilous when

You travelled so,’ cried Trevrizent,

‘Past many a sentinel you went;

They keep sharp watch, and they man

Their posts such that no mere plan

That serves you in warfare will do,

If they ride forth, and then pursue.

Till now any who sought to fight

In joust with them, that brave knight,

The path of mortal danger did take,

For the warriors their lives do stake

Against the foe’s; the braver wins;

Such is their penance for their sins.’

‘Yet I rode there, and sought the king,

Without such challenge; that evening,

I found his palace so full of woe,

How can they seek contentment so?

For from a doorway a squire ran in,

And the lamentation, there within

The palace, set all echoing there.

Towards all four walls he did bear

A lance, and its tip red with blood,

At the sight of which all that good

Company were suffused with woe.’

‘Nephew, his host said, ‘even so,

For the king had never before

Felt pain so great, as that he bore,

When Saturn announced its entry,

For its coming bodes ill, you see,

That planet brings the frost indeed.

Merely laying the lance, at need,

Upon his wound failed to aid us;

Deep our thrust, and injurious.

For Saturn rules with such power,

The wound sensed it, at an hour

Ere the chill frost itself arrived,

For the deep snow, that fell outside,

Came only on the second night,

Amid summer’s splendour bright.

While frost from him we cut away,

His people wept both night and day.

‘Such is the pay that grief demands,’

Said Trevrizent, ‘tears wet our hands.

The lance that cut them to the heart

Destroyed their joy, and on their part,

Their tears did thus perform anew

The rite of baptism rendered true.’

‘There five and twenty maids I saw,

Of noble bearing, who stood before

The King,’ said Parzival to his host.

‘God ordained the Grail should boast

A virgin band, to minister there,

And He entrusted it to their care.

The Grail chose noble servitors;

Thus the knights who guard the doors

Practice all the virtues that we

Associate with chastity.

God has overlong maintained

His wrath against them, for so pained

Are they, both young and old; ah! when,

Shall they find happiness again?

He speaks of his personal history

‘NEPHEW, I shall tell you a thing

You may believe, Fortune doth bring

To those of Munsalvaesche gain and loss.

They garner children, but at what cost?

Gain noble scions, and yet if any

Lord should die, in whatever country,

And the hand of God is credited,

If they seek to replace the dead,

And ask from the Grail company

A new lord, their prayer will be

Granted, yet then they must revere

Him, since God blesses his career.

God sends the men forth secretly,

But sends the maids out openly.

Know that King Castis made offer

For Herzeloyde, and your mother

Married him with due ceremony,

Yet it was not his destiny

To enjoy her, death laid him low,

(He had made over to her though

The lands of Wales and Norgals,

And Kanvoleis and Kingrivals,

Their cities) dying on the journey

While returning to his country.

She thus ruled as high queen over

Two lands when Gahmuret won her.

Thus, the maids are openly sent

From the Grail, while the noblemen

Go forth in secret, so they may

Breed children in a godly way,

In hopes those children will return

To serve the Grail, and thereby earn

Their place within its company,

And fill its ranks, in chastity;

For men who serve the Grail and prove

Faithful, forgo woman’s love.

Only the king may take a wife,

And those other lords whose life

God may assign to lord-less lands.

In serving a lady for her love

I a base recusant did prove.

That lady, of true nobility,

And my fair youth prompted me

To serve her in many a fight,

Since her love did my heart delight;

And for her sake, I took the field.

Fresh adventure, with sword and shield,

Was to my liking, not the tourney.

Inspired by passion, I did journey

To seek glory in every region.

I sought her love fighting Christian

And heathen both alike, I thought

Her reward needs be dearly bought.

Such was my life then in all three

Continents; lived, for that lady,

In Europe, and then in Asia,

And then the depths of Africa.

When fair jousting was my plan

I would ride beyond Gaurian,

And, at the foot of Famurgan,

Broke many a lance, and was in

Many a joust neath Agremontin;

Issue your challenge on one side

Of that mount, and forth do ride

Burning men to joust with you;

On the other, men just like you.

Beyond the Rohitscher Berg I rode,

Seeking adventure; on that road,

Noble Slovenes in company

Appeared, all set to challenge me;

Twas from Seville, I’d sailed forth

To reach their Celje, east and north,

From Aquileia, through Friuli.

In Seville, I had met your father,

He whom you spoke of earlier,

Fated thus, when I marched in,

To meet with that noble Angevin;

He’d found quarters ahead of me.

Alas, to Baghdad he must journey,

And so was slain, jousting there;

It troubles me always, that affair,

I shall lament his death forever.

And then, being rich, my brother

Would send me forth secretly,

Armed and clad magnificently.

Leaving Munsalvaesche I’d fare,

With his seal, to Carcobra, where

The lake is fed by the Plimizoel,

And so to the sea at Barbigoel,

Where on the strength of that seal

The Burgrave would let me steal

A band of squires and the trappings

Required for chivalry and jousting

In wild regions. Greeted there,

Unaccompanied, from each affair

I would return, while my retinue

I’d leave behind, and start anew

For Munsalvaesche, alone again.

‘Now, listen nephew, I’ll explain;

In Seville, your worthy father

At once claimed me as the brother

Of his wife Herzeloyde, though he

Had ne’er before clapped eyes on me!

Indeed, a beardless youth, I seemed

Fair as she, and none fairer deemed.

When Gahmuret claimed me, I swore

It was not true, he pressed me more

And forced me to confess, the knight,

That it was so, to his great delight.

He gifted me some treasures of his,

And I returned the gift, and this,

My reliquary, which you have seen,

I had cut, from a gem as green